Oregon

Oregon | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Oregon Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | February 14, 1859 (33rd) |

| Capital | Salem |

| Largest city | Portland |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Portland metropolitan area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Kate Brown (D) |

| • State Treasurer | Ted Wheeler (D) |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly |

| • Upper house | State Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Ron Wyden (D) Jeff Merkley (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 4 Democrats, 1 Republican (list) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 4,028,977 (2,015 est.)[1] |

| • Density | 39.9/sq mi (15.0/km2) |

| • Median household income | $48,457 (2,014) |

| • Income rank | 24th |

| Language | |

| • Official language | De jure: none[2] De facto: English |

| Traditional abbreviation | Ore. |

| Latitude | 42° N to 46° 18′ N |

| Longitude | 116° 28′ W to 124° 38′ W |

Oregon (/ˈɔːr[invalid input: 'ɨ']ɡən/ OR-ə-gən)[6] is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Oregon is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean, on the north by Washington, on the south by California, on the east by Idaho, and on the southeast by Nevada. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary, and the Snake River delineates much of the eastern boundary. The parallel 42° north delineates the southern boundary with California and Nevada. It is one of only three states of the contiguous United States to have a coastline on the Pacific Ocean, and its proximity to the ocean heavily influences the state's mild winter climate despite its northern latitude.

Oregon was inhabited by many indigenous tribes before Western traders, explorers, and settlers arrived. An autonomous government was formed in the Oregon Country in 1843 before the Oregon Territory was created in 1848. Oregon became the 33rd state on February 14, 1859. Today, at 98,000 square miles (255,000 km²), Oregon is the ninth largest and, with a population of 4 million, 27th most populous U.S. state. The capital of Oregon is Salem, the second most populous of its cities, with 164,549 residents (2015 estimate). Portland is Oregon's most populous city, with 632,309 residents (2015 estimate), and ranks as the 26th most populous city in the United States. Portland's metro population of 2,389,228 (2015 estimate) ranks the 23rd largest metro in the nation. The Willamette Valley in western Oregon is the state's most densely populated area, home to eight of the ten most populous cities.

Oregon's landscape is diverse, with a windswept Pacific coastline; a volcano-studded Cascade Range; abundant bodies of water in and west of the Cascades; dense evergreen, mixed, and deciduous forests at lower elevations; and a high desert sprawling across much of its east all the way to the Great Basin. The tall conifers, mainly Douglas fir, along Oregon's rainy west coast contrast with the lighter-timbered and fire-prone pine and juniper forests covering portions to the east. Abundant alders in the west fix nitrogen for the conifers. Stretching east from central Oregon are semi-arid shrublands, prairies, deserts, steppes, and meadows. At 11,249 feet (3,429 m), Mount Hood is the state's highest point. Oregon's only national park, Crater Lake National Park, comprises the caldera surrounding Crater Lake, the deepest lake in the United States.

Etymology

The earliest evidence of the name Oregon has Spanish origins. The term "orejón" comes from the historical chronicle Relación de la Alta y Baja California (1598)[8] written by the new Spaniard Rodrigo Motezuma and made reference to the Columbia river when the Spanish explorers penetrated into the actual north american territory that became part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. This chronicle is the first topographical and linguistic source with respect to the place name Oregon. There are also two other sources with Spanish origins such as the name Oregano which grows in the southern part of the region. It is most probable that the American territory was named by the Spaniards as there are some populations in Spain such as "Arroyo del Oregón" which is situated in the province of Ciudad Real, also considering that the individualization in Spanish language "El Orejón" with the mutation of the letter "g" instead of "j".[9]

Another early use of the name, spelled Ouragon, was in a 1765 petition by Major Robert Rogers to the Kingdom of Great Britain. The term referred to the then-mythical River of the West (the Columbia River). By 1778 the spelling had shifted to Oregon.[10] In his 1765 petition, Rogers wrote:

The rout [sic]...is from the Great Lakes towards the Head of the Mississippi, and from thence to the River called by the Indians Ouragon...[11]

One theory is the name comes from the French word ouragan ("windstorm" or "hurricane"), which was applied to the River of the West based on Native American tales of powerful Chinook winds of the lower Columbia River, or perhaps from firsthand French experience with the Chinook winds of the Great Plains. At the time, the River of the West was thought to rise in western Minnesota and flow west through the Great Plains.[12]

Joaquin Miller explained in Sunset magazine, in 1904, how Oregon's name was derived:

The name, Oregon, is rounded down phonetically, from Aure il agua—Oragua, Or-a-gon, Oregon—given probably by the same Portuguese navigator that named the Farallones after his first officer, and it literally, in a large way, means cascades: 'Hear the waters.' You should steam up the Columbia and hear and feel the waters falling out of the clouds of Mount Hood to understand entirely the full meaning of the name Aure il agua, Oregon.[13]

Another account, endorsed as the "most plausible explanation" in the book Oregon Geographic Names, was advanced by George R. Stewart in a 1944 article in American Speech. According to Stewart, the name came from an engraver's error in a French map published in the early 18th century, on which the Ouisiconsink (Wisconsin) River was spelled "Ouaricon-sint," broken on two lines with the -sint below, so there appeared to be a river flowing to the west named "Ouaricon."

According to the Oregon Tourism Commission (doing business as Travel Oregon), present-day Oregonians /ˌɒr[invalid input: 'ɨ']ˈɡoʊniənz/[14] pronounce the state's name as "or-uh-gun, never or-ee-gone."[6]

After being drafted by the Detroit Lions in 2002, former Oregon Ducks quarterback Joey Harrington distributed "Orygun" stickers to members of the media as a reminder of how to pronounce the name of his home state.[15][16] The stickers are sold by the University of Oregon Bookstore.[17]

History

Humans have inhabited the area that is now Oregon for at least 15,000 years. In recorded history, mentions of the land date to as early as the 16th century. During the 18th and 19th centuries, European powers – and later the United States – quarreled over possession of the region until 1846, when the U.S. and Great Britain finalized division of the region. Oregon became a state in 1859 and is now home to over 3.97 million residents.

Earliest inhabitants

While there is considerable evidence that Paleo-Indians inhabited the region, the oldest evidence of habitation in Oregon was found at Fort Rock Cave and the Paisley Caves in Lake County. Archaeologist Luther Cressman dated material from Fort Rock to 13,200 years ago,[18] and there is evidence supporting inhabitants in the region at least 15,000 years ago.[19] By 8000 BC there were settlements throughout the state, with populations concentrated along the lower Columbia River, in the western valleys, and around coastal estuaries.

During the prehistoric period, the Willamette Valley region was flooded after the collapse of glacial dams from Lake Missoula, located in what would later become Montana. These massive floods occurred during the last ice age and filled the valley with 300 to 400 feet (91 to 122 m) of water.[20]

By the 16th century, Oregon was home to many Native American groups, including the Coquille (Ko-Kwell), Bannock, Chasta, Chinook, Kalapuya, Klamath, Molalla, Nez Perce, Takelma, Tillamook and Umpqua.[21][22][23][24]

European exploration

The first Europeans to visit Oregon were Spanish explorers led by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo who sighted southern Oregon off the Pacific Coast in 1543.[25] Francis Drake made his way to Nehalem Bay in 1579 and spent 5 weeks in the middle of summer repairing his ship and claimed the land between 38-48 degrees N latitude as a Symbolic Sovereign Act for England.[26] Exploration was retaken routinely in 1774, starting with the expedition of the frigate Santiago by Juan José Pérez Hernández (see Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest), and the coast of Oregon became a valuable trading route to Asia. In 1778, British captain James Cook also explored the coast.[27]

French Canadian and métis trappers and missionaries arrived in the eastern part of the state in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, many having travelled as members of Lewis and Clark and the 1811 Astor expeditions. Some stayed permanently, including Étienne Lussier, believed to be the first European farmer in the state of Oregon. The evidence of this French Canadian presence can be found in the numerous names of French origin in that part of the state, including Malheur Lake and the Malheur River, the Grande Ronde and Deschutes rivers, and the city of La Grande.

During U.S. westward expansion

The Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled through northern Oregon also in search of the Northwest Passage. They built their winter fort in 1805–06 at Fort Clatsop, near the mouth of the Columbia River, staying at the encampment from December until March.[28]

British explorer David Thompson also conducted overland exploration. In 1811, while working for the North West Company, Thompson became the first European to navigate the entire Columbia River. Stopping on the way, at the junction of the Snake River, he posted a claim to the region for Great Britain and the North West Company. Upon returning to Montreal, he publicized the abundance of fur-bearing animals in the area.

Also in 1811, New Yorker John Jacob Astor financed the establishment of Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River as a western outpost to his Pacific Fur Company;[29] this was the first permanent European settlement in Oregon.

In the War of 1812, the British gained control of all Pacific Fur Company posts. The Treaty of 1818 established joint British and American occupancy of the region west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. By the 1820s and 1830s, the Hudson's Bay Company dominated the Pacific Northwest from its Columbia District headquarters at Fort Vancouver (built in 1825 by the district's chief factor, John McLoughlin, across the Columbia from present-day Portland).

In 1841, the expert trapper and entrepreneur Ewing Young died leaving considerable wealth and no apparent heir, and no system to probate his estate. A meeting followed Young's funeral at which a probate government was proposed. Doctor Ira Babcock of Jason Lee's Methodist Mission was elected supreme judge. Babcock chaired two meetings in 1842 at Champoeg, (half way between Lee's mission and Oregon City), to discuss wolves and other animals of contemporary concern. These meetings were precursors to an all-citizen meeting in 1843, which instituted a provisional government headed by an executive committee made up of David Hill, Alanson Beers, and Joseph Gale. This government was the first acting public government of the Oregon Country before annexation by the government of the United States.

Also in 1841, Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, reversed the Hudson's Bay Company's long-standing policy of discouraging settlement because it interfered with the lucrative fur trade. He directed that some 200 Red River Colony settlers be relocated to HBC farms near Fort Vancouver, (the James Sinclair expedition), in an attempt to hold Columbia District.

Starting in 1842–1843, the Oregon Trail brought many new American settlers to Oregon Country. For some time, it seemed that Britain and the United States would go to war for a third time in 75 years (see Oregon boundary dispute), but the border was defined peacefully in 1846 by the Oregon Treaty. The border between the United States and British North America was set at the 49th parallel. The Oregon Territory was officially organized in 1848.

Settlement increased with the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the forced relocation of the native population to Indian reservations in Oregon.

African American history

As the nation expanded west, those making their way to the newly expanded territories often took their slaves with them, despite slavery being prohibited in the new territories.[30] While slaves were present they were not recorded as slaves on documents, due to slavery's illegal status. Some territories took harsh and firm stances against blacks, and Oregon was among them.

In December 1844, Oregon passed its Black Exclusion Law, which prohibited African Americans from entering the territory while simultaneously prohibiting slavery. Slave owners who brought their slaves with them were given three years before they were forced to free them. Any African Americans in the region after the law was passed were forced to leave, those who did not comply were arrested and beaten. They received no less than twenty and no more than thirty-nine stripes across their bare back. If they still did not leave, this process could be repeated every six months.[31]

Although slavery was prohibited in Oregon, it persisted even into its statehood.[32] In fact, in 1852 Robin Holmes was forced to file a lawsuit against his former owner, Nathaniel Ford. Ford held Holmes and his family as slaves in the Oregon territory and eventually freed Holmes, his wife, and infant child; but refused to release Holmes' three older children. The case made its way to the Oregon Supreme Court where Holmes won and Ford was required to release the children.[33]

Slavery played a major part in Oregon's history and even influenced its path to statehood. The territory's request for statehood was delayed several times, as Congress argued among themselves whether it should be admitted as a "free" or "slave" state. Eventually politicians from the south agreed to allow Oregon to enter as a "free" state, in exchange for opening slavery to the southwest United States.[34]

After statehood

Oregon was admitted to the Union on February 14, 1859. Founded as a refuge from disputes over slavery, Oregon had a "whites only" clause in its original state Constitution.[35]

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, regular U.S. troops were withdrawn and sent east. Volunteer cavalry recruited in California were sent north to Oregon to keep peace and protect the populace. The First Oregon Cavalry served until June 1865.

Beginning in the 1880s, the growth of railroads expanded the state's lumber, wheat, and other agricultural markets, and the rapid growth of its cities.[36] Due to its abundance of timber and waterway access via the Willamette River, Portland became a major force in the lumber industry of the Pacific Northwest, and quickly became the state's largest city. It would earn the nickname "Stumptown,"[37] and would later become recognized as one of the most dangerous port cities in the United States due to racketeering and illegal activities at the turn of the 20th century.[38]

20th and 21st centuries

In 1902, Oregon introduced direct legislation by the state's citizens through initiatives and referenda, known as the Oregon System.

On May 5, 1945, six people were killed by a Japanese bomb that exploded on Gearhart Mountain near Bly.[39][40] This is the only fatal attack on the United States mainland committed by a foreign nation since the Mexican–American War, making Oregon the only U.S. state that has experienced fatal casualties by a foreign army since 1848, as Hawaii was not yet a state when Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941. The bombing site is now called the Mitchell Recreation Area.

Industrial expansion began in earnest following the 1933–1937 construction of the Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River. Hydroelectric power, food, and lumber provided by Oregon helped fuel the development of the West, although the periodic fluctuations in the U.S. building industry have hurt the state's economy on multiple occasions. Portland in particular experienced a population boom between 1900 and 1930, tripling in size; the arrival of World War II also provided the northwest region of the state with an industrial boom, where Liberty ships and aircraft carriers were constructed.[41]

During the 1970s, the Pacific Northwest was particularly affected by the 1973 oil crisis, with Oregon suffering a substantial shortage.[42]

In 1994, Oregon became the first U.S. state to legalize physician-assisted suicide through the Oregon Death with Dignity Act. A measure to legalize recreational use of marijuana in Oregon was approved on November 4, 2014, making Oregon only the second state to have legalized gay marriage, physician-assisted suicide, and recreational marijuana.

Geography

| Entity | Location |

|---|---|

| Crater Lake National Park | Southern Oregon |

| John Day Fossil Beds National Monument | Eastern Oregon |

| Newberry National Volcanic Monument | Central Oregon |

| Cascade–Siskiyou National Monument | Southern Oregon |

| Oregon Caves National Monument | Southern Oregon |

| California Trail | Southern Oregon, California |

| Fort Vancouver National Historic Site | Western Oregon, Washington |

| Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail | IL, MO, KS, IA, NE, SD, ND, MT, ID, OR, WA |

| Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks | Western Oregon, Washington |

| Nez Perce National Historical Park | MT, ID, OR, WA |

| Oregon Trail | MO, KS, NE, WY, ID, OR |

Oregon's geography may be split roughly into eight areas:

- Oregon Coast—west of the Coast Range

- Willamette Valley

- Rogue Valley

- Cascade Range

- Klamath Mountains

- Columbia Plateau

- High Desert

- Blue Mountains

The mountainous regions of western Oregon, home to three of the most prominent mountain peaks of the United States including Mount Hood, were formed by the volcanic activity of the Juan de Fuca Plate, a tectonic plate that poses a continued threat of volcanic activity and earthquakes in the region. The most recent major activity was the 1700 Cascadia earthquake. Washington's Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980, an event that was visible from northern Oregon and affected some areas there.

The Columbia River, which forms much of the northern border of Oregon, also played a major role in the region's geological evolution, as well as its economic and cultural development. The Columbia is one of North America's largest rivers, and one of two rivers to cut through the Cascades (the Klamath River in Southern Oregon is the other). About 15,000 years ago, the Columbia repeatedly flooded much of Oregon during the Missoula Floods; the modern fertility of the Willamette Valley is largely a result of those floods. Plentiful salmon made parts of the river, such as Celilo Falls, hubs of economic activity for thousands of years. In the 20th century, numerous hydroelectric dams were constructed along the Columbia, with major impacts on salmon, transportation and commerce, electric power, and flood control.

Today, Oregon's landscape varies from rain forest in the Coast Range to barren desert in the southeast, which still meets the technical definition of a frontier.

Oregon is 295 miles (475 km) north to south at longest distance, and 395 miles (636 km) east to west at longest distance. In land and water area, Oregon is the ninth largest state, covering 98,381 square miles (254,810 km2).[43] The highest point in Oregon is the summit of Mount Hood, at 11,249 feet (3,429 m), and its lowest point is the sea level of the Pacific Ocean along the Oregon Coast.[44] Oregon's mean elevation is 3,300 feet (1,006 m). Crater Lake National Park is the state's only national park and the site of Crater Lake, the deepest lake in the U.S. at 1,943 feet (592 m).[45] Oregon claims the D River as the shortest river in the world,[46] though the state of Montana makes the same claim of its Roe River.[47] Oregon is also home to Mill Ends Park (in Portland),[48] the smallest park in the world at 452 square inches (0.29 m2).

Oregon's geographical center is further west than that of any of the other 48 contiguous states (although the westernmost point of the lower 48 states is in Washington). Its antipodes, diametrically opposite its geographical center on the Earth's surface, is at 44°00′S 59°30′E / 44°S 59.5°E in the Indian Ocean northwest of Port-aux-Français in the French Southern and Antarctic Lands. Oregon lies in two time zones. Most of Malheur County is in the Mountain Time Zone while the rest of the state lies in the Pacific Time Zone.

Oregon is home to what is considered the largest single organism in the world, an Armillaria solidipes fungus beneath the Malheur National Forest of eastern Oregon.[49]

- Images of Oregon

-

Mount Hood, with Trillium Lake in the foreground

-

An aerial view of Crater Lake

-

The High Desert region of Oregon

-

Downtown Eugene as seen from Skinner Butte in North Eugene

-

Roxy Ann Peak, seen from Medford

-

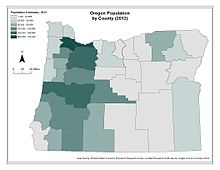

Map of Oregon's population density

-

Nearly half of Oregon's land is held by the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management[50]

Major cities

Oregon's population is largely concentrated in the Willamette Valley, which stretches from Eugene in the south (home of the University of Oregon) through Corvallis (home of Oregon State University) and Salem (the capital) to Portland (Oregon's largest city).[52]

Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River, was the first permanent English-speaking settlement west of the Rockies in what is now the United States. Oregon City, at the end of the Oregon Trail, was the Oregon Territory's first incorporated city, and was its first capital from 1848 until 1852, when the capital was moved to Salem. Bend, near the geographic center of the state, is one of the ten fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the United States.[53] In the southern part of the state, Medford is a rapidly growing metro area, which is home to The Rogue Valley International-Medford Airport, the third-busiest airport in the state. To the south, near the California-Oregon border, is the community of Ashland, home of the Tony Award-winning Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

Climate

Oregon's climate is generally mild. The state has an oceanic climate west of the Cascade mountain range. The climate varies with dense evergreen mixed forests spreading across much of the west, and a high desert sprawling to the east. The southwestern portion of the state, particularly the Rogue Valley, has a Mediterranean climate with drier and sunnier winters and hotter summers, similar to Northern California.

The northeastern portion of Oregon has a steppe climate, and the high terrain regions have a subarctic climate. Like Western Europe, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest in general, is considered warm for its latitude, and the state has far milder winters for the given elevation than the comparable latitude parts of North America, such as the Upper Midwest, Ontario, Quebec and New England.

Western Oregon's climate is heavily influenced by the Pacific Ocean. The western third of Oregon is very wet in the winter, moderately to very wet during the spring and fall, and dry during the summer. The relative humidity of Western Oregon is high except during summer days, which are semi-dry to semi-humid; Eastern Oregon typically sees low humidity year-round.

The eastern two thirds of Oregon have cold, snowy winters and very dry summers; much of it is semiarid to arid like the rest of the Great Basin, though the Blue Mountains are wet enough to support extensive forests.

Most of the state does get significant snowfall, but 70 percent of Oregon's population lives in the Willamette Valley,[54] which has exceptionally mild winters for its latitude and typically only sees a few light snows each year. This gives Oregon a reputation of being relatively "snowless".

Oregon's highest recorded temperature is 119 °F (48 °C) at Pendleton on August 10, 1898, and the lowest recorded temperature is −54 °F (−48 °C) at Seneca on February 10, 1933.[55]

The table below lists the averages for selected areas of Oregon, including the largest cities and largest coastal city Astoria.

| Location | August (°F) | August (°C) | December (°F) | December (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portland | 81/58 | 27/13 | 45/35 | 7/2 |

| Salem | 82/53 | 28/11 | 46/34 | 8/1 |

| Eugene | 83/51 | 28/10 | 45/34 | 7/1 |

| Bend | 81/46 | 27/8 | 39/22 | 4/–5 |

| Medford | 91/56 | 32/14 | 46/30 | 8/–1 |

| Astoria | 68/53 | 20/11 | 48/36 | 9/2 |

Flora and fauna

Typical of a western state, Oregon is home to a unique and diverse array of wildlife. About 46% of the state is covered in forest, mostly west of the Cascades where up to 80% of the land is forest. Sixty percent of the forests in Oregon are within federal land. Oregon remains the top timber producer of the lower 48 states.[57][58]

- Typical tree species include the Douglas fir, the state tree, as well as redwood, ponderosa pine (generally east of the Cascades), western red cedar, and hemlock.[59] Ponderosa pine are more common in the Blue Mountains in the eastern part of the state and firs are more common in the west.

- There are many species of mammals that live in the state, which include, but are not limited to, opossums, shrews, moles, little pocket mice, great basin pocket mice, dark kangaroo mouse, California kangaroo rat, chisel-toothed kangaroo rat, ord's kangaroo rat,[60] bats, rabbits, pikas, mountain beavers, chipmunks, western gray squirrels, yellow-bellied marmots, beavers, porcupines, coyotes, wolves, red foxes, common grey fox, kit fox,[61] black bears, raccoons, badgers, skunks, cougars, bobcats, lynxes, deer, elk, and moose.

- Marine mammals include seals, sea lions, humpback, killer whales, gray whales, blue whales, sperm whale, pacific whitesided dolphin, and bottlenose dolphin.[62]

- Notable birds include American widgeons, mallard ducks, great blue herons, bald eagles, golden eagles, western meadowlarks (the state bird), barn owls, great horned owls, rufous hummingbirds, pileated woodpeckers, wrens, towhees, sparrows, and buntings.[63]

Moose have not always inhabited the state but came to Oregon in the 1960s; the Wallowa Valley herd now numbers about 60.[64] Gray wolves were extirpated from Oregon around 1930 but have since found their way back; there are now two packs living in the south-central part of the state.[65] Although their existence in Oregon is unconfirmed, reports of grizzly bears still turn up the state and it is probable that some still move into eastern Oregon from Idaho.[66] There are some areas in Oregon where humans find themselves living in the same area as wildlife. This is bound to happen more as the human population grows. When wildlife resources dwindle (food, water and shelter) they will often look for food and shelter in homes and garages.[67]

Oregon has three national park sites: Crater Lake National Park in the southern part of the Cascades, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, and Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks.[68][69]

Governance

A writer in the Oregon Country book A Pacific Republic, written in 1839, predicted the territory was to become an independent republic. Four years later, in 1843, settlers of the Willamette Valley voted in majority for a republic government.[70] The Oregon Country functioned in this way until August 13, 1848, when Oregon was annexed by the United States and a territorial government was established. Oregon maintained a territorial government until February 14, 1859, when it was granted statehood.[71]

State

Oregon state government has a separation of powers similar to the federal government. It has three branches:

- a legislative branch (the bicameral Oregon Legislative Assembly),

- an executive branch which includes an "administrative department" and Oregon's governor serving as chief executive, and

- a judicial branch, headed by the Chief Justice of the Oregon Supreme Court.

Governors in Oregon serve four-year terms and are limited to two consecutive terms, but an unlimited number of total terms. Oregon has no lieutenant governor; in the event that the office of governor is vacated, Article V, Section 8a of the Oregon Constitution specifies that the Secretary of State is first in line for succession.[72] The other statewide officers are Treasurer, Attorney General, Superintendent, and Labor Commissioner. The biennial Oregon Legislative Assembly consists of a thirty-member Senate and a sixty-member House. The state supreme court has seven elected justices, currently including the only two openly gay state supreme court justices in the nation. They choose one of their own to serve a six-year term as Chief Justice. The only court that may reverse or modify a decision of the Oregon Supreme Court is the Supreme Court of the United States.

The debate over whether to move to annual sessions is a long-standing battle in Oregon politics, but the voters have resisted the move from citizen legislators to professional lawmakers. Because Oregon's state budget is written in two-year increments and, having no sales tax, its revenue is based largely on income taxes, it is often significantly over- or under-budget. Recent legislatures have had to be called into special session repeatedly to address revenue shortfalls resulting from economic downturns, bringing to a head the need for more frequent legislative sessions. Oregon Initiative 71, passed in 2010, mandates the Legislature to begin meeting every year, for 160 days in odd-numbered years, and 35 days in even-numbered years.

The state maintains formal relationships with the nine federally recognized tribes in Oregon:

- Burns Paiute Tribe

- Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians

- Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

- Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians

- Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs

- Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation

- Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians

- Klamath Tribes

- Coquille Indian Tribe

Oregonians have voted for the Democratic Presidential candidate in every election since 1988. In 2004 and 2006, Democrats won control of the state Senate and then the House. Since the late 1990s, Oregon has been represented by four Democrats and one Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives. Since 2009, the state has had two Democratic Senators, Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley. Oregon voters have elected Democratic governors in every election since 1986, most recently electing John Kitzhaber over Republican Dennis Richardson in 2014.

The base of Democratic support is largely concentrated in the urban centers of the Willamette Valley. The eastern two-thirds of the state beyond the Cascade Mountains typically votes Republican; in 2000 and 2004, George W. Bush carried every county east of the Cascades. However, the region's sparse population means that the more populous counties in the Willamette Valley usually outweigh the eastern counties in statewide elections.

Oregon's politics are largely similar to those of neighboring Washington – for instance, in the contrast between urban and rural issues.

In the 2002 general election, Oregon voters approved a ballot measure to increase the state minimum wage automatically each year according to inflationary changes, which are measured by the consumer price index (CPI).[73] In the 2004 general election, Oregon voters passed ballot measures banning same-sex marriage,[74] and restricting land use regulation.[75] In the 2006 general election, voters restricted the use of eminent domain and extended the state's discount prescription drug coverage.[76]

The distribution, sales, and consumption of alcoholic beverages are regulated in the state by the Oregon Liquor Control Commission. Thus, Oregon is an Alcoholic beverage control state. While wine and beer are available in most grocery stores, few stores sell hard liquor.

Federal

Like all US states, Oregon is represented by two U.S. Senators. Since the 1980 census, Oregon has had five Congressional districts.

After Oregon was admitted to the Union, it began with a single member in the House of Representatives (La Fayette Grover, who served in the 35th United States Congress for less than a month). Congressional apportionment increased the size of the delegation following the censuses of 1890, 1910, 1940, and 1980. A detailed list of the past and present Congressional delegations from Oregon is available.

The United States District Court for the District of Oregon hears federal cases in the state. The court has courthouses in Portland, Eugene, Medford, and Pendleton. Also in Portland is the federal bankruptcy court, with a second branch in Eugene.[77] Oregon (among other western states and territories) is in the 9th Court of Appeals. One of the court's meeting places is at the Pioneer Courthouse in downtown Portland, a National Historic Landmark built in 1869.

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 39.10% 780,230 | 50.07% 999,103 |

| 2012 | 42.18% 754,095 | 54.27% 970,343 |

| 2008 | 40.40% 738,475 | 56.75% 1,037,291 |

| 2004 | 47.19% 866,831 | 51.35% 943,163 |

| 2000 | 46.46% 713,577 | 47.01% 720,342 |

| 1996 | 39.06% 538,152 | 47.15% 649,641 |

| 1992 | 32.53% 475,757 | 42.48% 621,314 |

| 1988 | 46.61% 560,126 | 51.28% 616,206 |

| 1984 | 55.91% 685,700 | 43.74% 536,479 |

| 1980 | 48.33% 571,044 | 38.67% 456,890 |

| 1976 | 47.78% 492,120 | 47.62% 490,407 |

| 1972 | 52.45% 486,686 | 42.33% 392,760 |

| 1968 | 49.83% 408,433 | 43.78% 358,866 |

| 1964 | 35.96% 282,779 | 63.72% 501,017 |

| 1960 | 52.56% 408,060 | 47.32% 367,402 |

| 1956 | 55.25% 406,393 | 44.75% 329,204 |

| 1952 | 60.54% 420,815 | 38.93% 270,579 |

The state has been thought of as politically split by the Cascade Range, with western Oregon being liberal and Eastern Oregon being conservative. In a 2008 analysis of the 2004 presidential election, a political analyst found that according to the application of a Likert scale, Oregon boasted both the most liberal Kerry voters and the most conservative Bush voters, making it the most politically polarized state in the country.[79]

While Republicans typically win more counties by running up huge margins in the east, the Democratic tilt of the more populated west is usually enough to swing the entire state Democratic. In 2008, for instance, Republican Senate incumbent Gordon H. Smith lost his bid for a third term even though he carried all but six counties. His Democratic challenger, Jeff Merkley, won Multnomah County by 142,000 votes, more than double the overall margin of victory.

During Oregon's history it has adopted many electoral reforms proposed during the Progressive Era, through the efforts of William S. U'Ren and his Direct Legislation League. Under his leadership, the state overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure in 1902 that created the initiative and referendum for citizens to introduce or approve proposed laws or amendments to the state constitution directly, making Oregon the first state to adopt such a system. Today, roughly half of U.S. states do so.[80]

In following years, the primary election to select party candidates was adopted in 1904, and in 1908 the Oregon Constitution was amended to include recall of public officials. More recent amendments include the nation's first doctor-assisted suicide law,[81] called the Death with Dignity Act (which was challenged, unsuccessfully, in 2005 by the Bush administration in a case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court), legalization of medical cannabis, and among the nation's strongest anti-urban sprawl and pro-environment laws. More recently, 2004's Measure 37 reflects a backlash against such land-use laws. However, a further ballot measure in 2007, Measure 49, curtailed many of the provisions of 37.

Of the measures placed on the ballot since 1902, the people have passed 99 of the 288 initiatives and 25 of the 61 referendums on the ballot, though not all of them survived challenges in courts (see Pierce v. Society of Sisters, for an example). During the same period, the legislature has referred 363 measures to the people, of which 206 have passed.

Oregon pioneered the American use of postal voting, beginning with experimentation approved by the Oregon Legislative Assembly in 1981 and culminating with a 1998 ballot measure mandating that all counties conduct elections by mail. It remains the only state, with the exception of Washington, where voting by mail is the only method of voting.[82]

In 1994, Oregon adopted the Oregon Health Plan, which made health care available to most of its citizens without private health insurance.[citation needed]

In the U.S. Electoral College, Oregon casts seven votes. Oregon has supported Democratic candidates in the last seven elections. Democratic incumbent Barack Obama won the state by a margin of twelve percentage points, with over 54% of the popular vote in 2012.

Crime

According to 2015 data, there were a total of 123,529 reported crimes in the state of Oregon; 9,224 of these were violent crimes, while 114,305 were classified as property crimes.[83] Of the violent crimes, there were approximately 81 murders, 1,458 cases of rape, 2,093 cases of robbery, and 5,592 cases of assault.[83]

Per 1,000 residents, Oregon's violent crime rate was 2.32, below the national median of 3.8.[83] At 28.79, property crime rates were slightly higher than the national average of 26.[83]

Economy

The gross domestic product (GDP) of Oregon in 2013 was $219.6 billion, a 2.7% increase from 2012; Oregon is the 25th wealthiest state by GDP. In 2003, Oregon was 28th in the U.S. by GDP. The state's per capita personal income (PCPI) in 2013 was $39,848, a 1.5% increase from 2012. Oregon ranks 33rd in the U.S. by PCPI, compared to 31st in 2003. The national PCPI in 2013 was $44,765.[84]

Oregon's unemployment rate was 5.5% in September 2016,[85] while the U.S. unemployment rate was 5.0% that month.[86] Oregon has the third largest amount of food stamp users in the nation (21% of the population).[87]

Agriculture

Oregon's diverse landscapes provide ideal environments for various types of farming. Land in the Willamette Valley owes its fertility to the Missoula Floods, which deposited lake sediment from Glacial Lake Missoula in western Montana onto the valley floor.[88] In 2016, the Willamette Valley region produced over 100 million pounds (45 kt) of blueberries.[89]

Oregon is also one of four major world hazelnut growing regions, and produces 95% of the domestic hazelnuts in the United States. While the history of the wine production in Oregon can be traced to before Prohibition, it became a significant industry beginning in the 1970s. In 2005, Oregon ranked third among U.S. states with 303 wineries.[90] Due to regional similarities in climate and soil, the grapes planted in Oregon are often the same varieties found in the French regions of Alsace and Burgundy. In 2014, 71 wineries opened in the state. The total is currently 676, which represents growth of 12% over 2013.[91]

In the Southern Oregon coast commercially cultivated cranberries account for about 7 percent of US production, and the cranberry ranks 23rd among Oregon's top 50 agricultural commodities. Cranberry cultivation in Oregon uses about 27,000 acres (110 km2) in southern Coos and northern Curry counties, centered around the coastal city of Bandon.

In the northeastern region of the state, particularly around Pendleton, both irrigated and dry land wheat is grown.[92] Oregon farmers and ranchers also produce cattle, sheep, dairy products, eggs and poultry.

Forestry and fisheries

Vast forests have historically made Oregon one of the nation's major timber production and logging states, but forest fires (such as the Tillamook Burn), over-harvesting, and lawsuits over the proper management of the extensive federal forest holdings have reduced the timber produced. Between 1989 and 2011, the amount of timber harvested from federal lands in Oregon dropped about 90%, although harvest levels on private land have remained relatively constant.[93]

Even the shift in recent years towards finished goods such as paper and building materials has not slowed the decline of the timber industry in the state. The effects of this decline have included Weyerhaeuser's acquisition of Portland-based Willamette Industries in January 2002, the relocation of Louisiana-Pacific's corporate headquarters from Portland to Nashville, and the decline of former lumber company towns such as Gilchrist. Despite these changes, Oregon still leads the United States in softwood lumber production; in 2011, 4,134 million board feet (9,760,000 m3) was produced in Oregon, compared with 3,685 million board feet (8,700,000 m3) in Washington, 1,914 million board feet (4,520,000 m3) in Georgia, and 1,708 million board feet (4,030,000 m3) in Mississippi.[94] The slowing of the timber and lumber industry has caused high unemployment rates in rural areas.[95]

Oregon has one of the largest salmon-fishing industries in the world, although ocean fisheries have reduced the river fisheries in recent years.[96] See also the List of freshwater fishes of Oregon.

Tourism and entertainment

Tourism is also a strong industry in the state. Much of this is centered on the state's natural features; Oregon's mountains, forests, waterfalls, rivers, beaches and lakes, including Crater Lake National Park, Multnomah Falls, the Painted Hills, the Deschutes River, the Oregon Caves National Monument and Preserve, Mount Hood, and Mount Bachelor draw visitors year round.[97]

Portland is home to the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry, the Portland Art Museum, and the Oregon Zoo. Portland has also been named the best city in the world for street food by several publications, including the U.S. News & World Report and CNN.[98][99] Oregon is home to many breweries and Portland has the largest number of breweries of any city in the world.[100]

In Southern Oregon, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, held in Ashland, is also a tourist draw, as is the Oregon Vortex and the Wolf Creek Inn State Heritage Site, an historic inn where Jack London wrote his 1913 novel Valley of the Moon.[101]

Oregon has also historically been a popular region for film shoots due to its diverse landscapes, as well as its proximity to Hollywood (see List of films shot in Oregon).[102] Movies filmed in Oregon include: Animal House, Free Willy, The General, The Goonies, Kindergarten Cop, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and Stand By Me. Oregon native Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons, has incorporated many references from his hometown of Portland into the TV series.[103] The Oregon Film Museum is located in the old Clatsop County Jail in Astoria.

Technology

High technology industries located in Silicon Forest have been a major employer since the 1970s. Tektronix was the largest private employer in Oregon until the late 1980s. Intel's creation and expansion of several facilities in eastern Washington County continued the growth that Tektronix had started. Intel, the state's largest for-profit private employer,[104][105] operates four large facilities, with Ronler Acres, Jones Farm and Hawthorn Farm all located in Hillsboro.[106]

The spinoffs and startups that were produced by these two companies led to the establishment in that area of the so-called Silicon Forest. The recession and dot-com bust of 2001 hit the region hard; many high technology employers reduced the number of their employees or went out of business. Open Source Development Labs made news in 2004 when they hired Linus Torvalds, developer of the Linux kernel. In 2010, biotechnology giant Genentech opened a $400-million facility in Hillsboro to expand its production capabilities.[107] Oregon is home to several large datacenters that take advantage of cheap power and a climate in Central Oregon conducive to reducing cooling costs. Google has a large datacenter in The Dalles and Facebook has built a large datacenter in Prineville. In 2011, Amazon began operating a datacenter in northeastern Oregon near Boardman.[108]

Corporate headquarters

| Corporation | Headquarters | Market cap |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Nike | Beaverton | $32,039,000 |

| 2. Precision Castparts Corp. | Portland | $16,158,000 |

| 3. FLIR Systems | Wilsonville | $4,250,000 |

| 4. StanCorp Financial Group | Portland | $2,495,000 |

| 5. Schnitzer Steel Industries | Portland | $1,974,000 |

| 6. Portland General Electric | Portland | $1,737,000 |

| 7. Columbia Sportswear | near Beaverton | $1,593,000 |

| 8. Northwest Natural Gas | Portland | $1,287,000 |

| 9. Mentor Graphics | Wilsonville | $976,000 |

| 10. TriQuint Semiconductor | Hillsboro | $938,000 |

Oregon is also the home of large corporations in other industries. The world headquarters of Nike are located near Beaverton. Medford is home to Harry and David, which sells gift items under several brands. Medford is also home to the national headquarters of Lithia Motors. Portland is home to one of the West's largest trade book publishing houses, Graphic Arts Center Publishing. Oregon is also home to Mentor Graphics Corporation, a world leader in electronic design automation located in Wilsonville and employs roughly 4,500 people worldwide.

Adidas Corporations American Headquarters is located in Portland and employs roughly 900 full-time workers at its Portland campus. Adidas competes with Beaverton based Nike as "the other sports giant in town".[110]

Nike, located just outside Portland in nearby Beaverton employs roughly 5,000 full-time employees at its 200-acre (81 ha) campus. Nike's Beaverton campus is continuously ranked as a top employer in the Portland area-along with competitor Adidas.[111] Intel Corporation employs 18,600 in Oregon[105] with the majority of these employees located at the company's Hillsboro campus located about 30 minutes west of Portland. Intel has been a top employer in Oregon since 1974.[112]

The U.S. Federal Government and Providence Health systems are respective contenders for top employers in Oregon with roughly 12,000 federal workers and 14,000 Providence Health workers.

In 2015, a total of 7 companies headquartered in Oregon landed in the Fortune 1000: Nike, at 106; Precision Castparts Corp. at 302; Lithia Motors at 482; StanCorp Financial Group at 804; Schnitzer Steel Industries at 853; The Greenbrier Companies at 948; and Columbia Sportswear at 982.[113]

Employment

As of December 2014, the state's official unemployment rate was 5.5%.[114] Oregon's largest for-profit employer is Intel,[105] located in the Silicon Forest area on Portland's west side. Intel was the largest employer in Oregon until 2008. As of January 2009, the largest employer in Oregon is Providence Health & Services, a non-profit.[115]

Nike and Adidas also have their North American headquarters in the Portland area.

Taxes and budgets

Oregon's biennial state budget, $42.4 billion as of 2007, comprises General Funds, Federal Funds, Lottery Funds, and Other Funds. Personal income taxes account for 88% of the General Fund's projected funds.[116] The Lottery Fund, which has grown steadily since the lottery was approved in 1984, exceeded expectations in the 2007 fiscal years, at $604 million.[117]

Oregon is one of only five states that have no sales tax.[118] Oregon voters have been resolute in their opposition to a sales tax, voting proposals down each of the nine times they have been presented.[119] The last vote, for 1993's Measure 1, was defeated by a 75–25% margin.[120]

The state also has a minimum corporate tax of only $10 a year, amounting to 5.6% of the General Fund in the 2005–7 biennium; data about which businesses pay the minimum is not available to the public.[121] As a result, the state relies on property and income taxes for its revenue. Oregon has the fifth highest personal income tax in the nation. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Oregon ranked 41st out of the 50 states in taxes per capita in 2005 with an average amount paid of 1,791.45.[122]

A few local governments levy sales taxes on services: the city of Ashland, for example, collects a 5% sales tax on prepared food.[123]

The City of Portland requires residents over 18 to file and pay an Arts tax—a flat fee of $35 collected from individuals earning $1,000 or more per year and residing in a household with an annual income exceeding the federal poverty level. Only one form needs to be filed per household, but the form must list the total number of individuals (the $35 tax applies to each person). Exempted individuals and households are also required to file to qualify for the exemption.[124]

The State of Oregon also allows transit district to levy an income tax on employers and the self-employed. The State currently collects the tax for TriMet and the Lane Transit District.[125][126]

Oregon is one of six states with a revenue limit.[127] The "kicker law" stipulates that when income tax collections exceed state economists' estimates by 2% or more, any excess must be returned to taxpayers.[128] Since the enactment of the law in 1979, refunds have been issued for seven of the eleven biennia.[129] In 2000, Ballot Measure 86 converted the "kicker" law from statute to the Oregon Constitution, and changed some of its provisions.

Federal payments to county governments, which were granted to replace timber revenue when logging in National Forests was restricted in the 1990s, have been under threat of suspension for several years. This issue dominates the future revenue of rural counties, which have come to rely on the payments in providing essential services.[130]

Fifty-five percent of state revenues are spent on public education, 23% on human services (child protective services, Medicaid, and senior services), 17% on public safety, and 5% on other services.[131]

Demographics

Population

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 12,093 | — | |

| 1860 | 52,465 | 333.8% | |

| 1870 | 90,923 | 73.3% | |

| 1880 | 174,768 | 92.2% | |

| 1890 | 317,704 | 81.8% | |

| 1900 | 413,536 | 30.2% | |

| 1910 | 672,765 | 62.7% | |

| 1920 | 783,389 | 16.4% | |

| 1930 | 953,786 | 21.8% | |

| 1940 | 1,089,684 | 14.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,521,341 | 39.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,768,687 | 16.3% | |

| 1970 | 2,091,533 | 18.3% | |

| 1980 | 2,633,156 | 25.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,842,321 | 7.9% | |

| 2000 | 3,421,399 | 20.4% | |

| 2010 | 3,831,074 | 12.0% | |

| 2015 (est.) | 4,028,977 | 5.2% | |

| Sources: 1910–2010[133] 2015 estimate[1] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Oregon was 4,028,977 on July 1, 2015, a 5.17% increase over the 2010 United States Census.[1]

Oregon was the U.S.'s "Top Moving Destination" in 2014 with two families moving into the state for every one moving out of state (66.4% to 33.6%).[135] Oregon was also the top moving destination in 2013,[136] and second most popular destination in 2010 through 2012.[137][138]

As of the census of 2010,[139] Oregon had a population of 3,831,074, which is an increase of 409,675, or 12%, since the year 2000. The population density was 39.9 inhabitants per square mile (15.4/km2). There were 1,675,562 housing units, a 15.3% increase over 2000. Among them, 90.7% were occupied.

In 2010, 78.5% of the population was white alone (meaning of no other race and non-Hispanic), 1.7% was black or African American alone, 1.1% was Native American or Alaska native alone, 3.6% was Asian alone, 0.3% was Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander alone, 0.1% was another race alone, and 2.9% was multiracial. Hispanics or Latinos made up 11.7% of the total population.

| Racial composition | 1970[140] | 1990[140] | 2000[141] | 2010[142] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 97.2% | 92.8% | 86.6% | 83.6% |

| Asian | 0.7% | 2.4% | 3.0% | 3.7% |

| Black | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.6% | 1.8% |

| Native | 0.6% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

– | – | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Other race | 0.2% | 1.8% | 4.2% | 5.3% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 3.1% | 3.8% |

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 95.8% in 1970 to 77.8% in 2012.[143][144]

As of 2011, 38.7% of Oregon's children under one year of age belonged to minority groups, meaning they had at least one parent who was not a non-Hispanic white.[145] Of the state's total population, 22.6% was under the age 18, and 77.4% were 18 or older.

The center of population of Oregon is located in Linn County, in the city of Lyons.[146] More than 46% of the state's population lives in the Oregon portion of the Portland metropolitan area.[147]

As of 2004, Oregon's population included 309,700 foreign-born residents (accounting for 8.7% of the state population).

The largest ancestry groups in the state are:[148]

- 22.5% German

- 14.0% English

- 13.2% Irish

- 8.4% Scandinavian: (4.1% Norwegian American, 3.1% Swedish, & 1.2% Danish)

- 5.0% American

- 3.9% French

- 3.7% Italian

- 3.6% Scottish

- 2.7% Scots-Irish

- 2.6% Dutch

- 1.9% Polish

- 1.4% Russian

- 1.1% Welsh

The largest reported ancestry groups in Oregon are: German (22.5%), English (14.0%), Irish (13.2%), Scandinavian (8.4%) and American (5.0%). Approximately 62% of Oregon residents are wholly or partly of English, Welsh, Irish or Scottish ancestry. Most Oregon counties are inhabited principally by residents of Northwestern-European ancestry. Concentrations of Mexican-Americans are highest in Malheur and Jefferson counties. But despite the fact that Russians account for only 1.4% of the population, Russian is the third most spoken language in Oregon after English and Spanish.[149]

Future projections

Projections from the U.S. Census Bureau show Oregon's population increasing to 4,833,918 by 2030, an increase of 41.3% compared to the state's population of 3,421,399 in 2000.[150] The state's own projections forecast a total population of 5,425,408 in 2040.[151]

Religious and secular communities

| Affiliation | % of Oregon population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 61 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 29 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 13 | |

| Catholic | 12 | |

| Mormon | 4 | |

| Black Protestant | 1 | |

| Orthodox | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 0.5 | |

| Other Christianity | 1 | |

| Judaism | 2 | |

| Islam | 1 | |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | |

| Hinduism | 0.5 | |

| Other Faiths | 4 | |

| Unaffiliated | 31 | |

| Don't Know/No Answer | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

The largest denominations by number of adherents in 2010 were the Roman Catholic Church with 398,738; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 147,965; and the Assemblies of God with 45,492.[153]

In a 2009 Gallup poll, 69% of Oregonians identified themselves as being Christian.[154] Most of the remainder of the population had no religious affiliation; the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) placed Oregon as tied with Nevada in fifth place of U.S. states having the highest percentage of residents identifying themselves as "non-religious", at 24 percent.[155][156] Secular organizations include the Center for Inquiry (CFI), the Humanists of Greater Portland (HGP), and the United States Atheists (USA).

During much of the 1990s, a group of conservative Christians formed the Oregon Citizens Alliance, and unsuccessfully tried to pass legislation to prevent "gay sensitivity training" in public schools and legal benefits for homosexual couples.[157]

Oregon also contains the largest community of Russian Old Believers to be found in the United States.[158] The Northwest Tibetan Cultural Association is headquartered in Portland. There are an estimated 6,000 to 10,000 Muslims in Oregon, most of whom live in and around Portland.[159] The New Age film What the Bleep Do We Know!? was filmed and had its premiere in Portland.

Education

Primary and secondary

In the 2013–2014 school year, the state had 567,000 students in public primary and secondary schools.[160] There were 197 public school districts, served by 19 education service districts.[160]

In 2016, the largest school districts in the state were:[161] Portland Public Schools, comprising 47,323 students; Salem-Keizer School District, comprising 40,565 students; Beaverton School District, comprising 39,625 students; Hillsboro School District, comprising 21,118 students; and North Clackamas School District, comprising 17,053 students.

Colleges and universities

Public

Oregon supports seven public universities and one affiliate in the state. It is home to three public research universities: The University of Oregon (UO) in Eugene and Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis, both classified as research universities with very high research activity, and Portland State University which is classified as a research university with high research activity.[162]

UO is the state's most selective university by percentage of students admitted[163] and highest nationally ranked university by U.S. News & World Report and Forbes.[164] OSU is the state's only land-grant university, has the state's largest enrollment for fall 2014,[165] and is the state's highest ranking university according to Academic Ranking of World Universities, Washington Monthly, and QS World University Rankings.[166] OSU receives more annual funding for research than all other public higher education institutions in Oregon combined.[167] The state's urban Portland State University has Oregon's second largest enrollment.

The state has three regional universities: Western Oregon University in Monmouth, Southern Oregon University in Ashland, and Eastern Oregon University in La Grande. The Oregon Institute of Technology has its campus in Klamath Falls. The quasi-public Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) includes medical, dental, and nursing schools, and graduate programs in biomedical sciences in Portland and a science and engineering school in Hillsboro. It rated 2nd among US best medical schools for primary care based on research by The Med School 100.[168]

Especially since the 1990 passage of Measure 5, which set limits on property tax levels, Oregon has struggled to fund higher education. Since then, Oregon has cut its higher education budget and now ranks 46th in the country in state spending per student. However, 2007 legislation forced tuition increases to cap at 3% per year, and funded the university system far beyond the governor's requested budget.[169]

The state also supports 17 community colleges.

Private

Oregon is home to a wide variety of private colleges, the majority of which are located in the Portland area. The University of Portland and Marylhurst University are both Catholic universities located in or near Portland, affiliated with the Congregation of Holy Cross, and the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, respectively. Reed College, a rigorous liberal arts college in Portland, was ranked by Forbes as the 52nd best college in the country in 2015.[170]

Other private institutions in Portland include Concordia University; Lewis & Clark College; Multnomah University; Portland Bible College; Warner Pacific College; Cascade College; the National University of Natural Medicine; and Western Seminary, a theological graduate school. Pacific University is in the Portland suburb of Forest Grove.

There are also private colleges further south in the Willamette Valley. McMinnville is home to Linfield College, while nearby Newberg is home to George Fox University. Salem is home to two private schools: Willamette University (the state's oldest, established during the provisional period) and Corban University. Also located near Salem is Mount Angel Seminary, one of America's largest Roman Catholic seminaries. The state's second medical school, the College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific, Northwest, is located in Lebanon. Eugene is home to three private colleges: Northwest Christian University, New Hope Christian College, and Gutenberg College.

Sports

Oregon is home to three major professional sports teams: the Portland Trail Blazers of the NBA, the Portland Thorns of the NWSL and the Portland Timbers of MLS.[171]

Until 2011, the only major professional sports team in Oregon was the Portland Trail Blazers of the National Basketball Association. From the 1970s to the 1990s, the Blazers were one of the most successful teams in the NBA in terms of both win-loss record and attendance.[citation needed] In the early 21st century, the team's popularity declined due to personnel and financial issues, but revived after the departure of controversial players and the acquisition of new players such as Brandon Roy, LaMarcus Aldridge, and Damian Lillard.[172][173] The Blazers play in the Moda Center in Portland's Lloyd District, which also is home to the Portland Winterhawks of the junior Western Hockey League.[174]

The Portland Timbers play at Providence Park, just west of downtown Portland. The Timbers have a strong following, with the team regularly selling out its games.[175] The Timbers repurposed the formerly multi-use stadium into a soccer-specific stadium in fall 2010, increasing the seating in the process.[176] The Timbers operate Portland Thorns FC, a women's soccer team that has played in the National Women's Soccer League since the league's first season in 2013. The Thorns, who also play at Providence Park, won the league's first championship, and have been by far the NWSL's attendance leader in all three of its seasons to date.

Eugene, Salem and Hillsboro have minor-league baseball teams. The Eugene Emeralds the Salem-Keizer Volcanoes and the Hillsboro Hops all play in the Single-A Northwest League.[177] Portland has had minor-league baseball teams in the past, including the Portland Beavers and Portland Rockies, who played most recently at Providence Park when it was known as PGE Park.

Oregon also has four teams in the fledgling International Basketball League: the Portland Chinooks, Central Oregon Hotshots, Salem Stampede, and the Eugene Chargers.[178]

The Oregon State Beavers and the University of Oregon Ducks football teams of the Pac-12 Conference meet annually in the Civil War. Both schools have had recent success in other sports as well: Oregon State won back-to-back college baseball championships in 2006 and 2007,[179] and the University of Oregon won back-to-back NCAA men's cross country championships in 2007 and 2008.[180]

Sister regions

People's Republic of China, Fujian Province – 1984[181]

People's Republic of China, Fujian Province – 1984[181] Republic of China (Taiwan), Taiwan Province – 1985[181]

Republic of China (Taiwan), Taiwan Province – 1985[181] Japan, Toyama Prefecture – 1991[181][182]

Japan, Toyama Prefecture – 1991[181][182] Republic of Korea (South Korea), Jeollanam-do Province – 1996[181][182]

Republic of Korea (South Korea), Jeollanam-do Province – 1996[181][182] Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan – 2005[183]

Iraq, Iraqi Kurdistan – 2005[183]

See also

- Outline of Oregon – organized list of topics about Oregon

- Index of Oregon-related articles

- List of companies based in Oregon

- List of Oregon state symbols

- List of people from Oregon

- List of films shot in Oregon

References

- ^ a b c "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015" (CSV). U.S. Census Bureau. December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Hall, Calvin (January 30, 2007). "English as Oregon's official language? It could happen". The Oregon Daily Emerald. Retrieved May 8, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Mount Hood Highest Point". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ a b "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ^ a b "Oregon Fast Facts". Travel Oregon. Archived from the original on March 23, 2012.

- ^ Map of Oregon (PDF). Reston, Virginia: Interior Geological Survey, 2004

- ^ Motezuma, Rodrigo (2002). La isla de oro: relación de la alta y Baja California (1. ed.). Valladolid: Universitas Castellae. ISBN 84-92315-67-9.

- ^ Fernández-Shaw, Carlos M. (1987). Presencia española en los Estados Unidos (2a ed. aum. y corr. ed.). Madrid: Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamericana, Ediciones Cultura Hispánica. ISBN 84-7232-412-5.

- ^ Oregon Almanac

- ^ Where does the name "Oregon" come from? from the online edition of the Oregon Blue Book.

- ^ Elliott, T.C. (June 1921). "The Origin of the Name Oregon". Oregon Historical Quarterly. XXIII (2). Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society: 99–100. ISSN 0030-4727. OCLC 1714620. Retrieved October 11, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Joaquin (1904). "The Sea of Silence", Sunset, 396(13):5.

- ^ "Oregon". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Retrieved September 14, 2006.

- ^ Banks, Don (April 21, 2002). "Harrington confident about Detroit QB challenge." Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Bellamy, Ron (October 6, 2003). "See no evil, hear no evil". The Register-Guard. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ "Yellow/Green ORYGUN Block Letter Outside Decal". UO Duck Store. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ Robbins 2005.

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (July 12, 2012). "Who was first? New info on North America's earliest residents". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Burns & Sargent 2009, pp. 175–189.

- ^ "Oregon History: Great Basin". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ "Oregon History: Northwest Coast". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ "Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde: Culture". Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ "Oregon History: Columbia Plateau". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- ^ Atlas of Exploration, foreword by John Hemming, Oxford University Press, pp. 140–141

- ^ "Francis Drake's 1579 symbolic Sovereign Act of Possession on Neahkahnie Mountain, Oregon". Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ "Chronology of events, 1543–1859". Echoes of Oregon History Learning Guide. Oregon State Archives. Retrieved May 20, 2015.

- ^ Ambrose 1997, p. 326.

- ^ Loy et al. 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ^ William S. Savage, "The Negro in the Westward Movement", The Journal of Negro History 25, no. 4, (October 1, 1940), 532

- ^ Thomas C. McClintock, "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844," The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, no. 3 (July 1, 1995), 122.

- ^ Elizabeth McLagan, A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940, (Portland: Georgian Press, 1980), 24

- ^ Gregory R. Nokes, Breaking Chains: Slavery on Trial in the Oregon Territory, (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2013), 74-75.

- ^ Barbara Mahoney, "Oregon Voices: Oregon Democracy: Asahel Bush, Slavery, and the Statehood Debate," Oregon Historical Quarterly 110, no. 2 (July 1, 2009), 202.

- ^ McLagan, Elizabeth (1980). A Peculiar Paradise. Georgian Press. ISBN 0-9603408-2-3.

- ^ Engeman, Richard H. (2005). "Architectural Fashions and Industrial Pragmatism, 1865-1900". The Oregon History Project. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ "From Robin's Nest to Stumptown". End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center. February 1, 2013. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved March 7, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kennedy, Sarah. "The Shanghai Tunnels". The New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2014.

- ^ On This Day: Japanese WWII Balloon Bomb Kills 6 in Oregon

- ^ http://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/fremont-winema/recarea/?recid=59797

- ^ Toll, William (2003). "Home Front Boom". Oregon Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Taylor, Alan (July 26, 2013). "America in the 1970s: The Pacific Northwest". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density (geographies ranked by total population). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". U.S Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on October 15, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Crater Lake National Park". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved November 22, 2006.

- ^ "D River State Recreation Site". Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ "World's Shortest River". Travel Montana. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ "Mill Ends Park". Portland Parks and Recreation. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

- ^ Beale, Bob (April 10, 2003). "Humungous fungus: world's largest organism?" Environment & Nature News, ABC Online. Accessed January 2, 2007.

- ^ Western States Data Public Land Acreage (November 13, 2007).

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- ^ "2010 Census Redistricting Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 15, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 50 Fastest-Growing Metro Areas Concentrated in West and South. U.S. Census Bureau 2005. Retrieved October 16, 2007.

- ^ Conlon T.D.; Wozniak, K.C.; Woodcock, D.; Herrera, N.B.; Fisher, B.J.; Morgan, D.S.; Lee, K.K.; Hinkle, S.R. (2005). "Ground-Water Hydrology of the Willamette Basin, Oregon". Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5168. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Boone 2004, p. 9.

- ^ "Maine climate averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Forest Land Protection Program". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Oregon is top timber producer in worst year". Mail Tribune. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Trees of Oregon's forests". Tree Variety.

- ^ "Mammals: Pocket Mice, Kangaroo Rats and Kangaroo Mouse". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Oregon Wildlife Species. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Mammals: Coyotes, wolves and foxes". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Oregon Wildlife Species. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Mammals: Whale, dolphin and porpoise". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Oregon Wildlife Species. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Oregon Wildlife Species". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- ^ "Oregon's only moose herd thriving, up to about 60". The Oregonian. Retrieved September 1, 2013.

- ^ "Wolves in Oregon". ODFW. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Moose enter Oregon, so are grizzlies next?". Tri City Herald. Retrieved November 1, 2008.

- ^ "Living with Wildlife".

- ^ "Crater Lake National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "John Day Fossil Beds National Monument". National Park Service. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Allen, Cain (2006). "A Pacific Republic". The Oregon History Project. Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ Oregon Secretary of State. "A Brief History of the Oregon Territorial Period". State of Oregon. Retrieved August 9, 2006.

- ^ "Constitution of Oregon (Article V)". Oregon Blue Book. State of Oregon. 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ ORS 653.025.

- ^ "November 2, 2004, General Election Abstract of Votes: STATE MEASURE NO. 36" (PDF). Oregon Secretary of State. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ Bradbury, Bill (November 6, 2007). "Official Results – November 6, 2007 Special Election". Elections Division. Oregon Secretary of State. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ^ "November 7, 2006, general election abstracts of votes: state measure no. 39" (PDF). State of Oregon. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "United States Bankruptcy Court, District of Oregon". U.S. Courts. Retrieved December 14, 2008.

- ^ Leip, David. "2008 presidential general election results". Retrieved October 12, 2010.

- ^ Silver, Nate (May 17, 2008). "Oregon: Swing state or latte-drinking, Prius-driving lesbian commune?". FiveThirtyEight.com.

- ^ "State Initiative and Referendum Summary". State Initiative & Referendum Institute at USC. Retrieved November 27, 2006.

- ^ "Eighth Annual Report on Oregon's Death with Dignity Act" (PDF). Oregon Department of Human Services. March 9, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ^ "Voting In Oregon – Vote By Mail." Multnomah County, Oregon.

- ^ a b c d "Oregon crime rates and statistics". Neighborhood Scout. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ^ "BEARFACTS: Oregon". Bureau of Economic Analysis. 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ "School hiring fuels Oregon job growth in September". Associated Press. October 18, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ "Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ^ Real Time Economics The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ^ McNab, W. Henry; Avers, Peter E (July 1994). Ecological Subregions of the United States. Chapter 24. U.S. Forest Service and Dept. of Agriculture.

- ^ Hogen, Junnelle (September 11, 2016). "Oregon blueberry yield topples records, expands overseas". Statesman Journal. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ "Industry Facts" (PDF). Oregon Winegrowers Association. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- ^ Keates, Nancy (October 15, 2015). "Oregon Vineyards Draw Out-of-State Buyers". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ Weaver, Matthew (July 1, 2014). "Oregon farmers kick off wheat harvest". Capital Press. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Oregon Forest Facts & Figures 2013" (PDF). Oregon Forest Resources Institute. p. 3. Retrieved May 31, 2014.

- ^ "Oregon Forest Facts & Figures 2013", p. 12

- ^ "Oregon Economy". e-ReferenceDesk. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "Salmon and Steelhead Fishing". Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ Richard, Terry (March 1, 2015). "7 Wonders of Oregon begin second Travel Oregon ad campaign season on TV, at movies". The Oregonian. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "World's Best Street Food". U.S. News.

- ^ "World's Best Street Food". CNN Travel. July 19, 2010.

- ^ "Oregon's Beer Week gets under way". Knight-Ridder Tribune News Service. July 5, 2005. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ^ John, Finn J.D. (April 4, 2010). "Wolf Creek Inn was writing retreat for Jack London". Offbeat Oregon. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Filmed in Oregon 1908-2015" (PDF). Oregon Film Council. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ Hamilton, Don (July 19, 2002). "Matt Groening's Portland". The Portland Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Rogoway, Mike (July 17, 2013). "Intel offers downbeat outlook as PC sales slump". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c Rogoway, Mike (August 8, 2015). "Intel layoffs: Employees say chipmaker changed the rules, undermining 'meritocracy'". The Oregonian. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- ^ Rogoway, Mike (January 15, 2009). "Intel profits slide, company uncertain about outlook". The Oregonian. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ Rogoway, Mike (April 5, 2010). "Genentech opens in Hillsboro, fueling Oregon's biotech aspirations". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ Rogoway, Mike (November 9, 2011). "Amazon confirms its data center near Boardman has begun operating". The Oregonian. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- ^ "Bright spots amid the turmoil". The Oregonian. January 1, 2008. p. D3. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- ^ "Careers". Adidas.

- ^ "Locations". Nike.

- ^ "Intel in Oregon". Corporate Responsibility. Intel.

- ^ Walker, Mason (June 4, 2015). "Oregon lands 7 companies on Fortune 1000, up from 5 last year". Portland Business Journal. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Unemployment Rates for States". January 27, 2015.

- ^ Rogoway, Mike (January 12, 2009). "Oregon's largest private employer". The Oregonian. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Government Finance: State Government". Oregon Blue Book. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ Har, Janie (June 20, 2007). "Your loss is state's record game". The Oregonian. Retrieved June 20, 2007.

- ^ "State Sales Tax Rates". Federation of Tax Administrators. January 1, 2008. Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- ^ "25th Anniversary Issue". Willamette Week. 1993. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ^ "Initiative, Referendum and Recall: 1988–1995". Oregon Blue Book. State of Oregon. Retrieved June 11, 2007.