Belt and Road Initiative: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Randy Kryn (talk | contribs) italics |

The Wikidata link is OK |

||

| Line 217: | Line 217: | ||

[[Category:Chinese economic policy]] |

[[Category:Chinese economic policy]] |

||

[[Category:One Belt, One Road| ]] |

[[Category:One Belt, One Road| ]] |

||

[[fr:Nouvelle route de la soie]] |

|||

Revision as of 02:42, 19 July 2018

| The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 丝绸之路经济带和21世纪海上丝绸之路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 絲綢之路經濟帶和21世紀海上絲綢之路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| One Belt, One Road | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 一带一路 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 一帶一路 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

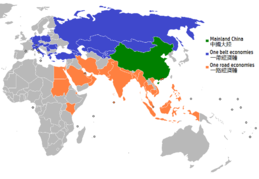

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road is a development strategy proposed by the Chinese government which focuses on connectivity and cooperation between Eurasian countries, primarily the People's Republic of China (PRC), the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the ocean-going Maritime Silk Road (MSR). Until 2016 the initiative was known in English as the One Belt and One Road Initiative (OBOR) but the Chinese came to consider the emphasis on the word "one" as misleading.[2]

The Chinese government calls the initiative "a bid to enhance regional connectivity and embrace a brighter future".[3] Others see it as a push by China to take a larger role in global affairs with a China-centered trading network.[4][5]

Vision and scope

The initiative was unveiled by Xi Jinping in late 2013, and was thereafter promoted by Premier Li Keqiang during state visits to Asia and Europe. The initiative quickly was covered by the official media intensively, and became the most frequently mentioned concept in the official newspaper People's Daily by 2016.[6] "Indeed, B&R is a connectivity of system and mechanism (Kuik 2016). To construct a unified large market and make full use of both international and domestic markets, through cultural exchange and integration, to enhance mutual understanding and trust of member nations, ending up in an innovative pattern with capital inflows, talent pool, and technology database."[attribution needed][7]

The initial focus has been infrastructure investment, education, construction materials, railway and highway, automobile, real estate, power grid, and iron and steel.[8] Already, some estimates list the Belt and Road Initiative as one of the largest infrastructure and investment projects in history, covering more than 68 countries, including 65% of the world's population and 40% of the global GDP as of 2017.[9][10]

The Belt and Road Initiative addresses an "infrastructure gap" and thus has potential to accelerate economic growth across the Asia Pacific area and Central and Eastern Europe: a report from the World Pensions Council (WPC) estimates that Asia, excluding China, requires up to US$900 billion of infrastructure investments per year over the next decade, mostly in debt instruments, 50% above current infrastructure spending rates.[11] The gaping need for long term capital explains why many Asian and Eastern European heads of state "gladly expressed their interest to join this new international financial institution focusing solely on 'real assets' and infrastructure-driven economic growth".[12]

Oversight

The Leading Group for Advancing the Development of One Belt One Road was formed sometime in late 2014, and its leadership line-up publicized on February 1, 2015. This steering committee reports directly into the State Council of the People's Republic of China and is composed of several political heavyweights, evidence of the importance of the program to the government. Vice-Premier Zhang Gaoli, who is also a member of the 7-man Politburo Standing Committee, was named leader of the group, with Wang Huning, Wang Yang, Yang Jing, and Yang Jiechi being named deputy leaders.[13]

In March 2014, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang called for accelerating the Belt and Road Initiative along with the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor[14] and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in his government work report presented to the annual meeting of the country's legislature.

Infrastructure networks

The Belt and Road Initiative is geographically structured along several land corridors, and the maritime silk road.[15] Infrastructure corridors encompassing around 60 countries, primarily in Asia and Europe but also including Oceania and East Africa, will cost an estimated US$4–8 trillion.[16][17] The initiative has been contrasted with the two US-centric trading arrangements, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.[17] These programmes aimed at encompassing countries, financially, receive the support of Silk Road Fund and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; technically, are guided by B&R Summit Forum.

Silk Road Economic Belt

It has been suggested that Silk Road Economic Belt be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since January 2017. |

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited Astana, Kazakhstan, and Southeast Asia in September and October 2013, he raised the initiative of jointly building the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.[19] Essentially, the "belt" includes countries situated on the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. The initiative calls for the integration of the region into a cohesive economic area through building infrastructure, increasing cultural exchanges, and broadening trade. Apart from this zone, which is largely analogous to the historical Silk Road, another area that is said to be included in the extension of this 'belt' is South Asia and Southeast Asia. Many of the countries that are part of this belt are also members of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). North, central and south belts are proposed. The North belt would go through Central Asia, Russia to Europe. The Central belt goes through Central Asia, West Asia to the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean. The South belt starts from China to Southeast Asia, South Asia, to the Indian Ocean through Pakistan. The Chinese One Belt strategy will integrate with Central Asia through Kazakhstan's Nurly Zhol infrastructure program.[20]

The land corridors include:[15]

- The New Eurasian Land Bridge runs from Western China to Western Russia through Kazakhstan, and includes the Silk Road Railway through China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region, Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland and Germany.

- The China–Mongolia–Russia Corridor will run from Northern China to Eastern Russia.

- The China–Central Asia–West Asia Corridor will run from Western China to Turkey.

- The China–Indochina Peninsula Corridor will run from Southern China to Singapore.

- The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar (BCIM) Economic Corridor, runs from southern China to Myanmar and is officially classified as "closely related to the Belt and Road Initiative".[21]

- The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (Chinese: 中国-巴基斯坦经济走廊; Urdu: پاكستان-چین اقتصادی راہداری; also known by the acronym CPEC), also classified as "closely related to the Belt and Road Initiative,"[21] which is a US$62 billion collection of infrastructure projects throughout Pakistan [22][23][24] that aims to rapidly modernize Pakistan's transportation networks, energy infrastructure, and economy.[25][26][23][24] On November 13, 2016, CPEC became partly operational when Chinese cargo was transported overland to Gwadar Port for onward maritime shipment to Africa and West Asia.[27]

Maritime Silk Road

It has been suggested that Maritime Silk Road be merged into this section. (Discuss) Proposed since January 2017. |

The Maritime Silk Road, also known as the "21st Century Maritime Silk Road" (21世纪海上丝绸之路) is a complementary initiative aimed at investing and fostering collaboration in Southeast Asia, Oceania, and North Africa, through several contiguous bodies of water: the South China Sea, the South Pacific Ocean, and the wider Indian Ocean area.[28][29][30]

The Maritime Silk Road initiative was first proposed by Xi Jinping during a speech to the Indonesian Parliament in October 2013.[31] Like its sister initiative the Silk Road Economic Belt, most countries in this area have joined the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Ice Silk Road

In addition to the Maritime Silk Road, Xi Jinping also urged the close cooperation between Russia and China to carry out the Northern Sea Route cooperation to realize an "Ice Silk Road" to foster the development in the Arctic region. China COSCO Shipping Corp. has completed several trial trips on Arctic shipping routes, the Transport departments from both countries are constantly improving policies and laws related to development in the Arctic, and Chinese and Russian companies are seeking cooperation on oil and gas exploration in the area and to advance comprehensive collaboration on infrastructure construction, tourism and scientific expeditions.

East Africa

In May 2014, Premier Li Keqiang visited Kenya to sign a cooperation agreement with the Kenyan government. Under this agreement, the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway was constructed connecting Mombasa to Nairobi. After completion, the railroad stretches approximately 300 miles (480 km) costing around $250 million USD.[32]

In September 2015, China's Sinomach signed a strategic, cooperative memorandum of understanding with General Electric. The memorandum of understanding set goals to build wind turbines, to promote clean energy programs and to increase the number of energy consumers in sub-Saharan Africa.[33]

Hong Kong

During his 2016 policy address, Hong Kong chief executive CY Leung's announced his intention of setting up a Maritime Authority aimed at strengthening Hong Kong’s maritime logistics in line with Beijing's economic policy.[34] Leung mentioned "One Belt, One Road" no fewer than 48 times during the policy address,[35] but details were scant.[36][37]

University Alliance of the Silk Road

A university alliance centered at Xi'an Jiaotong University aims to support the Belt and Road initiative with research and engineering, and to foster understanding and academic exchange.[38][39] The network extends beyond the economic zone, and includes a law school alliance to "serve the Belt and Road development with legal spirit and legal culture".[40]

Financial institutions

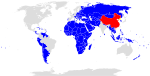

AIIB

| Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank | |

|---|---|

Prospective members (regional)

Members (regional)

Prospective members (non-regional)

Members (non-regional) |

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, first proposed by China in October 2013, is a development bank dedicated to lending for projects regarding infrastructure. As of 2015, China announced that over one trillion yuan ($160 billion US) of infrastructure projects were in planning or construction.[41]

The primary goals of AIIB are to address the expanding infrastructure needs across Asia, enhance regional integration, promote economic development and improve the public access to social services.[42] The Board of Governors is AIIB’s highest decision-making body under the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank Articles of Agreement.[43]

On June 29, 2015, the Articles of Agreement of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the legal framework was signed in Beijing. The proposed multilateral bank has an authorized capital of $100 billion, 75% of which will come from Asian and Oceania countries. China will be the single largest stakeholder, holding 26% of voting rights. The bank plans to start operation by year end.[44]

Silk Road Fund

In November 2014, Xi Jinping announced plans to create a $40 billion USD development fund, which will be distinguished from the banks created for the initiative. As a fund, its role will be to invest in businesses rather than lend money for projects. The Karot Hydropower Project in Pakistan is the first investment project of the Silk Road Fund, [45] and is not part of the much larger CPEC investment.

In January 2016, the Sanxia Construction Corporation began work on the Karot Hydropower Station 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Islamabad. This is the Silk Road Fund's first foreign investment project. The Chinese government has already promised to provide Pakistan with at least $350 million USD by 2030 to finance the hydropower station.[46]

Commentary and criticism

A new kind of multilateralism

In his March 29, 2015 speech at the Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) annual conference, President Xi Jinping said:

[T]he Chinese economy is deeply integrated with the global economy and forms an important driving force of the economy of Asia and even the world at large. ... China's investment opportunities are expanding. Investment opportunities in infrastructure connectivity as well as in new technologies, new products, new business patterns, and new business models are constantly springing up. ... China's foreign cooperation opportunities are expanding. We support the multilateral trading system, devote ourselves to the Doha Round negotiations, advocate the Asia-Pacific free trade zone, promote negotiations on regional comprehensive economic partnership, advocate the construction of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), boost economic and financial cooperation in an all-round manner, and work as an active promoter of economic globalization and regional integration[47]

Xi also insisted that, from a geoeconomic standpoint, the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank would foster "economic connectivity and a new-type of industrialization [in the Asia Pacific area], and [thus] promote the common development of all countries as well as the peoples' joint enjoyment of development fruits".[48]

Leveraging China’s infrastructure expertise

China is a world leader in infrastructure investment.[49] In contrast with the general underinvestment in transportation infrastructure in the industrialized world after 1980 and the pursuit of export-oriented development policies in most Asian and Eastern European countries,[50][51] China has pursued an infrastructure-based development strategy, which has resulted in engineering and construction expertise and a wide range of modern reference projects from which to draw, including roads, bridges, tunnels, and high speed rail projects.[52]

Members of the World Pensions Council (WPC), a non-profit policy research organization, have argued the Belt and Road initiative constitutes a natural extension of the infrastructure-driven economic development framework that has sustained the rapid economic growth of China since the adoption of the Chinese economic reform under chairman Deng Xiaoping,[47] which could eventually reshape the Eurasian economic continuum, and, more generally, the international economic order.[53][54]

Between 2014 and 2016, China’s total trade volume in the countries along Belt and Road exceeded $3 trillion, created $1.1 billion revenues and 180,000 jobs for the countries involved.[55] However, the worries in partnering countries are whether the large debt burden on China to promote the Initiative will make China’s pledges declaratory.[56]

Motivation

Practically, developing infrastructural ties with its neighboring countries will reduce physical and regulatory barriers to trade by aligning standards.[57] Additionally China is also using the Belt and Road Initiative to address excess capacity in its industrial sectors, in the hopes that whole production facilities may eventually be migrated out of China into BRI countries.[58]

A report from Fitch Ratings suggests that China's plan to build ports, roads, railways, and other forms of infrastructure in under-developed Eurasia and Africa is out of political motivation rather than real demand for infrastructure. The Fitch report also doubts Chinese banks' ability to control risks, as they do not have a good record of allocating resources efficiently at home, which may lead to new asset-quality problems for Chinese banks that most of funding is likely to come from.[59]

The Belt and Road Initiative is believed by some analysts to be a way to extend Chinese influence at the expense of the US, in order to fight for regional leadership in Asia.[60][61] China has already invested billions of dollars in several South Asian countries like Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan to improve their basic infrastructure, with implications for China's trade regime as well as its military influence. China has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sources of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into India – it was the 17th largest in 2016, up from the 28th rank in 2014 and 35th in 2011, according to India's official ranking of FDI inflows.

Analysis by the Jamestown Foundation suggests that the BRI also serves Xi Jinping's intention to bring about "top-level design" of economic development, whereby several infrastructure-focused state-controlled firms are provided with profitable business opportunities in order to maintain high GDP growth.[62] Through the requirement that provincial-level companies have to apply for loans provided by the Party-state to participate in regional BRI projects, Beijing has also been able to take more effective control over China's regions and reduce "centrifugal forces".[62]

Another aspect of Beijing's motivations for BRI is the initiative's internal state-building and stabilisation benefits for its vast inland western regions such as Xinjiang and Yunnan. Academic Hong Yu argues that Beijing's motivations also lie in developing these less developed regions, with increased flows of international trade facilitating closer economic integration with the China's inland core.[63] Beijing may also be motivated by BRI's potential benefits in pacifying China's restive Uighur population. Harry Roberts suggests that the Communist Party is effectively attempting to assimilate and pacify China's Uighur community by creating economic opportunities and so reduce separatism and ensure social harmony between Han settlers and the native population.[64][65]

Environmental concerns

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2018) |

The immense project will have environmental effects, generating a substantial carbon footprint, and construction will directly affect environmentally sensitive areas. The BRI will use more concrete [citation needed](a major source of greenhouse gas emissions ) than all pre-existing infrastructure projects on the planet.[66]

See also

Further reading

- Contessi, Nicola. "Central Asia in Asia: Charting Growing Transregional Linkages". Journal of Eurasian Studies 7, 1 (2016): 3–13.

- World Pensions Council (WPC) policy paper: Chinese Revolution Could Lure Overseas Investment, Dow Jones Financial News, October 12, 2015

- New York Times - Behind China's $1 Trillion Plan, May 13, 2017

References

- ^ China Britain Business Council: One Belt One Road

- ^ "BRI Instead of OBOR – China Edits the English Name of its Most Ambitious International Project". liia.lv. July 28, 2016. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ^ Xinhua News Agency (28 Mar 2015). "China unveils action plan on Belt and Road Initiative". The State Council of the People's Republic of China. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Compare: "Getting lost in 'One Belt, One Road'". Hong Kong Economic Journal. 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

Simply put, China is trying to buy friendship and political influence by investing massive amounts of money on infrastructure in countries along the 'One Belt, One Road'.

- ^

Compare:

"What Is One Belt One Road? A Surplus Recycling Mechanism Approach". 2017-07-07. SSRN 2997650.

It has been lauded as a visionary project among key participants such as China and Pakistan, but has received a critical reaction, arguably a poorly thought out one, in nonparticipant countries such as the United States and India (see various discussions in Ferdinand 2016, Kennedy and Parker 2015, Godement and Kratz, 2015, Li 2015, Rolland 2015, Swaine 2015).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ 钱钢: 钱钢语象报告:党媒关键词温度测试,2017-02-23,微信公众号“尽知天下事”

- ^ Jakobson, Linda. ""New Foreign Policy Actors in China."" (PDF). China Daily.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ General Office of Leading Group of Advancing the Building of the Belt and Road Initiative (2016). "Belt and Road in Big Data 2016". Beijing: the Commercial Press.

- ^ "What to Know About China's Belt and Road Initiative Summit". Time. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ CNN, James Griffiths,. "Just what is this One Belt, One Road thing anyway?". CNN. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Pensions Council (WPC) Firzli, Nicolas (February 2017). "World Pensions Council: Pension Investment in Infrastructure Debt: A New Source of Capital". World Bank blog. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ World Pensions Council (WPC) Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (October 2015). "China's Asian Infrastructure Bank and the 'New Great Game'". Analyse Financière. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "一带一路领导班子"一正四副"名单首曝光". Ifeng. April 5, 2015.

- ^ Joshi, Prateek (2016). "The Chinese Silk Road in South & Southeast Asia: Enter "Counter Geopolitics"". IndraStra Global (3): 4. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.3084253.

- ^ a b Ramasamy, Bala; Yeung, Matthew; Utoktham, Chorthip; Duval, Yann (November 2017). "Trade and trade facilitation along the Belt and Road Initiative corridors" (PDF). ARTNeT Working Paper Series, Bangkok, ESCAP (172). Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Getting lost in 'One Belt, One Road'". 12 April 2016.

- ^ a b Our bulldozers, our rules, The Economist, 2 July 2016

- ^ Based on <一帶一路規劃藍圖> in Nanfang Daily

- ^ "Xi Jinping Calls For Regional Cooperation Via New Silk Road". The Astana Times.

- ^ "Integrating #Kazakhstan Nurly Zhol, China's Silk Road economic belt will benefit all, officials say". EUReporter.

- ^ a b "Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Belt and Road". Xinhua. March 29, 2015.

- ^ "CPEC investment pushed from $55b to $62b - The Express Tribune". 12 April 2017.

- ^ a b Hussain, Tom (19 April 2015). "China's Xi in Pakistan to cement huge infrastructure projects, submarine sales". McClatchy News. Islamabad: mcclatchydc. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ^ a b Kiani, Khaleeq (30 September 2016). "With a new Chinese loan, CPEC is now worth $57bn". Dawn. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "CPEC: The devil is not in the details".

- ^ "Economic corridor: Chinese official sets record straight". The Express Tribune. 2 March 2015.

- ^ Ramachandran, Sudha (16 November 2016). "CPEC takes a step forward as violence surges in Balochistan". www.atimes.com. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ^ "Sri Lanka Supports China's Initiative of a 21st Century Maritime Silk Route". Archived from the original on 2015-05-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Shannon Tiezzi, The Diplomat. "China Pushes 'Maritime Silk Road' in South, Southeast Asia - The Diplomat". The Diplomat.

- ^ "Reflections on Maritime Partnership: Building the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road".

- ^ "Xi in call for building of new 'maritime silk road'[1]-chinadaily.com.cn".

- ^ Jeremy Page (8 November 2014). "China to Contribute $40 Billion to Silk Road Fund". WSJ.

- ^ "CMEC签署肯尼亚基佩托风电项目".

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Lawmakers should stop CY Leung from expanding govt power". EJ Insight.

- ^ "We get it, CY ... One Belt, One Road gets record-breaking 48 mentions in policy address". South China Morning Post. 13 January 2016.

- ^ "【政情】被「洗版」特首辦官員調職瑞士".

- ^ "2016 Policy Address: too macro while too micro". EJ Insight.

- ^ Ma, Lie (11 April 2016). "University alliance seeks enhanced education co-op along Silk Road". China Daily. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ Yojana, Sharma (12 June 2015). "University collaboration takes the Silk Road route". University World News. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ Ma, Lie (12 November 2015). "Chinese and foreign law schools launch New Silk Road alliance". China Daily. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- ^ Wan, Ming (2015-12-16). The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: The Construction of Power and the Struggle for the East Asian International Order. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 70. ISBN 9781137593887.

- ^ "About AIIB Overview - AIIB". www.aiib.org. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- ^ "Governance Overview – AIIB". www.aiib.org. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- ^ "One Belt and One Road". Xinhua Finance Agency. Retrieved 2016-04-13.

- ^ "Commentary: Silk Road Fund's 1st investment makes China's words into practice". english.gov.cn. Retrieved 2015-07-15.

- ^ "Baidu: One Belt One Road". baike.baidu.com. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- ^ a b Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (2015). "China's AIIB, America's Pivot to Asia & the Geopolitics of Infrastructure Investments". Revue Analyse Financière. Paris. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Wang Huning; et al. (29 April 2015). "Xi Jinping Holds Talks with Representatives of Chinese and Foreign Entrepreneurs Attending BFA Annual Conference". PRC Ministry of Foreign Affairs. . Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Chinese infrastructure: The big picture". McKinsey & Company. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ M. Nicolas J. Firzli World Pensions Council (WPC) Director of Research quoted by Andrew Mortimer (14 May 2012). "Country Risk: Asia Trading Places with the West". Euromoney Country Risk. . Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- ^ M. Nicolas J. Firzli (8 March 2011). "Forecasting the Future: The BRICs and the China Model". International Strategic Organization (USAK) Journal of Turkish Weekly. . Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ Firzli, M. Nicolas J. (2013). "Transportation Infrastructure and Country Attractiveness". Revue Analyse Financière. Paris. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ^ Grober, Daniel (February 2017). "New Kid On The Block: The Asian Infrastructure Bank". The Carter Center US-China Perception Monitor. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Xiao Yu, Pu (2015). "The Geo-economic effects of OBOR" (PDF). One Belt, One Road: Visions and Challenges of China's Geoeconomic Strategy.

- ^ "China Voice: The "Belt and Road" initiative brings new opportunities - Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- ^ "Opinion: China to Confront Financial, Engineering Challenges in 'Belt and Road' - Caixin Global". www.caixinglobal.com. Retrieved 2017-10-01.

- ^ CSIS China Power Project, How will the Belt and Road Initiative advance China’s interests?, 2017-06-27

- ^ Peter Cai, Understanding China's Belt and Road Initiative "Lowy Institute for International Policy" 2017-06-27

- ^ Peter Wells, Don Weinland, Fitch warns on expected returns from One Belt, One Road, Financial Times, 2017-01-26

- ^ CNN, James Griffiths. "Just what is this One Belt, One Road thing anyway?". CNN. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Jamie Smyth, Australia rejects China push on Silk Road strategy, Financial Times, 2017-03-22

- ^ a b "'One Belt, One Road' Enhances Xi Jinping's Control Over the Economy | Jamestown". jamestown.org. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ Yu, Hong (November 2016). "Motivation behind China's 'One Belt, One Road' Initiatives and Establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank". Journal of Contemporary China. 26 (105): 353–368. doi:10.1080/10670564.2016.1245894.

- ^ Lane, David; Zhu, Guichang (2017). Changing Regional Alliances for China and the West. London: Lexington Books. p. 94. ISBN 1498562345.

- ^ Xi, Jinping. "Working Together to Forge a New Partnership of Win-win Cooperation and Create a Community of Shared Future for Mankind". Statement at the General Debate of the 70th Session of the UN General Assembly.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ F. Laurance, William. "China's Global Infrastructure Initiative Could Bring Environmental Catastrophe". Nexus News. Retrieved 2 July 2018.