SARS-CoV-2: Difference between revisions

→Name: title of this article is more clear |

Updated link to COVID-19 |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{pp-semi|small=yes}} |

{{pp-semi|small=yes}} |

||

{{About|the virus|the disease| |

{{About|the virus|the disease|COVID-19|the outbreak|2019–20 Wuhan coronavirus outbreak}} |

||

{{short description|Species of virus causing the 2019–20 Wuhan outbreak}} |

{{short description|Species of virus causing the 2019–20 Wuhan outbreak}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} |

||

Revision as of 17:59, 11 February 2020

| 2019-nCoV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of a 2019-nCoV virion | |

| |

| Cross-sectional illustration of 2019-nCoV virions showing internal components | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Pisuviricota |

| Class: | Pisoniviricetes |

| Order: | Nidovirales |

| Family: | Coronaviridae |

| Genus: | Betacoronavirus |

| Subgenus: | Sarbecovirus |

| Virus: | 2019-nCoV

|

| Wuhan, China, the epicenter of the only recorded outbreak | |

The 2019 novel coronavirus (provisionally named 2019-nCoV),[1][2] informally known as the Wuhan coronavirus,[3][4] is a contagious virus that causes 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease (COVID-19), a respiratory infection. It is the cause of the ongoing 2019–20 Wuhan coronavirus outbreak,[5] a global health emergency. Genomic sequencing has shown that it is a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA coronavirus.[6][7][8]

Many early cases were linked to a large seafood and animal market in the Chinese city of Wuhan, and the virus is thought to have a zoonotic origin.[9][10] Comparisons of the genetic sequences of this virus and other virus samples have shown similarities to SARS-CoV (79.5%) and bat coronaviruses (96%).[11] This makes an ultimate origin in bats likely,[12][13] although an intermediate host, such as a pangolin,[14] cannot be ruled out.[15]

Virology

Infection

Human-to-human transmission of the virus has been confirmed.[16] Coronaviruses are primarily spread through close contact, in particular through respiratory droplets from coughs and sneezes within a range of about 6 feet (1.8 m).[17][18] Viral RNA has also been found in stool samples from infected patients.[19] It is possible that the virus can be infectious even during the incubation period, but this has not been proven,[20] and the World Health Organization (WHO) states that "transmission from asymptomatic cases is likely not a major driver of transmission" at this time.[21]

Reservoir

Animals sold for food were originally suspected to be the reservoir or intermediary hosts of 2019-nCoV because many of the first individuals found to be infected by the virus were workers at the Huanan Seafood Market.[22] A market selling live animals for food was also blamed in the SARS outbreak in 2003; such markets are considered to be incubators for novel pathogens.[23] The outbreak has prompted a temporary ban on the trade and consumption of wild animals in China.[24] However, some researchers have suggested that the Huanan Seafood Market may not be the original source of viral transmission to humans.[25][26]

With a sufficient number of sequenced genomes, it is possible to reconstruct a phylogenetic tree of the mutation history of a family of viruses. Research into the origin of the 2003 SARS outbreak has resulted in the discovery of many SARS-like bat coronaviruses, most originating in the Rhinolophus genus of horseshoe bats. 2019-nCoV falls into this category of SARS-related coronaviruses. Two genome sequences from Rhinolophus sinicus published in 2015 and 2017 show a resemblance of 80% to 2019-nCoV.[27][12] A third virus genome from Rhinolophus affinis, "RaTG13" collected in Yunnan province, has a 96% resemblance to 2019-nCoV.[11][28] For comparison, this amount of variation among viruses is similar to the amount of mutation observed over ten years in the H3N2 human influenza virus strain.[29]

Phylogenetics and taxonomy

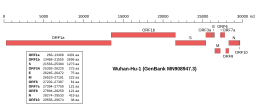

Genomic organisation of 2019-nCoV | |

| NCBI genome ID | MN908947 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

2019-nCoV belongs to the broad family of viruses known as coronaviruses; "nCoV" is the standard term used to refer to novel coronaviruses until the choice of a more specific designation. It is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA) virus. Other coronaviruses are capable of causing illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). It is the seventh known coronavirus to infect people, after 229E, NL63, OC43, HKU1, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV.[30]

Like SARS-CoV, 2019-nCoV is a member of the subgenus Sarbecovirus (Beta-CoV lineage B).[31][22][32] Its RNA sequence is approximately 30,000 bases in length.[8]

By 12 January, five genomes of 2019-nCoV had been isolated from Wuhan and reported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CCDC) and other institutions;[8][33][34] the number of genomes increased to 81 by 11 February.[35] A phylogenic analysis of the samples shows they are "highly related with at most seven mutations relative to a common ancestor", implying that the first human infection occurred in November or December 2019.[35]

Structural biology

![Ribbon diagram of M(pro) protease], a prospective target for antiviral drugs against 2019-nCoV](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7f/Coronavirus_2019-nCoV.3.png/220px-Coronavirus_2019-nCoV.3.png)

Publication of the 2019-nCoV genome led to several protein modeling experiments on the receptor binding protein (RBD) of the spike (S) protein of the virus. Results suggest that the S protein retains sufficient affinity to the Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to use it as a mechanism of cell entry.[36] On 22 January, a group in China working with the full virus and a group in the U.S. working with reverse genetics independently and experimentally demonstrated ACE2 as the receptor for 2019-nCoV.[37][38][39]

To look for potential protease inhibitors, the viral 3C-like protease M(pro) from the ORF1a polyprotein has also been modeled for drug docking experiments. Innophore has produced two computational models based on SARS protease,[40] and the Chinese Academy of Sciences has produced an unpublished experimental structure of a recombinant 2019-nCoV protease.[41] In addition, researchers at the University of Michigan have modeled the structures of all mature peptides in the 2019-nCov genome using I-TASSER.[42]

Epidemiology

The first known human infection occurred in early December 2019.[43][25] An outbreak of 2019-nCoV was first detected in Wuhan, China, in mid-December 2019, likely originating from a single infected animal.[25] The virus subsequently spread to all provinces of China and to more than two dozen other countries in Asia, Europe, North America, and Oceania.[44] Human-to-human spread of the virus has been confirmed in all of these regions.[16][45][46][47] On 30 January 2020, 2019-nCoV was designated a global health emergency by the WHO.[48][49][50]

As of 11 February 2020[update] (04:00 UTC), there were 43,108 confirmed cases of infection, of which 42,644 were within mainland China.[44] One mathematical model estimated the number of people infected in Wuhan alone at 75,815 as of 25 January 2020.[51] Nearly all cases outside China have occurred in people who either traveled from Wuhan, or were in direct contact with someone who traveled from the area.[52][53] While the proportion of infections that result in confirmed infection or progress to diagnosable 2019-nCoV acute respiratory disease remains unclear,[54][55] the total number of deaths attributed to the virus was 1,018 as of 11 February 2020 (04:00 UTC); over 95% of all deaths have occurred in Hubei province,[44] where Wuhan is located.

The basic reproduction number (, pronounced R-nought or R-zero)[56] of the virus has been estimated to be between 1.4 and 3.9.[57][58][59][60][61] This means that, when unchecked, the virus typically results in 1.4 to 3.9 new cases per established infection. It has been established that the virus is able to transmit along a chain of at least four people.[62]

Vaccine research

In January 2020, multiple organizations and institutions began work on creating vaccines for 2019-nCoV based on the published genome.[63]

In China, the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention is developing a vaccine against the novel coronavirus.[64][65] The University of Hong Kong has also announced that a vaccine is under development there but has yet to proceed to animal testing.[66] Shanghai East Hospital is also developing a vaccine in partnership with the biotechnology company Stemirna Therapeutics.[66]

Elsewhere, three vaccine projects are being supported by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), including projects by the biotechnology companies Moderna and Inovio Pharmaceuticals and another by the University of Queensland.[67] The United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) is cooperating with Moderna to create an RNA vaccine matching a spike of the coronavirus surface, and intends to start human trials by May 2020.[63] Inovio Pharmaceuticals is developing a DNA-based vaccination and collaborating with a Chinese firm in order to speed its acceptance by regulatory authorities in China, hoping to perform human trials of the vaccine in the summer of 2020.[68] In Australia, the University of Queensland is investigating the potential of a molecular clamp vaccine that would genetically modify viral proteins to make them mimic the coronavirus and stimulate an immune reaction.[67]

In an independent project, the Public Health Agency of Canada has granted permission to the International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac) at the University of Saskatchewan to begin work on a vaccine.[69] VIDO-InterVac aims to start production and animal testing in March 2020, and human testing in 2021.[69]

The Imperial College Faculty of Medicine in London is now at the stage of testing a vaccine on animals.[70]

Name

During the ongoing outbreak, the virus has often been referred to in common parlance as "the coronavirus", "the new coronavirus" and "the Wuhan coronavirus",[71][72] while the WHO recommends the temporary designation "2019-nCoV". Amid concerns that the absence of an official name may lead to the use of prejudicial informal names, per 2015 WHO guidelines,[72][73] the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) has announced that it will introduce a suitable official name for the virus in the second week of February 2020.[71]

On 11 February 2020, the WHO named the disease caused by the virus COVID-19, short for "coronavirus disease 2019", stating "We now have a name for the 2019-nCoV disease: COVID-19."[74][75]

References

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Surveillance case definitions for human infection with novel coronavirus (nCoV): interim guidance v1, January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330376. WHO/2019-nCoV/Surveillance/v2020.1.

- ^ "Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China". United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 10 January 2020. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Huang, Pien (22 January 2020). "How Does Wuhan Coronavirus Compare With MERS, SARS And The Common Cold?". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Fox, Dan (2020). "What you need to know about the Wuhan coronavirus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00209-y. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019 nCoV): Frequently Asked Questions | IDPH". www.dph.illinois.gov. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "中国疾病预防控制中心" (in Chinese). People's Republic of China: Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "New-type coronavirus causes pneumonia in Wuhan: expert". People's Republic of China. Xinhua. Archived from the original on 9 January 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "CoV2020". platform.gisaid.org. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Perlman, Stanley (24 January 2020). "Another Decade, Another Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2001126. PMID 31978944.

- ^ Wu, Joseph T.; Leung, Kathy; Leung, Gabriel M. (31 January 2020). "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". The Lancet. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMID 32014114. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b Zhou, Peng; Yang, Xing-Lou; Wang, Xian-Guang; Hu, Ben; Zhang, Lei; Zhang, Wei; Si, Hao-Rui (3 February 2020). "A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin". Nature: 1–4. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. PMID 32015507. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020 – via www.nature.com/.

- ^ a b Benvenuto, Domenico; Giovannetti, Marta; Ciccozzi, Alessandra; Spoto, Silvia; Angeletti, Silvia; Ciccozzi, Massimo (2020). "The 2019-new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution". Journal of Medical Virology. doi:10.1002/jmv.25688.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen; Cyranoski, David (23 January 2020). "Why snakes probably aren't spreading the new China virus". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00180-8. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: From bats to pangolins, how do viruses reach us?". DW. 7 February 2020.

- ^ "nCoV's relationship to bat coronaviruses & recombination signals (no snakes) - no evidence the 2019-nCoV lineage is recombinant". Virological. 22 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ a b Chan, Jasper Fuk-Woo; Yuan, Shuofeng; Kok, Kin-Hang; To, Kelvin Kai-Wang; Chu, Hin; Yang, Jin; Xing, Fanfan; Liu, Jieling; Yip, Cyril Chik-Yan; Poon, Rosana Wing-Shan; Tsoi, Hoi-Wah; Lo, Simon Kam-Fai; Chan, Kwok-Hung; Poon, Vincent Kwok-Man; Chan, Wan-Mui; Ip, Jonathan Daniel; Cai, Jian-Piao; Cheng, Vincent Chi-Chung; Chen, Honglin; Hui, Christopher Kim-Ming; Yuen, Kwok-Yung (24 January 2020). "A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster". The Lancet. 0. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. PMID 31986261 – via www.thelancet.com.

- ^ "How does coronavirus spread?". NBC News. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Transmission of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 January 2020. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Holshue, Michelle L.; DeBolt, Chas; Lindquist, Scott; Lofy, Kathy H.; Wiesman, John; Bruce, Hollianne; Spitters, Christopher; Ericson, Keith; Wilkerson, Sara; Tural, Ahmet; Diaz, George (31 January 2020). "First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States". New England Journal of Medicine: NEJMoa2001191. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 32004427.

- ^ Kupferschmidt, Kai (3 February 2020). "Study claiming new coronavirus can be transmitted by people without symptoms was flawed". Science. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 12 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330777.

- ^ a b Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, Ippolito G, Mchugh TD, Memish ZA, Drosten C, Zumla A, Petersen E. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health – The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Jan 14;91:264–266. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. PMID 31953166.

- ^ Myers, Steven Lee (25 January 2020). "China's Omnivorous Markets Are in the Eye of a Lethal Outbreak Once Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020.

- ^ McNeil, Sam; Wang, Penny Yi; Kurtenbach, Elaine (27 January 2020), China temporarily bans wildlife trade in wake of outbreak, archived from the original on 28 January 2020, retrieved 28 January 2020

- ^ a b c Cohen, Jon (January 2020). "Wuhan seafood market may not be source of novel virus spreading globally". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb0611. ISSN 0036-8075.

- ^ Eschner, Kat (28 January 2020). "We're still not sure where the Wuhan coronavirus really came from". Popular Science. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Sample CoVZC45 and CoVZXC21, see Nextstrain for an interactive visualisation Archived 20 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Bat coronavirus isolate RaTG13, complete genome" (Document). NCBI. 29 January 2020.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ "Real-time tracking of influenza A/H3N2 evolution using data from GISAID". nextstrain.org.

- ^ Zhu, Na; Zhang, Dingyu; Wang, Wenling; Li, Xinwang; Yang, Bo; Song, Jingdong; Zhao, Xiang; Huang, Baoying; Shi, Weifeng; Lu, Roujian; Niu, Peihua; Zhan, Faxian; Ma, Xuejun; Wang, Dayan; Xu, Wenbo; Wu, Guizhen; Gao, George F.; Tan, Wenjie (24 January 2020). "A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019". New England Journal of Medicine. 0. United States. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 31978945.

- ^ "Phylogeny of SARS-like betacoronaviruses". nextstrain. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- ^ Antonio C. P. Wong, Xin Li, Susanna K. P. Lau, Patrick C. Y. Woo. Global Epidemiology of Bat Coronaviruses. Viruses. 2019 Feb;11(2):174. doi:10.3390/v11020174.

- ^ "Initial genome release of novel coronavirus". Virological. 11 January 2020. Archived from the original on 12 January 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ^ "Wuhan seafood market pneumonia virus isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, complete genome". National Center for Biotechnology Information. United States: National Institutes of Health. 17 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus (nCoV)". nextstrain.org. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Xu, Xintian; Chen, Ping; Wang, Jingfang; Feng, Jiannan; Zhou, Hui; Li, Xuan; Zhong, Wu; Hao, Pei (21 January 2020). "Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission". Science China Life Sciences. doi:10.1007/s11427-020-1637-5. PMID 32009228.

- ^ Letko, Michael; Munster, Vincent (22 January 2020). "Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B β-coronaviruses, including 2019-nCoV". bioRxiv 2020.01.22.915660.

{{cite bioRxiv}}: Check|biorxiv=value (help) - ^ El Sahly, Hana M. "Genomic Characterization of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus". The New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Gralinski, Lisa E.; Menachery, Vineet D. (2020). "Return of the Coronavirus: 2019-nCoV". Viruses. 12 (2): 135. doi:10.3390/v12020135. PMID 31991541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Gruber, Christian; Steinkellner, Georg (23 January 2020). "Wuhan coronavirus 2019-nCoV - what we can find out on a structural bioinformatics level". Innophore Enzyme Discovery. Innophore GmbH. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.11752749.

- ^ "上海药物所和上海科技大学联合发现一批可能对新型肺炎有治疗作用的老药和中药". Chinese Academy of Sciences. 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Chengxin Zhang, Eric W. Bell, Xiaoqiang Huang, Yang Zhang (2020): 2019-nCoV". zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "WHO | Novel Coronavirus – China". WHO. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ a b c "Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS". gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rothe, Camilla (2020). "Transmission of 2019-nCoV Infection from an Asymptomatic Contact in Germany". NEJM: Correspondence to the Editor Page. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2001468. PMID 32003551.

- ^ "The Coronavirus Is Now Infecting More People Outside China". Wired. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Khalik, Salma (4 February 2020). "Coronavirus: Singapore reports first cases of local transmission; 4 out of 6 new cases did not travel to China". Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus declared global health emergency". BBC News Online. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Wee, Sui-Lee; McNeil Jr., Donald G.; Hernández, Javier C. (30 January 2020). "W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organization (WHO). 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ Wu, Joseph T; Leung, Kathy; Leung, Gabriel M (4 February 2020). "Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study". The Lancet: S0140673620302609. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. PMID 32014114.

- ^ World Health Organization (2020). Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): situation report, 5 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330769.

- ^ "Germany confirms seventh coronavirus case". Reuters. February 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "Limited data on coronavirus may be skewing assumptions about severity". STAT. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Sparrow, Annie. "How China's Coronavirus Is Spreading—and How to Stop It". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Milligan, Gregg N.; Barrett, Alan D. T. (2015). Vaccinology : an essential guide. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-118-63652-7. OCLC 881386962.

- ^ "The Deceptively Simple Number Sparking Coronavirus Fears". The Atlantic. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Li, Qun; Guan, Xuhua; Wu, Peng; Wang, Xiaoye (29 January 2020). "Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia". New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. PMID 31995857.

- ^ Riou, Julien; Althaus, Christian L. (2020). "Pattern of early human-to-human transmission of Wuhan 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), December 2019 to January 2020". Eurosurveillance. 25 (4). doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.4.2000058. PMID 32019669.

- ^ Liu, Tao; Hu, Jianxiong; Kang, Min; Lin, Lifeng (25 January 2020). "Transmission dynamics of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". bioRxiv: 2020.01.25.919787. doi:10.1101/2020.01.25.919787.

- ^ Read, Jonathan M.; Bridgen, Jessica RE; Cummings, Derek AT; Ho, Antonia; Jewell, Chris P. (28 January 2020). "Novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV: early estimation of epidemiological parameters and epidemic predictions". MedRxiv: 2020.01.23.20018549. doi:10.1101/2020.01.23.20018549.

- ^ Saey, Tina Hesman (24 January 2020). "How the new coronavirus stacks up against SARS and MERS". Science News. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b Steenhuysen, Julie; Kelland, Kate (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "China CDC developing novel coronavirus vaccine". Xinhua. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Chinese scientists race to develop vaccine as coronavirus death toll jumps". South China Morning Post. 26 January 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ a b Cheung, Elizabeth (28 January 2020). "Hong Kong researchers have developed coronavirus vaccine, expert reveals". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ a b Devlin, Hannah (24 January 2020). "Lessons from SARS outbreak help in race for coronavirus vaccine". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Mazumdar, Tulip (30 January 2020). "Coronavirus: Scientists race to develop a vaccine". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Saskatchewan lab joins global effort to develop coronavirus vaccine". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus: 'Significant breakthrough' in race for vaccine made by UK scientists". Sky News. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ a b Taylor-Coleman, Jasmine (5 February 2020). "How the new coronavirus will finally get a proper name". BBC. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ a b Stobbe, Mike (8 February 2020). "Wuhan coronavirus? 2019 nCoV? Naming a new disease". Fortune. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ World Health Organization Best Practices for the Naming of New Human Infectious Diseases. World Health Organization. May 2015.

- ^ "WHO Director-General's remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020". www.who.int. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus disease named Covid-19". BBC. 11 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

Further reading

- World Health Organization (2020). Laboratory testing of human suspected cases of novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection: interim guidance, 10 January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330374. WHO/2019-nCoV/laboratory/2020.1.

- World Health Organization (2020). WHO R&D Blueprint: informal consultation on prioritization of candidate therapeutic agents for use in novel coronavirus 2019 infection, Geneva, Switzerland, 24 January 2020 (Report). World Health Organization. hdl:10665/330680. WHO/HEO/R&D Blueprint (nCoV)/2020.1.

- Bender, Maddie (3 February 2020). "'It's a Moral Imperative:' Archivists Made a Directory of 5,000 Coronavirus Studies to Bypass Paywalls". vice.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

External links

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC) explanation of 2019-nCoV

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) list of public 2019-nCoV sequences

- World Health Organization (WHO) site on 2019-nCoV

- "2019-nCoV". FDA. 7 February 2020.

- "Coronavirus". BMJ.

- "Novel Coronavirus Information Center". Elsevier.

- "2019-nCoV Resource Centre". Lancet.

- "2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". NEJM.

- "Coronavirus Research". Wiley.

- "The Novel Coronavirus: A Bird's Eye View". Int J Occup Environ Med: 1921–65–71. 5 February 2020.

- 2019-nCoV Data Portal in the Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource database