Greek government-debt crisis

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Greek government-debt crisis (also known as the Greek Depression)[3][4][5] started in late 2009, as the first of four sovereign debt crises in the eurozone – later referred to collectively as the European debt crisis. The common view holds that it was triggered by the turmoil of the Great Recession, but that the root cause for its eruption in Greece was a combination of structural weaknesses in the Greek economy along with a decade-long pre-existence of overly high structural deficits and debt-to-GDP levels of public accounts.

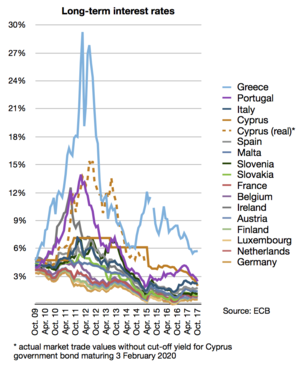

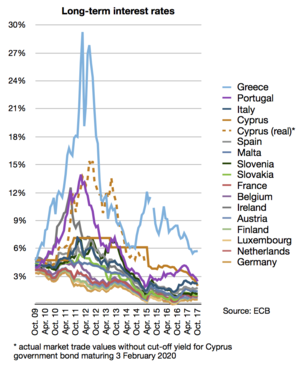

In late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning Greece's ability to meet its debt obligations, due to the revelation that previous data on government debt levels and deficits had been misreported by the Greek government.[6][7][8] This led to a crisis of confidence, indicated by a widening of bond yield spreads and the cost of risk insurance on credit default swaps compared to the other Eurozone countries – Germany in particular.[9][10]

In 2012, Greece's government had the largest sovereign debt default in history. Greece became the first developed country to fail to make an IMF €1.6 billion loan repayment on June 30, 2015.[11] At that time, Greece's government had debts of €323bn.[12]

Overview

2010–2014

In April 2010, adding to news of the recorded adverse deficit and debt data for 2008 and 2009, the national account data revealed that the Greek economy had also been hit by three distinct recessions (Q3-Q4 2007, Q2-2008 until Q1-2009, and a third starting in Q3-2009),[13] which equaled an outlook for a further rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio from 109% in 2008 to 146% in 2010. Credit rating agencies responded by downgrading the Greek government debt to junk bond status (below investment grade), as they found indicators of a growing risk of a sovereign default, and the government bond yields responded by rising into unsustainable territory – making the private capital lending market inaccessible as a funding source for Greece.

On 2 May 2010, the European Commission, European Central Bank (ECB) and International Monetary Fund (IMF), later nicknamed the Troika, responded by launching a €110 billion bailout loan to rescue Greece from sovereign default and cover its financial needs throughout May 2010 until June 2013, conditional on implementation of austerity measures, structural reforms, and privatization of government assets.[14] A year later, a worsened recession along with a delayed implementation by the Greek government of the agreed conditions in the bailout programme revealed the need for Greece to receive a second bailout worth €130 billion (including a bank recapitalization package worth €48bn), while all private creditors holding Greek government bonds were required at the same time to sign a deal accepting extended maturities, lower interest rates, and a 53.5% face value loss. [citation needed]

The second bailout programme was finally ratified by all parties in February 2012, and by effect extended the first programme, meaning a total of €240 billion was to be transferred at regular tranches throughout the period of May 2010 to December 2014. Due to a worsened recession and continued delay of implementation of the conditions in the bailout programme, in December 2012 the Troika agreed to provide Greece with a last round of significant debt relief measures, while the IMF extended its support with an extra €8.2bn of loans to be transferred during the period of January 2015 to March 2016.

The fourth review of the bailout programme revealed development of some unexpected upcoming financing gaps.[15][16] Due to an improved outlook for the Greek economy, with achievement of a government structural surplus both in 2013 and 2014 – along with a decline of the unemployment rate and return of positive economic growth in 2014,[17][18] it was possible for the Greek government to regain access to the private lending market for the first time since eruption of its debt crisis – to the extent that its entire financing gap for 2014 was patched through a sale of bonds to private creditors.[19]

The improved economic outlook was replaced by a new fourth recession starting in Q4-2014,[20] related to the premature snap parliamentary election called by the Greek parliament in December 2014 and the following formation of a Syriza-led government refusing to respect the terms of its current bailout agreement.[21] The rising political uncertainty of what would follow, caused the Troika to suspend all scheduled remaining aid to Greece under its current programme – until such time when the Greek government either accepted the previously negotiated conditional payment terms or alternately could reach a mutually accepted agreement of some new updated terms with its public creditors.[22] This rift caused a renewed and increasingly growing liquidity crisis (both for the Greek government and Greek financial system), resulting in plummeting stock prices at the Athens Stock Exchange, while interest rates for the Greek government at the private lending market spiked, making it once again inaccessible as an alternative funding source.

2015

After the election, the Eurogroup granted a further four-month technical extension of its current bailout programme to Greece; accepting the payment terms attached to its last tranche to be renegotiated with the new Greek government before the end of April,[23] so that the review and last financial transfer could be completed before the end of June 2015.[24] The new renegotiation deal was still pending by the end of May.[25][26]

Faced by the threat of sovereign default, some final attempts for reaching a renegotiated bailout agreement were made by the Greek government in the first half[27] and second half of June 2015.[28] Default would inevitably entail enforcement of recessionary capital controls to avoid a collapse of the banking sector – and potentially could lead to exit from the eurozone, due to growing liquidity constraints making continued payment of public pension and salaries impossible in euro.[29][30]

According to a statement by the Eurogroup, Greece excluded, the Greek government unilaterally broke off the ongoing program negotiations with the Troika late on the 26 June,[31][32][33] diverting from their prior agreement to continue negotiating until a mutually acceptable compromise could be presented to the Eurogroup in the afternoon of 27 June.[34] A few hours later, Alexis Tsipras announced on national television that instead, a referendum would be held on July 5th, 2015 to approve or reject the achieved preliminary negotiation result (the latest counter proposal submitted and offered by the Troika on 25 June) for a new set of updated terms ensuring completion of the second bailout agreement.[35]

The Greek government signaled it would campaign for rejection of the new offered terms in such referendum, while four opposition parties (PASOK, To Potami, KIDISO and New Democracy) objected the call for the proposed referendum because it would be unconstitutional, and plead for the Greek parliament or Greek president to reject the referendum proposal on this ground.[36] Meanwhile, the Eurogroup notified the existing second bailout agreement would technically expire on 30 June (as regulated by its "20 February statement"), if not updated prior this date by a new agreement setting up some mutually agreed updated terms, rendering it too late for Greece to arrange a referendum on updated terms five days after its expiry.[32][34]

The Eurogroup clarified at its press conference on June 27th, that the only imaginable scenario in which the Eurogroup perhaps could offer Greece further flexibility through a new technical extension of its bailout program to pave the way for holding the proposed Greek bailout referendum on July 5th, would be if the Greek government prior of 30 June settled a final renegotiated deal with the Troika on a set of mutually agreed updated terms for program completion – subject to the final approval by its proposed bailout referendum on July 5th. The reason for this firm stance was that the Eurogroup wanted the Greek government to take some ownership for the subsequent program's completion at the new, updated terms, assuming that the referendum was held and resulted in approval.[37]

As for the Greek authorities' continued call in negotiations to be granted additional debt relief, the Eurogroup had signaled willingness to uphold their "November 2012 debt relief promise" still to be valid after reaching agreement for updated terms for completion of the second program.[28] This promise is a guarantee which holds that if Greece completes its second program and if Greece's debt-to-GDP ratio subsequently gets forecast to be over 124% in 2020 or 110% in 2022 for any reason, then the Eurozone will implement a debt-relief large enough to ensure that these two targets will still be met.[38]

On June 28th, 2015, the referendum was approved by the Greek parliament, and ECB decided to maintain availability of its Emergency Liquidity Assistance to Greek banks at its current level, as it was still considered politically possible for Greece to ensure extension of its pre-required current bailout program (at least until 30 June). As many Greeks continued rapidly withdrawing cash from ATMs due to fear that capital controls would soon be invoked to stop their liquidity loss, the Greek central bank convened a meeting on Sunday evening, June 28, in order to decide how to handle the liquidity crisis during the upcoming week. [citation needed]

On July 5th, 2015, the citizens of Greece voted decisively (a 61% to 39% decision with 62.5% voter turnout) to reject the referendum. This caused indexes worldwide to tumble, as many are now uncertain about Greece's future, fearing a potential exit from the European Union. Following the vote, Greece's finance minister Yanis Varoufakis stepped down on July 6th. Negotiations between Greece and other Eurozone members will continue in the following days to try to procure funds from the European Central Bank in order to prevent an economic collapse in the country.[39][40]

Financial position summary

Key statistics are summarized below, with a detailed table at the bottom of the article. According to the CIA World Factbook and Eurostat:

- Greek GDP fell from €242 billion in 2008 to €179 billion in 2014, a 26% decline overall. Greece was in recession for over five years, emerging in 2014 by some measures.

- GDP per capita fell from a peak of €22,500 in 2007 to €17,000 in 2014, a 24% decline.

- The public debt to GDP ratio in 2014 was 177% GDP or €317 billion. This ratio was the third highest in the world after Japan and Zimbabwe. The public debt peaked at €356 billion in 2011; it was reduced by a bailout program to €305 billion in 2012 and has risen slightly since then.

- The annual budget deficit (expenses over revenues) was 3.4% GDP in 2014, much improved versus the 15% GDP of 2009. Greece has achieved a primary budget surplus, meaning it had more revenue than expenses excluding interest payments in 2013 and 2014.

- Revenues for 2014 were €86 billion (about 48% GDP), while expenditures were €89.5 billion (about 50% GDP).

- Interest rates on Greek long-term debt rose from around 6% in 2014 to 10% in 2015. Based on a debt of €317 billion, the 6% rate represents annual interest payments of roughly €20 billion, nearly 23% of government revenues. For scale, U.S. interest is roughly 8% of revenues. Interest rates on German bonds were under 1% in 2015.

- The unemployment rate has risen considerably, from below 10% (2005–2009) to around 27% (2013–2014).

- An estimated 44% of Greeks lived below the poverty line in 2014.[41][42]

Greece defaulted on a $1.7 billion IMF payment on June 29, 2015, the first developed country to do so. Greece had requested a two-year bailout from its lenders for roughly $30 billion, its third in six years, but did not receive it.[43]

The IMF reported on July 2, 2015, that the "debt dynamics" of Greece were "unsustainable" due to its already high debt level and "...significant changes in policies since [2014]—not least, lower primary surpluses and a weak reform effort that will weigh on growth and privatization—[which] are leading to substantial new financing needs." The report also stated that debt reduction (haircuts, in which creditors sustain losses through principal reduction) would be required if the package of reforms under consideration were weakened further.[44]

Causes

Overview

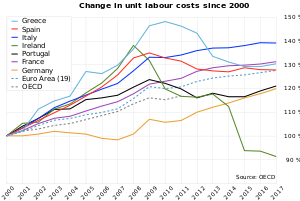

The present crisis in Greece has been attributed to the 1999 introduction of the euro as a common currency, which reduced trade costs among the Eurozone countries, increasing overall trade volume. However, labor costs increased more in peripheral countries such as Greece relative to core countries such as Germany, making Greek exports less competitive. As a result, Greece saw its trade deficit rise significantly.[45]

A trade deficit means that a country is consuming more than its income, which requires borrowing from other countries. Both the Greek trade deficit and budget deficit rose from below 5% of GDP (a measure of the size of the economy) in 1999 to peak around 15% of GDP in the 2008–2009 periods.[46] As the Great Recession that began in the U.S. in 2007–2009 spread to Europe, the flow of funds from the European core countries to the periphery began to dry up. Reports in 2009 of fiscal mismanagement and deception increased borrowing costs; the combination meant Greece could no longer borrow to finance its trade and budget deficits.[45]

A country facing a “sudden stop” in private investment and a high debt load typically allows its currency to depreciate (i.e., inflation) to encourage investment and to pay back the debt in cheaper currency, but this was not an option while Greece remains on the Euro.[45] Instead, to become more competitive, Greek wages fell nearly 20% from mid-2010 to 2014, a form of deflation. This resulted in a significant reduction in income or GDP, resulting in a severe recession and a significant rise in the debt to GDP ratio. Unemployment has risen to nearly 25%, from below 10% in 2003. However, significant government spending cuts have also helped the Greek government return to a primary budget surplus, meaning it now collects more revenue than it pays out, excluding interest.[47]

Government summary report

In January 2010, the Greek Ministry of Finance in their Stability and Growth Program 2010 listed these five main causes for eruption of the present government-debt crisis and the significantly deteriorated debt-to-GDP ratio in 2009 (compared to what had been forecast one year earlier), and outlined the first plan how to combat the crisis:[48]

- GDP growth rates: After 2008, GDP growth rates were lower than the Greek national statistical agency had anticipated. In the official report, the Greek ministry of finance reports the need for implementing economic reforms to improve competitiveness, among others by reducing salaries and bureaucracy,[48] and the need to redirect much of its current governmental spending from non-growth sectors (e.g. military) into growth stimulating sectors.

- Government deficit: Huge fiscal imbalances developed during the six years from 2004 to 2009, where "the output increased in nominal terms by 40%, while central government primary expenditures increased by 87% against an increase of only 31% in tax revenues." In the report the Greek Ministry of Finance states the aim to restore the fiscal balance of the public budget, by implementing permanent real expenditure cuts (meaning expenditures are only allowed to grow 3.8% from 2009 to 2013, which is below the expected inflation at 6.9%), and with overall revenues planned to grow 31.5% from 2009 to 2013, secured not only by new/higher taxes but also by a major reform of the ineffective Tax Collection System.

- Government debt-level: Mainly deteriorated in 2009 due to the higher than expected government deficit. Since the debt-to-GDP ratio had not been reduced during the good years with strong economic growth (2000–2007), there was no longer any headroom left for the government to continue running large deficits in 2010, neither for the years ahead, due to the annual debt-service costs being on the rise towards an unsustainable level. Implementation of an urgent fiscal consolidation plan was therefore needed, to ensure the deficit rapidly would decline to a level compatible with a declining debt-to-GDP ratio (not exceeding its sustainable limit). The Greek government assessed it was not enough just to implement their presented list of needed structural economic reforms, as the debt then still would develop rapidly into an unsustainable size in the short-term, before the positive results of such reforms – which typically first materialize after being implemented and working for a couple of years – could be achieved. On this basis the government's report emphasized, that in addition to implementing the needed structural economic reforms, it was urgent each year in the coming four-year period also to implement packages of both permanent and temporary austerity measures (with a size relative to GDP of 4.0% in 2010, 3.1% in 2011, 2.8% in 2012 and 0.8% in 2013). Implementation of this entire package of structural reforms and austerity measures, in combination with an expected return of positive economic growth in 2011, would then result in the baseline deficit being forecast to decrease from €30.6 billion in 2009 to only €5.7 billion in 2013, while the debt-level relative to GDP would stabilize at 120% in 2010–2011 and begin declining again in 2012 and 2013.

- Budget compliance: Budget compliance was acknowledged to be in strong need of future improvement, and for 2009 it was even found to be "A lot worse than normal, due to economic control being more lax in a year with political elections". In order to improve the level of budget compliance for upcoming years, the Greek government wanted to implement a new reform to strengthen the monitoring system in 2010, making it possible to keep better track on the future developments of revenues and expenses, both at the governmental and local level.

- Statistical credibility: Problems with unreliable data had existed ever since Greece applied for membership of the Euro in 1999.[49] In the five years from 2005 to 2009, Eurostat each year noted a reservation about the fiscal statistical numbers for Greece, and too often previously reported figures got revised to a somewhat worse figure, after a couple of years.[50][51][52] In regards of 2009 the flawed statistics made it impossible to predict accurate numbers for GDP growth, budget deficit and the public debt; which by the end of the year all turned out to be worse than originally anticipated. Problems with statistical credibility were also evident in several other countries, however, in the case of Greece, the magnitude of the 2009 revisions and its connection to the crisis added pressure to the need for immediate improvement.

In 2010, the Greek ministry of finance reported the need to restore trust among financial investors, and to correct previous statistical methodological issues, "by making the National Statistics Service an independent legal entity and phasing in, during the first quarter of 2010, all the necessary checks and balances that will improve the accuracy and reporting of fiscal statistics".[48]

Government spending

The Greek economy was one of the fastest growing in the Eurozone from 2000 to 2007: during this period it grew at an annual rate of 4.2%, as foreign capital flooded the country.[53] Despite that, the country continued to record high budget deficits each year.

Financial statistics reveal solid budget surpluses existed in 1960–73 for the Greek general government, but since then only budget deficits were recorded.[54][55][56] In 1974–80 the general government had an era with moderate and acceptable budget deficits (below 3% of GDP). This was followed by a long period with very high and unsustainable budget deficits in 1981–2013 (above 3% of GDP).[55][56][57][58]

According to an editorial published by the Greek conservative newspaper Kathimerini, large public deficits were indeed one of the features that marked the Greek social model since the restoration of democracy in 1974. After the removal of the right-wing military junta, the government wanted to bring disenfranchised left-leaning portions of the population into the economic mainstream.[59] In order to do so, successive Greek governments have, among other things, customarily run large deficits to finance enormous military expenditure, public sector jobs, pensions and other social benefits. Greece is, as a percentage of GDP, the second-biggest defense spender[60] among the 27 NATO countries after the United States, according to NATO statistics.

The US is the major supplier of Greek arms, with the Americans supplying 42 per cent of its arms, Germany supplying 22.7 per cent, and France 12.5 per cent of Greece's arms purchases.[61]

The long period with high yearly budget deficits caused a situation where, from 1993, the debt-to-GDP ratio was always found to be above 94%.[62] In the turmoil of the global financial crisis the situation became unsustainable (causing the capital markets to freeze in April 2010), as the downturn had caused the debt level rapidly to grow above the maximum sustainable level for Greece (defined by IMF economists to be 120%). According to "The Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece" published by the EU Commission in October 2011, the debt level was even expected further to worsen into a highly unsustainable level of 198% in 2012, if the proposed debt restructure agreement was not implemented.[63]

Prior to the introduction of the euro, currency devaluation had helped to finance Greek government borrowing; after the euro's introduction in January 2001, however, the devaluation tool disappeared. Throughout the next 8 years, Greece was however able to continue its high level of borrowing, due to the lower interest rates government bonds in euro could command, in combination with a long series of strong GDP growth rates. Problems however started to occur when the global financial crisis peaked, with negative repercussions hitting all national economies in September 2008. The global financial crisis had a particularly large negative impact on GDP growth rates in Greece. Two of the country's largest earners are tourism and shipping, and both were badly affected by the downturn, with revenues falling 15% in 2009.[64]

Current account balance

Economist Paul Krugman wrote in February 2012: "What we’re basically looking at...is a balance of payments problem, in which capital flooded south after the creation of the euro, leading to overvaluation in southern Europe."[65] He continued in June 2015: "In truth, this has never been a fiscal crisis at its root; it has always been a balance of payments crisis that manifests itself in part in budget problems, which have then been pushed onto the center of the stage by ideology."[66]

The translation of trade deficits to budget deficits works through sectoral balances. Greece ran current account (trade) deficits averaging 9.1% GDP from 2000–2011.[46] By definition, a trade deficit requires capital inflow (borrowing) to fund; this is referred to as a capital surplus or foreign financial surplus. This can drive higher levels of government budget deficits, if the private sector maintains relatively even amounts of savings and investment, as the three financial sectors (foreign, government, and private) by definition must balance to zero.

While Greece was running a large foreign financial surplus, it funded this by running a large budget deficit. As the inflow of money stopped during the crisis, reducing the foreign financial surplus, Greece was forced to reduce its budget deficit substantially. Countries facing such a sudden reversal in capital flows typically devalue their currencies to resume the inflow of capital; however, Greece cannot do this, and has suffered significant income (GDP) reduction, another form of devaluation.[45][46]

Tax evasion and corruption

Another persistent problem Greece has suffered in recent decades is the government's tax income. Each year it has been below the expected level. In 2010, the estimated tax evasion costs for the Greek government amounted to well over $20 billion.[67] The latest figures from 2013, also show that the State only collected less than half of the revenues due 2012, with the remaining tax owings being accepted to be paid by a delayed payment schedule.[68]

As of 2012, tax evasion was widespread, and according to Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index, Greece, with a score of 36/100, ranked as the most corrupt country in the EU.[69][70] One of the conditions of the bailout was implementation of an anti-corruption strategy;[71] Greek government agreed to combat corruption, and the corruption perception level improved to a score of 43/100 in 2014, which was still the lowest in the EU, but now on par with Italy, Bulgaria and Romania.[69][72]

It is estimated that the amount of tax evasion by Greeks stored in Swiss banks is around 80 billion EUR and a tax treaty to address this issue is negotiation between the Greek and Swiss government.[73][74]

Data for 2012[75] place the Greek "black economy" at 24.3% of GDP, compared with 28.6% for Estonia, 26.5% for Latvia, 21.6% for Italy, 17.1% for Belgium and 13.5% for Germany (partly in correlation with the percentage of Greek population that is self-employed[76] i.e., 31.9% in Greece vs. 15% EU average,[77] as several studies [78][79] have shown the clear correlation between tax evasion and self-employment).

In early 2010, economy commissioner Olli Rehn denied that other countries would need a bailout. He said, "Greece has had particularly precarious debt dynamics and Greece is the only member state that cheated with its statistics for years and years."[80] It was revealed that Goldman Sachs and other banks had helped the Greek government to hide its debts. Other sources said that similar agreements were concluded in "Greece, Italy, and possibly elsewhere".[81][82]

The deal with Greece was "extremely profitable" for Goldman. Christoforos Sardelis, former head of Greece’s Public Debt Management Agency, said that the country did not understand what it was buying. He also said he learned that "other EU countries such as Italy" had made similar deals.[83] This led to questions about what other countries had made similar deals.[84][85][86]

According to Der Spiegel credits given to European governments were disguised as "swaps" and consequently did not get registered as debt because Eurostat at the time ignored statistics involving financial derivatives. A German derivatives dealer commented to Der Spiegel that "The Maastricht rules can be circumvented quite legally through swaps," and "In previous years, Italy used a similar trick to mask its true debt with the help of a different US bank."[86] These conditions had enabled Greek as well as many other European governments to spend beyond their means, while meeting the deficit targets of the European Union.[81][87] In May 2010, the Greek government deficit was again revised and estimated to be 13.6%[88] which was the second highest in the world relative to GDP with Iceland in first place at 15.7% and Great Britain third with 12.6%.[89] Public debt was forecast, according to some estimates, to hit 120% of GDP during 2010.[90] The actual government debt to GDP ratio was closer to 150%.[91]

To keep within the monetary union guidelines, the government of Greece had also for many years misreported the country's official economic statistics.[92][93] At the beginning of 2010, it was discovered that Greece had paid Goldman Sachs and other banks hundreds of millions of dollars in fees since 2001, for arranging transactions that hid the actual level of borrowing.[94] Most notable is a cross currency swap, where billions worth of Greek debts and loans were converted into yen and dollars at a fictitious exchange rate by Goldman Sachs, thus hiding the true extent of Greek loans.[95]

The purpose of these deals made by several successive Greek governments, was to enable them to continue spending, while hiding the actual deficit from the EU, which, at the time, was a common practice amongst many European governments.[94] The revised statistics revealed that Greece at all years from 2000 to 2010 had exceeded the Eurozone stability criteria, with the yearly deficits exceeding the recommended maximum limit at 3.0% of GDP, and with the debt level significantly above the recommended limit of 60% of GDP.

Debt levels revealed (2010)

The European statistics agency, Eurostat, had at regular intervals ever since 2004, sent 10 delegations to Athens with a view to improving the reliability of statistical figures related to the Greek national account, but apparently to no avail. In January 2010, it issued a damning report which contained accusations of falsified data and political interference.[96]

In February 2010, the new government of George Papandreou (elected in October 2009) admitted a flawed statistical procedure previously had existed, before the new government had been elected, and revised the 2009 deficit from a previously estimated 6%–8% to an alarming 12.7% of GDP.[97] In April 2010, the reported 2009 deficit was further increased to 13.6%,[98] and the final revised calculation, using Eurostat's standardized method, set it at 15.7% of GDP; the highest deficit for any EU country in 2009.

The figure for Greek government debt at the end of 2009 was also increased from its first November estimate at €269.3 billion (113% of GDP)[99][100] to a revised €299.7 billion (130% of GDP). The need for a major and sudden upward revision of both the deficit and debt level for 2009, only being realized at a very late point, arose due to Greek authorities previously having published flawed estimates and statistics in 2009. To sort out all Greek statistical issues once and for all, Eurostat then decided to perform their own in depth Financial Audit of the fiscal years 2006–09. After having conducted the financial audit, Eurostat noted in November 2010 that all "methodological issues" now had been fixed, and that the new revised figures for 2006–2009 finally were considered to be reliable.[101][102][103]

Despite the crisis, the Greek government's bond auction in January 2010 had the offered amount of €8 bn 5-year bonds over-subscribed by four times.[104] At the next auction in March, the Financial Times again reported: "Athens sold €5bn in 10-year bonds and received orders for three times that amount".[105] The continued successful auction and sale of bonds was, however, only possible at the cost of increased yields, which in return caused a further worsening of the Greek public deficit. As a result, the rating agencies downgraded the Greek economy to junk status in late April 2010. This led to a freeze of the private capital market, requiring the Greek financial needs to be covered by international bailout loans to avoid a sovereign default.[106] In April 2010, it was estimated that up to 70% of Greek government bonds were held by foreign investors, primarily banks.[100] The subsequent bailout loans paid to Greece were mainly used to pay for the maturing bonds, but also to finance the continued yearly budget deficits.

Timeline

In the early–mid-2000s, Greece's economy was strong but at the same time government ran large spending deficits. As the world economy cooled in the late 2000s, Greece was hit especially hard because its main industries—shipping and tourism—were especially sensitive to changes in the business cycle. As a result, the country's debt began to pile up rapidly. In early 2010, as concerns about Greece's national debt grew, policy makers suggested that emergency bailouts might be necessary.

Downgrading of creditworthiness (December 2009 – April 2010)

On 23 April 2010, the Greek government requested an EU/IMF bailout package to be activated, providing them with a loan of €45 billion to cover their financial needs for the remaining part of 2010.[107][108] Standard & Poor's slashed Greece's sovereign debt rating on 27 April to BB+ amidst hints of default by the Greek government,[109][110] in which case investors were thought to lose 30–50% of their money.[109]

On 3 May 2010, the European Central Bank (ECB) suspended its minimum threshold for Greek debt,[111] which meant that the bonds became eligible as collateral even with junk status. The decision was supposed to guarantee Greek banks' access to cheap central bank funding.[112]

Shutdown of banks and stock market (June 2015 – present)

On Saturday 27 June 2015, the Greek government announced a shutdown of all banks in the country for at least ten days (six banking days), stating they would re-open on 7 July.[113] It also said automated teller machines, a large number of which had run out of cash, would "operate normally again by Monday noon at the latest" and that withdrawals would be limited to €60 a day for each account with exemptions for pension payments.

The Athens stock exchange (ATHEX) was also to be closed for a week, according to Kathimerini,[114] since the announced closure of Greek banks requires a suspension in Greece of the European TARGET2 international financial settlement system, which also processes ATHEX settlements. Western Union has also stopped operating in Greece, since Monday 29 June, and would not be open for at least a week.[115]

Solutions implemented

First Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece (May 2010 – June 2011)

This article appears to contradict the article First Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece. (December 2014) |

On 1 May 2010, the Greek government announced a series of austerity measures[116] to persuade Germany, the last remaining holdout, to sign on to a larger EU/IMF loan package.[117] The next day the eurozone countries and the International Monetary Fund agreed to a three-year €110 billion loan (see below) retaining relatively high interest rates of 5.5%,[118] conditional on the implementation of austerity measures. Credit rating agencies immediately downgraded Greek governmental bonds to an even lower junk status.

The new austerity package was met with great anger by the Greek public, leading to massive protests, riots and social unrest throughout Greece. On 5 May 2010, a national strike was held in opposition to the planned spending cuts and tax increases.[117] Nevertheless, the new extra fourth package with austerity measures was approved on 29 June 2011, with 155 out of 300 members of parliament voting in favour.

Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece (July 2011 – present)

EU emergency measures continued at a summit on 21 July 2011 in Brussels, where euro area leaders agreed to extend Greek (as well as Irish and Portuguese) loan repayment periods from 7 years to a minimum of 15 years and to cut interest rates to 3.5%. They also approved the construction of a new €109 billion support package, of which the exact content was to be debated and agreed on at a later summit.[119] On 27 October 2011, eurozone leaders and the IMF also came to an agreement with banks to accept a 50% write-off of (some part of) Greek debt.[120][121][122]

The austerity measures helped Greece bring down its primary deficit from €25bn (11% of GDP) in 2009 to €5bn (2.4% of GDP) in 2011,[123] but as a side-effect they also contributed to a worsening of the Greek recession. Overall the Greek GDP had its worst year in 2011 with a −7.1% decline.[124] The unemployment rate also grew from 7.5% in September 2008 to a, at the time, record high of 19.9% in November 2011.[125][126]

Impact of the conducted bank recapitalization

The Hellenic Financial Stability Fund (HFSF) managed to complete a €48.2bn bank recapitalization in June 2013, of which the first €24.4bn were injected into the four biggest Greek banks. Initially, this €48.2bn bank recapitalization was accounted for as an equally sized debt-increase, which – when assessed as an isolated factor – had elevated the debt-to-GDP ratio by 24.8 points by the end of 2012. However, in return for this, the Greek government at the same time received a number of shares in those banks being recapitalized, which it can now sell again during the upcoming years (a sale that per March 2012 was expected to generate €16bn of extra "privatization income" for the Greek government, to be realized during 2013–2020). For three out of the four big Greek banks (NBG, Alpha and Piraeus), where there was an additional private investor capital contribution at minimum 10% of the conducted recapitalization, HFSF has offered them warrants to buy back all HFSF bank shares in semi-annual exercise periods up to December 2017, at some predefined strike prices.[127] During the first warrant period, the shareholders in Alpha bank bought back the first 2.4% of the issued HFSF shares;[128] while the shareholders in Piraeus Bank only bought back the first 0.07% of the issued HFSF shares,[129] and finally the shareholders in National Bank (NBG) only bought back the first 0.01% of the issued HFSF shares, because the market share price was actually cheaper than the strike price.[130] This means, that HFSF can not be certain to sell all their bank shares, through the warrants program. In case some of the shares have not been sold by the end of December 2017, then HFSF is subsequently allowed to sell them to alternative investors.[127] In May 2014, a second round of bank recapitalization for all six commercial banks in Greece (Alpha, Eurobank, NBG, Piraeus, Attica and Panellinia),[71] worth €8.3bn, was concluded entirely finanzed by private shareholders, without HFSF needing to tap into any of their current €11.5bn reserve capital fund for future bank recapitalizations.[131] The fourth systemic bank (Eurobank), which failed to attract private investor participation in the first recapitalization program, and thus became almost entirely financed and owned by HFSF, also succeeded in the second round to introduce private investors;[132] although this was only achieved by HFSF accepting in the process to dilute their amount of shares from 95.2% to 34.7%.[133]

According to the third quarter 2014 financial report of HFSF, the fund is estimated to recover a total of €27.3bn out of the initially injected €48.2bn to the fund. This estimated recovery of €27.3bn comprise: "A €0.6bn positive cash balance stemming from its previous selling of warrants (selling of recapitalization shares) and liquidation of assets, €2.8bn estimated to be recovered from liquidation of assets held by its "bad asset bank", €10.9bn of EFSF bonds still held as capital reserve, and €13bn from its future sale of recapitalization shares in the four systemic banks." The last of these figures is affected by the highest amount of uncertainty, as it directly reflect the current market price of the held remaining shares in the four systemic banks (66.4% in Alpha, 35.4% in Eurobank, 57.2% in NBG, 66.9% in Piraeus), which for HFSF had a combined market value of €22.6bn by the end of 2013 – but only was worth €13bn on 10 December 2014.[134] Once HFSF has completed its task to sell and liquidate all its assets, the total amount of recovered capital will be returned to the Greek government, and by that year consequently help to reduce its total amount of gross debt with a similar figure. In early December 2014, the Bank of Greece allowed HFSF to repay the first €9.3bn out of its €11.3bn reserve to the Greek government (being transferred through the Greek government so that it results in direct repayment to ECB), as it was assessed there only remained a risk for some minor additional bank recapitalizations/liquidations to be financed by HFSF in the future.[135] A few months later, the remaining part of HFSF reserves were likewise approved for repayment to ECB, resulting in a total of €11.4bn debt notes being repaid during the course of the first quarter of 2015.[136]

Solutions under consideration

Possible default or restructuring

Without a bailout agreement, there was a possibility that Greece would prefer to default on some of its debt. The premiums on Greek debt rose to a level that reflected a high chance of a default or restructuring. Analysts gave a wide range of default probabilities, estimating a 25% to 90% chance of a default or restructuring.[137][138]

A default would most likely have taken the form of a restructuring where Greece would pay creditors, which include the up to €110 billion 2010 Greece bailout participants i.e. Eurozone governments and IMF, only a portion of what they were owed.[139] It has been claimed that this could destabilise the Euro Interbank Offered Rate, which is backed by government securities.[140]

Possible withdrawal from the eurozone

Some economists have argued that an orderly default is unavoidable for Greece in the long run, and that a delay in organising an orderly default (by lending Greece more money throughout a few more years), would just end up hurting Greece as well as EU lenders and neighboring European countries even more.[141] Fiscal austerity or a euro exit is the alternative to accepting differentiated government bond yields within the Euro Area. If Greece remains in the euro while accepting higher bond yields, reflecting its high government deficit, then high interest rates would dampen demand, raise savings and slow the economy. An improved trade performance and less reliance on foreign capital would be the result.[citation needed]

Others argue that a Greek exit from the eurozone would result in major capital flight and significant inflation that would destroy savings and make imports very expensive for Greeks. A Greek departure from the eurozone might, moreover, precipitate a larger contraction of the eurozone, as a result of the more marginal southern economies leaving. The departure of major eurozone economies such as Spain and Italy would be a major blow to the stability of the euro and might even lead to its eventual collapse.[142]

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former French President Nicolas Sarkozy said on numerous occasions that they would not allow the eurozone to disintegrate and have linked the survival of the Euro with that of the entire European Union.[143][144] In September 2011, EU commissioner Joaquín Almunia shared this view, saying that expelling weaker countries from the euro was not an option: "Those who think that this hypothesis is possible just do not understand our process of integration".[145]

Commentary

Criticism of Germany's role

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (July 2012) |

Critics have accused the German government of hypocrisy; of pursuing its own national interests via an unwillingness to adjust fiscal policy in a way that would help resolve the eurozone crisis, citing the benefits it enjoyed through the crisis including falling borrowing rates, investment influx, and exports boost thanks to the euro's depreciation;[146] of using the ECB to serve their country's national interests; and have criticised the nature of the austerity and debt-relief programme Greece has followed as part of the conditions attached to its bailouts.[147][148]

Accusations of hypocrisy

Hypocrisy has been alleged on multiple bases.

A Bloomberg editorial, which also concluded that "Europe's taxpayers have provided as much financial support to Germany as they have to Greece", described the German role and posture in the Greek crisis thus:

In the millions of words written about Europe's debt crisis, Germany is typically cast as the responsible adult and Greece as the profligate child. Prudent Germany, the narrative goes, is loath to bail out freeloading Greece, which borrowed more than it could afford and now must suffer the consequences. [… But] irresponsible borrowers can't exist without irresponsible lenders. Germany's banks were Greece's enablers.[149]

"Germany is coming across like a know-it-all in the debate over aid for Greece", commented Der Spiegel,[150] while its own government did not achieve a budget surplus during the era of 1970 to 2011.[151] Despite calling for the Greeks to adhere to fiscal responsibility, and although Germany's tax revenues are at a record high, with the interest it has to pay on new debt at close to zero, Germany still missed its own cost-cutting targets in 2011, and also fell behind on its goals for 2012.[152]

German economic historian Albrecht Ritschl describes his country as "king when it comes to debt. Calculated based on the amount of losses compared to economic performance, Germany was the biggest debt transgressor of the 20th century."[150] Leading economist Thomas Piketty has spoken similarly of this:

What struck me while I was writing [Capital in the Twenty-First Century] is that Germany is really the single best example of a country that, throughout its history, has never repaid its external debt. […] When I hear the Germans say that they maintain a very moral stance about debt and strongly believe that debts must be repaid, then I think: what a huge joke! Germany is the country that has never repaid its debts. It has no standing to lecture other nations.[153]

There have been widespread accusations that Greeks are lazy, but analysis of OECD data shows that the average Greek worker puts in 50% more hours per year than a typical German counterpart,[154] and the average retirement age of a Greek is, at 61.7 years, older than that of a German.[155]

US economist Mark Weisbrot has also noted that while the eurozone giant's post-crisis recovery has been touted as an example of an economy of a country that "made the short-term sacrifices necessary for long-term success", Germany did not apply to its economy the harsh pro-cyclical austerity measures that are being imposed on countries like Greece,[156][157] In addition, he noted that Germany did not lay off hundreds of thousands of its workers despite a decline in output in its economy but reduced the number of working hours to keep them employed, at the same time as Greece and other countries were pressured to adopt measures to make it easier for employers to lay off workers.[156] Weisbrot concludes that the German recovery provides no evidence that the problems created by the use of a single currency in the eurozone can be solved by imposing "self-destructive" pro-cyclical policies as has been done in Greece and elsewhere.[156]

Arms sales are another fountainhead for allegations of hypocrisy. Dimitris Papadimoulis, a Greek MP with the Coalition of the Radical Left party:

If there is one country that has benefited from the huge amounts Greece spends on defence it is Germany. Just under 15% of Germany's total arms exports are made to Greece, its biggest market in Europe. Greece has paid over €2bn for submarines that proved to be faulty and which it doesn't even need. It owes another €1bn as part of the deal. That's three times the amount Athens was asked to make in additional pension cuts to secure its latest EU aid package. […] Well after the economic crisis had begun, Germany and France were trying to seal lucrative weapons deals even as they were pushing us to make deep cuts in areas like health. […] There's a level of hypocrisy here that is hard to miss. Corruption in Greece is frequently singled out as a cause for waste but at the same time companies like Ferrostaal and Siemens are pioneers in the practice. A big part of our defence spending is bound up with bribes, black money that funds the [mainstream] political class in a nation where governments have got away with it by long playing on peoples' fears.[158]

Thus allegations of hypocrisy could be made towards both sides: Germany complains of Greek corruption, yet the arms sales meant that the trade with Greece became synonymous with high-level bribery and corruption; former defence minister Akis Tsochadzopoulos was gaoled in April 2012 ahead of his trial on charges of accepting an €8m bribe from Germany company Ferrostaal.[158] In 2000, the current German finance minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, was forced to resign after personally accepting a "donation" (100,000 Deutsche Mark, in cash) from a fugitive weapons dealer, Karlheinz Schreiber.[159]

Another is German complaints about tax evasion by moneyed Greeks.[160] "Germans stashing cash in Switzerland to avoid tax could sleep easy" after summer 2011, when "the German government […] initialled a beggar-thy-neighbour deal that undermine[d] years of diplomatic work to penetrate Switzerland's globally corrosive banking secrecy."[161] Nevertheless, Germans with Swiss bank accounts were so worried, so intent on avoiding paying tax, that some took to cross-dressing, wearing incontinence diapers, and other ruses to try and smuggle their money over the Swiss–German border and so avoid paying their dues to the German taxman.[162] Aside from these unusual tax-evasion techniques, Germany has a history of massive tax evasion: a 1993 ZEW estimate of levels of income-tax avoidance in West Germany in the early 1980s was forced to conclude that "tax loss [in the FDR] exceeds estimates for other countries by orders of magnitude." (The study even excluded the wealthiest 2% of the population, where tax evasion is at its worst).[163] A 2011 study noted that, since the 1990s, the "effective average tax rates for the German super rich have fallen by about a third, with major reductions occurring in the wake of the personal income tax reform of 2001–2005."[164]

Alleged pursuit of national self-interest

Listen to many European leaders—especially, but by no means only, the Germans—and you'd think that their continent's troubles are a simple morality tale of debt and punishment: Governments borrowed too much, now they're paying the price, and fiscal austerity is the only answer.[165]

"An Impeccable Disaster"

Paul Krugman, 5 November 2013

Since the euro came into circulation in 2002—a time when the country was suffering slow growth and high unemployment—Germany's export performance, coupled with sustained pressure for moderate wage increases (German wages increased more slowly than those of any other eurozone nation) and rapidly rising wage increases elsewhere, provided its exporters with a competitive advantage that resulted in German domination of trade and capital flows within the currency bloc.[166] As noted by Paul De Grauwe in his leading text on monetary union, however, one must "hav[e] homogenous preferences about inflation in order to have a smoothly functioning monetary union."[167] Thus Germany broke what the Levy Economics Institute has called "the golden rule of a monetary union" when it jettisoned a common inflation rate.[168]

The violation of this golden rule led to dire imbalances within the eurozone, though they suited Germany well: the country's total export trade value nearly tripled between 2000 and 2007, and though a significant proportion of this is accounted for by trade with China, Germany's trade surplus with the rest of the EU grew from €46.4 bn to €126.5 bn during those seven years. Germany's bilateral trade surpluses with the peripheral countries are especially revealing: between 2000 and 2007, Greece's annual trade deficit with Germany nearly doubled, from €3 bn to €5.5 bn; Italy's more than doubled, from €9.6 bn to €19.6 bn; Spain's well over doubled, from €11 bn to €27.2 bn; and Portugal's more than quadrupled, from €1 bn to €4.2 bn.[169] German banks played an important role in supplying the credit that drove wage increases in peripheral eurozone countries like Greece, which in turn produced this divergence in competitiveness and trade surpluses between Germany and these same eurozone members.[170]

Germans see their government finances and trade competitiveness as an example to be followed by Greece, Portugal and other troubled countries in Europe,[171] but the problem is more than simply a question of southern European countries emulating Germany.[172] Dealing with debt via domestic austerity and a move toward trade surpluses is very difficult without the option of devaluing your currency, and Greece cannot devalue because it is chained to the euro.[173][174] As can be seen from the case of China and the US, however, where China has had the yuan pegged to the dollar, it is possible to have an effective devaluation in situations where formal devaluation cannot occur, and that is by having the inflation rates of two countries diverge.[175] If inflation in Germany is higher than in Greece and other struggling countries, then the real effective exchange rate will move in the strugglers' favour despite the shared currency. Trade between the two can then rebalance, aiding recovery, as Greek products become cheaper.[174] Paul Krugman estimated that Spain and other peripherals would need to reduce their 2012 price-levels relative to Germany by around 20 percent to become competitive again:

If Germany had 4 percent inflation, they could do that over 5 years with stable prices in the periphery—which would imply an overall eurozone inflation rate of something like 3 percent. But if Germany is going to have only 1 percent inflation, we're talking about massive deflation in the periphery, which is both hard (probably impossible) as a macroeconomic proposition, and would greatly magnify the debt burden. This is a recipe for failure, and collapse.[176]

This view, that German deficits are a crucial factor in assisting eurozone recovery, is shared by leading economics commentators,[176][177][178] by the OECD,[179] the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace,[180] Deutsche Bank,[181] Credit Suisse,[182] Standard & Poor's,[183] the European Commission,[184] and the IMF.[185] The Americans, too, asked Germany, repeatedly and heatedly, to loosen fiscal policy, though without success.[186][187] This failure led to the US taking a more high-powered tack: for the first time, the Treasury Department, in its semi-annual currency report for October 2013, singled out Germany as the leading obstacle to economic recovery in Europe.[188]

Therefore, it is argued, the problem is Germany continuing[189] to shut off this adjustment mechanism.[172] "The counterpart to Germany living within its means is that others are living beyond their means", agreed Philip Whyte, senior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform. "So if Germany is worried about the fact that other countries are sinking further into debt, it should be worried about the size of its trade surpluses, but it isn't."[190]

This chorus of criticism, however, germinates in the very poorest of soil because, in October 2012, Germany chose to legislate against the very possibility of stimulus spending, "by passing a balanced budget law that requires the government to run near-zero structural deficits indefinitely."[191] OECD projections of relative export prices—a measure of competitiveness—showed Germany beating all euro zone members except for crisis-hit Spain and Ireland for 2012, with the lead only widening in subsequent years.[192]

Even with such policies, Greece and other countries would have faced years of hard times, but at least there would be some hope of recovery.[193] During 2012, it seemed as though the status quo was beginning to change as France began to challenge German policy,[194] and even Christine Lagarde called for Greece to at least be given more time to meet bailout targets.[195] Further criticism mounted in 2013: a leaked version of a text from French president Francois Hollande's Socialist Party openly attacked "German austerity" and the "egoistic intransigence of Mrs Merkel";[196] Manuel Barroso warned that austerity had "reached its limits";[197] EU employment chief Laszlo Andor called for a radical change in EU crisis strategy—"If there is no growth, I don't see how countries can cut their debt levels"—and criticised what he described as the German practice of "wage dumping" within the eurozone to gain larger export surpluses;[196] and Heiner Flassbeck (a former German vice finance minister) and economist Costas Lapavitsas charged that the euro had "allowed Germany to 'beggar its neighbours', while also providing the mechanisms and the ideology for imposing austerity on the continent".[198]

Battered by criticism,[199] the European Commission finally decided that "something more" was needed in addition to austerity policies for peripheral countries like Greece. "Something more" was announced to be structural reforms—things like making it easier for companies to sack workers—but such reforms have been there from the very beginning, leading Dani Rodrik to dismiss the EC's idea as "merely old wine in a new bottle." Indeed, Rodrik noted that with demand gutted by austerity, all structural reforms have achieved, and would continue to achieve, is pumping up unemployment (further reducing demand), since fired workers are not going to be re-employed elsewhere. Rodrik suggested the ECB might like to try out a higher inflation target, and that Germany might like to allow increased demand, higher inflation, and to accept its banks taking losses on their reckless lending to Greece. That, however, "assumes that Germans can embrace a different narrative about the nature of the crisis. And that means that German leaders must portray the crisis not as a morality play pitting lazy, profligate southerners against hard-working, frugal northerners, but as a crisis of interdependence in an economic (and nascent political) union. Germans must play as big a role in resolving the crisis as they did in instigating it."[200] Paul Krugman described talk of structural reform as "an excuse for not facing up to the reality of macroeconomic disaster, and a way to avoid discussing the responsibility of Germany and the ECB, in particular, to help end this disaster."[201] Furthermore, as Financial Times analyst Wolfgang Munchau observed, "Austerity and reform are the opposite of each other. If you are serious about structural reform, it will cost you upfront money."[202] Claims that Germany had, by mid-2012, given Greece the equivalent of 29 times the aid given to West Germany under the Marshall Plan after World War II completely ignores the fact that aid was just a small part of Marshall Plan assistance to Germany, with another crucial part of the assistance being the writing off of a majority of Germany's debt.[203]

Artificially low exchange rate

Though Germany claims its public finances are "the envy of the world",[204] the country is merely continuing what has been called its "free-riding" of the euro crisis, which "consists in using the euro as a mechanism for maintaining a weak exchange rate while shifting the costs of doing so to its neighbors."[205] With eurozone adjustment locked out by Germany, economic hardship elsewhere in the currency block actually suited its export-oriented economy for an extended period, because it caused the euro to depreciate,[206] making German exports cheaper and so more competitive.[171][207] The weakness of the euro, caused by the economy misery of peripheral countries, has been providing Germany with a large and artificial export advantage to the extent that, if Germany left the euro, the concomitant surge in the value of the reintroduced Deutsche Mark, which would produce "disastrous"[208] effects on German exports as they suddenly became dramatically more expensive, would play the lead role in imposing a cost on Germany of perhaps 20–25% GDP during the first year alone after its euro exit.[209] November 2013 saw the European Commission open an in-depth inquiry into German's surplus,[210] which hit a new record in spring 2015.[211] As the German current accounts surplus looked set to smash all previous records again in Spring 2015, one commentator noted that Germany was "now the biggest single violator of the eurozone stability rules. It would face punitive sanctions if EU treaty law was enforced."[212] 2015 is "the fifth consecutive year that Germany's surplus has been above 6pc of GDP," it was pointed out. "The EU's Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure states that the Commission should launch infringement proceedings if this occurs for three years in a row, unless there is a clear reason not to."[212]

Advocacy of internal devaluation for peripheral economies

The version of adjustment offered by Germany and its allies is that austerity will lead to an internal devaluation, i.e. deflation, which would enable Greece gradually to regain competitiveness. "Yet this proposed solution is a complete non-starter", in the opinion of one UK economist. "If austerity succeeds in delivering deflation, then the growth of nominal GDP will be depressed; most likely it will turn negative. In that case, the burden of debt will increase."[213] A February 2013 research note by the Economics Research team at Goldman Sachs again noted that the years of recession being endured by Greece "exacerbate the fiscal difficulties as the denominator of the debt-to-GDP ratio diminishes",[214] i.e. reducing the debt burden by imposing austerity is, aside from anything else, utterly futile.[215][216] "Higher growth has always been the best way out the debt (absolute and relative) burden. However, growth prospects for the near and medium-term future are quite weak. During the Great Depression, Heinrich Brüning, the German Chancellor (1930–32), thought that a strong currency and a balanced budget were the ways out of crisis. Cruel austerity measures such as cuts in wages, pensions and social benefits followed. Over the years crises deepened".[217] The austerity program applied to Greece has been "self-defeating",[218] with the country's debt now expected to balloon to 192% of GDP by 2014.[219] After years of the situation being pointed out, in June 2013, with the Greek debt burden galloping towards the "staggering"[220] heights previously predicted by anyone who knew what they were talking about, and with her own organization admitting its program for Greece had failed seriously on multiple primary objectives[221] and that it had bent its rules when "rescuing" Greece;[222] and having claimed in the past that Greece's debt was sustainable[222]—Christine Lagarde felt able to admit publicly that perhaps Greece just might, after all, need to have its debt written off in a meaningful way.[220] In its Global Economic Outlook and Strategy of September 2013, Citi pointed out that Greece "lack[s] the ability to stabilise […] debt/GDP ratios in coming years by fiscal policy alone",[223]: 7 and that "large debt relief" is probably "the only viable option" if Greek fiscal sustainability is to re-materialise;[223]: 18 predicted no return to growth until 2016;[223]: 8 and predicted that the debt burden would soar to over 200% of GDP by 2015 and carry on rising through at least 2017.[223]: 9 Unfortunately, German Chancellor Merkel and Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle had just a few months prior already spoken out again against any debt relief for Greece, claiming that "structural reforms" (i.e. "old wine in a new bottle", see Rodrik et al. above) were the way to go and—astonishingly—that "debt sustainability will continue to be assured".[224][225]

Strictly in terms of reducing wages relative to Germany, Greece had been making 'progress': private-sector wages fell 5.4% in the third quarter of 2011 from a year earlier and 12% since their peak in the first quarter of 2010.[226] The second economic adjustment programme for Greece called for a further labour cost reduction in the private sector of 15% during 2012–2014.[227]

German views on inflation as a solution

The question then is whether Germany would accept the price of inflation to assist a eurozone recovery.[228] On the upside, inflation, at least to start with, would make Germans happy as their wages rose in keeping with inflation.[228] Regardless of these positives, as soon as the monetary policy of the ECB—which has been catering to German desires for low inflation[229][230] so doggedly that Martin Wolf describes it as "a reincarnated Bundesbank"[231]—began to look like it might stoke inflation in Germany, Merkel moved to counteract, cementing the impossibility of a recovery for struggling countries.[181]

All of this has resulted in increased anti-German sentiment within peripheral countries like Greece and Spain.[232][233][234] German historian Arnulf Baring, who opposed the euro, wrote in his 1997 book Scheitert Deutschland? (Does Germany fail?): "They (populistic media and politicians) will say that we finance lazy slackers, sitting in coffee shops on southern beaches", and "[t]he fiscal union will end in a giant blackmail manoeuvre […] When we Germans will demand fiscal discipline, other countries will blame this fiscal discipline and therefore us for their financial difficulties. Besides, although they initially agreed on the terms, they will consider us as some kind of economic police. Consequently, we risk again becoming the most hated people in Europe."[235] Anti-German animus is perhaps inflamed by the fact that, as one German historian noted, "during much of the 20th century, the situation was radically different: after the first world war and again after the second world war, Germany was the world's largest debtor, and in both cases owed its economic recovery to large-scale debt relief."[236] When Horst Reichenbach arrived in Athens towards the end of 2011 to head a new European Union task force, the Greek media instantly dubbed him "Third Reichenbach";[190] in Spain in May 2012, businessmen made unflattering comparisons with Berlin's domination of Europe in WWII, and top officials "mutter about how today's European Union consists of a 'German Union plus the rest'".[233] Almost four million German tourists—more than any other EU country—visit Greece annually, but they comprised most of the 50,000 cancelled bookings in the ten days after the 6 May 2012 Greek elections, a figure The Observer called "extraordinary". The Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises estimates that German visits for 2012 will decrease by about 25%.[237] Such is the ill-feeling, historic claims on Germany from WWII have been reopened,[238] including "a huge, never-repaid loan the nation was forced to make under Nazi occupation from 1941 to 1945."[239]

Analysis of the Greek rescue

One estimate is that Greece actually subscribed to €156bn worth of new debt in order to get €206bn worth of old debt to be written off, meaning the write-down of €110bn by the banks and others is more than double the true figure of €50bn that was truly written off. Taxpayers are now liable for more than 80% of Greece's debt.[240] One journalist for Der Spiegel noted that the second bailout was not "geared to the requirements of the people of Greece but to the needs of the international financial markets, meaning the banks. How else can one explain the fact that around a quarter of the package won't even arrive in Athens but will flow directly to the country's international creditors?" He accused the banks of "cleverly manipulating the fear that a Greek bankruptcy would trigger a fatal chain reaction" in order to get paid.[241] According to Robert Reich, in the background of the Greek bailouts and debt restructuring lurks Wall Street. While US banks are owed only about €5bn by Greece, they have more significant exposure to the situation via German and French banks, who were significantly exposed to Greek debt. Massively reducing the liabilities of German and French banks with regards to Greece thus also serves to protect US banks.[242]

According to Der Spiegel "more than 80 percent of the rescue package is going to creditors—that is to say, to banks outside of Greece and to the ECB. The billions of taxpayer euros are not saving Greece. They're saving the banks."[243] One study found that the public debt of Greece to foreign governments, including debt to the EU/IMF loan facility and debt through the eurosystem, increased by €130 bn, from €47.8 bn to €180.5 billion, between January 2010 and September 2011.[244] The combined exposure of foreign banks to Greek entities—public and private—was around 80bn euros by mid-February 2012. In 2009 they were in for well over 200bn.[245] The Economist noted that, during 2012 alone, "private-sector bondholders reduced their nominal claims by more than 50%. But the deal did not include the hefty holdings of Greek bonds at the European Central Bank (ECB), and it was sweetened with funds borrowed from official rescuers. For two years those rescuers had pretended Greece was solvent, and provided official loans to pay off bondholders in full. So more than 70% of the debts are now owed to 'official' creditors", i.e. European taxpayers and the IMF.[246] With regard to Germany in particular, a Bloomberg editorial noted that, before its banks reduced its exposure to Greece, "they stood to lose a ton of money if Greece left the euro. Now any losses will be shared with the taxpayers of the entire euro area."[149]

Creditors

Initially, European banks had the largest holdings of Greek debt. However, this has shifted as the "troika" (i.e., European Central Bank or ECB, International Monetary Fund or IMF, and a European government-sponsored fund) have purchased Greek bonds. As of early 2015, Germany and France were the largest individual contributors to the fund, with roughly €100B total of the €323B debt. The IMF is owed €32B and the ECB €20B. Foreign banks had little Greek debt.[247]

European banks

Excluding Greek banks, European banks had €45.8bn exposure to Greece in June 2011, with €9.4bn held by French and €7.9bn by German banks.[248] However, by early 2015 their holdings were minimal, roughly €2.4B.[247]

Greek public opinion

According to a poll in February 2012 by Public Issue and SKAI Channel, PASOK—which won the national elections of 2009 with 43.92% of the vote—had seen its approval rating reduced to a mere 8%, placing it fifth after centre-right New Democracy (31%), left-wing Democratic Left (18%), far-left Communist Party of Greece (KKE) (12.5%) and radical left SYRIZA (12%). The same poll suggested that Papandreou was the least popular political leader with a 9% approval rating, while 71% of Greeks did not trust Papademos as prime minister.[249]

In a poll published on 18 May 2011, 62% of the people questioned felt the IMF memorandum that Greece signed in 2010 was a bad decision that hurt the country, while 80% had no faith in the Minister of Finance, Giorgos Papakonstantinou, to handle the crisis.[250] (Evangelos Venizelos replaced Papakonstantinou on 17 June). 75% of those polled had a negative image of the IMF, and 65% felt it was hurting Greece's economy.[250] 64% felt that sovereign default was likely. When asked about their fears for the near future, Greeks highlighted unemployment (97%), poverty (93%) and the closure of businesses (92%).[250]

Polls have shown that the vast majority of Greeks are not in favour of leaving the Eurozone.[251] Roger Bootle, a London City economist, wrote of this: "there has been so much propaganda over the years about the merits of the euro and the perils of being outside it that both expert and popular opinion can barely see straight. It is true that default and a euro exit could endanger Greece's continued membership of the EU. More importantly, though, there is a strong element of national pride. For Greece to leave the euro would seem like a national humiliation. Mind you, quite how agreeing to decades of misery under German subjugation allows Greeks to hold their heads high defeats me."[213] Nonetheless, other 2012 polls showed that almost half (48%) of Greeks were in favour of default, in contrast with a minority (38%) who are not.[252]

Economic and social effects of the crisis

Economic effects

Greek GDP suffered its worst decline in 2011 when it clocked growth of −6.9%;[253] a year where the seasonal adjusted industrial output ended 28.4% lower than in 2005,[254][255] during that year, 111,000 Greek companies went bankrupt (27% higher than in 2010).[256][257] As a result, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate also grew from 7.5% in September 2008 to a then record high of 23.1% in May 2012, while the youth unemployment rate during the same time rose from 22.0% to 54.9%.[125][126][258] On 17 October 2011, Minister of Finance Evangelos Venizelos announced that the government would establish a new fund, aimed at helping those who were hit the hardest from the government's austerity measures.[259] The money for this agency would come from a crackdown on tax evasion.[259]

Social effects

The social effects of the austerity measures on the Greek population have been severe, as well as on poor and needy foreign immigrants, with some Greek citizens turning to NGOs for healthcare treatment[260] and having to give up children for adoption.[261] "[F]ood aid, in a western European capital?" remarked one aghast BBC journalist after visiting Athens, before observing: "You do not measure a people's ability to survive in percentages of Gross Domestic Product."[262] Another BBC reporter wrote: "As you walk around the streets of Athens and beyond you can see the social fabric tearing."[263]

In February 2012, it was reported that 20,000 Greeks had been made homeless during the preceding year, and that 20 per cent of shops in the historic city centre of Athens were empty.[264] The same month, Poul Thomsen, a Danish IMF official overseeing the Greek austerity programme, warned that ordinary Greeks were at the "limit" of their toleration of austerity, and he called for a higher international recognition of "the fact that Greece has already done a lot fiscal consolidation, at a great cost to the population";[265] and moreover cautioned that although further spending cuts were certainly still needed, they should not be implemented rapidly, as it was crucial first to give some more time for the implemented economic reforms to start to work.[266] Estimates in mid-March 2012 were that an astonishing one in 11 residents of greater Athens—some 400,000 people—were visiting a soup kitchen daily.[267]

Prominent UK economist Roger Bootle summarised the state of play at the end of February 2012:

Since the beginning of 2008, Greek real GDP has fallen by more than 17pc. On my forecasts, by the end of next year, the total fall will be more like 25pc. Unsurprisingly, employment has also fallen sharply, by about 500,000, in a total workforce of about 5 million. The unemployment rate is now more than 20pc. […] A 25pc drop is roughly what was experienced in the US in the Great Depression of the 1930s. The scale of the austerity measures already enacted makes you wince. In 2010 and 2011, Greece implemented fiscal cutbacks worth almost 17pc of GDP. But because this caused GDP to wilt, each euro of fiscal tightening reduced the deficit by only 50 cents. […] Attempts to cut back on the debt by austerity alone will deliver misery alone.[213]

Thus, youth unemployment in mid-2013 stood at almost 65%;[268] there were 800,000 people without unemployment benefits and health coverage, and 400,000 families without a single bread winner;[269] the far Right was consistently polling a double-digit share of the vote;[270] the Greek healthcare system on its knees,[271][272] and HIV infection rates were up 200%.[273][274]

International ramifications

- Outlook in May 2010

Greece represents only 2.5% of the eurozone economy.[275] Despite its size, the danger is that a default by Greece may cause investors to lose faith in other eurozone countries. This concern is focused on Portugal and Ireland, both of whom have high debt and deficit issues.[276] Italy also has a high debt, but its budget position is better than the European average, and it is not considered among the countries most at risk.[277] Recent rumours raised by speculators about a Spanish bail-out were dismissed by Spanish Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero as "complete insanity" and "intolerable".[278]

Spain has a comparatively low debt among advanced economies, at only 53% of GDP in 2010, more than 20 points less than Germany, France or the US, and more than 60 points less than Italy, Ireland or Greece,[279] and according to Standard & Poor's it does not risk a default.[280] Spain and Italy are far larger and more central economies than Greece; both countries have most of their debt controlled internally, and are in a better fiscal situation than Greece and Portugal, making a default unlikely unless the situation gets far more severe.[281]

- Outlook in October 2012

The contagion risk for other eurozone countries in the event of an uncontrolled Greek default has greatly diminished in the last couple of years. This is mainly due to a successful fiscal consolidation and implementation of structural reforms in the countries being most at risk, which significantly improved their financial stability. Establishment of an appropriate and permanent financial stability support mechanism for the eurozone (ESM),[282] along with guarantees by ECB to offer additional financial support in the form of some yield-lowering bond purchases (OMT) for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout program from EFSF/ESM (at the point of time where the country regain/possess a complete market access),[283][284] also greatly helped to diminish the contagion risk.

If Spain signs a negotiated Memorandum of Understanding with the Troika (EC, ECB and IMF) outlining ESM shall offer a precautionary programme with credit lines for the Spanish government to potentially draw on if needed (beside of the bank recapitalisation package they already applied for), this would qualify Spain also to receive the OMT support from ECB, as the sovereign state would still continue to operate with a complete market access with the precautionary conditioned credit line. In regards of Ireland, Portugal and Greece they on the other hand have not yet regained complete market access, and thus do not yet qualify for OMT support.[285] Provided these 3 countries continue to adhere to the programme conditions outlined in their signed Memorandum of Understanding, they will qualify to receive OMT at the moment they regain complete market access.[283]