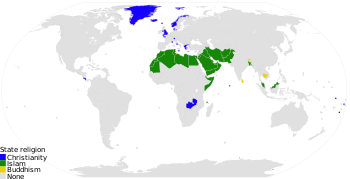

State religion

It has been suggested that State church be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2010. |

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

A state religion (also called an official religion, established church or state church) is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state. Practically, a state without a state religion is called a secular state, while a state governed by clergy is a theocracy.

The term state church is associated with Christianity, historically the state church of the Roman Empire, and is sometimes used to denote a specific modern national branch of Christianity. Closely related to state churches are what sociologists call ecclesiae, though the two are slightly different.

State religions are official or government-sanctioned establishments of a religion, but neither does the state need be under the control of the church (as in a theocracy), nor is the state-sanctioned church necessarily under the control of the state.

The institution of state-sponsored religious cults is ancient, reaching into the Ancient Near East and prehistory. The relation of religious cult and the state was discussed by Varro, under the term of theologia civilis ("civic theology"). The first state-sponsored Christian church was the Armenian Orthodox Church, established in 301 AD.[1]

Types of state churches

The degree and nature of state backing for denomination or creed designated as a state religion can vary. It can range from mere endorsement and financial support, with freedom for other faiths to practice, to prohibiting any competing religious body from operating and to persecuting the followers of other sects. In Europe, competition between Catholic and Protestant denominations for state sponsorship in the 16th century evolved the principle cuius regio eius religio ("states follow the religion of the ruler") embodied in the text of the treaty that marked the Peace of Augsburg, 1555. In England the monarch imposed Protestantism in 1533, with himself taking the place of the Pope, while in Scotland the Church of Scotland opposed the religion of the ruler.

In some cases, a state may have a set of state-sponsored religious denominations that it funds; such is the case in Alsace-Moselle in France under its local law, following the pattern in Germany.

In some communist states, notably in North Korea and Cuba, the state sponsors religious organizations, and activities outside those state-sponsored religious organizations are met with various degrees of official disapproval. In these cases, state religions are widely seen as efforts by the state to prevent alternate sources of authority.

State church vs state religion

There is also a difference between a "state church" and "state religion". A "state church" is created by the state,[citation needed] as in the cases of the Anglican Church, created by Henry VIII or the Church of Sweden, created by Gustav Vasa. An example of "state religion" is Argentina's acceptance of Roman Catholicism as its religion.[2] In the case of the former, the state has absolute control over the church, but in the case of the latter, in this example, the Vatican has control over the church.

Sociology of state churches

Sociologists refer to mainstream non-state religions as denominations. State religions tend to admit a larger variety of opinion within them than denominations. Denominations encountering major differences of opinion within themselves are likely to split; this option is not open for most state churches, so they tend to try to integrate differing opinions within themselves.

Many sociologists now consider the effect of a state church as analogous to a chartered monopoly in religion.

Where state religions exist, it is usually true the majority of residents are officially considered adherents; however, in some cases support is little more than nominal with many members not practicing the religion regularly such as the case with the Anglican Church in England. In other cases, such as in many countries that have Islam as a state religion, the proportion of practicing members is quite high and other religions' presence in the country is negligible.

A denomination's status as official religion does not always imply that the jurisdiction prohibits the existence or operation of other sects or religious bodies. It all depends upon the government and the level of tolerance the citizens of that country have for other religions. Some countries with official religions have laws that guarantee the freedom of worship, full liberty of conscience, and places of worship for all citizens; and implement those laws more than other countries that do not have an official or established state religion.

Disestablishment

Disestablishment is the process of depriving a church of its status as an organ of the state. Supporters of retaining an established church call themselves "antidisestablishmentarianists" — one of the longest words in the English language.

State religions by country

Canada

Section Two of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees freedom of religion. Progressively, case law has led to the overturning of specific laws that reflected religious observances (essentially Christian). Notwithstanding this, Roman Catholic schools are constitutionally protected and funded by taxes in some provinces.

United Kingdom

England

In late-19th-century England there was a campaign by Liberals, dissenters and nonconformists to disestablish the Church of England which was viewed, in the period after civil Chartist activism, as a discriminatory organisation placing employment and other access disabilities on non-members.

The campaigners styled themselves "Liberationists" (the "Liberation Society" was founded by Edward Miall in 1853). Though their campaign failed, nearly all of the legal disabilities of nonconformists were gradually dismantled. The campaign for disestablishment was revived in the 20th century when Parliament rejected the 1929 revision of the Book of Common Prayer, leading to calls for separation of Church and State to prevent political interference in matters of worship. In the late 20th century, reform of the House of Lords also brought into question the position of the Lords Spiritual. Another issue of controversy is the Act of Settlement 1701 which determines succession to the British monarchy, under which the head of state is also the head of the Church of England.

Scotland

Despite some official documentation (marriage registrations being a common example) describing the Church of Scotland as the "Established Church" the Kirk has always disclaimed that status. This was eventually acknowledged by the United Kingdom government within the Church of Scotland Act 1921. Since it has thus never been legally Established it cannot be disestablished.

Wales

In Wales, four Church of England dioceses were disestablished in 1920, becoming separated from the Church of England in the process and subsequently becoming the Church in Wales.

Ireland

The (Anglican) state church was disestablished in 1871, becoming the Church of Ireland. The Constitution of Ireland, in force since 1937, prohibits the state from endorsing any religion as an established church. Formerly, the constitution recognised the "special position" of the Catholic Church "as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the citizens", in addition with other religions, but these provisions were removed by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland in 1973.

United States of America

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution explicitly forbids the federal government from enacting any law respecting a religious establishment, and thus forbids either designating an official church for the United States, or interfering with State and local official churches — which were common when the First Amendment was enacted. It did not prevent state governments from establishing official churches. Connecticut continued to do so until it replaced its colonial Charter with the Connecticut Constitution of 1818; Massachusetts retained an establishment of religion in general until 1833.[3] (The Massachusetts system required every man to belong to some church, and pay taxes towards it; while it was formally neutral between denominations, in practice the indifferent would be counted as belonging to the majority denomination, and in some cases religious minorities had trouble being recognized at all.[citation needed]) As of 2010[update] Article III of the Massachusetts constitution still provides, "... the legislature shall, from time to time, authorize and require, the several towns, parishes, precincts, and other bodies politic, or religious societies, to make suitable provision, at their own expense, for the institution of the public worship of God, and for the support and maintenance of public Protestant teachers of piety, religion and morality, in all cases where such provision shall not be made voluntarily."[4]

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1868, makes no mention of religious establishment, but forbids the states to "abridge the privileges or immunities" of U.S. citizens, or to "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law". In the 1947 case of Everson v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme Court held that this later provision incorporates the First Amendment's Establishment Clause as applying to the States, and thereby prohibits state and local religious establishments. The exact boundaries of this prohibition are still disputed, and are a frequent source of cases before the U.S. Supreme Court — especially as the Court must now balance, on a state level, the First Amendment prohibitions on government establishment of official religions with the First Amendment prohibitions on government interference with the free exercise of religion. See school prayer for such a controversy in contemporary American politics.

All current State constitutions do mention a Creator,[citation needed] but include guarantees of religious liberty parallel to the First Amendment, but eight (Arkansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) also contain clauses that prohibit atheists from holding public office.[5][6] However, these clauses have been held by the U.S. Supreme Court to be unenforceable in the 1961 case of Torcaso v. Watkins, where the court ruled unanimously that such clauses constituted a religious test incompatible with the religious test prohibition in Article 6 Section 3 of the United States Constitution.

Predominant religions in secular states

More than 90 percent of the respective populations:

- Roman Catholic – Italy, Luxembourg, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Venezuela, and East Timor

- Islam – Azerbaijan, Gambia, Kosovo, Mali, Senegal, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan

- Buddhism – Burma

Present state religions

Currently, the following religions are recognized as state religions in some countries: some form of Christianity, Islam and Buddhism.

Christian countries

The following states recognize some form of Christianity as their state or official religion (by denomination):

Roman Catholic

Jurisdictions which recognize Roman Catholicism as their state or official religion:

- Costa Rica[7]

- Liechtenstein[8]

- Malta[9]

- Monaco[10]

- Vatican City (Holy See)

A number of countries, including Andorra, Argentina,[2] Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Italy,[11] Indonesia, Haiti, Honduras, Paraguay,[12] Peru,[13] Philippines, Poland,[14] Portugal, Slovakia, Spain[15] and Switzerland give a special recognition to Catholicism in their constitution despite not making it the state religion.

Eastern Orthodox

Jurisdictions which recognize one of the Eastern Orthodox Churches as their state religion:

- Greece (Church of Greece)[16]

- Finland: Finnish Orthodox Church has a special relationship with the Finnish state.[17] The internal structure of the church is described in the Orthodox Church Act. The church has a power to tax its members and corporations if a majority of shareholders are members. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the state does not have the authority to affect its internal workings or theology.

De-facto state religion status:

Protestantism

Lutheran

Jurisdictions which recognize a Lutheran church as their state religion include the Nordic countries. Membership is very high among the general population, however the amount of actively participating members and believers is considerably lower than in many other countries with similar membership statistics. Furthermore, all of these churches have lately seen decline in the fraction of the population being members.

- Denmark (Church of Denmark)[18]

- Iceland (Church of Iceland)[19] (79% of population members at the end of 2009) [20]

- Norway (Church of Norway)[21] (80% of population members at the end of 2009) [22]

- Finland: Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland has a special relationship with the Finnish state, its internal structure being described in a special law, the Church Act.[17] The Church Act can be amended only by a decision of the Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church and subsequent ratification by the parliament. The Church Act is protected by the Finnish constitution, and the state can not change the Church Act without changing the constitution. The church has a power to tax its members and all corporations unless a majority of shareholders are members of the Finnish Orthodox Church. The state collects these taxes for the church, for a fee. On the other hand, the church is required to give a burial place for everyone in its graveyards.[23] (79% of population members at the end of 2009).[24] The Finnish president also decides the themes for the intercession days. The church does not consider itself a state church, as the Finnish state does not have the power to influence its internal workings or its theology, although it has a veto in those changes of the internal structure which require changing the Church Act. Neither does the Finnish state accord any precedence to Lutherans or the Lutheran faith in its own acts.

- Sweden relegated their state church into a national church in 2000. In late 2009 the church of Sweden had 71.3% of the population as its members in 2009.[25]

Reformed

Jurisdictions which recognize a Reformed church as their state religion:

Anglican

Jurisdictions that recognise an Anglican church as their state religion:

Muslim countries

Almost all Muslim-majority countries recognize Islam as their state religion.

Sunni Islam

- Afghanistan

- Algeria (De-facto secular)

- Bahrain (Freedom of religion is protected by the law-unless you are a Shiite)

- Brunei

- Comoros[citation needed]

- Egypt

- Aceh Province, Indonesia (Secularism constitution-guaranteed, only applies to Aceh Province)

- Jordan (De-facto secular)

- Kuwait

- Libya

- Malaysia

- Maldives[citation needed]

- Mauritania

- Morocco

- Pakistan

- Qatar

- Saudi Arabia (Islamic kingdom, state-sanctioned)

- Somalia

- Tunisia (De-facto secular)

- United Arab Emirates

- Yemen

Shi'a Islam

Ibadi

- Oman (Freedom of religion is protected by the law)

Buddhist countries

Governments which recognize Buddhism, either a specific form of, or the whole, as their official religion:

- Bhutan (Drukpa Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism)[26]

- Cambodia (Theravada Buddhism)[27]

- Kalmykia, a republic within the Russian Federation (Tibetan Buddhism – sole Buddhist entity in Europe)

- Sri Lanka (Theravada Buddhism) – The constitution accords Buddhism the "foremost place," but Buddhism is not recognized as the state religion.[28]

- Thailand (Theravada Buddhism)- Thai constitution (2007) recognized Buddhism as "the religion of Thai tradition with the most adherents" However, it is not formally named as state religion.

Additional notes

- Israel is defined in several of its laws as a "Jewish and democratic state" (medina yehudit ve-demokratit). However, the term "Jewish" is a polyseme that can relate equally to the Jewish people or religion (see: Who is a Jew?). The debate about the meaning of the term Jewish and its legal and social applications is one of the most profound issues with which Israeli society deals.

At present, there is no specific law or official statement establishing the Jewish religion as the state's religion. However, the State of Israel supports religious institutions, particularly Orthodox Jewish ones, and recognizes the "religious communities" as carried over from those recognized under the British Mandate. These are: Jewish and Christian (Eastern Orthodox, Latin [Catholic], Gregorian-Armenian, Armenian-Catholic, Syrian [Catholic], Chaldean [Uniate], Greek Catholic Melkite, Maronite, and Syrian Orthodox). The fact that the Muslim population was not defined as a religious community is a vestige of the Ottoman period[citation needed] during which Islam was the dominant religion and does not affect the rights of the Muslim community to practice their faith. At the end of the period covered by this report, several of these denominations were pending official government recognition; however, the Government has allowed adherents of not officially recognized groups freedom to practice. In 1961, legislation gave Muslim Shari'a courts exclusive jurisdiction in matters of personal status. Three additional religious communities have subsequently been recognized by Israeli law – the Druze (prior under Islamic jurisdiction), the Evangelical Episcopal Church, and the Bahá'í.[29] These groups have their own religious courts as official state courts for personal status matters (see millet system).

The structure and goals of the Chief Rabbinate of Israel are governed by Israeli law, but the law does not say explicitly that it is a state Rabbinate. However, outspoken Israeli secularists such as Shulamit Aloni and Uri Avnery have long maintained that it is that in practice. Non-recognition of other streams of Judaism such as Reform Judaism and Conservative Judaism is the cause of some controversy; rabbis belonging to these currents are not recognized as such by state institutions and marriages performed by them are not recogngized as valid. As of 2010, there is no civil marriage in Israel, although there is recognition of marriages performed abroad.

- Nepal was once the world's only Hindu state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006.

- The Philippines is constituted as a de facto Roman Catholic-state[dubious – discuss] with religious freedom guarantees. In one region of the country is the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, which composed of all the country's predominantly Muslim provinces, the Regional Assembly is empowered to legislate on matters covered by the Shari'ah. Such legislation, however, applies only to Muslims.[30]

- Many countries indirectly fund the activities of different religious denominations by granting tax-exempt status to churches and religious institutions which qualify as charitable organizations.[31][32] However, these religions are not established as state religions.

Ancient state religions

Egypt and Sumer

The concept of state religions was known as long ago as the empires of Egypt and Sumer, when every city state or people had its own god or gods. Many of the early Sumerian rulers were priests of their patron city god. Some of the earliest semi-mythological kings may have passed into the pantheon, like Dumuzid, and some later kings came to be viewed as divine soon after their reigns, like Sargon the Great of Akkad. One of the first rulers to be proclaimed a god during his actual reign was Gudea of Lagash, followed by some later kings of Ur, such as Shulgi. Often, the state religion was integral to the power base of the reigning government, such as in Egypt, where Pharaohs were often thought of as embodiments of the god Horus.

Sassanid Empire

Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanid dynasty which lasted until 651, when Persia was conquered by the forces of Islam. However, it persisted as the state religion of the independent state of Hyrcania until the 15th century.

The tiny kingdom of Adiabene in northern Mesopotamia converted to Judaism around 34 AD.

Greek city-states

Many of the Greek city-states also had a 'god' or 'goddess' associated with that city. This would not be the 'only god' of the city, but the one that received special honors. In ancient Greece the city of Athens had Athena, Sparta had Ares, Delphi had Apollo and Artemis, Olympia had Zeus, Corinth had Poseidon and Thebes had Demeter.

Roman religion and Christianity

In Rome, the office of Pontifex Maximus came to be reserved for the emperor, who was often declared a 'god' posthumously, or sometimes during his reign. Failure to worship the emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link emperor worship with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians and Jews were subject to persecution, torture and death in the Roman Empire, because it was against their beliefs to worship the emperor.

In 311, Emperor Galerius, on his deathbed, declared a religious indulgence to Christians throughout the Roman Empire, focusing on the ending of anti-Christian persecution. Constantine I and Licinius, the two Augusti, by the Edict of Milan of 313, enacted a law allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the Edict of Milan cited that Christians may openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted, and provided that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the empire, it did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult (Roman polytheistic paganism). The Edict of Milan was written in such a way as to implore the blessings of the deity.

Constantine called up the First Council of Nicaea in 325, although he was not a baptised Christian until years later. Despite enjoying considerable popular support, Christianity was still not the official state religion in Rome, although it was in some neighboring states such as Armenia and Aksum.

Roman Religion (Neoplatonic Hellenism) was restored for a time by Julian the Apostate from 361 to 363. Julian does not appear to have reinstated the persecutions of the earlier Roman emperors.

Catholic Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and other ideologies deemed heretical, was declared to be the state religion of the Roman Empire on February 27, 380[33] by the decree De Fide Catolica of Emperor Theodosius I.[34]

Han Dynasty Confucianism

In China, the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) advocated Confucianism as the de facto state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement into government service—although, in fact, the "Confucianism" advocated by the Han emperors may be more properly termed a sort of Confucian Legalism or "State Confucianism". This sort of Confucianism continued to be regarded by the emperors, with a few notable exceptions, as a form of state religion from this time until the overthrow of the imperial system of government in 1911. Note however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-confucianism) is a religion or purely a philosophical system.

Modern era

Empire of Japan

From the Meiji era to the first part of the Showa era, Koshitsu Shinto was established in Japan as the national religion. According to this, the emperor of Japan was an arahitogami, an incarnate divinity and the offspring of goddess Amaterasu. As the emperor was, according to the constitution, "head of the empire" and "supreme commander of the Army and the Navy", every Japanese citizen had to obey his will and show absolute loyalty.

States/Countries without a state religion

These states do not profess a state religion, and are generally secular or laique. Countries which do not officially establish any religion include:

- Albania

- Armenia (Article 8.1 of the Armenian Constitution)

- Australia (Forbidden under the Constitution of Australia)

- Azerbaijan

- Brazil all states since 1988 – (Article 19 of the Brazilian Constitution)[35]

- Bolivia

- Canada

- Chile

- Cuba

- People's Republic of China

- Republic of China (Taiwan)

- East Timor[36]

- Ecuador

- Estonia[37]

- France

- Germany

- Hungary[38][39]

- India

- Ireland

- Italy

- Jamaica

- Japan (Shinto until end of WWII)

- Kosovo[40] (Independence partially recognised)

- Laos

- Lebanon (although by custom the president is a Maronite Catholic, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim and the speaker of the parliament a Shi'a Muslim.)[41]

- Mauritius

- Mexico (prohibited per Article 130 of the present Constitution of 1917)

- Montenegro

- Nepal (declared a secular state on May 18, 2006, by the newly resumed House of Representatives)

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Nigeria (federally secular, but allowing for the institutionalization of Islam and sharia in the predominantly-Muslim northern states)

- North Korea

- Philippines (forbidden explicitly under Article III Section 5 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution)

- Poland[42]

- Portugal

- Romania

- Russia

- Serbia

- Slovenia[43]

- Singapore

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Spain

- Sweden (Lutheran (Church of Sweden) until December 31, 1999.)

- Syria (though the constitution requires the president be Muslim and establishes Sharia as the official source of legislation)

- Turkey

- United Republic of Tanzania – The father of the Nation Mwalimu Julius K. Nyerere said the state does not have the religion but the people of the United Republic of Tanzania have, and each one is allowed to practice their religion freely as long as it does not cause harm to the other.

- United States (forbidden explicitly under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and implicitly in Article VI of the same document.)

- Puerto Rico (forbidden explicitly under Article II Section III of the Constitution of Puerto Rico. Also forbidden explicitly under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, as well as implicitly in Article VI of the same document. Puerto Rico is a Commonwealth of the United States).

- Uruguay

- Venezuela

- Vietnam

Established churches and former state churches

- ^ Finland's State Church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809–1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1870. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside with the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.

- ^ In France the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as Judaism.

- ^ In Hungary the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the Roman Catholic, Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 Judaism was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.

- ^ Article 44.1.2 of the 1937 Consititution recognised "the special position of the Holy Catholic Apostolic and Roman Church", while Article 44.1.3 recognised other named religions. Both were deleted in 1972.

- ^ Disestablished by in the article 5 of the Malolos Constitution upon independence, although the Roman Catholic Church itself is often treated as a de facto state religion in the country today.[45]

- ^ Article 114 of the Polish March Constitution of 1921 declared the Roman Catholic Church to hold "the principal position among religious denominations equal before the law" (in reference to the idea of first among equals). The article was continued in force by article 81 of the April Constitution of 1935. The Soviet-backed PKWN Manifesto of 1944 reintroduced the March Constitution, which remained in force until it was replaced by the Small Constitution of 1947.

- ^ The Church in Wales was split from the Church of England in 1920 by Welsh Church Act 1914; at the same time becoming disestablished.

Former state churches in British North America

Protestant colonies

- The colonies of Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, New Haven, and New Hampshire were founded by Puritan Calvinist Protestants.

- The colonies of New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were officially Church of England.

Catholic colonies

- When New France was transferred to Great Britain in 1763, the Roman Catholic Church remained under toleration, but Huguenots were allowed entrance where they had formerly been banned from settlement by Parisian authorities.

- The Colony of Maryland was founded by a charter granted in 1632 to George Calvert, secretary of state to Charles I, and his son Cecil, both recent converts to Roman Catholicism. Under their leadership many English Catholic gentry families settled in Maryland. However, the colonial government was officially neutral in religious affairs, granting toleration to all Christian groups and enjoining them to avoid actions which antagonized the others. On several occasions low-church dissenters led insurrections which temporarily overthrew the Calvert rule. In 1689, when William and Mary came to the English throne, they acceded to demands to revoke the original royal charter. In 1701 the Church of England was proclaimed, and in the course of the eighteenth century Maryland Catholics were first barred from public office, then disenfranchised, although not all of the laws passed against them (notably laws restricting property rights and imposing penalties for sending children to be educated in foreign Catholic institutions) were enforced, and some Catholics even continued to hold public office.

- Spanish Florida was ceded to Great Britain in 1763, the British divided Florida into two colonies. Both East and West Florida continued a policy of toleration for the Catholic Residents.

Colonies with no established church

- The Province of Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers, but the colony never had an established church.

- The Province of New Jersey, without official religion, had a significant Quaker lobby, but Calvinists of all stripes also had a presence.

- Delaware Colony had no established church, but was contested between Catholics and Quakers.

- The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, founded by religious dissenters forced to flee the Massachusetts Bay colony, is widely regarded as the first polity to grant religious freedom to all its citizens, although Catholics were barred intermittently. Baptists, Seekers/Quakers and Jews made this colony their home.

Tabular summary

| Colony | Denomination | Disestablished1 |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut | Congregational | 1818 |

| Georgia | Church of England/Episcopal Church | 17892 |

| Maryland | Church of England/Episcopal Church | 1776 |

| Massachusetts | Congregational | 18333 |

| New Brunswick | Church of England | |

| New Hampshire | Congregational | 17904 |

| Newfoundland | Church of England | |

| North Carolina | Church of England/Episcopal Church | 17765 |

| Nova Scotia | Church of England | 1850 |

| Prince Edward Island | Church of England | |

| South Carolina | Church of England/Episcopal Church | 1790 |

| Canada West | Church of England | 1854 |

| West Florida | Church of England6/Episcopal Church | 17837 |

| East Florida | Church of England6/Episcopal Church | 17837 |

| Virginia | Church of England/Episcopal Church | 17868 |

| West Indies | Church of England | 1868 (Barbados, not until 1969) |

^Note 1: In several colonies, the establishment ceased to exist in practice at the Revolution, about 1776;[47] this is the date of permanent legal abolition.

^Note 2: in 1789 the Georgia Constitution was amended as follows: "Article IV. Section 10. No person within this state shall, upon any pretense, be deprived of the inestimable privilege of worshipping God in any manner agreeable to his own conscience, nor be compelled to attend any place of worship contrary to his own faith and judgment; nor shall he ever be obliged to pay tithes, taxes, or any other rate, for the building or repairing any place of worship, or for the maintenance of any minister or ministry, contrary to what he believes to be right, or hath voluntarily engaged. To do. No one religious society shall ever be established in this state, in preference to another; nor shall any person be denied the enjoyment of any civil right merely on account of his religious principles."

^Note 3: From 1780 Massachusetts had a system which required every man to belong to a church, and permitted each church to tax its members, but forbade any law requiring that it be of any particular denomination. This was objected to, as in practice establishing the Congregational Church, the majority denomination, and was abolished in 1833.

^Note 4: Until 1877 the New Hampshire Constitution required members of the State legislature to be of the Protestant religion.

^Note 5: The North Carolina Constitution of 1776 disestablished the Anglican church, but until 1835 the NC Constitution allowed only Protestants to hold public office. From 1835–1876 it allowed only Christians (including Catholics) to hold public office. Article VI, Section 8 of the current NC Constitution forbids only atheists from holding public office.[48] Such clauses were held by the United States Supreme Court to be unenforceable in the 1961 case of Torcaso v. Watkins, when the court ruled unanimously that such clauses constituted a religious test incompatible with First and Fourteenth Amendment protections.

^Note 6: Religious tolerance for Catholics with an established Church of England was policy in the former Spanish Colonies of East and West Florida while under British rule.

^Note 7: In 1783 Peace of Paris, which ended the American Revolutionary War, the British ceded both East and West Florida back to Spain (see Spanish Florida).

^Note 8: Tithes for the support of the Anglican Church in Virginia were suspended in 1776, and never restored. 1786 is the date of the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom, which prohibited any coercion to support any religious body.

Non-Anglo-American colonies

In both cases, these areas were disestablished and dissolved, yet their presences were tolerated by the Anglo-American government, as Foreign Protestants, whose communities were expected to observe their own ways without causing controversy or conflict for the prevalent colonists. After the Revolution, their ethno-religious backgrounds were chiefly sought as the most compatible non-British Isles immigrants.

- New Netherland was founded by Dutch Reformed Calvinists.

- New Sweden was founded by Church of Sweden Lutherans.

State of Deseret

The State of Deseret was a provisional state of the United States, proposed in 1849 by Mormon settlers in Salt Lake City. The provisional state existed for slightly over two years, but attempts to gain recognition by the United States government floundered for various reasons. The Utah Territory which was then founded was under Mormon control, and repeated attempts to gain statehood met resistance, in part due to concerns over the principle of separation of church and state conflicting with the practice of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints of placing their highest value on "following counsel" in virtually all matters relating to their church-centered lives. The state of Utah was eventually admitted to the union on January 4, 1896, after the various issues had been resolved.[49]

See also

- List of state-established religions

- Civil religion

- Political religion

- Separation of church and state

- Freedom of religion

- Status of religious freedom by country

- Religious toleration

- Secular state

- Secular religion

References

- ^ The Journal of Ecclesiastical History – Page 268 by Cambridge University Press, Gale Group, C.W. Dugmore

- ^ a b Argentina Constitution: Section 2, Constitutional Law.

- ^ James H. Hutson (2000). Religion and the new republic: faith in the founding of America. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 22. ISBN 9780847694341.

- ^ CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, malegislature.gov.

- ^ "State Constitutions that Discriminate Against Atheists". www.godlessgeeks.com. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ "Religious laws and religious bigotry – Religious discrimination in U.S. state constitutions". www.religioustolerance.com. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ The Constitution of Costa Rica, TITLE VI: RELIGION, CostaRicaLaw.com.

- ^ a b Constitution of the Principality of Liechtenstein: Article 37(2), digital Liechtenstein.

- ^ Malta – Constitution, Constitutional Law, Section 2 [State Religion].

- ^ CONSTITUTION DE LA PRINCIPAUTE (French): Art. 9., Principaute De Monaco: Ministère d'Etat.

- ^ The Constitution of the Italian Republic (PDF),

The State and the Catholic Church are independent and sovereign, each within its own sphere. Their relations are regulated by the Lateran pacts. Amendments to such Pacts which are accepted by both parties shall not require the procedure of constitutional amendments. [...] Denominations other than Catholicism have the right to self-organisation according to their own statutes, provided these do not conflict with Italian law. Their relations with the State are regulated by law, based on agreements with their respective representatives.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Paraguay,

The role played by the Catholic Church in the historical and cultural formation of the Republic is hereby recognized.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Peru (PDF),

Within an independent and autonomous system, the State recognizes the Catholic Church as an important element in the historical, cultural, and moral formation of Peru and lends it its cooperation. The State respects other denominations and may establish forms of collaboration with them.

{{citation}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 79 (help) - ^ The Constitution of the Republic of Poland, 1997-04-02,

The relations between the Republic of Poland and the Roman Catholic Church shall be determined by international treaty concluded with the Holy See, and by statute. The relations between the Republic of Poland and other churches and religious organizations shall be determined by statutes adopted pursuant to agreements concluded between their appropriate representatives and the Council of Ministers.

- ^ Spanish , ,Constitution (PDF),

The public authorities shall take into account the religious beliefs of Spanish society and shall consequently maintain appropriate cooperation relations with the Catholic Church and other confessions.

- ^ a b THE CONSTITUTION OF GREECE : SECTION II RELATIONS OF CHURCH AND STATE, Hellenic Resources network.

- ^ a b Finland – Constitution, Section 76 The Church Act, http://servat.unibe.ch/icl/fi00000_.html.

- ^ Denmark – Constitution: Section 4 [State Church], Constitutional Law.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Iceland: Article 62, Government of Iceland.

- ^ "Statistics Iceland - Statistics » Population » Religious organisations". Statice.is. 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- ^ Norway – Constitution: Article 2 [Religion, State Religion], Constitutional Law.

- ^ "Kirken.no - Medlemskap i kirken". Den norske kirke (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ^ Status of the Finnish State Church in 2007—Privileges of the State Church, eroakirkosta.fi, 7 October 2007, retrieved 2007-10-23

- ^ Ennakkotiedot ev.lut. kirkon 2009 väestörakenteesta evl.fi 31.12.2009

- ^ "Medlemmar 1972-2008, tabell och diagram" (XLS, 22.5 KiB) (in Swedish). Svenska kyrkan.

- ^ Draft of Tsa Thrim Chhenmo (pdf), www.constitution.bt, August 1, 2007, retrieved 2007-10-18Article 3, Spiritual Heritage

1. Buddhism is the spiritual heritage of Bhutan, which promotes the principles and values of peace, non-violence, compassion and tolerance.

2. The Druk Gyalpo is the protector of all religions in Bhutan.

3. It shall be the responsibility of religious institutions and personalities to promote the spiritual heritage of the country while also ensuring that religion remains separate from politics in Bhutan. Religious institutions and personalities shall remain above politics.

4. The Druk Gyalpo shall, on the recommendation of the Five Lopons, appoint a learned and respected monk ordained in accordance with the Druk-lu, blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog, as the Je Khenpo. 5. His Holiness the Je Khenpo shall, on the recommendation of the Dratshang Lhentshog, appoint monks blessed with the nine qualities of a spiritual master and accomplished in ked-dzog as the Five Lopons.

6. The members of the Dratshang Lhentshog shall comprise:

(a) The Je Khenpo as Chairman;

(b) The Five Lopons of the Zhung Dratshang; and

(c) The Secretary of the Dratshang Lhentshog who is a civil servant.

7. The Zhung Dratshang and Rabdeys shall continue to receive adequate funds and other facilities from the State. - ^ Constitution of Cambodia, constitution.org, retrieved 2007-10-18 (Article 43)

- ^ "Chapter II — Buddhism", The Constitution of the Republic of Sri lanka, The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka, retrieved 2007-10-18

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2009 : Israel and the occupied territories, U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- ^ REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9054 : AN ACT TO STRENGTHEN AND EXPAND THE ORGANIC ACT FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 6734, ENTITLED "AN ACT PROVIDING FOR THE AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO, AS AMENDED (PDF), Congress of the Philippines (Article IV, Section 3e)

- ^ Internal Revenue Service. "Tax guide for churches and Religious Institutions" (PDF). United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ Internal Revenue Seervice. "Exemption Requirements". United States Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ "The Theodosian Code". THE LATIN LIBRARY at Ad Fontes Academy. Ad Fontes Academy. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (1997). "Theodosian Code XVI.i.2". Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ Section 12 of the East Timorese Constitution

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Estonia

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Hungary

- ^ The right of thought, the freedom of conscience and religion –Hungary.hu

- ^ Draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo

- ^ The Constitution of Lebanon specifies that the President is elected by the Chamber of Deputies, in which equal representation between Christians and Muslims is constitutionally required, and specifies that the President designates the Prime Minister in consultation with the President of the Chamber of Deputies.

- ^ Article 25 of the constitution states: "1. Churches and other religious organizations shall have equal rights. 2. Public authorities in the Republic of Poland shall be impartial in matters of personal conviction"

- ^ Article 7 of the constitution

- ^ Under the 1967 Constitution, Roman Catholicism was the state religion as stated in Article 6: "The Roman Catholic Apostolic religion is the state religion, without prejudice to religious freedom, which is guaranteed in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. Official relations of the republic with the Holy See shall be governed by concordats or other bilateral agreements." The 1992 Constitution, which replaced the 1967 one, establishes Paraguay as a secular state, as mentioned in section (1) of Article 24: "Freedom of religion, worship, and ideology is recognized without any restrictions other than those established in this Constitution and the law. The State has no official religion."

- ^ "Malolos Constitution". MSC Institute of Technology. June 12, 1898. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ The modern Church of Scotland has always disclaimed recognition as an "established" church. The Church of Scotland Act 1921 formally recognised the Kirk's independence from the state.

- ^ "Rights of the People: Individual freedom and the Bill of Rights". US State Department. 2003. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Article VI of the North Carolina state constitition

- ^ Struggle For Statehood Edward Leo Lyman, Utah History Encyclopedia

External links

- McConnell, Michael W. (2003), "Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion", William and Mary Law Review, provided by Questia.com, 44 (5): 2105, retrieved 2006-11-23.

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)