2014 Winter Olympics

The 2014 Winter Olympics, officially called the XXII Olympic Winter Games (Template:Lang-fr) (Russian: XXII Олимпийские зимние игры, romanized: XXII Olimpiyskiye zimniye igry) and commonly known as Sochi 2014, were a major international multi-sport event held from February 7 to February 23, 2014 in Sochi, Krasnodar Krai, Russia, with opening rounds in certain events held on the eve of the opening ceremony, 6 February 2014. Both the Olympics and 2014 Winter Paralympics were organized by the Sochi Organizing Committee (SOOC). Sochi was selected as the host city in July 2007, during the 119th IOC Session held in Guatemala City. It was the first Olympics in Russia since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Soviet Union was the host nation for the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

A total of 98 events in 15 winter sport disciplines were held during the Games. A number of new competitions—a total of 12 accounting for gender—were held during the Games, including biathlon mixed relay, women's ski jumping, mixed-team figure skating, mixed-team luge, half-pipe skiing, ski and snowboard slopestyle, and snowboard parallel slalom. The events were held around two clusters of new venues: an Olympic Park constructed in Sochi's Imeretinsky Valley on the coast of the Black Sea, with Fisht Olympic Stadium, and the Games' indoor venues located within walking distance, and snow events in the resort settlement of Krasnaya Polyana.

In preparation, organizers focused on modernizing the telecommunications, electric power, and transportation infrastructures of the region. While originally budgeted at US$12 billion, various factors caused the budget to expand to over US$51 billion, surpassing the estimated $44 billion cost of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing as the most expensive Olympics in history.

The lead-up to these Games was marked by several major controversies, including allegations that corruption among officials led to the aforementioned cost overruns, concerns for the safety of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) athletes and spectators due to the effects of the Russian LGBT propaganda law, protests by ethnic Circassian activists over the site of Sochi (where they believe a genocide took place in the 19th century), and threats by jihadist groups tied to the insurgency in the North Caucasus. However, following the closing ceremony, commentators evaluated the Games to have been overall successful.[4][5]

Bidding process

Sochi was elected on 4 July 2007 during the 119th International Olympic Committee (IOC) session held in Guatemala City, Guatemala, defeating bids from Salzburg, Austria; and Pyeongchang, South Korea.[6] This is the first time that the Russian Federation has hosted the Winter Olympics. The Soviet Union was the host of the 1980 Summer Olympics held in and around Moscow.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Financing

| Funds approved from 2006 until 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Year | Billions of rubles[7] |

| 2006 | 5 |

| 2007 | 16 |

| 2008 | 32 |

| 2009 | 27 |

| 2010 | 22 |

| 2011 | 27 |

| 2012 | 26 |

| 2013 | 22 |

| 2014 | 8 |

As of October 2013, the estimated combined cost of the 2014 Winter Olympics had topped US$51 billion.[8] This amount includes the 214 billion rubles (US$6.5 billion) cost for Olympic games themselves and cost of Sochi infrastructural projects (roads, railroads, power plants). This total, if borne out, is over four times the initial budget of $12 billion (compared to the $8 billion spent for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver), and made the Sochi games the most expensive Olympics in history, exceeding the estimated $44 billion cost of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing,[9] which hosted 3 times as many events.[10]

According to Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Organizing Committee President and CEO Dmitry Chernyshenko, partnership and commercial programs allowed the use of funds generated by Sochi 2014 for the 2009–10 development period, postponing the need for the state funds guaranteed by the Russian Government. He confirmed that the Organizing Committee had raised more than $500 million through marketing in the first five months of 2009.[11] The Russian Government provided nearly 327 billion rubles (about US$10 billion) for the total development, expansion and hosting of the Games.[12] 192 billion rubles (US$6 billion) coming from the federal budget and 7 billion rubles (US$218 million) from the Krasnodar Krai budget and from the Sochi budget. The organizers expected to have a surplus of US$300 million when the Games conclude.[13]

Financing from non-budget sources (including private investor funds) is distributed as follows:[14]

- Tourist infrastructure: $2.6 billion

- Olympic venues: $500 million

- Transport infrastructure: $270 million

- Power supply infrastructure: $100 million

Venues

Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 526: Unable to find the specified location map definition: "Module:Location map/data/Afro-Eurasia2" does not exist. With an average February temperature of 8.3 °C (42.8 °F) and a humid subtropical climate, Sochi is the warmest city to host a Winter Olympic Games.[15] Sochi 2014 is the 12th straight Olympics to outlaw smoking; all Sochi venues, Olympic Park bars and restaurants and public areas were smoke-free during the Games.[16] It is also the first time that an Olympic Park has been built for hosting a winter games.

Sochi Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster)

The Sochi Olympic Park was built by the Black Sea coast in the Imeretinsky Valley, about 4 km (2.5 miles) from Russia's border with Abkhasia/Georgia.[17][18] The venues were clustered around a central water basin on which the Medals Plaza is built, allowing all indoor venues to be within walking distance. It also features "The Waters of the Olympic Park" (designed by California-based company WET), a choreographed fountain which served as the backdrop in the medals awards and the opening and closing ceremonies of the event.[19][20] The new venues include:[21]

- Fisht Olympic Stadium – ceremonies (opening/closing) 40,000 spectators

- Bolshoy Ice Dome – ice hockey (final), 12,000 spectators

- Shayba Arena – ice hockey, 7,000 spectators

- Adler Arena Skating Center – speed skating, 8,000 spectators

- Iceberg Skating Palace – figure skating, short track speed skating, 12,000 spectators

- Ice Cube Curling Center – curling, 3,000 spectators

- Main Olympic village

- International broadcasting centre and main press room

Krasnaya Polyana (Mountain Cluster)

- Laura Biathlon & Ski Complex – biathlon, cross-country skiing

- Rosa Khutor Extreme Park – freestyle skiing and snowboarding

- Rosa Khutor Alpine Resort – alpine skiing

- Sliding Center Sanki – bobsleigh, luge and skeleton

- RusSki Gorki Jumping Center – ski jumping and Nordic combined (both ski jumping and cross-country skiing on a 2 km route around the arena)

- Roza Khutor plateau Olympic Village

Post-Olympic usage

A street circuit known as the Sochi Autodrom was constructed in and around Olympic Park. Its primary use is to host the Formula One Russian Grand Prix, which held its inaugural edition in October 2014.[22][23][24]

Marketing

Logo and branding

The emblem of the 2014 Winter Olympics was unveiled in December 2009. While more elaborate designs with influence from Khokhloma were considered, organizers chose to use a more minimalistic and "futuristic" design instead, consisting only of typefaces with no drawn elements at all. The lettering was designed so that the "Sochi" and "2014" lettering would mirror each other vertically (particularly on the "hi" and "14" characters), "reflecting" the contrasts of Russia's landscape (such as Sochi itself, a meeting point between the Black Sea and the Western Caucasus).[25] Critics, including Russian bloggers, panned the logo for being too simplistic and lacking any real symbolism; Guo Chunning, designer of the 2008 Summer Olympics emblem Dancing Beijing, criticized it for its lack of detail, and believed it should have contained more elements that represented winter and Russia's national identity, aside from its blue color scheme and its use of .ru, the top-level domain of Russia.[25]

The Games' official slogan, Hot. Cool. Yours. (Жаркие. Зимние. Твои.), was unveiled on 25 September 2012, 500 days before the opening ceremony. Presenting the slogan, SOC president Dmitry Chernyshenko explained that it represented the "passion" and heated competition of the Games' athletes, the contrasting climate of Sochi, and a sense of inclusion and belonging.[26][27]

Mascots

For the first time in Olympic history, a public vote was held to decide the mascots for the 2014 Winter Olympics; the 10 finalists, along with the results, were unveiled during live specials on Channel One. On 26 February 2011, the official mascots were unveiled, consisting of a polar bear, a snow hare, and a snow leopard. The initial rounds consisted of online voting among submissions, while the final round involved text messaging.[28][29][30]

A satirical mascot known as Zoich (its name being an interpretation of the stylized "2014" lettering from the Games' emblem as a cyrillic word), a fuzzy blue frog with hypnotic multi-coloured rings (sharing the colors of the Olympic rings) on his eyeballs and the Imperial Crown ("to remind about statehood and spirituality"), proved popular in initial rounds of online voting, and became a local internet meme among Russians, with some comparing it to Futurama's "Hypnotoad". Despite its popularity, Zoich did not qualify for the final round of voting, with its creator, political cartoonist Egor Zhgun, claiming that organizers were refusing to respect public opinion. However, it was later revealed that Zoich was deliberately planted by organizers to help virally promote the online mascot vote.[30][31]

Video game

The official Olympic video game is the fourth game in the Mario & Sonic series, Mario & Sonic at the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games. It was released by Nintendo for the Wii U on 8 November 2013 in Europe, and 15 November 2013 in North America.[32] Others were Sochi 2014: Ski Slopestyle Challenge for Android operating system and Sochi 2014: Olympic Games Resort for online social network Facebook.[33]

Stamps and coins

In commemoration of the Games, Russian Post released a series of postage stamps depicting athletes, venues, and the mascots of the Games. The Bank of Russia also issued special coins and 100-ruble notes for the Games.[34]

Construction

The Olympic infrastructure was constructed according to a Federal Target Program (FTP). In June 2009, the Games' organizers reported they were one year ahead in building the main Olympic facilities as compared to recent Olympic Games.[35] In November 2011, IOC President Jacques Rogge was in Sochi and concluded that the city had made significant progress since he last visited eighteen months earlier.[36]

Telecommunications

According to the FTP, US$580 million would be spent on construction and modernization of telecommunications in the region. Avaya was named by the Sochi Organizing Committee as the official supplier of telecommunications equipment. Avaya provided the data network equipment, including switches, routers, security, telephones and contact-center systems. It provided engineers and technicians to design and test the systems, and worked with other technology partners to provide athletes, dignitaries and fans information about the Games.[37][38]

The 2014 Olympics is the first "fabric-enabled" Games using Shortest Path Bridging (SPB) technology.[39] The network is capable of handling up to 54,000 Gbit/s (54 Tbit/s) of traffic.[40]

Infrastructure built for the games included:

- A network of TETRA mobile radio communications for 100 user groups (with capacity of 10,000 subscribers);

- 712 km (442 mi) of fiber-optic cables along the Anapa-Dzhubga-Sochi highways and Dzhubga–Krasnodar branch;

- Digital broadcasting infrastructure, including radio and television broadcasting stations (building and communications towers) with coverage from Grushevaya Polyana (Pear Glade) to Sochi and Anapa cities. The project also included construction of infocommunications centre for broadcasting abroad via three HDTV satellites.

During the Games, the core networks of Rostelecom and Transtelekom were used.[41]

In January 2012, the newest equipment for the television coverage of the Games arrived in the port of Adler. Prepared specifically for the Games, a team of regional specialists and the latest technology provide a qualitatively new level of television production in the region.[42]

The fiber-optic channel links Sochi between Adler and Krasnaya Polyana. The 46-kilometre-long (29 mi) channel enables videoconferencing and news reporting from the Olympics.[43]

In November 2013, it was reported that the fiber-optic cable that was built by the Federal Communications Agency, Rossvyaz, had no operator. With Rostelecom and Megafon both refusing to operate it, the line was transferred to the ownership of the state enterprise Center for Monitoring & Development of Infocommunication Technologies (Template:Lang-ru).[44]

Russian mobile phone operator Megafon expanded and improved Sochi's telecom infrastructure with over 700 new 2G/3G/4G cell towers. Sochi was the first Games to offer 4G connectivity at a speed of 10 MB/sec.

In January 2014, Rostelecom reported that it had connected the Olympic media center in Sochi to the Internet and organized channels of communication with the main media center of the Olympic Games in the coastal cluster and press center in Moscow. The media center was built at total cost of 17 million rubles.[45][46]

Power infrastructure

A five-year strategy for increasing the power supply of the Sochi region was presented by Russian energy experts during a seminar on 29 May 2009, held by the Sochi 2014 Organizing Committee, and attended by International Olympic Committee (IOC) experts and officials from the Russian Ministry of Regional Development, the Russian Ministry of Energy, the State Corporation Olimpstroy and the Krasnodar Krai administration.[47]

According to the strategy, the capacity of the regional energy network would increase by two and a half times by 2014, guaranteeing a stable power supply during and after the Games.

The power demand of Sochi in the end of May 2009 was 424 MW. The power demand of the Olympic infrastructure was expected to be about 340 MW.

- Poselkovaya electrical substation became operational in early 2009.

- Sochi thermal power station reconstructed (expected power output was 160 MW)

- Laura and Rosa Khutor electrical substations were completed in November 2010

- Mzymta electrical substation was completed in March 2011

- Krasnopolyanskaya hydroelectric power station was completed in 2010

- Adler CHP station design and construction was completed in 2012. Expected power output was 360 MW[48]

- Bytkha substation, under construction with two transformers 25 MW each, includes dependable microprocessor-based protection

Earlier plans also include building combined cycle (steam and gas) power stations near the cities of Tuapse and Novorossiysk and construction of a cable-wire powerline, partially on the floor of the Black Sea.[49]

Transportation

The transport infrastructure prepared to support the Olympics includes many roads, tunnels, bridges, interchanges, railroads and stations in and around Sochi. Among others, 8 flyovers, 102 bridges, tens of tunnels and a bypass route for heavy trucks — 367 km (228 miles) of roads were paved.[50]

The Sochi Light Metro is located between Adler and Krasnaya Polyana connecting the Olympic Park, Sochi International Airport, and the venues in Krasnaya Polyana.[51]

The existing 102 km (63-mile), Tuapse-to-Adler railroad was renovated to provide double track throughout, increasing capacity and enabling a reliable regional service to be provided and extending to the airport. In December 2009, Russian Railways ordered 38 Siemens Mobility Desiro trains for delivery in 2013 for use during the Olympics, with an option for a further 16 partly built in Russia.[52] Russian Railways established a high-speed Moscow-Adler link and a new railroad (more than 60 kilometres or 37 miles long) passing by the territory of Ukraine.[53]

At Sochi International Airport, a new terminal was built along a 3.5 km (2.2-mile) runway extension, overlapping the Mzymta River.[54] Backup airports were built in Gelendzhik, Mineralnye Vody and Krasnodar by 2009.[55]

At the Port of Sochi, a new offshore terminal 1.5 km (0.93 mi) from the shore allows docking for cruise ships with capacities of 3,000 passengers.[56] The cargo terminal of the seaport would be moved from the centre of Sochi.

Roadways were detoured, some going around the construction site and others being cut off.[57]

In May 2009, Russian Railways started the construction of tunnel complex No. 1 (the final total is six) on the combined road (automobile and railway) from Adler to Alpica Service Mountain Resort in the Krasnaya Polyana region. The tunnel complex No. 1 is located near Akhshtyr in Adlersky City District, and includes:[58]

- Escape tunnel, 2.25 kilometres (1.40 mi), completed in 2010

- Road tunnel, 2,153 metres (7,064 ft), completed in 2013

- One-track railway tunnel, 2,473 metres (8,114 ft), completed in 2013

Russian Railways president Vladimir Yakunin stated the road construction costed more than 200 billion rubles.[59]

In addition, Sochi's railway stations were renovated. These are Dagomys, Sochi, Matsesta, Khosta, Lazarevskaya, and Loo railway stations. In Adler, a new railway station was built while the original building was preserved, and in the Olympic park cluster, a new station was built from scratch, the Olympic Park railway station. Another new railway station was built in Estosadok, close to Krasnaya Polyana.

Other infrastructure

Funds were spent on the construction of hotels for 10,300 guests.[61] The first of the Olympic hotels, Zvezdny (Stellar), was rebuilt anew.[62] Significant funds were spent on the construction of an advanced sewage treatment system in Sochi, designed by Olimpstroy. The system meets BREF standards and employs top available technologies for environment protection, including tertiary treatment with microfiltration.[63]

Six post offices were opened at competition venues, two of them in the main media centre in Olympic Park and in the mountain village of Estosadok. In addition to standard services, customers had access to unique services including two new products, Fotomarka and Retropismo. Fotomarka presents an opportunity to get a stylized sheet of eight souvenir stamps with one's own photos, using the services of a photographer in the office. Retropismo service allows a customer to write with their own stylus or pen on antique paper with further letters, winding string and wax seal affixing. All the new sites and post offices in Sochi were opened during the Olympics until late night 7 days a week, and employees were trained to speak English.[64]

The Games

Torch relay

On 29 September 2013, the Olympic torch was lit in Ancient Olympia, beginning a seven-day journey across Greece and on to Russia, then the torch relay started at Moscow on 7 October 2013 before passing 83 Russian cities and arriving at Sochi on the day of the opening ceremony, 7 February 2014.[65] It is the longest torch relay in Olympic history, a 40,000-mile route that passes through all regions of the country, from Kaliningrad in the west to Chukotka in the east.

The Olympic torch reached the North Pole for first time via a nuclear-powered icebreaker (50 Let Pobedy). The torch was also passed for the first time in space, though not lit for the duration of the flight for safety reasons, on flight Soyuz TMA-11M to the International Space Station (ISS). The spacecraft itself was adorned with Olympic-themed livery including the Games' emblem. Russian cosmonauts Oleg Kotov and Sergey Ryazansky waved the torch on a spacewalk outside ISS. The torch returned to Earth five days later on board Soyuz TMA-09M.[66][67] The torch also reached Europe's highest mountain, Mount Elbrus, and Siberia's Lake Baikal.[68]

Opening ceremony

The opening ceremony of the 2014 Winter Olympics was held on 7 February 2014 at Fisht Olympic Stadium, an indoor arena built specifically for the ceremonies. The ceremony featured scenes based around aspects of Russian history and arts, including ballet, classical music, the Russian Revolution, and the age of the Soviet Union. The opening scene of the ceremony featured a notable technical error, where one of five snowflakes, which were to expand to form the Olympic rings, malfunctioned and did not expand (a mishap mocked by the organizers at the closing ceremony where one of the roundrelay dance groups symbolizing the Olympic rings "failed" to expand). The torch was taken into the stadium by Maria Sharapova, who then passed it to Yelena Isinbayeva who, in turn, passed it to wrestler Aleksandr Karelin. Karelin then passed the torch to gymnast Alina Kabaeva. Figure skater Irina Rodnina took the torch and was met by former ice hockey goalkeeper Vladislav Tretiak, who exited the stadium to jointly light the Olympic cauldron located near the centre of Olympic Park.[69][70]

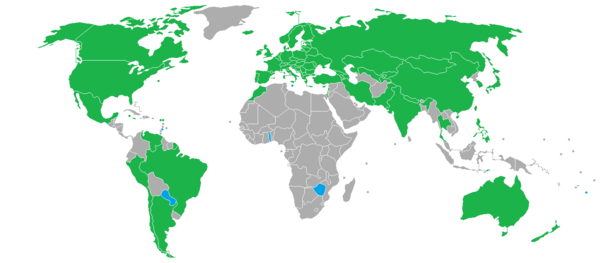

Participating National Olympic Committees

A record 88 nations qualified to compete,[71] which beat the previous record of 82 set at the previous Winter Olympics in Vancouver. The number of athletes who qualified per country is listed below. Seven nations—Dominica, Malta, Paraguay, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tonga, and Zimbabwe—made their Winter Olympics debut.[72]

Kristina Krone qualified to compete in her second consecutive games for Puerto Rico, but the island's Olympic Committee chose not to send her to compete again as they did in 2010.[73] Similarly, South Africa decided not to send alpine skier Sive Speelman to Sochi.[74] Algeria also did not enter its only qualified athlete, Mehdi-Selim Khelifi.[75]

a India's athletes originally competed as Independent Olympic Participants and marched under the Olympic flag during the opening ceremony, as India was originally suspended in December 2012 over the election process of the Indian Olympic Association.[76] On 11 February, the Indian Olympic Association was reinstated and India's athletes were allowed the option to compete under their own flag from that time onward.[77]

National houses

During the Games some countries had a national house, a meeting place for supporters, athletes and other followers.[78] Houses can be either free for visitors to access or they can have limited access by invitation only.[79]

| Nation | Location | Name | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mountain Cluster | Austria Tirol House | Official website | |

| Coastal Cluster (Next to Fisht Olympic Stadium) | Canada House | ||

| Zhemchuzhina hotel | China House | ||

| Adler | Czech House | ||

| Gornaya Karusel (Mountain Cluster) | Club France | Official website | |

| Estosadok, Krasnaya Polyana (Mountain Cluster) | German House | Official website | |

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | Italy House | Official website | |

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | Japan House | ||

| Radisson Hotel | Latvian House | ||

| Azimut Hotel Resort (near Coastal Cluster) | Holland Heineken House | Official website | |

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | NOC Hospitality Houses of Russia | ||

| Sochi railway station | Slovak Point | ||

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | Korea House | ||

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | House of Switzerland | Official website | |

| Olympic Park (Coastal Cluster) | USA House | Official website |

Sports

98 events over 15 disciplines in 7 sports were included in the 2014 Winter Olympics. The three skating sports disciplines are figure skating, speed skating, and short track speed skating. There were six skiing sport disciplines—alpine, cross-country skiing, freestyle, Nordic combined, ski jumping and snowboarding. The two bobsleigh sports disciplines are bobsleigh and skeleton. The other four sports are biathlon, curling, ice hockey, and luge. A total of twelve new events are contested to make it the largest Winter Olympics to date.[91][92] Numbers in parentheses indicate the number of medal events contested in each sports discipline.

On 6 April 2011, the IOC accepted a number of events that were submitted by their respective sports federations to be considered for inclusion into the official program of these Olympic Games.[93] The events include:

On 4 July 2011 the IOC announced that three events would be added to the program.[94] These events were officially declared by Olympic Committee President Jacques Rogge on 5 July 2011.[92]

- Ski slopestyle

- Snowboard slopestyle

- Snowboard parallel special slalom

Team alpine skiing was presented as a candidate for inclusion in the Olympic program but the Executive board of the IOC rejected this proposal. The International Ski Federation persisted with the nomination and this was considered.[95] There were reports of bandy possibly being added to the sports program,[96][97][98] but the IOC rejected this request. Subsequently, the international governing body, Federation of International Bandy, decided that Irkutsk and Shelekhov in Russia would host the 2014 Bandy World Championship just before the Olympics.

On 28 November 2006, the Executive Board of the IOC decided not to include the following sports in the review process of the program.[99]

Closing ceremony

The closing ceremony was held on 23 February 2014 between 20:14 MSK (UTC+4) and 22:25 MSK (UTC+4) at the Fisht Olympic Stadium in Sochi.[102] The ceremony was dedicated to Russian culture featuring world-renowned Russian stars like conductor and violinist Yuri Bashmet, conductor Valery Gergiev, pianist Denis Matsuev, singer Hibla Gerzmava and violinist Tatiana Samouil. These artists were joined by performers from the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters.

Medals

Sochi's medal design was unveiled in May 2013. The design is intended to resemble Sochi's landscape, with a semi-translucent section containing a "patchwork quilt" of diamonds representing mountains; the diamonds themselves contain designs that reflect Russia's regions.[103] Those who won gold medals on 15 February received special medals with fragments of the Chelyabinsk meteor, marking the one-year anniversary of the event where pieces of the cosmic body fell into the Chebarkul Lake in the Ural Mountains in central Russia.[104]

Medal table

The top ten listed NOCs by number of gold medals are listed below. The host nation, Russia, is highlighted.

To sort this table by nation, total medal count, or any other column, click on the ![]() icon next to the column title.

icon next to the column title.

* Host nation (Russia)

| Rank | NOC | Gold | Silver | Bronze | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 26 | |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 29 | |

| 3 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 25 | |

| 4 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 28 | |

| 5 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 24 | |

| 6 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 19 | |

| 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 11 | |

| 8 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| 9 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 17 | |

| 10 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 15 | |

| 11–26 | Remaining NOCs | 22 | 35 | 37 | 94 |

| Totals (26 entries) | 98 | 97 | 99 | 294 | |

Calendar

Template:2014 Winter Olympics Calendar

Security

Measures

Security during both the Olympics and Paralympics were handled by over 40,000 law enforcement officials, including police and the Russian Armed Forces.[105][106] A Presidential Decree signed by President Vladimir Putin took effect on 7 January, requiring that any protests and demonstrations in Sochi and the surrounding area through 21 March (the end of the Paralympics) be approved by the Federal Security Service.[107] For the duration of the decree, travel restrictions were also in effect in and around Sochi: "controlled" zones, dubbed the "ring of steel" by the media, covered the Coastal and Mountain clusters which encompass all of the Games' venues and infrastructure, including transport hubs such as railway stations. To enter controlled areas, visitors were required to pass through security checkpoints with x-ray machines, metal detectors and explosive material scanners.[108] Several areas were designated as "forbidden", including Sochi National Park and the border with Abkhazia.[107][109] An unmanned aerial vehicle squadron, along with S-400 and Pantsir-S1 air defense rockets were used to protect Olympic airspace. Four gunboats were also deployed on the Black Sea to protect the coastline.[110]

A number of security organizations and forces began stationing in and around Sochi in January 2014; Russia's Ministry of Emergency Situations (EMERCOM) was stationed in Sochi for the Games beginning on 7 January 2014.[111][112] A group of 10,000 Internal Troops of the Ministry of Interior also provided security services during the Games.[113] In mid-January, 1,500 Siberian Regional Command troops were stationed in a military town near Krasnaya Polyana.[114] A group of 400 cossacks in traditional uniforms were also present to accompany police patrols.[115][116] The 58th Army unit of the Russian Armed Forces, were defending the Georgia-Russia border.[117] The United States also supplied Navy ships and other assets for security purposes.[118]

Incidents and threats

Organizers received several threats prior to the Games. In a July 2013 video release, Chechen Islamist commander Dokka Umarov called for attacks on the Games, stating that the Games were being staged "on the bones of many, many Muslims killed ...and buried on our lands extending to the Black Sea."[119]

Threats were received from the group Vilayat Dagestan, which had claimed responsibility for the Volgograd bombings under the demands of Umarov, and a number of National Olympic Committees had also received threats via e-mail, threatening that terrorists would kidnap or "blow up" athletes during the Games. However, while the IOC did state that the letters "[contained] no threat and appears to be a random message from a member of the public", the U.S. ski and snowboarding teams hired a private security agency to provide additional protection during the Games.[117][120][121]

Media

Broadcasting rights

In most regions, broadcast rights to the 2014 Winter Olympics were packaged together with broadcast rights for the 2016 Summer Olympics, but some broadcasters obtained rights to further games as well. Domestic broadcast rights were sold by Sportfive to a consortium of three Russian broadcasters; Channel One, VGTRK, and NTV Plus.[122]

In the United States, the 2014 Winter Olympics were the first in a new, US$4.38 billion contract with NBC, extending its broadcast rights to the Olympic Games through 2020.[123]

In Canada, after losing the 2010 and 2012 Games to Bell Media and Rogers Media, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation re-gained broadcast rights to the Olympics for the first time since 2008, gaining rights to the 2014 and 2016 Games. Bell and Rogers sub-licensed pay-TV rights for their TSN, Sportsnet and Réseau des sports networks, as well as TVA Group's TVA Sports.[124][125][126][127]

In Australia, after all three major commercial networks pulled out of bidding on rights to both the 2014 and 2016 Games due to cost concerns, the IOC awarded broadcast rights to just the 2014 Winter Olympics to Network Ten for A$20 million.[128][129][130]

Filming

Several broadcasters used the Games to trial the emerging ultra high definition television (UHDTV) standard. Both NTV Plus and Comcast filmed portions of the Games in 4K resolution; Comcast offered its content through smart TV apps, while NTV+ held public and cinema viewings of the content. NHK filmed portions of the Games in 8K resolution for public viewing. Olympic sponsor Panasonic filmed the opening ceremony in 4K.[131][132][133][134]

Concerns and controversies

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (November 2015) |

The lead-up to the 2014 Winter Olympics were affected by numerous controversies and concerns. Russia received criticism for its policies surrounding the rights of LGBT people, including the denial of a proposed Pride House in Sochi for the Games, citing "public morality",[135] and the passing of a federal law in June 2013 which criminalized the distribution of material promoting "non-traditional sexual relationships" among minors.[136][137][138][139] Unauthorized pro-LGBT rallies occurred in Moscow and Saint Petersburg during the Games, and prominent Italian activist and former member of parliament Vladimir Luxuria (who was the first ever openly transgender MP in Europe) was detained in Sochi after wearing a rainbow-colored outfit, chanting slogans, and holding a banner reading "Gay is OK" in Russian whilst entering an Olympic venue. Sports Illustrated reported that an anti-gay demonstration occurred in Sochi during the games, seemingly defying a ban on unauthorized protests during the Games.[107][140][141][142] On 25 September 2014, seven months following the Games, the IOC instituted a new clause in the host city contract for the 2022 Winter Olympics, explicitly prohibiting discrimination.[143]

The Games also became notable for their severe cost overruns, which made them the most expensive Winter Olympics in history; Russian politician Boris Nemtsov cited allegations of corruption among government officials as a cause of the overruns, concluding that the Games were "nothing but a monstrous scam."[144] Allison Stewart of the Saïd Business School at Oxford, noted that relations between the government and construction companies were closer in Sochi than at other games.[145] In a press conference, IOC president Thomas Bach defended the high costs of the Games, stating that the costs were in line with previous Olympics, but that the additional costs were a "long-term investment" into making Sochi a year-round destination.[146] The quality and availability of accommodations in Sochi were affected by missed contractor deadlines and inclement weather. On the final weekend before the start of the Games, only six of the nine hotels for accredited members of the media had been completed. In the other three, journalists reported various issues, including rooms that were unclean, no working water, discoloured tap water, and missing furniture or amenities. Executive Director Gilbert Felli stated that the rooms would be finished by 5 February, while Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Kozak noted that the media hotels just needed a "final cleaning".[108][147][148][149][150]

Some Circassian organizations objected to the Games being held on land their ancestors held until 1864,[151][152] when most of them were vanquished at the end of the Russian-Circassian War (1763–1864), in what they consider to be ethnic cleansing or genocide.[153][154] They demanded the Games be cancelled or moved unless Russia apologized for their actions.[155] Some Circassian groups accepted the Olympics, and argued that symbols of Circassian history and culture should have been featured, as Australia, the United States and Canada did for their indigenous cultures in 2000, 2002, and 2010 respectively.[156] The Games' use of Krasnaya Polyana ("Red Hill" or "Red Glade") as a site for skiing and snowboarding events was also considered sensitive, as it was named for a group of Circassians who were defeated in a bloody battle with Russians while attempting to return home over it in 1864.[157][158]

Media coverage of the Games was also criticized for its political slant; some journalists and IOC officials claimed that coverage by Western media was overly critical, biased, and politicized,[159] influenced by schadenfreude and existing anti-Russian sentiment.[160][161] The mood greatly improved as the Games progressed.[162][163] With a few notable exceptions, NBC largely avoided broadcasting negative material, although several segments deemed "overly friendly to Russia" were harshly criticized by some U.S. conservatives.[164] Following the closing ceremony, Mark Sappenfield of The Christian Science Monitor concluded that by many measures the Olympics were "very successful." Sappenfield singled out the organization as particularly good, writing that "Athletes and Olympic officials were nearly unanimous: This was an extraordinarily well run Olympics."[4] Thomas Bach also voiced support, stating "We saw excellent Games and what counts most is the opinions of the athletes and they were enormously satisfied...You have to ask all those who criticised whether they change their opinions now."[5]

Notes and references

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Reveals its Slogan". Sochi 2014 Olympic and Paralympic Games Organizing Committee. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b "News". sochi2014.com. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Vladislav Tretyak and Irina Rodnina lit the Olympic flame at the Fisht Stadium in Sochi". Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ a b Sappenfield, Mark (24 February 2014). "Sochi Olympics report card: So how good were Putin's Games?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ a b Grohmann, Karolos (23 February 2014). "'Excellent' Sochi Games proved critics wrong, says IOC's Bach". Reuters. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi Elected as Host City of XXII Olympic Winter Games, International Olympic Committee". Olympic.org. 4 July 2007. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Federal budget 2007 includes almost 16 billion rubles for Sochi development". Interfax (in Russian). 6 July 2007. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008.[dead link]

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (30 October 2013). "Sochi: chaos behind the scenes of world's most expensive Winter Olympics". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Owen Gibson (9 October 2013). "Sochi 2014: the costliest Olympics yet but where has all the money gone?". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ The Waste and Corruption of Vladimir Putin's 2014 Winter Olympics, businessweek, 2 January 2014

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Confirms Ability to Self-finance in 2009–10". Sochi2014.com. 2 June 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ ""2014 Winter Olympics Create New Opportunities for U.S. Ag Exporters", from Alla Putiy & Erik W. Hansen" (PDF). Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Expects $300 Million Surplus". Gamesbids.com. 14 October 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Archived 2007-10-20 at the Wayback Machine Rosbalt.biz, 6 July 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Vancouver Olympics: Embarrassed Russia looks to 2014 Sochi Olympics The Christian Science Monitor, 1 March 2010

- ^ Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine[dead link] Around the Rings, 14 July 2011

- ^ "Sochi's mixed feelings over Olympics". BBC News. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ Russian Deputy PM leads Sochi delegation to inspect Munich Olympic Park Inside the Games, 22 May 2010

- ^ Madler, Mark (24 February 2014). "WET Design Runs Rings Around Rivals". San Fernando Business Journal. Los Angeles, California: California Business Journals. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ "California-based WET makes the waters dance at Sochi". Gizmag. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Посмотрели свысока Yugopolis, 16 July 2013

- ^ "Sochi track warms up for Russian F1 Grand Prix". RT. Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ^ Korsunskaya, Darya; Gennady Fydorov, Alan Baldwin (14 October 2010). "Sochi to host Russian GP from 2014–2020". Reuters. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ "IOC threatens to postpone Russian Grand Prix". GP Update. 13 January 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Behind Sochi's Futuristic Logo". The New Yorker. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi releases Olympic slogan that is neither hot, nor cool". USA Today. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "'Hot.Cool.Yours.' Decoding Russia's Sochi Olympic slogan". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Russian public to vote for Sochi 2014 mascot". InsideTheGames.biz. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 chooses three mascots for Olympics as Father Christmas withdraws in row over property rights". InsideTheGames.biz. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Mock mascot loses Olympic race, wins bloggers' hearts". Russia Today. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Mock mascot Zoich masterminded by Sochi 2014 organizers". Russia Today. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Mario & Sonic at the Sochi Winter Games & 3rd Sonic Nintendo Exclusive Revealed". Anime News Network.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games". Olympicvideogames.com. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ "The Sochi Stamp: A Sought-After Olympic Souvenir". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Russia prepares for Olympic Games 2014 faster than scheduled[dead link] ITAR-TASS, 27 June 2009

- ^ IOC Head Praises Sochi 2014 GamesBids.com, 24 November 2011

- ^ Bing Ads (23 April 2013). "Avaya Official supplyer of network equipment". Slideshare.net. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "US firm Avaya named as Sochi 2014 network equipment supplier". Insidethegames.biz. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games" (PDF). Avaya. 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ James Careless (December 2013). "Avaya builds massive Wi-Fi net for 2014 Winter Olympics". Network World.

- ^ "Сочи-2014 выходит на связь". Открытые системы, 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Инновационное олимпийское телевизионное оборудование впервые в Сочи". Broadcasting.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Fiber-optic communications in Olympic Sochi Mayak Radio, 28 March 2008 Template:Ru icon Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "'МИР ИТ' приютил олимпийскую ВОЛС". comnews.ru. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ ""Ростелеком" обеспечил телекоммуникационными услугами олимпийский медиацентр в Сочи". TASS-TELECOM. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Olympics' press center and Mountain Cluster's media center open in Sochi". ITAR-TASS. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ Games 2014 Will Double Sochi Power Supply Sochi 2014, 29 May 2009

- ^ Gazprom launches construction of Adler CHPS Gazprom, 28 September 2009

- ^ The power capacities of the Sochi region will increase before the Olympics by a factor of four RBC, 6 July 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Sochi welcomes 2014 Winter Olympics with traditional Russian hospitality". En.itar-tass.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Sochi opens new rail line for 2014 Winter Olympics Inside the Games, 17 February 2012

- ^ Siemens signs Russian Olympic train order Railway Gazette International, 1 January 2010

- ^ Expensive road to the Olympics Gudok, 22 August 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Runway in Sochi airport will cross the river YuGA.ru, 8 July 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Russia to build 3 reserve airports in country's south by 2009 RIA Novosti, 7 July 2007

- ^ "Playing in the snow | WAG MAGAZINE ONLINE". Wagmag.com.

- ^ Archived 2011-08-12 at the Wayback Machine DP.RU, 8 October 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Archived 2010-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Interfax, 27 May 2009 Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Russian Railways President Yakunin sums up investment programme for first 7 months of 2011". Russian Railways. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ NASA – Sochi at night

- ^ Sochi is not a place for recreation Gazeta.ru, 5 July 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Construction of the first olympic hotel starts in Sochi RIA Novosti, 7 August 2007 Template:Ru icon

- ^ Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Press Service of the Ministry of Natural Resources of Russian Federation, 13 July 2009 Template:Ru icon

- ^ "Гости Олимпиады смогут отправить написанное пером письмо, оплатив почтовые услуги маркой с собственной фотографией". TASS Telecom. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ Lally, Kathy (1 October 2013). "Russia anti-gay law casts a shadow over Sochi's 2014 Olympics". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ^ "Soyuz TMA-09M safely returns crew back to Earth". NASASpaceFlight. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ 9. listopadu 2013 17:51. "Kosmonauti si poprvé ve volném vesmíru předali olympijskou pochodeň". Technet.idnes.cz. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Loumena, Dan (23 November 2013). "Sochi Olympic torch takes plunge into world's deepest lake". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ Faith Karimi; Michael Martinez (7 February 2014). "Sochi 2014 begins with teams, classical music and a flying girl". CNN. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Kathy Lally; Will Englund (7 February 2014). "Olympics open in Sochi with extravagant pageant". Washington Post. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Record 88 nations to participate in Winter Games". Global News. Sochi, Russia. Associated Press. 2 February 2014. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ MacKenzie, Eric (16 January 2014). "Sochi Spotlight: Zimbabwe's first Winter Olympian". Pique Newsmagazine. Whistler, British Columbia, Canada. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Pagan Rivera, Esteban (12 January 2014). "Kristina Krone: Quería ir a Sochi, pero nunca recibió contestación del Comité Olímpico". Primerahora (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ "Sascoc crush Speelman's Olympic dream". http://www.iol.co.za/. IOL Sport. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Dubault, Fabrice (24 January 2014). "L'histoire invraisemblable de Mehdi Khelifi privé de J.O par l'Algérie". France 3. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Sochi Games: Four Indian skiers to go as independent athletes". Zee news. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "IOC Executive Board lifts suspension of NOC of India". Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "National Olympic Houses". tripadvisor. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Olympic Parc; Hospitality Houses". sochi2014.com. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Opening Canada House" (in Dutch). CBC. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "China House opens in Sochi". XinHua Net. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Zeman slavnostně otevřel Český dům a pravil: Budu váš maskot" (in Czech). Lidové noviny. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Dossier de presse Sotchi 201" (PDF) (in French). http://espritbleu.franceolympique.com. 28 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

{{cite news}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Deutsches Haus Sotschi 2014 in Russlands Bergen". DOSB. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ 5 min fa. "Sochi, la Gazzetta entra a Casa Italia: tra cantieri, optional e sobrietà – La Gazzetta dello Sport". Gazzetta.it. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ lsm.lv. "Linda Leen nozog hokejistu sirdis". Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Holland Heineken House dichter bij olympiërs dan ooit" (in Dutch). nusport.nl. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Slovak athletes set for Sochi". The Slovak Spectator. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ 대한체육회, 소치에 코리아하우스 오픈 (in Korean). Yonhap News. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) Template:Nl icon - ^ "USOC plans USA House sites in Sochi, at home". sportsbusinessdaily.com. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ^ "Discover the twelve new winter sports events for Sochi 2014!". Olympic.org. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Rogge announces three new disciplines for Sochi 2014". Russia Today. TV-Novosti. 5 July 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "Women's ski jumping gets 2014 Sochi Olympics go-ahead". Bbc.co.uk. 6 April 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Thompson, Anna (5 July 2011). "Slopestyle given Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics go-ahead". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "FIS Congress 2010 Decisions". FIS-Ski. Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Russian ice hockey will be skating in Sochi". Infox.ru. AktivMedia. 7 June 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ It's Not Hockey, It's Bandy

- ^ "No time to relax! The show must go on...again!". Eastbourneherald.co.uk. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Olympic Programme Updates". Olympic.org. International Olympic Committee. 28 November 2006. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 20 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "No Olympics for Ski Mountaineering". The Mountain World. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "No inclusion of ski orienteering in the IOC review process for 2014". International Orienteering Federation. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Closing Ceremony Unites Olympic Generations". Sochi 2014. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Unveils Olympic Medals". Olympic.org. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Winners at Sochi Winter Olympics to receive pieces of Russia meteorite". London: The Telegraph. 26 July 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Russian Police to Speak 3 Languages at Sochi Olympics – Ministry". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Russian Military to Ensure Security at 2014 Olympics". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "Sochi Olympic Protests to Require Approval from Russia's Security Service". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ a b Oliphant, Roland; Lundy, Jack (2 February 2014). "Sochi Olympic organisers face accommodation crisis". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (5 February 2014). "The shambles behind the scenes at Sochi". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "Russia takes unprecedented security measures ahead of Sochi Olympics". ITAR TASS. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ "Space monitoring systems of emergency situations deployed in Sochi". ITAR TASS. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Russian emergencies minister praises Sochi security system". ITAR TASS. 27 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Internal Troops to provide security at Sochi Olympics". Russia Beyond the Headlines. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Siberia joins national effort to make the Sochi Olympics safe and successful". Siberia Times. 16 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Sochi Drafts In Cossacks for Olympic Security". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ "Some 300 Cossacks to Help Police Sochi Olympics". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 9 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Olympic Teams Prepare for Possible Security Crisis in Sochi". The Moscow Times. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ "Obama offers US security assistance to Putin as Olympic terror fears mount". Fox News. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Caucasus Emirate Leader Calls On Insurgents To Thwart Sochi Winter Olympics". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Rumsby, Ben (22 January 2014). "Winter Olympics 2014: email threat to 'blow up' athletes at Sochi Games dismissed by IOC". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ "European Olympic Committees Report Sochi Terror Threats". En.ria.ru. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Love, Tom (3 September 2012). "Sportfive concludes Olympic agreement in Russia". SportsPro. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Lazarus: We Believe Sochi Olympics Will Be Profitable". Broadcasting & Cable. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Sportsnet to air 200 hours of Sochi Games". Sportsnet. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "CBC/Radio Canada welcomes partners in 2014 Sochi Olympics coverage". CBC. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ^ "CBC/Radio-Canada seals agreement with TVA Sports for the Sochi 2014 Olympic Winter Games". Canada Newswire. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ "CBC wins rights to 2014, 2016 Olympic Games". CBC Sports. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Olympic fury over rules for TV sport". The Australian. 7 April 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ "Seven withdraws from bidding for Olympics as price tag proves too great for TV networks". Fox Sports. 8 April 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ MacKay, Duncan (12 May 2013). "Ten Network signs $20 million deal to broadcast Sochi 2014 in Australia, claim reports". Inside the Games. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ Pennington, Adrian. "Comcast to Produce Olympics 2014 in Ultra HD". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Russia to transmit 4K from Sochi". TVBEurope. NewBay Media. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Putin cancels New Year holidays for officials responsible for Winter Games". ITAR-TASS. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ Pennington, Adrian (4 February 2014). "Sochi Games to Set Record for Live and VOD Streaming". Streaming Media Europe. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Judge bans Sochi 2014 gay Pride House claiming it would offend "public morality"". Inside the Games. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (24 July 2013). "Russia's Anti-Gay Laws Present Challenge for NBC's Olympics Coverage". Variety. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Fierstein, Harvey (21 July 2013). "Russia's Anti-Gay Crackdown". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M. (11 August 2013). "Gays in Russia Find No Haven, Despite Support From the West". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ Skybenko, Ella (7 February 2014). "Companies can help advance human rights; Sochi shows they rarely use it". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014: Vladimir Luxuria arrested for holding 'Gay is OK' banner". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi activist arrested for pro-gay chant". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ "WATCH: LGBT Russians Arrested, Antigay Protestors Undisturbed". The Advocate. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ "Olympic anti-discrimination clause introduced after Sochi gay rights row". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Bennetts, Marc (19 January 2014). "Winter Olympics 2014: Sochi Games "nothing but a monstrous scam," says Kremlin critic Boris Nemtsov". Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ "The Sochi Olympics: Castles in the sand". The Economist. 13 July 2013. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ^ "Bach: 'I am still assured' of security in Sochi". Associated Press. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ "From Sochi, journalists report Winter Olympics woes: poor conditions and ongoing construction". New York Daily News. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi Olympics: Hotel delays aren't affecting athletes, IOC official says". The Star. Toronto. Associated Press. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Sochi 2014 Olympics: 'Worst. Games. Ever?' No, pampered journalists should just chill: DiManno". Toronto Star. 5 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ St Clair, Stacy (5 February 2014). "Welcome to Sochi: Beware the water". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- ^ Jaimoukha, Amjad. Ancient Circassian Cultures and Nations in the First Millennium BCE. Pages 1–7, 9–14

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica entry for Circassians: "From ancient times Circassia, comprising roughly the northwestern region of the Caucasus, acquired the exotic reputation common to lands occupying a crucial area between rival empires..."

- ^ "145th Anniversary of the Circassian Genocide and the Sochi Olympics Issue". Reuters. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ Ellen Barry (20 May 2011). "Georgia Says Russia Committed Genocide in 19th Century". The New York Times.

- ^ "Olympics-IOC says Russia-Georgia conflict "a sad reality"". Reuters. 9 August 2008.

- ^ Azamat Bram. Circassians Voice Olympian Anger. Institute for War and Peace Reporting Caucasus Reporting Service No. 413, 5 October 2007. Retrieved on 2 April 2010.

- ^ Andrea Alexander (9 February 2010). "North Jersey Circassians 'in exile' launch Olympic protest". The Record. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ Gabriele Barbati (6 February 2014). "Circassians Protest Winter Olympics Being Held At Sochi Genocide Site". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ Nakamura, David (17 December 2013). "Obamas, Biden to skip the Winter Olympics in Russia". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Bidder, Benjamin (11 February 2014). "Sochi Schadenfreude: 'Ha Ha, The Russians Screwed It Up Again!'". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Ioffe, Julia (6 February 2014). "Russians Think We're Engaging in Olympic Schadenfreude. They're Right". The New Republic. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ McNamara, Mary (12 February 2014). "Critic's Notebook: Sochi Games don't live down to the negative hype". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "As always, athletes made Olympics a joy". Sun-Sentinel. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Farhi, Paul (21 February 2014). "In coverage of Olympics, NBC has largely steered clear of controversy". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

External links

- Official Sochi 2014 Template:Ru icon Template:En icon Template:Fr icon

- Sochi 2014 Template:Fr icon on Olympic.org (IOC)

- 2014 Winter Olympics on Facebook

- Olympstroy State Corporation Template:Ru icon Template:En icon - responsible for Sochi Olympics construction and development

- Sochi 2014 links on Open Directory Project (DMOZ)

- Sochi satellite image on Google Maps

- Complete video of Sochi 2014 Opening Ceremony