Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisbarrig | |

|---|---|

| City of Harrisburg | |

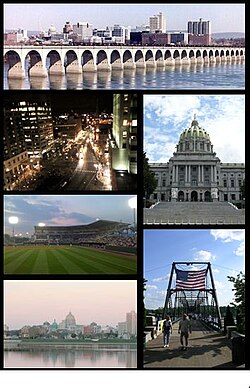

From top to bottom, left to right: Harrisburg skyline; Market Square in Downtown Harrisburg; Pennsylvania State Capitol; FNB Field; Walnut Street Bridge; Susquehanna River | |

| Nickname: "Pennsylvania's Capital City" | |

| Motto: "En la rou Justita" | |

Location of Harrisburg in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. | |

| Coordinates: 40°16′11″N 76°52′32″W / 40.26972°N 76.87556°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Dauphin |

| European settlement | About 1719 |

| Incorporated | 1791 |

| Charter | March 19, 1860 |

| Founded by | John Harris, Sr. |

| Named for | John Harris, Sr. |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-Council |

| • Mayor | Eric Papenfuse (D) |

| • City Controller | Charlie DeBrunner (D) |

| • City Council | |

| • State Senate | John DiSanto (R) |

| • State Representative | Patty Kim (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 11.86 sq mi (30.73 km2) |

| • Land | 8.12 sq mi (21.03 km2) |

| • Water | 3.75 sq mi (9.70 km2) |

| • Urban | 259.7 sq mi (672.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 320 ft (98 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 49,528 |

| • Density | 6,068.60/sq mi (2,343.10/km2) |

| • Urban | 444,474 (86th) |

| • Metro | 577,941 (98th) |

| • CSA | 1,271,801(46th) |

| Demonym(s) | Harrisburger, Harrisburgian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 17101-17113, 17120-17130, 17140, 17177 |

| Area code | 717 and 223 |

| FIPS code | 42-32800[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1213649[4]

|

| Interstates | I-76, I-78, I-81, I-83 and I-283 |

| Waterways | Susquehanna River |

| Primary Airport | Harrisburg International Airport- MDT (Major/International) |

| Secondary Airport | Capital City Airport- CXY (Minor) |

| Public transit | Capital Area Transit |

| Website | www.harrisburgpa.gov |

| Designated | September 23, 1946[5] |

Harrisburg (/ˈhærɪsbɜːrɡ/ HARR-iss-burg; Pennsylvania German: Harrisbarrig)[citation needed] is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 49,271, it is the 13th largest city in the Commonwealth. According to 2018 estimates of the Census Bureau,[6] the population is 51.8% Black or African American, 22.6% White, 21.8% Latino, 5.4% Asian, and 0.4% Native American while 3.9% identify as two or more races. It lies on the east bank of the Susquehanna River, 107 miles (172 km) west of Philadelphia. Harrisburg is the anchor of the Harrisburg metropolitan area, which had a 2019 estimated population of 577,941,[7] making it the fourth most populous metropolitan area in Pennsylvania and 96th most populous in the United States. It is the second-largest city in the multi-polar region known as the Lower Susquehanna Valley, comprising the Harrisburg, Lancaster and York metropolitan areas.

Harrisburg played a notable role in American history during the Westward Migration, the American Civil War and the Industrial Revolution. During part of the 19th century, the building of the Pennsylvania Canal, and later the Pennsylvania Railroad, allowed Harrisburg to become one of the most industrialized cities in the Northeastern United States. The U.S. Navy ship USS Harrisburg, which served from 1918 to 1919 at the end of World War I, was named in honor of the city. In the mid-to-late 20th century, the city's economic fortunes fluctuated with its major industries consisting of government, heavy manufacturing, agriculture, and food services (nearby Hershey is home of the chocolate maker, located just 10 miles (16 km) east).

The Pennsylvania Farm Show, the largest free indoor agriculture exposition in the United States, was first held in Harrisburg in 1917 and has been held there every early-to-mid January since then.[8] Harrisburg also hosts an annual outdoor sports show, the largest of its kind in North America, an auto show, which features a large static display of new as well as classic cars and is renowned nationwide, and Motorama, a two-day event consisting of a car show, motocross racing, remote control car racing, and more. Harrisburg is also known for the Three Mile Island accident, which occurred on March 28, 1979, near Middletown.

In 2010 Forbes rated Harrisburg as the second best place in the U.S. to raise a family.[9] Despite the city's recent financial troubles, in 2010 The Daily Beast website ranked 20 metropolitan areas across the country as being recession-proof, and the Harrisburg region landed at No. 7.[10] The financial stability of the region is in part due to the high concentration of state and federal government agencies.

History

Founding

Harrisburg's site along the Susquehanna River is thought to have been inhabited by Native Americans as early as 3000 BC. Known to the Native Americans as "Peixtin", or "Paxtang", the area was an important resting place and crossroads for Native American traders, as the trails leading from the Delaware to the Ohio rivers, and from the Potomac to the Upper Susquehanna intersected there. The first European contact with Native Americans in Pennsylvania was made by the Englishman, Captain John Smith, who journeyed from Virginia up the Susquehanna River in 1608 and visited with the Susquehanna tribe. In 1719, John Harris, Sr., an English trader, settled here and 14 years later secured grants of 800 acres (3.2 km2) in this vicinity. In 1785, John Harris, Jr. made plans to lay out a town on his father's land, which he named Harrisburg. In the spring of 1785, the town was formally surveyed by William Maclay, who was a son-in-law of John Harris, Sr. In 1791, Harrisburg became incorporated, and in October 1812 it was named the Pennsylvania state capital, which it has remained ever since. The assembling here of the highly sectional Harrisburg Convention in 1827 (signaling what may have been the birth of lobbying on a national scale) led to the passage of the high protective-tariff bill of 1828.[11] In 1839, William Henry Harrison and John Tyler were nominated for president and vice president of the United States at the first national convention of the Whig Party of the United States, which was held in Harrisburg.

Pre-industry: 1800–1850

Before Harrisburg gained its first industries, it was a scenic, pastoral town, typical of most of the day: compact and surrounded by farmland. In 1822, the impressive brick capitol was completed for $200,000.[12]

It was Harrisburg's strategic location which gave it an advantage over many other towns. It was settled as a trading post in 1719 at a location important to Westward expansion. The importance of the location was that it was at a pass in a mountain ridge. The Susquehanna River flowed generally west to east at this location, providing a route for boat traffic from the east. The head of navigation was a short distance northwest of the town, where the river flowed through the pass. Persons arriving from the east by boat had to exit at Harrisburg and prepare for an overland journey westward through the mountain pass. Harrisburg assumed importance as a provisioning stop at this point where westward bound pioneers transitioned from river travel to overland travel. It was partly because of its strategic location that the state legislature selected the small town of Harrisburg to become the state capital in 1812.

The grandeur of the Colonial Revival capitol dominated the quaint town. The streets were dirt, but orderly and platted in grid pattern. The Pennsylvania Canal was built in 1834 and coursed the length of the town. The residential houses were situated on only a few city blocks stretching southward from the capitol. They were mostly one story. No factories were present but there were blacksmith shops and other businesses.[13]

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, Harrisburg was a significant training center for the Union Army, with tens of thousands of troops passing through Camp Curtin. It was also a major rail center for the Union and a vital link between the Atlantic coast and the Midwest, with several railroads running through the city and spanning the Susquehanna River. As a result of this importance, it was a target of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia during its two invasions. The first time during the 1862 Maryland Campaign, when Lee planned to capture the city after taking Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, but was prevented from doing so by the Battle of Antietam and his subsequent retreat back into Virginia. The second attempt was made during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863 and was more substantial. The Skirmish of Sporting Hill took place in June 1863 in Camp Hill, just 2 miles (3 km) west of Harrisburg.

During the first part of the 19th century, Harrisburg was a notable stopping place along the Underground Railroad, as escaped slaves being transported across the Susquehanna River were often fed and supplied before heading north towards Canada.[14]

On July 3, 1863, the artillery barrage that marked the beginning of Pickett's Charge of the Battle of Gettysburg was heard from Harrisburg, almost 40 miles away.[15]

Industrial rise: 1850–1920

Harrisburg's importance in the latter half of the 19th century was in the steel industry. It was an important railroad center as well. Steel and iron became dominant industries. Steel and other industries continued to play a major role in the local economy throughout the latter part of the 19th century. The city was the center of enormous railroad traffic and its steel industry supported large furnaces, rolling mills, and machine shops. The Pennsylvania Steel Company plant, which opened in nearby Steelton in 1866, was the first in the country; later operated by Bethlehem Steel.[16]

Its first large scale iron foundries were put into operation shortly after 1850.[13] As industries nationwide entered a phase of great expansion and technological improvement, so did industries – and in particular the steel industry – in Harrisburg. This can be attributed to a combination of factors that were typical of what existed in other successful industrial cities: rapid rail expansion; nearby markets for goods; and nearby sources for raw product. With Harrisburg poised for growth in steel production, the Borough of Steelton became the ideal location for this type of industry. It was a wide swath of flat land located south of the city, with rail and canal access running its entire 4 mile length. There was plenty of room for houses and its own downtown section. Steelton was a company town, opened in 1866 by the Pennsylvania Steel Company. Highly innovative in its steel making process, it became the first mill in the United States to make steel railroad rails by contract. In its heyday Steelton was home to more than 16,000 residents from 33 different ethnic groups. All were employed in the steel industry, or had employment in services that supported it. In the late 19th century, no less than five major steel mills and foundries were located in Steelton. Each contained a maze of buildings; conveyances for moving the products; large yards for laying down equipment; and facilities for loading their product on trains. Stacks from these factories constantly belched smoke. With housing and a small downtown area within walking distance, these were the sights and smells that most Steelton residents saw every day.

The rail yard was another area of Harrisburg that saw rapid and thorough change during the years of industrialization. This was a wide expanse of about two dozen railroad tracks that grew from the single track of the early 1850s. By the late 19th century, this area was the width of about two city blocks and formed what amounted to a barrier along the eastern edge of the city: passable only by bridge. Three large and ornately embellished passenger depots were built by as many rail lines. Pennsylvania Railroad was the largest rail line in Harrisburg. It built huge repair facilities and two large roundhouses in the 1860s and 1870s to handle its enormous freight and passenger traffic and to maintain its colossal infrastructure. Its rails ran the length of Harrisburg, along its eastern border. It had a succession of three passenger depots, each built on the site of the predecessor, and each of high style architecture, including a train shed to protect passengers from inclement weather. At its peak in 1904, it made 100 passenger stops per day. It extended westward to Pittsburgh; across the entire state. It also went eastward to Philadelphia, serving Steelton en route. The vital anthracite coal mines in the Allegheny Mountains were reached by the Northern Central Railroad. The Lebanon Valley Railroad extended eastward to Philadelphia with spurs to New York City. Another rail line was the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad which provided service to Philadelphia and other points east.[17]

Industrial decline: 1920–1970

The decades between 1920 and 1970 were characterized by industrial decline and population shift from the city to the suburbs. Like most other cities which faced a loss of their industrial base, Harrisburg shifted to a service-oriented base, with industries such as health care and convention centers playing a big role. Harrisburg's greatest problem was a shrinking city population after 1950. This loss in population followed a national trend and was a delayed result of the decline of Harrisburg's steel industry. This decline began almost imperceptibly in the late 1880s, but did not become evident until the early 20th century.

After being held in place for about 5 years by WWII armament production, the population peaked shortly after the war, but then took a long-overdue dive as people fled from the city. Hastening the flight to the suburbs were the cheap and available houses being built away from the crime and deteriorating situation of the city. The reduction in city population coincided with the rise in population of the Metropolitan Statistical Area. The trend continued until the 1990s.[18]

Beginning of Harrisburg's suburbs: 1980s

The gradual loss of industry, especially after WWII, coupled with the proliferation of the street car and later the automobile, led to white flight to the suburbs. Allison Hill was Harrisburg's first suburb. It was located east of the city on a prominent bluff, accessed by bridges across a wide swath of train tracks. It was developed in the late 19th century and offered affluent Harrisburgers the opportunity to live in the suburbs only a few hundred yards from their jobs in the City. Easy access was achieved via the State Street Bridge leading east from the Capitol complex and the Market Street Bridge leading from the City's prominent business district. In 1886 a single horse trolley line was established from the city to Allison Hill. The most desirable section of Allison Hill was Mount Pleasant, which was characterized by large Colonial Revival style houses with yards for the very wealthy and smaller but still well-built row houses lining the main street for the moderately wealthy. State Street, leading from the Capitol directly toward Allison Hill, was planned to provide a grand view of the Capitol dome for those approaching the City from Allison Hill. This trend towards outlying residential areas began slowly in the late 19th century and was largely confined to the trolley line, but the growth of automobile ownership quickened the trend and spread out the population.

20th century

In the early 20th century, the city of Harrisburg was in need of change. Without proper sanitation, diseases such as typhoid began killing many citizens of Harrisburg. Seeing these necessary changes, several Harrisburg residents became involved in the City Beautiful movement. Mira Lloyd Dock spearheaded the movement with an impressive speech before the city's Board of Trade. Other prominent citizens of the city such as J. Horace McFarland and Vance McCormick advocated urban improvements which were influenced by European urban planning design and the World's Columbian Exposition. Warren Manning was hired to help bring about these changes. Specifically, their efforts greatly enlarged the Harrisburg park system, creating Riverfront Park, Reservoir Park, the Italian Lake and Wildwood Park. In addition, schemes were undertaken for the burial of electric wires, the creation of a modern sanitary sewer system, and the beautification of an expanded Capitol complex.

The Pennsylvania Farm Show, the largest indoor agriculture exposition in the United States, was first held in 1917 and has been held every January since then. The present location of the Show is the Pennsylvania State Farm Show Arena, located at the corner of Maclay and Cameron streets.

In June 1972, Harrisburg was hit by a major flood from the remnants of hurricane Agnes.

On March 28, 1979, the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, along the Susquehanna River located in Londonderry Township which is south of Harrisburg, suffered a partial meltdown. Although the meltdown was contained and radiation leakages were minimal, there were still worries that an evacuation would be necessary. Governor Dick Thornburgh, on the advice of Nuclear Regulatory Commission Chairman Joseph Hendrie, advised the evacuation "of pregnant women and pre-school age children ... within a five-mile radius of the Three Mile Island facility." Within days, 140,000 people had left the area.[19]

Stephen R. Reed was elected mayor in 1981 and served until 2009, making him the city's longest-serving mayor. In an effort to end the city's long period of economic troubles, he initiated several projects to attract new business and tourism to the city. Several museums and hotels such as Whitaker Center for Science and the Arts, the National Civil War Museum and the Hilton Harrisburg and Towers were built during his term, along with many office buildings and residential structures. Several minor league professional sports franchises, including the Harrisburg Senators of the Eastern League, the Harrisburg Heat indoor soccer club, and Penn FC of the United Soccer League began operations in the city during his tenure as mayor. While praised for the vast number of economic improvements, Reed has also been criticized for population loss and mounting debt. For example, during a budget crisis the city was forced to sell $8 million worth of Western and American-Indian artifacts collected by Mayor Reed for a never-realized museum celebrating the American West.[20]

21st century: fiscal difficulties and receivership

During the nearly 30-year tenure of former Mayor Stephen Reed from 1981 to 2009, city officials ignored legal restraints on the use of bond proceeds, as Reed spent the money pursuing interests including collecting Civil War and Wild West memorabilia—some of which was found in Reed's home after his arrest on corruption charges.[21] Infrastructure was left unrepaired, and the heart of the city's financial woes was a trash-to-electricity plant, the Harrisburg incinerator, which was supposed to generate income but instead, because of increased borrowing, incurred a debt of $320 million.[22]

Missing audits and convoluted transactions, including swap agreements, make it difficult to state how much debt the city owes. Some estimates put total debt over $1.5 billion, which would mean that every resident would owe $30,285.[23] These numbers do not reflect the school system deficit, the school district's $437 million long-term debt,[24] nor unfunded pension and healthcare obligations.

Harrisburg was the first municipality ever in the history of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to be charged with securities fraud, for misleading statements about its financial health.[25] The city agreed to a plea bargain to settle the case.[26]

In October 2011, Harrisburg filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy when four members of the seven-member City Council voted to file a bankruptcy petition in order to prevent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania from taking over the city's finances.[27][28][29] Bankruptcy Judge Mary France dismissed the petition on the grounds that the City Council majority had filed it over the objection of Mayor Linda Thompson, reasoning that the filing not only required the mayor's approval but had circumvented state laws concerning financially distressed cities.[30]

Instead, a state-appointed receiver took charge of the city's finances.[31] Governor Tom Corbett appointed bond attorney David Unkovic as the city's receiver, but Unkovic resigned after only four months.[32] Unkovic blamed disdain for legal restraints on contracts and debt for creating Harrisburg's intractable financial problem and said the corrupt influence of creditors and political cronies prevented fixing it.[32][33]

As creditors began to file lawsuits to seize and sell off city assets, a new receiver, William B. Lynch, was appointed.[34] The City Council opposed the new receiver's plans for tax increases and advocated a stay of the creditor lawsuits with a bankruptcy filing, while Mayor Thompson continued to oppose bankruptcy.[35] State legislators crafted a moratorium to prevent Harrisburg from declaring bankruptcy, and after the moratorium expired, the law stripped the city government of the authority to file for bankruptcy and conferred it on the state receiver.[36][37] [38]

After two years of negotiations, in August 2013 Receiver Lynch revealed his comprehensive voluntary plan for resolving Harrisburg's fiscal problems.[39] The complex plan calls for creditors to write down or postpone some debt.[40] To pay the remainder, Harrisburg will sell the troubled incinerator, lease for forty years its parking garages, and go further into debt by issuing new bonds.[39][40] Receiver Lynch has also called for setting up nonprofit investment corporations to oversee infrastructure improvement (repairing the city's crumbling roads and water and sewer lines), pensions, and economic development.[41] These are intended to allow nonprofit fundraising and to reduce the likelihood of mismanagement by the dysfunctional city government.[40][41]

Harrisburg's City Council and the state Commonwealth Court approved the plan, and it is in the process of being implemented. [42][43][44][45]

Geography

Topography

Harrisburg is located at 40°16′11″N 76°52′32″W / 40.26972°N 76.87556°W (40.269789, -76.875613) in South Central Pennsylvania,[46] within a four-hour drive of the metro areas of New York, Washington, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 11.4 square miles (30 km2), of which, 8.1 square miles (21 km2) of it is land and 3.3 square miles (8.5 km2) of it (29.11%) is water. Bodies of water include Paxton Creek which empties into the Susquehanna River at Harrisburg, as well as Wildwood Lake and Italian Lake parks.

Directly to the north of Harrisburg is the Blue Mountain ridge of the Appalachian Mountains. The Cumberland Valley lies directly to the west of Harrisburg and the Susquehanna River, stretching into northern Maryland. The fertile Lebanon Valley lies to the east. Harrisburg is the northern fringe of the historic Pennsylvania Dutch Country.

The city is the county seat of Dauphin County. The adjacent counties are Northumberland County to the north; Schuylkill County to the northeast; Lebanon County to the east; Lancaster County to the south; and York County to the southwest; Cumberland County to the west; and Perry County to the northwest.

Adjacent municipalities

Harrisburg's western boundary is formed by the west shore of the Susquehanna River (the Susquehanna runs within the city boundaries), which also serves as the boundary between Dauphin and Cumberland counties. The city is divided into numerous neighborhoods and districts. Like many of Pennsylvania's cities and boroughs that are at "build-out" stage, there are several townships outside of Harrisburg city limits that, although autonomous, use the name Harrisburg for postal and name-place designation. They include the townships of: Lower Paxton, Middle Paxton, Susquehanna, Swatara and West Hanover in Dauphin County. The borough of Penbrook, located just east of Reservoir Park, was previously known as East Harrisburg. Penbrook, along with the borough of Paxtang, also located just outside the city limits, maintain Harrisburg zip codes as well. The United States Postal Service designates 26 zip codes for Harrisburg, including 13 for official use by federal and state government agencies.[47]

|

|

Climate

Harrisburg has a variable, four-season climate lying at the beginning of the transition between the humid subtropical and humid continental zones (Köppen Cfa and Dfa, respectively). The hottest month of the year is July with a daily mean temperature of 75.9 °F (24.4 °C).[48] Summer is usually hot and humid and occasional heat waves can occur. The city averages around 21 days per year with 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs although temperatures reaching 100 °F (38 °C) are rare. The hottest temperature ever recorded in Harrisburg is 107 °F (42 °C) on July 3, 1966.[48] Summer thunderstorms also occur relatively frequently. Autumn is a pleasant season when the humidity and temperatures fall to more comfortable values. The hardiness zone is 7a.

Winter in Harrisburg is rather cold: January, the coldest month, has a daily mean temperature of 29.9 °F (−1.2 °C).[48] A major snowstorm can also occasionally occur, and some winters snowfall totals can exceed 60 inches (152 cm) while in other winters the region may receive very little snowfall. The largest snowfall on a single calendar day was 26.4 in (67 cm) on January 23, 2016,[48] recorded at Harrisburg International Airport in Middletown, while the snowiest month on record was February 2010 with 42.1 in (107 cm), recorded at the same location.[49] Overall Harrisburg receives an average of 30.6 in (77.7 cm) of snow per winter.[48] The coldest temperature ever recorded in Harrisburg was −22 °F (−30 °C) on January 21, 1994.[48] Spring is also a nice time of year for outdoor activities. Precipitation is well-distributed and generous in most months, though July is clearly the wettest and February the driest.

| Climate data for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (Harrisburg Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1888–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

79 (26) |

87 (31) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

107 (42) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

97 (36) |

84 (29) |

75 (24) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 59.3 (15.2) |

61.4 (16.3) |

72.7 (22.6) |

83.5 (28.6) |

89.5 (31.9) |

93.3 (34.1) |

96.2 (35.7) |

93.8 (34.3) |

89.7 (32.1) |

81.1 (27.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

62.3 (16.8) |

97.0 (36.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 38.6 (3.7) |

42.0 (5.6) |

51.3 (10.7) |

63.8 (17.7) |

73.7 (23.2) |

82.4 (28.0) |

86.8 (30.4) |

84.7 (29.3) |

77.6 (25.3) |

65.7 (18.7) |

53.9 (12.2) |

43.3 (6.3) |

63.6 (17.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.8 (−0.7) |

33.4 (0.8) |

41.8 (5.4) |

53.2 (11.8) |

63.4 (17.4) |

72.5 (22.5) |

77.3 (25.2) |

75.2 (24.0) |

67.9 (19.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

44.8 (7.1) |

35.8 (2.1) |

54.3 (12.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.0 (−5.0) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

32.3 (0.2) |

42.5 (5.8) |

53.1 (11.7) |

62.7 (17.1) |

67.8 (19.9) |

65.8 (18.8) |

58.2 (14.6) |

46.0 (7.8) |

35.8 (2.1) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

45.0 (7.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 7.4 (−13.7) |

10.1 (−12.2) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

29.2 (−1.6) |

39.6 (4.2) |

50.8 (10.4) |

58.3 (14.6) |

55.8 (13.2) |

45.2 (7.3) |

33.0 (0.6) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

14.6 (−9.7) |

5.0 (−15.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −22 (−30) |

−13 (−25) |

−1 (−18) |

11 (−12) |

30 (−1) |

40 (4) |

49 (9) |

45 (7) |

30 (−1) |

23 (−5) |

10 (−12) |

−8 (−22) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.03 (77) |

2.59 (66) |

3.70 (94) |

3.55 (90) |

3.83 (97) |

3.98 (101) |

4.74 (120) |

3.77 (96) |

4.83 (123) |

3.81 (97) |

2.97 (75) |

3.43 (87) |

44.23 (1,123) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.1 (23) |

9.4 (24) |

5.6 (14) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.8 (2.0) |

4.4 (11) |

29.9 (76) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 5.3 (13) |

5.1 (13) |

4.0 (10) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.3 (0.76) |

2.4 (6.1) |

9.8 (25) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.9 | 10.4 | 11.0 | 11.4 | 13.0 | 11.5 | 10.9 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 10.3 | 126.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 5.1 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.7 | 16.3 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[51][52] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV data)[53] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Neighborhoods

Center City Harrisburg, which includes the Pennsylvania State Capitol Complex, is the central core business and financial center for the greater Harrisburg metropolitan area and serves as the seat of government for Dauphin County and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. There are over a dozen large neighborhoods and historic districts within the city.

Architecture

Harrisburg is home to the Pennsylvania State Capitol. Completed in 1906, the central dome rises to a height of 272 feet (83 m) and was modeled on that of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, Rome. The building was designed by Joseph Miller Huston and is adorned with sculpture, most notably the two groups, Love and Labor, the Unbroken Law and The Burden of Life, the Broken Law by sculptor George Grey Barnard; murals by Violet Oakley and Edwin Austin Abbey; tile floor by Henry Mercer, which tells the story of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The state capitol is only the third-tallest building of Harrisburg. The five tallest buildings are 333 Market Street with a height of 341 feet (104 m), Pennsylvania Place with a height of 291 feet (89 m), the Pennsylvania State Capitol with a height of 272 feet (83 m), Presbyterian Apartments with a height of 259 feet (79 m) and the Fulton Bank Building with a height of 255 feet (78 m).[54]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 875 | — | |

| 1800 | 1,472 | 68.2% | |

| 1810 | 2,287 | 55.4% | |

| 1820 | 2,990 | 30.7% | |

| 1830 | 4,312 | 44.2% | |

| 1840 | 5,980 | 38.7% | |

| 1850 | 7,834 | 31.0% | |

| 1860 | 13,405 | 71.1% | |

| 1870 | 23,104 | 72.4% | |

| 1880 | 30,762 | 33.1% | |

| 1890 | 39,385 | 28.0% | |

| 1900 | 50,167 | 27.4% | |

| 1910 | 64,186 | 27.9% | |

| 1920 | 75,917 | 18.3% | |

| 1930 | 80,339 | 5.8% | |

| 1940 | 83,893 | 4.4% | |

| 1950 | 89,544 | 6.7% | |

| 1960 | 79,697 | −11.0% | |

| 1970 | 68,061 | −14.6% | |

| 1980 | 53,264 | −21.7% | |

| 1990 | 52,376 | −1.7% | |

| 2000 | 48,950 | −6.5% | |

| 2010 | 49,528 | 1.2% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 49,271 | [55] | −0.5% |

| United States Census Bureau[56][57] | |||

As of the 2010 census, the city was 52.4% Black or African American, 30.7% White, 3.5% Asian, 0.5% Native American, 0.1% Native Hawaiian, and 5.2% were two or more races. 18.0% of the population were of Hispanic or Latino ancestry.

The six largest ethnic groups in the city are: African American (52.4%), German (15.0%), Irish (6.5%), Italian (3.3%), English (2.4%), and Dutch (1.0%). While the metropolitan area is approximately 15% German-American, 11.4% are Irish-American and 9.6% English-American. Harrisburg has one of the largest Pennsylvania Dutch communities in the nation, and also has the nation's ninth-largest Swedish-American communities in the nation.

There were 20,561 households, out of which 28.5% had children under the age of 13 living with them, 23.4% were married couples living together, 24.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 46.9% were non-families. 39.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.32 and the average family size was 3.15.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 28.2% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 13 to 24, 31.0% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 10.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.7 males. For every 100 females age 13 and over, there were 84.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,920, and the median income for a family was $29,556. Males had a median income of $90,670 versus $24,405 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,787. About 23.4% of families and 24.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 34.9% of those under age 13 and 16.6% of those age 65 or over.

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2020) |

The very first census taken in the United States occurred in 1790. At that time Harrisburg was a small, but substantial colonial town with a population of 875 residents.[58] With the increase of the city's prominence as an industrial and transportation center, Harrisburg reached its peak population build up in 1950, topping out at nearly 90,000 residents. Since the 1950s, Harrisburg, along with other northeastern urban centers large and small, has experienced a declining population that is ultimately fueling the growth of its suburbs, although the decline – which was very rapid in the 1960s and 1970s – has slowed considerably since the 1980s.[59] Unlike Western and Southern states, Pennsylvania maintains a complex system of municipalities and has very little legislation on either the annexation/expansion of cities or the consolidating of municipal entities.

Reversing fifty years of decline, 2004 Census Bureau estimates show that Harrisburg's population has actually grown. Between 2004 and 2006, Harrisburg gained 22 people. In 2006, the urban population of the Harrisburg area increased to 383,008 from 362,782 in 2000, a change of 20,226 people.[60] In 2004 the Harrisburg area was listed with Lebanon and York as an urban agglomeration, or a contiguous area of continuously developed urban land,[61] signifying a future merger of the York-Hanover and Harrisburg metropolitan areas, which would create a metropolitan area of over 1 million.

Economy

Harrisburg is the metropolitan center for some 400 communities.[62] Its economy and more than 45,000 businesses are diversified with a large representation of service-related industries, especially health-care and a growing technological and biotechnology industry to accompany the dominant government field inherent to being the state's capital. National and international firms with major operations include Ahold Delhaize USA, Arcelor Mittal Steel, HP, IBM, Hershey Foods, Harsco Corporation, Ollie's Bargain Outlet, Rite Aid Corporation, Tyco Electronics, and Volvo Heavy Machinery.[63] The largest employers, the federal and state governments, provide stability to the economy. The region's extensive transportation infrastructure has allowed it to become a prominent center for trade, warehousing, and distribution.[62]

Employers

Top 10

According to the Region Economic Development Corporation, the top employers in the region are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania | 21,885 | Government |

| 2 | United States Federal government, including the military | 18,000 | Government |

| 3 | Giant Food Stores | 8,902 | Grocery store |

| 4 | Penn State Hershey Medical Center | 8,849 | Hospital, Medical research |

| 5 | Hershey Entertainment and Resorts, including Hersheypark | 7,500 | Entertainment and amusement parks |

| 6 | The Hershey Company | 6,500 | Food manufacturer |

| 7 | Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. | 6,090 | Retail store chain |

| 8 | Highmark | 5,200 | Health insurance |

| 9 | TE Connectivity | 4,700 | Electronic component manufacturer |

| 10 | UPMC Pinnacle, including Harrisburg Hospital and Polyclinic Medical Center | 3,997 | Health-care and hospital system |

People and culture

Culture

In the mid-20th century, Harrisburg was home to many nightclubs and other performance venues, including the Madrid Ballroom, the Coliseum, the Chestnut Street Hall and the Hi-Hat. These venues featured performances from Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Fletcher Henderson and Andy Kirk, among other jazz greats. Segregationist policy forbade these musicians from staying overnight in downtown Harrisburg, however, making the Jackson Hotel in Harrisburg's 7th Ward a hub of black musicians prior the 1960s.[64]

Several organizations support and develop visual arts in Harrisburg. The Art Association of Harrisburg was founded in 1926 and continues to provide education and exhibits throughout the year. Additionally, the Susquehanna Art Museum, founded in 1989, offers classes, exhibits and community events. A local urban sketching group, Harrisburg Sketchers, convenes artists monthly.[65]

Downtown Harrisburg has two major performance centers. The Whitaker Center for Science and the Arts, which was completed in 1999, is the first center of its type in the United States where education, science and the performing arts take place under one roof. The Forum, a 1,763-seat concert and lecture hall built in 1930-31, is a state-owned and operated facility located within the State Capitol Complex. Since 1931, The Forum has been home to the Harrisburg Symphony Orchestra.

Beginning in 2001, downtown Harrisburg saw a resurgence of commercial nightlife development. This has been credited with reversing the city's financial decline, and has made downtown Harrisburg a destination for events from jazz festivals to Top-40 nightclubs.

Harrisburg is also the home of the annual Pennsylvania Farm Show, the largest agricultural exhibition of its kind in the nation. Farmers from all over Pennsylvania come to show their animals and participate in competitions. Livestock are on display for people to interact with and view. In 2004, Harrisburg hosted CowParade, an international public art exhibit that has been featured in major cities all over the world. Fiberglass sculptures of cows are decorated by local artists, and distributed over the city center, in public places such as train stations and parks. They often feature artwork and designs specific to local culture, as well as city life and other relevant themes.

Media

Harrisburg area is part of the Harrisburg-Lancaster-Lebanon-York media market which consists of the lower counties in south central Pennsylvania and borders the media markets of Philadelphia and Baltimore. It is the 43rd largest media market in the United States.[66]

The Harrisburg area has several newspapers. The Patriot-News, which is published in Cumberland County, serves the Harrisburg area and has a tri-weekly circulation of over 100,000. The Sentinel, which is published in Carlisle, roughly 20 miles west of Harrisburg, serves many of Harrisburg's western suburbs in Cumberland County. The Press and Journal, published in Middletown, is one of many weekly general information newspapers in the Harrisburg area. Harrisburg has several monthly community newspapers, including MODE Magazine (publishing since 1996), Urban Connection, and TheBurg. There are also numerous television and radio stations in the Harrisburg/Lancaster/York area. Only one non-municipal portal website exists for the city of Harrisburg, HarrisburgPA.com.

Newspapers

- The Patriot-News

- Central Penn Business Journal

- Press and Journal (Pennsylvania)

- Carlisle Sentinel

- MODE Magazine (alt newspaper)[67]

- Urban Connection (community paper)[68]

- TheBurg (community newspaper)[69]

- Harrisburg Magazine (monthly city/regional magazine)

Television

The Harrisburg TV market is served by:

- WGAL – (NBC)

- WXBU – (Comet)

- WHBG-TV – cable-only, public access

- WHP-TV – (CBS)

- WHTM-TV – (ABC)

- WCZS-LD – (CTVN)

- WITF-TV – (PBS)

- WPMT – (Fox)

- WLYH – independent, religious

- PCN-TV, is a cable television network dedicated to 24-hour coverage of government and public affairs in the commonwealth.

- Roxbury News –independent news

Radio

According to Arbitron, Harrisburg's radio market is ranked 78th in the nation.[70]

This is a list of FM stations in the greater Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, metropolitan area.

| Callsign | MHz | Band | "Name" Format, Owner | City of license |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WDCV | 88.3 | FM | Indie/College Rock, Dickinson College | Carlisle |

| WXPH | 88.7 | FM | WXPN relay, University of Pennsylvania | Harrisburg |

| WSYC | 88.7 | FM | Alternative, Shippensburg University | Shippensburg |

| WITF-FM | 89.5 | FM | NPR | Harrisburg |

| WVMM | 90.7 | FM | Indie/College Rock, Messiah College | Grantham |

| WJAZ | 91.7 | FM | WRTI relay, Classical/Jazz, Temple University | Harrisburg |

| WKHL | 92.1 | FM | "K-Love" Contemporary Christian | Palmyra |

| WONN-FM | 92.7 | FM | "92.7 KZF" Classic Rock | Starview |

| WZCY-FM | 93.5 | FM | "Nash FM" Country | Palmyra |

| WRBT | 94.9 | FM | "Bob" Country | Harrisburg |

| WLAN | 96.9 | FM | "FM 97" CHR | Lancaster |

| WRVV | 97.3 | FM | "The River" Classic Hits and the Best of Today's Rock | Harrisburg |

| WYCR | 98.5 | FM | "98.5 The Peak" Classic Hits | York |

| WQLV | 98.9 | FM | 98.9 WQLV | Millersburg |

| WHKF | 99.3 | FM | "Kiss-FM" CHR | Harrisburg |

| WFVY | 100.1 | FM | Adult Contemporary | Lebanon |

| WROZ | 101.3 | FM | "101 The Rose" Hot AC | Lancaster |

| WARM | 103.3 | FM | "Warm 103" Hot AC | York |

| WNNK | 104.1 | FM | "Wink 104" Hot AC | Harrisburg |

| WQXA | 105.7 | FM | "105.7 The X" Active Rock | York |

| WWKL | 106.7 | FM | "Hot 106.7" CHR | Hershey |

| WGTY | 107.7 | FM | "Great Country" | York |

This is a list of AM stations in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania metropolitan area:

| Callsign | kHz | Band | Format | City of license |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHP (AM) | 580 | AM | Conservative News/Talk | Harrisburg |

| WHYF | 720 | AM | EWTN Global Catholic Radio Network | Shiremanstown |

| WSBA (AM) | 910 | AM | News/Talk | York |

| WADV | 940 | AM | Gospel | Lebanon |

| WHYL | 960 | AM | Adult Standards | Carlisle |

| WIOO | 1000 | AM | Classic Country | Carlisle |

| WKBO | 1230 | AM | Christian Contemporary | Harrisburg |

| WQXA | 1250 | AM | Country | York |

| WLBR | 1270 | AM | Talk | Lebanon |

| WHGB | 1400 | AM | ESPN Radio (Formerly Adult R&B: The Touch) | Harrisburg |

| WTKT | 1460 | AM | sports: "The Ticket" | Harrisburg |

| WEEO (AM) | 1480 | AM | Classic Country | Shippensburg |

| WLPA | 1490 | AM | sports | Lancaster |

| WWSM | 1510 | AM | Classic Country | Annville |

| WPDC | 1600 | AM | Sport | Elizabethtown |

| Penndot | 1670 | AM | NOAA Weather and Travel | Several |

Portal internet websites

- HarrisburgPA.com[71]

Harrisburg in film

Several feature films and television series have been filmed or set in and around Harrisburg and the greater Susquehanna Valley.

Museums, art collections, and sites of interest

- Broad Street Market, one of the oldest continuously operating farmers markets in the United States.[72]

- Dauphin County Veteran's Memorial Obelisk inspired by the classic Roman/Egyptian obelisk form; located in uptown Harrisburg

- Dauphin Narrows Statue of Liberty on the Susquehanna River north of Harrisburg

- Fort Hunter Mansion and Park, located north of downtown Harrisburg on a bluff overlooking the Susquehanna River

- Harrisburg Doll Museum, which contains over 5,000 dolls and toys stretching back to 1840[73]

- John Harris – Simon Cameron Mansion, a National Historic Landmark located in downtown Harrisburg along the river

- Market Square, originally planned in 1785 and serves as the pinnacle of downtown

- National Civil War Museum, located at Reservoir Park and affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.[74]

- Pennsylvania National Fire Museum

- Pennsylvania Farm Show Complex & Expo Center, one of the largest convention/exhibition centers on the east coast which hosts the annual Pennsylvania Farm Show. It's famous for rodeos, butter sculptures, tractor square dancing, and the best milkshakes in the United States.

- Pennsylvania State Capitol Complex, the center of government for the commonwealth and home to the state capitol building, state archives, and state library

- Reservoir Park, the largest public park in the city containing an amphitheater[75] and playground, and connected to the Greenbelt

- State Museum of Pennsylvania, featuring a planetarium and the Marshalls Creek Mastodon, one of the most complete mastodon fossils in North America.[76]

- Strawberry Square, across the street from the Capitol Complex, home of many state offices and a small shopping center

- Susquehanna art museum, formerly located in downtown Harrisburg, and currently preparing a new location in the Midtown district

- Art Association of Harrisburg,[77] founded in 1926, located in the Governor Findlay Mansion

- Whitaker Center for Science and the Arts, features an IMAX theater

- Pride of the Susquehanna Riverboat, offering riverboat tours and special theme cruises.

Parks and recreation

- City Island and Beach

- Riverfront Park

- Italian Lake, 9.4 acre park located in the Uptown neighborhood.

- Wildwood Lake Park

- Reservoir Park

- Capital Area Greenbelt, a twenty mile long greenway linking city neighborhoods, parks and open spaces. It connects Wildwood Lake Park, Riverfront Park, the Harrisburg Mall, Penbrook Park, Reservoir Park, Harrisburg Area Community College, and Veterans Park. It is open to cyclists and pedestrians.[78]

Sports

Harrisburg serves as the hub of professional sports in South Central Pennsylvania. A host of teams compete in the region including three professional baseball teams, the Harrisburg Senators, the Lancaster Barnstormers, and the York Revolution. The Senators are the oldest team of the three, with the current incarnation playing since 1987. The original Harrisburg Senators began playing in the Eastern League in 1924. Playing its home games at Island Field, the team won the league championship in the 1927, 1928, and 1931 seasons. The Senators played a few more seasons before flood waters destroyed Island Field in 1936, effectively ending Eastern League participation for fifty-one years. In 1940, Harrisburg gained an Interstate League team affiliated with the Pittsburgh Pirates; however, the team remained in the city only until 1943, when it moved to nearby York and renamed the York Pirates. The current Harrisburg Senators, affiliated with the Washington Nationals, have won the Eastern League championship in the 1987, 1993, 1996, 1997, 1998, and 1999 seasons.

| Club | League | Venue | Founded | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harrisburg Senators | EL, Baseball | FNB Field | 1987 | 6 |

| Hershey Bears | AHL, Ice hockey | Giant Center | 1932 | 11 |

| Penn FC | USL, Soccer | FNB Field | 2004 | 1 |

| Harrisburg Heat | MASL, Indoor soccer | Pennsylvania Farm Show Complex | 2012 | 0 |

| Keystone Assault | WFA, Women's football | TBA | 2009 | 0 |

| Harrisburg Lunatics | PIHA, Inline hockey | Susquehanna Sports Center | 2001 | 0 |

| Harrisburg RFC | EPRU, MARFU, Rugby | Cibort Park, Bressler | 1969 | 1 |

Government

City of Harrisburg

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. City Government Center, the only city hall in the United States named for a Civil Rights Movement leader[citation needed], serves as a central location for the administrative functions of the city.[79] Harrisburg has been served since 1970 by the "strong mayor" form of municipal government, with separate executive and legislative branches. The Mayor serves a four-year term with no term limits. As the full-time chief executive, the Mayor oversees the operation of 34 agencies, run by department and office heads, some of whom form the Mayor's cabinet, including the Departments of Public Safety, which includes law enforcement and fire safety in its remit</ref> http://harrisburgpa.gov/bureau-of-police/</ref>, Public Works, Business Administration, Parks and Recreation, Incineration and Steam Generation, Building & Housing Development and Solicitor. The city has 721 employees (2003).[80] The current mayor of Harrisburg is Eric R. Papenfuse whose term expires January 2018.

There are seven city council members, all elected at large, who serve part-time for four-year terms. There are two other elected city posts, city treasurer and city controller, who separately head their own fiscally related offices.

The city government has been in financial distress for many years. It has operated under the state's Act 47 provisions since 2011. The Act provides for municipalities that are in a state akin to bankruptcy.[81]

Property tax reform

Harrisburg is also known nationally for its use of a two-tiered land value taxation. Harrisburg has taxed land at a rate six times that on improvements since 1975, and this policy has been credited by its former mayor Stephen R. Reed, as well as by the city's former city manager during the 1980s, with reducing the number of vacant structures located in downtown Harrisburg from about 4,200 in 1982 to fewer than 500 in 1995.[82] During this same period of time between 1982 and 1995, nearly 4,700 more city residents became employed, the crime rate dropped 22.5% and the fire rate dropped 51%.[82]

Harrisburg, as well as nearly 20 other Pennsylvania cities, employs a two-rate or split-rate property tax, which requires the taxing of the value of land at a higher rate and the value of the buildings and improvements at a lower one. This can be seen as a compromise between pure LVT and an ordinary property tax falling on real estate (land value plus improvement value).[83] Alternatively, two-rate taxation may be seen as a form that allows gradual transformation of the traditional real estate property tax into a pure land value tax.

Nearly two dozen local Pennsylvania jurisdictions, such as Harrisburg,[84] use two-rate property taxation in which the tax on land value is higher and the tax on improvement value is lower. In 2000, Florenz Plassmann and Nicolaus Tideman wrote[85] that when comparing Pennsylvania cities using a higher tax rate on land value and a lower rate on improvements with similar sized Pennsylvania cities using the same rate on land and improvements, the higher land value taxation leads to increased construction within the jurisdiction.[86][87]

Dauphin County

Dauphin County Government Complex, in downtown Harrisburg, serves the administrative functions of the county. The trial court of general jurisdiction for Harrisburg rests with the Court of Dauphin County and is largely funded and operated by county resources and employees.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

The Pennsylvania State Capitol Complex dominates the city's stature as a regional and national hub for government and politics. All administrative functions of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania are located within the complex and at various nearby locations.

The Commonwealth Judicial Center houses Pennsylvania's three appellate courts, which are located in Harrisburg. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which is the court of last resort in the state, hears arguments in Harrisburg as well as Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. The Superior Court of Pennsylvania and the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania are located here. Judges for these courts are elected at large.

Federal government

The Ronald Reagan Federal Building and Courthouse, located in downtown Harrisburg, serves as the regional administrative offices of the federal government. A branch of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania is also located within the courthouse. Due to Harrisburg's prominence as the state capital, federal offices for nearly every agency are located within the city.

The United States military has a strong historic presence in the region. A large retired military population resides in South Central Pennsylvania and the region is home to a large national cemetery at Indiantown Gap. The federal government, including the military, is the top employer in the metropolitan area.

Military bases in the Harrisburg area include:

| Installation Name | City | Type, Branch, or Agency |

|---|---|---|

| Carlisle Barracks | Carlisle | Managed by the Army, it is home to the United States Army War College |

| Eastern Distribution Center | New Cumberland | Managed by the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA), it is part of the Defense Distribution Depot Susquehanna (DDSP) |

| Fort Indiantown Gap | Fort Indiantown Gap | Managed by the Army, the Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs and the Pennsylvania National Guard (PANG), it serves as a military training and staging area. It is home to the Eastern Army National Guard Aviation Training Site (EAATS) and Northeast Counterdrug Training Center (NCTC) |

| Harrisburg Air Guard Base | Middletown | Home to the 193rd Special Operations Wing, it is located on the former Olmsted Air Force Base, which closed in the early 1970s and became Harrisburg International Airport |

| Naval Supply Systems Command (NAVSUP) | Mechanicsburg | Part of the Defense Distribution Depot Susquehanna (DDSP) |

Transport

Airports

Domestic and International airlines provide services via Harrisburg International Airport (MDT), which is located southeast of the city in Middletown. HIA is the third-busiest commercial airport in Pennsylvania, both in terms of passengers served and cargo shipments. But, generally due to the poor airline selection and lack of an airline hub, the more popular airports in the area are Baltimore, Dulles and the Philadelphia. However nearly 1.2 million people fly out of Harrisburg every year.

[88] Passenger carriers that serve HIA include American Airlines, United Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, and Allegiant Air. Capital City Airport (CXY), a moderate-sized business class and general aviation airport, is located across the Susquehanna River in the nearby suburb of New Cumberland, south of Harrisburg. Both airports are owned and operated by the Susquehanna Area Regional Airport Authority (SARAA), which also manages the Franklin County Regional Airport in Chambersburg and Gettysburg Regional Airport in Gettysburg.

Public transit

Harrisburg is served by Capital Area Transit (CAT) which provides public bus, paratransit, and commuter rail service throughout the greater metropolitan area. Construction of a commuter rail line designated the Capital Red Rose Corridor (previously named CorridorOne) will eventually link the city with nearby Lancaster in 2010.[89][needs update]

Long-term plans for the region call for the commuter rail line to continue westward to Cumberland County, ending at Carlisle. In early 2005, the project hit a roadblock when the Cumberland County commissioners opposed the plan to extend commuter rail to the West Shore. Due to lack of support from the county commissioners, the Cumberland County portion, and the two new stations in Harrisburg have been removed from the project. In the future, with support from Cumberland County, the commuter rail project may extend to both shores of the Susquehanna River, where the majority of the commuting base for the Harrisburg metropolitan area resides.[90]

In 2006, a second phase of the rail project designated CorridorTwo was announced to the general public. It will link downtown Harrisburg with its eastern suburbs in Dauphin and Lebanon counties, including the areas of Hummelstown, Hershey and Lebanon, and the city of York in York County.[90] Future passenger rail corridors also include Route 15 from the Harrisburg area towards Gettysburg, as well as the Susquehanna River communities north of Harrisburg, and the Northern Susquehanna Valley region.[90]

Intercity bus service

The lower level of the Harrisburg Transport Center serves as the city's intercity bus terminal. Daily bus services are provided by Greyhound, Capitol Trailways, and Fullington Trailways. They connect Harrisburg to other Pennsylvania cities such as Allentown, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Reading, Scranton, State College, Williamsport, and York and nearby, out-of-state cities such as Baltimore, Binghamton, New York, Syracuse, and Washington, D.C., plus many other destinations via transfers.[91]

Curbside intercity bus service is also provided by Megabus from the parking lot of the Harrisburg Mall in nearby Swatara Township, with direct service to Philadelphia, State College, and Pittsburgh.

Regional scheduled line bus service

The public transit provider in York County, Rabbit Transit, operates its RabbitEXPRESS bus service on weekdays between the city of York and both downtown Harrisburg and the main campus for Harrisburg Area Community College. The commuter-oriented service is designed to serve York County residents who work in Harrisburg, though reverse commutes are possible under the current schedule. Buses running this route make limited stops in the city of York and at two park and rides along Interstate 83 between York and Harrisburg before making various stops in Pennsylvania's capital city. As of May 2007, the RabbitEXPRESS operates three times in the morning and three times in the afternoon.

A charter/tour bus operator, R & J Transport, also provides weekday, scheduled route commuter service for people working in downtown Harrisburg. R & J, which is based in Schuylkill County, operates two lines, one between Frackville and downtown Harrisburg and the other between Minersville, Pine Grove, and downtown Harrisburg.

Rail

The Pennsylvania Railroad's main line from New York to Chicago passed through Harrisburg. The line was electrified in the 1930s, with the wires reaching Harrisburg in 1938. They went no further. Plans to electrify through to Pittsburgh and thence to Chicago never saw fruition; sufficient funding was never available. Thus, Harrisburg became where the PRR's crack expresses such as the Broadway Limited changed from electric traction to (originally) a steam locomotive, and later a diesel locomotive. Harrisburg remained a freight rail hub for PRR's successor Conrail, which was later sold off and divided between Norfolk Southern and CSX.

Freight rail

Norfolk Southern acquired all of Conrail's lines in the Harrisburg area and has continued the city's function as a freight rail hub. Norfolk Southern considers Harrisburg one of many primary hubs in its system, and operates 2 intermodal (rail/truck transfer) yards in the immediate Harrisburg area.[92] The Harrisburg Intermodal Yard (formerly called Lucknow Yard) is located in the north end of Harrisburg, approximately 3 miles north of downtown Harrisburg and the Harrisburg Transport Center, while the Rutherford Intermodal Yard is located approximately 6 miles east of downtown Harrisburg in Swatara Township, Dauphin County. Norfolk Southern also operates a significant classification yard in the Harrisburg area, the Enola Yard, which is located across the Susquehanna River from Harrisburg in East Pennsboro Township, Cumberland County.

Intercity passenger rail

Amtrak provides service to and from Harrisburg. The passenger rail operator runs its Keystone Service and Pennsylvanian routes between New York, Philadelphia, and the Harrisburg Transportation Center daily. The Pennsylvanian route, which operates once daily, continues west to Pittsburgh. As of April 2007, Amtrak operates 14 weekday roundtrips and 8 weekend roundtrips daily between Harrisburg, Lancaster, and Philadelphia 30th Street Station; most of these trains also travel to and from New York Penn Station. The Keystone Corridor between Harrisburg and Philadelphia was improved in the mid-first decade of the 21st century, with the primary improvements completed in late 2006. The improvements included upgrading the electrical catenary, installing continuously welded rail, and replacing existing wooden railroad ties with concrete ties. These improvements increased train speeds to 110 mph along the corridor and reduced the travel time between Harrisburg and Philadelphia to as little as 95 minutes. It also eliminated the need to change locomotives at 30th Street Station (from diesel to electric and vice versa) for trains continuing to or coming from New York. As of Federal Fiscal Year 2008, the Harrisburg Transportation Center was the 2nd busiest Amtrak station in Pennsylvania and 21st busiest in the United States.[93][94]

Bridges

Harrisburg is the location of over a dozen large bridges, many up to a mile long, that cross the Susquehanna River. Several other important structures span the Paxton Creek watershed and Cameron Street, linking Center City with neighborhoods in East Harrisburg. These include the State Street Bridge, also known as the Soldiers and Sailor's Memorial Bridge, and the Mulberry Street Bridge. Walnut Street Bridge, now used only by pedestrians and cyclists, links the downtown and Riverfront Park areas with City Island but goes no further as spans are missing on its western side due to massive flooding resulting from the North American blizzard of 1996.

Education

Public schools

The City of Harrisburg is served by the Harrisburg School District. The school district provides education for the city's youth beginning with all-day kindergarten through twelfth grade. A multi-year restructuring plan is aimed at making the district a model for urban public schools. The district has been troubled for decades with management fiascos and low test scores. In the summer of 2007, more than 2,000 city students were enrolled in educational programs offered by the Harrisburg School District as remediation.[95] The District has been among the lowest ranking districts for academics in the Commonwealth, ranking 492nd out of 496 district ranked by the Pittsburgh Business Times, in 2014.[96] Additionally, several of the Harrisburg School District's school have been listed on the lowest 15% achievement list each year since 2011. This designation means the students qualify for the State's Opportunity Scholarship program. Scholarships, funded by businesses, are available to attend another public school district or a private school.[97][98] One school in the Harrisburg School District has had consistently adequate academic achievement, Math Science Academy serves pupils grades 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th.[99]

In 2003, SciTech High, a regional math and science magnet school (affiliated with Harrisburg University), opened its doors to local students.

- Public Charter Schools

The city also has several public charter schools: Infinity Charter School, Sylvan Heights Science Charter School, Premier Arts and Science Charter School and Capital Area School for the Arts. A growing number of statewide, virtual, public charter schools provide residents with many alternatives to the bricks and mortar public school system. The cyber charter school Commonwealth Connections Academy Cyber School is headquartered in Harrisburg.[100]

The Central Dauphin School District, the largest public school district in the metropolitan area and the 13th largest in Pennsylvania, has several Harrisburg postal addresses for many of the District's schools. Steelton-Highspire School District borders much of the Harrisburg School District.

Private schools

Harrisburg is home to an extensive Catholic educational system. There are nearly 40 parish-driven elementary schools and seven Catholic high schools within the region administered by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Harrisburg, including Bishop McDevitt High School and Trinity High School. Numerous other private schools, such as The Londonderry School and The Circle School, which is a Sudbury Model school, also operate in Harrisburg. Harrisburg Academy, founded in 1784, is one of the oldest independent college preparatory schools in the nation. The Rabbi David L. Silver Yeshiva Academy, founded in 1944, is a progressive, modern Jewish day school. Also, Harrisburg is home to Harrisburg Christian School, founded in 1955.[101]

Higher education

In Harrisburg

- Dixon University Center, located in Uptown, serves as the office of Chancellor and the central headquarters of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (PASSHE). With a total student enrollment 110,428,[102] PASSHE is one of the largest university systems in the United States.

- Harrisburg Area Community College: the original campus of the college, the Harrisburg Campus, and Penn Center and Midtown campus which are branches of the Harrisburg Campus are located in Harrisburg. Newer campuses are located in Gettysburg, Lancaster, Lebanon and York.

- Harrisburg University of Science and Technology, located in Center City.

- Messiah College's Harrisburg Institute, located in Center City

- Penn State Harrisburg Eastgate Center, located in Center City.

- Temple University Harrisburg Campus, located in Center City.

- Widener University Commonwealth Law School

Near Harrisburg

- Central Pennsylvania College, located in Summerdale, Pennsylvania.

- Dickinson College, located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

- Duquesne University (Capital Region Campus), located in Lemoyne, Pennsylvania.

- Elizabethtown College, located in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania. Elizabethtown College is a consortium member of the Dixon University Center, offering seven accelerated, undergraduate degree programs in the Harrisburg area.

- Lebanon Valley College, located in Annville, Pennsylvania.

- Messiah College, located in Grantham, Pennsylvania.

- Penn State Dickinson School of Law, located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

- Penn State Hershey Medical Center, located in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

- Penn State Harrisburg (Main Campus), located nearby in Middletown, Pennsylvania.

- Shippensburg University, located in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania.

- United States Army War College, located in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

- Wilson College (Pennsylvania), located in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Libraries

- Dauphin County Law Library

- Dauphin County Library System, with eight branches in Harrisburg and suburban Dauphin County

- McCormick Library of Harrisburg Area Community College

- Harrisburg University Library

- Penn State Harrisburg Library

- State Library of Pennsylvania, which includes the Pennsylvania Law Library

- Medical library services of UPMC Pinnacle

- Law Library, Widener University School of Law

Sister cities

Harrisburg has two official sister cities as designated by Sister Cities International:

Ma'alot-Tarshiha, Israel.[103]

Ma'alot-Tarshiha, Israel.[103]

Notable people

Since the early 18th century, Harrisburg has been home to many people of note. Because it is the seat of government for the state and lies relatively close to other urban centers, Harrisburg has played a significant role in the nation's political, cultural and industrial history. "Harrisburgers" have also taken a leading role in the development of Pennsylvania's history for over two centuries. Two former U.S. Secretaries of War, Simon Cameron and Alexander Ramsey and several other prominent political figures, such as former speaker of the house Newt Gingrich, hail from Harrisburg. The actor Don Keefer was born near Harrisburg, along with the actor Richard Sanders, most famous for playing Les Nessman in WKRP in Cincinnati. Many notable individuals are interred at Harrisburg Cemetery and East Harrisburg Cemetery.

- Betty Andujar, first Republican woman to serve in Texas State Senate (1973–1983), was born in Harrisburg in 1912

- Les Bell, baseball player for 1926 World Series champion St. Louis Cardinals, was born in Harrisburg

- James Boyd, a resident of Front Street, wrote a novel about the city in 1935, Roll River[104]

- Jennifer Brady, tennis player, was born here

- Glenn Branca, avant-garde composer and guitarist, was born here

- Gilbert Brown (born 1987), basketball player for Ironi Nahariya of the Israeli Basketball Premier League

- Grafton Tyler Brown, first African American artist to create works depicting the Pacific Northwest and California

- Bruce Brubaker, baseball player for the Los Angeles Dodgers and Milwaukee Brewers

- Thomas Morris Chester, prominent Black journalist, lawyer, and soldier in the Civil War, was born here

- James Milnor Coit, teacher, was born here

- Marques Colston, wide receiver for the New Orleans Saints

- Larry Conjar, NFL player

- David Conner, U.S. Navy commodore

- Matt Cook, actor (Man with a Plan)

- Carl Cover, aviation pioneer/test pilot

- Lindsay Czarniak, ESPN anchor

- Phil Davis, UFC fighter

- Justin Duerr, musician and artist, born in Harrisburg

- John A. Ellsler (1821–1903), actor and theatre manager, born in Harrisburg

- Barney Ewell, Olympic gold medalist in National Track and Field Hall of Fame

- Carmen Finestra, TV producer and writer

- Hyleas Fountain, Olympic games heptathlete

- James Allen Gähres, music conductor

- Garry Gilliam, NFL player

- Candace Gingrich, civil rights activist

- Newt Gingrich, U.S. Representative 1979-99, Speaker of the House; born in Harrisburg

- Jimmy Gownley, New York Times best-selling author and illustrator of Amelia Rules!

- Dennis Green, head coach NFL teams the Minnesota Vikings and the Arizona Cardinals

- Scott Hilton, NFL player

- Alan Isaacman, lawyer who argued Hustler Magazine v. Falwell before the Supreme Court

- Stephanie A. Johnson (born 1952), mixed media artist, educator

- Jimmy Jones, CFL player

- Agnes Kemp (1823–1908), American physician and temperance movement leader

- Nancy Kulp, actress

- Danny Lansanah, football player for the Green Bay Packers

- Jeremy Linn, swimmer, gold and 2x-silver medalist at 1996 Atlanta Olympics, former world and American record holder

- Clyde A. Lynch, president of Lebanon Valley College

- Kenneth W. Mack, historian and professor at Harvard Law School

- Mark Malkoff, comedian and filmmaker

- Connor Maloney, professional soccer player

- Eric Martsolf, actor and singer

- LeSean McCoy, NFL running back, Philadelphia Eagles and Buffalo Bills

- Daniel C. Miller, Harrisburg City Controller

- Jeffrey B. Miller, Head of Security for the National Football League

- Robert James Miller, Medal of Honor recipient

- Kevin Mitchell, former NFL linebacker and Super Bowl winner

- Pauline Moore, actress

- Rachel Nabors, cartoonist

- John O'Hara, author, a native of Pottsville, lived in Harrisburg briefly to write his novel about the city, A Rage to Live[104]

- Piper Perri, American porn star

- Gene "Birdlegg" Pittman, blues harmonicist, singer and songwriter.[105]

- Jim Price, baseball player and broadcaster

- Rudi Protrudi, rock and roll musician

- Bruce I. Smith, state representative, Pennsylvania House of Representatives (1981-2007)

- George W. Smith, Major General in the Marine Corps

- Frank Soday, chemist influential in development of alternative uses for synthetic fiber

- Will Stanton, long-published humor writer

- Perry A. Stambaugh, member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, District 86

- Robert Stevenson, actor and politician, born 1915 in Harrisburg, Los Angeles City Council member

- Ed Ruth, three-time NCAA collegiate wrestling champion (2012-2014).

- Robert Tate, NFL cornerback for Minnesota Vikings, Baltimore Ravens, Arizona Cardinals

- M. Harvey Taylor, Pennsylvania State Senator

- Bobby Troup, actor, jazz pianist, and songwriter

- Ricky Watters, NFL running back, Pro Bowl selection and Super Bowl winner

- Jan White, NFL player

- Robert White, musician

- Kris Wilson, NFL Tight End, Kansas City Chiefs, San Diego Chargers, and Baltimore Ravens

- John Wyeth, publisher of Wyeth's Repository of Sacred Music (1810; Second Part 1813).

See also

Notes

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- ^ Official records for Harrisburg kept at downtown from July 1888 to December 1938, Capital City Airport from January 1939 to September 1991, and at Harrisburg Int'l in Middletown since October 1991.[50]

References

- ^ "Harrisburg City Council Homepage". Harrisburgcitycouncil.com. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "State and county quick facts". U. S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search" (Searchable database). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/harrisburgcitypennsylvania#qf-headnote-a

- ^ "2010 Census". census.gov. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ 75th Farm Show: A History of Pennsylvania's Annual Agricultural Exposition Dan Cupper, Accessed January 29, 2010.

- ^ Levy, Francesca (June 7, 2010). "America's Best Places to Raise a Family". Forbes.

- ^ "Harrisburg area ranked among Top 10 recession-proof cities". Harrisburg Patriot News. 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ W. Kesler Jackson, "Robbers and Incediaries: Protectionism Organizes at the Harrisburg Convention of 1827," Libertarian Papers 2, 21 (2010).

- ^ Gilbert, Stephanie Patterson. "Harrisburg's Old Eight Ward: Constructing a Website for Student Research" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 8, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2011.

- ^ a b Eggert, Gerald G., Harrisburg Industrializes: The Coming of Factories to an American Community. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. p58

- ^ [1] Archived 2006-09-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ GETTYSBURG - The Artillery Duel- YouTube[2]

- ^ "Brief History". Steelton Boro Website. 2008. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Eggert, Gerald G., Harrisburg Industrializes: The Coming of Factories to an American Community. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. p40

- ^ Eggert, Gerald G., Harrisburg Industrializes: The Coming of Factories to an American Community. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1993. p339

- ^ A Decade Later, TMI's Legacy Is Mistrust The Washington Post, March 28, 1989, p. A01.

- ^ "Harrisburg rounds up Western artifacts for auction – The Patriot News – Brief Article (May 2007)". Archived from the original on September 17, 2011.

- ^ Charles Thompson (July 14, 2015). "Harrisburg corruption charges portray former mayor Stephen Reed as unhinged from normal checks and balances". Pennlive.com. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ Corkery, Michael (September 12, 2011). "The Incinerator That Kept Burning Cash". WSJ.

- ^ Malawskey, Nick (May 29, 2012). "Harrisburg's eye-popping debt". The Patriot-News.

- ^ Emily Previti (August 28, 2013). "Harrisburg officials considering tax incentives for 10 city properties". The Patriot-News. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Malanga, Steve (June 1, 2013). "The Many Ways That Cities Cook Their Bond Books". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 1, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland, Donald (May 6, 2013). "SEC charges Harrisburg with fraud; settled case puts all municipalities on notice". The Patriot-News. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ "Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Chapter 9 Voluntary Petition" (PDF). PacerMonitor. PacerMonitor. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ Voluntary Chapter 9 petition, docket entry 1, Oct. 11, 2011, case no. 1:11-bk-06938-MDF, U.S. Bankr. Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania

- ^ Veronikis, Eric (October 12, 2011). "Harrisburg City Council attorney Mark D. Schwartz files bankruptcy petition". Patriot News. Retrieved November 8, 2013.

- ^ Stech, Kasey; Nolan, Kelley (November 25, 2011). "Harrisburg Bankruptcy Filing Voided". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Luhbi, Tamy (November 23, 2011). "Troubled Harrisburg Now State's Problem". CNN Money. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ a b Burton, Paul (March 30, 2012). "Frustrated Harrisburg Receiver David Unkovic Resigns". The Bond Buyer. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "Rough politics, race and a corrupt Wall Street all factors in Harrisburg's financial distress, says former Receiver David Unkovic". The Patriot-News. March 19, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Malawskey, Nick (June 12, 2012). "Harrisburg receiver William Lynch gives City Council ultimatum: Act on fiscal plan or I'll go to court". Harrisburg Patriot Naws. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ "Harrisburg City Council Respond to Unkovic Op-ed". CBS 21 News, Harrisburg Pa. June 11, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.[permanent dead link]