York

| York | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Clockwise from the top left: Micklegate Bar; York Minster from the city walls; Lendal Bridge; an aerial view of the city; and the castle | |

| |

Location within North Yorkshire | |

| Area | 33.7 km2 (13.0 sq mi) |

| Population | 141,685 (2021 census) [1] |

| • Density | 4,204/km2 (10,890/sq mi) |

| Unitary authority population | 202,871 (2021 census) |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | YORK |

| Postcode district | YO1, YO10, YO19, YO23-24, YO26, YO30-32, YO41 |

| Dialling code | 01904 |

| Police | North Yorkshire |

| Fire | North Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| Website | york.gov.uk |

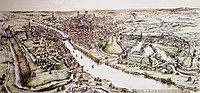

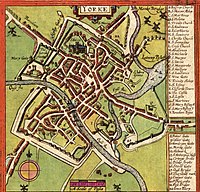

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss. It is the county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a minster, castle, and city walls. It is the largest settlement and the administrative centre of the wider City of York district.

The city was founded under the name of Eboracum in 71 AD. It then became the capital of the Roman province of Britannia Inferior, and later of the kingdoms of Deira, Northumbria, and Scandinavian York. In the Middle Ages, it became the northern England ecclesiastical province's centre, and grew as a wool-trading centre.[2] In the 19th century, it became a major railway network hub and confectionery manufacturing centre. In the Second World War, part of the Baedeker Blitz bombed the city. Although less targeted during the war than other, more industrialised northern cities, several historic buildings were gutted and restoration took place up until the 1960s.[3]

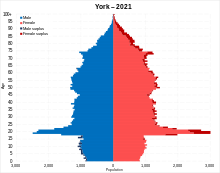

The city is one of 15 in England to have a lord mayor, and one of three to have "The Right Honourable" title affixed, the others being London's and Bristol's. Historic governance of the city was as a county corporate, not included in the county's riding system. The city has since been covered by a municipal borough, county borough, and since 1996 a non-metropolitan district (the City of York), which also includes surrounding villages and rural areas, and the town of Haxby. The current district's local council is responsible for providing all local services and facilities throughout this area. York's city proper area had a population of 141,685 at the 2021 UK census.[1] The wider district had a population of 198,100. According to 2021[update] census data, the wider district has a population of 202,800, a 2.4% increase compared to the 2011 census.[4]

Toponymy

The name York (Template:Lang-non) is derived from the Brittonic name Eburākon (Latinised as Eboracum or Eburacum), a combination of eburos "yew tree" (compare with Welsh efwr and Breton evor, both meaning "alder buckthorn", and Old Irish ibar, Irish iobhar, iubhar, and iúr, and Scottish Gaelic iubhar) and a suffix of appurtenance *-āko(n), meaning "belonging to", or "place of" (compare Welsh -og).[5] Put together, these old words meant "place of the yew trees". (In Welsh, efrog; in Old Irish, iubrach; in Irish Gaelic, iúrach; and in Scottish Gaelic, iùbhrach). The city is called Eabhraig in Scottish Gaelic and Eabhrac in Irish—names derived from the Latin word Eboracum. A proposed alternative meaning is "the settlement of (a man named) Eburos", a Celtic personal name spelled variously in different documents as Eβουρος, Eburus and Eburius: when combined with the Celtic possessive suffix *-āko(n), the word could be used to denote the property of a man with this name.[6][5]

The name Eboracum became the Anglian Eoforwic in the 7th century: a compound of Eofor-, from the old name, and -wic, meaning "village", probably by conflation of the element Ebor- with a Germanic root *eburaz ('boar'); by the 7th century, the Old English for 'boar' had become eofor. When the Danish army conquered the city in 866, it was renamed Jórvík.[7]

The Old French and Norman name of the city following the Norman Conquest was recorded as Everwic (modern Norman Évèroui) in works such as Wace's Roman de Rou.[8] Jórvík, meanwhile, gradually reduced to York in the centuries after the Conquest, moving from the Middle English Yerk in the 14th century through Yourke in the 16th century to Yarke in the 17th century. The form York was first recorded in the 13th century.[2][9] Many company and place names, such as the Ebor race meeting, refer to the Latinised Brittonic, Roman name.[10]

The 12th‑century chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his fictional account of the prehistoric kings of Britain, Historia Regum Britanniae, suggests the name derives from that of a pre-Roman city founded by the legendary king Ebraucus.[11]

The Archbishop of York uses Ebor as his surname in his signature.[12]

History

Early history

Archaeological evidence suggests that Mesolithic people settled in the region of York between 8000 and 7000 BC, although it is not known whether their settlements were permanent or temporary. By the time of the Roman conquest of Britain, the area was occupied by a tribe known to the Romans as the Brigantes. The Brigantian tribal area initially became a Roman client state, but later its leaders became more hostile and the Roman Ninth Legion was sent north of the Humber into Brigantian territory.[13]

The city was founded in 71 AD, when the Ninth Legion conquered the Brigantes and constructed a wooden military fortress on flat ground above the River Ouse close to its confluence with the River Foss. The fortress, whose walls were rebuilt in stone by the VI legion based there subsequent to the IX legion, covered an area of 50 acres (20 ha) and was inhabited by 6,000 legionary soldiers. The site of the principia (HQ) of the fortress lies under the foundations of York Minster, and excavations in the undercroft have revealed part of the Roman structure and columns.[7][14]

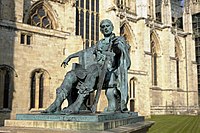

The Emperors Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and Constantius I all held court in York during their various campaigns. During his stay 207–211 AD, the Emperor Severus proclaimed York capital of the province of Britannia Inferior, and it is likely that it was he who granted York the privileges of a 'colonia' or city. Constantius I died in 306 AD during his stay in York, and his son Constantine the Great was proclaimed Emperor by the troops based in the fortress.[14][15] In 314 AD a bishop from York attended the Council at Arles to represent Christians from the province.[16]

While the Roman colonia and fortress were on high ground, by 400 AD the town was victim to occasional flooding from the Rivers Ouse and Foss, and the population reduced.[17] York declined in the post-Roman era, and was taken and settled by the Angles in the 5th century.[18]

Reclamation of parts of the town was initiated in the 7th century under King Edwin of Northumbria, and York became his chief city.[19] The first wooden minster church was built in York for the baptism of Edwin in 627, according to the Venerable Bede.[20] Edwin ordered the small wooden church be rebuilt in stone; however, he was killed in 633, and the task of completing the stone minster fell to his successor Oswald.[7][21] In the following century, Alcuin of York came to the cathedral school of York. He had a long career as a teacher and scholar, first at the school at York now known as St Peter's School, founded in 627 AD, and later as Charlemagne's leading advisor on ecclesiastical and educational affairs.[22]

In 866, Northumbria was in the midst of internecine struggles when the Vikings raided and captured York. As a thriving Anglo-Saxon metropolis and prosperous economic hub, York was a clear target for the Vikings. Led by Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan, Scandinavian forces attacked the town on All Saints' Day. Launching the assault on a holy day proved an effective tactical move – most of York's leaders were in the cathedral, leaving the town vulnerable to attack and unprepared for battle. After it was conquered, the city was renamed from the Saxon Eoforwic to Jorvik. It became the capital of Viking territory in Britain, and at its peak boasted more than 10,000 inhabitants. This was a population second only to London within Great Britain. Jorvik proved an important economic and trade centre for the Vikings. Norse coinage was created at the Jorvik mint, while archaeologists have found evidence of a variety of craft workshops around the town's central Coppergate area. These demonstrate that textile production, metalwork, carving, glasswork and jewellery-making were all practised in Jorvik. Materials from as far afield as the Persian Gulf have also been discovered, suggesting that the town was part of an international trading network.[23] Under Viking rule the city became a major river port, part of the extensive Viking trading routes throughout northern Europe. The last ruler of an independent Jórvík, Eric Bloodaxe, was driven from the city in 954 AD by King Eadred in his successful attempt to complete the unification of England.[24]

After the conquest

In 1068, two years after the Norman conquest of England, the people of York rebelled. Initially they succeeded, but upon the arrival of William the Conqueror the rebellion was put down. William at once built a wooden fortress on a motte. In 1069, after another rebellion, the king built another timbered castle across the River Ouse. These were destroyed in 1069 and rebuilt by William about the time of his ravaging Northumbria in what is called the "Harrying of the North" where he destroyed everything from York to Durham. The remains of the rebuilt castles, now in stone, are visible on either side of the River Ouse.[25][26]

The first stone minster church was badly damaged by fire in the uprising, and the Normans built a minster on a new site. Around the year 1080, Archbishop Thomas started building the cathedral that in time became the current Minster.[21]

In the 12th century York started to prosper. In 1190, York Castle was the site of an infamous massacre of its Jewish inhabitants, in which at least 150 were murdered, although some authorities put the figure as high as 500.[27][28]

The city, through its location on the River Ouse and its proximity to the Great North Road, became a major trading centre. King John granted the city's first charter in 1212,[29] confirming trading rights in England and Europe.[21][30] During the later Middle Ages, York merchants imported wine from France, cloth, wax, canvas, and oats from the Low Countries, timber and furs from the Baltic and exported grain to Gascony and grain and wool to the Low Countries.[31]

York became a major cloth manufacturing and trading centre. Edward I further stimulated the city's economy by using the city as a base for his war in Scotland. The city was the location of significant unrest during the so-called Peasants' Revolt in 1381. The city acquired an increasing degree of autonomy from central government including the privileges granted by a charter of Richard II in 1396.

16th to 18th centuries

The city underwent a period of economic decline during Tudor times. Under King Henry VIII, the Dissolution of the Monasteries saw the end of York's many monastic houses, including several orders of friars, the hospitals of St Nicholas and of St Leonard, the largest such institution in the north of England. This led to the Pilgrimage of Grace, an uprising of northern Catholics in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire opposed to religious reform. Henry VIII restored his authority by establishing the Council of the North in York in the dissolved St Mary's Abbey. The city became a trading and service centre during this period.[32][33]

Anne of Denmark came to York with her children Prince Henry and Princess Elizabeth on 11 June 1603. The Mayor gave her a tour and offered her spiced wine, but she preferred beer.[34] Guy Fawkes, who was born and educated in York, was a member of a group of Roman Catholic restorationists that planned the Gunpowder Plot.[35] Its aim was to displace Protestant rule by blowing up the Houses of Parliament while King James I, the entire Protestant, and even most of the Catholic aristocracy and nobility were inside.

In 1644, during the Civil War, the Parliamentarians besieged York, and many medieval houses outside the city walls were lost. The barbican at Walmgate Bar was undermined and explosives laid, but the plot was discovered. On the arrival of Prince Rupert, with an army of 15,000 men, the siege was lifted. The Parliamentarians retreated some 6 miles (10 km) from York with Rupert in pursuit, before turning on his army and soundly defeating it at the Battle of Marston Moor. Of Rupert's 15,000 troops, 4,000 were killed and 1,500 captured. The siege was renewed and the city surrendered to Sir Thomas Fairfax[32] on 15 July.

Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, and the removal of the garrison from York in 1688, the city was dominated by the gentry and merchants, although the clergy were still important. Competition from Leeds and Hull, together with silting of the River Ouse, resulted in York losing its pre-eminent position as a trading centre, but its role as the social and cultural centre for wealthy northerners was rising. York's many elegant townhouses, such as the Lord Mayor's Mansion House and Fairfax House date from this period, as do the Assembly Rooms, the Theatre Royal, and the racecourse.[33][36]

Modern history

The railway promoter George Hudson was responsible for bringing the railway to York in 1839. Although Hudson's career as a railway entrepreneur ended in disgrace and bankruptcy, his promotion of York over Leeds, and of his own railway company (the York and North Midland Railway), helped establish York as a major railway centre by the late 19th century.[37]

The introduction of the railways established engineering in the city.[38][39] At the turn of the 20th century, the railway accommodated the headquarters and works of the North Eastern Railway, which employed more than 5,500 people. The railway was instrumental in the expansion of Rowntree's Cocoa Works. It was founded in 1862 by Henry Isaac Rowntree, who was joined in 1869 by his brother the philanthropist Joseph.[40] Another chocolate manufacturer, Terry's of York, was a major employer.[33][41] By 1900, the railways and confectionery had become the city's two major industries.[39]

York was a centre of early photography, as described by Hugh Murray in his 1986 book Photographs and Photographers of York: The Early Years, 1844–79. Photographers who had studios in York included William Hayes, William Pumphrey, and Augustus Mahalski who operated on Davygate and Low Petergate in the 19th century, having come to England as a refugee after serving as a Polish lancer in the Austro-Hungarian war.[42][43]

In 1942, the city was bombed during the Second World War (part of the Baedeker Blitz) by the German Luftwaffe and 92 people were killed and hundreds injured.[44] Buildings damaged in the raid included the Railway Station, Rowntree's Factory, Poppleton Road Primary School, St Martin-le-Grand Church, the Bar Convent and the Guildhall which was left in total disrepair until 1960.

With the emergence of tourism, the historic core of York became one of the city's major assets, and in 1968 it was designated a conservation area.[45] The existing tourist attractions were supplemented by the establishment of the National Railway Museum in York in 1975,[46] the Jorvik Viking Centre in 1984[47] and the York Dungeon in 1986.[48] The opening of the University of York in 1963 added to the prosperity of the city.[49] In March 2012, York's Chocolate Story opened.[50]

York was voted European Tourism City of the Year by European Cities Marketing in June 2007, beating 130 other European cities to gain first place, surpassing Gothenburg in Sweden (second) and Valencia in Spain (third).[51] York was also voted safest place to visit in the 2010 Condé Nast Traveller Readers' Choice Awards.[52] In 2018, The Sunday Times deemed York to be its overall 'Best Place to Live' in Britain, highlighting the city's "perfect mix of heritage and hi-tech" and as a "mini-metropolis with cool cafes, destination restaurants, innovative companies – plus the fastest internet in Britain".[53][54] The result was confirmed in a YouGov survey, reported in August 2018, with 92% of respondents saying that they liked the city, more than any of 56 other British cities.[55]

Governance

Local

The City of York is governed by the City of York Council. It is a unitary authority that operates on a leader and cabinet style of governance, having the powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council combined. It provides a full range of local government services including Council Tax billing, libraries, social services, processing planning applications, waste collection and disposal, and it is a local education authority. The city council consists of 47 councillors[56][57] representing 21 wards, with one, two or three per ward serving four-year terms. Its headquarters are at the Guildhall and West Offices in the city centre.

York is divided into 21 administrative wards: Acomb, Bishopthorpe, Clifton, Copmanthorpe, Dringhouses and Woodthorpe, Fishergate, Fulford and Heslington, Guildhall, Haxby and Wigginton, Heworth, Heworth Without, Holgate, Hull Road, Huntington and New Earswick, Micklegate, Osbaldwick and Derwent, Rawcliffe and Clifton Without, Rural West York, Strensall, Westfield, and Wheldrake.[58]

The members of the cabinet, led by the Council Leader, makes decisions on their portfolio areas individually.[59][60] Following the Local Government Act 2000, the Council Leader commands the confidence of the city council; the leader of the largest political group and head of the City of York Council. The Leader of the council and the cabinet (consisting of all the executive councillors) are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the city council. The current Council Leader, Liberal Democrats' Cllr Keith Aspden, was appointed on 22 May 2019, following the 2019 City of York Council election.

York's first citizen and civic head is the Lord Mayor, who is the chairman of the City of York Council. The appointment is made by the city council each year in May, at the same time appointing the Sheriff, the city's other civic head. The offices of Lord Mayor and Sheriff are purely ceremonial. The Lord Mayor carries out civic and ceremonial duties in addition to chairing full council meetings.[57] The incumbent Lord Mayor since 26 May 2022 is Councillor David Carr, and the Sheriff is Suzie Mercer.[61]

York Youth Council consists of several young people who negotiate with the councillors to get better facilities for York's young people, and who also elect York's Member of Youth Parliament.[62][63]

As a result of the 2019 City of York Council election the Conservative Party was reduced to two seats. The Liberal Democrats had 21 councillors. The Labour Party had 17 councillors and the Green Party had four with three Independents.[64] Due to no overall control, the Liberal Democrats and the Green Party agreed to form a coalition on 14 May 2019.[65]

| Party | Seats | City of York Council (2019 election) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democrats | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Labour | 17 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Green | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservative | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Independent | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

York is the traditional county town of Yorkshire, and therefore did not form part of any of its three historic ridings, or divisions. Its Mayor has had the status of Lord Mayor since 1370. York is an ancient borough, and was reformed by the Municipal Corporations Act 1835 to form a municipal borough. It gained the status of a county borough in 1889, under the Local Government Act 1888, and existed so until 1974, when, under the Local Government Act 1972, it became a non-metropolitan district in the county of North Yorkshire, whilst retaining its Lord Mayor and its Sheriff.[66][67] As a result of 1990s UK local government reform, York regained unitary status and saw a substantial alteration in its borders, taking in parts of Selby and Harrogate districts, and about half the population of the Ryedale district.[68] The new boundary was imposed after central government rejected the former city council's own proposal.

Parliament

From 1997 to 2010, the central part of the district was covered by the City of York constituency, while the remainder was split between the constituencies of Ryedale, Selby, and Vale of York.[69] These constituencies were represented by Hugh Bayley, John Greenway, John Grogan, and Anne McIntosh respectively.

Following their review in 2003 of parliamentary representation in North Yorkshire, the Boundary Commission for England recommended the creation of two new seats for the City of York, in time for the general election in 2010. These are York Central, which covers the inner urban area, and is entirely surrounded by the York Outer constituency.[70]

Ceremonial

York is within the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire and, until 1974, was within the jurisdiction of the Lord Lieutenant of the County of York, West Riding and the County of The City of York. The city does retain the right to appoint its own Sheriff. The holder of the Royal dukedom of York has no responsibilities either ceremonially or administratively as regards to the city.

Geography

Location

| Place | Distance | Direction | Relation |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 174 miles (280 km)[71] | South-east | Capital |

| Lincoln | 55 miles (89 km)[72] | South-east | Next nearest historic county town |

| Middlesbrough | 43 miles (69 km)[73] | North | Largest place in the county |

| Ripon | 22 miles (35 km)[74] | North-west | Next nearest city |

| Leeds | 22 miles (35 km)[75] | South-west | Next nearest city |

York lies in the Vale of York, a flat area of fertile arable land bordered by the Pennines, the North York Moors and the Yorkshire Wolds. The city was built at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss on a terminal moraine left by the last ice age.[76]

During Roman times, the land surrounding the Ouse and Foss was marshy, making the site easy to defend. The city is prone to flooding from the River Ouse, and has an extensive network of flood defences with walls along the river, and a liftable barrier across the Foss where it joins the Ouse at the "Blue Bridge". In October and November 2000, York experienced the worst flooding in 375 years; more than 300 homes were flooded.[77] In December 2015 the flooding was more extensive and caused major disruption.[78] The extreme impact led to a personal visit by Prime Minister David Cameron.[79] Much land in and around the city is on flood plains too flood-prone for development other than agriculture. The ings are flood meadows along the Ouse, while the strays are open common grassland in various locations around the city.

Climate

York has a temperate climate (Cfb) with four distinct seasons. As with the rest of the Vale of York, the city's climate is drier and warmer than the rest of the Yorkshire and the Humber region. Owing to its lowland location, York is prone to frosts, fog, and cold winds during winter, spring, and very early summer.[80] Snow can fall in winter from December onwards to as late as April but quickly melts. As with much of the British Isles, the weather is changeable. York experiences most sunshine from May to July, an average of six hours per day.[81] With its inland location, summers are often warmer than the Yorkshire coast with temperatures of 27 °C or more. Extremes recorded at the University of York campus between 1998 and 2010 include a highest temperature of 34.5 °C (94.1 °F)[when?] and a lowest temperature of −16.3 °C (2.7 °F) on 6 December 2010. The most rainfall in one day was 88.4 millimetres (3.5 in).[82]

| Climate data for RAF Linton-on-Ouse, 15 km north-west of York | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16 (61) |

17 (63) |

22 (72) |

25 (77) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

40.2 (104.4) |

34 (93) |

32 (90) |

29 (84) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16 (3) |

−10 (14) |

−13 (9) |

−3 (27) |

1 (34) |

2 (36) |

5 (41) |

5 (41) |

−1 (30) |

−4 (25) |

−8 (18) |

−16 (3) |

−16 (3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 52.7 (2.07) |

39.9 (1.57) |

44.9 (1.77) |

50.1 (1.97) |

43.8 (1.72) |

58.0 (2.28) |

53.2 (2.09) |

62.4 (2.46) |

46.9 (1.85) |

57.7 (2.27) |

57.8 (2.28) |

55.8 (2.20) |

626.0 (24.65) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.1 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 10.4 | 11.3 | 10.7 | 117.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40 | 60 | 100 | 141 | 190 | 220 | 230 | 205 | 156 | 105 | 65 | 47 | 1,550 |

| Source 1: Met Office[83] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: BBC Weather[84] | |||||||||||||

Green belt

York's urbanised areas are surrounded by a green belt that restricts development in the rural areas and parts of surrounding villages,[85] to preserve the setting and historic character of the city.[86] The green belt surrounds nearly all of the city and its outer villages, extending out into North Yorkshire.

Demography

The York urban area (built-up area) had a population of 153,717 at the time of the 2011 UK census,[87] compared with 137,505 in 2001.[88] The population of the City of York (Local Authority) was 198,051 and its ethnic composition was 94.3% White, 1.2% Mixed, 3.4% Asian and 0.6% Black. York's elderly population (those 65 and over) was 16.9%, however only 13.2% were listed as retired.[89]

This section needs to be updated. (November 2018) |

Also at the time of the 2001 UK census, the City of York had a total population of 181,094 of whom 93,957 were female and 87,137 were male. Of the 76,920 households in York, 36.0% were married couples living together, 31.3% were one-person households, 8.7% were co-habiting couples and 8.0% were lone parents. The figures for lone parent households were below the national average of 9.5%, and the percentage of married couples was also close to the national average of 36.5%; the proportion of one person households was slightly higher than the national average of 30.1%.[90]

In 2001, the population density was 4,368/km2 (11,310/sq mi).[88] Of those aged 16–74 in York, 24.6% had no academic qualifications, a little lower than 28.9% in all of England. Of York's residents, 5.1% were born outside the United Kingdom, significantly lower than the national average of 9.2%. White British form 95% of the population; the largest single minority group was recorded as Asian, at 1.9% of the population.

The number of theft-from-a-vehicle offences and theft of a vehicle per 1,000 of the population was 8.8 and 2.7, compared to the English national average of 6.9 and 2.7 respectively.[91] The number of sexual offences was 0.9, in line with the national average.[91] The national average of violence against another person was 16.2 compared to the York average of 17.5.[91] The figures for crime statistics were all recorded during the 2006–07 financial year.

The city's estimated population in 2019 was 210,620.[92]

Population change

| Population growth in York since 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1941[a] | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001[b] | 2011 | |

| Population | 24,080 | 27,486 | 30,913 | 36,340 | 40,337 | 49,899 | 58,632 | 67,364 | 76,097 | 81,802 | 90,665 | 100,487 | 106,278 | 112,402 | 123,227 | 135,093 | 144,585 | 154,749 | 158,170 | 172,847 | 181,131 | 198,051 | |

| Source: Vision of Britain[93] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnicity

| Ethnic Group | Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991[94] | 2001[95] | 2011[96] | 2021[97] | |||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 165,118 | 99% | 177,191 | 97.8% | 186,731 | 94.2% | 188,167 | 92.8% |

| White: British | – | – | 172,237 | 95.1% | 178,613 | 90.1% | 176,963 | 87.3% |

| White: Irish | – | – | 1,217 | 1,103 | 1,317 | 0.6% | ||

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | 269 | 368 | 0.2% | |||

| White: Roma | 222 | 0.1% | ||||||

| White: Other | – | – | 3,737 | 6,746 | 9,297 | 4.6% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Total | 952 | 0.6% | 2,027 | 1.1% | 6,740 | 3.4% | 7,634 | 3.8% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | 237 | 542 | 1,531 | 1,853 | 0.9% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | 68 | 201 | 417 | 545 | 0.3% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | 133 | 364 | 370 | 413 | 0.2% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | 318 | 642 | 2,449 | 2,889 | 1.4% | |||

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | 196 | 278 | 1,973 | 1,934 | 1.0% | |||

| Black or Black British: Total | 304 | 0.2% | 341 | 0.2% | 1,194 | 0.6% | 1,325 | 0.7% |

| Black or Black British: African | 113 | 164 | 903 | 978 | 0.5% | |||

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | 104 | 143 | 205 | 208 | 0.1% | |||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | 87 | 34 | 86 | 139 | 0.1% | |||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | 1,144 | 0.6% | 2,410 | 1.2% | 3,741 | 1.8% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | 248 | 529 | 631 | 0.3% | ||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | 114 | 305 | 494 | 0.2% | ||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | 456 | 873 | 1,579 | 0.8% | ||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | 326 | 703 | 1,037 | 0.5% | ||

| Other: Total | 439 | 0.2% | 973 | 1,954 | 1% | |||

| Other: Arab | – | – | 498 | 623 | 0.3% | |||

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 439 | 0.2% | 391 | 475 | 1,331 | 0.7% | ||

| Total | 166,813 | 100% | 181,094 | 100% | 198,051 | 100% | 202,821 | 100% |

Religion

Percentages in York following non-Christian religion were below England's national average. Classified as having "No Religion" is higher than the national average. Christianity has the largest religious following in York, 59.5% residents reported as Christian in the 2011 census.

York has multiple churches, most present churches in York are from the medieval period. St William's College behind the Minster, and Bedern Hall, off Goodramgate, are former dwelling places of the canons of the York Minster.[98]

There are 33 active Anglican churches in York, which is home to the Archbishop of York and York Minster, the Mother Church and administrative centre of the northern province of the Church of England and the Diocese of York.[99] York is in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Middlesbrough, has eight Roman Catholic churches and a number of different Catholic religious orders.[100]

Leaders of different Christian denominations work together across the city, forming a network of churches known as One Voice York.[101] Other Christian denominations active in York include the Religious Society of Friends who have three meeting houses,[102] Methodists (the York Circuit of The Methodist Church York and Hull District),[103] and Unitarians. St Columba's United Reformed Church in Priory Street, originally built for the Presbyterians, dates from 1879.[104] York's only Mosque is located in the Layerthorpe area, and the city also has a UK Islamic Mission centre.[105] Various Buddhist traditions are represented in the city and around York.[106] There is also an active Jewish community.[107]

| Religion | 2001[108] | 2011[109] | 2021[110] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| No religion | 30,003 | 16.6 | 59,646 | 30.1 | 93,577 | 46.1 |

| Holds religious beliefs | 137,377 | 75.9 | 123,009 | 62.1 | 95,314 | 47.0 |

| 134,771 | 74.4 | 117,856 | 59.5 | 89,019 | 43.9 | |

| 388 | 0.2 | 1,016 | 0.5 | 1,045 | 0.5 | |

| 347 | 0.2 | 983 | 0.5 | 1,043 | 0.5 | |

| 191 | 0.1 | 202 | 0.1 | 273 | 0.1 | |

| 1,047 | 0.6 | 2,072 | 1.0 | 2,488 | 1.2 | |

| 95 | 0.1 | 133 | 0.1 | 179 | 0.1 | |

| Other religion | 538 | 0.3 | 747 | 0.4 | 1,266 | 0.6 |

| Religion not stated | 13,714 | 7.6 | 15,396 | 7.8 | 13,930 | 6.9 |

| Total population | 181,094 | 100.0 | 198,051 | 100.0 | 202,821 | 100.0 |

Economy

Overview

A July 2020 report by Council stated that York is worth "£5.2 billion to the UK economy ... with 9,000 businesses and 110,000 people employed across the city".[111] According to Make It York, the city benefits from features that include a well-educated workforce, "excellent transport links to both national and international markets, pronounced strengths in a range of high value sectors, a pioneering digital infrastructure, outstanding business support networks ...".[112]

York's economy is based on the service industry, which in 2000 was responsible for 88.7% of employment in the city.[113]

Statistics based on 2019 data indicated that tourism was worth over £765 million to the city, supported 24,000 jobs and attracted 8.4 million visitors each year.[114]

The Employment Rate in 2018 was 78.8%. The private sector accounted for 77,000 jobs in 2019 while 34,500 jobs were in the public sector.[92]

The service industries include public sector employment, health, education, finance, information technology (IT) and tourism that accounted for 10.7% of employment as of 2016. Tourism has become an important element of the economy, with the city offering a wealth of historic attractions, of which York Minster is the most prominent, and a variety of cultural activities. As a holiday destination York was the 6th most visited English city by UK residents (2014–16)[115] and the 13th most visited by overseas visitors (2016).[116]

A 2014 report, based on 2012 data,[117] stated that the city receives 6.9 million visitors annually; they contribute £564 million to the economy and support over 19,000 jobs.[118] In the 2017 Condé Nast Traveller survey of readers, York rated 12th among The 15 Best Cities in the UK for visitors.[119] In a 2020 Condé Nast Traveller report, York rated as the sixth best among ten "urban destinations [in the UK] that scored the highest marks when it comes to ... nightlife, restaurants, and friendliness".[120]

Unemployment in York was low at 4.2% in 2008 compared to the United Kingdom national average of 5.3%.[113] The biggest employer in York is the City of York Council, with over 7,500 employees. Employers with more than 2,000 staff include Aviva (formerly Norwich Union Life), Network Rail, Northern Trains, York Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of York. Other major employers include BT Group, CPP Group, Nestlé, NFU Mutual and a number of railway companies.[121][122]

A 2007 report stated that the economic position at that time very different from the 1950s, when its prosperity was based on chocolate manufacturing and the railways. This position continued until the early 1980s when 30% of the workforce were employed by just five employers and 75% of manufacturing jobs were in four companies.[123] Most industry around the railway has gone, including the York Carriage Works, which at its height in the 1880s employed 5,500 people, but closed in the mid-1990s.[123][124] York is the headquarters of the confectionery manufacturer Nestlé York (formerly Nestlé Rowntrees) and home to the KitKat and eponymous Yorkie bar chocolate brands. Terry's chocolate factory, makers of the Chocolate Orange, was located in the city; but it closed on 30 September 2005, when production was moved by its owners, Kraft Foods, to Poland. The historic factory building is situated next to the Knavesmire racecourse.

On 20 September 2006, Nestlé announced that it would cut 645 jobs at the Rowntree's chocolate factory in York.[125] This came after a number of other job losses in the city at Aviva, British Sugar, and Terry's chocolate factory.[126] Despite this, the employment situation in York remained fairly buoyant until the effects of the late 2000s recession began to be felt.[127]

Since the closure of the carriage works, the site has been developed into offices. York's economy has been developing in the areas of science, technology and the creative industries. The city became a founding National Science City with the creation of a science park near the University of York.[128] Between 1998 and 2008 York gained 80 new technology companies and 2,800 new jobs in the sector.[129][130]

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic was confirmed to have reached England after cases were discovered in York on 31 January 2020.[131][132] The pandemic caused an economic slowdown because of restrictions imposed on businesses and on travel in the UK; by January 2021, many cities were in their third lockdown and the country's unemployment rate had reached its highest level in over four years.[133][134] The retail, hospitality, and tourism sectors were especially hard hit in York.[135] In August 2020, the campaign "Make It York" and the city council embarked on a six-month tourism marketing plan "to reenergise the city while building resident and visitor confidence".[114]

A report in June 2020 stated that unemployment had risen 114% over the previous year because of restrictions imposed as a result of the pandemic.[136] In addition to high unemployment during lockdown periods, one analysis by the York and North Yorkshire Local Enterprise Partnership predicted in August 2020 that "as many as 13,835 jobs in York will be lost in the scenario considered most likely, taking the city's unemployment rate to 14.5%". Some critics claimed that part of the problem was caused by "over-reliance on the booming tourism industry at the expense of a long-term economic plan".[135] Other analyses suggested that "York is well-placed for the high street to recover and evolve from the pandemic if new businesses focus on creating an attraction or experience rather than traditional retail". The North Yorkshire Local Enterprise Partnership also "predicted a significant rise in staycation trips to York in 2021".[137]

Public services

Under the requirements of the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, York City Council appointed a watch committee which established a police force and appointed a chief constable.[138] On 1 June 1968 the York City, East Riding of Yorkshire, and North Riding of Yorkshire police forces were amalgamated to form the York and North East Yorkshire Police. Since 1974, Home Office policing in York has been provided by the North Yorkshire Police. The force's central headquarters for policing York and nearby Selby are in Fulford.[139] Statutory emergency fire and rescue service is provided by the North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Service, based in Northallerton.[140]

The city's first hospital, York County Hospital, opened in 1740 in Monkgate[141] funded by public subscription. It closed in 1976 when it was replaced by York Hospital, which opened the same year and gained Foundation status in April 2007. It has 524 adult inpatient beds and 127 special purpose beds providing general healthcare and some specialist inpatient, daycase, and outpatient services.[142] It is also known as York District Hospital and YDH.[142]

The Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust was formed on 1 July 2006 bringing together South Yorkshire Ambulance Service, West Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service and the North and East Yorkshire parts of Tees, East and North Yorkshire Ambulance Service to provide patient transport.[143] Other forms of health care are provided for locally by clinics and surgeries.

Since 1998 waste management has been co-ordinated via the York and North Yorkshire Waste Partnership.[144] York's distribution network operator for electricity is CE Electric UK;[145] there are no power stations in the city. Yorkshire Water, which has a local water extraction plant on the River Derwent at Elvington, manages York's drinking and waste water.[146]

The city has a magistrates' court,[147] and venues for the Crown Court[148] and the County Court.[149] York Crown Court was designed by the architect John Carr, and built next to the then prison (including execution area).[150]

Between 1773 and 1777, the Grand Jury House was replaced by John Carr's elegant Court House for the Assizes of the whole county. The Female Prison was built opposite and mirrors the court building positioned around a circular lawn which became known as the "Eye of the Ridings", or the "Eye of York".

1776 saw the last recorded instance of a wife hanged and burnt for poisoning her husband. Horse theft was a capital offence. The culprits of lesser crimes were brought to court by the city constables and would face a fine. The corporation employed a "common informer" whose task was to bring criminals to justice.[151]

The former prison is now the Castle Museum but still contains the cells.

Transport

Water

York's location on the River Ouse, and in the centre of the Vale of York, means that it has always had a significant position in the nation's transport system.[31] The city grew up as a river port at the confluence of the Ouse and the Foss. The Ouse was originally a tidal river, accessible to seagoing ships of the time. Today, both of these rivers remain navigable, although the Foss is only navigable for a short distance above the confluence. A lock at Naburn on the Ouse to the south of York means that the river in York is no longer tidal.[152]

Until the end of the 20th century, the Ouse was used by barges to carry freight between York and the port of Hull. The last significant such traffic was the supply of newsprint to the local newspaper's Foss-side print works, which continued until 1997. Today, navigation is almost exclusively leisure-oriented.

Roads

Like most cities founded by the Romans, York is well served by long-distance trunk roads. The city lies at the intersection of the A19 road from Doncaster to Tyneside, the A59 road from Liverpool to York, the A64 road from Leeds to Scarborough and the A1079 road from York to Hull. The A64 road provides the principal link to the motorway network, linking York to both the A1(M) and the M1 motorways at a distance of about 10 miles (15 km) from the city. The trans-Pennine M62 motorway is less than 20 miles (30 km) away providing links to Manchester and Liverpool. The city is surrounded on all sides by an outer ring road, at a distance of some 3 miles (5 km) from the centre of the city, which allows through traffic to by-pass the city. The street plan of the historic core of the city dates from medieval times and is not suitable for modern traffic. As a consequence, many of the routes inside the city walls are designated as car-free during business hours or restrict traffic entirely. To alleviate this situation, six bus-based park and ride sites operate in York. The sites are located towards the edge of the urban area, with easy access from the ring road and allow out of town visitors to complete their journey into the city centre by bus.[153]

Public transport within the city is largely bus-based. First York operates the majority of the city's local bus services, as well as the York park and ride services. York was the location of the first implementation of FirstGroup's experimental and controversial FTR bus concept, which sought to confer the advantages of a modern tramway system at a lower cost.[154] The service was withdrawn following an election manifesto pledge by the Labour Group at the 2011 local government election.[155] Transdev York also operates a large number of local bus services. Open-top tourist and sightseeing buses are operated by Transdev York, on behalf of City Sightseeing and York Pullman on behalf of Golden Tours.

Rural services, linking local towns and villages with York, are provided by a number of companies with Transdev York & Country, East Yorkshire and Reliance Motor Services operating most of them.[156] Longer-distance bus services are provided by a number of operators, including Arriva Yorkshire services to Selby, East Yorkshire services to Hull, Beverley, Market Weighton and Pocklington, and Transdev York & Country services to Boroughbridge, Knaresborough, Harrogate, Castle Howard and Malton. Yorkshire Coastliner links Leeds & York with Scarborough, Malton, Pickering and Whitby.[157]

Railway

York has been a major railway centre since the first line arrived in 1839, at the beginning of the railway age. For many years, the city hosted the headquarters and works of the North Eastern Railway.[41]

Air

The closest international airports are Leeds Bradford at 30 miles (48 km), Teesside 47 miles (76 km), Doncaster Sheffield 49 miles (79 km), Humberside 54 miles (87 km). Further afield are Manchester 84 miles (135 km) and Newcastle 95 miles (153 km).

Manchester Airport – with connections to Europe, North America, Africa and Asia – has direct rail links by TransPennine Express with its namesake station.[158] By road its accessible by the A64 to the M60 via the A1(M) motorway, M1 and M62.

Teesside Airport has one connection via Darlington and Eaglescliffe with a limited service with a bus from its station to the airport. By road, it is accessible by the A19 north to the A67. Newcastle Airport has one connection via Newcastle with the metro to Newcastle Airport, it is accessible by the A1(M) north to the A1 then the A696.

Leeds Bradford and Humberside have no direct station with buses from the nearest stations. Leeds Bradford serves most major European and North African airports, as well as Pakistan and New York City.[159] Humberside is accessible by the A1079 to the A15 via the A63; Leeds Bradford by the A59 to the A658 via the A661.[160]

York has an airfield at the former RAF Elvington, 7 miles (11 km) south-east of the city centre, which is the home of the Yorkshire Air Museum and used for private aviation. In 2003, plans were drafted to expand the site for business aviation or a full commercial service.[161] Former RAF Church Fenton is also near the city and private, it is now called Leeds East.

Education

Institutions

York Castle, a complex of buildings ranging from the medieval Clifford's Tower to the 20th-century entrance to the York Castle Museum (formerly a prison) has had a chequered history. As well as the Castle Museum, the city contains numerous other museums and historic buildings such as the Yorkshire Museum and its Museum Gardens, Jorvik Viking Centre, York Art Gallery, Merchant Adventurers' Hall, the reconstructed medieval house Barley Hall (owned by the York Archaeological Trust), the 18th-century Fairfax House, the Mansion House (the historic home of the Lord Mayor) and the so-called Treasurer's House (owned by the National Trust).[162] The National Railway Museum is situated just beyond the station, and is home to a vast range of transport material and the largest collection of railway locomotives in the world. Included in this collection are the world's fastest steam locomotive LNER Class A4 4468 Mallard and the world-famous LNER Class A3 4472 Flying Scotsman, which has been overhauled in the Museum.[163] Although noted for its Medieval history, visitors can also gain an understanding of the Cold War through visiting the York Cold War Bunker, former headquarters of No 20 Group of the Royal Observer Corps.[164]

The city's first subscription library opened in 1794.[165] The first free public library, the York Library, was built on Clifford Street in 1893, to mark Queen Victoria's jubilee. A new building was erected on Museum Street in 1927, and this is still the library today; it was extended in 1934 and 1938.[166]

Higher and further

The University of York's main campus is on the southern edge of the city at Heslington. The Department of Archaeology and the graduate Centres for Eighteenth Century Studies and Medieval Studies are located in the historic King's Manor in the city centre.[167]

It was York's only institution with university status until 2006, when the more centrally located York St John University, formerly an autonomous college of the University of Leeds, attained full university status. The city formerly hosted a branch of the University of Law before it moved to Leeds. The University of York also has a medical school, Hull York Medical School.[168]

The city has two major further education institutions. York College is an amalgamation of York Technical College and York Sixth Form College. Students there study a very wide range of academic and vocational courses, and range from school leavers and sixth formers to people training to make career moves.[169] Askham Bryan College offers further education courses, foundation and honours degrees, specialising in more vocational subjects such as horticulture, agriculture, animal management and even golf course management.[170]

Secondary and primary

There are 70 local council schools with over 24,000 pupils in the City of York Council area.[171] The City of York Council manages most primary and secondary schools within the city.

This article needs to be updated. (July 2022) |

Primary schools cover education from ages 5–11, with some offering early years education from age 3. From 11 to 16 education is provided by 10 secondary schools, four of which offer additional education up to the age of 18.[172] In 2007 Oaklands Sports College and Lowfield Comprehensive School merged to become one school known as York High School.[173]

There is one "outstanding"[174] Roman Catholic secondary school in the city, All Saints School, which was founded in 1665, the school is split-site meaning that the education of lower years (years 7–9) happens on the Lower Site attached to the oldest running convent in the country, Bar Convent. And the upper years including sixth form are taught on the Upper Site which is on Mill Mount, the former site of Mill Mount County Grammar School for Girls. The Sixth form is the largest sixth form in the city. As a school it plays an essential role in York's Catholic community being the only secondary institution dedicated to the denomination. It was the first Catholic school in the country to admit girls for education in the 1660s.

York also has several private schools. St Peter's School was founded in 627. The scholar Alcuin, who went on to serve Charlemagne, taught there.[175] It was also the school attended by Guy Fawkes.[176]

Two schools have Quaker origins: Bootham School is co-educational[177] and The Mount School is all-girls.[178] Another all-girls school is Queen Margaret's School, which was established under the Woodard Foundation.

Culture

The city is part of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network as a city of Media Arts. An unsuccessful 2010 bid by York city council and a number of heritage organisations to make a UNESCO World Heritage Site indirectly led to the city making a successful bid for its title.[179][180][181]

Theatre

The Theatre Royal, which was established in 1744, produces an annual pantomime which attracts loyal audiences from around the country. The theatre's veteran star, Berwick Kaler, often played the dame, before he retired from acting in the pantomime in 2019,[182] and officially parted ways with the theatre after the so-called "Panto Wars".[183] The Theatre Royal continues to produce an annual pantomime without Kaler, who came out of retirement in 2021 to star in a new panto at The Grand Opera House.[184] Both the Grand Opera House and Joseph Rowntree Theatre also offer a variety of productions.[185][186] The city is home to the Riding Lights Theatre Company, which as well as operating a busy national touring department, also operates a busy youth theatre and educational departments. York is also home to a number of amateur dramatic groups.[187] The Department of Theatre, Film and Television and Student Societies of the University of York put on public drama performances.[188]

The York Mystery Plays are performed in public at intervals, using texts based on the original medieval plays of this type that were performed by the guilds – often with specific connections to the subject matter of each play. (For instance the Shipwrights' Play is the Building of Noah's Ark and the fish-sellers and mariners the Landing of Noah's Ark).[189] The York Cycle of Mystery Plays or Pageants is the most complete in England. Originally performed from wagons at various locations around the city from the 14th century until 1570, they were revived in 1951 during the Festival of Britain, when York was one of the cities with a regional festival.[190] They became part of the York City Festival every three years and later four years. They were mostly produced in a temporary open-air theatre within the ruins of St Mary's Abbey, using some professional but mostly amateur actors. Lead actors have included Christopher Timothy and Robson Green (in the role of Christ) and Dame Judi Dench as a school girl, in 1951, 1954 and 1957. (She remains a Patron of the plays). The cycle was presented in the Theatre Royal in 1992 and 1996, within York Minster in 2000 and in 2002, 2006 and 2010 by Guild groups from wagons in the squares, in the Dean's Park, or at the Eye of York.[191] They go around the streets, recreating the original productions. In 2012, the York Mystery Plays were performed between 2 and 27 August at St Mary's Abbey in the York Museum Gardens.[192]

Music

The Academy of St Olave's, a chamber orchestra which gives concerts in St Olave's Church, Marygate, is one of the music groups that perform regularly in York.[193] A former church, St Margaret's, Walmgate, is the National Centre for Early Music, which hosts concerts, broadcasts, competitions and events including the York Early Music Festival.[194][195] Students, staff and visiting artists of York St John University music department regularly perform lunchtime concerts in the university chapel. The staff and students of the University of York also perform in the city.[196]

Food and drink

Each September since 1997, York has held an annual Festival of Food and Drink. The aim of the festival is to spotlight food culture in York and North Yorkshire by promoting local food production. The Festival attracts up to 150,000 visitors over 10 days from all over the country.[197]

The Assize of Ale is an annual event in the city where people in medieval costume take part in a pub crawl to raise money for local charities. It has its origins in the 13th century, when an Assize of Bread and Ale was used to regulate the quality of goods. The current version was resurrected in 1990/91 by the then Sheriff of York, Peter Brown, and is led by the Guild of Scriveners.[198]

The Knavesmire, home of York Racecourse, plays host to Yorkshire's largest beer festival every September run by York CAMRA – York Beer & Cider Festival.[199] It is housed in a marquee opposite the grandstand of the racecourse in the enclosure and in 2016 offered over 450 real ales and over 100 ciders.[200]

A product claimed to be local is York ham,[201] a mild-flavoured ham with delicate pink colouring. It is traditionally served with Madeira Sauce.[202][203] The ham has been described as a lightly smoked, dry-cured ham that is saltier but milder in flavour than other European dry-cured hams.[204] Folklore has it that the oak construction for York Minster provided the sawdust for smoking the ham.[205] A likely apocryphal story attributes Robert Burrow Atkinson's butchery shop, in Blossom Street, to be the birthplace of the original "York Ham", or at least to have made it famous.[206]

Attractions

Architecture

York Minster, a large Gothic cathedral, dominates the city.

York's centre is enclosed by the city's medieval walls, which are a popular walk.[207][208] These defences are the most complete in England. They have the only walls set on high ramparts and they retain all their principal gateways.[209] They incorporate part of the walls of the Roman fortress and some Norman and medieval work, as well as 19th- and 20th-century renovations.[210]

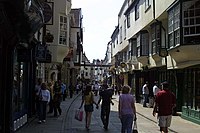

The entire circuit is approximately 2.5 miles (4 km), and encloses an area of 263 acres (106 ha).[211] The north-east section includes a part where walls never existed, because the Norman moat of York Castle, formed by damming the River Foss, also created a lake which acted as a city defence. This lake was later called the King's Fishpond, as the rights to fish belonged to the Crown. A feature of central York is the Snickelways, narrow pedestrian routes, many of which led towards the former market-places in Pavement and St Sampson's Square.[212] The Shambles is a narrow medieval street, lined with shops, boutiques and tea rooms. Its unusual name comes from an old English term for an open-air slaughterhouse or meat market.[213] Most of these premises were once butchers' shops, and the hooks from which carcasses were hung and the shelves on which meat was laid out can still be seen outside some of them. The street also contains the Shrine of Margaret Clitherow, although it is not located in the house where she lived.[214] Goodramgate has many medieval houses including the early-14th‑century Lady Row built to finance a Chantry, at the edge of the churchyard of Holy Trinity church.

-

The southern entrance to York, Micklegate Bar, is a 12th–14th century structure.

-

The Shambles is a medieval shopping street; most of the buildings date from between c. 1350 and 1475.

-

The Art Deco style Odeon Cinema on Blossom Street

-

The 1960s Brutalist-style Stonebow House

Pubs

In June 2015 York CAMRA listed 101 pubs on its map of the city centre, some of which are hundreds of years old.[215] These include the Golden Fleece, Ye Olde Starre Inne, noted for its sign which has spanned the street since 1733,[216] and The Kings Arms, often photographed during floods.[217] On 18 June 2016, York CAMRA undertook a "Beer Census" and found 328 unique real ales being served in over 200 pubs in York, reinforcing the city's reputation as a top UK beer destination.[218]

Tea Rooms

In the centre of York, in St Helen's Square, there is the York branch of Bettys Café Tea Rooms. Bettys' founder, Frederick Belmont, travelled on the maiden voyage of the Queen Mary in 1936. He was so impressed by the splendour of the ship that he employed the Queen Mary's designers and craftsmen to turn a dilapidated furniture store in York into an elegant café in St Helen's Square. A few years after Bettys opened in York war broke out, and the basement 'Bettys Bar' became a favourite haunt of the thousands of airmen stationed around York. 'Bettys Mirror', on which many of them engraved their signatures with a diamond pen, remains on display today as a tribute to them.[219]

Media

The York area is served by a local newspaper, The Press (known as the Evening Press until April 2006), The York Advertiser newspaper (based at The Press on Walmgate), and four local radio stations: BBC Radio York, YorkMix Radio, YO1 Radio and Jorvik Radio. A local commercial radio station, Minster FM, broadcast until 2020 when it was replaced by Greatest Hits Radio York and North Yorkshire.[220][221][222][223][224][225] Another digital news and radio website is YorkMix run by former print journalists, that incorporates Local News; What's On; Food & Drink; Things To Do and Business sections with articles written by residents and local journalists.[226] In August 2016 YorkMix was nominated in two categories in the O2 Media Awards for Yorkshire and The Humber.[227]

Local news and television programmes are provided by BBC Yorkshire and BBC North East and Cumbria on BBC One and ITV Yorkshire and ITV Tyne Tees on ITV. Television signals are received from either the Emley Moor or Bilsdale transmitters. [228][229]

On 27 November 2013, Ofcom awarded the 12-year local TV licence for the York area to a consortium entitled The York Channel, with the channel due to be on air in spring 2015.[230] This service is now on air as That's TV North Yorkshire.[231]

York St John University has a Film and Television Production department with links to many major industrial partners. The department hosts an annual festival of student work and a showcase of other regional films.[232]

The University of York has its own television station York Student Television (YSTV) and two campus newspapers Nouse and York Vision.[233] Its radio station URY is the longest running legal independent radio station in the UK, and was voted Student Radio Station of the Year 2020 at the Student Radio Awards.[234]

Sport

Football codes

The city's association football team is York City who are competing in the National League as of the 2023–24 season. York have played as high as the old Second Division but are best known for their 'giant killing' status in cup competitions, having reached the FA Cup semi-final in 1955 and beaten Manchester United 3–0 during the 1995–96 League Cup. Their matches are played at the York Community Stadium as of 2021,[235] having previously played at Bootham Crescent since 1932. The most notable footballers to come from York in recent years are Lucy Staniforth,[236] Under-20 World Cup winning captain Lewis Cook[237] and former England manager Steve McClaren.[238]

York also has a strong rugby league history. York FC, later known as York Wasps, formed in 1868, were one of the oldest rugby league clubs in the country but the effects of a move to the out of town Huntington Stadium, poor results and falling attendances led to their bankruptcy in 2002.[239] The supporters formed a new club, York City Knights, who played at the same stadium until 2015 when they moved to Bootham Crescent. In 2021, they moved to York Community Stadium.[240] In 2022, the club was renamed York RLFC[241] and as of 2023[update] the men's team (York Knights) play in The Championship[242] and the women's team (York Valkyrie) play in the Super League.[243] There are three amateur rugby league teams in York; New Earswick All Blacks (in New Earswick), York Acorn and Heworth. York International 9s was an annual rugby league nines tournament which took place in York between 2002 and 2009.[244] Amateur side York Lokomotive compete in the Rugby League Conference.[citation needed]

Rugby union has been played in York since the 1860s, with multiple teams currently playing within the city. York RUFC was formed in 1928, and amalgamated with the York Cricket Club in 1966. The teams' home ground is at York sports ground at Clifton Park. The men's 1st team play in North 1 East, with the women's team in RFUW Women's NC1 North East championship.[245] York Railway Institute (RI) RUFC home ground is at the York RI sports club on newlane, York. The men's team currently compete in Yorkshire Division 4 South East (Yorkshire 4), and the ladies team play in the RFUW Women's NC1 North East championship.[246] Based at the York site of chocolate and confectionery maker Nestle Rowntree's, Nestle Rowntree RUFC was founded originally in 1894 and re-founded in 1954. They currently play their home games at York St. John University Sports Field and they compete in Yorkshire Division 4 South East (Yorkshire 4).[247]

Racing

York Racecourse was established in 1731 and from 1990 has been awarded Northern Racecourse of the Year for 17 years running. This major horseracing venue is located on the Knavesmire and sees thousands flocking to the city every year for the 15 race meetings. The Knavesmire Racecourse also hosted Royal Ascot in 2005.[248] In August racing takes place over the four-day Ebor Festival that includes the Ebor Handicap dating from 1843.[249]

On 6 July 2014, York hosted the start of Stage 2 of the 2014 Tour de France. Starting the Départ Fictif from York Racecourse, the riders travelled through the city centre to the Départ Actuel on the A59 just beyond the junction with the Outer Ring Road heading towards Knaresborough.[250] In 2015, the inaugural Tour de Yorkshire was held as a legacy event to build on the popularity of the previous year, with the Day 2 stage finishing in York.[251]

Motorbike speedway once took place at York. The track in the Burnholme Estate was completed in 1930 and a demonstration event staged. In 1931 the track staged team and open events and the York team took part in the National Trophy.[252]

Other

An open rowing club York City Rowing Club is located underneath Lendal Bridge.[253] The rowing clubs of The University of York, York St John University Rowing Club and Leeds University Boat Club as well as York City RC use the Ouse for training. There are two sailing clubs close to York, both of which sail dinghies on the River Ouse. The York RI (Railway Institute) Sailing Club has a club house and boat park on the outskirts of Bishopthorpe, a village3 miles (4.8 km) to the south of York. The Yorkshire Ouse Sailing Club has a club house in the village of Naburn,5 miles (8.0 km) south of York.

York hosts the UK Snooker Championship, which is the second biggest ranking tournament in the sport, at the York Barbican.

Garrison

York Garrison is a garrison of the British army, which administers a number of units based in and around the city of York.[254][255][256][257] The garrison's current units are:[258]

- York Station

- Imphal Barracks

- Headquarters, 1st (United Kingdom) Division

- 2 Signal Regiment, Royal Corps of Signals

- 12 Military Intelligence Company, 1 Military Intelligence Battalion

- 1 Investigation Company, Special Investigation Branch Regiment

- Kohima Troop, 50 (Northern) Signal Squadron, 37 Signal Regiment[259]

- 3 Army Education Centre, Educational and Training Services Branch

- Worsley Barracks[260]

- Helmand Company, 4th Battalion, Royal Yorkshire Regiment

- York Detachment, Leeds University Officers' Training Corps

- Yeomanry Barracks[261]

- A (Yorkshire Yeomanry) Squadron, Queen's Own Yeomanry

- Imphal Barracks

- Strensall Station

- Queen Elizabeth Barracks

- Headquarters, 2nd Medical Brigade

- 34 Field Hospital, Royal Army Medical Corps

- Headquarters, Army Training Unit (North)

- 4th Infantry Brigade Cadet Training Team

- 1st (United Kingdom) Division Operational Shooting Training Team

- Towthorpe Lines

- Army Medical Services Training Centre[262]

- Queen Elizabeth Barracks

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

York is twinned with:

Dijon, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France, since 1953[263]

Dijon, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, France, since 1953[263] Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1957[263][264]

Münster, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, since 1957[263][264] Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, since 2016[265][266]

Nanjing, Jiangsu, China, since 2016[265][266]

In 2016 York became sister cities with the Chinese city of Nanjing, in line with an agreement signed by the Lord Mayor of York, focusing on building links in tourism, education, science, technology and culture.[265][266][267][268]

On 22 October 2014 it announced the first 'temporal twinning' with Jórvík, the Viking city on the site of York from 866 to 1066.[269] In 2017 York became UK's first human rights city, which formalised the city's aim to use human rights in decision making.[270]

Freedom of the City

The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of York.

Individuals

- John Kendal: 1482.[271]

- John Moore: 29 September 1687.[271]

- Cosmo Gordon Lang: 1928.[272]

- HRH Princess Royal: 1952.[271]

- Edna Annie Crichton: 1955.[271]

- Prince Andrew, Duke of York: 23 February 1987[273] (revoked by a Unanimous vote of the City of York Council on 27 April 2022).[274]

- Sarah, Duchess of York: 23 February 1987.[275]

- Katharine, Duchess of Kent: April 1989.[271]

- John Barry: 2002.[271]

- Dame Judi Dench: 13 July 2002.[271][276]

- Berwick Kaler: 2003.[271]

- Professor Sir Ronald Cooke: 2006.[271]

- Neal Guppy: 2010.[277]

Military units

- The Royal Dragoon Guards: 24 April 1999.[278]

- 2 Signals Regiment: January 2001.[279]

- A Squadron The Queen's Own Yeomanry: 3 December 2009.[280]

- RAF Linton on Ouse: 19 September 2010.[281][282][283]

- The Queen's Gurkha Signals: 8 September 2015.[284][285]

Notable people

See also

- Big Blue Ocean Cleanup

- CityConnect WIFI

- The Evelyn collection of pictures of York from the early 20th century

- Southlands Methodist Church

- White Rose Theatre

- York Festival of Ideas

- York Shakespeare Project

- Goddards House and Garden

- Rollits LLP

- Rowntree Park

Explanatory notes

- a There was no census in 1941: figures are from National Register. United Kingdom and Isle of Man. Statistics of Population on 29 September 1939 by Sex, Age, and Marital Condition.

- b There is a discrepancy of 37 between Office for National Statistics figures (quoted before) and those on the Vision of Britain website (quoted here).

References

- ^ a b "Figure 1: Explore population characteristics of individual BUAs". Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Timeline". York Tourism Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "When sparks flew across the sky". The Press. Newsquest Media Group. 28 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "How the population changed in York, Census 2021 - ONS". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ a b Xavier Delamarre, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise, éditions errance 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions errance 1994, p. 39.

- ^ a b c "York's history". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 31 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ Wace, Robert. "Le Roman de Rou et des ducs de Normandie". BnF Gallica. p. 362. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

Li Barunz de Everwic Schire (the barons of Yorkshire)

- ^ Willis, Ronald (1988). The illustrated portrait of York (4th ed.). Robert Hale Limited. p. 35. ISBN 0-7090-3468-7.

- ^ "Ebor Festival". York City of Festivals. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ Geoffrey of Monmouth (1136). Historia Regum Britanniae. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "How to address the Archbishops of Canterbury and York – Forms of Address, Church of England, Religion". Debretts.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Willis, Ronald (1988). The illustrated portrait of York (4th ed.). Robert Hale Limited. pp. 26–27. ISBN 0-7090-3468-7.

- ^ a b Shannon, John; Tilbrook, Richard (1990). York – the second city. Jarrold Publishing. p. 2. ISBN 0-7117-0507-0.

- ^ "Lower (Britannia Inferior) and Upper Britain (Britannia Superior)". Vanderbilt University. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ^ Tillott, P. M., ed. (1961). "Before the Norman Conquest". A History of the County of York: the City of York. pp. 2–24. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2019 – via British History Online.

- ^ Russo, Daniel G. (1998). Town Origins and Development in Early England, c. 400–950 A.D. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 119–120. ISBN 978-0-313-30079-0.

- ^ Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990). An Atlas of Roman Britain. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007). p. 317. ISBN 978-1-84217-067-0. Cemeteries that are identifiably Anglian date from this period; some graves are within the Roman cemetery on The Mount.

- ^ "York history timeline". YorkHistory.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ "The First Minster: History of York". History of York. York Museums Trust. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b c "York Minster: a very brief history". York Minster. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Ritchie, Anna (1 July 2001). "Alcuin of York". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "From the raid on Lindisfarne to Harald Hardrada's defeat: 8 Viking dates you need to know". History Extra. BBC. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Jorvik: Viking York". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 13 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 927–929.

- ^ "The Old Baile". An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 2, the Defences. 1972. pp. 87–89. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2020 – via British History Online.

- ^ "The 1190 Massacre". History Of York. York Museums Trust. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ "Death in York". BBC. 28 September 2006. Archived from the original on 14 December 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Charter Day celebrations for York announced". BBC News. 8 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ^ "Norman and Medieval York". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ a b Tillott, P. M., ed. (1961). A History of the County of York: the City of York: The later middle ages – Communications, markets and merchants. British History Online. pp. 97–106. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b "The Age of Decline". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 4 February 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "Post-medieval York". Secrets Beneath Your Feet. York Archaeological Trust. 1998. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Ethel Carleton Williams, Anne of Denmark (London, 1970), p. 77.

- ^ "Transplanted Englishman brings country's Guy Fawkes party tradition to Burnsville". ThisWeek Online. ThisWeek Newspapers. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2005.

- ^ "Georgian York – social capital of the North". City of York Council. 22 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 February 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ Sources:

- Unwin, R. W. (1980). "V. Leeds becomes a transport centre". In Fraser, Derek (ed.). A History of modern Leeds. Manchester University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 0-7190-0747-X. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Armstrong, Alan (2005) [1974]. Stability And Change in an English County Town: A Social Study of York 1801–51. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–43. ISBN 9780521019873. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Lewis, Stephen (3 July 2009). "East Coast Main Line: York's part in the history of the railways". York Press. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- "George Hudson". SchoolNet. Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- ^ Rennison, Robert William (1996). Civil engineering heritage: Northern England. Thomas Telford. 5. York and North Yorkshire, pp.133.134. ISBN 9780727725189. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Industrialisation". www.historyofyork.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "History of Nestlé Rowntree". Nestlé UK Ltd. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 January 2008. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ a b "The Railway Age to the present day". City of York Council. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012.

- ^ Murray, Jill. "KNO/3/8: Transcript of 'Yorkshire Artists' by J W Knowles". explore York libraries and archives. pp. 112x, 113. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ "Records of Augustus Mahalski, Photographer". Archives Hub. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ "Luftwaffe pilot says sorry for bombing York". The Press. Newsquest Media Group. 17 April 2007. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "York Central Historic Core: Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). City of York Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ "History of the NRM". National Railway Museum. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul G. (2008). Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice (5 ed.). Thames & Hudson. p. 542. ISBN 9780500287194.

- ^ "York Dungeon celebrates 30th anniversary". York Press. 4 November 2016. Archived from the original on 19 January 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ "Founding students return to York 40 years on". University of York. 7 October 2003. Archived from the original on 9 November 2005. Retrieved 15 June 2009.