University of Pennsylvania: Difference between revisions

m ddddddd Tag: Reverted |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Private university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.}} |

|||

{ |

|||

{{About|the [[Private university|private]] [[Ivy League]] [[research university]] in Philadelphia|the public research university with campuses across Pennsylvania|Pennsylvania State University|state owned public universities in Pennsylvania|Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education}} |

|||

{{Short description|Country spanning Europe and Asia}} |

|||

{{Very long|date=August 2023|words=17,000}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2023}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Infobox university |

|||

{{Use British English|date=September 2022}} |

|||

| name = University of Pennsylvania |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023|cs1-dates=l}} |

|||

| former_names = Academy and Charitable School in the Province of Pennsylvania (1751–1755)<br />College of Philadelphia (1755–1779, 1789–1791)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html |title=Penn in the 18th Century |website=upenn.edu |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060428155156/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html |archive-date=April 28, 2006 |access-date=July 20, 2021}}</ref><br />University of the State of Pennsylvania (1779{{refn|group=note|It was not until 1785 that the name was made official as between 1779 and 1785 name was simply "University" in Philadelphia see {{cite web |url=https://secretary.upenn.edu/trustees-governance/statutes-trustees#:~:text=(g)%20On%20September%2030%2C,time%20to%20time%2C%20is%20referred |title=Statutes of the Trustees |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=September 12, 2022}}}}–1791) |

|||

{{Infobox country |

|||

| image = UPenn shield with banner.svg |

|||

| conventional_long_name = democrati republic of Purtin |

|||

| |

| image_upright = 0.7 |

||

| |

| image_alt = Arms of the University of Pennsylvania |

||

| caption = [[Coat of arms of the University of Pennsylvania|Coat of arms]] |

|||

| native_name = {{native name|ru|Российская Федерация}} |

|||

| |

| latin_name = Universitas Pennsylvaniensis |

||

| motto = {{lang|la|Leges sine moribus vanae}} ([[Latin language|Latin]]) |

|||

| image_coat = Coat of Arms of the Russian Federation.svg |

|||

| mottoeng = "Laws without morals are useless" |

|||

| national_anthem = <br />{{nowrap|{{lang|ru|Государственный гимн Российской Федерации}}}}<br />{{transliteration|ru|Gosudarstvennyy gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii}}<br />"[[State Anthem of the Russian Federation]]"{{parabr}}{{center|[[File:National Anthem of Russia (2000), instrumental, one verse.ogg]]}} |

|||

| established = {{start date and age|1740|11|14}}{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"|The university officially uses 1740 as its founding date and has since 1899. The ideas and intellectual inspiration for the academic institution stem from 1749, with a pamphlet published by [[Benjamin Franklin]] (1705/1706–1790). When Franklin's institution was established, it inhabited a schoolhouse built on November 14, 1740, for another school, which never came to practical fruition.<ref name="archives.upenn.edu">{{cite web|url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history|title=Penn History Exhibits |publisher=University Archives and Records Center |access-date=January 31, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190822113907/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history|archive-date=August 22, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> Penn archivist Mark Frazier Lloyd noted, "In 1899, UPenn's Trustees adopted a resolution that established 1740 as the founding date, but good cases may be made for 1749, when Franklin first convened the Trustees, or 1751, when the first classes were taught at the affiliated secondary school for boys, Academy of Philadelphia, or 1755, when Penn obtained its collegiate charter to add a post-secondary institution, the College of Philadelphia."<ref name="upenn.edu">{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110603231438/http://www.upenn.edu/pennnews/current/node/2231|archive-date=June 3, 2011|title=A Penn Trivial Pursuit – Penn Current|date=June 3, 2011}}</ref> Princeton's library presents another diplomatically-phrased view.<ref name="princeton.edu">{{cite web|url=http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030319132644/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/older.shtml|archive-date=March 19, 2003|title=Seeley G. Mudd Library: FAQ Princeton vs. University of Pennsylvania: Which is the Older Institution?|date=March 19, 2003}}</ref>}} |

|||

| image_map = {{Switcher|[[File:Russian Federation (orthographic projection) - All Territorial Disputes.svg|frameless]]{{parabr}}Recognized territory of Russia is shown in dark green; claimed and disputed territory is shown in light green.<!--Start of note--------------------------->{{Efn|[[Crimea]], which was [[Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation|annexed by Russia]] in 2014, remains [[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 68/262|internationally recognised]] as a part of Ukraine.<ref name="Pifer-2020">{{cite web |last=Pifer |first=Steven |url=https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/03/17/crimea-six-years-after-illegal-annexation/ |title=Crimea: Six years after illegal annexation |publisher=[[Brookings Institution]] |date=17 March 2020 |access-date=30 November 2021}}</ref> Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, which were [[Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts|annexed]]—though are only partially occupied—in 2022, also remain [[United Nations General Assembly Resolution ES-11/4|internationally recognised]] as a part of Ukraine. The southernmost [[Kuril Islands]] have been the subject of a [[Kuril Islands dispute|territorial dispute]] with Japan since their occupation by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II.<ref name="Chapple-2019" />}} |

|||

| type = [[Private university|Private]] [[research university]] |

|||

<!--End of note---------------------------->{{parabr}}|Show globe|[[File:Map of Russia-en.svg|frameless]]|Show region with labels|default=1}}<!--End of map switcher template--> |

|||

| accreditation = [[Middle States Commission on Higher Education|MSCHE]] |

|||

| map_caption = |

|||

| academic_affiliations = {{hlist |

|||

| capital = [[Moscow]] |

|||

|[[Association of American Universities|AAU]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|55|45|21|N|37|37|02|E|type:city}} |

|||

|[[Consortium on Financing Higher Education|COFHE]] |

|||

| largest_city = capital |

|||

|[[National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities|NAICU]] |

|||

| languages_type = Official and national language |

|||

|[[Universities Research Association|URA]] |

|||

| languages = [[Russian language|Russian]]<ref name="Chevalier-2006">{{cite journal |last=Chevalier |first=Joan F. |title=Russian as the National Language: An Overview of Language Planning in the Russian Federation |jstor=43669126 |journal=Russian Language Journal |pages=25–36 |volume=56 |year=2006 |publisher=American Councils for International Education ACTR / ACCELS}}</ref> |

|||

| languages2_type = {{nobold|Recognised regional languages}} |

|||

| languages2 = See [[Languages of Russia#Official languages|Languages of Russia § Official languages]] |

|||

| ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list |

|||

| 71.7% [[Russians|Russian]] |

|||

| 3.2% [[Tatars|Tatar]] |

|||

| 1.1% [[Bashkirs|Bashkir]] |

|||

| 1.1% [[Chechens|Chechen]] |

|||

| 11.3% [[Ethnic groups in Russia|other]] |

|||

| 11.6% not reported |

|||

}} |

|||

| ethnic_groups_year = 2021; including Russia and Crimea |

|||

| ethnic_groups_ref = <ref>{{cite web|title=Национальный состав населения|url=https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/Tom5_tab1_VPN-2020.xlsx|publisher=[[Federal State Statistics Service (Russia)|Federal State Statistics Service]]|access-date=30 December 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| demonym = Russian |

|||

| government_type = Federal [[semi-presidential republic]] under an [[Authoritarianism|authoritarian]] dictatorship<ref name="Krzywdzinski">{{cite book | author = Martin Krzywdzinski |year= 2020 | title = Consent and Control in the Authoritarian Workplace: Russia and China Compared | publisher = [[Oxford University Press]] | pages = 252– | isbn = 978-0-19-252902-2 | oclc = 1026492383 | url = {{GBurl|id=gz5MDwAAQBAJ|p=252}}|quote=''officially a democratic state with the rule of law, in practice an authoritarian dictatorship''}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Russia: Freedom in the World 2023 Country Report | website=Freedom House | date=9 March 2023 | url=https://freedomhouse.org/country/russia/freedom-world/2023 | access-date=17 April 2023}}</ref><ref name="cia"/><ref name="Kuzio-2016"/> <!--- Before adding [[Dominant-party system]] here, discuss in the talk page, additions before any consensus will be challenged and removed. ---> |

|||

| leader_title1 = [[President of Russia|President]] |

|||

| leader_name1 = [[Vladimir Putin]] |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[Prime Minister of Russia|Prime Minister]] |

|||

| leader_name2 = [[Mikhail Mishustin]] |

|||

| legislature = [[Federal Assembly (Russia)|Federal Assembly]] |

|||

| upper_house = [[Federation Council (Russia)|Federation Council]] |

|||

| lower_house = [[State Duma]] |

|||

| sovereignty_type = [[History of Russia|Formation]] |

|||

| established_event1 = {{nowrap|[[Kievan Rus']]}} |

|||

| established_date1 = 879 |

|||

| established_event2 = {{nowrap|[[Vladimir-Suzdal]]}} |

|||

| established_date2 = 1157 |

|||

| established_event3 = {{nowrap|[[Principality of Moscow]]}} |

|||

| established_date3 = 1282 |

|||

| established_event4 = [[Tsardom of Russia]] |

|||

| established_date4 = 16 January 1547 |

|||

| established_event5 = [[Russian Empire]] |

|||

| established_date5 = 2 November 1721 |

|||

| established_event6 = {{nowrap|[[February Revolution|Monarchy abolished]]}} |

|||

| established_date6 = 15 March 1917 |

|||

| established_event7 = {{nowrap|[[Soviet Union]]}} |

|||

| established_date7 = 30 December 1922 |

|||

| established_event8 = {{nowrap|[[Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Declaration of State<br>Sovereignty]]}} |

|||

| established_date8 = 12 June 1990 |

|||

| established_event9 = {{nowrap|[[Belovezha Accords|Russian Federation]]}} |

|||

| established_date9 = 12 December 1991 |

|||

| established_event10 = [[Constitution of Russia|Current constitution]] |

|||

| established_date10 = 12 December 1993 |

|||

| established_event11 = [[Union State|Union State formed]] |

|||

| established_date11 = 8 December 1999 |

|||

| area_km2 = 17,098,246 |

|||

| area_footnote = <ref>{{cite web |url=https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publications/pocketbook/files/world-stats-pocketbook-2016.pdf#page=182 |title=World Statistics Pocketbook 2016 edition |publisher=United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Statistics Division |access-date=24 April 2018}}</ref> (within internationally recognised borders) |

|||

| percent_water = 13<ref>{{cite web |title=The Russian federation: general characteristics |url=http://www.gks.ru/scripts/free/1c.exe?XXXX09F.2.1/010000R |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110728064121/http://www.gks.ru/scripts/free/1c.exe?XXXX09F.2.1%2F010000R |archive-date=28 July 2011 |website=Federal State Statistics Service |access-date=5 April 2008 |url-status=dead}}</ref> (including swamps) |

|||

| population_estimate = {{plainlist| |

|||

* {{IncreaseNeutral}} 147,182,123 ([[Russian Census (2021)|2021 Census]])<ref>Including 2,482,450 people living on the [[Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation|annexed]] [[Crimea|Crimean Peninsula]] {{cite web |url=https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul# |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200124160257/http://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul |url-status=dead |archive-date=24 January 2020 |script-title=ru:Том 1. Численность и размещение населения |language=ru |work=[[Federal State Statistics Service (Russia)|Russian Federal State Statistics Service]] |access-date=3 September 2022 }}</ref> |

|||

* {{nowrap|(including Crimea)<ref name="gks.ru-popul">{{cite web |url=https://rosstat.gov.ru/storage/mediabank/PrPopul2022_Site.xls |format=XLS|script-title=ru:Предварительная оценка численности постоянного населения на 1 января 2022 года и в среднем за 2021 год|trans-title=Preliminary estimated population as of 1 January 2022 and on the average for 2021 |language=ru |work=[[Federal State Statistics Service (Russia)|Russian Federal State Statistics Service]] |access-date=30 January 2022}}</ref>}} |

|||

* {{IncreaseNeutral}} 144,699,673 |

|||

* (excluding Crimea)<ref name="gks.ru-popul"/>}} |

|||

| population_estimate_year = 2022 |

|||

| population_estimate_rank = 9th |

|||

| population_density_km2 = 8.4 |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = 21.5 |

|||

| population_density_rank = 187th |

|||

| GDP_PPP = {{IncreaseNeutral}} $5.056 trillion<ref name="IMF.org-2023">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2023/October/weo-report?c=922,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2020&ey=2028&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Russia) |publisher=[[International Monetary Fund]] |website=IMF.org |date=10 October 2023 |access-date=10 October 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| GDP_PPP_year = 2023 |

|||

| GDP_PPP_rank = 6th |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{IncreaseNeutral}} $35,310<ref name="IMF.org-2023"/> |

|||

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 60th |

|||

| GDP_nominal = {{DecreaseNeutral}} $1.862 trillion<ref name="IMF.org-2023"/> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_year = 2023 |

|||

| GDP_nominal_rank = 11th |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{DecreaseNeutral}} $13,006<ref name="IMF.org-2023"/> |

|||

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 72nd |

|||

| Gini = 36.0 <!--number only--> |

|||

| Gini_year = 2020 |

|||

| Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

| Gini_ref = <ref>{{cite web |url=https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=RU |title=GINI index (World Bank estimate) – Russian Federation |publisher=World Bank |access-date=23 June 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| HDI = 0.822<!--number only--> |

|||

| HDI_year = 2021<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> |

|||

| HDI_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> |

|||

| HDI_ref = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2021-22pdf_1.pdf|title=Human Development Report 2021/2022|language=en|publisher=[[United Nations Development Programme]]|date=8 September 2022|access-date=8 September 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| HDI_rank = 52nd |

|||

| currency = [[Russian ruble|Ruble]] ([[₽]]) |

|||

| currency_code = RUB |

|||

| utc_offset = +2 to +12 |

|||

| drives_on = right |

|||

| calling_code = [[Telephone numbers in Russia|+7]] |

|||

| cctld = {{unbulleted list |[[.ru]]|[[.рф]]}} |

|||

| religion_year = 2023 |

|||

| religion_ref = <ref>{{cite web|title=Передача иконы "Троица" Русской православной церкви|url=https://fom.ru/TSennosti/14888|publisher=Фонд Общественное Мнение, ФОМ (Public Opinion Foundation)|language=ru|date=22 June 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Передача иконы "Троица" Русской православной церкви|url=https://fom.ru/posts/download/14888|publisher=Фонд Общественное Мнение, ФОМ (Public Opinion Foundation)|language=ru|date=22 June 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| religion = {{ublist|item_style=white-space;|{{Tree list}} |

|||

* 61% [[Christianity in Russia|Christianity]] |

|||

** 60% [[Russian Orthodox Church|Russian Orthodoxy]] |

|||

** 1% other [[List of Christian denominations|Christian]] |

|||

{{Tree list/end}}|24% [[Irreligion in Russia|no religion]]|9% [[Islam in Russia|Islam]]|2% [[Religion in Russia|other]] (including [[Buddhism in Russia|Buddhism]])<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.rbth.com/arts/327646-kalmykia-buddhism-russia |title=Check out Russia's Kalmykia: The only region in Europe where Buddhism rules the roost |last=Shevchenko |first=Nikolay |date=21 February 2018 |website=[[Russia Beyond]] |access-date=11 February 2023}}</ref>|4% undeclared}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| endowment = $21.0 billion (2023)<ref name = endowment>As of June 30, 2023. {{cite report |url=https://investments.upenn.edu/about-us |title=About Us Penn Office of Investments |publisher=Penn Office of Investments |date=June 30, 2023 |access-date=October 17, 2023 |archive-date=October 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231019034827/https://investments.upenn.edu/about-us |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| budget = $4.4 billion (2024)<ref>{{cite web |title=Operating Budget |url=https://budget.upenn.edu/operating-budget/ |website=Office of Budget and Management Analysis |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=2023-12-10 |archive-date=October 9, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231009003416/https://budget.upenn.edu/operating-budget/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| founder = [[Benjamin Franklin]] |

|||

| president = [[J. Larry Jameson]] (interim)<!--J. Larry Jameson has been chosen as interim president (https://www.thedp.com/article/2023/12/penn-larry-jameson-interim-president).--> |

|||

| provost = [[John L. Jackson Jr.]] |

|||

| academic_staff = 4,793 (2018)<ref name="Penn: Penn Facts">{{cite web |title=Penn: Penn Facts|url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=January 18, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191023185249/https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|archive-date=October 23, 2019|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| students = {{gaps|23,374}} (Fall 2022)<ref name="CDS">{{cite web |title=Common Data Set 2022–2023 |url=https://ira.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/UPenn-Common-Data-Set-2022-23-Jul-2023.pdf |website=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=Sep 12, 2023 |archive-date=Aug 3, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230803133606/https://ira.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/UPenn-Common-Data-Set-2022-23-Jul-2023.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| total_staff = {{gaps|39,859}} (Fall 2020; includes health system)<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|title=Facts {{pipe}} University of Pennsylvania|website=www.upenn.edu|access-date=February 1, 2020|archive-date=January 24, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200124040550/https://www.upenn.edu/about/facts|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| undergrad = 9,760 (Fall 2022)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| postgrad = {{gaps|13,614}} (Fall 2022)<ref name="CDS"/> |

|||

| city = [[Philadelphia]] |

|||

| state = [[Pennsylvania]] |

|||

| country = United States |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|39.95|-75.19|region:US-PA_type:edu|display=title,inline}} |

|||

| campus = Large city |

|||

| campus_size = {{convert|1085|acre|km2}} (total);<br /> {{convert|299|acre|km2}}, [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] campus; <br />{{convert|694|acre|km2}}, [[New Bolton Center]]; <br />{{convert|92|acre|km2}}, [[Morris Arboretum]] |

|||

| free_label2 = Newspaper |

|||

| free2 = ''[[The Daily Pennsylvanian]]'' |

|||

| sporting_affiliations = {{hlist|[[NCAA Division I FCS]] – [[Ivy League]]|[[Philadelphia Big 5]]|[[City 6]]|[[Intercollegiate Rowing Association|IRA]]|[[Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges|EARC]]|[[Eastern Association of Women's Rowing Colleges|EAWRC]]}} |

|||

| colors = {{college color list|team=Penn Quakers}} <!-- same as athletics, inserted automatically --> |

|||

| nickname = [[Penn Quakers|Quakers]] |

|||

| mascot = The Quaker |

|||

| website = {{Official URL}} |

|||

| logo = University of Pennsylvania wordmark.svg |

|||

| logo_upright = .7 |

|||

| free_label = Other campuses |

|||

| free = [[San Francisco]] |

|||

<!--| pushpin_map = USA -->}} |

|||

'''Russia''' ({{Lang-ru|Россия|Rossiya}}, {{IPA-ru|rɐˈsʲijə|}}), or the '''Russian Federation''',<!-- Both names are equally official - see: [[Talk:Russia/Archive 12#Equality of the names]]. -->{{efn|{{lang-rus|Российская Федерация|r=Rossiyskaya Federatsiya|p=rɐˈsʲijskəjə fʲɪdʲɪˈratsɨjə|links=yes}}}} is a country spanning [[Eastern Europe]] and [[North Asia|Northern Asia]]. It is the [[list of countries and dependencies by area|largest country in the world by area]] extending across [[Time in Russia|eleven time zones]]. It shares [[Borders of Russia|land boundaries with fourteen countries]].{{efn|Russia shares land borders with fourteen [[sovereign state]]s:<ref>{{Citation |title=Russia |date=2022 |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/russia/#geography |work=The World Factbook |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |language=en |access-date=14 October 2022}}</ref> [[Norway]] and [[Finland]] to the northwest; [[Estonia]], [[Latvia]], [[Belarus]] and [[Ukraine]] to the west, as well as [[Lithuania]] and [[Poland]] (with [[Kaliningrad Oblast]]); [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]] and [[Azerbaijan]] to the southwest; [[Kazakhstan]] and [[Mongolia]] to the south; China and [[North Korea]] to the southeast—as well as sharing [[Maritime boundary|maritime boundaries]] with Japan and the United States. Russia also shares borders with the two [[partially recognized states|partially recognised]] breakaway states of [[South Ossetia]] and [[Abkhazia]] that it occupies in Georgia.}} It is the [[List of countries and dependencies by population|world's ninth-most populous country]] and [[List of European countries by population|Europe's most populous country]]. The country's capital and [[List of cities and towns in Russia by population|largest city]] is [[Moscow]]. [[Saint Petersburg]] is Russia's second-largest city and "cultural capital". Other major urban areas in the country include [[Novosibirsk]], [[Yekaterinburg]], [[Nizhny Novgorod]], [[Chelyabinsk]], [[Krasnoyarsk]], [[Kazan]], [[Krasnodar]] and [[Rostov-on-Don]]. |

|||

<!-- Join the discussion on the article's talk page regarding the lead. --> |

|||

<!-- Please do not make large changes to the lead without discussing them on the article's talk page. --> |

|||

<!-- Please keep the lead encyclopedic and factual. Please do not selectively cherry pick rankings or attempt to turn this into brochure ware. --> |

|||

<!-- There are already too many images on this page. Please do not add any further without Talk page discussion. And other than the initial Ben Franklin image, there should be no images in the left margin. --> |

|||

The '''University of Pennsylvania''' ('''Penn'''<ref>[https://branding.web-resources.upenn.edu The registered trademark as the primary substitute for using the University's full name and part of official brand] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220418015150/https://branding.web-resources.upenn.edu/ |date=April 18, 2022 }}, accessed June 9, 2021</ref> or '''UPenn'''<ref>[https://thepenngazette.com/penn-v-upenn Permissible in situations where it may help to distinguish Penn from other universities within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and used as part of email address] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211104102013/https://thepenngazette.com/penn-v-upenn |date=November 4, 2021 }}, accessed June 9, 2021</ref>) is a [[Private university|private]] [[Ivy League]] [[research university]] in [[Philadelphia]], Pennsylvania. It is one of nine [[colonial colleges]] and was chartered prior to the [[United States Declaration of Independence|U.S. Declaration of Independence]] when [[Benjamin Franklin]], the university's founder and first president, advocated for an educational institution that trained leaders in academia, commerce, and [[public service]]. Penn identifies as the [[List of oldest universities in continuous operation|fourth oldest institution of higher education in the United States]], though this representation is challenged by other universities, as Franklin first convened the board of trustees in 1749, arguably making it the fifth oldest institution of higher education in the U.S.{{refn|group=note|name="founding_note"}} |

|||

The [[East Slavs]] emerged as a recognised group in Europe between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE. The first East Slavic state, [[Kievan Rus']], arose in the 9th century, and in 988, it adopted [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox Christianity]] from the [[Byzantine Empire]]. Rus' ultimately disintegrated, with the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow]] growing to become the [[Tsardom of Russia]]. By the early 18th century, Russia had vastly expanded through conquest, annexation, and the efforts of [[List of Russian explorers|Russian explorers]], developing into the [[Russian Empire]], which remains the [[List of largest empires|third-largest empire in history]]. However, with the [[Russian Revolution]] in 1917, Russia's monarchic rule [[Dissolution of the Russian Empire|was abolished]] and eventually replaced by the [[Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic|Russian SFSR]]—the world's first constitutionally [[socialist state]]. Following the [[Russian Civil War]], the Russian SFSR established the [[Soviet Union]] with three other [[Republics of the Soviet Union|Soviet republics]], within which it was the largest and principal constituent. At the [[Excess mortality in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin|expense of millions of lives]], the Soviet Union underwent [[Industrialization in the Soviet Union|rapid industrialisation in the 1930s]] and later played a decisive role for the [[Allies in World War II]] by leading large-scale efforts on the [[Eastern Front (World War II)|Eastern Front]]. With the onset of the [[Cold War]], it competed with the [[United States]] for global ideological influence. The Soviet era of the 20th century saw some of the [[Timeline of Russian innovation|most significant Russian technological achievements]], including the [[Sputnik 1|first human-made satellite]] and the [[Vostok 1|first human expedition into outer space]]. |

|||

The university has four undergraduate schools and 12 graduate and professional schools. Schools enrolling undergraduates include the [[University of Pennsylvania College of Arts & Sciences|College of Arts and Sciences]], the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science|School of Engineering and Applied Science]], the [[Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania|Wharton School]], and the [[University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing|School of Nursing]]. Among its highly ranked graduate schools are its [[University of Pennsylvania Law School|law school]], whose first professor [[James Wilson (Founding Father)|James Wilson]] participated in writing the first draft of the [[Constitution of the United States|U.S. Constitution]], its [[Perelman School of Medicine|medical school]], which was the first medical school established in [[North America]], and Wharton, the nation's first collegiate business school. Penn's [[financial endowment|endowment]] is $20.7 billion, making it the [[List of colleges and universities in the United States by endowment|sixth-wealthiest private academic institution in the nation]] as of 2022. In 2021, it ranked 4th among American universities in [[List of countries by research and development spending|research expenditures]] according to the [[National Science Foundation]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Universities Report Largest Growth in Federally Funded R&D Expenditures since FY 2011 {{!}} NSF - National Science Foundation |url=https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf23303 |access-date=2023-12-28 |website=ncses.nsf.gov}}</ref> |

|||

In 1991, the Russian SFSR emerged from the [[dissolution of the Soviet Union]] as the independent Russian Federation. A new [[Constitution of Russia|constitution]] was adopted, which established a [[federation|federal]] [[semi-presidential republic|semi-presidential system]]. Since the turn of the century, Russia's political system has been dominated by [[Vladimir Putin]], under whom the country has experienced [[democratic backsliding]] and a shift towards [[authoritarianism]]. [[Military history of the Russian Federation|Russia has been militarily involved]] in a number of [[List_of_wars_involving_Russia#Russian_Federation_(1991–present)|conflicts in former Soviet states and other countries]], including its [[Russo-Georgian War|war with Georgia]] in 2008 and [[annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation|annexation of Crimea]] in 2014 from neighbouring [[Ukraine]], followed by the further annexation of [[Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts|four other regions]] in 2022 during [[2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine|an ongoing invasion]]. |

|||

The University of Pennsylvania's main campus is located in the [[University City, Philadelphia|University City]] neighborhood of [[West Philadelphia]], and is centered around [[College Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|College Hall]]. Notable campus landmarks include [[Houston Hall (University of Pennsylvania)|Houston Hall]], the first modern [[Student activity center|student union]], and [[Franklin Field]], the nation's first dual-level [[college football]] stadium and the nation's longest-standing [[NCAA Division I]] college football stadium in continuous operation.<ref>[https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2022-07-26/these-are-10-oldest-stadiums-division-i-college-football "These are the 10 oldest stadiums in Division I college football"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230312232120/https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2022-07-26/these-are-10-oldest-stadiums-division-i-college-football |date=March 12, 2023 }}, NCAA, July 26, 2022</ref> The university's athletics program, the [[Penn Quakers]], fields varsity teams in 33 sports as a member of NCAA Division I's Ivy League conference. |

|||

Internationally, Russia [[International rankings of Russia|ranks among the lowest]] in measurements of [[Democracy in Russia|democracy]], [[Human rights in Russia|human rights]] and [[Media freedom in Russia|freedom of the press]]; the country also has [[Corruption in Russia|high levels of perceived corruption]]. The [[Economy of Russia|Russian economy]] ranks [[List of countries by GDP (nominal)|11th by nominal]] GDP, relying heavily on its abundant natural resources. Its mineral and energy sources are the world's largest, and its figures for [[List of countries by oil production|oil production]] and [[List of countries by natural gas production|natural gas production]] rank highly globally. The Russian GDP ranks 68th by per capita; Russia possesses the [[Russia and weapons of mass destruction|largest stockpile of nuclear weapons]] and has the [[List of countries by military expenditures|third-highest military expenditure]]. The country is a [[Permanent members of the United Nations Security Council|permanent member of the United Nations Security Council]]; a member state of the [[G20]], [[Shanghai Cooperation Organisation|SCO]], [[BRICS]], [[Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation|APEC]], [[Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe|OSCE]], and [[World Trade Organization|WTO]]; and the leading member state of post-Soviet organisations such as [[Commonwealth of Independent States|CIS]], [[Collective Security Treaty Organization|CSTO]], and [[Eurasian Economic Union|EAEU/EEU]]. Russia is home to [[List of World Heritage Sites in Russia|30 UNESCO World Heritage Sites]]. |

|||

Since its founding, Penn alumni, trustees, and faculty have included 8 signers of the [[U.S. Declaration of Independence]], 7 signers of the [[United States Constitution|Constitution]], 3 [[List of presidents of the United States|Presidents of the United States]], 3 [[Supreme Court of the United States|U.S. Supreme Court justices]], 32 [[United States Senate|U.S. senators]], 163 members of the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]], 19 [[Cabinet of the United States|U.S. Cabinet Secretaries]], 46 [[Governor (United States)|governors]], 28 [[State supreme court|State Supreme Court]] justices, and 9 foreign [[Head of state|heads of state]]. Alumni and faculty include [[List of Nobel laureates by university affiliation|39 Nobel laureates]],<ref name=":1">Nobel Prize Awarded to Covid Vaccine Pioneers https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/02/health/nobel-prize-medicine.html?smid=nytcore-android-share {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231004182045/https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/02/health/nobel-prize-medicine.html?smid=nytcore-android-share |date=October 4, 2023 }} accessed October 2, 2023</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Congratulations to Claudia Goldin, who was awarded the 2023 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences today |url=https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/news/congratulations-claudia-goldin-who-was-awarded-2023-nobel-memorial-prize-economic-sciences |date=October 9, 2023 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=October 14, 2023 |archive-date=October 14, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231014082508/https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/news/congratulations-claudia-goldin-who-was-awarded-2023-nobel-memorial-prize-economic-sciences |url-status=live }}</ref> 4 [[Turing Award]] winners,<ref>https://www.turing.ac.uk/search/node?keys=University%20of%20Pennsylvania%20&page=1%2C0 access date September 10, 2023</ref> and a [[Fields Medalist]].<ref name="Charles W Bachman">{{cite web |title=Charles W Bachman |url=https://amturing.acm.org/award_winners/bachman_9385610.cfm |access-date=June 13, 2023 |website=A.M Turing Award |language=en |archive-date=October 2, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201002063303/https://amturing.acm.org/award_winners/bachman_9385610.cfm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Who's Who in New Zealand, 1991 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6x8OAQAAMAAJ |access-date=July 29, 2015 |last1=Lambert |first1=Max |year=1991 |edition=12th |publisher=Octopus |location=Auckland |page=331 |isbn=9780790001302 |archive-date=December 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231219163607/https://books.google.com/books?id=6x8OAQAAMAAJ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk">{{Cite web|title=Vaughan Jones - University of St. Andrews|url=https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Jones_Vaughan/|access-date=September 9, 2020|archive-date=August 5, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200805200102/https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Jones_Vaughan/|url-status=live}}</ref> Penn has graduated 32 [[Rhodes Scholarship|Rhodes Scholars]]<ref>{{cite web |title=Colleges and Universities with U.S. Rhodes Scholarship Winners {{!}} The Rhodes Scholarships |url=https://www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk/office-of-the-american-secretary/us-winners/colleges-and-universities-of-all-us-rhodes-scholars-over-time/ |access-date=February 5, 2023 |website=www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk |language=en |archive-date=August 7, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200807160702/https://www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk/office-of-the-american-secretary/us-winners/colleges-and-universities-of-all-us-rhodes-scholars-over-time/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and 21 [[Marshall Scholarship|Marshall Scholars]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Two Penn seniors named 2022 Marshall Scholars {{!}} Penn CURF |url=https://curf.upenn.edu/content/marshall-2021-0#:~:text=Penn%20has%20had%2021%20Marshall,in%20the%20past%20four%20years. |access-date=February 5, 2023 |website=curf.upenn.edu |archive-date=April 27, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220427052017/https://curf.upenn.edu/content/marshall-2021-0#:~:text=Penn%20has%20had%2021%20Marshall,in%20the%20past%20four%20years. |url-status=live }}</ref> As of 2022, Penn has the largest number of undergraduate alumni who are billionaires of all colleges and universities (17, counting only Penn's four undergraduate schools).<ref>https://poetsandquantsforundergrads.com/news/this-school-has-the-most-billionaire-alumni/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230903061806/https://poetsandquantsforundergrads.com/news/this-school-has-the-most-billionaire-alumni/ |date=September 3, 2023 }} and https://www.forbes.com/sites/conormurray/2022/10/02/billionaire-alma-maters-the-11-most-popular-colleges-among-americas-richest/?sh=9d31b4b4a6cd {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230903060900/https://www.forbes.com/sites/conormurray/2022/10/02/billionaire-alma-maters-the-11-most-popular-colleges-among-americas-richest/?sh=9d31b4b4a6cd |date=September 3, 2023 }} accessed September 11, 2023</ref> Penn alumni have won (a) 53 [[Tony Awards]], (b) 17 [[Grammy Awards]], (c) 25 [[Emmy Awards]], and (d) 13 [[Academy Awards]]. At least 43 different Penn alumni have earned 81 Olympic medals (26 gold),<ref name="pennolympics">{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/athletics/olympics/athletes |title=Penn in the Olympics |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=August 12, 2021 |archive-date=August 21, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210821044816/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/athletics/olympics/athletes |url-status=live }}</ref>{{refn|group=note|See [[list of University of Pennsylvania people]] athletics section for list of Penn Olympic medal winners, replete with hyperlinks.}} 2 Penn alumni have been [[NASA]] [[astronaut]]s,<ref name="garrettreisman.com">https://www.garrettreisman.com/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231013155905/https://www.garrettreisman.com/ |date=October 13, 2023 }} and https://news.seas.upenn.edu/pieces-of-penn-history-return-from-space/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231017192925/https://news.seas.upenn.edu/pieces-of-penn-history-return-from-space/ |date=October 17, 2023 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Biographical Data|url=https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/bluford_guion.pdf|url-status=live|access-date=October 14, 2023|archive-date=February 12, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210212170249/https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/bluford_guion.pdf}}</ref> and 5 Penn alumni have been awarded the [[Medal of Honor]].<ref name="Congressional Medals of Honor, Reci">{{cite web |last1=Ahern |first1=Joseph-James |last2=Hawley |first2=Scott W. |title=Congressional Medals of Honor, Recipients from the Civil War • University Archives and Records Center |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/medal-of-honor |publisher=Penn University Archives and Records Center |date=January 2011 |access-date=October 9, 2020 |archive-date=January 23, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190123201154/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/notables/awards/medal-of-honor |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="na" /> |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

{{Main|Names of Rus', Russia and Ruthenia}}According to the ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'', the English name ''Russia'' first appeared in the 14th century, borrowed from {{Lang-la-x-medieval|Russia}}, used in the 11th century and frequently in 12th-century British sources, in turn derived from {{Lang-la-x-medieval|Russi|lit=the Russians|label=none}} and the suffix {{Lang-la-x-medieval|[[wikt:-ia#Latin|-ia]]|label=none}}.<ref>{{Cite web |date=September 2023 |title=Russia (n.), Etymology |url=https://www.oed.com/dictionary/russia_n?tab=etymology |website=Oxford English Dictionary |doi=10.1093/OED/2223074989}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Kuchkin|first=V. A.|title=|publisher=Institute of General History of the Russian Academy of Sciences; Ladomir|year=2014|editor-last=Melnikova|editor-first=E. A.|location=Moscow|pages=700–701|language=ru|script-title=ru:Древняя Русь в средневековом мире|trans-title=Old Rus' in the medieval world|script-chapter=ru:Русская земля|trans-chapter=Russian land|editor-last2=Petrukhina|editor-first2=V. Ya.}}</ref> In modern historiography, this state is usually denoted as ''[[Kievan Rus']]'' after its capital city.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kort |first1=Michael |title=A Brief History of Russia |date=2008 |publisher=Checkmark Books |isbn=978-0816071135 |location=New York |page=6}}</ref> Another Medieval Latin name for Rus' was [[Ruthenia]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Nazarenko |first=Aleksandr Vasilevich|author-link=Aleksandr Nazarenko|script-title=ru:Древняя Русь на международных путях: междисциплинарные очерки культурных, торговых, политических связей IX–XII веков |year=2001 |publisher=Languages of the Rus' culture |isbn=978-5-7859-0085-1 |pages=40, 42–45, 49–50 |chapter=1. Имя "Русь" в древнейшей западноевропейской языковой традиции (XI–XII века)|trans-title=Old Rus' on international routes: interdisciplinary essays on cultural, trade, and political ties in the 9th–12th centuries |language=ru|trans-chapter=The name Rus' in the old tradition of Western European language (XI-XII centuries)|chapter-url=http://dgve.csu.ru/download/Nazarenko_2001_01.djvu |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110814143443/http://dgve.csu.ru/download/Nazarenko_2001_01.djvu |archive-date=14 August 2011}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

In Russian, the current name of the country, {{Lang|ru|Россия|italic=no}} ({{Lang|ru-latn|Rossiya}}), comes from the [[Byzantine Greek]] name for Rus', {{Lang|grc|Ρωσία|italic=no}} ({{Lang|grc-latn|Rosía}}).<ref>{{cite book |title=The Russians: The People of Europe |last=Milner-Gulland |first=R. R. |year=1997 |publisher=Blackwell Publishing |isbn=978-0-631-21849-4 |pages=1–4}}</ref> A new form of the name ''Rus{{'}}'', {{lang|ru|Росия|italic=no}} ({{lang|ru-latn|Rosiya}}), was borrowed from the Greek term and first attested in 1387.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Obolensky |first1=Dimitri |url=https://archive.org/details/byzantiumslavs0000obol/page/16/mode/2up |title=Byzantium and the Slavs |date=1994 |publisher=St. Vladimir's Seminary Press |isbn=9780881410082 |location=Crestwood, NY |pages=17}}</ref>{{Failed verification|date=January 2024}} The name {{Transliteration|ru|Rossiia}} appeared in Russian sources in the late 15th century, but until the end of the 17th century the country was more often referred to by its inhabitants as Rus{{'}}, the Russian land ({{Transliteration|ru|Russkaia zemlia}}), or the Muscovite state ({{Transliteration|ru|Moskovskoe gosudarstvo}}), among other variations.<ref name=":0">{{cite book |last1=Langer |first1=Lawrence N. |title=Historical Dictionary of Medieval Russia |date=2021 |location=Lanham |isbn=978-1538119426 |page=182 |edition=2nd |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield}}</ref><ref name="Hellberg-Hirn-1998">{{cite book |last1=Hellberg-Hirn |first1=Elena |title=Soil and Soul: The Symbolic World of Russianness |date=1998 |publisher=Ashgate |location=Aldershot [Hants, England] |isbn=1855218712 |pages=54}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book |last=Plokhy |first=Serhii |title=The origins of the Slavic nations: premodern identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus |date=2010 |publisher=Cambridge Univ. Press |isbn=978-0-521-15511-3 |edition=1st |location=Cambridge |pages=213–14, 285}}</ref> In 1721, Peter the Great changed the name of the state from [[Tsardom of Russia|Tsardom of Rus]] ({{Transliteration|ru|Russkoe tsarstvo}}) to [[Russian Empire]] ({{Transliteration|ru|Rossiiskaia imperiia}}).<ref name=":0" /><ref name=":1" /> |

|||

===Origins of the college=== |

|||

{{Further|Academy and College of Philadelphia}} |

|||

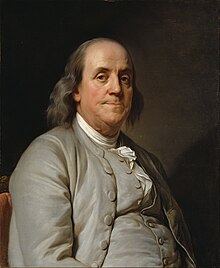

[[File:Joseph Siffrein Duplessis - Benjamin Franklin - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|[[Benjamin Franklin]], founder of the University of Pennsylvania, was the primary founder, benefactor, and a president of the board of trustees for the [[Academy and College of Philadelphia]], which merged with the [[University of the State of Pennsylvania]] to form the University of Pennsylvania in 1791.]] |

|||

In 1740, a group of [[Philadelphia]]ns organized to erect a great preaching hall for [[George Whitefield]], a traveling [[evangelism|evangelist]] who toured the American colonies delivering open-air sermons.<ref>see second footnote 9 in Extracts from the Benjamin Franklin published Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230826064004/https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 |date=August 26, 2023 }} "Note: The annotations to this document, and any other modern editorial content, are copyright the American Philosophical Society and Yale University. All rights reserved."</ref> The building was designed and constructed by [[Edmund Woolley]] and was the largest building in Philadelphia at the time, drawing thousands of people the first time in which it was preached.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory">{{cite book|title=A History of the University of Pennsylvania from Its Foundation to A. D. 1770|publisher=George W. Jacobs & Co.|author=Montgomery, Thomas Harrison|year=1900|location=Philadelphia|lccn=00003240|title-link=:File:History of the University of Pennsylvania - Montgomery (1900).djvu}}</ref>{{rp|26}} The preaching hall was initially intended to also serve as a [[charity school]], but a lack of funds forced plans for the chapel and school to be suspended. |

|||

According to Franklin's autobiography, it was in 1743 when he first had the idea to establish an academy, "thinking the Rev. [[Richard Peters (priest)|Richard Peters]] a fit person to superintend such an institution". Peters declined a casual inquiry from Franklin, but was one of Penn's founding trustees from 1749 to 1776, president of the board of trustees from 1756 to 1764, and treasurer of the board of trustees from 1769 to 1770.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/richard-peters/ |title=Richard Peters |publisher=Archives.upenn.edu |date=January 24, 2022 |access-date=May 31, 2022 |archive-date=June 30, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220630064242/https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/richard-peters/ |url-status=live }}</ref>). |

|||

There are several words in Russian which translate to "Russians" in English{{snd}}{{Lang-ru|русские|translit=russkie|label=none}}, which refers to ethnic [[Russians]], {{Lang-ru|российские|translit=rossiiskie|label=none}}, [[Russian citizenship law|Russian citizens]] regardless of ethnicity, and the recently fashionable {{Lang-ru|россияне|translit=rossiiane|label=none}}, Russian citizens of the Russian state.<ref name="Hellberg-Hirn-1998" /><ref>{{cite journal |last=Merridale |first=Catherine |title=Redesigning History in Contemporary Russia |journal=[[Journal of Contemporary History]] |year=2003 |volume=38 |number=1 |pages=13–28 |doi=10.1177/0022009403038001961 |jstor=3180694 |s2cid=143597960}}</ref> |

|||

Six years later, Franklin again contacted Peters and others.<ref name="MontgomeryHistory"/>{{rp|30}} In the fall of 1749, Franklin circulated a pamphlet, "[[commons:File:Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania (UC) - Benjamin Franklin (1931 1749).djvu|Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania]]", his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia",<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|title=A Brief History of the University, University of Pennsylvania Archives|first=Steven Morgan|last=Friedman|publisher=Archives.upenn.edu|access-date=December 9, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100102143449/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/genlhistory/brief.html|archive-date=January 2, 2010|url-status=dead}}</ref> which argued for establishing an institution that would provide higher education to its citizens. |

|||

According to the [[Primary Chronicle]], the word Rus' is derived from the [[Rus' people]], who were a [[Swedes|Swedish]] tribe, and where the three original members of the [[Rurikid]] dynasty came from.<ref>{{cite book |last=Duczko |first=Wladyslaw |title=Viking Rus |publisher=[[Brill Publishers]] |year=2004 |isbn=978-90-04-13874-2 |pages=10–11}}</ref> The [[Finnish language|Finnish]] word for Swedes, ''ruotsi'', has the same origin.<ref>''The Origin of Rus'''. Omeljan Pritsak. The Russian Review. Vol. 36, No. 3 (Jul. 1977), pp. 249-273 (25 pages). https://doi.org/10.2307/128848; https://www.jstor.org/stable/128848</ref> |

|||

Later archeological studies mostly confirmed this theory.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Swedish Vikings: Who Were the Rus? |url=https://cjadrien.com/swedish-vikings-rus/}}</ref>{{Better source needed|reason=The current source is insufficiently reliable ([[WP:NOTRS]]).|date=January 2024}} |

|||

The 1749 proposal was seen as innovative at the time, and Franklin organized 24 trustees to help guide the institution he envisioned. The group acquired a dormant building after its owners asked Franklin's group to assume their debts and, accordingly, their inactive trusts. On February 1, 1750, a new board of trustees took over the building and trusts of the old board. On August 13, 1751, the Academy of Philadelphia, using the great hall at 4th and [[Arch Street (Philadelphia)|Arch Streets]], was established and began taking in its first secondary students. A [[charity school]] also was chartered on July 13, 1753,<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|12}} by the intentions of the original donors, although it lasted only a few years. On June 16, 1755, the [[Academy and College of Philadelphia|College of Philadelphia]] was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction.<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|13}} All three schools shared the same board of trustees and were considered part of the same institution.<ref name=autogenerated1/> The first commencement exercises were held on May 17, 1757.<ref name="WoodHistory"/>{{rp|14}} |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{Main|History of Russia}} |

|||

The University of Pennsylvania considers itself the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, though this is contested by [[Princeton University|Princeton]] and [[Columbia University|Columbia]] Universities.{{refn|group=note| Penn is the fourth-oldest using the founding dates claimed by each institution. The College of Philadelphia, which became Penn, [[Princeton University|College of New Jersey]], which became Princeton University, and [[Columbia University|King's College]], which later became Columbia College and ultimately Columbia University, all originated within a few years of each other. After initially designating 1750 as its founding date, Penn later considered 1749 to be its founding date for more than a century with Penn alumni observing a centennial celebration in 1849. In 1895, several elite universities in the United States convened in New York City as the Intercollegiate Commission at the invitation of [[John James McCook (lawyer)|John J. McCook]], a [[Union Army]] officer during the [[American Civil War]] and member of Princeton's board of trustees who chaired its Committee on Academic Dress. The primary purpose of the conference was to standardize American academic regalia, which was accomplished through the adoption of the [[Academic regalia in the United States|Intercollegiate Code on Academic Costume]]. This formalized protocol included a provision that established [[academic procession]]s and placed visiting dignitaries and other officials in the order of their institution's founding dates. The following year, Penn's ''The Alumni Register'' magazine, published by the General Alumni Society, began a campaign to retroactively revise the university's founding date to 1740, to become older than Princeton, which had been chartered in 1746. Three years later in 1899, the university's board of trustees acceded to this alumni initiative and officially changed its founding date from 1749 to 1740, altering its rank in academic processions and offering the informal bragging rights associated with the age-based hierarchy in academia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0902/thomas.html|title=Gazette: Building Penn's Brand (Sept/Oct 2002)|website=www.upenn.edu|access-date=January 25, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051120020503/http://www.upenn.edu/gazette/0902/thomas.html|archive-date=November 20, 2005|url-status=live}}</ref> Princeton implicitly challenges this rationale,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.princeton.edu/meet-princeton/history|title=History|website=Princeton University|access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190805225330/https://www.princeton.edu/meet-princeton/history|archive-date=August 5, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.princeton.edu/main/about/history/american-revolution/ |title=Princeton University in the American Revolution |publisher=Princeton University |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160403053852/http://www.princeton.edu/main/about/history/american-revolution/ |archive-date=April 3, 2016}}</ref> Further complicating the comparison, a [[University of Edinburgh]]-educated [[Presbyterianism|Presbyterian]] minister from Scotland, [[William Tennent]], and his son [[Gilbert Tennent]] operated a [[Log College]] in [[Bucks County, Pennsylvania]], from 1726 until 1746; some have suggested a connection between it and Princeton because five members of Princeton's first Board of Trustees were affiliated with it, including Gilbert Tennent, William Tennent, Jr., and Samuel Finley, the latter of whom later became president of Princeton. All 12 members of Princeton's first Board of Trustees were leaders from the [[The Old Side-New Side Controversy|New Side]] or [[Old and New Light|New Light]] wing of the [[Presbyterian Church]] in the [[New Jersey]], [[New York (state)|New York]], and [[Pennsylvania]] areas.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/founders.shtml |title=Who founded Princeton University and when? |publisher=Princeton University |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131105013448/http://www.princeton.edu/mudd/news/faq/topics/founders.shtml |archive-date=November 5, 2013}}</ref> This antecedent relationship, when considered a formal lineage with institutional continuity, would justify placing Princeton's founding date back to 1726, which would make it earlier than Penn's 1740 founding. However, Princeton has not asserted this, and a Princeton historian says that "the facts do not warrant" such an interpretation.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://etcweb1.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/log_college.html|title=Log College |publisher=Princeton University |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051117052303/http://etcweb1.princeton.edu/CampusWWW/Companion/log_college.html|archive-date=November 17, 2005|url-status=dead|access-date=January 30, 2006}}</ref> Columbia also implicitly challenges Penn's use of either 1750, 1749 or 1740 as its founding date since it claims to be the fifth-oldest institution of higher learning in the United States after [[Harvard University|Harvard]], [[William & Mary College|William & Mary]], [[Yale University|Yale]], and [[Princeton University|Princeton]] based on its charter date of 1754 and Penn's charter date of 1755.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.columbia.edu/content/history|title=History – Columbia University in the City of New York|website=www.columbia.edu|access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517175032/https://www.columbia.edu/content/history|archive-date=May 17, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> Academic histories of American higher education typically list Penn variously as either the nation's fifth or sixth-oldest institution of higher learning in the nation after Princeton and immediately before or after Columbia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ConspectusH/id/345|title=COH-03-057_Page-45|website=dmr.bsu.edu |access-date=May 16, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200122150848/https://dmr.bsu.edu/digital/collection/ConspectusH/id/345|archive-date=January 22, 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/9120/article_RI234246.pdf?sequence=5 |title=American Colonial Colleges |website=scholarship.rice.edu |format=PDF |access-date=May 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116181127/http://scholarship.rice.edu/bitstream/handle/1911/9120/article_RI234246.pdf?sequence=5 |archive-date=January 16, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3878/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00140.pdf?sequence=1 |title=The History of American Colleges and Their Libraries in The Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries |last=Zubatsky |first=David |date=2007 |website=ideals.illinois.edu |format=PDF |access-date=May 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141028044908/https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/3878/gslisoccasionalpv00000i00140.pdf?sequence=1 |archive-date=October 28, 2014 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

=== Early history === |

|||

{{further|Ancient Greek colonies||Early Slavs|Huns|Turkic expansion|Prehistory of Siberia}} |

|||

{{See also|Proto-Indo-Europeans|Proto-Uralic homeland}} |

|||

The first human settlement on Russia dates back to the [[Oldowan]] period in the early [[Lower Paleolithic]]. About 2 million years ago, representatives of ''[[Homo erectus]]'' migrated to the [[Taman Peninsula]] in southern Russia.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Shchelinsky |first1=V.E. |last2=Gurova |first2=M. |last3=Tesakov |first3=A.S. |last4=Titov |first4=V.V. |last5=Frolov |first5=P.D. |last6=Simakova |first6=A.N. |title=The Early Pleistocene site of Kermek in western Ciscaucasia (southern Russia): Stratigraphy, biotic record and lithic industry (preliminary results) |journal=[[Quaternary International]] |volume=393 |pages=51–69 |date=30 January 2016 |doi=10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.032|bibcode=2016QuInt.393...51S }}</ref> [[Flint]] tools, some 1.5 million years old, have been discovered in the [[North Caucasus]].<ref>{{cite web |last1= Chepalyga |first1= A.L. |last2= Amirkhanov |first2= Kh.A. |last3= Trubikhin |first3= V.M. |last4= Sadchikova |first4= T.A. |last5= Pirogov |first5= A.N. |last6= Taimazov |first6= A.I. |year= 2011 |title= Geoarchaeology of the earliest paleolithic sites (Oldowan) in the North Caucasus and the East Europe |url= http://paleogeo.org/article3.html |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20130520090413/http://paleogeo.org/article3.html |archive-date= 20 May 2013 |access-date= 18 December 2013 }}</ref> [[Radiocarbon dated]] specimens from [[Denisova Cave]] in the [[Altai Mountains]] estimate the oldest [[Denisovan]] specimen lived 195–122,700 years ago.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Douka |first1=K. |title=Age estimates for hominin fossils and the onset of the Upper Palaeolithic at Denisova Cave |journal=Nature |year=2019 |volume=565 |issue=7741 |pages=640–644 |doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0870-z |pmid=30700871 |url=https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1559&context=smhpapers1 |bibcode=2019Natur.565..640D |s2cid=59525455}}</ref> Fossils of ''[[Denny (hybrid hominin)|Denny]]'', an [[archaic human]] hybrid that was half [[Neanderthal]] and half Denisovan, and lived some 90,000 years ago, was also found within the latter cave.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Warren |first=Matthew |title=Mum's a Neanderthal, Dad's a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid |date=22 August 2018 |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=560 |issue=7719 |pages=417–418 |doi=10.1038/d41586-018-06004-0 |pmid=30135540 |bibcode= 2018Natur.560..417W |doi-access=free }}</ref> Russia was home to some of the last surviving Neanderthals, from about 45,000 years ago, found in [[Mezmaiskaya cave]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1= Igor V. Ovchinnikov |last2= Anders Götherström |last3= Galina P. Romanova |last4= Vitaliy M. Kharitonov |last5= Kerstin Lidén |last6= William Goodwin |date= 30 March 2000 |title= Molecular analysis of Neanderthal DNA from the northern Caucasus |journal= [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume= 404 |issue= 6777 |pages= 490–493 |bibcode= 2000Natur.404..490O |doi= 10.1038/35006625 |pmid= 10761915 |s2cid= 3101375}}</ref> |

|||

Even Penn's account of its early history agrees that the Academy of Philadelphia did not add the College of Philadelphia until 1755, but university officials continue to make it their practice to assert their fourth-oldest place in academic processions. Other American universities that began in the [[Colonial history of the United States|colonial era]], such as [[St. John's College (Annapolis/Santa Fe)|St. John's College]], which was founded as King William's School in 1696, and the [[University of Delaware]], which was founded as the Free Academy in 1743, choose to utilize the dates they became institutions of higher learning. Penn history professor Edgar Potts Cheyney was a member of the Penn class of 1883 who played a leading role in the 1896–1899 alumni campaign to change the university's formal founding date. According to Cheyney's later recollection, the university considered its founding date to be 1749 for almost a century. However, it was changed with good reason, and primarily due to a publication about the university issued by the [[United States Secretary of Education|U.S. Commissioner of Education]] written by Francis Newton Thorpe, a fellow alumnus, and colleague in the Penn history department. The year 1740 is the date of the establishment of the university's first educational trust. Cheyney states that "it might be considered a lawyer's date; it is a familiar legal practice in considering the date of any institution to seek out the oldest trust it administers". He also points out that Harvard's founding date is also the year in which the [[Massachusetts General Court]], the state legislature of [[Massachusetts]] at the time of its founding, resolved to establish a fund in a year's time for a school or college. Princeton claims its founding date is 1746, the date of its first charter. However, the exact words of the charter are unknown, the number and names of the trustees in the charter are unknown, and no known original of the charter is known to exist. Except for Columbia University, the majority of colonial-era colleges and universities do not have clear-cut dates of foundation.<ref>Edgar Potts Cheyney, "History of the University of Pennsylvania: 1740–1940", Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1940: pp. 45–52.</ref>}} |

|||

The first trace of an [[Ust'-Ishim man|early modern human]] in Russia dates back to 45,000 years, in [[Western Siberia]].<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Fu Q, Li H, Moorjani P, Jay F, Slepchenko SM, Bondarev AA, Johnson PL, Aximu-Petri A, Prüfer K, de Filippo C, Meyer M, Zwyns N, Salazar-García DC, Kuzmin YV, Keates SG, Kosintsev PA, Razhev DI, Richards MP, Peristov NV, Lachmann M, Douka K, Higham TF, Slatkin M, Hublin JJ, Reich D, Kelso J, Viola TB, Pääbo S|title=Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia |journal=Nature | issue= 7523| pages=445–449|date=23 October 2014|doi=10.1038/nature13810 | pmid=25341783 | volume=514 | pmc=4753769|bibcode=2014Natur.514..445F |hdl= 10550/42071}}</ref> The discovery of high concentration cultural remains of [[Human|anatomically modern humans]], from at least 40,000 years ago, was found at [[Kostyonki–Borshchyovo]],<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dinnis |first1=Rob |last2=Bessudnov |first2=Alexander |last3=Reynolds |first3=Natasha |last4=Devièse |first4=Thibaut |last5=Pate |first5=Abi |last6=Sablin |first6=Mikhail |last7=Sinitsyn |first7=Andrei |last8=Higham |first8=Thomas |title= New data for the Early Upper Paleolithic of Kostenki (Russia) |pmid=30777356 |doi=10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.11.012 |journal=[[Journal of Human Evolution]] |year=2019 |pages=21–40 |volume=127|s2cid=73486830 |url=https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01982049/file/Dinnis%20et%20al%202019%20New%20data%20for%20the%20EUP%20of%20Kostenki%20%28green%20open-access%20post-print%29.pdf }}</ref> and at [[Sungir]], dating back to 34,600 years ago—both in [[European Russia|western Russia]].<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1126/science.aao1807 |pmid=28982795 |title=Ancient genomes show social and reproductive behavior of early Upper Paleolithic foragers |journal=Science |volume=358 |issue=6363 |pages=659–662 |year=2017 |vauthors=Sikora, Martin ''et al.'' |bibcode=2017Sci...358..659S |doi-access=free }}</ref> Humans reached [[Far North (Russia)|Arctic Russia]] at least 40,000 years ago, in [[Mamontovaya Kurya]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Pavlov |first=Pavel |author2=John Inge Svendsen |author3=Svein Indrelid |date=6 September 2001 |title=Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago |journal=Nature |volume=413 |pages=64–67 | doi= 10.1038/35092552 |pmid=11544525 |issue=6851|bibcode=2001Natur.413...64P |s2cid=1986562 }}</ref> [[Ancient North Eurasian]] populations from Siberia genetically similar to [[Mal'ta–Buret' culture]] and [[Afontova Gora]] were an important genetic contributor to [[Ancient Beringian|Ancient Native Americans]] and [[Eastern Hunter-Gatherer]]s.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Balter |first1=M. |title=Ancient DNA Links Native Americans With Europe |journal=Science |date=25 October 2013 |volume=342 |issue=6157 |pages=409–410 |doi=10.1126/science.342.6157.409 |pmid=24159019 |bibcode=2013Sci...342..409B |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

Unlike the other [[colonial colleges]] that existed in 1749, including [[Harvard University|Harvard]], [[College of William & Mary|William & Mary]], [[Yale University|Yale]], and the [[Princeton University|College of New Jersey]], Franklin's new school did not focus exclusively on educating clergy. He advocated what was then an innovative concept of higher education, which taught both the ornamental knowledge of the arts and the practical skills necessary for making a living and performing public service. The proposed program of study could have become the nation's first modern liberal arts curriculum, although it was never implemented because [[Anglicanism|Anglican]] priest [[William Smith (Episcopal priest)|William Smith]], who became the first [[provost (education)|provost]], and other [[Board of Trustees|trustees]] strongly preferred the traditional curriculum.<ref name="Penn's Heritage">{{cite web|title=Penn's Heritage |url=http://www.upenn.edu/about/history |website=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=May 8, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160422090345/http://www.upenn.edu/about/history|archive-date=April 22, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>N. Landsman, From Colonials to Provincials: American Thought and Culture, 1680–1760 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), p. 30.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Yamnaya Steppe Pastoralists.jpg|thumb|320px|left|Bronze Age spread of [[Yamnaya culture|Yamnaya]] [[Western Steppe Herders|Steppe pastoralist]] ancestry between 3300 and 1500 BC,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gibbons |first1=Ann |title=Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population |journal=Science |date=21 February 2017 |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/thousands-horsemen-may-have-swept-bronze-age-europe-transforming-local-population}}</ref> including the [[Afanasievo culture]] of southern Siberia]] |

|||

Franklin assembled a board of trustees from among Philadelphia's leading citizens, the first such non-sectarian board in the nation. At the first meeting of the board of trustees on November 13, 1749, the issue of where to locate the school was a prime concern. Although a lot across Sixth Street from the old Pennsylvania State House, later renamed and famously known since 1776 as [[Independence Hall]], was offered without cost by [[James Logan (statesman)|James Logan]], its owner, the trustees realized that the building erected in 1740 by Edmund Woolley for George Whitefield,<ref>Extracts from the Pennsylvania Gazette, (January 3 to December 25, 1740) – Founders Online https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230826064004/https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-02-02-0065 |date=August 26, 2023 }}</ref> which was still vacant, was an even more preferable site. |

|||

The [[Kurgan hypothesis]] places the Volga-Dnieper region of southern Russia and [[Ukraine]] as the [[urheimat]] of the [[Proto-Indo-Europeans]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Anthony |first1=David W. |last2=Ringe |first2=Don |date=1 January 2015 |title=The Indo-European Homeland from Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives |journal=Annual Review of Linguistics |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=199–219 |doi=10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-124812 |issn=2333-9683|doi-access=free }}</ref> Early [[Indo-European migrations]] from the [[Pontic–Caspian steppe]] of Ukraine and Russia spread [[Yamnaya culture|Yamnaya]] ancestry and [[Indo-European languages]] across large parts of Eurasia.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Haak|first1=Wolfgang|last2=Lazaridis|first2=Iosif|last3=Patterson|first3=Nick|last4=Rohland|first4=Nadin|last5=Mallick|first5=Swapan|last6=Llamas|first6=Bastien|last7=Brandt|first7=Guido|last8=Nordenfelt|first8=Susanne|last9=Harney|first9=Eadaoin|last10=Stewardson|first10=Kristin|last11=Fu|first11=Qiaomei|date=11 June 2015|title=Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe|journal=Nature|volume=522|issue=7555|pages=207–211|doi=10.1038/nature14317|issn=0028-0836|pmc=5048219|pmid=25731166|bibcode=2015Natur.522..207H|arxiv=1502.02783}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/nomadic-herders-left-strong-genetic-mark-europeans-and-asians |first=Ann |last=Gibbons |date=10 June 2015 |title=Nomadic herders left a strong genetic mark on Europeans and Asians |journal=Science |publisher=AAAS}}</ref> [[Nomadic pastoralism]] developed in the Pontic–Caspian steppe beginning in the [[Chalcolithic]].<ref name="Belinskij-1999">{{Cite journal |last1=Belinskij |first1=Andrej |last2=Härke |first2=Heinrich |title=The 'Princess' of Ipatovo |journal=Archeology |volume=52 |issue=2 |year=1999 |url=http://cat.he.net/~archaeol/9903/newsbriefs/ipatovo.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080610043326/http://cat.he.net/~archaeol/9903/newsbriefs/ipatovo.html |archive-date=10 June 2008 |access-date=26 December 2007}}</ref> Remnants of these steppe civilizations were discovered in places such as [[Ipatovo kurgan|Ipatovo]],<ref name="Belinskij-1999"/> [[Sintashta]],<ref name="mounted">{{Cite book |author=Drews, Robert |title=Early Riders: The beginnings of mounted warfare in Asia and Europe |year=2004 |publisher=Routledge |location=New York |page=50 |isbn=978-0-415-32624-7}}</ref> [[Arkaim]],<ref>{{cite web |author=Koryakova, L. |title=Sintashta-Arkaim Culture |publisher=The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN) |url=http://www.csen.org/koryakova2/Korya.Sin.Ark.html |access-date=13 May 2021 |archive-date=28 February 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190228104055/http://www.csen.org/koryakova2/Korya.Sin.Ark.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> and [[Pazyryk burials|Pazyryk]],<ref>{{cite web |title=1998 NOVA documentary: "Ice Mummies: Siberian Ice Maiden" |work=Transcript |url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2517siberian.html |access-date=13 May 2021}}</ref> which bear the earliest known traces of [[horses in warfare]].<ref name="mounted"/> The genetic makeup of speakers of the [[Uralic language family|Uralic]] language family in northern Europe was shaped by migration from [[Siberia]] that began at least 3,500 years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lamnidis |first1=Thiseas C. |last2=Majander |first2=Kerttu |last3=Jeong |first3=Choongwon |last4=Salmela |first4=Elina |last5=Wessman |first5=Anna |last6=Moiseyev |first6=Vyacheslav |last7=Khartanovich |first7=Valery |last8=Balanovsky |first8=Oleg |last9=Ongyerth |first9=Matthias |last10=Weihmann |first10=Antje |last11=Sajantila |first11=Antti |last12=Kelso |first12=Janet |last13=Pääbo |first13=Svante |last14=Onkamo |first14=Päivi |last15=Haak |first15=Wolfgang |date=27 November 2018 |title=Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=9 |issue=1 |page=5018 |doi=10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5 |pmid=30479341 |pmc=6258758 |bibcode=2018NatCo...9.5018L |s2cid=53792952 |issn=2041-1723}}</ref> |

|||

The institution of higher learning was named and known as the College of Philadelphia from 1755 to 1779. In 1779, not trusting then provost [[William Smith (Episcopalian priest)|William Smith]]'s [[Loyalist (American Revolution)|Loyalist]] tendencies, the revolutionary State Legislature created a university, and in 1785 the legislature changed name to [[University of the State of Pennsylvania]].<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite web|title=Penn in the 18th Century, University of Pennsylvania Archives|url=http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html|publisher=University of Pennsylvania|access-date=April 29, 2006|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060428155156/http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1700s/penn1700s.html|archive-date=April 28, 2006|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{refn|group=note|"...(d) On November 27, 1779, the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania passed an act for the establishment of a University incorporating the rights and powers of the College, Academy, and Charitable School. This was the first designation of an institution in the United States as a University; |

|||

In the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the [[Goths|Gothic]] kingdom of [[Oium]] existed in southern Russia, which was later overrun by [[Huns]]. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries CE, the [[Bosporan Kingdom]], which was a Hellenistic [[polity]] that succeeded the Greek colonies,<ref>{{Cite book |author=Tsetskhladze, G. R. |title=The Greek Colonisation of the Black Sea Area: Historical Interpretation of Archaeology |publisher=F. Steiner |year=1998 |page=48 |isbn=978-3-515-07302-8}}</ref> was also overwhelmed by nomadic invasions led by warlike tribes such as the Huns and [[Pannonian Avars|Eurasian Avars]].<ref>{{Cite book |author=Turchin, P. |title=Historical Dynamics: Why States Rise and Fall |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2003 |pages=185–186 |isbn=978-0-691-11669-3}}</ref> The [[Khazars]], who were of [[Turkic peoples|Turkic origin]], ruled the steppes between the Caucasus in the south, to the east past the Volga river basin, and west as far as Kyiv on the Dnieper river until the 10th century.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Weinryb |first=Bernard D. |title=The Khazars: An Annotated Bibliography |journal=Studies in Bibliography and Booklore |publisher=[[Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion]] |volume=6 |number=3 |pages=111–129 |year=1963 |jstor=27943361}}</ref> After them came the [[Pechenegs]] who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the [[Cumans]] and the [[Kipchaks]].<ref>Carter V. Findley, ''The Turks in World History'' (Oxford University Press, 2004) {{ISBN|0-19-517726-6}}</ref> |

|||

(e) On September 22, 1785, an act was passed naming the University the University of the State of Pennsylvania..." See {{cite web |url=https://secretary.upenn.edu/trustees-governance/statutes-trustees#:~:text=(g)%20On%20September%2030%2C,time%20to%20time%2C%20is%20referred |title=Statues of the Trustees |publisher=University of Pennsylvania |access-date=September 12, 2022}}}} The result was a schism, with Smith continuing to operate an attenuated version of the College of Philadelphia. In 1791, the legislature issued a new charter, merging the two institutions into a new University of Pennsylvania with twelve men from each institution serving on the new board of trustees.<ref name=autogenerated1/> |

|||