Bulgaria

Republic of Bulgaria Република България | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Съединението прави силата (Bulgarian) "Saedinenieto pravi silata" (transliteration) "Unity makes strength"1 | |

| Anthem: Мила Родино (Bulgarian) [Mila Rodino] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (transliteration) Dear Homeland | |

![Location of Bulgaria (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) – in the European Union (green) – [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/EU-Bulgaria.svg/250px-EU-Bulgaria.svg.png) Location of Bulgaria (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Sofia |

| Official languages | Bulgarian |

| Ethnic groups | 85% Bulgarians, 9% Turkish, 5% Roma, 1% other groups[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Bulgarian |

| Government | Parliamentary democracy |

| Georgi Parvanov | |

| Boyko Borisov | |

| Formation | |

| 632–680 | |

| 681[2] | |

| 681–1018 | |

| 1185–1396 | |

| 1396 | |

| 3 March 1878 | |

| 6 September 1885 | |

| 22 September 1908 from Ottoman Empire | |

• Recognized | 06 April 1909 |

| Area | |

• Total | 110,993.6 km2 (42,854.9 sq mi) (104th) |

• Water (%) | 0.3 |

| Population | |

• 2009 estimate | 7,576,751[3] (95th) |

• 2001 census | 7,932,984 |

• Density | 68.5/km2 (177.4/sq mi) (124th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $90.869 billion[4] (66rd) |

• Per capita | $12,067[4] (68th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate |

• Total | $50.620 billion[4] (71th) |

• Per capita | $6,722[4] (72th) |

| Gini (2008) | 29.8[5] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2010) | Error: Invalid HDI value (58th) |

| Currency | Lev2 (BGN) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | 359 |

| ISO 3166 code | BG |

| Internet TLD | .bg3 |

| |

Bulgaria (Template:Pron-en Template:Lang-bg, officially the Republic of Bulgaria (Република България, Republika Bulgaria,[7] [rɛˈpublikɐ bɤ̞ɫˈɡarijɐ]), is a country in Southern Europe. Bulgaria borders five other countries: Romania to the north (mostly along the Danube), Serbia and the Republic of Macedonia to the west, and Greece and Turkey to the south. The Black Sea defines the extent of the country to the east.

With a territory of 110,994 square kilometers (42,855 sq mi), Bulgaria ranks as the 16th-largest country in Europe. Several mountainous areas define the landscape, most notably the Stara Planina (Balkan) and Rodopi mountain ranges, as well as the Rila range, which includes the highest peak in the Balkan region, Musala. In contrast, the Danubian plain in the north and the Upper Thracian Plain in the south represent Bulgaria's lowest and most fertile regions. The 378-kilometer (235 mi) Black Sea coastline covers the entire eastern bound of the country. Bulgaria's capital city and largest settlement is Sofia, with a permanent population of 1,378,000 people.[8]

The emergence of a unified Bulgarian ethnicity and state dates back to the 7th century AD. All Bulgarian political entities that subsequently emerged preserved the traditions (in ethnic name, language and alphabet) of the First Bulgarian Empire (681–1018), which at times covered most of the Balkans and eventually became a cultural hub for the Slavs in the Middle Ages.[9] With the decline of the Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396/1422), Bulgarian territories came under Ottoman rule for nearly five centuries. The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 led to the establishment of a Third Bulgarian state as a principality in 1878, which gained its full sovereignty in 1908.[10] In 1945, after World War II, it became a communist state and was a part of the Eastern Bloc until the political changes in Eastern Europe in 1989/1990, when the Communist Party allowed multi-party elections and Bulgaria undertook a transition to parliamentary democracy and free-market capitalism with mixed results.

Bulgaria functions as a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic. A member of the European Union, NATO, the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, it has a high Human Development Index of 0.743, ranking 58th in the world in 2010.[11]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Prehistoric cultures in the Bulgarian lands include the Neolithic Hamangia culture and Vinča culture (6th to 3rd millennia BC), the eneolithic Varna culture (5th millennium BC; see also Varna Necropolis), and the Bronze Age Ezero culture. The Karanovo chronology serves as a gauge for the prehistory of the wider Balkans region.

The Thracians, one of the three primary ancestral groups of modern Bulgarians, lived separated in various tribes until King Teres united most of them around 500 BC in the Odrysian kingdom. They were eventually subjugated by Alexander the Great and later by the Roman Empire. After migrating from their original homeland, the easternmost South Slavs settled on the territory of modern Bulgaria during the 6th century and assimilated the Hellenized or Romanised Thracians. Eventually the Bulgar élite incorporated all of them into the First Bulgarian Empire.[12] By the 9th century, Bulgars and Slavs were mutually assimilated.[13]

First Bulgarian Empire

Asparukh, heir of Old Great Bulgaria's khan Kubrat, migrated with several Bulgar tribes to the lower courses of the rivers Danube, Dniester and Dniepr (known as Ongal) after his father's state was subjugated by the Khazars. He conquered Moesia and Scythia Minor (Dobrudzha) from the Byzantine Empire, expanding his new kingdom further into the Balkan Peninsula.[14] A peace treaty with Byzantium in 681 and the establishment of the Bulgarian capital of Pliska south of the Danube mark the beginning of the First Bulgarian Empire.

Succeeding rulers strengthened the Bulgarian state – Tervel (700/701–718/721), stabilized the borders and established Bulgaria as a major military power by defeating a 26,000-strong Arab army in 717, thereby eliminating the threat of a full-scale Arab invasion of Eastern and Central Europe.[15]

Krum (802–814),[16] doubled the country's territory, killed emperor Nicephorus I in the Battle of Pliska,[17] and introduced the first written code of law, valid for both Slavs and Bulgars. Boris I the Baptist (852–889) abolished Tengriism, replacing it with Eastern Orthodox Christianity in 864,[18] and introduced the Cyrillic alphabet, developed at the literary schools of Preslav and Ohrid.[19] The Cyrillic alphabet, along with Old Bulgarian language, fostered the intellectual written language (lingua franca) for Eastern Europe, known as Church Slavonic. Emperor Simeon I the Great's rule (893–927) saw the largest territorial expansion of Bulgaria in its history.[20] Simeon managed to gain a military supremacy over the Byzantine Empire, demonstrated by the Battle of Anchialos (917), one of the bloodiest battles in the Middle ages[21] as well as one of his most decisive victories. His reign also saw Bulgaria develop a rich, unique Christian Slavonic culture, which became an example for other Slavonic peoples in Eastern Europe and also fostered the continued existence of the Bulgarian nation despite forces that threatened to tear it apart.

After Simeon's death, Bulgaria declined during the mid-10th century, weakened by wars with Croatians, Magyars, Pechenegs and Serbs, and the spread of the Bogomil heresy.[22][23] This resulted in consecutive Rus' and Byzantine invasions, which ended with the seizure of the capital Preslav by the Byzantine army.[24] Under Samuil, Bulgaria somewhat recovered from these attacks and even managed to conquer Serbia, Bosnia[25] and Duklja,[26] but this ended in 1014, when Byzantine Emperor Basil II ("the Bulgar-Slayer") defeated its armies at Klyuch.[27] Samuil died shortly after the battle, on 15 October 1014,[27] and by 1018 the Byzantine Empire fully conquered the First Bulgarian Empire, putting it to an end.

Byzantine rule and Second Bulgarian Empire

Basil II managed to prevent rebellions by retaining the local rule of the Bulgarian nobility, who were incorporated into Byzantine aristocracy as archons or strategoi,[28] guaranteeing the indivisibility of Bulgaria in its former geographic borders and recognising the autocephaly of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid.[29] After his death Byzantine domestic policies changed, which led to a series of unsuccessful rebellions, the largest being led by Peter II Delyan. However, it was not until 1185 when Asen dynasty nobles Ivan Asen I and Peter IV organized a major uprising and succeeded in reestablishing the Bulgarian state, marking the beginning of the Second Bulgarian Empire.

The Asen dynasty set up its capital in Veliko Tarnovo. Kaloyan, the third of the Asen monarchs, extended his dominions to Belgrade, Nish and Skopie; he acknowledged the spiritual supremacy of the Pope, and received a royal crown from a papal legate.[12] Cultural and economic growth persisted under Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), who extended Bulgaria's control over Albania, Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace.[30] The achievements of the Tarnovo artistic school as well as the first coins to be minted by a Bulgarian ruler were only a few signs of the empire's welfare at that time.[12]

The Asen dynasty ended in 1257, and due to Tatar invasions (beginning in the later 13th century), internal conflicts, and constant attacks from the Byzantines and the Hungarians, the country's military and economic might declined. By the end of the 14th century, factional divisions between Bulgarian feudal landlords (bolyari) and the spread of Bogomilism had caused the Second Bulgarian Empire to split into three small tsardoms (At Vidin, Tarnovo and Karvuna) and several semi-independent principalities that fought among themselves, and also with Byzantines, Hungarians, Serbs, Venetians and Genoese. In the period 1365–1370, the Ottoman Turks, who had already started their invasion of the Balkans, conquered most Bulgarian towns and fortresses south of the Balkan Mountains and began their northwards conquest.[31]

Fall of the Second Empire and Ottoman rule

In 1393, the Ottomans captured Tarnovo, the capital of the Second Bulgarian Empire, after a three-month siege. In 1396, the Vidin Tsardom fell after the defeat of a Christian crusade at the Battle of Nicopolis. With this, the Ottomans finally subjugated and occupied Bulgaria.[32][33][34] During their rule, the Bulgarian population suffered greatly from oppression, intolerance and misgovernment.[35] The nobility was eliminated and the peasantry enserfed to Ottoman masters[36] while Bulgarians lacked judicial equality with the Ottoman Muslims and had to pay much higher taxes than them.[37] Bulgarian culture became isolated from Europe, its achievements destroyed, and the educated clergy fled to other countries.[38]

Throughout the nearly five centuries of Ottoman rule, the Bulgarian people responded to the oppression by strengthening the haydut ("outlaw") tradition,[13] and attempted to reestablish their state by organizing several revolts, most notably the First and Second Tarnovo Uprisings (1598 / 1686) and Karposh's Rebellion (1689). The National awakening of Bulgaria became one of the key factors in the struggle for liberation, resulting in the 1876 April uprising —the largest and best-organized Bulgarian rebellion. Though crushed by the Ottoman authorities – in reprisal, the Turks massacred some 15,000 Bulgarians[13] – the uprising prompted the Great Powers to take action. They convened the Constantinople Conference in 1876, but their decisions were rejected by the Ottoman authorities, which allowed the Russian Empire to seek a solution by force without risking military confrontation with other Great Powers (as had happened in the Crimean War of 1854 to 1856).

Third Bulgarian State

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, resulted in the defeat of Ottoman forces by the Russian army (supported by Bulgarian and Romanian volunteer forces) and the Treaty of San Stefano (3 March 1878), which set up an autonomous Bulgarian principality. The Great Powers immediately rejected the treaty, fearing that such large country in the Balkans might threaten their interests. The subsequent Treaty of Berlin (1878) provided for a much smaller autonomous state comprising Moesia and the region of Sofia.[39] The Bulgarian principality proclaimed itself a fully independent state on 5 October (22 September O.S.), 1908, after it won a war against Serbia and incorporated the semi-autonomous Ottoman territory of Eastern Rumelia.

In the years following the achievement of complete independence Bulgaria became increasingly militarized, and was referred to as "the Prussia of the Balkans"[40][41] In 1912 and 1913, Bulgaria became involved in the Balkan Wars, first entering into conflict alongside Greece, Serbia and Montenegro against the Ottoman Empire. The First Balkan War (1912–1913) proved a success for the Bulgarian army, but a conflict over the division of Macedonia arose between the victorious allies. The Second Balkan War (1913) was a disastrous defeat for Bulgaria, which was attacked almost simultaneously by its neighbors. In World War I, Bulgaria again found itself fighting on the losing side as a result of its alliance with the Central Powers. Despite achieving several decisive victories (at Doiran, Monastir and again at Doiran in 1918), Bulgaria lost the war and suffered significant territorial losses.[13] The total amount of casualties from these three wars was 412,000–152,000 military deaths and 260,000 wounded. A wave of 253,000[42] officially registered refugees, who represented 6% of the pre-war population of the country, and an unclear number of unregistered refugees put an additional strain on the already ruined national economy.

Following these losses, in the 1920s and 1930s the country suffered political unrest, which led to the establishment of a royal authoritarian dictatorship by Tsar Boris III (reigned 1918–1943). After regaining control of Southern Dobrudzha in 1940, Bulgaria entered World War II in 1941 as a member of the Axis. However, it declined to participate in Operation Barbarossa and never declared war on the USSR, and saved its Jewish population from deportation to concentration camps by repeatedly postponing compliance with German demands, offering various rationales.[43] In the summer of 1943 Boris III died suddenly, an event which pushed the country into political turmoil as the war turned against Nazi Germany and the Communist guerilla movement gained more power.[44]

In September 1944 the Communist-dominated Fatherland Front took power, following strikes and unrest, ending the alliance with Nazi Germany and joining the Allied side until the end of the war in 1945. The Communist uprising of 9 September 1944 led to the abolishment of monarchic rule, but it was not until 1946 that a people's republic was established. It came under the Soviet sphere of influence, with Georgi Dimitrov (1946–1949) as the foremost Bulgarian political leader. Bulgaria installed a Soviet-type planned economy with some market-oriented policies emerging on an experimental level[46] under Todor Zhivkov (1954–1989). By the mid 1950s standards of living rose significantly.[47] Lyudmila Zhivkova, daughter of Zhivkov, promoted Bulgaria's national heritage, culture and arts worldwide.[48] On the other hand, an assimilation campaign of the late 1980s directed against ethnic Turks resulted in the emigration of some 300,000 Bulgarian Turks to Turkey,[49][50] which caused a significant drop in agricultural production due to the loss of labor force.[51] On 10 November 1989, the Bulgarian Communist Party gave up its political monopoly, Zhivkov resigned, and Bulgaria embarked on a transition from a single-party republic to a parliamentary democracy.

In June 1990 the first free elections took place, won by the moderate wing of the Communist Party (the Bulgarian Socialist Party — BSP). In July 1991, a new constitution that provided for a relatively weak elected President and for a Prime Minister accountable to the legislature, was adopted. Economic planning was scrapped and private initiative was legalized. The new system eventually failed to improve both the living standards and create economic growth — the average quality of life and economic performance actually remained lower than in the times of Communism well into the early 2000s.[52] A reform package introduced in 1997 restored positive economic growth, but led to rising social inequality. Bulgaria became a member of NATO in 2004 and of the European Union in 2007. The US Library of Congress Federal Research Division reported it in 2006 as having generally good freedom of speech and human rights records,[53] while Freedom House listed Bulgaria as "free" in 2010, giving it scores of 2 for political rights and 2 for civil liberties.[54]

Geography

Geographically and in terms of climate, Bulgaria features notable diversity, with the landscape ranging from the Alpine snow-capped peaks in Rila, Pirin and the Balkan Mountains to the mild and sunny Black Sea coast; from the typically continental Danubian Plain (ancient Moesia) in the north to the strong Mediterranean climatic influence in the valleys of Macedonia and in the lowlands in the southernmost parts of Thrace.

Relief and natural resources

Bulgaria comprises portions of the separate regions known in classical times as Moesia, Thrace, and Macedonia. About 30% of the land is made up of plains, while plateaus and hills account for 41%.[55] The mountainous southwest of the country has two alpine ranges — Rila and Pirin — and further east stand the lower but more extensive Rhodope Mountains. The Rila range includes the highest peak of the Balkan Peninsula, Musala, at 2,925 meters (9,596 ft);[56] the Balkan mountain chain runs west-east through the middle of the country, north of the Rose Valley. Hilly countryside and plains lie to the southeast, along the Black Sea coast, and along Bulgaria's main river, the Danube, to the north. Strandzha forms the tallest mountain in the southeast. Few mountains and hills exist in the northeast region of Dobrudzha.

Bulgaria has large deposits of bauxite, copper, lead, zinc, bismuth and manganese. Smaller deposits exist of iron, gold, silver, uranium, chromite, nickel, and others. Bulgaria has abundant non-metalliferous minerals such as rock-salt, gypsum, kaolin and marble.

Hydrography and climate

The country has a dense network of about 540 rivers, most of them—with the notable exception of the Danube—short and with low water-levels.[57] Most rivers flow through mountainous areas. The longest river located solely in Bulgarian territory, the Iskar, has a length of 368 kilometers (229 mi). Other major rivers include the Struma and the Maritsa River in the south.

Bulgaria overall has a temperate climate, with cold winters and hot summers. The barrier effect of the Balkan Mountains has some influence on climate throughout the country–northern Bulgaria experiences lower temperatures and receives more rain than the southern lowlands.

Precipitation in Bulgaria averages about 630 millimeters (24.8 in) per year.[59] In the lowlands rainfall varies between 500 and 800 millimeters (19.7 and 31.5 in), and in the mountain areas between 1,000 and 2,500 millimeters (39.4 and 98.4 in) of rain falls per year. Drier areas include Dobrudja and the northern coastal strip, while the higher parts of the Rila, Pirin, Rhodope Mountains, Stara Planina, Osogovska Mountain and Vitosha receive the highest levels of precipitation.

Environment and wildlife

Bulgaria has signed and ratified the Kyoto protocol[61] and has achieved a 30% reduction of carbon dioxide emissions from 1990 to 2009, completing the protocol's objectives.[62] However, pollution from outdated factories and metallurgy works, as well as severe deforestation (mostly caused by illegal logging), continue to be major problems.[63] Urban areas are particularly affected mostly due to energy production from coal-based powerplants and automobile traffic,[64][65] while pesticide usage in the agriculture and antiquated industrial sewage systems have resulted in extensive soil and water pollution with chemicals and detergents.[66] In addition, Bulgaria remains the only EU member which does not recycle municipal waste,[67] although an electronic waste recycling plant was put in operation in June 2010.[68] The situation has improved in recent years, and several government-funded programs have been initiated in order to reduce pollution levels.[66]

Three national parks, eleven nature parks[69] and seventeen biosphere reserves[70] exist on Bulgaria's territory. Nearly 35% of its land area consists of forests.[71] The brown bear and the jackal[72] are prominent mammals, while the Eurasian lynx, the Eastern imperial eagle and the European mink have small, but growing populations.

Politics and law

The National Assembly or Narodno Sabranie (Народно събрание) consists of 240 deputies, each elected for four-year terms by popular vote. The National Assembly has the power to enact laws, approve the budget, schedule presidential elections, select and dismiss the Prime Minister and other ministers, declare war, deploy troops abroad, and ratify international treaties and agreements. The president serves as the head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. While unable to initiate legislation other than constitutional amendments, the President can return a bill for further debate, although the parliament can override the President's veto by vote of a majority of all MPs. Boyko Borisov, leader of the centre-right party Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria, became prime minister on 27 July 2009,[73] and Georgi Parvanov was re-elected as a president in 2005.

The Bulgarian legal system recognizes the Acts of Parliament as a main source of law, and is a typical representative of the Romano-Germanic law family.[74] The judiciary is overseen by the Ministry of Justice, while the Supreme Administrative Court and Supreme Court of Cassation, the highest courts of appeal, rule on the application of laws in lower courts. The Supreme Judicial Council manages the system and appoints judges. Bulgaria's judiciary remains one of Europe's most corrupt and inefficient.[75][76] Law enforcement organisations are mainly subordinate to the Ministry of Interior.[77] The National Police Service is responsible for combating general crime and supporting the operations of other law enforcement agencies, the National Investigative Service and the Central Office for Combating Organized Crime. The Police Service has criminal and financial sections and national and local offices. The Ministry of Interior also heads the Border Police Service and the National Gendarmerie, a specialized branch for anti-terrorist activity, crisis management and riot control. In 2008, the State Agency for National Security, a specialized body for counterintelligence, was established with the aim to eliminate threats to national security.[78] Bulgaria's police force numbers 27,000 officers.[79]

Foreign relations and military

Bulgaria became a member of the United Nations in 1955, and a founding member of OSCE in 1975. As a Consultative Party to the Antarctic Treaty, the country takes part in the administration of the territories situated south of 60° south latitude.[80][81] It joined NATO on 29 March 2004, signed the European Union Treaty of Accession on 25 April 2005,[82][83] and became a full member of the European Union on 1 January 2007.[84] In April 2006 Bulgaria and the United States of America signed a defence cooperation agreement providing for the usage of the Bezmer and Graf Ignatievo air bases, the Novo Selo training range, and a logistics centre in Aytos as joint military facilities. Foreign Policy magazine lists Bezmer Air Base as one of the six most important overseas facilities used by the USAF.[85]

The military of Bulgaria, an all-volunteer body, consists of three services – land forces, navy and air force. As a NATO member, the country maintains a total of 645 troops deployed abroad.[86] Historically, Bulgaria deployed significant numbers of military and civilian advisors in socialist-oriented countries, such as Nicaragua[87] and Libya (more than 9,000 personnel).[88]

Following a series of reductions beginning in 1990, the active troops today number about 32,000,[89] down from 152,000 in 1988,[90] and are supplemented by a reserve force of 303,000 soldiers and officers and paramilitary forces, numbering 34,000.[91] The inventory includes highly capable Soviet equipment, such as MiG-29 fighters, SA-10 Grumble SAMs and SS-21 Scarab short-range ballistic missiles. Military spending in 2009 cost $1.19 billion.[92]

Administrative divisions

Between 1987 and 1999 Bulgaria consisted of nine provinces (oblasti, singular oblast); since 1999, it has consisted of twenty-eight. All take their names from their respective capital cities:

The provinces subdivide into 264 municipalities.

Economy

Bulgaria has an industrialized, open free-market economy, with a large, moderately advanced private sector and a number of strategic state-owned enterprises. The World Bank classifies it as an "upper-middle-income economy".[93] Bulgaria has experienced rapid economic growth in recent years[update], even though it continues to rank as the lowest-income member state of the EU. According to Eurostat data, Bulgarian PPS GDP per capita stood at 43 per cent of the EU average in 2008.[94] The Bulgarian lev is the country's national currency. The lev is pegged to the euro at a rate of 1.95583 leva for 1 euro.[95]

In 2008, GDP (PPP) was estimated at $95.2 billion, with a per capita value of $13,100.[96] The economy relies primarily on industry, although the services sector increasingly contributes to GDP growth. Bulgaria produces a significant amount of manufactures and raw materials such as iron, copper, gold, bismuth, coal, electronics, refined petroleum fuels, vehicle components, firearms and construction materials. The total labor force amounts to 3.2 million people.[97] Since a hyperinflation crisis in 1996/1997, inflation and unemployment rates have fallen to 7.2% and 6.3%, respectively, in 2008. Corruption in the public administration and a weak judiciary have also hampered Bulgaria's economic development.[98]

Amidst the Financial crisis of 2007–2010, unemployment rates increased to 9.1% in 2009, while GDP growth contracted from 6.3% (2008) to −4.9% (2009). The crisis had a negative impact mostly on industry, with a 10% decline in the national industrial production index, a 31% drop in mining, and a 60% drop in "ferrous and metal production".[100] The International Monetary Fund predicts a 0.2% overall growth for the Bulgarian economy in 2010, and 2% in 2011.[101]

Although it has relatively few reserves of fossil fuels, Bulgaria's well-developed energy sector and strategic geographical location make it a key European energy hub.[102] A single nuclear power station with two active 1,000 MW reactors satisfies 34% of the country's energy needs,[103] and another nuclear power station with a projected capacity of 2,000 MW is under construction. Thermal power stations, such as those at the Maritsa Iztok Complex, also have a large share in electricity production. Recent years[update] have seen a rapid increase in electricity production from renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power.[104] Large-scale prospects for wind energy development[105] have spurred the construction of numerous wind farms, making Bulgaria one of the fastest-growing wind energy producers in the world.[106]

Bulgaria's mining industry is a significant contributor to economic growth and is worth $760 mln.[107] In Europe, the country ranks as the 3rd-largest copper producer,[108] 6th-largest zinc producer,[109] and 9th-largest coal producer,[110] and is the 9th-largest bismuth producer in the world.[111] Ferrous metallurgy, including steel and pig iron production, takes place mostly in Kremikovtsi, Pernik and Debelt.

About 14% of the total industrial production relates to machine building, and 20% of the workforce is employed in this field.[112]

In contrast with the industrial sector, agriculture in Bulgaria has marked a decline since the beginning of the 2000s, with agricultural production in 2008 amounting to only 66% of that between 1999 and 2001.[113] Overall, Bulgaria's agricultural sector has dwindled since 1990, with cereal and vegetable yields dropping with nearly 40% by 1999.[114] A five-year modernization and development program was launched in 2007, aimed at strengthening the sector by investing a total of 3.2 billion euro.[115] Specialized equipment amounts to some 25,000 tractors and 5,500 combine harvesters, with a fleet of light aircraft.[116]

Bulgaria remains a major European producer of agricultural commodities such as tobacco (3rd)[117] and raspberries (12th).[118]

Tourism

In 2008 Bulgaria was visited by a total of 8,900,000 people, with Greeks, Romanians and Germans accounting for more than 40% of all visitors.[119] Significant numbers of British, Russian, Dutch, Serbian, Polish and Danish tourists also visit Bulgaria. In 2010, Lonely Planet placed it under 5th place on its top 10 list of travel destinations for 2011.[120]

Main destinations include the capital Sofia, coastal resorts Albena, Sozopol, Nesebar, Golden Sands and Sunny Beach and winter resorts such as Pamporovo, Chepelare, Borovetz and Bansko. The rural tourist destinations of Arbanasi and Bozhentsi offer well-preserved ethnographic traditions. Other popular attractions include the 10th-century Rila Monastery and the 19th-century Euxinograd château.

Infrastructure

Bulgaria occupies a unique and strategically important geographic location. Since ancient times, the country has served as a major crossroads between Europe, Asia and Africa. Five of the ten Trans-European corridors run through its territory.

Bulgaria's national road network has a total length of 102,016 kilometers (63,390 mi), of which 93,855 kilometers (58,319 mi) are paved. Motorways, such as Trakiya, Hemus and Struma, have a total length of 441 km (274 mi). Bulgaria also has 6,500 kilometers (4,000 mi) of railway track, more than 60% of which is electrified, and plans to construct a high-speed railway by 2017, at a cost of €3 bln.[123][124] Sofia and Plovdiv are major air travel hubs, while Varna and Burgas are the principal maritime trade ports.

Science and technology

In 2008 Bulgaria spent 0.4% of its GDP on scientific research,[125] which represents one of the lowest scientific budgets in Europe.[126] Chronic underinvestment in the scientific sector since 1990 forced many scientific professionals to leave the country.[127] Bulgaria has traditions in astronomy, physics, nuclear technology, medical and pharmaceutical research, and maintains a polar exploration program by means of an artificial satellite and a permanent research base. The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (BAS) is the leading scientific institution in the country and employs most of Bulgaria's researchers in its numerous branches.

Bulgarian scientists have made several notable discoveries and inventions, such as the prototype of the digital watch (Peter Petroff); galantamine (Dimitar Paskov);[128][129] the molecular-kinetic theory of crystal formation and growth (formulated by Ivan Stranski) and the space greenhouse (SRI-BAS).[130][131] With major-general Georgi Ivanov flying on Soyuz 33 in 1979, Bulgaria became the 6th country in the world to have an astronaut in space.[132]

Due to its large-scale computing technology exports to COMECON states, in the 1980s Bulgaria became known as the Silicon Valley of the Eastern Bloc.[133] The country ranked 8th in the world in 2002 by total number of ICT specialists, outperforming countries with far larger populations,[134] and it operates the only supercomputer in the Balkan region,[135] an IBM Blue Gene/P, which entered service in September 2008.[136]

Demographics

The National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria estimates the country's population for 2009 at 7,606,000 people. According to the 2001 census,[137] it consists mainly of ethnic Bulgarians (83.9%), with two sizable minorities, Turks (9.4%) and Roma (4.7%).[138] Of the remaining 2.0%, 0.9% comprises some 40 smaller minorities, while 1.1% of the population have not declared their ethnicity.

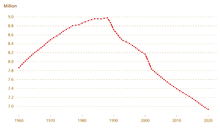

Bulgaria has one of the lowest population growth rates in the world.[139] Negative population growth has occurred since the early 1990s,[140] due to economic collapse, a low birth rate, and high emigration. In 1989 the population comprised 9,009,018 people, gradually falling to 7,950,000 in 2001 and 7,528,000 in 2010.[3] Some 6,700,000 people (~85%) speak Bulgarian,[141] which belongs to the group of South Slavic languages and is the only official language.

Most Bulgarians (82.6%) belong, at least nominally, to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, which gained autocephalous status in 927 AD[142][143] and is the earliest Slavic Orthodox Church.[144][145] Other religious denominations include Islam (12.2%), various Protestant denominations (0.8%) and Roman Catholicism (0.5%); with other Christian denominations (0.2%), and "other" totalling approximately 4%, according to the 2001 census.[146] Bulgaria regards itself officially as a secular state. The Constitution guarantees the free exercise of religion, but appoints Orthodoxy as "a traditional" religion.[147]

Education

The Ministry of Education, Youth and Science oversees education in Bulgaria. All children aged between 7 and 16 must attend full-time education. Six-year-olds can enroll at school at their parents' discretion. The State provides education in its schools free of charge, except for higher education establishments, colleges and universities. The curriculum focuses on eight main subject-areas:[148] Bulgarian language and literature, foreign languages, mathematics, information technology, social sciences and humanities, natural sciences and ecology, music and art, physical education and sports.

Government estimates from 2003 put the literacy rate at 98.6 percent, approximately the same for both sexes. Bulgaria has traditionally had high educational standards,[148] and its students rate second in the world in terms of average SAT Reasoning Test scores and I.Q test scores according to MENSA International.[149]

Healthcare

Bulgaria has a universal, mostly state-funded healthcare system. The National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) pays a gradually increasing portion of the costs of primary healthcare. Employees and employers pay an increasing, mandatory percentage of salaries, with the goal of gradually reducing state support of health care. Between 2002 and 2004, health-care expenditures in the national budget increased from 3.8 percent to 4.3 percent, with the NHIF accounting for more than 60 percent of annual expenditures.[150] In 2010, the healthcare budget amounts to 4.2% of GDP, or about 1.3 billion euro.[151] Bulgaria has 181 doctors per 100,000 people, which is above the EU average.[152] Some of Bulgaria's largest medical facilities are the Pirogov Hospital and the Military Medical Academy of Sofia. Life expectancy is 73.4 years, which is below the European union average.[153]

Urbanization

Most of the population (71%) resides in urban areas.[154] Bulgaria's 20 largest cities have populations as follows:[155]

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sofia | Sofia-Capital | 1,190,256 | 11 | Pernik | Pernik | 66,991 | ||

| 2 | Plovdiv | Plovdiv | 321,824 | 12 | Haskovo | Haskovo | 64,564 | ||

| 3 | Varna | Varna | 311,093 | 13 | Blagoevgrad | Blagoevgrad | 62,810 | ||

| 4 | Burgas | Burgas | 188,242 | 14 | Yambol | Yambol | 60,641 | ||

| 5 | Ruse | Ruse | 123,134 | 15 | Veliko Tarnovo | Veliko Tarnovo | 59,166 | ||

| 6 | Stara Zagora | Stara Zagora | 121,582 | 16 | Pazardzhik | Pazardzhik | 55,220 | ||

| 7 | Pleven | Pleven | 90,209 | 17 | Vratsa | Vratsa | 49,569 | ||

| 8 | Sliven | Sliven | 79,362 | 18 | Asenovgrad | Plovdiv | 45,474 | ||

| 9 | Dobrich | Dobrich | 71,947 | 19 | Gabrovo | Gabrovo | 44,786 | ||

| 10 | Shumen | Shumen | 67,300 | 20 | Kazanlak | Kazanlak | 41,768 | ||

Culture

Traditional Bulgarian culture contains mainly Thracian, Slavic and Bulgar heritage, along with Greek, Roman, Ottoman and Celtic influences.[157] Thracian artifacts include numerous tombs and golden treasures. The country's territory includes parts of the Roman provinces of Moesia, Thrace and Macedonia, and many of the archaeological discoveries date back to Roman times, while ancient Bulgars have also left traces of their heritage in music and in early architecture. Both the First and the Second Bulgarian empires functioned as the hub of Slavic culture during much of the Middle Ages, exerting considerable literary and cultural influence over the Eastern Orthodox Slavic world by means of the Preslav and Ohrid Literary Schools. The Cyrillic alphabet, used as a writing system to many languages in Eastern Europe and Asia, originated in the former around the 9th century AD.[19]

A historical artifact of major importance is the oldest treasure of worked gold in the world, dating back to the 5th millennium BC, coming from the site of the Varna Necropolis.[160][161]

World Heritage Sites

Bulgaria has nine UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the Madara Rider, the Thracian tombs in Sveshtari and Kazanlak, the Boyana Church, the Rila Monastery, the Rock-hewn Churches of Ivanovo, Pirin National Park, Sreburna Nature Reserve and the ancient city of Nesebar.

Art, music and literature

The country has a long-standing musical tradition, traceable back to the early Middle Ages. Yoan Kukuzel (c. 1280–1360) became one of the earliest known composers of Medieval Europe. National folk music has a distinctive sound and uses a wide range of traditional instruments, such as gudulka (гъдулка), gaida (гайда) – bagpipe, kaval (кавал) and tupan (тъпан). Bulgarian classical music is represented by composers such as Emanuil Manolov, Pancho Vladigerov, Marin Goleminov and Georgi Atanasov, opera singers Boris Hristov and Raina Kabaivanska, and pianists Alexis Weissenberg and Vesselin Stanev.

Bulgaria has a rich religious visual arts heritage, especially in frescoes, murals and icons, many of them produced by the medieval Tarnovo Artistic School.[162]

One of the earliest pieces of Slavic literature were created in Medieval Bulgaria, such as The Didactic Gospel by Constantine of Preslav and An Account of Letters by Chernorizets Hrabar, both written c. 893. Notable Bulgarian authors include late Romantic Ivan Vazov, Symbolists Pencho Slaveykov and Peyo Yavorov, Expressionist Geo Milev, science fiction writer Pavel Vezhinov, novelist Dimitar Dimov and postmodernist Alek Popov, best known for his novel Mission London and its successful movie adaptation.[163] German-language writer Elias Canetti was the only Bulgarian to win the Nobel Prize (Literature, 1981).[164]

Media

The media in Bulgaria has a record of unbiased reporting.[166] The written media have no legal restrictions and newspaper publishing is entirely liberal.[167] The extensive freedom of the press means that no exact number of publications can be established, although some research put an estimate of around 900 print media outlets for 2006.[167] The largest-circulation daily newspapers include Dneven Trud and 24 Chasa.[167]

Non-printed media sources, such as television and radio, are overseen by the Council for Electronic Media (CEM), an independent body with the authority to issue broadcasting licenses. Apart from a state-operated national television channel, radio station and the Bulgarian News Agency, a large number of private television and radio stations exist. However, most Bulgarian media experience a number of negative trends, such as general degradation of media products, self-censorship and economic or political pressure.[168]

Internet media are growing in popularity due to the wide range of available opinions and viewpoints, lack of censorship and diverse content.[168] Since 2000, a rapid increase in the number of Internet users has occurred. In 2000, they numbered 430,000, growing to 1,545,100 in 2004, and 3.4 million (48% penetration rate) in 2010.[169]

Cuisine

Yogurt (кисело мляко kiselo mlyako), lukanka (луканка), banitsa (баница), shopska salad (шопска салата), lyutenitsa (лютеница), sirene (сирене) and kozunak (козунак) give Bulgaria a distinctive cuisine. Owing to the relatively warm climate and complex geography affording excellent growth conditions for a variety of vegetables, herbs and fruits, Bulgarian cuisine is diverse. Most dishes are oven baked, steamed, or in the form of stew. Deep-frying is uncommon, but grilling - especially different kinds of meats - is widely practiced. Pork is the most common meat, followed by chicken and lamb. Oriental dishes such as moussaka, gyuvech, and baklava are widely consumed. Bulgarian cuisine is also noted for the quality of dairy products and salads, as well as the variety of wines and local alcoholic drinks such as rakiya, mastika and menta.

Exports of Bulgarian wine go worldwide, and until 1990 the country exported the world's second-largest total of bottled wine. As of 2007, 200,000 tonnes of wine were produced annually,[170] the 20th-largest total in the world.[171] Among the more prominent local sorts are Dimiat and Mavrud.

Sports

Bulgaria performs well in sports such as volleyball, wrestling, weight-lifting, canoeing, rowing, shooting sports, gymnastics, chess, and recently, sumo wrestling and tennis. The country fields one of the leading men's volleyball teams in Europe and in the world, ranked 6th in the world according to the 2010 FIVB rankings,[172] while the women's volleyball team finished second in European League 2010.[173][174]

Football has become by far the most popular sport in the country. Dimitar Berbatov (Manchester United) is one of the most famous Bulgarian football players of the 21st century, while Hristo Stoichkov, twice winner of the European Golden Shoe, is the most successful Bulgarian player of all time.[175][176] Prominent domestic football clubs include PFC CSKA Sofia[177][178] and PFC Levski Sofia. Bulgaria's best performance at World Cup finals came in 1994, with a 4th place.

Bulgaria participates both in the Summer and Winter Olympics, and its first Olympic appearance dates back to the first modern Olympic games in 1896, represented by Swiss gymnast Charles Champaud. Since then the country has appeared in most Summer Olympiads, and by 2010 had won a total of 218 medals: 52 gold, 86 silver, and 80 bronze, which puts it at 24th place in the all-time ranking.

See also

- List of twin towns and sister cities in Bulgaria

- List of Bulgarian monarchs

- Bulgarian resistance movement during World War II

Notes

- ^ "Census 2001, Population by Districts and Ethnic Groups as of 01.03.2001". Nsi.bg. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Bulgaria (07/08)". State.gov. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ a b NSI population table as of 2010

- ^ a b c d "Bulgaria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ "Distribution of family income – Gini index". The World Factbook. CIA. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2010" (PDF). United Nations. 2010. Retrieved 5 November 2010.

- ^ Закон за транслитерацията, чл.6

- ^ "Population table by permanent and present address" (in Bulgarian). Head Direction of Residential Registration and Administrative Service. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^

Human Resource Development Centre. "Bulgaria in the European Union" (PDF). Sofia: EuroGuidance. p. 20. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

[..] Bulgaria, the cultural center of the medieval Slavs[...]

- ^ Crampton, R.J., Bulgaria, 2007, pp.174, Oxford University Press

- ^ Human development index trends, Human development indices by the United Nations. Retrieved on November 26, 2010

- ^ a b c s:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Bulgaria/History

- ^ a b c d "Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Runciman, p. 26

- ^ C. de Boor (ed), Theophanis chronographia, vol. 1. Leipzig: Teubner, 1883 (repr. Hildesheim: Olms, 1963), 397, 25–30 (AM 6209)"φασί δε τινές ότι και ανθρώπους τεθνεώτας και την εαυτών κόπρον εις τα κλίβανα βάλλοντες και ζυμούντες ήσθιον. ενέσκηψε δε εις αυτούς και λοιμική νόσος και αναρίθμητα πλήθη εξ αυτών ώλεσεν. συνήψε δε προς αυτούς πόλεμον και τον των Βουλγάρων έθνος, και, ως φασίν οι ακριβώς επιστάμενοι, [ότι] κβ χιλάδας Αράβων κατέσφαξαν."

- ^ Runciman, p. 52

- ^ s:Chronographia/Chapter 61

- ^ Georgius Monachus Continuants. Chronicon, Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinorum, Bonn, 1828—97

- ^ a b Paul Cubberley (1996) "The Slavic Alphabets". In Daniels and Bright, eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ^ Fine, John V.A. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. University of Michigan Press. pp. 144–148. ISBN 9780472081493.

- ^ Bojidar Dimitrov: Bulgaria Illustrated History. BORIANA Publishing House 2002, ISBN 9545000449

- ^ Reign of Simeon I, Encyclopaedia Britannica. Under Simeon’s successors Bulgaria was beset by internal dissension provoked by the spread of Bogomilism (a dualist religious sect) and by assaults from Magyars, Pechenegs, the Rus, and Byzantines.

- ^ Browning, Robert (1975). Byzantium and Bulgaria. London. pp. 194–5.

- ^ Leo Diaconus: Historia (full text in Russian) – Так в течение двух дней был завоеван и стал владением ромеев город Преслава.

- ^ Шишић [Sisic], p. 331

- ^ Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, full translation in Russian. Quote: В то время пока Владимир был юношей и правил на престоле своего отца, вышеупомянутый Самуил собрал большое войско и прибыл в далматинские окраины, в землю короля Владимира.

- ^ a b Ioannis Scylitzae: Synopsis Historiarum, Hans Thurn edition, Corpus Fontium Byzantiae Historiae, 1973; ISBN (978)3110022858. p. 457

- ^ Zlatarski, vol. II, pp. 1–41

- ^ Averil Cameron, The Byzantines, Blackwell Publishing (2006), p. 170

- ^ Jiriček, p.295

- ^ Jiriček, p. 382

- ^ Lord Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries, Morrow QuillPaperback Edition, 1979

- ^ R.J. Crampton, A Concise History of Bulgaria, 1997, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-567-19-X

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312217365.

- ^

Schurman, Jacob Gould (2005) [1916]. The Balkan Wars: 1912–1913 (2 ed.). Cosimo. p. 140. ISBN 9781596051768. Retrieved 20`0–03–17.

There is historic justice in the circumstance that the Turkish Empire in Europe met its doom at the hands of the Balkan nations themselves. For these nationalities had been completely submerged and even their national consciousness annihilated under centuries of Moslem intolerance, misgovernment, oppression, and cruelty. [...] none suffered worse than Bulgaria, which lay nearest to the capital of the Mohammedan conqueror.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^

"Bulgaria". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-17.

The Bulgarian nobility was destroyed – its members either perished, fled, or accepted Islam and Turkicization – and the peasantry was enserfed to Turkish masters.

- ^ Crampton, R.J. Bulgaria 1878–1918, p.2. East European Monographs, 1983. ISBN 0880330295.[need quotation to verify]

- ^ Jireček, K. J. (1876). Geschichte der Bulgaren (in German). Nachdr. d. Ausg. Prag 1876, Hildesheim, New York : Olms 1977. ISBN 3-487-06408-1.

- ^ "Timeline: Bulgaria – A chronology of key events". BBC News. 2010-05-06. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ^

Dillon, Emile Joseph (1920) [1920]. "XV". The Inside Story of the Peace Conference. New York: Harper. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

The territorial changes which the Prussia of the Balkans was condemned to undergo are neither very considerable nor unjust.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Балабанов, А. И аз на тоя свят. Спомени от разни времена. С., 1983, с. 72, 361

- ^ Mintchev, Vesselin (1999). "External Migration... in Bulgaria". South-East Europe Review (3/99): 124. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bulgaria in World War II : The Passive Alliance, Library of Congress

- ^ Bulgaria: Wartime Crisis, Library of Congress

- ^ Zhelyu Zhelev – The dissident president at the Sofia Echo, by Ivan Vatahov, Apr 17 2003 . Retrieved January 27, 2010.

- ^ William Marsteller. "The Economy". Bulgaria country study (Glenn E. Curtis, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (June 1992)

- ^ Domestic policy and its results, Library of Congress

- ^ The Political Atmosphere in the 1970s, Library of Congress

- ^

Bohlen, Celestine (1991-10-17). Bulgaria "Vote Gives Key Role to Ethnic Turks". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

... in 1980s [...] the Communist leader, Todor Zhivkov, began a campaign of cultural assimilation that forced ethnic Turks to adopt Slavic names, closed their mosques and prayer houses and suppressed any attempts at protest. One result was the mass exodus of more than 300,000 ethnic Turks to neighboring Turkey in 1989 ...

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Cracks show in Bulgaria's Muslim ethnic model. Reuters. May 31, 2009.

- ^ "1990 CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2010-02-07.

- ^ Разрушителният български преход, October 1, 2007, Le Monde Diplomatique (Bulgarian edition)

- ^

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division (2006). "Country Profile: Bulgaria" (PDF). Library of Congress. pp. 18, 23. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

Mass Media: In 2006 Bulgaria's print and broadcast media generally were considered unbiased, although the government dominated broadcasting through the state-owned Bulgarian National Television (BNT) and Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) and print news dissemination through the largest press agency, the Bulgarian Telegraph Agency. [...]Human Rights: In the early 2000s, Bulgaria generally has been rated highly on the issue of human rights. However, some exceptions exist. Although the media have a record of unbiased reporting, Bulgaria's lack of specific legislation protecting the media from state interference is a theoretical weakness.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ – Bulgaria country report for 2008, freedomhouse.org

- ^ Topography, Library of Congress.

- ^ "Мусала". Българска енциклопедия А-Я (in Bulgarian). БАН, Труд, Сирма. 2002. ISBN 9548104083. OCLC 163361648.

- ^ Donchev, D. (2004). Geography of Bulgaria (in Bulgarian). Sofia: ciela. p. 68. ISBN 9546497177.

- ^ Bulgarian NGO to Track 5 Imperial Eagles by Satellite, novinite.com, 9 July 2010

- ^ Climate, Library of Congress.

- ^ See List of oldest trees

- ^ See List of Kyoto Protocol signatories

- ^ Bulgaria Achieves Kyoto Protocol Targets – IWR Report, 11 August 2009

- ^ България от Космоса: сеч, пожари, бетон... и надежда, Petar Kanev, *8* Magazine, 2006.

- ^ High Air Pollution to Close Downtown Sofia, novinite.com, 14 January 2008

- ^ Bulgaria's Sofia, Plovdiv Suffer Worst Air Pollution in Europe, novinite.com, 23 June 2010

- ^ a b Bulgaria's quest to meet the environmental acquis, European Stability Initiative, 10 December 2008

- ^ Municipal waste recycling 1995 – 2008 (1000 tonnes), Eurostat

- ^ Първият завод за рециклиране на електроуреди вече работи, dnevnik.bg, 28 June 2010

- ^ Бъдещето на природните паркове в България и техните администрации, Gora Magazine, June 2010

- ^ Ще има ли България биосферни резервати?, Gora magazine, May 2007

- ^ "Bulgaria – Environmental Summary, UNData, United Nations". Data.un.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal, WWF, April 2004. An estimate for Bulgarian jackal population in the early ‘90s was put at up to 5000 individuals (Demeter & Spassov 1993). The jackal population in Bulgaria increased till 1994 and since then it seems to have been stabilized (Spassov pers. comm.).

- ^ Boyko Borisov, Prime Minister of Bulgaria, SETimes.com

- ^ The Bulgarian Legal System and Legal Research, Hauser Global Law School Program, August 2006.

- ^ Съдебната ни система – първенец по корупция, News.bg, 03.06.2009

- ^ Questions arise again about Bulgaria's legal system – Europe – International Herald Tribune, NYTimes, 5 November 2006

- ^ Interpol. "Interpol entry on Bulgaria". Interpol.int. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "State Agency for National Security Official Website". Dans.bg. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Официално: Близо 27 хиляди са полицаите в България, vsekiden.com, 19 January 2010

- ^ The Antarctic Treaty system: An introduction. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

- ^ Signatories to the Antarctic Treaty. Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

- ^ "NATO Update: Seven new members join NATO". 2004-03-29. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ "European Commission Enlargement Archives: Treaty of Accession of Bulgaria and Romania". 2005-04-25. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^

Bos, Stefan (1 January 2007). "Bulgaria, Romania Join European Union". VOA News. Voice of America. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ The List: The Six Most Important U.S. Military Bases, FP, May 2006

- ^ See Military of Bulgaria#Deployments

- ^ Arms Sales, Library of Congress]

- ^ Foreign Affairs in the 1960s and 1970s, Library of Congress

- ^ Армията все по-уверено се движи към численост 24 000, mediapool.bg, 26 May 2010

- ^ "Bulgaria – Military Personnel". Lcweb2.loc.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Bulgarian Armed Forces". Md.government.bg. 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Official Military Expenditures List

- ^

"World Bank: Data and Statistics: Country Groups". The World Bank Group. 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Bulgaria country profile - economic indicators". Eurostat. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ^ Fixed currency exchange rates, Bulgarian National Bank.

- ^ CIA, Bulgaria entry

- ^ Labour force rank list, CIA The World Factbook.

- ^

Miller, Catherine (2008-03-18). "Bulgaria's threat from corruption". BBC News Europe. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

Critics have suggested the recent spate of apparent misuse of European funds shows that Bulgaria is backsliding on reform, now that it has jumped the hurdles to win membership of the EU. [...] The European Union imposed a special corruption monitoring scheme on Bulgaria and neighboring Romania when they joined the EU in January 2007, because it was felt they were not yet up to EU levels. If Bulgaria does not meet specified benchmarks, the EU can impose what it calls safeguard clauses.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); line feed character in|quote=at position 391 (help) - ^ AES wind farm kicks off in Bulgaria, physorg.com, 6 October 2009

- ^ Economist: financial crisis brewed by U.S. market fundamentalism , Xinhua, March 12, 2009

- ^ Bulgaria and the IMF, Index

- ^ Energy Hub, 13.10.2008, Oxford Business Group.

- ^ За централата. "АЕЦ Козлодуй" ЕАД.

- ^ "EU Energy factsheet about Bulgaria" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Bulgaria Renewable Energy Fact Sheet (EU)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Bulgaria set for massive growth in wind power, European Wind Energy Association, 2010

- ^ Future of Bulgarian Mining Industry Looks Bright, novinite.com, 30 July 2010

- ^ See List of countries by copper mine production

- ^ See List of countries by zinc production

- ^ See List of countries by coal production.

- ^ See List of countries by bismuth production

- ^ "Geography of machine building in Bulgaria Factsheet". Geografia.kabinata.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Bulgaria – Economic Summary, UNData, United Nations". Data.un.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Bulgaria – Natural conditions, farming traditions and agricultural structures, Food and Agriculture Organization.

- ^ Еврокомисията наля 388 млн. лв. по сметките на фонд "Земеделие", dnes.bg, 05.02.2010

- ^ Bulgaria – Agriculture, nationsencyclopedia.com

- ^ "FAO – Tobacco production country rank". Fao.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "FAO – Raspberry production country rank". Fao.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Mag Studio – Contemporary and practical approach to design. "Statistics from the Bulgarian Tourism Agency". Tourism.government.bg. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Lonely Planet’s top 10 countries for 2011, Lonely Planet, October 31, 2010

- ^ Железниците почват да возят с автобуси, mediapool.bg, 11August 2008

- ^ БЪЛГАРСКАТА ЖП МРЕЖА СЕ МОДЕРНИЗИРА С 580 МЛН.ЕВРО ЕВРОПЕЙСКИ СРЕДСТВА, 24 April 2008.

- ^ "Влак-стрела ще минава през Ботевград до 2017 г". Botevgrad.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Железопътната линия Видин-София ще бъде модернизирана до 2017 г., investor.bg, 13.11.2008

- ^ Кабинетът одобри бюджета за 2008 г., Вести.бг

- ^ "Research and development expenditure". Eurostat.

- ^ Шопов, В. Влиянието на Европейското научно пространство върху проблема “Изтичане на мозъци” в балканските страни, сп. Наука, бр.1, 2007

- ^ Heinrich, M. and H.L. Teoh (2004) Galanthamine from snowdrop – the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer's disease from local Caucasian knowledge. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 92: 147 – 162. (doi:10.1016/j.jep.2004.02.012)

- ^ Scott LJ, Goa KL. Adis Review: Galantamine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs 2000;60(5):1095-122 PMID 11129124

- ^ Six-month space greenhouse experiments—a step to creation of future biological life support systems., US National Library of Medicine, 1998

- ^ Biomedical problems will need to be resolved to assure a safe human trip to Mars., 3 September 2000, space.com

- ^ See Timeline of space travel by nationality

- ^ IT Services: Rila Establishes Bulgarian Beachhead in UK, findarticles.com, June 24, 1999

- ^ www.OutourcingMonitor.EU (2006-08-06). "Bulgaria- Eastern Europe's Newest Hot Spot | Offshoring Business Intelligence & Tools | EU Out-Sourcing Specialists Platform | German Market-Entry offshoring Vendor Services". Outsourcingmonitor.eu. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ "BAS now operates a supercomputer (in Bulgarian)". Dnevnik.bg. 2010-04-29. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ IBM Supercomputer Boosts Bulgaria's Advance Towards Knowledge-Based Economy, IBM Press Room, 9 September 2008

- ^ National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- ^ The Ministry of Interior estimates various numbers (between 600,000 and 750,000) of Roma in Bulgaria; nearly half of Roma traditionally self-identify ethnically as Turkish or Bulgarian.

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook = Population Growth Rate Rankings". CIA. 2010-05-07.

- ^ "Will EU Entry Shrink Bulgaria's Population Even More? | Europe | Deutsche Welle | 26.12.2006". Dw-world.de. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Cultrual Policies and Trends in Europe. "Population by ethnic group and mother tongue, 2001". Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Kiminas, D. (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate. Wildside Press LLC. p. 15

- ^ Carvalho, Joaquim. (2007). Religion and power in Europe: conflict and convergence. Pisa University Press. p. 257.

- ^ "Bulgarian Orthodox Church". Kwintessential.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Religious beliefs in Bulgaria". Spainexchange.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^

Compare CIA. "[[CIA World Factbook|The world factbook]]: Field listing: Religions". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

Bulgarian Orthodox 82.6%, Muslim 12.2%, other Christian 1.2%, other 4% (2001 census)

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "The Bulgarian Constitution". Parliament.bg. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ a b "Country Profile: Bulgaria." Library of Congress Country Studies Program. October 2006. p6. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/profiles/Bulgaria.pdf

- ^ "OUTSOURCING TO BULGARIA – Danmarks ambassade Bulgarien". Ambsofia.um.dk. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Bulgaria country profile. Library of Congress Federal Research Division (October 2006). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Образование, здраве, пенсии и пътища – приоритетни в Бюджет 2010, econ.bg, 28 October 2009

- ^ България е сред страните в ЕС с най-висок коефициент на болници, econ.bg, 17 February 2010. Accessed 30 August 2010.

- ^ Life expectancy at birth rankings – CIA The World Factbook, 2010

- ^ "CIA – The World Factbook – Bulgaria". CIA. 2010-05-07.

- ^ Head Direction of Residential Registration and Administrative Service. Population table by permanent and present address as of 15 March 2008.

- ^ https://nsi.bg/bg/content/2981/%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%81%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%B5-%D0%BF%D0%BE-%D0%B3%D1%80%D0%B0%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5-%D0%B8-%D0%BF%D0%BE%D0%BB

- ^ Bulgaria's Gold Rush, National Geographic Magazine, December 2006.

- ^ Plovdiv: New ventures for Europe’s oldest inhabited city, The Courier, January/February 2010

- ^ The World's Oldest Cities, The Daily Telegraph

- ^ New perspectives on the Varna cemetery (Bulgaria), By: Higham, Tom; Chapman, John; Slavchev, Vladimir; Gaydarska, Bisserka; Honch, Noah; Yordanov, Yordan; Dimitrova, Branimira; September 1, 2007

- ^ "The Thracian tomb in Kazanluk". Digsys.bg. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Graba, A. La peinture religiouse en Bulgarie, Paris, 1928, p. 95

- ^ „Мисия Лондон” чупи рекорди, твори история Template:Bg icon, novinitepro.bg, 27 April 2010

- ^ Lorenz, Dagmar C. G. (17 April 2004). "Elias Canetti". Literary Encyclopedia. The Literary Dictionary Company Limited. ISSN 1747-678X. Retrieved 2009-10-13.

- ^ The Times: Spirit of Bourgas amongst Europe's top 20 summer festivals, The Sofia Echo, 2 April 2009

- ^

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division (2006). "Country Profile: Bulgaria" (PDF). Library of Congress. pp. 18, 23. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

Mass Media: In 2006 Bulgaria's print and broadcast media generally were considered unbiased, although the government dominated broadcasting through the state-owned Bulgarian National Television (BNT) and Bulgarian National Radio (BNR) and print news dissemination through the largest press agency, the Bulgarian Telegraph Agency. [...]Human Rights: In the early 2000s, Bulgaria generally has been rated highly on the issue of human rights. However, some exceptions exist. Although the media have a record of unbiased reporting, Bulgaria's lack of specific legislation protecting the media from state interference is a theoretical weakness.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Media Landscape – Bulgaria, European Journalism Centre

- ^ a b Footprint of Financial Crisis in the Media, Bulgaria Country Report, Open Society Institute, December 2009

- ^ "Bulgaria Internet Usage Stats and Market Report". Internetworldstats.com. 2010-06-30. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ "Руснаците купиха 81 милиона литра българско вино". Investor.bg. Retrieved 2010-04-15.

- ^ See List of wine-producing countries

- ^ "FIVB official rankings as per January 15, 2009". Fivb.org. 2009-01-15. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Volleyball: Bulgaria wins second place in women’s European League, focus-nes.bg, 25 July 2010

- ^ 2010 CEV European League – RESULTS, Confédération Européenne de Volleyball official website

- ^ Hristo Stoichkov – Bulgarian League Ambassador, Professional Football Against Hunger

- ^ Hristo Stoichkov: For sure Barcelona will win tonight, news.bg, 27.05.2009

- ^ "Rankings of A Group". Bgclubs.eu. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ^ Ingo Faulhaber. "Best club of 20th century ranking at the official site of the International Federation of Football History and Statistics". Iffhs.de. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

References

- Crampton, R. J. A Concise History of Bulgaria (2005) Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press ISBN 9780521616379

- Jiriček, Constantin Josef (2008). History of the Bulgarians (Geschichte der Bulgaren) (in German). Frankfurt: Textor Verlag GmbH, digital facsimile of the book published in Prague, 1878. pp. 587 pages. ISBN 3-938402-11-3.

- Runciman, Steven (1930). A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. G. Bell & Sons, London. ISBN 0404189164.

- Zlatarski, Vasil N. (1934). "Medieval History of the Bulgarian State (История на българската държава през средните векове, Част II, II изд.)" (in Bulgarian). Royal Printing House, Sofia. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- Шишић, Фердо (1928). Ljetopis popa Dukljanina. SKA.

Further reading

- Bell, John D., ed. (1998). Bulgaria in Transition: Politics, Economics, Society, and Culture after Communism. Westview. ISBN 978-0813390109

- Chary, Frederick B., The Bulgarian Jews and the Final Solution 1940–1944. University of Pittsburg Press (1972). ISBN 0-8229-3251-2

- Detrez, Raymond, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria (2006) Second Edition lxiv + 638 pp. Maps, bibliography, appendix, chronology ISBN 978-0-8108-4901-3

- Fox, Sir Frank, Bulgaria (1915) London: A. and C. Black, Ltd., book scanned by Project Gutenberg

- Ghodsee, Kristen (2009). Muslim Lives in Eastern Europe: Gender, Ethnicity and the Transformation of Islam in Postsocialist Bulgaria. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13955-5.

- Ghodsee, Kristen (2005). The Red Riviera: Gender, Tourism and Postsocialism on the Black Sea. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 0822336626.

- Hall, Richard C. Bulgaria's Road to the First World War (1996) New York: Columbia University Press ISBN 088033357X

- Hoppe, Hans-Joachim, Bulgarien - Hitlers eigenwilliger Verbündeter. Eine Fallstudie zur nationalsozialistischen Südosteuropapolitik (Bulgaria - Hitler’s Self-willing Ally. A Case study on National Socialist Policy Towards South East Europe), edited by Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Munich, dva, Stuttgart (1979), ISBN 3 421 01904 5

- Lampe, John R. The Bulgarian Economy in the Twentieth Century (1986) London: Croom Helm ISBN 0709916442

- MacDermott, Mercia (1962). A History of Bulgaria, 1393–1885. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Miller-Yianni, Simple Treasures in Bulgaria (2008) UK; Lulu Inc. ISBN 978-0-9559-8490-7

- Miller-Yianni, Bulgarian History - A Concise Account (2010) UK; Lulu Inc. ISBN 978-1-4457-1633-6

- Perry, Duncan M. Stefan Stambolov and the Emergence of Modern Bulgaria, 1870–1895 (1993) Durham: Duke University Press ISBN 0822313138

- Stepanov, Tsvetelin (2010). The Bulgars and the steppe empire in the early Middle Ages : the problem of the others. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450. Vol. 8. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004180017.

- Todorov, Tzvetan The fragility of goodness: why Bulgaria’s Jews survived the Holocaust: a collection of texts with commentary (2001) Princeton: Princeton University Press ISBN 0691088322

External links

- Government

- Official governmental site

- President of The Republic of Bulgaria

- National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- General information

- "Bulgaria". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Bulgaria information from the United States Department of State

- Portals to the World from the United States Library of Congress

- Bulgaria at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Template:Dmoz

- Travel

- Bulgaria

- European countries

- European Union member states

- Black Sea countries

- Member states of La Francophonie

- Liberal democracies

- Former monarchies

- Former empires

- Republics

- Slavic countries

- States and territories established in 681

- States and territories established in 1878

- States and territories established in 1908

- Member states of the Union for the Mediterranean

- Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization