Kosovo

Template:Infobox Kosovo Kosovo (Serbian: Косово и Метохија, transliterated Kosovo i Metohija; also Космет, transliterated Kosmet; Albanian: Kosovë or Kosova) is a province in southern Serbia which has been under United Nations administration since 1999. While Serbia's nominal sovereignty is recognised by the international community, in practice Serbian governance in the province is virtually non-existent (see also Constitutional status of Kosovo). The province is governed by the United Nations Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) and the local Provisional Institutions of Self-Government, with security provided by the NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR).

Kosovo borders Montenegro, Albania and the Republic of Macedonia. The province's capital and largest city is Priština. Kosovo has a population of around two million people, predominantly ethnic Albanians, with smaller populations of Serbs, Turks, Bosniaks and other ethnic groups.

The province is the subject of a long-running political and territorial dispute between the Serbian (and previously, the Yugoslav) government and Kosovo's Albanian population. International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo (See Kosovo Status Process). According to many news media, it is widely expected that the negotiations will lead to some form of independence.[1][2][3][4] Russia, however, has suggested that it will use its veto in the UN Security Council if an agreement is not reached between Belgrade and Priština.[5]

Geography

With an area of 10,887 square kilometres[6] (4,203 sq. mi) and a population of over two million on the eve of the 1999 crisis, Kosovo borders Montenegro to the northwest, Central Serbia to the North and East, the Republic of Macedonia to the south and Albania to the southwest. The province's present borders were established in 1945. The republic of Serbia has one other autonomous province, Vojvodina, located in the far north of the country.

The largest cities are Priština, the capital, with an estimated 600,000 citizens, Prizren in the southwest with 165,000 citizens, Peć in the west with 154,000; then Kosovska Mitrovica in the north. Five other towns have populations in excess of 97,000. The climate in Kosovo is continental with warm summers and cold and snowy winters.

There are two main plains in Kosovo. The Metohija/Rrafshi i Dukagjinit basin is located in the western part of the province, and the Plain of Kosovo (Albanian: Rrafshi i Kosovës, Serbian: Kosovska Dolina) occupies the central area.

Much of Kosovo's terrain is rugged. The Šar Mountain is located in the south and south-east, bordering Macedonia. It is one of the region's most popular tourist and skiing resorts, with Brezovica and Prevalac/Prevallë as the main tourist centres. Kosovo's mountainous area, including the highest peak Ðeravica/Gjeravica (2656 m above sea level), is located in the south-west, bordering Albania and Montenegro.

The mountain range dividing Kosovo from Albania is known in English as the Cursed Mountains or Albanian Alps (Albanian: Bjeshkët e Nemuna, Serbian: Prokletije). The Kopaonik mountain is located in the north, bordering Central Serbia. The central region of Drenica, Carraleva/Crnoljevo and the eastern part of Kosovo, known as Gallap/Golak, are mainly hilly areas.

There are several notable rivers and lakes in Kosovo. The main rivers are the White Drin (running toward the Adriatic Sea, with the Erenik among its tributaries), Sitnica, South Morava in the Goljak area and Ibar in the north. The main lakes are Badovc in the north-east and Gazivoda in the north-western part.

History

see also: Demographic history of Kosovo

Ancient

The region of Kosovo has been inhabited by Illyrian tribes since the Bronze Age. In ancient times, the area was known as Dardania and was settled by a tribe with the same name. The south of Kosovo was ruled by Macedonia since Alexander the Great's reign in the 4th century BC. The local Dardani were of Illyrian stock. Illyrians resisted rule by the Greeks and Romans for centuries but after the long periods of conflict between Illyrian tribes and invading imperial powers, the region was eventually occupied by the Roman Empire under Emperor Augustus in 28 BC and became part of the Roman province of Moesia. After AD 85 it was part of Moesia Superior. Emperor Diocletian later c. 284 made Dardania into separate province with its capital at Naissus (Niš). Illyrians were among the first people to accept Christianity as they were evangelized by St. Paul himself. Illyria is twice mentioned in the Bible. When the Roman Empire split in A.D. 395, the area of Kosovo came under the Eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire. Many inhabitants of Dardania became leaders in Rome and Constantinopolis, including Justinian the Great.

Medieval

Great migrations and interregnums

Slavs came to the territories that form modern Kosovo in the seventh-century migrations of White Serbs, with the largest influx of migrants in the 630s; although the region was increasingly populated by Slavs since the sixth or even fifth century. These Slavs were Christianized in several waves between the seventh and ninth century, with the last wave taking place between 867 and 874. The northwestern part of Kosovo, Hvosno, became a part of the Byzantine Serb vassal state the Principality of Rascia, with Dostinik as the principality's capital.

In the late 800s, the whole of Kosovo was seized by the First Bulgarian Empire. Although Serbia restored control over Metohija throughout the tenth century, the rest of Kosovo was returned to the Byzantine Empire in a period of Bulgarian decline. However, Tsar Samuil of Bulgaria reconquered the whole of Kosovo in the late tenth century until the Byzantines restored their control over the area as they subjugated the Bulgarian Empire. In 1040-1041, Bulgarians, led by the Samuil of Bulgaria's grandson Petar Delyan staged a rebellion against the Eastern Roman Empire that temporarily encompassed Kosovo. After the rebellion was crushed, the Byzantine control over the region continued.

Throughout the following decades, numerous foreign peoples invading the Byzantine Empire stormed Kosovo, among them the Cumans.

In 1072, local Bulgarians, under George Voiteh, pushed a final attempt to restore Imperial Bulgarian power and invited the last heir of the House of Comitopuli - Duklja's prince Konstantin Bodin of the House of Vojislavljevic, son of the Serbian King Mihailo Voislav - to assume power. The Serbs decided to conquer the entire Byzantine region of Bulgaria. King Mihailo dispatched his son with three hundred elite Serb fighters led by Duke Petrilo. Constantine Bodin was crowned in Prizren as Petar III, Tsar of the Bulgarians by George Voiteh and the Slavic Boyars. The Empire swept across Byzantine territories in months, until the significant losses on the south had forced Czar Petar to withdraw. In 1073, the Byzantine forces chased Constantine Bodin, defeated his army at Pauni, and imprisoned him.

Incorporation into Serbia

The full Serbian takeover was carried out under a branch of the House of Voislav Grand Princes of Rascia. In 1093, Prince Vukan advanced on Lipljan, burned it down and raided the neighbouring areas. The Byzantine Emperor himself came to Zvečan for negotiations. Zvečan served as the Byzantine line-of-defence against constant invasions from the neighboring Serbs. A peace agreement was made, but Vukan broke it and defeated the army of John Comnenus, the Emperor's nephew. Vukan's armies stormed Kosovo. In 1094, Byzantine Emperor Alexius attempted to renew peace negotiations in Ulpiana. A new peace agreement was concluded and Vukan handed over hostages to the Emperor, including his two nephews Uroš and Stefan Vukan. Prince Vukan renewed the conflict in 1106, once again defeating John Comnenus's army. However, his death halted the total Serb conquest of Kosovo.

In 1166, a Serbian nobleman from Zeta, Stefan Nemanja, the founder of the House of Nemanja ascended to the Rascian Grand Princely throne and conquered most of Kosovo, in an uprising against the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I Comnenus. He defeated the previous Grand Prince of Rascia Tihomir's army at Pantino, near Pauni. Tihomir, who was Stefan's brother, was drowned in the Sitnica river. Stefan was eventually defeated and had to return some of his conquests. He pledged to the Emperor that he would not renew hostilities, but in 1183, Stefan Nemanja embarked on a new offensive with the Hungarians after the death of Manuel I Comnenus in 1180, marking the end of Byzantine domination of Kosovo.

Nemanja's son, Stefan II, recorded that the border of the Serbian realm reached the river of Lab. Grand Prince Stephen II completed the inclusion of the Kosovo territories under Serb rule in 1208, by which time he had conquered Prizren and Lipljan, and moved the border of territory under his control to the Šar mountain.

Kingdom of the Serbs

In 1217, the Serbian Kingdom achieved recognition. In 1219, an autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church was created, with Hvosno, Prizren and Lipljan being the Orthodox Christian Episcopates on Kosovo. By the end of the 13th century, the centre of the Serbian Church was moved to Peć from Žiča.

In the thirteenth century, Kosovo became the heart of the Serbian political and religious life, with the Šar mountain becoming the political center of the Serbian rulers. The main chatteu was in Pauni. On an island was Svrčin, and on the coast Štimlji, and in the mountains was the Castle of Nerodimlje. The Complexes were used for counciling, crowning of rulers, negotiating, and as the rulers' living quarters. After 1291, the Tartars broke all the way to Peć. Serbian King Stefan Milutin managed to defeat them and then chase them further. He raised the Temple of the Mother of Christ of Ljeviška in Prizren around 1307, which became the seat of the Prizren Bishopric, and the magnificent Gračanica monastery in 1335, the seat of the Lipljan Bishopric. In 1331, the juvenile King Dušan attacked his father, Serbian King Stefan of Dechani at his castle in Nerodimlje. King Stefan closed in his neighbouring fortress of Petrič, but Dušan captured him and closed him with his second wife Maria Palaiologos and their children in Zvečan, where the dethroned King died on 11 November 1331.

In 1327 and 1328, Serbian King Stefan of Dechani started forming the vast Dečani domain, although, Serbian King Dušan would finish it in 1335. Stefan of Dechani issued the Dechani Charter in 1330, listing every single citizen in every household under the Church Land's demesne.

Serbian Empire and Despotate

King Stefan Dušan founded the vast Monastery of Saint Archangel near Prizren in 1342–1352. The Kingdom was transformed into an Empire in 1345 and officially in 1346. Stefan Dušan received John VI Cantacuzenus in 1342 in his Castle in Pauni to discuss a joint War against the Byzantine Emperor. In 1346, the Serbian Archepiscopric at Peć was upgraded into a Patriarchate, but it was not recognized before 1370.

After the Empire fell into disarray prior to Dušan's death in 1355, feudal anarchy caught up with the country during the reign of Tsar Stefan Uroš V. Kosovo became a domain of the House of Mrnjavčević, but Prince Voislav Voinović expanded his demesne further into Kosovo. The armies of King Vukašin Mrnjavčević from Pristina and his allies defeated Voislav's forces in 1369, putting a halt to his advances. After the Battle of Marica on 26 September 1371, in which the Mrnjavčević brothers lost their lives, Đurađ I Balšić of Zeta took Prizren and Peć in 1372. A part of Kosovo became the demesne of the House of Lazarević.

The Ottomans invaded and met the Christian coalition of Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs under Prince Lazar on 28 June 1389, near Pristina, at Gazi Mestan. The Serbian Army was assisted by various allies. The epic Battle of Kosovo followed, in which Prince Lazar himself lost his life. Prince Lazar amassed 70,000 men on the battlefield and the Ottomans had 140,000. Through the cunning of Miloš Obilić, Sultan Murad was murdered and the new Sultan Beyazid had, despite winning the battle, to retreat to consolidate his power. The Ottoman Sultan was buried with one of his sons at Gazi Mestan. Both Prince Lazar and Miloš Obilić were canonised by the Serbian Orthodox Church for their efforts in the battle. The local House of Branković came to prominence as the local lords of Kosovo, under Vuk Branković, with the temporary fall of the Serbian Despotate in 1439. Another great battle occurred between the Hungarian troops supported by the Albanian ruler Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg on one side, and Ottoman troops supported by the Brankovićs in 1448. Skanderbeg's troops that were going to help John Hunyadi were stopped by the Serb forces of Branković. Brankovic, as vassal to the Ottomans, was obligated to fight on their side against the Christian armies from Albania and Hungary. Hungarian King John Hunyadi lost the battle after a two-day fight, but essentially stopped the Ottoman advance northwards. Kosovo then became vassalaged to the Ottoman Empire, until its direct incorporation after the final fall of Serbia in 1459.

In 1455, new castles rose to prominence in Priština and Vučitrn, centres of the Ottoman vassalaged House of Branković.

Ottoman rule

The Ottomans brought Islamisation with them, particularly in towns, and later also created the Vilayet of Kosovo as one of the Ottoman territorial entities. Kosovo was taken by the Austrian forces during the Great War of 1683–1699 with help of 5,000 Albanians and their leader, a Catholic Archbishop Pjetër Bogdani. In 1690, the Serbian Patriarch of Peć Arsenije III, who previously escaped a certain death, led 37,000 families from Kosovo, to evade Ottoman wrath since Kosovo had just been retaken by the Ottomans. The people that followed him were mostly Serbs and Albanians abandoned—but they were likely followed by other ethnic groups. Due to the oppression from the Ottomans, other migrations of Orthodox people from the Kosovo area continued throughout the 18th century. It is also noted that some Serbs adopted Islam, while some even gradually fused with other groups, predominantly Albanians, adopting their culture and even language.

In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the Patriarchate of Peć and the position of Christians in Kosovo was greatly reduced. All previous privileges were lost, and the Christian population had to suffer the full weight of the Empire's extensive and losing wars, even having blame forced upon them for the losses.

Modern

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (February 2007) |

In 1871, a massive Serbian meeting was held in Prizren at which the possible retaking and reintegration of Kosovo and the rest of "Old Serbia" was discussed, as the Principality of Serbia itself had already made plans for expansions towards Ottoman territory.

Albanian refugees from the territories conquered in the 1876–1877 Serbo-Turkish war and the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish war are now known as 'muhaxher' (which means 'refugee', from Arabic muhajir). Their descendants still have the same surname, Muhaxheri. It is estimated that 200,000 to 400,000 Serbs were cleansed out of the Vilayet of Kosovo between 1876 and 1912, especially during the Greek-Ottoman War in 1897.

In 1878, a Peace Accord was drawn that left the cities of Priština and Kosovska Mitrovica under civil Serbian control, and outside the juristiction of the Ottoman authorities, while the rest of Kosovo would be under Ottoman control. As a response, the Albanians formed the nationalistic and conservative League of Prizren in Prizren later the same year. Over three hundred Albanian leaders from Kosovo and western Macedonia gathered and discussed the urgent issues concerning protection of Albanian populated regions from division among neighbouring countries. The League was supported by the Ottoman Sultan because of its Pan-Islamic ideology and political aspirations of a unified Albanian people under the Ottoman umbrella. The movement gradually became anti-Christian and spread great anxiety among Christian Albanians and especially among Christian Serbs. As a result, more and more Serbs left Kosovo northwards. Serbia complained to the World Powers that the promised territories were not being held[clarification needed] because the Ottomans were hesitating to do that. The World Powers put pressure on the Ottomans and in 1881, the Ottoman Army began fighting the Albanian forces. The Prizren League created a Provisional Government with a President, Prime Minister (Ymer Prizreni) and Ministries of War (Sylejman Vokshi) and Foreign Ministry (Abdyl Frashëri). After three years of war, the Albanians were defeated. Many of the leaders were executed and imprisoned. The subsequent Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 restored most Albanian lands to Ottoman control, but the Serbian forces had to retreat from Kosovo along with some Serbs that were expelled as well[citation needed]. By the end of the 19th century the Albanians replaced the Serbs as the dominant people in Kosovo.

In 1908, the Sultan brought a new democratic decrete that was valid only for Turkish-speakers. As the vast majority of Kosovo spoke Albanian or Serbian, the Kosovar population was very unhappy. The Young Turk movement supported a centralist rule and opposed any sort of autonomy desired by Kosovars, and particularely the Albanians. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Priština and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June of 1911. The Aim of the League of Prizren was to unite the four Albanian Vilayets by merging the majority of Albanian inhabitants within the Ottoman Empire into one Albanian State. However, at that time Serbs have consisted about 25% of the whole Vilayet of Kosovo's overall population and were opposing the Albanian rule along with Turks and other Slavs in Kosovo, which disabled the Albanian movements to occupy Kosovo.

In 1912, during the Balkan Wars, most of Kosovo was taken by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the region of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjini Valley) was taken by the Kingdom of Montenegro. An exodus of the local Albanian population occurred. This is best described by Leon Trotsky, who was a reporter for the Pravda newspaper at the time. The Serbian authorities planned a recolonization of Kosovo.[7] Numerous colonist Serb families moved-in to Kosovo, equalizing the demographic balance between Albanians and Serbs. Many Albanians fled into the mountains and numerous Albanian and Turkish houses were razed. The reconquest of Kosovo was noted as a vengeance for the 1389 Battle of Kossovo. At the Conference of Ambassadors in London in 1912 presided over by Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary, the Kingdoms of Serbia and Montenegro were acknowledged sovereignty over Kosovo.

In the winter of 1915–1916, during World War I, Kosovo saw a large exodus of Serbian army which became known as the Great Serbian Retreat. Defeated and worn out in battles against Austro-Hungarians, they had no other choice than to retreat, as Kosovo was occupied by Bulgarians and Austro-Hungarians. The Albanians joined and supported the Central Powers. As opposed to Serbian schools, numerous Albanian schools were opened during the 'occupation' (the majority Albanian population considered it a liberation). Allied ships were awaiting for Serbian people and soldiers at the banks of the Adriatic sea and the path leading them there went across Kosovo and Albania. Tens of thousands of soldiers have died of starvation, extreme weather and Albanian reprisals as they were approaching the Allies in Corfu and Thessaloniki, amassing a total of 100,000 dead retreaters.[citation needed] Transported away from the front lines, Serbian army managed to heal many wounded and ill soldiers and get some rest. Refreshed and regrouped, it decided to return to the battlefield. In 1918, the Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of Kosovo. During liberation of Kosovo, the Serbian Army committed atrocities against the population in revenge. [citation needed] Serbian Kosovo was unified with Montenegrin Metohija as Montenegro subsequently joined the Kingdom of Serbia. After the World War I ended, the Monarchy was then transformed into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians (Albanian: Mbretëria Serbe, Kroate, Sllovene, Serbo-Croatian: Kraljevina Srba, Hrvata i Slovenaca) on 1 December 1918, gathering territories gained in victory.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II

The 1918–1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians witnessed a raise of the Serbian population in the region and a decline in the non-Serbian. In the Kingdom Kosovo was split onto four counties—three being a part of the entity of Serbia: Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija; and one of Montenegro: northern Metohija. However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Areas of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta. In 1921 the Albanian elite lodged an official protest of the government to the League of Nations, claiming that 12,000 Albanians had been killed and over 22,000 imprisoned since 1918 and seeking a unification of Albanian-populated lands. As a result, an armed Kachak resistance movement was formed whose main goal was to unite Albanian-populated areas of the Kingdom to Albania.

In 1929, the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The territories of Kosovo were split among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of 1941.

The greatest part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Fascist Albania, and smaller bits by the Tsardom of Bulgaria and Nazi German-occupied Kingdom of Serbia. During the fascist occupation of Kosovo by Albanians, until August 1941 alone, over 10,000 Serbs were killed and between 80,000 and 100,000 Serbs were expelled, while roughly the same number of Albanians from Albania were brought to settle in these Serbian lands. [8]

Mustafa Kruja, the Prime Minister of Albania, was in Kosovo in June 1942, and at a meeting with the Albanian leaders of Kosovo, he said: "We should endeavor to ensure that the Serb population of Kosovo be – the area be cleansed of them and all Serbs who had been living there for centuries should be termed colonialists and sent to concentration camps in Albania. The Serb settlers should be killed." [9][10]

Prior to the surrender of Fascist Italy in 1943, the German forces took over direct control of the region. After numerous uprisings of Partisans led by Fadil Hoxha, Kosovo was liberated after 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Kosovo in the second Yugoslavia

The province was first formed in 1945 as the Autonomous Kosovo-Metohian Area to protect[citation needed] its regional Albanian majority within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito, but with no factual autonomy. After Yugoslavia's name change to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1953, Kosovo gained inner autonomy in the 1960s. In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received higher powers, including the highest governmental titles — President and Premier and a seat in the Federal Presidency which made it a de facto Socialist Republic within the Federation, but remaining as a Socialist Autonomous Province within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. Tito had pursued a policy of weakening Serbia, as he believed that a "Weak Serbia equals a strong Yugoslavia". To this end Vojvodina and Kosovo became autonomous regions and were given the above entitled privileges as defacto republics.[citation needed] Serbo-Croatian, Albanian and Turkish were defined as official languages on the provincial level marking the two largest linguistic Kosovan groups: Albanians and Serbs. In the 1970s, an Albanian nationalist movement pursued full recognition of the Province of Kosovo as another Republic within the Federation, while the most extreme elements aimed for full-scale independence. Tito's arbitrary regime dealt with the situation swiftly, but only giving it a temporary solution. The ethnic balance of Kosovo witnessed unproportional increase as the number of Albanians tripled gradually rising from almost 75% to over 90%, but the number of Serbs barely increased and dropped in the full share of the total population from some 15% down to 8%. Even though Kosovo was the least developed area of the former Yugoslavia, the living and economic prospects and freedoms were far greater then under the totalitarian Maoist regieme in Albania.

Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students organized protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia. Those protests rapidly escalated into violent riots "involving 20,000 people in six cities"[11] that were harshly contained by the Yugoslav government. During the 1980s, ethnic tensions continued with frequent violent outbreaks against Serbs and Yugoslav state authorities resulting in increased emigration of Kosovo Serbs and other ethnic groups.[12][13] The Yugoslav leadership tried to suppress protests of Kosovo Serbs seeking protection from ethnic discrimination and violence.[14]

In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts (SANU) was working on a document which later would be known as the SANU Memorandum, a warning to the Serbian President and Assembly of the existing crisis and where it would lead. An unfinished edition was filtered to the press. In the essay, SANU criticised the state of Yugoslavia and made remarks that the only member state contributing at the time to the development of Kosovo and Macedonia (by then, the poorest territories of the Federation) was Serbia. According to SANU, Yugoslavia was suffering from ethnic strife and the disintegration of the Yugoslav economy into separate economic sectors and territories, which was transforming the federal state into a loose confederation.[15] On the other hand, some think that Slobodan Milošević used the discontent reflected in the SANU memorandum for his own political goals, during his rise to power in Serbia at the time.[16],

Milošević was initially sent there as a member of the Communists party . Initially Milošević did not talk to the Serbian nationalists who were at that point demonstrating for rights and freedoms that had been denied to them. During these meetings he agreed to listen to their grievances. During the meeting, outside the building where this forum was taking place police started fighting the locals who had gathered there, mostly Serbs eager to voice their grievances. After hearing about the police brutality outside of the halls, Milošević came out and in an emotional moment promised the local sebs that "Nobody would beat yo again." This news byte was then seen on evening news that catapulted then an unknown Milošević to the forefront of the current debate about the problems on Kosovo.

Since the 1974 Constitution, the Albanian controlled Kosovo communist officials in Kosovo had instituted a campaign of discrimination against non-Albanians, Serbs and other non-Albanians like the Roma, Turks and Macedonians, were fired from jobs and positions within the regional government apparatus[citation needed]. These repressions and grievances had been swept conveniently under the rug with the pretense of "Brotherhood and Unity" policy instituted by then already late Josip Broz Tito. Any reasoning to the contradictory, was quickly silenced. To the party leaderships chagrin, Mr. Milošević insisted on finding a solution for the Kosovo situation, he was quickly labeled as a reactionary[citation needed].

In order to save his skin, Milošević fought back and established a political coup d'etat. He gained effective leadership and control of the Serbian Communist party and pressed forward with the one issue that had catapulted him to the forefront of the political limelight, which was Kosovo. This By the end of the 1980s, calls for increased federal control in the crisis-torn autonomous province were getting louder. Slobodan Milošević pushed for constitutional change amounting to suspension of autonomy for both Kosovo and Vojvodina.[17]

Kosovo and the breakup of Yugoslavia

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. In particular, Kosovo's ethnic Serb community, a minority of Kosovo population, complained about mistreatment from the Albanian majority. Milosevic capitalized on this discontent to consolidate his own position in Serbia. In 1987, Serbian President Ivan Stambolić sent Milošević to Kosovo to "pacify restive Serbs in Kosovo." On that trip, Milošević broke away from a meeting with ethnic Albanians to mingle with angry Serbians in a suburb of Pristina. As the Serbs protested they were being pushed back by police with batons, Milošević told them, "No one is allowed to beat you."[18] This incident was later seen as pivotal to Milošević's rise to power. [citation needed]

On June 28, 1989, Milošević delivered a speech in front of a large number of Serb citizens at the main celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, held at Gazimestan. Many think that this speech helped Milošević consolidate his authority in Serbia.[19]

In 1989, Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political maneuvering, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia. Soon thereafter Kosovo Albanians organized a non-violent separatist movement, employing widespread civil disobedience, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo. Kosovo Albanians boycotted state institutions and elections and established separate Albanian schools and political institutions. On July 2 1990, an unconstitutional Kosovo parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, although this was not recognized by Belgrade or any foreign states. Two years later, in 1992, the parliament organized an unofficial referendum which was observed by international organizations but was not recognized internationally. With an 80% turnout, 98% voted for Kosovo to be independent.

Kosovo War

One of the events that contributed to Milošević's rise of power was the Gazimestan Speech, delivered in front of 100,000 Serb citizens at the central celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo, held at Gazimestan on 28 June, 1989. Soon afterwards the autonomy of Kosovo was reduced. After Slovenia's secession from Yugoslavia in 1991, Milošević used the seat to attain dominance over the Federal government, outvoting his opponents.

Albanians organized a peaceful separatist movement. State institutions and elections were boycotted and separate Albanian schools and political institutions were established. On July 2, 1990 Kosovo Parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, this was only recognized by Albania. In September of that year, the parliament, meeting in secrecy in the town of Kačanik, adopted the Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo. Two years later, in 1992, the parliament organized an unofficial referendum which was observed by international organisations but was not recognized internationally. With an 80% turnout, 98% voted for Kosovo to be independent.

With the events in Bosnia and Croatia coming to an end, the Serb government started relocating Serbian refugees from Croatia and Bosnia all over Serbia, including in Kosovo. In a number of cases, Albanian families were expelled from their apartments to make room for the refugees[citation needed].

After the Dayton Agreement in 1995, some Albanians organized into the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), employing guerilla-style tactics against Serbian police forces and civilians. Violence escalated in a series of KLA attacks and Serbian reprisals into the year 1999, with increasing numbers of civilian victims. In 1998 western interest increased and the Serbian authorities was forced to sign a unilateral cease-fire and partial retreat. Under an agreement led by Richard Holbrooke, OSCE observers moved into Kosovo to monitor the ceasefire, while Yugoslav military forces partly pulled out of Kosovo. However, the ceasefire was systematically broken shortly thereafter by KLA forces, which again provoked harsh counterattacks by the Serbs. On 16 January 1999, the bodies of 45 Albanian civilians were found in the town of Racak. The victims had been executed by Serb forces [20][21]. The so-called Racak Massacre was instrumental in increasing the pressure on Serbia in the following conference at Rambouillet. After more than a month of negotations Yugoslavia refused to sign the prepared agreement, primarily, it has beeen argued, because of a clause giving NATO forces access rights to not only Kosovo but to all of Yugoslavia (which the Yugoslav side saw as tantamount to military occupation).

This triggered a 78-day NATO campaign in 1999. At first limited to military targets in Kosovo proper, the bombing campaign was soon extended to cover targets all over Yugoslavia, including bridges, power stations, factories, broadcasting stations, post offices, and various government buildings.

During the conflict roughly a million ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo, several thousand were killed (the numbers and the ethnic distribution of the casualties are uncertain and highly disputed). An estimated 10,000-12,000 ethnic Albanians and 3,000 Serbs are believed to have been killed during the conflict. Some 3,000 people are still missing, of which 2,500 are Albanian, 400 Serbs and 100 Roma.[22]

Women even though they were not combatants experienced many atrocities during Kosovo war, especially Albanian women. Serbian army and police who had used rape as a weapon during the war in Bosnia, used rape also in Kosovo and the intention was to weaken the morale of Albanians. It is believed some 20,000 Albanian women were raped during the Kosovo war, but since rapes are associated with shame, many women after reporting this to different international humanitarian organizations have kept it secret. Some of the raped women have committed suicide after the war [23] [24] .

Some of the worst massacres against civilian Albanians occurred after that NATO started the bombing of Yugoslavia. Cuska massacre[25], Podujevo massacre [26], Velika Krusa massacre[27] are some of the massacres committed by Serbian army, police and paramilitary.

During the Kosovo War, Serbs also engaged in a deliberate campaign of cultural destruction and rampage. According to a report compiled by the Kosovo Cultural Heritage Project, Serbian forces tried to wipe out all Albanian culture and traditions. Of the 500 mosques that were in use prior to the war, 200 of them were completely destroyed or desecrated. The report concludes that most mosques were deliberately set on fire with no sign of fighting around the area. Among numerous other things, the following important objects were destroyed because they represented Albanian as well as Muslim and Catholic cultures:

Sinan Pasha Mosque in Prizren, the Prizren League Museum, the Hadum Mosque complex in Đakovica; the historic bazaars in Đakovica and Peć (Albanian: Peja); the Roman Catholic church of St. Anthony in Đakovica; and two old Ottoman bridges, Ura e Terzive (Terzijski most) and Ura e Tabakeve (Tabacki most), near Đakovica.[28]

Kosovo after the war

After the war ended, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1244 that placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorized KFOR, a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Almost immediately returning Kosovo Albanians attacked Kosovo Serbs [1], causing some 200,000-280,000[29] Serbs and other non-Albanians[30] to flee (note: the current number of internally displaced persons is disputed,[31][32][33][34] with estimates ranging from 65,000[35] to 250,000[36][37][38]). Many displaced Serbs are afraid to return to their homes, even with UNMIK protection. Around 120,000-150,000 Serbs remain in Kosovo, but are subject to ongoing harassment and discrimination.

In 2001, UNMIK promulgated a Constitutional Framework for Kosovo that established the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG), including an elected Kosovo Assembly, Presidency and office of Prime Minister. Kosovo held its first free, Kosovo-wide elections in late 2001 (municipal elections had been held the previous year). UNMIK oversaw the establishment of a professional, multi-ethnic Kosovo Police Service.

In March 2004, Kosovo experienced its worst inter-ethnic violence since the Kosovo War. The unrest in 2004 was sparked by a series of minor events that soon cascaded into large-scale riots. Kosovo Albanians mobs burned hundreds of Serbian houses, Serbian Orthodox Church sites (including some medieval churches and monasteries) and UN facilities. Kosovo Police established a special investigation team to handle cases related to the 2004 unrest and according to Kosovo Judicial Council by the end of 2006 the 326 charges filed by municipal and district prosecutors for criminal offenses in connection with the unrest had resulted in 200 indictments: convictions in 134 cases, and courts acquitted eight and dismissed 28; 30 cases were pending. International prosecutors and judges handled the most sensitive cases[39].

Politics and governance

|

|---|

| Constitution and law |

UN Security Council Resolution 1244 placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration pending a determination of Kosovo's future status. This Resolution entrusted the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) with sweeping powers to govern Kosovo, but also directed UNMIK to establish interim institutions of self-governance. Resolution 1244 permits Serbia no role in governing Kosovo and since 1999 Serbian laws and institutions have not been valid in Kosovo. NATO has a separate mandate to provide for a safe and secure environment.

In May 2001, UNMIK promulgated the Constitutional Framework, which established Kosovo's Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG). Since 2001, UNMIK has been gradually transferring increased governing competencies to the PISG, while reserving some powers that are normally carried out by sovereign states, such as foreign affairs. Kosovo has also established municipal government and an internationally-supervised Kosovo Police Service.

According to the Constitutional Framework, Kosovo shall have a 120-member Kosovo Assembly. The Assembly includes twenty reserved seats: ten for Kosovo Serbs and ten for non-Serb minorities (Bosniaks, Roma, etc.). The Kosovo Assembly is responsible for electing a President and Prime Minister of Kosovo.

The largest political party in Kosovo, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), has its origins in the 1990s non-violent resistance movement to Milosevic's rule. The party was led by Ibrahim Rugova until his death in 2006. The two next largest parties have their roots in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA): the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) led by former KLA leader Hashim Thaci and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) led by former KLA commander Ramush Haradinaj. Kosovo publisher Veton Surroi formed his own political party in 2004 named "Ora." Kosovo Serbs formed the Serb List for Kosovo and Metohija (SLKM) in 2004, but have boycotted Kosovo's institutions and never taken their seats in the Kosovo Assembly.

In November 2001, the OSCE supervised the first elections for the Kosovo Assembly. After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and elected Ibrahim Rugova as President and Bajram Rexhepi (PDK) as Prime Minister.

After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted in Ramush Haradinaj (AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused the current government of corruption.

Ramush Haradinaj resigned the post of Prime Minister after he was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in March 2005. He was replaced by Bajram Kosumi (AAK). But in a political shake-up after the death of President Rugova in January 2006, Kosumi himself was replaced by former Kosovo Protection Corps commander Agim Ceku. Ceku has won recognition for his outreach to minorities, but Serbia has been critical of his wartime past as military leader of the KLA and claims he is still not doing enough for Kosovo Serbs. The Kosovo Assembly elected Fatmir Sejdiu, a former LDK parliamentarian, president after Rugova's death. Slaviša Petkovic, Minister for Communities and Returns, was previously the only ethnic Serb in the government, but resigned in November 2006 amid allegations that he misused ministry funds.[40][41]. Today two of the total thirteen ministries in Kosovo's Government have ministers from the minorities. Branislav Grbic, ethnic Serb, leads Minister of Returns and Sadik Idriz, ethnic Bosnjak, leads Ministry of Health [42]

Kosovo Status Process

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (April 2007) |

A UN-led political process began in late 2005 to determine Kosovo's future status. Belgrade has proposed that Kosovo be highly autonomous and remain a part of Serbia — Belgrade officials have repeatedly said that an imposition of Kosovo's independence would be a violation of Serbia's sovereignty and therefore contrary to international law. Pristina asserts that Kosovo should become independent, arguing that the violence of the Milosevic years has made continued union between Kosovo and Serbia not viable. The Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) has counseled the government and political leadership of Kosovo during the final status negotiations.

UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, former president of Finland, leads the status process; Austrian diplomat Albert Rohan is his deputy. Ahtisaari's office — the UN Office of the Special Envoy for Kosovo (UNOSEK) — is located in Vienna and includes liaison staff from NATO, the EU and the United States.

On February 2, 2007, UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari delivered to Belgrade and Pristina leaders a draft status settlement proposal. The proposal covered a wide range of issues related to Kosovo's future, in particular measures to protect Kosovo's non-Albanian communities such as decentralization of government, protection of Serbian Orthodox Church heritage and institutional protections for non-Albanian communities. While not mentioning the word "independence," the draft included several provisions that were widely interpreted as implying statehood for Kosovo. In particular, the draft Settlement would give Kosovo the right to apply for membership in international organizations, create a Kosovo Security Force and adopt national symbols.[43] Ahtisaari conducted several weeks of consultations with the parties in Vienna to finalize the Settlement, including a high-level meeting on March 10 that brought together the Presidents and Prime Ministers of both sides. After this meeting, leaders from both sides signaled a total unwillingness to compromise on their central demands (Pristina for Kosovo's independence; Belgrade for sovereignty over Kosovo). Concluding that there was no chance for the two sides to reconcile their positions, Ahtisaari said he would submit to the UN Security Council his own proposed status arrangements, including an explicit recommendation for the status outcome itself, by the end of March.[44]

Most international observers believe these negotiations will lead to Kosovo's independence, subject to a period of international supervision.[45] Nevertheless, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated in September 2006 that Russia may veto a UN Security Council proposal on Kosovo's final status that applies different standards than those applied to the separatist Georgian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.[46] The Russian ambassador to Serbia has asserted that Russia will use its veto power unless the solution is acceptable to both Belgrade and Priština.[47]

In a survey carried out by UNDP and published in March 2007, 96 % of Kosovo Albanians and 77 % of non- Serb minorities in Kosovo wants Kosovo to become independent within present borders. 78 % of the Serb minority wants Kosovo to be an autonomous province within Serbia. Only 2.5 % of the Albanians want unification with Albania[48].

The Contact Group has said that regardless of status outcome a new International Civilian Office (ICO) will be established in Kosovo to supervise the implementation status settlement and safeguard minority rights. NATO leaders have said that KFOR will be maintained in Kosovo after the status settlement. The EU will establish a European Security and Defense Policy Rule of Law mission to focus on the police/justice sectors.

Economy

Kosovo has one of the most under-developed economies in Europe, with a per capita income estimated at €1,565 (2004).[49] Despite substantial development subsidies from all Yugoslav republics, Kosovo was the poorest province of Yugoslavia.[50] Additionally, over the course of the 1990s a blend of poor economic policies, international sanctions, poor external commerce and ethnic conflict severely damaged the economy.[51]

Kosovo's economy remains weak. After a jump in 2000 and 2001, growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was negative in 2002 and 2003 and is expected to be around 3 percent 2004-2005, with domestic sources of growth unable to compensate for the declining foreign assistance. Inflation is low, while the budget posted a deficit for the first time in 2004. Kosovo has high external deficits. In 2004, the deficit of the balance of goods and services was close to 70 percent of GDP. Remittances from Kosovars living abroad accounts for an estimated 13 percent of GDP, and foreign assistance for around 34 percent of GDP.[52]

Most economic development since 1999 has taken place in the trade, retail and the construction sectors. The private sector that has emerged since 1999 is mainly small-scale. The industrial sector remains weak and the electric power supply remains unreliable, acting as a key constraint. Unemployment remains pervasive, at around 40-50% of the labor force.[53][54]

UNMIK introduced de-facto an external trade regime and customs administration on September 3, 1999 when it set customs border controls in Kosovo. All goods imported in Kosovo face a flat 10% customs duty fee.[55] These taxes are collected from all Tax Collection Points installed at the borders of Kosovo, including those between Kosovo and Serbia.[56] UNMIK and Kosovo institutions have signed Free Trade Agreements with Croatia,[57] Bosnia and Herzegovina,[58] Albania[59] and Macedonia.[60]

Macedonia is Kosovo's largest import and export market (averaging €220 million and €9 million, respectively), followed by Serbia-Montenegro (€111 million and €5 million), Germany and Turkey.[61]

The Euro is the official currency of Kosovo and used by UNMIK and the government bodies.[62] The Serbian Dinar is used in the Serbian populated parts.

The economy is hindered by Kosovo's still-unresolved international status, which has made it difficult to attract investment and loans.[63] The province's economic weakness has produced a thriving black economy in which smuggled petrol, cigarettes and cement are major commodities. The prevalence of official corruption and the pervasive influence of organised crime gangs has caused serious concern internationally. The United Nations has made the fight against corruption and organised crime a high priority, pledging a "zero tolerance" approach.[64]

Demographics

According to the Kosovo in Figures 2005 Survey of the Statistical Office of Kosovo,[65][66][67] Kosovo's total population is estimated between 1.9 and 2.2 million in the following ethnic proportions. The estimate from 2000-2002-2003 goes (a 1,900,000 strong population):

- 90% Albanians

- 5% Serbs

- 3% Muslims (Bosniaks and Gorans)

- 1% Roma (see also Roma in Mitrovica Camps)

- 1% Turks

However, the figures are highly disputable. Some estimates are that there is an Albanian majority well above 90 percent. The population census is set to take place in the near future. Others give much higher figures for Roma and Turks.[68][69] The majority of the Albanians in Kosovo are Muslims[70], and most Serbs are Serbian Orthodox. About 3% of Kosovo's population are Catholics, and a small population of Atheist and Agnostics. [71]

Administrative divisions

Kosovo is divided into seven districts:

- Priština/Prishtina District

- Prizren/Prizreni District

- Peć/Peja District

- Uroševac/Ferizaji District

- Đakovica/Gjakova District

- Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovica District

- Gnjilane/Gjilani District

North Kosovo maintains its own government, infrastructure and institutions by its dominant ethnic Serb population in the Mitrovica District, viz. in the Leposavic, Zvecan and Zubin Potok municipalities and the northern part of Kosovska Mitrovica.

Cities

List of largest cities in Kosovo (with population figures in 2006):[72]

- Priština/Prishtina (562,686)

- Prizren/Prizreni (165,229)

- Uroševac/Ferizaji (97,741)

- Đakovica/Gjakova (97,156)

- Peć/Peja (95,190)

- Gnjilane/Gjilani (91,595)

- Kosovska Mitrovica/Mitrovica (86,359)

- Podujevo/Podujeva (48,526)

Culture

Music

Music has always been a part of the Albanian and Serbian culture. Although in Kosovo music is diverse (as it got mixed with the cultures of different regimes dominating in Kosovo), authentic Albanian music (see World Music) and Serbian music do still exist. The Albanian one is characterized by use of çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolin, mandola and percussion. In Kosovo, along with modern music, folk music is very popular. There are many folk singers and ensembles (both Albanian and Serbian). Classical music is also well known in Kosovo and has been taught at universities (at the University of Prishtina Faculty of Arts and the University of Priština at Kosovska Mitrovica Faculty of Arts) and several pre-college music schools The modern music in Kosovo has its origin from the Western countries. The main modern genres include: Pop, Hip Hop, Rock and Jazz. The most notable rock bands are: Gjurmët, Troja, Votra, Diadema, Humus, Asgjë sikur Dielli, Kthjellu, Cute Babulja, Babilon, etc. Ilir Bajri is a notable jazz and electronic musician. Most notable hip-hop performers are the rap-group called NR (urbaNRoots) who also introduced a new type of rap different to the G-Funk that was widely spread before. Other hip-hop artists include Unikkatil (who lives in the USA but represents Kosovo), Tingulli 3, Ritmi I Rrugës, Mad Lion, K-OS and many more.

Leonora Jakupi and Adelina Ismajli are two of the most popular commercial singers in Kosovo today. | There are some notable music festivals in Kosovo:

- Rock për Rock - contains rock and metal music

- Polifest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, unusually rock and never metal)

- Showfest - contains all kinds of genres (usually hip hop, commercial pop, unusually rock and never metal)

- Videofest - contains all kinds of genres

- Kush Këndon Lutet Dy Herë - contains christian music

- North City Jazz & Blues festival, an international music festival held annually in Zvecan

Kosovo Radiotelevisions like RTK, 21 and KTV have their musical charts.

List of Presidents

- Ibrahim Rugova, 4 March 2002 - 21 January 2006

- Fatmir Sejdiu, 10 February 2006 - present

Gallery

-

Kosovo Albanian ethnic costume/dance.

-

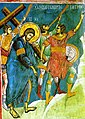

Christ Carrying the Cross, a fresco from Visoki Dečani.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

References

- ^ "Kosovo's status - the wheels grind on", The Economist, October 6, 2005.

- ^ "A province prepares to depart", The Economist, November 2, 2006.

- ^ "Kosovo May Soon Be Free of Serbia, but Not of Supervision", by Nicholas Wood, The New York Times, November 2, 2006.

- ^ "Serbia shrinks, and sinks into dejection", by WILLIAM J. KOLE, The Associated Press, November 19, 2006.

- ^ "Russia threatens veto over Kosovo", BBC News, April 24, 2007.

- ^ Административно територијална подела Републике Србије на покрајине, округе, општине и Град Београд

- ^ Elsie, R. (ed.) (2002): "Gathering Clouds. The roots of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. Early twentieth-century documents". Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peć (Kosovo, Serbia). ISBN 9951-05-016-6

- ^ Krizman, Serge. "Massacre of the innocent Serbian population, committed in Yugoslavia by the Axis and its Satellite from April 1941 to August 1941". Map. Maps of Yugoslavia at War, Washington, 1943

- ^ Bogdanović, Dimitrije. "The Book on Kosovo". 1990. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1985. page 2428.

- ^ Genfer, Der Kosovo-Konflikt, Munich: Wieser, 2000. page 158.

- ^ New York Times 1981-04-19, "One Storm has Passed but Others are Gathering in Yugoslavia"

- ^ Reuters 1986-05-27, "Kosovo Province Revives Yugoslavia's Ethnic Nightmare"

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1986-07-28, "Tensions among ethnic groups in Yugoslavia begin to boil over"

- ^ New York Times 1987-06-27, "Belgrade Battles Kosovo Serbs"

- ^ SANU (1986): Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Memorandum. GIP Kultura. Belgrade.

- ^ http://www.opendemocracy.net/articles/ViewPopUpArticle.jsp?id=2&articleId=3361 Julie A Mertus: "Slobodan Milošević: Myth and Responsibility"

- ^ Reuters 1988-07-30, "Yugoslav Leaders Call for Control in Kosovo, Protests Loom"

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/SPECIALS/2000/kosovo/stories/past/milosevic/

- ^ The Economist, June 05, 1999, U.S. Edition, 1041 words, What's next for Slobodan Milošević?

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/1812847.stm

- ^ http://www.hrw.org/press/1999/jan/yugo0129.htm

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/781310.stm

- ^ http://observer.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,6903,194119,00.html

- ^ http://www.vajzat.com/eng.htm

- ^ http://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/kosovo/cuska/cuska_frameset.html

- ^ http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/balkans/crimesandcourage.html

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/inside_kosovo/velika_krusa.stm

- ^ http://www.haverford.edu/relg/sells/kosovo/herscherriedlmayer.htm

- ^ "Kosovo: The Human Rights Situation and the Fate of Persons Displaced from Their Homes (.pdf) ", report by Alvaro Gil-Robles, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, October 16, 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Note: Including Roma, Egyptian, Ashkalli, Turks and Bosniaks. – Sources:

- Coordinating Centre of Serbia for Kosovo-Metohija: Principles of the Program for Return of Internally Displaced Persons from Kosovo and Metohija

- "Kosovo: The Human Rights Situation and the Fate of Persons Displaced from Their Homes (.pdf) ", report by Alvaro Gil-Robles, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, October 16, 2002, p. 30.

- ^ UNHCR, Critical Appraisal of Responsee Mechanisms Operating in Kosovo for Minority Returns, Pristina, February 2004, p. 14.

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR), April 2000, Reversal of Fortune: Yugoslavia's Refugees Crisis Since the Ethnic Albanian Return to Kosovo, p. 2-3.

- ^ "Kosovo: The human rights situation and the fate of persons displaced from their homes (.pdf) ", report by Alvaro Gil-Robles, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, October 16, 2002.

- ^ International Relations and Security Network (ISN): Serbians return to Kosovo not impossible, says report (.pdf) , by Tim Judah, June 7, 2004.

- ^ European Stability Initiative (ESI): The Lausanne Principle: Multiethnicity, Territory and the Future of Kosovo's Serbs (.pdf) , June 7, 2004.

- ^ Coordinating Centre of Serbia for Kosovo-Metohija: Principles of the program for return of internally displaced persons from Kosovo and Metohija .

- ^ UNHCR: 2002 Annual Statistical Report: Serbia and Montenegro, pg. 9

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI): Country report: Serbia and Montenegro 2006.

- ^ U.S State Department Report, published in 2007

- ^ "Kosovo: Serb minister resigns over misuse of funds ", Adnkronos international (AKI), November 27, 2006

- ^ "Sole Kosovo Serb cabinet minister resigns: PM ", Agence France-Presse (AFP), November 24, 2006.

- ^ http://www.ks-gov.net/pm/?menuid=2&subid=20&subs=56&lingo=1

- ^ "UN envoy seeks multi-ethnic, self-governing Kosovo ", Agence France-Presse (AFP), Vienna, February 2, 2007.

- ^ "[http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20070310/wl_nm/serbia_kosovo1_dc_4;_ylt=AvL5xEUliSVd9RrxZLjpSI8XxHcA UN to decide Kosovo's fate as talks end deadlocked] ", Reuters, Vienna, March 10, 2007.

- ^ "Kosovo's status — the wheels grind on", The Economist, October 6, 2005

- ^ "Putin says world should regard Kosovo, separatist Georgian regions on equal footing", International Herald Tribune, September 13 2006.

- ^ "Russian ambassador: Compromise or veto", B92, December 4, 2006.

- ^ UNDP: Early Warning Report page 16, March 2007 http://www.kosovo.undp.org/repository/docs/EWR15FinalENG.pdf

- ^ worldbank.org

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1982-01-15, "Why Turbulent Kosovo has Marble Sidewalks but Troubled Industries"

- ^ worldbank.org

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/enlargement_papers/2005/elp26en.pdf

- ^ http://www.eciks.org/english/lajme.php?action=total_news&main_id=386

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/enlargement_papers/2005/elp26en.pdf

- ^ http://www.buyusa.gov/kosovo/en/doingbusinessinkosovo.html

- ^ http://www.seerecon.org/kosovo/documents/wb_econ_report/wb-kosovo-econreport-2-2.pdf

- ^ Croatia, Kosovo sign Interim Free Trade Agreement, B92, 2 October 2006

- ^ euinkosovo.org

- ^ http://www.kosovo-eicc.org/oek/index.php?page_id=64

- ^ http://www.buyusa.gov/kosovo/en/doingbusinessinkosovo.html

- ^ Kosovo Economic Briefing (April), worldbank.org

- ^ http://www.euinkosovo.org/uk/invest/invest.php

- ^ "Brussels offers first Kosovo loan", BBC News Online, 3 May 2005.

- ^ Transparency Initiative for Kosovo (TIK), UN Development Programme in Kosovo.

- ^ http://www.ks-gov.net/esk/esk/pdf/english/general/kosovo_figures_05.pdf

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4385768.stm

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/country_profiles/3524092.stm

- ^ http://www.salon.com/news/1999/03/31newsa.html

- ^ http://www.serbianunity.net/news/world_articles/Dragnich1098.html

- ^ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/4385768.stm

- ^ Religion in Kosovo - International Crisis Group

- ^ http://www.world-gazetteer.com/wg.php?x=&men=gcis&lng=en&dat=32&srt=npan&col=aohdq&geo=-244

External links

- The office of Prime Minister of Kosovo English version

- Kosovo Assembly (Kuvendi i Kosovës) English version

- The Official Webportal of Tourism in Kosovo

- EU Commission report on economic development in Accession countries, including Kosovo

- http://www.unosek.org/unosek/index.html UN Special Envoy's Office Website

- Template:Wikitravel

- RTK - Kosovo's public television - news in Albanian, Serbian, Turkish and Roma

- KosovaKosovo A source of information reflecting both sides’ claims in the dispute

- UNMIK UN led civilian administration in Kosovo.

- EU EU Pillar in Kosovo.

- Otvoreno A place where Serbian politicians speak openly on the Kosovo issue. In Serbian language only.

- KIM-Info News Service, News from Kosovo in English and Serbian

- (ICG) International Crisis Group, a source of independent analysis on Kosovo issues.

- Kosovo Roma Oral History Project An advocacy website for Kosovo's Roma/ Gypsies, with significant details on Kosovo's contested history.

- ECIKS Economic Initiative for Kosovo, information on investment opportunities.

- US State Dept. fact sheet "The Ethnic Cleansing of Kosovo"

- Kosovo Blog Online" Kosovo Search Challenge: Helping people find information for Kosovo, the positive side of Kosovo.

Pro-Albanian

- Albanian.com A Community portal where Albanians share information and ideas.

- Alliance for a New Kosovo A Policy Resource on Kosovo Independence.

- KosovoEvidence.com - movie about what happened in Kosovo during the war

- Economic Initiative for Kosovo - "...latest news, analysis and publications from the Kosovar economy"

- Kosovo Crisis Center A collection of articles on Kosovo, in English.

- AACL Albanian American Civic League.

- KosovaLive Kosovo Albanian independent news agency (this section in English).

- American Council for Kosova - U.S. nonprofit organization dedicated to a better understanding of the issue of Kosovo by the American public

Pro-Serbian

- Serbian Government for Kosovo-Metohija Website that focusses on the human rights situation of Serbian and other non-Albanian populations in Kosovo. (in English and Serbian)

- Kosovo Compromise Presentation on Kosovo issue of 4S Institute, Brussels

- Rastko Project dedicated to Serb and Serb-related arts and humanities(in English)

- Terror in Kosovo Terror in Kosovo (in English)

- Coordination Center of SCG and the Republic of Serbia for Kosovo (in English, Serbian and Albanian)

- Kosovo-The Land of the Living past (in English)

- B92 Serbian Independent news agency (in English)

- Save Kosovo - U.S. nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting a better American understanding of the Serbian province of Kosovo and Metohija and of the critical American stake in the province’s future. (in English)

- Kosovo 2006 Making of a Compromise (in English)

- Diocese Kosovo of Serbian Orthodox Church (in English, Serbian and Russian)

- [http://www.kosovo-metohija.com