Jammu

Jammu | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Nickname: City of Temples[1] | |

Interactive map of Jammu | |

![Jammu lies in the Jammu division (neon blue) of the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (shaded tan) in the disputed Kashmir region.[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/Kashmir_region._LOC_2003626427_-_showing_Jammu_division_administered_by_India_in_neon_blue.jpg/250px-Kashmir_region._LOC_2003626427_-_showing_Jammu_division_administered_by_India_in_neon_blue.jpg) Jammu lies in the Jammu division (neon blue) of the Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir (shaded tan) in the disputed Kashmir region.[2] | |

| Coordinates: 32°44′N 74°52′E / 32.73°N 74.87°E | |

| Administering country | India |

| Region of administration | Union territory of Jammu and Kashmir |

| District | Jammu |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Corporation |

| • Body | Jammu Municipal Corporation and Jammu Development Authority |

| • Mayor | Chander Mohan Gupta, BJP[3] |

| Area | |

• City | 240 km2 (90 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 300–400 m (1,000−1,300 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

• City | 502,197 |

| • Rank | 94th |

| • Density | 45/km2 (120/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 657,314 |

| Demonym(s) | Jammuwala, Jammuwale, Jammuites |

| Language | |

| • Official | Hindi,[6][7] Dogri,[8] Urdu,[9] Kashmiri, English |

| • Other | Punjabi[9][10] |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 180001[11] |

| Vehicle registration | JK-02 |

| Sex ratio | 867 ♀/ 1000 ♂ |

| Literacy | 90.14% |

| Distance from Delhi | 575 km (357 mi) NW |

| Distance from Mumbai | 1,971 km (1,225 mi) NE (land) |

| Climate | Cwa (Köppen) |

| Precipitation | 710 mm (28 in) |

| Avg. summer temperature | 29.6 °C (85.3 °F) |

| Avg. winter temperature | 17.7 °C (63.9 °F) |

| Website | jammu |

| |

Jammu (/ˈdʒʌmuː/) is a city in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir in the disputed Kashmir region.[2] It is the winter capital of Jammu and Kashmir, which is an Indian-administered union territory. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi, the city of Jammu, with an area of 240 km2 (93 sq mi),[4] is surrounded by the Himalayas in the north and the northern plains in the south. Jammu is the second-most populous city of the union territory. Jammu is known as "City of Temples" for its ancient temples and Hindu shrines.

Etymology

According to local tradition, Jammu is named after its founder, Raja Jambulochan, who is believed to have ruled the area in the 9th century.[12] Local tradition holds the city to be 3000 years old but this is not supported by historians.[13]

Geography

Jammu is located at 32°44′N 74°52′E / 32.73°N 74.87°E.[14] It has an average elevation of 300 m (980 ft). Jammu city is situated on a series of uneven ridges of low heights in the Shivalik hills. It is surrounded by the Shivalik range to the north, east, and southeast while the Trikuta Range borders it in the northwest. It is approximately 600 kilometres (370 mi) from the national capital, New Delhi.

The city straddles the Tawi river. The old city overlooks the river from the north (right bank) while the new neighbourhoods are spread around the southern side (left bank) of the river. There are five bridges over the river.

History

According to Tarikh-i-Azmi, Jammu came into existence around 900 CE. The state of Durgara (modern forms "Duggar" and "Dogra)") is also attested from around this time.[15][16] The capital of the Durgara state at that time is believed to have been Vallapura (identified with modern Billawar). Its rulers are repeatedly mentioned in Kalhana's Rajatarangini.[17] Babbapura (modern Babor) is another state mentioned in Rajatarangini, some of whose rulers also appear by in the Vamshavali (family chronicles) of later Jammu rulers. These rulers are believed to have enjoyed almost independent status and allied themselves with the Sultans of Delhi.

Jammu is mentioned by name in the chronicles of Timur (r. 1370–1406), who invaded Delhi in 1398 and returned to Samarkand via Jammu. Raja Bhim Dev is prominently mentioned in the Delhi chronicles as a supporter of Mubarah Shah (r. 1421–1434) against Jasrat.[18] Between 1423 and 1442, Jammu came under control of Jasrat (r. 1405–1442) who conquered it after killing his arch-enemy Bhim Dev in 1423. Later, Jasrat appointed Manik Dev (also known as Ajeo Dev) as vassal, and married his daughter.[19] In the Mughal chronicles of Babur in the early 16th century, Jammu is mentioned as a powerful state in the Punjab hills. It is said to have been ruled by Manhas Rajputs. Emperor Akbar brought the hill kingdoms of the region under Mughal suzerainty, but the kings enjoyed considerable political autonomy. In addition to Jammu, other kingdoms of the region such as Kishtwar and Rajauri were also prominently mentioned. It is evident that the Mughal empire treated these hill chiefs as allies and partners in the empire.[20]

Modern history

After the decline of the Mughal power in the 18th century, the Jammu state under Raja Dhruv Dev of the Jamuwal (Jamwal) family asserted its supremacy among the Dugar states. Its ascent reached its peak under his successor, Raja Ranjit Dev (r. 1728–1780), who was widely respected among the hill states.[21][22] Ranjit Dev promoted religious freedom and security, which attracted many craftsmen and traders to settle in Jammu, contributing to its economic prosperity.[23]

Towards the end of Ranjit Dev's rule, the Sikh clans of Punjab (misls) gained ascendency, and Jammu began to be contested by the Bhangi, Kanhaiya and Sukerchakia misls. Around 1770, the Bhangi misl attacked Jammu and forced Ranjit Dev to become a tributary. Brij Lal Dev, Ranjit Dev's successor, was defeated by the Sukerchakia chief Mahan Singh, who sacked Jammu and plundered it. Thus Jammu lost its supremacy over the surrounding country. In the Battle of Rumal, the Jammu ruler was killed by Sikhs.[24][25]

In 1808, Jammu itself was annexed to the Sikh Empire by Ranjit Singh, the son of Mahan Singh.[26]

In 1818 Raja Kishore Singh, father of Raja Gulab Singh, was appointed and anointed the ruler of Jammu principality, and hence started the Jamwal dynasty, aka Dogra dynasty, which came to rule the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir under British suzerainty. The rulers built large temples, renovated old shrines, built educational institutes and many more. A 43 km long railway line connecting Jammu with Sialkot was laid in 1897[27]

Jammu has historically been the capital of Jammu Province and the winter capital of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (1846–1952).

After the partition of India, Jammu continues as the winter capital of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Battles

- Battle of Jammu (1712)

- Battle of Rumal[28]

- Battle of Jammu (1808)[29]

Climate

Jammu, like the rest of north-western India, features a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cwa), with extreme summer highs reaching 46 °C (115 °F), and temperatures in the winter months occasionally falling below 4 °C (39 °F). June is the hottest month with average highs of 40.6 °C (105.1 °F), while January is the coldest month with average lows reaching 7 °C (45 °F). Average yearly precipitation is about 1,400 mm (55 in) with the bulk of the rainfall in the months from June to September, although the winters can also be rather wet. In winter dense smog causes much inconvenience and temperature even drops to 2 °C (36 °F). In summer, particularly in May and June, extremely intense sunlight or hot winds can raise the temperature to 46 °C (115 °F). Following the hot season, the monsoon lashes the city with heavy downpours along with thunderstorms; rainfall may total up to 669 mm (26.3 in) in the wettest months. The city is exposed to heatwaves.[clarification needed]

Highest recorded temperature: 47.4 °C (117.3 °F) on 31 May 1988.[30]

Lowest recorded temperature: 0.5 °C (32.9 °F) on 24 January 2016.[30]

| Climate data for Jammu (1991–2020, extremes 1925–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28.0 (82.4) |

31.7 (89.1) |

37.3 (99.1) |

43.9 (111.0) |

47.4 (117.3) |

47.2 (117.0) |

45.0 (113.0) |

41.7 (107.1) |

39.2 (102.6) |

37.9 (100.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.5 (83.3) |

47.4 (117.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.1 (64.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

32.7 (90.9) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.8 (91.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

29.5 (85.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.7 (67.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

18.0 (64.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.5 (47.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 67.9 (2.67) |

74.6 (2.94) |

64.1 (2.52) |

41.4 (1.63) |

22.5 (0.89) |

109.5 (4.31) |

416.5 (16.40) |

403.1 (15.87) |

144.8 (5.70) |

23.5 (0.93) |

12.2 (0.48) |

21.9 (0.86) |

1,402 (55.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.3 mm) | 5.3 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 8.7 | 17 | 16.7 | 8.4 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 87.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 68 | 60 | 45 | 38 | 49 | 73 | 78 | 74 | 64 | 68 | 75 | 64 |

| Source: NCEI[30] | |||||||||||||

Transport

Jammu city has a railway station called Jammu Tawi (station code JAT) that is connected with major cities of India. The old railway link to Sialkot was suspended by Pakistan in September 1947, and Jammu had no rail services until 1971, when the Indian Railways laid the Pathankot-Jammu Tawi Broad Gauge line. The new Jammu Tawi station opened in October 1972 and is an origination point for express trains. With the commencement of the Jammu–Baramulla line, all trains to the Kashmir Valley will pass through Jammu Tawi. A part of the Jammu–Baramulla project has been executed and the track has been extended to Katra. Jalandhar - Pathankot-Jammu Tawi section has been doubled and electrified.

National Highway 44 which passes through Jammu connects it to the Kashmir valley. National Highway 1B connects Jammu with Poonch town. Jammu is 80 kilometres (50 mi) from Kathua town, while it is 68 kilometres (42 mi) from Udhampur city. The famous pilgrimage town of Katra is 49 kilometres (30 mi) from Jammu.

Jammu Airport is in the middle of Jammu. It has direct flights to Srinagar, Delhi, Amritsar, Chandigarh, Leh, Mumbai and Bengaluru. Jammu Airport operates daily 30 arrival and departure of flights which are served by Go First, Air India, SpiceJet, IndiGo and Vistara.

The city has JKSRTC city buses and minibusses for local transport which run on some defined routes. These minibusses are called "Matadors". Besides this auto-rickshaw and cycle-rickshaw service is also available. Local taxis are also available.

Administration

Jammu city serves as the winter capital of Jammu and Kashmir state from November to April when all the offices move from Srinagar to Jammu. Srinagar serves as the summer capital from May to October.[31] Jammu was a municipal committee during 2001 census of India. With effect from 5 September 2003, it has upgraded status of a municipal corporation.[32]

Economy

Jammu city is the main cultural and economic centre of the administrative division of Jammu. A famous local basmati rice is produced in the RS Pura area near Jammu, and processed in rice mills in Jammu. The industrial estate at Bari Brahamna has a large presence of industrial units manufacturing a variety of products including carpets and electronic goods.

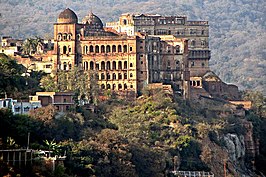

Tourism

Tourism is the largest industry in Jammu city. It is also a focal point for the pilgrims going to Vaishno Devi and Kashmir valley as it is second last railway terminal in North India. All the routes leading to Kashmir, Poonch, Doda and Laddakh start from Jammu city. So throughout the year, the city remains full of people from all the parts of India. Places of interest include old historic palaces like Mubarak Mandi Palace, Purani Mandi, Rani Park, Amar Mahal, Bahu Fort, Raghunath Temple, Ranbireshwar Temple, Karbala, Peer Meetha, Old city.

Demographics

As of 2011 census,[35] the population of Jammu city was 502,197. Males constituted 52.7% of the population; females numbered constituted 47.3% of the population. The sex ratio was 898 females per 1,000 males against the national average of 940. Jammu had an average literacy rate of 89.66%, much higher than the national average of 74.4%: male literacy was 93.13% and female literacy was 85.82%. 8.47% of the population were under 6 years of age. The urban agglomeration of Jammu had a population of 657,314.[36] Most of Jammu and Kashmir's Hindus live in the Jammu region; many speak Dogri.[37]

| Rank | Language | 1961[10] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dogri | 55% |

| 2 | Punjabi | 22% |

| 3 | Hindi | 11.6% |

| — | Other | 11.4% |

Muslim communities

The city of Jammu had a significant Muslim population prior to the Partition of India, 30.4 per cent by the 1941 census.[38] During the 1947 Jammu massacres, which preceded and continued during the Pakistan tribal invasion of Kashmir, many Muslims were killed and many driven away to Pakistan. The estimates of the number killed in the whole province vary between 20,000 and 100,000. The killings were carried out by extremist Hindus and Sikhs, allegedly orchestrated by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, and aided and abetted by the state forces and the Maharaja Hari Singh.[39][40][41]

As a result of the violence and migration, by 1961, about 17.2 per cent of the population in the city of Jammu was Muslim.[42][43] The displaced Muslims took refuge in the Sialkot District and other parts of Pakistani Punjab. Many prominent Punjabi residents in Pakistan, including politician Chaudhry Amir Hussain, economist Mahbub ul Haq, Air Marshal Asghar Khan, journalist Khalid Hasan and singer Malika Pukhraj were from Jammu.[44] A large number of these refugees also returned and resettled in the territory.[45][46]

Education

In the 2014–2015 General Budget of India, Arun Jaitley, the Finance Minister of India, proposed an Indian Institute of Technology and an Indian Institute of Management for the division. List of some educational institutions is provided below.

Engineering Colleges in Jammu

- Indian Institute of Technology Jammu

- Government College of Engineering and Technology, Jammu

- Model Institute of Engineering and Technology, Jammu

- Yogananda College of Engineering and Technology, Jammu

- University Institute of Engineering and Technology, University of Jammu

Medical Institutions

Legal Institutions

- Kishen Chand Law College, Jammu

- Dogra Law College, Jammu

- Calliope School of Legal Studies, Jammu

- R. K. Law College, Jammu

General Degree Courses (colleges)

Universities

- Central University of Jammu

- Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Jammu

- University of Jammu

Schools

Cuisine

Jammu is known for its sund panjeeri, patisa, rajma with rice and Kalari cheese. Dogri food specialties include ambal, khatta meat, kulthein di dal, dal patt, maa da madra, rajma, and auriya. Pickles typical of Jammu are made of kasrod, girgle, mango with saunf, jimikand, tyaoo, seyoo, and potatoes. Auriya is a dish made with potatoes. Jammu cuisine features various chaats, especially gol gappas, kachalu, Chole bhature, gulgule, rajma kulche and dahi palla, among various others.[47]

Refugees

Kashmiri Pandit refugees

Being comparatively safe from terrorism, Jammu city has become a hub of refugees. These primarily include Kashmiri Hindus who migrated from Kashmir Valley in 1989. Hindus from Pakistan-administered Jammu and Kashmir who migrated to India have also settled in Jammu city. According to records, approximately 31,619 Hindu families had migrated from Pakistan administered Jammu and Kashmir to India. Of these 26,319 families are settled in Jammu.[citation needed]

Rohingya refugees

Rohingyas who fled Myanmar during 2016 have also currently settled in Jammu.[48][49] Some believes the settlements of Rohingya Muslims have also raised security threats in Jammu.[50][51][52] During the 2018 Sunjuwan attack, intelligence agencies suspected but did not prove involvement of Rohingya Muslims in the attack.[53][54][55]

Notable people

- Maulana Abdur Rahman, member of the 2nd Lok Sabha

References

- ^ "Jammu-Srinagar NH reopens for one-way traffic". Business Standard India. Press Trust of India. 30 January 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

Jammu, the City of Temples, recorded a low of 7.7 degrees Celsius compared to the previous night's 4.1 degrees Celsius

- ^ a b The application of the term "administered" to the various regions of Kashmir and a mention of the Kashmir dispute is supported by the tertiary sources (a) through (d), reflecting due weight in the coverage. Although "controlled" and "held" are also applied neutrally to the names of the disputants or to the regions administered by them, as evidenced in sources (f) through (h) below, "held" is also considered politicised usage, as is the term "occupied," (see (i) below).

(a) Kashmir, region Indian subcontinent, Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 15 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Kashmir, region of the northwestern Indian subcontinent ... has been the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan since the partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. The northern and western portions are administered by Pakistan and comprise three areas: Azad Kashmir, Gilgit, and Baltistan, the last two being part of a territory called the Northern Areas. Administered by India are the southern and southeastern portions, which constitute the state of Jammu and Kashmir but are slated to be split into two union territories.";

(b) Pletcher, Kenneth, Aksai Chin, Plateau Region, Asia, Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 16 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "Aksai Chin, Chinese (Pinyin) Aksayqin, portion of the Kashmir region, at the northernmost extent of the Indian subcontinent in south-central Asia. It constitutes nearly all the territory of the Chinese-administered sector of Kashmir that is claimed by India to be part of the Ladakh area of Jammu and Kashmir state.";

(c) "Kashmir", Encyclopedia Americana, Scholastic Library Publishing, 2006, p. 328, ISBN 978-0-7172-0139-6 C. E Bosworth, University of Manchester Quote: "KASHMIR, kash'mer, the northernmost region of the Indian subcontinent, administered partlv by India, partly by Pakistan, and partly by China. The region has been the subject of a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan since they became independent in 1947";

(d) Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003), Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: G to M, Taylor & Francis, pp. 1191–, ISBN 978-0-415-93922-5 Quote: "Jammu and Kashmir: Territory in northwestern India, subject to a dispute betw een India and Pakistan. It has borders with Pakistan and China."

(e) Talbot, Ian (2016), A History of Modern South Asia: Politics, States, Diasporas, Yale University Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 978-0-300-19694-8 Quote: "We move from a disputed international border to a dotted line on the map that represents a military border not recognized in international law. The line of control separates the Indian and Pakistani administered areas of the former Princely State of Jammu and Kashmir.";

(f) Kashmir, region Indian subcontinent, Encyclopaedia Britannica, retrieved 15 August 2019 (subscription required) Quote: "... China became active in the eastern area of Kashmir in the 1950s and has controlled the northeastern part of Ladakh (the easternmost portion of the region) since 1962.";

(g) Bose, Sumantra (2009), Kashmir: Roots of Conflict, Paths to Peace, Harvard University Press, pp. 294, 291, 293, ISBN 978-0-674-02855-5 Quote: "J&K: Jammu and Kashmir. The former princely state that is the subject of the Kashmir dispute. Besides IJK (Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir. The larger and more populous part of the former princely state. It has a population of slightly over 10 million, and comprises three regions: Kashmir Valley, Jammu, and Ladakh.) and AJK ('Azad" (Free) Jammu and Kashmir. The more populous part of Pakistani-controlled J&K, with a population of approximately 2.5 million. AJK has six districts: Muzaffarabad, Mirpur, Bagh, Kodi, Rawalakot, and Poonch. Its capital is the town of Muzaffarabad. AJK has its own institutions, but its political life is heavily controlled by Pakistani authorities, especially the military), it includes the sparsely populated "Northern Areas" of Gilgit and Baltistan, remote mountainous regions which are directly administered, unlike AJK, by the Pakistani central authorities, and some high-altitude uninhabitable tracts under Chinese control."

(h) Fisher, Michael H. (2018), An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge University Press, p. 166, ISBN 978-1-107-11162-2 Quote: "Kashmir’s identity remains hotly disputed with a UN-supervised “Line of Control” still separating Pakistani-held Azad (“Free”) Kashmir from Indian-held Kashmir.";

(i) Snedden, Christopher (2015), Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris, Oxford University Press, p. 10, ISBN 978-1-84904-621-3 Quote:"Some politicised terms also are used to describe parts of J&K. These terms include the words 'occupied' and 'held'." - ^ PTI (15 November 2018). "Jammu gets new mayor, deputy mayor | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ a b "Jammu City".

- ^ Akhtar, Rais (2009). Regional Planning for Health Care System in Jammu and Kashmir. Concept Publishing Company. p. 1. ISBN 9788180696275.

- ^ "The Jammu and Kashmir Official Languages Act, 2020" (PDF). The Gazette of India. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Parliament passes JK Official Languages Bill, 2020". Rising Kashmir. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Pathak, Analiza (2 September 2020). "Hindi, Kashmiri and Dogri to be official languages of Jammu and Kashmir, Cabinet approves Bill". Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ a b "52nd Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India" (PDF). nclm.nic.in. Ministry of Minority Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ^ a b Kashmir, India Superintendent of Census Operations, Jammu and; Kamili, M. H. (1966). "District Census Handbook, Jammu & Kashmir: Jammu" – via Google Books.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Department of Posts, Ministry of Communications, Government of India (16 March 2017). "Village/Locality based Pin mapping as on 16th March 2017". data.gov.in. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Priya Sethi lays foundation stone of statue of Jambu Lochan". Daily Excelsior. 1 August 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Kapur, History of Jammu and Kashmir State 1980, p. 9.

- ^ "Maps, Weather, and Airports for Jammu, India". www.fallingrain.com.

- ^ Kapur, History of Jammu and Kashmir State 1980, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Charak & Billwaria, Pahāṛi Styles of Indian Murals 1998, p. 6.

- ^ Bamzai, Culture and Political History of Kashmir 1994, p. 184.

- ^ Charak & Billwaria, Pahāṛi Styles of Indian Murals 1998, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Charak, Sukh Dev Singh (1985). A Short History of Jammu Raj: From Earliest Times to 1846 A.D. Ajaya Prakashan. pp. 76–78.

- ^ Jigar Mohammad, Raja Ranjit Dev's Inclusive Policies 2010, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Jeratha, Dogra Legends of Art & Culture 1998, p. 187.

- ^ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 10.

- ^ Rai, Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects 2004, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Sukhdev Singh Charak (1978). Indian Conquest of the Himalayan Territories. Ajaya Prakashan, Jammu. p. 37.

- ^ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 10–12.

- ^ Panikkar, Gulab Singh 1930, p. 15–16.

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 14, page 49 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". dsal.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Hari Ram Gupta (1982). History Of The Sikhs Vol. IV The Sikh Commonwealth Or Rise And Fall Of Sikh Misls. pp. 339–340.

- ^ Sandhu, Autar Singh (1935), General Hari Singh Nalwa, Lahore: Cunningham Historical Society

- ^ a b c "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020: Jammu" (XLSX). ncei.noaa.gov. NOAA. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

WMO number: 42056

- ^ "Scheme for voting by postal ballot by a person holding any office under the Govt. and verified to be moving along with the headquarters of the Govt. from Kashmir Province to Jammu Province or vice-versa" (PDF). Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Jammu and Kashmir. p. 1. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

...the State Govt. functions for six months (November to April) in the winter capital Jammu after which it moves to the summer capital Srinagar...

- ^ "History of Jammu Municipal Corporation". Official website of Jammu Municipal Corporation. Archived from the original on 10 April 2009. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "Jammu City Population". Census India. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "Jammu City Population Census 2011-2019 | Jammu and Kashmir". www.census2011.co.in.

- ^ "Jammu Municipal Corporation Demographics". Census of India. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Jammu & Kashmir (India): State, Major Agglomerations & Cities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". City Population. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- ^ "Jammu and Kashmir". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 May 2023.

- ^ Wreford, R.G. "Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF). 1941 Census of India. pp. 102, 103.

- ^ Ved Bhasin (17 November 2015). "Jammu 1947". Kashmir Life. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Chattha, Partition and its Aftermath 2009, p. 182, 183.

- ^ Singh, Amritjit; Iyer, Nalini; Gairola, Rahul K. (15 June 2016). Revisiting India's Partition: New Essays on Memory, Culture, and Politics. Lexington Books. p. 149. ISBN 9781498531054.

- ^ Kamili, H.M. "Jammu and Kashmir, District Census Handbook, 7, Jammu District" (PDF). 1961 Census of India. Jammu and Kashmir Government. p. 42.

- ^ Luv Puri, Across the Line of Control 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Luv Puri, Across the Line of Control 2012, pp. 3, 31.

- ^ Saraf, Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2 2015, p. 481: "Towards the middle of 1949, a movement for return started on a small scale which gained momentum by the end of 1950. A fair estimate of the returnees is about a hundred thousand. Sheikh Abdullah's Government re-settled them on their abandoned properties, advanced taqqavi loans and appointed a special staff to look after their problems."

- ^ Jammu & Kashmir, 1947–50: An Account of Activities of First Three Years of Sheikh Abdullah's Government, Printed at the Ranbir Government Press, 1951, p. 90

- ^ "Jammu Pincode". citypincode.in. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ Sharma, Arjun (16 August 2018). "As Jammu becomes home for refugees from four communities, govt has to deal with complex issue of rights". Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Sharma, Shivani. "Paradise Lost - the Kashmiri Pandits". Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ Excelsior, Daily (11 January 2017). "Demographic changes make Jammu a "Ticking Time Bomb"". Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Jain, Sandhya (15 May 2018). "Rohingya refugees: A threat to Jammu". The Pioneer. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ IANS (19 February 2019). "Demographic changes in Assam, Bengal, J&K, Kerala aided rise of fundamentalist forces: Himanta". Business Standard India. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Sharma, Arteev (6 February 2019). "'Illegal settlement' of Rohingya to be probed by security agencies". Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

After terror attack on the Sunjuwan military station in February last year, Rohingya again came under the radar of security agencies as their alleged role in assisting militants was probed. However, their involvement has not been established as yet.

- ^ Yhome, K. "Examining India's stance on the Rohingya crisis". Retrieved 21 March 2019.

In early February 2018, a terrorist attack on an army camp in Sunjuwan of Jammu city sparked a debate on the involvement of Rohingyas as many had settled around the camp.

- ^ Jain, Bharti; Dua, Rohan (11 February 2018). "Sunjuwan Attack: After intelligence inputs, forces were told to be on alert". The Times of India. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

Bibliography

- Bamzai, P. N. K. (1994), Culture and Political History of Kashmir: Ancient Kashmir, M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd., ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0

- Charak, Sukh Dev Singh; Billawaria, Anita K. (1998), Pahāṛi Styles of Indian Murals, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-8-17017-356-4

- Chattha, Ilyas Ahmad (September 2009). Partition and Its Aftermath: Violence, Migration and the Role of Refugees in the Socio-Economic Development of Gujranwala and Sialkot Cities, 1947-1961 (PhD). Centre for Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies, School of Humanities, University of Southampton. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Jeratha, Aśoka (1998), Dogra Legends of Art & Culture, Indus Publishing, ISBN 978-81-7387-082-8

- Kapur, Manohar Lal (1980), History of Jammu and Kashmir State: The making of the State, Kashmir History Publications

- Mohammad, Jigar (November 2010), "Raja Ranjit Dev's Inclusive Policies and Politico-economic developments in Jammu", Epilogue, vol. 4, no. 11, pp. 40–42

- Panikkar, K. M. (1930), Gulab Singh, London: Martin Hopkinson Ltd

- Puri, Luv (2012), Across the Line of Control: Inside Azad Kashmir, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-80084-6

- Rai, Mridu (2004), Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir, C. Hurst & Co, ISBN 1850656614

- Saraf, Muhammad Yusuf (2015) [first published 1979 by Ferozsons], Kashmiris Fight for Freedom, Volume 2, Mirpur: National Institute Kashmir Studies

External links

Jammu travel guide from Wikivoyage

Jammu travel guide from Wikivoyage