Ukrainians

This article may require copy editing for grammar. (February 2024) |

Українці | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

c. 46 million[1]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Ukraine 37,541,700 (2001)[2] | |

| Russia | 1,864,000 (2023)[citation needed] |

| Poland | 1,651,918 (2023)[3] |

| Canada | 1,359,655 (2016)[4] |

| Germany | 1,125,000 (2023)[5] |

| United States | 1,028,492 (2016)[6] |

| Brazil | 600,000–1,500,000 (2015)[7] |

| Czech Republic | 636,282 (2023)[8] |

| Kazakhstan | 387,000 (2021)[9] |

| Italy | 347,183 (2023)[10] |

| Argentina | 305,000 (2007)[11][12] |

| Romania | 251,923 (2023)[13][14] |

| Slovakia | 228,637 (2023)[15][16] |

| Moldova | 181,035 (2014)[17][18] |

| Belarus | 159,656 (2019)[3] |

| Uzbekistan | 124,602 (2015)[9] |

| Netherlands | 115,840 (2024)[19] |

| Spain | 111,726 (2020)[20] |

| France | 106,697 (2017)[21][22] |

| Turkey | 95,000 (2022)[23][24] |

| Latvia | 50,699 (2018)[25] |

| Portugal | 45,051 (2015)[9] |

| Australia | 38,791 (2014)[26][27] |

| Greece | 32,000 (2016)[28] |

| Israel | 30,000–90,000 (2016)[29] |

| United Kingdom | 23,414 (2015)[9] |

| Estonia | 23,183 (2017)[30] |

| Georgia | 22,263 (2015)[9] |

| Azerbaijan | 21,509 (2009)[31] |

| Kyrgyzstan | 12,691 (2016)[32] |

| Lithuania | 12,248 (2015)[9] |

| Denmark | 12,144 (2018)[33] |

| Paraguay | 12,000–40,000 (2014)[34][35] |

| Austria | 12,000 (2016)[36] |

| United Arab Emirates | 11,145 (2017)[37] |

| Sweden | 11,069 (2019)[38] |

| Hungary | 10,996 (2016)[39] |

| Uruguay | 10,000–15,000 (1990)[40][41] |

| Switzerland | 6,681 (2017)[42] |

| Finland | 5,000 (2016)[43] |

| Jordan | 5,000 (2016)[44] |

| Languages | |

| Ukrainian,[45] Ukrainian Sign Language[46] | |

| Religion | |

| Majority Eastern Orthodoxy with Catholicism (Ukrainian Greek Catholicism and Latin Catholicism) minority | |

| Part of a series on |

| Ukrainians |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| Languages and dialects |

| Religion |

| Sub-national groups |

| Closely-related peoples |

Ukrainians (Ukrainian: українці, romanized: ukraintsi, pronounced [ʊkrɐˈjinʲts⁽ʲ⁾i])[47] are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to the Eastern Orthodox Church. By total population, the Ukrainians form the second-largest Slavic ethnic group after the Russians.[1]

Historically, under rule from various realms, the Ukrainians have been given various names by their rulers.[48] Some of the states that have governed over the Ukrainian people include the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Habsburg monarchy, the Austrian Empire, and then Austria-Hungary. The East Slavic population inhabiting the territories of modern-day Ukraine were known as Ruthenians, referring to the territory of Ruthenia; the Ukrainians living under the Russian Empire were known as Little Russians, named after the territory of Little Russia.[49]

The ethnonym Ukrainian (a term associated with the Cossack Hetmanate) was adopted following the Ukrainian national revival.[50] Their affinity with the Cossacks is frequently emphasized, for example, in the Ukrainian national anthem.[51] Citizens of Ukraine are also called Ukrainians regardless of their ethnic origin,[52] and Ukrainian nationals identify themselves as a civic nation.[53]

Ethnonym

The modern name Ukraintsi (Ukrainians) is derived from Ukraina (Ukraine), a name first documented in the Kievan Chronicle under the year 1187. The terms Ukrainiany (first recorded in the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle under the year 1268[a]), Ukrainnyky, and even narod ukrainskyi (the Ukrainian people) were used sporadically before Ukraintsi attained currency under the influence of the writings of Ukrainian activists in Russian-ruled Ukraine in the 19th century.[56] From the 14th to the 16th centuries the western portions of the European part of what is now known as Russia, plus the territories of northern Ukraine and Belarus (Ruthenia) were largely known as Rus, continuing the tradition of Kievan Rus'. People of these territories were usually called Rus or Rusyns (known as Ruthenians in Western and Central Europe).[57]

The Ukrainian language is, like modern Russian and Belarusian, a descendent of Old East Slavic.[58][59] In Western and Central Europe it was known by the exonym "Ruthenian". In the 16th and 17th centuries, with the establishment of the Zaporozhian Sich, names of Ukraine and Ukrainian began to be used in Sloboda Ukraine.[60] After the decline of the Zaporozhian Sich and the establishment of Imperial Russian hegemony in Left Bank Ukraine, Ukrainians became more widely known by Russians as "Little Russians", with the majority of Ukrainian élites espousing Little Russian identity and adopting the Russian language (as Ukrainian was outlawed in almost all contexts).[61][62][63] This exonym (regarded now as a humiliating imperialist imposition) did not spread widely among the peasantry which constituted the majority of the population.[64] Ukrainian peasants still referred to their country as "Ukraine" (a name associated with the Zaporozhian Sich, with the Hetmanate and with their struggle against Poles, Russians, Turks and Crimean Tatars) and to themselves and their language as Ruthenians/Ruthenian.[62][63][need quotation to verify]

With the publication of Ivan Kotliarevsky's Eneyida (Aeneid) in 1798, which established the modern Ukrainian language, and with the subsequent Romantic revival of national traditions and culture, the ethnonym Ukrainians and the notion of a Ukrainian language came into more prominence at the beginning of the 19th century and gradually replaced the words "Rusyns" and "Ruthenian(s)". In areas outside the control of the Russian/Soviet state until the mid-20th century (Western Ukraine), Ukrainians were known by their pre-existing names for much longer.[61][62][63][65] The appellation Ukrainians initially came into common usage in Central Ukraine[66][67] and did not take hold in Galicia and Bukovina until the latter part of the 19th century, in Transcarpathia until the 1930s, and in the Prešov Region until the late 1940s.[68][69][70]

The modern name Ukraintsi (Ukrainians) derives from Ukraina (Ukraine), a name first documented in 1187.[71] Several scientific theories attempt to explain the etymology of the term. According to the traditional theory, it derives from the Proto-Slavic root *kraj-, which has two meanings, one meaning the homeland as in "nash rodnoi kraj" (our homeland), and the other "edge, border", and originally had the sense of "periphery", "borderland" or "frontier region".[72][73][74] According to another theory, the term ukraina should be distinguished from the term okraina: whereas the latter term means "borderland", the former one has the meaning of "cut-off piece of land", thus acquiring the connotation of "our land", "land allotted to us".[72][75]

In the last three centuries the population of Ukraine experienced periods of Polonization and Russification, but preserved a common culture and a sense of common identity.[76][77]

Geographic distribution

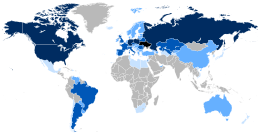

Most ethnic Ukrainians live in Ukraine, where they make up over three-quarters of the population. The largest population of Ukrainians outside of Ukraine lives in Russia where about 1.9 million Russian citizens identify as Ukrainian, while millions of others (primarily in southern Russia and Siberia) have some Ukrainian ancestry.[78] The inhabitants of the Kuban, for example, have vacillated among three identities: Ukrainian, Russian (an identity supported by the Soviet regime), and "Cossack".[79] Approximately 800,000 people of Ukrainian ancestry live in the Russian Far East in an area known historically as "Green Ukraine".[80]

In a 2011 national poll of Ukraine, 49% of Ukrainians said they had relatives living in Russia.[81]

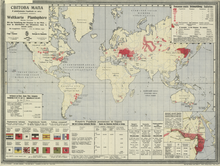

According to some previous assumptions,[citation needed] an estimated number of almost 2.4 million people of Ukrainian origin live in North America (1,359,655 in Canada and 1,028,492 in the United States). Large numbers of Ukrainians live in Brazil (600,000),[b] Kazakhstan (338,022), Moldova (325,235), Argentina (305,000), (Germany) (272,000), Italy (234,354), Belarus (225,734), Uzbekistan (124,602), the Czech Republic (110,245), Spain (90,530–100,000) and Romania (51,703–200,000). There are also large Ukrainian communities in such countries as Latvia, Portugal, France, Australia, Paraguay, the UK, Israel, Slovakia, Kyrgyzstan, Austria, Uruguay and the former Yugoslavia. Generally, the Ukrainian diaspora is present in more than one hundred and twenty countries of the world.[citation needed]

The number of Ukrainians in Poland amounted to some 51,000 people in 2011 (according to the Polish Census).[82] Since 2014, the country has experienced a large increase in immigration from Ukraine.[83][84] More recent data put the number of Ukrainian migrant workers at 1.2[85] – 1.3 million in 2016.[86][c]

In the last decades of the 19th century, many Ukrainians were forced by the Tsarist autocracy to move to the Asian regions of Russia, while many of their counterpart Slavs under Austro-Hungarian rule emigrated to the New World seeking work and better economic opportunities.[87] Today, large ethnic Ukrainian minorities reside in Russia, Canada, the United States, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Italy and Argentina.[citation needed] According to some sources, around 20 million people outside Ukraine identify as having Ukrainian ethnicity,[88][89][90] however the official data of the respective countries calculated together does not show more than 10 million. Ukrainians have one of the largest diasporas in the world.[citation needed]

Origin

The East Slavs emerged from the undifferentiated early Slavs in the Slavic migrations of the 6th and 7th centuries CE. The state of Kievan Rus united the East Slavs during the 9th to 13th centuries. East Slavic tribes cited[by whom?] as "proto-Ukrainian" include the Volhynians, Derevlianians, Polianians, and Siverianians and the less significant Ulychians, Tivertsians, and White Croats.[91] The Gothic historian Jordanes and 6th-century Byzantine authors named two groups that lived in the south-east of Europe: Sclavins (western Slavs) and Antes. Polianians are identified as the founders of the city of Kiev and as playing the key role in the formation of the Kievan Rus' state.[92] At the beginning of the 9th century, Varangians used the waterways of Eastern Europe for military raids and trade, particularly the trade route from the Varangians to the Greeks. Until the 11th century these Varangians also served as key mercenary troops for a number of princes in medieval Kiev, as well as for some of the Byzantine emperors, while others occupied key administrative positions in Kievan Rus' society, and eventually became slavicized.[93][94] Besides other cultural traces, several Ukrainian names show traces of Norse origins as a result of influences from that period.[95][96]

Differentiation between separate East Slavic groups began to emerge in the later medieval period, and an East Slavic dialect continuum developed within the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, with the Ruthenian language emerging as a written standard. The active development of a concept of a Ukrainian nation and the Ukrainian language began with the Ukrainian National Revival in the early 19th century in times when Ruthenians (Русини) changed their name due to the region name. In the Soviet era (1917–1991), official historiography emphasized "the cultural unity of 'proto-Ukrainians' and 'proto-Russians' in the fifth and sixth centuries".[97]

A poll conducted in April 2022 by "Rating" found that the vast majority (91%) of Ukrainians (excluding the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine) do not support the thesis that "Russians and Ukrainians are one people".[98]

Genetics and genomics

Ukrainians, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:[99] Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, descended from populations associated with the Paleolithic Epigravettian culture;[100] Neolithic Early European Farmers who migrated from Anatolia during the Neolithic Revolution 9,000 years ago;[101] and Yamnaya Steppe pastoralists who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe of Ukraine and southern Russia in the context of Indo-European migrations 5,000 years ago.[99]

In a survey of 97 genomes for diversity in full genome sequences among self-identified Ukrainians from Ukraine, a study identified more than 13 million genetic variants, representing about a quarter of the total genetic diversity discovered in Europe.[102] Among these nearly 500,000 are previously undocumented and likely to be unique for this population. Medically relevant mutations whose prevalence in the Ukrainian genomes differed significantly compared to other European genome sequences, particularly from Western Europe and Russia.[103] Ukrainian genomes form a single cluster positioned between the Northern on one side, and Western European populations on the other.[4]

There was a significant overlap with Central European populations as well as with people from the Balkans.

In addition to the close geographic distance between these populations, this may also reflect the insufficient representation of samples from the surrounding populations.[citation needed]

The Ukrainian gene-pool includes the following Y-haplogroups, in order from the most prevalent:[104]

Roughly all R1a Ukrainians carry R1a-Z282; R1a-Z282 has been found significantly only in Eastern Europe.[105] Chernivtsi Oblast is the only region in Ukraine where Haplogroup I2a occurs more frequently than R1a, much less frequent even in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.[106] In comparison to their northern and eastern neighbors, Ukrainians have a similar percentage of Haplogroup R1a-Z280 (43%) in their population—compare Belarusians, Russians, and Lithuanians and (55%, 46%, and 42% respectively). Populations in Eastern Europe which have never been Slavic do as well. Ukrainians in Chernivtsi Oblast (near the Romanian border) have a higher percentage of I2a as opposed to R1a, which is typical of the Balkan region, but a smaller percentage than Russians of the N1c1 lineage found among Finno-Ugric, Baltic, and Siberian populations, and also less R1b than West Slavs.[107][108][109] In terms of haplogroup distribution, the genetic pattern of Ukrainians most closely resembles that of Belarusians. The presence of the N1c lineage is explained by a contribution of the assimilated Finno-Ugric tribes.[110]

Related ethnic groups

Within Ukraine and adjacent areas, there are several other distinct ethnic sub-groups, especially in western Ukraine: places like Zakarpattia and Halychyna. Among them the most known are Hutsuls,[111] Volhynians, Boykos and Lemkos (otherwise known as Carpatho-Rusyns – a derivative of Carpathian Ruthenians), each with particular areas of settlement, dialect, dress, and folk traditions.[112]

History

Early history

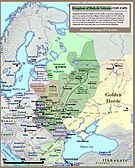

Ukraine has had a very turbulent history, a fact explained by its geographical position. In the 9th century the Varangians from Scandinavia conquered the proto-Slavic tribes on the territory of today's Ukraine, Belarus, and western Russia and laid the groundwork for the Kievan Rus' state. The ancestors of the Ukrainian nation such as Polianians had an important role in the development and culturalization of Kievan Rus' state. The internecine wars between Rus' princes, which began after the death of Yaroslav the Wise,[113] led to the political fragmentation of the state into a number of principalities. The quarreling between the princes left Kievan Rus' vulnerable to foreign attacks, and the invasion of the Mongols in 1236. and 1240. finally destroyed the state. Another important state in the history of the Ukrainians is the Kingdom of Ruthenia (1199–1349).[114][115]

The third important state for Ukrainians is the Cossack Hetmanate. The Cossacks of Zaporizhzhia since the late 15th century controlled the lower bends of the river Dnieper, between Russia, Poland and the Tatars of Crimea, with the fortified capital, Zaporozhian Sich. Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky is one of the most celebrated and at the same time most controversial political figures in Ukraine's early-modern history. A brilliant military leader, his greatest achievement in the process of national revolution was the formation of the Cossack Hetmanate state of the Zaporozhian Host (1648–1782). The period of the Ruin in the late 17th century in the history of Ukraine is characterized by the disintegration of Ukrainian statehood and general decline. During the Ruin Ukraine became divided along the Dnieper River into Left-Bank Ukraine and Right-Bank Ukraine, and the two-halves became hostile to each other. Ukrainian leaders during the period are considered to have been largely opportunists and men of little vision who could not muster broad popular support for their policies.[116] There were roughly 4 million Ukrainians at the end of the 17th century.[117]

At the final stages of the First World War, a powerful struggle for an independent Ukrainian state developed in the central Ukrainian territories, which, until 1917, were part of the Russian Empire. The newly established Ukrainian government, the Central Rada, headed by Mykhailo Hrushevsky, issued four universals, the Fourth of which, dated 22 January 1918, declared the independence and sovereignty of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR) on 25 January 1918. The session of the Central Rada on 29 April 1918 ratified the Constitution of the UNR and elected Hrushevsky president.[76]

Soviet period

During the 1920s, under the Ukrainisation policy pursued by the national Communist leadership of Mykola Skrypnyk, Soviet leadership encouraged a national renaissance in the Ukrainian culture and language. Ukrainisation was part of the Soviet-wide policy of Korenisation (literally indigenisation).[citation needed]

During 1932–1933, millions of Ukrainians were starved to death by the Soviet regime which led to a famine, known as the Holodomor.[118] The Soviet regime remained silent about the Holodomor and provided no aid to the victims or the survivors. But news and information about what was going on reached the West and evoked public responses in Polish-ruled Western Ukraine and in the Ukrainian diaspora. Since the 1990s the independent Ukrainian state, particularly under President Viktor Yushchenko, the Ukrainian mass media and academic institutions, many foreign governments, most Ukrainian scholars, and many foreign scholars have viewed and written about the Holodomor as genocide and issued official declarations and publications to that effect. Modern scholarly estimates of the direct loss of human life due to the famine range between 2.6 million[119][120] (3–3.5 million)[121] and 12 million[122] although much higher numbers are usually published in the media and cited in political debates.[123] As of March 2008, the parliament of Ukraine and the governments of several countries, including the United States have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide.[d]

Following the Invasion of Poland in September 1939, German and Soviet troops divided the territory of Poland. Thus, Eastern Galicia and Volhynia with their Ukrainian population became part of Soviet Ukraine. When the German armies invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, those regions temporarily became part of the Nazi-controlled Reichskommissariat Ukraine. In total, the number of ethnic Ukrainians who fought in the ranks of the Soviet Army is estimated from 4.5 million to 7 million. The pro-Soviet partisan guerrilla resistance in Ukraine is estimated to number at 47,800 from the start of occupation to 500,000 at its peak in 1944, with about 50% being ethnic Ukrainians. Of the estimated 8.6 million Soviet troop losses, 1.4 million were ethnic Ukrainians.[citation needed]

In 1943, under the command of Roman Shukhevych, UPA began the ethnic cleansing. Shukhevych was one of the perpetrators of the Galicia-Volhynia massacres of tens of thousands of Polish civilians. It is unclear to what extent Shuchevych was responsible for the massacres of Poles in Volhynia, but he certainly condoned them after some time, and also directed the massacres of Poles in Eastern Galicia. Historian Per Anders Rudling has accused the Ukrainian diaspora and Ukrainian academics of "ignoring, glossing over, or outright denying" his role in this and other war crimes.

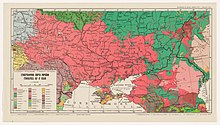

Historical maps of Ukraine

The Ukrainian state has occupied a number of territories since its initial foundation. Most of these territories have been located within Eastern Europe, however, as depicted in the maps in the gallery below, has also at times extended well into Eurasia and South-Eastern Europe. At times there has also been a distinct lack of a Ukrainian state, as its territories were on a number of occasions, annexed by its more powerful neighbours.

| Historical maps of Ukraine and its predecessors |

|---|

|

Ethnic/national identity

The watershed period in the development of modern Ukrainian national consciousness was the struggle for independence during the creation of the Ukrainian People's Republic from 1917 to 1921.[124] A concerted effort to reverse the growth of Ukrainian national consciousness was begun by the regime of Joseph Stalin in the late 1920s, and continued with minor interruptions until the most recent times. The man-made Famine of 1932–33, the deportations of the so-called kulaks, the physical annihilation of the nationally conscious intelligentsia, and terror in general were used to destroy and subdue the Ukrainian nation.[125] Even after Joseph Stalin's death the concept of a Russified though multiethnic Soviet people was officially promoted, according to which the non-Russian nations were relegated to second-class status[citation needed]. Despite this, many Ukrainians played prominent roles in the Soviet Union, including such public figures as Semen Tymoshenko.

The creation of a sovereign and independent Ukraine in 1991, however, pointed to the failure of the policy of the "merging of nations" and to the enduring strength of the Ukrainian national consciousness. Today, one of the consequences of these acts is Ukrainophobia.[126]

Biculturalism is especially present in southeastern Ukraine where there is a significant Russian minority. Historical colonization of Ukraine is one reason that creates confusion about national identity to this day.[127] Many citizens of Ukraine have adopted the Ukrainian national identity in the past 20 years. According to the concept of nationality dominant in Eastern Europe the Ukrainians are people whose native language is Ukrainian (an objective criterion) whether or not they are nationally conscious, and all those who identify themselves as Ukrainian (a subjective criterion) whether or not they speak Ukrainian.[128]

Attempts to introduce a territorial-political concept of Ukrainian nationality on the Western European model (presented by political philosopher Vyacheslav Lypynsky) were unsuccessful until the 1990s. Territorial loyalty has also been manifested by the historical national minorities living in Ukraine. The official declaration of Ukrainian sovereignty of 16 July 1990 stated that "citizens of the Republic of all nationalities constitute the people of Ukraine."[129][130]

Culture

Due to Ukraine's geographical location, its culture primarily exhibits Eastern European influence as well as Central European to an extent (primarily in the western region). Over the years it has been influenced by movements such as those brought about during the Byzantine Empire and the Renaissance. Today, the country is somewhat culturally divided with the western regions bearing a stronger Central European influence and the eastern regions showing a significant Russian influence. A strong Christian culture was predominant for many centuries, although Ukraine was also the center of conflict between the Catholic, Orthodox and Islamic spheres of influence.[citation needed]

Language

Ukrainian (украї́нська мо́ва, ukraі́nska móva) is the sole official language in Ukraine.[48] It belongs to the East Slavic branch of the Slavic languages. Written Ukrainian uses the Ukrainian alphabet, one of many based on the Cyrillic alphabet.[131] The language is a lineal descendant of the colloquial Old East Slavic language of the medieval state of Kievan Rus', which first split into Ruthenian and Russian.[132]: 2–3 The Ruthenian languages then evolved into modern-day Ukrainian, Belarusian and Rusyn.[132]: 53–60 In modern-day Ukraine, most of its population are also fluent in Russian and many use it as their native tongue.[52]

Comparisons are often made between Ukrainian and Russian. Yet, there is more mutual intelligibility with Belarusian,[133] and a very close lexical distance between the two.[134]: 13 Historically, state-inforced Russification saw the Ukrainian language banned as a subject from schools and as a language of instruction in the Russian Empire.[135] The oppression continued in various ways while Ukraine was a part of the Soviet Union.[136] However, the language continued to be used throughout the country, especially in the western part.[137]

Religions

Ukraine was inhabited by pagan tribes until Byzantine rite Christianity was introduced by the turn of the first millennium. It was imagined by later writers who sought to put Kievan Rus' Christianity on the same level of primacy as Byzantine Christianity that Apostle Andrew himself had visited the site where the city of Kiev would be later built.[citation needed]

However, it was only by the 10th century that the emerging state, the Kievan Rus', became influenced by the Byzantine Empire; the first known conversion was by the Princess Saint Olga who came to Constantinople in 945 or 957. Several years later, her grandson, Prince Vladimir baptised his people in the Dnieper River. This began a long history of the dominance of the Eastern Orthodoxy in Ruthenia (Ukraine).[citation needed]

Ukrainians are majority Eastern Orthodox Christians, and they form the second largest ethno-linguistic group among Eastern Orthodox in the world.[138][139] Ukrainians have their own autocephalous Orthodox Church of Ukraine headed by Metropolitan Epiphanius, where it is the most common church and in the small areas of Ukraine the Ukrainian Orthodox Church who were under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate is the smaller common. The Russian invasion of Ukraine impacted the religious identity of some Ukrainians.[citation needed]

In the Western region known as Halychyna, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, one of the Eastern Rite Catholic Churches has a strong membership. Since the fall of the Soviet Union there has been a growth of Protestant churches (Baptists, Evangelism, Pentecostalism)[e][140] There are also ethnic minorities that practice other religions, i.e. Crimean Tatars (Islam), and Jews and Karaim (Judaism).

Also, some Ukrainians are members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, Jehovah's Witnesses.

A 2020 survey conducted by the Razumkov Centre found that majority of Ukrainian populations was adhering to Christianity (81.9%). Of these Christians, 75.4% are Eastern Orthodox (34% of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine and 13.8% of the Moscow Patriarchate, and 27.6% are simply Orthodox), 8.2% are Greek Catholics, 7.1% are simply Christians, a further 1.9% are Protestants and 0.4% are Latin Catholics.[141] As of 2016, 16.3% of the population does not claim a religious affiliation, and 1.7% adheres to other religions.[142] According to the same survey, 70% of the population of Ukraine declared to be believers, but do not belong to any church. 8.8% do not identify themselves with any of the denominations, and another 5.6% identified themselves as non-believers.[142]

Cuisine

Ukrainian cuisine has been formed by the nation's tumultuous history, geography, culture and social customs. Chicken is the most consumed type of protein, accounting for about half of the meat intake. It is followed by pork and beef.[143]: 12 Vegetables such as potatoes, cabbages, mushrooms and beetroots are widely consumed.[144] Pickled vegetables are considered a delicacy.[145][146] Salo, which is cured pork fat, is considered the national delicacy.[147] Widely used herbs include dill, parsley, basil, coriander and chives.[148]

Ukraine is often called the "Breadbasket of Europe", and its plentiful grain and cereal resources such as rye and wheat play an important part in its cuisine; essential in making various kinds of bread.[149][150] Chernozem, the country's black-colored highly fertile soil, produces some of the world's most flavorful crops.[151]

Popular traditional dishes varenyky (dumpling), nalysnyky (crêpe), kapusnyak (cabbage soup), nudli (dumpling stew), borscht (sour soup) and holubtsi (cabbage roll).[149] Among traditional baked goods are decorated korovai and paska (easter bread).[152] Ukrainian specialties also include Chicken Kiev[148] and Kyiv cake. Popular drinks include uzvar (kompot),[148][153] ryazhanka,[154] and horilka.[148][153] Liquor (spirits) are the most consumed type of alcoholic beverage.[155] Alcohol consumption has seen a stark decrease, though by per capita, it remains among the highest the world.[156][155]

Music

Ukrainian music incorporates a diversity of external cultural influences. It also has a very strong indigenous Slavic and Christian uniqueness whose elements were used among many neighboring nations.[157][158]

Ukrainian folk oral literature, poetry, and songs (such as the dumas) are among the most distinctive ethnocultural features of Ukrainians as a people. Religious music existed in Ukraine before the official adoption of Christianity, in the form of plainsong "obychnyi spiv" or "musica practica". Traditional Ukrainian music is easily recognized by its somewhat melancholy tone. It first became known outside of Ukraine during the 15th century as musicians from Ukraine would perform before the royal courts in Poland (latter in Russia).[citation needed]

A large number of famous musicians around the world was educated or born in Ukraine, among them are famous names like Dmitry Bortniansky, Sergei Prokofiev, Myroslav Skoryk, etc. Ukraine is also the rarely acknowledged musical heartland of the former Russian Empire, home to its first professional music academy, which opened in the mid-18th century and produced numerous early musicians and composers.[159]

Dance

Ukrainian dance refers to the traditional folk dances of the peoples of Ukraine. Today, Ukrainian dance is primarily represented by what ethnographers, folklorists and dance historians refer to as "Ukrainian Folk-Stage Dances", which are stylized representations of traditional dances and their characteristic movements that have been choreographed for concert dance performances. This stylized art form has so permeated the culture of Ukraine, that very few purely traditional forms of Ukrainian dance remain today.[citation needed]

Ukrainian dance is often described as energetic, fast-paced, and entertaining, and along with traditional Easter eggs (pysanky), it is a characteristic example of Ukrainian culture recognized and appreciated throughout the world.[citation needed]

Symbols

Ukraine's national symbols include its flag and its coat of arms.

The national flag of Ukraine is a blue and yellow bicolour rectangle. The colour fields are of same form and equal size. The colours of the flag represent a blue sky above yellow fields of wheat.[160][161][162] The flag was designed for the convention of the Supreme Ruthenian Council, meeting in Lviv in October 1848. Its colours were based on the coat-of-arms of the Kingdom of Ruthenia.[163]

The Coat of arms of Ukraine features the same colours found on the Ukrainian flag: a blue shield with yellow trident—the symbol of ancient East Slavic tribes that once lived in Ukraine, later adopted by Ruthenian and Kievan Rus rulers.[citation needed]

Historiography

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2024) |

See also

- Demographics of Ukraine

- List of Ukrainian rulers

- List of Ukrainians

- Soviet population transfers

- Ukrainian dialects

Notes

- ^ In the context of a Polish raid on Kholm (modern Chełm), capital city of the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle notes sub anno 1268 (6776): "The Poles began to raid around Kholm (...) but they did not take anything, for [the people] had fled into the city, because the Лѧхове Оукраинѧнѣ" (Liakhove Ukrainianĕ, literally "Polish Ukrainians", "Ukrainian Poles" or "border Poles") "had let them know [that they enemy was coming]".[54][55]

- ^ See also Prudentópolis, Brazil.

- ^ Ukrainian citizens may take up employment in Poland without obtaining a work permit for a maximum period of 6 months within a year on the basis of a declaration of intention to entrust a job to a foreigner. In 2016, over 1.262 million such declarations were issued for Ukrainian nationals.[1] Archived 5 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine[2] Archived 10 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to the official recognition of the Famine as Genocide by the country. For example, after the statement issued by the Latvian Sejm on 13 March 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 (according to Ukrainian BBC: "Латвія визнала Голодомор ґеноцидом" Archived 19 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine), 16 (according to Korrespondent, Russian edition: "После продолжительных дебатов Сейм Латвии признал Голодомор геноцидом украинцев" Archived 6 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine), "more than 10" (according to Korrespondent, Ukrainian edition: "Латвія визнала Голодомор 1932–33 рр. геноцидом українців" )

- ^ For more information, see History of Christianity in Ukraine and Religion in Ukraine.

References

- ^ a b "УКРАЇНЦІ". resource.history.org.ua. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ "Number and composition population of Ukraine: population census 2001". State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. 5 December 2001. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ "Populacja cudzoziemców w Polsce w czasie COVID-19". Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census: Ethnic origin population". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten". Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ "Selected Social Characteristics in the United States 2010–2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- ^ "Brazil". The Ukrainian World Congress. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Foreigners by type of residence, sex and citizenship as at 31 December 2018". Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Total Migrant stock at mid-year by origin and by major area, region, country or area of destination, 1990–2015". United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2015). Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Ucraini in Italia". tuttitalia.it(Elaborazioni su dati ISTAT-L’Istituto nazionale di statistica). Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Inmigración Ucrania a la República Argentina" [Ukrainian immigration to Argentina]. Ucrania.com (in Spanish). 3 February 2008. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013.

- ^ "La inmigración Ucrania a la República Argentina" [Ukrainian immigration to Argentina]. Ucrania.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2005. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- ^ "Romanian 2011 census" (PDF). edrc.ro. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ^ Українська діаспора в Румунії [Ukrainian diaspora in Romania] (in Ukrainian). Буковина толерантна. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "SODB2021 - Obyvatelia - Základné výsledky". www.scitanie.sk. Archived from the original on 15 July 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Population and Housing Census in the Republic of Moldova, May 12–25, 2014". Biroul Național de Statistică al Republicii Moldova. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Статистический ежегодник 2017". Министерство экономического развития, Государственная служба статистики Приднестровской Молдавской Республики. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Cijfers opvang vluchtelingen uit Oekraïne in Nederland". rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). 24 March 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, comunidades, Sexo y Año. Datos provisionales 2020". INE. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- ^ "European countries". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Ukraine". 2 March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ "European countries". Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "У Туреччині підрахували кількість українців. Цифра вражає". svitua.com.ua. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības" (PDF). Latvijas Republikas Iekšlietu ministrijas. Pilsonības un migrācijas lietu pārvalde. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Australian Government – Department of Immigration and Border Protection. "Ukrainian Australians". Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. "Asia and Oceania countries". Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Ukrainians Аbroad". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ "Middle East and Africa". Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "Population by ethnic nationality, 1 January, years". Eesti Statistika. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Censuses of Republic of Azerbaijan 1979, 1989, 1999, 2009". State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Ethnic composition: 2016 estimation (data for regions)". Кыргыз Республикасынын Улуттук статистика комитети. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Population at the first day of the quarter by country of origin, ancestry, age, sex, region and time – Ukraine". Statistics Denmark. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- ^ "PARAGUAY". Ukrainian World Congress. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "La cooperación cultural y humanitaria entre Ucrania y Paraguay". Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Ucrania. Archived from the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Українці в Австрії. Botschaft der Ukraine in der Republik Österreich. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ "Євгеній Семенов: "Українська громада в ОАЕ об'єднується, не чекаючи жодних офіційних статусів чи закликів, і це – головне!"". chasipodii.net. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder, kön och år". Statistiska centralbyrån. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Vukovich, Gabriella (2018). Mikrocenzus 2016 – 12. Nemzetiségi adatok [2016 microcensus – 12. Ethnic data] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Hungarian Central Statistical Office. ISBN 978-963-235-542-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ "Our color-all over the world". State Migration Service of Ukraine and Foundation for assistance to refugees and displaced people "Compassion". Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ "С. А. Макарчук, Етнічна історія України". ebk.net.ua. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ Українці в Швейцарії. Botschaft der Ukraine in der Schweizerischen Eidgenossenschaft. Archived from the original on 15 July 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Ukrainians in Finland". Embassy of Ukraine in the Republic of Finland. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Ukrainian community in Jordan". Embassy of Ukraine in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ Ukrainians Archived 11 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine ... Ukrainians are people whose native language is Ukrainian (an objective criterion) whether or not they are nationally conscious, and all those who identify themselves as Ukrainian (a subjective criterion) whether or not they speak Ukrainian ...

- ^ Alternative Answers to the List of Issues for Ukraine. Prepared by the Ukrainian Society of the Deaf - UN Human Rights - Office of the High Commissioner, retrieved on 2.23.2016

- ^ "Ukrainian: definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ a b Arel, Dominique (2017–2018). "Language, Status, and State Loyalty in Ukraine". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (1/4). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 233–263. JSTOR 44983543.

- ^ Moser, Michael A. (2017–2018). "The Fate of the "Ruthenian or Little Russian" (Ukrainian) Language in Austrian Galicia (1772–1867)". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (1/4). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 87–104. JSTOR 44983536.

- ^ J. Boeck, Brian (2004–2005). "What's in a Name? Semantic Separation and the Rise of the Ukrainian National Name". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 27 (1/4). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 33–65. JSTOR 41036861.

- ^ Sysyn, Frank (1991). "The Reemergence of the Ukrainian Nation and Cossack Mythology". Social Research. 58 (4). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 845–864. JSTOR 40970677.

- ^ a b Kulyk, Volodymyr (21 October 2022). "Is Ukraine a Multiethnic Country?". Slavic Review. 81 (2). Cambridge University Press: 299–323. doi:10.1017/slr.2022.152.

- ^ Kappeler, Andreas (2023). Ungleiche Brüder: Russen und Ukrainer vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. München: C.H.Beck oHG. p. 260. ISBN 978-3-406-80042-9.

..., dass sich die Ukrainer in postsowjetischer Zeit zunehmend als politische Nation, als Willensnation, die mehrere ethnische und sprachliche Gruppen umfasst, verstehen.

[... in the post-Soviet era, Ukrainians increasingly see themselves as a political nation, a nation by will (Willensnation, civic nation) that includes several ethnic and linguistic groups.] - ^ Makhnovets 1989, p. 426.

- ^ Perfecky 1973, p. 85.

- ^ "Ukrainians and the Ukrainian Language". Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine. 2001. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ "The Ukrainian Highlanders: Hutsuls, Boikos, and Lemkos". People. Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

The oldest recorded names used for the Ukrainians are Rusyny, Rusychi, and Rusy (from Rus').

- ^ Yermolenko S. Y. (2000). History of the Ukrainian literary language Archived 3 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine // Potebnia Institute of Linguistics (NASU). In Ukrainian

- ^ Rusanivsky V. M. (2000). History of the Ukrainian language Archived 9 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine // Potebnia Institute of Linguistics (NASU). In Ukrainian

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. Ukrainian nationalism in the 1990s: a minority faith. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- ^ a b Luchenko, Valentyn (11 February 2009). Походження назви "Україна" [Origin of the name "Ukraine"] (in Ukrainian). luchenko.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Історія України IX-XVIII ст. Першоджерела та інтерпретації [History of Ukraine IX-XVIII centuries. Primary Sources and Interpretations] (in Ukrainian). Litopys.org.ua. Archived from the original on 10 December 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b c Україна. Русь. Назви території і народу [Ukraine. Rus'. Names of territories and nationality]. Encyclopedia of Ukraine – I (in Ukrainian). Vol. 1. Litopys.org.ua. 1949. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Serhii Plokhy (2008). Ukraine and Russia: Representations of the Past. University of Toronto Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8020-9327-1. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Kataryna Wolczuk (2001). The Moulding of Ukraine: The Constitutional Politics of State Formation. Central European University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-963-9241-25-1. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "All-Ukrainian National Congress". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 1984. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Universals of the Central Rada". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Himka, John-Paul (1993). "Ruthenians". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2016. "A historic name for Ukrainians corresponding to the Ukrainian rusyny"

- ^ Lev, Vasyl; Vytanovych, Illia (1993). "Populism, Western Ukrainian". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Baranovska N. M. (2012). Актуалізація ідей автономізму та федералізму в умовах національної революції 1917–1921 рр. як шлях відстоювання державницького розвитку України [Actualization of ideas of autonomy and federalism in the conditions of the national revolution of 1917–1921 as a path to defending the development of the statehood of Ukraine] (PDF) (in Ukrainian). Lviv Polytechnic National University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Ukrainians and the Ukrainian Language". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 1990. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b "З Енциклопедії Українознавства; Назва "Україна"". Litopys.org.ua. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Vasmer, Max (1953–1958). Russisches etymologisches Wörterbuch (in German). Vol. 1–3. Heidelberg: Winter.; Russian translation:Fasmer, Maks (1964–1973). Ėtimologičeskij slovar' russkogo jazyka. Vol. 1–4. transl. Oleg N. Trubačev. Moscow: Progress. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Ф.А. Гайда. От Рязани и Москвы до Закарпатья. Происхождение и употребление слова "украинцы" // Родина. 2011. № 1. С. 82–85". Edrus.org. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ "Україна" – це не "окраїна". Litopys.org.ua. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Struggle for Independence (1917–20)". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Mace, James (1993). "Ukrainization". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Ethnic composition of the population of the Russian Federation Archived 5 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine / Information materials on the final results of the 2010 Russian census Archived 22 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- ^ "Ukrainians". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2012. in: Roman Senkus et al. (eds.), The Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine, revised and updated content based on the five-volume Encyclopedia of Ukraine (University of Toronto Press, 1984–93) edited by Volodymyr Kubijovyc (vols. 1–2) and Danylo Husar Struk (vols. 3–5). Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) (University of Alberta/University of Toronto).

- ^ Ukrainians in Russia's Far East try to maintain community life Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Ukrainian Weekly. 4 May 2003.

- ^ "Why ethnopolitics doesn't work in Ukraine". al-Jazeera. 9 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ "Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013" (PDF). stat.gov.pl. Central Statistical Office of Poland. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "The migration of Ukrainians in times of crisis". 19 October 2015. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "There is almost as many Ukrainian immigrants in Poland as 2015 refugees in Europe. r/europe". reddit. 22 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2022. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Over 1.2 million Ukrainians working in Poland". praca.interia.pl. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "Poland Can't Get Enough of Ukrainian Migrants". Bloomberg L.P. 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- ^ "See map: Ukrainians: World Distribution". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ "UWC continually and diligently defends the interests of over 20 million Ukrainians". Ukrainian Canadian Congress. 25 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Ukrainian diaspora abroad makes up over 20 million". Ukrinform.ua. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "20 million Ukrainians live in 46 different countries of the world". Ukraine-travel-advisor.com. 5 December 2001. Archived from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Compare:

Volodymyr Kubijovyc; Danylo Husar Struk, eds. (1990). "Ukrainians". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) (University of Alberta/University of Toronto). Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

From the 7th century AD on, proto-Ukrainian tribes are known to have inhabited Ukrainian territory: the Volhynians, Derevlianians, Polianians, and Siverianians and the less significant Ulychians, Tivertsians, and White Croatians.

- ^ "Polianians (poliany)". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Zhukovsky, Arkadii. "Varangians". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

...Varangians assimilated rapidly with the local population.

- ^ "Kyivan Rus'". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. 1988. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

According to some sources, the first Varangian rulers of Rus' were Askold and Dyr.

- ^ Ihor Lysyj (10 July 2005). "The Viking "drakkar" and the Kozak "chaika"". The Ukrainian Weekly. Parsippany, New Jersey. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Andriy Pyrohiv (1998). "Vikings and the Lavra Monastery". Wumag.kiev.ua. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Serhy Yekelchyk (2004). Stalin's Empire of Memory: Russian-Ukrainian Relations in the Soviet Historical Imagination. University of Toronto Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8020-8808-6. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Восьме загальнонаціональне опитування: Україна в умовах війни (6 квітня 2022)". Ratinggroup.ua. 6 April 2022.

- ^ a b Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Posth, C.; Yu, H.; Ghalichi, A. (2023). "Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic to Neolithic European hunter-gatherers". Nature. 615 (2 March 2023): 117–126. Bibcode:2023Natur.615..117P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05726-0. PMC 9977688. PMID 36859578.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). "Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population". Science. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Oleksyk, Taras K; Wolfsberger, Walter W; Weber, Alexandra M; Shchubelka, Khrystyna; Oleksyk, Olga; Levchuk, Olga; Patrus, Alla; Lazar, Nelya; Castro-Marquez, Stephanie O; Hasynets, Yaroslava; Boldyzhar, Patricia; Neymet, Mikhailo; Urbanovych, Alina; Stakhovska, Viktoriya; Malyar, Kateryna; Chervyakova, Svitlana; Podoroha, Olena; Kovalchuk, Natalia; Rodriguez-Flores, Juan L; Zhou, Weichen; Medley, Sarah; Battistuzzi, Fabia; Liu, Ryan; Hou, Yong; Chen, Siru; Yang, Huanming; Yeager, Meredith; Dean, Michael; Mills, Ryan; Smolanka, Volodymyr (2021). "Genome diversity in Ukraine". GigaScience. 10 (1). doi:10.1093/gigascience/giaa159. PMC 7804371. PMID 33438729. Archived from the original on 12 March 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Large study provides new understanding of genome diversity in Ukrainian population". News-Medical. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Kushniarevich A, Utevska O (2015) "Genetic Heritage of the Balto-Slavic Speaking Populations: A Synthesis of Autosomal, Mitochondrial and Y-Chromosomal Data"

- ^ Di Luca, F.; Giacomo, F.; Benincasa, T.; Popa, L.O.; Banyko, J.; Kracmarova, A.; Malaspina, P.; Novelletto, A.; Brdicka, R. (2006). "Y-chromosomal variation in the Czech Republic" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 132 (1): 132–139. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20500. hdl:2108/35058. PMID 17078035. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ Utevska, O. M.; Chukhraeva, M. I.; Agdzhoyan, A. T.; Atramentova, L. A.; Balanovska, E. V.; Balanovsky, O. P. (21 September 2015). "Populations of Transcarpathia and Bukovina on the genetic landscape of surrounding regions" (PDF). Visnyk of Dnipropetrovsk University. Biology, Medicine. 6 (2): 133–140. doi:10.15421/021524. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ^ Semino O.; Passarino G.; Oefner P.J.; Lin A.A.; Arbuzova S.; Beckman L.E.; De Benedictis G.; Francalacci P.; Kouvatsi A.; Limborska S.; Marcikiae M.; Mika A.; Mika B.; Primorac D.; Santachiara-Benerecetti A.S.; Cavalli-Sforza L.L.; Underhill P.A. (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–1159. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- ^ Alexander Varzari, "Population History of the Dniester-Carpathians: Evidence from Alu Insertion and Y-Chromosome Polymorphisms" (2006)

- ^ Marijana Peričić et al. 2005, High-Resolution Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations.

- ^ Kharkov, V. N.; Stepanov, V. A.; Borinskaya, S. A.; Kozhekbaeva, Zh. M.; Gusar, V. A.; Grechanina, E. Ya.; Puzyrev, V. P.; Khusnutdinova, E. K.; Yankovsky, N. K. (1 March 2004). "Gene Pool Structure of Eastern Ukrainians as Inferred from the Y-Chromosome Haplogroups". Russian Journal of Genetics. 40 (3): 326–331. doi:10.1023/B:RUGE.0000021635.80528.2f. S2CID 25907265.

- ^ "A Ukrainian ethnic group which until 1946 lived in the most western part of Ukraine – Hutsuls". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 7 January 1919. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "A Ukrainian ethnic group which until 1946 lived in the most western part of Ukraine – Lemkos". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 August 1945. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Grand prince of Kyiv from 1019; son of Grand Prince Volodymyr the Great and Princess Rohnida of Polatsk". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "The first state to arise among the Eastern Slavs". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "A state founded in 1199 by Roman Mstyslavych, the prince of Volhynia from 1170, who united Galicia and Volhynia under his rule". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "The disintegration of Ukrainian statehood and general decline – Ruina". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Ukraine, Orest Subtelny, page 152, 2000

- ^ "Ukraine remembers famine horror Archived 31 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 24 November 2007.

- ^ France Meslè et Jacques Vallin avec des contributions de Vladimir Shkolnikov, Serhii Pyrozhkov et Serguei Adamets, Mortalite et cause de dècès en Ukraine au XX siècle Archived 13 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine p.28, see also France Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques Vallin France-Ukraine: Demographic Twins Separated by History Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Population and societies, N°413, juin 2005

- ^ Jacques Vallin, France Mesle, Serguei Adamets, Serhii Pyrozhkov, A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s Archived 23 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Population Studies, Vol. 56, No. 3. (November 2002), pp. 249–264

- ^ Kulchytsky, Stanislav (23–29 November 2002). Сколько нас погибло от Голодомора 1933 года? [How many of us died from Holodomor in 1933?]. Zerkalo Nedeli (in Russian). Archived from the original on 28 November 2006.

Kulchytsky, Stanislav (23–29 November 2002). Скільки нас загинуло під Голодомору 1933 року? [How many of us died during the Holodomor 1933?]. Zerkalo Nedeli (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 1 February 2003. - ^ Rosefielde, Steven. "Excess Mortality in the Soviet Union: A Reconsideration of the Demographic Consequences of Forced Industrialization, 1929–1949." Soviet Studies 35 (July 1983): 385–409

- ^ Peter Finn, Aftermath of a Soviet Famine Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, 27 April 2008, "There are no exact figures on how many died. Modern historians place the number between 2.5 million and 3.5 million. Yushchenko and others have said at least 10 million were killed."

- ^ "Ukrainian National Republic". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 1993. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Famine-Genocide of 1932–3 (Голодомор; Holodomor)". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 7 August 1932. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Development of modern Ukrainian national consciousness". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Олександр Lytvynenko, Oleksandr; Yakymenko, Yuriy (19 May 2008). "Russian-Speaking Citizens of Ukraine: "Imaginary Society" as it is". Razumkov Centre. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Viewed from a historical perspective, Ukrainians are people whose native language is Ukrainian". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Ukrainian nationality on the Western European model (e.g., by Vyacheslav Lypynsky) were unsuccessful until the 1990s". Encyclopediaofukraine.com. 16 July 1990. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ "Ethnic Self-Identification in Ukraine". Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2012 – via Find Articles.

- ^ Paulsen, Martin (2011). "Digital Determinism: the Cyrillic Alphabet in the Age of New Technology". Russian Language Journal / Русский язык. 61. American Councils for International Education: 119–141. JSTOR 43669201.

- ^ a b Pugh, Stefan A. (June 1985). "The Ruthenian Language of Meletij Smotryc'kyj: Phonology". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 9 (1/2). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 53–60. JSTOR 41036132.

- ^ Sériot, Patrick (2017–2018). "Language Policy as a Political Linguistics: The Implicit Model of Linguistics in the Discussion of the Norms of Ukrainian and Belarusian in the 1930s". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (1/4). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 169–185. JSTOR 44983540.

- ^ Kornienko, Anna (12 June 2020). "Masked lexical priming between close and distant languages" (PDF). University of Bergen. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Pavlenko, Aneta (2011). "Linguistic russification in the Russian Empire: peasants into Russians? / Языковая руссификация в Российской империи: стали ли крестьяне русскими?". Russian Linguistics. 35 (3). Springer Nature: 331–350. doi:10.1007/s11185-011-9078-7. JSTOR 41486701.

- ^ Shapoval, Yuri; Olynyk, Marta D. (2017–2018). "The Ukrainian Language under Totalitarianism and Total War". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 35 (1/4). Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute: 187–212. JSTOR 44983541.

- ^ Pavlenko, Aneta (January 1979). "West Ukraine and West Belorussia: Historical Tradition, Social Communication, and Linguistic Assimilation". Soviet Studies. 31 (1). Taylor & Francis: 76–98. doi:10.1080/09668137908411225. JSTOR 150187.

- ^ "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "Orthodox Christianity in the 21st Century". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 November 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ Adrian Ivakhiv. In Search of Deeper Identities: Neopaganism and Native Faith in Contemporary Ukraine Archived 14 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Nova Religio, 2005.

- ^ Центр, Разумков. "Конфесійна та церковна належність громадян України (січень 2020р. соціологія)". razumkov.org.ua. Archived from the original on 31 July 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b Релігія, Церква, суспільство і держава: два роки після Майдану [Religion, Church, Society and State: Two Years after Maidan] (PDF) (in Ukrainian), Kyiv: Razumkov Center in collaboration with the All-Ukrainian Council of Churches, 26 May 2016, pp. 22, 27, 29, 31, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2017, retrieved 28 April 2017

- ^ Yarmak, Andriy; Svyatkivska, Elizaveta; Prikhodko, Dmitry. "Ukraine: Meat sector review". Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Kaminski, Anna (10 March 2011). "Ukraine's culinary heights". BBC News. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Hercules, Olia (6 September 2016). "A 'nuclear' pickle recipe from Ukraine". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Shylova, Liudmyla (28 February 2024). "Nizhyn Pickles". Voice of America (VOA). Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Kollegaeva, Katrina (2017). "Salo, the Ukrainian Pork Fat". Gastronomica. 17 (4). University of California Press: 102–110. doi:10.1525/gfc.2017.17.4.102. JSTOR 26362486.

- ^ a b c d Hercules, Olia (4 June 2015). "Fermented herbs, a lavish hazelnut cake recipe and a Ukrainian spin on meatball soup". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b Banas, Anne (24 February 2023). "Five comfort foods that define Ukraine". BBC News. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Wroe, Ann (14 April 2022). "Bread in Ukraine: why a loaf means life". The Economist. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Ukraine has a glorious cuisine that is all its own". The Economist. 5 March 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Hercules, Olia (13 April 2017). "Alternatives to Good Friday bakes: a recipe for Ukrainian Easter bread". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ a b Drennan, Patrick (22 December 2023). "Christmas in Ukraine". The Hill. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Aidarbekova, Sabina; Aider, Mohammad (April 2022). "Production of Ryazhenka, a traditional Ukrainian fermented baked milk, by using electro-activated whey as supplementing ingredient and source of lactulose". Food Bioscience. 46 (101526). Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101526. ISSN 2212-4292.

- ^ a b Samokhvalov, Andriy V.; Pidkorytov, Valerii S.; Linskiy, Igor V.; Minko, Oleksandr I.; Minko, Oleksii O.; Rehm, Jürgen; Popova, Svetlana (1 January 2009). "Alcohol use and addiction services in Ukraine". International Psychiatry. 6 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1192/S1749367600000205. PMC 6734863. PMID 31507969.

- ^ "Ukrainians are drinking less alcohol and support stronger regulations, new survey finds". World Health Organization (WHO). 22 March 2024. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

Ukraine has seen a fall in alcohol consumption of almost 25% over the last decade.

- ^ "Ukrainian Music Elements". Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. 2001. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Ukrainian Wandering Bards: Kobzars, Bandurysts, and Lirnyks". Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. 2001. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

The artistic tradition of Ukrainian wandering bards, the kobzars (kobza players), bandurysts (bandura players), and lirnyks (lira players) is one of the most distinctive elements of Ukraine's cultural heritage.

- ^ "Ukraine is the rarely acknowledged musical heartland of the former Russian Empire". National Geographic Society. 2012. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011.

- ^ "Government portal- State symbols of Ukraine". Kmu.gov.ua. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Whitney Smith. "Flag of Ukraine". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ^ "Flag of Ukraine". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007.

- ^ Weeks, Andrew (29 December 2012). "Ukraine – History of the Flag". Crwflags.com. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Galician–Volhynian Chronicle (c. 1292)

- Perfecky, George A. (1973). The Hypatian Codex Part Two: The Galician–Volynian Chronicle. An annotated translation by George A. Perfecky. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag. OCLC 902306.

- Makhnovets, Leonid (1989). Літопис Руський за Іпатським списком [Rus' Chronicle according to the Hypatian Codex] (in Ukrainian). Kyiv: Dnipro. p. 591. ISBN 5-308-00052-2. Retrieved 18 July 2024. — A modern annotated Ukrainian translation of the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle based on the Hypatian Codex with comments from the Khlebnikov Codex.

Literature

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09309-4.

- Wilson, Andrew (2002). The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation (2nd ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09309-4.

Further reading

- Vasyl Balushok, "How Rusyns Became Ukrainians", Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), July 2005. Available in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Vasyl Balushok, "When was the Ukrainian nation born?", Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), 23 April – 6 May 2005. Available in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Dmytro Kyianskyi, "We are more "Russian" then they are: history without myths and sensationalism", Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), 27 January – 2 February 2001. Available in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Oleg Chirkov, "External migration – the main reason for the presence of a non-Ukrainian ethnic population in contemporary Ukraine". Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), 26 January – 1 February 2002. Available in Russian and in Ukrainian.

- Halyna Lozko, "Ukrainian ethnology. Ethnographic division of Ukraine" Available in Ukrainian Archived 7 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

- Ukrainian World Congress.

- Ukrainian diaspora in Canada and the U.S. Archived 9 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Ukrainians at Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- Races of Europe 1942–1943

- Hammond's Racial map of Europe, 1919 "National Alumni" 1920, vol.7

- Peoples of Europe / Die Voelker Europas 1914 (in German)

- Ethno-Linguistic Map of Europe Before 1914

- Linguistic Divisions of Europe in 1914 (in German)

- Illuminating Ukrainian Anthropology: Typical Physical Traits of Ukrainians (in English) June, 2023