Syrian civil war

| Modernday day genocide Syria | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring | |||||||

| File:Syriancivilwarcollage2.png Clockwise from top left: Opposition protest in Idlib in support of Free Syrian Army; FSA members with captured tank; burning building in Homs; Syrian Army checkpoint in Damascus. (For a war map of the current situation in Syria, see here) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Supported by: (For other forms of foreign support, see here) Supported by: Supported by: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hassan Nasrallah Commander of Hezbollah in Syria |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

70,000–100,000 fighters[30]

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

34,334[49][56]–35,429[35] Syrians killed overall (opposition claims)** 335,000–500,000 refugees[58] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

The Syrian civil war,[60] also referred to as the Syrian uprising,[61] is an ongoing armed conflict in Syria between forces loyal to the Ba'ath Party government and those seeking to oust it. The conflict began on 15 March 2011 with nationwide demonstrations as part of the wider protest movement known as the Arab Spring. Protesters demanded the resignation of President Bashar al-Assad, as well as the end to nearly five decades of Ba'ath Party rule.

In April 2011, the Syrian Army was deployed to quell the uprising, and soldiers were ordered to open fire on civilians. After months of military sieges, the protests evolved into an armed rebellion. Opposition forces, mainly composed of defected soldiers and civilian volunteers, became increasingly armed and organized as they unified into larger groups, with some groups receiving military aid from several foreign countries. However, the rebels remained fractured, without organized leadership. The Syrian government characterizes the insurgency as "armed terrorist groups." The conflict has no clear fronts, with clashes taking place in many towns and cities across the country.

The Arab League, United States, European Union, GCC states and other countries have condemned the use of violence against the protesters. China and Russia have opposed attempts to agree to a UN resolution condemning Assad's actions, and advised against sanctions, saying that such methods could escalate into foreign military intervention.[62] The Arab League suspended Syria's membership because of the government's response to the crisis, but sent an observer mission in December 2011, as part of its proposal for peaceful resolution of the crisis. A further attempt to resolve the crisis was made through the appointment of Kofi Annan as a special envoy. On 15 July 2012, the International Committee of the Red Cross assessed the Syrian conflict as a "non-international armed conflict" (the ICRC's legal term for civil war), thus applying international humanitarian law under the Geneva Conventions to Syria.

According to various sources, between 30,000[63] and 46,760[35][64] people have been killed, including 17,625–19,415 armed combatants consisting of both the Syrian army and rebel forces, and the other half civilians,[65][66] and up to 2,120 opposition protesters.[47][48] By October 2012, up to 28,000 people were reported missing including civilians forcibly abducted by government troops or security forces.[67] According to the UN, about 1.2 million Syrians have been displaced within the country.[58] To escape the violence, hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees have fled to neighboring countries. In addition, tens of thousands of protesters have been imprisoned, and there have been reports of widespread torture in the government's prisons.[68][69] International organizations have accused the government and Shabiha of severe human rights violations.[70] Anti-government rebels have been accused of human rights abuses as well. The vast majority of abuses have, however, been committed by the Syrian government's forces.[71][72]

Background

History

The Ba'ath Party government came to power in 1963 after a successful coup d'état. In 1966, another coup overthrew the traditional leaders of the party, Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar.[73] In 1970, the Defense Minister Hafez al-Assad seized power and declared himself President, a position he would hold until his death in 2000. Since then, the Ba'ath Party has remained the sole authority in Syria, and Syrian citizens may only approve the President by referendum and do not hold multi-party elections for the legislature.[74] In 1982, at the height of a six-year Islamist insurgency throughout the country, Hafez Assad conducted a scorched earth policy against the town of Hama to quell an uprising by the Sunni Islamist community, including the Muslim Brotherhood and others.[75] This became known as the Hama massacre, which left tens of thousands dead.[76]

The issue of Hafez al-Assad's succession prompted the 1999 Latakia protests,[77] when violent protests and armed clashes erupted following the 1998 People's Assembly Elections. The violent events were an explosion of a long-running feud between Hafez al-Assad and his younger brother Rifaat.[77] Two people were killed in fire exchanges between Syrian police and Rifaat's supporters during a police crack-down on Rifaat's port compound in Latakia. According to opposition sources, denied by the government, the protests resulted in hundreds dead and injured.[78] Hafez al-Assad died one year later, from pulmonary fibrosis. He was succeeded by his son Bashar al-Assad, who was appointed after a constitutional amendment lowered the age requirement for President from 40 to his age of 34.[74]

Bashar al-Assad, who speaks English fluently and whose wife is British-born, initially inspired hopes for reform; a "Damascus Spring" of intense social and political debate took place from July 2000 to August 2001.[79] The period was characterized by the emergence of numerous political forums or salons where groups of like minded people met in private houses to debate political and social issues. Political activists such as Riad Seif, Haitham al-Maleh, Kamal al-Labwani, Riyad al-Turk and Aref Dalila were important in mobilizing the movement.[80] The most famous of the forums were the Riad Seif Forum and the Jamal al-Atassi Forum. The Damascus Spring ended in August 2001 with the arrest and imprisonment of ten leading activists who had called for democratic elections and a campaign of civil disobedience.[77] Opposition renewed in October 2005 when activist Michel Kilo collaborated with other leading opposition figures to launch the Damascus Declaration, which criticized the Syrian government as "authoritarian, totalitarian and cliquish" and called for democratic reform.[81]

Religion

The Assad family comes from the minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shi'ite Islam that comprises an estimated 12 percent of the Syrian population.[82] It has maintained tight control on Syria's security services, generating resentment among some Sunni Muslims,[83] a sect that makes up about three quarters of Syria's population. Minority Kurds have also protested and complained.[84] When the uprising began, Bouthaina Shaaban, a presidential adviser, blamed Sunni clerics and preachers for inciting Sunnis to revolt, such as Qatar-based Yusuf al-Qaradawi in a sermon in Doha on 25 March.[85] The Syrian government has relied mostly on Alawite-dominated units of the security services to fight the uprising. Assad's younger brother Maher al-Assad commands the army's Fourth Armored Division, and his brother-in-law, Assef Shawkat, was the deputy minister of defense. Because the government is dominated by the Alawite sect, it has had to make some gestures toward the majority Sunni sects and other minority populations in order to retain power.

Socioeconomics

Popular opposition against the government was stronger in the nation's poorer areas.[86] These included cities with high poverty rates, such as Daraa and Homs, rural areas hit hard by a drought in early 2011, and the poor districts of large cities. Socioeconomic inequality increased significantly after free market policies were initiated by Hafez Assad in his late rule, and accelerated during the rule of Bashar Assad. With emphasis on the service sector, the policies benefited a minority of the nation's population, mostly people who had connections with the government, and people in the merchant class of Damascus and Aleppo, the country's two biggest cities.[86] Socioeconomic complaints were reported, such as a deterioration in the country's standard of living and steep rises in prices of commodities.[87] The country also faced particularly high youth unemployment rates.[88]

Human rights

The state of human rights in Syria has long been the subject of harsh criticism from global organizations.[89] The country was under emergency rule from 1963 until 2011, effectively granting security forces sweeping powers of arrest and detention.[90] The Syrian government has justified this by pointing to the fact that the country has been in a continuous state of war with Israel. After taking power in 1970, Hafez al-Assad quickly purged the government of any political adversaries and asserted his control over all aspects of Syrian society. He developed an elaborate cult of personality and violently repressed any opposition, most notoriously in the 1982 Hama massacre. After his death in 2000 and the succession of his son Bashar al-Assad to the Presidency, it was hoped that the Syrian government would make concessions toward the development of a more liberal society; this period became known as the Damascus Spring. However, al-Assad is widely regarded to have been unsuccessful in implementing democratic change, with a 2010 report from Human Rights Watch stating that he had failed to improve the state of human rights since taking power ten years prior.[91] All other political parties have remained banned, thereby making Syria a one-party state without free elections.[90]

Rights of expression, association and assembly are strictly controlled in Syria.[92] The authorities harass and imprison human rights activists and other critics of the government, who are oftentimes indefinitely detained and tortured in poor prison conditions.[92] While al-Assad permitted radio stations to play Western pop music, websites such as Amazon, Facebook, Wikipedia and YouTube were blocked until 1 January 2011, when all citizens were permitted to sign up for high speed Internet, and those sites were allowed.[93] However, a 2007 law requires Internet cafes to record all comments that users post on online chat forums.[94]

Women and ethnic minorities have faced discrimination in the public sector.[92] Thousands of Syrian Kurds were denied citizenship in 1962, and their descendants continued to be labeled as "foreigners" until 2011, when 120,000 out of roughly 200,000 stateless Kurds were granted citizenship on 6 April.[95] Several riots prompted increased tension in Syria's Kurdish areas since 2004. That year, riots broke out against the government in the northeastern city of Qamishli. During a chaotic soccer match, some people raised Kurdish flags, and the match turned into a political conflict. In a brutal reaction by Syrian police and clashes between Kurdish and Arab groups, at least 30 people were killed,[96] with some claims indicating a casualty count of about 100 people.[97] Occasional clashes between Kurdish protesters and security forces have since continued.

Arab Spring

In December 2010, mass anti-government protests began in Tunisia and later spread across the Arab world, including Syria. By February 2011, revolutions occurred in Tunisia and Egypt, while Libya began to experience a civil war. Numerous other Arab countries also faced protests, with some attempting to calm the masses by making concessions and governmental changes. The events were later commonly referred to as the Arab Spring.

Chemical weapons

The issue of chemical weapons has been important, as Syria is thought to have the third largest stockpile of such weapons in the world, and opposition forces are concerned they may be used as a last resort to remain in power by the regime.[98] Countries such as the United States have described the use of such weapons as a "red line" for the Ba'athist regime that would result in "enormous consequences".[99] Similarly, France and the United Kingdom have promised consequences in regards to the use of chemical weapons including military interventionism, with France in particular promising a "massive and blistering" response.[100]

Syrian foreign ministry spokesman Jihad Makdissi in July 2012 explicitly threatened the use of chemical weapons as an option against "external aggression", while claiming that the regime would not use these same weapons against domestic Syrian opposition forces in the civil war.[101] The regime went on to threaten the use of "Syrian rockets... loaded with chemical warheads" against targets "including countries neighbouring Syria”.[102] In September 2012, the Syrian military began moving chemical weapons from Damascus to the port city of Tartus.[103][104] Also in September 2012, it was reported that the Syrian military had restarted testing of chemical weapons at a base on the outskirts of Aleppo in August.[105][106] Major-General Adnan Sillu stated that prior to his defection, he had been involved in high level talks in which the Syrian regime came up with plans to use chemical weapons upon both civilians and opposition forces in important areas, mentioning Aleppo specifically.[107]

On 28 September US Defence Secretary Leon Panetta stated that the Syrian regime had moved CBW weapons in order to "secure" them in the face of Opposition forces.[108] Further, it emerged that the Russian government had helped set up communications with the United States and Syria in regards to the matter of chemical weapons. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that Syria had given the United States "explanations" and "assurances" that it was taking care of these weapons.[102]

Uprising and civil war

Beginnings of protests

Before the uprising in Syria began in mid-March 2011, protests were relatively modest, considering the wave of unrest that was spreading across the Arab world. Syria remained what Al Jazeera described as a "kingdom of silence", due to strict security measures, a relatively popular president, religious diversity, and concerns over the prospects of insurgency like that seen in neighboring Iraq.[110]

The events began on 26 January 2011,[111] when Hasan Ali Akleh from Al-Hasakah poured gasoline on himself and set himself on fire, in the same way Tunisian Mohamed Bouazizi had in Tunis on 17 December 2010. According to eyewitnesses, the action was "a protest against the Syrian government".[112] Two days later, on 28 January 2011, an evening demonstration was held in Ar-Raqqah to protest the killing of two soldiers of Kurdish descent.[113]

On 3 February, a "Day of Rage" was called for in Syria from 4–5 February on social media websites Facebook and Twitter; however, protests failed to materialize within the country itself.[114] Hundreds marched in Al-Hasakah, but Syrian security forces dispersed the protest and arrested dozens of demonstrators.[115] A protest in late February at the Libyan Embassy in Damascus to demonstrate against the government of Muammar Gaddafi, facing his own major protests in Libya, was met with brutal beatings from Syrian police moving to disperse the demonstration against a friendly regime.[116]

On 6 March young boys were arrested in the city of Daraa for writing the slogan "the people want to overthrow the regime" on walls across the city. The following day 13 political prisoners went on a hunger strike protesting "political detentions and oppression" in their country demanding the implementation of civil and political rights. Three days later dozens of Syrian Kurds started their own hunger strike in solidarity with these other strikers.[117] During this time, Ribal al-Assad, a government critic, said that it was almost time for Syria to be the next domino in the burgeoning Arab Spring.[118]

Revolt and escalating protests

The protests, unrest and confrontations began in earnest on 15 March, when the protest movement began to escalate, as simultaneous demonstrations took place in major cities across Syria.[119] In Damascus, a crowd of 150 was heard chanting "The revolution has started!"[120] Protesters demanded the release of political prisoners, the abolition of Syria's 48-year emergency law, more freedoms, and an end to pervasive government corruption.[121]

On 16 March, some 200 people gathered in front of the Interior Ministry, calling for the release of political prisoners. Thousands of protesters gathered in al-Hasakah, Daraa, Deir ez-Zor, and Hama. There were some clashes with security, according to reports from dissident groups. In Damascus, a smaller group of 200 men grew spontaneously to about 1,500 men. Damascus has not seen such uprising since the 1980s.[122][123]

These events lead to a "Friday of Dignity" on 18 March, when large-scale protests broke out in several cities, including Banias, Damascus, al-Hasakah, Daraa, Deir az-Zor and Hama. Police responded to the protests with tear gas, water canons, beatings and even live ammunition. At least 6 people were killed and many others injured. Over the course of the uprising, protests often gathered after Friday communal prayers at central mosques. Over the next few days the security forces broke up a silent gathering in Marjeh square in Damascus. The protest saw to 150 people holding up pictures of their family and friends who were imprisoned by the regime. Security forces also shot people dead in Daraa. This incident led to thousands taking to the streets calling for democracy. The security crackdown on these protesters led to several more days of protests and even more civilians shot dead by the security forces.[117]

Increasingly, the city of Daraa became the focal point for the growing uprising, with large demonstrations day after day. This city has been straining under the influx of internal refugees who were forced to leave their northeastern lands due to a drought which was exacerbated by the government's lack of provision.[124] Over 100,000 people reportedly marched in Daraa on 25 March, but at least 20 protesters were reportedly killed. Protests also spread to other Syrian cities, including Homs, Hama, Baniyas, Jasim, Aleppo, Damascus and Latakia. Over 70 protesters in total were reported dead.[125]

Domestic response

Arrests and torture

Even before the uprising began, the Syrian government conducted numerous arrests of protestors, political activists and human rights campaigners, many of whom were labeled "terrorists" by Assad. In early February, authorities arrested several activists, including political leaders Ghassan al-Najar,[126] Abbas Abbas,[127] and Adnan Mustafa.[128]

The police often responded to the protests violently, not only using water cannons and tear gas, but also beating protesters and firing live ammunition.[129]

As the uprising began, the Syrian government waged a campaign of arrests that had caught tens of thousands of people, according to lawyers and activists in Syria and human rights groups. In response to the uprising, Syrian law had been changed to allow the police and any of the nation's 18 security forces to detain a suspect for eight days without a warrant. Arrests focused on two groups: political activists, and men and boys from the towns that the Syrian Army would start to besiege in April.[130]

Many of those detained experienced various forms of torture and ill-treatment. Many detainees were cramped in tight rooms and were given limited resources, and some were beaten, electrically jolted, or debilitated. At least 27 torture centers, run by Syrian intelligence agencies were revealed by Human Rights Watch on 3 July 2012.[131]

Concessions

During March and April, the Syrian government, hoping to alleviate the unrest, offered political reforms and policy changes. Authorities shortened mandatory army conscription,[132] and in an apparent attempt to reduce corruption, fired the governor of Daraa.[133] The government announced it would release political prisoners, cut taxes, raise the salaries of public sector workers, provide more press freedoms, and increase job opportunities.[134] Many of these announced reforms were never implemented.

The government, dominated by the Alawite sect, made some concessions to the majority Sunni and some minority populations. Authorities reversed a ban that restricted teachers from wearing the niqab, and closed the country's only casino.[135] The government also granted citizenship to thousands of Syrian Kurds previously labeled "foreigners".[95]

A popular demand from protestors was an end of the nation’s state of emergency, which had been in effect for nearly 50 years. The emergency law had been used to justify arbitrary arrests and detention, and to ban political opposition. After weeks of debate, Assad signed the decree on 21 April, lifting Syria’s state of emergency.[136]

Crackdown

Anti-government protests continued in April, with activists unsatisfied with what they considered vague promises of reform from Assad.[137] During the month, the uprising became more extensive and more violent, as the government sent security forces into restive towns and cities. Many protesters were arrested, beaten, shot or killed. Assad characterizes the opposition as armed terrorist groups with Islamist motives.[138] Early in the month, a large deployment of security forces prevented tent encampments in Latakia. Blockades were set up in several cities, to prevent the movement of protests. Despite the crackdown, widespread protests remained throughout the month in Daraa, Baniyas, Al-Qamishli, Homs, Douma and Harasta.[139]

Censorship of events

Since demonstrations began in March, the Syrian government has restricted independent news coverage, barring foreign free press outlets and arresting reporters who try to cover protests. Some journalists had been reported to have gone missing, been detained, been tortured in custody, or been killed on duty. International media have relied heavily on footage shot by civilians, who would often upload the files on the internet.[140]

The government disabled mobile phones, landlines, electricity, and the Internet in several places. Authorities had extracted passwords of social media sites from journalists through beatings and torture. The pro-government online group the Syrian Electronic Army had frequently hacked websites to post pro-regime material, and the government has been implicated in malware attacks targeted at those reporting on the crisis. The government also targeted and tortured political cartoonists who were critical of the crackdown.[141]

Propaganda

Propaganda has been used by the Syrian government since the beginning of the conflict.[142] SANA, the government’s official news agency, often refers to the opposition as “armed gangs” or “terrorists.” Although there are extremists fighting against the government,[143] most independent media sources do not refer to the opposition as terrorists. Television interviews sometimes use loyalists disguised as locals who stand near sites of destruction and claim that they were caused by rebel fighters.[142]

Public school instructors teach students that the ongoing conflict is a foreign conspiracy.[144]

Defections

When the uprising began in mid-March, many analysts believed that the Syrian government would remain intact, partly due to strict loyalty tests and the fact that most top-position officials belonged to the same sect as Assad, the Alawites. However, in response to the use of lethal force against unarmed protesters, many soldiers and low-level officers began to desert from the Syrian Army. Many soldiers who refused to open fire against civilians were summarily executed by the army. As the uprising progressed, senior military officers and government officials began to defect as well to the opposition.[145] The number of defections would increase during the following months, as army deserters began to group together to form fighting units. Over the course of the uprising and the subsequent civil war, the opposition fighters would become more well-equipped and organized as they receive funds and supplies from foreign nations.

Important defectors included Riad al-Asaad, who would become the commander of the main rebel army, Manaf Tlass, a former brigadier general of the Republican Guard, Riyad Farid Hijab, the former prime minister of Syria, Nawaf al-Fares, the Syrian ambassador to Iraq, and many more. In mid-September 2012, Israeli media claimed that one of Assad's relatives, Yousef Assad, also a high ranking Syrian Air Force officer, announced his defection to the opposition.[146] This was the first defection of a close relative of Assad in the 18-month conflict. Some analysts claimed that these defections were signs of Assad's weakening inner circle.[147]

Protests and military sieges

As the protests and unrest continued, the Syrian government began launching major military operations to suppress resistance. This signaled a new phase in the uprising, as the government response changed from a mix of concessions and force to violent repression. On 25 April, Daraa, which had become a focal point of the uprising, was one of the first cities to be besieged by the Syrian Army. An estimated hundreds to 6,000 soldiers were deployed, firing live ammunition at demonstrators and searching house to house for protestors.[148] Tanks were used for the first time against protestors, and snipers took positions on rooftops. Mosques used as headquarters for demonstrators and organizers were especially targeted.[148] Security forces began shutting off water, power and phone lines, and confiscating flour and food. Clashes between the army and opposition forces, which included armed protestors and defected soldiers, led to the death of hundreds.[149] About 600 people were arrested during the crackdown.[150] By 5 May, most of the protests had been suppressed, and the military began pulling out of Daraa. However, some troops remained to keep the situation under control.

During the crackdown in Daraa, the Syrian Army also besieged and blockaded several towns and suburbs around Damascus. Throughout May, situations similar to those that occurred in Daraa were reported in other besieged towns and cities, such as Baniyas, Homs, Talkalakh, Latakia, and several other towns.[151][152] After the end of each siege, the violent suppression of sporadic protests in the area continued throughout the following months.[153][154]

The military crackdown, led by an Alawite government, worsened tensions between Sunnis and Alawites in the country. A 17 May report of claims by refugees coming from Telkalakh on the Lebanese border indicated that sectarian attacks may have been occurring. Sunni refugees said that uniformed Alawite Shabiha militiamen were killing Sunnis in the town of Telkalakh. As the uprising progressed, sectarian elements increasingly emerged from the conflict.[155]

In June, the Syrian Army expanded operations, and besieged Rastan and Talbiseh. Some besieged cities and towns were described having famine-like conditions.[156] The army also besieged the northern cities of Jisr ash-Shugur[157] and Maarat al-Numaan near the Turkish border.[158] The Syrian Army claimed the towns were the site of mass graves of Syrian security personnel killed during the uprising and justified the attacks as operations to rid the region of "armed gangs",[159] though local residents claimed the dead Syrian troops and officers were executed for refusing to fire on protesters.[160] On 30 June, large protests erupted against the Assad government in Aleppo, Syria's largest city, which were labeled the "Aleppo volcano".[161]

On 3 July, Syrian tanks were deployed at Hama two days after the city witnessed the largest demonstration against Bashar al-Assad.[162] Attacks on protests continued throughout July, with government forces repeatedly firing at protesters and employing tanks against demonstrations, as well as conducting arrests. On 31 July, a nationwide crackdown nicknamed the "Ramadan Massacre" resulted in the death of at least 142 people and hundreds of injuries.[163]

Formation of opposition groups

On 29 July, a group of defected officers announced the formation of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), which would become the main opposition army. Composed of defected Syrian Armed Forces personnel and civilian volunteers, the rebel army seeks to remove Bashar al-Assad and his government from power. This began a new phase in the conflict, with more armed resistance against the government crackdown. The FSA would grow in size, to about 20,000 by December, and to an estimated 40,000 by June 2012.[164]

By October, the FSA would start to receive military support from Turkey, who allowed the rebel army to operate its command and headquarters from the country's southern Hatay province close to the Syrian border, and its field command from inside Syria.[30] The FSA would often launch attacks into Syria’s northern towns and cities, while using the Turkish side of the border as a safe zone and supply route. A year after its formation, the FSA would gain control over many towns close to the Turkish border.

On 23 August, a coalition of anti-government groups was formed, the Syrian National Council. The group, based in Turkey, attempted to organize the opposition. However, the opposition, including the FSA, remained a fractious collection of political groups, longtime exiles, grass-roots organizers and armed militants, divided along ideological, ethnic or sectarian lines.[165]

Throughout August, Syrian forces stormed major urban centers and outlying regions, and continued to attack protests. On 14 August, the Siege of Latakia continued as the Syrian Navy for the first time became involved in the military crackdown. Gunboats fired heavy machine guns at waterfront districts in Latakia as ground troops and security agents backed by armor stormed several neighborhoods, causing up to 28 deaths.[166] Throughout the next few days, the siege dragged on, with government forces and shabiha militia continuing to fire on civilians in the city, as well as throughout the country. The Eid ul-Fitr celebrations, started in near the end of August, were reportedly muted after security forces fired on large demonstrations in Homs, Daraa, and the suburbs of Damascus.[167]

During the first six months of the uprising, the inhabitants of Syria's two largest cities, Damascus and Aleppo, remained largely uninvolved in the anti-government protests.[168] The two cities' central squares have seen rallies in the tens of thousands in support of Assad and his government.[169] Analysts and even opposition activists themselves acknowledge that without mass participation in the protest movement from these two cities, the government will survive and avoid the fate of its counterparts in Egypt and Tunisia.[169]

Armed clashes

As military defections increased, sporadic clashes began to occur between the defectors and security forces. On 8 September, the Syrian Army raided the home of the brother of army defector Colonel Hussein Harmouche, one of the first defecting officers. The operation in Idlib province resulted in the death of three defectors and six Syrian Army soldiers. Around this time, defectors in the province and elsewhere began to group together and target Syrian Army patrols. Protests still continued, but they were often dispersed with gunfire by security forces and pro-government militias.[170]

The first major confrontation between the FSA and the Syrian armed forces occurred in Rastan. From 27 September to 1 October, Syrian government forces, backed by tanks and helicopters, led a major offensive on the town of Rastan in Homs province, which had been under opposition control for a couple weeks.[171] There were reports of large numbers of defections in the city, and the FSA reported it had destroyed 17 armoured vehicles during clashes in Rastan, using RPGs and booby traps.[172] One rebel brigade reported that it killed 80 loyalist soldiers in fighting.[173] A defected officer in the Syrian opposition claimed that over a hundred officers had defected as well as thousands of conscripts, although many had gone into hiding or home to their families, rather than fighting the loyalist forces.[172] The 2011 Battle of Rastan between the government forces and the FSA was the longest and most intense action up until that time. After a week of fighting, the FSA was forced to retreat from Rastan.[162] To avoid government forces, the leader of the FSA, Col. Riad Asaad, retreated to the Turkish side of Syrian-Turkish border.[174]

By the beginning of October, clashes between loyalist and defected army units were being reported fairly regularly. During the first week of the month, sustained clashes were reported in Jabal al-Zawiya in the mountainous regions of Idlib province.[175] In mid-October, other clashes in Idlib province include the city of Binnish and the town of Hass in the province near the mountain range of Jabal al-Zawiya.[176][177] In late October, other clashes occurred in the northwestern town of Maarrat al-Nu'man in the province between loyalists and defected soldiers at a roadblock on the edge of the town, and near the Turkish border, where 10 security agents and a deserter were killed in a bus ambush.[178] It was not clear if the defectors linked to these incidents were connected to the FSA.[179]

Throughout October Syrian forces continued to suppress protests, with hundreds of killings and arrests reportedly having taken place. The crackdown continued into the first three days of November. On 3 November, the government accepted an Arab League plan that aims to restore the peace in the country. According to members of the opposition, however, government forces continued their suppression of protests. Throughout the month, there were numerous reports of civilians taken from their homes turning up dead and mutilated, clashes between loyalist troops and defectors, and electric shocks and hot iron rods being used to torture detainees.

The Arab Parliament recommended the suspension of Arab League member state Syria on 20 September 2011, over persistent reports of disproportionate violence against regime opponents and activists during the uprising. A vote on 12 November agreed to formally suspend Syria four days after the vote.[180] Syria remained suspended as the Arab League sent in December a commission "monitoring" Syria's violence on protesters. By the end of January the Arab League suspended its monitoring mission in the country due to worsening conditions and rising violence across the country.[117]

Escalation

In early November, clashes between the FSA and security forces in Homs escalated as the siege continued. After six days of bombardment, the Syrian Army stormed the city on 8 November, leading to heavy street fighting in several neighborhoods. Resistance in Homs was significantly greater than that seen in other towns and cities, resulting in fierce crackdowns by security forces. The city became what the opposition sometimes called the "Capital of the Revolution", as the newly formed FSA began to gain ground and control over several quarters of the city.

November saw increasing rebel attacks, as opposition forces grew in number. Since 14 November, sporadic fighting between armed rebels and security forces began to become more frequent in Hama province and Daraa province.[181] Rebels engaged in ambushes against Syrian soldiers, and security forces conducted raids on towns where opposition forces were suspected to be hiding in. On 16 and 17 November, the FSA launched symbolic, deadly attacks on an air force intelligence complex in the Damascus suburb of Harasta, and the Ba'ath party youth headquarters in Idlib province, using machine guns and RPG's and firearms. In another symbolic attack on 20 November, opposition forces fired rocket-propelled grenades at Ba'ath Party offices in Damascus.[182] On 25 November The FSA attacked on an airbase in Homs province, causing several personnel casualties.

Throughout December, heavy clashes between security and opposition forces continued across the country, especially in Daraa, Homs, Idlib, and Hama provinces, where discontent against the government was greater than that in the rest of the country. Opposition forces became more organized as they launch bolder and more sophisticated attacks. On 1 December, FSA fighters killed eight personnel in a raid on an intelligence building in Idlib. On 15 December, opposition fighters ambushed checkpoints and military bases around Daraa, killing 27 soldiers, in one of the largest attacks yet on security forces.[183] However, the opposition received setbacks as well. On 19 December, the FSA suffered its largest loss of life when new defectors tried to abandon their positions and bases between the villages of Kensafra and Kefer Quaid in Idlib province, leading to 72 defectors killed.[184]

By early 2012 daily protests had dwindled, eclipsed by the spread of armed conflict[185]: January saw intensified clashes around the suburbs of Damascus, with the Syrian Army use of tanks and artillery becoming common. Fighting in Zabadani began on 7 January when the Syrian Army stormed the town in an attempt to rout out FSA presence. After first phase of the battle ended with a ceasefire on 18 January, leaving the FSA in control of the town,[186] the FSA launched an offensive into nearby Douma. Fighting in the town lasted from the 21 to 30 January, before the rebels were forced to retreat as result of a government counteroffensive. Although, the Syrian Army managed to retake most of the suburbs, sporadic fighting continued.[187]

Fighting erupted in Rastan again on 29 January, when dozens of soldiers manning the town's checkpoints defected and began opening fire on troops loyal to the government. After days of battle, opposition forces gained complete control of the town and surrounding suburbs on 5 February. In a bombing attack on buildings used by Syrian military intelligence in Aleppo, at least 28 people died and 235 were injured on 10 February 2012. It was unclear who the perpetrator of the attack was due to conflicting claims.[188]

By February, intense fighting continued in Homs, as rebels claimed to have gained control over two-thirds of the city. However, starting in 3 February, the Syrian army launched a major offensive to retake rebel-held neighborhoods. In early March, after weeks of artillery bombardments and heavy street fighting, the Syrian army eventually captured the district of Baba Amr, a major rebel stronghold. The Syrian Army also captured the district of Karm al-Zeitoun by 9 March, where activists claimed that government forces killed 47 women and children. By the end of March, the Syrian army retook control of half a dozen districts, leaving them in control of 70 percent of the city.[189]

Ceasefire attempt

Kofi Annan's peace plan provided for a ceasefire, but even as the negotiations for it were being conducted, Syrian armed forces attacked a number of towns and villages, and summarily executed scores of people.[190]: 11 Incommunicado detention, including of children, also continued.[191] On 12 April, both sides, the Syrian Government and rebels of the FSA entered a UN mediated ceasefire period. It was a failure, with infractions of the ceasefire by both sides resulting in several dozen casualties. Acknowledging its failure, Annan called for Iran to be "part of the solution", though the country has been excluded from the Friends of Syria initiative.[192] The peace plan practically collapsed by early June and the UN mission was withdrawn from Syria. Annan officially resigned on 2 August 2012.

Renewed fighting

Following the Houla massacre and the consequent FSA ultimatum to the Syrian government, the cease fire practically collapsed towards the end of May 2012, as FSA began nation-wide offensives against the government troops. On 1 June, the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad vowed to crush an anti-regime uprising, after the rebel FSA announced that it was resuming "defensive operations".[195]

On 2 June, 57 soldiers were killed in Syria, the largest number of casualties the military has suffered in a single day since the uprising broke out in mid-March 2011.[195]

Since 5 June, the Syrian army has been battling rebels around the city of Latakia, using tanks and helicopter gunships.[196]

On 6 June, 78 civilians were killed in the Al-Qubeir massacre. According to activist sources, government forces started by shelling the village before pro-government militia, the Shabiha, moved in.[197] The UN observers rushed to the village in a hope to investigate the alleged massacre but were met with a road-block and small arms fire before the village and were forced to retreat.[198][199]

At the same time, the conflict has started moving into the two largest cities (Damascus and Aleppo) that the government claimed were being dominated by the silent majority, which wanted stability, not government change. In both places there has been a revival of the protest movement in its peaceful dimension. Shopkeepers across the capital staged a general strike and in several Aleppo commercial districts mounted a similar but smaller protest. This has been interpreted by some as indicating that the historical alliance between the government and the business establishment in the large cities has become weak.[200]

On 22 June, a Turkish F-4 fighter jet was shot down by Syrian government forces.[201] Both pilots were killed.[202] Syria stated that it had shot the fighter down using anti-aircraft artillery near the village of Om al-Tuyour, while it was flying over Syrian territorial waters one kilometre away from land.[203] Turkey's foreign minister stated the jet was shot down in international airspace after accidentally entering Syrian airspace, while it was on a training flight to test Turkey's radar capabilities.[204] Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan vowed retaliation, saying: "The rules of engagement of the Turkish Armed Forces have changed ... Turkey will support Syrian people in every way until they get rid of the bloody dictator and his gang."[205] Ankara acknowledged that the jet had flown over Syria for a short time, but said such temporary overflights were common, had not led to an attack before, and alleged that Syrian helicopters had violated Turkish airspace five times without being attacked and that a second, search-and-rescue jet had been fired at.[205][206] Assad later expressed regret over the incident.[207] In August 2012, reports appeared in some Turkish newspapers claiming that the Turkish General Staff had deliberately misinformed the Turkish government about the fighter's location when it was shot down. The reports said that a NATO command post at Izmir and a British base in Cyprus had confirmed that the fighter was shot down inside Syrian waters and that radar intelligence from U.S. forces had disproved any "accidentally entered Syrian waters" flightpath error. The General Staff denied the claims.[208]

Attempts by the international community to agree a transitional government of national unity failed at the beginning of July after Russia insisted the agreement should not preclude Assad from being part of it.[209] Syrian opposition groups rejected the UN-brokered peace plan, arguing that it was ambiguous and vowing not to negotiate with President Assad or members of his regime.[210]

Battles of Damascus and Aleppo

By mid-July fighting had spread across the country. Acknowledging this, the International Committee of the Red Cross declared the conflict a civil war.[211] Fighting in Damascus intensified, with a major rebel push to take the city.[212]

On 18 July, Syrian Defense Minister Dawoud Rajiha, former defense minister Hasan Turkmani, and the president's brother-in-law General Assef Shawkat were killed by a bomb attack in the city.[213][214] The Syrian intelligence chief Hisham Ikhtiyar who was injured in the same explosion later succumbed to his wounds.[215] Both the FSA and Liwa al-Islam claimed responsibility for the assassination.[216] The fate of the interior minister Mohammad al-Shaar was initially the subject of conflicting reports,[213] variously reporting him as injured but alive,[217] and dead.[218] There were also rumors that President Assad may also have been injured in the attack due to his lack of recent public appearance, but days after images of the President since the attack surfaced.[219] The assassinations were the first of such high-ranking members of Assad's elite in the 17-month revolt. In an interview later that month, General Mohammad Al-Zobi of the rebel forces stated that the explosion had been carried out using 15 kilos of explosives smuggled into the building, then detonated remotely.[220]

On 19 July, Russia and China vetoed a U.N. resolution that would add sanctions against the Syrian government, showing again the divide in international opinion towards the conflict.[221] Russia and China, who are major trade allies with Syria, want to see a more balanced resolution calling on both sides to equally halt violence.[222] On the same day, Iraqi officials reported that the FSA has gained control of all four border checkpoints between Syria and Iraq, increasing concerns of the safety of Iraqis trying to escape the violence in Syria.[223]

The conflict reached a decisive phase in late July. Government forces managed to break the rebel offensive on Damascus, by pushing out most of the opposition fighters. After this, the focus shifted to the battle for control of Aleppo.[224]

On 25 July, multiple sources reported that the Assad government was using fighter jets to attack rebel positions in the cities of Aleppo and Damascus.[225] On 1 August, the UN observers in Syria witnessed government fighter jets firing on rebels in Aleppo, the country's largest city.[226]

In early August, the rebels suffered setbacks. The FSA offensive to capture Aleppo was repelled, and the Syrian Army recaptured Salaheddin district, an important rebel stronghold in Aleppo.

On 19 September, rebel forces seized a border crossing between Syria and Turkey in Ar-Raqqah province. Along with several other border crossings into Turkey and one into Iraq, the capture of this one could provide opposition forces strategic and logistical advantages, allowing greater ease transporting supplies into the country.[227]

In late September, the FSA moved its command headquarters from southern Turkey into rebel-controlled areas of northern Syria.[228]

On 3 October 2012, a series of border clashes between Syria and Turkey began with a shell was fired from Syria into the town of Akçakale in Turkey,[229] and five Turkish citizens were killed. In response, specific military targets were shelled in Syria by Turkey. Turkey referred this to NATO, which released a statement condemning the killing of Turkish civilians. It also called for an end to all aggression by the Syrian government. It was unclear where the shell had come from, and whether it was sanctioned directly. The Syrian government later apologised and offered their condolences to the Turkish people. This was the most serious cross-border violence of the Syrian civil war.[230]

On 9 October, rebel forces seized control of Maarat al-Numan, a strategic town in Idlib province on the highway linking Damascus with Aleppo.[231]

By 18 October, the FSA had captured most of Douma, the biggest suburb of Damascus. Fighting and bombardments continue in the town.[232]

On 22 October, a Jordanian soldier died during a gunfight between Jordanian troops and Islamic militants attempting to cross the border into Syria. Sameeh Maaytah, the Information Minister of Jordan, said the soldier was the first Jordanian military personnel to be killed in clashes connected to the civil war in Syria.[57]

Second ceasefire attempt

On 25 October, the Syrian government announced via its state media that it would suspend military operations from 26 to 29 October, during Muslim Eid al-Adha holiday, as part of a ceasefire proposal mediated by U.N. special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi, who replaced Annan in August. [233] However, the army also announced that it would respond to any attacks. Some rebel groups agreed to the proposal, while others did not. Many Syrian Muslims said that they could not celebrate the holiday due to the fighting. On the first day of the ceasefire agreement, fighting continued across Syria, causing several deaths.[234]

Non-state parties in the conflict

Shabiha

The Shabiha is a militia network established in the 1970s and led by Alawites connected to the Assad family. Since the uprising, the Syrian government has frequently used the group to break up protests and enforce laws in restive neighborhoods.[235]

Shabiha have been described as "a notorious Alawite paramilitary, who are accused of acting as unofficial enforcers for Assad's regime";[236] "gunmen loyal to Assad";[237] "semi-criminal gangs comprised of thugs close to the regime".[237] Some "shabiha" operating in Aleppo have been reported to be Sunni, however.[238] Bassel al-Assad is reported to have created the secretive militia for the government in times of crisis.[239]

According to a Syrian citizen, shabiha is a term that was used to refer to gangs involved in smuggling during the Syrian occupation of Lebanon: "They used to travel in ghost cars without plates; that's how they got the name Shabbiha. They would smuggle cars from Lebanon to Syria. The police turned a blind eye, and in return Shabbiha would act as a shadow militia in case of need".[240] Witnesses and refugees from the northwestern region say that the shabiha have been intimately involved in the killing, looting and destruction.[240][241]

Free Syrian Army

In late July 2011, a web video featuring a group of uniformed men claiming to be defected Syrian Army officers proclaimed the formation of a Free Syrian Army (FSA). In the video, the men called upon Syrian soldiers and officers to defect to their ranks, and said the purpose of the Free Syrian Army was to defend protesters from violence by the state.[9] Many Syrian soldiers subsequently deserted to join the FSA.[242] The actual number of soldiers who defected to the FSA is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 1,000 to over 25,000 as of December 2011.[243] Nir Rosen, who spent time with the FSA in Syria, claims the majority of its members are civilians rather than defectors, who had taken up arms long before the formation of the FSA was announced. He also stated they have no central leadership.[244] The FSA functions more as an umbrella organization than a traditional military chain of command, and is "headquartered" in Turkey. As such, it cannot issue direct orders to its various bands of fighters, but many of the most effective armed groups are fighting under the FSA's banner.

As deserting soldiers abandoned their armored vehicles and brought only light weaponry and munitions, FSA adopted guerilla-style tactics against security forces inside cities. Its primary target has been the shabiha militias. Most FSA attacks however are directed against trucks and buses that are believed to bring security reinforcements. Sometimes the vehicle occupants are taken as hostages, in other cases the vehicles are attacked either with roadside bombs or through hit-and-run attacks. The FSA has also targeted power lines and water mains in "retaliation against Hezbollah's provocations".[245] To encourage defection, the FSA began attacking army patrols, shooting the commanders and trying to convince the soldiers to switch sides. FSA units have also acted as defense forces by guarding neighborhoods rife with opposition, guarding streets while protests take place, and attacking shabiha members. However, the FSA engaged in street battles with security forces in Deir ez-Zor, Al-Rastan, and Abu Kamal. Fighting in these cities raged for days, with no clear victor. In Hama, Homs, Al-Rastan, Deir ez-Zor, and Daraa, the Syrian military used airstrikes against them, leading to calls from the FSA for the imposition of a no-fly zone.[246]

More than 3,000 members of the Syrian security forces have been killed, which the Syrian government states is due to "armed gangs" being among the protesters, yet the opposition blames the deaths on the government.[247] Syrians have been crossing the border to Lebanon to buy weapons on the black market since the beginning of the protests.[248] Clan leaders in Syria claim that the armed uprising is of a tribal, revenge-based nature, not Islamist.[249] On 6 June, the government said more than 120 security personnel were killed by "armed gangs"; 20 in an ambush, and 82 in an attack on a security post.[250] The main centers of unrest have been described as being predominately Sunni Muslim towns and cities close to the country's borders where smuggling has been common for generations, and thus have more access to smuggled weapons.[251]

Daniel Byman believes the political and military opposition are each worryingly divided and disconnected from each other,[252] and thus uniting, training and pushing the armed opposition to avoid religious sectarianism is crucial. The latter is important, for otherwise the Alawites and other minorities will fight all the harder, and make post-Assad Syria more difficult to govern.[253] Others would say that part of Byman's analysis represents a failure to understand that the leadership within Syria is decentralised out of necessity, that this is a good thing, and that decentralisation is not the same thing as fragmentation, and certainly does not represent an absence of strong leadership.[254] Whichever view one accepts, there are undeniably rivalries between different strands and disagreement between those advocating peaceful protests and those backing armed struggle.[255][256]

Syrian National Council

The Syrian opposition met several times in conferences held mostly in Turkey and formed a National Council.

The Federation of Tenseekiet Syrian Revolution helped in the formation of a Transitional National Assembly on 23 August in Istanbul "to serve as the political stage of the Revolution of the Syrian people". The creation of the Syrian National Council was celebrated by the Syrian protestors since the Friday protest following its establishment was dubbed "The Syrian National Council Represents Me".[257][258] The Syrian National Council gained the recognition of a few countries, including "sole legitimate interlocutor" by the United States.[259] The SNC is said to have developed a debilitating democratic deficit, and some opposition actors on the ground in Syria subsequently refuse to work with it.[260]: 5–9

Organized crime

Sanctions from the US, EU, and the Arab League significantly hindered the Syrian economy, especially international trade. In response, the Syrian government began to work more with criminal organizations, who smuggle goods and money in and out of the country. Syria has experience with working with criminal groups for profit, sometimes offering them protection. During the Syrian occupation of Lebanon, members of the Syrian government ran drug production and counterfeiting operations that resulted in an estimated $500 million of profit per year. The economic downturn caused by the conflict and sanctions also led to lower wages for Shabiha members. In response, some Shabiha members began stealing civilian properties, and engaging in kidnappings.[235]

Rebel forces sometimes relied on criminal networks to obtain weapons and supplies. Black market weapon prices in Syria’s neighboring countries have significantly increased since the start of the conflict. To generate funds to purchase arms, some rebel groups have turned towards extortion, stealing, and kidnapping.[235]

Sectarianism

At the uprising's outset, some protesters reportedly chanted "Christians to Beirut; Alawites to the coffin".[261][262] While many in the opposition view the conflict as a sectarian one, some have accused the government of fomenting sectarianism;[263] Due to Turkey's stance regarding the civil war, the government has been accused of persecuting Turkmens living in Syria.[264]

The rising sectarianism feared against the Alawite community has led to speculation of a re-creation of the Alawite State as a safe haven for Assad and the leadership should Damascus finally fall. Latakia province and Tartus province both have Alawite majority population and historically made up the Alawite State that existed between 1920–1936. These areas have so far remained relatively peaceful during the Syrian civil war. The re-creation of an Alawite State and the breakup of Syria is however seen critically by most political analysts.[265][266] King Abdullah II of Jordan has called this scenario the "worst case" for the conflict, fearing a domino effect of de-fragmentation of the country along sectarian lines with consequences to the wider region.[267]

The Global Post reported that Christians living in Aleppo started to arm themselves, often supplied by the Syrian Army. Christians feared the Islamists and the scenario that happened to the Christians in Iraq.[268] 80,000 Christians 'cleansed' from their homes in Homs Province by the Free Syrian Army in March have gradually given up the prospect of ever returning home according to an op-ed piece in the New York Times.[269]

In a TIME report, an anti-Assad activist claimed that the Syrian government had paid government workers to write anti-Alawite graffiti and chant sectarian slogans at opposition rallies.[264] Alawites who have taken refugee at the coast and in the Alawite mountains as well as in Lebanon have also told journalists that they were offered money by the Syrian government to spread sectarianism through chants and graffiti.[264]

In October 2012, fighting broke out between the Assads and the Othman Alawite clans in the Assad's hometown of Qardaha over whether or not to support Bashar Assad. Locals claim that fighting began when a local from the Othman clan protested the war to Mohammed Assad, Assad's father and alleged Shabiha leader. Mohammed al Assad was greatly angered by this, and attacked the family's home with several other gunmen. Not long after, a shootout ensued between the Othmans and Mohammed Assad, resulting in Mohammed Assad being seriously injured and sent to the hospital, with his current status unknown. Several members from the Othman clan were killed. Protests against Assad began popping up in Qardaha and Latakia, and the Syrian army sent soldiers and tanks to try quell dissent in Qardaha.[270]

In October 2012, various Iraqi religious sects join the conflict in Syria on both sides. Sunnis from Iraq, have traveled to Syria to fight against President Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian government.[271] Also, Shiites from Iraq, in Babil Province and Diyala Province, have traveled to Damascus from Tehran, or from the Shiite holy city of Najaf, Iraq to protect Sayyida Zeinab, an important Shiite shrine in Damascus.[271] According to Abu Mohamed, with the Sadrist Trend, said he recently received an invitation from the Sadrists' leadership to discuss the shrine in Damascus.[271] A senior Sadrist official and former member of Parliament, speaking said that convoys of buses from Najaf, under the cover story of pilgrims, were carrying weapons and fighters to Damascus.[271] Some of the pilgrims were members of Iran's elite Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.[271] Some Shiites "describe the Syrian conflict as the beginning of the fulfillment of a Shiite prophecy that presages the end of time by predicting that an army, headed by a devil-like figure named Sufyani, will rise in Syria and then conquer Iraq's Shiites."[271] According to Hassan al-Rubaie, a Shiite cleric from Diyala Province, said, "The destruction of the shrine of Sayyida Zeinab in Syria will mean the start of sectarian civil war in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia." [271]

Kurdish stance

Syrian Kurds represented 10% of Syria's population at the start of the uprising. They had suffered from decades of discrimination and neglect, being deprived of basic civil, cultural, economic and social rights. Additionally, since 1962, they and their children had been denied Syrian nationality, a situation that led to other problems relating to personal status and an inability to seek employment in the public sector.[272]: 7 When protests began, Assad's government, in an effort to try and neutralise potential Kurdish opposition, finally granted citizenship to an estimated 200,000 stateless Kurds.[273] This concession on citizenship, combined with Turkish endorsement of the opposition and Kurdish under-representation in the Syrian National Council, has meant that Kurds have participated in the civil war in smaller numbers than their Syrian Arab counterparts.[273][274] Consequently, violence and repression in Kurdish areas has been less severe.[273][275] According to Ariel Zirulnick of the Christian Science Monitor, the Assad government "has successfully convinced many of Syria's Kurds and Christians that without the iron grip of a leader sympathetic to the threats posed to minorities, they might meet the same fate" as minorities in Lebanon and Iraq.[276] In terms of a post-Assad Syria, Kurds reportedly desire a degree of autonomy within a decentralised state.[277]

On 7 October 2011, prominent Kurdish rights activist Mishaal al-Tammo was assassinated when masked gunmen burst into his flat, with the Syrian government blamed for his death. At least 20 other civilians were also killed during crackdowns on demonstrations across the country. The next day, more than 50,000 mourners marched in Al-Qamishli to mark Tammo's funeral, and at least 14 were killed when security forces fired on them.[278]

In 2012, several cities with large Kurdish populations, such as Qamishli and Al-Hasakah, began witnessing protests of several thousand people against the Syrian government, which responded with tanks and fired upon the protesters.[279]

Some in the opposition have claimed that the PKK, a Kurdish separatist group in Turkey, is helping the Syrian government in the conflict. However, Murat Karayilan, the leader of the PKK, has denied such claims, stating that the Kurds in Syria do not support either side.[280]

In May 2012, a delegation of the Kurdish National Council (KNC), a coalition of ten Syrian-Kurdish parties established in October 2011, was invited to Washington for talks. Amongst others the delegation met Robert Ford, the former U.S. ambassador to Syria.[281]

On 15 June, it was reported that Kurds had helped government soldiers defeat FSA fighters in the town of Atma.[282] However, the head of Kurdish Democratic Party (PYD) Salih Muslim, whose militia now control much of Kurdish territories, claims that their group is not fighting on government side, but rather keeping the Kurdish territory out of FSA control in order to protect its citizens from Syrian army response. He also described Syrian regime as brutal, not intending to leave power until it kills all Syrians.[283]

On 19 July, Kurdish militias from Kurdish Democratic Union Party and Kurdish National Council forced out government forces from several areas, including town of Ayn al-Arab, or Kobanê in Kurdish. Kurdish militias then denied access of FSA whose fighters came upon hearing news of Kurdish victory, arguing that Kurds can take care of Kurdish areas alone. Nuri Brimo, spokesperson for the Kurdish Democratic Party announced that "liberation" of Kobane is beginning of battle for whole Syrian Kurdistan.[284][285]

Palestinians

The reaction of the approximately 500,000[286] Palestinians living in Syria has been mixed: many just want to stay out of the situation, some (particularly younger people) have actively supported the protests, but the PFLP-General Command is widely accused of actively supporting the repression (Assad has sheltered the group for years). Due to this, six Palestinian officers were assassinated between January and June 2012.[287] Some individual Palestinian militias have given their to support to the government as well, including one based in the Yarmouk Camp in Damascus. However, ongoing government attacks and shelling have been fostering pro-rebel sympathies among some Syrian Palestinians, according to an early September New York Times report.[286]

Foreign involvement

International reaction

The conflict in Syria received significant international attention. The Arab League,[288] European Union,[289] Secretary-General of the United Nations,[290] and many Western governments condemned the Syrian government's violent response to the protests, and many expressed support for the protesters' right to exercise free speech.[291] Russia and China consistently rejected any United Nations resolution that would impose sanctions on Syria.[292] Russia denounced the use of violence by the opposition, and claimed that "terrorists" are present within its ranks.[293] Iran also expressed support for Assad.[165] Both the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League have suspended Syria from membership.

Military support

Turkey, once an ally of Syria, has condemned Assad over the violent crackdown and has requested his departure from office. In October 2011, Turkey began sheltering the Free Syrian Army, offering the group a safe zone and a base of operation. Together with Saudi Arabia and Qatar, Turkey has also provided the rebels with arms and other military equipment. Tensions between Syria and Turkey significantly worsened after Syrian forces shot down a Turkish fighter jet in June 2012 and minor border clashes in October.[165]

In 2012, the United States,[294] United Kingdom[295] and France[296] provided opposition forces with non-lethal military aid, including communications equipment and medical supplies. The U.K. was also reported to have provided intelligence support from its Cyprus bases, revealing Syrian military movements to Turkish officials, who then pass on the information to the FSA.[297] The CIA was reported to be involved in covert operations along the Turkish-Syrian border, where agents investigated rebel groups, recommending arms providers which groups to give aid to. Agents also helped opposition forces develop supply routes, and provided them with communications training.[298] The majority of the weapons provided to rebel forces by Saudi Arabia and Qatar have ended up in the hands of hardline Islamic jihadists. It is widely argued and a fear exists that the advance weapons manufactured in USA are ending up in the hands of terrorists, who will create problem elsewhere once the Syrian Uprising comes to a close. [16]

Russia, whose Tartus naval base in Syria is its only one outside the former Soviet Union, has supplied the Syrian government with arms as part of a business contract signed before the uprising began. Russia has also sent military and technical advisers to train Syrian soldiers to use the Russian-made weapons and to help repair and maintain Syrian weapons.[299] Western diplomats have frequently criticized Russia's behavior, but Russia denied its actions have violated any international law. Russian President Vladimir Putin has claimed that Russia does not support either side.[300] However, a Syrian jetliner returning from Moscow in October 2012 was forced to land in Ankara, the Turkish capital, and the government of Turkey announced hours later that Russian munitions and military equipment had been discovered aboard the aircraft and confiscated.[301] The Russian Foreign Ministry denied that the cargo of the plane was sold to the Syrian military by the Russian government and claimed that its shipping did not violate international sanctions, contrary to the Turkish assertion.[302] Later in October 2012, the Russian military demanded an inquiry into the source of the Syrian rebels' U.S.-made Stinger surface-to-air missiles.[303]

Iran, an ally of Syria, has not only provided Syria with arms and technical support, but has also sent combat troops, specifically the Revolutionary Guards, to support Syrian military operations.[304] It was reported that Iran also trained fighters from Hezbollah, a militant group based in Lebanon.[305] The fighters were deployed to Syria to attack rebels. Iraq, located between Syria and Iran, was criticized by the U.S. for allowing Iran to ship military supplies to Syria over Iraqi airspace.[306]

Some analysts have interpreted the Syrian conflict as part of a regional proxy war between Sunni states, such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, who support the Sunni-led opposition, and Iran and Hezbollah, who support the Alawite-led government in Syria.[307][308]

Impact

In August 2012, the United Nations said 2.5 million people needed help due to the civil war, and more than one million people were internally displaced.[309]

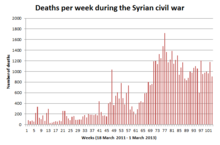

Deaths

Estimates of deaths in the conflict vary, with figures ranging from 30,000[310] to 46,760.[35][64]

One problem has been determining the number of "armed combatants" who have died, due to some sources counting rebel fighters who were not defectors as civilians.[59][311] At least half of those killed have been estimated to be combatants from both sides, including more than 7,200 government soldiers. In addition, UNICEF reported that over 500 children had been killed by early February 2012.[312][313] Another 400 children have been reportedly arrested and tortured in Syrian prisons.[68][69] Both claims have been contested by the Syrian government.[314] Additionally, over 600 detainees and political prisoners have died under torture.[315] In mid-October 2012, the opposition activist group SOHR reported the number of children killed in the conflict had risen to 2,300.[316]

Human rights violations

The "vast majority" of human rights violations, including the international crimes, documented have been committed by the Syrian armed and security forces and their allied militia.[317]: 4 [190]: 10 [318]: 1 [319]: 20 Some violations are considered by many to be so serious, deliberate, and systematic as to constitute crimes against humanity[272]: 5 [190]: 7 [319]: 18–20 [320] and war crimes.[190]: 7 According to Human Rights Watch, the Assad government of creating an "archipelago of torture centers".[321]: 1 The key role in the repression, and particularly torture, is played by the mukhabarat: the Department of Military Intelligence, the Political Security Directorate, the General Intelligence Directorate, and the Air Force Intelligence Directorate.[272]: 9 [321]: 1, 35 Human Rights Watch has also stated it has "evidence of ongoing" and increasing "cluster bomb attacks" by Syria’s air force.[322] The use, production, stockpiling, and transfer of cluster munitions is prohibited by international treaty[323], because of the bombs ability to randomly scattering thousands of submunitions or "bomblets" over a vast area, many of them killing or maiming civilians long after the conflict for which they were intended is over.[324]

In October, Amnesty International published a report stating that at least 30 Syrian dissidents living in Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States, faced intimidation by Syrian embassy officials, and that in some cases, their relatives in Syria were harassed, detained, and tortured. Syrian embassy officials in London and Washington, D.C., were alleged to have taken photographs and videos of local Syrian dissidents and sent them to Syrian authorities, who then retaliated against their families.[325]

With regard to armed opposition groups, the UN accused them of: unlawful killing; torture and ill-treatment; kidnapping and hostage taking; and the use of children in dangerous non-combat roles.[318]: 4–5

Crime wave

As the conflict has expanded across Syria, many cities have been engulfed in a wave of crime as fighting caused the disintegration of much of the civilian state, and many police stations stopped functioning. Rates of thievery increased, with criminals looting houses and stores. Rates of kidnappings increased as well. Rebel fighters were sighted stealing cars and destroying an Aleppo restaurant in which Syrian soldiers had eaten.[326]

As of July 2012, the human rights group Women Under Siege had documented over 100 cases of rape and sexual assault in the conflict, with many of them believed to be perpetrated by the Shabiha and other pro-government militias. Victims included men, women, and children, with about 80% of victims being women and girls.[327][328]

Refugees

The violence in Syria has caused hundreds of thousands to flee their homes, with many seeking safety in nearby countries. Jordan has seen the largest influx of refugees since the conflict began, followed by Turkey, Lebanon, and Iraq. On 9 October 2012, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that the number of Syrian refugees had increased to between 355,000 to 500,000.[58]

Cultural heritage

The civil war has caused damage to both Syrian cultural heritage and World Heritage Sites, which is escalating as the conflict continues. Destruction of antiquities has been caused by shelling, army entrenchment. and looting at various tells, museums, and monuments.[329] A group called Syrian archaeological heritage under threat monitor and record the destruction in an attempt to create a list of heritage sites damaged during Syrian civil war and bring the issue of protection and preservation of Syrian archaeology and architecture to greater world attention.[330]

Effects on Lebanon

The Syrian civil war is spilling into Lebanon, leading to incidents of sectarian violence in northern Lebanon between supporters and opponents of the Syrian government, and armed clashes between Sunnis and Alawites in Tripoli.[331]

On 17 September 2012, Syrian ground-attack aircraft fired three missiles 500 metres (1,600 ft) over the border into Lebanese territory near Arsal. It was suggested that the jets were chasing rebels in the vicinity. The attack prompted Lebanese President Michel Sleiman to launch an investigation, whilst not publicly blaming Syria for the incident.[332]

On 22 September 2012, a group of armed members of the Free Syrian Army attacked a border post near Arsal. The group were chased off into the hills by the Lebanese Army, who detained and later released some rebels due to pressure from dignified locals. President Sleiman praised the actions taken by the military as maintaining Lebanon's position being “neutral from the conflicts of others". He called on border residents to “stand beside their army and assist its members.” Syria has repeatedly called for an intensified crackdown on rebels that it says are hiding in Lebanese border towns.[333][334]

On 11 October 2012, four shells fired by the Syrian military hit Qaa, where previous shelling incidents had caused fatalities.[335]

On 19 October 2012, a car bomb exploded in central Beirut, killing a top Lebanese security official, Wissam al-Hassan. At least 7 others were killed and perhaps 80 were injured in the blast. [336]

Refugee children from Syria have been displaced into the border towns, threatening to overwhelm the Beqaa educational system.[337]

See also

- Modern history of Syria

- Arab Spring

- Timeline of the Syrian civil war

- Syrian Observatory for Human Rights

References

- ^ "Iran's Hizbullah sends more troops to help Assad storm Aleppo, fight Sunnis". World News Tribune. 29 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Saeed Kamali Dehghan (28 May 2012). "Syrian army being aided by Iranian forces". Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Iranian Guards, Mahdi Army troops enter Syria's Druze Mountain". NowLebanon. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Daftari, Lisa (28 August 2012). "Iranian general admits 'fighting every aspect of a war' in defending Syria's Assad". FOX News. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "Battle for Aleppo Intensifies, as World Leaders Pledge New Support for Rebels". New York Times. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ^ "Iraqi Shi'ite militants fight for Syria's Assad". Reuters. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Iraqi Shi'ite militants fight for Syria's Assad

- ^ "Syria rebels 'clash with army, Palestinian fighters'". AFP. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Defecting troops form 'Free Syrian Army', target Assad security forces". The World Tribune. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- ^ "Syrian Rebels Plot Their Next Moves: A TIME Exclusive". TIME. 11 February 2012.

- ^ http://www.dailystar.com.lb/News/Middle-East/2012/Jul-18/181033-palestinians-join-syria-revolt-activists-fsa.ashx#axzz2Aniktc00

- ^ a b c Schmitt, Eric (21 June 2012). "C.I.A. Said to Aid in Steering Arms to Syrian Opposition". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ^ "TIME Exclusive: Meet the Islamist Militants Fighting Alongside Syria's Rebels". Time. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Arab Islamist fighters eager to join Syria rebels". Daily Star. 31 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Sherlock, Ruth (12 July 2012). "Al-Qaeda tries to carve out a war for itself in Syria". Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Sanger, David (14 October 2012). "Rebel Arms Flow Is Said to Benefit Jihadists in Syria". New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "Kurds Give Ultimatum to Syrian Security Forces". Rudaw. 21 July 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Syrian Kurds given military training in northern Iraq, says Barzani". Zaman. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Dougherty, Jill (9 August 2012). "Al-Assad's inner circle, mostly family, like 'mafia'". CNN. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ Fassihi, Farnaz (27 August 2012). "Iran Said to Send Troops to Bolster Syria. Retrieved 2012-23-10". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

- ^ "Top Iranian Official Acknowledges Syria Role". Wall Street Journal. 16 September 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "What Is Iran Doing in Syria?". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "Syria's Assad names Riad Hijab as new prime minister". BBC News. 6 June 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Karadsheh, Jomana (28 July 2012). "Libya rebels move onto Syrian battlefield". CNN. Retrieved 28 July 2012.