Myanmar: Difference between revisions

→Religion: added previously-cited references to make the percent Buddhist report internally consistent - these may not be the best references |

|||

| Line 546: | Line 546: | ||

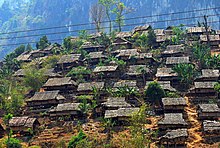

[[File:Shwekyin.jpg|thumb|In February 2012, 1000 Buddhist monks and followers gathered for the 18th annual [[Shwegyin Nikaya]] Conference at the compound of Dhammaduta Zetawon Tawya Monastery in [[Hmawbi Township]], [[Yangon Region]].]] |

[[File:Shwekyin.jpg|thumb|In February 2012, 1000 Buddhist monks and followers gathered for the 18th annual [[Shwegyin Nikaya]] Conference at the compound of Dhammaduta Zetawon Tawya Monastery in [[Hmawbi Township]], [[Yangon Region]].]] |

||

A large majority of the population practices Buddhism; estimates range from 80% <ref name=pew>[http://www.globalreligiousfutures.org/countries/burma-myanmar/religious_demography#/?affiliations_religion_id=0&affiliations_year=2010 Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project: Burma]. [[Pew Research Center]]. 2010.</ref> to 89% <ref name=Buddhanet>{{cite web | url = http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/burma-txt.htm | title = Buddhanet.net | accessdate =17 February 2011}}</ref>. [[Theravāda]] Buddhism is the most widespread <ref name=Buddhanet>{{cite web | url = http://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/burma-txt.htm | title = Buddhanet.net | accessdate =17 February 2011}}</ref>. Other religions are practiced largely without obstruction, with the notable exception of some ethnic minorities such as the Muslim Rohingya people, who have continued to have their citizenship status denied and treated as illegal immigrants instead,<ref name=rohingya/> and Christians in Chin State.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90131.htm |title=Burma-International Religious Freedom Report 2007 |publisher=U.S. Department of State}}</ref> 4% of the population practices Islam; 4% Christianity; 1% traditional [[animism|animistic]] beliefs; and 2% follow other religions, including [[Mahayana Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], and [[East Asian religions]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/bm.html#People |title=CIA Factbook – Burma |publisher=Cia.gov |accessdate=2012-11-20}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2007/90131.htm |title=International Religious Freedom Report 2007 – Burma |publisher=State.gov |accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/35910.htm |title=Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs – Background Note: Burma |publisher=State.gov |accessdate=17 April 2010}}</ref> However, according to a [[U.S. State Department]]'s 2010 international religious freedom report, official statistics are alleged to underestimate the non-Buddhist population. Independent researchers put the Muslim population at 6 to 10% of the population. A tiny Jewish community in Rangoon had a synagogue but no resident rabbi to conduct services.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2010/148859.htm |title=Burma—International Religious Freedom Report 2010 |publisher=U.S. Department of State |date=17 November 2010 |accessdate=22 February 2011}}</ref> |

|||

Although Hinduism is presently only practiced by 1% of the population, it was a major religion in Burma's past. Several strains of Hinduism existed alongside both Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism in the Mon and [[Pyu city-states|Pyu period]] in the first millennium CE,<ref name=mat-2005-31-34>Aung-Thwin 2005: 31–34</ref> and down to the [[Pagan Kingdom|Pagan period]] (9th to 13th centuries) when "[[Shaivism|Saivite]] and [[Vaishnavism|Vaishana]] elements enjoyed greater elite influence than they would later do."<ref name=vbl-2003-115-116>Lieberman 2003: 115–116</ref> |

Although Hinduism is presently only practiced by 1% of the population, it was a major religion in Burma's past. Several strains of Hinduism existed alongside both Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism in the Mon and [[Pyu city-states|Pyu period]] in the first millennium CE,<ref name=mat-2005-31-34>Aung-Thwin 2005: 31–34</ref> and down to the [[Pagan Kingdom|Pagan period]] (9th to 13th centuries) when "[[Shaivism|Saivite]] and [[Vaishnavism|Vaishana]] elements enjoyed greater elite influence than they would later do."<ref name=vbl-2003-115-116>Lieberman 2003: 115–116</ref> |

||

Revision as of 09:14, 15 September 2014

Template:Contains Burmese text

Republic of the Union of Myanmar ပြည်ထောင်စု သမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော် Pyidaunzu Thanmăda Myăma Nainngandaw | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

| |

| |

| Capital | Naypyidaw |

| Largest city | Yangon (Rangoon) |

| Official languages | Burmese |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Official scripts | Burmese script |

| Ethnic groups ([1]) | |

| Demonym(s) | Burmese / Myanma |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Thein Sein | |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Union |

| House of Nationalities | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

| 23 December 849 | |

| 16 October 1510 | |

| 29 February 1752 | |

• Independence (from United Kingdom) | 4 January 1948 |

| 2 March 1962 | |

| 30 March 2011 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 676,578 km2 (261,228 sq mi) (40th) |

• Water (%) | 3.06 |

| Population | |

• 2014 census | 51,419,420[2] (25th) |

• Density | 76/km2 (196.8/sq mi) (125th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $111.120 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $2,160[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2013 estimate |

• Total | $59.427 billion[3] |

• Per capita | $1,155[3] |

| HDI (2013) | low (150th) |

| Currency | Kyat (K) (MMK) |

| Time zone | UTC+06:30 (MST) |

| Drives on | rightb |

| Calling code | +95 |

| ISO 3166 code | MM |

| Internet TLD | .mm |

| |

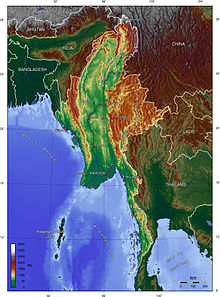

Burma (/ˈbɜːrmə/ BUR-mə), officially the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, commonly shortened to Myanmar (/ˈmjɑːnˌmɑːr/ MYAHN-mar,[5] /ˈmaɪænmɑːr/ or /ˈmjænmɑːr/),[6][7][8][9] is a sovereign state in Southeast Asia bordered by Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand. One third of Burma's total perimeter of 1,930 kilometres (1,200 miles) forms an uninterrupted coastline along the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea. Burma's population of over 50 million makes it the world's 25th most populous country[10] and, at 676,578 square kilometres (261,227 sq mi), it is the world's 40th largest country and the second largest in Southeast Asia. Its capital city is Naypyidaw and its largest city is Yangon.

Early civilizations in Burma included the Tibeto-Burman speaking Pyu in Upper Burma and the Mon in Lower Burma.[11] In the 9th century, the Burmans of the Kingdom of Nanzhao entered the upper Irrawaddy valley and, following the establishment of the Pagan Empire in the 1050s, the Burmese language and culture slowly became dominant in the country. During this period, Theravada Buddhism gradually became the predominant religion of the country. The Pagan Empire fell due to the Mongol invasions (1277–1301), and several warring states emerged. In the second half of the 16th century, reunified by the Taungoo Dynasty, the country was for a brief period the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia.[12] The early 19th century Konbaung Dynasty ruled over an area that included modern Burma and briefly controlled Manipur and Assam as well. The British conquered Burma after three Anglo-Burmese Wars in the 19th century and the country became a British colony (a part of India until 1937 and then a separately administered colony). Burma became an independent nation in 1948, initially as a democratic nation and then, following a coup in 1962, a military dictatorship which formally ended in 2011.

For most of its independent years, the country has been engrossed in rampant ethnic strife and a myriad of Burma's ethnic groups have been involved in one of the world's longest-running unresolved civil wars. During this time, the United Nations and several other organizations have reported consistent and systematic human rights violations in the country.[13][14][15] In 2011, the military junta was officially dissolved following a 2010 general election, and a nominally civilian government was installed. Although the military retains enormous influence through the constitution that was ratified in 2008, it has taken steps toward relinquishing control of the government. This, along with the release of Burma's most prominent human rights activist, Aung San Suu Kyi, and many other political prisoners, has improved the country's human rights record and foreign relations and has led to the easing of trade and other economic sanctions that had been imposed by the European Union and the United States.[16][17] There is, however, continuing criticism of the government's treatment of the Muslim ethnic Rohingya minority and its poor response to the religious clashes that have occurred throughout the nation, described by various human rights organizations as a policy of ethnic cleansing.[18][19][20][21]

Burma is a country rich in jade and gems, oil, natural gas and other mineral resources. In 2013, its GDP (nominal) stood at US$59.427 billion and its GDP (PPP) at US$111.120 billion.[3] Despite good economic growth, it is believed that Burma's economic potential won't be easily achieved due to the nation's lack of development. As of 2013, according to the Human Development Index (HDI), Burma had a low level of human development, ranking 150 out of 187 countries.[4]

Etymology

In 1989, the military government officially changed the English translations of many names dating back to Burma's colonial period or earlier, including that of the country itself: "Burma" became "Myanmar". The renaming remains a contested issue.[22] Many political and ethnic opposition groups and countries continue to use "Burma" because they do not recognise the legitimacy of the ruling military government or its authority to rename the country.[23]

The country's official full name is the "Republic of the Union of Myanmar" /ˈmjɑːnˌmɑːr/ [5] (ပြည်ထောင်စု သမ္မတ မြန်မာနိုင်ငံတော်, Pyidaunzu Thanmăda Myăma Nainngandaw, pronounced [pjìdàʊɴzṵ θàɴməda̰ mjəmà nàɪɴŋàɴdɔ̀]). Some countries, however, have not recognized this name and use the short form "Union of Burma" instead.[24][25]

In English, the country is popularly known by either of its short names "Burma" or "Myanmar". Both these names are derived from the name of the majority Burmese Bamar ethnic group. Myanmar is considered to be the literary form of the name of the group, while Burma is derived from "Bamar", the colloquial form of the group's name. Depending on the register used, the pronunciation would be Bama (pronounced [bəmà]) or Myamah (pronounced [mjəmà]). The name Burma has been in use in English since the 18th century.

Burma continues to be used in English by the governments of many countries, including the United Kingdom and Canada.[26] Official United States policy retains Burma as the country's name, although the State Department's website lists the country as "Burma (Myanmar)" and Barack Obama has referred to the country as Myanmar.[27][28][29] The United Nations uses Myanmar, as do the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Russia, Germany,[30] China, India, Norway,[31] and Japan.[26]

Most English-speaking international news media officially refer to the country by the name Myanmar, including the BBC,[32] CNN,[33] Al Jazeera,[34] Reuters,[35] and Russia Today.

There are also other variations. Burma is known as "Birmania" in Spanish, Italian and Romanian, as "Birmânia" in Portuguese, and as "Birmanie" in French.[36] The Government of Brazil uses "Mianmar".[37]

History

Prehistory

Archaeological evidence shows that Homo erectus lived in the region now known as Burma as early as 400,000 years ago.[38] The first evidence of Homo sapiens is dated to about 11,000 BC, in a Stone Age culture called the Anyathian with discoveries of stone tools in central Burma. Evidence of neolithic age domestication of plants and animals and the use of polished stone tools dating to sometime between 10,000 and 6,000 BC has been discovered in the form of cave paintings near the city of Taunggyi.[39] The Bronze Age arrived circa 1500 BC when people in the region were turning copper into bronze, growing rice and domesticating poultry and pigs; they were among the first people in the world to do so.[40] The Iron Age began around 500 BC with the emergence of iron-working settlements in an area south of present-day Mandalay.[41] Evidence also shows the presence of rice-growing settlements of large villages and small towns that traded with their surroundings as far as China between 500 BC and 200 AD.[42] Iron Age Burmese cultures also had influences from outside sources such as India and Thailand, as seen in their funerary practices concerning child burials. This indicates some form of communcation between groups in Burma and other places, possibly through trade.[43]

Around the 2nd century BC the first-known city-states emerged in central Burma. The city-states were founded as part of the southward migration by the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Pyu, the earliest inhabitants of Burma of whom records are extant, from present-day Yunnan.[44][45] The Pyu culture was heavily influenced by trade with India, importing Buddhism as well as other cultural, architectural and political concepts which would have an enduring influence on later Burmese culture and political organization.[46] By the 9th century AD several city-states had sprouted across the land: the Pyu states in the central dry zone, Mon states along the southern coastline and Arakanese states along the western littoral. The balance was upset when the Pyu states came under repeated attacks from the Kingdom of Nanzhao between the 750s and the 830s. In the mid-to-late 9th century the Mranma (Burmans/Bamar) of Nanzhao founded a small settlement at Pagan (Bagan). It was one of several competing city-states until the late 10th century when it grew in authority and grandeur.[47]

Imperial Burma

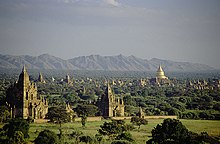

Pagan gradually grew to absorb its surrounding states until the 1050s–1060s when Anawrahta founded the Pagan Empire, the first ever unification of the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Pagan Empire and the Khmer Empire were two main powers in mainland Southeast Asia.[48] The Burmese language and culture gradually became dominant in the upper Irrawaddy valley, eclipsing the Pyu, Mon and Pali norms by the late 12th century. Theravada Buddhism slowly began to spread to the village level although Tantric, Mahayana, Brahmanic, and animist practices remained heavily entrenched. Pagan's rulers and wealthy built over 10,000 Buddhist temples in the Pagan capital zone alone. Repeated Mongol invasions (1277–1301) toppled the four-century-old kingdom in 1287.[49]

Pagan's collapse was followed by 250 years of political fragmentation that lasted well into the 16th century. Like the Burmans four centuries earlier, Shan migrants who arrived with the Mongol invasions stayed behind. Several competing Shan states came to dominate the entire northwestern to eastern arc surrounding the Irrawaddy valley. The valley too was beset with petty states until the late 14th century when two sizable powers, Ava Kingdom and Hanthawaddy Kingdom, emerged. In the west, a politically fragmented Arakan was under competing influences of its stronger neighbors until the Kingdom of Mrauk U unified the Arakan coastline for the first time in 1437.

Early on, Ava fought wars of unification (1385–1424) but could never quite reassemble the lost empire. Having held off Ava, Hanthawaddy entered its golden age, and Arakan went on to become a power in its own right for the next 350 years. In contrast, constant warfare left Ava greatly weakened, and it slowly disintegrated from 1481 onward. In 1527, the Confederation of Shan States conquered Ava itself, and ruled Upper Burma until 1555.

Like the Pagan Empire, Ava, Hanthawaddy and the Shan states were all multi-ethnic polities. Despite the wars, cultural synchronization continued. This period is considered a golden age for Burmese culture. Burmese literature "grew more confident, popular, and stylistically diverse", and the second generation of Burmese law codes as well as the earliest pan-Burma chronicles emerged.[50] Hanthawaddy monarchs introduced religious reforms that later spread to the rest of the country.[51] Many splendid temples of Mrauk U were built during this period.

Political unification returned in the mid-16th century, due to the efforts of one tiny Toungoo (Taungoo), a former vassal state of Ava. Toungoo's young, ambitious king Tabinshwehti defeated the more powerful Hanthawaddy in 1541. His successor Bayinnaung went on to conquer a vast swath of mainland Southeast Asia including the Shan states, Lan Na, Manipur, the Chinese Shan states, Siam, Lan Xang and southern Arakan. However, the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia unravelled soon after Bayinnaung's death in 1581, completely collapsing by 1599. Siam seized Tenasserim and Lan Na, and Portuguese mercenaries established Portuguese rule at Syriam (Thanlyin).

The dynasty regrouped and defeated the Portuguese in 1613 and Siam in 1614. It restored a smaller, more manageable kingdom, encompassing Lower Burma, Upper Burma, Shan states, Lan Na and upper Tenasserim. The Restored Toungoo kings created a legal and political framework whose basic features would continue well into the 19th century. The crown completely replaced the hereditary chieftainships with appointed governorships in the entire Irrawaddy valley, and greatly reduced the hereditary rights of Shan chiefs. Its trade and secular administrative reforms built a prosperous economy for more than 80 years. From the 1720s onward, the kingdom was beset with repeated Manipuri raids into Upper Burma, and a nagging rebellion in Lan Na. In 1740, the Mon of Lower Burma founded the Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom. Hanthawaddy forces sacked Ava in 1752, ending the 266-year-old Toungoo Dynasty.

After the fall of Ava, one resistance group, Alaungpaya's Konbaung Dynasty defeated Restored Hanthawaddy, and by 1759, had reunited all of Burma (and Manipur), and driven out the French and the British who had provided arms to Hanthawaddy. By 1770, Alaungpaya's heirs had subdued much of Laos (1765), defeated Siam (1767), and defeated four invasions by China (1765–1769).[52] With Burma preoccupied by the Chinese threat, Siam recovered its territories by 1770, and went on to capture Lan Na by 1776. Burma and Siam went to war until 1855, but all resulted in a stalemate, exchanging Tenasserim (to Burma) and Lan Na (to Siam). Faced with a powerful China and a resurgent Siam in the east, King Bodawpaya turned west, acquiring Arakan (1785), Manipur (1814) and Assam (1817). It was the second largest empire in Burmese history but also one with a long ill-defined border with British India.[53]

The breadth of this empire was short lived. Burma lost Arakan, Manipur, Assam and Tenasserim to the British in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826). In 1852, the British easily seized Lower Burma in the Second Anglo-Burmese War. King Mindon tried to modernize the kingdom, and in 1875 narrowly avoided annexation by ceding the Karenni States. The British, alarmed by the consolidation of French Indo-China, annexed the remainder of the country in the Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885.

Konbaung kings extended Restored Toungoo's administrative reforms, and achieved unprecedented levels of internal control and external expansion. For the first time in history, the Burmese language and culture came to predominate the entire Irrawaddy valley. The evolution and growth of Burmese literature and theater continued, aided by an extremely high adult male literacy rate for the era (half of all males and 5% of females).[54] Nonetheless, the extent and pace of reforms were uneven and ultimately proved insufficient to stem the advance of British colonialism.

British Burma

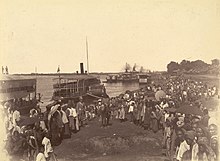

The country was colonized by Britain following three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824–1885). British rule brought social, economic, cultural and administrative changes.

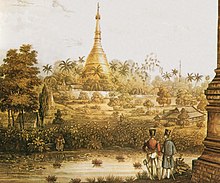

With the fall of Mandalay, all of Burma came under British rule, being annexed on 1 January 1886. Throughout the colonial era, many Indians arrived as soldiers, civil servants, construction workers and traders and, along with the Anglo-Burmese community, dominated commercial and civil life in Burma. Rangoon became the capital of British Burma and an important port between Calcutta and Singapore.

Burmese resentment was strong and was vented in violent riots that paralysed Yangon (Rangoon) on occasion all the way until the 1930s.[55] Some of the discontent was caused by a disrespect for Burmese culture and traditions such as the British refusal to remove shoes when they entered pagodas. Buddhist monks became the vanguards of the independence movement. U Wisara, an activist monk, died in prison after a 166-day hunger strike to protest a rule that forbade him from wearing his Buddhist robes while imprisoned.[56]

On 1 April 1937, Burma became a separately administered colony of Great Britain and Ba Maw the first Prime Minister and Premier of Burma. Ba Maw was an outspoken advocate for Burmese self-rule and he opposed the participation of Great Britain, and by extension Burma, in World War II. He resigned from the Legislative Assembly and was arrested for sedition. In 1940, before Japan formally entered the Second World War, Aung San formed the Burma Independence Army in Japan.

A major battleground, Burma was devastated during World War II. By March 1942, within months after they entered the war, Japanese troops had advanced on Rangoon and the British administration had collapsed. A Burmese Executive Administration headed by Ba Maw was established by the Japanese in August 1942. Wingate's British Chindits were formed into long-range penetration groups trained to operate deep behind Japanese lines.[57] A similar American unit, Merrill's Marauders, followed the Chindits into the Burmese jungle in 1943.[58] Beginning in late 1944, allied troops launched a series of offensives that led to the end of Japanese rule in July 1945. However, the battles were intense with much of Burma laid waste by the fighting. Overall, the Japanese lost some 150,000 men in Burma. Only 1,700 prisoners were taken.[59]

Although many Burmese fought initially for the Japanese as part of the Burma Independence Army, many Burmese, mostly from the ethnic minorities, served in the British Burma Army.[60] The Burma National Army and the Arakan National Army fought with the Japanese from 1942 to 1944 but switched allegiance to the Allied side in 1945. Under Japanese occupation, 170,000 to 250,000 civilians died.[61][62]

Following World War II, Aung San negotiated the Panglong Agreement with ethnic leaders that guaranteed the independence of Burma as a unified state. Aung Zan Wai, Pe Khin, Bo Hmu Aung, Sir Maung Gyi, Dr. Sein Mya Maung, Myoma U Than Kywe were among the negotiators of the historical Panglong Conference negotiated with Bamar leader General Aung San and other ethnic leaders in 1947. In 1947, Aung San became Deputy Chairman of the Executive Council of Burma, a transitional government. But in July 1947, political rivals[63] assassinated Aung San and several cabinet members.[64]

Independence

On 4 January 1948, the nation became an independent republic, named the Union of Burma, with Sao Shwe Thaik as its first President and U Nu as its first Prime Minister. Unlike most other former British colonies and overseas territories, Burma did not become a member of the Commonwealth. A bicameral parliament was formed, consisting of a Chamber of Deputies and a Chamber of Nationalities,[65] and multi-party elections were held in 1951–1952, 1956 and 1960.

The geographical area Burma encompasses today can be traced to the Panglong Agreement, which combined Burma Proper, which consisted of Lower Burma and Upper Burma, and the Frontier Areas, which had been administered separately by the British.[66]

In 1961, U Thant, then the Union of Burma's Permanent Representative to the United Nations and former Secretary to the Prime Minister, was elected Secretary-General of the United Nations, a position he held for ten years.[67] Among the Burmese to work at the UN when he was Secretary-General was a young Aung San Suu Kyi, who went on to become winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize.

Military rule

On 2 March 1962, the military led by General Ne Win took control of Burma through a coup d'état and the government has been under direct or indirect control by the military since then. Between 1962-74, Burma was ruled by a revolutionary council headed by the general, and almost all aspects of society (business, media, production) were nationalized or brought under government control under the Burmese Way to Socialism,[68] which combined Soviet-style nationalisation and central planning. A new constitution of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma was adopted in 1974. Until 1988, the country was ruled as a one-party system, with the General and other military officers resigning and ruling through the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP).[69] During this period, Burma became one of the world's most impoverished countries.[70]

There were sporadic protests against military rule during the Ne Win years and these were almost always violently suppressed. On 7 July 1962, the government broke up demonstrations at Rangoon University, killing 15 students.[68] In 1974, the military violently suppressed anti-government protests at the funeral of U Thant. Student protests in 1975, 1976 and 1977 were quickly suppressed by overwhelming force.[69]

In 1988, unrest over economic mismanagement and political oppression by the government led to widespread pro-democracy demonstrations throughout the country known as the 8888 Uprising. Security forces killed thousands of demonstrators, and General Saw Maung staged a coup d'état and formed the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). In 1989, SLORC declared martial law after widespread protests. The military government finalised plans for People's Assembly elections on 31 May 1989.[71] SLORC changed the country's official English name from the "Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma" to the "Union of Myanmar" in 1989.

In May 1990, the government held free elections for the first time in almost 30 years and the National League for Democracy (NLD), the party of Aung San Suu Kyi, won 392 out of a total 489 seats (i.e., 80% of the seats). However, the military junta refused to cede power[72] and continued to rule the nation as SLORC until 1997, and then as the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) until its dissolution in March 2011.

On 23 June 1997, Burma was admitted into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). On 27 March 2006, the military junta, which had moved the national capital from Yangon to a site near Pyinmana in November 2005, officially named the new capital Naypyidaw, meaning "city of the kings".[73]

In August 2007, an increase in the price of diesel and petrol led to a series of anti-government protests that were dealt with harshly by the government.[74] The protests then became a campaign of civil resistance (also called the Saffron Revolution.[75][76])[77] led by Buddhist monks,[78] hundreds of whom defied the house arrest of democracy advocate Aung San Suu Kyi to pay their respects at the gate of her house. The government finally cracked down on them on 26 September 2007. The crackdown was harsh, with reports of barricades at the Shwedagon Pagoda and monks killed. However, there were also rumours of disagreement within the Burmese armed forces, but none was confirmed. The military crackdown against unarmed Saffron Revolution protesters was widely condemned as part of the International reaction to the 2007 Burmese anti-government protests and led to an increase in economic sanctions against the Burmese Government.

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis caused extensive damage in the densely populated, rice-farming delta of the Irrawaddy Division.[79] It was the worst natural disaster in Burmese history with reports of an estimated 200,000 people dead or missing, and damage totaled to 10 billion US Dollars, and as many as 1 million left homeless.[80] In the critical days following this disaster, Burma's isolationist government was accused of hindering United Nations recovery efforts.[81] Humanitarian aid was requested but concerns about foreign military or intelligence presence in the country delayed the entry of United States military planes delivering medicine, food, and other supplies.[82]

In early August 2009, a conflict known as the Kokang incident broke out in Shan State in northern Burma. For several weeks, junta troops fought against ethnic minorities including the Han Chinese,[83] Wa, and Kachin.[84][85] During 8–12 August, the first days of the conflict, as many as 10,000 Burmese civilians fled to Yunnan province in neighbouring China.[84][85][86]

Democratic reforms

The goal of the Burmese constitutional referendum of 2008, held on 10 May 2008, is the creation of a "discipline-flourishing democracy". As part of the referendum process, the name of the country was changed from the "Union of Myanmar" to the "Republic of the Union of Myanmar", and general elections were held under the new constitution in 2010. Observer accounts of the 2010 election describe the event as mostly peaceful; however, allegations of polling station irregularities were raised, and the United Nations (UN) and a number of Western countries condemned the elections as fraudulent.[87]

The military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party declared victory in the 2010 elections, stating that it had been favoured by 80 percent of the votes; however, the claim was disputed by numerous pro-democracy opposition groups who asserted that the military regime had engaged in rampant fraud.[88][89] One report documented 77 percent as the official turnout rate of the election.[88] The military junta was dissolved on 30 March 2011.

Opinions differ whether the transition to liberal democracy is underway. According to some reports, the military's presence continues as the label 'disciplined democracy' suggests. This label asserts that the Burmese military is allowing certain civil liberties while clandestinely institutionalizing itself further into Burmese politics. Such an assertion assumes that reforms only occurred when the military was able to safeguard its own interests through the transition—here, "transition" does not refer to a transition to a liberal democracy, but transition to a quasi-military rule.[90]

Since the 2010 election, the government has embarked on a series of reforms to direct the country towards liberal democracy, a mixed economy, and reconciliation, although doubts persist about the motives that underpin such reforms. The series of reforms includes the release of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest, the establishment of the National Human Rights Commission, the granting of general amnesties for more than 200 political prisoners, new labour laws that permit labour unions and strikes, a relaxation of press censorship, and the regulation of currency practices.[91]

The impact of the post-election reforms has been observed in numerous areas, including ASEAN's approval of Burma's bid for the position of ASEAN chair in 2014;[92] the visit by United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in December 2011 for the encouragement of further progress—it was the first visit by a Secretary of State in more than fifty years[93] (Clinton met with Burmese president Thein Sein, as well as opposition leader Daw Aung San Suu Kyi);[94] and the participation of Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) party in the 2012 by-elections, facilitated by the government's abolition of the laws that previously barred the NLD.[95] As of July 2013, about 100[96][97] political prisoners remain imprisoned, while conflict between the Burmese Army and local insurgent groups continues.

The by-elections occurred on 1 April 2012 and the NLD won 43 of the 45 available seats; previously an illegal organization, the NLD had never won a Burmese election until this time. The 2012 by-elections were also the first time that international representatives were allowed to monitor the voting process in Burma.[98] Following announcement of the by-elections, the Freedom House organization raised concerns about "reports of fraud and harassment in the lead up to elections, including the March 23 deportation of Somsri Hananuntasuk, executive director of the Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL), a regional network of civil society organizations promoting democratization."[99]

Civil wars

Civil wars have been a constant feature of Burma's socio-political landscape since the attainment of independence in 1948. These wars are predominantly struggles for ethnic and sub-national autonomy, with the areas surrounding the ethnically Burman central districts of the country serving as the primary geographical setting of conflict. Foreign journalists and visitors require a special travel permit to visit the areas in which Burma's civil wars continue.[100]

In October 2012 the number of ongoing conflicts in Burma included the Kachin conflict,[101] between the Kachin Independence Army and the government;[102][103] a civil war between the Rohingya Muslims, and the government and non-government groups in Arakan State;[104] and a conflict between the Shan,[105][106] Lahu and Karen[107][108] minority groups, and the government in the eastern half of the country. In addition al-Qaeda signalled an intention to become involved in Myanmar. In a video released 3 September 2014 mainly addressed to India, the militant group's leader Ayman al-Zawahiri said al-Qaeda had not forgotten the Muslims of Myanmar and that the group was doing "what they can to rescue you." [109] In response, the military raised its level of alertness while the Burmese Muslim Association issued a statement saying Muslims would not tolerate any threat to their motherland.[110]

Government and politics

The constitution of Burma, its third since independence, was drafted by its military rulers and published in September 2008. The country is governed as a presidential republic with a bicameral legislature, with a portion of legislators appointed by the military and others elected in general elections. The current head of state, inaugurated as President on 30 March 2011, is Thein Sein.

The legislature, called the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, is bicameral and made up of two houses: The 224-seat upper house Amyotha Hluttaw (House of Nationalities) and the 440-seat lower house Pyithu Hluttaw (House of Representatives). The upper house consists of 224 members, of whom 168 are directly elected and 56 are appointed by the Burmese Armed Forces while the lower house consists of 440 members, of whom 330 are directly elected and 110 are appointed by the armed forces. The major political parties are the National League for Democracy, National Democratic Force and the two backed by the military: the National Unity Party, and the Union Solidarity and Development Party.

Burma's army-drafted constitution was approved in a referendum in May 2008. The results, 92.4% of the 22 million voters with an official turnout of 99%, are considered suspect by many international observers and by the National league of democracy with reports of widespread fraud, ballot stuffing, and voter intimidation.[111]

The elections of 2010 resulted in a victory for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party and various foreign observers questioned the fairness of the elections.[112][113][114] One criticism of the election was that only government sanctioned political parties were allowed to contest in it and the popular National League for Democracy was declared illegal.[115] However, immediately following the elections, the government ended the house arrest of the democracy advocate and leader of the National League for Democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi.[116] and her ability to move freely around the country is considered an important test of the military's movement toward more openness.[115] After unexpected reforms in 2011, NLD senior leaders have decided to register as a political party and to field candidates in future by-elections.[117]

Burma rates as a corrupt nation on the Corruption Perceptions Index with a rank of 157th out of 177 countries worldwide and a rating of 2.1 out of 10 (10 being least corrupt and 0 being highly corrupt) as of 2012.[118]

Foreign relations

Though the country's foreign relations, particularly with Western nations, have been strained, relations have thawed since the reforms following the 2010 elections. After years of diplomatic isolation and economic and military sanctions,[119] the United States relaxed curbs on foreign aid to Burma in November 2011[94] and announced the resumption of diplomatic relations on 13 January 2012[120] The European Union has placed sanctions on Burma, including an arms embargo, cessation of trade preferences, and suspension of all aid with the exception of humanitarian aid.[121] U.S. and European government sanctions against the former military government, coupled with boycotts and other direct pressure on corporations by supporters of the democracy movement, have resulted in the withdrawal from the country of most U.S. and many European companies.[122] On 13 April 2012 British Prime Minister David Cameron called for the economic sanctions on Burma to be suspended in the wake of the pro-democracy party gaining 43 seats out of a possible 45 in the 2012 by-elections with the party leader, Aung San Suu Kyi becoming a member of the Burmese parliament.[123]

Despite Western isolation, Asian corporations have generally remained willing to continue investing in the country and to initiate new investments, particularly in natural resource extraction. The country has close relations with neighbouring India and China with several Indian and Chinese companies operating in the country. Under India's Look East policy, fields of cooperation between India and Burma include remote sensing,[124] oil and gas exploration,[125] information technology,[126] hydro power[127] and construction of ports and buildings.[128] In 2008, India suspended military aid to Burma over the issue of human rights abuses by the ruling junta, although it has preserved extensive commercial ties, which provide the regime with much-needed revenue.[129] The thaw in relations began on 28 November 2011, when Belarusian Prime Minister Mikhail Myasnikovich and his wife Ludmila arrived in the capital, Naypyidaw, the same day as the country received a visit by US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, who also met with pro-democracy opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[130] International relations progress indicators continued in September 2012 when Aung San Suu Kyi visited to the US[131] followed by Burma's reformist president visit to the United Nations.[132]

In May 2013, Thein Sein became the first Myanmar president to visit the U.S. White House in 47 years and President Obama praised the former general for political and economic reforms, and the cessation of tensions between Myanmar and the U.S. Political activists objected to the visit due to concerns over human rights abuses in Myanmar but Obama assured Thein Sein that Myanmar will receive the support from the U.S. Prior to President Thein Sein, the last Myanmar leader to visit the White House was Ne Win in September 1966. The two leaders discussed to release more political prisoners, the institutionalization of political reform and rule of law, and ending ethnic conflict in Myanmar—the two governments agreed to sign a bilateral trade and investment framework agreement on May 21, 2013.[133]

In June 2013, Myanmar held its first ever summit, the World Economic Forum on East Asia 2013. A regional spinoff of the annual World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, the summit was held on June 5–7 and attended by 1,200 participants, including 10 heads of state, 12 ministers and 40 senior directors from around the world.[134]

Visits by Western leaders

In mid October, 2012. former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair "led a delegation" to shake hands with President Thein Sein, and met with lower house speaker Shwe Mann. A British embassy spokesperson said he was there on behalf of The Office of Tony Blair, an umbrella group of foundations—inter-faith, sports, etc.—and governance initiatives that he started up after leaving office. The spokesperson said only that he had "productive discussions about the reform process".[135]

On 3 November 2012 European Commission President José Manuel Barroso met with Myanmar's President Thein Sein in Myanmar.[136][137]

On 6 November 2012 former Australian Prime Minister, Julia Gillard met with Myanmar's President Thein Sein on the sidelines of the 9th Asia–Europe Meeting becoming the first Australian head of government to meet Burma's leader in nearly 30 years.[138]

On 12 November 2012 Sweden's Prime Minister, Fredrik Reinfeldt, met President U Thein Sein at the presidential palace in the new capital, Naypyidaw, while being accompanied on his visit by the Swedish Trade Minister Ewa Björling and two business delegations.[139]

On 19 November 2012, US President Barack Obama visited Burma following his 2012 reelection and was accompanied by Hillary Clinton, returning almost a year after her first visit. Though he did not visit the capital, President Obama delivered a speech at Rangoon University, out of respect for the university where opposition to colonial rule first took hold. Obama's speech was broadcast live via Burmese state television channels but its simultaneous spoken translations was stopped when Obama began speaking about the Kachin Conflict.[140] Obama also stated that recent violence in Rakhine state during the 2012 Rakhine State riots had to be addressed, he called for an end to communal violence between Muslims and Buddhists and then left to visit Thailand.[141][142]

Military relations

Burma has received extensive military aid from India and China in the past[143] According to some estimates, Burma has received more than US$200 million in military aid from India.[144] Burma has been a member of ASEAN since 1997. Though it gave up its turn to hold the ASEAN chair and host the ASEAN Summit in 2006, it is scheduled to chair the forum and host the summit in 2014.[145] In November 2008, Burma's political situation with neighbouring Bangladesh became tense as they began searching for natural gas in a disputed block of the Bay of Bengal.[146] The fate of Rohingya refugees also remains an issue between Bangladesh and Burma.[147]

The country's armed forces are known as the Tatmadaw, which numbers 488,000. The Tatmadaw comprises the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force. The country ranked twelfth in the world for its number of active troops in service.[24] The military is very influential in the country, with all top cabinet and ministry posts usually held by military officials. Official figures for military spending are not available. Estimates vary widely because of uncertain exchange rates, but Burma's military forces' expenses are high.[148] The country imports most of its weapons from Russia, Ukraine, China and India.

The country is building a research nuclear reactor near Pyin Oo Lwin with help from Russia. It is one of the signatories of the nuclear non-proliferation pact since 1992 and a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since 1957. The military junta had informed the IAEA in September 2000 of its intention to construct the reactor. The research reactor outbuilding frame was built by ELE steel industries limited of Yangon/Rangoon and water from Anisakhan/BE water fall will be used for the reactor cavity cooling system.[149][150]

In 2010 as part of the Wikileaks leaked cables, Burma was suspected of using North Korean construction teams to build a fortified Surface-to-Air Missile facility.[151]

Until 2005, the United Nations General Assembly annually adopted a detailed resolution about the situation in Burma by consensus.[152][152][153][154][155] But in 2006 a divided United Nations General Assembly voted through a resolution that strongly called upon the government of Burma to end its systematic violations of human rights.[156] In January 2007, Russia and China vetoed a draft resolution before the United Nations Security Council[157] calling on the government of Burma to respect human rights and begin a democratic transition. South Africa also voted against the resolution.[158]

Human rights

This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2013) |

There is consensus that the military regime in Burma is one of the world's most repressive and abusive regimes.[159][160] On 9 November 2012, Samantha Power, Barack Obama's Special Assistant to the President on Human Rights, wrote on the White House blog in advance of the president's visit that "Serious human rights abuses against civilians in several regions continue, including against women and children."[105] In addition, members of the United Nations and major international human rights organisations have issued repeated and consistent reports of widespread and systematic human rights violations in Burma. The United Nations General Assembly has repeatedly[161] called on the Burmese Military Junta to respect human rights and in November 2009 the General Assembly adopted a resolution "strongly condemning the ongoing systematic violations of human rights and fundamental freedoms" and calling on the Burmese Military Regime "to take urgent measures to put an end to violations of international human rights and humanitarian law."[162]

International human rights organizations including Human Rights Watch,[163] Amnesty International[164] and the American Association for the Advancement of Science[165] have repeatedly documented and condemned widespread human rights violations in Burma. The Freedom in the World 2011 report by Freedom House notes, "The military junta has ... suppressed nearly all basic rights; and committed human rights abuses with impunity." In July 2013, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners indicated that there were approximately 100 political prisoners being held in Burmese prisons.[96][97][166][167]

Evidence gathered by a British researcher was published in 2005 regarding the extermination or 'Burmisation' of certain ethnic minorities, such as the Karen, Karenni and Shan.[169]

Child soldiers

Child soldiers have and continue to play a major part in the Burmese Army as well as Burmese rebel movements. The Independent reported in June, 2012 that "Children are being sold as conscripts into the Burmese military for as little as $40 and a bag of rice or a can of petrol."[170] The UN's Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Radhika Coomaraswamy, who stepped down from her position a week later, met representatives of the Government of Myanmar on 5 July 2012 and stated that she hoped the government's signing of an action plan would "signal a transformation."[171] In September 2012, the Myanmar Armed Forces released 42 child soldiers and the International Labour Organization met with representatives of the government as well as the Kachin Independence Army to secure the release of more child soldiers.[172] According to Samantha Power, a U.S. delegation raised the issue of child soldiers with the government in October 2012. However, she did not comment on the government's progress towards reform in this area.[105]

A Bangkok Post article on 23 December 2012 reported that the Myanmar Armed Forces continued to use child soldiers including during the army's large offensive against the KIA in December 2012. The newspaper reported that "Many of them were pulled off Yangon streets and elsewhere and given a minimum of training before being sent to the front line."[173][unreliable source?]

Child/forced/slave labour, systematic sexual violence and human trafficking

Forced labour, human trafficking, and child labour are common.[174] The military is also notorious for rampant use of sexual violence, a practice continuing as of 2012.[15] In 2007 the international movement to defend women's human rights issues in Burma was said to be gaining speed.[175]

Genocide allegations and crimes against Rohingya people

The Rohingya people have consistently faced human rights abuses by the Burmese regime that has refused to acknowledge them as Burmese citizens (despite some of them having lived in Burma for numerous generations)—the Rohingya have been denied Burmese citizenship since the enactment of a 1982 citizenship law.[176] The Burmese regime has attempted to forcibly expel Rohingya and bring in non-Rohingyas to replace them[177]—this policy has resulted in the expulsion of approximately half of the Rohingya population from Burma, while the Rohingya people have been described as "among the world's least wanted"[178] and "one of the world's most persecuted minorities."[177][179][180]

Rohingya are also not allowed to travel without official permission, are banned from owning land and are required to sign a commitment to have no more than two children.[176] As of July 2012, the Myanmar Government does not include the Rohingya minority group—classified as stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh since 1982—on the government's list of more than 130 ethnic races and, therefore, the government states that they have no claim to Myanmar citizenship.[181]

In 2007 the German professor Bassam Tibi suggested that the Rohingya conflict may be driven by an Islamist political agenda to impose religious laws,[182] while non-religious causes have also been raised, such as a lingering resentment over the violence that occurred during the Japanese occupation of Burma in World War II—during this time period the British allied themselves with the Rohingya[183] and fought against the puppet government of Burma (composed mostly of Bamar Japanese) that helped to establish the Tatmadaw military organization that remains in power as of March 2013.

A UN envoy reported in March 2013 that unrest had re-emerged between Burma's Buddhist and Muslim communities, with violence spreading to towns that are located closer to Yangon.[184] The BBC News media outlet obtained video footage of a man with severe burns who received no assistance from passers-by or police officers even though he was lying on the ground in a public area. The footage was filmed by members of the Burmese police force in the town of Meiktila and was used as evidence that Buddhists continued to kill Muslims after the European Union sanctions were lifted on 23 April 2013.[185]

2012 Rakhine State riots

A widely publicised Burmese conflict was the 2012 Rakhine State riots, a series of conflicts that primarily involved the ethnic Rakhine Buddhist people and the Rohingya Muslim people in the northern Rakhine State—an estimated 90,000 people were displaced as a result of the riots.[186] The Burmese government previously identified the Rohingya as a group of illegal migrants; however, the ethnic group has lived in Burma for numerous centuries.[187]

The 2012 Rakhine State riots are a series of ongoing conflicts between Rohingya Muslims and ethnic Rakhine in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. The riots came after weeks of sectarian disputes and have been condemned by most people on both sides of the conflict.[188]

The immediate cause of the riots is unclear, with many commentators citing the killing of ten Burmese Muslims by ethnic Rakhine after the rape and murder of a Rakhine woman as the main cause.[189] Whole villages have been "decimated".[189] Over 300 houses and a number of public buildings have been razed. According to Tun Khin, the president of the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), as of 28 June 2012, 650 Rohingyas have been killed, 1,200 are missing, and more than 80,000 have been displaced.[190] According to the Myanmar authorities, the violence, between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims, left 78 people dead, 87 injured, and thousands of homes destroyed. It displaced more than 52,000 people.[191]

Thousands of homes were destroyed, 78 people died, 87 people were injured, and an estimated 90,000 people were displaced after the 2012 Rakhine State riots between Rohingya Muslims and Buddhists in Burma's western Rakhine State.[186][191]

The government has responded by imposing curfews and by deploying troops in the regions. On 10 June 2012, a state of emergency was declared in Rakhine, allowing the military to participate in administration of the region.[192][193] The Burmese army and police have been accused of targeting Rohingya Muslims through mass arrests and arbitrary violence.[190][194] A number of monks' organizations that played a vital role in Burma's struggle for democracy have taken measures to block any humanitarian assistance to the Rohingya community.[195]

Freedom of speech

Restrictions on media censorship were significantly eased in August 2012 following demonstrations by hundreds of protesters who wore shirts demanding that the government "Stop Killing the Press."[196] The most significant change has come in the form that media organizations will no longer have to submit their content to a censorship board before publication. However, as explained by one editorial in the exiled press The Irrawaddy, this new "freedom" has caused some Burmese journalists to simply see the new law as an attempt to create an environment of self-censorship as journalists "are required to follow 16 guidelines towards protecting the three national causes — non-disintegration of the Union, non-disintegration of national solidarity, perpetuation of sovereignty — and "journalistic ethics" to ensure their stories are accurate and do not jeopardize national security."[196] In July 2014 five journalists were sentenced to 10 years in jail after publishing a report saying the country was planning to build a new chemical weapons plant. Journalists described the jailings as a blow to the recently-won news media freedoms that had followed five decades of censorship and persecution.[197]

Praise for the 2011 government reforms

According to the Crisis Group,[198] since Burma transitioned to a new government in August 2011, the country's human rights record has been improving. Previously giving Burma its lowest rating of 7, the 2012 Freedom in the World report also notes improvement, giving Burma a 6 for improvements in civil liberties and political rights, the release of political prisoners, and a loosening of restrictions.[199] In 2013, Burma improved yet again, receiving a score of five in civil liberties and a six in political freedoms[200]

The government has assembled a National Human Rights Commission that consists of 15 members from various backgrounds.[201] Several activists in exile, including Thee Lay Thee Anyeint members, have returned to Burma after President Thein Sein's invitation to expatriates to return home to work for national development.[202] In an address to the United Nations Security Council on 22 September 2011, Burma's Foreign Minister Wunna Maung Lwin confirmed the government's intention to release prisoners in the near future.[203]

The government has also relaxed reporting laws, but these remain highly restrictive.[204] In September 2011, several banned websites, including YouTube, Democratic Voice of Burma and Voice of America, were unblocked.[205] A 2011 report by the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations found that, while contact with the Myanmar government was constrained by donor restrictions, international humanitarian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) see opportunities for effective advocacy with government officials, especially at the local level. At the same time, international NGOs are mindful of the ethical quandary of how to work with the government without bolstering or appeasing it.[206]

2013 onwards

Following Thein Sein's first ever visit to the UK and a meeting with Prime Minister David Cameron, the Myanmar president declared that all of his nation's political prisoners will be released by the end of 2013, in addition to a statement of support for the well-being of the Rohingya Muslim community. In a speech at Chatham House, he revealed that "We [Myanmar government] are reviewing all cases. I guarantee to you that by the end of this year, there will be no prisoners of conscience in Myanmar.", in addition to expressing a desire to strengthen links between the UK and Myanmar's military forces.[207]

Economy

The country is one of the poorest nations in Southeast Asia, suffering from decades of stagnation, mismanagement and isolation. The lack of an educated workforce skilled in modern technology contributes to the growing problems of the economy.[208] The country lacks adequate infrastructure. Goods travel primarily across the Thai border (where most illegal drugs are exported) and along the Irrawaddy River. Railways are old and rudimentary, with few repairs since their construction in the late 19th century.[209] Highways are normally unpaved, except in the major cities.[209] Energy shortages are common throughout the country including in Yangon and only 25% of the country's population has electricity.[210]

The military government has the majority stakeholder position in all of the major industrial corporations of the country (from oil production and consumer goods to transportation and tourism).[211][212]

The national currency is Kyat. Inflation averaged 30.1% between 2005 and 2007.[213] Inflation is a serious problem for the economy.

In 2010–2011, Bangladesh exported products worth $9.65 million to Myanmar against its import of $179 million.[214] The annual import of medicine and medical equipment to Burma during the 2000s was 160 million USD.[215]

In recent years, both China and India have attempted to strengthen ties with the government for economic benefit. Many nations, including the United States and Canada, and the European Union, have imposed investment and trade sanctions on Burma. The United States and European Union eased most of their sanctions in 2012.[216] Foreign investment comes primarily from China, Singapore, the Philippines, South Korea, India, and Thailand.[217]

Background

Under British administration, Burma was the second-wealthiest country in South-East Asia. It had been the world's largest exporter of rice. Burma also had a wealth of natural and labour resources. It produced 75% of the world's teak and had a highly literate population.[23] The country was believed to be on the fast track to development.[23] However, agricultural production fell dramatically during the 1930s as international rice prices declined, and did not recover for several decades.[218]

During World War II, the British destroyed the major oil wells and mines for tungsten, tin, lead and silver to keep them from the Japanese. Burma was bombed extensively by both sides. After a parliamentary government was formed in 1948, Prime Minister U Nu embarked upon a policy of nationalization and the state was declared the owner of all land. The government also tried to implement a poorly considered Eight-Year plan. By the 1950s, rice exports had fallen by two thirds and mineral exports by over 96% (as compared to the pre-World War II period). Plans were partly financed by printing money, which led to inflation.[219] The 1962 coup d'état was followed by an economic scheme called the Burmese Way to Socialism, a plan to nationalise all industries, with the exception of agriculture. The catastrophic program turned Burma into one of the world's most impoverished countries.[70] Burma's admittance to least developed country status by the UN in 1987 highlighted its economic bankruptcy.[220]

Agriculture

The major agricultural product is rice, which covers about 60% of the country's total cultivated land area. Rice accounts for 97% of total food grain production by weight. Through collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute 52 modern rice varieties were released in the country between 1966 and 1997, helping increase national rice production to 14 million tons in 1987 and to 19 million tons in 1996. By 1988, modern varieties were planted on half of the country's ricelands, including 98 percent of the irrigated areas.[221] In 2008 rice production was estimated at 50 million tons.[222]

Burma is also the world's second largest producer of opium, accounting for 8% of entire world production and is a major source of illegal drugs, including amphetamines.[223] Opium bans implemented since 2002 after international pressure have left ex-poppy farmers without sustainable sources of income in the Kokang and Wa regions. They depend on casual labour for income.[224]

Natural resources

Burma produces precious stones such as rubies, sapphires, pearls, and jade. Rubies are the biggest earner; 90% of the world's rubies come from the country, whose red stones are prized for their purity and hue. Thailand buys the majority of the country's gems. Burma's "Valley of Rubies", the mountainous Mogok area, 200 km (120 mi) north of Mandalay, is noted for its rare pigeon's blood rubies and blue sapphires.[225]

Many U.S. and European jewellery companies, including Bulgari, Tiffany, and Cartier, refuse to import these stones based on reports of deplorable working conditions in the mines. Human Rights Watch has encouraged a complete ban on the purchase of Burmese gems based on these reports and because nearly all profits go to the ruling junta, as the majority of mining activity in the country is government-run.[226] The government of Burma controls the gem trade by direct ownership or by joint ventures with private owners of mines.[227]

Other industries include agricultural goods, textiles, wood products, construction materials, gems, metals, oil and natural gas.

Tourism

Since 1992, the government has encouraged tourism in the country; however, fewer than 270,000 tourists entered the country in 2006 according to the Myanmar Tourism Promotion Board.[228] Burma's Minister of Hotels and Tourism Saw Lwin has stated that the government receives a significant percentage of the income of private sector tourism services.[229]

The most popular available tourist destinations in Burma include big cities such as Yangon and Mandalay; religious sites in Mon State, Pindaya, Bago and Hpa-An; nature trails in Inle Lake, Kengtung, Putao, Pyin Oo Lwin; ancient cities such as Bagan and Mrauk-U; as well as beaches in Ngapali, Ngwe-Saung, Mergui.[230] Nevertheless much of the country is off-limits to tourists, and interactions between foreigners and the people of Burma, particularly in the border regions, are subject to police scrutiny. They are not to discuss politics with foreigners, under penalty of imprisonment and, in 2001, the Myanmar Tourism Promotion Board issued an order for local officials to protect tourists and limit "unnecessary contact" between foreigners and ordinary Burmese people.[231]

The only way for travelers to enter the country seems to be by air.[232] According to the website Lonely Planet, getting into Burma (Myanmar) is problematic: "No bus or train service connects Myanmar with another country, nor can you travel by car or motorcycle across the border – you must walk across.", and states that, "It is not possible for foreigners to go to/from Myanmar by sea or river."[232] They do say that there are a small number of border crossings, but that these are limiting in that they do not allow travel into the country "You can cross from Ruili (China) to Mu-se, but not leave that way. From Mae Sai (Thailand) you can cross to Tachileik, but can only go as far as Kengtung. Those in Thailand on a visa run can cross to Kawthaung but cannot venture farther into Myanmar."[232]

Flights are available from most countries, though direct flights are limited to mainly Thai and other ASEAN airlines. According to Eleven magazine, "In the past, there were only 15 international airlines and increasing numbers of airlines have began launching direct flights from Japan, Qatar, Taiwan, South Korea, Germany and Singapore."[233] Expansions were expected in September 2013, but yet again are mainly Thai and other Asian based airlines according to Eleven Media Group's Eleven, "Thailand-based Nok Air and Business Airlines and Singapore-based Tiger Airline".[233]

Economic sanctions

The Government of Burma is under economic sanctions by the U.S. Treasury Department (31 CFR Part 537, 16 August 2005)[234] and by Executive orders 13047 (1997),[235] 13310 (2003),[235] 13448 (2007),[235] 13464 (2008),[235] and the most recent, 13619 (2012).[236] There exists debate as to the extent to which the American-led sanctions have had more adverse effects on the civilian population rather than on the military rulers.[237][238]

From May 2012 to February 2013, the United States began to lift its economic sanctions on Burma "in response to the historic reforms that have been taking place in that country."[239] Sanctions remain in place for blocked banks[240] and for any business entities that are more than 50% owned by persons on "OFAC's Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons list (SDN list)".[241]

Government stakeholders in business

The military has the majority stakeholder position in all of the major industrial corporations of the country (from oil production and consumer goods to transportation and tourism).[211][212]

Economic liberalization post 2011

In March 2012, a draft foreign investment law emerged, the first in more than 2 decades. Foreigners will no longer require a local partner to start a business in the country, and will be able to legally lease but not own property.[242] The draft law also stipulates that Burmese citizens must constitute at least 25% of the firm's skilled workforce, and with subsequent training, up to 50-75%.[242]

In 2012, the Asian Development Bank formally began re-engaging with the country, to finance infrastructure and development projects in the country. [243] The United States, Japan and the European Union countries have also begun to reduce or eliminate economic sanctions to allow foreign direct investment which will provide the Burmese government with additional tax revenue.[244]

Demographics

The provisional results of the 2014 Burma Census show that the total population is 51,419,420. This total population includes 50,213,067 persons counted during the census and an estimated 1,206,353 persons in parts of northern Rakhine State, Kachin State and Kayin State who were not counted. People who were out of the country at the time of the census are not included in these figures.[2] There are over 600,000 registered migrant workers from Burma in Thailand, and millions more work illegally. Burmese migrant workers account for 80% of Thailand's migrant workers.[245] Burma has a population density of 76 per square kilometre (200/sq mi), one of the lowest in Southeast Asia. Refugee camps exist along Indian, Bangladeshi and Thai borders while several thousand are in Malaysia. Conservative estimates state that there are over 295,800 refugees from Burma, with the majority being Karenni, and Kayin and are principally located along the Thai-Burma border.[246] There are nine permanent refugee camps along the Thai-Burma border, most of which were established in the mid-1980s. The refugee camps are under the care of the Thai-Burma Border Consortium (TBBC). Since 2006,[247] over 55,000 Burmese refugees have been resettled in the United States.[248]

There are over 53.42 million Buddhists, over 2.98 million Christians, over 2.27 million Muslims, over 300,000 Hindus and over 790,000 of those who believe in other religions in the country, according to an answer by Union Minister at Myanmar Parliament on 8 September 2011.[249]

The persecution of Burmese Indians and other ethnic groups after the military coup headed by General Ne Win in 1962 led to the expulsion or emigration of 300,000 people.[250] They migrated to escape racial discrimination and the wholesale nationalisation of private enterprise that took place in 1964.[251] The Anglo-Burmese at this time either fled the country or changed their names and blended in with the broader Burmese society.

Many Rohingya Muslims fled Burma. Many refugees headed to neighbouring Bangladesh, including 200,000 in 1978 as a result of the King Dragon operation in Arakan.[252] 250,000 more left in 1991.[253]

Largest cities

Template:Largest cities of Myanmar

Ethnic groups

Burma is home to four major language families: Sino-Tibetan, Tai–Kadai, Austro-Asiatic, and Indo-European.[254] Sino-Tibetan languages are most widely spoken. They include Burmese, Karen, Kachin, Chin, and Chinese. The primary Tai–Kadai language is Shan. Mon, Palaung, and Wa are the major Austroasiatic languages spoken in Burma. The two major Indo-European languages are Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism, and English.[255]

According to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics, Burma's official literacy rate as of 2000 was 90%.[256] Historically, Burma has had high literacy rates. To qualify for least developed country status by the UN in order to receive debt relief, Burma lowered its official literacy rate from 79% to 19% in 1987.[257] [clarification needed]

Burma is ethnically diverse. The government recognises 135 distinct ethnic groups. While it is extremely difficult to verify this statement, there are at least 108 different ethnolinguistic groups in Burma, consisting mainly of distinct Tibeto-Burman peoples, but with sizeable populations of Tai–Kadai, Hmong–Mien, and Austroasiatic (Mon–Khmer) peoples.[258] The Bamar form an estimated 68% of the population.[259] 10% of the population are Shan.[259] The Kayin make up 7% of the population.[259] The Rakhine people constitute 4% of the population. Overseas Chinese form approximately 3% of the population.[259][260] Burma's ethnic minority groups prefer the term "ethnic nationality" over "ethnic minority" as the term "minority" furthers their sense of insecurity in the face of what is often described as "Burmanisation"—the proliferation and domination of the dominant Bamar culture over minority cultures.

Mon, who form 2% of the population, are ethno-linguistically related to the Khmer.[259] Overseas Indians are 2%.[259] The remainder are Kachin, Chin, Anglo-Indians, Gurkha, Nepali and other ethnic minorities. Included in this group are the Anglo-Burmese. Once forming a large and influential community, the Anglo-Burmese left the country in steady streams from 1958 onwards, principally to Australia and the U.K.. Today, it is estimated that only 52,000 Anglo-Burmese remain in the country. As of 2009[update], 110,000 Burmese refugees were living in refugee camps in Thailand.[261]

89% of the country's population are Buddhist, according to a report on ABC World News Tonight in May 2008 and the Buddha Dharma Education Association.[262]

Language

Burmese, the mother tongue of the Bamar and official language of Burma, is related to Tibetan and to the Chinese languages.[255] It is written in a script consisting of circular and semi-circular letters, which were adapted from the Mon script, which in turn was developed from a southern Indian script in the 5th century. The earliest known inscriptions in the Burmese script date from the 11th century. It is also used to write Pali, the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism, as well as several ethnic minority languages, including Shan, several Karen dialects, and Kayah (Karenni), with the addition of specialised characters and diacritics for each language.[263] The Burmese language incorporates widespread usage of honorifics and is age-oriented.[264] Burmese society has traditionally stressed the importance of education. In villages, secular schooling often takes place in monasteries. Secondary and tertiary education take place at government schools.

Religion

Many religions are practised in Burma. Religious edifices and orders have been in existence for many years. Festivals can be held on a grand scale. The Christian and Muslim populations do, however, face religious persecution and it is hard, if not impossible, for non-Buddhists to join the army or get government jobs, the main route to success in the country.[266] Such persecution and targeting of civilians is particularly notable in Eastern Burma, where over 3000 villages have been destroyed in the past ten years.[267][268][269] More than 200,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh over the last 20 years to escape persecution.[270]

A large majority of the population practices Buddhism; estimates range from 80% [265] to 89% [271]. Theravāda Buddhism is the most widespread [271]. Other religions are practiced largely without obstruction, with the notable exception of some ethnic minorities such as the Muslim Rohingya people, who have continued to have their citizenship status denied and treated as illegal immigrants instead,[176] and Christians in Chin State.[272] 4% of the population practices Islam; 4% Christianity; 1% traditional animistic beliefs; and 2% follow other religions, including Mahayana Buddhism, Hinduism, and East Asian religions.[273][274][275] However, according to a U.S. State Department's 2010 international religious freedom report, official statistics are alleged to underestimate the non-Buddhist population. Independent researchers put the Muslim population at 6 to 10% of the population. A tiny Jewish community in Rangoon had a synagogue but no resident rabbi to conduct services.[276]

Although Hinduism is presently only practiced by 1% of the population, it was a major religion in Burma's past. Several strains of Hinduism existed alongside both Theravada Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism in the Mon and Pyu period in the first millennium CE,[277] and down to the Pagan period (9th to 13th centuries) when "Saivite and Vaishana elements enjoyed greater elite influence than they would later do."[278]

Culture

A diverse range of indigenous cultures exist in Burma, the majority culture is primarily Buddhist and Bamar. Bamar culture has been influenced by the cultures of neighbouring countries. This is manifested in its language, cuisine, music, dance and theatre. The arts, particularly literature, have historically been influenced by the local form of Theravada Buddhism. Considered the national epic of Burma, the Yama Zatdaw, an adaptation of India's Ramayana, has been influenced greatly by Thai, Mon, and Indian versions of the play.[279] Buddhism is practised along with nat worship, which involves elaborate rituals to propitiate one from a pantheon of 37 nats.[280][281]

Mohinga, traditional Burmese rice noodles in fish soup, is widely considered to be Burma's national dish.

In a traditional village, the monastery is the centre of cultural life. Monks are venerated and supported by the lay people. A novitiation ceremony called shinbyu is the most important coming of age events for a boy, during which he enters the monastery for a short time.[282] All male children in Buddhist families are encouraged to be a novice (beginner for Buddhism) before the age of twenty and to be a monk after the age of twenty. Girls have ear-piercing ceremonies (‹See Tfd›နားသ) at the same time.[282] Burmese culture is most evident in villages where local festivals are held throughout the year, the most important being the pagoda festival.[264][283] Many villages have a guardian nat, and superstition and taboos are commonplace.

British colonial rule introduced Western elements of culture to Burma. Burma's education system is modelled after that of the United Kingdom. Colonial architectural influences are most evident in major cities such as Yangon.[284] Many ethnic minorities, particularly the Karen in the southeast and the Kachin and Chin who populate the north and northeast, practice Christianity.[285] According to the The World Factbook, the Burman population is 68% and the ethnic groups constitute 32%. However, the exiled leaders and organisations claims that ethnic population is 40%, which is implicitly contrasted with CIA report (official U.S. report).

Art

Burmese contemporary art has developed rather on its own terms and quite rapidly.

One of the first to study western art was Ba Nyan. Together with Ngwe Gaing and a handful of other artists, they were pioneers of western painting style in Burma. Later, most of the students learnt from masters through apprenticeship. Some well known contemporary artists are Lun Gywe, Aung Kyaw Htet, MPP Yei Myint, Myint Swe, Min Wai Aung, Aung Myint, Khin Maung Yin, Po Po and Zaw Zaw Aung.

Most of the young artists who were born in the 1980s have greater chances of art practises inside and outside the country. Performance art is a popular genre among Burmese young artists.

Media

Due to Burma's political climate, there are not many media companies in relation to the country's population, although a certain number exists. Some are privately owned. All programming must meet with the approval of the censorship board.

The Burmese government announced on 20 August 2012 that it will stop censoring media before publication. Following the announcement, newspapers and other outlets no longer required approved by state censors; however, journalists in the country can still face consequences for what they write and say.[286]

Burma was in the attention of the media's eye when on 18 November 2012 Barack Obama visited the country, making it the first time a sitting U.S. president has traveled there.[287]

In April 2013, international media reports were published to relay the enactment of the media liberalisation reforms that we announced in August 2012. For the first time in numerous decades, the publication of privately owned newspapers commenced in the country.[288]

Film