Holborn

| Holborn | |

|---|---|

Holborn Bars, built 1879–1901, headquarters of Prudential Assurance, at 138–142 Holborn | |

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 13,023 (2011 Census. Holborn and Covent Garden Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ305815 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | WC1, WC2 |

| Postcode district | EC1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Holborn (/ˈhoʊbən/ HOH-bə(r)n or /ˈhɒlbərn/ [a]) is a district covering the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part (St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars), of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. The area is sometimes described as part of the West End of London[2] or of the wider west London area.

The district lay on the west bank of the now buried River Fleet,[3] taking its name from an alternative name for the river. The river also gave its name to the streets Holborn and High Holborn which run east to west through Holborn and neighbouring areas.

History

Toponymy

The area's first known mention occurs in a charter of Westminster Abbey, by King Edgar, dated to 959. This mentions "the old wooden church of St Andrew" (St Andrew, Holborn).[4] The name "Holborn" may derive from the Middle English hol for "hollow", and bourne, a "brook", referring to the River Fleet as it ran through a steep valley to the east.[4][5] Historical cartographer William Shepherd in his Plan of London about 1300 labels the Fleet as "Hole Bourn" where it passes to the east of St Andrew's church.[6] However, the 16th-century historian John Stow attributes the name to the Old Bourne ("old brook"), a small stream which he believed ran into the Fleet at Holborn Bridge, a structure lost when the river was culverted in 1732. The exact course of the stream is uncertain, but according to Stow it started in one of the many small springs near Holborn Bar, the old City toll gate on the summit of Holborn Hill.[5][7] This is supported by a map of London and Westminster drawn up during the reign of Henry VIII (r. 1509–1547) that clearly marks the street as 'Oldbourne' and 'High Oldbourne'.[8][failed verification] Other historians, however, find the theory implausible, in view of the slope of the land.[9]

Local governance

It was then outside the city's jurisdiction and a part of Ossulstone Hundred in Middlesex. In the 12th century St Andrew's was noted in local title deeds as lying on "Holburnestrate"—Holborn Street.[10] The original Bars were the boundary of the City of London from 1223, when the city's jurisdiction was extended beyond the Walls, at Newgate, into the suburb here, as far as the point where the Bars were erected, until 1994 when the boundary moved to the junction of Chancery Lane. In 1394 the Ward of Farringdon was subdivided into Farringdon Within and Farringdon Without, with south-east Holborn part of the latter. The rest of the area "above Bars" (outside the city's jurisdiction) was organised by the vestry board of the parish of St Andrew.[11] The St George the Martyr Queen Square area became a separate parish in 1723 and was combined with the part of St Andrew outside the City of London in 1767 to form St Andrew Holborn Above the Bars with St George the Martyr.

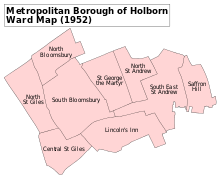

The Holborn District was created in 1855, consisting of the civil parishes and extra-parochial places of Glasshouse Yard, Saffron Hill, Hatton Garden, Ely Rents and Ely Place, St Andrew Holborn Above the Bars with St George the Martyr and St Sepulchre. The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was created in 1900, consisting of the former area of the Holborn District and the St Giles District, excluding Glasshouse Yard and St Sepulchre, which went to the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury. The Metropolitan Borough of Holborn was abolished in 1965 and its area now forms part of the London Borough of Camden.

Representation

The MPs for the area are:

- Keir Starmer MP, the Labour Party Member of Parliament for Holborn and St Pancras,

- Nickie Aiken, the Conservative MP for the Cities of London and Westminster, which includes the City of London portion of Holborn.

The three ward councillors for Holborn and Covent Garden, representing the London Borough of Camden part of the district are:

- Cllr Julian Fulbrook, Cllr Sue Vincent and Cllr Awale Olad of the Labour Party.

Holborn is represented in the London Assembly as part of Barnet and Camden by:

- Andrew Dismore, of the Labour Party.

Urban development

Henry VII paid for the road to be paved in 1494 because the thoroughfare "was so deep and miry that many perils and hazards were thereby occasioned, as well to the king's carriages passing that way, as to those of his subjects". Criminals from the Tower and Newgate passed up Holborn on their way to be hanged at Tyburn or St Giles.[12]

In the 18th century, Holborn was the location of the infamous Mother Clap's molly house (meeting place for homosexual men). There were 22 inns or taverns recorded in the 1860s. The Holborn Empire, originally Weston's Music Hall, stood between 1857 and 1960, when it was pulled down after structural damage sustained in the Blitz. The theatre premièred one of the first full-length feature films in 1914, The World, the Flesh and the Devil, a 50-minute melodrama filmed in Kinemacolor.[13][14]

Charles Dickens took up residence in Furnival's Inn (later the site of "Holborn Bars", the former Prudential building designed by Alfred Waterhouse). Dickens put his character "Pip", in Great Expectations, in residence at Barnard's Inn opposite, now occupied by Gresham College.[15] Staple Inn, notable as the promotional image for Old Holborn tobacco,[16] is nearby. The three of these were Inns of Chancery. The most northerly of the Inns of Court, Gray's Inn, is off Holborn, as is Lincoln's Inn: the area has been associated with the legal professions since mediaeval times, and the name of the local militia (now Territorial Army unit, the Inns of Court & City Yeomanry) still reflects that. Subsequently, the area diversified and become recognisable as the modern street. A plaque stands at number 120 commemorating Thomas Earnshaw's invention of the Marine chronometer, which facilitated long-distance travel. At the corner of Hatton Garden was the old family department store of Gamages. Until 1992, the London Weather Centre was located in the street. The Prudential insurance company relocated in 2002. The Daily Mirror offices used to be directly opposite it, but the site is now occupied by Sainsbury's head office.

Modern times

Further east, in the gated avenue of Ely Place, is St Etheldreda's Church, originally the chapel of the Bishop of Ely's London palace. This ecclesiastical connection allowed the street to remain part of the county of Cambridgeshire until the mid-1930s. This meant that Ye Olde Mitre, a pub located in a court hidden behind the buildings of the Place and the Garden, was licensed by the Cambridgeshire Magistrates.[17][18] St Etheldreda's is the oldest Roman Catholic church in Britain, and one of two extant buildings in London dating back to the era of Edward I.[19][20][21]

Hatton Garden, the centre of the diamond trade, was leased to a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I, Sir Christopher Hatton, at the insistence of the Queen to provide him with an income. Behind the Prudential Building lies the Anglo-Catholic church of St Alban the Martyr.[22] Originally built in 1863 by architect William Butterfield, it was gutted during the Blitz but later reconstructed, retaining Butterfield's west front. The current[when?] vicar is Rev. Christopher Smith.[22]

On Holborn Circus lies the Church of St Andrew, an ancient Guild Church that survived the Great Fire of London. However, the parochial authority decided to commission Sir Christopher Wren to rebuild it. Although the nave was destroyed in the Blitz, the reconstruction was faithful to Wren's original. Just to the west of the circus, but originally sited in the middle, is a large equestrian statue of Prince Albert by Charles Bacon, erected in 1874 as the city's official monument to him. It was presented by Charles Oppenheim, of the diamond trading company De Beers, whose headquarters is in nearby Charterhouse Street.

In the early 21st century, Holborn has become the site of new offices and hotels. For example, the old neoclassical Pearl Assurance building near the junction with Kingsway was converted into a hotel in 1999.

There has been a limited attempt by some commercial organisations to rebrand Holborn (and perhaps other nearby areas such as Bloomsbury) as "Midtown", on the grounds that it is notionally in the very middle of London, between the West End and the City (often considered, such as for postcode purposes, to be on the east side of central London),[23] but this Americanisation has been widely criticised and not accepted by Londoners.

Education

- City Lit adult education

Geography

The now buried River Fleet formed the traditional eastern boundary of the Ancient Parish of Holborn, a course now marked by Farringdon Street, Farringdon Road and other streets.[24] The northern boundary with St Pancras was formed by a tributary of the Fleet later known as Lamb’s Conduit. [25]

Nearby areas

Transport

The nearest London Underground stations are Chancery Lane and Holborn. The closest mainline railway station is City Thameslink.

Holborn is served by bus routes 1, 8, 19, 25, 38, 55, 59, 68, 76, 91, 98, 168, 171, 188, 243, 341, 521, X68 and night routes N1, N8, N19, N38, N41, N55, N68 and N171.

Notable people

The following is a list of notable people who were born in or are significantly connected with Holborn.

- John Barbirolli, conductor, was born in Southampton Row (blue plaque on hotel his father managed).

- Thomas Chatterton (1752–1770), poet, was born in Bristol and died in a garret in Holborn at the age of 17.

- Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), composer, born at 15 Theobalds Road; acclaimed especially for The Song of Hiawatha trilogy.

- James Day (1850–1895), cricketer, was born in Holborn.

- Charles Dickens lived in Doughty Street, where his house is now a museum.

- Rupert Farley, actor and voice actor, was born in Holborn.

- Naomi Lewis (1911–2009), advocate of animal rights, poet, children's author and teacher, lived in Red Lion Square 1935–2009.

- Eric Morley (1918–2000), founder of the Miss World pageant, was born in Holborn.

- Pedro Perera (1832–1915), first-class cricketer

- Frederico Perera (1836–1909), first-class cricketer

- Ann Radcliffe (1764–1823), novelist and renowned author of the Gothic novel, was born in Holborn.

- John Shaw Jr. (1803–1870), architect, was born in Holborn; praised as a designer in the "Manner of Wren".

- Barry Sheene (1950–2003), World Champion motorcycle racer, spent his early years in Holborn.

- William Morris (1845–1896), artist and socialist, lived at 8 Red Lion Square.

- Matthew Ball, Principal Dancer with the Royal Ballet lives there.

Gallery

-

The headquarters of Sainsbury's at Holborn Circus

-

Grange Holborn Hotel

-

Entrance to Gray's Inn

-

Royal London Fusiliers Monument on Holborn, dedicated to those who died in World War I

See also

Notes

- a. ^ Pronunciation: The authoritative BBC pronunciation unit recommends "ˈhəʊbə(r)n" but allows "sometimes also hohl-buhrn". The organisation's less formal Pronouncing British Placenames notes, "You'll occasionally find towns where nobody can agree.... Holborn in central London has for many years been pronounced 'hoe-bun', but having so few local residents to preserve this, it's rapidly changing to a more natural 'hol-burn'".[26][27] However, Modern British and American English pronunciation (2008) cites "Holborn" as one of its examples of a common word where the "l" is silent.[28] The popular tourist guide The Rough Guide to Britain sticks to the traditional form, with neither "l" nor "r": /ˈhoʊbən/ HOH-bən.[29]

References

- ^ "Camden Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ https://www3.camden.gov.uk/westendproject/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Project-Overview-for-website-1.pdf LBC website describing improvements in a part of the borough they refer to as 'West End'

- ^ 'West of Farringdon Road', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), pp. 22-51. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp22-51 [accessed 31 July 2020].

- ^ a b Lethaby, William (1902). London before the conquest. London: Macmillan. p. 60.

- ^ a b Besant, Walter; Mitton, Geraldine (1903). Holborn and Bloomsbury. The Fascination of London (Project Gutenberg, 2007 ed.). London: Adam and Charles Black. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Shepherd, William R (1926). Historical atlas (3 ed.). University of London. p. 75. OCLC 253088196.

- ^ Strype, John (1720). "Rivers and other Waters serving this City". Survey of London. The Stuart London Project. Online edition: University of Sheffield 2007.

- ^ "เว็บถ่ายทอดสดออนไลน์คาสิโน – รับข่าวสารข้อมูลที่ชวนรู้ทุกที่". www.oldlondonmaps.com.

- ^ Lethaby (1902:48)

- ^ Harben, Henry (1918). A Dictionary of London. London: Herbert Jenkins.

- ^ The Parish of St Andrew Holborn pp. 11–12 Caroline Barron London 1979

- ^ Timbs, John (1855). Curiosities of London: Exhibiting the Most Rare and Remarkable Objects of Interest in the Metropolis. D. Bogue. p. 428.

- ^ The World, the Flesh and the Devil at IMDb

- ^ The full-length documentary With Our King and Queen Through India, also in Kinemacolor, premièred in February 1912, and the stencil-coloured The Miracle opened at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in December 1912.

- ^ Chap. 20

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher; et al. (1983). The London Encyclopedia (2010 ed.). London: MacMillan. p. 397. ISBN 1-4050-4925-1.

- ^ Vitaliev, Vitali (3 January 2003). "Things that go bump on the map". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ^ Hammond, Derek (28 June 2006). "Secret London: Ye Olde Mitre Tavern". Time Out. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- ^ "History of the Church". stetheldreda.com.

It is the oldest Catholic church in England and one of only two remaining buildings in London from the reign of Edward I.

- ^ Sarah Kettler; Carole Trimble (2001). The Amateur Historian's Guide to Medieval and Tudor London, 1066–1600. Capital Books. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-892123-32-9.

This is Britain's oldest Roman Catholic church, dating from the 13th century.

- ^ Andrew Davies (1988). Literary London. Pan Macmillan. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-333-45708-5.

In 1874 when the church was bought back by the Roman Catholics it was found to be full of 'inconceivable filth, living and dead'. St Etheldreda's is the oldest Catholic church building in Britain.

- ^ a b St Alban the Martyr accessed 14 December 2013

- ^ Colvile, Robert (27 June 2012). "A Midtown in London? There's NoHo chance" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ 'West of Farringdon Road', in Survey of London: Volume 47, Northern Clerkenwell and Pentonville, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), pp. 22-51. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol47/pp22-51 [accessed 31 July 2020].

- ^ The History of the River Fleet, UCL Fleet Restoration Team, 2009

- ^ Olausson, Lena (2006). "Holborn". Oxford BBC Guide to Pronunciation, The Essential Handbook of the Spoken Word (3rd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 173. ISBN 0-19-280710-2.

- ^ "Pronouncing British Placenames". BBC. 7 March 2007. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Dretzke, Burkhard (2008). Modern British and American English pronunciation. Paderborn, Germany: Ferdinand Schöningh. p. 63. ISBN 3-8252-2053-2.

- ^ Roberts, Andrew; Matthew Teller (2004). The Rough Guide to Britain. London: Rough Guides Ltd. p. 109. ISBN 1-84353-301-4.

External links

- Holborn and Bloomsbury, by Sir Walter Besant and Geraldine Edith Mitton, 1903, from Project Gutenberg