V. S. Ramachandran

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran | |

|---|---|

Ramachandran at the 2011 Time 100 gala | |

| Born | August 10, 1951 |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Research in neurology, visual perception, phantom limbs, synesthesia, autism, body integrity identity disorder |

| Awards | Ariens-Kappers medal (1999), Padma Bhushan (2007), Honorary Fellow, Royal College of Physicians (2014) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | University of California, San Diego |

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran (born August 10, 1951) is a neuroscientist known primarily for his work in the fields of behavioral neurology and visual psychophysics. He is currently a Professor in the Department of Psychology and the Graduate Program in Neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego.

Ramachandran is the author of several books that have garnered widespread public interest. These include Phantoms in the Brain (1998), "A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness" (2004) and The Tell-Tale Brain (2010). In addition to his books, Ramachandran is known for his engaging style as a public lecturer. He has presented keynote addresses and public lectures in the U.S., Canada, Britain, Australia and India. His work in behavioral neurology has been widely reported by the media and he has appeared in numerous television programs.

Ramachandran has been called "The Marco Polo of neuroscience" by Richard Dawkins and "the modern Paul Broca" by Eric Kandel.[1] In 2011, Time listed him as one of "the most influential people in the world" on the "Time 100" list.[2][3]

Ramachandran has also encountered criticism from some neuroscientists. Greg Hickok, Professor of Cognitive Sciences at UC Irvine, has expressed the opinion that Ramachandran engages in broad speculations that are not supported by a rigorous analysis of the facts: "The question is whether the science that is communicated is legitimate, i.e., based on a rigorous analysis of facts (such that it can be taken seriously by bench scientists) or whether the ideas are just wild speculations spun together into a nice story."[4] In 2012, neuropsychologist Peter Brugger at the University Hospital of Zürich criticized Ramachandran's book The Tell-Tale Brain as a pop-neuroscience book providing vague answers to big questions.[5]

Early life and education

Vilayanur Subramanian Ramachandran (in accordance with some Tamil family name traditions, the town of his family's origin, Vilayanur, is placed first) was born in 1951 in Tamil Nadu, India, into a Brahmin family.[6][7] His father, V.M. Subramanian, was an engineer who worked for the U.N. Industrial Development Organization and served as a diplomat in Bangkok, Thailand.[8] Ramachandran spent much of his youth moving among several different posts in India and other parts of Asia.[9] As a young man Ramachandran attended schools in Madras, and British schools in Bangkok.[10] He pursued many scientific interests, including conchology.[9] Ramachandran obtained an M.B.B.S. from the University of Madras in Chennai, India,[11] and subsequently obtained a Ph.D. from Trinity College at the University of Cambridge. He then spent two years at Caltech, as a research fellow working with Jack Pettigrew. He was appointed Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of California, San Diego in 1983, and has been a full professor there since 1998.

Scientific career

Ramachandran's early research was on human visual perception using psychophysical methods to draw clear inferences about the brain mechanisms underlying visual processing. Ramachandran is credited with discovering several new visual effects related to stereoscopic "capture" using illusory contours, stereoscopic learning, shape-from-shading, and motion capture. In the early 1990s Ramachandran began to focus on neurological syndromes such as phantom limbs, body integrity identity disorder and the Capgras delusion. He has also contributed to the understanding of synesthesia[2][9] and is known for inventing the mirror box.

Ramachandran is noted for his use of experimental methods that make relatively little use of complex technologies such as neuroimaging. Despite the apparent simplicity of his approach, he has generated many new ideas about the brain.[12] Ramachandran is the director of a neuroscience research group known as the Center for Brain and Cognition.[13] This group, made up of students and researchers from different universities, is affiliated with the Department of Psychology at UCSD. Members of the CBC have published articles on a range of topics related to neuroscience.[13][14]

Best Known Theories & Research

Phantom limbs

When an arm or leg is amputated, patients often continue to feel vividly the presence of the missing limb as a "phantom limb" (an average of 80%). Building on earlier work by Ronald Melzack (McGill University) and Timothy Pons (NIMH), Ramachandran theorized that there was a link between the phenomenon of phantom limbs and neural plasticity in the adult human brain. In particular, he theorized that the body image maps in the somatosensory cortex are re-mapped after the amputation of a limb. In 1993, working with T.T. Yang who was conducting MEG research at the Scripps Research Institute,[15] Ramachandran demonstrated that there had been measurable changes in the somatosensory cortex of a patient who had undergone an arm amputation.[16][17] Ramachandran theorized that there was a relationship between the cortical reorganization evident in the MEG image and the referred sensations he had observed in other subjects.[18] Ramachandran believed that the non-painful referred sensations he observed were the "perceptual correlates" of cortical reorganization; however research by neuroscientists in Europe demonstrated that the cortical reorganization seen in MEG images was related to pain rather than non-painful referred sensations.[19] The question of which neural processes are related to non-painful referred sensations remains unresolved.

Mirror visual feedback

Ramachandran is credited with the invention of the mirror box and the introduction of mirror visual feedback as a treatment for phantom limb paralysis. Ramachandran found that in some cases restoring movement to a paralyzed phantom limb reduced pain as well.[20] Small scale research studies using mirror therapy to treat phantom limb pain and complex regional pain syndrome have produced promising results[21] but there is currently no consensus as to the effectiveness of mirror therapy in reducing pain.[22][23] The applications of mirror therapy are still under experimental evaluation.[24]

Projected images of the body during sleep paralysis

In 2014 Baland Jalal and V.S. Ramachandran published an article in Medical Hypotheses [25] in which they argued that the "bedroom intruder" often experienced during sleep paralysis may be related to the phenomenon of phantom limbs:

"We postulate that a functional disturbance of the right parietal cortex explains the shadowy nocturnal bedroom intruder halluci-nation during SP. This hallucination may arise due to a disturbance in the multisensory processing of body and self at the temporopa-rietal junction. We specifically propose that this perceived intruder is the result of a hallucinated projection of the genetically ‘‘hard-wired’’ body image (homunculus),in the right parietal region; namely, the same circuits that dictate aesthetic and sexual preference of body morphology—which includes neural circuitry connecting visual centers and limbic structures...In short, this may explain why SP experiencers often see this human-like shadowy figure—a figure which usually fits the human morphology, in both size and shape."

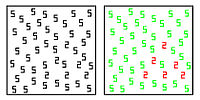

Neural cross-wiring: synesthesia and metaphors

Ramachandran has theorized that synesthesia arises from a cross-activation between brain regions.[26][27] Consistent with this model, Ramachandran and his graduate student, Ed Hubbard, conducted research that found increased activity in color selective areas in synesthetes compared to non-synesthetes using fMRI.[27][28] Using MEG, they also showed that differences between synesthetes and non-synesthetes begin very quickly after the grapheme is presented.[29] As of 2015, there is no consensus about the neurological basis of synesthesia. In 2015, Jean-Michel Hupe and Michel Dojat published a review of the neuroimaging literature on synesthesia that concluded that the neurological correlates of synesthesia have not been established.[30]

Ramachandran has speculated that synesthesia and conceptual metaphors may share a common basis in cortical cross-activation. In 2003 Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard published a paper in which they speculated that the angular gyrus is at least partially responsible for understanding metaphors.[31] More recently (2014), Ramchandran and Baland Jalal published a paper in which they speculated that there is evidence of "metaphor blindness" in a small subset of college students; "Metaphor blindness" refers to the reduced ability in otherwise normal individuals to comprehend metaphors of language, while showing no signs of other language deficits. The authors speculated that "metaphor blindness" might result from minor congenital lesions in the left inferior parietal lobule (mimicking those found among neurological patients).

Mirror neurons

Ramachandran is known for advocating the importance of mirror neurons. Ramachandran has stated that the discovery of mirror neurons is the most important unreported story of the last decade.[32] (Mirror neurons were first reported in a paper published in 1992 by a team of researchers led by Giacomo Rizzolatti at the University of Parma.[33]) In 2000, Ramachandran made a prediction that "mirror neurons will do for psychology what DNA did for biology: they will provide a unifying framework and help explain a host of mental abilities that have hitherto remained mysterious and inaccessible to experiments."[34][35]

Ramachandran has speculated that research into the role of mirror neurons will help explain a variety of human mental capacities such as empathy, imitation learning, and the evolution of language. Ramachandran has also theorized that mirror neurons may be the key to understanding the neurological basis of human self-awareness.[36][37]

In The Tell-Tale Brain (2011), Ramachandran speculates that mirror neurons may play a role in pseudocyesis (false pregnancy). He states "Much more bizarre is the Covade syndrome, in which men in Lamaze classes start developing pseudocyesis, or false signs of pregnancy. Perhaps mirror neuron activity results in the release of empathy hormones such as prolactin, which act on the brain and body to generate a phantom pregnancy."[38]

Many of Ramachandran's ideas about the significance of mirror neurons have been challenged by neuroscientists. As Christian Jarrett points out in a December 2013 article for Wired:[39]

a detailed investigation earlier this year found little evidence to support [Ramachandran's] theory about autism. Other experts have debunked Ramachandran's claims linking mirror neurons to the birth of human culture. The activity of mirror neurons can be altered by simple and brief training tasks showing that these cells are just as likely to have been shaped by culture as the shaper of it.

Theories of autism

In 1999, Ramachandran, in collaboration with then post-doctoral fellow Eric Altschuler and colleague Jaime Pineda, was one of the first to suggest that a loss of mirror neurons might be the key deficit that explains many of the symptoms and signs of autism spectrum disorders.[40] Between 2000 and 2006 Ramachandran and his colleagues at UC San Diego published a number of articles in support of this theory, which became known as the "Broken Mirrors" theory of autism.[41][42][43] Ramachandran and his colleagues did not measure mirror neuron activity directly; rather they demonstrated that children with ASD showed abnormal EEG responses (known as Mu wave suppression) when they observed the activities of other people.

In 2006, Ramachandran conducted an interview with Frontline, India's National Magazine, in which he stated that "One of the things we have discovered in our lab is the cause of the cruel disorder called autism.....the impoverishment of the mirror neuron system explains the symptoms that are unique to autism alone and are not seen in any other disorders...in short we found the cause for autism in 2000."[44]

Ramachandran's claim that dysfunctional mirror neuron systems (MNS) are the cause of autism remains controversial. In his 2011 review of The Tell-Tale Brain, Simon Baron-Cohen, Director of the Autism Research Center at Cambridge University, states that "As an explanation of autism, the [Broken Mirrors] theory offers some tantalizing clues; however, some problematic counter-evidence challenges the theory and particularly its scope."[45]

Recognizing that dysfunctional mirror neuron systems cannot account for the wide range of symptoms that are included in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Ramachandran has theorized that childhood temporal lobe epilepsy and olfactory bulb dysgenesis may also play a role in creating the symptoms of ASD. In 2010 Ramachandran stated that "The olfactory bulb hypothesis has important clinical implications" and announced that his group would undertake a study "comparing olfactory bulb volumes in individuals with autism with those of normal controls."[46]

Neural basis of religious experience

In a 1997 Society for Neuroscience talk, Ramachandran hypothesized that there may be a neural basis for some religious experiences. He stated that "There may be dedicated neural machinery in the temporal lobes concerned with religion. This may have evolved to impose order and stability on society."[47] Ramachandran described an experiment in which he measured the galvanic skin responses of two subjects who had experienced temporal lobe seizures. Ramachandran measured the subjects' responses to a mixture of religious, sexual and neutral words and images and found that religious words and images elicited an unusually high response.[48] Ramachandran has also discussed his ideas about the neural basis of religion in a number of talks and in Phantoms In The Brain.[49] He cautions that his ideas are tentative, and so far he has not published any research on this subject.[50][51]

Rare neurological syndromes

Capgras delusion

In collaboration with William Hirstein, Ramachandran published a paper in 1997 in which he presented a theory regarding the neural basis of Capgras delusion, a delusion in which family members and other loved ones are thought to be replaced by impostors. Prior to Ramachandran's 1997 paper, psychologists HD Ellis and Andy Young had theorized that Capgras delusion was created by a neurological disconnection between facial recognition and emotional arousal.[52] Based on the evaluation of a single subject, who did not manifest complex psychological symptoms, Ramachandran and Hirstein hypothesized that Capgras delusion involves memory management problems, in addition to a disconnection between facial recognition and emotional arousal. According to their theory, a person suffering from Capgras delusion loses the ability to manage memories effectively. Instead of a continuum of memories that constitute a unified sense of self, each memory takes on its own categorical sense of self.[53]

Apotemnophilia and xenomelia

In 2008, Ramachandran, along with David Brang and Paul McGeoch, published the first paper to theorize that apotemnophilia is a neurological disorder caused by damage to the right parietal lobe of the brain.[54] This rare disorder, in which a person desires the amputation of a limb, was first identified by John Money in 1977. Building on medical case studies that linked brain damage to syndromes such as somatoparaphrenia (lack of limb ownership) Ramachandran speculated that the desire for amputation could be related to changes in the right parietal lobe. In 2011 Ramachandran and Paul McGeoch, MD, carried out an experiment involving four subjects in which MEG scans showed that the right superior parietal lobe was unresponsive to tactile stimulation of limb areas that the subjects wished to have amputated.[55] The question of which areas of the brain may be linked to syndromes such as somatopraraphrenia remains unresolved.[56] McGeoch and Ramachandran introduced the word "Xenomelia" to describe this syndrome.[57]

Alternating gender incongruity (AGI)

In 2012, Case and Ramachandran reported the results of a survey of bigender individuals who experience involuntary alternation between male and female states. Case and Ramachandran hypothesized that gender alternation may reflect an unusual degree (or depth) of hemispheric switching, and the corresponding suppression of sex appropriate body maps in the parietal cortex. They stated that "we hypothesize that tracking the nasal cycle, rate of binocular rivalry, and other markers of hemispheric switching will reveal a physiological basis for AGI individuals' subjective reports of gender switches...We base our hypotheses on ancient and modern associations between the left and right hemispheres and the male and female genders."[58][59][60]

Testimony at the Lisa Montgomery trial

In 2007, Ramachandran served as an expert witness on pseudocyesis (false pregnancy) at the trial of Lisa M. Montgomery. In 2004 Montgomery strangled Bobby Jo Stinnett until unconscious and then removed her unborn child with a knife. Ramachandran testified that Montgomery suffered from delusions created by severe pseudocyesis disorder and stated that she was not responsible for her actions. Federal prosecutor Roseann Ketchmark characterized Ramachandran's theory as "voodoo science."[61][62][63]

Awards and honors

Ramachandran was elected to a visiting fellowship at All Souls College, Oxford (1998–1999). In addition, he was a Hilgard visiting professor at Stanford University in 2005. He has received honorary doctorates from Connecticut College (2001) and the Indian Institute of Technology, Madras (2004).[64] Ramachandran received the annual Ramon y Cajal award (2004) from the International Neuropsychiatry Society, and the Ariëns Kappers Medal from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Sciences for his contributions to Neuroscience (1999). He shared the 2005 Henry Dale Prize with Michael Brady of Oxford, and, as part of the award was elected an honorary life member of the Royal institution for "outstanding research of an interdisciplinary nature".[65] In 2007, the President of India conferred on him the third highest civilian award and honorific title in India, the Padma Bhushan.[66] In 2008, he was listed as number 50 in the Top 100 Public Intellectuals Poll.[67]

Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani

An interest in paleontology led Ramachandran to purchase a fossilised dinosaur skull originating from the Gobi Desert which, in 2009, was named after him as Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani.[68] A minor controversy surfaced around the provenance of this skull when claims were made that it was removed from the desert without permission and sold without proper documentation. Ramachandran, who purchased the fossil in Tucson, Arizona, says that he would be happy to repatriate the fossil to the appropriate nation if and when someone shows him "evidence it was exported without permit". In the meantime, the specimen is being kept at the Victor Valley Museum in Apple Valley, California.[69]

Books authored

- Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind, coauthor Sandra Blakeslee, 1998 (ISBN 0-688-17217-2).

- The Encyclopedia of the Human Brain (editor-in-chief) (ISBN 0-12-227210-2).

- The Emerging Mind, 2003 (ISBN 1-86197-303-9).

- A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness: From Impostor Poodles to Purple Numbers, 2005 (ISBN 0-13-187278-8; paperback edition).

- The Tell-Tale Brain: A Neuroscientist's Quest for What Makes Us Human, 2010 (ISBN 978-0-393-07782-7).

See also

- Body image

- Oliver Sacks

- Sound symbolism (phonaesthesia)

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

References

- ^ A Brief Tour of Human Consciousness, 2004, Back Cover

- ^ a b "V.S. Ramachandran — Time 100". April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011. The citation by Tom Insel, Director of NIH, reads: "Once described as the Marco Polo of neuroscience, V.S. Ramachandran has mapped some of the most mysterious regions of the mind. He has studied visual perception and a range of conditions, from synesthesia to autism. V.S. Ramachandran is changing how our brains think about our minds."

- ^ In public polling of the people included in the 2011 list, Ramachandran ranked 97 out of 100.[1]

- ^ "Talking Brains Blog site, August 14 2012

- ^ Brugger, Peter, Book Review, Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, Vol. 17, Issue 4, 2012

- ^ Andrew Anthony (January 30, 2011). "VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Brain Games

- ^ The Science Studio Interview, June 10, 2006, transcript

- ^ a b c Colapinto, J (May 11, 2009). "Brain Games; The Marco Polo of Neuroscience". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramachandran V.S.,The Making of a Scientist,essay included in Curious Minds:How a Child Becomes a Scientist,page 211 [2]

- ^ Caltech Catalog,1987-1988, page 325

- ^ Anthony, VS Ramachandran: The Marco Polo of neuroscience, The Observer, January 29, 2011.

- ^ a b http://cbc.ucsd.edu/research.html

- ^ Office of Research Affairs,UCSD

- ^ Yang, UCSD Faculty web page Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yang TT, Gallen CC, Ramachandran VS, Cobb S, Schwartz BJ, Bloom FE (February 1994). "Noninvasive detection of cerebral plasticity in adult human somatosensory cortex". NeuroReport. 5 (6): 701–4. doi:10.1097/00001756-199402000-00010. PMID 8199341.

- ^ For a competing view, see: Flor et al., Nature Reviews, Vol 7, November 2006 [3][permanent dead link]

- ^ Ramachandran, Rogers-Ramachandran, Stewart, Perceptual correlates of massive cortical reorganization, Science, 1992, Nov 13, 1159-1160

- ^ Reprogramming the cerebral cortex: plasticity following central and peripheral lesions, Oxford, 2006, Edited by Stephen Lomber, pages 334

- ^ Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D (April 1996). "Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 263 (1369): 377–86. doi:10.1098/rspb.1996.0058. PMID 8637922. Retrieved 2008-09-23.

- ^ Chan, B; Witt, R; Charrow, A; Magee, A; Howard, R; Pasquina, P. Mirror Therapy for Phantom Limb Pain, N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2206–2207November 22, 2007.

- ^ Flor,H, Maladaptive plasticity, memory for pain and phantom limb pain: review and suggestions for new therapies, Expert Reviews, Neurotherapeutics,8(5) 2008,[4]

- ^ Moseley, L; Flor, H. Targeting Cortical Representations in the Treatment of Chronic Pain: A Review Archived 2012-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, XX(X) 1–7, 2012.

- ^ Subedi, Bishnu; Grossberg, George. Phantom Limb Pain: Mechanisms and Treatment Approaches, Pain Research and Treatment, Vol 2011, Article ID 864605.

- ^ Medical Hypothesis, November 16, 2014

- ^ Ramachandran VS, Hubbard EM (2001). "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies. 8 (12): 3–34.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hubbard EM, Arman AC, Ramachandran VS, Boynton GM (March 2005). "Individual differences among grapheme-color synesthetes: brain-behavior correlations" (PDF). Neuron. 45 (6): 975–85. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.008. PMID 15797557. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- ^ Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (2005). "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia" (PDF). Neuron. 48 (3): 509–520. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.012. PMID 16269367.

- ^ Brang D, Hubbard EM, Coulson S, Huang M, Ramachandran VS (2010). "Magnetoencephalography reveals early activation of V4 in grapheme-color synesthesia". NeuroImage. 53 (1): 268–274. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.008. PMID 20547226.

- ^ Hupé JM, Dojat M (2015). "A critical review of the neuroimaging literature on synesthesia". Front Hum Neurosci. 9: 103. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00103. PMC 4379872. PMID 25873873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ramachandran, Hubbard, "Neural cross wiring and synesthesia", Journal of Vision, Dec 2000 [5]

- ^ Ramachandran, V.S. (June 1, 2000). "Mirror neurons and imitation learning as the driving force behind "the great leap forward" in human evolution". Edge Foundation web site. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Rizzolatti, G., Fabbri-Destro, M, "Mirror Neurons: From Discovery to Autism" Experimental Brain Research, (2010)200:223–237 [6]

- ^ Jarrett Christian, Brain Myths,Psychology Today, December 10,2012

- ^ Baron-Cohen, Making Sense of the Brain's Mysteries, American Scientist, On-line Book Review, July–August, 2011 [7]

- ^ Oberman, L.M.; Ramachandran, V.S. (2008). "Reflections on the Mirror Neuron System: Their Evolutionary Functions Beyond Motor Representation". In Pineda, J. A. (ed.). Mirror Neuron Systems: The Role of Mirroring Processes in Social Cognition. Contemporary Neuroscience. Humana Press. pp. 39–62. ISBN 978-1-934115-34-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Ramachandran, V.S. (January 1, 2009). "Self Awareness: The Last Frontier". Edge Foundation web site. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Ramachandran, The Tell-Tale Brain, page 361

- ^ Brain Watch,Dec 13,2013

- ^ E.L. Altschuler, A. Vankov, E.M. Hubbard, E. Roberts, V.S. Ramachandran and J.A. Pineda (2000). "Mu wave blocking by observer of movement and its possible use as a tool to study theory of other minds". 30th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oberman LM, Hubbard EM, McCleery JP, Altschuler EL, Ramachandran VS, Pineda JA (2005). "EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectrum disorders" (PDF). Cognitive Brain Research. 24 (2): 190–198. doi:10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.01.014. PMID 15993757.

- ^ Ramachandran, V.S.; Oberman, L.M. (October 16, 2006). "Broken Mirrors: A Theory of Autism" (PDF). Scientific American. 295 (5): 62–69. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1106-62. PMID 17076085.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Oberman LM, Ramachandran VS (2007). "The simulating social mind: the role of the mirror neuron system and simulation in the social and communicative deficits of autism spectrum disorders" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 133 (2): 310–327. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.310. PMID 17338602.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Interview with Sashi Kumar, Frontline,Vol 23,Issue 06,Mar 25, 2006 Archived 2010-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Baron-Cohen,Simon,"Making Sense of the Brain's Mysteries, American Scientist, On-line Book Review, July–August,2011 [8]

- ^ Brang,D, Ramachandran,VS, Olfactory bulb dysgenesis, mirror neuron system dysfunction, and autonomic dsyregulation as the neural basis for autism, Medical Hypotheses, 74, 2010, 919-921 [9]

- ^ Times of London, 1997

- ^ Scientific nautalism and the neurology of religious experience, Ratcliffe, Matthew, University of Durham, 2003,[10]

- ^ Phantoms In The Brain, Chapter 9

- ^ Youtube talk at the Salk Institute

- ^ Independent.co.uk Website

- ^ Ellis MD, Young, Accounting for delusional misidentifications, British Journal of Psychiatry, Aug 1990, 239-248 [11]

- ^ Hirstein, W; Ramachandran, VS (1997). "Capgras syndrome: a novel probe for understanding the neural representation of the identity and familiarity of persons" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 264 (1380): 437–444. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0062. PMC 1688258. PMID 9107057.

- ^ Brang, D McGeoch, P & Ramachandran VS (2008). "Apotemnophilia: A Neurological Disorder" (PDF). Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. 19: 1305–1306. doi:10.1097/WNR.0b013e32830abc4d. PMID 18695512.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brugger, Peter, Xenomelia: A Social Neuroscience View of Altered Bodily Self-Consciousness, Frontiers in Psychology, April 24, 2013 [12]

- ^ Gandola, M., Anatomical account of somatoparaphrenia, Cortex, June 22, 2011 [13]

- ^ McGeoch,Paul, Xenomelia: a new right parietal lobe syndrome, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, June 21, 2011 [14]

- ^ Case, L. K.; Ramachandran, V. S. (2012). "Alternating gender incongruity: A new neuropsychiatric syndrome providing insight into the dynamic plasticity of brain-sex". Medical Hypotheses. 78 (5): 626–631. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.041. PMID 22364652.

- ^ "Bigender — Boy Today, Girl Tomorrow?". Neuroskeptic. April 8, 2012.

- ^ Stix, Gary (2012-04-20). "'Alternating Gender Incongruity' Causes Rapid Shifts Of Gender, Scientist Claims". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Karen Olson (October 21, 2007). "Brain Expert Witness Testifies in Lisa Montgomery Trial". Expert Witness Blog, Juris Pro. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "United States of America v. Lisa M. Montgomery". American Lawyer. April 7, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ BBC News, One-Minute World News, Tuesday, 23 October 2007

- ^ Science Direct, 2 January 2007 Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [15]

- ^ Search on "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 31, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) for Ramachandaran (sic!) in March 2008. - ^ "Intellectuals". Prospect Magazine. 2009. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Miles, Clifford A.; Clark J. Miles (2009). "Skull of Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani, a new Cretaceous ankylosaur from the Gobi Desert" (PDF). Current Science. 96 (1): 65–70.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ naturenews, February 2, 2009

External links

- Vilayanur S. Ramachandran (official webpage)

- Take the Neuron Express for a Brief Tour of Consciousness (The Science Network interview).

- Ramachandran Illusions

- All in the Mind interview

- Reith Lectures 2003 The Emerging Mind

- TED talk by Ramachandran on brain damage and mental structures.

- Talk at Princeton about his work (2009).

- The Third Culture, including three essays regarding mirror neurons and self-awareness.

- Ramachandran's contribution to The Science Network's Beyond Belief 2007 Lectures on synaesthesia and metaphor.

- Neuroscience in the 20th Century, 24 December 1998, BBC Radio program In Our Time

- 1951 births

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- American agnostics

- American male scientists of Indian descent

- American people of Tamil descent

- Autism activists

- Autism researchers

- Cognitive neuroscientists

- Columbia University staff

- Fellows of the Society of Experimental Psychologists

- Harvard University staff

- Indian agnostics

- Indian emigrants to the United States

- Living people

- Neurotheology

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in science & engineering

- Stanford University Department of Psychology faculty

- Tamil Nadu scientists

- University of California, San Diego faculty

- University of Madras alumni

- American academics of Indian descent

- 20th-century Indian scientists