Avignon

Avignon | |

|---|---|

|

From top: Skyline, Rocher des Doms, Palais des Papes, Avignon Cathedral, Festival d'Avignon, Pont Saint-Bénézet | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur |

| Department | Vaucluse |

| Arrondissement | Avignon |

| Canton | Capital of 4 Cantons |

| Intercommunality | Grand Avignon |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2014—2020) | Cécile Helle (PS) |

| Area 1 | 64.78 km2 (25.01 sq mi) |

| Population (2011[1]) | 90,194 |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,600/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 84007 /84000 |

| Elevation | 10–122 m (33–400 ft) (avg. 23 m or 75 ft) |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 228 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19th Session) |

Avignon (French pronunciation: [a.vi.ɲɔ̃]; Template:Lang-la; Template:Lang-prv, Template:Lang-oc pronounced [aviˈɲun]) is a commune in south-eastern France in the department of Vaucluse on the left bank of the Rhône river. Of the 90,194 inhabitants of the city (as of 2011[update]), about 12,000 live in the ancient town centre enclosed by its medieval ramparts.

Between 1309 and 1377, during the Avignon Papacy, seven successive popes resided in Avignon and in 1348 Pope Clement VI bought the town from Joanna I of Naples. Papal control persisted until 1791 when, during the French Revolution, it became part of France. The town is now the capital of the Vaucluse department and one of the few French cities to have preserved its ramparts.

The historic centre, which includes the Palais des Papes, the cathedral, and the Pont d'Avignon, became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. The medieval monuments and the annual Festival d'Avignon have helped to make the town a major centre for tourism.

The commune has been awarded one flower by the National Council of Towns and Villages in Bloom in the Competition of cities and villages in Bloom.[2]

Toponymy

The earliest forms of the name were reported by the Greeks:[3]

- Аὐενιὼν = Auenion (Stephen of Byzantium, Strabo, IV, 1, 11)

- Άουεννίων = Aouennion (Ptolemy II, x).

The Roman name Avennĭo Cavarum (Mela, II, 575, Pliny III, 36), i.e. "Avignon of Cavares" accurately shows that Avignon was one of the three cities of the Celtic-Ligurian tribe of Cavares, along with Cavaillon and Orange.

The current name dates to a pre-Indo-European[3] or pre-Latin[4] theme ab-ên with the suffix -i-ōn(e)[3][4] This theme would be a hydronym - i.e. a name linked to the river (Rhône), but perhaps also an oronym of terrain (the Rocher des Doms).

The Auenion of the 1st century BC was Latinized to Avennĭo (or Avēnĭo), -ōnis in the 1st century and was written Avinhon in classic Occitan spelling[5] or Avignoun [aviɲũ] in Mistralian spelling[6] The inhabitants of the commune are called avinhonencs or avignounen in both Occitan and Provençal dialect.

History

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled History of Avignon. (Discuss) (November 2016) |

Prehistory

The site of Avignon has been occupied since the Neolithic period as shown by excavations at Rocher des Doms and the Balance district.[7]

In 1960 and 1961 excavations in the northern part of the Rocher des Doms directed by Sylvain Gagnière uncovered a small anthropomorphic stele (height: 20 cm), which was found in an area of land being reworked.[8] Carved in Burdigalian sandstone, it has the shape of a "tombstone" with its face engraved with a highly stylized human figure with no mouth and whose eyes are marked by small cavities. On the bottom, shifted slightly to the right is a deep indentation with eight radiating lines forming a solar representation - a unique discovery for this type of stele.

Compared to other similar solar figures[a] this stele representing the "first Avignonnais" and comes from the time period between the Copper Age and the Early Bronze Age which is called the southern Chalcolithic.[b]

This was confirmed by other findings made in this excavation near the large water reservoir on top of the rock where two polished greenstone axes were discovered, a lithic industry characteristic of "shepherds of the plateaux". There were also some Chalcolithic objects for adornment and an abundance of Hallstatt pottery shards which could have been native or imported (Ionian or Phocaean).

Antiquity

The name of the city dates back to around the 6th century BC. The first citation of Avignon (Aouen(n)ion) was made by Artemidorus of Ephesus. Although his book, The Journey, is lost it is known from the abstract by Marcian of Heraclea and The Ethnics, a dictionary of names of cities by Stephanus of Byzantium based on that book. He said: "The City of Massalia (Marseille), near the Rhone, the ethnic name (name from the inhabitants) is Avenionsios (Avenionensis) according to the local name (in Latin) and Auenionitès according to the Greek expression".[9] This name has two interpretations: "city of violent wind" or, more likely, "lord of the river".[citation needed][contradictory] Other sources trace its origin to the Gallic mignon ("marshes") and the Celtic definitive article.[10][contradictory]

Avignon was a simple Greek Emporium founded by Phocaeans from Marseille around 539 BC. It was in the 4th century BC that the Massaliotes (people from Marseilles) began to sign treaties of alliance with some cities in the Rhone valley including Avignon and Cavaillon. A century later Avignon was part of the "region of Massaliotes"[c] or "country of Massalia".[d]

Fortified on its rock, the city later became and long remained the capital of the Cavares.[11] With the arrival of the Roman legions in 120 BC. the Cavares, allies with the Massaliotes, became Roman. Under the domination of the Roman Empire, Aouenion became Avennio and was now part of Gallia Narbonensis (118 BC.), the first Transalpine province of the Roman Empire. Very little from this period remains (a few fragments of the forum near Rue Molière). It later became part of the 2nd Viennoise. Avignon remained a "federated city" with Marseille until the conquest of Marseille by Trebonius and Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, Caesar's lieutenants. It became a city of Roman law in 49 BC.[12] It acquired the status of Roman colony in 43 BC. Pomponius Mela placed it among the most flourishing cities of the province.[13]

Over the years 121 and 122 the Emperor Hadrian stayed in the Province where he visited Vaison, Orange, Apt, and Avignon. He gave Avignon the status of a Roman colony: "Colonia Julia Hadriana Avenniensis" and its citizens were enrolled in the tribu.[14]

Following the passage of Maximian, who was fighting the Bagaudes, the Gallic peasants revolted. The first wooden bridge was built over the Rhone linking Avignon to the right bank. It has been dated by dendrochronology to the year 290. In the 3rd century there was a small Christian community outside the walls around what was to become the Abbey of Saint-Ruf.

Early Middle Ages

Although the date of the Christianization of the city is not known with certainty, it is known that the first evangelizers and prelates were within the hagiographic tradition which is attested by the participation of Nectarius, the first historical Bishop of Avignon[e] on 29 November 439, in the regional council in the Cathedral of Riez assisted by the 13 bishops of the three provinces of Arles.

The memory of St. Eucherius still clings to three vast caves near the village of Beaumont whither, it is said, the people of Lyon had to go in search of him in 434 when they sought him to make him their archbishop.

In November 441 Nectarius of Avignon, accompanied by his deacon Fontidius, participated in the Council of Orange convened and chaired by Hilary of Arles where the Council Fathers defined the right of asylum. In the following year, together with his assistants Fonteius and Saturninus, he was at the first Council of Vaison with 17 bishops representing the Seven Provinces. He died in 455.[f]

Invasions began and during the inroads of the Goths it was badly damaged. In 472 Avignon was sacked by the Burgundians and replenished by the Patiens, from the city of Lyon, who sent them Wheat.[g]

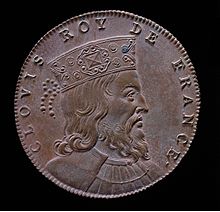

In 500 Clovis I, King of the Franks, attacked Gundobad, King of the Burgundians who was accused of the murder of the father of his wife Clotilde. Beaten, Gondebaud left Lyon and took refuge in Avignon with Clovis besieging it. Gregory of Tours reported that the Frankish king devastated the fields, cut down the vines and olive trees, and destroyed the orchards. The Burgundian was saved by the intervention of the Roman General Aredius. He had called him to his aid against the "Frankish barbarians" who ruined the countryside.

In 536 Avignon, following the fate of Provence, was ceded to the Merovingians by Vitiges, the new king of the Ostrogoths. Chlothar I annexed Avignon, Orange, Carpentras, and Gap; Childebert I took Arles and Marseilles; Theudebert I took Aix, Apt, Digne, and Glandevès. The Emperor Justinian I at Constantinople approved the division.

Despite all the invasions, intellectual life continued to flourish on the banks of the Rhône.[h] Gregory of Tours noted that after the death of Bishop Antoninus in 561 the Parisian Father Dommole refused the bishopric of Avignon after Chlothar I convinced him that it would be ridiculous "in the middle of tired senators, sophists, and philosophical judges"

St. Magnus was a Gallo-Roman senator who became a monk and then bishop of the city. His son, St. Agricol (Agricolus), bishop between 650 and 700, is the patron saint of Avignon.

The 7th and 8th centuries were the darkest period in the history of Avignon. The city became the prey of the Franks under Thierry II (Theodoric), King of Austrasia in 612. The Council of Chalon-sur-Saône in 650 was the last to indicate the Episcopal participation of the Provence dioceses. In Avignon there would be no bishop for 205 years with the last known holder being Agricola.[i]

In 736 it fell into the hands of the Saracens and was destroyed in 737 by the Franks under Charles Martel for having sided with the Saracens against him.

A centralized government was put in place and, in 879, the bishop of Avignon, Ratfred, with other Provençal colleagues[15][j] went to the Synod of Mantaille in Viennois where Boso was elected King of Provence after the death of Louis the Stammerer.[k]

The Rhône could again be crossed since in 890 part of the ancient bridge of Avignon was restored at the pier No. 14 near Villeneuve. In that same year Louis, the son of Boson, succeeded his father. His election took place in the Synod of Varennes near Macon. Thibert, who was his most effective supporter became Count of Apt. In 896 Thibert acted as plenipotentiary of the king at Avignon, Arles, and Marseille with the title of "Governor-General of all the counties of Arles and Provence". Two years later, at his request, King Louis donated Bédarrides to the priest Rigmond d'Avignon.

On 19 October 907 King Louis the Blind became emperor[l] and restored an island in the Rhone to Remigius, Bishop of Avignon. This Charter is the first mention of a cathedral dedicated to Mary.[m]

After the capture and the execution of his cousin, Louis III, who had been exiled to Italy in 905, Hugh of Arles became regent and personal advisor to King Louis. He exercised most of the powers of the king of Provence[16] and in 911, when Louis III gave him the titles of Duke of Provence and Marquis of the Viennois,[16][17] he left Vienne and moved to Arles which was the original seat of his family and which now was the new capital of Provence.

On 2 May 916 Louis the Blind restored the churches of Saint-Ruf and Saint-Géniès to the diocese of Avignon. On the same day Bishop Fulcherius attested in favour of his canons and for the two churches of Notre-Dame and Saint-Étienne to form a cathedral.[n]

A political event of importance took place in 932 with the reunion of the kingdom of Provence with Upper Burgundy. This union formed the Kingdom of Arles in which Avignon was one of the largest cities.

At the end of the 9th century, Muslim Spain installed a military base in Fraxinet[o] since they had led the plundering expeditions in the Alps throughout the 10th century.

During the night of 21 to 22 July 972 the Muslims took dom Mayeul,[p] the Abbot of Cluny who was returning from Rome, prisoner. They asked for one livre for each of them which came to 1,000 livres, a huge sum, which was paid to them quickly. Maïeul was released in mid-August and returned to Cluny in September.

In September 973 William I of Provence and his brother Rotbold, sons of the Count of Avignon, Boso II, mobilized all the nobles of Provence on behalf of dom Maïeul. With the help of Ardouin, Marquis of Turin, and after two weeks of siege, Provençal troops chased the Saracens from their hideouts in Fraxinet and Ramatuelle as well as those at Peirimpi near Noyers in the Jabron valley. William and Roubaud earned their title of Counts of Provence. William had his seat at Avignon and Roubaud at Arles.

In 976 while Bermond, brother-in-law of Eyric[q] was appointed Viscount of Avignon by King Conrad the Peaceful on 1 April, the Cartulary of Notre-Dame des Doms in Avignon says that Bishop Landry restored rights that had been unjustly appropriated to the canons of Saint-Étienne. He gave them a mill and two houses he built for them on the site of the current Trouillas Tower at the papal palace. In 980 these canons were constituted in a canonical chapter by Bishop Garnier.

In 994 Dom Maïeul arrived in Avignon where his friend William the Liberator was dying. He assisted in his last moments on the island facing the city (the Île de la Barthelasse) on the Rhone. The Count had as successor the son he had by his second wife Alix. He would reign jointly with his uncle Rotbold under the name William II. In the face of County and episcopal power, the town of Avignon organized itself. Towards the year 1000 there was already a proconsul Béranger with his wife Gilberte who are known to have founded an abbey at "Castrum Caneto".[r]

In 1032 when Conrad II inherited the Kingdom of Arles, Avignon was attached to the Holy Roman Empire. The Rhone was now a border that could only be crossed on the old bridge at Avignon. Some Avignon people still use the term "Empire Land" to describe the Avignon side, and "Kingdom Land" to designate the Villeneuve side to the west which was in the possession of the King of France.

Late Middle Ages

After the division of the empire of Charlemagne, Avignon came within the Kingdom of Arles or Kingdom of the Two Burgundies, and was owned jointly by the Count of Provence and the Count of Toulouse. From 1060, the Count of Forcalquier also had nominal overlordship, until these rights were resigned to the local Bishops and Consuls in 1135.

With the German rulers at a distance, Avignon set up an autonomous administration with the creation of a consulat in 1129, two years before its neighbour Arles.

In 1209 the Council of Avignon ordered a second excommunication for Raymond VI of Toulouse.[18]

At the end of the twelfth century, Avignon declared itself an independent republic, and sided with Raymond VII of Toulouse during the Albigensian Crusade. In 1225, the citizens refused to open the gates of Avignon to King Louis VIII of France and the papal legate. They besieged the city for three months (10 June-9 September).[18] Avignon was captured and forced to pull down its ramparts and fill up its moat.

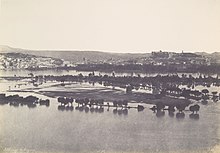

At the end of September, a few days after the surrender of the city to the troops of King Louis VIII, Avignon experienced flooding.

In 1249 the city again declared itself a republic on the death of Raymond VII, his heirs being on a crusade.

On 7 May 1251, however, the city was forced to submit to two younger brothers of King Louis IX, Alphonse of Poitiers and Charles of Anjou (Charles I of Naples). They were heirs through the female line of the Marquis and Count of Provence, and thus co-lords of the city. After the death of Alphonse in 1271, Philip III of France inherited his share of Avignon and passed it to his son Philip the Fair in 1285. It passed in turn in 1290 to Charles II of Naples, who thereafter remained the sole lord of the entire city.

The University of Avignon was founded by Pope Boniface VIII in 1303 and was famed as a seat of legal studies, flourishing until the French Revolution (1792).

Avignon papacy

In 1309 the city, still part of the Kingdom of Arles, was chosen by Pope Clement V as his residence at the time of the Council of Vienne and, from 9 March 1309 until 13 January 1377, Avignon rather than Rome was the seat of the Papacy. At the time the city and its surroundings (the Comtat Venaissin) were ruled by the kings of Sicily of the House of Anjou. The French King Philip the Fair, who had inherited from his father all the rights of Alphonse de Poitiers (the last Count of Toulouse), made them over to Charles II, King of Naples and Count of Provence (1290). Nonetheless, Philip was a shrewd ruler. Inasmuch as the eastern banks of the Rhone marked the edge of his kingdom, when the river flooded up into the city of Avignon, Philip taxed the city since during periods of flood, the city technically lay within his domain.

Avignon became the Pontifical residence under Pope Clement V in 1309.[19] His successor, John XXII, a former bishop of the diocese, made it the capital of Christianity and transformed his former episcopal palace into the primary Palace of the Popes.[20] It was Benedict XII who built the Old Palace[21] and his successor Clement VI the New Palace.[22] He bought the town on 9 June 1348 from Joanna I of Naples, the Queen of Naples and Countess of Provence for 80,000 florins. Innocent VI endowed the ramparts.[23]

Under their rule, the Court seethed and attracted many merchants, painters, sculptors and musicians. Their palace, the most remarkable building in the International Gothic style was the result, in its construction and ornamentation, of the joint work of the best French architects, Pierre Peysson and Jean du Louvres (called Loubières)[24] and the larger frescoes from the School of Siena: Simone Martini and Matteo Giovanetti.[25]

The papal library in Avignon was the largest in Europe in the 14th century with 2,000 volumes[26] Around the library were a group of passionate clerics of letters who were pupils of Petrarch, the founder of Humanism.[27] At the same time the Clementine Chapel, called the Grande Chapelle, attracted composers, singers, and musicians[28] including Philippe de Vitry, inventor of the Ars Nova, and Johannes Ciconia.[27]

As Bishop of Cavaillon, Cardinal Philippe de Cabassoles, Lord of Vaucluse, was the great protector of the Renaissance poet Petrarch.

Urban V took the first decision to return to Rome, to the delight of Petrarch, but the chaotic situation there with different conflicts prevented him from staying there. He died shortly after his return to Avignon.[29]

His successor, Gregory XI, also decided to return to Rome and this ended the first period of the Avignon Papacy. When Gregory XI brought the seat of the papacy to Rome in 1377, the city of Avignon was administered by a legate.[29]

The early death of Gregory XI, however, caused the Great Schism. Clement VII and Benedict XIII reigned again in Avignon[30] Overall therefore it was nine popes who succeeded in the papal palace and enriched themselves during their pontificate.[24]

From then on until the French Revolution, Avignon and the Comtat were papal possessions:[31] first under the schismatic popes of the Great Schism, then under the popes of Rome ruling via legates until 1542, and then by vice-legates. The Black Death appeared at Avignon in 1348 killing almost two-thirds of the city's population.[32][33]

In all seven popes and two anti-popes resided in Avignon:

- Clement V: 1305–1314 (curia moved to Avignon March 9, 1309)

- John XXII: 1316–1334

- Benedict XII: 1334–1342

- Clement VI: 1342–1352

- Innocent VI: 1352–1362

- Urban V: 1362–1370 (in Rome 1367-1370; returned to Avignon 1370)

- Gregory XI: 1370–1378 (left Avignon to return to Rome on September 13, 1376)

- Anti-Popes

- Clement VII (1378-1394)

- Benedict XIII (1394-1403)

The walls that were built by the popes in the years immediately following the acquisition of Avignon as papal territory are well preserved. As they were not particularly strong fortifications, the Popes relied instead on the immensely strong fortifications of their palace, the "Palais des Papes". This immense Gothic building, with walls 17–18 feet thick, was built 1335–1364 on a natural spur of rock, rendering it all but impregnable to attack. After its capture following the French Revolution, it was used as a barracks and prison for many years but it is now a museum.

Avignon, which at the beginning of the 14th century was a town of no great importance, underwent extensive development during the time the seven Avignon popes and two anti-popes, Clement V to Benedict XIII, resided there. To the north and south of the rock of the Doms, partly on the site of the Bishop's Palace that had been enlarged by John XXII, was built the Palace of the Popes in the form of an imposing fortress consisting of towers linked to each other and named as follows: La Campane, Trouillas, La Glacière, Saint-Jean, Saints-Anges (Benedict XII), La Gâche, La Garde-Robe (Clement VI), Saint-Laurent (Innocent VI). The Palace of the Popes belongs, by virtue of its severe architecture, to the Gothic art of the South of France. Other noble examples can be seen in the churches of Saint-Didier, Saint-Pierre, and Saint Agricol as well as in the Clock Tower and in the fortifications built between 1349 and 1368 for a distance of some three miles (5 km) flanked by thirty-nine towers, all of which were erected or restored by the Roman Catholic Church.

The popes were followed to Avignon by agents (or factors) of the great Italian banking-houses who settled in the city as money-changers and as intermediaries between the Apostolic Camera and its debtors. They lived in the most prosperous quarter of the city which was known as the Exchange. A crowd of traders of all kinds brought to market the produce necessary for maintaining the numerous courts and for the visitors who flocked to it: grain and wine from Provence, the south of France, Roussillon, and the country around Lyon. Fish was brought from places as distant as Brittany; rich cloth and tapestries came from Bruges and Tournai. The account-books of the Apostolic Camera, which are still kept in the Vatican archives, give an idea of the trade of which Avignon became the centre. The university founded by Boniface VIII in 1303 had many students under the French popes. They were drawn there by the generosity of the sovereign pontiffs who rewarded them with books or benefices.

Early modern period

After the restoration of the Papacy in Rome the spiritual and temporal government of Avignon was entrusted to a gubernatorial Legate, notably the Cardinal-nephew, who was replaced in his absence by a vice-legate (contrary to the legate he was usually a commoner and not a cardinal). Pope Innocent XII abolished nepotism and the office of Legate in Avignon on 7 February 1693, handing over its temporal government in 1692 to the Congregation of Avignon (i.e. a department of the papal Curia which resided in Rome), with the Cardinal Secretary of State as presiding prefect, who exercised their jurisdiction through the vice-legate. This congregation, to which appeals were made from the decisions of the vice-legate, was linked to the Congregation of Loreto within the Roman Curia. In 1774 the vice-legate was made president thus depriving him of almost all authority. The office was done away with under Pius VI on 12 June 1790.

The Public Council, composed of forty-eight councillors chosen by the people, four members of the clergy, and four doctors from the university, met under the presidency of the chief magistrate of the city: the viquier (Occitan) or representative of the papal Legate or Vice-legate who annually nominated a man for the post. The councillors' duty was to watch over the material and financial interests of the city but their resolutions had to be submitted to the vice-legate for approval before being put in force. Three consuls, chosen annually by the Council, had charge of the administration of the streets.

Avignon's survival as a papal enclave was, however, somewhat precarious, as the French crown maintained a large standing garrison at Villeneuve-lès-Avignon just across the river.

On the death of the Archbishop of Arles, Philippe de Lévis in 1475, Pope Sixtus IV in Rome reduced the size of the diocese of Arles: he detached the diocese of Avignon in the province of Arles and raised it to the rank of an archbishopric in favour of his nephew Giuliano della Rovere, who later became Pope Julius II. The Archdiocese of Avignon had canonic jurisdiction over the department of Vaucluse and was an archdiocese under the bishoprics of Comtadins Carpentras, Cavaillon, and Vaison-la-Romaine.[34]

From the fifteenth century onward it became the policy of the Kings of France to rule Avignon as part of their kingdom. In 1476 Louis XI, upset that Charles of Bourbon was made legate, sent troops to occupy the city until his demands that Giuliano della Rovere be made legate. Once Giuliano della Rovere was made a cardinal he withdrew his troops from the city.

In the 15th century Avignon suffered a major flood of the Rhone. King Louis XI repaired a bridge in October 1479 by letters patent.[35]

In 1536 king Francis I of France invaded the papal territory, in order to overthrow Emperor Charles V, who was emperor of the territory. When he entered the city the people received him very well, and in return for the reception the people were all granted to them the same privileges that French subjects enjoyed, such as being able to hold state offices.

In 1562 the city was besieged by the François de Beaumont, baron des Adrets, who wanted to avenge the massacre of Orange.[36]

Charles IX passed through the city during his royal tour of France (1564-1566) together with his court and nobles of the kingdom: his brother the Duke of Anjou, Henry of Navarre, the cardinals of Bourbon and Lorraine[37] The court stayed for three weeks.

In 1583 King Henry III attempted to offer an exchange of the Marquisate of Saluzzo for Avignon, however his offer was refused by Pope Gregory XIII.

In 1618 Cardinal Richelieu was exiled in Avignon.[38]

The city was visited by Vincent de Paul in 1607 and also by Francis de Sales in 1622.[34]

In 1663 in retaliation for the attack led by the Corsican Guard on the attendants of the Duc de Créqui, the ambassador of Louis XIV in Rome, the King of France attacked and seized Avignon, which at the time was considered an important and integral part of the French Kingdom by the provincial Parliament of Provence.

In 1688 yet another attempt was made to occupy Avignon, however the attempt failed, and from 1688 to 1768 Avignon was at peace with no occupations or wars during that time.

At the beginning of the 18th century the streets of Avignon were narrow and winding but buildings changed and houses gradually replaced the old buildings. Around the city there were mulberry plantations, orchards, and grasslands.[39]

On 2 January 1733 François Morénas founded a newspaper, the Courrier d'Avignon, whose name changed over time and through prohibitions. As it was published in the papal enclave outside the kingdom of France and Monaco, the newspaper escaped the control system of the press in France (privilege with permission) while undergoing control from papal authorities. The Courrier d'Avignon appeared from 1733 to 1793 with two interruptions: one between July 1768 and August 1769 due to the annexation of Avignon to France and the other between 30 November 1790 and 24 May 1791.[40]

King Louis XV occupied the Comtat Venaissin from 1768 to 1774 and substituted French institutions for those in force with the approval of the people of Avignon; a French party grew up.

From the French Revolution to the end of the 19th century

Main article: Massacres of La Glacière and Guillaume Brune.

On 12 September 1791 the National Constituent Assembly voted for the annexation of Avignon and the reunion of Comtat Venaissin with the kingdom of France following a referendum submitted to the inhabitants of the Comtat.

On the night of 16 to 17 October 1791, after the lynching by a mob of the secretary-clerk of the commune who was wrongly suspected of wanting to seize church property, the event called the Massacres of La Glacière took place, when 60 people were summarily executed and thrown into the dungeon of the tower on the Palais des Papes.

On 7 July 1793 federalist insurgents under General Rousselet entered Avignon.[41] During their passage along the Durance to retake the city by troops from Marseilles one person was killed: Joseph Agricol Viala.[42] On 25 July General Carteaux appeared before the city and it was abandoned the next day by the troops of General Rousselet[43] as a result of a misinterpretation of orders from Marseille.[44]

On 25 June 1793 Avignon and Comtat-Venaissin were integrated along with the former principality of Orange to form the present departement of Vaucluse with Avignon as its capital. This was confirmed on 19 February 1797 by the Treaty of Tolentino in which Article 5 definitively sanctioned the annexation stating that:

"The Pope renounces, purely and simply, all the rights to which he might lay claim over the city and territory of Avignon, and the Comtat Venaissin and its dependencies, and transfers and makes over the said rights to the French Republic."

On 1 October 1795 Alexandre Mottard de Lestang, a Knight, captured the town for the royalists with a troop of 10,000 men.[45] The mission representative Boursault retook the city and had Lestang shot.

Before the French Revolution Avignon had as suffragan sees Carpentras, Vaison and Cavaillon, which were united by the Napoleonic Concordat of 1801 to Avignon, together with the Diocese of Apt, a suffragan of Aix-en-Provence. However, at that same time Avignon was reduced to the rank of a bishopric and was made a suffragan see of Aix.

On 30 May 1814 the French annexation of Avignon was recognized by the Pope. Ercole Consalvi made an ineffectual protest at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 but Avignon was never restored to the Holy See. In 1815, Bonapartist Marshal Guillaume Marie Anne Brune was assassinated by adherents of the royalist party during the White Terror. Murder took place in the former Hotel du Palais Royal that was located Place Crillon in front of today's Hotel d'Europe.

In the years 1820-1830 Villeneuve was forced to yield part of its territory to Avignon: the part called the Île de la Barthelasse.

The Archdiocese of Avignon was re-established in 1822, receiving as suffragan sees the Diocese of Viviers, Valence: (formerly under Lyon), Nîmes, and Montpellier (formerly under Toulouse).

On 18 October 1847 the Avignon - Marseille railway line was opened by the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Marseille à Avignon (Marseille to Avignon Railway Company). In 1860 the current Avignon Centre railway station was built. In November 1898 the tramway network of the Compagnie des Tramways Électriques d'Avignon (Electric Tramways Company of Avignon) was opened to replace the old company of horse-drawn transport.

During the coup of 2 December 1851 the people of Avignon, with Alphonse Gent, tried to oppose it.[46]

In 1856 a major flood on the Durance river flooded Avignon.[47]

From the beginning of the 20th century to today

The newly elected President of the Republic at the beginning of the year 1913, Raymond Poincaré, visited Provence in mid-October. He wrote in his book In the Service of France: Europe under arms: 1913, a description of his successive visits. The primary purpose of the visit was to verify in situ the state of mind of the Félibrige in the likely event of a conflict with Germany. He met, at Maillane and at Sérignan-du-Comtat, the two most illustrious people Frédéric Mistral and Jean-Henri Fabre. Between these two appointments he paused at Avignon where he was received triumphantly at the Town Hall. Already the reception he had received at the Mas du Juge from the poet and the communal meal they had taken in the presidential train at Graveson had reassured him of the patriotism of Provence. It was, therefore in these terms that he spoke on the Nobel Prize in Literature:

"Dear and illustrious master, you who have pointed out imperishable monuments in honour of French land; you who have raised the prestige of a language and a literature that has a place in our national history to be proud of; you who, in glorifying Provence, have braided a crown of olive green; to you, august master, I bring the testimony of the recognition of the Republic and the great motherland".[48][49]

The 20th century saw significant development of urbanization, mainly outside the city walls, and several major projects have emerged. Between 1920 and 1975 the population has almost doubled despite the cession of Le Pontet in 1925 and the Second World War.

On the transport side 1937 saw the creation of the Avignon - Caumont Airport which became an airport in the early 1980s and became prominent with the opening of international routes, a new control tower, extension of the runway, etc.[50]

In September 1947 the first edition of the future Avignon Festival was held.

After the Second World War on 11 November 1948 Avignon received a citation of the order of the division. This distinction involved the awarding of the Croix de Guerre with Silver Star.[51] The city rose, expanded its festival, dusted off its monuments, and developed its tourism and trade.

In 1977 the city was awarded the Europe Prize, awarded by the Council of Europe.[52]

In 1996 the LGV Méditerranée railway project was started. Its path passes through the commune and over the Rhone. From 1998 to 2001 the Avignon TGV station was built.[53]

In 2002, as part of the reshuffling of the ecclesiastic provinces of France, the Archdiocese of Avignon ceased to be a metropolitan and became, instead a suffragan diocese of the new province of Marseilles, while keeping its rank of archdiocese.

Geography

Avignon is situated on the left bank of the Rhône river, a few kilometres above its confluence with the Durance, about 580 km (360 mi) south-east of Paris, 229 km (142 mi) south of Lyon and 85 km (53 mi) north-north-west of Marseille. On the west it shares a border with the department of Gard and the communes of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon and Les Angles and to the south it borders the department of Bouches-du-Rhône and the communes of Barbentane, Rognonas, Châteaurenard, and Noves.

The city is located in the vicinity of Orange (north), Nîmes, Montpellier (south-west), Arles (to the south), Salon-de-Provence, and Marseille (south-east). Directly contiguous to the east and north are the communes of Caumont-sur-Durance, Morières-lès-Avignon, Le Pontet, and Sorgues.

Communication and transport

Roads

Avignon is close to two highways:

- the A7 autoroute (E714) is a north-south axis on which there are two exits:

23 Avignon-Nord (Northern districts of Avignon, Le Pontet, Carpentras) and

23 Avignon-Nord (Northern districts of Avignon, Le Pontet, Carpentras) and  24 Avignon-Sud (Southern districts of Avignon, Avignon-Caumont Airport);

24 Avignon-Sud (Southern districts of Avignon, Avignon-Caumont Airport); - the A9 autoroute (E15) which branches from the A7 near Orange along a north-east south-west axis towards Spain.

The main roads are:

- Route nationale N100 which goes west to Remoulins

- The D225 which goes north towards Entraigues-sur-la-Sorgue

- The D62 which goes north-east to Vedène

- The D28 which goes east to Saint-Saturnin-lès-Avignon

- The D901 which goes south-east to Morières-lès-Avignon

- Route nationale N570 which goes south to Rognonas

The city has nine paid parking buildings with a total of 7,100 parking spaces, parking buildings under surveillance with a capacity for 2,050 cars with a free shuttle to the city centre, as well as five other free parking areas with a capacity of 900 cars.[54]

Railways

Avignon is served by two railway stations: the historic train station built in 1860, the Gare d'Avignon-Centre, located just outside the city walls, which can accommodate any type of train and, since 2001, the Gare d'Avignon TGV in the "Courtine" district south of the city, on the LGV Méditerranée line. Since December 2013 the two stations have been connected by a link line - the Virgule. The Montfavet district, which was formerly a separate commune, also has a station.[55]

Airports

The Avignon - Caumont Airport on the south-eastern commune border has several international routes to England. Approximately 72,500 passengers passed through the airport in 2011.[56] The major airport in the region with domestic and international scheduled passenger service is the Marseille Provence Airport.

Water transport

The Rhône has for many centuries been an important means of transportation for the city. River traffic in Avignon has two commercial ports, docking stations for boat cruises, and various riverfront developments. A free shuttle boat has been established between the quay near the ramparts and the opposite bank (the île de la Barthelasse).

Communal transport

The Transports en Commun de la Région d'Avignon, also known by the acronym TCRA, is the public transport network for the commune of Avignon.[57]

Two tram lines are projected to open in 2016 with works expected to begin in late 2013.[58]

Bicycles

Avignon has 110 km (68 mi) of bicycle paths.[59] In 2009 the TCRA introduced a bicycle sharing system called the Vélopop'.[60]

Geology and terrain

The region around Avignon is very rich in limestone which is used for building material. For example, the current ramparts, measuring 4,330 metres long, were built with the soft limestone abundant in the region called mollasse burdigalienne.[61]

Enclosed by the ramparts, the Rocher des Doms is a limestone elevation of urgonian type, 35 metres high[62] (and therefore safe from flooding of the Rhone which it overlooks) and is the original core of the city. Several limestone massifs are present around the commune (the Massif des Angles, Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, Alpilles...) and they are partly the result of the oceanisation of the Ligurian-Provençal basin following the migration of the Sardo-Corsican block.[61]

The other significant elevation in the commune is the Montfavet Hill - a wooded hill in the east of the commune.[61]

The Rhone Valley is an old alluvial zone: loose deposits cover much of the ground. It consists of sandy alluvium more or less coloured with pebbles consisting mainly of siliceous rocks. The islands in the Rhone, such as the Île de la Barthelasse, were created by the accumulation of alluvial deposits and also by the work of man. The relief is quite low despite the creation of mounds allowing local protection from flooding.[61]

In the land around the city there are clay, silt, sand, and limestone present.[61]

Hydrography

The Rhone passes the western edge of the city but is divided into two branches: the Petit Rhône, or "dead arm", for the part that passes next to Avignon and the Grand Rhône, or "live arm", for the western channel which passes Villeneuve-lès-Avignon in the Gard department. The two branches are separated by an island, the Île de la Barthelasse. The southernmost tip of the Île de la Barthelasse once formed of a separated island, the L'Île de Piot.[63]

General

The banks of the Rhone and the Île de la Barthelasse are often subject to flooding during autumn and March. The publication Floods in France since the 6th century until today - research and documentation[47] by Maurice Champion tells about a number of them (until 1862, the flood of 1856 was one of the largest, which destroyed part of the walls). They have never really stopped as shown by the floods in 1943-1944[64] and again on 23 January 1955[65] and remain important today - such as the floods of 2 December 2003.[66] As a result, a new risk mapping has been developed.

The Durance flows along the southern boundary of the commune into the Rhone and marks the departmental boundary with Bouches-du-Rhône.[67] It is a river that is considered "capricious" and once feared for its floods (it was once called the "3rd scourge of Provence"[s] as well as for its low water: the Durance has both Alpine and Mediterranean morphology which is unusual.

There are many natural and artificial water lakes in the commune such as the Lake of Saint-Chamand east of the city.

Artificial diversions

There have been many diversions[68] throughout the course of history, such as feeding the moat surrounding Avignon or irrigating crops.

In the 10th century part of the waters from the Sorgue d'Entraigues were diverted and today pass under the ramparts to enter the city. (See Sorgue). This watercourse is called the Vaucluse Canal but Avignon people still call it the Sorgue or Sorguette. It is visible in the city in the famous Rue des teinturiers (street of dyers). It fed the moat around the first ramparts then fed the moat on the newer eastern city walls (14th century). In the 13th century (under an Act signed in 1229) part of the waters of the Durance were diverted to increase the water available for the moats starting from Bonpas. This river was later called the Durançole. The Durançole fed the western moats of the city and was also used to irrigate crops at Montfavet. In the city these streams are often hidden beneath the streets and houses and are currently used to collect sewerage.

The Hospital Canal (joining the Durançole) and the Crillon Canal (1775) were dug to irrigate the territories of Montfavet, Pontet, and Vedène. They were divided into numerous "fioles" or "filioles" (in Provençal filhòlas or fiolo). Similarly, to irrigate the gardens of the wealthy south of Avignon, the Puy Canal was dug (1808). All of these canals took their water from the Durance. These canals were initially used to flood the land, which was very stony, to fertilize them by deposition of silt.

All of these canals have been used to operate many mills.

Seismicity

Under the new seismic zoning of France defined in Decree No. 2010-1255 of 22 October 2010 concerning the delimitation of the seismicity of the French territory and which entered into force on 1 May 2011, Avignon is located in an area of moderate seismicity. The previous zoning is shown below for reference.

"The cantons of Bonnieux, Apt, Cadenet, Cavaillon, and Pertuis are classified in zone Ib (low risk). All other cantons the Vaucluse department, including Avignon, are classified Ia (very low risk). This zoning is for exceptional seismicity resulting in the destruction of buildings.".[69]

The presence of faults in the limestone substrate shows that significant tectonic shift has caused earthquakes in different geological ages. The last major earthquake of significant magnitude was on 11 June 1909.[t] It left a visible trace in the centre of the city since the bell tower of the Augustinians, which is surmounted by an ancient campanile of wrought iron, located in Rue Carreterie, remained slightly leaning as a result of this earthquake.

Climate

Avignon has a mediterranean climate (Csa in the Köppen climate classification), with mild winters and hot summers, with moderate rainfall year-round. July and August are the hottest months with average daily maximum temperatures of around 28 °C, and January and February the coldest with average daily maximum temperatures of around 9 °C. The wettest month is September, with a rain average of 102 millimetres, and the driest month is July, when the monthly average rainfall is 37 millimetres. The city is often subject to windy weather; the strongest wind is the mistral. A medieval Latin proverb said of the city: Avenie ventosa, sine vento venenosa, cum vento fastidiosa (Windy Avignon, pest-ridden when there is no wind, wind-pestered when there is).[70]

| Town | Sunshine (hours/yr) |

Rain (mm/yr) |

Snow (days/yr) |

Storm (days/yr) |

Fog (days/yr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National average | 1,973 | 770 | 14 | 22 | 40 |

| Avignon[72] | 2,596 | 709 | 4 | 23 | 31 |

| Paris | 1,661 | 637 | 12 | 18 | 10 |

| Nice | 2,724 | 767 | 1 | 29 | 1 |

| Strasbourg | 1,693 | 665 | 29 | 29 | 56 |

| Brest | 1,605 | 1,211 | 7 | 12 | 75 |

| Climate data for Orange | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

23.9 (75.0) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.6 (34.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.8 (53.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.0 (2.01) |

39.4 (1.55) |

43.9 (1.73) |

66.0 (2.60) |

65.3 (2.57) |

38.3 (1.51) |

36.9 (1.45) |

42.3 (1.67) |

102.0 (4.02) |

92.9 (3.66) |

75.4 (2.97) |

55.7 (2.19) |

709.1 (27.92) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 3.0 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 65.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 132 | 137 | 193 | 230 | 265 | 299 | 345 | 311 | 238 | 187 | 135 | 124 | 2,596 |

| Source: Meteorological data for Orange - 53m altitude, from 1981 to 2010 January 2015 Template:Fr icon | |||||||||||||

According to Météo-France the number of days per year with rain above 2.5 litres per square metre is 45 and the amount of water, rain and snow combined is 660 litres per square metre. Average temperatures vary between 0 and 30 °C depending on the season. The record temperature record since the existence of the weather station at Orange is 40.7 °C on 26 July 1983 and the record lowest was -14.5 °C on 2 February 1956.[73]

The mistral

The prevailing wind is the mistral for which the windspeed can be beyond 110 km/h. It blows between 120 and 160 days per year with an average speed of 90 km/h in gusts.[74] The following table shows the different speeds of the mistral recorded by Orange and Carpentras Serres stations in the southern Rhone valley and its frequency in 2006. Normal corresponds to the average of the last 53 years from Orange weather reports and that of the last 42 at Carpentras.[75]

Legend: "=" same as normal; "+" Higher than normal; "-" Lower than normal.

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May. | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum recorded speed by month | 106 km/h | 127 km/h | 119 km/h | 97 km/h | 94 km/h | 144 km/h | 90 km/h | 90 km/h | 90 km/h | 87 km/h | 91 km/h | 118 km/h |

| Tendency: Days with speed > 16 m/s (58 km/h) |

-- | +++ | --- | ++++ | ++++ | = | = | ++++ | + | --- | = | ++ |

Demography

In 2010 the commune had 89,683 inhabitants. The evolution of the number of inhabitants is known from the population censuses conducted in the commune since 1793. From the 21st century, a census of communes with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants is held every five years, unlike larger communes that have a sample survey every year. Template:Table Population Town

Administration

Avignon is the prefecture (capital) of Vaucluse department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur region. It forms the core of the Grand Avignon metropolitan area (communauté d'agglomération), which comprises 15 communes on both sides of the river:[76]

- Les Angles, Pujaut, Rochefort-du-Gard, Sauveterre, Saze and Villeneuve-lès-Avignon in the Gard département;

- Avignon, Caumont-sur-Durance, Entraigues-sur-la-Sorgue, Jonquerettes, Morières-lès-Avignon, Le Pontet, Saint-Saturnin-lès-Avignon, Vedène and Velleron in the Vaucluse département.

List of Mayors

| From | To | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1790 | Jean-Baptiste d'Armand |

| 1790 | 1791 | Antoine Agricol Richard |

| 1791 | 1792 | Levieux-Laverne |

| 1792 | 1793 | Jean-Ettienne Duprat |

| 1793 | 1793 | Jean-André Cartoux |

| 1793 | 1793 | Jean-François ROCHETIN |

| 1795 | 1795 | Guillaume François Ignace Puy |

| 1795 | 1796 | Alexis Bruny |

| 1796 | 1796 | Père Minvielle |

| 1796 | 1797 | Faulcon |

| 1797 | 1798 | Père Minvielle |

| 1798 | 1799 | Cadet Garrigan |

| 1799 | 1800 | Père Niel |

| 1800 | 1806 | Guillaume François Ignace PUY |

| 1806 | 1811 | Agricol Joseph Xavier Bertrand |

| 1811 | 1815 | Guillaume François Ignace Puy |

| 1815 | 1815 | Hippolyte Roque de Saint-Pregnan |

| 1815 | 1819 | Charles de Camis-Lezan |

| 1819 | 1820 | Louis Duplessis de Pouzilhac |

| 1820 | 1826 | Charles Soullier |

| 1826 | 1830 | Louis Pertuis de Montfaucon |

| 1830 | 1832 | François Jillian |

| 1832 | 1833 | Balthazar Delorme |

| 1834 | 1837 | Hippolyte Roque de Saint-Pregnan |

| 1837 | 1841 | Dominique Geoffroy |

| 1841 | 1843 | Albert d'Olivier de Pezet |

| 1843 | 1847 | Eugène Poncet |

| 1847 | 1848 | Hyacinthe Chauffard |

| 1848 | 1848 | Alphonse Gent |

| 1848 | 1848 | Frédéric Granier |

| 1848 | 1850 | Gabriel Vinay |

| 1850 | 1852 | Martial BOSSE |

| 1852 | 1853 | Eugène Poncet |

| 1853 | 1865 | Paul Pamard |

| 1865 | 1870 | Paul Poncet |

| 1870 | 1871 | Paul Bourges |

| 1871 | 1874 | Paul Poncet |

| 1874 | 1878 | Roger du Demaine |

| 1878 | 1881 | Paul Poncet |

| 1881 | 1881 | Eugène Millo |

| 1881 | 1884 | Charles Deville |

| 1884 | 1888 | Paul Poncet |

| 1888 | 1903 | Gaston Pourquery de Boisserin |

| 1903 | 1904 | Alexandre Dibon |

| 1904 | 1910 | Henri Guigou |

| 1910 | 1919 | Louis Valayer |

| 1919 | 1925 | Ferdinand Bec |

| 1925 | 1928 | Louis Gros |

| 1929 | 1940 | Louis Nouveau |

- Mayors from 1940

| From | To | Name | Party | Position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 1942 | Jean Gauger | ||

| 1942 | 1944 | Edmond Pailheret | ||

| 1944 | 1945 | Louis Gros | ||

| 1945 | 1947 | Georges Pons | ||

| 1947 | 1948 | Paul Rouvier | ||

| 1948 | 1950 | Henri Mazo | ||

| 1950 | 1953 | Noël Hermitte | ||

| 1953 | 1958 | Edouard Daladier | ||

| 1958 | 1983 | Henri Duffaut | PS | |

| 1983 | 1989 | Jean-Pierre Roux | RPR | |

| 1989 | 1995 | Guy Ravier | PS | |

| 1995 | 2014 | Marie-José ROIG | UMP | |

| 2014 | 2020 | Cécile HELLE | PS |

(Not all data is known)

Twinning

Avignon has twinning associations with:[78]

Colchester (England) since 1972.[79]

Colchester (England) since 1972.[79] Guanajuato (Mexico) since 1990.

Guanajuato (Mexico) since 1990. Ioanina (Greece) since 1984.

Ioanina (Greece) since 1984. New Haven (USA) since 1993.

New Haven (USA) since 1993. Siena (Italy) since 1981.

Siena (Italy) since 1981. Tarragona (Spain) since 1968.

Tarragona (Spain) since 1968. Wetzlar (Germany) since 1960.

Wetzlar (Germany) since 1960.

Evolution of the borders of the commune

Avignon absorbed Montfavet between 1790 and 1794 then ceded Morières-lès-Avignon in 1870 and Le Pontet in 1925.[80] On 16 May 2007 the commune of Les Angles in Gard ceded 13 hectares to Avignon.[81]

Area and population

The city of Avignon has an area of 64.78 km2 and a population of 92,078 inhabitants in 2010 and is ranked as follows:[81]

| Rank | Land Area | Population | Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| France | 524th | 46th | 632nd |

| Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 105th | 5th | 23rd |

| Vaucluse | 6th | 1st | 2nd |

Economy

Avignon is the seat of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Vaucluse which manages the Avignon - Caumont Airport and the Avignon-Le Pontet Docks.

Avignon has 7,000 businesses, 1,550 associations, 1,764 shops, and 1,305 service providers.[59] The urban area has one of the largest catchment areas in Europe with more than 300,000 square metres of retail space and 469 m2 per thousand population against 270 on average in France.[82] The commercial area of Avignon Nord is one of the largest in Europe.[83]

The tertiary sector is the most dynamic in the department by far on the basis of the significant production of early fruit and vegetables in Vaucluse, The MIN (Market of National Importance) has become the pivotal hub of commercial activity in the department, taking precedence over other local markets (including that of Carpentras). In the 1980s and 1990s the development of trade between the North and South of Europe has strengthened the position of Avignon as a logistics hub and promoted the creation of transport and storage businesses for clothing and food.

A Sensitive urban zone was created for companies wanting to relocate with exemptions from tax and social issues.[84] It is located south of Avignon between the city walls and the Durance located in the districts of Croix Rouge, Monclar, Saint-Chamand, and La Rocade.[85]

Areas of economic activity

There are nine main areas of economic activity in Avignon.[86]

The Courtine area is the largest with nearly 300 businesses (of which roughly half are service establishments, one third are shops, and the rest related to industry) and more than 3,600 jobs.[86] The site covers an area of 300 hectares and is located south-west of the city at the TGV railway station.

Then comes the Fontcouverte area with a hundred establishments representing a thousand jobs. It is, however, more oriented towards shops than the Courtine area.[86]

The MIN area of Avignon is the Agroparc area[u] (or "Technopole Agroparc"). The Cristole area is contiguous and both have a little less than a hundred establishments.[86]

Finally, the areas of Castelette, Croix de Noves, Realpanier, and the airport each have fewer than 25 establishments spread between service activities and shops. The area of the Castelette alone represents more than 600 jobs - i.e. 100 more than Cristole.[86]

Tourism

Four million visitors come annually to visit the city and the region and also for its festival.[59] In 2011 the most popular tourist attraction was the Palais des Papes with 572,972 paying visitors.[56] The annual Festival d'Avignon is the most important cultural event in the city. The official festival attracted 135,800 people in 2012.[56]

River tourism began in 1994 with three river boat-hotels. In 2011 there is a fleet of 21 river boat-hotelsbuildings, including six sight-seeing boats which are anchored on the quay along the Oulle walkways. Attendance during the 2000s was increased with nearly 50,000 tourists coming mostly from Northern Europe and North America. In addition a free shuttle boat connects Avignon to the Île de la Barthelasse and, since 1987, a harbor master has managed all river traffic.

Agriculture

The city is the headquarters of the International Association of the Mediterranean tomato, the World Council of the tomato industry, and the Inter-Rhône organisation.

Industry

Only EDF (Grand Delta) with about 850 employees and Onet Propreté[v] with just over 300 exceed 100 employees.[87]

Public sector (excluding government)

The Henri Duffaut hospital, the City of Avignon, and the CHS of Montfavet are the largest employers in the town with about 2,000 employees each. Then comes the General Council of Vaucluse with about 1,300 employees.[87]

The International Convention Centre

Since 1976 a convention centre has occupied two wings of the palace of the popes. With ten reception and conference rooms, it hosts many events. The large prestigious rooms Grand Tinel and Grande Audience, located on the visitor circuit for the monument, are used to complement the conference rooms for organizing cocktails, gala dinners, exhibitions etc.

Income and taxation

In 2010 the median household income tax was €14,143 placing Avignon at 28,960th among the 30,714 communes of more than 50 households in France.[88]

Employment

In 2011 the unemployment rate was 15.6% while it was 13.7% in 2006.[89] There are 39,100 people in the Avignon workforce: 78 (0.002%) agricultural workers, 2,191 (5.6%) tradesmen, shopkeepers, and business managers, 4,945 (12.6%) managers and intellectuals, 8,875 (22.6%) middle managers, 12,257 (31.3%) employees, and 9,603 (24.6%) workers.[89]

Cultural heritage

Avignon has a very large number of sites and buildings (173) that are registered as historical monuments.[90]

In the part of the city within the walls the buildings are old but in most areas they have been restored or reconstructed (such as the post office and the Lycée Frédéric Mistral).[91] The buildings along the main street, Rue de la République, date from the Second Empire (1852–70) with Haussmann façades and amenities around Place de l'Horloge (the central square), the neoclassical city hall, and the theatre district.

Listed below are the major sites of interest with those sites registered as historical monuments indicated:

- Notre Dame des Doms (12th century),

[92] the cathedral, is a Romanesque building, mainly built during the 12th century, the most prominent feature of the cathedral is the 19th century gilded statue of the Virgin which surmounts the western tower. The mausoleum of Pope John XXII (1334)

[92] the cathedral, is a Romanesque building, mainly built during the 12th century, the most prominent feature of the cathedral is the 19th century gilded statue of the Virgin which surmounts the western tower. The mausoleum of Pope John XXII (1334) [93] is one of the most beautiful works within the cathedral, it is a noteworthy example of 14th-century Gothic carving.

[93] is one of the most beautiful works within the cathedral, it is a noteworthy example of 14th-century Gothic carving. - The Palais des Papes ("Papal Palace") (14th century)

[94] almost dwarfs the cathedral. The palace is an impressive monument and sits within a square of the same name. The palace was begun in 1316 by John XXII and continued by succeeding popes through the 14th century, until 1370 when it was finished.

[94] almost dwarfs the cathedral. The palace is an impressive monument and sits within a square of the same name. The palace was begun in 1316 by John XXII and continued by succeeding popes through the 14th century, until 1370 when it was finished. - Minor churches of the town include, among others, three churches which were built in the Gothic architectural style:

- Civic buildings are represented most notably by:

- the Hôtel de Ville (city hall) (1846),

[98] a relatively modern building with a bell tower from the 14th century,

[98] a relatively modern building with a bell tower from the 14th century, - the old Hôtel des Monnaies

,[99] the papal mint which was built in 1610 and became a music-school.

,[99] the papal mint which was built in 1610 and became a music-school.

- the Hôtel de Ville (city hall) (1846),

- The Ramparts,

[100] built by the popes in the 14th century and still encircle Avignon. They are one of the finest examples of medieval fortification in existence. The walls are of great strength and are surmounted by machicolated battlements flanked at intervals by 39 massive towers and pierced by several gateways, three of which date from the 14th century. The walls were restored under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

[100] built by the popes in the 14th century and still encircle Avignon. They are one of the finest examples of medieval fortification in existence. The walls are of great strength and are surmounted by machicolated battlements flanked at intervals by 39 massive towers and pierced by several gateways, three of which date from the 14th century. The walls were restored under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc - Bridges include:

- a little bridge which leads over the river to Villeneuve-les-Avignon

- The Pont d'Avignon (the Pont Saint-Bénézet). Only four of the twenty one piers are left; on one of them stands the small Romanesque chapel of Saint-Bénézet.[101] But the bridge is best known for the famous French song Sur le pont d'Avignon.

- The Calvet Museum, so named after Esprit Calvet, a physician who in 1810 left his collections to the town. It has a large collection of paintings, metalwork and other objects. The library has over 140,000 volumes.[102]

- The town has a Statue of Jean Althen, who migrated from Persia and in 1765 introduced the culture of the madder plant, which long formed the staple—and is still an important tool—of the local cloth trade in the area.

- The Musée du Petit Palais (opened 1976) at the end of the square overlooked by the Palais des Papes, has an exceptional collection of Renaissance paintings of the Avignon school as well as from Italy, which reunites many "primitives" from the collection of Giampietro Campana.

- The Hotel d'Europe, one of the oldest hotels in France, in business since 1799.

- The Collection Lambert, houses contemporary art exhibitions

- The Musée Angladon exhibits the paintings of a private collector who created the museum

- The Musée Lapidaire, with collections of archaeological and medieval sculptures from the Fondation Calvet in the old chapel of the Jesuit College.

- The Musée Louis-Vouland

- The Musée Requien

- The Palais du Roure

[103]

[103] - Les Halles is a large indoor market that offers fresh produce, meats, and fish along with a variety of other goods.

- The Place Pie is a small square near Place de l'Horloge where you can partake in an afternoon coffee on the outdoor terraces or enjoy a night on the town later in the evening as the square fills with young people.

Religious historical objects

The commune houses an extremely large number of religious items which are listed as historical objects. To see a comprehensive list of objects in each location click on the numbers in the table below:

Locations of Historical Objects

| Location | No. of Objects |

|---|---|

| Cathedral of Notre-Dame des Doms | 268 objects |

| Chapel of the Oratory | 1 object |

| Chapel of the White penitents | 5 objects |

| Chapel of the Grey penitents | 3 objects |

| Chapel of the Black penitents | 9 objects |

| Chapel of the Grand Seminary | 1 object |

| College of Saint-Joseph | 3 objects |

| Hospice of Saint-Louis | 1 object |

| Hospital Sainte-Marthe | 26 objects |

| Hotel of Saint-Priest d'Urgel (Hotel de Monery) | 27 objects |

| House of King René | 1 object |

| Calvet Museum | 3 objects |

| Arch-episcopal Palace | 1 object |

| Palais des Papes | 3 objects |

| Synagogue | 4 objects |

| Church of Saint-Agricol | 43 objects |

| Church of Saint-Didier | 21 objects |

| Church of Saint-Pierre | 23 objects |

| Church of Saint-Symphorien | 12 objects |

| Church of Montfavet | 4 objects |

| Total Objects | 459 |

Picture gallery

-

View of the Palais des papes from the square on the western side.

-

The Abbey of Saint-Ruf.

-

The Pont d'Avignon famous from the song Sur le Pont d'Avignon.

-

The Pont Saint-Bénézet, illuminated at night.

-

The Ramparts of Avignon.

-

The Hôtel des Monnaies.

Culture

Avignon Festival

A famous theatre festival is held annually in Avignon. Founded in 1947, the Avignon Festival comprises traditional theatrical events as well as other art forms such as dance, music, and cinema, making good use of the town's historical monuments. Every summer approximately 100,000 people attend the festival.[104] There are really two festivals that take place: the more formal "Festival In", which presents plays inside the Palace of the Popes and the more bohemian "Festival Off", which is known for its presentation of largely undiscovered plays and street performances.

The International Congress Centre

The Centre was created in 1976 within the premises of the Palace of the Popes and hosts many events throughout the entire year. The Congress Centre, designed for conventions, seminars, and meetings for 10 to 550 persons, now occupies two wings of the Popes' Palace.[105]

Sport

Sporting Olympique Avignon is the local rugby league football team. During the 20th century it produced a number of French international representative players.

AC Arles-Avignon is a professional French football team. They compete in Ligue 2, having gained promotion from Ligue 3 in June 2009. After a season 2010-2011 competing in Ligue 1, the Arles-Avignon team came back in Ligue 2. They play at the Parc des Sports, which has a capacity of just over 17,000.

Nuclear pollution

On 8 July 2008 waste containing unenriched uranium leaked into two rivers from a nuclear plant in southern France. Some 30,000 litres (7,925 gallons) of solution containing 12g of uranium per litre spilled from an overflowing reservoir at the facility – which handles liquids contaminated by uranium – into the ground and into the Gaffiere and Lauzon rivers. The authorities kept this a secret from the public for 12 hours then issued a statement prohibiting swimming and fishing in the Gaffiere and Lauzon rivers.[106]

Sur le Pont d'Avignon

Avignon is commemorated by the French song, "Sur le Pont d'Avignon" ("On the bridge of Avignon"), which describes folk dancing. The song dates from the mid-19th century when Adolphe Adam included it in the Opéra comique Le Sourd ou l'Auberge Pleine which was first performed in Paris in 1853. The opera was an adaptation of the 1790 comedy by Desforges.[107]

The bridge of the song is the Saint-Bénézet bridge over the Rhône of which only four arches (out of the initial 22) now remain. A bridge across the Rhone was built between 1171 and 1185, with a length of some 900 m (2950 ft), but was destroyed during the siege of Avignon by Louis VIII of France in 1226. It was rebuilt but suffered frequent collapses during floods and had to be continually repaired. Several arches were already missing (and spanned by wooden sections) before the remainder was abandoned in 1669.[108]

Education

The schools within the commune of Avignon are administered by the Académie d'Aix-Marseille. There are 26 state nursery schools (Écoles maternelles) for children up to 6, and 32 state primary schools (Écoles élémentaires) up to 11. There are also 4 private schools.[109]

University of Avignon

University before the Revolution

The medieval University of Avignon, formed from the existing schools of the city, was formally constituted in 1303 by Boniface VIII in a Papal Bull. Boniface VIII and King Charles II of Naples were the first great protectors and benefactors to the university. The Law department was the most important department covering both civil and ecclesiastical law. The law department existed nearly exclusively for some time after the university's formation and remained its most important department throughout its existence.[110]

In 1413 Antipope John XXIII founded the University's department of theology, which for quite some time had only a few students. It was not until the 16th and 17th centuries that the school developed a department of medicine. The Bishop of Avignon was chancellor of the university from 1303 to 1475. After 1475 the bishop became an Archbishop but remained chancellor of the university. The papal vice-legate, generally a bishop, represented the civil power (in this case the pope) and was chiefly a judicial officer who ranked higher than the Primicerius (Rector).[110]

The Primicerius was elected by the Doctors of Law. In 1503 the Doctors of Law had 4 Theologians and in 1784 two Doctors of Medicine added to their ranks. Since the Pope was the spiritual head and, after 1348, the temporal ruler of Avignon, he was able to have a great deal of influence in all university affairs. In 1413 John XXIII granted the university extensive special privileges, such as university jurisdiction and tax exempt status. Political, geographical, and educational circumstances in the latter part of the university's existence caused it to seek favour from Paris rather than Rome for protection. During the chaos of the French Revolution the university started to gradually disappear and, in 1792, the university was abandoned and closed.[110]

Modern university

A university annex of the Faculté des Sciences d'Aix-Marseille was opened in Avignon in 1963. Over the next 20 years various changes were made to the provision of tertiary education in the town until finally in 1984 the Université d'Avignon et des Pays de Vaucluse was created. This was nearly 200 years after the demise of the original Avignon university.[111] The main campus lies to the east of the city centre within the city ramparts. The university occupies the 18th century buildings of the Hôpital Sainte-Marthe. The main building has an elegant façade with a central portico. The right hand side was designed by Jean-Baptiste Franque and built between 1743 and 1745. Franque was assisted by his son François in the design of the portico. The hospital moved out in the 1980s and, after major works, the building opened for students in 1997.[112][113] In 2009-2010 there were 7,125 students registered at the university.[114]

People who were born or died in Avignon

- Trophime Bigot, French painter, died in Avignon, 1650[115]

- Jean Alesi, racing car driver, born in Avignon, 1964

- Henri Bosco, writer, born in Avignon, 1888[116]

- Pierre Boulle, author of The Bridge over the River Kwai and Planet of the Apes, born in Avignon, 1912

- Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1664), Jesuit missionary, born in Avignon[117]

- Pierre-Esprit Radisson, fur trader and explorer, born in Avignon, 1636 or 1640

- Bernard Kouchner, politician, born in Avignon, 1936

- Mireille Mathieu, singer, born in Avignon, 1946

- Olivier Messiaen, composer, born in Avignon, 1908

- Joseph Vernet, painter, born in Avignon, 1714[118]

- John Stuart Mill, liberal philosopher, died at Avignon in 1873 and is buried in the cemetery[119]

- Dorothea von Rodde-Schlözer, artist and scholar, died in Avignon in 1825

- Michel Trinquier, painter, born in Avignon, 1930

- René Girard, historian, literary critic, philosopher, and author, born in Avignon, 1923

- Daniel Arsand, writer and publisher, born in Avignon, 1950

- Cédric Carrasso, footballer, born in Avignon, 1981

See also

- Avenir Club Avignonnais, a French association football team

- Battle of Avignon (737)

- Councils of Avignon, councils of the Roman Catholic Church

Notes

- ^ Identical solar representations exist existent in rocks and cave sites along the Provençal coast at Mont-Bego, in the Iberian peninsula, and in the Moroccan Sahara.

- ^ In Provence, these anthropomorphic stèles (at Lauris, Orgon, Senas, Trets, Goult, Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, and Avignon), date from 3000BC to 2800BC and were from the "civilisation of Lagoza". They were witnesses to an agriculture that became predominant in the lower valleys of the Rhône and the Durance.

- ^ An expression used by the Pseudo-Aristotle in Marvellous Stories

- ^ The name used by Dionysius of Périocète in Description of the inhabited world.

- ^ He is sometimes listed as Julius.

- ^ Nectarius, first historical Bishop of Avignon, went to Rome during his episcopate to arbitrate differences between Hilary of Arles and Pope Leo I.

- ^ This aid is mentioned in the canons of the Council of the Seven Provinces in Béziers which was held in 472 under the presidency of Sidonius Apollinaris, Bishop of Clermont. The prelate of Lyon also revitalised Arles, Riez, Orange, Saint-Paul-Trois-Châteaux, Alba, and Valence - cities starving from the pillage of the Burgundians.

- ^ Historians have given the name austraso-provençal to the literary circle.

- ^ Riez did not have a bishop for 229 years, Vence for 218 years, Saint-Paul-les-Trois-Châteaux and Orange for 189 years (the two dioceses having been united), and both Carpentras and Digne for 138 years.

- ^ Of the 23 Provençal seats, only 11 bishops were present.[15]

- ^ Boson was apparently was a Carolingian through Ermangarde, sister of Charles le Chauve.

- ^ Louis the Blind, son of Boson I, was King of Provence from 890 to 928. He became King of Italy in 900 then was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in February 901 in Rome by Pope Benedict IV. His rival, the Italian Béranger de Frioul made him put out his eyes in 905 for perjury.

- ^ Ecclesia suae in honore Sancte Marie Dei genitris dicatae noted the cartulary of Notre-Dame of Doms.

- ^ These were noted in the Cartulary of Notre-Dame of Doms: genetrici ejus regine celorum et terre interemate Marie virgini protomartyri etiam beatissimo Stephano. On 18 August 918 Louis the Blind, in a diploma of new restitution in favour of Fulcherius, mentioned the cathedral complex of Avignon with two churches and a baptistry: "Matris ecclesie Sancte Marie et Sancti Stephami ac Sancti Johannis Baptiste".

- ^ Fraxinetum has been identified as Garde-Freinet.

- ^ Maïeul was the younger son of Foucher de Valensole, one of the richest lords in Provincia, and Raymonde, daughter of Count Maïeul I of Narbonne, who were married at Avignon.

- ^ Eyric was the eldest son of Foucher de Valensole and of Raymonde de Narbonne and it was his son Humbert de Caseneuve that the noble house of Agoult-Simiane came.

- ^ Castrum Caneto corresponds to Cannet-des-Maures.

- ^ Provençal tradition says that the first two were the mistral and the Parliament of Aix

- ^ The épicentre was at Lambesc - a village in Bouches-du-Rhône.

- ^ This area has had the INRA Centre which carries out scientific research in engineering environmental management for cultivated land and forests since 1953.

- ^ Cleaning company.

References

- ^ "84007-Avignon: Legal Population of the commune 2011". Insee (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques). Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ Avignon in the Competition for Towns and Villages in Bloom Archived 10 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b c Rostaing 1994, p. 30.

- ^ a b Dauzat & Rostaing 1963, p. 1689.

- ^ Robert Bourret, French-Occitan Dictionary, Éd. Lacour, Nîmes, 1999, p. 59. Template:Fr icon

- ^ Xavier de Fourvière & Rupert 1902, p. 62.

- ^ Tell me about Avignon, Towens and Country of Art and history, Ministry of Culture, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Gagnière & Granier 1976.

- ^ Étienne de Byzance, The Ethnics in summary, Aug. Meineke, Berlin, 1849 Template:Fr icon

- ^ History of the origin of the name, Avignon official website, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia and Pomponius Mela in his Of Choregraphia depicted Avignon as the capital of Cavares.

- ^ The Origins of Avignon, horizon-provence website, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Pomponius Mela, Description of the World, Book II, V.

- ^ French article on the Tribu Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b Février 1989, p. 485.

- ^ a b Baratier 1969, p. 106.

- ^ Mc Kitterick, 267.

- ^ a b Chronology of the cathars Archived 4 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Template:Fr icon

- ^ Favier 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Favier 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Favier 2006, p. 131.

- ^ Favier 2006, p. 138.

- ^ Favier 2006, p. 145.

- ^ a b Renouard 2004, pp. 99–105.

- ^ Renouard 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Renouard 2004, p. 101.

- ^ a b Guillemain 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Raymond Dugrand and Robert Ferras, The Great Encyclopedia, Larousse, Paris, 1972, Vol. III, p. 1355, ISBN 2-03-000903-2 Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b Favier 2006, pp. 150–153.

- ^ Renouard 2004, p. 59.

- ^ Stephens 1897, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Cohn, Samuel K Jr (2008). "Epidemiology of the Black Death and Successive Waves of Plague". Medical history. Supplement. 27 (27): 74–100. PMC 2630035. PMID 18575083.

- ^ Girard 1958, p. 40.

- ^ a b Catholic Church in Avignon - Historical Notice, Diocese of Avignon, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Letters patent of Louis XI, Plessis-du-Parc-lèz-Tours, 10 October 1479 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Miquel 1980, p. 233.

- ^ Miquel 1980, p. 254.

- ^ Chronology of the years around Agrippa of Aubigné Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, agrippadaubigne website, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Description of Avignon, 1829 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Eugène Hatin, Historical Bibliography and critique of the French periodical press, Firmin Didot Frères, Paris, 1866, p. 306, consulted on 17 October 2011 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Ceccarelli 1989, p. 60.

- ^ Fantin-Desodoards 1807, p. 77.

- ^ Fantin-Desodoards 1807, p. 64.

- ^ Fantin-Desodoards 1807, p. 79.

- ^ Fantin-Desodoards 1807, p. 89.