Beer

Beer is the world's most widely consumed[1] alcoholic beverage; it is the third most popular drink overall, after water and tea.[2] It is thought by some to be the oldest fermented beverage[3][4][5][6] It is produced by the brewing and fermentation of sugars, mainly derived from malted cereal grains, most commonly malted barley and malted wheat. Sugars derived from maize (corn) and rice are widely used adjuncts because of their lower cost. Most beer is flavoured with hops, which add bitterness and act as a natural preservative, though other flavourings such as herbs or fruit may occasionally be included. Some of humanity's earliest known writings refer to the production and distribution of beer: the Code of Hammurabi included laws regulating beer and beer parlours,[7] and "The Hymn to Ninkasi", a prayer to the Mesopotamian goddess of beer, served as both a prayer and as a method of remembering the recipe for beer in a culture with few literate people.[8][9] Today, the brewing industry is a global business, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and many thousands of smaller producers ranging from brewpubs to regional breweries.

The strength of beer is usually around 4% to 6% alcohol by volume (abv) though may range from less than 1% abv, to over 20% abv in rare cases.

Beer forms part of the culture of beer-drinking nations and is associated with social traditions such as beer festivals, as well as a rich pub culture involving activities like pub crawling and pub games such as bar billiards.

Definition

Beer can be broadly defined as a fermented beverage made from a source of starch without distillation. Beverages such as sake, huangjiu, and cheongiu that are made from rice, chicha, made from maize, and cauim and masato that are made from manioc are properly considered forms of beer [10]. Distillation in this sense includes various processes to increase the alcohol content by a large fraction, especially by evaporation and collecting the alcohol-enriched vapors, or freezing and discarding the alcohol-depleted ice.

History

Beer is one of the world's oldest prepared beverages, possibly dating back to the early Neolithic or 9500 BC, when cereal was first farmed,[11] and is recorded in the written history of ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.[12] Archaeologists speculate that beer was instrumental in the formation of civilisations.[13]

The earliest known chemical evidence of beer dates to circa 3500–3100 BC from the site of Godin Tepe in the Zagros Mountains of western Iran[14][15]. Some of the earliest Sumerian writings found in the region contain references to a type of beer; one such example, a prayer to the goddess Ninkasi, known as "The Hymn to Ninkasi", served as both a prayer as well as a method of remembering the recipe for beer in a culture with few literate people.[8][9] The Ebla tablets, discovered in 1974 in Ebla, Syria and date back to 2500 BC, reveal that the city produced a range of beers, including one that appears to be named "Ebla" after the city.[16] A beer made from rice, which, unlike sake, did not use the amylolytic process, and was probably prepared for fermentation by mastication or malting,[17] was made in China around 7000 BC.[18]

As almost any substance containing carbohydrates, mainly sugars or starch, can naturally undergo fermentation, it is likely that beer-like beverages were independently invented among various cultures throughout the world. Bread and beer increased prosperity to a level that allowed time for development of other technology and contributed to the building of civilizations.[19][20][21][22]

Beer was spread through Europe by Germanic and Celtic tribes as far back as 3000 BC,[23] and it was mainly brewed on a domestic scale.[24] The product that the early Europeans drank might not be recognised as beer by most people today. Alongside the basic starch source, the early European beers might contain fruits, honey, numerous types of plants, spices and other substances such as narcotic herbs.[25] What they did not contain was hops, as that was a later addition, first mentioned in Europe around 822 by a Carolingian Abbot[26] and again in 1067 by Abbess Hildegard of Bingen.[27]

In 1516, William IV, Duke of Bavaria, adopted the Reinheitsgebot (purity law), perhaps the oldest food-quality regulation still in use in the 21st century, according to which the only allowed ingredients of beer are water, hops and barley-malt.[28] Beer produced before the Industrial Revolution continued to be made and sold on a domestic scale, although by the 7th century AD, beer was also being produced and sold by European monasteries. During the Industrial Revolution, the production of beer moved from artisanal manufacture to industrial manufacture, and domestic manufacture ceased to be significant by the end of the 19th century.[29] The development of hydrometers and thermometers changed brewing by allowing the brewer more control of the process and greater knowledge of the results.

Today, the brewing industry is a global business, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and many thousands of smaller producers ranging from brewpubs to regional breweries.[30] As of 2006, more than 133 billion liters (35 billion gallons), the equivalent of a cube 510 metres on a side, of beer are sold per year, producing total global revenues of $294.5 billion (£147.7 billion).[31]

In 2010, China's beer consumption hit 450 million hectoliters (45 billion liters) or nearly twice that of the United States but only 5 percent sold were Premium draught beers, compared with 50 percent in France and Germany.[32]

Brewing

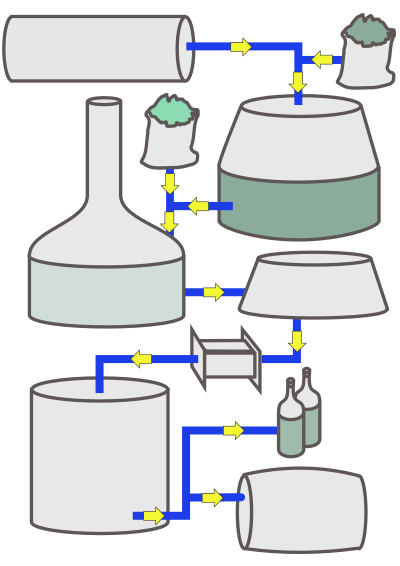

The process of making beer is known as brewing. A dedicated building for the making of beer is called a brewery, though beer can be made in the home and has been for much of its history. A company that makes beer is called either a brewery or a brewing company. Beer made on a domestic scale for non-commercial reasons is classified as homebrewing regardless of where it is made, though most homebrewed beer is made in the home. Brewing beer is subject to legislation and taxation in developed countries, which from the late 19th century largely restricted brewing to a commercial operation only. However, the UK government relaxed legislation in 1963, followed by Australia in 1972 and the USA in 1979, allowing homebrewing to become a popular hobby.[33]

The purpose of brewing is to convert the starch source into a sugary liquid called wort and to convert the wort into the alcoholic beverage known as beer in a fermentation process effected by yeast.

The first step, where the wort is prepared by mixing the starch source (normally malted barley) with hot water, is known as "mashing". Hot water (known as "liquor" in brewing terms) is mixed with crushed malt or malts (known as "grist") in a mash tun.[34] The mashing process takes around 1 to 2 hours,[35] during which the starches are converted to sugars, and then the sweet wort is drained off the grains. The grains are now washed in a process known as "sparging". This washing allows the brewer to gather as much of the fermentable liquid from the grains as possible. The process of filtering the spent grain from the wort and sparge water is called wort separation. The traditional process for wort separation is lautering, in which the grain bed itself serves as the filter medium. Some modern breweries prefer the use of filter frames which allow a more finely ground grist.[36] Most modern breweries use a continuous sparge, collecting the original wort and the sparge water together. However, it is possible to collect a second or even third wash with the not quite spent grains as separate batches. Each run would produce a weaker wort and thus a weaker beer. This process is known as second (and third) runnings. Brewing with several runnings is called parti gyle brewing.[37]

The sweet wort collected from sparging is put into a kettle, or "copper", (so called because these vessels were traditionally made from copper)[38] and boiled, usually for about one hour. During boiling, water in the wort evaporates, but the sugars and other components of the wort remain; this allows more efficient use of the starch sources in the beer. Boiling also destroys any remaining enzymes left over from the mashing stage. Hops are added during boiling as a source of bitterness, flavour and aroma. Hops may be added at more than one point during the boil. The longer the hops are boiled, the more bitterness they contribute, but the less hop flavour and aroma remains in the beer.[39]

After boiling, the hopped wort is now cooled, ready for the yeast. In some breweries, the hopped wort may pass through a hopback, which is a small vat filled with hops, to add aromatic hop flavouring and to act as a filter; but usually the hopped wort is simply cooled for the fermenter, where the yeast is added. During fermentation, the wort becomes beer in a process which requires a week to months depending on the type of yeast and strength of the beer. In addition to producing alcohol, fine particulate matter suspended in the wort settles during fermentation. Once fermentation is complete, the yeast also settles, leaving the beer clear.[40]

Fermentation is sometimes carried out in two stages, primary and secondary. Once most of the alcohol has been produced during primary fermentation, the beer is transferred to a new vessel and allowed a period of secondary fermentation. Secondary fermentation is used when the beer requires long storage before packaging or greater clarity.[41] When the beer has fermented, it is packaged either into casks for cask ale or kegs, aluminium cans, or bottles for other sorts of beer.[42]

Ingredients

The basic ingredients of beer are water; a starch source, such as malted barley, able to be fermented (converted into alcohol); a brewer's yeast to produce the fermentation; and a flavouring such as hops.[43] A mixture of starch sources may be used, with a secondary starch source, such as maize (corn), rice or sugar, often being termed an adjunct, especially when used as a lower-cost substitute for malted barley.[44] Less widely used starch sources include millet, sorghum and cassava root in Africa, potato in Brazil, and agave in Mexico, among others.[45] The amount of each starch source in a beer recipe is collectively called the grain bill.

- Water

Beer is composed mostly of water. Regions have water with different mineral components; as a result, different regions were originally better suited to making certain types of beer, thus giving them a regional character.[46] For example, Dublin has hard water well suited to making stout, such as Guinness; while Pilzen has soft water well suited to making pale lager, such as Pilsner Urquell.[46] The waters of Burton in England contain gypsum, which benefits making pale ale to such a degree that brewers of pale ales will add gypsum to the local water in a process known as Burtonisation.[47]

- Starch source

The starch source in a beer provides the fermentable material and is a key determinant of the strength and flavour of the beer. The most common starch source used in beer is malted grain. Grain is malted by soaking it in water, allowing it to begin germination, and then drying the partially germinated grain in a kiln. Malting grain produces enzymes that convert starches in the grain into fermentable sugars.[48] Different roasting times and temperatures are used to produce different colours of malt from the same grain. Darker malts will produce darker beers.[49]

Nearly all beer includes barley malt as the majority of the starch. This is because its fibrous hull remains attached to the grain during threshing. After malting, barley is milled, which finally removes the hull, breaking it into large pieces. These pieces remain with the grain during the mash, and act as a filter bed during lautering, when sweet wort is separated from insoluble grain material. Other malted and unmalted grains (including wheat, rice, oats, and rye, and less frequently, corn and sorghum) may be used. In recent years, a few brewers have produced gluten-free beer, made with sorghum with no barley malt, for those who cannot consume gluten-containing grains like wheat, barley, and rye.[50]

- Hops

Flavouring beer is the sole major commercial use of hops.[51] The flower of the hop vine is used as a flavouring and preservative agent in nearly all beer made today. The flowers themselves are often called "hops".

The first historical mention of the use of hops in beer was from 822 AD in monastery rules written by Adalhard the Elder, also known as Adalard of Corbie,[29][52] though the date normally given for widespread cultivation of hops for use in beer is the thirteenth century.[29][52] Before the thirteenth century, and until the sixteenth century, during which hops took over as the dominant flavouring, beer was flavoured with other plants; for instance, Glechoma hederacea. Combinations of various aromatic herbs, berries, and even ingredients like wormwood would be combined into a mixture known as gruit and used as hops are now used.[53] Some beers today, such as Fraoch' by the Scottish Heather Ales company[54] and Cervoise Lancelot by the French Brasserie-Lancelot company,[55] use plants other than hops for flavouring.

Hops contain several characteristics that brewers desire in beer. Hops contribute a bitterness that balances the sweetness of the malt; the bitterness of beers is measured on the International Bitterness Units scale. Hops contribute floral, citrus, and herbal aromas and flavours to beer. Hops have an antibiotic effect that favours the activity of brewer's yeast over less desirable microorganisms, and hops aids in "head retention",[56][57] the length of time that a foamy head created by carbonation will last. The acidity of hops is a preservative.[58][59]

- Yeast

Yeast is the microorganism that is responsible for fermentation in beer. Yeast metabolises the sugars extracted from grains, which produces alcohol and carbon dioxide, and thereby turns wort into beer. In addition to fermenting the beer, yeast influences the character and flavour.[60] The dominant types of yeast used to make beer are the top-fermenting Saccharomyces cerevisiae and bottom-fermenting Saccharomyces uvarum.[61] Brettanomyces ferments lambics,[62] and Torulaspora delbrueckii ferments Bavarian weissbier.[63] Before the role of yeast in fermentation was understood, fermentation involved wild or airborne yeasts. A few styles such as lambics rely on this method today, but most modern fermentation adds pure yeast cultures.[64]

- Clarifying agent

Some brewers add one or more clarifying agents to beer, which typically precipitate (collect as a solid) out of the beer along with protein solids and are found only in trace amounts in the finished product. This process makes the beer appear bright and clean, rather than the cloudy appearance of ethnic and older styles of beer such as wheat beers.[65]

Examples of clarifying agents include isinglass, obtained from swimbladders of fish; Irish moss, a seaweed; kappa carrageenan, from the seaweed Kappaphycus cottonii; Polyclar (artificial); and gelatin.[66] If a beer is marked "suitable for Vegans", it was clarified either with seaweed or with artificial agents.[67]

Production

The Benedictine Weihenstephan Brewery in Bavaria, Germany, can trace its roots to the year 768, as a document from that year refers to a hop garden in the area paying a tithe to the monastery. The brewery was licensed by the City of Freising in 1040, and therefore is the oldest working brewery in the world.[68]

Today, the brewing industry is a global business, consisting of several dominant multinational companies and many thousands of smaller producers ranging from brewpubs to regional breweries.[30] More than 133 billion liters (35 billion gallons) are sold per year—producing total global revenues of $294.5 billion (£147.7 billion) in 2006.[31]

A microbrewery, or craft brewery, is a modern brewery which produces a limited amount of beer.[69] The maximum amount of beer a brewery can produce and still be classed as a microbrewery varies by region and by authority, though is usually around 15,000 barrels (18,000 hectolitres/ 475,000 US gallons) a year.[70] A brewpub is a type of microbrewery that incorporates a pub or other eating establishment.

SABMiller became the largest brewing company in the world when it acquired Royal Grolsch, brewer of Dutch premium beer brand Grolsch.[71] InBev was the second-largest beer-producing company in the world,[68] and Anheuser-Busch held the third spot, but after the acquisition of Anheuser-Busch by InBev, the new Anheuser-Busch InBev company is the largest brewer in the world."[72]

Brewing at home is subject to regulation and prohibition in many countries. Restrictions on homebrewing were lifted in the UK in 1963,[73] Australia followed suit in 1972,[74] and the USA in 1978, though individual states were allowed to pass their own laws limiting production.[75]

Varieties

While there are many types of beer brewed, the basics of brewing beer are shared across national and cultural boundaries.[76] The traditional European brewing regions—Germany, Belgium, England and the Czech Republic—have local varieties of beer[77].

Michael Jackson, in his 1977 book The World Guide To Beer, categorised beers from around the world in local style groups suggested by local customs and names.[78] Fred Eckhardt furthered Jackson's work in The Essentials of Beer Style in 1989.

Top-fermented beers are most commonly produced with Saccharomyces cerevisiae which clumps and rises to the surface,[79] typically between 15 and 24 °C (60 and 75 °F). At these temperatures, yeast produces significant amounts of esters and other secondary flavour and aroma products, and the result is often a beer with slightly "fruity" compounds resembling apple, pear, pineapple, banana, plum, or prune, among others.[80]

Before the introduction of hops into England from the Netherlands in the 15th century, the name "ale" was exclusively applied to unhopped fermented beverages, the term beer being gradually introduced to describe a brew with an infusion of hops.[81] The word ale may come from the Old English ealu, in turn from the Proto-Indo-European base *alut-, which holds connotations of "sorcery, magic, possession, intoxication".[82]

Real ale is the term coined by the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) in 1973[83] for "beer brewed from traditional ingredients, matured by secondary fermentation in the container from which it is dispensed, and served without the use of extraneous carbon dioxide". It is applied to bottle conditioned and cask conditioned beers.

- Pale Ale

Pale ale is a beer which uses a top-fermenting yeast[84] and predominantly pale malt. It is one of the world's major beer styles.

- Stout

Stout and porter are dark beers made using roasted malts or roast barley, and typically brewed with slow fermenting yeast. There are a number of variations including Baltic porter, dry stout, and Imperial stout. The name Porter was first used in 1721 to describe a dark brown beer popular with the street and river porters of London.[85] This same beer later also became known as stout, though the word stout had been used as early as 1677.[86] The history and development of stout and porter are intertwined.[87]

- Mild

Mild ale has a predominantly malty palate. It is usually dark coloured with an abv of 3% to 3.6%, although there are lighter hued milds as well as stronger examples reaching 6% abv and higher.

- Wheat

Wheat beer is brewed with a large proportion of wheat although it often also contains a significant proportion of malted barley. Wheat beers are usually top-fermented (in Germany they have to be by law).[88] The flavour of wheat beers varies considerably, depending upon the specific style.

- Lager

Lager is the English name for cool fermenting beers of Central European origin. Pale lagers are the most commonly consumed beers in the world. The name "lager" comes from the German "lagern" for "to store", as brewers around Bavaria stored beer in cool cellars and caves during the warm summer months. These brewers noticed that the beers continued to ferment, and to also clear of sediment, when stored in cool conditions.[89]

Lager yeast is a cool bottom-fermenting yeast (Saccharomyces pastorianus) and typically undergoes primary fermentation at 7–12 °C (45–54 °F) (the fermentation phase), and then is given a long secondary fermentation at 0–4 °C (32–39 °F) (the lagering phase). During the secondary stage, the lager clears and mellows. The cooler conditions also inhibit the natural production of esters and other byproducts, resulting in a "cleaner"-tasting beer.[90]

Modern methods of producing lager were pioneered by Gabriel Sedlmayr the Younger, who perfected dark brown lagers at the Spaten Brewery in Bavaria, and Anton Dreher, who began brewing a lager (now known as Vienna lager), probably of amber-red colour, in Vienna in 1840–1841. With improved modern yeast strains, most lager breweries use only short periods of cold storage, typically 1–3 weeks.

- Lambic

Lambic, a beer of Belgium, is naturally fermented using wild yeasts, rather than cultivated. Many of these are not strains of brewer's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and may have significant differences in aroma and sourness. Yeast varieties such as Brettanomyces bruxellensis and Brettanomyces lambicus are common in lambics. In addition, other organisms such as Lactobacillus bacteria produce acids which contribute to the sourness.[91]

Measurement

Beer is measured and assessed by bitterness, by strength and by colour. The perceived bitterness is measured by the International Bitterness Units scale (IBU), defined in co-operation between the American Society of Brewing Chemists and the European Brewery Convention.[92] The international scale was a development of the European Bitterness Units scale, often abbreviated as EBU, and the bitterness values should be identical.[93]

Colour

Beer colour is determined by the malt.[94] The most common colour is a pale amber produced from using pale malts. Pale lager and pale ale are terms used for beers made from malt dried with coke. Coke was first used for roasting malt in 1642, but it was not until around 1703 that the term pale ale was used.[95][96]

In terms of sales volume, most of today's beer is based on the pale lager brewed in 1842 in the town of Pilsen in the present-day Czech Republic.[97] The modern pale lager is light in colour with a noticeable carbonation (fizzy bubbles) and a typical alcohol by volume content of around 5%. The Pilsner Urquell, Bitburger, and Heineken brands of beer are typical examples of pale lager, as are the American brands Budweiser, Coors, and Miller.

Dark beers are usually brewed from a pale malt or lager malt base with a small proportion of darker malt added to achieve the desired shade. Other colourants—such as caramel—are also widely used to darken beers. Very dark beers, such as stout, use dark or patent malts that have been roasted longer. Some have roasted unmalted barley.[98][99]

Strength

Beer ranges from less than 3% alcohol by volume (abv) to around 14% abv, though this strength can be increased to around 20% by re-pitching with champagne yeast,[100] and to 55% abv by the freeze-distilling process.[101] The alcohol content of beer varies by local practice or beer style.[102] The pale lagers that most consumers are familiar with fall in the range of 4–6%, with a typical abv of 5%.[103] The customary strength of British ales is quite low, with many session beers being around 4% abv.[104] Some beers, such as table beer are of such low alcohol content (1%–4%) that they are served instead of soft drinks in some schools.[105]

The alcohol in beer comes primarily from the metabolism of sugars that are produced during fermentation. The quantity of fermentable sugars in the wort and the variety of yeast used to ferment the wort are the primary factors that determine the amount of alcohol in the final beer. Additional fermentable sugars are sometimes added to increase alcohol content, and enzymes are often added to the wort for certain styles of beer (primarily "light" beers) to convert more complex carbohydrates (starches) to fermentable sugars. Alcohol is a by-product of yeast metabolism and is toxic to the yeast; typical brewing yeast cannot survive at alcohol concentrations above 12% by volume. Low temperatures and too little fermentation time decreases the effectiveness of yeasts and consequently decreases the alcohol content.

- Exceptionally strong beers

The strength of beers has climbed during the later years of the 20th century. Vetter 33, a 10.5% abv (33 degrees Plato, hence Vetter "33") doppelbock, was listed in the 1994 Guinness Book of World Records as the strongest beer at that time,[106][107] though Samichlaus, by the Swiss brewer Hürlimann, had also been listed by the Guinness Book of World Records as the strongest at 14% abv.[108][109][110] Since then, some brewers have used champagne yeasts to increase the alcohol content of their beers. Samuel Adams reached 20% abv with Millennium,[100] and then surpassed that amount to 25.6% abv with Utopias. The strongest beer brewed in Britain was Baz's Super Brew by Parish Brewery, a 23% abv beer.[111][112] In September 2011, the Scottish brewery BrewDog produced Ghost Deer, which, at 28%, they claim to be the world's strongest beer produced by fermentation alone.[113]

The product claimed to be the strongest beer made is The End of History, a 55% Belgian ale,[101] made by BrewDog in 2010. The same company had previously made Sink The Bismarck!, a 41% abv IPA,[114] and Tactical Nuclear Penguin, a 32% abv Imperial Stout. Each of these beers are made using the eisbock method of fractional freezing, in which a strong ale is partially frozen and the ice is repeatedly removed, until the desired strength is reached,[115][116] a process that may class the product as spirits rather than beer.[117] The German brewery Schorschbräu's Schorschbock, a 31% abv eisbock,[118][119][120] and Hair of the Dog's Dave, a 29% abv barley wine made in 1994, used the same fractional freezing method.[121] A 60% abv blend of beer with whiskey was jokingly claimed as the strongest beer by a Dutch brewery in July 2010.[122][123]

Serving

Draught

Draught beer from a pressurised keg is the most common method of dispensing in bars around the world. A metal keg is pressurised with carbon dioxide (CO2) gas which drives the beer to the dispensing tap or faucet. Some beers may be served with a nitrogen/carbon dioxide mixture. Nitrogen produces fine bubbles, resulting in a dense head and a creamy mouthfeel. Some types of beer can also be found in smaller, disposable kegs called beer balls.

In the 1980s, Guinness introduced the beer widget, a nitrogen-pressurised ball inside a can which creates a dense, tight head, similar to beer served from a nitrogen system.[124] The words draft and draught can be used as marketing terms to describe canned or bottled beers containing a beer widget, or which are cold-filtered rather than pasteurised.

Cask-conditioned ales (or cask ales) are unfiltered and unpasteurised beers. These beers are termed "real ale" by the CAMRA organisation. Typically, when a cask arrives in a pub, it is placed horizontally on a frame called a "stillage" which is designed to hold it steady and at the right angle, and then allowed to cool to cellar temperature (typically between 11–13 °C (52–55 °F)*),[125] before being tapped and vented—a tap is driven through a (usually rubber) bung at the bottom of one end, and a hard spile or other implement is used to open a hole in the side of the cask, which is now uppermost. The act of stillaging and then venting a beer in this manner typically disturbs all the sediment, so it must be left for a suitable period to "drop" (clear) again, as well as to fully condition—this period can take anywhere from several hours to several days. At this point the beer is ready to sell, either being pulled through a beer line with a hand pump, or simply being "gravity-fed" directly into the glass.

Draught beer's environmental impact can be 68% lower than bottled beer due to packaging differences.[126][127] A life cycle study of one beer brand, including grain production, brewing, bottling, distribution and waste management, shows that the CO2 emissions from a 6-pack of micro-brew beer is about 3 kilograms (6.6 pounds).[128] The loss of natural habitat potential from the 6-pack of micro-brew beer is estimated to be 2.5 square meters (26 square feet).[129] Downstream emissions from distribution, retail, storage and disposal of waste can be over 45% of a bottled micro-brew beer's CO2 emissions.[128] Where legal, the use of a refillable jug, reusable bottle or other reusable containers to transport draught beer from a store or a bar, rather than buying pre-bottled beer, can reduce the environmental impact of beer consumption.[130]

Packaging

Most beers are cleared of yeast by filtering when packaged in bottles and cans.[131] However, bottle conditioned beers retain some yeast—either by being unfiltered, or by being filtered and then reseeded with fresh yeast.[132] It is usually recommended that the beer be poured slowly, leaving any yeast sediment at the bottom of the bottle. However, some drinkers prefer to pour in the yeast; this practice is customary with wheat beers. Typically, when serving a hefeweizen, 90% of the contents are poured, and the remainder is swirled to suspend the sediment before pouring it into the glass. Alternatively, the bottle may be inverted prior to opening. Glass bottles are always used for bottle conditioned beers.

Many beers are sold in cans, though there is considerable variation in the proportion between different countries. In Sweden in 2001, 63.9% of beer was sold in cans.[133] People either drink from the can or pour the beer into a glass. Cans protect the beer from light (thereby preventing "skunked" beer) and have a seal less prone to leaking over time than bottles. Cans were initially viewed as a technological breakthrough for maintaining the quality of a beer, then became commonly associated with less expensive, mass-produced beers, even though the quality of storage in cans is much like bottles.[134] Plastic (PET) bottles are used by some breweries.[135]

Temperature

The temperature of a beer has an influence on a drinker's experience; warmer temperatures reveal the range of flavours in a beer but cooler temperatures are more refreshing. Most drinkers prefer pale lager to be served chilled, a low- or medium-strength pale ale to be served cool, while a strong barley wine or imperial stout to be served at room temperature.[136]

Beer writer Michael Jackson proposed a five-level scale for serving temperatures: well chilled (7 °C (45 °F)*) for "light" beers (pale lagers); chilled (8 °C (46 °F)*) for Berliner Weisse and other wheat beers; lightly chilled (9 °C (48 °F)*) for all dark lagers, altbier and German wheat beers; cellar temperature (13 °C (55 °F)*) for regular British ale, stout and most Belgian specialities; and room temperature (15.5 °C (59.9 °F)*) for strong dark ales (especially trappist beer) and barley wine.[137]

Drinking chilled beer began with the development of artificial refrigeration and by the 1870s, was spread in those countries that concentrated on brewing pale lager.[138] Chilling beer makes it more refreshing,[139] though below 15.5 °C (59.9 °F) the chilling starts to reduce taste awareness[140] and reduces it significantly below 10 °C (50 °F).[141] Beer served unchilled—either cool or at room temperature, reveal more of their flavours.[142] Cask Marque, a non-profit UK beer organisation, has set a temperature standard range of 12°-14 °C (53°-57 °F) for cask ales to be served.[143]

Vessels

Beer is consumed out of a variety of vessels, such as a glass, a beer stein, a mug, a pewter tankard, a beer bottle or a can. The shape of the glass from which beer is consumed can influence the perception of the beer and can define and accent the character of the style.[144] Breweries offer branded glassware intended only for their own beers as a marketing promotion, as this increases sales.[145]

The pouring process has an influence on a beer's presentation. The rate of flow from the tap or other serving vessel, tilt of the glass, and position of the pour (in the centre or down the side) into the glass all influence the end result, such as the size and longevity of the head, lacing (the pattern left by the head as it moves down the glass as the beer is drunk), and turbulence of the beer and its release of carbonation.[146]

Beer and society

In most societies, beer is the most popular alcoholic beverage.

Various social traditions and activities are associated with beer drinking, such as playing cards, darts, or other pub games; attending beer festivals; visiting a series of pubs in one evening; joining an organisation such as CAMRA; visiting breweries; beer-oriented tourism; or rating beer.[147] Drinking games, such as beer pong, are also popular.[148] A relatively new profession is that of the beer sommelier, who informs restaurant patrons about beers and food pairings.

Beer is considered to be a social lubricant in many societies[149] and is consumed in countries all over the world. There are breweries in Middle Eastern countries such as Iran and Syria, and in African countries. Sales of beer are four times those of wine, which is the second most popular alcoholic beverage.[150][151]

Health effects

The main active ingredient of beer is alcohol, and therefore, the health effects of alcohol apply to beer. The moderate consumption of alcohol, including beer, is associated with a decreased risk of cardiac disease, stroke and cognitive decline.[152][153][154][155] The long term health effects of continuous, heavy alcohol consumption can, however, include the risk of developing alcoholism and alcoholic liver disease.

Brewer's yeast is known to be a rich source of nutrients; therefore, as expected, beer can contain significant amounts of nutrients, including magnesium, selenium, potassium, phosphorus, biotin, chromium and B vitamins. In fact, beer is sometimes referred to as "liquid bread".[156] Some sources maintain that filtered beer loses much of its nutrition.[157][158]

A 2005 Japanese study found that low alcohol beer may possess strong anti-cancer properties.[159] Another study found nonalcoholic beer to mirror the cardiovascular benefits associated with moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages.[160] However, much research suggests that the primary health benefit from alcoholic beverages comes from the alcohol they contain.[161]

It is considered that overeating and lack of muscle tone is the main cause of a beer belly, rather than beer consumption. A recent study, however, found a link between binge drinking and a beer belly. But with most overconsumption, it is more a problem of improper exercise and overconsumption of carbohydrates than the product itself.[162] Several diet books quote beer as having an undesirably high glycemic index of 110, the same as maltose; however, the maltose in beer undergoes metabolism by yeast during fermentation so that beer consists mostly of water, hop oils and only trace amounts of sugars, including maltose.[163]

Nutritional information

1can of beer (356ml) contains:[164]

- Calories :153

- Fat(g): 0

- Carbohydrates(g): 12.64

- Fibers(g): 0

- Protein(g): 1.64

- Cholesterol(mg): 0

Related beverages

Around the world, there are a number of traditional and ancient starch-based beverages classed as beer. In Africa, there are various ethnic beers made from sorghum or millet, such as Oshikundu[165] in Namibia and Tella in Ethiopia.[166] Kyrgyzstan also has a beer made from millet; it is a low alcohol, somewhat porridge-like drink called "Bozo".[167] Bhutan, Nepal, Tibet and Sikkim also use millet in Chhaang, a popular semi-fermented rice/millet drink in the eastern Himalayas.[168] Further east in China are found Huangjiu and Choujiu—traditional rice-based beverages related to beer.

The Andes in South America has Chicha, made from germinated maize (corn); while the indigenous peoples in Brazil have Cauim, a traditional beverage made since pre-Columbian times by chewing manioc so that enzymes present in human saliva can break down the starch into fermentable sugars;[169] this is similar to Masato in Peru.[170]

Some beers which are made from bread, which is linked to the earliest forms of beer, are Sahti in Finland, Kvass in Russia and Ukraine, and Bouza in Sudan.

References

- ^ "Volume of World Beer Production". European Beer Guide. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 0-415-31121-7. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Rudgley, Richard (1993). The Alchemy of Culture: Intoxicants in Society. London: British Museum Press;. ISBN 978-0714117362.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Arnold, John P (2005). Origin and History of Beer and Brewing: From Prehistoric Times to the Beginning of Brewing Science and Technology. Cleveland, Ohio: Reprint Edition by BeerBooks. ISBN 0-9662084-1-2.

- ^ Joshua J. Mark (2011). Beer. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- ^ World's Best Beers: One Thousand ... – Google Books. books.google.com. 6 October 2009. ISBN 9781402766947. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ "Beer Before Bread". Alaska Science Forum #1039, Carla Helfferich. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b "Nin-kasi: Mesopotamian Goddess of Beer". Matrifocus 2006, Johanna Stuckey. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ a b Black, Jeremy A.; Cunningham, Graham; Robson, Eleanor (2004). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926311-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barth, Roger. The Chemistry of Beer, 3/e. 2011: ISBN 978-0-9847950-3-1

- ^ "Life's Little Mysteries.com – When Was Beer Invented?". lifeslittlemysteries.com. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ^ "Beer". Britannica.com.; Michael M. Homan, 'Beer and Its Drinkers: An Ancient near Eastern Love Story, Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 67, No. 2 (Jun., 2004), pp. 84–95.

- ^ "Archeologists Link Rise of Civilization and Beer's Invention – Tech Talk – CBS News". www.cbsnews.com. 8 November 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ McGovern, Patrick, Uncorking the Past, 2009, ISBN 978-0-520-25379-7. pp. 66-71

- ^ "Jar in Iranian Ruins Betrays Beer Drinkers of 3500 B.C. – New York Times". www.nytimes.com. 5 November 1992. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Dumper; Stanley, 2007, p.141.

- ^ "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "Li Wine: The Beer of Ancient China -China Beer Festivals 2009". www.echinacities.com. 15 July 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Standage, Tom (2006). A History of the World in Six Glasses. Westminster, MD: Anchor Books. p. 311. ISBN 9780385660877.

- ^ Mirsky, Steve (2007). "Ale's Well with the World". Scientific American. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dornbusch, Horst (27 August 2006). "Beer: The Midwife of Civilization". Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Protz, Roger (4 December 2004). "The Complete Guide to World Beer". Retrieved 21 September 2010.

When people of the ancient world realised they could make bread and beer from grain, they stopped roaming and settled down to cultivate cereals in recognisable communities.

- ^ "Prehistoric brewing: the true story". Archaeo News. 22 October 2001. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ "Beer-history". Dreher Breweries. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ^ Max Nelson, The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe pp2, Routledge (2005), ISBN 0-415-31121-7

- ^ Google Books Richard W. Unger, Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance pp57, University of Pennsylvania Press ( 2004), ISBN 0-8122-3795-1

- ^ Max Nelson, The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe pp110, Routledge (2005), ISBN 0-415-31121-7

- ^ "492 Years of Good Beer: Germans Toast the Anniversary of Their Beer Purity Law". Der Spiegel April 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c Cornell, Martyn (2003). Beer: The Story of the Pint. Headline. ISBN 0-7553-1165-5.

- ^ a b "Industry Browser — Consumer Non-Cyclical — Beverages (Alcoholic) – Company List". Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ a b "Beer: Global Industry Guide". Research and Markets. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Analysis: Premium Chinese beer a bitter brew for foreign brands". 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Breaking the Home Brewing Law in Alabama". Homebrew4u.co.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "[[Roger Protz]] tries his hand at brewing". Beer-pages.com. June 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ ABGbrew.com Steve Parkes, British Brewing, American Brewers Guild.

- ^ Goldhammer, Ted (2008), The Brewer's Handbook, 2nd ed., Apex, ISBN 978-0-9675212-3-7 pp. 181 ff.

- ^ Brewingtechniques.com, Randy Mosher, Parti-Gyle Brewing, Brewing Techniques, March/April 1994

- ^ "Copper Brewing Vessels". Msm.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Books.google.co.uk, Michael Lewis, Tom W. Young, Brewing, page 275, Springer (2002), ISBN 0-306-47274-0

- ^ beer-brewing.com Beer-brewing.com, Ted Goldammer, The Brewers Handbook, Chapter 13 – Beer Fermentation, Apex Pub (1 January 2000), ISBN 0-9675212-0-3. Retrieved 29 September 2008 Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Google Books Michael Lewis, Tom W. Young, Brewing pp306, Springer (2002), ISBN 0-306-47274-0. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Harold M. Broderick, Alvin Babb, Beer Packaging: A Manual for the Brewing and Beverage Industries, Master Brewers Association of the Americas (1982)

- ^ Alabev.com The Ingredients of Beer. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ beer-brewing.com Beer-brewing.com Ted Goldammer, The Brewers Handbook, Chapter 6 – Beer Adjuncts, Apex Pub (1 January 2000), ISBN 0-9675212-0-3. Retrieved 29 September 2008 Archived 2007-10-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Beerhunter.com Michael Jackson, A good beer is a thorny problem down Mexico way, What's Brewing, 1 October 1997. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ a b "Geology and Beer". Geotimes. 2004-08. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Beerhunder.com Michael Jackson, BeerHunter, 19 October 1991, Brewing a good glass of water. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ^ Wikisource 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Brewing/Chemistry. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Farm-direct.co.uk Oz, Barley Malt, 6 February 2002. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Smagalski, Carolyn (2006). "CAMRA & The First International Gluten Free Beer Festival". Carolyn Smagalski, Bella Online.

- ^ A. H. Burgess, Hops: Botany, Cultivation and Utilization, Leonard Hill (1964), ISBN 0-471-12350-1

- ^ a b Unger, Richard W (2004). Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 54–55. ISBN 0-8122-3795-1.

- ^ Books.google.co.uk Richard W. Unger, Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, University of Pennsylvania Press (2004), ISBN 0-8122-3795-1. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ "Heatherale.co.uk". Fraoch.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "La Brasserie Lancelot est située au coeur de la Bretagne, dans des bâtiments rénovés de l'ancienne mine d'Or du Roc St-André, construits au 19 ème siècle sur des vestiges néolithiques". Brasserie-lancelot.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Head Retention". BrewWiki. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Hop Products: Iso-Extract". Hopsteiner. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ beer.pdqguides.com PDQ Guides, Hops: Clever Use For a Useless Plan. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ^ cat.inist.fr, A better control of beer properties by predicting acidity of hop iso-α-acids, Blanco Carlos A.; Rojas Antonio; Caballero Pedro A.; Ronda Felicidad; Gomez Manuel; Caballero. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ^ Ostergaard, S., Olsson, L., Nielsen, J., Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000 64: 34–50

- ^ Google Books Paul R. Dittmer, J. Desmond, Principles of Food, Beverage, and Labor Cost Controls, John Wiley and Sons (2005), ISBN 0-471-42992-9

- ^ Google Books Ian Spencer Hornsey, Brewing pp221-222, Royal Society of Chemistry (1999), ISBN 0-85404-568-6

- ^ Web.mst.edu David Horwitz, Torulaspora delbrueckii. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ Google Books Y. H. Hui, George G. Khachatourians, Food Biotechnology pp847-848, Wiley-IEEE (1994), ISBN 0-471-18570-1

- ^ "Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter — A pint of cloudy, please". Beerhunter.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ EFSA.europa.eu Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies, 23 August 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Food.gov.uk Draft Guidance on the Use of the Terms ‘Vegetarian’ and ‘Vegan’ in Food Labelling: Consultation Responses pp71, 5 October 2005. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Giebel, Wieland, ed (1992). The New Germany. Singapore: Höfer Press Pte. Ltd.

- ^ BBC.bloomington.com

- ^ Microbrewery#Definition

- ^ "Brewer to snap up Miller for $5.6B". CNN. 30 May 2002. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ http://www.ab-inbev.com/documents/press_release.pdf

- ^ "New Statesman – What's your poison?". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Adelaide Times Online". Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ Papazian The Complete Joy of Homebrewing (3rd Edition), ISBN 0-06-053105-3

- ^ News.bbc.co.uk, Will Smale, BBC, 20 April 2006, Is today's beer all image over reality?. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ^ Sixpack, Joe (pseudonym for Don Russell), What the Hell am I Drinking, 2011. ISBN 978-1463789817

- ^ "Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter — How to save a beer style". Beerhunter.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Handbook of Brewing: Processes ... – Google Books. books.google.com. 4 June 2009. ISBN 9783527316748. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Google Books Lalli Nykänen, Heikki Suomalainen, Aroma of Beer, Wine and Distilled Alcoholic Beverages pp 13, Springer (1983), ISBN 90-277-1553-X

- ^ Google books F. G. Priest, Graham G. Stewart, Handbook of Brewing pp2, CRC Press (2006), ISBN 0-8247-2657-X

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Oborne, Peter. "Still bitter after all these years — Telegraph". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ "Roger Protz on India Pale ale". www.beer-pages.com. Retrieved 3 October 2010.

- ^ "Porter and Stout – CAMRA". www.camra.org.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ Amazon Online Reader : Stout (Classic Beer Style Series, 10)

- ^ "Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter – Porter casts a long shadow on ale history". www.beerhunter.com. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ Eric Warner, German Wheat Beer. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 1992. ISBN 978-0-937381-34-2

- ^ Beerhunter.com Michael Jackson, BeerHunter, The birth of lager, 1 March 1996. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Eurekalert.org Gavin Sherlock, Ph.D., EurekAlert, Brewing better beer: Scientists determine the genomic origins of lager yeasts, 10 September 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- ^ Webb, Tim; Pollard, Chris; and Pattyn, Joris; Lambicland: Lambikland, Rev Ed. (Cogan and Mater Ltd, 2004), ISBN 0-9547789-0-1

- ^ European Brewery Convention. "The Analysis Committee". Retrieved 5 August 2009.

The EBC Analysis Committee also works closely together with the 'American Society of Brewing Chemists' (ASBC) to establish so-called 'International methods' with world-wide recognition of applicability. A partnership declaration between EBC and ASBC has been signed. The integration of the IOB methods of analysis and EBC methods is nearing completion.

- ^ Lehigh Valley Homebrewers (2007). "Beer and Brewing Glossary". Retrieved 5 August 2009.

IBUs (International Bittering Units) – The accepted worldwide standard for measuring bitterness in beer, also known as EBU, based on the estimated alpha acid percentage of the hops used and the length of time they are boiled.

- ^ Google Books Fritz Ullmann, Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry Vol A-11 pp455, VCH (1985), ISBN 3-527-20103-3

- ^ British Bitter A beer style or a way of life?, RateBeer (January 2006). Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ Martyn Cornell, Beer: The Story of the Pint, Headline (2004), ISBN 0-7553-1165-5

- ^ BeerHunter Michael Jackson, A Czech-style classic from Belgium, Beer Hunter Online (7 September 1999). Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Google Books Costas Katsigris, Chris Thomas, The Bar and Beverage Book pp320, John Wiley and Sons (2006), ISBN 0-471-64799-3

- ^ Google Books J. Scott Smith, Y. H. Hui, Food Processing: Principles and Applications pp228, Blackwell Publishing (2004), ISBN 0-8138-1942-3

- ^ a b "The 48 proof beer". Beer Break. Vol. 2, no. 19. Realbeer. 13 February 2002. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ a b "Scots brewery releases world's strongest and most expensive beer | Aberdeen and North | STV News". news.stv.tv. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Pattinson, Ron (6 July 2007). European Beer Statistics: Beer production by strength. European Beer Guide. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ "Fourth Annual Bend Brew Fest". Bendbrewfest.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Beer Facts 2003 (PDF). The Brewers of Europe. 6 January 2004. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ Osborn, Andrew (21 June 2001). School dinner? Mine's a lager, please. London: Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ Vetter Brauhaus. Vetter Brauhaus. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ In 1994, the 33 Plato gave it the world's highest gravity. Though the beer can no longer make this claim, it is still one of the world's most renowned strong lagers. Rate Beer. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ "Schloss Eggenberg". Schloss-eggenberg.at. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Michael Jackson's Beer Hunter — Mine's a pint of Santa Claus". Beerhunter.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Hurlimann Samichlaus from Hürlimann (Feldschlösschen), a Doppelbock style beer: An unofficial page for Hurlimann Samichlaus from Hürlimann (Feldschlösschen) in Zürich, , Switzerland". Ratebeer.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "Parish: brewery detail from Beermad". www.beermad.org.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Brewery Souvenirs – Parish Brewery". www.brewerysouvenirs.co.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "BrewDog - Ghost Deer". www.brewdog.com. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ "Strongest beer in the world: Brewdog produces 41pc ale – Telegraph". London: telegraph.co.uk. 16 February 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2010.

- ^ "BBC News – 'World's strongest' beer with 32% strength launched". news.bbc.co.uk. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ "Buy Tactical Nuclear Penguin". BrewDog Beer. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "All We Can Eat – Beer: Anchors away". voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (26 November 2009). "Scottish brewer claims world's strongest beer | Society | guardian.co.uk". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- ^ "Willkommen beim Schorschbräu – Die handwerkliche Kleinbrauerei im Fränkischen Seenland". www.schorschbraeu.de. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "Schorschbräu Schorschbock 31% from Kleinbrauerei Schorschbräu – Ratebeer". ratebeer.com. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ "Hair of the Dog Dave from Hair of the Dog Brewing Company". www.ratebeer.com. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ Berkowitz, Ben (29 July 2010). "Brewer claims world's strongest beer | Reuters". www.reuters.com. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "Welkom bij Brouwerij Het Koelschip". www.brouwerijhetkoelschip.nl. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "How does the widget in a beer can work?". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ "Beer Temperature | Consumer". www.cask-marque.co.uk. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ "Draught Beats Bottled in Life Cycle Analysis". treehugger.com. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ "LCA of an Italian lager". springerlink.com. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Carbon Footprint of Fat Tire Amber Ale" (PDF). newbelgium.com. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ "Ecological effects of beer". ecofx.org. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ "When Passions Collide..." terrapass.com. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- ^ Google books Charles W. Bamforth, Beer: Tap Into the Art and Science of Brewing pp58-59, Oxford University Press US (2003), ISBN 0-19-515479-7. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Google Books T. Boekhout, Vincent Robert, Yeasts in Food: Beneficial and Detrimental Aspects pp370-371, Behr's Verlag DE (2003), ISBN 3-86022-961-3. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ "European Beer Statistics—beer sales by package type". European Beer Guide. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ "Beer Packaging Secrets". All About Beer Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

From a quality point of view, cans are much like bottles.

- ^ "Holsten-Brauerei Pet Line for Bottled Beer, Brunswick, Germany". Packaging-Gateway.com. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ RealBeer Beyond the coldest beer in town, 21 September 2000. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Michael Jackson, Michael Jackson's Beer Companion, Courage Books; 2 edition (27 February 2000), ISBN 0-7624-0772-7

- ^ Google Books Jack S. Blocker, David M. Fahey, Ian R. Tyrrell, Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History pp95, ABC-CLIO (2003), ISBN 157607833

- ^ Introductory chemistry: a foundation – Google Books. books.google.com. 2004. ISBN 9780618304998. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Google Books Howard Hillman, The New Kitchen Science pp178, Houghton Mifflin Books (2003), ISBN 0-618-24963-X

- ^ Google Books Robert J. Harrington, Food and Wine Pairing: A Sensory Experience pp 27–28, John Wiley and Sons (2007), ISBN 0-471-79407-4

- ^ Yahoo Lifestyle Holly Ramer, Set the perfect temperature for a drink and enjoy maximum flavour, The Associated press. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Cask Marque Standards & Charters. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ F. G. Priest, Graham G. Stewart, Handbook of brewing (2006), 48

- ^ "The Publican – Home – Beer Matters: How Miller Brands partners with licensees to drive sales". www.thepublican.com. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ Google Books Ray Foley, Heather Dismore, Running a Bar For Dummies pp 211–212, For Dummies (2007), ISBN 0-470-04919-7

- ^ Leslie Dunkling & Michael Jackson, The Guinness Drinking Companion, Lyons Press (2003), ISBN 158574617

- ^ Best Drinking Game Book Ever, Carlton Books (28 October 2002), ISBN 1-85868-560-5

- ^ Sherer, Michael (2001–06). "Beer Boss". Cheers. findarticles.com. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Beer Production Per Capita". European Beer Guide. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ^ Cazin, Natasha (20 July 2004). "Global wine market shows solid growth". Euromonitor International.

- ^ Stampfer MJ, Kang JH, Chen J, Cherry R, Grodstein F (2005). "Effects of moderate alcohol consumption on cognitive function in women". N Engl J Med. 352 (3): 245–53. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa041152. PMID 15659724.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hines LM, Stampfer MJ, Ma J (2001). "Genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase and the beneficial effect of moderate alcohol consumption on myocardial infarction". N Engl J Med. 344 (8): 549–55. doi:10.1056/NEJM200102223440802. PMID 11207350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berger K, Ajani UA, Kase CS (1999). "Light-to-moderate alcohol consumption and risk of stroke among U.S. male physicians". N Engl J Med. 341 (21): 1557–64. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911183412101. PMID 10564684.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mukamal KJ, Conigrave KM, Mittleman MA (2003). "Roles of drinking pattern and type of alcohol consumed in coronary heart disease in men". N Engl J Med. 348 (2): 109–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022095. PMID 12519921.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Bamforth, C. W. (17 September–20, 2006). "Beer as liquid bread: Overlapping science.". World Grains Summit 2006: Foods and Beverages. San Francisco, California, USA. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Harden A, Zilva SS (1924). "Investigation of Barley, Malt and Beer for Vitamins B and C". Biochem J. 18 (5): 1129–32. PMC 1259493. PMID 16743343.

- ^

"Why our beer is special and, dare we say, better; No filtering". Franconia Notch Brewing Company. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Non-alcoholic beer may help mice fight cancer". Reuters. 21 January 2005.

- ^ "Double benefit from alcohol-free beer". Food Navigator. 17 May 2005.

- ^ Edell, Dean (2004). Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 191–192.

- ^ "Drink binges 'cause beer belly'". BBC News. 28 November 2004. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Skilnik, Bob. Is there maltose in your beer?. Realbeer. Retrieved 23 December 2007.

- ^ http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/

- ^ "Recuperation" (PDF). Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ "EthnoMed: Traditional Foods of the Central Ethiopian Highlands". Ethnomed.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Surina, Asele; Mack, Glenn Randall (2005). Food culture in Russia and Central Asia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32773-4.

- ^ "Research & Culture, Kathmandu rich in Culture, Machchhendranath Temple, Akash Bhairav Temple, Hanumandhoka Durbar Square, Temple of Kumari Ghar, Jaishi Dewal, Martyr's Memorial (Sahid) Gate, Singha Durbar". Trek2himalaya.com. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- ^ Books.google.co.uk, Lewin Louis and Louis Levin, Phantastica: A Classic Survey on the Use and Abuse of Mind-Altering Plants, Inner Traditions / Bear & Company (1998), ISBN 0-89281-783-6

- ^ Anthropological Society of London (1863). The Anthropological Review. Trübner. ISBN 055956998X.

Bibliography

- Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079195..

- Archeological Parameters For the Origins of Beer. Thomas W. Kavanagh.

- The Complete Guide to World Beer, Roger Protz. ISBN 1-84442-865-6.

- The Barbarian's Beverage: a history of beer in ancient Europe, Max Nelson. ISBN 0-415-31121-7.

- The World Guide to Beer, Michael Jackson. ISBN 1-85076-000-4

- The New World Guide to Beer, Michael Jackson. ISBN 0-89471-884-3

- Beer: The Story of the Pint, Martyn Cornell. ISBN 0-7553-1165-5

- Beer and Britannia: An Inebriated History of Britain, Peter Haydon. ISBN 0-7509-2748-8

- The Book of Beer Knowledge: Essential Wisdom for the Discerning Drinker, a Useful Miscellany, Jeff Evans. ISBN 1-85249-198-1

- Country House Brewing in England, 1500–1900, Pamela Sambrook. ISBN 1-85285-127-9

- Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women's Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 , Judith M. Bennett. ISBN 0-19-512650-5

- A History of Beer and Brewing, I. Hornsey. ISBN 0-85404-630-5

- Beer: an Illustrated History, Brian Glover. ISBN 1-84038-597-9

- Beer in America: The Early Years 1587–1840—Beer's Role in the Settling of America and the Birth of a Nation, Gregg Smith. ISBN 0-937381-65-9

- Big Book of Beer, Adrian Tierney-Jones. ISBN 1-85249-212-0

- Gone for a Burton: Memories from a Great British Heritage, Bob Ricketts. ISBN 1-905203-69-1

- Farmhouse Ales: Culture and Craftsmanship in the Belgian Tradition, Phil Marowski. ISBN 0-937381-84-5

- The World Encyclopedia of Beer, Brian Glover. ISBN 0-7548-0933-1

- The Complete Joy of Homebrewing, Charlie Papazian ISBN 0-380-77287-6

- The Brewmaster's Table, Garrett Oliver. ISBN 0-06-000571-8

- Vaughan, J. G. (1997). The New Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854825-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Bacchus and Civic Order: The Culture of Drink in Early Modern Germany, Ann Tlusty. ISBN 0-8139-2045-0

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA