Ramana Maharshi

Baghavan Sri Ramana Maharishi | |

|---|---|

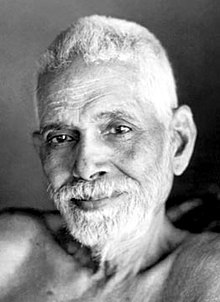

Ramana Maharshi when he was about 60 years old | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Venkataraman Iyer 30 December 1879 |

| Died | 14 April 1950 (aged 70) Sri Ramana Ashram in Arunachala |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Organization | |

| Philosophy | Advaita Vedanta |

| Part of a series on |

| Advaita |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950) is widely acknowledged as one of the outstanding Indian gurus of modern times.[1] He was born as Venkataraman Iyer, in Tiruchuli[note 1], Tamil Nadu (South India).[2]

At the age of sixteen, Venkataraman lost his sense of individual selfhood[3][note 2], an awakening[4] which he later recognised as enlightenment.[4][note 3] A few weeks thereafter he travelled to the holy mountain Arunachala, at Tiruvannamalai, where he remained for the rest of his life.[3]

His first years were spent in solitude, but his stillness and his appearance as a sanyassin soon attracted devotees.[5][6][7] In later years, he responded to questions, but always insisted that silence was the purest teaching.[6] His verbal teachings flowed "from his direct knowledge thatconsciousness was the only existing reality."[8] In later years, a community grew up around him, where he was available twenty-four hours a day to visitors.[8] Though worshipped by thousands, he never allowed anyone to treat him as special, or receive private gifts. He treated all with equal respect.[3] Since the 1930s, his teachings have also been popularised in the west.[9]

Venkataraman was renamed Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi by one of his earliest followers, Ganapati Muni.[note 4] This was the name he became known by to the world.[3]

In response to questions on self-liberation and the classic texts on Yoga and Vedanta, Ramana recommended self-enquiry as the principal way to awaken to the "I-I",[web 1] realising the Self[10][11] and attaining liberation.[12][note 5] He also recommended Bhakti, and gave his approval to a variety of paths and practices.[web 2]

Biography

Early years (1879–1896)

Family background

Ramana was born on 30 December 1879[note 6] in a village called Tiruchuli (Tiruchuzhi) near Aruppukkottai, Madurai in Tamil Nadu, South India on Arudra Darshanam day, the day of the `Sight of Siva'.[web 5]

He was born into an orthodox Hindu Brahmin (Iyer) family, the second of four children of Sundaram Iyer (1848–1890), from the lineage of Parashara, and Azhagammal (?-1922). Ramana was named Venkataraman Iyer at birth. His siblings were Nagaswamy (1877–1900), Nagasundaram (1886–1953) and sister Alamelu (1891/92-1953). Venkataraman's father was a respected man in town, and by profession a court pleader.[14]

Childhood (1879–1895)

Venkataraman was popular, good at sports, mischievous, and was very intelligent with an exceptional memory which enabled him to succeed in school without having to put in very much effort. He had a couple of unusual traits. When he slept, he went into such a deep state of unconsciousness that his friends could physically assault his body without waking him up. He also had an extraordinary amount of luck. In team games, whichever side he played for always won. This earned him the nickname 'Tanga-kai', which means 'golden hand'.[web 6]

When Venkataraman was about 11, his father sent him to live with his paternal uncle Subbaiyar in Dindigul because he wanted his sons to be educated in English so they would be eligible to enter government service, and only Tamil was taught at the village school in Tiruchuzhi. In 1891, when his uncle was transferred to Madurai, Venkataraman and his elder brother Nagaswami moved with him. In Dindigul, Venkataraman attended a British School.

In 1892, Venkataraman's father Sundaram Iyer suddenly fell seriously ill and unexpectedly died several days later at the age of 42.[15] For some hours after his father's death he contemplated the matter of death, and how his father's body was still there, but the 'I' was gone from it.

Awakening (1895–1896)

After leaving Scott's Middle School, Venkataraman went to the American Mission High School. One November morning in 1895, he was on his way to school when he saw an elderly relative and enquired where the relative had come from. The answer was "From Arunachala."[15] Krishna Bikshu describes Venkataraman's response:

The word 'Arunachala' was familiar to Venkataraman from his younger days, but he did not know where it was, what it looked like or what it meant. Yet that day that word meant to him something great, an inaccessible, authoritative, absolutely blissful entity. Could one visit such a place? His heart was full of joy. Arunachala meant some sacred land, every particle of which gave moksha. It was omnipotent and peaceful. Could one behold it? 'What? Arunachala? Where is it?' asked the lad. The relative was astonished, 'Don't you know even this?' and continued, 'Haven't you heard of Tiruvannamalai? That is Arunachala.' It was as if a balloon was pricked, the boy's heart sank.

A month later he came across a copy of Sekkizhar's Periyapuranam, a book that describes the lives of 63 Saivite saints, and was deeply moved and inspired by it.[16] During this period he began to visit, the nearby Meenakshi Temple in Madurai.[web 5]

Soon after, on 17 July 1896,[16] at age 16, Venkataraman had a life-changing experience. He spontaneously initiated a process of self-enquiry that culminated, within a few minutes, in his own permanent awakening. In one of his rare written comments on this process he wrote: 'Enquiring within Who is the seer? I saw the seer disappear leaving That alone which stands forever. No thought arose to say I saw. How then could the thought arise to say I did not see.[web 6]

In 1930, over a period of six weeks, Narasimha Swami had a series of conversations with Ramana on this experience. He summarised these conversations in his own words:[web 7][note 7]

"It was in 1896, about 6 weeks before I left Madurai for good (to go to Tiruvannamalai-Arunachala) that this great change in my life took place. I was sitting alone in a room on the first floor of my uncle's house. I seldom had any sickness and on that day there was nothing wrong with my health, but a sudden violent fear of death overtook me. There was nothing in my state of health to account for it nor was there any urge in me to find out whether there was any account for the fear. I just felt I was going to die and began thinking what to do about it. It did not occur to me to consult a doctor or any elders or friends. I felt I had to solve the problem myself then and there. The shock of the fear of death drove my mind inwards and I said to myself mentally, without actually framing the words: 'Now death has come; what does it mean? What is it that is dying? This body dies.' And at once I dramatised the occurrence of death. I lay with my limbs stretched out still as though rigor mortis has set in, and imitated a corpse so as to give greater reality to the enquiry. I held my breath and kept my lips tightly closed so that no sound could escape, and that neither the word 'I' nor any word could be uttered. 'Well then,' I said to myself, 'this body is dead. It will be carried stiff to the burning ground and there burnt and reduced to ashes. But with the death of the body, am I dead? Is the body I? It is silent and inert, but I feel the full force of my personality and even the voice of I within me, apart from it. So I am the Spirit transcending the body. The body dies but the spirit transcending it cannot be touched by death. That means I am the deathless Spirit.' All this was not dull thought; it flashed through me vividly as living truths which I perceived directly almost without thought process. I was something real, the only real thing about my present state, and all the conscious activity connected with the body was centered on that I. From that moment onwards, the "I" or Self focused attention on itself by a powerful fascination. Fear of death vanished once and for all. The ego was lost in the flood of Self-awareness. Absorption in the Self continued unbroken from that time. Other thought might come and go like the various notes of music, but the I continued like the fundamental sruti note ["that which is heard" i.e. the Vedas and Upanishads] a note which underlies and blends with all other notes."[web 9]

According to David Godman, a more accurate exposition of this event is given in the Sri Ramana Leela, the Telugu biography of Ramana that was written by Krishna Bhikshu, which "is surprisingly short, but it does have interesting additions and variations from the English version that was recorded by Narasimha Swami":[web 8][note 8] [note 9]

In 1896, Nagaswami [Bhagavan’s older brother] married Janaki Ammal. The in-laws' place was Madurai itself. At the post-wedding festivities, Venkataraman was the fellow-bridegroom to his brother. [It was his] seventeenth year. [He] was studying for the Matriculation examination. Though [he was] not that studious a person, there was no fear of failing in the examination. [He was] well-built, [having] good health; half of July had passed.

On the upper storey, Venkataraman was lying down. Nobody [else] was in there. Suddenly, it occurred to Venkataraman, 'I shall be dead'. There was no reason. 'Am dying!’

'There was no reason for feeling like that. It did not occur to me what that state was, and whether fear was proper or not. The thought of asking the elders or the doctors did not come. What is dying? How to escape it? This alone was the problem. There were no other thoughts. That very moment, [I] had to resolve it.'

'Dying means, the legs become stiff; lips become taut; eyes get closed. Breath stops. So it came into experience due to intensity of the strength of feeling. To me too, the legs became stiff, lips became taut, eyes got closed and breath stopped. But with consciousness not lost, everything was breaking forth clearly. (The activity of the outer sense-organs having gone, the in-turned perception became available.)’

'Even if this body dies, the I-consciousness will not go. The individuality- consciousness was clear. When the body is burnt and turned to ashes in the cremation ground, I will not become extinct. Because I am not the body.'

'Now the body is inert. Insentient; I, on the other hand, am sentient. Therefore, death is to the inert body, 'I' am [the] indestructible conscious entity.

'When the body gives up its activities, and the activities of the senses are not there, the knowledge that obtains is not senses-born. That 'flashing forth of I' is aparoksha. [It is] self-effulgent. Not a matter of imagination.

'The thing that is there after death is the eternal, real entity.' In this way, in one moment, new knowledge accrued to Venkataraman.

Although these ideas were expressed sequentially, this experience was obtained by Venkataraman spontaneously only.[web 8]

Ramana summarised his insight into "aham sphurana" (Self-awareness)[note 10] to a visitor in 1945:[web 8][note 11]

In the vision of death, though all the senses were benumbed, the aham sphurana (Self-awareness) was clearly evident, and so I realised that it was that awareness that we call "I", and not the body. This Self-awareness never decays. It is unrelated to anything. It is Self-luminous. Even if this body is burnt, it will not be affected. Hence, I realised on that very day so clearly that that was "I".[web 8]

At first, Ramana thought that he was possessed by a spirit, "which had taken up residence in his body".[web 7] This feeling remained for several weeks.[web 7]

Later in life, he called his death experience akrama mukti, "sudden liberation", as opposed to the krama mukti, "gradual liberation" as in the Vedanta path of jnana yoga:[web 8][note 12]

‘Some people,’ he said, 'start off by studying literature in their youth. Then they indulge in the pleasures of the world until they are fed up with them. Next, when they are at an advanced age, they turn to books on Vedanta. They go to a guru and get initiated by him and then start the process of sravana, manana and nididhyasana, which finally culminates in samadhi. This is the normal and standard way of approaching liberation. It is called krama mukti [gradual liberation]. But I was overtaken by akrama mukti [sudden liberation] before I passed through any of the above-mentioned stages.'[web 8]

After this event, he lost interest in school-studies, friends, and relations. Avoiding company, he preferred to sit alone, absorbed in concentration on the Self, and went daily to the Meenakshi Temple, ecstatically devoted to the images of the Gods, tears flowing profusely from his eyes.[14]

Venkataraman’s elder brother, Nagaswamy, was aware of a great change in him and on several occasions rebuked him for his detachment from all that was going on around him. About six weeks after Venkataraman’s absorption into the Self, on 29 August 1896, he was attempting to complete a homework assignment which had been given to him by his English teacher for indifference in his studies. Suddenly Venkataraman tossed aside the book and turned inward in meditation. His elder brother rebuked him again, asking, "What use is all this to one who is like this?", referring to his behaviour as a sadhu.[20][21] Venkataraman did not answer, but recognised the truth in his brother’s words.[web 9]

First years at Tiruvannamalai (1896–1899)

Journey to Tiruvannamalai (1896)

He decided to leave his home and go to Arunachala. Knowing his family would not permit this, he slipped away, telling his brother he needed to attend a special class at school. Fortuitously, his brother asked him to take five rupees and pay his college fees on his way to school. Venkataraman took out an atlas, calculated the cost of his journey, took three rupees and left the remaining two with a note which read:

I have set out in quest of my Father in accordance with his command. This (meaning his person) has only embarked on a virtuous enterprise. Therefore, no one need grieve over this act. And no money need be spent in search of this. Your college fee has not been paid. Herewith rupees two.[22]

On the morning of 1 September 1896, Venkataraman boarded the train and travelled to Tiruvannamalai, where he was to stay the rest of his life.

Arunachaleswara temple (1896–1897)

In Tiruvannamalai he went straight to the temple of Arunachaleswara. There, he entered the sanctum sanctorum and embraced the linga in ecstasy. The burning sensation that had started back at Madurai, which he later described as "an inexpressible anguish which I suppressed at the time", merged in Arunachaleswara.[web 9]

The first few weeks he spent in the thousand-pillared hall, but shifted to other spots in the temple and eventually to the Patala-lingam vault so that he might remain undisturbed. There, he would spend days absorbed in such deep samādhi that he was unaware of the bites of vermin and pests. Seshadri Swamigal, a local saint, discovered him in the underground vault and tried to protect him.[22] After about six weeks in the Patala-lingam, he was carried out and cleaned up. For the next two months he stayed in the Subramanya Shrine, so unaware of his body and surroundings that food had to be placed in his mouth or he would have starved.

Gurumurtam temple (1897–1898)

In February 1897, six months after his arrival at Tiruvannamalai, Ramana moved to Gurumurtam, a temple about a mile out of Tiruvannamalai.[23] Shortly after his arrival a sadhu named Palaniswami went to see him. Palaniswami's first darshan left him filled with peace and bliss, and from that time on he served Ramana, joining him as his permanent attendant. From Gurumurtam to Virupaksha Cave (1899–1916) to Skandasramam Cave (1916–22), he took care for Ramana. Besides physical protection, Palaniswami would also beg for alms, cook and prepare meals for himself and Ramana, and care for him as needed.[7] In May 1898 Ramana and Palaniswami moved to a mango orchard next to Gurumurtam.[24]

During this time, Ramana neglected his body, "completely disregarding his outward appearance".[25] He also neglected the ants which bit him incessantly.[26] Gradually, despite Ramana's desire for privacy, he attracted attention from visitors who admired his silence and austerities, bringing offerings and singing praises.[27] Eventually a bamboo fence was built to protect him.[27]

While living at Gurumurtam temple his family discovered his whereabouts. First his uncle Nelliappa Iyer came and pled with him to return home, promising that the family would not disturb his ascetic life. Ramana sat motionless and eventually his uncle gave up.[28]

Pavalakkunru temple (1898–1899)

In September 1898 Ramana moved to the Shiva-temple at Pavalakkunru, one of the eastern spurs of Arunachala. His mother and brother Nagaswami found him here in December 1898. Day after day his mother begged him to return, but no amount of weeping and pleading had any visible effect on him. She appealed to the devotees who had gathered around, trying to get them to intervene on her behalf until one requested that Ramana write out his response to his mother.[29] He then wrote on a piece of paper,

In accordance with the prarabdha (destiny to be worked out in current life) of each, the One whose function it is to ordain makes each to act. What will not happen will never happen, whatever effort one may put forth. And what will happen will not fail to happen, however much one may seek to prevent it. This is certain. The part of wisdom therefore is to stay quiet.[web 9]

At this point his mother returned to Madurai saddened.[web 9]

Arunachala (1899–1922)

Virupaksha Cave (1899–1916)

Soon after this, in February 1899, Ramana left the foothills to live on Arunachala itself.[30] He stayed briefly in Satguru Cave and Guhu Namasivaya Cave before taking up residence at Virupaksha Cave for the next 17 years, using Mango Tree cave during the summers, except for a six-month period at Pachaiamman Koil during the plague epidemic.[31]

In 1902, a government official named Sivaprakasam Pillai, with writing slate in hand, visited the young Swami in the hope of obtaining answers to questions about "How to know one's true identity". The fourteen questions put to the young Swami and his answers were Ramana's first teachings on Self-enquiry, the method for which he became widely known, and were eventually published as 'Nan Yar?', or in English, 'Who am I?’.[32]

Several visitors came to him and many became his devotees. Kavyakantha Sri Ganapati Sastri[note 13], a Vedic scholar of repute in his age with a deep knowledge of the Srutis, Sastras, Tantras, Yoga, and Agama systems, came to visit Ramana in 1907. After receiving instructions from him, he proclaimed him as Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. Ramana was known by this name from then on.[33]

In 1911 that the first westerner, Frank Humphreys, then a policeman stationed in India, discovered Ramana and wrote articles about him which were first published in The International Psychic Gazette in 1913.[note 14]

In 1912, while in the company of disciples, he was observed to undergo about a 15-minute period where he showed the outward symptoms of death, which reportedly resulted thereafter in an enhanced ability to engage in practical affairs while remaining in Sahaja Nirvikalpa Samadhi.

Skandashram (1916–1922)

In 1916 his mother Alagammal and younger brother Nagasundaram joined Ramana at Tiruvannamalai and followed him when he moved to the larger Skandashram Cave, where Bhagavan lived until the end of 1922. His mother took up the life of a sannyasin, and Ramana began to give her intense, personal instruction, while she took charge of the Ashram kitchen. Ramana's younger brother, Nagasundaram, then became a sannyasi, assuming the name Niranjanananda, becoming known as Chinnaswami (the younger Swami).

During this period, Ramana composed The Five Hymns to Arunachala, his magnum opus in devotional lyric poetry. Of them the first is Akshara Mana Malai.[translation 1] It was composed in Tamil in response to the request of a devotee for a song to be sung while wandering in the town for alms. The Marital Garland tells in glowing symbolism of the love and union between the human soul and God, expressing the attitude of the soul that still aspires.[web 11]

Mother's death (1922)

Beginning in 1920, his mother's health deteriorated. On the day of her death, 19 May 1922, at about 8 a.m., Ramana sat beside her. It is reported that throughout the day, he had his right hand on her heart, on the right side of the chest, and his left hand on her head, until her death around 8:00 p.m., when Ramana pronounced her liberated, literally, 'Adangi Vittadu, Addakam' (‘absorbed'). Later Ramana said of this: "You see, birth experiences are mental. Thinking is also like that, depending on sanskaras (tendencies). Mother was made to undergo all her future births in a comparatively short time."[web 12] Her body was enshrined in a samadhi, on top of which a Siva lingam was installed and given the name Matrbhuteshwara, Shiva manifesting as mother.[34][35] To commemorate the anniversary of Ramana Maharshi's mother's death, a puja, known as her Aradhana or Mahapooja, is performed every year at the Matrbhuteshwara.

Ramanashram (1922–1950)

From 1922 till his death in 1950 Ramana lived in Sri Ramanashramam, the ashram that developed around the mother's tomb.[36]

Commencement of Ramanashram (1920s)

Ramana often walked from Skandashram to mother's tomb. In December 1922 he didn't return to Skandashram, and settled at the base of the Hill, and Sri Ramanasramam started to develop. At first, there was only one hut at the samadhi, but in 1924 two huts, one opposite the samadhi and the other to the north, were erected. The so-called Old Hall was built in 1928. Ramana lived here until 1949.[37]

Sri Ramanasramam grew to include a library, hospital, post-office and many other facilities. Ramana displayed a natural talent for planning building projects. Annamalai Swami gave detailed accounts of this in his reminiscences.[38] Until 1938, Annamalai Swami was entrusted with the task of supervising the projects and received his instructions from Ramana directly.

Discovery by westerners (1930s)

In 1931 the classic biography of Ramana Maharshi, Self Realisation: The Life and Teachings of Ramana Maharshi, written by Narasimha Swami, was published.[39]

Ramana became relatively well known in and out of India after 1934 when Paul Brunton, having first visited Ramana in January 1931, published the book A Search in Secret India.[40] In this book he described his meeting with Ramana Maharshi, and the effect this meeting had on him. Brunton also describes how Ramana's fame had spread, "so that pilgrims to the temple were often induced to go up the hill and see him before they returned home"[41], and the talks Ramana had with a great variety of visitors and devotees.[42] Brunton calls Ramana "one of the last of India's spiritual supermen"[43], and describes his affection toward Ramana:

I like him greatly because he is so simple and modest, when an atmosphere of authentic greatness lies so palpably around him; because he makes no claims to occult powers and hierophantic knowledge to impress the mysteryloving nature of his countrymen; and because he is so totally without any traces of pretension that he strongly resists every effort to canonize him during his lifetime.[44]

While staying at Sri Ramanasramam, Brunton had an experience of a "sublimely all-embracing" awareness[45], a "Moment of Illumination".[46]

The book was a best-seller, and introduced Ramana Maharshi to a wider audience in the west.[39] Resulting visitors included Paramahansa Yogananda, Somerset Maugham (whose 1944 novel The Razor's Edge models its spiritual guru after Ramana),[web 13] Mercedes de Acosta and Arthur Osborne.

Later years (1940s)

In 1939 started the building of a temple which was erected over the mother's samadhi, called Mathrubhuteswara, "God in the form of the mother".[47]

Ramana's relative fame spread throughout the 1940s. However, even as his fame spread, his lifestyle remained that of a renunciate.

The 1940s saw many of Ramana's most ardent devotees pass away. These included Echamma (1945), attendant Madhavaswami (1946), Ramanatha Brahmachari (1946), Mudaliar Granny and Lakshmi (1948).[15]

In the late 1940s Arthur Osborne joined the ashram. He was the first editor of Mountain Path in 1964, the magazine published by Ramanashram.

Final years (1948–1950)

In November 1948, a tiny cancerous lump was found on Ramana's arm and was removed in February 1949 by the ashram's doctor. Soon, another growth appeared and another operation was done by an eminent surgeon in March 1949 with radium applied. The doctor told Ramana that a complete amputation of the arm to the shoulder was required to save his life, but he refused. A third and fourth operation were performed in August and December 1949, but only weakened him. Other systems of medicine were then tried; all proved fruitless and were stopped by the end of March when devotees gave up all hope. To devotees who begged him to cure himself for the sake of his followers, Ramana is said to have replied, "Why are you so attached to this body? Let it go" and "Where can I go? I am here."[14]

By April 1950, Ramana was too weak to go to the hall and visiting hours were limited. Visitors would file past the small room where he spent his final days to get one final glimpse. Swami Satyananda, the attendant at the time, reports,

On the evening of 14 April 1950, we were massaging Ramana's body. At about 5 o'clock, he asked us to help him to sit up. Precisely at that moment devotees started chanting 'Arunachala Siva, Arunachala Siva'. When Ramana heard this his face lit up with radiant joy. Tears began to flow from his eyes and continued to flow for a long time. I was wiping them from time to time. I was also giving him spoonfuls of water boiled with ginger. The doctor wanted to administer artificial respiration but Ramana waved it away. Ramana’s breathing became gradually slower and slower and at 8:47 p.m. it subsided quietly.[citation needed]

Henri Cartier-Bresson, the French photographer, who had been staying at the ashram for a fortnight prior to Ramana’s death, recounted the event:

"It is a most astonishing experience. I was in the open space in front of my house, when my friends drew my attention to the sky, where I saw a vividly-luminous shooting star with a luminous tail, unlike any shooting star I had before seen, coming from the South, moving slowly across the sky and, reaching the top of Arunachala, disappeared behind it. Because of its singularity we all guessed its import and immediately looked at our watches – it was 8:47 – and then raced to the Ashram only to find that our premonition had been only too sadly true: the Master had passed into parinirvana at that very minute." Ramana Maharshi was 71 years old at the time of his death.[48]

Cartier-Bresson took some of the last photographs of Ramana on 4 April 1950, and went on to take pictures of the mahasamadhi preparations.

The New York Times in its article dated 16 April 1950,concluded:

Here in India, where thousands of so-called holy men claim close tune with the infinite, it is said that the most remarkable thing about Ramana Maharshi was that he never claimed anything remarkable for himself, yet became one of the most loved and respected of all.[49] [web 14][web 15]

Charisma

Ramana Maharshi was a charismatic person[50][51], who attracted many devotees.

Devotion for Ramana Maharshi

Early on, Ramana was worshipped by his devotees. People came to Ramana Maharshi for darshana[52], devotion to God by looking at him in the person of a guru or incarnation.[53][54] Objects being touched or used by him were highly valued by his devotees, "as they considered it to be prasad and that it passed on some of the power and blessing of the Guru to them".[55] People also tried to touch his feet[7], which is also considered to be darshana.[56] Also the water which he used to wash his hands was valued. The bathing-water he used became an object for achamaniyam, "sipping drops of water for religious purpose".[57] Sri Ramana strongly discouraged this type of activity, and constantly reminded people to turn within.[citation needed] While he spoke highly of the power of being in the physical proximity of a guru, he also said that physical contact with the guru was not necessary.[citation needed] When one devotee asked if it would be possible to prostrate before Sri Ramana and touch his feet, he replied,

The real feet of Bhagavan exist only in the heart of the devotee. To hold onto these feet incessantly is true happiness. You will be disappointed if you hold onto my physical feet because one day this physical body will disappear. The greatest worship is worshipping the Guru's feet that are within oneself.[58]

In later life, the amount of devotees and their devotion became so extensive that Ramana became restricted in his daily routine.[59] Measures had to be taken to prevent people touching him.[60] Several times Ramana tried to escape from the ashram, to return to a life of solitude. Vasudeva reports:

Bhagavan sat on a rock and said with tears in his eyes that he would never again come to the Ashram and would go where he pleased and live in the forests or caves away from all men.[61]

Ramana did return to the ashram, but has also reported himself on attempts to leave the ashram:

I tried to be free on a third occasion also. That was after mother's passing away. I did not want to have even an Ashram like Skandashram and the people that were coming there then. but the result has been this Ashram [Ramanashram] and all the crowd here. Thus all my three attempts failed.[61]

How Sri Ramana Lived

Ramana was noted for his belief in the power of silence and his relatively sparse use of speech, as well as his lack of concern for fame or criticism.[web 16]

Ramana was noted for his unusual love of creatures and plants.[note 15] On the morning of 18 June 1948, he realised his favourite cow Lakshmi was near death. Just as he had with his own Mother, Ramana placed his hands on her head and over her heart. The cow died peacefully at 11:30 a.m. and Ramana later declared that the cow was liberated.[web 17]

He led a modest and renunciate life. However, a popular image of him as a person who spent most of his time doing nothing except silently sitting in samadhi is highly inaccurate, according to David Godman, who has written extensively about Ramana. According to Godman, from the period when an Ashram began to rise around him after his mother arrived into his later years, Ramana was actually quite active in Ashram activities such as cooking and stitching leaf plates until his health failed.[web 18]

Lineage

Sri Ramana did not create any lineage

Ramana did not publicise himself as a guru[63], never claimed to have disciples,[web 19] and never appointed any successors.[web 20][web 21][web 22][note 16] While a few who came to see him are said to have become enlightened through association[citation needed][note 17], he did not publicly acknowledge any living person as liberated[web 19] other than his mother at death.[64] Ramana never promoted any lineage.[web 20][note 18]

With regard to Sri Ramana Ashram, Sri Ramana had in 1938 executed a legal will bequething all the Ramanashram properties to his younger brother Niranjanananda and his descendants. The Ramanashram as in 2013 is run by Sri Niranjananda's grandson Sri V.S. Raman. Ramanashram is legally recognised as a public religious trust whose aim was to maintain Ramanasramam in a way that was consonant with Sri Ramana's declared wishes that is the ashram should remain open as a spiritual institution so that anyone who wished to could avail themselves of its facilities. [65] [66] [67]

Sri Ramana was not part of any lineage

Although Ramana's teachings have often been labelled as Advaita Vedanta[68], he never received initiation into the Dashanami Sampradaya or any other sampradaya[note 19] as a sannyasin.[web 21][70][web 20][note 20] A sannyasin belonging to the Sringeri Sharada Peetham, one of the monasteries founded by Adi Shankara, once tried to persuade Ramana to be initiated into sannyasa, but Ramana refused.[70] In the Arunachala Puranam[translation 2], left behind by an old man, Ramana found the following verse:

Those who reside within the radius of three yojanas (30 miles) of this place [Arunachala], even if they have not had initiation, shall by my supreme decree attain Liberation, free from all attachments.[70]

Ramana copied this verse on a slip of paper, and when the sannyasin returned, Ramana showed the verse, where-after the sannyasin gave up and left.[70]

Context

C.G. Jung objected to regarding Ramana as an "isolated phenomenon"[71] Jung wrote the foreword to Heinrich Zimmer's Der Weg zum Selbst, "The Path to the Self" (1944)[71], an early collection of translations of Ramana's teachings in a western language. According to Wehr, Jung regarded Ramana Maharshi not to be an "isolated phenomenon"[71], but a token of Indian spirituality, "manifest in many forms in everyday Indian life":[71]

He is of a type that has always existed and always will. Therefore it was not necessary to seek him out... He is merely the whitest spot on a white surface.[72][note 21][note 22]

Alan Edwards has placed Ramana Maharshi in the context of western Orientalism, arguing that

...scholarship can misinterpret and misrepresent religious figures because of the failure to recognise the presence of [Orientalist stereotypes] and assumptions, and also because of the failure to maintain critical distance when dealing with the rhetoric of devotional literature."[web 25][note 23]

Indian context

According to Zimmer and Jung, Ramana's appearance as a mauni, a silent saint absorbed in samadhi, fitted into pre-existing Indian notions of holiness.[74][75] They placed the Indian devotion toward Ramana Maharshi in this Indian context.[75][71][note 24]

Tamil culture has a long tradition of devotional spiritual practices[77][78][79] and non-monastic religious authority[80], such as the Nayanars and the Siddhas. Ramana himself considered God, Guru and Self to be the manifestations of the same reality.[web 27] One of these manifestations is the mountain Arunachala, which is considered to be the manifestation of Shiva.[81][82] It can be worshipped through the mantra "Om arunachala shivaya namah!"[83] and by Pradakshina, walking around the mountain, a practice which was often performed by Ramana.[82] Ramana considered Arunachala to be his Guru.[82][84] Asked about the special sanctity of Arunachala, Ramana said that Arunachala is Shiva himself.[85][note 25] In his later years, Ramana said it was the spiritual power of Arunachala which had brought about his Self-realisation.[81] He composed the Five Hymns to Arunachala as devotional song.[82] In later life, Ramana himself came to be regarded as Dakshinamurthy[86][87],[web 20] an aspect of Shiva as a guru.

Western context

In the 1930s Ramana Maharshi's teachings were brought to the west by Paul Brunton in his A Search in Secret India.[88] When this book was published in 1934, the western world had already been exposed to Indian religious thought for 150 years.[89] In 1785 appeared the first western translation of a Sanskrit-text.[89] It marked the growing interest in the Indian culture and languages.[90] The first translation of Upanishads appeared in two parts in 1801 and 1802[90], which influenced Arthur Schopenhauer, who called them "the consolation of my life".[91][note 26] Early translations also appeared in other European languages.[92]

A major force in the mutual influence of eastern and western ideas and religiosity was the Theosophical Society[93][73], of which Paul Brunton also had been a member. It searched for ancient wisdom in the east, spreading eastern religious ideas in the west.[94] One of its salient features was the belief in "Masters of Wisdom"[95][note 27], "beings, human or once human, who have transcended the normal frontiers of knowledge, and who make their wisdom available to others".[95] The Theosophical Society also spread western ideas in the east, aiding a modernisation of eastern traditions, and contributing to a growing nationalism in the Asian colonies.[96][note 28] Another major influence was Vivekananda[101][102], who popularised his modernised inerpretation[103] of Advaita Vedanta in the 19th and early 20th century in both India and the west[102], emphasising anubhava ("personal experience"[104] over scriptural authority.[104]

Brunton also wasn't the first westerner who searched for masters in India.[105] Renard mentions Edward Carpenter as the most remarkable example, who wrote about his visit to a "Gnani" (jnani) in his "Adam's Peak to Elephanta, published in 1892.[106]

Jung and Zimmer were two of the first westerners to pick up Ramana's teachings. Jung also wrote,

The life and teachings of Sri Ramana are important not only for the Indian but also for the Westerner. Not only do they form a record of great human interest, but also a warning message to a humanity which threatens to lose itself in the chaos of its unconsciousness and lack of control.[citation needed]

Stimulated by Arthur Osborne, in the 1960s Bhagawat Singh actively started to spread Ramana Maharshi's teachings in the USA.[88] Since the 1970s western interest in Asian religions has seen a rapid growth. Ramana Maharshi's teachings have been further popularised in the west as neo-Advaita via H. W. L. Poonja and his students.[107][108]

Upadesa – teachings and instructions

Ramana gave upadesa, "instruction or guidance given to a disciple by his Guru",[web 29] pointing to the true Self of the devotees and showing them the truth of it.[109]

Early on, Ramana attracted devotees who would sit in his company, and ask him questions. Several devotees recorded the answers to their own specific questions, or kept the sheets of paper on which Ramana answered, and had them later published.[110] Other devotees recorded the talks between Ramana and devotees, a large amount of which have also been published.[web 2]

Though his teaching is consistent with and generally associated with Hinduism, the Upanishads and Advaita Vedanta, there are some differences with the traditional Advaitic school. Ramana gave his approval to a variety of paths and practices from various religions.[web 2]

Silence

Ramana's main means of instruction of his devotees was through silence:[web 30][111]

Sri Ramana used words sparingly and gave his most profound instruction in silence.[112]

His method of teaching has been compared to Dakshinamurti, Shiva in the ascetic appearance of the Guru, who teaches through silence:

One evening, devotees asked Sri Ramana to explain the meaning of Shankara's hymn in praise of Dakshinamurti (Dakshinamurthy Stotram). They waited for his answer, but in vain. The Maharishi sat motionless on his seat, in total silence.[113][note 29]

Commenting on the Dakshinamurti Stotra, Ramana said:

Silence is the true upadesa. It is the perfect upadesa. It is suited only for the most advanced seeker. The others are unable to draw full inspiration from it. Therefore, they require words to explain the Truth. But Truth is beyond words; it does not warrant explanation. All that is possible is to indicate It. How is that to be done?[114]

Self-enquiry

Ramana urged people who came to him to practice self-enquiry. He directed people to look inward rather than seeking outside themselves for Realization: "The true Bhagavan resides in your Heart as your true Self. This is who I truly am".[citation needed] Ramana's teachings about self-enquiry have been classified as the Path of Knowledge (Jnana marga) among the Indian schools of thought.

Questioning "Who am I?"

In response to questions on self-liberation and the classic texts on Yoga and Vedanta, Ramana recommended self-enquiry as the means to awaken to the "I-I"[web 1][note 30] and the Self:[11][note 31][note 32]

Enquiry in the form 'Who am I' alone is the principal means. To make the mind subside, there is no adequate means other than self-enquiry. If controlled by other means, mind will remain as if subsided, but will rise again".[note 33]

Basically "self-enquiry" is the constant attention to the inner awareness of "I" or "I am").[note 34][note 35] Sri Ramana Maharshi frequently recommended it as the most efficient and direct way of discovering the unreality of the ‘I'-thought. Enquiring the "I"-thought, one realises that it raises in the hṛdayam (heart[note 36]). The 'I'-thought will disappear and only "I-I"[web 33] or Self-awareness remains, which is Self-realization or liberation:[web 34]

What is finally realized as a result of such enquiry into the Source of Aham-vritti (I-thought) is verily the Heart as the undifferentiated Light of Pure Consciousness, into which the reflected light of the mind is completely absorbed.[116]

Ramana warned against considering self-enquiry as an intellectual exercise. Properly done, it involves fixing the attention firmly and intensely on the feeling of 'I', without thinking. Attention must be fixed on the 'I' until the sense of "I" disappears and the Self is realised.

Ramana's written works contain terse descriptions of self-enquiry. Verse thirty of Ulladu Narpadu:

Questioning 'Who am I?' within one's mind, when one reaches the Heart, the individual 'I' sinks crestfallen, and at once reality manifests itself as 'I-I'. Though it reveals itself thus, it is not the ego 'I' but the perfect being the Self Absolute.[web 33]

Verses nineteen and twenty of Upadesa Undiyar describe the same process in almost identical terms:

19. 'Whence does the 'I' arise?' Seek this within. The 'I' then vanishes. This is the pursuit of wisdom.

20. Where the 'I' vanished, there appears an 'I-I' by itself. This is the infinite.[web 33]

Ramana considered the Self to be permanent and enduring[117], surviving physical death.[118] "The sleep, dream and waking states are mere phenomena appearing on the Self"[119], as is the "I"-thought.[117] Our "true nature" is "simple Being, free from thoughts".[120]

Ramana's own death experience when he was 16 already contains the practice of self-enquiry. After raising the question 'Who am I?' he "turned his attention very keenly towards himself".[citation needed]

Nan Yar?

His earliest teachings are documented in the book Nan Yar? (Who am I?), in which he elaborates on the "I" and Self-enquiry:[note 37]

- "Of all the thoughts that rise in the mind, the thought 'I' is the first thought."

- "What is called mind is a wondrous power existing in Self. It projects all thoughts. If we set aside all thoughts and see, there will be no such thing as mind remaining separate; therefore, thought itself is the form of the mind. Other than thoughts, there is no such thing as the mind."

- "That which rises in this body as 'I' is the mind. If one enquires 'In which place in the body does the thought 'I' rise first?', it will be known to be in the heart [spiritual heart is 'two digits to the right from the centre of the chest']. Even if one incessantly thinks 'I', 'I', it will lead to that place (Self)'."

- "The mind will subside only by means of the enquiry 'Who am I?'. The thought 'Who am I?', destroying all other thoughts, will itself finally be destroyed like the stick used for stirring the funeral pyre."

- "If other thoughts rise, one should, without attempting to complete them, enquire, 'To whom did they arise?', it will be known 'To me'. If one then enquires 'Who am I?', the mind (power of attention) will turn back to its source. By repeatedly practising thus, the power of the mind to abide in its source increases."

- "Knowledge itself is 'I'. The nature of (this) knowledge is existence-consciousness-bliss."

- "The place where even the slightest trace of the 'I' does not exist, alone is Self."

- "The Self itself is God."

Bhakti

Although he advocated self-enquiry as the fastest means to realisation, he also recommended the path of bhakti and self-surrender (to one's deity or guru) either concurrently or as an adequate alternative, which would ultimately converge with the path of self-enquiry.[122]

Bhakti can be done in four ways:[web 35][123]

- To the Supreme Self (Atma-Bhakti)

- To God or the Cosmic Lord as a formless being (Ishvara-Bhakti)

- To God in the form of various Gods or Goddesses (Ishta Devata-Bhakti)

- To God in the form of the Guru (Guru-Bhakti)

Influences

Throughout his life, through contact with educated devotees like Ganapata Muni[124], Ramana Maharshi became acquainted with works on Shaivism and Advaita Vedanta, and used them to explain his insights:[125]

People wonder how I speak of Bhagavad Gita, etc. It is due to hearsay. I have not read the Gita nor waded through commentaries for its meaning. When I hear a sloka (verse), I think its meaning is clear and I say it. That is all and nothing more.[126]

Study through devotees

Already in 1896, a few months after his arrival at Arunachala, Ramana attracted his first disciple, Uddandi Nayinar[127], who recognised in the him "the living embodiment of the Holy Scriptures".[128] Uddandi was well-versed in classic texts on Yoga and Vedanta, and recited texts as the Yoga Vasistha and Kaivalya Navaneeta in Ramana's presence.[128]

In 1897 Ramana was joined by Palaniswami, who became his attendant.[129] Palaniswami studied books in Tamil on Vedanta, such as Kaivalya Navaneeta, Shankara's Vivekachudamani, and Yoga Vasistha. He had difficulties understanding Tamil. Ramana read the books too, and explained them to Palanaswami.[130]

As early as 1900, when Ramana was 20 years old, he became acquainted with the teachings of the Hindu monk and Neo-Vedanta[131][132][note 38] teacher Swami Vivekananda through Gambhiram Seshayya. Seshayya was interested in yoga techniques, and "used to bring his books and explain his difficulties".[133] Ramana answered on small scraps of paper, which were collected after his death in the late 1920s in a booklet called Vichara Sangraham, "Self-enquiry".[133]

Referred works

Ramana often mentioned and encouraged the study of the following classical works[124] which are associated with Advaita Vedanta and Shaivism:

- Bhagavad Gita[124]

- Ribhu Gita[124] and the "Essence of Ribhu Gita"

- Works of Shankara[124], such as

- Yoga Vasista Sara[124]

- Ashtavakra Gita[124]

- Tripura Rahasya[translation 6]

- Ellam Ondre[124][translation 7]

- Kaivalya Navaneetam[124][translation 8]

- Advaita Bodha Deepika[translation 9]

- Periya Puranam, the stories of the 63 Tamil saints[136][137]

Shaivism

Though Ramana's teachings are often considered to be akin to Vedanta, his spiritual life is also associated with Shaivism.[note 40] In contrast to Shankara's Vedanta, which speaks of Maya and sees "this world as a trap and an illusion, Shaivism says it is the embodiment of the Divine".[139] It speaks of "the Goddess Shakti, or spiritual energy, portrayed as the Divine Mother who redeems the material world".[139]

Shaiva Siddhanta, the Shaivism which is prevalent in Tamil Nadu, combines the original emphasis on ritual fused with an intense devotional tradition expressed in the bhakti poetry of the Nayanars.[140] The Tamil compendium of devotional songs known as Tirumurai, along with the Vedas, the Shaiva Agamas and "Meykanda" or "Siddhanta" Shastras, form the scriptural canon of Tamil Shaiva Siddhanta.[141]

Osborne notes that Ramana was born at Arudra Darshan, the day of the 'Sight of Siva'[web 5]

As a youth, prior to his awakening, Ramana read the Periya Puranam, the stories of the 63 Tamil saints.[136][translation 10] In later life, he told those stories to his devotees:

When telling these stories, he used to dramatize the characters of the main figures in voice and gesture and seemed to identify himself fully with them.[124]

In later life, he came to be regarded as a Dakshinamurthy,[web 9] an aspect of Shiva as a guru of all types of knowledge, and bestower of jnana. This aspect of Shiva is his personification as the supreme or the ultimate awareness, understanding and knowledge.[142] This form represents Shiva in his aspect as a teacher of yoga, music, and wisdom, and giving exposition on the shastras.

Ramana considered the Self to be his guru, in the form of the sacred mountain Arunachala, where he spent his adult life.[143] Arunachala is a holy hill at Thiruvannamalai in Tamil Nadu, where the Annamalaiyar Temple, a temple of Lord Shiva is located. It is one of the five main shaivite holy places in South India.[144].

One of the works that Ramana used to explain his insights was the Ribhu Gita, a song at the heart of the Shivarahasya Purana, one of the 'Shaiva Upapuranas' or ancillary Purana regarding Shiva and Shaivite worship. Another work used by him was the Dakshinamurthy Stotram, a text by Shankara.[124] It is a hymn to Shiva, explaining Advaita Vedanta.

Vedanta

Ramana's teachings are often interpreted as Advaita Vedanta, though Ramana Maharshi never "received diksha (initiation) from any recognised authority".[web 20][note 41][note 42] It was via his devotees that he became acquainted with classic texts on Yoga and Vedanta.[7][149] Ramana himself did not call his insights advaita:

D. Does Sri Bhagavan advocate advaita?

M. Dvaita and advaita are relative terms. They are based on the sense of duality. the Self is as it is. There is neither dvaita nor advaita. "I Am that I Am."[note 43] Simple Being is the Self.[151]

There are differences with the traditional Advaitic school. Advaita recommends a negationist neti, neti (Sanskrit, "not this", "not this") path[note 44], or mental affirmations that the Self was the only reality, such as "I am Brahman" or "I am He". Ramana advocated the enquiry "Nan Yar" (Tamil, "Who am I").

And Sri Ramana, unlike the traditional Advaitic school, strongly discouraged devotees from adopting a renunciate lifestyle and renouncing their responsibilities. To one devotee who felt he should abandon his family, whom he described as "samsara" (illusion), to intensify his spiritual practice, Sr Ramana replied,

Oh! Is that so? What really is meant by samsara? Is it within or without? Wife, children and others. Is that all the samsara? What have they done? Please find out first what really is meant by samsara. Afterwards we shall consider the question of abandoning them.[153]

Notable devotees

Over the course of Ramana's lifetime, people from a wide variety of backgrounds, religions, and countries were drawn to him. Some stayed for the rest of their lives (or his) and served him with great devotion, and others came for a single darshan and left, deeply affected by the peace he radiated.

Quite a number of devotees wrote books conveying Ramana's teachings:

- Muruganar (1893–1973), one of Ramana's foremost devotees who lived as Ramana's shadow for 26 years,[web 38] recorded the most comprehensive collection of Ramana's sayings in a work called Guru Vachaka Kovai, "The Garland of Guru's Sayings".[web 39][translation 11] Ramana carefully reviewed this work with Muruganar, modifying many verses to most accurately reflect his teaching, and adding in additional verses.[note 45]

- Muruganar was also instrumental in Ramana's writing of Upadesa Saram, "The Essence of Instruction", and Ulladu Narpadu, "Forty Verses on Reality".

- Gudipati Venkatachalam (1894 to 1976), a noted Telugu writer lived the later part of his life and died near Ramana Maharshi's ashram in Arunachalam.

- Sri Sadhu Om (1922–1985) spent five years with Ramana and about 28 years with Muruganar. His deep understanding of Ramana's teachings on self-enquiry are explained in his book The Path of Sri Ramana – Part One.[28][note 46]

- Suri Nagamma wrote a series of letters to her brother in Telugu, describing Ramana's conversations with devotees over a five-year period. Each letter was corrected by Ramana before it was sent.

Several western authors were instrumental in gaining western attention for Ramana Maharshi:

- Paul Brunton's writings about Ramana brought considerable attention to him in the West;

- Arthur Osborne, the first editor of the ashram journal, The Mountain Path);

- Major Chadwick, who ran the Veda Patasala during Ramana's time);

- Ethel Merston;

- S.S. Cohen;

- David Godman, a former librarian at the ashram, has written about Ramana's teaching, as well as a series of books (The Power of the Presence) vividly portraying the lives of a number of lesser-known attendants and devotees of Ramana.

H. W. L. Poonja and his students have been instrumental in the further popularisation of Ramana through the so-called Neo-Advaita or Satsang-movement.[107][108] The Neo-Advaita movement has been criticised for its emphasis on insight alone, omitting the preparatory practices,[web 40][web 41] and Poonja has been sharply criticised for too easily authorising students to teach.[154] Nevertheless, Neo-Advaita has become an important constituent of popular western spirituality.[155]

Attendants of Ramana included Palaniswami (from 1897), Kunju Swami (from 1920), Madhava Swami, Ramanatha Brahmachari, Krishnaswami, Rangaswamy, Sivananda, Krishna Bhikshu and Annamalai Swami (from 1928). The devoted ladies who cooked for Bhagavan and his devotees in the ashram kitchen include Shantamma, Sampurnamma, Subbalakshmi Ammal, Lokamma, and Gowri Ammal.

Swami Ramdas visited Ramana Maharshi while on pilgrimage in 1922, and after darshan, spent the next 21 days meditating in solitude in a cave on Arunachala. Thereafter, he attained the direct realisation that "All was Rama, nothing but Rama".[web 42]

William Somerset Maugham, the English author, wrote a chapter entitled "The Saint" in his last book "Points of View." This chapter is devoted to Ramana Maharshi, whom Maugham had at one time visited before Indian independence.

Indian National Congress politician and freedom-fighter, O. P. Ramaswamy Reddiyar, who served as the Premier of Madras from 1947 to 1949, was also a devoted follower of Ramana Maharshi. Ramaswami Pillai, Balarama Reddy, Ramani Ammal, Kanakammal, Meenakshi Ammal, Perumalswami and Rayar are some of the other long standing devotees who came into the Sannadhi of Bhagavan during his life at Sri Ramanasramam.

Maurice Frydman (a.k.a. Swami Bharatananda), a Polish Jew who later translated Nisargadatta Maharaj's work "I Am That" from Marathi to English, was also deeply influenced by Ramana's teachings. Many of the questions published in Maharshi's Gospel (1939) were put by Maurice, and they elicited detailed replies from the Maharshi. About Frydman, Sri Ramana had remarked "He (Maurice Frydman) belongs only here (to India). Somehow he was born abroad, but has come again here." [web 43]

Works

Writings

Ramana "never felt moved to formulate his teaching of his own accord, either verbally or in writing".[110] The few writings he is credited with "came into being as answers to questions asked by his disciples or through their urging".[110] Only a few hymns were written on his own initiative.[110].

Writings by Ramana are:

- Collected works.[web 44]

- Gambhiram Sheshayya, Vichāra Sangraham, "Self-Enquiry". Answers to questions, compiled in 1901, published in dialogue-form, republished as essay in 1939 as A Cathechism of Enquiry. Also published in 1944 in Heinrich Zimmer's Der Weg zum Selbst.[156][web 45]

- Sivaprakasam Oillai, Nān Yār?, "Who am I?". Answers to questions, compiled in 1902, first published in 1923.[156][web 46][web 47]

- Five Hymns to Arunachala:

- Akshara Mana Malai, "The Marital Garland of Letters". In 1914, at the request of a devotee, Ramana wrote Akshara Mana Malai for his devotees to sing while on their rounds for alms. It's a hymn in praise of Lord Shiva, manifest as the mountain Arunachala. The hymn consists of 108 stanzas composed in poetic Tamil.[web 48][web 49]

- Navamani Mālai, "The Necklet of Nine Gems".[web 50]

- Arunāchala Patikam, "Eleven Verses to Sri Arunachala".[web 51]

- Arunāchala Ashtakam, "Eight Stanzas to Sri Arunachala".[web 52]

- Arunāchala Pañcharatna, "Five Stanzas to Sri Arunachala".[web 53]

- Sri Muruganar and Sri Ramana Maharshi, Upadesha Sāra (Upadesha Undiyar), "The Essence of Instruction". In 1927 Muruganar started a poem on the Gods, but asked Ramana to write thirty verses on upadesha, "teaching" or "instruction".[157][web 54]

- Ramana Maharshi, Ulladu narpadu, "Forty Verses on Reality". Written in 1928.[158] First English translation and commentary by S.S. Cohen in 1931.[web 55]

- Ullada Nārpadu Anubandham, "Reality in Forty Verses: Supplement". Forty stanzas, fifteen of which are being written by Ramana. The other twenty-five are translations of various Sanskrit-texts.[159][web 56]

- Sri Muruganar and Sri Ramana Maharshi (1930's), Ramana Puranam.[web 57]

- Ekātma Pañchakam, "Five Verses on the Self". Written in 1947, on request of a female devotee.[160][web 58]

Recorded talks

Several collections of recorded talks, in which Ramana used Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam,[web 2] have been published. Those are based on written transcripts, which were "hurriedly written down in English by his official interpreters".[web 2][note 47]

- Sri Natanananda, Upadesa Manjari, "Origin of Spiritual Instruction". Recordings of one day of conversations between Ramana and devotees.[web 59] First published in English in 1939 as "A Catechism of Instruction".[web 60]

- Munagala Venkatramaiah, Talks with Sri Ramana. Talks recorded between 1935 and 1939. Various editions:

- Print: Venkatramaiah, Munagala (2000), Talks With Sri Ramana Maharshi: On Realizing Abiding Peace and Happiness, Inner Directions, ISBN 1-878019-00-7

- Online: Venkatramaiah, Munagala (2000), Talks with Sri Ramana. Three volumes in one. Extract version (PDF), Tiruvannamalai: Sriramanasasram

- Venkataramiah, Muranagala (2006), Talks With Sri Ramana Maharshi (PDF), Sri Ramanasramam

- Devaraja Mudaliar, A. (2002), Day by Day with Bhagavan. From a Diary of A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR. (Covering March 16, 1945 to January 4, 1947) (PDF), ISBN 81-88018-82-1 Talks recorded between 1945 and 1947.

- Natarajan (1992), A Practical Guide to Know Yourself: Conversations with Sri Ramana Maharshi, Ramana Maharshi Centre for Learning, ISBN 81-85378-09-6

Compendia and expositions

- Paul Brunton (1934), A Search in Secret India The book credited with introducing Bhagavan to followers in the West

- David Godman, Be as You Are: The Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi (ISBN 0-14-019062-7)

- Sri Sadhu Om (2005-A), The Path of Sri Ramana, Part One (PDF), Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramana Kshetra, Kanvashrama

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Sri Sadhu Om (2005-B), The Path of Sri Ramana, Part Two (PDF), Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramana Kshetra, Kanvashrama

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Devaraja Mudaliar, A. (1999), GEMS FROM BHAGAVAN. A necklace of sayings by BHAGAVAN SRI RAMANA MAHARSHI on various vital subjects. Strung together by A. DEVARAJA MUDALIAR (PDF), Tiruvannamalai: Sriramanasasram, ISBN 8188018058

- Matthew Greenblatt (2002), The Essential Teachings of Ramana Maharshi: A Visual Journey (ISBN 1-878019-18-X)

- Sri Muruganar, edited by David Godman, Padamalai: Teachings of Ramana Maharshi (ISBN 0971137137)

- Editor unknown, The Spiritual Teaching of Ramana Maharshi. With a foreword by C.G. Jung. Shambhala. ISBN 1-59030-139-0.

- Michael James (2012), Happiness and the Art of Being. An Introduction to the Philosophy and Practice of the Spiritual Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana. ISBN 1-4251-2465-8

- Sri Ramana Maharshi, Gambhiram Seshayya (2005). Essence of Enquiry – Vichara Sangraham (A Commentary) (First ed.). Bangalore: Ramana Maharshi Centre for Learning. p. 223. ISBN 9788188261260.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Biographies

- Narasimha Swami (2002), Self Realisation: The Life and Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi, Sri Ramanasraman, ISBN 8188225746 Classic biography of Ramana Maharshi, first published in 1931.[39]

- Brunton, Paul, Maharshi and His Message A reprint of three chapters of A Search in Secret India,[web 61] which was first published in 1935 and introduced Ramana Maharshi to a western audience.[39].

- Osborne, Arthur (2002), Ramana Maharshi and the Path of Self-Knowledge, Tiruvannamalai: Sriramanasasram. Biography by Arthur Osborne, the first editor of Mountain Path, the magazine published by Ramanashram. First published in 1954.

- Natarajan, A.R. (2006), Timeless in Time: Sri Ramana Maharshi, ISBN 81-85378-82-7 Illustrated biography, first published in 1999.

- Ebert, Gabriele (2006), Ramana Maharshi: His Life, Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1411673502

- Visvanathan, Susan (2010),The Children of Nature: The Life and Legacy of Ramana Maharshi.New Delhi:Roli/Lotus

Reminiscences

- Paul Brunton (1935), A Search in Secret India. This book introduced Ramana Maharshi to a western audience.[39]

- Cohen, S.S. (2003), Guru Ramana (PDF), Sri Ramanashram First published 1956.

- Chadwick, Major A. W. (1961), A Sadhu's Reminiscences of Ramana Maharshi (PDF), Sri Ramanashram

- Nagamma, Suri (1973), Letters from Ramanasram by Suri Nagamma, Tiruvannamalai: Sriramanasasram

- Kunjuswami, Living with the Master. Recordings of Kunjuswami's experiences with Ramana Maharshi from 1920 on.[web 62] ISBN 81-88018-99-6

- G. V. Subbaramayya, Sri Ramana Reminiscences. "The account covers the years between 1933 and 1950".[web 63]

Books on devotees

- Ramana Pictorial Souvenir Commemorating the Kumbhabhishekam on 18-6-1967, Tiruvannamalai, India: Board of Trustees Sri Ramanasramam, 1969, OCLC 140712 Anonymously edited volume with many appreciations and reminiscences from others, plus many quotes from Ramana Maharshi

- V. Ganesan (1990), Moments Remembered, Reminiscences of Bhagavan Ramana. "Compilation of individual experiences of many, many devotees of Sri Ramana Maharshi".[web 64] ISBN 978-8188018437

- David Godman, Living by the Words of Bhagavan. "Account of the trials and tribulations of Annamalai Swami's life with Bhagavan".[web 65]

- David Godman, The Power of the Presence. Three parts. "Lengthy first-person accounts by devotees whose lives were transformed by Ramana Maharshi".[web 66]

For children

- Sri Ramana, Friend of Animals: Hobbler and the Monkeys of Arunachala (ISBN 81-8288-047-5)

- Sri Ramana, Friend of Animals: The Life of Lakshmi the Cow

- Ramana Thatha (Grand Father Ramana), by Kumari Sarada (ISBN 81-85378-03-7)

- Ramana Maharshi (Amar Chitra Katha: The Glorious Heritage of India series) (ISBN 81-7508-048-5)

- The Boy Sage, by Geeta Bhatt (author), S.K. Maithreyi (Illustrator) (ISBN 978-8182881129)

Documentary

Translations of Indian texts

- ^ Marital Garland of Letters

- ^ Arunachala Puranam, Chapter Two

- ^ Shankaracharya's Hymn to Dakshinamurti. Translation by Ramana Maharshi

- ^ Vivekachudamani. Translation by Ramana Maharshi

- ^ Atma Bodha, "Knowledge of the Self". Translation by Ramana Maharshi

- ^ Tripura Rahasya. Chapters I – XV of XXII

- ^ Ellam Ondre

- ^ Kaivalya Navaneeta, The Cream of Emancipation

- ^ Advaita Bodha Deepika

- ^ SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA, "SIXTY-THREE NAYANAR SAINTS"

- ^ Happines of Being, Guru Vachaka Kovai

See also

Notes

- ^ Also commonly spelled as Tiruchuzhi

- ^ Though many people have reported brief experiences of this, in Venkataraman's case it was permanent and irreversible. From that moment on, his sense of being an individual person ceased and never functioned in him again.[3]

- ^ Ramana: "When I later in Tiruvannamalai listened, how the "Ribhu Gita" and such sacred texts were read, I caught these things and discovered that these books named and analysed, what I before involuntarily felt, without being able to appoint or analyse. In the language of these books I could denote the state in which I found myself after my awakening as "cleaned understanding" (shuddham manas) or "Insight" (Vijñāna): as 'the intuition of the Enlightened'".[4]

- ^ Bhagavan means God, Sri is an honorific title, Ramana is a short form of Venkataraman, and Maharshi means 'great seer' in Sanskrit.

- ^ Ramana Maharshi: "Liberation (mukti) is the total destruction of the I-impetus (aham-kara), of the "me"- and "my"-impetus (mama-kara)".[12]

- ^ Ramana was born at 12:19 am, which per Vedic Astrology indicates a Virgo Ascendant with Most Effective Point (MEP)[web 3] at 18d 37' in the Hasta naksatra, and with the natal Moon[web 4] in the janmanaksatra Purarvasu.[13]

- ^ Narasimha Swami came to the Ashram in 1925; his biography of Ramana was published in 1931. Narasimha did not record the exact words of Ramana:[17] "The account in the book was not a direct transcription of Bhagavan’s words, and the author makes this clear in a footnote which has appeared in most of the editions of the book. He said that he was merely summarising, in his own words, a series of conversations which he had with Bhagavan over a period of six weeks in 1930."[web 7] Narasimha's footnote: "The exact words [of the death experience] have not been recorded. The Swami as a rule talks quite impersonally. There is seldom any clear or pronounced reference to 'I' and 'you' in what he says. The genius of Tamil is specially suited for such impersonal utterances, and he generally talks Tamil. However, one studying his words and ways discovers personal references, mostly veiled. His actual words may be found too colourless and hazy to suit or appeal to many readers, especially of the western type. Hence the use here of the customary phraseology with its distinct personal reference."[18][web 8] For Narasimha Swami, Self Realization, see [1]

- ^ According to David Godman, yet another account is given by Ramana in Vichara Sangraham (Self-Enquiry):[web 8] "Therefore, leaving the corpse-like body as an actual corpse and remaining without even uttering the word 'I' by mouth, if one now keenly enquires, 'What is it that rises as "I"?’ then in the Heart a certain soundless sphurana, 'I-I', will shine forth of its own accord. It is an awareness that is single and undivided, the thoughts which are many and divided having disappeared. If one remains still without leaving it, even the sphurana – having completely annihilated the sense of the individuality, the form of the ego, 'I am the body' – will itself in the end subside, just like the flame that catches the camphor. This alone is said to be liberation by great ones and scriptures. (The Mountain Path, 1982, p. 98)." [web 8] The arguments for this conclusion are given by David Godman in [web 1]

- ^ David Godman gives his own account of Ramana's death-experience, based on Narasimha's notes of 8 January 1930 and 5 February 1930. See [web 7]

- ^ David Godman: "Bhagavan frequently used the Sanskrit phrase aham sphurana to indicate the 'I-I' consciousness or experience. Aham means 'I' and sphurana can be translated as 'radiation, emanation, or pulsation'."[web 1]

- ^ An extensive account on Ramana's use of the words "Self", "I-I" and "aham sphurana" is given in [web 1]

- ^ Rama P. Coomaraswamy: "[Krama-mukti is] to be distinguished from jîvan-mukti, the state of total and immediate liberation attained during this lifetime, and videha-mukti, the state of total liberation attained at the moment of death."[19] See [web 10] for more info on "gradual liberation".

- ^ Literally, "One who has poetry in his throat".

- ^ See The wanderling, Account of Frank Humphreys, First Western Disciple for quotes from these publications.

- ^ One of the aspects of Shiva is Pashupati, "Lord of all animals".[62]

- ^ "In actuality each of us is privy to his knowledge and blessing without any intermediary if we are open and receptive to the teachings. Each of us legitimately can claim lineage from Bhagavan although he himself was not part of any succession but stood alone, and in that sense of linear continuity he neither received nor gave initiation. But that is not the point, because though we each have the right to receive his grace, it is entirely different when it comes to assuming authority to disseminate the teachings. It is here we need to be very clear and separate the claims of wannabe gurus from the genuine devotees who are grateful recipients of grace."[web 20]

- ^ For example, H. W. L. Poonja[web 23]

- ^ "There have been many senior devotees of Bhagavan who, in their own right, had both the ability and authority to teach in his name. Muruganar, Sadhu Natanananda and Kunju Swami are some of those who immediately spring to mind. None of them to my knowledge ever claimed pre-eminence and the prerogative to teach. They knew two things. One, there would be many who would bow to their superior knowledge and set them up as an independent source, but secondly, they also knew that to abrogate for themselves the privilege would run contrary to Bhagavan’s mission or purpose."[web 20]

- ^ A sampradaya is a "tradition" or a "religious system".[69] It is a succession of masters and disciples and their teachings.

- ^ During a court case over the management of the ashram, Ramana declared himself an atiasrama,[web 24] beyond all caste and religious restrictions, not attached to anything in life.

- ^ Jung's foreword is famously quoted in "The Spiritual Teachings of Ramana Maharshi", but after having undergone editing, as saying: "He is genuine and, in addition to that, something quite phenomenal. In India, he is the whitest spot in a white space. What we find in the life and teachings of Sri Ramana is the purest of India."

- ^ Nevertheless, in India Ramana Maharshi is regarded as one of the outstanding religious figures of modern India, together with people like Ram Mohan Roy, the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, Dayananda Saraswati, the founder of the Arya Samaj, Ramakrishna, Vivekananda, Sri Aurobindo, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan.[73]

- ^ See [web 26] for an extensive analysis of the construction of Ramana Maharshi as "a timeless and purely spiritual figure".[web 25] See also Zen Narratives for a similar romantisation of Zen and its archetypal Rōshi.

- ^ Michaels uses Bourdieu's notion of habitus to point to the power of "culturally acquired lifestyles and attitudes, habits and predispositions, as well as conscious, deliberate acts or mythological, theological, or philosophical artifacts and mental productions"[76] in his understanding of Hinduism.

- ^ Shankara saw Arunchala as Mount Meru, which is in Indian mythology the axis of the world, and the abode of Brahman and the gods.[web 28]

- ^ And called his poodle "Atman".[91]

- ^ See also Ascended Master Teachings

- ^ The Theosophical Society had a major influence on Buddhist modernism[96] and Hindu reform movements[73], and the spread of those modernised versions in the west.[96] The Theosophical Society and the Arya Samaj were united from 1878 to 1882, as the Theosophical Society of the Arya Samaj.[97] Along with H. S. Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala, Blavatsky was instrumental in the Western transmission and revival of Theravada Buddhism.[98][99][100]

- ^ This reminds of the use of silence by the householder Vimalakirti in the Vimalakirti Sutra, a popular Buddhist sutra.

- ^ Ramana Maharshi: "(Aham, aham) ‘I-I’ is the Self; (Aham idam) “I am this” or “I am that” is the ego. Shining is there always. The ego is transitory; When the ‘I’ is kept up as ‘I’ alone it is the Self; when it flies at a tangent and says “this” it is the ego." [115] David Godman: "the expression 'nan-nan' ('I-I' in Tamil) would generally be taken to mean 'I am I' by a Tamilian. This interpretation would make 'I-I' an emphatic statement of Self-awareness akin to the biblical 'I am that I am' which Bhagavan occasionally said summarised the whole of Vedanta. Bhagavan himself has said that he used the term 'I-I' to denote the import of the word 'I'."[web 1]

- ^ "Self" refers to the Ātman.[11]

- ^ According to David Godman, the "I-I" is an intermediary realisation between the "I" (ego) and the Self: "[T]he verses on 'I-I' that Bhagavan wrote are open to two interpretations. They can be taken either to mean that the 'I-I' is experienced as a consequence of realisation or as a precursor to it. My own view, and I would stress that it is only a personal opinion, is that the evidence points to it being a precursor only.[web 31] Ramana Maharshi: "Liberation (mukti) is the total destruction of the I-impetus (aham-kara, of the "me"- and "my"-impetus (mama-kara)".[12]

- ^ "Nan Yar" by Sri Ramana as reproduced in Path of Sri Ramana, Part One, Fifth Edition. Page 149, :152.

- ^ Strictly speaking, "self-enquiry" is not the investigation of the "Self", "atman", but of the "I" or "heart", "aham" (Sanskrit), "nan" (Tamil).

- ^ According to Sadu Om, self-enquiry can also be seen as 'Self-attention' or 'Self-abiding'.[28]

- ^ "Hṛdayam" consists of two syllables 'hṛt' and 'ayam' which signify "I am the Heart".[web 32] The use of the word "hṛdayam" is not unique to Ramana Maharshi. A famous Buddhist use is the Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sutra, the Heart Sutra

- ^ The original book was first written in Tamil, and published by Sri Pillai.[32] The essay version of the book (Sri Ramana Nutrirattu) prepared by Ramana is considered definitive, as unlike the original it had the benefit of his revision and review. "Nan Yar" was documented by his disciple M. Sivaprakasam Pillai, who was already heavily influenced by traditional Advaita, and so had added notes about the traditional Advaitic negation method for his own clarification; these additional notes were later removed by Sri Ramana.[121] A careful translation with notes is available in English as 'The Path of Sri Ramana, Part One' by Sri Sadhu Om, one of the direct disciples of Ramana.[28]

- ^ See also.[web 36]

- ^ The authenticity of the "Vivekachudamani", a well-known work ascribed to Shankara, is doubtfull[134][135], though it is "so closely interwoven into the spiritual heritage of Shankara that any analysis of his perspective which fails to consider [this work] would be incomplete".[134]

- ^ Shankara himself was said to be a shaivite, or even a reincarnation of Shiva.[138]

- ^ Advaita Vedanta has become a broad current in Indian Culture[145][73], extending far beyond the Dashanami Sampradaya. It was popularised in the 20th century in both India and the west by Vivekananda[102][145], who emphasised anubhava ("personal experience"[104] over scriptural authority[104], Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan[145], and western orientalists who regarded Vedanta to be the "central theology of Hinduism".[145] Oriental scholarship portrayed Hinduism as a "single world religion"[145], and denigrated the heterogeneousity of Hindu beliefs and practices as 'distortions' of the basic teachings of Vedanta.[145] The same tendency to prefer an essential core teaching has been prevalent in western scholarship of Theravada Buddhism[146], and has also been constructed by D.T. Suzuki in his presentation of Zen-Buddhism to the west.[96][147]

- ^ David Gordon White notes: "Many Western indologists and historians of religion specializing in Hinduism never leave the unalterable worlds of the scriptures they interpret to investigate the changing real-world contexts out of which those texts emerged". He argues for "an increased emphasis on non-scriptural sources and a focus on regional traditions".[148]

- ^ A Christian reference.See [web 37] and.[web 1] Ramana was taught at Christian schools.[150]

- ^ The traditional Advaitic (non-dualistic) school advocates "elimination of all that is non-self (the five sheaths) until only the Self remains".[152] The five kosas, or sheaths, that hide the true Self are: Material, Vital, Mental, Knowledge, and Blissful.

- ^ See Sri Muruganar for more information on Muruganar

- ^ See Sadhu Om for more information on Sadhu Om

- ^ David Godman: "Because some of the interpreters were not completely fluent in English some of the transcriptions were either ungrammatical or written in a kind of stilted English which occasionally makes Sri Ramana sound like a pompous Victorian."[web 2]

References

- ^ Godman 994.

- ^ Editor unknown 1988.

- ^ a b c d e Godman 1985. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGodman1985 (help)

- ^ a b c Zimmer 1948, p. 23.

- ^ Zimmer 1948, p. 37-38.

- ^ a b Godman 1985, p. 4. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGodman1985 (help)

- ^ a b c d Ebert 2006. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)

- ^ a b Godman 1985, p. 5. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGodman1985 (help)

- ^ Lucas 2011.

- ^ Godman 1985, p. 29-30. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFGodman1985 (help)

- ^ a b c Ebert 2006, p. 202-213. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)

- ^ a b c Zimmer 1948, p. 195.

- ^ Bhagavadpada 2008.

- ^ a b c Osborne & Year unknown.

- ^ a b c Krishna Bikshu & Year unknown.

- ^ a b Natarajan 2006. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFNatarajan2006 (help)

- ^ Zimmer 1948, p. 18.

- ^ Narasimha 2003, p. 20, footnote.

- ^ Coomaraswamy 2004.

- ^ Ebert 2006, p. 29. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)

- ^ Zimmer 1948, p. 25.

- ^ a b Sri Ramanasramam 1981.

- ^ Ebert 2006, p. 47. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)

- ^ Ebert 2006, p. 52. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)

- ^ ebert 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Ebert 2006, p. 50. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFEbert2006 (help)