Phoenix

Phoenix | |

|---|---|

| City of Phoenix | |

Images, from top, left to right: Papago Park at sunset, Saint Mary's Basilica, downtown Phoenix, Phoenix skyline at night, Arizona Science Center, Rosson House, Phoenix light rail, a saguaro cactus, McDowell Mountains | |

|

| |

| Nickname(s): "Valley of the Sun", "The Valley" | |

Location in Maricopa County and the state of Arizona | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | |

| Incorporated | February 5, 1881 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Body | Phoenix City Council |

| • Mayor | Greg Stanton (D) |

| Area | |

| • City | 517.948 sq mi (1,338.26 km2) |

| • Land | 516.704 sq mi (1,338.26 km2) |

| • Water | 1.244 sq mi (3.22 km2) |

| • Metro | 16,573 sq mi (42,920 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,086 ft (331 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 1,445,632 |

| • Estimate (2013[3]) | 1,513,367 (US: 6th) |

| • Density | 2,797.8/sq mi (1,080.2/km2) |

| • Urban | 3,629,114 (US: 12th) |

| • Metro | 4,398,762 (US: 12th) |

| • Demonym | Phoenician |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (no DST/PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 85001–85099 |

| Area code(s) | 480, 602, 623 |

| FIPS code | 04-55000 |

| GNIS ID(s) | 44784, 2411414 |

| Major airport | Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport – PHX (Major/International) |

| Website | www |

Phoenix (/ˈfiːnɪks/; O'odham: S-ki:kigk; Yavapai: Wathinka or Wakatehe; Western Apache: Fiinigis; Template:Lang-nv; Mojave: Hachpa 'Anya Nyava)[4] is the capital, and largest city, of the State of Arizona. With 1,445,632 people (as of the 2010 U.S. Census), Phoenix is the most populous state capital in the United States, as well as the sixth most populous city nationally, after (in order) New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Philadelphia.[5]

The anchor of the Phoenix metropolitan area (also known as the Valley of the Sun, a part of the Salt River Valley), it is the 13th largest metro area by population in the United States with approximately 4.3 million people in 2010.[6][7] In addition, Phoenix is the county seat of Maricopa County and is one of the largest cities in the United States by land area.[8]

Settled in 1867 as an agricultural community near the confluence of the Salt and Gila Rivers, Phoenix incorporated as a city in 1881.[9] Located in the northeastern reaches of the Sonoran Desert, Phoenix has a subtropical desert climate. Despite this, its canal system led to a thriving farming community, many of the original crops remaining important parts of the Phoenix economy for decades, such as alfalfa, cotton, citrus and hay (which was important for the cattle industry).[10][11] In fact, the "Five C's" (Cotton, Cattle, Citrus, Climate, and Copper), remained the driving forces of Phoenix's economy until after World War II, when high tech industries began to move into the valley.[12][13]

The population growth rate of the Phoenix metro area has been nearly 4% per year for the past 40 years. While that growth rate slowed during the Great Recession, it has already begun to rebound. Currently ranked 6th in population, it is predicted that Phoenix will rank 4th by 2020.[14] Being near the center of the state, Phoenix is the jumping off point for the various attractions in the Valley of the Sun, as well as the rest of Arizona.

History

Early history

For more than 2,000 years, the Hohokam peoples occupied the land that would become Phoenix.[9][15] The Hohokam created roughly 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable. Paths of these canals would later become used for the modern Arizona Canal, Central Arizona Project Canal, and the Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct. The Hohokam also carried out extensive trade with the nearby Anasazi, Mogollon and Sinagua, as well as with the more distant Mesoamerican civilizations.[16] It is believed that between 1300 and 1450, periods of drought and severe floods led to the Hohokam civilization's abandonment of the area.[17] Local Akimel O'odham settlements, thought to be the descendants of the formerly urbanized Hohokam, concentrated on the Gila River.[18][19]

When the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, Mexico sold its northern zone passed to the United States and residents became U.S. citizens. The Phoenix area became part of the New Mexico Territory.[20] In 1863 the mining town of Wickenburg was the first to be established in what is now Maricopa County, to the north-west of modern Phoenix. At the time Maricopa County had not yet been incorporated: the land was within Yavapai County, which included the major town of Prescott to the north of Wickenburg.

The U.S. Army created Fort McDowell on the Verde River in 1865 to forestall Native American uprisings.[21] The fort established a camp on the south side of the Salt River by 1866, which was the first non-native settlement in the valley after the decline of the Hohokam. In later years, other nearby settlements would form and merge to become the city of Tempe,[22] but this community was incorporated after Phoenix.

Founding and incorporation

The history of the city of Phoenix begins with Jack Swilling, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War. In 1867 he saw in the Salt River Valley a potential for farming, much like that already cultivated by the military further east, near Fort McDowell. He formed a small community that same year about 4 miles (6 km) east of the present city. Lord Darrell Duppa suggested the name "Phoenix", as it described a city born from the ruins of a former civilization.[9][23]

The Board of Supervisors in Yavapai County, which at the time encompassed Phoenix, officially recognized the new town on May 4, 1868, and the first post office was established the following month, with Swilling as the postmaster.[9] On February 12, 1871, the territorial legislature created Maricopa County, the sixth one formed in the Arizona Territory, by dividing Yavapai County. The first election for county office was held in 1871, when Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff, actually running unopposed when the other two candidates, John A. Chenowth and Jim Favorite, fought a duel wherein Chenowth killed Favorite, and then was forced to withdraw from the race.[9]

The town grew during the 1870s, and President Ulysses S. Grant issued a land patent for the present site of Phoenix on April 10, 1874. By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government needed an overhaul, so that year an election was held in which three village trustees as well as several other officials were selected.[9] By 1880, the town's population stood at 2,453.[23]

By 1881, Phoenix' continued growth made the existing village structure with a board of trustees obsolete. The Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill", incorporating Phoenix and providing for a mayor-council government, and became official on February 25, 1881 when it was signed by Governor John C. Fremont, officially incorporating Phoenix as a city with an approximate population of 2,500.[9]

The coming of the railroad in the 1880s was the first of several important events that revolutionized the economy of Phoenix. Phoenix became a trade center, with its products reaching eastern and western markets. In response, the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce was organized on November 4, 1888.[24] Earlier in 1888 the city offices were moved into the new City Hall, at Washington and Central.[9] When the territorial capital was moved from Prescott to Phoenix in 1889 the temporary territorial offices were also located in City Hall.[23] With the arrival of the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad in 1895, Phoenix was connected to the Prescott, Flagstaff and other northern state communities. The increased access to commerce, expedited the city's economic rise. The year 1895 also saw the establishment of Phoenix Union High School, with an enrollment of 90.[9]

1900 to World War II

The former city flag of Phoenix, adopted in November 1921.

The former city flag of Phoenix, adopted in November 1921.On February 25, 1901, Governor Murphy dedicated the permanent state Capitol building,[9] and the Carnegie Free Library opened seven years later, on Feb.18, 1908, dedicated by Benjamin Fowler.[23] The National Reclamation Act was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, which allowed for dams to be built on waterways in the west for reclamation purposes.[25] The first dam constructed under the act, the Theodore Roosevelt Dam was begun in 1906. It supplied both water and electricity, becoming the first multiple-purpose dam, and Roosevelt would attend the official dedication himself, on May 18, 1911. At the time, it was the largest masonry dam in the world, forming several new lakes in the surrounding mountain ranges.[26]

On February 14, 1912, under President William Howard Taft, Phoenix became the capital of the newly formed state of Arizona.[26] This occurred just six months after Taft had vetoed in August 1911, a joint congressional resolution granting statehood to Arizona, due to his disagreement of the state constitution's position regarding the recall of judges.[25] In 1913 Phoenix adopted a new form of government, changing from a mayor-council system to council-manager, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate, and by the end of its first eight years under statehood, Phoenix' population had grown to 29,053. In 1920 Phoenix would see its first skyscraper, the Heard Building.[9] In 1929 Sky Harbor was officially opened, at the time owned by Scenic Airways. It would later be purchased by the city in 1935, who operates it to this day.[27]

On March 4, 1930, former U.S. President Calvin Coolidge dedicated a dam on the Gila River named in his honor. However, the state had just been through a long drought, and the reservoir which was supposed to be behind the dam, was virtually dry. The humorist Will Rogers, who was also on hand as a guest speaker joked, "If that was my lake I'd mow it."[25] Phoenix's population had more than doubled during the 1920s, and now stood at 48,118.[9]

During World War II, Phoenix's economy shifted to that of a distribution center, rapidly turning into an embryonic industrial city with mass production of military supplies. There were 3 air force fields in the area: Luke Field, Williams Field, and Falcon Field, as well as two large pilot training camps, Thunderbird Field No. 1 in Glendale and Thunderbird Field No. 2 in Scottsdale.[9][28][29]

Postwar explosive growth

A town that had just over sixty-five thousand residents in 1940 became America’s sixth largest city by 2010, with a population of nearly 1.5 million, and millions more in nearby suburbs. Shermer argues that after the war Phoenix boosters led by Barry Goldwater and other ambitious young businessmen and politicians, often with an Eastern education, created a neoliberal pro-business climate. They attracted Eastern industry by rejecting the New Deal formula of strong labor unions and tight regulation of industry. They told prospects that Phoenix had excellent weather, cheap land, good transportation, low-wage rates, a right-to-work law that weakened unions, minimal regulations, easy access to the West Coast markets, and an eagerness to grow. They pointed out it was highly attractive place for young couples to raise their families. Hundreds of manufacturing firms were attracted to Phoenix, especially those that emphasized high technology, along with, corporate headquarters. Shermer argues that the Phoenix plan was widely admired by other ambitious cities in the South and Southwest, and became part of national conservatism as exemplified by Goldwater and his supporters. The Phoenix plan was not built on libertarian low-government ideals, Rather, Shermer argues, it involved active government intervention in the economy to promote rapid growth. For example the state played the central role in giving Phoenix a guaranteed water supply, as well as good universities.[30]

When the war ended, many of the men who had undergone their training in Arizona returned bringing their new families. Large industry, learning of this labor pool, started to move branches here.[13] In 1948 high-tech industry, which would become a staple of the state's economy, arrived in Phoenix when Motorola chose Phoenix for the site of its new research and development center for military electronics. Seeing the same advantages as Motorola, other high-tech companies such as Intel and McDonnell Douglas would also move into the valley and open manufacturing operations.[13]

By 1950, over 105,000 people lived within the city and thousands more in surrounding communities.[9] The 1950s growth was spurred on by advances in air conditioning, which allowed both homes and businesses to offset the extreme heat known to Phoenix during its long summers. There was more new construction in Phoenix in 1959 alone, than it in the prior thirty years between 1914 and 1946.[13][31]

The 1960s through current

Over the next several decades, the city and metropolitan area attracted more growth and became a favored tourist destination for its exotic desert setting and recreational opportunities. In 1960 the Phoenix Corporate Center opened; at the time it was the tallest building in Arizona, topping off at 341 feet.[32] The 1960s saw many other buildings constructed as the city expanded rapidly, including: the Rozenweig Center (1964), today called Phoenix City Square,[33] the landmark Phoenix Financial Center (1964),[34] as well as many of Phoenix's residential high-rises. In 1965 the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum was opened on the grounds of the Arizona State Fair, west of downtown, and in 1968, the city was surprisingly awarded the Phoenix Suns NBA franchise,[35][36] which played its home games at the Coliseum until 1992.[37] In 1968, the Central Arizona Project was approved by President Lyndon B. Johnson, assuring future water supplies for Phoenix, Tucson, and the agricultural corridor in between.[38] The following year, Pope Paul VI created the Diocese of Phoenix on December 2, by splitting the Archdiocese of Tucson, with Edward A. McCarthy as the first Bishop.[39]

In the 1970s the downtown area experienced a resurgence, with a level of construction activity not seen again until the urban real estate boom of the 2000s. By the end of the decade, Phoenix adopted the Phoenix Concept 2000 plan which split the city into urban villages, each with its own village core where greater height and density was permitted, further shaping the free-market development culture. Originally, there were 9 villages,[40] but this has been expanded to 15 over the years (see Cityscape below). This officially turned Phoenix into a city of many nodes, which would later be connected by freeways. 1972 would see the opening of the Phoenix Symphony Hall,[41] Other major structures which saw construction downtown during this decade were the Wells Fargo Plaza, the Chase Tower (the tallest building in both Phoenix and Arizona)[42] and the U.S.Bank Center.

Nominated by President Reagan, on September 25, 1981 Phoenix resident Sandra Day O'Connor broke the gender barrier on the U.S. Supreme Court, when she was sworn in as the first female judge.[43] 1985 saw the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, the nation's largest nuclear power plant, begin electrical production.[44] 1987 was marked by visits by both Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa.[45]

There was an influx of refuges due to low-cost housing in the Sunnyslope area in the 1990s, resulting in 43 different languages being spoken in local schools by the year 2000.[46] The new 20 story City Hall opened in 1992,[47] and 1993 saw the creation of "Tent City," by Sheriff Joe Arpaio, using inmate labor, to alleviate overcrowding in the Maricopa County Jail system, the fourth-largest in the world.[48] The famous "Phoenix Lights" UFO sightings took place in March 1997.

Phoenix has maintained a growth streak in recent years, growing by 24.2% before 2007. This made it the second-fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States surpassed only by Las Vegas.[49] In 2008 Squaw Peak, the second tallest mountain in the city, was renamed Piestewa Peak after Army Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, an Arizonan and the first Native American woman to die in combat, as well as being the first American female casualty of the 2003 Iraq War.[50] 2008 also saw Phoenix as one of the cities hardest hit by the subprime mortgage crisis, and by early 2009, the median home price was $150,000, down from its $262,000 peak in 2007.[51] Crime rates in Phoenix have gone down in recent years and once troubled, decaying neighborhoods such as South Mountain, Alhambra, and Maryvale have recovered and stabilized. Recently downtown Phoenix and the central core have experienced renewed interest and growth, resulting in numerous restaurants, stores and businesses opening or relocating to central Phoenix.[52]

Geography

Phoenix is in the southwestern United States, in the south-central portion of Arizona, and about halfway between Tucson to the south and Flagstaff to the north. The metropolitan area is known as the "Valley of the Sun", due to its location in the Salt River Valley. It lies at a mean elevation of 1,117 feet (340 m), in the northern reaches of the Sonoran Desert.[53][54]

Other than the mountains in and around the city, the topography of Phoenix is generally flat, allowing the city's main streets to run on a precise grid with wide, open-spaced roadways. Scattered, low mountain ranges surround the valley: McDowell Mountains to the northeast, the White Tank Mountains to the west, the Superstition Mountains far to the east, and the Sierra Estrella to the southwest. On the outskirts of Phoenix are large fields of irrigated cropland and several Indian reservations.[24][53][55] The Salt River runs westward through the city of Phoenix, and the riverbed is often dry or contains a little water due to large irrigation diversions. The community of Ahwatukee is separated from the rest of the city by South Mountain.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 517.9 square miles (1,341 km2); 516.7 square miles (1,338 km2) of it is land and 1.2 square miles (0.6 km², or 0.2%) of it is water. Even though it is the 6th most populated city, the large area gives it a low density rate of approximately 2,797 people per square mile.[56] In comparison, Philadelphia, the 5th most populous city has a density of over 11,000.[57]

As with most of Arizona, Phoenix does not observe daylight saving time. In 1973, Gov. Jack Williams argued to the U.S. Congress that due to air conditioning units not being used as often in the morning on standard time, energy use would increase in the evening. He went on to say that energy use would rise "because there would be more lights on in the early morning." He was also concerned about children going to school in the dark, which was quite accurate.[58]

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

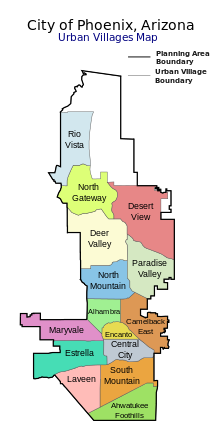

Since 1979, the City of Phoenix has been divided into urban villages, many of which are based upon historically significant neighborhoods and communities that have since been annexed into Phoenix.[59][60] Each village has a planning committee that is appointed directly by the city council. According to the village planning handbook issued by the city, the purpose of the village planning committees is to work with the city's planning commission to ensure a balance of housing and employment in each village, concentrate development at identified village cores, and to promote the unique character and identity of the villages.[61]

The 15 urban villages are:

- Ahwatukee Foothills

- Alhambra

- Camelback East

- Central City

- Deer Valley

- Desert View

- Encanto

- Estrella

- Laveen

- Maryvale

- North Gateway

- North Mountain

- Paradise Valley

- Rio Vista

- South Mountain

In addition to the above urban villages, Phoenix has a variety of commonly referred-to regions and districts, such as Downtown, Midtown, West Phoenix, North Phoenix, South Phoenix, Biltmore, Arcadia, and Sunnyslope.

Climate

Phoenix has a subtropical desert climate (Köppen: BWh), typical of the Sonoran Desert in which it lies. Phoenix has extremely hot summers and warm winters. The average summer high temperatures are some of the hottest of any major city in the United States, and approach those of cities such as Riyadh and Baghdad.[62] On average (1981–2010), there are 107 days annually with a high of at least 100 °F (38 °C),[63] including most days from late May through early October. Highs top 110 °F (43 °C) an average of 18 days during the year[64] Every day from June 10 through August 24, 1993, the temperature in Phoenix reached 100 °F or more, the longest continuous number of days (76) in the city's history. Officially, the number of days with a high of at least 100 °F has historically ranged from 143 in 1989 to 48 in 1913. For comparison, since 1870, New York City has seen a temperature of 100 degrees or more a total of only 59 days.[65] On June 26, 1990, the temperature reached an all-time recorded high of 122 °F (50 °C).[66]

Most deserts undergo drastic fluctuations between day and nighttime temperatures, but not Phoenix due to the urban heat island effect. As the city has expanded, average summer low temps have been rising steadily. The daily heat of the sun is stored in pavement, sidewalks and buildings, and is radiated back out at night.[67] During the summer, overnight lows greater than 80 °F (27 °C) are commonplace, as the daily normal low remains at or above 80 °F from June 22 to September 8. On average, 67 days throughout the year will see the nighttime low at or above 80 °F (27 °C). July 15, 2003 officially saw the record high daily minimum temperature, at 96 °F (36 °C).[62][63]

The city averages over 330 days of sunshine, or over 90%, per year, and receives scant rainfall, the average annual total at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport being 7 inches (180 mm).[68] Precipitation is sparse during most of the year, but the monsoon season brings an influx of moisture. The monsoon season officially started when the average Dew point was 55 degrees for three days in a row; however, in 2008 the National Weather Service decreed that from that point forward, June 15 would be the official first day of the monsoon, and it would end on September 30.[69] The monsoon raises humidity levels and can cause heavy localized precipitation, occasional flooding, large hail, strong winds, the rare tornado, and dust storms,[70] which can rise to the level of a haboob in some years.[71] July is the wettest month of the year (1.05 inches (27 mm)), while June is the driest (.02 inches (0.51 mm)).

On average, Phoenix has only one day per year where the temperature drops to or below freezing.[63] However, the frequency of freezes increases the further one moves outward from the urban heat island. Frequently, outlying areas of Phoenix see frost. Officially, the earliest freeze on record occurred on November 4, 1956, and the latest occurred on March 31, 1987.[a] The all-time lowest recorded temperature in Phoenix was 16 °F (−9 °C) on January 7, 1913, while the coldest daily maximum was 36 °F (2 °C) on December 10, 1898. The longest continuous stretch without a day of frost in Phoenix was over 5 years, from November 23, 1979 to January 31, 1985.[72][73] Snow is a very rare occurrence for the city of Phoenix. Snowfall was first officially recorded in 1898, and since then, accumulations of 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) or greater have occurred only eight times. The heaviest snowstorm on record dates to January 21–22, 1937, when 1 to 4 inches (2.5 to 10.2 cm) fell in parts of the city and did not melt entirely for three days. Before that, 1 inch (2.5 cm) had fallen on January 20, 1933. On February 2, 1939, 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) fell. Snow also fell on March 12, 1917 and on November 28, 1919. The most recent snow of significance fell on, December 6, 1998 across the northwest portions of the valley that are below 2,000 feet. During the 1998 event, Sky Harbor reported a dusting of snow. The last measurable snowfall was recorded when 0.1 inches (0.25 cm) fell in central Phoenix on December 11, 1985.[74] On December 30, 2010 and February 20, 2013, graupel fell, although it was widely believed to be snow.[75][76]

| Climate data for Phoenix Int'l, Arizona (1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1895–present)[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

92 (33) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

114 (46) |

122 (50) |

121 (49) |

118 (48) |

118 (48) |

113 (45) |

99 (37) |

87 (31) |

122 (50) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.2 (25.7) |

82.1 (27.8) |

90.4 (32.4) |

99.0 (37.2) |

105.7 (40.9) |

112.7 (44.8) |

114.6 (45.9) |

113.2 (45.1) |

108.9 (42.7) |

100.7 (38.2) |

88.9 (31.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

115.7 (46.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67.6 (19.8) |

70.8 (21.6) |

78.1 (25.6) |

85.5 (29.7) |

94.5 (34.7) |

104.2 (40.1) |

106.5 (41.4) |

105.1 (40.6) |

100.4 (38.0) |

89.2 (31.8) |

76.5 (24.7) |

66.2 (19.0) |

87.1 (30.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

59.9 (15.5) |

66.3 (19.1) |

73.2 (22.9) |

82.0 (27.8) |

91.4 (33.0) |

95.5 (35.3) |

94.4 (34.7) |

89.2 (31.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

65.1 (18.4) |

55.8 (13.2) |

75.6 (24.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 46.0 (7.8) |

49.0 (9.4) |

54.5 (12.5) |

60.8 (16.0) |

69.5 (20.8) |

78.6 (25.9) |

84.5 (29.2) |

83.6 (28.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

65.6 (18.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 36.0 (2.2) |

40.0 (4.4) |

44.4 (6.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

58.4 (14.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

74.2 (23.4) |

68.3 (20.2) |

53.8 (12.1) |

42.0 (5.6) |

35.4 (1.9) |

33.8 (1.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 16 (−9) |

24 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

63 (17) |

58 (14) |

47 (8) |

34 (1) |

27 (−3) |

22 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.87 (22) |

0.87 (22) |

0.83 (21) |

0.22 (5.6) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.91 (23) |

0.93 (24) |

0.57 (14) |

0.56 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

0.74 (19) |

7.22 (183) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 33.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50.9 | 44.4 | 39.3 | 27.8 | 21.9 | 19.4 | 31.6 | 36.2 | 35.6 | 36.9 | 43.8 | 51.8 | 36.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

32.2 (0.1) |

32.9 (0.5) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

58.3 (14.6) |

52.3 (11.3) |

43.0 (6.1) |

35.8 (2.1) |

33.1 (0.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 256.0 | 257.2 | 318.4 | 353.6 | 401.0 | 407.8 | 378.5 | 360.8 | 328.6 | 308.9 | 256.0 | 244.8 | 3,871.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 81 | 84 | 86 | 90 | 93 | 95 | 86 | 87 | 89 | 88 | 82 | 79 | 87 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3.1 | 4.4 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA (dew points, relative humidity, and sun 1961–1990)[77][78][79], Weather.com[80] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[81] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna

Unusual species are occasionally found within Phoenix boundaries and surrounding areas of Arizona. Native species include desert tortoises, gila monsters, roadrunners, coyotes, chuckwallas (large lizards), javelina (wild pigs), bobcats, jaguars, and mountain lions. There are many species of falcons, hawks, golden and bald eagles, and the state bird, the cactus wren.[82][83][84] Phoenix is also home to a plethora of snakes, such as the western diamondback rattlesnake, sonoran sidewinder, several other types of rattlesnakes, sonoran coralsnake, and dozens of other non-venomous snakes, including the California kingsnake.[85]

The Arizona Upland subdivision of the Sonoran Desert (of which Phoenix is a part) has the most structurally diverse vegetation in the United States. It includes one of the most famous species of succulents, the giant saguaro cactus. Other important species are organpipe, ocotillo, barrel, prickly pear and cholla cacti, Palo Verde trees, various types of palm trees, agaves, foothill and blue paloverde, ironwood, mesquite and creosote bush.[86][87]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 240 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,708 | 611.7% | |

| 1890 | 3,152 | 84.5% | |

| 1900 | 5,544 | 75.9% | |

| 1910 | 11,314 | 104.1% | |

| 1920 | 29,053 | 156.8% | |

| 1930 | 48,118 | 65.6% | |

| 1940 | 65,414 | 35.9% | |

| 1950 | 106,818 | 63.3% | |

| 1960 | 439,170 | 311.1% | |

| 1970 | 581,572 | 32.4% | |

| 1980 | 789,704 | 35.8% | |

| 1990 | 983,403 | 24.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,321,045 | 34.3% | |

| 2010 | 1,445,632 | 9.4% | |

| 2013 (est.) | 1,513,367 | [88] | 4.7% |

| Sources:[88][89][3] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[90] | 1990[91] | 1970[91] | 1940[91] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (includes White Hispanics) | 65.9% | 81.7% | 93.3% | 92.3% |

| Black or African American | 6.5% | 5.2% | 4.8% | 6.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 40.8% | 20.0% | 12.7%[92] | n/a |

| Asian | 3.2% | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.8% |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 46.5% | 71.8% | 81.3%[92] | n/a |

Phoenix is the sixth most populous city in the United States according to the 2010 United States Census, with a population of 1,445,632, making it the most populous state capital in the United States.[48] Phoenix's ranking as the sixth most populous city was a drop from the number five position it had held since the U. S. Census Bureau released population estimates on June 28, 2007. Those statistics used data from 2006, which showed Phoenix's population at 1,512,986, which put it just ahead of Philadelphia.[48] The 2010 Census, while showing an overall increase from the official 2000 Census showed a drop in Phoenix' population from the 2007 estimates, allowing Philadelphia to regain the fifth spot.[48]

After leading the nation in population growth for over a decade, the sub-prime mortgage crisis, followed by the recession, led to a slowing in the growth of Phoenix. There were approximately 77,000 people added to the population of the Phoenix metropolitan area in 2009, which was down significantly from its peak in 2006 of 162,000.[93][94] Despite this slowing, Phoenix's population grew by 9.4% since the 2000 census (a total of 124,000 people), while the entire Phoenix metropolitan area grew by 28.9% during the same period. This compares with an overall growth rate nationally during the same time frame of 9.7%.[95][96] Not since 1940-50, when the city had a population of 107,000, had the city gained less than 124,000 in a decade. And when you look at the growth as a percentage of the population, you have to go all the way back to the 1880-90 census period to find a lower growth rate than the 9.4% Phoenix experienced during the last decade.[97]

The Phoenix Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) (officially known as the Phoenix-Mesa-Glendale MSA), is one of 10 MSA's in Arizona, and is the 14th largest in the United States, with a total population of 4,192,887 as of the 2010 Census. Consisting of parts of both Pinal and Maricopa counties, the MSA accounts for 65.5% of the total population of the state of Arizona.[95][96] Phoenix only contributed 13% to the total growth rate of the MSA, down significantly from its 33% share during the prior decade.[98] Phoenix is also part of the Arizona Sun Corridor megaregion (MR), which is the 10th most populous of the 11 MRs, and the 8th largest by area. It had the 2nd largest growth by percentage of the MRs (behind only the Gulf Coast MR) between 2000 and 2010.[99]

The population is almost equally split between men and women, with men making up 50.2% of city's citizens. The population density is 2,797.8 people per square mile, and the median age of the city is 32.2 years, with only 10.9 of the population being over 62. 98.5% of Phoenix's population lives in households with an average household size of 2.77 people. There were 514,806 total households, with 64.2% of those households consisting of families: 42.3% married couples, 7% with an unmarried male as head of household, and 14.9% with an unmarried female as head of household. 33.6% of those households have children below the age of 18. Of the 35.8% of non-family households, 27.1% of them have a householder living alone, almost evenly split between men and women, with women having 13.7% and men occupying 13.5%. Phoenix has 590,149 housing units, with an occupancy rate of 87.2%. The largest segment of vacancies is in the rental market, where the vacancy rate is 14.9%, and 51% of all vacancies are in rentals. Vacant houses for sale only make up 17.7% of the vacancies, with the rest being split among vacation properties and other various reasons.[100]

The median income for a household in the city was $47,866, and the median income for a family was $54,804. Males had a median income of $32,820 versus $27,466 for females. The per capita income for the city was $24,110. 21.8% of the population and 17.1% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total population, 31.4% of those under the age of 18 and 10.5% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[101]

According to the 2010 Census, the racial breakdown of Phoenix is as follows:[102]

- White: 65.9% (46.5% non-Hispanic)

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 40.8% (35.9% Mexican, 0.6% Puerto Rican 0.5% Guatemalan, 0.3% Salvadoran, 0.3% Cuban)

- Black or African American: 6.5% (6.0% non-Hispanic)

- Native American: 2.6%

- Asian: 3.2% (0.8% Indian, 0.5% Filipino, 0.5% Korean, 0.4% Chinese, 0.4% Vietnamese, 0.2% Japanese, 0.2% Thai, 0.1% Burmese)

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%

- Other race: 0.1%

- Two or more races: 1.7%

Phoenix's population has historically been predominantly white. Since 1890, up until 1970, over 90% of the citizens were white, although in recent years, this percentage has dropped; first to 85% in 1980, than to 81% in 1990. In 2010, it had dipped to 65%. However, a significant portion of this decrease can be attributed to new guidelines put out by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1980, when a question regarding Hispanic origin was added to the census questionnaire. This has led to an increasing tendency for some groups to no longer self-identify as white, and instead categorize themselves as "other races".[91] 20.6% of the population of the city was foreign born in 2010. Of the 1,342,803 residents over 5 years of age, 63.5% speak only English, 30.6% speak Spanish as their primary language, 2.5% speak another Indo-European language, 2.1% speak Asian or Islander languages, with the remaining 1.4% speaking other languages. 15.7% of non-English speakers speak English less than "very well". The ancestral breakdown has the top 10 ancestries as: Mexican (35.9%), German (15.3%), Irish (10.3%), English (9.4%), Black (6.5%), Italian (4.5%), French (2.7%), Polish (2.5%), American Indian (2.2%), and Scottish (2.0%).[103]

In 2010, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives, which conducts religious census each ten years, 39% of those polled in Maricopa county considered themselves a member of a religious group, down from 40% in 2000. Of those who expressed a religion, the area's religious composition was reported as 35% Catholic, 22% to Evangelical Protestant denominations, 16% Latter-Day Saints (LDS), 14% to nondenominational congregations, 7% to Mainline Protestant denominations, and 2% Hindu. The remaining 4% belong to other religions, such as Buddhism, and Judaism. While there was an overall increase in the number of religious adherents over the decade of 103,000, that did not keep pace with the overall population increase in the country during the same period, which increased by almost three-quarters of million individuals, resulting in the percentage drop. The largest aggregate increases were in the LDS (a 58% increase) and Evangelical Protestant churches (14% increase), while all other categories actually saw their numbers drop slightly, or remain static. Overall, the Catholic Church had an 8% drop, while Mainline Protestant groups saw a 28% decline.[104]

Economy

The early economy of Phoenix was focused primarily on agriculture and natural resources, dependent mainly on the "5Cs" which were copper, cattle, climate, cotton and citrus.[12] Once the Salt River Project was completed, the city, and the valley in general, began to develop more rapidly, due to a now fairly reliable source of water. Led by agriculture, the number one crop in the 1910s was alfalfa, followed by citrus, cotton and other crops, with almost a quarter-million acres under cultivation by the middle of the decade. World War I would greatly change the agricultural landscape of the valley, and teach the farmers of the region an invaluable, if difficult lesson.[105][106]

As the war began, imports of foreign cotton were no longer available to American manufacturing, since cotton was a major material used in the production of tires and airplane fabric, those manufacturers began to look for new sources. The Salt River Valley looked to be an ideal location for expansion of the cotton crop. Led by Goodyear, tire and airplane manufacturers began to buy more and more cotton from valley growers. In fact, the town of Goodyear was founded during this period when the company purchased desert acreage southwest of Phoenix to grow cotton. By 1918, cotton had replaced alfalfa as the number one industry in Phoenix. As the price of cotton rose, more and more of Phoenix acreage was devoted to the crop, however, in 1920, when cotton accounted for three-quarters of the cultivated acreage in the valley, the bottom fell out of the cotton market due to the dual reasons of lower demand due to the end of the war production machine and foreign growers now once again having access to the American market, resulting in their shipping large amounts of cotton to the U.S. This led to a diversification of crops in the valley from that point forward.[107][106]

Cattle, and the meat industry was also a vital part of the economy. The cotton bust led to more production of alfalfa, wheat and barley, as well as citrus. The grain production in turn led to an increase in the cattle ranching industry. By the end of the Roaring Twenties, Phoenix boasted the largest meat processing plant between Dallas and Los Angeles.[108][109] While that plant, and its attendant stockyards are long gone, a remnant remains in the famous Stockyards Restaurant. The prosperity following the local depression caused by the cotton bust enabled other industries to grow as well. The city's first skyscraper, the 7-story Heard Building was built in 1920, followed by the 10-story Luhrs Building following the bust in 1924, and the Westward Ho, a 16-story hotel was constructed in 1928.[110]

With the establishment of a main rail line in 1926 (the Southern Pacific), the opening of the Union Station in 1923, and the creation of Sky Harbor airport by the end of the decade, it allowed greater ease of access to the city.[111] The construction of the Westward Ho was part of a concerted effort on the part of both civic and business organizations in Phoenix to develop Phoenix as a tourist destination. Phoenix already had two highly rated resorts, the Ingleside Inn and the Jokake Inn, and after the Westward Ho, the Arizona Biltmore, designed by one of Frank Lloyd Wright's students, was constructed in 1929.[112] Other major hotels were built during this era, such as the San Carlos (also in 1928), which led older hotels, like the Hotel Adams to refurbish themselves in order to remain competitive.[112] By the end of the decade, the tourism industry topped $10 million for the first time in the city's history.[113] Tourism remains one of the top ten economic drivers of the city to this day.[114]

The Great Depression affected Phoenix, just as it did every other location in the country, but the effects were not as deep, nor lasted as long. Phoenix had a very diverse economy, and was not heavily vested in the manufacturing sector.[115] While the stock market crash did not affect the city very directly, the suppression of the national economy did. Revenue from all major industries in the valley decreased drastically: copper mining dropped from $155 million in 1929 to $15 million by 1932; agriculture and livestock also saw reductions during that same period, although not as drastic, from $42 million to $14 million and $25.5 million to $15 million, respectively. Compared to the rest of the country, and even the rest of the state, Phoenix was not as badly affected by bankruptcies, foreclosures, or unemployment, and by 1934, the recovery was underway.[116]

At the conclusion of World War II, the valley's economy began to further grow and expand. After the war, the city's population began to surge as many men who had undergone their military training at the various bases in and around Phoenix, returned with their families. In 1948, Motorola chose Phoenix for the site of its new research and development center for military electronics. They were followed in time, by other high-tech companies such as Intel and McDonnell Douglas.[13]

The construction industry, spurred on by the city's growth, further expanded with the development of Sun City. Much like Levittown, New York became the template for suburban development in post-WWII America,[117] Sun City, just northwest of Phoenix, became the template for retirement communities when Del E. Webb opened the community in 1960. Over 100,000 people visited the community during the opening weekend.[118]

As the financial crisis of 2007–10 began, construction in Phoenix collapsed in 2008, and housing prices plunged. Historically, Arizona trailed the rest of the country into recession but due to the prominence of the construction industry in its economy, Phoenix entered this last recession before the rest of the country.[119]

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis of the U.S. Department of Commerce, in 2012 (the latest year for which data is available), the Phoenix MSA had a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of just over $201 billion, a 4.5% increase over the prior year. Phoenix's GDP finally exceeded the high it had attained in 2008, prior to the recession. The top 10 industries were, in descending order: real estate ($31B), financial services ($21.3B), manufacturing ($16.8B), health care ($15.7B), retail ($14.9B), wholesale ($12.9B), professional services ($12.8B), construction ($10.4B), waste management ($9.1B), and tourism ($6.8B). Government, if it had been a private industry, would have been ranked third on the list, generating $18.9 billion.[114] Manufacturing now ranks third among Phoenix's industries, and includes the production of computers and other electronic equipment, missiles, aircraft parts, chemicals, and processed foods.[53]

In major job markets, as defined as those markets with greater than 1 million jobs, Greater Phoenix ranked number 1 in employment growth prior to the recession beginning in 2007. Just three years later, it ended its free fall in job growth by hitting the bottom of the list of those 28 major markets, dead last. However, 2013 saw Greater Phoenix rebound to 7th. Arizona's year-over-year job growth (of which Phoenix is the main driver) continued to outpace the nation through August 2013. Arizona's year-over-year job growth was at or above 2.0% each month of that year. In contrast, national job growth was between 1.5% and 1.7% on a year-over-year basis.[120][121] Arizona is forecast to regain its previous employment peak in 2015, making it eight years for the state to get back to even terms after the Great Recession; the national economy is currently forecast to replace all of the jobs lost by 2014, one year earlier than Arizona. This is due to the more severe downturn in Arizona as compared to the rest of the nation, as evidenced by the fact that from peak to trough, Arizona jobs declined by 11.8%, compared to 6.3% for the nation.[122] In 2013, the Phoenix area saw a 2.7% increase in non-farm employment, from 1.758 million to 1.805 million. Job growth has occurred across the board with the fastest rate in education and health services, trade, transportation and utilities, professional and business services, financial activities and leisure and hospitality.[123][124]

According to the 2010 Census, the top ten employment categories are office and administrative support occupations (17.8%), sales and related occupations (11.6%), food preparation and serving related occupations (9%), transportation and material moving occupations (6.1%), management occupations (5.8%), education, training, and library occupations (5.5%), business and financial operations occupations (5.3%), healthcare practitioners and technical occupations (5.3%), production occupations (4.6%), and construction and extraction occupations (4.2%). The single largest occupation is retail salespersons, which account for 3.7% of the entire workforce.[125] As of December, 2013, 12.9% of the workforce were government employees, a high number because the city is both the county seat and state capitol. The civilian labor force was 2,033,400 (down 0.5% from twelve months earlier), and the unemployment rate stood at 7.6%, above the national rate of 6.7%.[126][127]

Phoenix is currently home to four Fortune 500 companies: electronics corporation Avnet,[128] mining company Freeport-McMoRan,[129] retailer PetSmart[130] and waste hauler Republic Services.[131] Honeywell's Aerospace division is headquartered in Phoenix, and the valley hosts many of their avionics and mechanical facilities.[132] Intel has one of their largest sites in the area, employing about 12,000 employees, the second largest Intel location in the country; they are spending $5 billion to expand their semiconductor plant.[133] American Express hosts their financial transactions, customer information, and their entire website in Phoenix. The city is also home to: the headquarters of U-HAUL International, a rental and moving supply company; Best Western, the world's largest family of hotels; Apollo Group, parent of the University of Phoenix; and utility company Pinnacle West. Choice Hotels International has its IT division and operations support center in the North Phoenix area. US Airways, now merged with American Airlines has a strong presence in Phoenix, with the corporate headquarters located in the city prior to the merger. US Air/American Airlines is the largest carrier at Sky Harbor International Airport in Phoenix. Mesa Air Group, a regional airline group, is headquartered in Phoenix.[134]

The military has a significant presence in Phoenix with Luke Air Force Base located in the western suburbs. At its height, in the 1940s, the Phoenix area had three military bases: Luke Field (still in use), Falcon Field, and Williams Air Force Base (now Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport), with numerous auxiliary air fields located throughout the region.[135] Foreign governments have established 30 consular offices and eleven active foreign chambers of commerce and trade associations in metropolitan Phoenix.[136][137]

Culture

Performing arts

There are quite a few performing arts venues around the city, with most located in and around downtown Phoenix and Scottsdale. The Phoenix Symphony Hall is home to the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, the Arizona Opera and Ballet Arizona.[138] The Arizona Opera company also has intimate performances at its new Arizona Opera Center, which opened in March 2013.[139] Another venue is the Orpheum Theatre, which is home to the Phoenix Opera, formerly known as the Phoenix Metropolitan Opera.[140] Ballet Arizona, in addition to the Symphony Hall, also has performances at the Orpheum Theater as well at the Dorrance Theater. Concerts also regularly make stops in the area. The largest downtown performing art venue is the Herberger Theater Center, which houses three performance spaces and is home to two resident companies, the Arizona Theatre Company and the Centre Dance Ensemble. Three other groups also use the facility: Valley Youth Theatre, iTheatre Collaborative[141] and Actors Theater.[142]

Concerts can be seen at the US Airways Center and the Comerica Theatre in downtown Phoenix, Ak-Chin Pavilion (formerly Cricket Wireless Pavilion) in Maryvale, Jobing.com Arena in Glendale, and Gammage Auditorium in Tempe (the last public building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright).[143] Several smaller theatres including Trunk Space, the Mesa Arts Center, the Crescent Ballroom, Celebrity Theatre, and Modified Arts support regular independent musical and theatre performances. Music can also be seen in some of the venues usually reserved for sports, such as Wells Fargo Arena and University of Phoenix Stadium.[144]

Several television series were set in Phoenix, including Alice, the 2000s paranormal drama Medium, the 1960–61 syndicated crime drama The Brothers Brannagan, and The New Dick Van Dyke Show from 1971 to 1974.

Museums

Dozens of museums exist throughout the valley. They include the Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona Capitol Museum, Arizona Military Museum, Hall of Flame Firefighting Museum, the Pueblo Grande Museum and Cultural Park, Children's Museum of Phoenix, Arizona Science Center, and the Heard Museum. In 2010 the Musical Instrument Museum opened their doors, featuring the biggest musical instrument collection in the world.[145]

Designed by Alden B. Dow, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Phoenix Art Museum was constructed in a single year, opening in November 1959.[146] The Phoenix Art Museum presents a year-round program of festivals, live performances, independent art films and educational programs. The Southwest's largest destination for visual art, it displays international exhibitions alongside the museum's comprehensive collection of more than 17,000 works of contemporary and modern art from around the world, as well as exhibits of fashion design.[147][148][149] Interactive exhibits can be found in nearby Peoria's Challenger Space Center, where individuals learn about space, renewable energies, and meet astronauts.[150]

The Heard Museum has over 130,000 square feet (12,000 m²) of gallery, classroom and performance space. Some of the signature exhibits include a full Navajo hogan, the Mareen Allen Nichols Collection containing 260 pieces of contemporary jewelry, the Barry Goldwater Collection of 437 historic Hopi kachina dolls, and an exhibit on the 19th century boarding school experiences of Native Americans. The Heard Museum attracts about 250,000 visitors a year.[151]

Fine arts

The downtown Phoenix art scene has developed in the past decade. The Artlink organization and the galleries downtown have successfully launched a First Friday cross-Phoenix gallery opening. In April 2009, artist Janet Echelman inaugurated her monumental sculpture, Her Secret Is Patience, a civic icon suspended above the new Phoenix Civic Space Park, a two-city-block park in the middle of downtown. This netted sculpture makes the invisible patterns of desert wind visible to the human eye. During the day, the 100-foot (30 m)-tall sculpture hovers high above heads, treetops, and buildings, the sculpture creates what the artist calls "shadow drawings", which she says are inspired by Phoenix's cloud shadows. At night, the illumination changes color gradually through the seasons. Author Prof. Patrick Frank writes of the sculpture that "... most Arizonans look on the work with pride: this unique visual delight will forever mark the city of Phoenix just as the Eiffel Tower marks Paris."[152]

Architecture

Phoenix is the home of a unique architectural tradition and community. Frank Lloyd Wright moved to Phoenix in 1937 and built his winter home, Taliesin West, and the main campus for The Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[153] Over the years, Phoenix has attracted notable architects who have made it their home and have grown successful practices. These architectural studios embrace the desert climate, and are unconventional in their approach to the practice of design. They include the Paolo Soleri, Al Beadle, Will Bruder, Wendell Burnette, and Blank Studio architectural design studios.

Tourism

The tourist industry is the longest running of today's top industries in Phoenix. Starting with promotions back in the 1920s, the industry has grown into one of the top 10 in the city.[154] Due to its climate, Phoenix and its neighbors have consistently ranked among the nation's top destinations in the number of Five Diamond/Five Star resorts.[155] With more than 62,000 hotel rooms in over 500 hotels and 40 resorts, greater Phoenix sees over 16 million visitors each year, the majority of whom are leisure (as opposed to business) travelers.[156][157][158] Sky Harbor Airport, which serves the Greater Phoenix area, serves about 40 million passengers a year, ranking it among the 10 busiest airports in the nation.[155]

One of the biggest attractions to the Phoenix area is golf, with over 200 golf courses.[54][155] In addition to the sites of interest in the city, there are many attractions near Phoenix, such as: Agua Fria National Monument, Arcosanti, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Lost Dutchman State Park, Montezuma's Castle, Montezuma's Well, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Phoenix also serves as a jumping off point to many of the sights around the state of Arizona, such as the Grand Canyon, Lake Havasu (where the London Bridge is located), Meteor Crater, the Painted Desert, the Petrified Forest, Tombstone, Kartchner Caverns, Sedona and Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff.

Other attractions and annual events

Due to its natural beauty and climate, Phoenix has a plethora of outdoor attractions and recreational activities. The Phoenix Zoo is the largest privately owned, non-profit zoo in the United States. Since opening in 1962, the zoo has developed an international reputation for its efforts on animal conservation, including breeding and reintroducing endangered species back into the wild.[159] Right next to the zoo, the Phoenix Botanical Gardens were opened in 1939, and are acclaimed worldwide for their exhibits and educational programs, featuring the largest collection of arid plants in the U.S.[160][161][162] South Mountain Park, the largest municipal park in the U.S., is also the highest desert mountain preserve in the world.[163]

Other popular sites in the city are: Japanese Friendship Garden, Historic Heritage Square, Phoenix Mountains Park, Pueblo Grande Museum, Tovrea Castle, Camelback Mountain, Hole in the Rock, Mystery Castle, St. Mary's Basilica, Taliesin West, and the Wrigley Mansion.[164]

There are long list of annual events in and near Phoenix which celebrate the heritage of the city, as well as its diversity. Some of them are:[165][166]

- Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show — The largest Arabian horse show in the U.S. Held each February.

- Gold Rush Days (in nearby Wickenburg) - A rodeo and carnival held each March.

- Matsuri: A Festival of Japan — A celebration of Japanese culture held in February.

- Pueblo Grande Indian Market — A December event highlighting Native American arts and crafts.

- Christmas Mariachi Festival — Features world renowned mariachi bands and dancers.

- Grand Menorah Lighting — Annual December event celebrating Hanukah.

- Candyland Concert — Interactive children's festival in late November.

- ZooLights — Annual December evening event at the Phoenix Zoo, featuring millions of lights.

- Arizona State Fair — Begun in 1884, annual fair in September.

- Scottish Gathering & Highland Games - 2014 marks the 50th year of this annual event celebrating Scottish heritage.[167]

- Cave Creek Fiesta Days Rodeo & Parade — Annual March rodeo and festival.

- Polish Festival — Annual festival held in March.[168]

- Estrella War — Annual event celebrating medieval life, held in February/March.[169]

- Tohono O’odham Nation Rodeo & Fair — Oldest Indian rodeo in Arizona, held in February.

- Chinese Week & Culture & Cuisine Festival — Annual celebration of Chinese culture in February.

Cuisine

Like many other western towns, the earliest restaurants in Phoenix were often steakhouses. In addition, Phoenix is also renowned for authentic Mexican food, thanks to both the large Hispanic population and proximity to Mexico. Like other major cities, some of the restaurants have a long and storied history. The Stockyards steakhouse dates to 1947, while Monti's La Casa Vieja (Spanish for "The Old House") has been in operation as a restaurant since the 1890s.[170][171] Macayo's (a Mexican restaurant chain) was established in Phoenix in 1946, and other major Mexican restaurants include Garcia's (1956) and Manuel's (1964).[172] The recent population boom has brought people from all over the nation, and to a lesser extent from other countries, and has since influenced the local cuisine. Today Phoenix, like most other large cities in the U.S. boasts cuisines from all over the world, such as Korean, barbecue, Cajun/Creole, Greek, Hawaiian, Irish, Japanese, sushi, Italian, fusion, Persian, Indian, Spanish, Thai, Chinese, southwestern, tex-mex, Vietnamese, Brazilian, and French.[173]

Although a McDonald's restaurant which opened in Des Plaines, Illinois in 1955 is often incorrectly identified as the first franchise, the McDonald brothers actually sold their first franchise to a Phoenix entrepreneur in 1952. Neil Fox paid $1,000 for the rights to open an establishment based on the McDonald's brothers' restaurant. The McDonalds anticipated that once they had received the fee, they would have no further involvement with the property. Expecting the new restaurant to be called "Fox's", they were shocked when they learned that Fox wanted to call it McDonalds, "'What the hell for?' Dick McDonald asked Fox, 'McDonald's' means nothing in Phoenix.'"[174] The hamburger stand opened in 1953 on the southwest corner of Central Avenue and Indian School Road on the growing north side of Phoenix, and was the first location to sport the now internationally known "arches", which were twice the height of the building. Three other franchise locations opened that year, a full two years before Kroc purchased McDonald's and opened his first franchise in Illinois. It was also the site where the trademark "Golden Arches" were first used.[174]

Sports

Phoenix is home to several professional sports franchises, and is one of only 12 U.S. cities to have representatives of all four major professional sports leagues, although only two of these teams actually carry the city name and play within the city limits.

The Phoenix Suns were the first major sports team in Phoenix, being granted a National Basketball Association (NBA) franchise in 1968.[175] Jerry Colangelo was their first general manager, the youngest in the league up to that time, and their name was chosen through a contest through the Arizona Republic. They originally played at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum, moving to the America West Arena (now U.S. Airways Center) in 1992.[176] The year following their move to the new arena, the Suns made the NBA finals for the second time in franchise history, losing to Michael Jordan's Chicago Bulls, 4 games to 2.[177] In 1997, the Phoenix Mercury were one of the original eight teams to launch the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA). They also play at U.S. Airways Center. They have been to the WNBA championship series three times, losing in 1998 to the Houston Comets, before winning their first WNBA championship in 2007, when they defeated the Detroit Shock in five games.[178] They would repeat their championship in 2009, when they defeated the Indiana Fever.[179]

The Arizona Diamondbacks of Major League Baseball (National League West Division) began play as an expansion team in 1998. The team has played all of its home games in the same downtown park; originally called Bank One Ballpark (or "BOB" for short), in 2005 the stadium's name was changed to Chase Field.[180][181] It is the second highest stadium in the U.S. (after Coors Field in Denver), and is famous for its nationally-known swimming pool beyond the outfield fence.[182] In 2001, the Diamondbacks defeated the New York Yankees 4 games to 3 in the World Series,[183] becoming the city's first professional sports franchise to win a national championship while located in Arizona. The win was also the fastest an expansion team had ever won the World Series, surpassing the old mark of the Florida Marlins of 5 years, set in 1997.[184]

The Arizona Cardinals are the oldest continuously run professional football franchise in the nation. They moved to Phoenix from St. Louis, Missouri in 1988 and currently play in the Western Division of the National Football League's National Football Conference. The Cardinals were founded in 1898 in Chicago, as the Morgan Athletic Club, and became known as the Cardinals shortly after, due to the color of their jerseys. Around the turn of the last century, they were known as the Racine Cardinals, and in 1920, they became a charter member of the American Professional Football League, which would eventually become the National Football League. Upon their move to Phoenix, the Cardinals originally played their home games at Sun Devil Stadium on the campus of Arizona State University in nearby Tempe. In 2006 they moved to the newly constructed University of Phoenix Stadium in suburban Glendale.[185] Since moving to Phoenix, the Cardinals have made one championship appearance, Super Bowl XLIII on February 1, 2009, where they lost 27-23 to the Pittsburgh Steelers.[186]

The Arizona Coyotes of the National Hockey League moved to the area in 1996,[187] formerly known as the Winnipeg Jets. They originally played their home games downtown at America West Arena before moving in December 2003 to the Jobing.com Arena, adjacent to University of Phoenix Stadium in Glendale.[188]

Phoenix has an arena football team, the Arizona Rattlers of the Arena Football League. Games are played at U.S. Airways Center in downtown Phoenix. They won their first of four AFL championships in 1994; in 2013 they won their second championship in a row.[189]

The Greater Phoenix area is home to the Cactus League, one of two spring training leagues for Major League Baseball. With the move by the Colorado Rockies and the Arizona Diamondbacks to their new facility in Scottsdale, the league is entirely based in the Greater Phoenix area, as opposed to the Grapefruit League, which is spread throughout southern Florida. With the Cincinnati Reds' move to Goodyear, fifteen of MLB's thirty teams are now included in the Cactus League.[190]

The Phoenix International Raceway, was built in 1964 with a one-mile oval, with a one-of-a-kind design, as well as a 2.5-mile road course.[191] Today, "Phoenix International Raceway has a tradition that is unmatched in the world of racing."[192] It currently hosts several NASCAR events per season,[193][194] and the annual Fall NASCAR weekend, which includes events from four different NASCAR classes, is a huge event.[192] After thirty years of hosting various events, especially NHRA drag racing events, Firebird International Raceway (FIR) closed operations in 2013.[195] However, the NHRA negotiated a deal with the Gila River Indian Community (the owners of FIR) and re-opened the venue to NHRA events in 2014, under the new name, "Wild Horse Pass Motorsports Park".[196] Phoenix hosted the United States Grand Prix from 1989 to 1991. The race was discontinued after the 1991 edition due to poor attendance.[197]

The Phoenix Marathon is a new addition to the city's sports scene, and is a qualifier for the Boston Marathon.[198] The Rock 'n' Roll Marathon series has held an event in Phoenix every January since 2004.[199]

Sun Devil Stadium held Super Bowl XXX in 1996 when the Dallas Cowboys defeated the Pittsburgh Steelers.[200] University of Phoenix Stadium hosted Super Bowl XLII on February 3, 2008, in which the New York Giants defeated the New England Patriots.[201] The University of Phoenix Stadium will host Super Bowl XLIX in 2015.[202] The U.S. Airways Center hosted both the 1995 and the 2009 NBA All-Star Games.[203]

The Phoenix area is the site of two college football bowl games: the Buffalo Wild Wings Bowl, formerly known as the Insight Bowl, which was at Chase Field until 2005, after which it moved to Sun Devil Stadium;[204] and the Fiesta Bowl, played at the University of Phoenix Stadium.[205] The city is also host to several major professional golf events, including the LPGA's Founder's Cup[206] and, since 1932, The Phoenix Open of the PGA.[207]

Phoenix's Ahwatukee American Little League reached the 2006 Little League World Series as the representative from the U.S. West region.

Professional clubs

*Note: The Cardinals won 2 of their championships while in Chicago, pre-modern era.

Semi-professional and amateur clubs

| Club | Sport | League | Venue | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona Scorpions | Basketball | American Basketball Association | Phoenix College | 0 |

| Arizona Derby Dames | Banked Track Roller Derby | Roller Derby Coalition of Leagues | Hall of Dames | 0 |

Parks and recreation

Phoenix is home to a large number of parks and recreation areas. The city of Phoenix includes national parks, county (Maricopa County) parks and city parks. Tonto National Forest forms part of the northeast boundary of the city, while the county has the largest park system in the country.[208] The city park system was established to preserve the desert landscape in areas that would otherwise have succumbed to development, and includes South Mountain Park, the world's largest municipal park with 16,500 acres (67 km2).[209] The city park system has 189 parks which contain over 33,000 acres, and has facilities for hiking, camping, swimming, horseback riding, cycling, and climbing.[210] Some of the other notable parks in the system are Camelback Mountain, Encanto Park (another large urban park) and Sunnyslope Mountain, also known as "S" Mountain.[211] Papago Park in east Phoenix is home to both the Desert Botanical Garden and the Phoenix Zoo, in addition to several golf courses and the Hole-in-the-Rock geological formation. The Desert Botanical Garden, which opened in 1939, is one of the few public gardens in the country dedicated to desert plants, and displays desert plant life from all over the world. The Phoenix Zoo is the largest privately owned non-profit zoo in the United States, and is internationally known for its programs devoted to saving endangered species.[212]

In addition, many waterparks are scattered throughout the valley to help residents cope with the desert heat during the summer months. Some of the notable parks include Big Surf in Tempe, Wet 'n' Wild Phoenix in Phoenix, Golfland Sunsplash in Mesa, and the Oasis Water Park at the Arizona Grand Resort – formerly known as Pointe South Mountain Resort – in Phoenix. The area also has two small amusement parks, Castles N' Coasters in north Phoenix, next to the Metrocenter Mall and Enchanted Island located at Encanto Park.

Government

In 1913, Phoenix adopted a new form of government, switching from the mayor-council system to the council-manager system, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government, where a strong city manager supervises all city departments and executes the policies adopted by the Council.[213][214]

The city council consists of a mayor and eight city council members. While the mayor is elected in a citywide election, Phoenix City Council members are elected by votes only in the districts they represent, with both the Mayor and the Council members serving four year terms.[215] The current mayor of Phoenix is Greg Stanton, a Democrat who was elected to a four-year term in 2011.[216] In setting city policy and passing rules and regulations, the mayor and city council members each have equal voting power.[215] The city's website was given a "Sunny Award" by Sunshine Review for its transparency efforts.[217][218]

State government facilities

As the capital of Arizona, Phoenix houses the state legislature,[219] along with numerous state government agencies, many of which are located in the State Capitol district immediately west of downtown. The Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections operates the Adobe Mountain and Black Canyon Schools in Phoenix.[220] Another major state government facility is the Arizona State Hospital, operated by the Arizona Department of Health Services. This is a mental health center which is the only medical facility run by the state government.[221] The headquarters of numerous Arizona state government agencies are in Phoenix, with many located in the State Capitol district immediately west of downtown.

Federal government facilities

The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Phoenix which is in the city limits, near its northern boundary.[222]

The Sandra Day O'Connor U.S. Courthouse, the U.S. District Court of Arizona, is located on Washington Street downtown. It is named in honor of retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who was raised in Arizona.[223]

The Federal Building is at the intersection of Van Buren Road and First Avenue downtown, and contains various federal field offices and the local division of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.[224] This building also formerly housed the U.S. District Court offices and courtrooms, but these were moved in 2001 to the new Sandra Day O'Connor U.S. Courthouse. Before the construction of this building in 1961, federal government offices were housed in the historic U.S. Post Office on Central Avenue, completed in the 1930s.[225]

Crime

By the 1960s crime was becoming a significant problem in Phoenix, and by the 1970s crime continued to increase in the city at a faster rate than almost anywhere else in the country.[226] It was during this time frame when an incident occurred in Phoenix which would have national implications. On March 16, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested and charged with the rape of a mildly retarded teen-aged girl.[227] The subsequent Supreme Court ruling on June 13, 1966, in the matter of Miranda v. Arizona, has led to practice in the United States of issuing a Miranda Warning to all suspected criminals.[228]

By the mid 1970s, Phoenix was close to or at the top of the list for cities with the highest crime rate. The mayor during the mid-70s, Mayor Graham, introduced policies which raised Phoenix from near the bottom of the statistics regarding police officers per capita, to where it resided in the middle of the rankings. He also implemented other changes, including establishing a juvenile department within the police force. With Phoenix's rapid growth, it drew the attention of con men and racketeers, with one of the prime areas of activity being land fraud. The practice became so widespread that newspapers would refer to Phoenix as the Tainted Desert.[229]

These land frauds led to one of the more infamous murders in the history of the valley, when Arizona Republic writer Don Bolles was murdered by a car bomb at the Clarendon Hotel in 1976.[230][231] It was believed that his investigative reporting on organized crime and land fraud in Phoenix made him a target.[232] Bolles' last words referred to Phoenix land and cattle magnate Kemper Marley,[233] who was widely regarded to have ordered Bolles' murder, as well as John Harvey Adamson, who pleaded guilty to second-degree murder in 1977 in return for testimony against contractors Max Dunlap and James Robison.[234]

The trial gained national attention since Bolles was the only reporter from a major U.S. newspaper to be murdered on U.S. soil due to his coverage of a story, and led to reporters from all over the country descending on Phoenix to cover his murder.[232] Dunlap was convicted of first degree murder in the case in 1990 and remained in prison, until his death on July 21, 2009, while Robison was acquitted, but pleaded guilty to charges of soliciting violence against Adamson.[234] Street gangs and the drug trade had turned into public safety issues by the 1980s. Despite continued improvements in the size of the police force and other anti-crime measures, the crime rate in Phoenix continued to grow, albeit at a lower growth rate than other southwestern cities.[235]

After seeing a peak in the early and mid 1990s, the city has seen a general decrease in both the violent and property crime rates. 1993 saw the creation of "Tent City," by Sheriff Joe Arpaio, using inmate labor, to alleviate overcrowding in the Maricopa County Jail system, the fourth-largest in the world.[48] The violent crime rate peaked in 1993 at 1146 crimes per 100,000 people, while the property crime rate peaked a few years earlier, in 1989, at 9,966 crimes per 100,000. In the most recent numbers from the FBI (2012), those rates currently stand at 637 and 4091, respectively. When compared to the other cities on the 10 most populated list, this ranks Phoenix 5th and 6th, respectively. Since their peak in 2003, murders have dropped from 241 to 123 in 2012. Assaults have also dropped from 7,800 in 1993 to 5,260 in 2012. In the 20 years since 1993, there have only been five years in which the violent crime rate has not declined.[236]

The year 2012 was an anomaly to the general downward trend in violent crime in Phoenix, with the rates for every single violent crime, except rape, showing an increase. The murder rate increased by 15.4% and aggravated assaults jumped by 27%, while rapes were down by 2%. However, the property crime rate returned to the downward trend begun in the 1990s, after a slight uptick in the previous two years. Vehicle thefts, which have been perceived as a major issue in the Valley of the Sun for decades, saw a continuation of a downward trend begun over a decade ago.[236] In 2001 Phoenix ranked first in the nation in vehicle thefts, with over 22,000 cars stolen that year.[237] That continued in 2002, when car thefts rose to over 25,000, a rate of over 1,825 thefts per 100,000 people. It has declined every year since then, and last year stood at just over 480, a drop of almost 75% in the decade. According to the "Hot Spots" report put out by the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB), The Phoenix MSA has dropped to 70th in the nation in terms of car thefts in 2012.[238]

As the first decade of the new century came to a close, Arizona had become the gateway to the U.S. for drug trafficking. By 2009, seizures in Arizona amounted for approximately half of all Marijuana captured along the U.S.-Mexican border.[239] Another crime issue related to the drug trade are kidnappings. In the late 2000s, Phoenix earned the title "Kidnapping capital of the USA".[240] The majority of the kidnapped are believed to be victims of human smuggling, or related to illegal drug trade, while the kidnappers are believed to be part of Mexican drug cartels, particularly the Sinaloa cartel.[239]

| Violent crime in Phoenix 1985–2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| Property crime in Phoenix 1985–2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||