Wet market: Difference between revisions

m Fix PMC warnings |

missing file? |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

|piccap=A wet market in Hong Kong |

|piccap=A wet market in Hong Kong |

||

|picsize=250px |

|picsize=250px |

||

|pic2=Geese in cages at wet market, Shenzhen, China.jpg |

|||

|piccap2=Geese in a wet market in [[Shenzhen]] in 2013. |

|||

|picsize2=250px |

|||

|c=[[wiktionary:街市|街市]] |

|c=[[wiktionary:街市|街市]] |

||

|j=gaai<sup>1</sup> si<sup>5</sup> |

|j=gaai<sup>1</sup> si<sup>5</sup> |

||

Revision as of 19:46, 15 April 2020

| Wet market | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A wet market in Hong Kong | |||||||||

| Chinese | 街市 | ||||||||

| Jyutping | gaai1 si5 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | street market | ||||||||

| |||||||||

A wet market (also called a public market)[1][2][3] is a marketplace selling fresh meat, fish, produce, and other perishable goods as distinguished from "dry markets" that sell durable goods such as fabric and electronics.[4][5][6] Not all wet markets sell live animals, but the term wet market is sometimes used to signify a live animal market in which vendors slaughter animals upon customer purchase.[7][8][9] Wet markets are common in many parts of the world,[10][11][12][13][14] notably in China and Southeast Asia, and include a wide variety of markets, such as farmers' markets, fish markets, and wildlife markets.[1][15] They often play critical roles in urban food security due to factors of pricing, freshness of food, social interaction, and local cultures.[1][2][3]

Not all wet markets carry living animals or wildlife products,[1][12][15][14] but those that do have been linked to outbreaks of zoonotic diseases, with one such market believed to have played a role in the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[12][16] Wet markets were banned from holding wildlife in China in 2003, after the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak which was directly tied to those practices.[16] Such regulations were lifted before being put into place again in 2020,[16] with other countries proposing similar bans.[17] Media reports that fail to distinguish between all wet markets from those with live animals or wildlife, as well as insinuations of fostering wildlife smuggling, have been blamed for fueling xenophobia related to the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic.[15][18][13]

Background

Terminology

The term "wet market" came into common use in Singapore in the early 1970s when the government used it to distinguish such traditional markets from the supermarkets that had become popular there.[19] The term was added to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 2016, as a term used throughout Southeast Asia.[20] The OED's earliest cited use of the term is from The Straits Times of Singapore in 1978.[5]

The "wet" in "wet market" refers to the constantly[21] wet floors due to the melting of ice used to keep food from spoiling,[19][22] the washing of meat and seafood stalls and the spraying of fresh produce.[21][9][14]

The term "public market" may be synonymous with "wet market",[1][2][3] although it may sometimes refer exclusively to state-owned and community-owned wet markets.[1][2][3] Wet markets may also be called "fresh food markets" and "good food markets" when referring to markets consisting of numerous competing vendors primarily selling fruits and vegetables.[6] The term "wet market" is frequently used to signify a live animal market that sells directly to consumers,[7][8] although the terms are not synonymous.[13]

Types

The term "wet market", which specifies markets that sell fresh produce and meat, includes a broad variety of markets.[1][15] Wet markets can be categorized according to their ownership structure (privately owned, state-owned, or community-owned), scale (wholesale or retail), and produce (vegetables, slaughtered meat, live animals).[1][15] They can be further subcategorized based on whether the meat inventory originates from domesticated or wild animals.[1][15]

Traditional wet markets are typically housed in temporary sheds, open-air sites,[1][23][24][14] or partially open commercial complexes,[25][13] while modern wet markets are housed in buildings often equipped with improved ventilation, freezing, and refrigeration facilities.[1][26][27]

Economic role

Wet markets are less dependent on imported goods than supermarkets due to their smaller volumes and lesser emphasis on consistency.[28] Wet markets have been described as "critical for ensuring urban food security", particularly in Chinese cities.[1] The influence of wet markets on urban food security include food pricing and physical accessibility.[1]

Researchers have highlighted the lower prices, greater freshness of food, negotiation opportunities, and social interaction spaces as key reasons for the persistence of wet markets.[1][22][29][30] The persistence of wet markets has also been attributed to "culinary traditions that call for freshly slaughtered meat and fish as opposed to frozen meats".[22]

In developing countries with agriculture-based economies, fresh meat is mainly distributed through traditional wet markets or meat stalls.[31] Wet markets selling fresh meat are often attached to or located near slaughter facilities.[31]

Health concerns

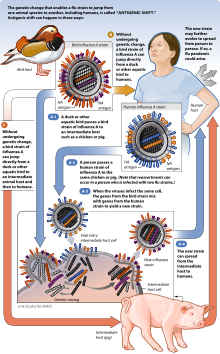

If sanitation standards are not maintained, wet markets can spread disease. Those that carry live animals and wildlife are at especially high risk of transmitting zoonoses. Because of the openness, newly introduced animals may come in direct contact with sales clerks, butchers, and customers or to other animals which they would never interact with in the wild. This may allow for some animals to act as intermediate hosts, helping a disease spread to humans.[32]

Due to unhygienic sanitation standards and the connection to the spread of zoonoses and pandemics, some have grouped wet markets together with factory farming as major health hazards in China and across the world.[33][34][35][36]

Avian flu and SARS

The H5N1 avian flu, SARS, and COVID-19 outbreaks can be traced to keeping live animals in wet markets where the potential for zoonotic transmission is greatly increased.[37][38][32] In April 2020, scientist Peter Daszak described a Chinese wet market as follows: "it is a bit of shock to go to a wildlife market and see this huge diversity of animals live in cages on top of each other with a pile of guts that have been pulled out of an animal and thrown on the floor [...] These are perfect places for viruses to spread."[39] In a 2007 study, Chinese scientists identified the presence of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats combined with unsanitary wildlife markets and the culture of eating exotic mammals in southern China as a "time-bomb".[40] A 2018 study in Malaysia concluded that wet market workers were at greater risk for leptospirosis infections.[41]

Chinese environmentalists, researchers and state media have called for stricter regulation of exotic animal trade in the markets.[42] Medical experts Zhong Nanshan, Guan Yi and Yuen Kwok-yung have also called for the closure of wildlife markets since 2010.[43]

COVID-19

Amidst the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, Chinese wet markets have been blamed for the outbreak.[44] Some reports say wildlife markets in other countries of Asia,[45][46][47] Africa,[48][49][50] and in general all over the world are also similarly prone to health risks.[51] In April 2020, a group of US lawmakers, NIAID director Anthony Fauci, UNEP biodiversity chief Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, and CBCGDF secretary general Zhou Jinfeng called for the global closure of wildlife markets due to the potential for zoonotic diseases and risk to endangered species.[52][53][54]

Around the world

China

In 2018, wet markets were noted to have remained the most prevalent food outlet in urban regions of China despite the rise of supermarket chains since the 1990s.[55] However, wet markets have been losing ground in popularity compared to supermarkets, despite the fact they may be seen as healthier and more sustainable.[36] Reports suggest "although there are well-managed, hygienic wet markets in and near bigger cities [in China], hygiene can be spotty, especially in smaller communities."[42] During the 2010s, "smart markets" equipped with e-payment terminals emerged as traditional wet markets faced increasing competition from discount stores.[56] Wet markets also began facing competition from online grocery stores, such as Alibaba's Hema stores.[9]

Since the 1990s, large cities across China have moved traditional outdoor wet markets to modern indoor facilities.[24][1] In 1999, all roadside markets in Hangzhou were banned and moved indoors.[56] By 2014, all wet markets in Nanjing were moved indoors.[1]

The trade of wildlife is not common in China, particularly in large cities,[9] and most wet markets in China do not contain live animals besides fish held in tanks.[14] However, some poorly-regulated Chinese wet markets provide outlets for the exotic wildlife trade industry that was estimated to be worth more than $73 billion in a 2017 Chinese government report.[9][14] In 2003, wet markets across China were banned from holding wildlife after the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak, which was directly tied to such practices.[16] In 2014, live poultry was banned from all markets in Hangzhou due to the H7N9 avian influenza outbreak.[56] Although the exact origin of the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic is yet to be confirmed as of April 2020,[57][58][59] it has been linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China.[60] Following the outbreak, epidemiology experts from China and an number of animal welfare organizations called to ban the operation of wet markets selling wild animals for human consumption.[43][61][62]

The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was shut down on 1 January 2020.[14] The Chinese government subsequently announced a temporary ban on the sale of wild animal products at wet markets in late January 2020,[45][63][14] and then a permanent ban in February 2020 with an exception for Traditional Chinese Medicine ingredients.[63][64] By 22 March 2020, at least 94% of the temporarily closed wet markets in China were reopened according to Chinese state-run media,[9][36] leading to public criticism of the Chinese government's handling of wet markets by Anthony Fauci and Lindsey Graham.[65][66][52] As of April 2020, the Chinese government is drafting a permanent law to further tighten restrictions on wildlife trade.[9][14]

Hong Kong

On 16 May 1842, Central Market was opened in a central position on Queen's Road. In this market, people could find all kinds of meat, fruit and vegetables, poultry, salt fish, fresh fish, weighing rooms and money changers.[67]

In 1920, the Reclamation Street Market was opened in Hong Kong. Due to structure problems, Reclamation Street Market was removed by the government in 1953.[68] In 1957, Yau Ma Tei Street Market launched to replace the Reclamation Street Market.[69] There were fixed-pitch stalls which sold vegetables, fruits, seafood, beef, pork, and poultry. Also, there were stalls selling baby chickens, baby ducks, and three-striped box turtles as pets.[70]

In 1994, wet markets accounted for 70% of produce sales and 50% of meat sales in Hong Kong.[71]

Prior to 2000, many of Hong Kong's wet markets were managed by the Urban Council (within Hong Kong Island and Kowloon) or the Regional Council (in the New Territories). Since the disbandment of the two councils on 31 December 1999, these markets have been managed by the Food and Environmental Hygiene Department (FEHD) of the Hong Kong government.[72][73]

In 2008 the government of Hong Kong proposed that all poultry should be slaughtered at central abattoirs to combat the spread of avian flu.[74]

In 2018, the FEHD operated 74 wet markets housing approximately 13,070 stalls.[72] In addition, the Hong Kong Housing Authority operated 21 markets while private developers operated about 99 (in 2017).[75] As of 2018, planning is underway for new wet markets in the new towns at Tung Chung, Tin Shui Wai, Hung Shui Kiu, Tseung Kwan O, and Kwu Tung North.[72]

In Hong Kong, wet markets are most frequented by older residents, those with lower incomes, and domestic helpers who serve approximately 10 percent of Hong Kong's residents.[76] Most districts contain at least one wet market.[9] Wet markets have become destinations for tourists to "see the real Hong Kong".[77] Many of the wet market buildings are owned by property investment firms and as a result the price of food can vary from market to market.[78] Hong Kong's wet markets are known to use red lampshades to make the food look fresher.[79]

Markets in Hong Kong are governed by the law of Hong Kong, not Chinese law. Under the Slaughterhouse Regulation, the slaughtering of live bovine animals, swine, goats, sheep or soliped for human consumption must take place in a licenced slaughterhouse.[80] The largest of the territory's three licenced slaughterhouses is the Sheung Shui Slaughterhouse, operated by the Hong Kong government, which supplies most of the fresh beef, pork and mutton sold at Hong Kong wet markets.[citation needed] None of the wet markets in Hong Kong hold wild or exotic animals.[9]

The retail sale of live poultry in Hong Kong is permitted at licenced outlets only. At the end of 2016, there were 85 retail shops within public wet markets licenced to sell live poultry.[81] The FEHD has implemented a number of measures to reduce the risk of avian influenza. Regular inspections and cleaning take place, including nightly disinfection of each stall by external contractors. Stall owners selling live poultry are not allowed to keep the animals on the premises overnight; they must be slaughtered before 8:00 pm nightly.[82]

Indonesia

Traditional wet markets (such as pasar pagi) are found across in Indonesia in both urban and rural areas. Wet markets face increasing competition from supermarkets as well as e-commerce companies like Shopee and Tokopedia.[26] In 2018, Indonesian wet market vendors that import goods expressed concerns over the decrease in value of the Indonesian rupiah.[26]

Many urban wet markets have undergone major renovations during the last decade, such as Jakarta's Mayestik Market, to modernize them by introducing air conditioning, better ventilation, improved rubbish and liquid disposal systems, improved hygiene, and more safe and comfortable facilities for sellers.[citation needed] In 2018, the first modern wet market opened in Jakarta with a laboratory as well as freezing and refrigeration facilities.[26]

Malaysia

In March 2020, the Malaysian government temporarily banned the operation of all wet markets (including pasar malam and pasar pagi) as a national response to the coronavirus pandemic.[83]

Mexico

Some traditional Mexican open-air markets called tianguis, such as the Mercado Margarita Maza de Juárez in Oaxaca, are separated into a wet market (zona húmeda) and a dry market (zona seca).[84]

Philippines

In the Philippines, wet markets are managed by cooperatives according to legislation such as the Cooperatives Code (RA 7160) and the Agriculture and Fisheries Modernization Act (RA 8435).[85] The Philippine government has control over the price of some commodities sold in palengkes, especially critical foods such as rice.[86][87]

In July 2017, the digital wet market Palengke Boy was launched in Davao City to compete against traditional wet markets.[88] In March 2020, the Pasig local government launched a mobile wet market to ensure access to basic goods during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[89]

Singapore

Wet markets in Singapore are subsidized by the government.[26] The Tekka Market, Tiong Bahru Market, and Chinatown Complex Market are prominent wet markets containing seasonal fruit, fresh vegetables, imported beef, and live seafood.[90]

In the early 1990s, the slaughter of animals was banned in 12 inner-city markets and 22 wet market centers in Singapore.[91] In early 2020, the National Environment Agency issued advisories for "high standards of hygiene and cleanliness" for the 83 markets that it oversees in a response to the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.[22]

Taiwan

In 1997, a report by the Taipei city government indicated that the city had 61 major wet markets with almost 10,000 registered vendors.[92] The report also indicated that most of the city's wet markets were in serious need of repair and that almost 3,500 of the vendor stalls lay vacant.[92]

The Nanmen Market in Taipei is a government-owned traditional wet market that was opened in 1907 during the Japanese colonial rule.[27][92] The market building was demolished in October 2019 and the market temporarily relocated until its replacement modern 12-floor building is completed in 2022.[27]

Thailand

Wet markets are the dominant preferred venue for grocery shopping in Thailand due to the local importance of fresh food,[93] as well as lower prices and familiarity with shopkeepers.[26]

Vietnam

In 2017, there were approximately 9,000 wet markets, 800 supermarkets, 160 shopping malls and 1.3 million small family-owned stores across Vietnam according to government estimates.[94]

In 2017, the Hanoi city government planned to renovate the city's wet markets and transform them into modern shopping malls.[94] The plan was met with resistance from wet market vendors in 2017 after significant declines in sales figures from other markets that were moved to the basements of high-end shopping centers.[94]

In 2020, Prime Minister of Vietnam Nguyễn Xuân Phúc announced proposals to ban wildlife trade in Vietnam.[17]

Media coverage

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2020) |

Chinese wet markets have been criticized in media outlets during the COVID-19 outbreak.[44]

In Western media wet markets have been portrayed without distinguishing between general wet markets, live animal wet markets, and wildlife markets,[42] using montages of images from different markets across China without identifying locations.[15][95] Most wet markets in China do not sell wild animals.[36][96][15] These depictions have been criticized as exaggerated and Orientalist, and have been blamed for fueling Sinophobia and "Chinese otherness".[15][95][18]

Since the outbreak of the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic, media reports urging for permanent blanket bans on all wet markets—as opposed to solely live animal markets or wildlife markets—have been criticized for undermining infection control needs to be specific about wildlife markets, such as the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market.[15]

See also

- Artisanal food

- Asian supermarket

- Bazaar

- Pasar malam

- Souk

- Ye wei (southern China)

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Scott, Steffanie; Huang, Xianjin (2019). "Achieving urban food security through a hybrid public-private food provisioning system: the case of Nanjing, China". Food Security. 11 (5): 1071–1086. doi:10.1007/s12571-019-00961-8. ISSN 1876-4517.

- ^ a b c d Morales, Alfonso (2009). "Public Markets as Community Development Tools". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 28 (4): 426–440. doi:10.1177/0739456X08329471. ISSN 0739-456X.

- ^ a b c d Morales, Alfonso (2011). "Marketplaces: Prospects for Social, Economic, and Political Development". Journal of Planning Literature. 26 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1177/0885412210388040. ISSN 0885-4122.

- ^ Wholesale Markets: Planning and Design Manual (Fao Agricultural Services Bulletin) (No 90)

- ^ a b "wet, adj". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

wet market n. South-East Asian a market for the sale of fresh meat, fish, and produce

- ^ a b Brown, Allison (2001). "Counting Farmers Markets". Geographical Review. 91 (4): 655–674. doi:10.2307/3594724. JSTOR 3594724.

- ^ a b Woo, Patrick CY; Lau, Susanna KP; Yuen, Kwok-yung (2006). "Infectious diseases emerging from Chinese wet-markets: zoonotic origins of severe respiratory viral infections". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 19 (5): 401–407. doi:10.1097/01.qco.0000244043.08264.fc. ISSN 0951-7375. PMID 16940861.

- ^ a b Wan, X.F. (2012). "Lessons from Emergence of A/Goose/Guangdong/1996-Like H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses and Recent Influenza Surveillance Efforts in Southern China: Lessons from Gs/Gd/96-like H5N1 HPAIVs". Zoonoses and Public Health. 59: 32–42. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01497.x. PMC 4119829. PMID 22958248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Westcott, Ben; Wang, Serenitie (15 April 2020). "China's wet markets are not what some people think they are". CNN. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Rahman, Khaleda (28 March 2020). "PETA launches petition to shut down live animal markets that breed diseases like COVID-19". Newsweek. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Reardon, Thomas; Timmer, C. Peter; Minten, Bart (31 July 2012). "Supermarket revolution in Asia and emerging development strategies to include small farmers". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (31): 12332–12337. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912332R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1003160108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3412023. PMID 21135250.

- ^ a b c "Why Wet Markets Are The Perfect Place To Spread Disease". NPR.org. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d Samuel, Sigal (15 April 2020). "The coronavirus likely came from China's wet markets. They're reopening anyway". Vox. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Standaert, Michael (15 April 2020). "'Mixed with prejudice': calls for ban on 'wet' markets misguided, experts argue". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lynteris, Christos; Fearnley, Lyle (2 March 2020). "Why shutting down Chinese 'wet markets' could be a terrible mistake". The Conversation. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Yu, Sun; Liu, Xinning (23 February 2020). "Coronavirus piles pressure on China's exotic animal trade". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Reed, John (19 March 2020). "The economic case for ending wildlife trade hits home in Vietnam". Financial Times. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Palmer, James (27 January 2020). "Don't Blame Bat Soup for the Coronavirus". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b Tan, Alvin (2013). Wet Markets (PDF). Community Heritage Series. Vol. II. Singapore: National Heritage Board. p. 3. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "New Singapore English words". Oxford University Press. 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b Burton, Dawn (2008). Cross-Cultural Marketing: Theory, Practice and Relevance. Routledge. p. 146. ISBN 9781134060177.

- ^ a b c d Chandran, Rina (7 February 2020). "Traditional markets blamed for virus outbreak are lifeline for Asia's poor". Reuters. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ Shaheen, Therese (19 March 2020). "The Chinese Wild-Animal Industry and Wet Markets Must Go". National Review. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b Hu, Dong-wen; Liu, Chen-xing; Zhao, Hong-bo; Ren, Da-xi; Zheng, Xiao-dong; Chen, Wei (2019). "Systematic study of the quality and safety of chilled pork from wet markets, supermarkets, and online markets in China". Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE B. 20 (1): 95–104. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1800273. ISSN 1673-1581. PMC 6331336. PMID 30614233.

- ^ Zhong, Shuru; Crang, Mike; Zeng, Guojun (2020). "Constructing freshness: the vitality of wet markets in urban China". Agriculture and Human Values. 37 (1): 175–185. doi:10.1007/s10460-019-09987-2. ISSN 0889-048X.

- ^ a b c d e f Roughneen, Simon (8 October 2018). "Southeast Asia's traditional markets hold their own". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Nanmen Market to close for renovation after 38 years". Focus Taiwan. 6 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Agricultural Trade Highlights. Foreign Agricultural Service. 1994. p. 12.

- ^ Bougoure, Ursula; Lee, Bernard (2009). Lindgreen, Adam (ed.). "Service quality in Hong Kong: wet markets vs supermarkets". British Food Journal. 111 (1): 70–79. doi:10.1108/00070700910924245. ISSN 0007-070X.

- ^ Mele, Christopher; Ng, Megan; Chim, May Bo (2015). "Urban markets as a 'corrective' to advanced urbanism: The social space of wet markets in contemporary Singapore". Urban Studies. 52 (1): 103–120. doi:10.1177/0042098014524613. ISSN 0042-0980.

- ^ a b "Fresh Meat". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 25 November 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "China's Wet Markets, America's Factory Farming". National Review. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Building a factory farmed future, one pandemic at a time". www.grain.org. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ info@sustainablefoodtrust.org, Sustainable Food Trust-. "Sustainable Food Trust". Sustainable Food Trust. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d Fickling, David (3 April 2020). "China Is Reopening Its Wet Markets. That's Good". Bloomberg.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "New Coronavirus 'Won't Be the Last' Outbreak to Move from Animal to Human". Goats and Soda. NPR. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ "Calls for global ban on wild animal markets amid coronavirus outbreak". The Guardian. London. 24 January 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/06/us/coronavirus-scientists-debate-origin-theories-invs/index.html

- ^ Cheng, VC (2007). "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as an Agent of Emerging and Reemerging Infection". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (4): 660–94. doi:10.1128/CMR.00023-07. PMC 2176051. PMID 17934078.

- ^ Rahman, Mas Harithulfadhli Agus Ab; Hairon, Suhaily Mohd; Hamat, Rukman Awang; Jamaluddin, Tengku Zetty Maztura Tengku; Shafei, Mohd Nazri; Idris, Norazlin; Osman, Malina; Sukeri, Surianti; Wahab, Zainudin A.; Mohammad, Wan Mohd Zahiruddin Wan; Idris, Zawaha (2018). "Seroprevalence and distribution of leptospirosis serovars among wet market workers in northeastern, Malaysia: a cross sectional study". BMC Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): 569. doi:10.1186/s12879-018-3470-5. ISSN 1471-2334. PMC 6236877. PMID 30428852.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c "Wuhan Is Returning to Life. So Are Its Disputed Wet Markets". Bloomberg Australia-NZ. 8 April 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b "Wuhan coronavirus another reason to ban China's wildlife trade forever". South China Morning Post. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ^ a b Spinney, Laura (28 March 2020). "Is factory farming to blame for coronavirus?". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Most of the attention so far has been focused on the interface between humans and the intermediate host, with fingers of blame being pointed at Chinese wet markets and eating habits,...

- ^ a b "China Could End the Global Trade in Wildlife". Sierra Club. 26 March 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus expert calls for shut down of Asia's wildlife markets". Nine News Australia. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Wild Animal Markets Spark Fear in Fight Against Coronavirus". Time. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ "Africa Risks Virus Outbreak From Wildlife Trade". WildAid. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ "A sea change in China's attitude towards wildlife exploitation may just save the planet". Daily Maverick. 2 March 2020.

Knights hoped China would also play a role to help "countries around the world. It's no good simply banning the trade in China. The same risks are very much out there in Asia as well as Africa."

- ^ "Crackdown on wet markets and illegal wildlife trade could prevent the next pandemic". Mongabay India. 25 March 2020.

...what we do know is that wet markets such as Wuhan, and for that matter Agartala's Golbazar or the thousands such that exist in Asia and Africa allow for easy transmission of viruses and other pathogens from animals to humans.

- ^ Mekelburg, Madlin. "Fact-check: Is Chinese culture to blame for the coronavirus?". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b Forgey, Quint (3 April 2020). "'Shut down those things right away': Calls to close 'wet markets' ramp up pressure on China". Politico. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (6 April 2020). "Ban wildlife markets to avert pandemics, says UN biodiversity chief". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ Fortier-Bensen, Tony (9 April 2020). "Sen. Lindsey Graham, among others, urge global ban of live wildlife markets and trade". ABC News. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Zhong, Taiyang; Si, Zhenzhong; Crush, Jonathan; Xu, Zhiying; Huang, Xianjin; Scott, Steffanie; Tang, Shuangshuang; Zhang, Xiang (2018). "The Impact of Proximity to Wet Markets and Supermarkets on Household Dietary Diversity in Nanjing City, China". Sustainability. 10 (5): 1465. doi:10.3390/su10051465. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ a b c Jia, Shi (31 May 2018). "Regeneration and reinvention of Hangzhou's wet markets". Shanghai Daily. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Lu, Donna. "The hunt for patient zero: Where did the coronavirus outbreak start?". New Scientist. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Experts know the new coronavirus is not a bioweapon. They disagree on whether it could have leaked from a research lab". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Readfearn, Graham (9 April 2020). "How did coronavirus start and where did it come from? Was it really Wuhan's animal market?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19: What we know so far about the 2019 novel coronavirus".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Experts call for global ban on live animal markets, wildlife trade amidst coronavirus outbreak". CBC. 17 February 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Sarah Boseley (24 January 2020), Calls for global ban on wild animal markets amid coronavirus outbreak, The Guardian

- ^ a b Woodward, Aylin (25 February 2020), China just banned the trade and consumption of wild animals. Experts think the coronavirus jumped from live animals to people at a market., Business Insider, retrieved 15 April 2020,

A few weeks later, Chinese authorities temporarily banned the buying, selling, and transportation of wild animals in markets, restaurants, and online marketplaces across the country. Farms that breed and transport wildlife were also quarantined and shut down. The ban was expected to stay in place until the coronavirus epidemic ended, Xinhua News reported. But now it's permanent.

- ^ Gorman, James (27 February 2020). "China's Ban on Wildlife Trade a Big Step, but Has Loopholes, Conservationists Say". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ O'reilly, Andrew (2 April 2020). "Lindsey Graham asks China to close 'all operating wet markets' after coronavirus outbreak". Fox News. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bowden, John (2 April 2020). "Graham asks colleagues to support call for China to close wet markets". The Hill. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The Friend Of China, and Hong Kong Gazette" (PDF). 12 May 1842. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Bao Shaolin (2012). 第二屆廿一世紀華人地區歷史教育論文集 [Second Collection of Historical Education Papers on Chinese in the 21st Century] (in Chinese). Zhonghua Book Company (Hong Kong) Limited. p. 332.

- ^ "油麻地新建街市昨晨開幕後營業" [Yau Ma Tei New Market opened after opening yesterday morning]. Hong Kong Business Daily (in Chinese). 2 November 1957. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Yau Ma Tei's wet markets in the early post-war period". 29 March 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ Agricultural Trade Highlights. Foreign Agricultural Service. 1994. p. 7.

- ^ a b c "Chapter IV – Environmental Hygiene". Annual Report 2018. Food and Environmental Hygiene Department.

- ^ "Report No. 51 of the Director of Audit — Chapter 6" (PDF). Audit Commission. November 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ^ "Central abattoir set for 2011". Archive.news.gov.hk. 13 June 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ "Public markets" (PDF). Legislative Council Secretariat. 27 September 2017.

- ^ "EmeraldInsight". EmeraldInsight.com. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Chong, Sei (18 March 2011). "A Guide to Hong Kong's Wet Markets". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Elmer W. Cagape (8 September 2011). "Tung Chung town pays the most for food in Hong Kong". Asian Correspondent. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ 超巨街市燈現身商場 [Super large wet market red lamps appears in shopping mall]. Sharp Daily (in Chinese). 14 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Cap. 132BU Slaughterhouses Regulation". Hong Kong e-Legislation. Department of Justice.

- ^ "Study on the Way Forward of Live Poultry Trade in Hong Kong" (PDF). Food and Health Bureau. March 2017.

- ^ "Faecal droppings of live poultry from Yan Oi Market in Tuen Mun tested positive of H7N9 virus". Hong Kong Government. 5 June 2016.

- ^ "Negri hawkers, food trucks to operate 7am-8pm from March 24". The Star. 22 March 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- ^ "Central de Abasto: bomba de tiempo y nido de delincuencia". El Imparcial (Oaxaca). 9 May 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ^ Pabico, Alecks P. (2002). "Death of the Palengke". Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- ^ Napallacan, Jhunnex (28 March 2008). "6 Cebu rice retailers suspended for violations". Breaking News / Regions. Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Garcia, Bong (21 April 2007). "Food agency intensifies 'Palengke Watch'". Sun.Star Zamboanga. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Huang-Teves, Janette (7 September 2018). "Teves: Palengke Boy: The family's digital wet market buddy". Sun.Star. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Domingo, Katrina (26 March 2020). "Taking cue from Pasig, Valenzuela eyes own market-on-wheels amid quarantine". ABS-CBN. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Singapore wet markets: Reminder of bygone days". CNN. 22 June 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ United States. Foreign Agricultural Service. Dairy, Livestock, and Poultry Division, United States. World Agricultural Outlook Board (1992). U.S. Trade and Prospects: Dairy, livestock, and poultry products. The Service. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Trappey, Charles V. (1 March 1997). "Are Wet Markets Drying Up?". Taiwan Today. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ de Mooij, Marieke (2003). Consumer Behavior and Culture: Consequences for Global Marketing and Advertising. Chronicle Books. p. 295. ISBN 9780761926689.

- ^ a b c Yen, Bao (12 June 2017). "A Hanoi wet market at the crossroads of modernity". VnExpress. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ a b St. Cavendish, Christopher (11 March 2020). "No, China's fresh food markets did not cause coronavirus". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Bossons, Matthew (25 February 2020). "No, You Won't Find "Wild Animals" in Most of China's Wet Markets". RADII. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

External links

"Conservation (Environment), Wildlife (Environment), World news, China (News), Animal welfare (News), Food (impact of production on environment), Animals (News), Ethical and green living (Environment), Environment, Chinese food and drink, Asia Pacific (News)". The Guardian. London. 15 May 2009.