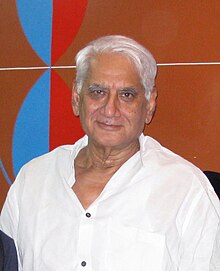

Charles Correa

Charles Correa (born Charles Mark Correa) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1 September 1930 Secunderabad, Hyderabad State |

| Died | 16 June 2015 (aged 84) Mumbai, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Alma mater | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Michigan |

| Occupation(s) | Architect, urban planner and activist |

| Buildings | Jawahar Kala Kendra, National Crafts Museum, Bharat Bhavan |

Charles Correa (born Charles Mark Correa; 1 September 1930 – 16 June 2015) was an Indian architect, urban planner and activist. Credited for the creation of modern architecture in post-Independence India, he was celebrated for his sensitivity to the needs of the urban poor and for his use of traditional methods and materials. [1]

He was awarded the Padma Shri in 1972, and the second highest civilian honour, the Padma Vibhushan given by Government of India in 2006. He was also awarded the 1984 Royal Gold Medal for architecture, by the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Early life and education

Correa was born on 1 September 1930 in Secunderabad,.[2][3]

Correa began his higher studies at St. Xavier's College, Mumbai at the University of Bombay (now Mumbai) went on to study at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor (1949–53) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1953–55). In 1958 he established his own Mumbai based professional practice.[4] He died on 16 June 2015 in Mumbai following a brief illness.[5]

Career

Correa was a major figure in contemporary architecture around the world. With his extraordinary and inspiring designs, he played a pivotal role in the creation of an architecture for post-Independence India. All of his work – from the carefully detailed memorial Mahatma Gandhi Memorial Museum at the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad to Kanchanjunga Apartment tower in Mumbai, the Jawahar Kala Kendra in Jaipur, the planning of Navi Mumbai, MIT's Brain and Cognitive Sciences Centre in Cambridge, and most recently, the Champalimad Centre for the Unknown in Lisbon, places special emphasis on prevailing resources, energy and climate as major determinants in the ordering of space. He designed the Parumala Church as well.

His first important project was "Mahatma Gandhi Sangrahalaya" (Mahatma Gandhi Memorial) at Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad (1958–1963),[6] then in 1967 he designed the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly in Bhopal.[7] He also designed the distinctive buildings of National Crafts Museum, New Delhi (1975–1990), Bharat Bhavan, Bhopal (1982), Jawahar Kala Kendra (Jawahar Arts Centre), in Jaipur, Rajasthan (1986–1992), British Council, Delhi, (1987–92) the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, Boston (2000–2005), City Centre (Salt Lake City, Kolkata) in Kolkata (2004) and the Champalimaud Centre for The Unknown in Lisbon, Portugal (2007–2010).[6]

Also he designed state-of-the-art research and development facility of Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd (Mahindra Research Valley)at Chennai, which is the epicentre of various R&D networks of Mahindra & Mahindra Ltd.

From 1970–75, he was Chief Architect for New Bombay (Navi Mumbai), an urban growth center of 2 million people across the harbour from the existing city of Mumbai, here along with Shirish Patel and Pravina Mehta he was involved in extensive urban planning of the new city.[8] In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi appointed him Chairman of the National Commission on Urbanization.

In 1984, he founded the Urban Design Research Institute in Bombay, dedicated to the protection of the built environment and improvement of urban communities. During the final four decades of his life, Correa has done pioneering work in urban issues and low-cost shelter in the Third World.

From 2005 until his 2008 resignation Correa was the Chairman of the Delhi Urban Arts Commission.

On 18 December 2011, the eve of the Golden Jubiliee of Liberation of Goa, Correa was bestowed with Goa's highest civilian honour, the Gomant Vibhushan.[9]

In 2013, the Royal Institute of British Architects held an retrospective exhibition, "Charles Correa – India's Greatest Architect", about the influences his work on modern urban Indian architecture.[8][10]

Last

One of Correa's most important later projects is the new Ismaili Centre in Toronto, Canada which is located in the midst of formal gardens and surrounded by a large park designed by landscape architect Vladimir Djurovic. It shares the site with the Aga Khan Museum designed by Fumihiko Maki.[11]

The Champalimaud Foundation Centre in Lisbon was inaugurated on 5 October 2010 by the Portuguese President, Cavaco Silva.[12][13]

Awards

- RIBA Royal Gold Medal – 1984.[14]

- Padma Vibhushan (2006) and Padma Shri (1972).[15]

- Praemium Imperiale (1994)

- 7th Aga Khan Award for Architecture for Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly (1998)[7]

- Austrian Decoration for Science and Art (2005)[16]

See also

- Sheila Sri Prakash

- Dharmesh Popat

- Geoffrey Bawa

- Muzharul Islam

- B.V. Doshi

- Raj Rewal

- Bashirul Haq

- Kaku Sheth

References

- ^ An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ "Charles Correa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, James Belluardo (1998), An Architecture of Independence: The Making of Modern South Asia, Architectural League of New York, p. 33, ISBN 09663-8560-8, ISBN 9780966385601

- ^ "Charles Correa, Britannica".

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b "Charles Correa – India's greatest architect?". BBC News. 13 May 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ a b Vidhan Bhavan, (ArchNet)

- ^ a b "Master class with Charles Correa". Mumbai Mirror. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "CharlesCorrea, Gomant Vibhushan". The Times of India. 19 December 2011.

- ^ "Charles Correa & Out of India Season". RIBA. 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ^ "Correa, Maki Tapped to Design Aga Khan Center". Architectural Record, The McGraw-Hill Companies. 6 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Profile, fchampalimaud.org; accessed 31 October 2015.

- ^ The Champalimaud Foundation – Arquitetura Lisboa, e-architect.co.uk; accessed 31 October 2015.

- ^ "List of medal winners 1848–2008 (PDF)" (PDF). RIBA. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Padma Awards Directory (1954–2009)" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (pdf) (in German). p. 1714. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

Further reading

External links

- 1930 births

- 2015 deaths

- Disease-related deaths in India

- People of Goan descent

- Indian architects

- St. Xavier's College, Mumbai alumni

- University of Michigan alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- Postmodern architecture in India

- Urban designers

- Indian urban planners

- Recipients of the Padma Shri in science & engineering

- Recipients of the Padma Vibhushan in science & engineering

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale

- Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- 20th-century Indian architects

- People from Secunderabad