Algeria

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية (Arabic) ⵟⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵎⴻⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴰⵏⵜ ⵜⴰⵣⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ (Berber languages) République démocratique populaire d'Algérie (French) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: بالشّعب وللشّعب By the people and for the people[1][2] | |

| Anthem: Kassaman (Template:Lang-en) | |

Location of Algeria (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Algiers 36°42′N 3°13′E / 36.700°N 3.217°E |

| Official languages | |

| Other languages | French (Business and education)[5] |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential people's republic |

| Abdelaziz Bouteflika | |

| Abdelmalek Sellal | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Council of the Nation | |

| People's National Assembly | |

| Independence from France | |

• Declared | 3 July 1962 |

• Recognised | 5 July 1962 |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,381,741 km2 (919,595 sq mi) (10th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2016 estimate | 40,400,000[6] (33rd) |

• 2013 census | 37,900,000[6] |

• Density | 15.9/km2 (41.2/sq mi) (208th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $609.394 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $14,949[7] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2016 estimate |

• Total | $168.318 billion[7] |

• Per capita | $4,129[7] |

| Gini (1995) | 35.3[8] medium inequality |

| HDI (2015) | high (83rd) |

| Currency | Dinar (DZD) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | right[10] |

| Calling code | +213 |

| ISO 3166 code | DZ |

| Internet TLD | .dz الجزائر. |

| |

Algeria (Template:Lang-ar al-Jazā'ir; Template:Lang-ber, Dzayer; Template:Lang-fr), officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a sovereign state in North Africa on the Mediterranean coast. Its capital and most populous city is Algiers, located in the country's far north. With an area of 2,381,741 square kilometres (919,595 sq mi), Algeria is the tenth-largest country in the world, and the largest in Africa.[11] Algeria is bordered to the northeast by Tunisia, to the east by Libya, to the west by Morocco, to the southwest by the Western Saharan territory, Mauritania, and Mali, to the southeast by Niger, and to the north by the Mediterranean Sea. The country is a semi-presidential republic consisting of 48 provinces and 1,541 communes (counties). Abdelaziz Bouteflika has been President since 1999.

Ancient Algeria has known many empires and dynasties, including ancient Numidians, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Byzantines, Umayyads, Abbasids, Idrisid, Aghlabid, Rustamid, Fatimids, Zirid, Hammadids, Almoravids, Almohads, Ottomans and the French colonial empire. Berbers are the indigenous inhabitants of Algeria.

Algeria is a regional and middle power. The North African country supplies large amounts of natural gas to Europe, and energy exports are the backbone of the economy. According to OPEC Algeria has the 16th largest oil reserves in the world and the second largest in Africa, while it has the 9th largest reserves of natural gas. Sonatrach, the national oil company, is the largest company in Africa. Algeria has one of the largest militaries in Africa and the largest defence budget on the continent; most of Algeria's weapons are imported from Russia, with whom they are a close ally.[12][13] Algeria is a member of the African Union, the Arab League, OPEC, the United Nations and is the founding member of the Maghreb Union.

Etymology

The country's name derives from the city of Algiers. The city's name in turn derives from the Arabic al-Jazā'ir (الجزائر, "The Islands"),[14] a truncated form of the older Jazā'ir Banī Mazghanna (جزائر بني مزغنة, "Islands of the Mazghanna Tribe"),[15][page needed][16][page needed] employed by medieval geographers such as al-Idrisi.

History

Ancient history

In the region of Ain Hanech (Saïda Province), early remnants (200,000 BC) of hominid occupation in North Africa were found. Neanderthal tool makers produced hand axes in the Levalloisian and Mousterian styles (43,000 BC) similar to those in the Levant.[17][18]

Algeria was the site of the highest state of development of Middle Paleolithic Flake tool techniques. Tools of this era, starting about 30,000 BC, are called Aterian (after the archeological site of Bir el Ater, south of Tebessa).

The earliest blade industries in North Africa are called Iberomaurusian (located mainly in Oran region). This industry appears to have spread throughout the coastal regions of the Maghreb between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. Neolithic civilization (animal domestication and agriculture) developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghreb perhaps as early as 11,000 BC[19] or as late as between 6000 and 2000 BC. This life, richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer paintings, predominated in Algeria until the classical period.

The amalgam of peoples of North Africa coalesced eventually into a distinct native population that came to be called Berbers, who are the indigenous peoples of northern Africa.[20]

From their principal center of power at Carthage, the Carthaginians expanded and established small settlements along the North African coast; by 600 BC, a Phoenician presence existed at Tipasa, east of Cherchell, Hippo Regius (modern Annaba) and Rusicade (modern Skikda). These settlements served as market towns as well as anchorages.

As Carthaginian power grew, its impact on the indigenous population increased dramatically. Berber civilization was already at a stage in which agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and political organization supported several states. Trade links between Carthage and the Berbers in the interior grew, but territorial expansion also resulted in the enslavement or military recruitment of some Berbers and in the extraction of tribute from others.

By the early 4th century BC, Berbers formed the single largest element of the Carthaginian army. In the Revolt of the Mercenaries, Berber soldiers rebelled from 241 to 238 BC after being unpaid following the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. They succeeded in obtaining control of much of Carthage's North African territory, and they minted coins bearing the name Libyan, used in Greek to describe natives of North Africa. The Carthaginian state declined because of successive defeats by the Romans in the Punic Wars.

In 146 BC the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew. By the 2nd century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. Two of them were established in Numidia, behind the coastal areas controlled by Carthage. West of Numidia lay Mauretania, which extended across the Moulouya River in modern-day Morocco to the Atlantic Ocean. The high point of Berber civilization, unequaled until the coming of the Almohads and Almoravids more than a millennium later, was reached during the reign of Massinissa in the 2nd century BC.

After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, the Berber kingdoms were divided and reunited several times. Massinissa's line survived until 24 AD, when the remaining Berber territory was annexed to the Roman Empire.

For several centuries Algeria was ruled by the Romans, who founded many colonies in the region. Like the rest of North Africa, Algeria was one of the breadbaskets of the empire, exporting cereals and other agricultural products. Saint Augustine was the bishop of Hippo Regius (modern-day Algeria), located in the Roman province of Africa. The Germanic Vandals of Geiseric moved into North Africa in 429, and by 435 controlled coastal Numidia.[21] They did not make any significant settlement on the land, as they were harassed by local tribes, in fact by the time the Byzantines arrived Lepcis Magna was abandoned and the Msellata region was occupied by the indigenous Laguatan who had been busy facilitating an Amazigh political, military and cultural revival.[21][22]

Middle Ages

After negligible resistance from the locals, the Arabs conquered Algeria in the mid-7th century and a large number of the indigenous people converted to the new faith. After the fall of the Umayyad Caliphate, numerous local dynasties emerged, including the Aghlabids, Almohads, Abdalwadid, Zirids, Rustamids, Hammadids, Almoravids and the Fatimids.

During the Middle Ages, North Africa was home to many great Scholars, Saints, and Sovereigns including Judah Ibn Quraysh the first grammarian to suggest the Afroasiatic language family, the great Sufi masters Sidi Boumediene (Abu Madyan) and Sidi El Houari, as well as the Emirs Abd Al Mu'min and Yāghmūrasen. It was during this time period that the Fatimids or children of Fatima, daughter of Muhammad, came to the Maghreb. These "Fatimids" went on to found a long lasting dynasty stretching across the Maghreb, Hejaz, and the Levant, boasting a secular inner government, as well as a powerful army and navy, primarily made of Arabs and levantians extending from Algeria to their capital state of Cairo. The Fatimid caliphate began to collapse when its governors the Zirids seceded. In order to punish them the Fatimids sent the Arab Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym against them. The resultant war is recounted in the epic Tāghribāt. In Al-Tāghrībāt the Amazigh Zirid Hero Khālīfā Al-Zānatī asks daily, for duels, to defeat the Hilalan hero Ābu Zayd al-Hilalī and many other Arab knights in a string of victories. The Zirids, however, were ultimately defeated ushering in an adoption of Arab customs and culture. The indigenous Amazigh tribes, however, remained largely independent, and depending on tribe, location, and time controlled varying parts of the Maghreb, at times unifying it (as under the Fatimids). The Fatimid Islamic state, also known as Fatimid Caliphate made an Islamic empire that included North Africa, Sicily, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, the Red Sea coast of Africa, Tihamah, Hejaz, and Yemen.[23][24][25] Caliphates from Northern Africa traded with the other empires of their time, as well as forming part of a confederated support and trade network with other Islamic states during the Islamic Era.

The Amazighs historically consisted of several tribes. The two main branches were the Botr and Barnès tribes, who were divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, Sanhadja, Houara, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, and Berghwata). All these tribes made independent territorial decisions.[26]

Several Amazigh dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in the Maghreb and other nearby lands. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarizing the Amazigh dynasties of the Maghreb region, the Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid, Meknassa and Hafsid dynasties.[27]

In the early 16th century, Spain constructed fortified outposts (presidios) on or near the Algerian coast. Spain took control of few coastal towns like Mers el Kebir in 1505; Oran in 1509; and Tlemcen, Mostaganem, and Ténès, in 1510. In the same year, few merchants of Algiers ceded one of the rocky islets in their harbor to Spain, which built a fort on it. The presidios in North Africa turned out to be a costly and largely ineffective military endeavor that did not guarantee access for Spain's merchant fleet.[28]

Arabization

There reigned in Ifriqiya, current Tunisia, a Berber family, Zirid, somehow recognizing the suzerainty of the Fatimid caliph of Cairo. Probably in 1048, the Zirid ruler or viceroy, el-Mu'izz, decided to end this suzerainty. The Fatimid state was too weak to attempt a punitive expedition; The Viceroy, el-Mu'izz, also found another means of revenge.

Between the Nile and the Red Sea were living Bedouin tribes expelled from Arabia for their disruption and turbulent influence, both Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym among others, whose presence disrupted farmers in the Nile Valley since the nomads would often loot. The then Fatimid vizier devised to relinquish control of the Maghreb and obtained the agreement of his sovereign. This not only prompted the Bedouins to leave, but the Fatimid treasury even gave them a light expatriation cash allowance.

Whole tribes set off with women, children, ancestors, animals and camping equipment. Some stopped on the way, especially in Cyrenaica, where they are still one of the essential elements of the settlement but most arrived in Ifriqiya by the Gabes region. The Zirid ruler tried to stop this rising tide, but each meeting, the last under the walls of Kairouan, his troops were defeated and Arabs remained masters of the field.

The flood was still rising and in 1057, the Arabs spread on the high plains of Constantine where they gradually choked Qalaa of Banu Hammad, as they had done Kairouan few decades ago. From there, they gradually gained the upper Algiers and Oran plains, some were forcibly taken by the Almohads in the second half of the 12th century. We can say that in the 13th century there were in all of North Africa, with the exception of the main mountain ranges and certain coastal regions remained entirely Berber.

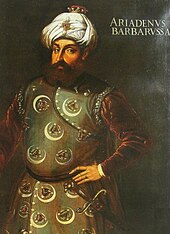

Ottoman Algeria

The region of Algeria was partially ruled by Ottomans for three centuries from 1516 to 1830. In 1516 the Turkish privateer brothers Aruj and Hayreddin Barbarossa, who operated successfully under the Hafsids, moved their base of operations to Algiers. They succeeded in conquering Jijel and Algiers from the Spaniards but eventually assumed control over the city and the surrounding region, forcing the previous ruler, Abu Hamo Musa III of the Bani Ziyad dynasty, to flee.[29] When Aruj was killed in 1518 during his invasion of Tlemcen, Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers. The Ottoman sultan gave him the title of beylerbey and a contingent of some 2,000 janissaries. With the aid of this force, Hayreddin conquered the whole area between Constantine and Oran (although the city of Oran remained in Spanish hands until 1791).[30]

The next beylerbey was Hayreddin's son Hasan, who assumed the position in 1544. Until 1587 the area was governed by officers who served terms with no fixed limits. Subsequently, with the institution of a regular Ottoman administration, governors with the title of pasha ruled for three-year terms. The pasha was assisted by janissaries, known in Algeria as the ojaq and led by an agha. Discontent among the ojaq rose in the mid-1600s because they were not paid regularly, and they repeatedly revolted against the pasha. As a result, the agha charged the pasha with corruption and incompetence and seized power in 1659.[30]

Plague had repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost from 30,000 to 50,000 inhabitants to the plague in 1620–21, and suffered high fatalities in 1654–57, 1665, 1691, and 1740–42.[31]

In 1671, the taifa rebelled, killed the agha, and placed one of its own in power. The new leader received the title of dey. After 1689, the right to select the dey passed to the divan, a council of some sixty nobles. It was at first dominated by the ojaq; but by the 18th century, it had become the dey's instrument. In 1710, the dey persuaded the sultan to recognize him and his successors as regent, replacing the pasha in that role, although Algiers remained a part of the Ottoman Empire.[30]

The dey was in effect a constitutional autocrat. The dey was elected for a life term, but in the 159 years (1671–1830) that the system survived, fourteen of the twenty-nine deys were assassinated. Despite usurpation, military coups, and occasional mob rule, the day-to-day operation of Ottomon government was remarkably orderly. Although the regency patronized the tribal chieftains, it never had the unanimous allegiance of the countryside, where heavy taxation frequently provoked unrest. Autonomous tribal states were tolerated, and the regency's authority was seldom applied in the Kabylie.[30]

Privateers era

The Barbary pirates preyed on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea.[31] The pirates often took the passengers and crew on the ships and sold them or used them as slaves.[32] They also did a brisk business in ransoming some of the captives. According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves.[33] They often made raids, called Razzias, on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire.[34][35]

In 1544, Hayreddin captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[36] In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending the captives to Libya. In 1554, pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy and took an estimated 7,000 captives as slaves.[37]

In 1558, Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and took 3,000 survivors as slaves to Istanbul.[38] Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response, the residents built many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches. The threat was so severe that residents abandoned the island of Formentera.[39]

Between 1609 and 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.[33]

In July 1627 two pirate ships from Algiers sailed as far as Iceland,[40] raiding and capturing slaves.[41][42][43] Two weeks earlier another pirate ship from Salé in Morocco had also raided in Iceland. Some of the slaves brought to Algiers were later ransomed back to Iceland, but some chose to stay in Algeria. In 1629 pirate ships from Algeria raided the Faroe Islands.[44]

In the 19th century, the pirates forged affiliations with Caribbean powers, paying a "license tax" in exchange for safe harbor of their vessels.[45] One American slave reported that the Algerians had enslaved 130 American seamen in the Mediterranean and Atlantic from 1785 to 1793.[46]

Piracy on American vessels in the Mediterranean resulted in the United States initiating the First (1801–1805) and Second Barbary Wars (1815). Following those wars, Algeria was weaker, and Europeans, with an Anglo-Dutch fleet commanded by the British Lord Exmouth, attacked Algiers. After a nine-hour bombardment, they obtained a treaty from the Dey that reaffirmed the conditions imposed by Decatur (US navy) concerning the demands of tributes. In addition, the Dey agreed to end the practice of enslaving Christians.[47]

French colonisation (1830–1962)

Under the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded and captured Algiers in 1830.[48][49] Algerine slave trade and piracy ceased when the French conquered Algiers.[50] The conquest of Algeria by the French took some time and resulted in considerable bloodshed. A combination of violence and disease epidemics caused the indigenous Algerian population to decline by nearly one-third from 1830 to 1872.[51][unreliable source?] The population of Algeria, which stood at about 1.5 million in 1830, reached nearly 11 million in 1960.[52] French policy was predicated on "civilizing" the country.[53] During this period, a small but influential French-speaking indigenous elite was formed, made up of Berbers, mostly Kabyles. As a consequence, French government favored the Kabyles.[54] About 80% of Indigenous schools were constructed for Kabyles.

From 1848 until independence, France administered the whole Mediterranean region of Algeria as an integral part and département of the nation. One of France's longest-held overseas territories, Algeria became a destination for hundreds of thousands of European immigrants, who became known as colons and later, as Pied-Noirs. Between 1825 and 1847, 50,000 French people immigrated to Algeria.[55][page needed] These settlers benefited from the French government's confiscation of communal land from tribal peoples, and the application of modern agricultural techniques that increased the amount of arable land.[56] Many Europeans settled in Oran and Algiers, and by the early 20th century they formed a majority of the population in both cities.[57]

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century; the European share was almost a fifth of the population. The French government aimed at making Algeria an assimilated part of France, and this included substantial educational investments especially after 1900. The indigenous cultural and religious resistance heavily opposed this tendency, but in contrast to the other colonized countries path in central Asia and Caucasus, Algeria kept its individual skills and a relatively human-capital intensive agriculture.[58]

Gradually, dissatisfaction among the Muslim population, which lacked political and economic status in the colonial system, gave rise to demands for greater political autonomy, and eventually independence from France. Tensions between the two population groups came to a head in 1954, when the first violent events of what was later called the Algerian War began. Historians have estimated that between 30,000 and 150,000 Harkis and their dependents were killed by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) or by lynch mobs in Algeria.[59] The FLN used hit and run attacks in Algeria and France as part of its war, and the French conducted severe reprisals. The war led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Algerians and hundreds of thousands of injuries.

The war against French rule concluded in 1962, when Algeria gained complete independence following the March 1962 Evian agreements and the July 1962 self-determination referendum.

The first three decades of independence (1962–1991)

The number of European Pied-Noirs who fled Algeria totaled more than 900,000 between 1962 and 1964.[60] The exodus to mainland France accelerated after the Oran massacre of 1962, in which hundreds of militants entered European sections of the city, and began attacking civilians.

Algeria's first president was the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) leader Ahmed Ben Bella. Morocco's claim to portions of western Algeria led to the Sand War in 1963. Ben Bella was overthrown in 1965 by Houari Boumediene, his former ally and defence minister. Under Ben Bella, the government had become increasingly socialist and authoritarian; Boumédienne continued this trend. But, he relied much more on the army for his support, and reduced the sole legal party to a symbolic role. He collectivised agriculture and launched a massive industrialization drive. Oil extraction facilities were nationalized. This was especially beneficial to the leadership after the international 1973 oil crisis.

In the 1960s and 1970s under President Houari Boumediene, Algeria pursued a programme of industrialisation within a state-controlled socialist economy. Boumediene's successor, Chadli Bendjedid, introduced some liberal economic reforms. He promoted a policy of Arabisation in Algerian society and public life. Teachers of Arabic, brought in from other Muslim countries, spread conventional Islamic thought in schools and sowed the seeds of a return to Orthodox Islam.[61]

The Algerian economy became increasingly dependent on oil, leading to hardship when the price collapsed during the 1980s oil glut.[62] Economic recession caused by the crash in world oil prices resulted in Algerian social unrest during the 1980s; by the end of the decade, Bendjedid introduced a multi-party system. Political parties developed, such as the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), a broad coalition of Muslim groups.[61]

Civil War (1991–2002) and aftermath

In December 1991 the Islamic Salvation Front dominated the first of two rounds of legislative elections. Fearing the election of an Islamist government, the authorities intervened on 11 January 1992, cancelling the elections. Bendjedid resigned and a High Council of State was installed to act as Presidency. It banned the FIS, triggering a civil insurgency between the Front's armed wing, the Armed Islamic Group, and the national armed forces, in which more than 100,000 people are thought to have died. The Islamist militants conducted a violent campaign of civilian massacres.[63] At several points in the conflict, the situation in Algeria became a point of international concern, most notably during the crisis surrounding Air France Flight 8969, a hijacking perpetrated by the Armed Islamic Group. The Armed Islamic Group declared a ceasefire in October 1997.[61]

Algeria held elections in 1999, considered biased by international observers and most opposition groups[64] which were won by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. He worked to restore political stability to the country and announced a 'Civil Concord' initiative, approved in a referendum, under which many political prisoners were pardoned, and several thousand members of armed groups were granted exemption from prosecution under a limited amnesty, in force until 13 January 2000. The AIS disbanded and levels of insurgent violence fell rapidly. The Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat (GSPC), a splinter group of the Group Islamic Armée, continued a terrorist campaign against the Government.[61]

Bouteflika was re-elected in the April 2004 presidential election after campaigning on a programme of national reconciliation. The programme comprised economic, institutional, political and social reform to modernise the country, raise living standards, and tackle the causes of alienation. It also included a second amnesty initiative, the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation, which was approved in a referendum in September 2005. It offered amnesty to most guerrillas and Government security forces.[61]

In November 2008, the Algerian Constitution was amended following a vote in Parliament, removing the two-term limit on Presidential incumbents. This change enabled Bouteflika to stand for re-election in the 2009 presidential elections, and he was re-elected in April 2009. During his election campaign and following his re-election, Bouteflika promised to extend the programme of national reconciliation and a $150-billion spending programme to create three million new jobs, the construction of one million new housing units, and to continue public sector and infrastructure modernisation programmes.[61]

A continuing series of protests throughout the country started on 28 December 2010, inspired by similar protests across the Middle East and North Africa. On 24 February 2011, the government lifted Algeria's 19-year-old state of emergency.[65] The government enacted legislation dealing with political parties, the electoral code, and the representation of women in elected bodies.[66] In April 2011, Bouteflika promised further constitutional and political reform.[61] However, elections are routinely criticized by opposition groups as unfair and international human rights groups say that media censorship and harassment of political opponents continue.

Geography

-

The Djurdjura Range in snow

-

The Tadrart Rouge near Djanet.

-

Ouarsenis, range of mountains in North-Western (1985m)

-

Maritime front of Bejaïa

-

The Tassili n'Ajjer.

Algeria is the largest country in Africa, the Arab world, and the Mediterranean Basin. Its southern part includes a significant portion of the Sahara. To the north, the Tell Atlas form with the Saharan Atlas, further south, two parallel sets of reliefs in approaching eastbound, and between which are inserted vast plains and highlands. Both Atlas tend to merge in eastern Algeria. The vast mountain ranges of Aures and Nememcha occupy the entire northeastern Algeria and are delineated by the Tunisian border. The highest point is Mount Tahat (3,003 m).

Algeria lies mostly between latitudes 19° and 37°N (a small area is north of 37°), and longitudes 9°W and 12°E. Most of the coastal area is hilly, sometimes even mountainous, and there are a few natural harbours. The area from the coast to the Tell Atlas is fertile. South of the Tell Atlas is a steppe landscape ending with the Saharan Atlas; farther south, there is the Sahara desert.[67]

The Ahaggar Mountains (Template:Lang-ar), also known as the Hoggar, are a highland region in central Sahara, southern Algeria. They are located about 1,500 km (932 mi) south of the capital, Algiers, and just west of Tamanghasset. Algiers, Oran, Constantine, and Annaba are Algeria's main cities.[67]

Climate and hydrology

In this region, midday desert temperatures can be hot year round. After sunset, however, the clear, dry air permits rapid loss of heat, and the nights are cool to chilly. Enormous daily ranges in temperature are recorded.

Rainfall is fairly plentiful along the coastal part of the Tell Atlas, ranging from 400 to 670 mm (15.7 to 26.4 in) annually, the amount of precipitation increasing from west to east. Precipitation is heaviest in the northern part of eastern Algeria, where it reaches as much as 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in some years.

Farther inland, the rainfall is less plentiful. Algeria also has ergs, or sand dunes, between mountains. Among these, in the summer time when winds are heavy and gusty, temperatures can get up to 43.3 °C (110 °F).

Fauna and flora

The varied vegetation of Algeria includes coastal, mountainous and grassy desert-like regions which all support a wide range of wildlife. Many of the creatures comprising the Algerian wildlife live in close proximity to civilization. The most commonly seen animals include the wild boars, jackals, and gazelles, although it is not uncommon to spot fennecs (foxes), and jerboas. Algeria also has a small African leopard and Saharan cheetah population, but these are seldom seen. A species of deer, the Barbary stag, inhabits the dense humid forests in the north-eastern areas.

A variety of bird species makes the country an attraction for bird watchers. The forests are inhabited by boars and jackals. Barbary macaques are the sole native monkey. Snakes, monitor lizards, and numerous other reptiles can be found living among an array of rodents throughout the semi arid regions of Algeria. Many animals are now extinct, including the Barbary lions, Atlas bears and crocodiles.[68]

In the north, some of the native flora includes Macchia scrub, olive trees, oaks, cedars and other conifers. The mountain regions contain large forests of evergreens (Aleppo pine, juniper, and evergreen oak) and some deciduous trees. Fig, eucalyptus, agave, and various palm trees grow in the warmer areas. The grape vine is indigenous to the coast. In the Sahara region, some oases have palm trees. Acacias with wild olives are the predominant flora in the remainder of the Sahara.

Camels are used extensively; the desert also abounds with venomous and nonvenomous snakes, scorpions, and numerous insects.

Politics

Elected politicians are considered to have relatively little sway over Algeria. Instead, a group of unelected civilian and military "décideurs", known as "le pouvoir" ("the power"), actually rule the country, even deciding who should be president. The most powerful man may be Mohamed Mediène, head of the military intelligence.[69] In recent years, many of these generals have died or retired. After the death of General Larbi Belkheir, Bouteflika put loyalists in key posts, notably at Sonatrach, and secured constitutional amendments that make him re-electable indefinitely.[70]

The head of state is the president of Algeria, who is elected for a five-year term. The president was formerly limited to two five-year terms, but a constitutional amendment passed by the Parliament on 11 November 2008 removed this limitation.[71] Algeria has universal suffrage at 18 years of age.[5] The President is the head of the army, the Council of Ministers and the High Security Council. He appoints the Prime Minister who is also the head of government.[72]

The Algerian parliament is bicameral; the lower house, the People's National Assembly, has 462 members who are directly elected for five-year terms, while the upper house, the Council of the Nation, has 144 members serving six-year terms, of which 96 members are chosen by local assemblies and 48 are appointed by the president.[73] According to the constitution, no political association may be formed if it is "based on differences in religion, language, race, gender, profession, or region". In addition, political campaigns must be exempt from the aforementioned subjects.[74]

Parliamentary elections were last held in May 2012, and were judged to be largely free by international monitors, though local groups alleged fraud and irregularities.[73] In the elections, the FLN won 221 seats, the military-backed National Rally for Democracy won 70, and the Islamist Green Algeria Alliance won 47.[73]

Foreign relations

Tensions between Algeria and Morocco in relation to the Western Sahara have been an obstacle to tightening the Arab Maghreb Union, nominally established in 1989, but which has carried little practical weight.[75]

Algeria is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer. Giving incentives and rewarding best performers, as well as offering funds in a faster and more flexible manner, are the two main principles underlying the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) that came into force in 2014. It has a budget of €15.4 billion and provides the bulk of funding through a number of programmes.

In 2009, the French government agreed to compensate victims of nuclear tests in Algeria. Defense Minister Herve Morin stated that “It’s time for our country to be at peace with itself, at piece thanks to a system of compensation and reparations,” when presenting the draft law on the payouts. Algerian officials and activists believe that this is a good first step and hope that this move would encourage broader reparation.[76]

Military

The military of Algeria consists of the People's National Army (ANP), the Algerian National Navy (MRA), and the Algerian Air Force (QJJ), plus the Territorial Air Defence Forces.[5] It is the direct successor of the National Liberation Army (Armée de Libération Nationale or ALN), the armed wing of the nationalist National Liberation Front which fought French colonial occupation during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62).

Total military personnel include 147,000 active, 150,000 reserve, and 187,000 paramilitary staff (2008 estimate).[77] Service in the military is compulsory for men aged 19–30, for a total of 12 months.[78] The military expenditure was 4.3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012.[5] Algeria has the second largest military in North Africa with the largest defence budget in Africa ($10 billion).[12]

In 2007, the Algerian Air Force signed a deal with Russia to purchase 49 MiG-29SMT and 6 MiG-29UBT at an estimated cost of $1.9 billion. Russia is also building two 636-type diesel submarines for Algeria.[79]

Administrative divisions

Algeria is divided into 48 provinces (wilayas), 553 districts (daïras) and 1,541 municipalities (baladiyahs). Each province, district, and municipality is named after its seat, which is usually the largest city.

The administrative divisions have changed several times since independence. When introducing new provinces, the numbers of old provinces are kept, hence the non-alphabetical order. With their official numbers, currently (since 1983) they are[5]

| # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population | map | # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adrar | 402,197 | 439,700 |  |

30 | Ouargla | 211,980 | 552,539 |

| 2 | Chlef | 4,975 | 1,013,718 | 31 | Oran | 2,114 | 1,584,607 | |

| 3 | Laghouat | 25,057 | 477,328 | 32 | El Bayadh | 78,870 | 262,187 | |

| 4 | Oum El Bouaghi | 6,768 | 644,364 | 33 | Illizi | 285,000 | 54,490 | |

| 5 | Batna | 12,192 | 1,128,030 | 34 | Bordj Bou Arréridj | 4,115 | 634,396 | |

| 6 | Béjaïa | 3,268 | 915,835 | 35 | Boumerdes | 1,591 | 795,019 | |

| 7 | Biskra | 20,986 | 730,262 | 36 | El Taref | 3,339 | 411,783 | |

| 8 | Béchar | 161,400 | 274,866 | 37 | Tindouf | 58,193 | 159,000 | |

| 9 | Blida | 1,696 | 1,009,892 | 38 | Tissemsilt | 3,152 | 296,366 | |

| 10 | Bouïra | 4,439 | 694,750 | 39 | El Oued | 54,573 | 673,934 | |

| 11 | Tamanrasset | 556,200 | 198,691 | 40 | Khenchela | 9,811 | 384,268 | |

| 12 | Tébessa | 14,227 | 657,227 | 41 | Souk Ahras | 4,541 | 440,299 | |

| 13 | Tlemcen | 9,061 | 945,525 | 42 | Tipaza | 2,166 | 617,661 | |

| 14 | Tiaret | 20,673 | 842,060 | 43 | Mila | 9,375 | 768,419 | |

| 15 | Tizi Ouzou | 3,568 | 1,119,646 | 44 | Ain Defla | 4,897 | 771,890 | |

| 16 | Algiers | 273 | 2,947,461 | 45 | Naâma | 29,950 | 209,470 | |

| 17 | Djelfa | 66,415 | 1,223,223 | 46 | Ain Timouchent | 2,376 | 384,565 | |

| 18 | Jijel | 2,577 | 634,412 | 47 | Ghardaia | 86,105 | 375,988 | |

| 19 | Sétif | 6,504 | 1,496,150 | 48 | Relizane | 4,870 | 733,060 | |

| 20 | Saïda | 6,764 | 328,685 | 49 | Touggourt | 8,835 | 162,267 | |

| 21 | Skikda | 4,026 | 904,195 | 50 | Bordj Baji Mokhtar | 62,215 | 57,276 | |

| 22 | Sidi Bel Abbès | 9,150 | 603,369 | 51 | Ouled Djellal | 11,410 | 174,219 | |

| 23 | Annaba | 1,439 | 640,050 | 52 | Béni Abbès | 120,026 | 16,437 | |

| 24 | Guelma | 4,101 | 482,261 | 53 | In Salah | 101,350 | 50,163 | |

| 25 | Constantine | 2,187 | 943,112 | 54 | In Guezzam | 65,203 | 122,019 | |

| 26 | Médéa | 8,866 | 830,943 | 55 | Touggourt | 17,428 | 247,221 | |

| 27 | Mostaganem | 2,269 | 746,947 | 56 | Djanet | 86,185 | 17,618 | |

| 28 | M'Sila | 18,718 | 991,846 | 57 | El M'Ghair | 131,220 | 50,392 | |

| 29 | Mascara | 5,941 | 780,959 | 58 | El Menia | 88,126 | 11,202 |

Economy

Algeria is classified as an upper middle income country by the World Bank.[80] Algeria's currency is the dinar (DZD). The economy remains dominated by the state, a legacy of the country's socialist post-independence development model. In recent years, the Algerian government has halted the privatization of state-owned industries and imposed restrictions on imports and foreign involvement in its economy.[5]

Algeria has struggled to develop industries outside hydrocarbons in part because of high costs and an inert state bureaucracy. The government's efforts to diversify the economy by attracting foreign and domestic investment outside the energy sector have done little to reduce high youth unemployment rates or to address housing shortages.[5] The country is facing a number of short-term and medium-term problems, including the need to diversify the economy, strengthen political, economic and financial reforms, improve the business climate and reduce inequalities amongst regions.[66]

A wave of economic protests in February and March 2011 prompted the Algerian government to offer more than $23 billion in public grants and retroactive salary and benefit increases. Public spending has increased by 27% annually during the past 5 years. The 2010–14 public-investment programme will cost US$286 billion, 40% of which will go to human development.[66]

The Algerian economy grew by 2.6% in 2011, driven by public spending, in particular in the construction and public-works sector, and by growing internal demand. If hydrocarbons are excluded, growth has been estimated at 4.8%. Growth of 3% is expected in 2012, rising to 4.2% in 2013. The rate of inflation was 4% and the budget deficit 3% of GDP. The current-account surplus is estimated at 9.3% of GDP and at the end of December 2011, official reserves were put at US$182 billion.[66] Inflation, the lowest in the region, has remained stable at 4% on average between 2003 and 2007.[81]

In 2011 Algeria announced a budgetary surplus of $26.9 billion, 62% increase in comparison to 2010 surplus. In general, the country exported $73 billion worth of commodities while it imported $46 billion.[82]

Thanks to strong hydrocarbon revenues, Algeria has a cushion of $173 billion in foreign currency reserves and a large hydrocarbon stabilization fund. In addition, Algeria's external debt is extremely low at about 2% of GDP.[5] The economy remains very dependent on hydrocarbon wealth, and, despite high foreign exchange reserves (US$178 billion, equivalent to three years of imports), current expenditure growth makes Algeria's budget more vulnerable to the risk of prolonged lower hydrocarbon revenues.[83]

In 2011, the agricultural sector and services recorded growth of 10% and 5.3%, respectively.[66] About 14% of the labor force are employed in the agricultural sector.[5] Fiscal policy in 2011 remained expansionist and made it possible to maintain the pace of public investment and to contain the strong demand for jobs and housing.[66]

Algeria has not joined the WTO, despite several years of negotiations.[84]

In March 2006, Russia agreed to erase $4.74 billion of Algeria's Soviet-era debt[85] during a visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin to the country, the first by a Russian leader in half a century. In return, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika agreed to buy $7.5 billion worth of combat planes, air-defence systems and other arms from Russia, according to the head of Russia's state arms exporter Rosoboronexport.[86][87]

Dubai-based conglomerate Emarat Dzayer Group said it had signed a joint venture agreement to develop a $1.6 billion steel factory in Algeria.[88]

Hydrocarbons

Algeria, whose economy is reliant on petroleum, has been an OPEC member since 1969. Its crude oil production stands at around 1.1 million barrels/day, but it is also a major gas producer and exporter, with important links to Europe.[89] Hydrocarbons have long been the backbone of the economy, accounting for roughly 60% of budget revenues, 30% of GDP, and over 95% of export earnings. Algeria has the 10th-largest reserves of natural gas in the world and is the sixth-largest gas exporter. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that in 2005, Algeria had 160 trillion cubic feet (4.5×1012 m3) of proven natural-gas reserves.[90] It also ranks 16th in oil reserves.[5]

Non-hydrocarbon growth for 2011 was projected at 5%. To cope with social demands, the authorities raised expenditure, especially on basic food support, employment creation, support for SMEs, and higher salaries. High hydrocarbon prices have improved the current account and the already large international reserves position.[83]

Income from oil and gas rose in 2011 as a result of continuing high oil prices, though the trend in production volume is downwards.[66] Production from the oil and gas sector in terms of volume, continues to decline, dropping from 43.2 million tonnes to 32 million tonnes between 2007 and 2011. Nevertheless, the sector accounted for 98% of the total volume of exports in 2011, against 48% in 1962,[91] and 70% of budgetary receipts, or USD 71.4 billion.[66]

The Algerian national oil company is Sonatrach, which plays a key role in all aspects of the oil and natural gas sectors in Algeria. All foreign operators must work in partnership with Sonatrach, which usually has majority ownership in production-sharing agreements.[92]

Research and Alternative Energy Sources

Algeria has invested an estimated 100 billion dinars towards developing research facilities and paying researchers. This development program is meant to advance alternative energy production, especially solar and wind power.[93] Algeria is estimated to have the largest solar energy potential in the Mediterranean, so the government has funded the creation of a solar science park in Hassi R’Mel. Currently, Algeria has 20,000 research professors at various universities and over 780 research labs, with state-set goals to expand to 1,000. Besides solar energy, areas of research in Algeria include space and satellite telecommunications, nuclear power and medical research.

Labour market

Despite a decline in total unemployment, youth and women unemployment is high.[83] Unemployment particularly affects the young, with a jobless rate of 21.5% among the 15–24 age group.[66]

The overall rate of unemployment was 10% in 2011, but remained higher among young people, with a rate of 21.5% for those aged between 15 and 24. The government strengthened in 2011 the job programmes introduced in 1988, in particular in the framework of the programme to aid those seeking work (Dispositif d'Aide à l'Insertion Professionnelle).[66]

Tourism

The development of the tourism sector in Algeria had previously been hampered by a lack of facilities, but since 2004 a broad tourism development strategy has been implemented resulting in many hotels of a high modern standard being built.

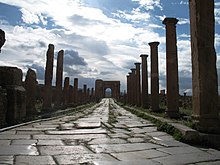

There are several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Algeria[94] including Al Qal'a of Beni Hammad, the first capital of the Hammadid empire; Tipasa, a Phoenician and later Roman town; and Djémila and Timgad, both Roman ruins; M'Zab Valley, a limestone valley containing a large urbanized oasis; also the Casbah of Algiers is an important citadel. The only natural World Heritage Sites is the Tassili n'Ajjer, a mountain range.

Transport

The Algerian road network is the densest in Africa; its length is estimated at 180,000 km of highways, with more than 3,756 structures and a paving rate of 85%. This network will be complemented by the East-West Highway, a major infrastructure project currently under construction. It is a 3-way, 1,216 km long highway, linking Annaba in the extreme east to the Tlemcen in the far west. Algeria is also crossed by the Trans-Sahara Highway, which is now completely paved. This road is supported by the Algerian government to increase trade between the six countries crossed: Algeria, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Chad and Tunisia.

Water supply and sanitation

There is a substantial increase in the amount of drinking water supplied from reservoirs, long-distance water transfers and desalination at a low price to consumers, thanks to the country's substantial oil and gas revenues. In 2011 the capital Algiers transformed its intermittent water supply into a to continuous one, along with considerable improvements in wastewater treatment. However, there is still poor service quality in many cities outside Algiers with 78% of urban residents suffering from intermittent water supply. Another challenge is the pollution of water resources.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1856 | 2,496 | — |

| 1872 | 2,416 | −0.20% |

| 1886 | 3,752 | +3.19% |

| 1906 | 4,721 | +1.16% |

| 1926 | 5,444 | +0.72% |

| 1931 | 5,902 | +1.63% |

| 1936 | 6,510 | +1.98% |

| 1948 | 7,787 | +1.50% |

| 1954 | 8,615 | +1.70% |

| 1966 | 12,022 | +2.82% |

| 1977 | 16,948 | +3.17% |

| 1987 | 23,051 | +3.12% |

| 1998 | 29,113 | +2.15% |

| 2008 | 34,080 | +1.59% |

| 2013 | 37,900 | +2.15% |

| Source: (1856–1872)[95] (1886–2008)[96] | ||

In January 2016 Algeria's population was an estimated 40.4 million, who are mainly Arab-Berber ethnically.[5][97][98] At the outset of the 20th century, its population was approximately four million.[99] About 90% of Algerians live in the northern, coastal area; the inhabitants of the Sahara desert are mainly concentrated in oases, although some 1.5 million remain nomadic or partly nomadic. 28.1% of Algerians are under the age of 15.[5]

Women make up 70% of the country's lawyers and 60% of its judges and also dominate the field of medicine. Increasingly, women are contributing more to household income than men. 60% of university students are women, according to university researchers.[100]

Between 90,000 and 165,000 Sahrawis from Western Sahara live in the Sahrawi refugee camps,[101][102] in the western Algerian Sahara desert.[103] There are also more than 4,000 Palestinian refugees, who are well integrated and have not asked for assistance from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[101][102] In 2009, 35,000 Chinese migrant workers lived in Algeria.[104]

The largest concentration of Algerian migrants outside Algeria is in France, which has reportedly over 1.7 million Algerians of up to the second generation.[105]

Ethnic groups

Indigenous Berbers as well as Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Turks, various Sub-Saharan Africans, and French have contributed to the history of Algeria.[106] Descendants of Andalusian refugees are also present in the population of Algiers and other cities.[107] Moreover, Spanish was spoken by these Aragonese and Castillian Morisco descendants deep into the 18th century, and even Catalan was spoken at the same time by Catalan Morisco descendants in the small town of Grish El-Oued.[108]

There are 600,000 to 2 million former Algerian Turks, descendants of Turkish rulers, soldiers, doctors and others who ruled the region during the Ottoman rule in North Africa.[109][110] Today's Turkish descendants are often called Kouloughlis, meaning descendants of Turkish men and native Algerian women.[111][112]

Despite the dominance of the Berber culture and ethnicity in Algeria, majority of Algerians identify with an Arabic-based identity, especially after the Arab nationalism rising in the 20th century.[113][114] Berbers and Berber-speaking Algerians are divided into many groups with varying languages. The largest of these are the Kabyles, who live in the Kabylie region east of Algiers, the Chaoui of Northeast Algeria, the Tuaregs in the southern desert and the Shenwa people of North Algeria.[115][page needed]

During the colonial period, there was a large (10% in 1960)[116] European population who became known as Pied-Noirs. They were primarily of French, Spanish and Italian origin. Almost all of this population left during the war of independence or immediately after its end.[117]

Languages

Modern Standard Arabic is the official language.[118] Algerian Arabic (Darja) is the language used by the majority of the population. Colloquial Algerian Arabic is heavily infused with borrowings from French and Berber.

Berber has been recognized as a "national language" by the constitutional amendment of 8 May 2002.[119] Kabyle, the predominant Berber language, is taught and is partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylie. In February 2016, the Algerian constitution passed a resolution that would make Berber an official language alongside Arabic.

Although French has no official status, Algeria is the second-largest Francophone country in the world in terms of speakers,[120] and French is widely used in government, media (newspapers, radio, local television), and both the education system (from primary school onwards) and academia due to Algeria's colonial history. It can be regarded as the de facto co-official language of Algeria. In 2008, 11.2 million Algerians could read and write in French.[121] An Abassa Institute study in April 2000 found that 60% of households could speak and understand French or 18 million in a population of 30 million then. In recent decades the government has reinforced the study of French and TV programs have reinforced use of the language.

Algeria emerged as a bilingual state after 1962.[122] Colloquial Algerian Arabic is spoken by about 72% of the population and Berber by 27–30%.[123]

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion in Algeria, with its adherents accounting for 99% of the population.[5] There are about 150,000 Ibadis in the M'zab Valley in the region of Ghardaia.[125]

Estimates of the number of Christians in Algeria vary. A BBC news article in 2008 stated there were an estimated 10,000 Christians in Algeria.[126] In a 2009[further explanation needed] study the UNO[who?][failed verification] estimated there were 45,000 Catholics[127] and 50,000–100,000[failed verification] Protestants in Algeria.[128] A 2015 study estimated there were 380,000 "believers in Christ from a Muslim background" in Algeria.[129]

Following the Revolution and Algerian independence, all but 6,500 of the country's 140,000 Jews left the country, of whom about 90% moved to France with the Pied-Noirs and 10% left for Israel.[citation needed]

Algeria has given the Muslim world a number of prominent thinkers, including Emir Abdelkader, Abdelhamid Ibn Badis, Mouloud Kacem Nait-Belkacem, Malek Bennabi, and Mohamed Arkoun.[citation needed]

Cities

Below is a list of the most important Algerian cities: Template:Largest cities of Algeria

Culture

Modern Algerian literature, split between Arabic, Tamazight and French, has been strongly influenced by the country's recent history. Famous novelists of the 20th century include Mohammed Dib, Albert Camus, Kateb Yacine and Ahlam Mosteghanemi while Assia Djebar is widely translated. Among the important novelists of the 1980s were Rachid Mimouni, later vice-president of Amnesty International, and Tahar Djaout, murdered by an Islamist group in 1993 for his secularist views.[130]

Malek Bennabi and Frantz Fanon are noted for their thoughts on decolonization; Augustine of Hippo was born in Tagaste (modern-day Souk Ahras); and Ibn Khaldun, though born in Tunis, wrote the Muqaddima while staying in Algeria. The works of the Sanusi family in pre-colonial times, and of Emir Abdelkader and Sheikh Ben Badis in colonial times, are widely noted. The Latin author Apuleius was born in Madaurus (Mdaourouch), in what later became Algeria.

Contemporary Algerian cinema is various in terms of genre, exploring a wider range of themes and issues. There has been a transition from cinema which focused on the war of independence to films more concerned with the everyday lives of Algerians.[131]

Art

Algerian painters, like Mohamed Racim or Baya, attempted to revive the prestigious Algerian past prior to French colonization, at the same time that they have contributed to the preservation of the authentic values of Algeria. In this line, Mohamed Temam, Abdelkhader Houamel have also returned through this art, scenes from the history of the country, the habits and customs of the past and the country life. Other new artistic currents including the one of M'hamed Issiakhem, Mohammed Khadda and Bachir Yelles, appeared on the scene of Algerian painting, abandoning figurative classical painting to find new pictorial ways, in order to adapt Algerian paintings to the new realities of the country through its struggle and its aspirations. Mohammed Khadda[132] and M'hamed Issiakhem have been notable in recent years.[132]

Literature

The historic roots of Algerian literature goes back to the Numidian era, when Apuleius wrote The Golden Ass, the only Latin novel to survive in its entirety. This period had also known Augustine of Hippo, Nonius Marcellus and Martianus Capella, among many others. The Middle Ages have known many Arabic writers who revolutionized the Arab world literature, with authors like Ahmad al-Buni, Ibn Manzur and Ibn Khaldoun, who wrote the Muqaddimah while staying in Algeria, and many others.

Albert Camus was an Algerian-born French Pied-Noir author. In 1957 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature.

Today Algeria contains, in its literary landscape, big names having not only marked the Algerian literature, but also the universal literary heritage in Arabic and French.

As a first step, Algerian literature was marked by works whose main concern was the assertion of the Algerian national entity, there is the publication of novels as the Algerian trilogy of Mohammed Dib, or even Nedjma of Kateb Yacine novel which is often regarded as a monumental and major work. Other known writers will contribute to the emergence of Algerian literature whom include Mouloud Feraoun, Malek Bennabi, Malek Haddad, Moufdi Zakaria, Abdelhamid Ben Badis, Mohamed Laïd Al-Khalifa, Mouloud Mammeri, Frantz Fanon, and Assia Djebar.

In the aftermath of the independence, several new authors emerged on the Algerian literary scene, they will attempt through their works to expose a number of social problems, among them there are Rachid Boudjedra, Rachid Mimouni, Leila Sebbar, Tahar Djaout and Tahir Wattar.

Currently, a part of Algerian writers tends to be defined in a literature of shocking expression, due to the terrorism that occurred during the 1990s, the other party is defined in a different style of literature who staged an individualistic conception of the human adventure. Among the most noted recent works, there is the writer, the swallows of Kabul and the attack of Yasmina Khadra, the oath of barbarians of Boualem Sansal, memory of the flesh of Ahlam Mosteghanemi and the last novel by Assia Djebar nowhere in my father's House.

Music

Chaâbi music is a typically Algerian musical genre characterized by specific rhythms and of Qacidate (Popular poems) in Arabic dialect. The undisputed master of this music is El Hadj M'Hamed El Anka. The Constantinois Malouf style is saved by musician from whom Mohamed Tahar Fergani is a performer.

Folk music styles include Bedouin music, characterized by the poetic songs based on long kacida (poems); Kabyle music, based on a rich repertoire that is poetry and old tales passed through generations; Shawiya music, a folklore from diverse areas of the Aurès Mountains. Rahaba music style is unique to the Aures. Souad Massi is a rising Algerian folk singer. Other Algerian singers of the diaspora include Manel Filali in Germany and Kenza Farah in France. Tergui music is sung in Tuareg languages generally, Tinariwen had a worldwide success. Finally, the staïfi music is born in Sétif and remains a unique style of its kind.

Modern music is available in several facets, Raï music is a style typical of Western Algeria. Rap, relatively recent style in Algeria, is experiencing significant growth.

Cinema

The Algerian state's interest in film-industry activities can be seen in the annual budget of DZD 200 million (EUR 1.8) allocated to production, specific measures and an ambitious programme plan implemented by the Ministry of Culture in order to promote national production, renovate the cinema stock and remedy the weak links in distribution and exploitation.

The financial support provided by the state, through the Fund for the Development of the Arts, Techniques and the Film Industry (FDATIC) and the Algerian Agency for Cultural Influence (AARC), plays a key role in the promotion of national production. Between 2007 and 2013, FDATIC subsidised 98 films (feature films, documentaries and short films). In mid-2013, AARC had already supported a total of 78 films, including 42 feature films, 6 short films and 30 documentaries.

According to the European Audiovisual Observatory's LUMIERE database, 41 Algerian films were distributed in Europe between 1996 and 2013; 21 films in this repertoire were Algerian-French co-productions. (Days of Glory) (2006) and Outside the Law (2010) recorded the highest number of admissions in the European Union, 3,172,612 and 474,722, respectively.[134]

Algeria won the Palme d'Or for Chronicle of the Years of Fire (1975), two Oscars for Z (1969), and other awards for The Battle of Algiers.

Sports

Various games have existed in Algeria since antiquity. In the Aures, people played several games such As El Kherdba or El khergueba (chess variant). Playing cards, checkers and chess games are part of Algerian culture. Racing (fantasia) and the rifle shooting are part of cultural recreation of the Algerians.[135]

The first Algerian and African gold medalist is Boughera El Ouafi in 1928 Olympics of Amsterdam in the Marathon. The second Algerian Medalist was Alain Mimoun in 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne. Several men and women were champions in athletics in the 1990s including Noureddine Morceli, Hassiba Boulmerka, Nouria Merah-Benida, and Taoufik Makhloufi, all specialized in middle distance running.[136]

Football is the most popular sport in Algeria. Several names are engraved in the history of the sport, including Lakhdar Belloumi, Rachid Mekhloufi, Hassen Lalmas, Rabah Madjer, Salah Assad and Djamel Zidane. The Algeria national football team qualified for the 1982 FIFA World Cup, 1986 FIFA World Cup, 2010 FIFA World Cup and 2014 FIFA World Cup. In addition, several football clubs have won continental and international trophies as the club ES Sétif or JS Kabylia. The Algerian Football Federation is an association of Algeria football clubs organizing national competitions and international matches of the selection of Algeria national football team.[137]

Cuisine

Algerian cuisine is rich and diverse. The country was considered as the "granary of Rome". It offers a component of dishes and varied dishes, depending on the region and according to the seasons. The cuisine uses cereals as the main products, since they are always produced with abundance in the country. There is not a dish where cereals are not present.

Algerian cuisine varies from one region to another, according to seasonal vegetables. It can be prepared using meat, fish and vegetables. Among the dishes known, couscous,[138] chorba, Rechta, Chakhchoukha, Berkoukes, Shakshouka, Mthewem, Chtitha, Mderbel, Dolma, Brik or Bourek, Garantita, Lham'hlou, etc. Merguez sausage is widely used in Algeria, but it differs, depending on the region and on the added spices.

Cakes are marketed and can be found in cities either in Algeria, in Europe or North America. However, traditional cakes are also made at home, following the habits and customs of each family. Among these cakes, there are Tamina, Chrik, Garn logzelles, Griouech, Kalb el-louz, Makroud, Mbardja, Mchewek, Samsa, Tcharak, Baghrir, Khfaf, Zlabia, Aarayech, Ghroubiya and Mghergchette. Algerian pastry also contains Tunisian or French cakes. Marketed and home-made bread products include varieties such as Kessra or Khmira or Harchaya, chopsticks and so-called washers Khoubz dar or Matloue. Other tradionel meals (Chakhchokha-Hassoua-T'chicha-Mahjouba and Doubara) are famous in Biskra.

Health

In 2002, Algeria had inadequate numbers of physicians (1.13 per 1,000 people), nurses (2.23 per 1,000 people), and dentists (0.31 per 1,000 people). Access to "improved water sources" was limited to 92% of the population in urban areas and 80% of the population in rural areas. Some 99% of Algerians living in urban areas, but only 82% of those living in rural areas, had access to "improved sanitation". According to the World Bank, Algeria is making progress toward its goal of "reducing by half the number of people without sustainable access to improved drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015". Given Algeria's young population, policy favors preventive health care and clinics over hospitals. In keeping with this policy, the government maintains an immunization program. However, poor sanitation and unclean water still cause tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery. The poor generally receive health care free of charge.[139]

Health records have been maintained in Algeria since 1882 and began adding Muslims living in the South to their Vital record database in 1905 during French rule.[140]

Education

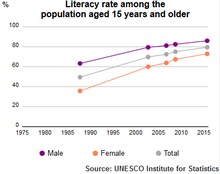

Since the 1970s, in a centralized system that was designed to significantly reduce the rate of illiteracy, the Algerian government introduced a decree by which school attendance became compulsory for all children aged between 6 and 15 years who have the ability to track their learning through the 20 facilities built since independence, now the literacy rate is around 78.7%.[141]

Since 1972, Arabic is used as the language of instruction during the first nine years of schooling. From the third year, French is taught and it is also the language of instruction for science classes. The students can also learn English, Italian, Spanish and German. In 2008, new programs at the elementary appeared, therefore the compulsory schooling does not start at the age of six anymore, but at the age of five.[142] Apart from the 122 private, learning at school, the Universities of the State are free of charge. After nine years of primary school, students can go to the high school or to an educational institution. The school offers two programs: general or technical. At the end of the third year of secondary school, students pass the exam of the bachelor's degree, which allows once it is successful to pursue graduate studies in universities and institutes.[143]

Education is officially compulsory for children between the ages of six and 15. In 2008, the illiteracy rate for people over 10 was 22.3%, 15.6% for men and 29.0% for women. The province with the lowest rate of illiteracy was Algiers Province at 11.6%, while the province with the highest rate was Djelfa Province at 35.5%.[141]

Algeria has 26 universities and 67 institutions of higher education, which must accommodate a million Algerians and 80,000 foreign students in 2008. The University of Algiers, founded in 1879, is the oldest, it offers education in various disciplines (law, medicine, science and letters). 25 of these universities and almost all of the institutions of higher education were founded after the independence of the country.

Even if some of them offer instruction in Arabic like areas of law and the economy, most of the other sectors as science and medicine continue to be provided in French and English. Among the most important universities, there are the University of Sciences and Technology Houari Boumediene, the University of Mentouri Constantine, University of Oran Es-Senia. The University of Abou Bekr Belkaïd in Tlemcen and University of Batna Hadj Lakhdar occupy the 26th and 45th row in Africa.[144]

See also

Template:Contains Tifinagh text

References

- ^ "Constitution of Algeria, Art. 11" (in Arabic). El-mouradia.dz. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Constitution of Algeria; Art. 11". Apn-dz.org. 28 November 1996. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Constitution of Algeria; Art. 3". Apn-dz.org. 28 November 1996. Archived from the original on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "APS" (PDF). Algeria Press Service. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "The World Factbook – Algeria". Central Intelligence Agency. 4 December 2013. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Démographie (ONS)". ONS. 19 January 2016. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Algeria. International Monetary Fund

- ^ Staff. "Distribution of Family Income – Gini Index". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "2015 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 14 December 2015. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (7 September 2009). "Could the UK drive on the right?". BBC News. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Country Comparison: Area". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Algeria buying military equipment". UPI.com. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- ^ "The Nuclear Vault: The Algerian Nuclear Problem". Gwu.edu. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "algeria". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ al-Idrisi, Muhammad (12th century) Nuzhat al-Mushtaq

- ^ Abderahman, Abderrahman (1377). History of Ibn Khaldun – Volume 6.

- ^ Sahnouni, Mohamed; de Heinzelin, Jean. "The Site of Ain Hanech Revisited: New Investigations at this Lower Pleistocene Site in Northern Algeria" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Research at Ain Hanech, Algeria". Stoneageinstitute.org. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Genomic Ancestry of North Africans Supports Back-to-Africa Migrations". PLOS Genetics. 12 January 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Brett, Michael; Fentress, Elizabeth (1997). "Berbers in Antiquity". The Berbers. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20767-2.

- ^ a b Cameron, Averil; Ward-Perkins, Bryan (2001). "Vandal Africa, 429–533". The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 14. Cambridge University Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-521-32591-2.

- ^ Mattingly, D.J. (1983). "The Laguatan: A Libyan Tribal Confederation in the late Roman Empire". Libyan Studies. 14.

- ^ "Fatimid Dynasty (Islamic dynasty)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ "Qantara". Qantara-med.org. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Qantara – Les Almoravides (1056–1147)". Qantara-med.org. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). p. XV.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). pp. X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "European Offensive". Country Studies.

- ^ Hayreddin Barbarossa#Rulers of Algiers

- ^ a b c d "Algeria – Ottoman Rule". Country Studies.

- ^ a b Robert Davis (2003). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780333719664.

- ^ "Barbary Pirates—Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b Robert Davis (17 February 2011). "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast". Bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (Spring 2007). "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". City Journal. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ Povoledo, Elisabetta (26 September 2003). "The Mysteries and Majesties of the Aeolian Islands". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ "Monte Sant'Angelo". centrovacanzeoriente.it. 22 July 2011. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "History of Menorca".

- ^ "When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed". Ohio State Research COmmunications. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Vísindavefurinn: Hverjir stóðu raunverulega að Tyrkjaráninu?". Vísindavefurinn.

- ^ "Vísindavefurinn: Hvað gerðist í Tyrkjaráninu?". Vísindavefurinn.

- ^ "Turkish invasion walk". heimaslod.is.

- ^ Etravel Travel service. "Turkish Invasion – Visit Westman Islands .com" Archived 6 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. visitwestmanislands.com.

- ^ "Vísindavefurinn: Voru Tyrkjarán framin í öðrum löndum?". Vísindavefurinn.

- ^ Mackie, Erin Skye (1 January 2005). "Welcome the Outlaw: Pirates, Maroons, and Caribbean Countercultures". Cultural Critique. 59 (1): 24–62. doi:10.1353/cul.2005.0008.

- ^ "Barbary Pirates – Encyclopædia Britannica".

- ^ Littell, Eliakim (1836). The Museum of foreign literature, science and art. E. Littell. p. 231.

- ^ "Background Note: Algeria". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barbary Pirates". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Ricoux, René (1880). La démographie figurée de l'Algérie: étude statistique des... G. Masson. pp. 260–261. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Lahmeyer, Jan (11 October 2003). "Algeria (Djazaïria) historical demographic data of the whole country". Population Statistics. populstat.info. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ^ Ruedy, John Douglas (2005). Modern Algeria: The Origins And Development of a Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-253-21782-0.

- ^ Hargreaves, Alec G.; McKinney, Mark (1997). Post-Colonial Cultures in France. Psychology Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-415-14487-2.

- ^ Randell, Keith (1986). France: Monarchy, Republic and Empire, 1814–70. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-51805-2.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York Review Books Classics). 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Albert Habib Hourani, Malise Ruthven (2002). "A history of the Arab peoples". Harvard University Press. p.323. ISBN 0-674-01017-5

- ^ Baten, Jörg (2016). A History of the Global Economy. From 1500 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 9781107507180.

- ^ "French 'Reparation' for Algerians". BBC News. 6 December 2007.

- ^ Memory and Violence in the Middle East and North Africa By Ussama Samir Makdisi, Paul A. Silverstein, Published 2006 by Indiana University Press, ISBN 0253217989 page 160.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Country Profile: Algeria". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Prochaska, David. "That Was Then, This Is Now: The Battle of Algiers and After". p. 141. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "98 Die in One of Algerian Civil War's Worst Massacres ". The New York Times. 30 August 1997.

- ^ "Freedom House". "Freedom in the World 2013: Algeria". Freedom House.

- ^ "Algeria Officially Lifts State of Emergency". CNN. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Algeria". African Economic Outlook.

- ^ a b Metz, Helen Chapin. "Algeria : a country study". United States Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Crocodiles in the Sahara Desert: An Update of Distribution, Habitats and Population Status for Conservation Planning in Mauritania". PLOS ONE. 25 February 2011.

- ^ "Still waiting for real democracy". The Economist. 12 May 2012.

- ^ "The president and the police". The Economist. 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Algeria Deputies Scrap Term Limit". BBC News. 12 November 2008. Archived from the original on 14 November 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Articles: 85, 87, 77, 78 and 79 of the Algerian constitution Algerian government. "Constitution". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ a b c "Algeria". Freedom in the World 2013. Freedom House. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Article 42 of the Algerian constitution – Algerian Government. "Algerian constitution الحـقــوق والحــرّيـات". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ "Bin Ali calls for reactivating Arab Maghreb Union, Tunisia-Maghreb, Politics". ArabicNews.com. 19 February 1999. Archived from the original on 25 November 2001. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/france-offers-compensation-to-victims-sickened-by-nuclear-tests-1.797730

- ^ Hackett, James (ed.) (5 February 2008). The Military Balance 2008. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Europa. ISBN 978-1-85743-461-3. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Loi 14-06 relative au service national", JORADP 48, August, 10th 2014

- ^ "Venezuela's Chavez To Finalise Russian Submarines Deal". Agence France-Presse. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "World Bank list of economies". World Bank. January 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Algeria: Financial Sector Profile". Making Finance Work for Africa. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "Algeria Non-Oil Exports Surge 41%". nuqudy.com. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ a b c "Algeria: 2011 Article IV Consultation" (PDF). IMF.

- ^ "Doing Business in Algeria". Embassy of the United States Algiers, Algeria.

- ^ "Brtsis, Brief on Russian Defence, Trade, Security and Energy". Brtsis.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ "Russia Agrees Algeria Arms Deal, Writes Off Debt". Reuters. 11 March 2006.

- ^ Marsaud, Olivia (10 March 2006). "La Russie efface la dette algérienne" (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dubai-based firm forms $1.6 billion steel plant joint venture in Algeria".

- ^ "OPEC Bulletin 8-9/12". p. 15.

- ^ "Country Comparison: Natural Gas – Proved Reserves". Cia.gov. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ Benchicou, Mohamed (27 May 2013). "Le temps des crapules – Tout sur l'Algérie". Tsa-algerie.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Country Analysis Briefs – Algeria" (PDF). Energy Information Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://portail.cder.dz/spip.php?article1571

- ^ UNESCO. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Kamel Kateb (2001). Européens, "indigènes" et juifs en Algérie (1830–1962). INED. p. 30. ISBN 978-2-7332-0145-9.

- ^ "Armature Urbaine" (PDF). V° Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat – 2008. Office National des Statistiques. September 2011. p. 82.

- ^ "Algérie a atteint 40,4 millions d'habitants (ONS)". ons. 17 April 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.