SARS-CoV-2

Template:Use Commonwealth English

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 | |

|---|---|

| |

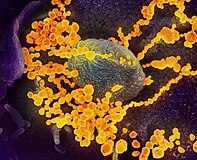

| Electron micrograph of SARS-CoV-2 virions with visible coronae | |

| |

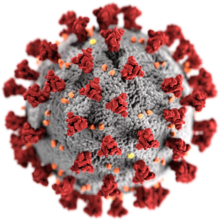

| Illustration of a SARS-CoV-2 virion | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Subgenus: | Sarbecovirus |

| Species: | |

| Strain: | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

|

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2),[1][2] previously known by the provisional name 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV),[3][4][5] is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus.[6][7] It is contagious in humans and is the cause of the ongoing 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic, a pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) that has been designated a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the World Health Organization (WHO).[8][9]

SARS-CoV-2 has close genetic similarity to bat coronaviruses, from which it likely originated.[10][11][12] An intermediate reservoir such as a pangolin is also thought to be involved in its introduction to humans.[13][14] From a taxonomic perspective SARS-CoV-2 is classified as a strain of the species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV).[1] To avoid confusion with the disease SARS, the WHO sometimes refers to the virus as "the virus responsible for COVID-19" in public health communications.[15]

Virology

Infection

Human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has been confirmed during the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[9] Transmission occurs primarily via respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes within a range of about 6 feet (1.8 m).[16][17] Indirect contact via contaminated surfaces is another possible cause of infection.[18] Viral RNA has also been found in stool samples from infected patients.[19]

It is possible that the virus can be infectious even during the incubation period, but this has not been proven,[20] and the World Health Organization (WHO) stated on 1 February 2020 that "transmission from asymptomatic cases is likely not a major driver of transmission" at this time.[21] Thus, most infections in humans are believed to be the result of transmission from subjects exhibiting symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019.

Reservoir

The first known infections from the SARS-CoV-2 strain were discovered in Wuhan, China.[10] The original source of viral transmission to humans remains unclear.[22][23][24] However, research into the origin of the 2003 SARS outbreak has resulted in the discovery of many SARS-like bat coronaviruses, most originating in the Rhinolophus genus of horseshoe bats. Two viral nucleic acid sequences found in samples taken from Rhinolophus sinicus show a resemblance of 80% to SARS-CoV-2.[12][25][26] A third viral nucleic acid sequence from Rhinolophus affinis collected in Yunnan province has a 96% resemblance to SARS-CoV-2.[10][27] The WHO considers bats the most likely natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-2.[28]

A metagenomic study published in 2019 previously revealed that SARS-CoV, the strain of the virus that causes SARS, was the most widely distributed coronavirus among a sample of Sunda pangolins.[29] On 7 February 2020, it was announced that researchers from Guangzhou had discovered a pangolin sample with a viral nucleic acid sequence "99% identical" to SARS-CoV-2.[30] When released, the results clarified that "the receptor-binding domain of the S protein of the newly discovered Pangolin-CoV is virtually identical to that of 2019-nCoV, with one amino acid difference."[31] Pangolins are protected under Chinese law, but their poaching and trading for use in traditional Chinese medicine remains common.[32]

Microbiologists and geneticists in Texas have independently found evidence of reassortment in coronaviruses suggesting the involvement of pangolins in the origin of SARS-CoV-2.[33] They acknowledged remaining unknown factors while urging continued examination of other mammals.[33]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

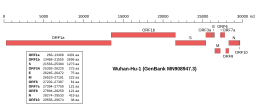

Genomic organisation of isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, the earliest sequenced sample of SARS-CoV-2 | |

| NCBI genome ID | MN908947 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses. It is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus. Other coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and the original SARS-CoV.[34]

Like the SARS-related coronavirus strain implicated in the 2003 SARS outbreak, SARS-CoV-2 is a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (beta-CoV lineage B).[35][36][37] Its RNA sequence is approximately 30,000 bases in length.[7] SARS-CoV-2 is unique among known betacoronaviruses in its incorporation of a polybasic cleavage site, a characteristic known to increase pathogenicity and transmissibility in other viruses.[38][39][40]

With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. By 12 January 2020, five genomes of SARS-CoV-2 had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) and other institutions;[7][41] the number of genomes increased to 81 by 11 February 2020.[42] A phylogenetic analysis of those samples showed they were "highly related with at most seven mutations relative to a common ancestor", implying that the first human infection occurred in November or December 2019.[42]

On 11 February 2020, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) announced that according to existing rules that compute hierarchical relationships among coronaviruses on the basis of five conserved sequences of nucleic acids, the differences between what was then called 2019-nCoV and the virus strain from the 2003 SARS outbreak were insufficient to make it a separate viral species. Therefore, they identified 2019-nCoV as a strain of severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus.[1]

Structural biology

Each SARS-CoV-2 virion is approximately 50–200 nanometres in diameter.[43] Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 has four structural proteins, known as the S (spike), E (envelope), M (membrane), and N (nucleocapsid) proteins; the N protein holds the RNA genome, and the S, E, and M proteins together create the viral envelope.[44] The spike protein is responsible for allowing the virus to attach to the membrane of a host cell.[44]

Protein modeling experiments on the spike protein of the virus soon suggested that SARS-CoV-2 has sufficient affinity to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors of human cells to use them as a mechanism of cell entry.[45] By 22 January 2020, a group in China working with the full virus genome and a group in the United States using reverse genetics methods independently and experimentally demonstrated that ACE2 could act as the receptor for SARS-CoV-2.[10][46][47][48][49][50] Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 has a higher affinity to human ACE2 than the original SARS virus strain.[51] An atomic-level image of the S protein has been created using cryogenic electron microscopy.[51][52]

SARS-Cov-2 produces at least three virulence factors that promote dissemination of new virions from host cells and inhibit immune response.[44]

Epidemiology

Based upon the low variability exhibited among known SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences, the strain is thought to have been detected by health authorities within weeks of its emergence among the human population in late 2019.[53][22] The virus subsequently spread to all provinces of China and to more than one hundred other countries in Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Oceania.[54] Human-to-human transmission of the virus has been confirmed in all of these regions.[9][55][56][57][58][59] On 30 January 2020, SARS-CoV-2 was designated a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by the WHO.[8][60]

As of 10 March 2023 (13:21 UTC), there were 676,609,955Template:Edit sup[61] confirmed cases of infection, of which [61] were within mainland China. While the proportion of infections that result in confirmed infection or progress to diagnosable disease remains unclear,[62] one mathematical model estimated the number of people infected in Wuhan alone at 75,815 as of 25 January 2020, at a time when confirmed infections were far lower.[63] The total number of deaths attributed to the virus was 6,881,955Template:Edit sup[61] as of 10 March 2023 (13:21 UTC). Over 70% of all deaths have occurred in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located;[54] before 24 February, the proportion was over 95%.[64][65]

The basic reproduction number () of the virus has been estimated to be between 1.4 and 3.9.[66][67][68][69] This means that each infection from the virus is expected to result in 1.4 to 3.9 new infections when no preventive measures are taken.

See also

References

- ^ "Coronavirus disease named Covid-19". BBC News Online. 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV): interim guidance v1, January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330376. WHO/2019-nCoV/Surveillance/v2020.1.

- ^ "Healthcare Professionals: Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "About Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 11 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "New-type coronavirus causes pneumonia in Wuhan: expert". Xinhua. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "CoV2020". GISAID EpifluDB. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ a b Wee SL, McNeil Jr. DG, Hernández JC (30 January 2020). "W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. (February 2020). "A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster". Lancet. 395 (10223): 514–523. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. PMID 31986261.

- ^ a b c d Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. (February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature: 1–4. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMID 32015507.

- ^ Perlman S (February 2020). "Another Decade, Another Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 760–762. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126. PMID 31978944.

- ^ a b Benvenuto D, Giovanetti M, Ciccozzi A, Spoto S, Angeletti S, Ciccozzi M (April 2020). "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology. 92 (4): 455–459. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688. PMID 31994738.

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 22 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330991.

- ^ Shield, Charli (7 February 2020). "Coronavirus: From bats to pangolins, how do viruses reach us?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) and the virus that causes it". World Health Organization. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

From a risk communications perspective, using the name SARS can have unintended consequences in terms of creating unnecessary fear for some populations.... For that reason and others, WHO has begun referring to the virus as "the virus responsible for COVID-19" or "the COVID-19 virus" when communicating with the public. Neither of these designations are [sic] intended as replacements for the official name of the virus as agreed by the ICTV.

- ^ "How does coronavirus spread?". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "How COVID-19 Spreads". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Getting your workplace ready for COVID-19" (PDF). World Health Organization. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. (March 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 929–936. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. PMID 32004427.

- ^ Kupferschmidt K (February 2020). "Study claiming new coronavirus can be transmitted by people without symptoms was flawed". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb1524.

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 12 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330777.

- ^ a b Cohen J (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Eschner K (28 January 2020). "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Yu WB, Tang GD, Zhang L, Corlett RT (21 February 2020). "Decoding evolution and transmissions of novel pneumonia coronavirus using the whole genomic data" (Document). doi:10.12074/202002.00033 (inactive 26 February 2020).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2020 (link) - ^ "Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZC45, complete genome" (Document). National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 15 February 2020.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Bat SARS-like coronavirus isolate bat-SL-CoVZXC21, complete genome" (Document). National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 15 February 2020.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome" (Document). National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). 10 February 2020.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)" (Document). World Health Organization (WHO). 24 February 2020.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|access-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Liu P, Chen W, Chen JP (October 2019). "Viral Metagenomics Revealed Sendai Virus and Coronavirus Infection of Malayan Pangolins (Manis javanica)". Viruses. 11 (11): 979. doi:10.3390/v11110979. PMC 6893680. PMID 31652964.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cyranoski D (7 February 2020). "Did pangolins spread the China coronavirus to people?". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00364-2.

- ^ Xiao K, Zhai J, Feng Y (February 2020). "Isolation and Characterization of 2019-nCoV-like Coronavirus from Malayan Pangolins". bioRxiv 2020.02.17.951335.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ Kelly, Guy (1 January 2015). "Pangolins: 13 facts about the world's most hunted animal". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ a b Wong MC, Cregeen SJJ, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF (February 2020). "Evidence of recombination in coronaviruses implicating pangolin origins of nCoV-2019". bioRxiv 2020.02.07.939207.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. (February 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (8): 727–733. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. PMID 31978945.

- ^ Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, et al. (February 2020). "The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 91: 264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMID 31953166.

- ^ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Wong AC, Li X, Lau SK, Woo PC (February 2019). "Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses". Viruses. 11 (2): 174. doi:10.3390/v11020174. PMC 6409556. PMID 30791586.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, et al. (February 2020). "Structure, function and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein". bioRxiv 2020.02.19.956581.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help); Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Andersen KG, Rambaut A, Lipkin WI, et al. (16 February 2020). "The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2". Virological. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Coutard B, Valle C, de Lamballerie X, et al. (February 2020). "The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade". Antiviral Research. 176: 104742. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104742. PMID 32057769.

- ^ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus (nCoV)". nextstrain.org. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. (15 February 2020). "Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study". Lancet. 395 (10223): 507–513. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. PMID 32007143.

- ^ a b c Wu C, Liu Y, Yang Y, et al. (February 2020). "Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods". Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Xu X, Chen P, Wang J, et al. (March 2020). "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". Science China Life Sciences. 63 (3): 457–460. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. PMID 32009228.

- ^ Letko M, Munster V (January 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B β-coronaviruses, including 2019-nCoV". bioRxiv 2020.01.22.915660.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ Letko M, Marzi A, Munster V (February 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for SARS-CoV-2 and other lineage B betacoronaviruses". Nature Microbiology. doi:10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y. PMID 32094589.

- ^ El Sahly HM. "Genomic Characterization of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus". New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Gralinski LE, Menachery VD (January 2020). "Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV". Viruses. 12 (2): 135. doi:10.3390/v12020135. PMID 31991541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. (February 2020). "Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding". Lancet. 395 (10224): 565–574. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. PMID 32007145.

- ^ a b Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, Abiona O, et al. (February 2020). "Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation". Science: eabb2507. doi:10.1126/science.abb2507. PMID 32075877.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Ryan F. (19 February 2020). "Scientists Create Atomic-Level Image of the New Coronavirus's Potential Achilles Heel". Gizmodo. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "What We Know Today about Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 and Where Do We Go from Here". GEN - Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. 19 February 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Coronavirus COVID-19 Global Cases by Johns Hopkins CSSE". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins CSSE. 6 March 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rothe C, Schunk M, Sothmann P, Bretzel G, Froeschl G, Wallrauch C, et al. (March 2020). "Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany". The New England Journal of Medicine. 382 (10): 970–971. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001468. PMID 32003551.

- ^ "The Coronavirus Is Now Infecting More People Outside China". Wired. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Khalik S (4 February 2020). "Coronavirus: Singapore reports first cases of local transmission; 4 out of 6 new cases did not travel to China". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Ecuador confirms five new cases of coronavirus, all close to initial patient". Reuters. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "Algeria confirms two more coronavirus cases". Reuters. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU)". ArcGIS. Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM (February 2020). "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". Lancet. 395 (10225): 689–697. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMID 32014114.

- ^ Boseley S, McCurry J (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus deaths leap in China as countries struggle to evacuate citizens". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Paulinus A (25 February 2020). "Coronavirus: China to repay Africa in safeguarding public health". The Sun. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. (January 2020). "Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. PMID 31995857.

- ^ Riou J, Althaus CL (January 2020). "Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020". Euro Surveillance. 25 (4). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058. PMC 7001239. PMID 32019669.

- ^ Liu T, Hu J, Kang M, Lin L (January 2020). "Transmission dynamics of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". bioRxiv 2020.01.25.919787.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ Read JM, Bridgen JRE, Cummings DAT, et al. (28 January 2020). "Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: early estimation of epidemiological parameters and epidemic predictions". MedRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.01.23.20018549. License:CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

Further reading

- Brüssow H (March 2020). "The Novel Coronavirus – A Snapshot of Current Knowledge". Microbial Biotechnology. 2020: 1–6. doi:10.1111/1751-7915.13557.

- Habibzadeh P, Stoneman EK (February 2020). "The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird's Eye View". The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 11 (2): 65–71. doi:10.15171/ijoem.2020.1921. PMID 32020915.

- World Health Organization (2020). Laboratory testing of human suspected cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection: interim guidance, 10 January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330374. WHO/2019-nCoV/laboratory/2020.1.

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO R&D Blueprint: informal consultation on prioritization of candidate therapeutic agents for use in novel coronavirus 2019 infection, Geneva, Switzerland, 24 January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330680. WHO/HEO/R&D Blueprint (nCoV)/2020.1.

External links

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak". World Health Organization (WHO).

- "SARS-CoV-2 (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Sequences". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- "COVID-19 Resource Centre". The Lancet.

- "Coronavirus (Covid-19)". The New England Journal of Medicine.

- "Covid-19: Novel Coronavirus Content Free to Access". Wiley.

- "2019-nCoV Data Portal". Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource.