Austroasiatic languages: Difference between revisions

Rescuing orphaned refs ("Vovin2014" from Japonic languages) |

included linguistic and genetic research about austroasiatic |

||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

This is identical to earlier reconstructions except for {{IPA|*ʄ}}. {{IPA|*ʄ}} is better preserved in the [[Katuic languages]], which Sidwell has specialized in. Sidwell (2011) suggests that the likely homeland of Austroasiatic is the middle [[Mekong]], in the area of the Bahnaric and Katuic languages (approximately where modern Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia come together), and that the family is not as old as frequently assumed, dating to perhaps 2000 BCE.<ref name="SidwellBlench2011" /> |

This is identical to earlier reconstructions except for {{IPA|*ʄ}}. {{IPA|*ʄ}} is better preserved in the [[Katuic languages]], which Sidwell has specialized in. Sidwell (2011) suggests that the likely homeland of Austroasiatic is the middle [[Mekong]], in the area of the Bahnaric and Katuic languages (approximately where modern Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia come together), and that the family is not as old as frequently assumed, dating to perhaps 2000 BCE.<ref name="SidwellBlench2011" /> A Genetic and linguistic researcg about Austroasiatic support an origin and homeland in today [[South China]]. These early Austroasiatic people got later in influence of arriving [[Daic]] people and finally assimilated by invading [[Han Chinese]], creating the today Southern Han.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283080042_Y-chromosome_diversity_suggests_southern_origin_and_Paleolithic_backwave_migration_of_Austro-_Asiatic_speakers_from_eastern_Asia_to_the_Indian_subcontinent_OPEN|title=Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro- Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent OPEN|last=Zhang|first=Xiaoming|last2=Liao|first2=Shiyu|last3=Qi|first3=Xuebin|last4=Liu|first4=Jiewei|last5=Kampuansai|first5=Jatupol|last6=Zhang|first6=Hui|last7=Yang|first7=Zhaohui|last8=Serey|first8=Bun|last9=Tuot|first9=Sovannary|date=2015-10-20|volume=5}}</ref> |

||

== Internal classification == |

== Internal classification == |

||

Revision as of 13:28, 20 February 2018

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2008) |

| Austroasiatic languages | |

|---|---|

| Mon–Khmer | |

| Geographic distribution | South and Southeast Asia |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Mon–Khmer |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | aav |

| Glottolog | aust1305 |

Austroasiatic languages | |

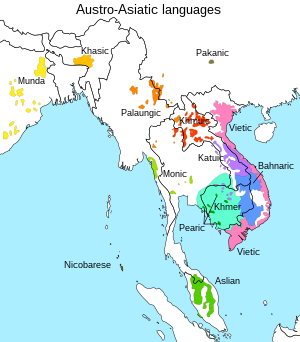

The Austroasiatic languages,[note 1] in recent classifications synonymous with Mon–Khmer,[1] are a large language family of Mainland Southeast Asia, also scattered throughout India, Bangladesh, Nepal and the southern border of China, with around 117 million speakers.[2] The name Austroasiatic comes from the Latin words for "South" and "Asia", hence "South Asia". Of these languages, only Vietnamese, Khmer, and Mon have a long-established recorded history, and only Vietnamese and Khmer have official status as modern national languages (in Vietnam and Cambodia, respectively). In Myanmar, the Wa language is the de facto official language of Wa State. The rest of the languages are spoken by minority groups and have no official status.

Ethnologue identifies 168 Austroasiatic languages. These form thirteen established families (plus perhaps Shompen, which is poorly attested, as a fourteenth), which have traditionally been grouped into two, as Mon–Khmer and Munda. However, one recent classification posits three groups (Munda, Nuclear Mon-Khmer and Khasi–Khmuic)[3] while another has abandoned Mon–Khmer as a taxon altogether, making it synonymous with the larger family.[4]

Austroasiatic languages have a disjunct distribution across India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Southeast Asia, separated by regions where other languages are spoken. They appear to be the extant autochthonous languages of Southeast Asia (if Andaman islands are not included), with the neighboring Indo-Aryan, Tai–Kadai, Dravidian, Austronesian, and Sino-Tibetan languages being the result of later migrations.[5]

A 2015 made analysis using the Automated Similarity Judgment Program resulted in that Japanese is being grouped with the Ainu and the Austroasiatic languages.[6]

Typology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

Regarding word structure, Austroasiatic languages are well known for having an iambic "sesquisyllabic" pattern, with basic nouns and verbs consisting of an initial, unstressed, reduced minor syllable followed by a stressed, full syllable.[7] This reduction of presyllables has led to a variety among modern languages of phonological shapes of the same original Proto-Austroasiatic prefixes, such as the causative prefix, ranging from CVC syllables to consonant clusters to single consonants.[8] As for word formation, most Austroasiatic languages have a variety of derivational prefixes, many have infixes, but suffixes are almost completely non-existent in most branches except Munda, and a few specialized exceptions in other Austroasiatic branches.[9] The Austroasiatic languages are further characterized as having unusually large vowel inventories and employing some sort of register contrast, either between modal (normal) voice and breathy (lax) voice or between modal voice and creaky voice.[10] Languages in the Pearic branch and some in the Vietic branch can have a three- or even four-way voicing contrast. However, some Austroasiatic languages have lost the register contrast by evolving more diphthongs or in a few cases, such as Vietnamese, tonogenesis. Vietnamese has been so heavily influenced by Chinese that its original Austroasiatic phonological quality is obscured and now resembles that of South Chinese languages, whereas Khmer, which had more influence from Sanskrit, has retained a more typically Austroasiatic structure.

Proto-language

Much work has been done on the reconstruction of Proto-Mon–Khmer in Harry L. Shorto's Mon–Khmer Comparative Dictionary. Little work has been done on the Munda languages, which are not well documented. With their demotion from a primary branch, Proto-Mon–Khmer becomes synonymous with Proto-Austroasiatic.

Paul Sidwell (2005) reconstructs the consonant inventory of Proto-Mon–Khmer as follows:

| *p | *t | *c | *k | *ʔ |

| *b | *d | *ɟ | *ɡ | |

| *ɓ | *ɗ | *ʄ | ||

| *m | *n | *ɲ | *ŋ | |

| *w | *l, *r | *j | ||

| *s | *h |

This is identical to earlier reconstructions except for *ʄ. *ʄ is better preserved in the Katuic languages, which Sidwell has specialized in. Sidwell (2011) suggests that the likely homeland of Austroasiatic is the middle Mekong, in the area of the Bahnaric and Katuic languages (approximately where modern Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia come together), and that the family is not as old as frequently assumed, dating to perhaps 2000 BCE.[5] A Genetic and linguistic researcg about Austroasiatic support an origin and homeland in today South China. These early Austroasiatic people got later in influence of arriving Daic people and finally assimilated by invading Han Chinese, creating the today Southern Han.[11]

Internal classification

Linguists traditionally recognize two primary divisions of Austroasiatic: the Mon–Khmer languages of Southeast Asia, Northeast India and the Nicobar Islands, and the Munda languages of East and Central India and parts of Bangladesh, parts of Nepal. However, no evidence for this classification has ever been published.

Each of the families that is written in boldface type below is accepted as a valid clade.[clarification needed] By contrast, the relationships between these families within Austroasiatic are debated. In addition to the traditional classification, two recent proposals are given, neither of which accepts traditional "Mon–Khmer" as a valid unit. However, little of the data used for competing classifications has ever been published, and therefore cannot be evaluated by peer review.

In addition, there are suggestions that additional branches of Austroasiatic might be preserved in substrata of Acehnese in Sumatra (Diffloth), the Chamic languages of Vietnam, and the Land Dayak languages of Borneo (Adelaar 1995).[12]

Diffloth (1974)

Diffloth's widely cited original classification, now abandoned by Diffloth himself, is used in Encyclopædia Britannica and—except for the breakup of Southern Mon–Khmer—in Ethnologue.

- Munda

- North Munda

- Korku

- Kherwarian

- South Munda

- Kharia–Juang

- Koraput Munda

- North Munda

- Mon–Khmer

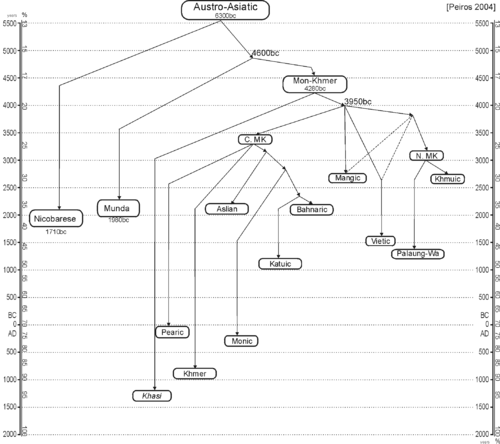

Ilia Peiros (2004)

Peiros is a lexicostatistic classification, based on percentages of shared vocabulary. This means that languages can appear to be more distantly related than they actually are due to language contact. Indeed, when Sidwell (2009a) replicated Peiros's study with languages known well enough to account for loans, he did not find the internal (branching) structure below.

- Nicobarese

- Munda–Khmer

Gérard Diffloth (2005)

Diffloth compares reconstructions of various clades, and attempts to classify them based on shared innovations, though like other classifications the evidence has not been published. As a schematic, we have:

| Austro ‑ Asiatic | |

Or in more detail,

- Munda languages (India)

- Koraput: 7 languages

- Core Munda languages

- Kharian–Juang: 2 languages

- North Munda languages

- Korku

- Kherwarian: 12 languages

- Khasi–Khmuic languages (Northern Mon–Khmer)

- Khasian: 3 languages of north eastern India and adjacent region of Bangladesh

- Palaungo-Khmuic languages

- Khmuic: 13 languages of Laos and Thailand

- Nuclear Mon–Khmer languages

- Khmero-Vietic languages (Eastern Mon–Khmer)

- Vieto-Katuic languages ?[13]

- Vietic: 10 languages of Vietnam and Laos, including the Vietnamese language, which has the most speakers of any Austroasiatic language.

- Katuic: 19 languages of Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand.

- Nico-Monic languages (Southern Mon–Khmer)

- Nicobarese: 6 languages of the Nicobar Islands, a territory of India.

- Asli-Monic languages

- Aslian: 19 languages of peninsular Malaysia and Thailand.

- Monic: 2 languages, the Mon language of Burma and the Nyahkur language of Thailand.

This family tree is consistent with recent studies of migration of Y-Chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95. However, the dates obtained from by Zhivotovsky method DNA studies are several times older than that given by linguists.[14] The route map of the people with haplogroup O2a1-M95, speaking this language can be seen in this link.[15] Other geneticists criticise the Zhivotovsky method.

Previously existent branches

Roger Blench (2009)[16] also proposes that there might have been other primary branches of Austroasiatic that are now extinct, based on substrate evidence in modern-day languages.

- Pre-Chamic languages (the languages of coastal Vietnam prior to the Chamic migrations). Chamic has various Austroasiatic loanwords that cannot be clearly traced to existing Austroasiatic branches (Sidwell 2006).[17]

- Acehnese substratum (Sidwell 2006).[17] Acehnese has many basic words that are of Austroasiatic origin, suggesting that either Austronesian speakers have absorbed earlier Austroasiatic residents in northern Sumatra, or that words might have been borrowed from Austroasiatic languages in southern Vietnam – or perhaps a combination of both. Sidwell (2006) argues that Acehnese and Chamic had often borrowed Austroasiatic words independently of each other, while some Austroasiatic words can be traced back to Proto-Aceh-Chamic. Sidwell (2006) accepts that Acehnese and Chamic are related, but that they had separated from each other before Chamic had borrowed most of its Austroasiatic lexicon.

- Bornean substrate languages (Blench 2010).[18] Blench cites Austroasiatic-origin words in modern-day Bornean branches such as Land Dayak (Bidayuh, Dayak Bakatiq, etc.), Dusunic (Central Dusun, Visayan, etc.), Kayan, and Kenyah, noting especially resemblances with Aslian. As further evidence for his proposal, Blench also cites ethnographic evidence such as musical instruments in Borneo shared in common with Austroasiatic-speaking groups in mainland Southeast Asia.

- Lepcha substratum ("Rongic").[19] Many words of Austroasiatic origin have been noticed in Lepcha, suggesting a Sino-Tibetan superstrate laid over an Austroasiatic substrate. Blench (2013) calls this branch "Rongic" based on the Lepcha autonym Róng.

Other languages with proposed Austroasiatic substrata are:

- Jiamao, based on evidence from the register system of Jiamao, a Hlai language (Thurgood 1992).[20] Jiamao is known for its highly aberrant vocabulary.

- Kerinci: Van Reijn (1974)[21] notes that Kerinci, a Malayic language of central Sumatra, shares many phonological similarities with Austroasiatic languages, such as sesquisyllabic word structure and vowel inventory.

John Peterson (2017)[22] suggests that "pre-Munda" languages may have once dominated the eastern Indo-Gangetic Plain, and were then absorbed by Indo-Aryan languages at an early date as Indo-Aryan spread east. Peterson notes that eastern Indo-Aryan languages display many morphosyntactic features similar to those of Munda languages, while western Indo-Aryan languages do not.

Sidwell (2009, 2011)

Paul Sidwell (2009a), in a lexicostatistical comparison of 36 languages which are well-known enough to exclude loan words, finds little evidence for internal branching, though he did find an area of increased contact between the Bahnaric and Katuic languages, such that languages of all branches apart from the geographically distant Munda and Nicobarese show greater similarity to Bahnaric and Katuic the closer they are to those branches, without any noticeable innovations common to Bahnaric and Katuic. He therefore takes the conservative view that the thirteen branches of Austroasiatic should be treated as equidistant on current evidence. Sidwell & Blench (2011) discuss this proposal in more detail, and note that there is good evidence for a Khasi–Palaungic node, which could also possibly be closely related to Khmuic.[5] If this would the case, Sidwell & Blench suggest that Khasic may have been an early offshoot of Palaungic that had spread westward. Sidwell & Blench (2011) suggest Shompen as an additional branch, and believe that a Vieto-Katuic connection is worth investigating. In general, however, the family is thought to have diversified too quickly for a deeply nested structure to have developed, since Proto-Austroasiatic speakers are believed by Sidwell to have radiated out from the central Mekong river valley relatively quickly.

Austroasiatic: Mon–Khmer

|

|

Blench (2017)[23] suggests that vocabulary related to aquatic subsistence strategies (such as boats, waterways, river fauna, and fish capture techniques), can be reconstructed for Proto-Austroasiatic. As archaeological evidence for the presence of agriculture in northern Indochina dates back to only about 4,000 years B.P. (2,000 B.C.), this would point to a relatively late dispersal of Austroasiatic as compared to Sino-Tibetan. In addition to living an aquatic-based lifestyle, early Austroasiatic speakers would have also had access to livestock, crops, and newer types of watercraft. As early Austroasiatic speakers dispersed rapidly via waterways, they would have encountered speakers of older language families who were already settled in the area, such as Sino-Tibetan.

Writing systems

Other than Latin-based alphabets, many Austroasiatic languages are written with the ancient Khmer alphabet, Thai alphabet and Lao alphabet. Vietnamese divergently had an indigenous script based on Chinese logographic writing. This has since been supplanted by the Latin alphabet in the 20th century. The following are examples of past-used alphabets or current alphabets of Austroasiatic languages.

- Chữ Nôm[24]

- Khmer alphabet[25]

- Warang Citi (Ho alphabet)[26]

- Mon script

- Ol Chiki alphabet (Santali alphabet)[27]

- Sorang Sompeng alphabet (Sora alphabet)[28]

- Khom script (used for a short period in the early 20th century for indigenous languages in Laos)

Austroasiatic migrations

According to Chaubey et al., "Austro-Asiatic speakers in India today are derived from dispersal from Southeast Asia, followed by extensive sex-specific admixture with local Indian populations."[29][note 2] According to Riccio et al. (2011), the Munda people are likely descended from Austroasiatic migrants from southeast Asia.[30][31] According to Zhang et al. (2015), Austroasiatic migrations from southeast Asia into India took place after the last Glacial maximum, circa 10,000 years ago.[32] Arunkumar et al. (2015) suggest Austroasiatic migrations from southeast Asia occurred into northeast India 5.2 ± 0.6 kya and into East India 4.3 ± 0.2 kya.[33]

The Yayoi people(early Japanese) may have spoken an Austroasiatic language or Tai-Kadai language, based on the reconstructed Japonic terms *(z/h)ina-Ci 'rice (plant)', *koma-Ci '(hulled) rice', and *pwo 'ear of grain' which Vovin assumes to be agricultural terms of Yayoi origin. Vovin suggests that Japonic was in contact with Austronesian, before the migration from Southern China to Japan, pointing to an ultimate origin of Japonic in southern China.[34][35]Although Vovin (2014)[36] does not consider Japonic to be genetically related to Tai-Kadai, he suggests that Japonic was later in contact with Tai-Kadai, pointing to an ultimate origin of Japonic in southern China with possible genetic relation to Austroasiatic.

There is typological evidence that Proto-Japonic may have been a monosyllabic, SVO syntax and isolating language; which are features that the Austroasiatic and Tai-Kadai languages also famously exhibit.[37]

A 2015 analysis using the Automated Similarity Judgment Program resulted in the Japonic languages being grouped with the Austroasiatic languages. The same analysis also showed a connection to Ainu langauges, but this is possibly because of heavy influence from Japonic to Ainu.[38]

See also

Notes

- ^ Sometimes also as Austro-Asiatic or Austroasian

- ^ See also:

* Dienekes Anthropology Blog, Origin of Indian Austroasiatic speakers

* Razib Khan (2010), Sons of the conquerors: the story of India?

* Razib Khan (2013), Phylogenetics implies Austro-Asiatic are intrusive to India

References

- ^ Bradley (2012) notes, MK in the wider sense including the Munda languages of eastern South Asia is also known as Austroasiatic.

- ^ "Austroasiatic". www.languagesgulper.com. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Diffloth 2005

- ^ Sidwell 2009

- ^ a b c Sidwell, Paul, and Roger Blench. 2011. "The Austroasiatic Urheimat: the Southeastern Riverine Hypothesis." Enfield, NJ (ed.) Dynamics of Human Diversity, 317–345. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. http://rogerblench.info/Archaeology/SE%20Asia/SR09/Sidwell%20Blench%20offprint.pdf

- ^ Gerhard Jäger, "Support for linguistic macrofamilies from weighted sequence alignment." PNAS vol. 112 no. 41, 12752–12757, doi:10.1073/pnas.1500331112. Published online before print 24 September 2015.

- ^ Alves 2014:524

- ^ Alves 2014:526

- ^ Alves 2014, 2015

- ^ DIPFLOTH, Gerard. "Proto-Austroasiatic creaky voice." (1989).

- ^ Zhang, Xiaoming; Liao, Shiyu; Qi, Xuebin; Liu, Jiewei; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Zhang, Hui; Yang, Zhaohui; Serey, Bun; Tuot, Sovannary (20 October 2015). Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro- Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent OPEN. Vol. 5.

- ^ Roger Blench, 2009. Are there four additional unrecognised branches of Austroasiatic? Presentation at ICAAL-4, Bangkok, 29–30 October. Summarized in Sidwell and Blench (2011).

- ^ a b Sidwell (2005) casts doubt on Diffloth's Vieto-Katuic hypothesis, saying that the evidence is ambiguous, and that it is not clear where Katuic belongs in the family.

- ^ Kumar, Vikrant; et al. (2007). "Y-chromosome evidence suggests a common paternal heritage of Austroasiatic populations". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-47.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Figure". www.biomedcentral.com. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-47. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Blench, Roger. 2009. "Are there four additional unrecognised branches of Austroasiatic?."

- ^ a b Sidwell, Paul. 2006. "Dating the Separation of Acehnese and Chamic By Etymological Analysis of the Aceh-Chamic Lexicon Archived 5 June 2013 at WebCite." In The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal, 36: 187–206.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2010. "Was there an Austroasiatic Presence in Island Southeast Asia prior to the Austronesian Expansion?" In Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, Vol. 30.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2013. Rongic: a vanished branch of Austroasiatic. m.s.

- ^ Thurgood, Graham. 1992. "The aberrancy of the Jiamao dialect of Hlai: speculation on its origins and history". In Ratliff, Martha S. and Schiller, E. (eds.), Papers from the First Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 417–433. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- ^ Van Reijn, E.O. (1974). "Some Remarks on the Dialects of North Kerintji: A link with Mon-Khmer Languages." Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 31, 2: 130–138. JSTOR 41492089.

- ^ Peterson, John. 2017. The prehistorical spread of Austro-Asiatic in South Asia. Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.

- ^ Blench, Roger. 2017. Waterworld: lexical evidence for aquatic subsistence strategies in Austroasiatic. Presented at ICAAL 7, Kiel, Germany.

- ^ "Vietnamese Chu Nom script". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ "Khmer/Cambodian alphabet, pronunciation and language". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Everson, Michael (19 April 2012). "N4259: Final proposal for encoding the Warang Citi script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ "Santali alphabet, pronunciation and language". Omniglot.com. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ "Sorang Sompeng script". Omniglot.com. 18 June 1936. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ^ Chaubey et al. 2010, p. 1013.

- ^ Riccio et al. (2011), The Austroasiatic Munda population from India and Its enigmatic origin: a HLA diversity study.

- ^ The Language Gulper, Austroasiatic Languages

- ^ Zhang 2015.

- ^ Arunkumar; et al. (2015). "A late Neolithic expansion of Y chromosomal haplogroup O2a1-M95 from east to west". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 53 (6): 546–560. doi:10.1111/jse.12147.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Vovin, Alexander. 1998. Japanese rice agriculture terminology and linguistic affiliation of Yayoi culture. In Archaeology and Language II: Archaeological Data and Linguistic Hypotheses. Routledge.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander. 2014. "Out of Southern China? – Philological and linguistic musings on the possible Urheimat of Proto-Japonic". Journées de CRLAO 2014. June 27–28, 2014. INALCO, Paris.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander. 2014. "Out of Southern China? – Philological and linguistic musings on the possible Urheimat of Proto-Japonic". Journées de CRLAO 2014. June 27–28, 2014. INALCO, Paris.

- ^ Vovin, Alexander. 2014. "Out of Southern China? – Philological and linguistic musings on the possible Urheimat of Proto-Japonic". Journées de CRLAO 2014. June 27–28, 2014. INALCO, Paris.

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4611657

Sources

- Adams, K. L. (1989). Systems of numeral classification in the Mon–Khmer, Nicobarese and Aslian subfamilies of Austroasiatic. Canberra, A.C.T., Australia: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0-85883-373-5

- Alves, Mark J. (2014). Mon-Khmer. In Rochelle Lieber and Pavel Stekauer (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Derivational Morphology, 520–544. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alves, Mark J. (2015). Morphological functions among Mon-Khmer languages: beyond the basics. In N. J. Enfield & Bernard Comrie (eds.), Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia: the state of the art. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, 531–557.

- Bradley, David (2012). "Languages and Language Families in China", in Rint Sybesma (ed.), Encyclopedia of Chinese Language and Linguistics.

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes. (1994). A Comparative Study of Santali and Bengali.

- Chaubey, G.; et al. (2010), "Population Genetic Structure in Indian Austroasiatic Speakers: The Role of Landscape Barriers and Sex-Specific Admixture", Mol Biol Evol, 28 (2): 1013–1024, doi:10.1093/molbev/msq288, PMC 3355372, PMID 20978040

- Diffloth, Gérard (2005). "The contribution of linguistic palaeontology and Austro-Asiatic". in Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench and Alicia Sanchez-Mazas, eds. The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. 77–80. London: Routledge Curzon. ISBN 0-415-32242-1

- Filbeck, D. (1978). T'in: a historical study. Pacific linguistics, no. 49. Canberra: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0-85883-172-4

- Hemeling, K. (1907). Die Nanking Kuanhua. (German language)

- Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages. Leiden: Brill.

- Peck, B. M., Comp. (1988). An Enumerative Bibliography of South Asian Language Dictionaries.

- Peiros, Ilia. 1998. Comparative Linguistics in Southeast Asia. Pacific Linguistics Series C, No. 142. Canberra: Australian National University.

- Shorto, Harry L. edited by Sidwell, Paul, Cooper, Doug and Bauer, Christian (2006). A Mon–Khmer comparative dictionary. Canberra: Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 0-85883-570-3

- Shorto, H. L. Bibliographies of Mon–Khmer and Tai Linguistics. London oriental bibliographies, v. 2. London: Oxford University Press, 1963.

- Sidwell, Paul (2005). "Proto-Katuic Phonology and the Sub-grouping of Mon–Khmer Languages". In Sidwell, ed., SEALSXV: papers from the 15th meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society.

- Sidwell, Paul (2009a). The Austroasiatic Central Riverine Hypothesis. Keynote address, SEALS, XIX.

- Sidwell, Paul (2009b). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.

- Zide, Norman H., and Milton E. Barker. (1966) Studies in Comparative Austroasiatic Linguistics, The Hague: Mouton (Indo-Iranian monographs, v. 5.).

- Zhang; et al. (2015), "Y-chromosome diversity suggests southern origin and Paleolithic backwave migration of Austro-Asiatic speakers from eastern Asia to the Indian subcontinent", Nature Scientific Reports, 5: 1548, Bibcode:2015NatSR...515486Z, doi:10.1038/srep15486, PMC 4611482, PMID 26482917

Further reading

- Mann, Noel, Wendy Smith and Eva Ujlakyova. 2009. Linguistic clusters of Mainland Southeast Asia: an overview of the language families. Chiang Mai: Payap University.

External links

- Swadesh lists for Austro-Asiatic languages (from Wiktionary's wikt:Appendix:Swadesh lists Swadesh-list appendix)

- Austro-Asiatic at the Linguist List MultiTree Project (not functional as of 2014): Genealogical trees attributed to Sebeok 1942, Pinnow 1959, Diffloth 2005, and Matisoff 2006

- Mon–Khmer.com: Lectures by Paul Sidwell

- Mon–Khmer Languages Project at SEAlang

- http://projekt.ht.lu.se/rwaai RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-66A4-2@view RWAAI Digital Archive