Hawaii

Hawaii

Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian) | |

|---|---|

| State of Hawaii Mokuʻāina o Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian) | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Anthem: Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī (Hawaiʻi's Own True Sons)[4] | |

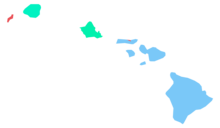

Map of the United States with Hawaii highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Territory of Hawaii |

| Admitted to the Union | August 21, 1959 (50th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Honolulu |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Honolulu |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Josh Green (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Sylvia Luke (D) |

| Legislature | State Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court of Hawaii |

| U.S. senators |

|

| U.S. House delegation | 1: Ed Case (D) 2: Jill Tokuda (D) (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10,931 sq mi (28,311 km2) |

| • Land | 6,423 sq mi (16,638 km2) |

| • Water | 4,507 sq mi (11,672 km2) 41.2% |

| • Rank | 43rd |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 1,522 mi (2,450 km) |

| • Width | n/a mi (n/a km) |

| Elevation | 3,030 ft (920 m) |

| Highest elevation | 13,796 ft (4,205.0 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Pacific Ocean[6]) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 1,455,271 |

| • Rank | 40th |

| • Density | 221/sq mi (82.6/km2) |

| • Rank | 13th |

| • Median household income | $83,200[7] |

| • Income rank | 6th |

| Demonym(s) | Hawaii resident,[8] Hawaiian[c] |

| Language | |

| • Official languages | |

| Time zone | UTC−10:00 (Hawaii) |

| USPS abbreviation | HI |

| ISO 3166 code | US-HI |

| Traditional abbreviation | H.I. |

| Latitude | 18° 55′ N to 28° 27′ N |

| Longitude | 154° 48′ W to 178° 22′ W |

| Website | hawaii |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Nene |

| Fish | Humuhumunukunukuāpuaʻa |

| Flower | Pua aloalo |

| Insect | Pulelehua |

| Tree | Kukui tree |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Dance | Hula |

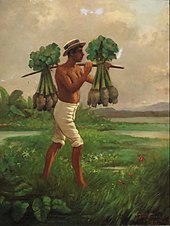

| Food | Kalo (taro) |

| Gemstone | ʻĒkaha kū moana (black coral) |

| Sport | Heʻe nalu (surfing) |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2008 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Hawaii (/həˈwaɪ.i/ hə-WY-ee;[9] Hawaiian: Hawaiʻi [həˈvɐjʔi, həˈwɐjʔi]) is an island state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about 2,000 miles (3,200 km) southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two non-contiguous U.S. states (alongside Alaska), it is the only state not on the North American mainland, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state in the tropics.

Hawaii consists of 137 volcanic islands that comprise almost the entire Hawaiian archipelago (the exception, which is outside the state, is Midway Atoll). Spanning 1,500 miles (2,400 km), the state is physiographically and ethnologically part of the Polynesian subregion of Oceania.[10] Hawaii's ocean coastline is consequently the fourth-longest in the U.S., at about 750 miles (1,210 km).[d] The eight main islands, from northwest to southeast, are Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Maui, and Hawaiʻi, after which the state is named; the latter is often called the "Big Island" or "Hawaii Island" to avoid confusion with the state or archipelago. The uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands make up most of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, the largest protected area in the U.S. and the fourth-largest in the world.

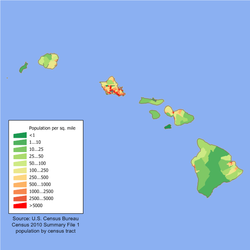

Of the 50 U.S. states, Hawaii is the eighth-smallest in land area and the 11th-least populous; but with 1.4 million residents, it ranks 13th in population density. Two-thirds of Hawaii residents live on O'ahu, home to the state's capital and largest city, Honolulu. Hawaii is among the country's most demographically diverse states, owing to its central location in the Pacific and over two centuries of migration. As one of only seven majority-minority states, it has the only Asian American plurality, the largest Buddhist community,[11] and largest proportion of multiracial people in the U.S.[12] Consequently, Hawaii is a unique melting pot of North American and East Asian cultures, in addition to its indigenous Hawaiian heritage.

Settled by Polynesians sometime between 1000 and 1200 CE, Hawaii was home to numerous independent chiefdoms.[13] In 1778, British explorer James Cook was the first known non-Polynesian to arrive at the archipelago; early British influence is reflected in the state flag, which bears a Union Jack. An influx of European and American explorers, traders, and whalers soon arrived, leading to the decimation of the once-isolated indigenous community through the introduction of diseases such as syphilis, tuberculosis, smallpox, and measles; the native Hawaiian population declined from between 300,000 and one million to less than 40,000 by 1890.[14][15][16] Hawaii became a unified, internationally recognized kingdom in 1810, remaining independent until American and European businessmen overthrew the monarchy in 1893; this led to annexation by the U.S. in 1898. As a strategically valuable U.S. territory, Hawaii was attacked by Japan on December 7, 1941, which brought it global and historical significance, and contributed to America's entry into World War II. Hawaii is the most recent state to join the union, on August 21, 1959.[17] In 1993, the U.S. government formally apologized for its role in the overthrow of Hawaii's government, which had spurred the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and has led to ongoing efforts to obtain redress for the indigenous population.

Historically dominated by a plantation economy, Hawaii remains a major agricultural exporter due to its fertile soil and uniquely tropical climate in the U.S. Its economy has gradually diversified since the mid-20th century, with tourism and military defense becoming the two largest sectors. The state attracts visitors, surfers, and scientists with its diverse natural scenery, warm tropical climate, abundant public beaches, oceanic surroundings, active volcanoes, and clear skies on the Big Island. Hawaii hosts the United States Pacific Fleet, the world's largest naval command, as well as 75,000 employees of the Defense Department.[18] Hawaii's isolation results in one of the highest costs of living in the U.S. However, Hawaii is the third-wealthiest state,[18] and residents have the longest life expectancy of any U.S. state, at 80.7 years.[19]

Etymology

The State of Hawaii derives its name from the name of its largest island, Hawaiʻi. A common explanation of the name of Hawaiʻi is that it was named for Hawaiʻiloa, a figure from Hawaiian oral tradition. He is said to have discovered the islands when they were first settled.[20][21]

The Hawaiian language word Hawaiʻi is very similar to Proto-Polynesian Sawaiki, with the reconstructed meaning "homeland."[e] Cognates of Hawaiʻi are found in other Polynesian languages, including Māori (Hawaiki), Rarotongan (ʻAvaiki) and Samoan (Savaiʻi). According to linguists Pukui and Elbert,[23] "elsewhere in Polynesia, Hawaiʻi or a cognate is the name of the underworld or of the ancestral home, but in Hawaii, the name has no meaning".[24]

Spelling of state name

In 1978, Hawaiian was added to the Constitution of the State of Hawaii as an official state language alongside English.[25] The title of the state constitution is The Constitution of the State of Hawaii. Article XV, Section 1 of the Constitution uses The State of Hawaii.[26] Diacritics were not used because the document, drafted in 1949,[27] predates the use of the ʻokina ⟨ʻ⟩ and the kahakō in modern Hawaiian orthography. The exact spelling of the state's name in the Hawaiian language is Hawaiʻi.[f] In the Hawaii Admission Act that granted Hawaiian statehood, the federal government used Hawaii as the state name. Official government publications, department and office titles, and the Seal of Hawaii use the spelling without symbols for glottal stops or vowel length.[28][better source needed]

Geography and environment

| Island | Nickname | Area | Population (as of 2020) |

Density | Highest point | Maximum elevation | Age (Ma)[29] | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hawaiʻi[30] | The Big Island | 4,028.0 sq mi (10,432.5 km2) | 200,629 | 49.8/sq mi (19.2/km2) | Mauna Kea | 13,796 ft (4,205 m) | 0.4 | 19°34′N 155°30′W / 19.567°N 155.500°W |

| Maui[31] | The Valley Isle | 727.2 sq mi (1,883.4 km2) | 164,221 | 225.8/sq mi (87.2/km2) | Haleakalā | 10,023 ft (3,055 m) | 1.3–0.8 | 20°48′N 156°20′W / 20.800°N 156.333°W |

| Oʻahu[32] | The Gathering Place | 596.7 sq mi (1,545.4 km2) | 1,016,508 | 1,703.5/sq mi (657.7/km2) | Mount Kaʻala | 4,003 ft (1,220 m) | 3.7–2.6 | 21°28′N 157°59′W / 21.467°N 157.983°W |

| Kauaʻi[33] | The Garden Isle | 552.3 sq mi (1,430.5 km2) | 73,298 | 132.7/sq mi (51.2/km2) | Kawaikini | 5,243 ft (1,598 m) | 5.1 | 22°05′N 159°30′W / 22.083°N 159.500°W |

| Molokaʻi[34] | The Friendly Isle | 260.0 sq mi (673.4 km2) | 7,345 | 28.3/sq mi (10.9/km2) | Kamakou | 4,961 ft (1,512 m) | 1.9–1.8 | 21°08′N 157°02′W / 21.133°N 157.033°W |

| Lānaʻi[35] | The Pineapple Isle | 140.5 sq mi (363.9 km2) | 3,367 | 24.0/sq mi (9.3/km2) | Lānaʻihale | 3,366 ft (1,026 m) | 1.3 | 20°50′N 156°56′W / 20.833°N 156.933°W |

| Niʻihau[36] | The Forbidden Isle | 69.5 sq mi (180.0 km2) | 84 | 1.2/sq mi (0.5/km2) | Mount Pānīʻau | 1,250 ft (381 m) | 4.9 | 21°54′N 160°10′W / 21.900°N 160.167°W |

| Kahoʻolawe[37] | The Target Isle | 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) | 0 | 0/sq mi (0/km2) | Puʻu Moaulanui | 1,483 ft (452 m) | 1.0 | 20°33′N 156°36′W / 20.550°N 156.600°W |

There are eight main Hawaiian islands. Seven are inhabited, but only six are open to tourists and locals. Niʻihau is privately managed by brothers Bruce and Keith Robinson; access is restricted to those who have their permission. This island is also home to native Hawaiians. Access to uninhabited Kahoʻolawe island is also restricted and anyone who enters without permission will be arrested. This island may also be dangerous since it was a military base during the world wars and could still have unexploded ordnance.

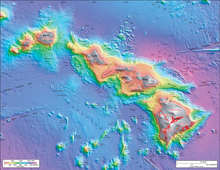

Topography

The Hawaiian archipelago is 2,000 mi (3,200 km) southwest of the contiguous United States.[38] Hawaii is the southernmost U.S. state and the second westernmost after Alaska. Like Alaska, Hawaii borders no other U.S. state. It is the only U.S. state not in North America, and the only one completely surrounded by water and entirely an archipelago.

In addition to the eight main islands, the state has many smaller islands and islets. Kaʻula is a small island near Niʻihau. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is a group of nine small, older islands northwest of Kauaʻi that extends from Nihoa to Kure Atoll; these are remnants of once much larger volcanic mountains. Across the archipelago are around 130 small rocks and islets, such as Molokini, which are made up of either volcanic or marine sedimentary rock.[39]

Hawaiʻi's tallest mountain Mauna Kea is 13,796 ft (4,205 m) above mean sea level;[40] it is taller than Mount Everest if measured from the base of the mountain, which lies on the floor of the Pacific Ocean and rises about 33,500 feet (10,200 m).[41]

Geology

The Hawaiian islands were formed by volcanic activity initiated at an undersea magma source called the Hawaiʻi hotspot. The process is continuing to build islands; the tectonic plate beneath much of the Pacific Ocean continually moves northwest and the hotspot remains stationary, slowly creating new volcanoes. Because of the hotspot's location, all active land volcanoes are on the southern half of Hawaiʻi Island. The newest volcano, Kamaʻehuakanaloa (formerly Lōʻihi), is south of the coast of Hawaiʻi Island.

The last volcanic eruption outside Hawaiʻi Island occurred at Haleakalā on Maui before the late 18th century, possibly hundreds of years earlier.[42] In 1790, Kīlauea exploded; it is the deadliest eruption known to have occurred in the modern era in what is now the United States.[43] Up to 5,405 warriors and their families marching on Kīlauea were killed by the eruption.[44] Volcanic activity and subsequent erosion have created impressive geological features. Hawaii Island has the second-highest point among the world's islands.[45]

On the volcanoes' flanks, slope instability has generated damaging earthquakes and related tsunamis, particularly in 1868 and 1975.[46] Catastrophic debris avalanches on the ocean island volcanoes' submerged flanks have created steep cliffs.[47][48]

Kīlauea erupted in May 2018, opening 22 fissure vents on its eastern rift zone. The Leilani Estates and Lanipuna Gardens are within this territory. The eruption destroyed at least 36 buildings and this, coupled with the lava flows and the sulfur dioxide fumes, necessitated the evacuation of more than 2,000 inhabitants from their neighborhoods.[49]

Flora and fauna

The islands of Hawaiʻi are distant from other land habitats, and life is thought to have arrived there by wind, waves (i.e., by ocean currents), and wings (i.e., birds, insects, and any seeds that they may have carried on their feathers). Hawaiʻi has more endangered species and has lost a higher percentage of its endemic species than any other U.S. state.[50] The endemic plant Brighamia now requires hand pollination because its natural pollinator is presumed to be extinct.[51] The two species of Brighamia—B. rockii and B. insignis—are represented in the wild by around 120 individual plants. To ensure that these plants set seed, biologists rappel down 3,000-foot (910 m) cliffs to brush pollen onto their stigmas.[52]

Terrestrial ecology

The archipelago's extant main islands have been above the surface of the ocean for less than 10 million years, a fraction of the time biological colonization and evolution have occurred there. The islands are well known for the environmental diversity that occurs on high mountains within a trade winds field. Native Hawaiians developed complex horticultural practices to utilize the surrounding ecosystem for agriculture. Cultural practices developed to enshrine values of environmental stewardship and reciprocity with the natural world, resulting in widespread biodiversity and intricate social and environmental relationships that persist to this day.[53] On a single island, the climate around the coasts can range from dry tropical (less than 20 inches or 510 millimeters annual rainfall) to wet tropical; on the slopes, environments range from tropical rainforest (more than 200 inches or 5,100 millimeters per year), through a temperate climate, to alpine conditions with a cold, dry climate. The rainy climate impacts soil development, which largely determines ground permeability, affecting the distribution of streams and wetlands.[54][55][56]

Protected areas

Several areas in Hawaiʻi are under the National Park Service's protection.[57] Hawaii has two national parks: Haleakalā National Park, near Kula on Maui, which features the dormant volcano Haleakalā that formed east Maui; and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, in the southeast region of Hawaiʻi Island, which includes the active volcano Kīlauea and its rift zones.

There are three national historical parks: Kalaupapa National Historical Park in Kalaupapa, Molokaʻi, the site of a former leper colony; Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park in Kailua-Kona on Hawaiʻi Island; and Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, an ancient place of refuge on Hawaiʻi Island's west coast. Other areas under the National Park Service's control include Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail on Hawaiʻi Island and the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor on Oʻahu.

President George W. Bush proclaimed the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument on June 15, 2006. The monument covers roughly 140,000 square miles (360,000 km2) of reefs, atolls, and shallow and deep sea out to 50 miles (80 km) offshore in the Pacific Ocean—an area larger than all the national parks in the U.S. combined.[58]

Climate

Hawaiʻi has a tropical climate. Temperatures and humidity tend to be less extreme because of near-constant trade winds from the east. Summer highs reach around 88 °F (31 °C) during the day, with lows of 75 °F (24 °C) at night. Winter day temperatures are usually around 83 °F (28 °C); at low elevation they seldom dip below 65 °F (18 °C) at night. Snow, not usually associated with the tropics, falls at 13,800 feet (4,200 m) on Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on Hawaii Island in some winter months. Snow rarely falls on Haleakalā. Mount Waiʻaleʻale on Kauaʻi has the second-highest average annual rainfall on Earth, about 460 inches (12,000 mm) per year. Most of Hawaii experiences only two seasons; the dry season runs from May to October and the wet season is from October to April.[60]

Overall with climate change, Hawaiʻi is getting drier and hotter.[61][62] The warmest temperature recorded in the state, in Pahala on April 27, 1931, is 100 °F (38 °C), tied with Alaska as the lowest record high temperature observed in a U.S. state.[63] Hawaiʻi's record low temperature is 12 °F (−11 °C) observed in May 1979, on the summit of Mauna Kea. Hawaiʻi is the only state to have never recorded subzero Fahrenheit temperatures.[63]

Climates vary considerably on each island; they can be divided into windward and leeward (koʻolau and kona, respectively) areas based upon location relative to the higher mountains. Windward sides face cloud cover.[64]

Environmental issues

Hawaii has a decades-long history of hosting more military space for the United States than any other territory or state.[65] This record of military activity has taken a sharp toll on the environmental health of the Hawaiian archipelago, degrading its beaches and soil, and making some places entirely unsafe due to unexploded ordnance.[66] According to scholar Winona LaDuke: "The vast militarization of Hawaii has profoundly damaged the land. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, there are more federal hazardous waste sites in Hawaii – 31 – than in any other U.S. state."[67] Hawaii State Representative Roy Takumi writes in "Challenging U.S. Militarism in Hawai'i and Okinawa" that these military bases and hazardous waste sites have meant "the confiscation of large tracts of land from native peoples" and quotes late Hawaiian activist George Helm as asking: "What is national defense when what is being destroyed is the very thing the military is entrusted to defend, the sacred land of Hawaiʻi?"[65] Contemporary Indigenous Hawaiians are still protesting the occupation of their homelands and environmental degradation due to increased militarization in the wake of 9/11.[68]

After the rise of sugarcane plantations in the mid 19th century, island ecology changed dramatically. Plantations require massive quantities of water, and European and American plantation owners transformed the land in order to access it, primarily by building tunnels to divert water from the mountains to the plantations, constructing reservoirs, and digging wells.[69] These changes have made lasting impacts on the land and continue to contribute to resource scarcity for Native Hawaiians today.[69][70]

According to Stanford scientist and scholar Sibyl Diver, Indigenous Hawaiians engage in a reciprocal relationship with the land, "based on principles of mutual caretaking, reciprocity and sharing".[71] This relationship ensures the longevity, sustainability, and natural cycles of growth and decay, as well as cultivating a sense of respect for the land and humility towards one's place in an ecosystem.[71]

The tourism industry's ongoing expansion and its pressure on local systems of ecology, cultural tradition and infrastructure is creating a conflict between economic and environmental health.[72] In 2020, the Center for Biological Diversity reported on the plastic pollution of Hawaii's Kamilo beach, citing "massive piles of plastic waste".[73] Invasive species are spreading, and chemical and pathogenic runoff is contaminating groundwater and coastal waters.[74]

History

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Hawaii |

|---|

| Topics |

Hawaiʻi is one of two U.S. states, along with Texas, that were internationally recognized sovereign nations before becoming U.S. states. The Kingdom of Hawaiʻi was sovereign from 1810 until 1893, when resident American and European capitalists and landholders overthrew the monarchy. Hawaiʻi was an independent republic from 1894 until August 12, 1898, when it officially became a U.S. territory. Hawaiʻi was admitted as a U.S. state on August 21, 1959.[75]

First human settlement – Ancient Hawaiʻi (1000–1778)

Based on archaeological evidence, the earliest habitation of the Hawaiian Islands appears to date between 1000 and 1200 CE. The first wave was probably by Polynesian settlers from the Marquesas Islands,[13][dubious – discuss] and a second wave of migration from Raiatea and Bora Bora took place in the 11th century. The date of the human discovery and habitation of the Hawaiian Islands is the subject of academic debate.[76] Some archaeologists and historians think it was a later wave of immigrants from Tahiti around 1000 CE who introduced a new line of high chiefs, the kapu system, the practice of human sacrifice, and the building of heiau.[77] This later immigration is detailed in Hawaiian mythology (moʻolelo) about Paʻao. Other authors say there is no archaeological or linguistic evidence of a later influx of Tahitian settlers and that Paʻao must be regarded as a myth.[77]

The islands' history is marked by a slow, steady growth in population and the size of the chiefdoms, which grew to encompass whole islands. Local chiefs, called aliʻi, ruled their settlements, and launched wars to extend their influence and defend their communities from predatory rivals. Ancient Hawaiʻi was a caste-based society, much like that of Hindus in India.[78] Population growth was facilitated by ecological and agricultural practices that combined upland agriculture (manuka), ocean fishing (makai), fishponds and gardening systems. These systems were upheld by spiritual and religious beliefs, like the lokahi, that linked cultural continuity with the health of the natural world.[53] According to Hawaiian scholar Mililani Trask, the lokahi symbolizes the "greatest of the traditions, values, and practices of our people ... There are three points in the triangle—the Creator, Akua; the peoples of the earth, Kanaka Maoli; and the land, the ʻaina. These three things all have a reciprocal relationship."[53][79]

European arrival

The 1778 arrival of British explorer Captain James Cook marked the first documented contact by a European explorer with Hawaiʻi; early British influence can be seen in the design of the flag of Hawaiʻi, which bears the Union Jack in the top-left corner. Cook named the archipelago "the Sandwich Islands" in honor of his sponsor John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, publishing the islands' location and rendering the native name as Owyhee. The form "Owyhee" or "Owhyhee" is preserved in the names of certain locations in the American part of the Pacific Northwest, among them Owyhee County and Owyhee Mountains in Idaho, named after three native Hawaiian members of a trapping party who went missing in the area.[80]

Spanish explorers may have arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in the 16th century, 200 years before Cook's first documented visit in 1778. Ruy López de Villalobos commanded a fleet of six ships that left Acapulco in 1542 bound for the Philippines, with a Spanish sailor named Juan Gaetano aboard as pilot. Gaetano's reports describe an encounter with either Hawaiʻi or the Marshall Islands.[81][82][better source needed] If López de Villalobos's crew spotted Hawaiʻi, Gaetano would thus be the first European to see the islands. Most scholars have dismissed these claims due to a lack of credibility.[83][84][85]

Nonetheless, Spanish archives contain a chart that depicts islands at the same latitude as Hawaiʻi, but with a longitude ten degrees east of the islands. In this manuscript, Maui is named La Desgraciada (The Unfortunate Island), and what appears to be Hawaiʻi Island is named La Mesa (The Table). Islands resembling Kahoʻolawe', Lānaʻi, and Molokaʻi are named Los Monjes (The Monks).[86] For two and a half centuries, Spanish galleons crossed the Pacific from Mexico along a route that passed south of Hawaiʻi on their way to Manila. The exact route was kept secret to protect the Spanish trade monopoly against competing powers. Hawaiʻi thus maintained independence, despite being on a sea route east–west between nations that were subjects of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, an empire that exercised jurisdiction over many subject civilizations and kingdoms on both sides of the Pacific.[87]

Despite such contested claims, Cook is generally considered the first European to land at Hawaiʻi, having visited the Hawaiian Islands twice. As he prepared for departure after his second visit in 1779, a quarrel ensued as he took temple idols and fencing as "firewood",[88] and a minor chief and his group stole a boat from his ship. Cook abducted the King of Hawaiʻi Island, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, and held him for ransom aboard his ship to gain return of Cook's boat, as this tactic had previously worked in Tahiti and other islands.[89] Instead, the supporters of Kalaniʻōpuʻu attacked, killing Cook and four sailors as Cook's party retreated along the beach to their ship. The ship departed without retrieving the stolen boat.

After Cook's visit and the publication of several books relating his voyages, the Hawaiian Islands attracted many European and American explorers, traders, and whalers, who found the islands to be a convenient harbor and source of supplies. These visitors introduced diseases to the once-isolated islands, causing the Hawaiian population to drop precipitously.[90] Native Hawaiians had no resistance to Eurasian diseases, such as influenza, smallpox and measles. By 1820, disease, famine and wars between the chiefs killed more than half of the Native Hawaiian population.[91] During the 1850s, measles killed a fifth of Hawaiʻi's people.[92]

Historical records indicate the earliest Chinese immigrants to Hawaiʻi originated from Guangdong Province; a few sailors arrived in 1778 with Cook's journey, and more in 1789 with an American trader who settled in Hawaiʻi in the late 18th century. It is said that Chinese workers introduced leprosy by 1830, and as with the other new infectious diseases, it proved damaging to the Hawaiians.[93]

Kingdom of Hawaiʻi

House of Kamehameha

During the 1780s, and 1790s, chiefs often fought for power. After a series of battles that ended in 1795, all inhabited islands were subjugated under a single ruler, who became known as King Kamehameha the Great. He established the House of Kamehameha, a dynasty that ruled the kingdom until 1872.[94]

After Kamehameha II inherited the throne in 1819, American Protestant missionaries to Hawaiʻi converted many Hawaiians to Christianity. Missionaries have argued that one function of missionary work was to "civilize" and "purify" perceived heathenism in the New World. This carried into Hawaiʻi.[95][96][97][98][99][100] According to historical archaeologist James L. Flexner, "missionaries provided the moral means to rationalize conquest and wholesale conversion to Christianity".[95] But rather than abandon traditional beliefs entirely, most native Hawaiians merged their Indigenous religion with Christianity.[95][97][96] Missionaries used their influence to end many traditional practices, including the kapu system, the prevailing legal system before European contact, and heiau, or "temples" to religious figures.[95][101][102] Kapu, which typically translates to "the sacred", refers to social regulations (like gender and class restrictions) that were based upon spiritual beliefs. Under the missionaries' guidance, laws against gambling, consuming alcohol, dancing the hula, breaking the Sabbath, and polygamy were enacted.[96] Without the kapu system, many temples and priestly statuses were jeopardized, idols were burned, and participation in Christianity increased.[96][98] When Kamehameha III inherited the throne at age 12, his advisors pressured him to merge Christianity with traditional Hawaiian ways. Under the guidance of his kuhina nui (his mother and coregent Elizabeth Kaʻahumanu) and British allies, Hawaiʻi turned into a Christian monarchy with the signing of the 1840 Constitution.[103][98] Hiram Bingham I, a prominent Protestant missionary, was a trusted adviser to the monarchy during this period. Other missionaries and their descendants became active in commercial and political affairs, leading to conflicts between the monarchy and its restive American subjects.[104] Missionaries from the Roman Catholic Church and from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were also active in the kingdom, initially converting a minority of the Native Hawaiian population, but later becoming the first and second largest religious denominations on the islands, respectively.[105][106][107][108] Missionaries from each major group administered to the leper colony at Kalaupapa on Molokaʻi, which was established in 1866 and operated well into the 20th century. The best known were Father Damien and Mother Marianne Cope, both of whom were canonized in the early 21st century as Roman Catholic saints.

The death of the bachelor King Kamehameha V—who did not name an heir—resulted in the popular election of Lunalilo over Kalākaua. Lunalilo died the next year, also without naming an heir. In 1874, the election was contested within the legislature between Kalākaua and Emma, Queen Consort of Kamehameha IV. After riots broke out, the U.S. and Britain landed troops on the islands to restore order. The Legislative Assembly chose King Kalākaua as monarch by a vote of 39 to 6 on February 12, 1874.[109]

1887 Constitution and overthrow preparations

In 1887, Kalākaua was forced to sign the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. Drafted by white businessmen and lawyers, the document stripped the king of much of his authority. It established a property qualification for voting that effectively disenfranchised most Hawaiians and immigrant laborers and favored the wealthier, white elite. Resident whites were allowed to vote but resident Asians were not. As the 1887 Constitution was signed under threat of violence, it is known as the Bayonet Constitution. King Kalākaua, reduced to a figurehead, reigned until his death in 1891. His sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him; she was the last monarch of Hawaiʻi.[110]

In 1893, Liliʻuokalani announced plans for a new constitution to proclaim herself an absolute monarch. On January 14, 1893, a group of mostly Euro-American business leaders and residents formed the Committee of Safety to stage a coup d'état against the kingdom and seek annexation by the United States. U.S. Government Minister John L. Stevens, responding to a request from the Committee of Safety, summoned a company of U.S. Marines. The queen's soldiers did not resist. According to historian William Russ, the monarchy was unable to protect itself.[111] In Hawaiian Autonomy, Liliʻuokalani states:

If we did not by force resist their final outrage, it was because we could not do so without striking at the military force of the United States. Whatever constraint the executive of this great country may be under to recognize the present government at Honolulu has been forced upon it by no act of ours, but by the unlawful acts of its own agents. Attempts to repudiate those acts are vain.[112][113]

In a message to Sanford B. Dole, Liliʻuokalani states:

Now to avoid any collision of armed forces and perhaps the loss of life, I do under this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representatives and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.[114][115]

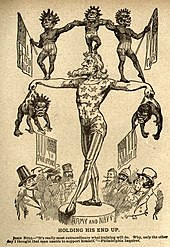

Overthrow of 1893 – Republic of Hawaiʻi (1894–1898)

The treason trials of 1892 brought together the main players in the 1893 overthrow. American Minister John L. Stevens voiced support for Native Hawaiian revolutionaries; William R. Castle, a Committee of Safety member, served as a defense counsel in the treason trials; Alfred Stedman Hartwell, the 1893 annexation commissioner, led the defense effort; and Sanford B. Dole ruled as a supreme court justice against acts of conspiracy and treason.[116]

On January 17, 1893, a small group of sugar and pineapple-growing businessmen, aided by the American minister to Hawaii and backed by heavily armed U.S. soldiers and marines, deposed Queen Liliʻuokalani and installed a provisional government composed of members of the Committee of Safety.[117] According to scholar Lydia Kualapai and Hawaii State Representative Roy Takumi, this committee was formed against the will of Indigenous Hawaiian voters, who constituted the majority of voters at the time, and consisted of "thirteen white men" according to scholar J Kehaulani Kauanui.[118][65][68] The United States Minister to the Kingdom of Hawaii (John L. Stevens) conspired with U.S. citizens to overthrow the monarchy.[119] After the overthrow, Sanford B. Dole, a citizen of Hawaii and cousin to James Dole, owner of Hawaiian Fruit Company, a company that benefited from the annexation of Hawaii, became president of the republic when the Provisional Government of Hawaiʻi ended on July 4, 1894.[120][121]

Controversy ensued in the following years as the queen tried to regain her throne. Scholar Lydia Kualapai writes that Liliʻuokalani had "yielded under protest not to the counterfeit Provisional Government of Hawaii but to the superior force of the United States of America" and wrote letters of protest to the president requesting a recognizance of allyship and a reinstatement of her sovereignty against the recent actions of the Provisional Government of Hawaii.[118] Following the January 1893 coup that deposed Liliʻuokalani, many royalists were preparing to overthrow the white-led Republic of Hawaiʻi oligarchy. Hundreds of rifles were covertly shipped to Hawaii and hidden in caves nearby. As armed troops came and went, a Republic of Hawaiʻi patrol discovered the rebel group. On January 6, 1895, gunfire began on both sides and later the rebels were surrounded and captured. Over the next 10 days several skirmishes occurred, until the last armed opposition surrendered or were captured. The Republic of Hawaiʻi took 123 troops into custody as prisoners of war. The mass arrest of nearly 300 more men and women, including Queen Liliʻuokalani, as political prisoners was intended to incapacitate the political resistance against the ruling oligarchy. In March 1895, a military tribunal convicted 170 prisoners of treason and sentenced six troops to be "hung by the neck" until dead, according to historian Ronald Williams Jr. The other prisoners were variously sentenced to from five to thirty-five years' imprisonment at hard labor, while those convicted of lesser charges received sentences from six months' to six years' imprisonment at hard labor.[122] The queen was sentenced to five years in prison, but spent eight months under house arrest until she was released on parole.[123] The total number of arrests related to the 1895 Kaua Kūloko was 406 people on a summary list of statistics, published by the government of the Republic of Hawaiʻi.[122]

The administration of President Grover Cleveland commissioned the Blount Report, which concluded that the removal of Liliʻuokalani had been illegal. Commissioner Blount found the U.S. and its minister guilty on all counts including the overthrow, the landing of the marines, and the recognition of the provisional government.[114] In a message to Congress, Cleveland wrote:

And finally, but for the lawless occupation of Honolulu under false pretexts by the United States forces, and but for Minister Stevens' recognition of the provisional government when the United States forces were its sole support and constituted its only military strength, the Queen and her Government would never have yielded to the provisional government, even for a time and for the sole purpose of submitting her case to the enlightened justice of the United States.[114][117] By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the Government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown. A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair. The provisional government has not assumed a republican or other constitutional form, but has remained a mere executive council or oligarchy, set up without the assent of the people. It has not sought to find a permanent basis of popular support and has given no evidence of an intention to do so.[117][114]

The U.S. government first demanded that Queen Liliʻuokalani be reinstated, but the Provisional Government refused. On December 23, 1893, the response from the Provisional Government of Hawaii, authored by President Sanford B. Dole, was received by Cleveland's representative Minister Albert S. Willis and emphasized that the Provisional Government of Hawaii "unhesitatingly" rejected the demand from the Cleveland Administration.[118]

Congress conducted an independent investigation, and on February 26, 1894, submitted the Morgan Report, which found all parties, including Minister Stevens—with the exception of the queen—"not guilty" and not responsible for the coup.[124] Partisans on both sides of the debate questioned the accuracy and impartiality of both the Blount and Morgan reports over the events of 1893.[111][125][126][127]

In 1993, Congress passed a joint Apology Resolution regarding the overthrow; it was signed by President Bill Clinton. The resolution apologized and said that the overthrow was illegal in the following phrase: "The Congress—on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi on January 17, 1893, acknowledges the historical significance of this event which resulted in the suppression of the inherent sovereignty of the Native Hawaiian people."[119] The Apology Resolution also "acknowledges that the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States and further acknowledges that the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi or through a plebiscite or referendum".[127][119]

Annexation – Territory of Hawaiʻi (1898–1959)

After William McKinley won the 1896 U.S. presidential election, advocates pressed to annex the Republic of Hawaiʻi. The previous president, Grover Cleveland, was a friend of Queen Liliʻuokalani. McKinley was open to persuasion by U.S. expansionists and by annexationists from Hawaiʻi. He met with three non-native annexationists: Lorrin A. Thurston, Francis March Hatch and William Ansel Kinney. After negotiations in June 1897, Secretary of State John Sherman agreed to a treaty of annexation with these representatives of the Republic of Hawaiʻi.[128] The U.S. Senate never ratified the treaty. Despite the opposition of most native Hawaiians,[129] the Newlands Resolution was used to annex the republic to the U.S.; it became the Territory of Hawaiʻi. The Newlands Resolution was passed by the House on June 15, 1898, by 209 votes in favor to 91 against, and by the Senate on July 6, 1898, by a vote of 42 to 21.[130][131][132]

A majority of Native Hawaiians opposed annexation, voiced chiefly by Liliʻuokalani, whom Hawaiian Haunani-Kay Trask described as beloved and respected by her people.[133] Liliʻuokalani wrote, "it had not entered into our hearts to believe that these friends and allies from the United States ... would ever go so far as to absolutely overthrow our form of government, seize our nation by the throat, and pass it over to an alien power" in her retelling of the overthrow of her government.[134] According to Trask, newspapers at the time argued Hawaiians would suffer "virtual enslavement under annexation", including further loss of lands and liberties, in particular to sugar plantation owners.[135] These plantations were protected by the U.S. Navy as economic interests, justifying a continued military presence in the islands.[135]

In 1900, Hawaiʻi was granted self-governance and retained ʻIolani Palace as the territorial capitol building. Despite several attempts to become a state, Hawaii remained a territory for 60 years. Plantation owners and capitalists, who maintained control through financial institutions such as the Big Five, found territorial status convenient because they remained able to import cheap, foreign labor. Such immigration and labor practices were prohibited in many states.[136]

Puerto Rican immigration to Hawaiʻi began in 1899, when Puerto Rico's sugar industry was devastated by a hurricane, causing a worldwide shortage of sugar and a huge demand for sugar from Hawaiʻi. Hawaiian sugarcane plantation owners began to recruit experienced, unemployed laborers in Puerto Rico. Two waves of Korean immigration to Hawaiʻi occurred in the 20th century. The first wave arrived between 1903 and 1924; the second wave began in 1965 after President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which removed racial and national barriers and resulted in significantly altering the demographic mix in the U.S.[137]

Oʻahu was the target of a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan on December 7, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor and other military and naval installations, carried out by aircraft and by midget submarines, brought the United States into World War II.

Political changes of 1954 – State of Hawaiʻi (1959–present)

In the 1950s, the plantation owners' power was broken by the descendants of immigrant laborers, who were born in Hawaiʻi and were U.S. citizens. They voted against the Hawaiʻi Republican Party, strongly supported by plantation owners. The new majority voted for the Democratic Party of Hawaiʻi, which dominated territorial and state politics for more than 40 years. Eager to gain full representation in Congress and the Electoral College, residents actively campaigned for statehood. In Washington, there was talk that Hawaiʻi would be a Republican Party stronghold. As a result, the admission of Hawaii was matched with the admission of Alaska, which was seen as a Democratic Party stronghold. These predictions proved inaccurate; as of 2017, Hawaiʻi generally votes Democratic, while Alaska typically votes Republican.[138][139][140][141]

During the Cold War, Hawai'i became an important site for U.S. cultural diplomacy, military training, research, and as a staging ground for the U.S. war in Vietnam.[142]: 105

In March 1959, Congress passed the Hawaiʻi Admissions Act, which U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed into law.[143] The act excluded Palmyra Atoll from statehood; it had been part of the Kingdom and Territory of Hawaiʻi. On June 27, 1959, a referendum asked residents of Hawaiʻi to vote on the statehood bill; 94.3% voted in favor of statehood and 5.7% opposed it.[144] The referendum asked voters to choose between accepting the Act and remaining a U.S. territory. The United Nations' Special Committee on Decolonization later removed Hawaiʻi from its list of non-self-governing territories.

After attaining statehood, Hawaiʻi quickly modernized through construction and a rapidly growing tourism economy. Later, state programs promoted Hawaiian culture.[which?] The Hawaiʻi State Constitutional Convention of 1978 created institutions such as the Office of Hawaiian Affairs to promote indigenous language and culture.[145]

Legacy of annexation on Hawaiian land

In 1897, over 21,000 Natives, representing the overwhelming majority of adult Hawaiians, signed anti-annexation petitions in one of the first examples of protest against the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani's government.[146] Nearly 100 years later, in 1993, 17,000 Hawaiians marched to demand access and control over Hawaiian trust lands and as part of the modern Hawaiian sovereignty movement.[147] Hawaiian trust land ownership and use is still widely contested as a consequence of annexation. According to scholar Winona LaDuke, as of 2015, 95% of Hawaiʻi's land was owned or controlled by just 82 landholders, including over 50% by federal and state governments, as well as the established sugar and pineapple companies.[147] The Thirty Meter Telescope is planned to be built on Hawaiian trust land, but has faced resistance as the project interferes with Kanaka indigeneity.[clarify][148]

Demographics

Population

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 84,165 | — | |

| 1860 | 69,800 | −17.1% | |

| 1890 | 89,990 | — | |

| 1900 | 154,001 | 71.1% | |

| 1910 | 191,909 | 24.6% | |

| 1920 | 255,912 | 33.4% | |

| 1930 | 368,336 | 43.9% | |

| 1940 | 423,330 | 14.9% | |

| 1950 | 499,794 | 18.1% | |

| 1960 | 632,772 | 26.6% | |

| 1970 | 768,561 | 21.5% | |

| 1980 | 964,691 | 25.5% | |

| 1990 | 1,108,229 | 14.9% | |

| 2000 | 1,211,537 | 9.3% | |

| 2010 | 1,360,301 | 12.3% | |

| 2020 | 1,455,271 | 7.0% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 1,435,138 | [149] | −1.4% |

| 1778 (est.) = 300000, 1819 (est.) = 145000, 1835–1836 = 107954, 1872 = 56897, 1884 = 80578, 1896 = 109020 | |||

After Europeans and mainland Americans first arrived during the Kingdom of Hawaii period, the overall population of Hawaii—which until that time composed solely of Indigenous Hawaiians—fell dramatically. Many people of the Indigenous Hawaiian population died to foreign diseases, declining from 300,000 in the 1770s, to 60,000 in the 1850s, to 24,000 in 1920. Other estimates for the pre-contact population range from 150,000 to 1.5 million.[14] The population of Hawaii began to finally increase after an influx of primarily Asian settlers that arrived as migrant laborers at the end of the 19th century.[152] In 1923, 42% of the population was of Japanese descent, 9% was of Chinese descent, and 16% was native descent.[153]

The unmixed indigenous Hawaiian population has still not restored itself to its 300,000 pre-contact level. As of 2010[update], only 156,000 persons declared themselves to be of Native Hawaiian-only ancestry, just over half the pre-contact level Native Hawaiian population, although an additional 371,000 persons declared themselves to possess Native Hawaiian ancestry in combination with one or more other races (including other Polynesian groups, but mostly Asian or Caucasian).

As of 2018[update], the United States Census Bureau estimates the population of Hawaii at 1,420,491, a decrease of 7,047 from the previous year and an increase of 60,190 (4.42%) since 2010. This includes a natural increase of 48,111 (96,028 births minus 47,917 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 16,956 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 30,068; migration within the country produced a net loss of 13,112 people.[154][needs update]

The center of population of Hawaii is located on the island of O'ahu. Large numbers of Native Hawaiians have moved to Las Vegas, which has been called the "ninth island" of Hawaii.[155][156]

Hawaii has a de facto population of over 1.4 million, due in part to a large number of military personnel and tourist residents. O'ahu is the most populous island; it has the highest population density with a resident population of just under one million in 597 square miles (1,546 km2), approximately 1,650 people per square mile.[g][157] Hawaii's 1.4 million residents, spread across 6,000 square miles (15,500 km2) of land, result in an average population density of 188.6 persons per square mile.[158] The state has a lower population density than Ohio and Illinois.[159]

The average projected lifespan of people born in Hawaii in 2000 is 79.8 years; 77.1 years if male, 82.5 if female—longer than the average lifespan of any other U.S. state.[160] As of 2011[update] the U.S. military reported it had 42,371 personnel on the islands.[161]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 5,967 homeless people in Hawaii.[162][163]

In 2018, The top countries of origin for immigrants in Hawaii were the Philippines, China, Japan, Korea and the Marshall Islands.[164]

Ancestry

According to the 2020 United States Census, Hawaii had a population of 1,455,271. The state's population identified as 37.2% Asian; 25.3% Multiracial; 22.9% White; 10.8% Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders; 9.5% Hispanic and Latinos of any race; 1.6% Black or African American; 1.8% from some other race; and 0.3% Native American and Alaskan Native.[165]

| Racial composition | 1970[166] | 1990[166] | 2000[167] | 2010[168] | 2020[165] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 38.8% | 33.4% | 24.3% | 24.7% | 22.9% |

| Asian | 57.7% | 61.8% | 41.6% | 38.6% | 37.2% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

9.4% | 10.0% | 10.8% | ||

| Black | 1.0% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 1.6% | 1.6% |

| Native American and Alaskan Native | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Other race | 2.4% | 1.9% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

| Two or more races | – | – | 21.4% | 23.6% | 25.3% |

Hawaii has the highest percentage of Asian Americans and multiracial Americans and the lowest percentage of White Americans of any state. It is the only state where people who identify as Asian Americans are the largest ethnic group. In 2012, 14.5% of the resident population under age 1 was non-Hispanic white.[169] Hawaii's Asian population consists mainly of 198,000 (14.6%) Filipino Americans, 185,000 (13.6%) Japanese Americans, roughly 55,000 (4.0%) Chinese Americans, and 24,000 (1.8%) Korean Americans.[170]

Over 120,000 (8.8%) Hispanic and Latino Americans live in Hawaii. Mexican Americans number over 35,000 (2.6%); Puerto Ricans exceed 44,000 (3.2%). Multiracial Americans constitute almost 25% of Hawaii's population, exceeding 320,000 people. Hawaii is the only state to have a tri-racial group as its largest multiracial group, one that includes white, Asian and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (22% of all mutiracial population).[171] The non-Hispanic White population numbers around 310,000—just over 20% of the population. The multi-racial population outnumbers the non-Hispanic white population by about 10,000 people.[170] In 1970, the Census Bureau reported Hawaii's population was 38.8% white and 57.7% Asian and Pacific Islander.[172]

There are more than 80,000 Indigenous Hawaiians—5.9% of the population.[170] Including those with partial ancestry, Samoan Americans constitute 2.8% of Hawaii's population, and Tongan Americans constitute 0.6%.[173]

The five largest European ancestries in Hawaii are German (7.4%), Irish (5.2%), English (4.6%), Portuguese (4.3%) and Italian (2.7%). About 82.2% of the state's residents were born in the United States. Roughly 75% of foreign-born residents originate from Asia. Hawaii is a majority-minority state. It was expected to be one of three states that would not have a non-Hispanic white plurality in 2014; the other two are California and New Mexico.[174]

| Ancestry | Percentage | Main article: |

|---|---|---|

| Filipino | 13.6% | See Filipinos in Hawaii |

| Japanese | 12.6% | See Japanese in Hawaii |

| Polynesian | 9.0% | See Native Hawaiians |

| Germans | 7.4% | See German American |

| Irish | 5.2% | See Irish American |

| English | 4.6% | See English American |

| Portuguese | 4.3% | See Portuguese in Hawaii |

| Chinese | 4.1% | See Chinese in Hawaii |

| Korean | 3.1% | See Korean American |

| Mexican | 2.9% | See Mexican American |

| Puerto Rican | 2.8% | See Puerto Ricans in Hawaii |

| Italian | 2.7% | See Italian American |

| African | 2.4% | See African American |

| French | 1.7% | See French American |

| Samoan | 1.3% | See Samoans in Hawaii |

| Scottish | 1.2% | See Scottish American |

The third group of foreigners to arrive in Hawaii were from China. Chinese workers on Western trading ships settled in Hawaii starting in 1789. In 1820, the first American missionaries arrived to preach Christianity and teach the Hawaiians Western ways.[177] As of 2015[update], a large proportion of Hawaii's population have Asian ancestry—especially Filipino, Japanese and Chinese. Many are descendants of immigrants brought to work on the sugarcane plantations in the mid-to-late 19th century. The first 153 Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii on June 19, 1868. They were not approved by the then-current Japanese government because the contract was between a broker and the Tokugawa shogunate—by then replaced by the Meiji Restoration. The first Japanese current-government-approved immigrants arrived on February 9, 1885, after Kalākaua's petition to Emperor Meiji when Kalākaua visited Japan in 1881.[178][179]

Almost 13,000 Portuguese migrants had arrived by 1899; they also worked on the sugarcane plantations.[180] By 1901, more than 5,000 Puerto Ricans were living in Hawaii.[181]

Languages

English and Hawaiian are listed as Hawaii's official languages in the state's 1978 constitution, in Article XV, Section 4.[182] However, the use of Hawaiian is limited because the constitution specifies that "Hawaiian shall be required for public acts and transactions only as provided by law". Hawaiʻi Creole English, locally referred to as "Pidgin", is the native language of many native residents and is a second language for many others.[183]

As of the 2000 Census, 73.4% of Hawaii residents age 5 and older exclusively speak English at home.[184] According to the 2008 American Community Survey, 74.6% of Hawaii's residents older than 5 speak only English at home.[175] In their homes, 21.0% of state residents speak an additional Asian language, 2.6% speak Spanish, 1.6% speak other Indo-European languages and 0.2% speak another language.[175]

After English, other languages popularly spoken in the state are Tagalog, Ilocano, and Japanese.[185] 5.4% of residents speak Tagalog, which includes non-native speakers of Filipino, a Tagalog-based national and co-official language of the Philippines; 5.0% speak Japanese and 4.0% speak Ilocano; 1.2% speak Chinese, 1.7% speak Hawaiian; 1.7% speak Spanish; 1.6% speak Korean; and 1.0% speak Samoan.[184]

Hawaiian

The Hawaiian language has about 2,000 native speakers, about 0.15% of the total population.[186] According to the United States Census, there were more than 24,000 total speakers of the language in Hawaii in 2006–2008.[187] Hawaiian is a Polynesian member of the Austronesian language family.[186] It is closely related to other Polynesian languages, such as Marquesan, Tahitian, Māori, Rapa Nui (the language of Easter Island), and less closely to Samoan and Tongan.[188]

According to Schütz, the Marquesans colonized the archipelago in roughly 300 CE[189] and were later followed by waves of seafarers from the Society Islands, Samoa and Tonga.[190] These Polynesians remained in the islands; they eventually became the Hawaiian people and their languages evolved into the Hawaiian language.[191] Kimura and Wilson say: "[l]inguists agree that Hawaiian is closely related to Eastern Polynesian, with a particularly strong link in the Southern Marquesas, and a secondary link in Tahiti, which may be explained by voyaging between the Hawaiian and Society Islands".[192]

Before the arrival of Captain James Cook, the Hawaiian language had no written form. That form was developed mainly by American Protestant missionaries between 1820 and 1826 who assigned to the Hawaiian phonemes letters from the Latin alphabet. Interest in Hawaiian increased significantly in the late 20th century. With the help of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, specially designated immersion schools in which all subjects would be taught in Hawaiian were established. The University of Hawaiʻi developed a Hawaiian-language graduate studies program. Municipal codes were altered to favor Hawaiian place and street names for new civic developments.[193]

Hawaiian distinguishes between long and short vowel sounds. In modern practice, vowel length is indicated with a macron (kahakō). Hawaiian-language newspapers (nūpepa) published from 1834 to 1948 and traditional native speakers of Hawaiian generally omit the marks in their own writing. The ʻokina and kahakō are intended to capture the proper pronunciation of Hawaiian words.[194] The Hawaiian language uses the glottal stop (ʻOkina) as a consonant. It is written as a symbol similar to the apostrophe or left-hanging (opening) single quotation mark.[195]

The keyboard layout used for Hawaiian is QWERTY.[196]

Hawaiian Pidgin

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

Some residents of Hawaii speak Hawaiʻi Creole English (HCE), endonymically called pidgin or pidgin English. The lexicon of HCE derives mainly from English but also uses words that have derived from Hawaiian, Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Ilocano and Tagalog. During the 19th century, the increase in immigration—mainly from China, Japan, Portugal—especially from the Azores and Madeira, and Spain—catalyzed the development of a hybrid variant of English known to its speakers as pidgin. By the early 20th century, pidgin speakers had children who acquired it as their first language. HCE speakers use some Hawaiian words without those words being considered archaic.[clarification needed] Most place names are retained from Hawaiian, as are some names for plants and animals. For example, tuna fish is often called by its Hawaiian name, ahi.[197]

HCE speakers have modified the meanings of some English words. For example, "aunty" and "uncle" may either refer to any adult who is a friend or be used to show respect to an elder. Syntax and grammar follow distinctive rules different from those of General American English. For example, instead of "it is hot today, isn't it?", an HCE speaker would say simply "stay hot, eh?"[h] The term da kine is used as a filler; a substitute for virtually any word or phrase. During the surfing boom in Hawaii, HCE was influenced by surfer slang. Some HCE expressions, such as brah and da kine, have found their ways elsewhere through surfing communities.[198]

Hawaiʻi Sign Language

Hawaiʻi Sign Language, a sign language for the Deaf based on the Hawaiian language, has been in use in the islands since the early 1800s. It is dwindling in numbers due to American Sign Language supplanting HSL through schooling and various other domains.[199]

Religion

Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[200]

Religion in Hawaii (2014)[201]

Hawaii is among the most religiously diverse states in the U.S., with one in ten residents practicing a non-Christian faith.[202] Roughly one-quarter to half the population identify as unaffiliated and nonreligious, making Hawaii one of the most secular states as well.

Christianity remains the majority religion, represented mainly by various Protestant groups and Roman Catholicism. The second-largest religion is Buddhism, which comprises a larger proportion of the population than in any other state; it is concentrated in the Japanese community. Native Hawaiians continue to engage in traditional religious and spiritual practices today, often adhering to Christian and traditional beliefs at the same time.[53][97][95][79][96]

The Cathedral Church of Saint Andrew in Honolulu was formally the seat of the Hawaiian Reformed Catholic Church, a province of the Anglican Communion that had been the state church of the Kingdom of Hawaii; it subsequently merged into the Episcopal Church in the 1890s following the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, becoming the seat of the Episcopal Diocese of Hawaii. The Cathedral Basilica of Our Lady of Peace and the Co-Cathedral of Saint Theresa of the Child Jesus serve as seats of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu. The Eastern Orthodox community is centered around the Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Pacific.

The largest religious denominations by membership were the Roman Catholic Church with 249,619 adherents in 2010;[203] the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 68,128 adherents in 2009;[204] the United Church of Christ with 115 congregations and 20,000 members; and the Southern Baptist Convention with 108 congregations and 18,000 members.[205] Nondenominational churches collectively have 128 congregations and 32,000 members.

According to data provided by religious establishments, religion in Hawaii in 2000 was distributed as follows:[206][207]

- Christianity: 351,000 (29%)

- Buddhism: 110,000 (9%)

- Judaism: 10,000 (1%)[208]

- Other: 100,000 (10%)

- Unaffiliated: 650,000 (51%)

However, a Pew poll found that the religious composition was as follows:

| Affiliation | % of Hawaiʻi's population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian | 63 | |

| Protestant | 38 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 25 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 11 | |

| Black church | 2 | |

| Roman Catholic | 20 | |

| Mormon | 3 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 1 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 0.5 | |

| Other Christian | 1 | |

| Unaffiliated | 26 | |

| Nothing in particular | 20 | |

| Agnostic | 5 | |

| Atheist | 2 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 10 | |

| Jewish | 0.5 | |

| Muslim | 0.5 | |

| Buddhist | 8 | |

| Hindu | 0.5 | |

| Other Non-Christian faiths | 0.5 | |

| Don't know | 1 | |

| Total | 100 | |

Birth data

Note: Births in this table do not add up, because Hispanic peoples are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[209] | 2014[210] | 2015[211] | 2016[212] | 2017[213] | 2018[214] | 2019[215] | 2020[216] | 2021[217] | 2022[218] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 12,203 (64.3%) | 11,535 (62.2%) | 11,443 (62.1%) | 4,616 (25.6%) | 4,653 (26.6%) | 4,366 (25.7%) | 4,330 (25.8%) | 3,940 (25.0%) | 3,851 (24.6%) | 3,854 (24.8%) |

| White: | 6,045 (31.8%) | 6,368 (34.3%) | 6,322 (34.3%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 4,940 (26.0%) | 4,881 (26.3%) | 4,803 (26.1%) | 3,649 (20.2%) | 3,407 (19.4%) | 3,288 (19.4%) | 3,223 (19.2%) | 3,060 (19.4%) | 3,018 (19.3%) | 2,896 (18.6%) |

| Pacific Islander | ... | ... | ... | 1,747 (9.7%) | 1,684 (9.6%) | 1,706 (10.1%) | 1,695 (10.1%) | 1,577 (10.0%) | 1,371 (8.8%) | 1,486 (9.6%) |

| Black | 671 (3.5%) | 617 (3.3%) | 620 (3.3%) | 463 (2.6%) | 406 (2.3%) | 424 (2.5%) | 429 (2.6%) | 383 (2.4%) | 342 (2.2%) | 326 (2.1%) |

| American Indian | 68 (0.3%) | 30 (0.2%) | 35 (0.2%) | 28 (0.1%) | 39 (0.2%) | 33 (0.2%) | 27 (0.2%) | 25 (0.1%) | 23 (0.1%) | 30 (0.2%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 3,003 (15.8%) | 2,764 (14.9%) | 2,775 (15.1%) | 2,766 (15.3%) | 2,672 (15.3%) | 2,580 (15.2%) | 2,589 (15.4%) | 2,623 (16.6%) | 2,661 (17.0%) | 2,701 (17.4%) |

| Total Hawaiʻi | 18,987 (100%) | 18,550 (100%) | 18,420 (100%) | 18,059 (100%) | 17,517 (100%) | 16,972 (100%) | 16,797 (100%) | 15,785 (100%) | 15,620 (100%) | 15,535 (100%) |

- 1) Until 2016, data for births of Asian origin, included also births of the Pacific Islander group.

- 2) Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

LGBTQ

Hawaii has had a long history of LGBTQIA+ identities. Māhū ("in the middle") were a precolonial third gender with traditional spiritual and social roles, widely respected as healers. Homosexual relationships known as aikāne were widespread and normal in ancient Hawaiian society.[219][220][221] Among men, aikāne relationships often began as teens and continued throughout their adult lives, even if they also maintained heterosexual partners.[222] While aikāne usually refers to male homosexuality, some stories also refer to women, implying that women may have been involved in aikāne relationships as well.[223] Journals written by Captain Cook's crew record that many aliʻi (hereditary nobles) also engaged in aikāne relationships, and Kamehameha the Great, the founder and first ruler of the Kingdom of Hawaii, was also known to participate. Cook's second lieutenant and co-astronomer James King observed that "all the chiefs had them", and recounts that Cook was actually asked by one chief to leave King behind, considering the role a great honor.

Hawaiian scholar Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa notes that aikāne served a practical purpose of building mutual trust and cohesion; "If you didn't sleep with a man, how could you trust him when you went into battle? How would you know if he was going to be the warrior that would protect you at all costs, if he wasn't your lover?"[224]

As Western colonial influences intensified in the late 19th and early 20th century, the word aikāne was expurgated of its original sexual meaning, and in print simply meant "friend". Nonetheless, in Hawaiian language publications its metaphorical meaning can still mean either "friend" or "lover" without stigmatization.[225]

A 2012 Gallup poll found that Hawaii had the largest proportion of LGBTQIA+ adults in the U.S., at 5.1%, an estimated 53,966 individuals. The number of same-sex couple households in 2010 was 3,239, representing a 35.5% increase from a decade earlier.[226][227] In 2013, Hawaii became the fifteenth U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage; this reportedly boosted tourism by $217 million.[228]

Economy

The history of Hawaii's economy can be traced through a succession of dominant industries: sandalwood,[229] whaling,[230] sugarcane, pineapple, the military, tourism and education. By the 1840s, sugar plantations had gained a strong foothold in the Hawaiian economy, due to a high demand of sugar in the United States and rapid transport via steamships.[69] Sugarcane plantations were tightly controlled by American missionary families and businessmen known as "the Big Five", who monopolized control of the sugar industry's profits.[69][70] By the time Hawaiian annexation was being considered in 1898, sugarcane producers turned to cultivating tropical fruits like pineapple, which became the principal export for Hawaiʻi's plantation economy.[70][69] Since statehood in 1959, tourism has been the largest industry, contributing 24.3% of the gross state product (GSP) in 1997, despite efforts to diversify. The state's gross output for 2003 was US$47 billion; per capita income for Hawaii residents in 2014 was US$54,516.[231] Hawaiian exports include food and clothing. These industries play a small role in the Hawaiian economy, due to the shipping distance to viable markets, such as the West Coast of the United States. The state's food exports include coffee, macadamia nuts, pineapple, livestock, sugarcane and honey.[232]

By weight, honey bees may be the state's most valuable export.[233] According to the Hawaii Agricultural Statistics Service, agricultural sales were US$370.9 million from diversified agriculture, US$100.6 million from pineapple, and US$64.3 million from sugarcane. Hawaii's relatively consistent climate has attracted the seed industry, which is able to test three generations of crops per year on the islands, compared with one or two on the mainland.[234] Seeds yielded US$264 million in 2012, supporting 1,400 workers.[235]

As of December 2015[update], the state's unemployment rate was 3.2%.[236] In 2009, the United States military spent US$12.2 billion in Hawaii, accounting for 18% of spending in the state for that year. 75,000 United States Department of Defense personnel live in Hawaii.[237] According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Hawaii at that time had the fourth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 7.2%.[238]

Taxation

Tax is collected by the Hawaii Department of Taxation.[239] Most government revenue comes from personal income taxes and a general excise tax (GET) levied primarily on businesses; there is no statewide tax on sales,[240] personal property, or stock transfers,[241] while the effective property tax rate is among the lowest in the country.[242] The high rate of tourism means that millions of visitors generate public revenue through GET and the hotel room tax.[243] However, Hawaii residents generally pay among the most state taxes per person in the U.S.[243]

The Tax Foundation of Hawaii considers the state's tax burden too high, claiming that it contributes to higher prices and the perception of an unfriendly business climate.[243] The nonprofit Tax Foundation ranks Hawaii third in income tax burden and second in its overall tax burden, though notes that a significant portion of taxes are borne by tourists.[244] Former State Senator Sam Slom attributed Hawaii's comparatively high tax rate to the fact that the state government is responsible for education, health care, and social services that are usually handled at a county or municipal level in most other states.[243]

Cost of living

The cost of living in Hawaii, specifically Honolulu, is high compared to that of most major U.S. cities, although it is 6.7% lower than in New York City and 3.6% lower than in San Francisco.[245] These numbers may not take into account some costs, such as increased travel costs for flights, additional shipping fees, and the loss of promotional participation opportunities for customers outside the contiguous U.S. While some online stores offer free shipping on orders to Hawaii, many merchants exclude Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and certain other U.S. territories.[246][247]

Hawaiian Electric Industries, a privately owned company, provides 95% of the state's population with electricity, mostly from fossil-fuel power stations. Average electricity prices in October 2014 (36.41 cents per kilowatt-hour) were nearly three times the national average (12.58 cents per kilowatt-hour) and 80% higher than the second-highest state, Connecticut.[248]

The median home value in Hawaii in the 2000 U.S. Census was US$272,700, while the national median home value was US$119,600. Hawaii home values were the highest of all states, including California with a median home value of US$211,500.[249] Research from the National Association of Realtors places the 2010 median sale price of a single family home in Honolulu, Hawaii, at US$607,600 and the U.S. median sales price at US$173,200. The sale price of single family homes in Hawaii was the highest of any U.S. city in 2010, just above that of the Silicon Valley area of California (US$602,000).[250]

Hawaii's very high cost of living is the result of several interwoven factors of the global economy in addition to domestic U.S. government trade policy. Like other regions with desirable weather year-round, such as California, Arizona and Florida, Hawaii's residents can be considered to be subject to a "sunshine tax". This situation is further exacerbated by the natural factors of geography and world distribution that lead to higher prices for goods due to increased shipping costs, a problem which many island states and territories suffer from as well.

The higher costs to ship goods across an ocean may be further increased by the requirements of the Jones Act, which generally requires that goods be transported between places within the U.S., including between the mainland U.S. west coast and Hawaii, using only U.S.-owned, built, and crewed ships. Jones Act-compliant vessels are often more expensive to build and operate than foreign equivalents, which can drive up shipping costs. While the Jones Act does not affect transportation of goods to Hawaii directly from Asia, this type of trade is nonetheless not common; this is a result of other primarily economic reasons including additional costs associated with stopping over in Hawaii (e.g. pilot and port fees), the market size of Hawaii, and the economics of using ever-larger ships that cannot be handled in Hawaii for transoceanic voyages. Therefore, Hawaii relies on receiving most inbound goods on Jones Act-qualified vessels originating from the U.S. west coast, which may contribute to the increased cost of some consumer goods and therefore the overall cost of living.[251][252] Critics of the Jones Act contend that Hawaii consumers ultimately bear the expense of transporting goods imposed by the Jones Act.[253]

Culture

The aboriginal culture of Hawaii is Polynesian. Hawaii represents the northernmost extension of the vast Polynesian Triangle of the south and central Pacific Ocean. While traditional Hawaiian culture remains as vestiges in modern Hawaiian society, there are re-enactments of the ceremonies and traditions throughout the islands. Some of these cultural influences, including the popularity (in greatly modified form) of lūʻau and hula, are strong enough to affect the wider United States.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Hawaii is a fusion of many foods brought by immigrants to the Hawaiian Islands, including the earliest Polynesians and Native Hawaiian cuisine, and American, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, Polynesian, Puerto Rican, and Portuguese origins. Plant and animal food sources are imported from around the world for agricultural use in Hawaii. Poi, a starch made by pounding taro, is one of the traditional foods of the islands. Many local restaurants serve the ubiquitous plate lunch, which features two scoops of rice, a simplified version of American macaroni salad and a variety of toppings including hamburger patties, a fried egg, and gravy of a loco moco, Japanese style tonkatsu or the traditional lūʻau favorites, including kālua pork and laulau. Spam musubi is an example of the fusion of ethnic cuisine that developed on the islands among the mix of immigrant groups and military personnel. In the 1990s, a group of chefs developed Hawaii regional cuisine as a contemporary fusion cuisine.

Customs and etiquette

Some key customs and etiquette in Hawaii are as follows: when visiting a home, it is considered good manners to bring a small gift for one's host (for example, a dessert). Thus, parties are usually in the form of potlucks. Most locals take their shoes off before entering a home. It is customary for Hawaiian families, regardless of ethnicity, to hold a luau to celebrate a child's first birthday. It is also customary at Hawaiian weddings, especially at Filipino weddings, for the bride and groom to do a money dance (also called the pandanggo). Print media and local residents recommend that one refer to non-Hawaiians as "locals of Hawaii" or "people of Hawaii".

Hawaiian mythology

Hawaiian mythology includes the legends, historical tales, and sayings of the ancient Hawaiian people. It is considered a variant of a more general Polynesian mythology that developed a unique character for several centuries before c. 1800. It is associated with the Hawaiian religion, which was officially suppressed in the 19th century but was kept alive by some practitioners to the modern day.[254] Prominent figures and terms include Aumakua, the spirit of an ancestor or family god and Kāne, the highest of the four major Hawaiian deities.[citation needed]

Polynesian mythology

Polynesian mythology is the oral traditions of the people of Polynesia, a grouping of Central and South Pacific Ocean island archipelagos in the Polynesian triangle together with the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers. Polynesians speak languages that descend from a language reconstructed as Proto-Polynesian that was probably spoken in the area around Tonga and Samoa in around 1000 BC.[255]

Prior to the 15th century, Polynesian people migrated east to the Cook Islands, and from there to other island groups such as Tahiti and the Marquesas. Their descendants later discovered the islands Tahiti, Rapa Nui, and later the Hawaiian Islands and New Zealand.[256]

The Polynesian languages are part of the Austronesian language family. Many are close enough in terms of vocabulary and grammar to be mutually intelligible. There are also substantial cultural similarities between the various groups, especially in terms of social organization, childrearing, horticulture, building and textile technologies. Their mythologies in particular demonstrate local reworkings of commonly shared tales. The Polynesian cultures each have distinct but related oral traditions; legends or myths are traditionally considered to recount ancient history (the time of "pō") and the adventures of gods ("atua") and deified ancestors.[citation needed]

List of state parks

There are many Hawaiian state parks.

- The Island of Hawaiʻi has state parks, recreation areas, and historical parks.

- Kauaʻi has the Ahukini State Recreation Pier, six state parks, and the Russian Fort Elizabeth State Historical Park.

- Maui has two state monuments, several state parks, and the Polipoli Spring State Recreation Area. Moloka'i has the Pala'au State Park.

- Oʻahu has several state parks, a number of state recreation areas, and a number of monuments, including the Ulu Pō Heiau State Monument.

Literature

The literature of Hawaii is diverse and includes authors Kiana Davenport, Lois-Ann Yamanaka, and Kaui Hart Hemmings. Hawaiian magazines include Hana Hou!, Hawaii Business and Honolulu, among others.

Music

The music of Hawaii includes traditional and popular styles, ranging from native Hawaiian folk music to modern rock and hip hop.

Styles such as slack-key guitar are well known worldwide, while Hawaiian-tinged music is a frequent part of Hollywood soundtracks. Hawaii also made a major contribution to country music with the introduction of the steel guitar.[257]

Traditional Hawaiian folk music is a major part of the state's musical heritage. The Hawaiian people have inhabited the islands for centuries and have retained much of their traditional musical knowledge. Their music is largely religious in nature, and includes chanting and dance music.