Crystal City, Texas

Crystal City, Texas | |

|---|---|

Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Crystal City | |

| Nickname: Spinach Capital of the World | |

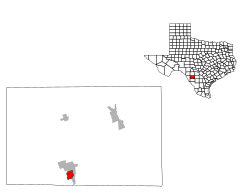

Location of Crystal City, Texas | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Zavala |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vacant |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.6 sq mi (9.4 km2) |

| • Land | 3.6 sq mi (9.4 km2) |

| • Water | 0.0 sq mi (0.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 558 ft (170 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

• Total | 7,138 |

• Estimate (2014)[1] | 7,513 |

| • Density | 2,000/sq mi (760/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 78839 |

| Area code | 830 |

| FIPS code | 48-18020[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1355449[3] |

| Website | City Website |

Crystal City is a city in and the county seat of Zavala County, Texas, United States.[4] The population was 7,138 at the 2010 census.

History

Farming, ranching, railroad

Crystal City was originally settled by American farmers and ranchers producing cattle and various crops. Crystal City, along with San Antonio, Uvalde, Carrizo Springs, and Corpus Christi, was a major stop on the defunct San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Railroad, which operated from 1909 until it was merged into the Missouri Pacific Railroad in 1956. From 1909 to 1912, the SAU&G was known as the Crystal City and Uvalde Railroad. There was also an eastern link to Fowlerton near Cotulla in La Salle County. The remaining San Antonio-to-Corpus Christi route is now under the Union Pacific system.[5]

The successful production of spinach evolved into a dominant industry. By March 26, 1937, the growers had erected a statue of the cartoon character Popeye in the town because his reliance on spinach for strength led to greater popularity for the vegetable, which had become a staple cash crop of the local economy. See the Popeye statue web entry. Early in its history, the area known as the "Winter Garden District" was deemed the "Spinach Capital of the World" (a title contested by Alma, Arkansas). The first Spinach Festival was held in 1936. It was put on hold during World War II and later years. The Festival was resumed in 1982. The Spinach Festival is traditionally held on the second weekend in November, and draws former residents (many of them former migrant farm workers) from Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, Washington State, and beyond.

Internment camp

During World War II, Crystal City was home to the largest of the World War II internment camps, having housed American civilians of German, Japanese, and Italian ancestry.

Political activism

With the stream of refugees fleeing the Mexican Revolution of 1911, and later added to by Mexican migrant workers lured by the local spinach industry, the demographics of the small rural city began to shift over the years since its 1910 incorporation, due to its proximity to the U.S./Mexico border. By 1963, Crystal City experienced a tumultuous Mexican-American electoral victory, as the swiftly emerging Mexican-American majority elected fellow Mexican-Americans to the city council, led by Juan Cornejo, a local representative of the Teamsters Union at the Del Monte cannery in Crystal City. The newly elected all-Mexican-American city council, and the succeeding administration, had trouble governing the city because of political factions among the new officials. Cornejo was selected mayor from among the five new council members. His ongoing quest for ultimate control of the city government, however, eventually led to his loss of political support. Although these five elected officials known as "Los Cinco" only held office for two years, many consider this moment the "spark" or starting point of what became known as the Chicano Movement. Texas Governor Briscoe referred to Crystal City as "Little Cuba." See the Crystal City Revolts History Entry. A new group made up of both Anglos and Mexican-Americans, the Citizens Association Serving All Americans, announced its plans to run candidates for countywide offices in 1964, and won.[citation needed]

La Raza Unida Party

By the late 1960s, Crystal City would become the location of continued activism in the civil rights movement among its Mexican-American majority population, and the birthplace of the third party political movement known as La Raza Unida Party founded by three Chicanos, including José Ángel Gutiérrez over a conflict about the ethnicity of cheerleaders at Crystal City High School. 200 Mexican-American students went out on strike with their parents' support. La Raza Unida, and related organizations, then won election to most offices in Crystal City and Zavala County in the periods between 1969 and 1980, when the party declined at the local level. See the Handbook of Texas History Entry

In the 1970s, following protests of charges (essentially non-payment of services) on the part of La Raza Unida, Crystal City's natural gas supply was shut off by its only supplier. Crystal City residents were forced to resort to mostly wood burning stoves and individual propane gas tanks for cooking. To this day, there is no natural gas supplier in the Crystal City area, although most residents purchase propane from the city.[citation needed]

1976 indictments

In 1976, eleven officials in Crystal City were indicted on various counts. Angel Noe Gonzalez, the former Crystal City Independent School District superintendent who later worked in the United States Department of Education in Washington, D.C., upon his indictment retained the San Antonio lawyer and later mayor, Phil Hardberger. Gonzalez was charged with paying Adan Cantu for doing no work. Hardberger, however, documented to the court specific duties that Cantu had performed and disputed all the witnesses called against Cantu. The jury unanimously acquitted Gonzalez. Many newspapers reported on the indictments but not on the acquittal. John Luke Hill, the 1978 Democratic gubernatorial nominee, had sought to weaken La Raza Unida so that he would not lose general election votes to a third party candidate. Victory, however, went not to Hill but narrowly to his successful Republican rival, Bill Clements. Compean received only 15,000 votes, or 0.6 percent, just under Clements's 17,000-vote plurality over Hill.[6]

Political corruption

In February 2016, almost every top official of the city was arrested under a federal indictment accusing them of taking bribes from contractors and providing city workers to assist an illegal gambling operator, Ngoc Tri Nguyen. Mayor Ricardo Lopez, city attorney William Jonas, Mayor Pro Tempore Rogelio Mata, council member Roel Mata. and former council member Gilbert Urrabazo. A second councilman, Marco Rodriguez was already charged in a separate case with smuggling Mexican immigrants. That leaves one councilman free of federal charges. A week earlier Lopez was taken into custody for assault and disorderly conduct during a city council meeting in which a recall election to remove himself and two other city council members was discussed. In December, Jonas surrendered to authorities after being charged with assault for allegedly manhandling an elderly woman who was trying to enter a city council meeting.[7][8]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.6 square miles (9.4 km²), all of it land. Major bodies of water near Crystal City include the Nueces River and Averhoff Reservoir. Soils are well drained reddish brown to grayish brown sandy loam or clay loam of the Brystal, Pryor and Tonio series; the Brystal is neutral to mildly alkaline and the other two tend to be moderately alkaline.[9] [10][11] [12]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 6,609 | — | |

| 1940 | 6,529 | −1.2% | |

| 1950 | 7,198 | 10.2% | |

| 1960 | 9,101 | 26.4% | |

| 1970 | 8,104 | −11.0% | |

| 1980 | 8,334 | 2.8% | |

| 1990 | 8,263 | −0.9% | |

| 2000 | 7,190 | −13.0% | |

| 2010 | 7,138 | −0.7% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 7,513 | [1] | 5.3% |

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 7,190 people, 2,183 households, and 1,781 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,974.1 people per square mile (762.7/km²). There were 2,500 housing units at an average density of 686.4 per square mile (265.2/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 67.96% White, 0.67% African American, 0.39% Native American, 0.10% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 28.33% from other races, and 2.50% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 94.97% of the population.

There were 2,183 households out of which 43.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 51.9% were married couples living together, 25.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 18.4% were non-families. 16.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.25 and the average family size was 3.67.

In the city the population was spread out with 34.9% under the age of 18, 9.6% from 18 to 24, 24.2% from 25 to 44, 18.7% from 45 to 64, and 12.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 29 years. For every 100 females there were 91.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $15,400, and the median income for a family was $17,555. Males had a median income of $22,217 versus $14,591 for females. The per capita income for the city was $8,899. About 39.8% of families and 44.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 51.3% of those under age 18 and 43.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

The Crystal City Correctional Center, a private prison, is in the Crystal City area.

South of Crystal City on U.S. Highway 83 is Ecoloclean Industries, founded in 2001. The company engages in the manufacture and sale of machines for the treatment of contaminated water. In 2005, the company was retained by officials in Biloxi, Mississippi, to provide drinking water to Hurricane Katrina victims and to establish water remediation needed in the aftermath of the storm along the Mississippi Gulf Coast.[14]

Education

Crystal City is served by the Crystal City Independent School District. The high school teams are known as the Javelinas.

There is also a branch of Southwest Texas Junior College, of which the main campus is to the north in Uvalde.

References

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ "Nancy Beck Young, "San Antonio, Uvalde and Gulf Railroad Company"". Texas State Historical Association on-line. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- ^ Rick Casey, "Not first time La Raza Unida has been blamed", San Antonio Express-News, February 13, 2016, p. A19

- ^ Federal Corruption Case Snares Leaders of South Texas City; ABC News; February 4, 2016.

- ^ Almost every top official in Texas city arrested in federal corruption case; Fox News; February 5, 2016.

- ^ http://casoilresource.lawr.ucdavis.edu/gmap/

- ^ https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/b/brystal.html

- ^ https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/p/pryor.html

- ^ https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/t/tonio.html

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Ecoloclean Industries, Inc. Hires Assistant Vice President of Capital Sourcing, February 2005". thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

Further reading

- Bosworth, Allan R. (1967), America's Concentration Camps, New York: Norton.

- Connell, Thomas. (2002). America's Japanese Hostages: The US Plan For A Japanese Free Hemisphere. [1] Westport: Praeger-Greenwood. ISBN 9780275975357; OCLC 606835431

- Fox, Stephen, America's Invisible Gulag, A Biography of German American Internment and Exclusion in World War II. Morehouse Pub, 2000, 379 pp.

- Miller, Michael V. "Chicano Community Control in South Texas: Problems And Prospects," Journal of Ethnic Studies (1975) 3#3 pp 70–89.

- Jensen, Richard J. and John C. Hammerback, "Radical Nationalism Among Chicanos: The Rhetoric of José Angel Gutiérrez," Western Journal of Speech Communication: WJSC (1980) 44#3 pp 191–202

- Navarro, Armando. The Cristal Experiment: A Chicano Struggle for Community Control (University of Wisconsin Press, 1998)

- Riley, Karen L. Schools behind Barbed Wire: The Untold Story of Wartime Internment and the Children of Arrested Enemy Aliens (2002).

- Russell, Jan Jarboe (2015), The Train to Crystal City: FDR's Secret Prisoner Exchange and America's Only Family Internment Camp during World War II, Waterville, ME: Thorndike Press.

- Shockley, John Staples. Chicano Revolt in a Texas Town (1974), [detailed narrative of 1960s and 1970s].