Kikinda

Кикинда

Kikinda Nagykikinda | |

|---|---|

Municipality and City | |

Kikinda City Hall | |

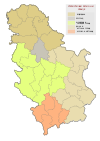

| Country | Serbia |

| Province | Vojvodina |

| District | North Banat |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Pavle Markov (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Kikinda | 782.0 km2 (301.93 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Kikinda | 38,065 |

| • Metro | 59,453 |

| Demonym(s) | Kikindjani, (sr) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 23300 |

| Area code | +381(0)230 |

| Car plates | KI |

| Website | www.kikinda.rs |

Kikinda (Serbian Cyrillic: Кикинда, pronounced [kǐkiːnda]) is a town and a municipality in Serbia, in the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is the administrative centre of the North Banat District. The town has 38,065 inhabitants, while the municipality has 59,453 inhabitants.

The modern city was founded in the 18th century. From 1774 to 1874 Kikinda was the seat of the District of Velika Kikinda, the autonomous administrative unit of Habsburg Monarchy. In 1893 Kikinda was granted the status of a town. The town became part of the Kingdom of Serbia (and Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes) in 1918. Kikinda used to be a very strong economic and industrial centre of Serbia and Yugoslavia up until the 1990s. Currently, the industry of Kikinda is in the middle of the transitional economic process.

In 1996, the well preserved archeological remnants of a half a million-year-old mammoth were excavated on the outer edge of the town area.[1] The mammoth called "Kika" has become one of the symbols of the town. Today it is exhibited in the National Museum of Kikinda. Other attractions of the city are the Suvača – a unique horse-powered dry mill, the annual Pumpkin Days[2] and the International Symposium of Sculpture "Terra".[3] The winter roosts of long-eared owl, with a large number of individuals, are easily accessible as they are situated in town parks and therefore they attract birdwatchers both from this country and abroad.

Name

In Serbian, the city is known as Kikinda (Кикинда), in Hungarian as Nagykikinda, in German as Gross Kikinda or Großkikinda, in Latin as Magna Kikinda, in Romanian as Chichinda Mare, in Slovak as Kikinda, in Rusyn as Кикинда, and in Croatian as Kikinda. Until 1947 it was known in Serbian as Velika Kikinda (Велика Кикинда).

The name of Kikinda is first found recorded at the beginning of the 15th century as Kokenyd, and most probably denoted, together with the name Ecehida, a number of small settlements, i.e. estates, firstly belonging to Hungarian and later to Serb local rulers. The name of the town first appears on a map of 1718 as Gross Kikinda, indicating an uninhabited area or a wasteland and not a settlement. The adjective Gross, Nagy or Velika (Great) in German, Hungarian and Serbian versions respectively, was in official use as the name of the town until the end of 1947.[4]

Coat of arms

The official coat of arms of the municipality dates back to the Austrian rule and the 18th century. It is derived from the coat of arms of the District of Velika Kikinda[5] which was issued by Maria Theresa of Austria on 12 November 1774. The Coat of Arms represents a hand holding a sabre on which an Ottoman Turkish head is impaled. It symbolizes the fight of Serbs and the majority ethnic Hungarians at that time, against the Turks during the Military Frontier period[5] and the military contributions of the population of Kikinda during the Austro-Ottoman Wars.

In 2007, Branislav Blažić, then president of the municipality of Kikinda, asked for the change of the coat of arms, criticizing it for being "morbid".[5] The idea proved very controversial, and ultimately the coat was not changed. Most critics of Blažić stated that the coat of arms is a part of the history and tradition of Kikinda and so an important factor of the city identity.[5]

The severed head of a Turk is also one of the common symbols in Austrian and Hungarian heraldry. It symbolizes the struggle of the Habsburg Empire (Austrian Empire) against Ottoman Empire during the Austro-Ottoman Wars.[6]

Inhabited places

The municipality of Kikinda comprises the city of Kikinda, nine villages and two hamlets. The nine villages are:

- Banatska Topola

- Banatsko Veliko Selo

- Bašaid

- Iđoš

- Mokrin

- Nakovo

- Novi Kozarci

- Rusko Selo

- Sajan (Template:Lang-hu)

The two hamlets are:

- Bikač, officially part of Bašaid

- Vincaid, officially part of Banatska Topola

Note: for settlement with Hungarian majority, name is also given in Hungarian.

Demographics (2011 census)

Ethnic groups

- Municipality[7]

- Serbs = 44,846 (75.43%)

- Hungarians = 7,270 (12.23%)

- Romani = 1,981 (3.33%)

- Others and undeclared = 5,356 (9.01%)

Most of the settlements in the municipality have an ethnic Serb majority, while one settlement has a Hungarian ethnic majority: Sajan (Hungarian: Szaján). Two others have over 20% Hungarians: Banatska Topola and Rusko Selo.

- Ethnic groups in the city of Kikinda[8]

- Serbs = 28,425 (74.67%)

- Hungarians = 4,504 (11.83%)

- Roma = 1,220 (3.21%)

- Others and undeclared = 3916 (10.29%).

Religion

Language

History

Origins

The city of Kikinda is located on a territory rich in remains of old and disappeared cultures. Numerous archeological findings are the testimony of people who lived here more than seven thousand years ago. However, the continuity of that duration was often broken. People arrived and departed, lived and disappeared, depending on various historical circumstances.

Medieval history

Two important medieval settlements existed near the location of modern Kikinda. Names of these settlements were Galad and Hološ.[9] Galad was one of the oldest Slavic settlements in northern Banat and was built by Slavic duke Glad in the 9th century.[10] In 1337, Galad was recorded as settlement populated almost exclusively by Serbs.[11] This settlement was destroyed during Austro-Ottoman wars in the end of 17th and beginning of the 18th century.[12]

Another settlement, Hološ (also known as Velika Holuša), was a local administrative center in the 17th century, during Ottoman administration.[12] This settlement was also destroyed in the end of the 17th century.[13]

According to some sources, an older settlement named Kekenj (Kekend, Keken) existed at this location.[14] The name of Kokenyd is first found recorded in 1423 as a property of the Hungarian king Sigismund.[citation needed] In 1558, this settlement was populated by Serbs.[14] It was deserted after Banat Uprising in 1594.[citation needed]

Modern history

The history of modern Kikinda can be traced in continuation for 250 years, from 1751–1752, when the area where the city is presently located was settled.[15][16] The first settlers were Serbs, a Habsburg border military corps who protected the border against the Ottomans on the Moriš and the Tisa rivers.[15] After the Požarevac peace treaty, where an agreement between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Ottoman Empire was reached, the Ottomans lost Banat and the Serbs lost their job.[citation needed] A newly founded settlement was soon organized, and the former border military corps started a new, land farming lifestyle. Several decades later, along with the Serbs, Germans (Banat Swabians), Hungarians, and Jews settled the area.

About twenty years after the establishment of the settlement, on 12 November 1774, the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, by way of a special charter, formed the Velikokikindski privileged district – Regio-privilegiatus Districtus Magnokikindiensis, as a distinct feudal governmental administrative unit with headquarters in Kikinda.[17] Besides Kikinda, the district included another nine settlements of the Serb border military establishments in North and Central Banat: Srpski Krstur, Jozefovo (today part of Novi Kneževac), Mokrin, Karlovo (today part of Novo Miloševo), Bašaid, Vranjevo (today part of Novi Bečej), Melenci, Kumane and Taraš. During that period, the inhabitants of these places had substantial economic, and even political privileges within the Habsburg Monarchy. The District functioned, with some interruptions, until 1876 when it was abolished, and Kikinda was allocated both organizationally and administratively to the direct authority of the Torontal County with headquarters in Veliki Bečkerek (today Zrenjanin), which covered most of the territory of present-day Serbian Banat.

In 1848/1849, the famous uprising of the Serbs in Vojvodina took place. At the beginning, Kikinda's citizens expressed, almost unanimously, social revolt, while later the riot turned into a national one, and Kikinda became part of the Serbian Voivodship, a Serb autonomous region within the Austrian Empire. During the war, Serbian and Hungarian governments came into power over the city one after the other, accompanied by great conflicts, suffering and destruction.[citation needed] It was one of the most difficult and most complex periods in the history of Kikinda.

Between 1849 and 1860 Kikinda was part of the Voivodship of Serbia and Tamiš Banat, a separate Austrian crown land. In 1860, this crown land was abolished, and Kikinda was included into Torontal county, in the Kingdom of Hungary after the compromise of 1867.

It is an interesting piece of information that at the end of the 19th century Kikinda was the most densely inhabited place in the Torontál County, with 22,000 inhabitants.[18] A railroad connecting Szeged, Kikinda and Timişoara was built in 1857 and is the oldest railroad on the territory of present-day Serbia.[citation needed] The period from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the First World War was a peaceful and fruitful period in the history of Kikinda and was marked by a strong economic and urban development of the city.[citation needed] Moreover, the picturesque core of the city, which was and still stands as a beautiful component of Kikinda even today, was formed, and the city received a defined local government in 1895 (statute, senate, town representative, mayor, etc.).[citation needed] According to the 1910 census, the population of Kikinda numbered 26,795 inhabitants, of whom 14,214 (53.00%) spoke Serbian, 5,968 (22.27%) Hungarian, and 5,855 (21.85%) German.[19]

A date around the end of the First World War (20 November 1918) denotes one of the most crucial moments in the history of Kikinda.[citation needed] The entry of the Serbian army into the city represented the achievement of the Serbs of Kikinda in striving to unite with Serbia. From 1 December 1918, the city was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Yugoslavia in 1929). However, the city suffered greatly in the economic realm, as it was located in the hinterland, between two borders, with communication lines disconnected. The period between the two world wars was not a period of economic prosperity. In 1921, the population of Kikinda numbered 25,774 people and included 15,000 (58%) Serbs and Croats, 5,500 (21%) Germans (Banat Swabians), 4,000 (16%) Hungarians, and 5% Romanians.[18][20] Between 1918 and 1922, Kikinda was part of Banat county, Between 1922 and 1929 it was part of Belgrade oblast, and between 1929 and 1941 it was part of Danube Banovina.

After only twenty years of peace, in 1941 Kikinda entered the stormy period of World War II, during which it was occupied by German troops. The Banat region to which Kikinda belonged to was made an autonomous region within Serbia and was placed under the control of the region's German minority. The city was overtaken on 6 October 1944,[citation needed] and since 1945, it has been part of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina within the new Socialist Yugoslavia.

The city's economic and political organization and structure changed significantly. There were changes in the ethnic structure of the city during and after the war. The German (about 22%) and Jewish (about 2%) populations were lost. In 1940, there were about 500 Jews in the town.[citation needed] In August, 1941, they were deported to the Sajmište death camp near Belgrade and murdered. In 1944, one part of German population left from the region, together with defeated German army. Those who remained were (during 1944–1948) detained in work camps. After abolishment of the camps, the remaining German population left from Yugoslavia because of economical reasons and went mostly to Austria and Germany.[22]

In 1948, just after the end of World War II, Kikinda had a population of 28,070.[23] The period from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s was, like the period from the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, characterized by a dynamic development of the city: new factories and production plants, new blocks of flats and residential settlements, various objects of general social interest, and paved streets definitely stressed and formed the urban dimension of Kikinda. In 1971 the city had a population of 37,487.[24]

City planning

The city belongs to the group of so-called planned organized settlements.[25] Plans of streets and crossroads were completed in the second half of the 18th century according to the standard city plans of the time used for the construction of new settlements in Banat.[citation needed] Those plans defined settlements with regularly lined and wide streets cutting at right angles, with a central town square, market place, church, city hall, school, pub, etc.

Economy

The principal branch of the city's economy is agriculture, with its 598.17 square kilometres (230.95 sq mi) of arable land. The annual production of wheat is about 60,000 tons, 114,670 tons of sunflower seeds. Soya, sugar beet and other fruits and vegetables are also produced.

Industrial production includes the production of oil derivatives by the "Naftagas" branch in Kikinda, metal processing, machine tools, special tools, car parts and flexible technologies by the former "Livnica Kikinda" (metal foundry) and IDA-Opel (now owned by Slovenian Cimos Koper), roof tile and brick production by "Toza Marković", the production of chemicals by "MCK" and "Hemik" and the processing of agricultural products by a number of factories.

Before the break-up of former Yugoslavia, hunting tourism was widespread in Kikinda. There are a number of hunting grounds in the municipality covering an area of 300 square kilometres (116 sq mi), mostly around the banks of the Danube-Tisa-Danube Canal, where rabbits, pheasants and deer are hunted.

Transport

Rail line Banatsko Aranđelovo – Kikinda – Romanian border at Jimbolia, part of the former Szeged – Timişoara railway is the second oldest railway in present-day Serbia.[26][27] The city is also connected by rail to Subotica and to Belgrade through Zrenjanin.

Regional roads connect Kikinda with all the neighbouring cities and villages. Buses operate regularly to the surrounding villages and major domestic and some European cities.

The only transport waterway in the municipality is the Danube-Tisa-Danube Canal. There is a dock which is used for industrial transport.

There is also the Kikinda Airport, a sports plane airstrip close to the city.[28] The local flying club organizes lessons in parachuting, aviation and space-modeling. Planes are also flown from this airstrip to dust agricultural fields.

Education

- Primary schools

There are eight primary schools in the city:

- Đura Jakšić Primary School [1]. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- Feješ Klara Primary School. Language of instruction: Serbian and Hungarian.

- Jovan Popović Primary School. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- Sveti Sava Primary School [2]. Languages of instruction: Serbian and Hungarian.

- Vuk Karadžić Primary School. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- Žarko Zrenjanin Primary School. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- 6 October Special Primary School. School for children with special needs. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- Slobodan Malbaški Primary Music school. Language of instruction: Serbian.

- Secondary schools

All secondary schools in Kikinda use Serbian as the language of instruction:

- Dušan Vasiljev Gymnasium, founded in 1858. Students can choose between four main courses: socio-linguistic, mathematics and natural sciences, informatics and general.

- Technical School

- Economics and Trade Secondary School

- Miloš Crnjanski Secondary Vocational School. The school offers courses in food processing, building, and health sciences.

- Higher School for the Education of Teachers

Main sights

The Suvača is a horse-powered dry mill. Kikinda has one of the three remaining such mills in Europe (the other two being in Szarvas, Hungary and Otok). There were many mills like this in the city, the largest recorded number being 51 in 1847. The only remaining mill was built in 1899 and was operational until 1945.[29]

Located in the center of the square, this Serbian Orthodox church was built in 1769. Icons of the iconostasis were done by Jakov Orfelin (nephew of Zacharius Orfelin) in 1773. Teodor Ilić Češljar is the author of the two large wall paintings "The Last Supper" and "Ascension of Jesus Christ" (1790). Both, the late baroque iconostasis and the wall paintings show significant influence of western European art of the period. New church bells were installed in 1899.

Serb Orthodox Holy Trinity monastery located in the south end of the city. It was built between 1885 and 1887 as a foundation of Melanija Nikolić-Gajčić.

The construction of the Roman Catholic Church in Kikinda church was started in 1808 and completed in 1811.

According to a popular belief, the treasure of Attila the Hun is buried somewhere on the territory of the municipality of Kikinda.

Among the birdwatchers Kikinda is known as the prime hotspot for observing winter roosts of long-eared owl with large number of individuals. The roosts are situated in city parks so they are easily accessible.

Culture

Cultural institutions

Situated on the city square, the building of the National Museum of Kikinda[30] was built in 1839. The building was at first the city curia and the seat of the District of Velika Kikinda until its abolishment in 1876. In 1946, the National Museum of Kikinda and the City Archive [3] were founded and housed in the building. The Museum boasts of numerous artifacts which are displayed in its four sections: archeological, historical, ethnological and naturalist. As of recently, it also possesses a mammoth skeleton[1] which was excavated on the premises of the "Toza Marković" brick factory in 1996.

The Jovan Popović National Library was founded in 1845 as Čitaonica Srbska (Serbian Reading Room). It was renamed in 1952 to Jovan Popović in honor of a prominent poet from Kikinda. Besides serving its primary function of loaning books, the library also organizes literary meetings, book promotions, seminars, lectures, exhibitions, and has published several works.[31]

Although the National Theater in Kikinda was founded only 50 years ago, Kikinda has a long theatrical tradition. Kikinda witnessed its first theatrical play in 1796 in German. The first play in Serbian was acted out in 1834. The theater is very popular with the citizens of Kikinda and has a continuous program all year round, including the summer when the stage is moved outside to the garden of the theater.[32]

Manifestations

The Pumpkin Days (Дани лудаје/Dani ludaje in Serbian) are an annual manifestation that takes place in mid-October.[2] Every year people from all over the region gather in Kikinda to take part in a competition of who has the largest pumpkin and longest gourd. The term ludaja is specific to the Kikinda region, while the common Serbian word for pumpkin is bundeva. Kikinda has a special relationship with this plant because throughout its history, the locals used to say that one can stand on a pumpkin while working in the fields and get a clear view of the whole city. This exaggeration was supposed to depict the flatness of the city's territory. A local standing on a pumpkin, dressed in traditional attire, and with his hand blocking the sun so that he can see into the distance, thus became the symbol for the region. A group of local enthusiasts started the Pumpkin Days manifestation in 1986 and it quickly attracted pumpkin and gourd lovers from all over the country. The three-day event also includes lectures and seminars on the advancement of pumpkin and gourd cultivation, a culinary competition in preparing meals from pumpkins and gourds, children's competitions in creating masks and sculptures, and various concerts and exhibitions. Over the past few years this event has gained prominence and has drawn visitors from Hungary, Romania and the former Yugoslav republics. The largest pumpkin measured at the event to date weighed 247 kg (545 lb), while the longest gourd was 213 centimeters in length. In 2006 the event celebrated its 20th anniversary and had the largest number of visitors so far, as well as a richer program. A tamburitza festival was included in the event, contributing to the authentic Banat experience.

Every year, since 1982, 6 to 8 world-renowned sculptors are invited to Kikinda at the premises of an old production plant of the Toza Marković brick factory for an international symposium of sculpture "Terra".[3] The symposium lasts throughout the month of July. Over the years, "Terra" has hosted sculptors from all corners of the world who are drawn by the unique and peaceful ambience of the studio. All sculptures are done in terracotta and some have appeared at the Venice Biennale. Over 300 sculptors have so far participated in the symposium and have together produced more than 500 sculptures. Plans for the construction of a "Terra" museum are underway in which all the sculptures will be exhibited in a modern setting adjacent to the old studio.

Media

- Newspapers

- Nove Kikindske Novine, weekly newspaper. Printed in Serbian, using the Cyrillic alphabet, with a supplement in Hungarian.[citation needed]

- Kikindske, weekly independent newspaper. Printed in Serbian, using the Latin alphabet, with a supplement in Hungarian.

- TV stations

- TV VK, independent TV station.[citation needed]

- TV Rubin, TV station favoring the local government.[citation needed]

- Radio stations

- VK Radio (frequency: 98.3 MHz), independent regional radio station

- Radio Kikinda (frequency: 93.3 МHz, ceased broadcasting in January 2016.), state-owned local station, which broadcast programs in both Serbian and Hungarian

- Radio Ami (frequency: 89.7 МHz), local commercial pop music radio station

Prominent citizens

- Miroslav Mika Antić, poet

- Jovan Ćirilov, dramaturge, poet, writer

- Dimitrije Injac, professional football player

- Milivoj Jugin, engineer and TV journalist in the field od exploring the space

- Dušan Vasiljev, poet

- Đura Jakšić, poet and painter, lived in Kikinda for some time

- Mladen Krstajić, former football player of football club Partizan Berlgrade

- Maja Latinović, supermodel

- Sava Savanović, also known as "Sveti Sava", underground media celebrity

- Jovan Popović, poet

- Srđan V. Tešin, writer and journalist

- Goran Živkov, politician

- Predrag Bubalo, politician, former Government minister

- Dragutin Ilić, boxer

- Srđan Srdić, writer

- Radivoj Berbakov, painter

- Peđa Krstin, professional tennis player

- Mario Bojić, publicist

- Dajana Butulija, professional basketball player

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Kikinda is twinned with:

|

|

Awards

In 2003, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Mission to Serbia awarded the Municipality of Kikinda with the Municipal Award for Tolerance.[34]

Climate

Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfb" (Marine West Coast Climate/Oceanic climate).[35]

| Climate data for Kikinda (1981–2010, extremes 1961–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

37.5 (99.5) |

40.0 (104.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

37.4 (99.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

40.0 (104.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

17.7 (63.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

28.4 (83.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.3 (43.3) |

11.9 (53.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.1 (34.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.1 (26.4) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −29.8 (−21.6) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−7.7 (18.1) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34.3 (1.35) |

26.8 (1.06) |

33.1 (1.30) |

43.8 (1.72) |

53.9 (2.12) |

75.5 (2.97) |

56.1 (2.21) |

49.6 (1.95) |

50.4 (1.98) |

41.1 (1.62) |

45.2 (1.78) |

46.5 (1.83) |

556.3 (21.90) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 130 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86 | 80 | 71 | 66 | 64 | 66 | 64 | 65 | 71 | 75 | 82 | 87 | 73 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 67.8 | 103.2 | 154.2 | 198.3 | 256.9 | 275.6 | 309.3 | 285.9 | 207.6 | 165.7 | 94.5 | 58.5 | 2,177.6 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[36] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Municipalities and cities of Serbia

- List of places in Serbia

- List of cities, towns and villages in Vojvodina

- North Banat District

References

General references

- Brane Marijanović et al. Kikinda: istorija, kultura, sela, privreda, sport, turizam, Novi Sad: Prometej, 2002.

- Jovan M. Pejin, Iz prošlosti Kikinde, Kikinda: Istorijski arhiv & Komuna, 2000.

- Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003.

- Dr Slobodan Ćurčić, Naselja Banata – geografske karakteristike, Novi Sad, 2004.

Notes

- ^ a b KIKA Online

- ^ a b KIKA Online: Dani ludaje u Kikindi... Template:Sr icon

- ^ a b The "TERRA" Centre for fine and applied arts

- ^ Kikinda Online: Istorija>NAZIV Template:Sr icon

- ^ a b c d http://www.kikinda.co.rs: Blažić se stidi kikindskog grba (trans: Blažić Ashamed of the Kikinda Coat of Arms), 30 Jun 2007 Template:Sr icon

- ^ A Note on Hungarian Heraldry by François Velde, August 1998

- ^ "Population by ethnicity – Kikinda, Total". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS). Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ "Population by ethnicity – Kikinda, Urban settlements". Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia (SORS). Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ^ Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, pages 14–16.

- ^ Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, pages 14–15.

- ^ Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 15.

- ^ a b Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 16.

- ^ Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 17.

- ^ a b Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 27.

- ^ a b Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 28.

- ^ Dr Slobodan Ćurčić, Naselja Banata – geografske karakteristike, Novi Sad, 2004, page 187.

- ^ Jovan M. Pejin, Iz prošlosti Kikinde, Kikinda, 2000, page 34.

- ^ a b http://joomla.kikindske.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=45&Itemid=23

- ^ Milivoj Rajkov, Istorija grada Kikinde do 1918. godine, Kikinda, 2003, page 200.

- ^ "Free Website Hosting with FreeWebsiteHosting.com". Lsvki.freewebsitehosting.com. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Place where Kikinda Synagogue once was

- ^ Nenad Stefanović, Jedan svet na Dunavu, Beograd, 2003, pages 175–176.

- ^ Columbia-Lippincott Gazeteer (1951) p. 944

- ^ Britannica, 15th Ed. (1984) Vol. 5, p. 805.

- ^ http://www.biserka.in.rs/page60.html An organized village

- ^ "Construction of Railway Lines in Slovenia". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "ŽELEZNICE SRBIJE - Istorijat železnice". Zeleznicesrbije.com. 31 May 1970. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ http://www.aeroklubkikinda.rs/Info_eng.htm [dead link]

- ^ Kikindski mlin: Mlin nekad / Kikindska suvača Template:Sr icon

- ^ http://www.muzejkikinda.com/

- ^ Kikinda Online: Narodna biblioteka "Jovan Popović" Template:Sr icon

- ^ Kikinda Online: Narodno pozorište

- ^ [http://www.zilina.sk/mesto-zilina-o-meste-

partnerske-mesta "Žilina - oficiálne stránky mesta: Partnerské mestá Žiliny [Žilina: Official Partner Cities]"]. © 2008 MaM Multimedia, s.r.o.. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help); line feed character in|url=at position 43 (help) - ^ "Daily Bulletin". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Climate Summary for Kikinda

- ^ "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1981–2010" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved 9 April 2015.