Jaffa

Jaffa (Hebrew: יָפוֹ, romanized: Yāfō, pronounced [jaˈfo] ; Arabic: يَافَا, romanized: Yāfā, pronounced [ˈjaːfaː]), also called Japho, Joppa or Joppe in English, is an ancient Levantine port city which is part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, Israel, located in its southern part. The city sits atop a naturally elevated outcrop on the Mediterranean coastline.

Excavations at Jaffa indicate that the city was settled as early as the Early Bronze Age. The city is referenced in several ancient Egyptian and Assyrian documents. Biblically, Jaffa is noted as one of the boundaries of the tribe of Dan and as a port through which Lebanese cedars were imported for the construction of the Temple in Jerusalem. Under Persian rule, Jaffa was given to the Phoenicians. The city features in the biblical story of Jonah and the Greek legend of Andromeda. Later, the city served as the major port of Hasmonean Judea. However, its importance declined during the Roman period due to the construction of Caesarea.

Jaffa was contested during the Crusades, when it presided over the County of Jaffa and Ascalon. It is associated with the 1192 Battle of Jaffa and subsequent Treaty of Jaffa, a truce between Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, as well as a later 1229 peace treaty. In 1799, Napoleon also sacked the town in the Siege of Jaffa, and in the First World War the British took the city in the 1917 Battle of Jaffa, and under their watch, as part of Mandatory Palestine, ethnic tensions culminated in the 1921 Jaffa riots.

As an Arab majority city in the Ottoman era, Jaffa became known starting from the 19th century for its expansive orchards and fruits, including its namesake Jaffa orange. It was also a Palestinian hub for journalism in Mandatory Palestine in the 20th century, where Falastin and Al-Difa' newspapers were established. After the 1948 Palestine War, most of its Arab population fled or were expelled, and the city became part of then newly established state of Israel, and was unified into a single municipality with Tel Aviv in 1950. Today, Jaffa is one of Israel's mixed cities, with approximately 37% of the city being Arab.[1]

Etymology

The town was mentioned in Egyptian sources and the Amarna letters as Yapu. Mythology says that it is named for Yafet (Japheth), one of the sons of Noah, the one who built it after the Flood.[2][3] The Hellenist tradition links the name to Iopeia, or Cassiopeia, mother of Andromeda. An outcropping of rocks near the harbor is reputed to have been the place where Andromeda was rescued by Perseus. Pliny the Elder associated the name with Iopa, daughter of Aeolus, god of the wind. The medieval Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi referred to it as Yaffa.[4]

History

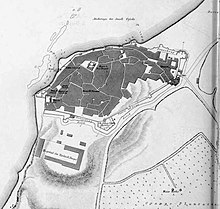

Ancient Jaffa was built on a 40 metres (130 ft) high kurkar sandstone ridge,[5] with a broad view of the coastline, giving it a strategic importance in military history.[6] The tell of Jaffa, created through the accumulation of debris and landfill over the centuries, made the hill even higher.

Bronze Age

The city as such was established at the latest around 1800 BCE.[7]

Jaffa is mentioned in an Ancient Egyptian letter from 1440 BCE. The so-called story of the Taking of Joppa glorifies its conquest by Pharaoh Thutmose III, whose general, Djehuty, hid Egyptian soldiers in sacks carried by pack animals and sent them camouflaged as tribute into the Canaanite city, where the soldiers emerged and conquered it. The story predates the story of the Trojan horse, as told by Homer, by at least two centuries.

The city is also mentioned in the Amarna letters under its Egyptian name Ya-Pho (Ya-Pu, EA 296, l.33). The city was under Egyptian rule until around 1200 BCE.[8]: 270–271

Iron Age

In the Hebrew Bible, Jaffa is depicted as the northernmost Philistine city, bordering the Israelite territories – more specifically those of Tribe of Dan (hence the modern term "Gush Dan" for the center of the coastal plain). The Israelites did not manage to take Jaffa from the Philistines.[9]

Jaffa is mentioned four times in the Hebrew Bible:[8]: 271 as the northernmost Philistine city by the coast, bordering the territory of the Tribe of Dan (Joshua 19:46); as port-of-entry for the cedars of Lebanon for Solomon's Temple (2 Chronicles 2:16); as the place whence the prophet Jonah embarked for Tarshish (Jonah 1:3); and again as port-of-entry for the cedars of Lebanon for the Second Temple of Jerusalem (Ezra 3:7).

In the late 8th century BCE, Sennacherib, king of Assyria, recorded conquering Jaffa from its sovereign, the Philistine king of Ashkelon.[9] After a period of Babylonian occupation, under Persian rule, Jaffa was governed by Phoenicians from Tyre.[citation needed]

Classical antiquity

Jaffa is not mentioned in Alexander the Great's coastal campaign, but during the Wars of the Diadochi, Antigonus Monophthalmus captured Jaffa in 315 BCE. Ptolemy I Soter later destroyed it in 312 BCE. Despite this, Jaffa was resettled and became a Ptolemaic mint site in the third century BCE. Archaeological evidence from this period includes a watchtower and numerous stamped amphora handles.[10] Additionally, the city is mentioned in several Zeno papyri.[10][11] The area was transferred to Seleucid control after the Battle of Paneas in 198 BCE.[10]

Around 163–162 BCE, during the Maccabean revolt, the inhabitants of Jaffa invited the local Jews onto boats, subsequently sinking them and drowning hundreds. In retaliation, Judas Maccabeus attacked Jaffa, setting the harbor on fire, destroying ships, and killing many inhabitants, though he did not attempt to hold the city. By 147–146 BCE, his brother Jonathan Apphus expelled the garrison of Seleucid king Demetrius II from Jaffa but did not conquer the city. In 143 BCE, Simon Thassi established a garrison in Jaffa, expelled the non-Jewish inhabitants to prevent them from collaborating with the Seleucid commander Tryphon, and fortified the city. During the operations of Antiochus VII Sidetes in Judaea, he demanded the surrender of Jaffa among other cities. Simon negotiated a settlement by agreeing to pay a smaller tribute.[10] Simon's capture of Jaffa is praised in 1 Maccabees because of the city's strategic importance as a port.[10]

In the Hasmonean period, the city was fortified and served as the main port of Judaea.[11][12] Under Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus (103–76 BCE), Jaffa was one of several coastal cities controlled by the Jews, including Straton's Tower, Apollonia, Iamnia, and Gaza.[10][13] Archaeological evidence from this period is limited but includes remnants of walls, tombs from the early first century BCE, and hoards of coins. Incidents of piracy before the Roman conquest are mentioned by Josephus, who accused Aristobulus of instigating raids and acts of piracy. These claims are echoed by Diodorus and Strabo, though their reliability is debated, given the term leistai (pirates) was often used pejoratively in this period.[10]

Jaffa was annexed to Syria by Pompey but later restored to Judaea by Julius Caesar, reaffirming Jewish access to the sea through their traditional port. In 39 BCE, Herod captured Jaffa from Antigonus, though control fluctuated until Octavian returned it to Herod after the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra. After Herod's death, Jaffa, along with Strato's Tower (Caesarea), Sebaste, and Jerusalem, was assigned to Archelaus' ethnarchy in Judaea.[10] The construction of Herod's superior harbor at Caesarea diminished Jaffa's regional importance.[10][11][12]

Josephus's accounts indicate that Jaffa had city status, administering surrounding districts, reflecting continued regional significance.[10] However, he adds that the harbor at Jaffa was inferior to that of Caesarea.[14] The population of the city during this period was predominantly Jewish.[10] Strabo, writing in the early 1st century CE, describes Jaffa as a location from which it is possible to see Jerusalem, the capital of the Jews, and writes that the Jews used it as their naval arsenal when they descended to the sea.[15] Excavations suggest urban expansion during the Hellenistic period under Ptolemaic rule, followed by contraction under Seleucid and early Roman rule, and renewed expansion later in the Roman and Byzantine periods.[10] Archaeological remains from the Roman period are mainly found near the harbor, including rich finds like terra sigillata, a bread or cheese stamp, and coins.[10]

In the early stages of the First Jewish–Roman War in 66 CE, Cestius Gallus sent forces to Jaffa, where the city was destroyed and its inhabitants indiscriminately killed. Josephus writes that 8,400 inhabitants were massacred.[16][17] Subsequently, the city was resettled by Jews expelled from neighboring regions,[10] who used it to disrupt maritime commerce between Egypt and Syria. As the Romans, led by Vespasian, approached Jaffa, those Jews fled to sea but were devastated by a storm, killing 4,200 people. Those who reached shore were killed by the Romans, who subsequently destroyed Jaffa again and stationed troops to prevent its reuse as a pirate base.[16] In the 3rd century CE, Jaffa was known by the name Flavia Ioppe, potentially indicating an honorary designation under Flavian rule.[10]

Late antiquity

Despite the devastation and loss of life during the revolt, Jaffa maintained a Jewish population.[10] Inscriptions from the early 2nd century indicate Jewish involvement in local governance. Further evidence includes Jewish epitaphs dating from the 3rd to 6th centuries, some from members of the diaspora,[18] along with references in Talmudic sources to scholars associated with Jaffa.[10] Archaeological findings from the 2nd and 3rd centuries reveal structures destroyed by fire, possibly linked to regional unrest.[10]

During the first centuries of Christianity, Jaffa was a fairly unimportant Roman and Byzantine locality, which only in the 5th century became a bishopric.[19] The new religion arrived in Jaffa relatively late, not appearing in historical records until the Council of Ephesus in 431 CE.[10] A very small number of its Greek or Latin bishops are known.[20][21] Early Christian texts describe Jaffa as a modest settlement, with varying accounts of its prosperity and state of preservation.[10]

- Religious narratives

This section uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (January 2024) |

The New Testament account of Saint Peter bringing back to life the widow Dorcas (recorded in Acts of the Apostles, 9:36–42, takes place in Jaffa, then called in Greek Ἰόππη (Latinized as Joppa). Acts 10:10–23 relates that, while Peter was in Jaffa, he had a vision of a large sheet filled with "clean" and "unclean" animals being lowered from heaven, together with a message from the Holy Spirit telling him to accompany several messengers to Cornelius in Caesarea Maritima. Peter retells the story of his vision in Acts 11:4–17, explaining how he had come to preach Christianity to the gentiles.[22]

In Midrash Tanna'im in its chapter Deuteronomy 33:19, reference is made to Jose ben Halafta (2nd century) traveling through Jaffa. Jaffa seems to have attracted serious Jewish scholars in the 4th and 5th century. The Jerusalem Talmud (compiled 4th and 5th century) in Moed Ketan references Rabi Akha bar Khanina of Jaffa; and in Pesachim chapter 1 refers to Rabi Pinchas ben Yair of Jaffa. The Babylonian Talmud (compiled 5th century) in Megillah 16b mentions Rav Adda Demin of Jaffa. Leviticus Rabbah (compiled between 5th and 7th century) mentions Rav Nachman of Jaffa. The Pesikta Rabbati (written in the 9th century) in chapter 17 mentions R. Tanchum of Jaffa.[23] Several streets and alleys of the Jaffa Flea Market area are named after these scholars.

Middle Ages

Early Islamic period

In 636 Jaffa was conquered by Arabs. Under Islamic rule, it served as a port of Ramla, then the provincial capital.

Al-Muqaddasi (c. 945/946 – 991) described Yafah as "lying on the sea, is but a small town, although the emporium of Palestine and the port of Ar-Ramlah. It is protected by a strong wall with iron gates, and the sea-gates also are of iron. The mosque is pleasant to the eye, and overlooks the sea. The harbour is excellent".[4]

Crusader/Ayyubid period

Jaffa was captured in June 1099 during the First Crusade, and was the centre of the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, one of the vassals of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. One of its counts, John of Ibelin, wrote the principal book of the Assizes of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.[citation needed]

Saladin conquered Jaffa in 1187. The city surrendered to King Richard the Lionheart on 10 September 1191, three days after the Battle of Arsuf. Despite efforts by Saladin to reoccupy the city in the July 1192 Battle of Jaffa, the city remained in the hands of the Crusaders. On 2 September 1192, the Treaty of Jaffa was formally signed, guaranteeing a three-year truce between the two armies.

In 1229, Frederick II signed a ten-year truce in a new Treaty of Jaffa. He fortified the castle of Jaffa and had two inscriptions carved into city wall, one Latin and the other Arabic. The inscription, deciphered in 2011, describes him as the "Holy Roman Emperor" and bears the date "1229 of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus the Messiah."[24]

Mamluk period

In March 1268, Baibars, the sultan of the Egyptian Mamluks, conquered Jaffa simultaneously with conquering Antioch.[25][26] Baibars's goal was to conquer Christian crusader strongholds.[26] An inscription from the White Mosque of Ramla, today visible in the Great Mosque of Gaza,[27] commemorates the event:

In the name of God the Merciful, the Compassionate,...gave power to his servant...who has trust in him...who fights for Him and defends the faith of His Prophet...Sultan of Islam and the Muslims, Baybars...who came out with his victorious army on the 10th of the month of Rajab from the land of Egypt, resolved to carry out jihad and combat the intransigent infidels. He camped in the port city of Jaffa in the morning and conquered it, by God's will, in the third hour of that day. Then he ordered the erection of the dome over the blessed minaret, as well as the gate of this mosque...in the year 666 of the Hijra [1268 CE]. May God have mercy upon him and upon all Muslims.[27][28]

Abu'l-Fida (1273–1331), writing in 1321, described "Yafa, in Filastin" as "a small but very pleasant town lying on the sea-shore. It has a celebrated harbour. The town of Yafa is well fortified. Its markets are much frequented, and many merchants ply their trades here. There is a large harbour frequented by all the ships coming to Filastin, and from it they set sail to all lands. Between it and Ar Ramlah the distance is 6 miles, and it lies west of Ar Ramlah."[4]

In 1432, Bertrandon de la Broquière observed that Jaffa was in ruins, with only a few tents standing. He wrote: "At Jaffa, the pardons commence for pilgrims to the Holy Land ... at present, it is entirely destroyed, having only a few tents covered with reeds, where pilgrims seek shelter from the heat of the sun. The sea enters the town, forming a poor and shallow harbor: it is dangerous to remain there long for fear of being driven onshore by a gust of wind. When any pilgrims disembark there, interpreters and other officers of the sultan instantly hasten to ascertain their numbers, to serve them as guides, and to receive, in the name of their master, the customary tribute."[29]

Ottoman period

16th-18th centuries

In 1515, Jaffa was conquered by the Ottoman sultan Selim I.[30]

In the census of 1596, it appeared located in the nahiya of Ramla in the liwa of Gaza. It had a population of 15 households, all Muslim. They paid a fixed tax rate of 33,3 % on various products; a total of 7,520 akçe.[30]

The traveller Jean Cotwyk (Cotovicus) described Jaffa as a heap of ruins when he visited in 1598.[31][32] Botanist and traveller Leonhard Rauwolf landed near the site of the town on 13 September 1575 and wrote "we landed on the high, rocky shore where the town of Joppe did stand formerly, at this time the town was so demolished that there was not one house to be found." (p. 212, Rauwolf, 1582)

The 17th century saw the beginning of the re-establishment of churches and hostels for Christian pilgrims en route to Jerusalem and the Galilee. During the 18th century, the coastline around Jaffa was often besieged by pirates and this led to the inhabitants relocating to Ramla and Lod, where they relied on messages from a solitary guard house to inform them when ships were approaching the harbour. The landing of goods and passengers was notoriously difficult and dangerous. Until well into the 20th century, ships had to rely on teams of oarsmen to bring their cargo ashore.[33]

Napoleon (1799)

On 7 March 1799, Napoleon captured the town in what became known as the Siege of Jaffa, breached its walls, ransacked it, and killed scores of local inhabitants as a reaction to his envoys being brutally killed when delivering an ultimatum of surrender. Napoleon ordered the massacre of thousands of Muslim soldiers who were imprisoned having surrendered to the French.[34] Napoleon's deputy commissioner of war Jacques-François Miot described it thus:

On 10 March 1799 in the afternoon, the prisoners of Jaffa were marched off in the midst of a vast square phalanx formed by the troops of General Bon... The Turks, walking along in total disorder, had already guessed their fate and appeared not even to shed any tears... When they finally arrived in the sand dunes to the south-west of Jaffa, they were ordered to halt beside a pool of yellowish water. The officer commanding the troops then divided the mass of prisoners into small groups, who were led off to several different points and shot... Finally, of all the prisoners there only remained those who were beside the pool of water. Our soldiers had used up their cartridges, so there was nothing to be done but to dispatch them with bayonets and knives. ... The result ... was a terrible pyramid of dead and dying bodies dripping blood and the bodies of those already dead had to be pulled away so as to finish off those unfortunate beings who, concealed under this awful and terrible wall of bodies, had not yet been struck down.[34]

Many more died in an epidemic of bubonic plague that broke out soon afterwards.[35]

19th century

Residential life in the city was reestablished in the early 19th century.[citation needed] The governor who was appointed after the devastation brought about by Napoleon, Muhammad Abu-Nabbut, commenced wide-ranging building and restoration work in Jaffa, including the Mahmoudiya Mosque and the public fountain known as Sabil Abu Nabbut. During the 1834 Peasants' revolt in Palestine, Jaffa was besieged for forty days by "mountaineers" in revolt against Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt.[36]

In 1820, Isaiah Ajiman of Istanbul built a synagogue and hostel for the accommodation of Jews on their way to their four holy cities - Jerusalem, Hebron, Tiberias and Safed. This area became known as Dar al-Yehud (Arabic for "the house of the Jews"); and was the basis of the Jewish community in Jaffa. The appointment of Mahmud Aja as Ottoman governor marked the beginning of a period of stability and growth for the city, interrupted by the 1832 conquest of the city by Muhammad Ali of Egypt.[citation needed]

By 1839, at least 153 Sephardic Jews were living in Jaffa.[37] The community was served for fifty years by Rabbi Yehuda HaLevi miRagusa. In the early 1850s, HaLevi leased an orchard to Clorinda S. Minor, founder of a Christian messianic community that established Mount Hope, a farming initiative to encourage local Jews to learn manual trades, which the Messianics did in order to pave wave for the Second Coming of Jesus. In 1855, the British Jewish philanthropist Moses Montefiore bought the orchard from HaLevi, although Minor continued to manage it.[38]

American missionary Ellen Clare Miller, visiting Jaffa in 1867, reported that the town had a population of "about 5000, 1000 of these being Christians, 800 Jews and the rest Moslems".[39][40]

The city walls were torn down during the 1870s, allowing the city to expand.[41]

1900–1914

By the beginning of the 20th century, the population of Jaffa had swelled considerably. A group of Jews left Jaffa for the sand dunes to the north, where in 1909 they held a lottery to divide the lots acquired earlier. The settlement was known at first as Ahuzat Bayit, but an assembly of its residents changed its name to Tel Aviv in 1910. Other Jewish suburbs to Jaffa had already been founded since 1887, with others following until the Great War.[citation needed]

In 1904, rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook (1864–1935) moved to Ottoman Palestine and took up the position of Chief Rabbi of Jaffa.[42]

Late Ottoman-period economy

In the 19th century, Jaffa was best known for its soap industry. Modern industry emerged in the late 1880s.[43] The most successful enterprises were metalworking factories, among them the machine shop run by the Templers that employed over 100 workers in 1910.[43] Other factories produced orange-crates, barrels, corks, noodles, ice, seltzer, candy, soap, olive oil, leather, alkali, wine, cosmetics and ink.[43] Most of the newspapers and books printed in Ottoman Palestine were published in Jaffa.

In 1859, a Jewish visitor, L.A. Frankl, found sixty-five Jewish families living in Jaffa, 'about 400 soul in all.' Of these four were shoemakers, three tailors, one silversmith and one watchmaker. There were also merchants and shopkeepers and 'many live by manual labour, porters, sailors, messengers, etc.'[44]

Late Ottoman agriculture; Jaffa oranges

Until the mid-19th century, Jaffa's orange groves were mainly owned by Arabs, who employed traditional methods of farming. The pioneers of modern agriculture in Jaffa were American settlers, who brought in farm machinery in the 1850s and 1860s, followed by the Templers and the Jews.[45] From the 1880s, real estate became an important branch of the economy. A 'biarah' (a watered garden) cost 100,000 piastres and annually produced 15,000, of which the farming costs were 5,000: 'A very fair percentage return on the investment.' Water for the gardens was easily accessible with wells between ten and forty feet deep.[46][47]

Jaffa's citrus industry began to flourish in the last quarter of the 19th century. E.C. Miller records that 'about ten million' oranges were being exported annually, and that the town was surrounded by 'three or four hundred orange gardens, each containing upwards of one thousand trees'.[48] Shamuti or Shamouti oranges, aka "Jaffa oranges", were the major crop, but citrons, lemons and mandarin oranges were also grown.[49] Jaffa had a reputation for producing the best pomegranates.[50]

Developed the mid-19th century, the Jaffa orange was first produced for export in the city after being developed by Arab farmers.[51][52] The orange was the primary citrus export for the city. Today,[dubious – discuss] along with the navel and bitter orange, it is one of three main varieties of the fruit grown in the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and Southern Europe.[52][53]

The Jaffa orange emerged as a mutation on a tree of the 'Baladi' variety of sweet orange (C. sinensis) near the city of Jaffa.[51][52] After the Crimean War (1853–56), the most important innovation in local agriculture was the rapid expansion of citrus cultivation.[54] Foremost among the varieties cultivated was the Jaffa (Shamouti) orange, and mention of it being exported to Europe first appears in British consular reports in the 1850s.[51][54] One factor cited in the growth of the export market was the development of steamships in the first half of the 19th century, which enabled the export of oranges to the European markets in days rather than weeks.[55] Another reason cited for the growth of the industry was the relative lack of European control over the cultivation of oranges compared to cotton, formerly a primary commodity crop of Palestine, but outpaced by the Jaffa orange.[56]

The prosperity of the orange industry brought increased European interest and involvement in the development of Jaffa. In 1902, a study of the growth of the orange industry by Zionist officials outlined the different Palestinian owners and their primary export markets as England, Turkey, Egypt and Austria-Hungary. While the traditional Arabic cultivation methods were considered "primitive," an in-depth study of the financial expenditure involved reveals that they were ultimately more cost-efficient than the Zionist-European enterprises that followed them some two decades later.[57]

First World War

In 1917, the Tel Aviv and Jaffa deportation resulted in the Ottomans expelling the entire civilian population. While Muslim evacuees were allowed to return before long, the Jewish evacuees remained in camps (and some in Egypt) until after the British conquest.[58]

During the course of their campaign through Ottoman Palestine and the Sinai (1915–1918) against the Ottomans, the British took Jaffa in November 1917, although it remained under observation and fire from the Ottomans. The battle of Jaffa in late December 1917 pushed back the Ottoman forces securing Jaffa and the line of communication between it and Jerusalem, which had already been taken on 11 December.

British Mandate

-

Jaffa 1929 1:20,000

-

Jaffa 1943 1:20,000

-

Jaffa 1945 1:250,000

1920s: conflict and development

According to the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Jaffa had a population of 47,799, consisting of 20,699 Muslims, 20,152 Jews and 6,850 Christians,[59] increasing to 51,866 in the 1931 census, residing in 11,304 houses.[60]

During the British Mandate, tension between the Jewish and Arab population increased. A wave of Arab attacks during 1920 and 1921 caused many Jewish residents to flee and resettle in Tel Aviv, initially a marginal Jewish neighborhood north of Jaffa. The Jaffa riots in 1921, (known in Hebrew as Meoraot Tarpa) began with a May Day parade that turned violent. Arab rioters attacked Jewish residents and buildings killing 47 Jews and wounding 146.[61] The Hebrew author Yosef Haim Brenner was killed in the riots.[62] At the end of 1922, Tel Aviv had 15,000 residents: by 1927, the population had risen to 38,000.

Still, during most of the 1920s Jaffa and Tel Aviv maintained peaceful co-existence. Most Jewish businesses were located in Jaffa, some Jewish neighbourhoods paid taxes to the municipality of Jaffa, many young Jews who could not afford the housing costs of Tel Aviv resided there, and the big neighbourhood of Menashiya was by and large fully mixed. The first electric company in the British Mandate of Palestine, although owned by Jewish shareholders, had been named the Jaffa Electric Company. In 1923, both Jaffa and Tel Aviv had begun a rapid process of wired electrification through a joint grid.[63]

1930s: Arab revolt (1936–39)

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine severely impacted Jaffa. On 19 April 1936, riots broke out in Jaffa after rumors spread among the local Arab community that Jews had started to kill Arabs; Arab rioters attacked Jewish targets for three days before British security forces quelled the rioting. 9 Jews and 2 Arabs were killed and dozens more were wounded.[64] In response to the riots, Arab leadership in Palestine declared a general strike, which began in the Jaffa Port and quickly spread to the rest of the region.[65] After the start of the general strike, British troops stationed in Palestine were bolstered by reinforcements from Malta and Egypt to subdue rioting which had broken out in several major Palestinian cities. Arab rioters in Jaffa used the Old City, which contained a maze of homes, winding alleyways and an underground sewer system, to escape arrest by British security forces.[65]

Beginning in May 1936, in response to further Arab unrest in Jaffa, the British authorities suspended municipal services in the city, establishing barricades around the Old City and covering access roads with glass shards and nails.[65] On June of that year, Royal Air Force bombers dropped boxes of leaflets in Arabic on Jaffa, requesting the city's inhabitants to evacuate that same day.[65] In June 15, the Royal Engineers used gelignite charges to demolish between 220 and 240 Arab-owned homes in the Old City, leaving an open strip which cut through the center of Jaffa from end to end and displacing approximately 6,000 Arabs.[66] On the evening of 17 June, 1,500 British troops entered Jaffa and a Royal Navy warship moved near the Jaffa Port to seal off escape routes by sea. On 29 June, British forces carried out another round of house demolitions, carving a swath from north to south.[65]

The British authorities claimed that house demolitions in Jaffa were part of a "facelift" given to the Old City.[65] Local Arab newspapers resorted to using sarcasm to describe the demolitions, writing that the British had "beautified" Jaffa using boxes of gelignite.[66] Sir Michael McDonnell, then serving as the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Palestine, found in favor of Arab petitions from Jaffa and, upholding existing laws regarding house demolitions, ruled against the demolitions carried out by British forces in the Old City. In response, the Colonial Office dismissed him from his post.[67] The report produced by the Peel Commission in 1937 recommended that Jaffa, together with Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Lydda and Ramle, remain under permanent British control, forming a "corridor" from the sea port to the Holy Places, accessible to Arabs and Jews alike; whereas the rest of Mandatory Palestine was to be split between an Arab state and a Jewish state.[68]

1940-47: WWII; frictions

Village Statistics of 1945 listed Jaffa with a population of 94,310, of whom 50,880 were Muslims, 28,000 were Jews, 15,400 were Christians and 30 were classified as "other".[69] The Christians were mostly Greek Orthodox and about one-sixth of them were members of the Eastern Catholic Churches. One of the most prominent members of the Arab Christian community was the Greek Orthodox Issa El-Issa, publisher of the newspaper Falastin.

In 1945, the Jewish community of Jaffa complained to the city mayor Yousef Haikal that their neighbourhoods don't receive appropriate municipal services (street lighting and paving, garbage removal, sewerage etc.) even though they contribute 40% of the municipality's budget. Some of the services (education, healthcare, and social services) had already been provided by Tel Aviv Municipality at its own expense, which formed the base for the Jewish community's demand that the Mandatory government annex their neighbourhoods to Tel Aviv.[70] In the year of 1946, Tel Aviv Municipality spent £P 300K on services for the Jewish neighbourhoods of Jaffa,[71] an increase from £P 80K in the year of 1942.[72]

1947-48: partition plan and armed conflict

In 1947, the UN Special Commission on Palestine recommended that Jaffa be included in the planned Jewish state. Due to the large Arab majority, however, it was instead designated as an enclave of the Arab state in the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. The enclave would have excluded the northern Jewish-populated parts of the city, but included the agricultural lands to the south and east of the city, extending to the then-boundaries of Mikveh Israel, Holon and Bat Yam.[73] The resolution was rejected by Palestinian Arab leadership and by the Arab League.[74][75]

Following the inter-communal violence which broke out following the passing of the UN partition resolution, the mayors of Jaffa and Tel Aviv tried to calm their communities.[76] One of the main concerns for the people of Jaffa was the protection of the citrus fruit export trade which had still not reached its pre-Second World War highs.[77] Eventually the bilateral orange-picking and exporting of both sides continued although without a formal agreement.[78]

At the beginning of 1948 Jaffa's defenders consisted of one company of around 400 men organised by the Muslim Brotherhood, almost none of them Palestinian Arabs (the "Arab Brigade"), and the local Arab irregulars of the National Guard.[79] As in Haifa, the irregulars intimidated the local population.[78]

On 4 January 1948, the Lehi detonated a truck bomb outside the Saraya, formerly the Ottoman administrative building and now housing the Arab National Committee. The building and some nearby buildings were destroyed. Most of the 26 dead and many wounded were not connected to the National Committee but were passersby and staff at a food distribution programme for poor children that was also in the same building. Most of the children were not present as it was Sunday.[80]

In February Jaffa's Mayor, Yousef Haikal, contacted David Ben-Gurion through a British intermediary trying to secure a peace agreement with Tel Aviv, but the commander of the Arab militia in Jaffa opposed it.[78][81] The frontline saw a period of mostly static warfare, with sporadic sniper fire, machine gun bursts, and limited skirmishes. While the introduction of medium mortars in early March 1948 escalated the intensity of the fighting, tactics remained largely unchanged.

On 25 April 1948, the Irgun launched an offensive on Jaffa. This began with a mortar bombardment which went on for three days during which twenty tons of high explosive were fired into the town.[82][83] On 27 April the British Government, fearing a repetition of the mass exodus from Haifa the week before, ordered the British Army to confront the Irgun and their offensive ended. Simultaneously the Haganah had launched Operation Hametz, which overran the villages east of Jaffa and cut the town off from the interior.[84] On 29 April, the Irgun commander for the Tel-Aviv & Jaffa district, Eliyahu Tamler, was killed by a British shell.[85]

The fall of Haifa a few days earlier, and fear of another massacre similar to Irgun's Deir Yassin massacre, caused panic across the Arabs of Jaffa, leading most of them to flee.[86] The population of Jaffa on the eve of the attack was between 50,000 and 60,000, with some 20,000 people having already left the town.[82] By 30 April, there were 15,000–25,000 remaining.[84][87] In the following days a further 10,000–20,000 people fled by sea. When the Haganah took control of the town on 14 May around 4,000 people were left.[88] The town and harbour's warehouses were extensively looted.[89][90] The displacement of Jaffa's Arab population was part of the larger 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight.

The city surrendered to the Haganah on 14 May 1948 and shortly after the British police and army left the city.[91] The 3,800 Arabs who remained in Jaffa after the exodus were concentrated in the Ajami district and subject to strict martial law.[92] The military administration in Jaffa lasted until 1 June 1949, at which point, Tel Aviv Municipality took over the administration; Jaffa Municipality, de-jure still in existence at the time, had not exercised any authority since 1948 until its dissolution in 1950.[93]

State of Israel

Gradual annexation into Tel Aviv

The boundaries of Tel Aviv and Jaffa became a matter of contention between the Tel Aviv municipality and the Israeli government during 1948.[94] The former wished to incorporate only the well-off Jewish suburbs in the north of Jaffa, while the latter wanted a more complete unification.[94] The issue also had international sensitivity, since the main part of Jaffa was in the Arab portion of the United Nations Partition Plan, whereas Tel Aviv was not, and no armistice agreements had yet been signed.[94] An alternative proposal, merging Bat Yam and Holon into Jaffa to form a bigger city south of Tel Aviv, was rejected on financial grounds, as the two small Jewish settlements lacked the funds necessary to sustain Jaffa.[93]

On 10 December 1948, the government announced the annexation to Tel Aviv of Jaffa's Jewish suburbs of Maccabi (American–German Colony), Volovelsky (northwestern Florentin), Giv'at Herzl, and Shapira; territories outside Jaffa's municipal boundary, specifically the Arab neighbourhood of Abu Kabir, the Arab village of Salama and some of its agricultural land, and the working class Jewish areas of Hatikva and Ezra, were annexed to Tel Aviv at the same time, thus introducing around 50,000 new residents into the city.[93][94] On 18 May 1949, the new boundary was drawn along Shari' Es Salahi (now Olei Zion Street) and Shari' El Quds (now Ben-Zvi Road), thereby adding into Tel Aviv the former Arab neighbourhood of Manshiya and part of Jaffa city centre, for the first time including land that had been in the Arab portion of the UN partition plan.[94]

The government decided on a permanent unification of Tel Aviv and Jaffa on 4 October 1949, but the actual unification was delayed until 16 June 1950 due to concerted opposition from Tel Aviv's mayor Israel Rokach, who had demanded government funding of 1M I£ towards the expenses of providing municipal services to Jaffa.[95][96][94] Jaffa was expected to consume 18% of the unified municipality's budget, while contributing only 4% of its income.[93] The two sides came to an agreement under which the government covered 100K I£ of the unified municipality's expenses, as well as funded healthcare, education, and social services for Jaffa residents directly from the state budget.[93] The name of the unified city was Tel Aviv until 19 August 1950, when it was renamed as Tel Aviv–Yafo in order to preserve the historical name Jaffa.[94] The population of Jaffa prior to the unification was estimated as 40,000, out of them 5,000 Arabs,[97] and most of the others new olim.[93]

The land which had formerly belonged to Jaffa municipality, and was annexed into Tel Aviv, includes the neighbourhoods of Manshiya, Florentin, Giv'at Herzl, and Shapira; and such landmarks as Charles Clore Park, Hassan Bek Mosque, Carmel Market, the former Jaffa railway station, and the new Tel Aviv central bus station. On the other hand, Jaffa boundaries were expanded to the southeast, incorporating Gaon Stadium and the new neighbourhoods of Neve Ofer, Jaffa Gimel and Jaffa Dalet.[98] Other former Arab villages incorporated into Tel Aviv–Jaffa include Al-Mas'udiyya, annexed on 20 December 1942,[99] in the New North; Jarisha, annexed on 25 November 1943,[100] on the southern bank of Yarkon River; Al-Jammasin al-Gharbi, annexed on 31 March 1948,[101] and since 1957 redeveloped into Bavli neighbourhood; and Al-Shaykh Muwannis, annexed on 25 February 1949,[94] and since 1955 redeveloped into Tel Aviv University main campus.

- Streets renamed

After the Jewish takeover, all pre-existing street names in Jaffa were abolished, and replaced with numeric identifiers. By 1954, only the four main streets had proper names: Jerusalem (former Djemal Pasha; then King George V; then No.1) Avenue; Tarshish (former Bustrus; then No.2; now David Raziel) Street; Eilat Street (former No.298); and Shalma Road (former No.310).[102][103]

The road passing between Florentin and Neve Tzedek neighbourhoods was until 1948 named Tel Aviv Road, being the main thoroughfare between the two city centres. After the annexation of Florentin into Tel Aviv, it became an internal road in Tel Aviv, so its name no longer made sense. Thus the section lying within the new Tel Aviv boundaries was renamed into Jaffa Road; and the section which became the new Tel Aviv–Jaffa boundary, into Eilat Street.

Salama Road, a main eastwards road from Jaffa towards the depopulated village of Salama, was renamed Shalma Road after the reconstructed Hebrew name of Capharsalama (Greek: Χαφαρσαλαμα) which is mentioned in 1 Maccabees 7:31 as the location of the battle of Caphar-salama. However, both names remain in use.[104]

Arabic street names were eventually replaced with Hebrew ones, e.g. Al-Kutub Street was renamed Resh Galuta Street, Abu Ubeyda Street was renamed She’erit Yisra’el Street, and Al-Salahi Street was renamed Olei Zion Street.[105] This practice has been criticized by residents of affected Arabic neighborhoods, who deem the names inappropriate (for example, a street named after Rabbi Simcha Bunim of Peshischa was called a "local laughingstock" by Tel Aviv-Jaffa city councillor Ahmed Belha;[106] and a street where the Al Siksik Mosque is located was renamed Beit Eshel Street, after a short-lived Jewish settlement in what is now Beersheba[107]) and demand a return to Arabic names.

Urban development

From the 1990s onwards, efforts have been made to restore Arab and Islamic landmarks, such as the Mosque of the Sea and Hassan Bek Mosque, and document the history of Jaffa's Arab population. Parts of the Old City have been renovated, turning Jaffa into a tourist attraction featuring old restored buildings, art galleries, theaters, souvenir shops, restaurants, sidewalk cafes and promenades.[108][109] Many artists have moved their studios from Tel Aviv to the Old City and its surroundings, such as the Jaffa port,[110] the American–Germany Colony and the flea market.[111] Beyond the Old City and tourist sites, many neighborhoods of Jaffa are poor and underdeveloped. However, real-estate prices have risen sharply due to gentrification projects in Ajami, Noga, and Lev Yafo.[112][113][114] The municipality of Tel Aviv–Yafo is currently working to beautify and modernize the port area.[115]

Demography

Modern Jaffa has a heterogeneous population of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. As of 2021, Jaffa has 52,470 residents, about a third of which are Arabs.[116][117]

Landmarks

Sights and museums

The Clock Square with its distinctive clocktower was built in 1906 in honor of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The Saraya (governor's palace) was built in the 1890s.[118][failed verification] Andromeda rock is the rock to which beautiful Andromeda was chained in Greek mythology.[119] The Zodiac alleys are a maze of restored alleys leading to the harbor. Jaffa Hill is a center for archaeological finds, including restored Egyptian gates, about 3,500 years old. Jaffa Lighthouse is an inactive lighthouse located in the old port.

The Jaffa Museum of Antiquities is located in an 18th-century Ottoman building constructed on the remains of a Crusader fortress. In 1811, Abu Nabout turned it into his seat of government. In the late 19th century, the governmental moved to the "New Saraya," and the building was sold to a wealthy Greek-Orthodox family who established a soap factory there. Since 1961, it has housed an archaeological museum,[120] which is currently closed to the general public.[121]

The Libyan Synagogue (Beit Zunana) was a synagogue built by a Jewish landlord, Zunana, in the 18th century. It was turned into a hotel and then a soap factory, and reopened as a synagogue for Libyan Jewish immigrants after 1948. In 1995, it became a museum.

Other museums and galleries in the area include the Farkash Gallery collection.

Churches and monasteries

The Greek Orthodox Monastery of Archangel Michael (Patriarchate of Jerusalem) near Jaffa Port also has Romanian and Russian communities in its compound. Built in 1894, the Church of St. Peter and St. Tabitha serves the Russian Orthodox Christian community, with services in Russian and Hebrew; underneath the chapel nearby there is what is believed to be the tomb of St Tabitha.[122] St. Peter's Church is a Franciscan Roman-Catholic basilica and hospice built in 1654 on the remains of a Crusader fortress, and commemorates St Peter, as he brought the disciple Tabitha back from the dead; Napoleon is believed to have stayed there.

Immanuel Church, built 1904, serves today a Lutheran congregation with services in English and Hebrew.

The Saint Nicholas Armenian Monastery was built in the 17th century.[123]

Mosques

Al-Bahr Mosque, lit. the Sea Mosque, overlooking the harbour, is depicted in a painting from 1675 by the Dutch painter Cornelis de Bruijn.[124][125] It may be Jaffa's oldest existing mosque. Built originally in 1675,[126] changes to the structure have been made since then, such as the addition of a second floor and reconstruction of the upper part of the minaret. It was used by fishermen and sailors frequenting the port, and residents of the surrounding area. According to local legend, the wives of sailors living in Jaffa prayed there for the safe return of their husbands. The mosque was renovated in 1997.[citation needed]

Mahmoudia Mosque was built in 1812 by Abu Nabbut, governor of Jaffa from 1810 to 1820.[127] Outside the mosque is a water fountain (sabil) for pilgrims.[128]

Nouzha Mosque on Jerusalem Boulevard is Jaffa's main mosque today.

Archaeology

The majority of excavations in Jaffa are salvage in nature and have been conducted by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) since the 1990s. Excavations on Rabbi Pinchas Street, for example, in the flea market have revealed walls and water conduits dating to the Iron Age, Hellenistic, Early Islamic, Crusader and Ottoman periods. A limestone slab (50 cm × 50 cm or 20 in × 20 in) engraved with a menorah discovered on Tanchum Street is believed to be the door of a tomb.[129]

Additional efforts to conduct research excavations at that site included those of B. J. Isserlin (1950), Ze'ev Herzog of Tel Aviv University (1997–1999), and most recently the Jaffa Cultural Heritage Project (since 2007), directed by Aaron A. Burke (UCLA) and Martin Peilstocker (Johannes Gutenberg University).

In December 2020, archaeologists from the IAA revealed a 3,800-year-old jar containing the badly preserved remains of a baby dates back to the Middle Bronze Age.[130] "There's always the interpretation that the jar is almost like a womb, so basically the idea is to return [the] baby back into Mother Earth, or into the symbolic protection of his mother", said archaeologist Alfredo Mederos Martin.[131] Researchers also covered the remains of at least two horses and pottery dated to the late Ottoman Empire, 232 seashells, 30 Hellenistic coins, 95 glass vessel fragments from the Roman and Crusader periods 14 fifth-century BCE rock-carved burials featuring lamps.[132][133]

Education

Collège des Frères de Jaffa is a French international school.

Tabeetha School in Jaffa was founded in 1863. It is owned by the Church of Scotland. The school provides education in English to children from Christian, Jewish and Muslim backgrounds.[134]

Muzot (Hebrew: מוזות) is an arts school in old Jaffa that caters to teenagers who haven't successfully integrated into traditional schools. It offers them a unique opportunity to combine artistic pursuits with academic studies leading to a matriculation certificate.[135]

The democratic school in Jaffa established in 2004 is based on the ideas of democratic education, catering students from 1st to 12th grade.[136]

The campus of the Academic College of Tel Aviv-Yafo is a public college, hosting more than 4500 Israeli and Arab students.[137] The college's faculties include computer science, economics and management, information systems, psychology and nursing.[138]

Local governance, politics

Administratively, Jaffa constitutes Borough 7 of the Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality, and is divided into four sub-boroughs and twelve neighborhoods.[139]

Compared to Tel Aviv-Yafo as a whole, votes for Arab parties are especially prevalent in Jaffa in national elections.[140] In the 2018 Tel Aviv-Jaffa city council election, the Yafa list, which represents the Arab population of Jaffa, received 28% of the vote in Jaffa, making it the most voted party there; the second place was taken by the Hadash-affiliated[141] We are the City list, with 14% of the vote.[142] Among Jewish political parties, right-wing parties such as Shas and Likud perform better in Jaffa relative to the municipality-wide results,[142] similarly to the working-class neighborhoods in southern Tel Aviv;[140] in particular, Shas received 12% of the vote in Jaffa in the 2018 city council elections, making it the third-most voted for party in Jaffa.[142]

Socioeconomic and political problems

Jaffa suffers from drug problems, high crime rates and violence.[citation needed] Some Arab residents have alleged that the Israeli authorities are attempting to Judaize Jaffa by evicting Arab residents from houses owned by the Amidar government-operated public housing company. Amidar representatives say the residents are illegal squatters.[143]

Transportation

Ottoman station, now leisure venue

Jaffa Railway Station was the first railway station in the Middle East. It served as the terminus for the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway. The station opened in 1891 and closed in 1948. In 2005–09, the station was restored and converted into an entertainment and leisure venue marketed as "HaTachana", Hebrew for "the station".[144]

Bus and tramway (light rail)

Jaffa is served by the Dan Bus Company, which operates buses to various neighborhoods of Tel Aviv and Bat Yam.

The Red Line of the Tel Aviv Light Rail, inaugurated in 2023, crosses Jaffa north to south along Jerusalem Boulevard.

Railway

Of the current stations in the Israel Railways network, the Holon Junction and Holon–Wolfson railway stations sit on the boundary between Jaffa and Holon, while Tel Aviv HaHagana is in Tel Aviv proper, slightly to the east of Jaffa.

In popular culture

Jaffa cakes, a British confection, are named after Jaffa oranges and are therefore indirectly a namesake of Jaffa.

The Knight Of Jaffa is the second episode of the Doctor Who story The Crusade (1965), set in Palestine during the Third Crusade. The 1981 film Clash of the Titans is set in ancient Joppa. The 2009 Oscar-nominated film Ajami is set in modern Jaffa.

Notable residents

- Asma Agbarieh (born 1974), Israeli Arab journalist and political activist

- Hanan Al-Agha (1948–2008), Palestinian plastic artist

- Shmuel Yosef Agnon (1888–1970), Nobel Prize-winning author

- Dahn Ben-Amotz (1924–1989), radio broadcaster and author

- Yitzhak Ben-Zvi (1884–1963), historian, Labor Zionist leader, and President of Israel

- Benny Hinn (born 1953), TV evangelist and preacher

- Yosef Eliyahu Chelouche (1870–1934), one of the founders of Tel Aviv; businessman

- Joseph Constant (1892–1969), sculptor and writer

- Ismail al-Faruqi (1921–1986), Palestinian-American philosopher

- Lea Gottlieb (1918–2012), Israeli founder and fashion designer of Gottex

- Ibtisam Mara'ana (born 1975), Arab-Israeli filmmaker and member of the Knesset

- Victor Norris Hamilton (born c. 1919), Palestinian-born American cryptologist

- J. E. Hanauer (1850–1938), author, photographer, and Canon of St George's Church

- Hilmi Hanoun (1913–2001), writer and politician

- Yizhar Harari (1908–1978), Zionist activist and Israeli politician

- Haim Hazan (1937–1994), Israeli basketball player

- Zeev Hershkowitz, former Israeli footballer

- Nadia Hilou (1953–2015), Arab-Israeli politician

- Pinhas Hozez (born 1957), Israeli basketball player

- Issa El-Issa (1878–1950), Palestinian journalist

- Daoud El-Issa (1903–1983), Palestinian journalist

- Yousef El-Issa (1870–1948), Palestinian journalist

- Raja El-Issa (1922–2008), Palestinian journalist

- Michel Loève (1907–1979), probabilist and mathematical statistician

- Haim Ramon (born 1950), Israeli politician

- Sasha Roiz (born 1973), Canadian actor

- Yoav Saffar (born 1975), Israeli basketball player

- Yosef Sapir (1902–1972), Israeli politician

- Haim Starkman (born 1944), Israeli basketball player

- Rifaat Turk (born 1954), Arab-Israeli football player and manager, and deputy mayor of Tel Aviv

See also

- Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa

- County of Jaffa and Ascalon (under the Crusaders)

- History of Palestinian journalism

References

- ^ Lior, Ilan (28 February 2011). "Tel Aviv to build affordable housing for Jaffa's Arab residents". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ One example of this legend is the 16th-century French pilgrim Denis Possot who recorded, "Jaffe, est le port de la Terre saincte, anciennement nommé Joppe, faict et construict premierment en ville et cité grande à merveilles et de grant renom, par Japhet, fils de Noé." in his Le Voyage de la Terre Sainte (Geneva: Slatkine Reprints 1971, reprint of Paris edition, 1890, orig. 1532), p. 155.

- ^ Another pilgrim, Sir Richard of Guylforde, wrote,"This Jaffe was sometyme a grete Cytie [...] and it was one of the firste Cyties of the worlde founded by Japheth, Noes sone, and beryth yet his name." In the pilgrimage narrative from 1506, recorded by his chaplain in 1511, edited by Sir Henry Ellis (London: Camden Society, 1851), p. 16.

- ^ a b c le Strange, 1890, pp. 550-551

- ^ Peilstöcker, Martin; Burke, Aaron A., eds. (2011). The History and Archaeology of Jaffa 1. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press at UCLA. doi:10.2307/j.ctvdjrrkm. ISBN 978-1-931745-81-9. JSTOR j.ctvdjrrkm.

- ^ Stacey Jennifer Miller, The Lion Temple of Jaffa: Archaeological Investigations of the Late Bronze Age Egyptian Occupation in Canaan. BA thesis Archived 19 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, University of California, Los Angeles, 2012

- ^ ====Late Bronze ==== Aaron A. Burke and Martin Peilstöcker, The Egyptian Fortress in Jaffa Archived 18 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine, Popular Archaeology, 3 March 2013

- ^ a b Wachsmann, Shelley; Burke, Aaron A.; Dunn, Richard K.; Avnaim-Katav, Simona (2022). "'He Went Down to Joppa and Found a Ship Going to Tarshish' (Jonah 1:3): Landscape Reconstruction at Jaffa and a Potential Early Harbour". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 51 (2): 267–303. Bibcode:2022IJNAr..51..267W. doi:10.1080/10572414.2022.2148819. ISSN 1057-2414. Archived from the original on 10 July 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ a b Anson F. Rainey (February 2001). "Herodotus' Description of the East Mediterranean Coast". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (321). The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research: 58–59. doi:10.2307/1357657. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1357657. S2CID 163534665. Archived from the original on 24 September 2022. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "IV. Ioppe", Volume 3 South Coast: 2161-2648, De Gruyter, pp. 19–31, 14 July 2014, doi:10.1515/9783110337679.19, ISBN 978-3-11-033767-9, archived from the original on 19 June 2024, retrieved 19 June 2024

- ^ a b c Peilstöcker, Martin (2007). "Urban Archaeology in Yafo (Jaffa): Preliminary Planning for Excavations and Research of a Mediterranean Port City". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 139 (3): 150. doi:10.1179/003103207x227292. ISSN 0031-0328. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ a b Rocca, Samuel (2008). Herod's Judaea: a Mediterranean State in the Classical World. Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 185, 191. ISBN 978-3-16-149717-9.

- ^ Atkinson, Kenneth (2016). A History of the Hasmonean State: Josephus and Beyond. T & T Clark Jewish and Christian texts series. London; New York: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 129, 132. ISBN 978-0-567-66902-5. OCLC 949219870.

- ^ Josephus (1981). Josephus Complete Works. Translated by William Whiston. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. p. 331. ISBN 0-8254-2951-X., s.v. Antiquities 15.9.6. Archived 5 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine (15.331)

- ^ Strabo, Geographica, 16.2.28

- ^ a b Rogers, Guy MacLean (2021). For the Freedom of Zion: the Great Revolt of Jews against Romans, 66-74 CE. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-300-24813-5.

- ^ Radan, George T. (1988). "The strategic and commercial importance of Jaffa, 66–69 CE". Mediterranean Historical Review. 3 (1): 74–86. doi:10.1080/09518968808569539. ISSN 0951-8967. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Hezser, Catherine (19 August 2010). "Travel and Mobility". The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Daily Life in Roman Palestine. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199216437.013.0012. Archived from the original on 19 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Michel Le Quien, Oriens Christianus, III, 627.

- ^ Michel Le Quien, Oriens Christianus, III, 625–30, 1291; Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia catholica medii aevi, Munich, I, 297; II, 186.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, [1]

- ^ Pringle, Denys (1987). "The Planning of Some Pilgrimage Churches in Crusader Palestine". World Archaeology. 18 (3): 341–362. doi:10.1080/00438243.1987.9980011. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 124590.

- ^ Rabbi Joseph Schwarz, Descriptive Geography and Brief Historical Sketch of Palestine, archived from the original on 21 June 2011, retrieved 31 May 2011

- ^ Lorenzi, Rossella (15 November 2011), First Arabic Crusader Inscription Found, Discovery News, archived from the original on 1 May 2012, retrieved 23 November 2011

- ^ "Who Were the Mamluks? | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ a b Kohn, George Childs (31 October 2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-95501-4. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ a b Wasserstein, David J.; Ayalon, Ami (17 June 2013). Mamluks and Ottomans: Studies in Honour of Michael Winter. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-57924-0. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ Cytryn-Silverman, Katia (15 December 2010). "The Mamluk Minarets of Ramla". Bulletin du Centre de Recherche Français À Jérusalem (21). Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ de la Brocquière, Bertrandon; Rossabi, Morris (2019). A mission to the medieval Middle East: the travels of Bertrandon de la Brocquière to Jerusalem and Constantinople. Translated by Johnes, Thomas. London New York Oxford New Delhi Sydney: I.B. Tauris. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-83860-794-4.

- ^ a b Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 151

- ^ Gotthard Deutsch and M. Franco (1903). "Jaffa". Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ Joannes Cotovicus (1619). Itinerarium Hierosolymitanum et Syriacum. Antwerp: apud Hieronymum Verdussium. p. 135.

- ^ Thomson, 1859, vol 2, p. 275

- ^ a b Jacques-François Miot (1814). Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des expéditions en Égypte et en Syrie., quoted in Véronique Nahoum-Grappe (2002). "The anthropology of extreme violence: the crime of desecration". International Social Science Journal. 54 (174): 549–557. doi:10.1111/1468-2451.00409.

- ^ Jaffa: a City in Evolution Ruth Kark, Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Jerusalem, 1990, pp. 8–9

- ^ Thomson, page 515.

- ^ The digitalization project of the 19th century censuses in Eretz Israel done under the auspices of Sir Moses Montefiore, archived from the original on 8 November 2012, retrieved 31 May 2011

- ^ Friedman, Lior (5 April 2009). "The mountain of despair". Haaretz.com. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ Ellen Clare Miller, 'Eastern Sketches — notes of scenery, schools and tent life in Syria and Palestine'. Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Company. 1871. Page 97. See also Miller's populations of Damascus, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nablus and Samaria

- ^ Thompson (above) writing in 1856 has '25 years ago the inhabitants of the city and gardens were about 6000; now there must be 15,000 at least...' Considering the length of time he lived in the area this may be a more accurate count.

- ^ Jaffa, an Historical Survey Archived 26 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Written with the assistance of Tzvi Shacham, the curator of the Antiquities Museum of Tel Aviv–Jaffa

- ^ Rav Hillel Rachmani. "Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook". Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ a b c Jaffa: A City in Evolution Ruth Kark, Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Jerusalem, 1990, pp. 256–257.

- ^ Dr Frankl, translated by P. Beaton, 'The Jews in the East'. Volume 1. Hurst and Blackett, London, 1859. Page 345. He adds 'The community is poor, and receives no alms from any quarter.' which resulted in some envy of the 'our bethren' in Jerusalem.

- ^ Jaffa: A City in Evolution Ruth Kark, Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Jerusalem, 1990, pp. 244–246.

- ^ Thompson, page 517.

- ^ Jaffa: A City in Evolution Ruth Kark, Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Jerusalem, 1990, p.262.

- ^ Miller, page 97: 'The orange gardens are the finest in the East; and during the late winter and early spring, little white sailed vessels from Greece, Constantinople and the islands of the Archipelago, lie in calm weather at a short distance from the coast, waiting to carry away the fruit'.

- ^ Jaffa: A City in Evolution Ruth Kark, Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Jerusalem, 1990, pp. 242.

- ^ Thomson p.517: Sidon has best bananas, Jaffa the best pomegranates, oranges of Sidon are more juicy and have richer flavour. Jaffa oranges hang on the trees much later, and will bear shipping to distant regions.'

- ^ a b c Issawi, 2006, p. 127 Archived 15 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Basan, 2007, p. 83 Archived 15 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ladaniya, 2008, pp. 48–49 Archived 18 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Krämer, 2008, p. 91.

- ^ Gerber, 1982.

- ^ LeVine, 2005, p. 272.

- ^ LeVine, 2005, p. 34 Archived 15 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Friedman, Isaiah (1971). "German Intervention on Behalf of the "Yishuv"", 1917, Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 33, pp. 23–43.

- ^ Barron, 1923, p.6

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 13

- ^ Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the disturbances in the British Mandate of Palestine in May 1921, with correspondence relating thereto (Disturbances), 1921, Cmd. 1540, p. 60.

- ^ Honig, Sarah (30 April 2009). "Another Tack: The May Day Massacre of 1921". Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Ronen Shamir (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press

- ^ Viton, Albert (3 June 1936). "Why Arabs Kill Jews". The Nation. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f The Land That Become Israel: Studies in Historical Geography, ed. Ruth Kark, Yale University Press & Magnes Press, 1989, "Aerial Perspectives of Past Landscapes," Dov Gavish, pp. 316–317

- ^ a b Matthew Hughes, 'The Banality of Brutality: British Armed Forces and the Repression of the Arab Revolt in Palestine, 1936 – 39' Archived 28 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine, English Historical Review Vol. CXXIV No. 507 pp.323–354 pp.322.323.

- ^ Matthew Hughes, Britain’s Pacification of Palestine: The British Army, the Colonial State, and the Arab Revolt, 1936– 1939, Cambridge University Press2019 p.36.

- ^ Peel Report, quote: "Jaffa is an essentially Arab town in which the Jewish minority has recently been dwindling. We suggest that it should form part of the Arab State. The question of its communication with the latter presents no difficulty, since transit through the Jaffa-Jerusalem Corridor would be open to all. The Corridor, on the other hand, requires its own access to the sea, and for this purpose a narrow belt of land should be acquired and cleared on the north and south sides of the town. This would also solve the problem, sometimes said to be insoluble, created by the contiguity of Jaffa with Tel Aviv to the north and the nascent Jewish town [Bat Yam] to the south. If necessary, Mandatory police could be stationed on this belt. This arrangement may seem artificial, but it is clearly practicable."

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 27 Archived 7 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "שכונות יפו חוזרות ודורשות: סיפוח! העבודות בשכונה נמסרות ,למציע הזול ביותר" | הבקר | 13 יולי 1945 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "סיפוח מהיר לתל־אביב תובעים תושבי שני יפו | הבקר | 10 אפריל 1947 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ "השכונות היהודיות של יפו דורשות סיפוח מידי לתל־אביב | הארץ | 5 אוגוסט 1943 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 3 March 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- ^ A/RES/181(II)(A+B), Resolution 181 (II). Future government of Palestine (UN Partition Plan details), United Nations General Assembly, 29 November 1947, archived from the original on 16 April 2013,

The area of the Arab enclave of Jaffa consists of that part of the town-planning area of Jaffa which lies to the west of the Jewish quarters lying south of Tel-Aviv, to the west of the continuation of Herzl street up to its junction with the Jaffa-Jerusalem road, to the south-west of the section of the Jaffa-Jerusalem road lying south-east of that junction, to the west of Miqve Israel lands, to the north-west of Holon local council area, to the north of the line linking up the north-west corner of Holon with the north-east corner of Bat Yam local council area and to the north of Bat Yam local council area. The question of Karton quarter will be decided by the Boundary Commission, bearing in mind among other considerations the desirability of including the smallest possible number of its Arab inhabitants and the largest possible number of its Jewish inhabitants in the Jewish State.

- ^ Golan, Arnon (2012). "The Battle for Jaffa, 1948". Middle Eastern Studies. 48 (6): 997–1011. doi:10.1080/00263206.2012.734501. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 41721193. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Radai, Itamar (March 2011). "Jaffa, 1948: The fall of a city". Journal of Israeli History. 30 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1080/13531042.2011.553064.

- ^ Joseph, Dov (1960). The faithful city: the siege of Jerusalem, 1948. Simon and Schuster. p. 24. LCCN 60-10976. OCLC 266413.

In an exchange of letters between Mayor Yisrael Rokach of Tel Aviv and Mayor Youssef Haikal of Jaffa, both agreed to call upon the residents to maintain peace and quiet.

- ^ 'A survey of Palestine', printed 1946–1947. Reprinted ISP, Washington, 1991 ISBN 0-88728-211-3. Page 474: Exports of citrus fruit total value in Palestine Pounds, 1938/39 = P£4,355,853. 1944/45 = P£1,474,854. Ironically, due to the Nazi conquest of the Netherlands, Tel Aviv's trade in polished diamonds had increased over three-fold to P£3,235,117. Page 476

- ^ a b c Benny Morris (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

(p. 114) And rifts among the Jaffa Arabs from the beginning subverted all efforts at peacemaking. In February, Ben-Gurion wrote to Shertok that Heikal, through a British intermediary, was trying to secure an agreement with Tel Aviv but that the new irregulars' commander, 'Abdul Wahab 'Ali Shihaini, had blocked him. .... According to Ben-Gurion, Shihaini had answered: 'I do not mind [the] destruction [of] Jaffa if we secure [the] destruction [of] Tel Aviv. As in Haifa, the irregulars intimidated the local population, echoing the experience of 1936–1939. '. . . The inhabitants were more afraid of their defenders-saviours than of the Jews their enemies', wrote Nimr al Khatib. (p. 115) But Arab notables, through British intermediaries, continued to press for a wider citrus agreement. ... In the end, a formal agreement was never concluded. But neither was a complete blockade imposed on Jaffa, and the bilateral orange-picking and -exporting continued largely unhampered.

- ^ Pritzke, Herbert (1956). Bedouin Doctor — The adventures of a German in the Middle East. Translated by Richard Graves. Weidenfeld and Nicolson (1957), copyright Ullstein and Co, Vienna (1956). Page 149: "At that time the Arab Brigade in Jaffa consisted of seven Germans, one hundred and fifty Jugoslavs, thirty Egyptians and two hundred Lebanese and Syrians. There were very few Arabs among them as these preferred irregular warfare with the National Guard ..."

- ^ Radai, Itamar (2016). Palestinians in Jerusalem and Jaffa, 1948. Routledge. p. 140.

- ^ Morris 1987, p. 47.

- ^ a b Morris 1987, p. 95.

- ^ Menachem Begin, 'The Revolt — story of the Irgun'. Translated by Samuel Katz. Hadar Publishing, Tel Aviv. 1964. pp. 355–371.

- ^ a b Morris 1987, p. 100.

- ^ "טוראי אליהו-אדי טמלר" [Private Eliyahu-Edi Tamler]. Yazkor (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 18 February 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ Eugene Rogan (2012). The Arabs: A History – Third Edition. Penguin. p. 331. ISBN 9780718196837. Archived from the original on 9 April 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ^ Begin, page 363.

- ^ Morris 1987, p. 101, "On 18 May Ben-Gurion visited the conquered city for the first time and commented:"I couldn't understand: Why did the inhabitants of Jaffa leave?"

- ^ Jon Kimche, 'Seven Falen Pillars; The Middle East, 1915–1950'. Secker and Warburg, London. 1950. Page 224 :'the orgy of looting and wanton destruction which hangs like a black pall over almost all the Jewish military successes.'

- ^ Karpel, Dalia (14 February 2008). "Wellsprings of memory". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 25 March 2009.

- ^ Yoav Gelber, Independence Versus Nakba; Kinneret–Zmora-Bitan–Dvir Publishing, 2004, ISBN 965-517-190-6, p.104

- ^ Goldhaber, Ravit; Schnell, Izhak (2007). "A Model of Multidimensional Segregation in the Arab Ghetto in Tel Aviv-Jaffa". Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie. 98 (5): 603–620. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9663.2007.00428.x.

- ^ a b c d e f "§ייפ1חח חרשםי של יפו לתל־אביב | ידיעות עירית תל אביב | 16 ספטמבר 1950 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnon Golan (1995), The demarcation of Tel Aviv–Yafo's municipal boundaries, Planning Perspectives, vol. 10, pp. 383–398.

- ^ "סיפוח יפו לת"־חוק א | הארץ | 14 יוני 1950 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "ממון התקציב דוחה את סיפוח יפו לת"א | הצפה | 13 פברואר 1950 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 27 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ "fliiiwR'^ ,; ל _w וול _! 1 _! _^ , | הצפה | 5 אוקטובר 1949 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 1 January 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "דו"ת ועדת הגבולות | ידיעות עירית תל אביב | 15 ינואר 1949 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ "תליאביב גדלה־ ב6300 דונם | הארץ | 28 דצמבר 1942 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "הוכפל שטחה של תל־_&ביב | הצפה | 30 נובמבר 1943 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "שכתות־הספר של תל־אביב | ידיעות עירית תל אביב | 15 דצמבר 1949 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ^ "יפו בשנת תשיא | ידיעות עירית תל אביב | 14 אוקטובר 1951 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ "Untitled | על המשמר | 3 ספטמבר 1954 | אוסף העיתונות | הספרייה הלאומית". Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2023.

- ^ Leshem, Noam (2017). Life after Ruin: The Struggles over Israel's Depopulated Arab Spaces. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107149472. Archived from the original on 30 December 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ^ Esther Zandberg: Where the Streets Have No Arabic Name, a Group of Women Reminds Us of Palestinian History Archived 20 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine Haaretz, 20 January 2022.

- ^ "רק חמישה רחובות ביפו נושאים שמות ערביים". הארץ. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "ברחובות שלנו: תושבי יפו הערבים נגד שמות הרחובות היהודיים". www.makorrishon.co.il. Archived from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ^ "Restoring Jaffa's past". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 5 March 2008. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Hip Jerusalem and historic Tel Aviv". www.bbc.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Areas to Visit (PDF), Tel Aviv Municipality, archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2012, retrieved 18 December 2012,

Today, local fisherman still use the harbor and the main hangars of the port have been restored and include art galleries

- ^ Ashley (20 September 2012), Jaffa Flea Market: a Place to Sharpen Those Haggling Skills!, archived from the original on 20 June 2017, retrieved 19 April 2012,

The Jaffa Flea Market [...] invites a younger, hipper crowd to inspect its newly added art galleries"

- ^ Kloosterman, Karin (29 November 2006), "Changes in the air for Ajami: A mixed Arab-Jewish neighborhood in Jaffa balances itself between rundown remnants of old-world charm and upscale gentrification", The Jerusalem Post, archived from the original on 4 November 2012, retrieved 18 December 2012

- ^ "Canada, Israel won the bid to acquire 7.6 acres in prestigious area of south Tel Aviv – will pay 211 million". TheMarker. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "Tel Aviv American Colony buildings for sale". 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "Restoring an icon: From derelict warehouses to a vibrant hub « קרן תל-אביב יפו". telavivfoundation.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Ron, Oded; Fargion, Ben; Hadad Haj Yahia, Nasrin. "התושבים בערים המעורבות" (PDF). Israel Democracy Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "האוכלוסיה הערבית בתל אביב יפו בראי המספרים" (PDF). Tel Aviv Municipality. January 2024.

- ^ "Tel aviv yafo". Tel-Aviv/Yafo Municipality.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. "v.69". Natural History.

- ^ "Old Jaffa Museum". Archived from the original on 26 December 2008.

- ^ "Project Partners". The Jaffa Cultural Heritage Project. The Jaffa Museum of Archaeology. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "В день памяти праведной Тавифы на подворье Русской духовной миссии в Яффо совершена праздничная Литургия" [On the feast day of Tabitha of righteous memory, a festive liturgy performed in the courtyard of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jaffa]. Russian Orthodox Church. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ^ Zafran, Eric; Resendez, Sydney (1998). French Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Artists born before 1790. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston. p. 189. ISBN 0878464611.

- ^ Petersen, 2002, p. 166 Archived 11 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James Silk Buckingham, Travels in Palestine, Through the Countries of Bashan and Gilead, East of the River Jordan: Including a Visit to the Cities of Geraza and Gamala, in the Decapolis, Archived 18 September 2024 at the Wayback Machine Longman, 1821 mentions Lebrun's visit in 1675,(coinciding with the date the Sea Mosque is said to have been built)

- ^ Dan Mirkin, 'The Ottoman Port of Jaffa: A Port without a Harbour,' Aaron A. Burke, Katherine Strange Burke, Martin Peilstocker (eds.) The History and Archaeology of Jaffa 2, ISD LLC 2017, ISBN 978-1-938-77057-9 pp.121–155 p.152, n.16.

- ^ "History of Jaffa", ArtMag, Université Européenne de la Recherche, archived from the original on 18 September 2024, retrieved 18 December 2012

- ^ "Sabil Abu Nabbut". ArchNet Digital Library. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

- ^ "Archaeology News in Israel". Biblical Productions. 2008. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Davis-Marks, Isis. "Archaeologists in Israel Unearth 3,800-Year-Old Skeleton of Baby Buried in a Jar". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Trove spanning millennia emerges from construction in ancient Jaffa". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (21 December 2020). "3,800-year-old baby in a jar unearthed in Israel". livescience.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Archaeological dig in Jaffa unearths 3,800-year-old baby buried in a jar". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "History of Tabeetha". Tabeetha School in Jaffa. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Muzot - High School of the Arts". muzot-art-school. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Gher, Yonatan (23 August 2018). "How a democratic school works, and how it improves society". Archived from the original on 23 February 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ רותם, צחר; מאת (27 February 2004). "המכללה האקדמית ת"א-יפו תפתח שערי הקמפוס ביפו". הארץ (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on 18 September 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "The Academic College of Tel-Aviv – Yaffo". המועצ. Archived from the original on 27 October 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "אזורים%20בעיר" [20% areas in the city] (PDF). www.tel-aviv.gov.il (in Hebrew). p. 10.[dead link]

- ^ a b Haviv Rettig Gur, The 20th Knesset — parliament of a splintered, tribal Israel Archived 9 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "העמוד לא נמצא | המפלגה הקומוניסטית הישראלית". Archived from the original on 19 April 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ a b c "תוצאות%20הבחירות%20לראשות%20העירייה%20ולמועצת%20העירייה-%202018" [Results of the elections for the mayorship of the municipality and for the municipality council, 2018] (PDF). www.tel-aviv.gov.il (in Hebrew). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2023.

- ^ Hai, Yigal (28 April 2007). "Protesters rally in Jaffa against move to evict local Arab families". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2007.

- ^ "Hatachana – Culture, Entertainment & Leisure".

Bibliography