Artemis program: Difference between revisions

→Missions: Paragraph is too large to be consolidated into one |

→Missions: Restored formatting, split proposed and planned missions to avoid misleading manifest and making proposed missions distinct |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

The first two components of the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, the Power and Propulsion Element and Utilization Module, along with three components of an expendable lunar lander,<ref name="a3-1">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Foust|2019|loc="And before NASA sends astronauts to the moon in 2024, the agency will first have to launch five aspects of the Lunar Gateway, all of which will be commercial vehicles that launch separately and join each other in lunar orbit. First, a power and propulsion element will launch in 2022. Then, the crew module will launch (without a crew) in 2023. In 2024, during the months leading up to the crewed landing, NASA will launch the last critical components: a transfer vehicle that will ferry landers from the Gateway to a lower lunar orbit, a descent module that will bring the astronauts to the lunar surface, and an ascent module that will bring them back up to the transfer vehicle, which will then return them to the Gateway."}}</ref> are planned to be delivered on multiple launches from commercial [[launch service provider]]s prior to the launch of [[Artemis 3]] in 2024.<ref name="a3-1"/><ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Bridenstine|Grush|2019|loc="Now, for Artemis 3 that carries our crew to the Gateway, we need to have the crew have access to a lander. So, that means that at Gateway we're going to have the Power and Propulsion Element, which will be launched commercially, the Utilization Module, which will be launched commercially, and then we'll have a lander there.}}</ref> The mission, planned for launch aboard a SLS Block 1B rocket, will use the primitive Gateway and the completed expendable lander to achieve the first crewed lunar landing of the program on the [[South Pole–Aitken basin]].<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Bridenstine|Grush|2019|loc="The direction that we have right now is that the next man and the first woman will be Americans, and that we will land on the south pole of the Moon in 2024."}}</ref><ref name="a3-2">{{Cite web|last=Chang|first=Kenneth|title=For Artemis Mission to Moon, NASA Seeks to Add Billions to Budget|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/science/trump-nasa-moon-mars.html|website=[[The New York Times]]|accessdate=25 May 2019|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20190525034839/https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/science/trump-nasa-moon-mars.html|archivedate=25 May 2019|date=25 May 2019|quote=Under the NASA plan, a mission to land on the moon would take place during the third launch of the Space Launch System. Astronauts, including the first woman to walk on the moon, Mr. Bridenstine said, would first stop at the orbiting lunar outpost. They would then take a lander to the surface near its south pole, where frozen water exists within the craters.a-moon-mars.html|deadurl=no|url-access=limited}}</ref> A proposal curated by [[William H. Gerstenmaier]] sees four more launches of SLS Block 1B launch vehicles with crewed ''Orion'' spacecraft and logistical modules of the Gateway between 2024 and 2028.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc="Developed by the agency's senior human spaceflight manager, Bill Gerstenmaier, this plan is everything Pence asked for—an urgent human return, a Moon base, a mix of existing and new contractors."}}</ref><ref name="spacecom-plans">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Foust|2019|loc="After Artemis 3, NASA would launch four additional crewed missions to the lunar surface between 2025 and 2028. Meanwhile, the agency would work to expand the Gateway by launching additional components and crew vehicles and laying the foundation for an eventual moon base."}}</ref> An additional SLS Block 1B Cargo launch would deliver a [[Colonization of the Moon|lunar outpost]] to the Moon's surface, as part of an uncrewed Artemis 7 mission in 2028 – it would be used for an extended crewed lunar surface mission, Artemis 8, later that year.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc="This decade-long plan, which entails 37 launches of private and NASA rockets, as well as a mix of robotic and human landers, culminates with a "Lunar Surface Asset Deployment" in 2028, likely the beginning of a surface outpost for long-duration crew stays."}}</ref><ref name="arstechnica-plans">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc=[Illustration] "NASA's "notional" plan for a human return to the Moon by 2024, and an outpost by 2028."}}</ref> Crewed Artemis 4–6 missions, launched yearly between 2025 and 2027, would test [[in situ resource utilization]] and [[Nuclear reactor|nuclear power]] on the lunar surface with a reusable lander, in preparation for Artemis 8. Prior to each crewed Artemis mission, various payloads to the Gateway, such as refueling depots and expendable elements of the lunar lander, would be delivered on commercial launch vehicles.<ref name="spacecom-plans"/><ref name="arstechnica-plans"/> |

The first two components of the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, the Power and Propulsion Element and Utilization Module, along with three components of an expendable lunar lander,<ref name="a3-1">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Foust|2019|loc="And before NASA sends astronauts to the moon in 2024, the agency will first have to launch five aspects of the Lunar Gateway, all of which will be commercial vehicles that launch separately and join each other in lunar orbit. First, a power and propulsion element will launch in 2022. Then, the crew module will launch (without a crew) in 2023. In 2024, during the months leading up to the crewed landing, NASA will launch the last critical components: a transfer vehicle that will ferry landers from the Gateway to a lower lunar orbit, a descent module that will bring the astronauts to the lunar surface, and an ascent module that will bring them back up to the transfer vehicle, which will then return them to the Gateway."}}</ref> are planned to be delivered on multiple launches from commercial [[launch service provider]]s prior to the launch of [[Artemis 3]] in 2024.<ref name="a3-1"/><ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Bridenstine|Grush|2019|loc="Now, for Artemis 3 that carries our crew to the Gateway, we need to have the crew have access to a lander. So, that means that at Gateway we're going to have the Power and Propulsion Element, which will be launched commercially, the Utilization Module, which will be launched commercially, and then we'll have a lander there.}}</ref> The mission, planned for launch aboard a SLS Block 1B rocket, will use the primitive Gateway and the completed expendable lander to achieve the first crewed lunar landing of the program on the [[South Pole–Aitken basin]].<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Bridenstine|Grush|2019|loc="The direction that we have right now is that the next man and the first woman will be Americans, and that we will land on the south pole of the Moon in 2024."}}</ref><ref name="a3-2">{{Cite web|last=Chang|first=Kenneth|title=For Artemis Mission to Moon, NASA Seeks to Add Billions to Budget|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/science/trump-nasa-moon-mars.html|website=[[The New York Times]]|accessdate=25 May 2019|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20190525034839/https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/13/science/trump-nasa-moon-mars.html|archivedate=25 May 2019|date=25 May 2019|quote=Under the NASA plan, a mission to land on the moon would take place during the third launch of the Space Launch System. Astronauts, including the first woman to walk on the moon, Mr. Bridenstine said, would first stop at the orbiting lunar outpost. They would then take a lander to the surface near its south pole, where frozen water exists within the craters.a-moon-mars.html|deadurl=no|url-access=limited}}</ref> A proposal curated by [[William H. Gerstenmaier]] sees four more launches of SLS Block 1B launch vehicles with crewed ''Orion'' spacecraft and logistical modules of the Gateway between 2024 and 2028.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc="Developed by the agency's senior human spaceflight manager, Bill Gerstenmaier, this plan is everything Pence asked for—an urgent human return, a Moon base, a mix of existing and new contractors."}}</ref><ref name="spacecom-plans">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Foust|2019|loc="After Artemis 3, NASA would launch four additional crewed missions to the lunar surface between 2025 and 2028. Meanwhile, the agency would work to expand the Gateway by launching additional components and crew vehicles and laying the foundation for an eventual moon base."}}</ref> An additional SLS Block 1B Cargo launch would deliver a [[Colonization of the Moon|lunar outpost]] to the Moon's surface, as part of an uncrewed Artemis 7 mission in 2028 – it would be used for an extended crewed lunar surface mission, Artemis 8, later that year.<ref>{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc="This decade-long plan, which entails 37 launches of private and NASA rockets, as well as a mix of robotic and human landers, culminates with a "Lunar Surface Asset Deployment" in 2028, likely the beginning of a surface outpost for long-duration crew stays."}}</ref><ref name="arstechnica-plans">{{Harvard citation no brackets|Berger|2019|loc=[Illustration] "NASA's "notional" plan for a human return to the Moon by 2024, and an outpost by 2028."}}</ref> Crewed Artemis 4–6 missions, launched yearly between 2025 and 2027, would test [[in situ resource utilization]] and [[Nuclear reactor|nuclear power]] on the lunar surface with a reusable lander, in preparation for Artemis 8. Prior to each crewed Artemis mission, various payloads to the Gateway, such as refueling depots and expendable elements of the lunar lander, would be delivered on commercial launch vehicles.<ref name="spacecom-plans"/><ref name="arstechnica-plans"/> |

||

{| class="wikitable sortable" |

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="font-size:90%;" |

||

|+ List of Artemis program missions |

|||

|+ |

|||

Missions |

|||

!Mission |

|||

!Patch |

|||

!Launch |

|||

!Crew |

|||

!Launch vehicle<sup>[a]</sup> |

|||

!Duration |

|||

!Description |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! scope="col" style="width:8em;" | Mission |

|||

![[Exploration Flight Test-1|EFT-1]] |

|||

! scope="col" class="unsortable" | Patch |

|||

|[[File:Exploration Flight Test-1 insignia.png|frameless|56x56px]] |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch date |

|||

| |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch pad |

|||

* 5 December 2014, 12:05 UTC |

|||

! scope="col" class="unsortable" style="width:12em;" | Crew |

|||

* [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 37|Cape Canaveral SLC-37]] |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch vehicle{{Efn|name=launch vehicle|Serial number displayed in parentheses.}} |

|||

|N/A |

|||

! scope="col" | Duration{{Efn|name=duration|Time displayed in days, hours, minutes, and seconds.}} |

|||

| |

|||

|- <!-- Please refrain from adding the Constellation program missions "Ares I-X" and "Pad Abort-1" --> |

|||

* [[Delta IV Heavy]] |

|||

! scope="row" | [[Exploration Flight Test-1|EFT-1]] |

|||

* (Delta 369) |

|||

| [[File:Exploration Flight Test-1 insignia.png|center|frameless|upright=0.2]] |

|||

|4h, 24m |

|||

| data-sort-value="20141205" | 5 December 2014, 12:05 UTC |

|||

|Uncrewed orbital test flight of the [[Orion (spacecraft)|''Orion'' MPCV]]<nowiki/>and its [[reaction control system]]; two orbits around Earth, reaching an apogee of 5,800 kilometres (3,600 mi) before making a high-energy reentry at 32,000 kilometres per hour (20,000 mph).<sup>[39][40]</sup> |

|||

| [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station|Cape Canaveral]] [[Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 37|SLC-37]] |

|||

| {{N/A}} |

|||

| [[Delta IV Heavy]] (Delta 369) |

|||

| data-sort-value="15886" | 4h, 24m, 46s |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Ascent Abort-2|AA-2]] |

! scope="row" | [[Ascent Abort-2|AA-2]] |

||

|[[File:Ascent Abort-2.png|frameless| |

| [[File:Ascent Abort-2.png|center|frameless|upright=0.2]] |

||

| data-sort-value="20190612" | 2 July 2019 |

|||

| |

|||

| Cape Canaveral |

|||

* 2 July 2019 |

|||

| {{N/A}} |

|||

* [[SLC-46|Cape Canaveral SLC-46]] |

|||

| [[Orion Abort Test Booster]] |

|||

|N/A |

|||

| data-sort-value="180" | ~3m |

|||

|[[Orion Abort Test Booster]] |

|||

|~3m |

|||

|Uncrewed test of the ''Orion'' [[Orion abort modes|Launch Abort System]], using a 10,000-kilogram (22,000 lb) test article at maximum aerodynamic load.<sup>[41][42]</sup> <sup>[43]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Artemis 1]] |

! scope="row" | [[Artemis 1]] |

||

|[[File:Exploration Mission-1 patch.png|frameless| |

| [[File:Exploration Mission-1 patch.png|alt=Exploration Mission-1 insignia|frameless|upright=0.2]] |

||

| data-sort-value="202006" | July 2020 |

|||

| |

|||

| [[Kennedy Space Center|Kennedy]] [[Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39|LC-39B]] |

|||

* July 2020 |

|||

| {{N/A}} |

|||

* [[Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39|Kennedy LC-39B]] |

|||

| [[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1]] |

|||

|N/A |

|||

| data-sort-value="2160000" | ~25d |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1]] |

|||

|~25d |

|||

|Uncrewed lunar orbital test flight of ''Orion''; 10 days in a distant retrograde orbit of 60,000 kilometres (37,000 mi) around the Moon before returning to Earth.<sup>[44]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Artemis 2]] |

! scope="row" | [[Artemis 2]] |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2022" | 2022 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2022 |

|||

| {{TBA}} |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| SLS Block 1 |

|||

|TBA |

|||

| data-sort-value="777600" | ~9d |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1]] |

|||

|~9d |

|||

|Crewed cislunar test flight of ''Orion'' with four astronauts; [[Free-return trajectory|free-return]] flyby of the Moon at a distance of 8,900 kilometres (5,500 mi).<sup>[45]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Artemis 3]] |

! scope="row" | [[Artemis 3]] |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2024" | 2024 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2024 |

|||

| {{TBA}} |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| SLS Block 1B |

|||

|TBA |

|||

| data-sort-value="2592000" | ~30d |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1]] |

|||

|} |

|||

|~30d |

|||

|Crewed flight to the [[Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway]] and landing at the [[South Pole–Aitken basin]] with four astronauts.<sup>[22]</sup> |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" style="font-size:90%;" |

|||

|+ List of proposed Artemis program missions |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! scope="col" style="width:8em;" | Mission |

|||

!Artemis 4 |

|||

! scope="col" class="unsortable" | Patch |

|||

| |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch date |

|||

| |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch pad |

|||

* 2025 |

|||

! scope="col" | Launch vehicle{{Efn|name=launch vehicle}} |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

! scope="col" | Duration{{Efn|name=duration}} |

|||

|TBA |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1B]] |

|||

|~30d |

|||

|Crewed flight to the Gateway to deliver the U.S. Habitation module; lunar landing to test [[In situ resource utilization|ISRU]]<nowiki/>and [[Nuclear reactor|Nuclear surface power]].<sup>[36]</sup> Also according to Bridenstine, by Artemis 4 the Orion pressure vessel will be reusable |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Artemis |

! Artemis 4 |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2025" | 2025 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2026 |

|||

| SLS Block 1B |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| data-sort-value="2592000" | ~30d |

|||

|TBA |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1B]] |

|||

|~30d |

|||

|Crewed flight to the Gateway to deliver a logistics module; first lunar landing with reusable ascent and transfer stages and further ISRU tsts.<sup>[36]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Artemis |

! Artemis 5 |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2026" | 2026 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2027 |

|||

| SLS Block 1B |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| data-sort-value="2592000" | ~30d |

|||

|TBA |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1B]] |

|||

|~30d |

|||

|Crewed flight to the Gateway to deliver a logistics module and [[Canadarm-2|Canadarm-3]]; second landing with reusable lander and deployment of Lunar Surface Assets.<sup>[36]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Artemis |

! Artemis 6 |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2027" | 2027 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2028 |

|||

| SLS Block 1B |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| data-sort-value="2592000" | ~30d |

|||

|N/A |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1B Cargo]] |

|||

|~9d |

|||

|Uncrewed lunar landing of the [[Colonization of the Moon|Lunar Surface Asset]].<sup>[36]</sup> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Artemis |

! Artemis 7 |

||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

| |

|||

| data-sort-value="2028" | 2028 |

|||

| |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

* 2028 |

|||

| SLS Block 1B Cargo |

|||

* Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| data-sort-value="777600" | ~30d |

|||

|TBA |

|||

|- |

|||

|[[Space Launch System|SLS Block 1B]] |

|||

! Artemis 8 |

|||

|>60d |

|||

| [[File:1x1.png|50x50px]] |

|||

|Crewed flight to the Gateway to deliver a logistics module; extended surface mission at the Lunar Surface Asset.<sup>[36]</sup> |

|||

| data-sort-value="2028" | 2028 |

|||

| Kennedy LC-39B |

|||

| SLS Block 1B |

|||

| data-sort-value="5184000" | >60d |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Revision as of 15:03, 25 May 2019

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by PhilipTerryGraham (talk | contribs) 5 years ago. (Update timer) |

| |

| Program overview | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Organization | NASA |

| Purpose | Crewed lunar exploration |

| Status | Ongoing |

| Program history | |

| Cost | $50 billion (2024; estimate) |

| Duration | 2011–2030s (planned)[1] |

| First flight | Exploration Flight Test 1 |

| Launch site(s) | Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 |

| Vehicle information | |

| Vehicle type | Capsule |

| Crewed vehicle(s) | Orion MPCV |

| Launch vehicle(s) | Space Launch System |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The Artemis program is an ongoing crewed spaceflight program carried out by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), American commercial spaceflight companies and international partners,[1] with the goal of landing the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface by 2024. Artemis would be the first step towards the long-term goal of establishing a "sustainable" American presence on the Moon, laying the foundation for private companies to build a lunar economy, and eventually sending humans to Mars.

Mandated by Space Policy Directive 1 in 2017, the lunar campaign was created and will utilize various spacecraft such as Orion, the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway space station, and commercially-developed lunar landers. The Space Launch System will serve as the primary launch vehicle for Orion, while commercial launch vehicles are planned for use to launch various other elements of the campaign.[2] The Trump administration proposed an extra $1.6 billion on top of the already proposed $21 billion for the 2020 fiscal year.[3] The funding is yet to be approved by Congress.[4]

History

The current version of the Artemis program incorporates several major components of other cancelled NASA projects such as the Constellation program and the Asteroid Redirect Mission. NASA originally conceived a return to the Moon by 2020 during the Constellation program which ran from 2006 through 2009. Originally proposed by President George W. Bush in the NASA Authorization Act of 2005. Constellation included the development of two heavy lift launch vehicles named Ares I and Ares V and the Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle.

Development of the project continued until in 2008 when president Barack Obama was elected. He established the Augustine Committee to determine how viable a Moon landing was by 2020 with the current budget. The committee discovered that the project was massively underfunded and that a 2020 Moon landing was impossible. The committee also outlined 3 outlines for future missions.

The project was put on hold in 2009 and the Obama administration cancelled funding for Constellation in the 2011 United States federal budget. On April 15, 2010, President Obama spoke at the Kennedy Space Center announcing the administration's plans for NASA. None of the 3 plans outlined in the Committee's final report[33] were completely selected.

President Obama cancelled the Constellation program and rejected immediate plans to return to the Moon on the premise that the current plan had become nonviable. He instead promised $6 billion in additional funding and called for development of a new heavy lift rocket program to be ready for construction by 2015 with crewed missions to Mars orbit by the mid-2030s.[34] The Obama administration released its new formal space policy on June 28, 2010, in which it also reversed the Bush policy's rejection of international agreements to curb the militarization of space, saying that it would "consider proposals and concepts for arms control measures if they are equitable, effectively verifiable and enhance the national security of the United States and its allies.

On June 30, 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to re-establish the National Space Council, chaired by Vice President Mike Pence. The Trump administration's first budget request keeps Obama-era human spaceflight programs in place: commercial spacecraft to ferry astronauts to and from the International Space Station, the government-owned Space Launch System, and the Orion crew capsule for deep space missions, while reducing Earth science research and calling for the elimination of NASA's education office.[5]

On December 11, 2017, President Trump signed Space Policy Directive 1, a change in national space policy that provides for a U.S.-led, integrated program with private sector partners for a human return to the Moon, followed by missions to Mars and beyond. The policy calls for the NASA administrator to "lead an innovative and sustainable program of exploration with commercial and international partners to enable human expansion across the solar system and to bring back to Earth new knowledge and opportunities." The effort will more effectively organize government, private industry, and international efforts toward returning humans on the Moon, and will lay the foundation that will eventually enable human exploration of Mars.

The President stated "The directive I am signing today will refocus America's space program on human exploration and discovery." "It marks a first step in returning American astronauts to the Moon for the first time since 1972, for long-term exploration and use. This time, we will not only plant our flag and leave our footprints -- we will establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars, and perhaps someday, to many worlds beyond."

On March 26, 2019, Vice President Mike Pence announced that NASA's Moon landing goal would be accelerated by 4 years with a planned landing in 2024.[5] On May 14, 2019, Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced the name of the new lunar program to be Artemis, named after the twin sister of Apollo in Greek mythology.

Development

With the aim of sending small lander missions to the lunar surface as a precursor to human exploration, NASA established the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program in March 2018.[6] The program was based on responses to a request for information issued by NASA in May 2017 into the capability of American commercial providers to launch payloads to the Moon.[7] Under the program, the agency will fund commercial providers capable of delivering lunar landers with scientific payloads through indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contracts.[8] It will qualify proposals capable of delivering at least 10 kilograms (22 pounds) of payload by the end of 2021.[8] Proposals for mid-sized landers capable of delivering between 500 kilograms (1,100 pounds) and 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of cargo for launch beyond 2021 will also be considered by NASA.[9]

This new focus on commercial landers led to the cancellation of the Resource Prospector rover mission,[10] which was also intended to be a precursor to human exploration, as well as the first polar lunar lander and the first robotic American lunar rover,[11][12] a few days before a draft request for proposals for the CLPS program was published by NASA on 27 April 2018.[8][12] By the time of its cancellation, US$100 million had been spent on its development,[13] and various technologies intended for the rover, such as scientific instruments, will be repurposed for missions selected for launch under the CLPS program.[8][13][14] The deadline for submissions for the first round of the program occurred on 9 October 2018.[15] The Artemis-7 lander by Draper, a not-for-profit engineering firm previously involved in the Apollo program, was one of the proposals submitted.[15]

While Lockheed Martin hired commercial space developer NanoRacks to study commercial opportunities for cargo delivery using the Orion spacecraft,[16] at the 69th International Astronautical Congress in October 2018, Lockheed Martin presented their concept (Lockheed Martin Lunar Lander) for a reusable lunar lander that would shuttle astronauts between the lunar surface and the Gateway, incorporating various technologies developed by Lockheed for the Orion spacecraft.[17][18] Lockheed Martin intends to submit its proposal when NASA starts to solicit proposals for larger crewed lunar landers to follow the CLPS program.[19]

Spacecraft

Orion

The Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (Orion MPCV) is an American-European interplanetary spacecraft intended to carry a crew of four astronauts to destinations at or beyond low Earth orbit (LEO) as part of the Artemis program. Currently under development by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) for launch on the Space Launch System, Orion is intended to facilitate human exploration of the Moon, asteroids and of Mars and to retrieve crew or supplies from the International Space Station if needed. [20][21]

Gateway

Originally, NASA had intended to build the Gateway as part of the now cancelled Asteroid Redirect Mission. But it has since been repurposed to support NASA's Artemis program. It will serve as a waypoint for the Orion MPCV and lunar lander as well as a secondary propulsion system to help change orbits and enable landings anywhere on the Moon. By 2024, the orbiting Gateway will be in its early assembly stage, and by then it will be made up of the 'Power and Propulsion Element' and a small habitat called Utilization Module.[2] The Gateway 'Power and Propulsion Element' is being made by Maxar Technologies (formerly SSL)[22] and the components and modules will be constructed by commercial companies and international partners. The Gateway commercial launches are separate from those for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services.[23]

Uncrewed landers

Draper's Artemis-7 lander, one of many proposed for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, would deliver scientific payloads to the lunar surface.[15] Named after Artemis of greek mythology and designated as Draper's seventh flight to the Moon,[15][24] the lander would be designed by Japanese developers ispace, and manufactured by American defense contractor General Atomics, while operations of the lander and its payload would be handled by Draper.[24][25]

Crewed landers

| External videos | |

|---|---|

A proposed crewed lunar lander by Lockheed Martin Space Systems is planned to be a reusable, single-stage system that would transport up to four astronauts and an additional 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of cargo between the Gateway and the lunar surface, where it could last up to two weeks before returning to the Gateway to refuel and service.[26][27] It would have a dry mass of 24 short tons (22,000 kilograms), comparatively heavier than the 4.7 short tons (4,300 kilograms) dry mass of the Apollo Lunar Module,[26] and would have an impulse (∆v) capacity of 5 kilometres per second (3.1 miles per second).[17] The lander's engines would use liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen as a propellant, and could be refueled on the lunar surface using lunar water.[18][28] Many technologies developed by Lockheed Martin for the Orion spacecraft are planned to be reused in the lander, such as instruments and module designs, helping to lower its development and manufacturing cost.[18][29] Space Systems' Vice President Lisa Callahan described the proposal as a "versatile, powerful lander that can be built quickly and affordably, and would be capable of establishing lunar colonies, delivering commercial and scientific payloads, and conducting "extraordinary exploration of the Moon".[30] Another proposal is a stretched tank version of Blue Origin's Blue Moon lander with an added ascent stage.

In May 2019 NASA announced 11 contracts worth $45.5 million in total for studies on transfer vehicles, descent elements, descent element prototypes, refueling element studies and prototypes to companies such as Lockheed Martin, Blue Origin, and SpaceX.[31] One of the requirements is that selected companies will have to contribute at least 20% of the total cost of the project "to reduce costs to taxpayers and encourage early private investments in the lunar economy."[32]

Launch vehicles

Space Launch System

The Space Launch System (SLS) is a Space Shuttle-derived super heavy-lift expendable launch vehicle. It is a primary part of NASA's deep space exploration plans,[8][9] including the Artemis crewed missions to the Moon, and could also serve as part of a future program to Mars.[10][11][12] SLS follows the cancellation of the Constellation program and is to replace the retired Space Shuttle. The SLS is to be the most powerful rocket in existence[13] with a total thrust greater than that of the Saturn V,[14] although Saturn V could carry a greater payload mass.

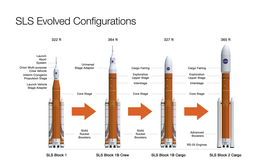

Three versions of the SLS launch vehicle are planned: Block 1, Block 1B, and Block 2. Each would use the same core stage with four main engines, but Block 1B would feature a more powerful second stage called the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS), and Block 2 would combine the EUS with upgraded boosters. Block 1 has a baseline LEO payload capacity of 95 metric tons (105 short tons) and Block 1B would have a baseline of 105 metric tons (116 short tons).[27] The proposed Block 2 would have had a lift capacity of 130 metric tons (140 short tons), which is similar to that of the Saturn V.[19][28] Some sources state this would make the SLS the most capable heavy lift vehicle built;[29][30] although the Saturn V lifted approximately 140 metric tons (150 short tons) to LEO in the Apollo 17 mission.[15][31]

On July 31, 2013, the SLS passed the Preliminary Design Review (PDR). The review encompassed all aspects of the SLS's design, not only the rocket and boosters but also ground support and logistical arrangements.[32] On August 7, 2014 the SLS Block 1 passed a milestone known as Key Decision Point C and entered full-scale development, with an estimated launch date of November 2018.[33][34] In April 2017, NASA announced that the schedule for the maiden flight would slip to 2019.[35] In November 2017, the Artemis 1 maiden flight slipped further to June 2020.[6]

In March, 2019, the Trump Administration released it's Fiscal Year 2020 Budget Request for NASA. This budget did not include any money for the Block 1B and Block 2 variants of SLS. It is uncertain whether these future variants of SLS will be developed.[33] Several launches previously planned for the SLS Block 1B are now expected to fly on commercial launcher vehicles such as Falcon Heavy, New Glenn, Omega, and Vulcan.[34] However, the recent budget increase of 1.6 billion dollars towards SLS, Orion, and crewed landers along with the launch manifest seem to indicate support of the development of Block 1B, debuting one year later than expected during Artemis 4. The Block 1B will be used mainly for co manifested crew transfers and logistic rather than constructing the Gateway. An uncrewed Block 1B is planned to launch the Lunar Surface Asset in 2028, the first lunar outpost of the Artemis program. Block 2 development will most likely start in the late 2020s, after NASA is regularly visiting the lunar surface and shifts focus towards Mars. [35]

Missions

Three tests of the Orion spacecraft will precede the launch of Artemis 1. Pad Abort-1, the second and final mission in the preceding Constellation program,[36][37] involved a successful test of Orion's launch escape system using a boilerplate capsule on 6 May 2010.[36][38] The second test of Orion, and the first mission in the Artemis program, was Exploration Flight Test-1 on 5 December 2014.[39][40] During the mission, an Orion boilerplate was launched atop a Delta IV Heavy rocket, and its reaction control system was tested in two orbits around Earth, reaching an apogee of 5,800 kilometres (3,600 mi) before making a high-energy reentry at 32,000 kilometres per hour (20,000 mph).[41][42] The third and final test of Orion prior to Artemis 1 will be Ascent Abort-2 on 2 July 2019, which will test an updated launch abort system at maximum aerodynamic load,[37][43][44] using a 10,000-kilogram (22,000 lb) Orion test article and a custom launch vehicle built by Orbital Sciences.[44][45] Artemis 1, planned to be the maiden flight of the SLS, will be launched in July 2020 as a test of the completed Orion and SLS system.[46] During the mission, an uncrewed Orion capsule will spend 10 days in a distant retrograde orbit of 60,000 kilometres (37,000 mi) around the Moon before returning to Earth.[47] Artemis 2, the first crewed mission of the program, will launch four astronauts in 2022 on a free-return flyby of the Moon at a distance of 8,900 kilometres (5,500 mi).[48][49]

The first two components of the Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, the Power and Propulsion Element and Utilization Module, along with three components of an expendable lunar lander,[50] are planned to be delivered on multiple launches from commercial launch service providers prior to the launch of Artemis 3 in 2024.[50][51] The mission, planned for launch aboard a SLS Block 1B rocket, will use the primitive Gateway and the completed expendable lander to achieve the first crewed lunar landing of the program on the South Pole–Aitken basin.[52][53] A proposal curated by William H. Gerstenmaier sees four more launches of SLS Block 1B launch vehicles with crewed Orion spacecraft and logistical modules of the Gateway between 2024 and 2028.[54][55] An additional SLS Block 1B Cargo launch would deliver a lunar outpost to the Moon's surface, as part of an uncrewed Artemis 7 mission in 2028 – it would be used for an extended crewed lunar surface mission, Artemis 8, later that year.[56][57] Crewed Artemis 4–6 missions, launched yearly between 2025 and 2027, would test in situ resource utilization and nuclear power on the lunar surface with a reusable lander, in preparation for Artemis 8. Prior to each crewed Artemis mission, various payloads to the Gateway, such as refueling depots and expendable elements of the lunar lander, would be delivered on commercial launch vehicles.[55][57]

| Mission | Patch | Launch date | Launch pad | Crew | Launch vehicle[a] | Duration[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFT-1 | 5 December 2014, 12:05 UTC | Cape Canaveral SLC-37 | — | Delta IV Heavy (Delta 369) | 4h, 24m, 46s | |

| AA-2 | 2 July 2019 | Cape Canaveral | — | Orion Abort Test Booster | ~3m | |

| Artemis 1 | July 2020 | Kennedy LC-39B | — | SLS Block 1 | ~25d | |

| Artemis 2 |

|

2022 | Kennedy LC-39B | TBA | SLS Block 1 | ~9d |

| Artemis 3 |

|

2024 | Kennedy LC-39B | TBA | SLS Block 1B | ~30d |

| Mission | Patch | Launch date | Launch pad | Launch vehicle[a] | Duration[b] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemis 4 |

|

2025 | Kennedy LC-39B | SLS Block 1B | ~30d |

| Artemis 5 |

|

2026 | Kennedy LC-39B | SLS Block 1B | ~30d |

| Artemis 6 |

|

2027 | Kennedy LC-39B | SLS Block 1B | ~30d |

| Artemis 7 |

|

2028 | Kennedy LC-39B | SLS Block 1B Cargo | ~30d |

| Artemis 8 |

|

2028 | Kennedy LC-39B | SLS Block 1B | >60d |

See also

References

Notes

Sources

- Bridenstine, Jim; Grush, Loren (2019). "NASA administrator on new Moon plan: 'We're doing this in a way that's never been done before'". The Verge. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Berger, Eric (20 May 2019). "NASA's full Artemis plan revealed: 37 launches and a lunar outpost". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Foust, Jeff (24 May 2019). "NASA Has a Full Plate of Lunar Missions Before Astronauts Can Return to Moon". Space.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Grush, Loren (3 October 2018). "This is Lockheed Martin's idea for a reusable lander that carries people and cargo to the Moon". The Verge. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Hill, Bill (27 August 2018). "Exploration Systems Development Update" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Retrieved 17 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Sloss, Philip (11 September 2018). "NASA updates Lunar Gateway plans". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Citations

- ^ a b [1]. NASA. Accessed on 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b NASA administrator on new Moon plan: 'We're doing this in a way that's never been done before'. Loren Grush, The Verge. 17 May 2019.

- ^ Fernholz, Tim; Fernholz, Tim. "Trump wants $1.6 billion for a moon mission and proposes to get it from college aid". Quartz. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Berger, Eric (14 May 2019). "NASA reveals funding needed for Moon program, says it will be named Artemis". Ars Technica. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert (14 May 2019). "NASA Names New Moon Landing Program Artemis After Apollo's Sister". Space.com. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (19 March 2018). "NASA courts commercial options for Lunar Landers". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

NASA's new Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) effort to award contracts to provide capabilities as soon as 2019.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Foust, Jeff (7 September 2017). "NASA preparing call for proposals for commercial lunar landers". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

That solicitation, he said, is being informed by responses the agency received from an RFI it issued in early May. That RFI sought details from companies about their ability to deliver "instruments, experiments, or other payloads" through the next decade to support NASA's science, exploration and technology development needs.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Foust, Jeff (28 April 2018). "NASA emphasizes commercial lunar lander plans with Resource Prospector cancellation". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

...selected but unspecified instruments from RP will instead be flown on future commercial lunar lander missions under a new Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. NASA released a draft request for proposals for that program April 27. [...] Under CLPS, NASA plans to issue multiple indefinite-delivery indefinite-quantity (IDIQ) contracts to companies capable of delivering payloads to the lunar surface. Companies would have to demonstrate their ability to land at least 10 kilograms of payload on the lunar surface by the end of 2021.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Werner, Debra (24 May 2018). "NASA to begin buying rides on commercial lunar landers by year's end". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

NASA also will look for payloads for the miniature landers in addition to landers capable of delivering 500 to 1,000 kilograms to the surface of the Moon.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Papenfuss, Mary (29 April 2018). "NASA Terminates Last Moon Rover After Trump Touts New Era Of Lunar Exploration". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

The rover, which was being designed for lunar missions in the early 2020s, was killed as NASA revealed plans to cultivate "commercial partners" for moon exploration.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Berger, Eric (27 April 2018). "New NASA leader faces an early test on his commitment to Moon landings". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

...the prospector has not been optimized for science—but rather as a precursor for human exploration.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sheridan, Kerry (28 April 2018). "Scientists shocked as NASA cuts only moon rover". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

We now understand RP was cancelled on 23 April 2018 [...] The robotic rover was being built as the world's only vehicle aimed at exploring the polar region of the Moon [...] and the first ever US robotic rover on the surface of the Moon.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Stuckey, Alex (5 June 2018). "NASA spent $100 million on much-anticipated lunar rover before scrapping it in April". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

NASA's overall Resource Prospector work toward risk reduction activities to advance instrument developments, component technologies including rover components, and innovation mission operations concepts will help inform future missions...

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Koren, Marina (27 September 2018). "The Moon Is Open for Business". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

...some of the instruments that were designed for the mission could be used in commercially funded efforts.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Foust, Jeff (10 October 2018). "Draper bids on NASA commercial lunar lander competition". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

Draper announced Oct. 10 that the not-for-profit research and development company has submitted a proposal to NASA's Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program for a small robotic lunar lander capable of carrying scientific payloads to the lunar surface. Proposals for the initial round of the CLPS program were due to NASA Oct. 9. [...] The organization noted that the "7" in Artemis-7 reflects that this will be Draper's seventh lunar landing mission, after the six Apollo lunar landings.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Berger, Eric (4 October 2018). "The Orion spacecraft may carry more than NASA missions to the Moon". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

Lockheed Martin, which is manufacturing the Orion spacecraft for NASA's deep space missions, plans to study whether some commercial payloads could fly along for the ride toward the Moon. [...] Lockheed has partnered with NanoRacks, a company that has helped to commercialize access to the International Space Station, to complete a privately funded study to determine the level of commercial interest in such an opportunity.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Williams, Matt (3 October 2018). "Lockheed Martin Unveils Their Proposal For a Lunar Lander". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

...Lockheed Martin's concept for a reusable lunar lander [...] was presented today at the 69th annual International Astronautical Congress [...] In its initial configuration, the lander would have an impulse (delta-v) capacity of 5 km/s...

- ^ a b c Wall, Mike (3 October 2018). "Lockheed Martin Unveils Plans for Huge Reusable Moon Lander for Astronauts". Space.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

The lander design leverages many technologies from the Orion capsule, which Lockheed is building for NASA. [...] The lander would be refueled between missions — eventually, perhaps, with propellant derived from water ice extracted from the Moon or asteroids.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Grush 2018, "In the meantime, NASA has mentioned that it will solicit proposals someday for larger landers that could potentially carry humans. Lockheed hopes to submit this design concept once the final solicitations are released." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrush2018 (help)

- ^ Spaceflight, Mike Wall 2011-05-24T17:48:39Z Human. "NASA Unveils New Spaceship for Deep Space Exploration". Space.com. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "EFT-1 Orion completes assembly and conducts FRR – NASASpaceFlight.com". Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ NASA Awards Artemis Contract for Lunar Gateway Power, Propulsion Nasa, 23 May 2019

- ^ More Details Emerge About Artemis. Marcia Smith, Space Policy Online. 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (10 October 2018). "Japanese startup ispace is tapping Apollo-era expertise to build lunar landers for NASA". The Verge. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

ispace will be in charge of the overall design of the vehicle, which the team has named Artemis-7 after the Greek goddess of the Moon. [...] Draper will also provide management and serve as the prime contractor of the entire four-company team. [...] In order to actually build these vehicles, the companies are turning to General Atomics, a defense contractor...

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nyirady, Annamarie (10 October 2018). "Draper Reveals NASA Lunar Payload Services Team". Via Satellite. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

Draper, as prime contractor, will lead a team that brings relevant experience in space, with partners that include General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems, ISpace and Spaceflight Industries.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Graham, Karen (4 October 2018). "Lockheed-Martin reveals plans for reusable lunar lander". Digital Journal. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

...the lunar lander would carry a crew of four astronauts and an additional 2,000 pounds of payload cargo to the surface of the Moon where it could stay for up to two weeks before returning to the Gateway [...] would weigh 24 tons empty [...] the expendable lunar lander that NASA used during the Apollo program carried two astronauts and weighed 4.7 tons without propellant.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Grush 2018, "Lockheed’s spacecraft is specifically designed to transport people to and from a space station — hailed as the Gateway — that NASA hopes to build in orbit around the Moon." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrush2018 (help)

- ^ Grush 2018, "...Lockheed says there is a possibility that the lander could run on fuel collected on the lunar surface one day. The lander’s engines are meant to run on liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen..." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrush2018 (help)

- ^ Grush 2018, "Lockheed also hopes to leverage what it has learned from building Orion to help build this vehicle as well and lower costs [...] the company plans to use some of the same instruments as Orion [...] some of the large curved pieces of Orion could also be used on the lander, and Lockheed’s suppliers already have existing machinery to make those pieces..." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGrush2018 (help)

- ^ Lockheed Martin (3 October 2018). "Lockheed Martin Reveals New Human Lunar Lander Concept". PRNewswire. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

This is a concept that takes full advantage of both the Gateway and existing technologies to create a versatile, powerful lander that can be built quickly and affordably. This lander could be used to establish a surface base, deliver scientific or commercial cargo, and conduct extraordinary exploration of the Moon.

- ^ Gina Anderson, Cheryl Warner. "NASA Taps 11 American Companies to Advance Human Lunar Landers". NASA. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ NASA awards $45.5M to 11 American companies to 'advance human lunar landers'. Benjamin Raven, M-Live. 21 May 2015.

- ^ Smith, Rich (26 March 2019). "Is NASA Preparing to Cancel Its Space Launch System? -". The Motley Fool. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "NASA FY 2019 Budget Overview" (PDF). Quote: "Supports launch of the Power and Propulsion Element on a commercial launch vehicle as the first component of the LOP - Gateway, (page 14)

- ^ "Space Launch Report". www.spacelaunchreport.com. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ a b Pearlman, Robert (6 May 2010). "NASA tests Pad Abort system, building on 50 years of astronaut escape system tests". collectSPACE. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

The Orion Pad Abort-1 team has successfully tested the first U.S. designed abort system since Apollo," said Doug Cooke, NASA's associate administrator for the exploration systems directorate, at a post-flight briefing [...] The PA1 test was conducted under NASA's Constellation program, which a former NASA administrator described as "Apollo on steroids.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Sloss, Philip (24 May 2019). "NASA Orion AA-2 vehicle at the launch pad for July test". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

This will be the second and final planned LAS test following the Pad Abort-1 (PA-1) development test conducted in 2010 as a part of the ccanceled [sic] Constellation Program and the abort system design changed from PA-1 to AA-2 both inside and outside [...] in preparation for a scheduled daybreak test on July 2.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ David, Leonard (25 May 2019). "NASA Test Launches Rocket Escape System for Astronauts". Space.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

Called Pad Abort-1, the $220 million Orion escape system test showcased the system that could be used to rescue a crew and its spacecraft in case of emergencies at the launch pad.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Davis, Jason (5 December 2014). "Orion Returns to Earth after Successful Test Flight". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

NASA's Orion spacecraft returned safely to Earth this morning following a picture-perfect test mission. [...] Orion itself was originally part of NASA's now-defunct Constellation program, and is now a key component of the space agency's Mars plans.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Clark, Stuart; Sample, Ian; Yuhas, Alan (5 December 2014). "Orion spacecraft's flawless test flight puts Mars exploration one step closer". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

The launch at 12.05pm GMT aboard a Delta IV heavy rocket from Cape Canaveral, Florida, was as free of problems as Thursday's aborted attempt was full of them. Immediately, Nasa tweeted "Liftoff! #Orion's flight test launches a critical step on our #JourneytoMars".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kramer, Miriam (5 December 2014). "Splashdown! NASA's Orion Spaceship Survives Epic Test Flight as New Era Begins". Space.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

Orion's key systems were put to the test during the flight, which launched atop a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 Heavy rocket [...] the craft hit Earth's atmosphere as the capsule was flying through space at about 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Spaceflight Now staff (4 December 2014). "Orion Exploration Flight Test No. 1 timeline". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

The first orbital test flight of NASA's Orion crew capsule will lift off on top of a United Launch Alliance Delta 4 rocket from Cape Canaveral]s Complex 37B launch pad. The rocket will send the unmanned crew module 3,600 miles above Earth...

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Phys.org staff (3 August 2018). "Image: The Orion test crew capsule". Phys.org. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

In the Ascent Abort-2 test, NASA will verify that the Orion spacecraft's launch abort system can steer the capsule and astronauts inside it to safety in the event of an issue with the Space Launch System rocket when the spacecraft is under the highest aerodynamic loads it will experience during ascent...

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Johnson Space Center (November 2017). "Ascent Abort Flight Test-2" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Retrieved 17 October 2018.

In April 2019, Orion is scheduled to undergo a full-stress test of the LAS, called Ascent Abort Test 2 (AA-2), where a booster provided by Orbital ATK will launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, carrying a fully functional LAS and a 22,000-pound Orion test vehicle...

- ^ Orbital Sciences Corporation (11 April 2007). "Orbital to Provide Abort Test Booster for NASA Testing". Northrop Grumman. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

Orbital Sciences Corporation (NYSE:ORB) today announced that it has been selected [...] to design and build the next-generation NASA Orion Abort Test Booster (ATB).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Foust 2019, "Artemis 1, or EM-1, will be an uncrewed test flight of Orion and SLS and is scheduled to launch in June of 2020."

- ^ Hill 2018, Page 2, "The first uncrewed, integrated flight test of NASA's Orion spacecraft [...] Enter Distant Retrograde Orbit for next 6–10 days [...] 37,000 miles from the surface of the Moon [...] Mission duration: 25.5 days"

- ^ Foust 2019, "Then, in 2022, Orion will carry astronauts to the moon for a flyby mission, but they won't attempt a lunar landing."

- ^ Hill 2018, Page 3, "Crewed Hybrid Free Return Trajectory, demonstrating crewed flight and spacecraft systems performance beyond Low Earth orbit (LEO) [...] lunar fly-by 4,800 nmi [...] 4 astronauts [...] Mission duration: 9 days"

- ^ a b Foust 2019, "And before NASA sends astronauts to the moon in 2024, the agency will first have to launch five aspects of the Lunar Gateway, all of which will be commercial vehicles that launch separately and join each other in lunar orbit. First, a power and propulsion element will launch in 2022. Then, the crew module will launch (without a crew) in 2023. In 2024, during the months leading up to the crewed landing, NASA will launch the last critical components: a transfer vehicle that will ferry landers from the Gateway to a lower lunar orbit, a descent module that will bring the astronauts to the lunar surface, and an ascent module that will bring them back up to the transfer vehicle, which will then return them to the Gateway."

- ^ Bridenstine & Grush 2019, "Now, for Artemis 3 that carries our crew to the Gateway, we need to have the crew have access to a lander. So, that means that at Gateway we're going to have the Power and Propulsion Element, which will be launched commercially, the Utilization Module, which will be launched commercially, and then we'll have a lander there.

- ^ Bridenstine & Grush 2019, "The direction that we have right now is that the next man and the first woman will be Americans, and that we will land on the south pole of the Moon in 2024."

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (25 May 2019). "For Artemis Mission to Moon, NASA Seeks to Add Billions to Budget". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

Under the NASA plan, a mission to land on the moon would take place during the third launch of the Space Launch System. Astronauts, including the first woman to walk on the moon, Mr. Bridenstine said, would first stop at the orbiting lunar outpost. They would then take a lander to the surface near its south pole, where frozen water exists within the craters.a-moon-mars.html

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Berger 2019, "Developed by the agency's senior human spaceflight manager, Bill Gerstenmaier, this plan is everything Pence asked for—an urgent human return, a Moon base, a mix of existing and new contractors." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBerger2019 (help)

- ^ a b Foust 2019, "After Artemis 3, NASA would launch four additional crewed missions to the lunar surface between 2025 and 2028. Meanwhile, the agency would work to expand the Gateway by launching additional components and crew vehicles and laying the foundation for an eventual moon base."

- ^ Berger 2019, "This decade-long plan, which entails 37 launches of private and NASA rockets, as well as a mix of robotic and human landers, culminates with a "Lunar Surface Asset Deployment" in 2028, likely the beginning of a surface outpost for long-duration crew stays." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBerger2019 (help)

- ^ a b Berger 2019, [Illustration] "NASA's "notional" plan for a human return to the Moon by 2024, and an outpost by 2028." harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFBerger2019 (help)

External links

- Moon to Mars portal at NASA

- Monthly report by the Exploration Systems Development (ESD)