Sean Penn

Sean Penn | |

|---|---|

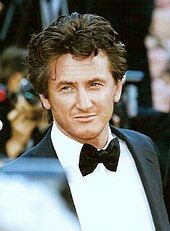

Penn in 2023 | |

| Born | Sean Justin Penn August 17, 1960 Santa Monica, California, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1974–present |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Dylan Penn Hopper Penn |

| Parents | |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Academy Award for Best Actor (2) |

Sean Justin Penn (born August 17, 1960)[1][2] is an American actor and film director. He has won Academy Awards for his roles in the mystery drama Mystic River (2003) and the biopic Milk (2008).

Penn began his acting career in television, with a brief appearance in episode 112 of Little House on the Prairie on December 4, 1974, directed by his father Leo Penn. Following his film debut in the drama Taps (1981), and a diverse range of film roles in the 1980s, including Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and Bad Boys (1983), Penn garnered critical attention for his roles in the crime dramas At Close Range (1986), State of Grace (1990), and Carlito's Way (1993). He became known as a prominent leading actor with the drama Dead Man Walking (1995), for which he earned his first Academy Award nomination and the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlin Film Festival. Penn received another two Oscar nominations for Woody Allen's comedy-drama Sweet and Lowdown (1999) and the drama I Am Sam (2001), before winning his first Academy Award for Best Actor in 2003 for Mystic River and a second one in 2008 for Milk. He has also won a Best Actor Award at the Cannes Film Festival for the Nick Cassavetes-directed She's So Lovely (1997), and two Volpi Cups for Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival for the indie film Hurlyburly (1998) and the drama 21 Grams (2003).

Penn made his feature film directorial debut with The Indian Runner (1991), followed by the drama film The Crossing Guard (1995) and the mystery film The Pledge (2001); all three were critically well received. Penn directed one of the 11 segments of 11'09"01 September 11 (2002), a compilation film made in response to the September 11 attacks. His fourth feature film, the biographical drama survival movie Into the Wild (2007), garnered critical acclaim and two Academy Award nominations.

In addition to his film work, Penn has engaged in political and social activism, including his criticism of the George W. Bush administration, his contact with the Presidents of Cuba and Venezuela, and his humanitarian work in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the 2010 Haiti earthquake.[3]

Early life

Penn was born in Santa Monica, California,[4] to actor and director Leo Penn and actress Eileen Ryan (née Annucci).[4][5] His older brother is musician Michael Penn. His younger brother, actor Chris Penn, died in 2006.[6] His father was Jewish, the son of emigrants from Merkinė, Lithuania,[7][8][9][10][11] while his mother was a Catholic of Irish and Italian descent.[11][12] Penn was raised in a secular home in Malibu, California,[9] and attended Malibu Park Junior High School and Santa Monica High School, as Malibu had no high school at that time.[13][14] He began[when?] making short films with some of his childhood friends including actors Emilio Estevez and Charlie Sheen, who lived near his home.[15]

Career

Acting

Penn appeared in a 1974 episode of the Little House on the Prairie television series as an extra when his father, Leo, directed some of the episodes.[16] Penn launched his film career with the action-drama Taps (1981), where he played a military high school cadet.[15] A year later, he appeared in the hit comedy Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), in the role of surfer-stoner Jeff Spicoli; his character helped popularize the word "dude" in popular culture.[15] Next, Penn appeared as Mick O'Brien, a troubled youth, in the drama Bad Boys (1983).[15] The role earned Penn favorable reviews and jump-started his career as a serious actor.

Penn played Andrew Daulton Lee in the film The Falcon and the Snowman (1985), which closely followed an actual criminal case.[15] Lee was a former drug dealer, convicted of espionage for the Soviet Union and originally sentenced to life in prison, but was paroled in 1998. Penn later hired Lee as his personal assistant, partly because he wanted to reward Lee for allowing him to play Lee in the film; Penn was also a firm believer in rehabilitation and thought Lee should be successfully reintegrated into society, since he was a free man again.[17]

Penn starred in the drama At Close Range (1986) which received critical acclaim.[15] He stopped acting for a few years in the early 1990s, having been dissatisfied with the industry, and focused on making his directing debut.[15]

The Academy Awards first recognized his work in nominating him for playing a racist murderer on death row in the drama film Dead Man Walking (1995).[18] He was nominated again for his comedic performance as an egotistical jazz guitarist in the Woody Allen film Sweet and Lowdown (1999).[19] He received his third nomination after portraying a mentally handicapped father in I am Sam (2001).[20] Penn finally won for his role in the Boston crime drama Mystic River (2003).[21] In 2004, Penn played Samuel Bicke, a character based on Samuel Byck, who in 1974 attempted and failed to assassinate President Richard Nixon, in The Assassination of Richard Nixon (2004). The same year, he was invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.[22] Next, Penn portrayed governor Willie Stark (based on Huey Long) in an adaptation of Robert Penn Warren's classic 1946 American novel All the King's Men (2006). The film was a critical and commercial failure, named by a 2010 Forbes article as the biggest flop in the last five years.[23]

In November 2008, Penn earned positive reviews for his portrayal of real-life politician and gay rights icon Harvey Milk in the biopic Milk (2008), and was nominated for Best Actor for the 2008 Independent Spirit Awards.[24] The film also earned Penn his fifth nomination and second win for the Academy Award for Best Actor. In Fair Game (2010), Penn starred as Joseph C. Wilson, whose wife, Valerie Plame, was outed as a CIA agent by Bush advisor Scooter Libby in retaliation for an article Wilson wrote debunking Bush's claim that Iraq was building a nuclear bomb as a rationale for invading the country. The film is based upon Plame's 2007 memoir Fair Game: My Life as a Spy, My Betrayal by the White House.

He co-starred in the drama The Tree of Life (2011), which won the Palme d'Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival. In 2015, Penn starred in The Gunman, a French-American action thriller based on the novel The Prone Gunman, by Jean-Patrick Manchette. Jasmine Trinca, Idris Elba, Ray Winstone, Mark Rylance, and fellow Oscar-winner Javier Bardem appear in supporting roles. In The Gunman, Penn played Jim Terrier, a sniper on a mercenary assassination team who kills the minister of mines of the Congo. In 2021, Penn portrayed Jack Holden, an actor based on William Holden, in the comedy-drama Licorice Pizza.

Directing

Penn made his directorial debut with The Indian Runner (1991), a crime drama film based on Bruce Springsteen's song "Highway Patrolman", from the album Nebraska (1982).[15] He also directed music videos, such as Shania Twain's "Dance with the One That Brought You" (1993), Lyle Lovett's "North Dakota" (1993), and Peter Gabriel's "The Barry Williams Show" (2002). He has since directed six more films: the indie thriller The Crossing Guard (1995), the mystery film The Pledge (2001), and the biographical drama survival film Into the Wild (2007), the drama film The Last Face (2016), the crime/drama film Flag Day (2021), and most recently the documentary Superpower (2023).[25]

Writing

In March 2018, Atria Books published Penn's novel Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff.[26] After the book's release, Penn went on a highly publicized press tour.[27][28][29] He claimed that he no longer had "a generic interest in making films", and being a writer will "dominate my creative energies for the foreseeable future".[30]

Personal life

Relationships

Penn was engaged to actress Elizabeth McGovern, his co-star in Racing with the Moon (1984). He also had a brief relationship with Susan Sarandon.[31]

Penn met singer-songwriter Madonna on set of her "Material Girl" music video in January 1985.[32] On August 16, 1985, they married on Madonna's 27th birthday; Penn turned 25 the next day.[33] The two starred in the panned Shanghai Surprise (1986), directed by Jim Goddard, and Madonna dedicated her third studio album True Blue (1986) to Penn, referring to him in the liner notes as "the coolest guy in the universe".[34] Their marriage was marred by Penn's violent outbursts against the press.[35] Madonna filed for divorce in December 1987, but withdrew the papers two weeks later.[36] In January 1989, Madonna filed for divorce again and reportedly withdrew an assault complaint against Penn following an incident at their Malibu, California, home during the New Year weekend.[37][38] Penn was alleged to have struck Madonna on multiple occasions during their marriage.[39] However, Madonna stated the allegations were "completely outrageous, malicious, reckless, and false" in 2015.[40][32]

In 1989, Penn began dating actress Robin Wright, and their first child, a daughter named Dylan Frances, was born April 13, 1991.[41] Their second child, son Hopper Jack, was born August 6, 1993.[42] Penn and Wright separated in 1995, during which time he developed a relationship with Jewel, after he spotted her performing on Late Night with Conan O'Brien. He invited her to compose a song for his film The Crossing Guard (1995) and followed her on tour.[43]

Penn reconciled with Wright and they married on April 27, 1996. The couple filed for divorce in December 2007 but reconciled several months later, requesting a court dismissal of their divorce case.[44] In April 2009, Penn filed for legal separation, only to withdraw the case once again when the couple reconciled in May.[45][46][47] On August 12, 2009, Wright filed for divorce again.[48][49] The couple's divorce was finalized on July 22, 2010; the couple reached a private agreement on child and spousal support, division of assets, and custody of Hopper, who was almost 17 at the time.[50]

In December 2013, Penn began dating South African actress Charlize Theron.[51] Their relationship ended in June 2015.[52] Despite reports that they were engaged, Theron stated that they were never engaged.[53] Theron starred in Penn's film The Last Face (2016), which they filmed while still a couple.[51]

Penn began a relationship with Australian actress Leila George in 2016.[54] They married on July 30, 2020.[55] George filed for divorce on October 15, 2021.[56] Their divorce was finalized on April 22, 2022.[57]

Legal issues

In October 1985, Penn pled no contest to charges that he assaulted two journalists when they tried to photograph him and Madonna in Nashville in June 1985.[58] He was fined $50 on each of two misdemeanor charges of assault and battery.[58]

In January 1986, Penn was charged for allegedly assaulting Leonel Borralho, Macau correspondent for the Hong Kong Standard newspaper, after he photographed Madonna and Penn as they arrived at their hotel room.[59]

In June 1986, Penn was charged with misdemeanor battery for assaulting songwriter David Wolinski at Helena's nightclub in Los Angeles.[60] Wolinski said Penn accused him of trying to kiss Madonna. Penn pled not guilty to the charge.[61]

In April 1987, Penn violated probation and was arrested for punching a film extra, Jeffrey Klein, on set of the movie Colors.[62] Penn was sentenced to 60 days in jail for this assault and reckless driving in June 1987, of which he served 33 days.[63][64] According to Penn himself, he was incarcerated in the same jail holding Richard Ramirez, a serial killer awaiting trial. Ramirez wrote to Penn, to which Penn wrote back saying he had no kinship for his fellow inmate and hopes Ramirez receives capital punishment via the gas chamber.[65]

In May 2010, Penn pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge stemming from an altercation with photographer Frank Mateljan in October 2009.[66] He was sentenced to perform 300 hours of community service and undergo 36 hours of anger management counseling.[67]

In an interview published September 16, 2015, director and showrunner Lee Daniels responded to criticism about Terrence Howard's continued career in light of his domestic violence issues by referencing Penn's rumored history of domestic violence, saying: "[Terrence] ain't done nothing different than Marlon Brando or Sean Penn, and all of a sudden he's some f—in' demon."[68] In response, Penn launched a $10 million defamation suit against Daniels, alleging that he had never been arrested for or charged with domestic violence.[69] Penn dropped the lawsuit in May 2016 after Daniels retracted his statement and apologized.[70]

Political views and activism

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (July 2023) |

Penn has been outspoken in supporting numerous political and social causes.[71] On December 13–16, 2002, he visited Iraq to protest against the Bush administration's apparent plans for a military strike on Iraq. On June 10, 2005, Penn made a visit to Iran. Acting as a journalist on an assignment for the San Francisco Chronicle, he attended a Friday prayer at Tehran University.[72] On January 7, 2006, Penn was a special guest at the Progressive Democrats of America, where he was joined by author and media critic Norman Solomon and activist Cindy Sheehan. The "Out of Iraq Forum", which took place in Sacramento, California, was organized to promote the anti-war movement calling for an end to the War in Iraq.[73]

On December 18, 2006, Penn received the Christopher Reeve First Amendment Award from the Creative Coalition for his commitment to free speech.[74] In August 2008, Penn made an appearance at one of Ralph Nader's "Open the Debates" Super Rallies. He protested against the political exclusion of Nader and other third parties.[75] In October 2008, Penn traveled to Cuba, where he met with and interviewed President Raúl Castro.[76]

In 2021, Penn denounced cancel culture, describing it as "ludicrous".[77]

George W. Bush administration

On October 18, 2002, Penn placed a $56,000 advertisement in The Washington Post asking then President George W. Bush to end a cycle of violence. It was written as an open letter and referred to the planned attack on Iraq and the War on Terror.[78]

In the letter, Penn also criticized the Bush administration for its "deconstruction of civil liberties" and its "simplistic and inflammatory view of good and evil."[79] Penn visited Iraq briefly in December 2002.[78] "Sean is one of the few," remarked his ex-wife Madonna. "Good for him. Most celebrities are keeping their heads down. Nobody wants to be unpopular. But then Americans, by and large, are pretty ignorant of what's going on in the world."[80] The Post advertisement was cited as a primary reason for the development of his relationship with Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez. In one of his televised speeches, Chávez used and read aloud an open letter Penn wrote to Bush.[81] The letter condemned the Iraq War, called for Bush to be impeached, and also called Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice "villainously and criminally obscene people."[82]

On April 19, 2007, Penn appeared on The Colbert Report and had a "Meta-Free-Phor-All" versus Stephen Colbert that was judged by Robert Pinsky. This stemmed from some of Penn's criticisms of Bush. His exact quote was "We cower as you point your fingers telling us to support our troops. You and the smarmy pundits in your pocket– those who bathe in the moisture of your soiled and blood-soaked underwear– can take that noise and shove it."[83] He won the contest with 10,000,000 points to Colbert's 1.[84] On December 7, 2007, Penn said he supported Ohio Congressman Dennis J. Kucinich for U.S. president in 2008, and criticized Bush's handling of the Iraq war. Penn questioned whether Bush's daughters, Jenna and Barbara, supported the war in Iraq.[85]

Natural disasters

In September 2005, Penn traveled to New Orleans, Louisiana, to aid Hurricane Katrina victims. He was physically involved in rescuing people,[86] although there was criticism that his involvement was a PR stunt as he hired a photographer to come along with his entourage.[87] Penn denied such accusations in an article he wrote for The Huffington Post.[88] Director Spike Lee interviewed Penn for Lee's documentary about Hurricane Katrina, When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006).

After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Penn founded the J/P Haitian Relief Organization,[89] which operated a 55,000 person tent camp.[90] Before starting the organization, Penn had never visited Haiti and did not speak French or Creole. When asked for his comment on critics who questioned his experience, he said he hopes they "die screaming of rectal cancer".[91] Due to his visibility as an on-the-ground advocate for rescue and aid efforts in the aftermath, Penn was designated by president Michel Martelly as Ambassador-at-Large for Haiti, the first time that a non-Haitian citizen has been designated as such in the country's history. Penn received the designation on January 31, 2012.[92] In 2012, at the 12th World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates, Penn received the Peace Summit Award.[93]

LGBT and gender

On February 22, 2009, Penn received the Academy Award for Best Actor for the film Milk. In his acceptance speech, he said: "I think that it is a good time for those who voted for the ban against gay marriage to sit and reflect and anticipate their great shame and the shame in their grandchildren's eyes if they continue that way of support. We've got to have equal rights for everyone!"[94]

In 2022, Penn expressed his position on masculinity, stating, "I am in the club that believes that men in American culture have become wildly feminised… I don't think that [in order] to be fair to women, we should become them." He later told The Independent that "I think that men have, in my view, become quite feminised...There are a lot of, I think, cowardly genes that lead to people surrendering their jeans and putting on a skirt."[95]

Foreign policy

Penn gained significant attention in the Pakistan media when he visited Karachi and Badin in 2012. On March 23, 2012, he visited flood-stricken villages of Karim Bux Jamali, Dargah Shah Gurio and Peero Lashari in Badin District. He was accompanied by U.S. Consul General William J. Martin and distributed blankets, quilts, kitchen items and other goods amongst flood survivors.[96][97] On March 24, 2012, Penn also visited Bilquis Edhi Female Child Home and met Pakistan's iconic humanitarian worker Abdul Sattar Edhi and his wife, Bilquis Edhi. He also laid floral wreaths and paid respect at the shrine of Abdullah Shah Ghazi.[98][99]

Penn is also believed to have played a role in getting American entrepreneur Jacob Ostreicher released from a Bolivian prison in 2013, and was credited by Ostreicher for having personally nursed him back to health upon his release.[100]

Penn is the founder of the nonprofit organization Community Organized Relief Effort (CORE), which has distributed aid to Haiti following the 2010 earthquake and Hurricane Matthew as well as administering free COVID-19 tests in the U.S. amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[101] In October 2021, the National Labor Relations Board issued a complaint that Penn and CORE violated federal labor law. According to the charge, Penn "impliedly threatened" his employees with reprisals after they complained about working conditions, including 18 hour days and the food provided.[102]

In February 2012, he stood beside Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez while Venezuela supported the Syrian government during the 2011–2012 Syrian uprising.[103] In March 2010, Penn called for the imprisonment of journalists who referred to Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez as a dictator.[104] Penn's remarks received backlash from conservative and libertarian media sources, including National Review and Reason.[105][106][107] Penn and Chávez were friends, and when the latter died in 2013, Penn said: "Venezuela and its revolution will endure under the proven leadership of Vice President Nicolás Maduro. Today the United States lost a friend it never knew it had. And poor people around the world lost a champion. I lost a friend I was blessed to have."[108] Penn's friendship with Chávez, as well as praise for Raúl Castro, has also been the subject of criticism. Human Rights Activist Thor Halvorssen, as well as media sources including The New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The New Criterion, and The Advocate all noted Castro & Chávez's strong anti-LGBT stances, a stark contrast with Penn's support of LGBT groups, attacking Penn over his support of the two leaders.[109][110][111][112] Actress María Conchita Alonso, who co-starred with Penn in Colors, also issued an "Open Letter to Sean Penn", attacking his views on Chávez.[113] In December 2011, Alonso and Penn began verbally fighting at an airport, during which Penn called her a pig and she called Penn a communist.[114]

A day after Mexican officials announced the capture of fugitive Sinaloa Cartel boss Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán in a bloody raid, Rolling Stone revealed on January 9, 2016, that Sean Penn, along with actress Kate del Castillo, had conducted a secret interview with El Chapo prior to his arrest.[115][116] Del Castillo was contacted by Guzmán's lawyer (who was under CISEN surveillance) to talk about producing a biographical film about Guzmán and communication increased following Guzmán's escape from prison in July 2015.[117] The deal for the interview was brokered by del Castillo.[118] According to published text messages with del Castillo, Guzmán did not know who Sean Penn was.[119] CISEN released photographs of del Castillo at the meetings with Guzmán's lawyers and of the arrival of the actress and Penn to Mexico. The interview was criticized by some, including the White House, which called the interview "maddening".[120] Mexican authorities said they were seeking to question Penn over the interview, which had not been approved by either the American or Mexican government.[121] Penn and del Castillo's meeting with Guzmán was under investigation by the Attorney General of Mexico.[122]

In October 2020, Penn tweeted in support of Armenia with regard to the Nagorno-Karabakh war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. He also criticized Turkey's involvement in the conflict and close Turkey–United States ties, while simultaneously endorsing Joe Biden for the 2020 U.S. presidential election. He stated: "Armenians are being slaughtered by Trump pal Erdogan with weapons WE provided. THIS is NOT America! Biden for America's new birth!".[123]

Ukraine

Penn spent time in Ukraine filming a documentary about the Russian invasion of that country.[124] Penn attended press briefings in Kyiv, met with officials and spoke to journalists and military personnel about the Russian invasion.[125][124] On February 25, 2022, Penn stated: "If we allow it [Ukraine] to fight alone, our soul as America is lost."[125] He also praised the response from the Ukrainian government and its citizens.[125] When attempting to leave the country, Penn and his team abandoned their car and walked with their luggage for miles to the Polish border.[126] Russia is sanctioning Penn over his Ukraine support.[127]

During a visit to Kyiv in November 2022, Penn lent an Oscar statuette to President Zelenskyy. Penn said to the President, "This is for you. It's just a symbolic silly thing. [...] When you win, bring it back to Malibu." On the same occasion, the President awarded Penn the Ukrainian Order of Merit.[128]

Falkland Islands

In February 2012, Penn met with the President of Argentina, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, in Buenos Aires where he made a statement on the long-running dispute between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the Falkland Islands, saying: "I know I came in a very sensitive moment in terms of diplomacy between Argentina and the UK over the Falkland Islands. And I hope that diplomats can establish true dialogue in order to solve the conflict as the world today cannot tolerate ridiculous demonstrations of colonialism. The way of dialogue is the only way to achieve a better solution for both nations."[129][130][131]

The comments were taken as support of Argentina's claim to the islands and evoked strong reactions in the British media, with one satirical article in The Daily Telegraph requesting that Penn "return his Malibu estate to the Mexicans".[132] Falklands War veteran and political activist Simon Weston stated "Sean Penn does not know what he is talking about and, frankly, he should shut up. His [Penn's] views are irrelevant and it only serves to fuel the fire of the Argentinians and get them more pumped up",[133] while British Conservative MP Patrick Mercer dismissed Penn's statement as "moronic".[134] Lauren Collins of The New Yorker wrote: "As of today, Sean Penn is the new Karl Lagerfeld—the man upon whom, having disrespected something dear to the United Kingdom, the British papers most gleefully pile contempt".[135]

Penn later claimed that he had been misrepresented by the British press and that his criticism of "colonialism" was a reference to the deployment of Prince William as an air-sea rescue pilot, describing it as a "message of pre-emptive intimidation". He claimed that the Prince's posting meant "the automatic deployment of warships", and stated: "My oh my, aren't people sensitive to the word 'colonialism', particularly those who implement colonialism."[136][137] In a piece written in The Guardian, Penn wrote that "the legalisation of Argentinian immigration to the Malvinas/Falkland Islands is one that it seems might have been addressed, but for the speculative discovery of booming offshore oil in the surrounding seas this past year". He further wrote that "irresponsible journalism" had suggested "that I had taken a specific position against those currently residing in the Malvinas/Falkland Islands, that they should either be deported or absorbed into Argentine rule. I neither said, nor insinuated that".[137][138]

Filmography

Penn has appeared in more than 50 films and won many awards during his career as an actor and director. He has won two Academy Awards for Best Actor for Mystic River (2003) and Milk (2008),[139] and was nominated three more times in the same category for Dead Man Walking (1995), Sweet and Lowdown (1999), and I Am Sam (2001).[140] He also received a Directors Guild of America nomination for directing Into the Wild (2007).[141]

In popular culture

- Penn is parodied in the 2004 film Team America: World Police, alongside other celebrities including Alec Baldwin, Tim Robbins, and Matt Damon. In the film, a puppet version of Penn makes outlandish claims about Iraq, claiming it was a utopia with "rainbow skys" and "rivers made of chocolate" before Team America arrived. In response to the film, Penn sent an angry letter to its creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, inviting them to tour Iraq with him and ending with the words "fuck you".[142]

References

- ^ "Sean Penn Biography (1960-)". FilmReference.com. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

Sean Justin Penn; born August 17, 1960, in Santa Monica (some sources cite Burbank or Los Angeles), CA ...

- ^ "Sean Penn". Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

Sean Justin Penn was born on August 17, 1960, in Santa Monica, California. His father, Leo, was an actor and director. His mother, Eileen Ryan, was an actress. Penn grew up in Los Angeles and attended Santa Monica High School along with fellow students and future actors Emilio Estevez, Charlie Sheen and Rob Lowe ...

- ^ "Leak sinks Penn's rescue mission hopes". The Guardian. September 7, 2005.

- ^ a b Chapman, Roger (2010). Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices (Revised ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-765-62250-1.

- ^ Bilmes, Alex (February 16, 2015). "Sean Penn Is Esquire's March Cover Star". Esquire. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ Tribune (January 24, 2006). "Actor Chris Penn found dead at residence". East Valley Tribune. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Tribute, The Lithuanian (February 19, 2012). "Hollywood star Sean Penn's grandfather came from which town in Lithuania?". Delfi. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ^ Pfefferman, Naomi (October 16, 1997). "Spectator". Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved June 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Tugend, Tom (March 5, 2004). Despite the hobbits, Jews win a few Oscars. J. The Jewish News of Northern California. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Sean Penn Genealogy Archived December 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Kelly, Richard T. (2004). Sean Penn: His Life and Times. Canongate Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 1-84195-623-6.

- ^ According to Penn's mother, his father may have had distant Sephardic Jewish ancestry, as his family's surname was originally "Piñón".

- ^ Garchik, Leah (January 21, 2016). "Sean Penn, an optimist who tries to save the world". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved August 20, 2020.

- ^ Abramowitz, Rachel (January 6, 2002). "Don't Get Him Started". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 1999

- ^ Reier, Evan (February 20, 2021). "'Little House on the Prairie': The Uncredited Role Sean Penn Played in the Series". Outsider. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Kelly, Richard T. (April 8, 2005). "'When Sean's having fun, it's hard to imagine having more fun'". The Guardian. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "From 'Dead Man Walking' to 'Milk': 9 Essential Sean Penn Performances". Collider. February 26, 2022. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Wolk, Josh Wolk (February 17, 2000). "Sean Penn discusses Woody Allen's Oscar-worthy directing style". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ Peikert, Mark (December 31, 2021). "'I Am Sam' Director Jessie Nelson Wouldn't Make Her Movie the Same Way Now". IndieWire. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ EW Staff (March 1, 2004). "Sean Penn had a memorable 2004 Oscars moment". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 7, 2022.

- ^ "Academy Invites 127 to Membership" (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. June 28, 2004. Archived from the original on June 30, 2004.

- ^ Pomerantz, Dorothy. Hollywood's Biggest Flops: Big-name stars weren't enough to save these box-office bombs, Forbes, January 22, 2010.

- ^ Maxwell, Erin (December 3, 2008). "Spirit Award nominees announced". work. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ Sean Penn film directorial venture reviews:

- ^ Giles, Jeff (March 27, 2018). "Sean Penn, Satirist, Swings at America in a Wild Debut Novel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Diamond, Jason (April 4, 2018). "Sean Penn: Why I Had to Write 'Bob Honey Who Just Do Stuff'". Rolling Stone.

- ^ McDonald, Jeff (April 7, 2018). "Sean Penn pivots from actor to novelist at La Jolla reading". The San Diego Union-Tribune.

- ^ French, Agatha (April 3, 2018). "Sean Penn and Jane Smiley weren't drinking the 'Bob Honey' haterade on stage in L.A." Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Seymour, Corey (April 6, 2018). "Sean Penn on Quitting the Movie Business, His New First Novel, and #MeToo". Vogue.

- ^ "Drew Barrymore and Corey Feldman — Plus More '80s Celebrity Couples You Forgot All About". October 27, 2016.

- ^ a b Stern, Marlow (December 19, 2015). "Madonna Comes Forward About Sean Penn's Alleged Abuse: 'Sean Has Never Struck Me'". The Daily Beast. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Cannon, Bob (August 14, 1992). "Madonna and Sean Penn: Justifying their love". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Madonna's love history". The Daily Telegraph. UK. October 15, 2008. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2011.

- ^ "Sean Penn got into another fight with a photographer..." United Press International. August 30, 1986. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Kaufman, Joanne (December 14, 1987). "Everyone Said It Wouldn't Last..." People. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Jeff (January 11, 1989). "Madonna Withdraws Assault Complaint Against Sean Penn". AP NEWS. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "The Incident Behind Those Sean Penn Domestic Abuse Allegations". Yahoo. September 22, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ Andersen, Christopher (November 6, 1991). "A Marriage Filled With Abuse". The Seattle Times.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (December 17, 2015). "Madonna Says Sean Penn 'Never Struck Me', Backs Ex In $10M Lee Daniels Defamation Suit". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^ MacMinn, Aleene (April 17, 1991). "Cradle Watch". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

Dylan Frances Penn was born Saturday [April 13] at 10:49 p.m. at UCLA Medical Center.

- ^ Speidel, Maria (August 23, 1993). "Passages". People. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ Schillaci, Sophie (September 23, 2015). "Jewel Reveals Pre-Fame Relationship With Sean Penn: 'I Liked His Mind'". ETOnline.com. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ White, Nicholas (December 27, 2007). "Sean Penn and Robin Wright Penn Divorcing". People. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Laudadio, Marisa; Lee, Ken (April 29, 2009). "Sean Penn Files for Legal Separation". People. Retrieved September 16, 2009.

- ^ Reaney, Patricia (April 9, 2008). "Sean Penn, wife Robin end divorce proceeding". Reuters.

- ^ "Sean Penn withdraws separation filing". USA Today. May 21, 2009.

- ^ Lee, Ken (August 18, 2009). "Robin Wright Penn Files for Divorce". People. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (August 17, 2009). "Robin Wright Penn Relishes Her New Independence". People. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ Oh, Eunice (August 4, 2010). "Sean Penn and Robin Wright Finalize Their Divorce". People. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ a b Metz, Brooke (July 27, 2017). "'The Last Face' and the tale of Charlize Theron and Sean Penn". USA Today. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Julie (June 17, 2015). "Charlize Theron and Sean Penn Have Reportedly Ended Their Engagement". Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Fernández, Alexia (June 22, 2020). "Charlize Theron Denies She Was Engaged to Sean Penn: 'I Was Never Going to Marry Him'". People. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Russian, Ale; Gauk-Roger, Topher (March 9, 2020). "Sean Penn Sweetly Supports Girlfriend Leila George at Her Australian Wildfire Relief Zoo Event". People. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Ushe, Naledi (August 4, 2020). "Sean Penn, 59, Leila George, 28, get married in secret 'COVID wedding'". Fox News. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- ^ Campione, Katie (October 15, 2021). "Sean Penn's Wife Actress Leila George Files for Divorce After 1 Year of Marriage". People. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ Brisco, Elise. "Sean Penn and Leila George finalize divorce after having a 'COVID wedding' in 2020". USA Today. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Gillem, Tom (October 17, 1985). "Actor Pleads No Contest, Fined On Assault Charges". AP NEWS. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Actor Sean Penn accused of assaulting journalist". United Press International. January 17, 1986. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Michael (July 18, 1986). "Actor Sean Penn was charged with battery Friday for..." United Press International. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Penn Pleads Not Guilty to Battery Charge". Los Angeles Times. October 29, 1986. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Arrest Warrant Issued For Sean Penn". AP NEWS. April 25, 1987. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Timnick, Lois (June 24, 1987). "Actor Sean Penn Gets 60 Days in Jail". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ciccone, Christopher (2008). Life with My Sister Madonna, Simon & Schuster, pp. 144–50; ISBN 1-4165-8762-4.

- ^ Grad, Shelby (March 10, 2015). "Sean Penn's unlikely pen pal: 'Night Stalker' Richard Ramirez". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ Duke, Alan (May 12, 2010). "Sean Penn pleads to paparazzo kick". CNN. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ "Sean Penn sent to anger management after paparazzi clash". Reuters. May 12, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- ^ Rose, Lacey (September 16, 2015). "'Empire's' "Batshit Crazy" Behind-the-Scenes Drama: On the Set of TV's Hottest Show". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (September 22, 2015). "Sean Penn Files $10 Million Defamation Lawsuit Against 'Empire' Co-Creator Lee Daniels". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Gardner, Eriq (May 4, 2016). "Sean Penn Wins Apology from Lee Daniels in Defamation Settlement". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ^ "Sean Penn: Hollywood hellraiser turned activist". BBC. January 10, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Penn, Sean. Sean Penn in Iran. San Francisco Chronicle. August 23, 2005.

- ^ Associated Press; Robin Hindery (August 14, 2016). "Challenger lashes out at Doolittle, calls him 'coward'". East Bay Times. Associated Press. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ The Creative Coalition Announces Presenters for 2006 Christopher Reeve First Amendment Award and 2006 Spotlight Awards Archived April 22, 2007, at archive.today. The Creative Coalition. December 2006.

- ^ "Sean Penn, Val Kilmer, Tom Morello, Cindy Sheehan at Nader/Gonzalez Super Rally in Denver — Ralph Nader for President in 2008". Votenader.org. August 19, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ Lacey, Marc (November 26, 2008). "Sean Penn Interviews Raúl Castro". The New York Times. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ McCarthy, Tyler (July 7, 2021). "Conan O'Brien, Sean Penn discuss cancel culture calling it 'very Soviet' and 'ludicrous'". Fox News.

- ^ a b Bowles, Scott (September 18, 2006). "Sean Penn plays politics". USA Today.

- ^ "Sean Penn Letter to Washington Post". Snopes. November 24, 2002. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

- ^ Rees, Paul: 'Listen very carefully, I will say this only once', Q, May 2003, pp84-92

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (October 14, 2007). "Sean Penn: Mr Congeniality". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on January 10, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ James, Ian (August 2, 2007). "Sean Penn Praised by Venezuela's Chavez". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ "Sean Penn Unloads on Pres. Bush". Fox News. March 27, 2007.

- ^ "Stephen Colbert vs Sean Penn". Crooks and Liars. March 27, 2007.

- ^ Penn, Sean (March 24, 2007). "An Open Letter to the President...Four and a Half Years Later". HuffPost.

- ^ Many celebrities have helped with New Orleans recovery efforts. International Herald Tribune. December 14, 2007.

- ^ "Penn's rescue attempt springs a leak". The Sydney Morning Herald. September 5, 2005. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Penn, Sean (November 30, 2008). "Mountain of Snakes". HuffPost. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

- ^ "Sean Penn: It's time to seize opportunities in Haiti". The World Bank. May 3, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ "Haitian Relief Organization". Jphro.org. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ Heller, Zoe (March 25, 2011). "The Accidental Activist". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ "Haiti names Sean Penn 'ambassador at large'". CBS News. January 31, 2012.

- ^ Schreffler, Laura (November 3, 2016). "Sean Penn Talks Haiti, Humanitarianism and Hollywood". Haute Living. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Sean Penn Oscar Speech". Mahalo.com. February 22, 2009. Retrieved February 22, 2011.

- ^ Mottram, James (January 28, 2022). "Sean and Dylan Penn on Flag Day: 'It did feel like going through therapy'". The Independent.

- ^ Razaq Khatti (March 24, 2012). "Hollywood visitor: Sean Penn comes to Badin". The Express Tribune. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Mahim Maher (March 24, 2012). "Sean Penn comes to Pakistan". JewishJournal.com. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Saba Imtiaz (March 25, 2012). "A touch of inspiration runs both ways as Sean Penn visits shrine and Edhi home". The Express Tribune. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ APP (March 25, 2012). "Actor Sean Penn visits Edhi Centre, Karachi". Dawn. Pakistan. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ "Orthodox Jewish Captive Jacob Ostreicher Reveals How Sean Penn Nursed Him Back to Health in His Own Home". The Algemeiner. May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ Isaza, Marcela (April 11, 2020). "Sean Penn wants to 'save lives' with free COVID-19 testing". Associated Press. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (October 28, 2021). "Sean Penn the Focus of N.L.R.B. Amid Comments on Hours and Food at Vaccine Site". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

- ^ "Exclusive: Venezuela ships fuel to war-torn Syria". Reuters. February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (March 11, 2010). "Sean Penn: Journalists who call Hugo Chávez a dictator should be jailed". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ "Sean Penn Wants Reporters Jailed for Calling Chavez 'Dictator'". Fox News. April 11, 2016.

- ^ Moynihan, Michael (March 9, 2010). "Sean Penn Wants Me Thrown In Jail". Reason.

- ^ Williamson, Kevin D. (March 9, 2010). "Liberal Fascism Alert: Sean Penn Edition". National Review.

- ^ "Hugo Chávez's death draws sympathy, anger". CNN. March 6, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (January 4, 2009). "Dangers of the Penn". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldstein, Patrick (December 11, 2008). "'Milk' star Sean Penn: Pal of anti-gay dictators?". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Kirchick, James (December 9, 2008). "A Friend to Gays and Antigay Dictators Alike". The Advocate.

- ^ Weiss, Michael (December 3, 2007). "Sean Penn, journalist". The New Criterion.

- ^ Bershad, Jon (March 29, 2010). "Open Letter to Sean Penn: Actress Confronts Actor On Hugo Chavez". Mediaite.com.

- ^ "Where Washington Comes To Talk Now on 105.9FM!". WMAL. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Somaiya, Ravi (January 9, 2016). "Sean Penn Met With 'El Chapo' for Interview in His Hide-Out". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "'El Chapo' Guzmán secretly met Sean Penn in Mexico". CNN. January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ López-Dóriga, Joaquín. ""Ola ermoza"…". Milenio. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ Watson, Katy (January 11, 2016). "El Chapo: Who is Kate del Castillo?". BBC News. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Texts Purportedly Reveal El Chapo's Eagerness to Meet Actress Kate del Castillo". NBC News. January 13, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2016.

- ^ "'El Chapo' Guzman: Sean Penn interview provokes US scorn". BBC News. Retrieved January 11, 2016.

- ^ "Penn won't face US charges over El Chapo interview". ABC News. January 10, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- ^ Loret de Moda, Carlos (December 1, 2016). "'Hermosa', el nombre clave de Kate". El Universal. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Armenians are being slaughtered by Trump pal Erdogan – Sean Penn". Public Radio of Armenia. October 24, 2020.

- ^ a b Sicard, Sarah (February 24, 2022). "Sean Penn filming documentary on the ground in Ukraine". Marine Corps Times. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c Burton, Jamie (February 24, 2022). "Sean Penn In Ukraine: Putin Has Made a 'Horrible Mistake', Urges U.S. to Fight". Newsweek. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ^ Respers France, Lisa (March 4, 2022). "Sean Penn walked to Polish border to leave Ukraine". CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "Russia sanctions Ben Stiller and Sean Penn over Ukraine support". Reuters. September 6, 2022. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (November 9, 2022). "Sean Penn loans his Oscar to Ukraine's president Zelenskiy". The Guardian. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ "Falklands dispute: Argentine union to boycott UK ships". BBC. February 14, 2012.

- ^ "Sean Penn backs Argentina over Falkland Islands". The Guardian. February 14, 2012.

- ^ "'The world can't tolerate anymore ridiculous colonialism', Sean Penn says after meeting CFK". Buenos Aires Herald. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ Stanley, Tim (February 15, 2012). "Sean Penn should return his Malibu estate to the Mexicans". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012.

- ^ "Sean Penn's Argentina Falklands support angers Simon Weston". BBC News. February 16, 2012. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013.

- ^ "Sean Penn: Prince William is provoking Argentina". The Seattle Times. February 16, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Collins, Lauren (February 15, 2012). "SEAN PENN'S FALKLANDS WAR". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra, Alexandra (February 15, 2012). "Sean Penn hits out at Prince William's Falklands posting". The Guardian. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ a b Penn, Sean (February 23, 2012). "Sean Penn: The Malvinas/Falklands – diplomacy interrupted". The Guardian.

- ^ Watt, Nicholas (February 23, 2012). "Sean Penn calls for Britain to negotiate with Argentina over Falklands". The Guardian.

- ^ "In pictures: Sean Penn - Oscar winning actor, ex-husband of Madonna and campaigner". The Telegraph. February 15, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ King, Susan (January 23, 2009). "Oscar lead actor nominees". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Tourtellotte, Bob (January 8, 2008). "Directors Guild names favorite directors of '07". Reuters. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Penn, Sean (October 8, 2004). "Letter by Sean Penn". DrudgeReport Archives. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

External links

- 1960 births

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Activists from California

- American anti–Iraq War activists

- American expatriates in Haiti

- American male child actors

- American male film actors

- American male stage actors

- American male television actors

- American people convicted of assault

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Italian descent

- American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor winners

- César Honorary Award recipients

- Film directors from Los Angeles

- Film producers from California

- Founders of charities

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Male Lead winners

- American LGBT rights activists

- Living people

- Male actors from Burbank, California

- Male actors from Santa Monica, California

- Method actors

- Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Santa Monica High School alumni

- Silver Bear for Best Actor winners

- Volpi Cup for Best Actor winners

- Writers from California