Yakuts

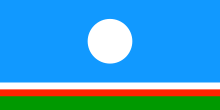

Саха | |

|---|---|

Flag of Yakutia | |

| File:Sakha family.jpg A Yakut family | |

| Total population | |

| c. 500,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 478,085 (2010 census)[1] | |

| 415 (2009 census)[2][3][4] | |

| 304 (2001 census)[5] | |

| 37 (2021 statistics)[6][7] | |

| Languages | |

| Yakut, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Shamanism, Eastern Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dolgans, Tuvans, Khakas, Altay, Mongols and Buryats (partially, possibly through Kurykans), Xiongnu, other Turkic people | |

The Yakuts, or the Sakha (Yakut: саха, sakha; plural: сахалар, sakhalar), are a Turkic ethnic group who mainly live in the Republic of Sakha in the Russian Federation, with some extending to the Amur, Magadan, Sakhalin regions, and the Taymyr and Evenk Districts of the Krasnoyarsk region. The Yakut language belongs to the Siberian branch of the Turkic languages. The Russian word yakut was taken from Evenk yokō. The Yakuts call themselves Sakha, or Urangai Sakha (Yakut: Уран Саха, Uran Sakha) in some old chronicles.[8]

Origin

Early scholarship

An early work on the Yakut ethnogenesis was drafted by the Russian Collegiate Assessors I. Evers and S. Gornovsky in the late 18th century. At an unspecified time in the past certain tribes resided around the western shore of the Aral Sea. These peoples later migrated eastward and settled near the Tunka Goltsy mountains of modern Buryatia. Pressure from the expansionist Mongolian Empire later made many of those around the Tunka Goltsy relocate to the Lena River. Several additional Altai-Sayan region tribes later arrived on the Lena to flee from the Mongols. The subsequent cultural melding that occurred between these incoming migrants eventually created the Yakuts. The Sagay Khakas of Abakan River were presented as the origin of the ethnonym Sakha by Evers and Gornovsky.[9][10]

In the mid-19th century Nikolai S. Schukin wrote "A Trip to Yakutsk” based on his experiences visiting the area. He presented a somewhat different origin of the Yakuts based upon local oral histories. Groups of Khakas inhabiting the southern Yenisey watershed migrated north to the Nizhnyaya Tunguska River to the Lena Plateau and finally onward to the Lena River.[11] Schukin is credited as introducing the concept of Yenisey Khakas as the ancestors of the Yakut into Russian historiography.[12] The most authoritative account in support of the Yenisey origin hypothesis was written by Nikolai N. Kozmin in 1928.[13] He concluded that some Khakas moved from the Yenisey to the Angara River due to difficulties in the regional economy. In the 12th century Buryats arrived at Lake Baikal and through military force pushed the Khakas to the Lena.[14][15]

Lake Baikal

In 1893 Turkologist scholar Vasily Radlov connected the Kurykans or Gǔlìgān (Chinese: 骨利干) Tiele people from Chinese historical accounts with the Yakuts. They are mentioned as 7th century tributaries of the Tang Dynasty, reportedly living on the Angara and around Lake Baikal. Radlov hypothesized they were a mixture of Tungusic and Uyghur peoples and the forebears of the Yakut.[16]

Khoro

The Khoro (Khorin, Khorolors) Yakut maintain their progenitor was Uluu Khoro, rather than Omogoy or Ellei. Scholarship has not definitively established their ancestral ethnic affiliations. Their homeland was somewhere in the south and called Khoro sire. When the Khorolors arrived in the Middle Lena remains uncertain, with scholars estimating from the first millennium to the 16th century CE.[17]

Among scholars a commonly accepted hypothesis is that the Khoro Yakut originate from the Khori Buryat of Lake Baikal,[18][19] and therefore spoke a Turko-Mongolic language.[20] This is largely based on their similar ethnonyms. Proponents see the word Khoro as arising from the Tibetan word hor (Template:Lang-bo).[21][22] For example, according to G. N. Runyanstev, during the 6th through 10th centuries CE the inhabitants of Lake Baikal were called Chor.[23] Okladnikov guessed that Khoro sire was near China and adjacent to the X[vague].

This premise is not universally accepted and has been challenged by some researchers.[24] George de Roerich has argued that the word is based on the Chinese word hu (Chinese: 胡), a term used as general reference by the Chinese to refer to various Iranian or Turkic-Mongolian peoples of Central Asia. In contemporary Tibetan hor is used to describe any pastoralist "nomad of mixed origin" regardless of their ethnonym.[25] After researching their origins, Ksenofontov concluded that while the Khorolors were "formed from parts of some alien tribe that mixed with the Yakuts", there was no compelling evidence connecting them with the Khori Buryat.[26]

A more recent argument by Zoriktuev proposes that the Khorolors were originally Paleo-Asians from the Lower Amur River.[17] In contrast to their Yakut relatives, Khoro folklore focuses largely on the Raven, with some tales about the Eagle as well. In the mid 18th century Lindenau noted the Khorolors focused their religious devotion on the Raven,[27] who was alternatively referred to as “Our ancestor”, "Our deity", and “Our grandfather" by the Khorolors. This reverence arises from the Raven enabling a struggling human (either the first Khoro man or his mother) to survive by giving a flint and tinder box. Their mythos is similar to cultures from both sides of the Bering Sea;[28] the Haida, Tlingit, Tshisham of the North American Pacific Northwest Coast and the Paleoasians of the Siberian Coast like the Chukchi, Itelmen, and Koryaks all share reverence for the Raven.[29]

Autochthonous ancestry

Many researchers have concluded that the Yakut ethnogenesis was an admixture of Turko-Mongols migrating from Lake-Baikal and native Yukaghir and Tungusitic peoples residing around the Lena River.[30][31][32][33] Okladnikov detailed this conceived admixture process as the following:

"...the Turkic-speaking ancestors of the Yakuts not only pushed out the aborigines but also subjected them to their influence by peaceful means; they assimilated and absorbed them into their mass... With this, the local tribes lost the former ethnic name and a proper ethnic consciousness, no longer separating themselves from the mass of Yakuts, and [were] not opposed to them... Consequently, as a result of the mixing with Northern aborigines, the southern ancestors of the Yakuts supplemented their culture and language with new features distinguishing them from other steppe tribes."[34]

In 1996 Aleksei N. Alekseev and S. I. Nikolaeva-Somogotto alternatively proposed that Paleo-Asian and Samoyedic peoples populations instead intermarried with the incoming Turko-Mongols, for which there is some evidence.[35][36][37][38]

Traditional Yakut histories contain stories of the aboriginal peoples of Yakutia. From the subarctic Bulunsky and Verkhoyansky Districts accounts state that the Black Yukaghir (Yakut: хара дъукаагырдар) descended from migrants pushed north from the Lena River.[39] Related stories recorded in Ust'-Aldanskiy Ulus and Megino-Kangalassky District mention certain tribes leaving the region due to rising pressure from the incoming Yakuts. While some remained and intermarried with the newcomer, most went to the northern tundra.[40]

Ymyyakhtakh

The Ymyyakhtakh are an ancient people of the Lena River. A burial ground was excavated and anthropologists I.I. Gokhman and L.F. Tomtosova studied the human remains and published their results in 1992. They concluded that some of the Late Neolithic population took part in the formation of the modern Yakuts.[36] The consistency of related artistic embellishments on the traditional clothing of the Buryat, Samoyed, and Yakut led one scholar to conclude they are related.[37] Toponymic data of Yakutia indicates there was once a presence of Paleoasian and Samoyed habitation in the region.[38] Vilyui Tumats reportedly practiced anthropophagy and seen as an "ethnocultural marker" of the Samoyedic peoples.[41]

Tumats

The Tumat stand out in Yakut tradition as a numerous and powerful society, with constant conflict once happening with them on the Vilyuy River.[42] Their households were semi-subterranean with sod roofing and are comparable to traditional Samoyed dwellings.[43] The term Doubo (Chinese: 都播) was used in medieval Chinese historical works in reference to the Sayano-Altai forest peoples. Vasily Radlov concluded that Doubo referred to the Samoyedic peoples.[44] Doubo is additionally seen as the origin of the ethnonym "Tumat" by L. P. Potapov.[45]

The Yakuts called the Tumat people "Dyirikinei" or "chipmunk people" (Yakut: Sдьирикинэй), arising from the Tumatian "tail-coat." Bundles of deer fur were dyed with red ocher and sewn into Tumatian jackets as adornments. Tumat hats were likewise dyed red.[46] This style was likely spread by the Tumatians to some Tungusic peoples. Similar clothing has been reported during the 17th century for the Evenks on the upper Angara and for Evens residing on the lower Kolyma in the early 19th century.[47] Additionally there are many similarities between the clothing of the Tumats and Altaic cultures. Archeological work on Pazyryk culture sites have turned up both hats dyed red and tail-coats made of sables. While the "tails" were not dyed red, they were sewn with red dyed thread. Stylistic and design choices are also comparable to traditional Khakas and Kumandin clothing.[48]

Some peaceable interactions including intermarriage did occur with the Tumats. One such example is the life of Džaardaakh (Russian: Джаардаах), a Tumatian woman. She was renowned for her physical strength and martial repute as an archer. However Džaardaakh eventually married a Yakut man and is considered a notable ancestor of the local Vilyuy Yakut.[49] The origin of her name has been linked to a Yukaghir word for ice (Yukaghir: йархан).[50]

The ancestors of Yakuts were Kurykans who migrated from Yenisey river to Lake Baikal and were subject to a certain Mongolian admixture prior to migration in the 7th century.[51] The Yakuts originally lived around Olkhon and the region of Lake Baikal. Beginning in the 13th century they migrated to the basins of the Middle Lena, the Aldan and Vilyuy rivers under the pressure of the rising Mongols. The northern Yakuts were largely hunters, fishermen and reindeer herders, while the southern Yakuts raised cattle and horses.[52][53]

History

Imperial Russia

In the 1620s the Tsardom of Muscovy began to move into their territory and annexed or settled down on it, imposed a fur tax and managed to suppress several Yakut rebellions between 1634 and 1642. The tsarist brutality in collection of the pelt tax (yasak) sparked a rebellion and aggression among the Yakuts and also Tungusic-speaking tribes along the River Lena in 1642. The voivode Peter Golovin, leader of the tsarist forces, responded with a reign of terror: native settlements were torched and hundreds of people were killed. The Yakut population alone is estimated to have fallen by 70 percent between 1642 and 1682, mainly because of smallpox and other infectious diseases.[54][55]

In the 18th century the Russians reduced the pressure, gave Yakut chiefs some privileges, granted freedom for all habitats, gave them all their lands, sent Eastern Orthodox missions, and educated the Yakut people regarding agriculture. The discovery of gold and, later, the building of the Trans-Siberian Railway, brought ever-increasing numbers of Russians into the region. By the 1820s almost all the Yakuts claimed to have converted to the Russian Orthodox church, but they retained (and still retain) a number of shamanist practices. Yakut literature began to rise in the late 19th century, and a national revival occurred in the early 20th century.

Russian Civil War

The last conflict of the Russian Civil War, known as the Yakut Revolt, occurred here when Cornet Mikhail Korobeinikov, a White Russian officer, led an uprising and a last stand against the Red Army.

Soviet Union

In 1922, the new Soviet government named the area the Yakut Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. In the late 1920s through the late 1930s, Yakut people were systematically persecuted, when Joseph Stalin launched his collectivization campaign.[56] It is possible that hunger and malnutrition during this period resulted in a decline in the Yakut total population from 240,500 in 1926 to 236,700 in 1959. By 1972, the population began to recover.[57]

Russian Federation

Currently, Yakuts form a large plurality of the total population within the vast Sakha Republic. According to the 2010 Russian census, there were a total of 466,492 Yakuts residing in the Sakha Republic during that year, or 49.9% of the total population of the Republic.

Culture

The Yakuts engage in animal husbandry, traditionally having focused on rearing horses, mainly the Yakutian horse, reindeer and the Sakha Ynagha ('Yakutian cow'), a hardy kind of cattle known as Yakutian cattle which is well adapted to the harsh local weather.[58][59]

Certain rock formations named Kigilyakh, as well as places such as Ynnakh Mountain, are held in high esteem by Yakuts.[60]

Cuisine

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

The cuisine of Sakha prominently features the traditional drink kumis, dairy products of cow, mare, and reindeer milk, sliced frozen salted fish stroganina (строганина), loaf meat dishes (oyogos), venison, frozen fish, thick pancakes, and salamat—a millet porridge with butter and horse fat. Kuerchekh (Куэрчэх) or kierchekh, a popular dessert, is made of cow milk or cream with various berries. Indigirka is a traditional fish salad. This cuisine is only used in Yakutia.[citation needed]

Language

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

According to the 2010 census, some 87% of the Yakuts in the Sakha Republic are fluent in the Yakut (or Sakha) language, while 90% are fluent in Russian.[61] The Sakha/Yakut language belongs to the Northern branch of the Siberian Turkic languages. It is most closely related to the Dolgan language, and also to a lesser extent related to Tuvan and Shor.

DNA and genetics analysis

The primary Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup for the Yakut is N-M231. While found in around 89% of the general population,[51] in northern Yakutia it is closer to 71%.[62] The remaining haplogroups are approximately: 4% C-M217 (including subclades C-M48 and C-M407), 3.5% R1a-M17 (including subclade R1a-M458), and 2.1% N-P43, with sporadic instances of I-M253, R1b-M269, J2, and Q.[63][62]

According to Adamov, haplogroup N1c1 makes up 94% of the Sakha population. This genetic bottleneck has been dated approximately to 1300 CE ± 200 ybp and speculated to have caused by high mortality rates in warfare and later relocation to the Middle Lena River.[64]

The primary mitochondrial DNA haplogroups are haplogroup C at 36% to 45.7% and haplogroup D at 25.7% to 32.9% of the Yakut.[62] Minor Eastern Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups include: 5.2% G, 4.49% F, 3.55% M13a1b, 1.89% A, 1.18% Y1a, 1.18% B, 0.95% Z3, and 0.71% M7.[62] Western Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups make up 9.93% of the Yakut, which include: 3.55% H, 1.42% W, 1.42%J1c5, 1.18% T2, 1.18% HV1a1a, 0.47% R1b2a, 0.47% U5b1b1a, and 0.24% U4d2.[62]

Notable people

Academia

- Georgiy Basharin, Professor at the Yakutsk State University

- Zoya Basharina, professor at Yakutsk State University

Arts

- Evgenia Arbugaeva, photographer

Cinema and Television

- Anna Kuzmina, actress

Military

- Vera Zakharova, was a Po-2 air ambulance pilot in the Soviet Air Force during World War II

- Valery Kuzmin, Soviet pilot

- Fyodor Okhlopkov, was a Soviet sniper

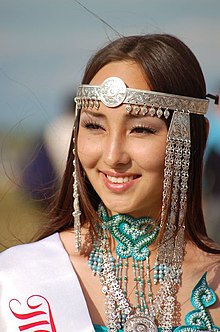

Models

Musicians

Politicians

Rulers

- Tygyn Darkhan, king of the Yakuts

Sports

- Georgy Balakshin, boxer

- Vasilii Egorov, boxer

- Pavel Pinigin, former Soviet wrestler and Olympic champion

See also

- Aisyt (Ajysyt/Ajyhyt), the name of the mythic mother goddess of the Sakha people

- Kurumchi culture

- Music in the Sakha Republic

- Turkic people

- Yakutia

- Yakut language

References

- ^ Russia 2010a.

- ^ Kazakhstan 2009a.

- ^ Kazakhstan 2009b.

- ^ Kazakhstan 2009c.

- ^ Ukraine 2001.

- ^ Latvia 2021.

- ^ E.U. 2021.

- ^ ITNR 2018.

- ^ Ivanov 1974, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Ushnitskiy 2016a, p. 150.

- ^ Schukin 1844, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1992, p. 108.

- ^ Kozmin 1928, p. 273.

- ^ Ushnitskiy 2016a, p. 152.

- ^ Radlov 1893, p. 134.

- ^ a b Zoriktuev 2011.

- ^ Rumyantsev 1962, p. 144.

- ^ Ovchinnikov 1897.

- ^ Nimaev 1988, p. 108.

- ^ Karmay 1993, p. 244.

- ^ de Roerich 1999, p. 42.

- ^ Rumyantsev 1962, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Dashieva 2020, pp. 943–944.

- ^ de Roerich 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Zoriktuev 2011, p. 120.

- ^ Lindenau 1983, p. 18.

- ^ Zoriktuev 2011, p. 121.

- ^ Krasheninnikov 1949, p. 406.

- ^ Tokarev 1949.

- ^ Okladnikov 1955.

- ^ Konstantinov 1978.

- ^ Gogolev 1993.

- ^ Okladnikov 1970, pp. 302–303.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018.

- ^ a b Gokhman & Tomtosova 1992, p. 117.

- ^ a b Pavlinskaya 2001, p. 231.

- ^ a b Stepanov 2005.

- ^ Ergis 1960, p. 282.

- ^ Ergis 1960, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Ergis 1960, p. 103.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, p. 120.

- ^ Radlov 1893, p. 191.

- ^ Potapov 1969, p. 182.

- ^ Okladnikov 1955, p. 339.

- ^ Tugolukov 1985, pp. 216, 235.

- ^ Bravina & Petrov 2018, p. 121.

- ^ Ksenofontov 1977, p. 206.

- ^ Ivanov 2000, p. 19.

- ^ a b Khar'kov et al. 2008.

- ^ Levin & Potapov 1956.

- ^ Antipin 1963.

- ^ Richards 2003, p. 238.

- ^ Levene & Roberts 1999, p. 155.

- ^ Davis, Harrison & Howell 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Lewis 2012.

- ^ Kantanen 2012.

- ^ Meerson.

- ^ Andreyevich 2020.

- ^ Russia 2010b.

- ^ a b c d e Fedorova et al. 2013.

- ^ Duggan et al. 2013.

- ^ Adamov 2008, p. 652.

Bibliography

Books

- Alekseev, N. A.; Emelyanov, N. V.; Petrov, V. T., eds. (2005). В этом разделе публикуются материалы по книге «Предания, легенды и мифы саха (якутов)» [Traditions, legends and myths of Sakha] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka. pp. 12–16. ISBN 5-02-030901-X. Retrieved 2022-01-25.

- Antipin, V. N., ed. (1963). Советская Якутия [Soviet Yakutia]. История Якутской АССР (in Russian). Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Arutyunov, S. A.; Sergeyev, D. A. (1975). Проблемы этнической истории Берингоморья: Эквенский могильник [Problems of the Ethnic History of the Bering Sea: Ekvensky Burial Ground] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Davis, Wade; Harrison, K. David; Howell, Catherine Herbert (2007). Book of Peoples of the World: A Guide to Cultures. National Geographic Books. ISBN 978-1-4262-0238-4.

- Dzharylgasinova, R. (1972). Древние когурёсцы (к этнической истории корейцев) [Ancient Koguryeo people (on the ethnic history of the Koreans)] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Ergis, G. U., ed. (1960). Исторические предания и рассказы якутов [Historical legends and stories of the Yakuts] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow; Leningrad: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Gogolev, A. I. (1993). Проблемы этногенеза и формирования культуры [The Yakuts: Problems of ethnic genesis and cultural formation] (in Russian). Yakutsk: Yakutsk State University.

- Gokhman, I. I.; Tomtosova, L. F. (1992). "Антропологические исследования неолитических могильников Диринг-Юрях и Родинка" [Anthropological researches of the Neolithic burial grounds of Diring-Yuryakh and Rodinka]. Археологические исследования в Якутии: Сб. трудов Приленской археол. экспедиции [TEST] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka. pp. 105–124.

- Ivanov, V. F. (1974). Историко-этнографическое изучение Якутии XVII–XVIII вв [Historical and ethnographic study of Yakutia of the 17th and 18th centuries] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Kochnev, D. A. (1899). "Очерки юридического быта якутов" [Essays on the legal life of the Yakuts]. Proceedings of the Society of Archeology, History, Ethnography at the Imperial Kazan University. 15 (2). Imperial Kazan University.

- Konstantinov, I. V. (1978). Ранний железный век Якутии [Early Iron Age in Yakutia] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Kozmin, Nikolai Nikolaevich (1928). "К вопросу о происхождении якутов-сахалар" [On the origin of the Yakut-sakhalar] (in Russian). Irkutsk.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Krasheninnikov, S. P.. (1949). Описание Земли Камчатки (in Russian). Moscow, Leningrad: Glavsevmorput. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- Ksenofontov, G. V. (1977). Эллэйада: Материалы по мифологии и легендарной истории якутов [Elleiada (fables about Ellei): Materials on Yakuts’ mythology and legendary history] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

- Ksenofontov, G. V. (1992). Ураанхай сахалар: Очерки по древней истории якутов [Uraankhay-sakhalar: Essays on the ancient history of the Yakuts] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Yakutsk: Бичик.

- Levene, Mark; Roberts, Penny (1999). The Massacre of History. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-934-5.

- Lindenau, Jacob Johan (1983). Описание народов Сибири (первая половина XVIII века): Историко-этнографические материалы о народах Сибири и Северо-Востока [Description of the Peoples of Siberia (First Half of the Eighteenth Century): Historical and Ethnographical Materials on the Peoples of Siberia and North-East]. Дальневосточная историческая библиотека (in Russian). Translated by Titova, Z. D. Magadan: Magadan.

- Levin, M. G.; Potapov, L. P., eds. (1956). Народы Сибири [Peoples of Siberia] (in Russian). Moscow: USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing House.

- Nimaev, D. D. (1988). Проблемы этногенеза бурят [Problems of the ethnogenesis of the Buryats] (in Russian). Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Okladnikov, A. P. (1955). Якутия до присоединения к русскому государству [Yakutia before joining Russia] (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow, Leningrad: yes.

- Okladnikov, Alexey Pavlovich (1970). Michael, Henry N. (ed.). Yakutia: Before its incorporation into the Russian State. Anthropology of the North: Translations from Russian Sources. Montreal & London: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-9068-7.

- Ovchinnikov, Mikhail Pavlovich (1897). Из материалов по этнографии якутов [From the materials on the ethnography of the Yakuts]. Этнографическое обозрение (in Russian).

- Pavlinskaya, L. R. (2001). Некоторые аспекты культурогенеза народов Сибири (по материалам шаманского костюма) [Some aspects of the cultural genesis of Siberian peoples (materials of shaman's costume)] (in Russian). St. Petersburg: Евразия сквозь века. pp. 229–232.

- Popov, Gavriil V. (1986). Слова «неизвестного происхождения» якутского языка (сравнительно-историческое исследование) [Words of "unknown origin" of the Yakut language (comparative historical study)] (in Russian). Yakutsk: Yakut Book Publishing House.

- Potapov, L. P. (1969). Этнический состав и происхождение алтайцев: Историко-этнографический [Ethnic structure and origin of Altai people: A historical and ethnographic essay] (in Russian). Leningrad: Nauka.

- Radlov, Vasily Vasilievich (1893). Aus Sibirien: Lose Blätter aus meinem Tagebuche [From Siberia: Loose Leaves from my Diary] (in German). Leipzig: T. O. Weigel Nachfolger.

- Richards, John F. (2003). The Unending Frontier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World. University of California Press. ISBN 0520939352.

- de Roerich, George (1999). test [Tibet and Central Asia: Articles, Lectures, Translations] (in Russian). Samara: Publishing House Agni.

- Rumyantsev, G. N. (1962). Происхождение хоринских бурят [Origin of the Khori Buryats] (in Russian). Ulan-Ude: Buryat Book Publishing House.

- Schukin, Nikolai Semyonovich (1844). Поездка в Якутск [A Trip to Yakutsk] (in Russian) (2nd ed.). St. Petersburg: Типография Временного Департамента Военных Поселений.

- Stepanov, A. D. (2005). Самодийская и юкагирская топонимика на карте Якутии: К проблемам генезиса древ-них культур Севера [Samoyedic and Yukaghir toponymics on the map of Yakutia: genesis of ancient cultures of the North revisited]. Социогенез в Северной Азии (in Russian). Irkutsk: Издательство ИРНИТУ. pp. 223–227.

- Tugolukov, V. A. (1985). Тунгусы (эвенки и эвены) Средней и Западной Сибири [Tungusic people (Evenkis and Evens) of Central and Western Siberia] (in Russian). Moscow: Nauka.

Articles

- Adamov, D. (2008). "Расчет возраста популяции якутов, принадлежащих к гаплогруппе N1c1" [Calculation of age for Yakut population belonging to haplogroup N1c1] (PDF). Proceedings of the Russian Academy of DNA Genealogy (in Russian). 1 (4): 646–656. ISSN 1942-7484. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-30.

- Bravina, R.I.; Petrov, D.M. (2018). "TRIBES «WHICH BECAME WIND»: AUTOCHTHONOUS SUBSTRATE IN ETHNOCULTURAL GENESIS OF THE YAKUTS REVISITED" (PDF). Vestnik Arheologii, Antropologii I Etnografii (in Russian). 2 (41). Institute for Humanities Research and Indigenous Studies of the North: 119–127. doi:10.20874/2071-0437-2018-41-2-119-127.

- Dashieva, Nadezhda B. (2020-12-25). "Образ оленя-солнца и этноним бурятского племени Хори" [Image of the Deer-Sun and Ethnonym of the Khori Buryats]. Oriental Studies (in Russian). 13 (4). East Siberian State Institute of Culture: 941–950. doi:10.22162/2619-0990-2020-50-4-941-950. S2CID 243027767. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- Duggan, Ana T.; et al. (2013-12-12). "Investigating the Prehistory of Tungusic Peoples of Siberia and the Amur-Ussuri Region with Complete mtDNA Genome Sequences and Y-chromosomal Markers". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e83570. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...883570D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083570. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3861515. PMID 24349531.

- Fedorova, Sardana A.; et al. (2013-06-19). "Autosomal and uniparental portraits of the native populations of Sakha (Yakutia): implications for the peopling of Northeast Eurasia". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 127. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-127. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3695835. PMID 23782551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Ivanov, M. S. (2000). "Замыслившие побег в Пегую орду...: (О топониме Яркан-Жархан)" [Those who planned to flee to the Skewbald Horde…: (About the toponym Zharhan)]. Илин (in Russian) (1): 17–20.

- Karmay, Samten G. (1993). "The theoretical basis of the Tibetan epic, with reference to a 'chronological order' of the various episodes in the Gesar epic". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 56 (2): 234–246. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00005498. ISSN 0041-977X. S2CID 162562519.

- Khar'kov, V. N.; et al. (2008). "[The origin of Yakuts: analysis of Y-chromosome haplotypes]". Molekuliarnaia Biologiia. 42 (2): 226–237. ISSN 0026-8984. PMID 18610830.

- Petri, B. E. (1922). "М.П. Овчинников как археолог" [M.P. Ovchinnikov as an archaeologist]. Сибирские огни (4).

- Petri, B. E. (1923). "Доисторические кузнецы в Прибайкалье. К вопросу о доисторическом прошлом якутов" [Prehistoric blacksmiths in the Baikal region. On the prehistoric past of the Yakuts.]. Известия Института народного образования. 1. Chita: 62–64.

- Strelov, E. D. (1936). "Одежда и украшения якутки в половине XVIII в. (по археологическим материалам)" [Clothing and jewelry of the Yakut in the middle of the 18th century. (based on archaeological materials)]. Soviet Ethnography. 2–3: 75–99. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- Tokarev, S. A. (1949). "К постановке проблем этногенеза" [Problems of ethnic genesis revisited]. Советская Этнография (3): 12–36.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy V. (2016a). "Researchers of Tsarist Russia on the study of the origin of the Sakha people". Vestnik Tomskogo Gosudarstvennogo Universiteta (in Russian) (407). Yakutsk: Institute of the Humanities and the Indigenous Peoples: 150–155. doi:10.17223/15617793/407/23.

- Ushnitskiy, Vasiliy. V. (2016b). "The Problem of the Sakha People's Ethnogenesis: A New Approach". Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities and Social Sciences. 8: 1822–1840. doi:10.17516/1997-1370-2016-9-8-1822-1840.

- Zoriktuev, B.R. (2011). "Who are the Yakut Khorolors? (a contribution to the issue of ethnic identification)". Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia. 39 (2): 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2011.08.012.

Census information

- E.U. (2021). "data.europa.eu" (in Latvian). data.europa.eu. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Kazakhstan (2009a). "Kazakhstan in 2009" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Kazakhstan (2009b). "Official website of the 2009 Kazakh census" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 2013-08-10. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Kazakhstan (2009c). "Nationality composition of population" (in Kazakh). Bureau of National Statistics. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Latvia (2021). "Latvia population estimate" (PDF) (in Latvian). Office of Citizenship and Immigration Affairs. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Russia (2010a). "Official website of the 2010 Russian census" (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original on 2016-03-25. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Russia (2010b). "Languages spoken … by subjects of the Russian Federation" (PDF) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-09. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Ukraine (2001). "Official website of the 2001 Ukrainian census" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

Websites

- Andreyevich, Murzin Y. (2020). "Kigilyakhi of Yakutia" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2020-05-08. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- Kantanen, Juha (2012). "The Yakutian cattle: A cow of the permafrost" (PDF). pp. 3–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-03-10. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

- Lewis, Martin (2012-05-14). "The Yakut Under Soviet Rule". GeoCurrents. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- Meerson, F. "Survival". UNESCO. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ITNR (2018). "Yakuts". Inside the New Russia. Retrieved 2022-01-04.

Further reading

- Conolly, Violet. "The Yakuts," Problems of Communism, vol. 16, no. 5 (Sept.-Oct. 1967), pp. 81–91.

- Tomskaya, Maria. 2018. "Verbalization of Nomadic Culture in Yakut Fairytales". In: Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 9 (2): 253–62. https://doi.org/10.31648/pw.3210.

- Tomskaya, Maria. 2020. "Fairy Tale Images As a Component of Cultural Programming: Gender Aspect" [Сказочные образы как составляющая культурного программирования: гендерный аспект]. In: Przegląd Wschodnioeuropejski 11 (2): 145–53. https://doi.org/10.31648/pw.6497.