The Holocaust: Difference between revisions

Valenciano (talk | contribs) Undid revision 614491234 by Frank G Anderson (talk) weasel words |

m →Etymology and use of the term: Earliest recorded use of the term Holocaust (Holocaustum) in England. Plus ref |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==Etymology and use of the term== |

==Etymology and use of the term== |

||

{{main|Names of the Holocaust}} |

{{main|Names of the Holocaust}} |

||

The term ''holocaust'' comes from the [[Greek language|Greek]] word ''[[Holocaust (sacrifice)|holókauston]]'', referring to an [[animal sacrifice]] offered to a god in which the whole (''olos'') animal is completely burnt (''kaustos'').<ref>[http://www.ushmm.org/research/library/faq/details.php?topic=01#02 "What is the origin of the word 'Holocaust'?"]. [[United States Holocaust Memorial Museum]]. Retrieved 25 September 2012.</ref> For hundreds of years, the word "holocaust" was used in English to denote great massacres. Since the 1960s, the term has come to be used by scholars and popular writers to refer to the Nazi genocide of Jews.<ref>{{Harvnb|Niewyk|Nicosia|2000|p=45}}.</ref> The television mini-series [[Holocaust (TV miniseries)|''Holocaust'']] is credited with introducing the term into common parlance after 1978.<ref name="Steinweis">[[#CITEREFSteinweis2001|Steinweis 2001]] provides a survey of this phenomenon.</ref> |

The term ''holocaust'' comes from the [[Greek language|Greek]] word ''[[Holocaust (sacrifice)|holókauston]]'', referring to an [[animal sacrifice]] offered to a god in which the whole (''olos'') animal is completely burnt (''kaustos'').<ref>[http://www.ushmm.org/research/library/faq/details.php?topic=01#02 "What is the origin of the word 'Holocaust'?"]. [[United States Holocaust Memorial Museum]]. Retrieved 25 September 2012.</ref> [[Richard of Devizes]], a 12th century monk and chronicler, was the first to use the term "holocaustum" in Britain. The term was used in reference to an attack on Jews that took place upon the coronation of [[Richard the Lionheart]].<ref>http://familytreemaker.genealogy.com/users/n/e/u/Michael-R-Neuman-Costa-Mesa/WEBSITE-0001/UHP-0707.html Richard 'Lionheart' Plantagenet, King of England (b. September 08, 1157, d. April 06, 1199)</ref> For hundreds of years, the word "holocaust" was used in English to denote great massacres. Since the 1960s, the term has come to be used by scholars and popular writers to refer to the Nazi genocide of Jews.<ref>{{Harvnb|Niewyk|Nicosia|2000|p=45}}.</ref> The television mini-series [[Holocaust (TV miniseries)|''Holocaust'']] is credited with introducing the term into common parlance after 1978.<ref name="Steinweis">[[#CITEREFSteinweis2001|Steinweis 2001]] provides a survey of this phenomenon.</ref> |

||

The biblical word ''shoah'' (שואה; also transliterated ''sho'ah'' and ''shoa''), meaning "calamity", became the standard [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] term for the Holocaust as early as the 1940s, especially in Europe and Israel.<ref name="yad def">[http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/holocaust/resource_center/the_holocaust.asp "The Holocaust: Definition and Preliminary Discussion"], [[Yad Vashem]]. Retrieved 24 September 2012.</ref> ''Shoah'' is preferred by many{{citation needed|date=November 2013}}{{who|date=November 2013}} Jews for a number of reasons, including the theologically offensive nature of the word "holocaust", which they take to refer to the Greek pagan custom.<ref>For example, Israeli journalist [[Amira Hass]], the daughter of two Holocaust survivors and translator of the 2009 English edition of her mother's diary of surviving Bergen-Belsen ({{Harvnb|Lévy-Hass|2009}}), has argued that " 'The Holocaust' is an incorrect term … as if something came out from the sky, from heaven, some disaster, a calamity, a nature calamity, and not human-made calamity." Asked for a better way to refer to it, she responded, "The German industry of murder. Or the assembly-line of [mass] murder." [http://www.democracynow.org/2009/6/8/diary_of_bergen_belson_1944_1945 "Diary of Bergen-Belsen, 1944-1945": Amira Hass Discusses Her Mother's Concentration Camp Diary]<p>For an opposing view on the allegedly offensive nature of the meaning of the word ''holocaust'', see [[#CITEREFPetrie2000|Peterie 2000]].</ref> |

The biblical word ''shoah'' (שואה; also transliterated ''sho'ah'' and ''shoa''), meaning "calamity", became the standard [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] term for the Holocaust as early as the 1940s, especially in Europe and Israel.<ref name="yad def">[http://www1.yadvashem.org/yv/en/holocaust/resource_center/the_holocaust.asp "The Holocaust: Definition and Preliminary Discussion"], [[Yad Vashem]]. Retrieved 24 September 2012.</ref> ''Shoah'' is preferred by many{{citation needed|date=November 2013}}{{who|date=November 2013}} Jews for a number of reasons, including the theologically offensive nature of the word "holocaust", which they take to refer to the Greek pagan custom.<ref>For example, Israeli journalist [[Amira Hass]], the daughter of two Holocaust survivors and translator of the 2009 English edition of her mother's diary of surviving Bergen-Belsen ({{Harvnb|Lévy-Hass|2009}}), has argued that " 'The Holocaust' is an incorrect term … as if something came out from the sky, from heaven, some disaster, a calamity, a nature calamity, and not human-made calamity." Asked for a better way to refer to it, she responded, "The German industry of murder. Or the assembly-line of [mass] murder." [http://www.democracynow.org/2009/6/8/diary_of_bergen_belson_1944_1945 "Diary of Bergen-Belsen, 1944-1945": Amira Hass Discusses Her Mother's Concentration Camp Diary]<p>For an opposing view on the allegedly offensive nature of the meaning of the word ''holocaust'', see [[#CITEREFPetrie2000|Peterie 2000]].</ref> |

||

Revision as of 15:03, 27 June 2014

| Part of a series on |

| The Holocaust |

|---|

|

The Holocaust (from the Greek ὁλόκαυστος holókaustos: hólos, "whole" and kaustós, "burnt")[2] also known as Shoah (Hebrew: השואה, HaShoah, "the catastrophe"; Yiddish: חורבן, Churben or Hurban, from the Hebrew for "destruction"), was a genocide in which approximately six million Jews were killed by the German military, under the command of Adolf Hitler, and its collaborators. Killings took place throughout the German Reich and German-occupied territories.[3]

Between 1941 and 1945 Jews, Gypsies, Slavs, communists, homosexuals, the mentally and physically disabled and members of other groups were targeted and methodically murdered in the largest genocide of the 20th century. In total approximately 11 million people were killed during the Holocaust including over 1 million children.[4][5] Of the nine million Jews who had resided in Europe before the Holocaust, approximately two-thirds were killed.[6]

A network of about 42,500 facilities in Germany and German-occupied territories were used to concentrate, confine, and kill Jews and other victims[7] and between 100,000 to 500,000 people were direct participants in the planning and murder of Holocaust victims.[8]

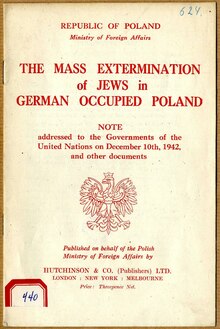

The persecution and genocide were carried out in stages. Initially the German government passed laws to exclude Jews from civil society, most prominently the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. A network of concentration camps was established starting in 1933 and ghettos were established following the outbreak of World War II in 1939. In 1941, as Germany conquered new territory in eastern Europe, specialized paramilitary units called Einsatzgruppen were used to murder around two million Jews and political opponents in mass shootings. By the end of 1942, victims were being regularly transported by freight train to specially built extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, most were systematically killed in gas chambers. The campaign of murder continued until the end of World War II in Europe in April–May 1945.

Etymology and use of the term

The term holocaust comes from the Greek word holókauston, referring to an animal sacrifice offered to a god in which the whole (olos) animal is completely burnt (kaustos).[9] Richard of Devizes, a 12th century monk and chronicler, was the first to use the term "holocaustum" in Britain. The term was used in reference to an attack on Jews that took place upon the coronation of Richard the Lionheart.[10] For hundreds of years, the word "holocaust" was used in English to denote great massacres. Since the 1960s, the term has come to be used by scholars and popular writers to refer to the Nazi genocide of Jews.[11] The television mini-series Holocaust is credited with introducing the term into common parlance after 1978.[12]

The biblical word shoah (שואה; also transliterated sho'ah and shoa), meaning "calamity", became the standard Hebrew term for the Holocaust as early as the 1940s, especially in Europe and Israel.[13] Shoah is preferred by many[citation needed][who?] Jews for a number of reasons, including the theologically offensive nature of the word "holocaust", which they take to refer to the Greek pagan custom.[14]

The Nazis used a euphemistic phrase, the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" (German: Endlösung der Judenfrage), and the phrase "Final Solution" has been widely used as a term for the genocide of the Jews. Nazis used the phrase lebensunwertes Leben (Life unworthy of life) in reference to their victims in an attempt to justify the killings.

Distinctive features

Institutional collaboration

Every arm of Germany's bureaucracy was involved in the logistics that led to the genocides, turning the Third Reich into what one Holocaust scholar, Michael Berenbaum, has called "a genocidal state".[15]

Every arm of the country's sophisticated bureaucracy was involved in the killing process. Parish churches and the Interior Ministry supplied birth records showing who was Jewish; the Post Office delivered the deportation and denaturalization orders; the Finance Ministry confiscated Jewish property; German firms fired Jewish workers and disenfranchised Jewish stockholders.

The universities refused to admit Jews, denied degrees to those already studying, and fired Jewish academics; government transport offices arranged the trains for deportation to the camps; German pharmaceutical companies tested drugs on camp prisoners; companies bid for the contracts to build the crematoria; detailed lists of victims were drawn up using the Dehomag (IBM Germany) company's punch card machines, producing meticulous records of the killings. As prisoners entered the death camps, they were made to surrender all personal property, which was catalogued and tagged before being sent to Germany to be reused or recycled. Berenbaum writes that the Final Solution of the Jewish question was "in the eyes of the perpetrators ... Germany's greatest achievement."[16] Through a concealed account, the German national bank helped launder valuables stolen from the victims.

Saul Friedländer writes that: "Not one social group, not one religious community, not one scholarly institution or professional association in Germany and throughout Europe declared its solidarity with the Jews."[17] He writes that some Christian churches declared that converted Jews should be regarded as part of the flock, but even then only up to a point. Friedländer argues that this makes the Holocaust distinctive because antisemitic policies were able to unfold without the interference of countervailing forces of the kind normally found in advanced societies, such as industry, small businesses, churches, trade unions and other vested interests and lobby groups.[17]

Ideology and scale

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

In other genocides, pragmatic considerations such as control of territory and resources were central to the genocide policy. Israeli historian and scholar Yehuda Bauer argues that:

The basic motivation [of the Holocaust] was purely ideological, rooted in an illusionary world of Nazi imagination, where an international Jewish conspiracy to control the world was opposed to a parallel Aryan quest. No genocide to date had been based so completely on myths, on hallucinations, on abstract, nonpragmatic ideology—which was then executed by very rational, pragmatic means.[18]

German historian Eberhard Jäckel wrote in 1986 that one distinctive feature of the Holocaust was that:

never before had a state with the authority of its responsible leader decided and announced that a specific human group, including its aged, its women and its children and infants, would be killed as quickly as possible, and then carried through this resolution using every possible means of state power.[19]

The killings were systematically conducted in virtually all areas of German-occupied territory in what are now 35 separate European countries.[20] It was at its most severe in Central and Eastern Europe, which had more than seven million Jews in 1939. About five million Jews were killed there, including three million in occupied Poland and over one million in the Soviet Union. Hundreds of thousands also died in the Netherlands, France, Belgium, Yugoslavia, and Greece. The Wannsee Protocol makes it clear that the Nazis intended to carry their "final solution of the Jewish question" to Britain and all neutral states in Europe, such as Ireland, Switzerland, Turkey, Sweden, Portugal, and Spain.[21]

Anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was to be exterminated without exception. In other genocides, people were able to escape death by converting to another religion or in some other way assimilating. This option was not available to the Jews of occupied Europe,[22] unless their grandparents had converted before 18 January 1871. All persons of recent Jewish ancestry were to be exterminated in lands controlled by Germany.[23]

Extermination camps

The use of camps equipped with gas chambers for the purpose of systematic mass extermination of peoples was a unique feature of the Holocaust and unprecedented in history. Never before had there existed places with the express purpose of killing people en masse. These were established at Auschwitz, Belzec, Chełmno, Jasenovac, Majdanek, Maly Trostenets, Sobibór, and Treblinka.

Medical experiments

A distinctive feature of Nazi genocide was the extensive use of human subjects in "medical" experiments. According to Raul Hilberg, "German physicians were highly Nazified, compared to other professionals, in terms of party membership."[24] Some carried out experiments at Auschwitz, Dachau, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, and Natzweiler concentration camps.[25]

The most notorious of these physicians was Dr. Josef Mengele, who worked in Auschwitz. His experiments included placing subjects in pressure chambers, testing drugs on them, freezing them, attempting to change eye color by injecting chemicals into children's eyes, and various amputations and other surgeries.[25] The full extent of his work will never be known because the truckload of records he sent to Dr. Otmar von Verschuer at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute was destroyed by von Verschuer.[26] Subjects who survived Mengele's experiments were almost always killed and dissected shortly afterwards.

He worked extensively with Romani children. He would bring them sweets and toys, and personally take them to the gas chamber. They would call him "Onkel (Uncle) Mengele".[27] Vera Alexander was a Jewish inmate at Auschwitz who looked after 50 sets of Romani twins:

I remember one set of twins in particular: Guido and Ina, aged about four. One day, Mengele took them away. When they returned, they were in a terrible state: they had been sewn together, back to back, like Siamese twins. Their wounds were infected and oozing pus. They screamed day and night. Then their parents—I remember the mother's name was Stella—managed to get some morphine and they killed the children in order to end their suffering.[27]

Development and execution

Origins

"The whole problem of the Jews exists only in nation states, for here their energy and higher intelligence, their accumulated capital of spirit and will, gathered from generation to generation through a long schooling in suffering, must become so preponderant as to arouse mass envy and hatred. In almost all contemporary nations, therefore - in direct proportion to the degree to which they act up nationalistially - the literary obscenity of leading the Jews to slaughter as scapegoats of every conceivable public and internal misfortune is spreading."

—Friedrich Nietzsche, 1886, [MA 1 475][28]

Yehuda Bauer and Lucy Dawidowicz maintained that from the Middle Ages onward, German society and culture were suffused with antisemitism, and that there was a direct ideological link from medieval pogroms to the Nazi death camps.[29]

The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence in Germany and Austria-Hungary of the Völkisch movement, developed by such thinkers as Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement presented a pseudoscientific, biologically based racism that viewed Jews as a race locked in mortal combat with the Aryan race for world domination.[30] Völkisch antisemitism drew upon stereotypes from Christian antisemitism, but differed in that Jews were considered to be a race rather than a religion.[31]

In a speech before the Reichstag in 1895, völkisch leader Hermann Ahlwardt called Jews "predators" and "cholera bacilli" who should be "exterminated" for the good of the German people.[32] In his best-selling 1912 book Wenn ich der Kaiser wär (If I were the Kaiser), Heinrich Class, leader of the völkisch group Alldeutscher Verband, urged that all German Jews be stripped of their German citizenship and be reduced to Fremdenrecht (alien status).[33] Class also urged that Jews should be excluded from all aspects of German life, forbidden to own land, hold public office, or participate in journalism, banking, and the liberal professions.[33] Class defined a Jew as anyone who was a member of the Jewish religion on the day the German Empire was proclaimed in 1871, or anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent.[33]

The first medical experimentation on humans and ethnic cleansing by Germans took place in the death camps of German South-West Africa during the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. It has been suggested that this was an inspiration for the Holocaust.[34][35]

During the German Empire, völkisch notions and pseudoscientific racism had become common and accepted throughout Germany,[36] with the educated professional classes of the country, in particular, adopting an ideology of human inequality.[37] Though the völkisch parties were defeated in the 1912 Reichstag elections, being all but wiped out, antisemitism was incorporated into the platforms of the mainstream political parties.[36] The National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi Party; NSDAP) was founded in 1920 as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, and adopted their antisemitism.[38] In a 1986 essay, German historian Hans Mommsen wrote about the situation in post–World War I Germany that:

If one emphasizes the indisputably important connection in isolation, one should not then force a connection with Hitler's weltanschauung [worldview], which was in no ways original itself, in order to derive from it the existence of Auschwitz ... Thoughts about the extermination of the Jews had long been current, and not only for Hitler and his satraps. Many of these found their way to the NSDAP from the Deutschvölkisch Schutz-und Trutzbund [German Racial Union for Protection and Defiance], which itself had been called into life by the Pan-German Union.[39]

Tremendous scientific and technological changes in Germany during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, together with the growth of the welfare state, created widespread hopes that utopia was at hand and that soon all social problems could be solved.[40] At the same time a racist, social Darwinist, and eugenicist world-view which declared some people to be more biologically valuable than others was common.[41] Historian Detlev Peukert states that the Shoah did not result solely from antisemitism, but was a product of the "cumulative radicalization" in which "numerous smaller currents" fed into the "broad current" that led to genocide.[42] After the First World War, the pre-war mood of optimism gave way to disillusionment as German bureaucrats found social problems to be more insoluble than previously thought, which in turn led them to place increasing emphasis on saving the biologically "fit" while the biologically "unfit" were to be written off.[43]

The economic strains of the Great Depression led many in the German medical establishment to advocate the idea of euthanisation of the "incurable" mentally and physically disabled as a cost-saving measure to free up money to care for the curable.[45] By the time the Nazis came to power in 1933, a tendency already existed in German social policy to save the racially "valuable" while seeking to rid society of the racially "undesirable".[46]

Hitler was open about his hatred of Jews. In his book Mein Kampf, he gave warning of his intention to drive them from Germany's political, intellectual, and cultural life. He did not write that he would attempt to exterminate them, but he is reported to have been more explicit in private. As early as 1922, he allegedly told Major Joseph Hell, at the time a journalist:

Once I really am in power, my first and foremost task will be the annihilation of the Jews. As soon as I have the power to do so, I will have gallows built in rows—at the Marienplatz in Munich, for example—as many as traffic allows. Then the Jews will be hanged indiscriminately, and they will remain hanging until they stink; they will hang there as long as the principles of hygiene permit. As soon as they have been untied, the next batch will be strung up, and so on down the line, until the last Jew in Munich has been exterminated. Other cities will follow suit, precisely in this fashion, until all Germany has been completely cleansed of Jews.[47]

The German historian Hans Mommsen claimed that there were three types of antisemitism in Germany:

One should differentiate between the cultural antisemitism symptomatic of the German conservatives – found especially in the German officer corps and the high civil administration – and mainly directed against the Eastern Jews on the one hand, and völkisch antisemitism on the other. The conservative variety functions, as Shulamit Volkov has pointed out, as something of a "cultural code." This variety of German antisemitism later on played a significant role insofar as it prevented the functional elite from distancing itself from the repercussions of racial antisemitism. Thus, there was almost no relevant protest against the Jewish persecution on the part of the generals or the leading groups within the Reich government. This is especially true with respect to Hitler's proclamation of the "racial annihilation war" against the Soviet Union.

Besides conservative antisemitism, there existed in Germany a rather silent anti-Judaism within the Catholic Church, which had a certain impact on immunising the Catholic population against the escalating persecution. The famous protest of the Catholic Church against the euthanasia program was, therefore, not accompanied by any protest against the Holocaust.

The third and most vitriolic variety of antisemitism in Germany (and elsewhere) is the so-called völkisch antisemitism or racism, and this is the foremost advocate of using violence. Anyhow, one has to be aware that even Hitler until 1938 and possibly 1939 still relied on enforced emigration to get rid of German Jewry; and there did not yet exist any clear-cut concept of killing them. This, however, does not mean that the Nazis elsewhere on all levels did not hesitate to use violent methods, and the inroads against Jews, Jewish shops, and institutions show that very clearly. But there did not exist any formal annihilation program until the second year of the war. It came into being after the "reservation" projects had failed. That, however, does not mean that those methods did not include a lethal component.[48]

Legal repression and emigration

Right from the establishment of the Third Reich, Nazi leaders proclaimed the existence of a Volksgemeinschaft ("people's community"). Nazi policies divided the population into two categories, the Volksgenossen ("national comrades"), who belonged to the Volksgemeinschaft, and the Gemeinschaftsfremde ("community aliens"), who did not. Nazi policies about repression divided people into three types of enemies, the "racial" enemies such as the Jews and the Gypsies who were viewed as enemies because of their "blood"; political opponents such as Marxists, liberals, Christians and the "reactionaries" who were viewed as wayward "National Comrades"; and moral opponents such as homosexuals, the "work-shy" and habitual criminals, also seen as wayward "National Comrades".[49] The last two groups were to be sent to concentration camps for "re-education", with the aim of eventual absorption into the Volksgemeinschaft, though some of the moral opponents were to be sterilized, as they were regarded as "genetically inferior".[49]

"Racial" enemies such as the Jews could, by definition, never belong to the Volksgemeinschaft; they were to be totally removed from society.[49] German historian Detlev Peukert wrote that the National Socialists' "goal was an utopian Volksgemeinschaft, totally under police surveillance, in which any attempt at nonconformist behaviour, or even any hint or intention of such behaviour, would be visited with terror".[50] Peukert quotes policy documents on the "Treatment of Community Aliens" from 1944, which (though never implemented) showed the full intentions of Nazi social policy: "persons who ... show themselves [to be] unable to comply by their own efforts with the minimum requirements of the national community" were to be placed under police supervision, and if this did not reform them, they were to be taken to a concentration camp.[51]

Leading up to the March 1933 Reichstag elections, the Nazis intensified their campaign of violence against the opposition. With the co-operation of local authorities, they set up concentration camps for extrajudicial imprisonment of their opponents. One of the first, at Dachau, opened on 9 March 1933.[52] Initially the camp contained primarily communists and Social Democrats.[53] Other early prisons—for example, in basements and storehouses run by the Sturmabteilung (SA) and less commonly by the Schutzstaffel (SS)—were consolidated by mid-1934 into purpose-built camps outside the cities, run exclusively by the SS. The initial purpose of the camps was to serve as a deterrent by terrorizing those Germans who did not conform to the Volksgemeinschaft.[54] Those sent to the camps included the "educable", whose wills could be broken into becoming "National Comrades", and the "biologically depraved", who were to be sterilized, were to be held permanently, and over time were increasingly subject to extermination through labor, i.e., being worked to death.[54]

Throughout the 1930s, the legal, economic, and social rights of Jews were steadily restricted. The Israeli historian Saul Friedländer writes that, for the Nazis, Germany drew its strength "from the purity of its blood and from its rootedness in the sacred German earth."[55] On 1 April 1933, there occurred a boycott of Jewish businesses, which was the first national antisemitic campaign, initially planned for a week, but called off after one day owing to lack of popular support. In 1933, a series of laws were passed which contained Aryan paragraphs to exclude Jews from key areas: the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, the first antisemitic law passed in the Third Reich; the Physicians' Law; and the Farm Law, forbidding Jews from owning farms or taking part in agriculture.

Jewish lawyers were disbarred, and in Dresden, Jewish lawyers and judges were dragged out of their offices and courtrooms and beaten.[56] At the insistence of then president Paul von Hindenburg, Hitler added an exemption allowing Jewish civil servants who were veterans of the First World War, or whose fathers or sons had served, to remain in office. Hitler revoked this exemption in 1937. Jews were excluded from schools and universities (the Law to Prevent Overcrowding in Schools), from belonging to the Journalists' Association, and from being owners or editors of newspapers.[55] The Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung of 27 April 1933 wrote:

A self-respecting nation cannot, on a scale accepted up to now, leave its higher activities in the hands of people of racially foreign origin . . . Allowing the presence of too high a percentage of people of foreign origin in relation to their percentage in the general population could be interpreted as an acceptance of the superiority of other races, something decidedly to be rejected.[57]

In July 1933, the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring calling for compulsory sterilization of the "inferior" was passed. This major eugenic policy led to over 200 Hereditary Health Courts ([Erbgesundheitsgerichte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) being set up, under whose rulings over 400,000 people were sterilized against their will during the Nazi period.[58]

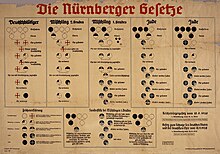

In 1935, Hitler introduced the Nuremberg Laws, which: prohibited "Aryans" from having sexual relations or marriages with Jews, although this was later extended to include "Gypsies, Negroes or their bastard offspring" (the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor),[59] stripped German Jews of their citizenship and deprived them of all civil rights. At the same time the Nazis used propaganda to promulgate the concept of Rassenschande (race defilement) to justify the need for a restrictive law.[60] Hitler described the "Blood Law" in particular "the attempt at a legal regulation of a problem, which in the event of further failure would then have through law to be transferred to the final solution of the National Socialist Party". Hitler said that if the "Jewish problem" cannot be solved by these laws, it "must then be handed over by law to the National-Socialist Party for a final solution".[61] The "final solution", or "Endlösung", became the standard Nazi euphemism for the extermination of the Jews. In January 1939, he said in a public speech: "If international-finance Jewry inside and outside Europe should succeed once more in plunging the nations into yet another world war, the consequences will not be the Bolshevization of the earth and thereby the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation (vernichtung) of the Jewish race in Europe".[62] Footage from this speech was used to conclude the 1940 Nazi propaganda movie The Eternal Jew (Der ewige Jude), whose purpose was to provide a rationale and blueprint for eliminating the Jews from Europe.[63]

Jewish intellectuals were among the first to leave. The philosopher Walter Benjamin left for Paris on 18 March 1933. Novelist Leon Feuchtwanger went to Switzerland. The conductor Bruno Walter fled after being told that the hall of the Berlin Philharmonic would be burned down if he conducted a concert there: the Frankfurter Zeitung explained on 6 April that Walter and fellow conductor Otto Klemperer had been forced to flee because the government was unable to protect them against the mood of the German public, which had been provoked by "Jewish artistic liquidators".[64] Albert Einstein was visiting the US on 30 January 1933. He returned to Ostende in Belgium, never to set foot in Germany again, and calling events there a "psychic illness of the masses"; he was expelled from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and the Prussian Academy of Sciences, and his citizenship was rescinded.[65] When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, Sigmund Freud and his family fled from Vienna to England. Saul Friedländer writes that when Max Liebermann, honorary president of the Prussian Academy of Arts, resigned his position, not one of his colleagues expressed a word of sympathy, and he was still ostracized at his death two years later. When the police arrived in 1943 with a stretcher to deport his 85-year-old bedridden widow, she committed suicide with an overdose of barbiturates rather than be taken.[65]

Kristallnacht (1938)

On 7 November 1938, Jewish minor Herschel Grünspan assassinated Nazi German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris.[66] This incident was used by the Nazis as a pretext to go beyond legal repression to large-scale physical violence against Jewish Germans. What the Nazis claimed to be spontaneous "public outrage" was in fact a wave of pogroms instigated by the Nazi Party, and carried out by SA members and affiliates throughout Nazi Germany, at the time consisting of Germany proper, Austria and Sudetenland.[66] These pogroms became known as Reichskristallnacht ("the Night of Broken Glass", literally "Crystal Night"), or November pogroms. Jews were attacked and Jewish property was vandalized, over 7,000 Jewish shops and more than 1,200 synagogues (roughly two-thirds of the synagogues in areas under German control) were damaged or destroyed.[67]

The death toll is assumed to be much higher than the official number of 91 dead.[66] 30,000 were sent to concentration camps, including Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Buchenwald, and Oranienburg,[68] where they were kept for several weeks, and released when they could either prove that they were about to emigrate in the near future, or transferred their property to the Nazis.[69] German Jewry was collectively made responsible for restitution of the material damage of the pogroms, amounting to several hundred thousand Reichsmarks, and furthermore had to pay an "atonement tax" of more than a billion Reichsmarks.[66] After these pogroms, Jewish emigration from Germany accelerated, while public Jewish life in Germany ceased to exist.[66]

Resettlement and deportation

Before the war, the Nazis considered mass deportation of German (and subsequently the European) Jewry from Europe. Hitler's agreement to the 1938–9 Schacht Plan, and the continued flight of thousands of Jews from Hitler's clutches for an extended period when the Schacht Plan came to nothing, indicate that the preference for a concerted genocide of the type that came later did not yet exist.[70]

Plans to reclaim former German colonies such as Tanganyika and South West Africa for Jewish resettlement were halted by Hitler, who argued that no place where "so much blood of heroic Germans had been spilled" should be made available as a residence for the "worst enemies of the Germans".[71] Diplomatic efforts were undertaken to convince the other colonial powers, primarily the United Kingdom and France, to accept expelled Jews in their colonies.[72] Areas considered for possible resettlement included British Palestine,[73] Italian Abyssinia,[73] British Rhodesia,[74] French Madagascar,[73] and Australia.[75]

Of these areas, Madagascar was the most seriously discussed. Heydrich called the Madagascar Plan a "territorial final solution"; it was a remote location, and the island's unfavorable conditions would hasten deaths.[76] Approved by Hitler in 1938, the resettlement planning was carried out by Adolf Eichmann's office, only being abandoned once the mass killing of Jews had begun in 1941. In retrospect, although futile, this plan did constitute an important psychological step on the path to the Holocaust.[77] The end of the Madagascar Plan was announced on 10 February 1942. The German Foreign Office was given the official explanation that, due to the war with the Soviet Union, Jews were to be "sent to the east".[78]

Nazi bureaucrats also developed plans to deport Europe's Jews to Siberia.[79] Palestine was the only location to which any Nazi relocation plan succeeded in producing significant results, by means of an agreement begun in 1933 between the Zionist Federation of Germany (die Zionistische Vereinigung für Deutschland) and the Nazi government, the Haavara Agreement. This agreement resulted in the transfer of about 60,000 German Jews and $100 million from Germany to Palestine, up until the outbreak of World War II.[80]

Early measures

In German-occupied Poland

Germany's invasion of Poland in September 1939 increased the urgency of the "Jewish Question". Poland, was home to approximately three million Jews (nearly nine percent of the population), in centuries-old communities, two-thirds of whom fell under Nazi control with Poland's capitulation.

Reinhard Heydrich, Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, recommended concentrating all the Polish Jews in ghettos in major cities, where they would be put to work for the German war industry. The ghettos would be in cities located on railway junctions in order to furnish, in Heydrich's words, "a better possibility of control and later deportation."[81] During his interrogation in 1961, Adolf Eichmann recalled that this "later deportation" actually meant "physical extermination."[82]

I ask nothing of the Jews except that they should disappear.

— Hans Frank, Nazi governor for occupied Poland.[83]

In September, Himmler appointed Heydrich head of the Reich Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA, not to be confused with the RuSHA). This organization was made up of seven departments, including the Security Police (SD), and the Gestapo.[84] They were to oversee the work of the SS in occupied Poland, and carry out the policy towards the Jews described in Heydrich's report. The first organized murders of Jews by German forces occurred during Operation Tannenberg and through Selbstschutz units. The Jews were later herded into ghettos, mostly in the General Government area of central Poland, where they were put to work under the Reich Labor Office headed by Fritz Sauckel. Here many thousands died from maltreatment, disease, starvation, and exhaustion, but there was still no program of systematic killing. There is little doubt, however, that the Nazis saw forced labor as a form of extermination. The expression Vernichtung durch Arbeit ("destruction through work") was frequently used.

Although it was clear by late 1941 that the SS hierarchy was determined to embark on a policy of killing all the Jews under German control, there was still opposition to this policy within the Nazi regime, although the motive was economic, not humanitarian. Hermann Göring, who had overall control of the German war industry, and the German army's Economics Department, argued that the enormous Jewish labor force assembled in the General Government area (more than a million able-bodied workers), was an asset too valuable to waste, particularly with Germany failing to secure rapid victory of the Soviet Union.

In other occupied countries

When Germany occupied Norway, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France in 1940, and Yugoslavia and Greece in 1941, antisemitic measures were also introduced into these countries, although the pace and severity varied greatly from country to country according to local political circumstances. Jews were removed from economic and cultural life and were subject to various restrictive laws, but physical deportation did not occur in most places before 1942. The Vichy regime in occupied France actively collaborated in persecuting French Jews. Germany's allies Italy, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Finland were pressured to introduce antisemitic measures, but for the most part they did not comply until compelled to do so. During the course of the war some 900 Jews and 300 Roma passed through the Banjica concentration camp in Belgrade, intended primarily for Serbian communists, royalists and others who resisted occupation. The German puppet regime in Croatia, on the other hand, began actively persecuting Jews on its own initiative, so the Legal Decree on the Nationalization of the Property of Jews and Jewish Companies was declared on 10 October 1941 in the Independent State of Croatia.

In North Africa

Though the vast majority of the Jews affected and killed during Holocaust were of Ashkenazi descent, Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews suffered greatly as well.

In the 1930s, the Fascist Italian regime initiated anti-Semitic laws which barred Jews from government jobs, government schools and required them to stamp "Jewish race" into their passports.[85] However, this was not enough to deter Jews from Libya, as 25% of the population in Tripoli was Jewish with over 44 synagogues in existence.[86] In 1942, the Jewish Quarter of Benghazi was occupied by the Nazis and more than 2,000 Jews were deported and sent to Nazi labor camps. By the end of WWII, about one-fifth of those who were sent away had perished.[87] Several forced labor camps for Jews were established in Libya, the largest of which, the Giado camp, held almost 2,600 inmates, of whom 562 died of weakness, hunger, and disease. Smaller labor camps were established in Gharyan, Jeren, and Tigrinna.[87][88]

Tunisia, the only North African country to come under direct Nazi occupation, had 100,000 Jews when the Nazis arrived in November 1942. During their six months of occupation, the Nazis imposed anti-Semitic policies in Tunisia, including forcing Jews to wear the Yellow Star, fines, and confiscation of property. Some 5,000 Tunisian Jews were subjected to forced labor, and some were deported to European death camps.[89] More than 2,500 Tunisian Jews died in slave labor camps during the German occupation.[90]

General Government and Lublin reservation (Nisko plan)

On 28 September 1939, Germany gained control over the Lublin area through the German-Soviet agreement in exchange for Lithuania.[91] According to the Nisko Plan, they set up the Lublin-Lipowa Reservation in the area. The reservation was designated by Adolf Eichmann, who was assigned the task of removing all Jews from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[92] They shipped the first Jews to Lublin less than three weeks later on 18 October 1939. The first train loads consisted of Jews deported from Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[93] By 30 January 1940, a total of 78,000 Jews had been deported to Lublin from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia.[94] On 12 and 13 February 1940, the Pomeranian Jews were deported to the Lublin reservation, resulting in Pomeranian Gauleiter Franz Schwede-Coburg to be the first to declare his Gau (country subdivision) judenrein ("free of Jews").[95] On 24 March 1940 Göring put the Nisko Plan on hold, and abandoned it entirely by the end of April.[96] By the time the Nisko Plan was stopped, the total number of Jews who had been transported to Nisko had reached 95,000, many of whom had died from starvation.[97]

In July 1940, due to the difficulties of supporting the increased population in the General Government, Hitler had the deportations temporarily halted.[98]

In October 1940, Gauleiters Josef Bürckel and Robert Heinrich Wagner oversaw Operation Bürckel, the expulsion of the Jews into unoccupied France from their Gaues and the parts of Alsace-Lorraine that had been annexed that summer to the Reich.[99] Only those Jews in mixed marriages were not expelled.[99] The 6,500 Jews affected by Operation Bürckel were given at most two hours warning on the night of 22–23 October 1940, before being rounded up. The nine trains carrying the deported Jews crossed over into France "without any warning to the French authorities", who were not happy with receiving them.[99] The deportees had not been allowed to take any of their possessions with them, these being confiscated by the German authorities.[99] The German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop treated the ensuing complaints by the Vichy government over the expulsions in a "most dilatory fashion".[99] As a result, the Jews expelled in Operation Bürckel were interned in harsh conditions by the Vichy authorities at the camps in Gurs, Rivesaltes and Les Milles while awaiting a chance to return them to Germany.[99]

During 1940 and 1941, the murder of large numbers of Jews in German-occupied Poland continued, and the deportation of Jews to the General Government was undertaken. The deportation of Jews from Germany, particularly Berlin, was not officially completed until 1943. (Many Berlin Jews were able to survive in hiding.) By December 1939, 3.5 million Jews were crowded into the General Government area.

Concentration and labor camps (1933–1945)

From the beginning of the Third Reich concentration camps were founded, initially as places of incarceration. Although the death rate in the concentration camps was high, with a mortality rate of 50%, they were not designed to be killing centers. (By 1942, six large extermination camps had been established in Nazi-occupied Poland, which were built solely for mass killings.) After 1939, the camps increasingly became places where Jews and POWs were either killed or made to work as slave laborers, undernourished and tortured.[100] It is estimated that the Germans established 15,000 camps and subcamps in the occupied countries, mostly in eastern Europe.[101][102] New camps were founded in areas with large Jewish, Polish intelligentsia, communist, or Roma and Sinti populations, including inside Germany. The transportation of prisoners was often carried out under horrifying conditions using rail freight cars, in which many died before reaching their destination.

Extermination through labor was a policy of systematic extermination – camp inmates would literally be worked to death, or worked to physical exhaustion, when they would be gassed or shot.[103] Slave labour was used in war production, for example producing V-2 rockets at Mittelbau-Dora, and various armaments around the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp complex.

Upon admission, some camps tattooed prisoners with a prisoner ID.[104] Those fit for work were dispatched for 12 to 14-hour shifts. Before and after, there were roll calls that could sometimes last for hours, with prisoners regularly dying of exposure.[105]

Ghettos (1940–1945)

After the invasion of Poland, the Nazis established ghettos in the incorporated territories and General Government in which Jews were confined. These were initially seen as temporary, until the Jews were deported out of Europe; as it turned out, such deportation never took place, with the ghettos' inhabitants instead being sent to extermination camps. The Germans ordered that each ghetto be run by a Judenrat (Jewish council) consisting of Jewish community leaders, with the first order for the establishment of such councils contained in a letter dated 29 September 1939 from Heydrich to the heads of the Einsatzgruppen.[106] The ghettos were formed and closed off from the outside world at different times and for different reasons.[107] The councils were responsible for the day-to-day running of the ghetto, including the distribution of food, water, heat, medicine, and shelter. The Germans also mandated them to undertake confiscations, organize forced labor, and, finally, facilitate deportations to extermination camps.[108] The councils' basic strategy was one of trying to minimise losses, largely by cooperating with Nazi authorities (or their surrogates), accepting the increasingly terrible treatment, bribery, and petitioning for better conditions and clemency.[109] Overall, to try and mitigate still worse cruelty and death, "the councils offered words, money, labor, and finally lives."[110]

The ultimate test of each Judenrat was the demand to compile lists of names of deportees to be murdered. Though the predominant pattern was compliance with even this final task,[111] some council leaders insisted that not a single individual should be handed over who had not committed a capital crime. Leaders such as Joseph Parnas in Lviv, who refused to compile a list, were shot. On 14 October 1942, the entire council of Byaroza committed suicide rather than cooperate with the deportations.[112] Adam Czerniaków in Warsaw killed himself on 23 July 1942 when he could take no more as the final liquidation of the ghetto got under way.[113] Others, like Chaim Rumkowski, who became the "dedicated autocrat" of Łódź,[114] argued that their responsibility was to save the Jews who could be saved, and that therefore others had to be sacrificed.

The importance of the councils in facilitating the persecution and murder of ghetto inhabitants was not lost on the Germans: one official was emphatic that "the authority of the Jewish council be upheld and strengthened under all circumstances",[115] another that "Jews who disobey instructions of the Jewish council are to be treated as saboteurs."[116] When such cooperation crumbled, as happened in the Warsaw ghetto after the Jewish Combat Organisation displaced the council's authority, the Germans lost control.[117]

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest, with 380,000 people; the Łódź Ghetto was second, holding 160,000. They were, in effect, immensely crowded prisons, described by Michael Berenbaum as instruments of "slow, passive murder."[118] Though the Warsaw Ghetto contained 30% of the population of the Polish capital, it occupied only 2.4% of the city's area, averaging 9.2 people per room.[119]

Between 1940 and 1942, starvation and disease, especially typhoid, killed hundreds of thousands. Over 43,000 residents of the Warsaw ghetto died there in 1941,[119] more than one in ten; in Theresienstadt, more than half the residents died in 1942.[118]

The Germans came, the police, and they started banging houses: "Raus, raus, raus, Juden raus." ... [O]ne baby started to cry ... The other baby started crying. So the mother urinated in her hand and gave the baby a drink to keep quiet ... [When the police had gone], I told the mothers to come out. And one baby was dead ... from fear, the mother [had] choked her own baby.

— Abraham Malik, describing his experience in the Kovno Ghetto[120]

Himmler ordered the start of the deportations on 19 July 1942, and three days later, on 22 July, the deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto began; over the next 52 days, until 12 September 300,000 people from Warsaw alone were transported in freight trains to the Treblinka extermination camp. Many other ghettos were completely depopulated.

The first ghetto uprising occurred in September 1942 in the small town of Łachwa in south-east Poland. Although there were armed resistance attempts in the larger ghettos in 1943, such as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Białystok Ghetto Uprising, in every case they failed against the overwhelming Nazi military force, and the remaining Jews were either killed or deported to the death camps.[121]

Pogroms (1939–1942)

A number of deadly pogroms by local populations occurred during the Second World War, some with Nazi encouragement, and some spontaneously. This included the Iaşi pogrom in Romania on 30 June 1941, in which as many as 14,000 Jews were killed by Romanian residents and police, and the Jedwabne pogrom of July 1941, in which 300 Jews were locked in a barn set on fire by the local Poles in the presence of Nazi Ordnungspolizei, which was preceded by the execution of 40 Jewish men at the same location by the Germans. – Such were the final finding of the official investigation conducted in 2000–2003 by the Institute of National Remembrance, confirmed by the number of victims in the two graves examined by the archeological and anthropological team participating in the exhumation. Earlier higher estimates based on hearsay were disproved.[122][123][124][125][126]

Death squads (1941–1943)

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 opened a new phase. The Holocaust intensified after the Nazis occupied Lithuania, where close to 80% of the country's 220,000 Jews were exterminated before the end of the year.[127] The Soviet territories occupied by early 1942, including all of Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Moldova and most Russian territory west of the line Leningrad-Moscow-Rostov, contained about three million Jews at the start of the war. Hundreds of thousands had fled Poland in 1939.

Members of the local populations in certain occupied Soviet territories participated actively in the killings of Jews and others.[128] Ultimately it was the Germans who organized and channelled these local participants in the Holocaust.[128] In Lithuania, Latvia and western Ukraine; locals were deeply involved in the murder of Jews from the very beginning of the German occupation.[128] The Latvian Arajs Kommando was an example of an auxiliary unit involved in these killings.[128] In addition, Latvian and Lithuanian units left their own countries, and committed the murders of Jews in Belarus. To the south, Ukrainians killed approximately 24,000 Jews.[128] Ukrainians went to Poland, where they served as concentration and death camp guards.[128] Ustaše militia in Croatian areas also carried out acts of persecution and murder.

Many of the mass killings were carried out in public, a change from previous practice.[128] German witnesses to these killings emphasized the participation of the locals.[128]

Germany usually justified the massacres committed by the Einsatzgruppen on the grounds of anti-partisan or anti-bandit operations, but the German historian Andreas Hillgruber wrote that this was merely an excuse for the German Army's considerable involvement in the Holocaust in Russia. He wrote in 1989 that the terms "war crimes" and "crimes against humanity" were indeed correct labels for what happened.[129] Hillgruber maintained that the slaughter of about 2.2 million defenseless men, women and children for the reasons of racist ideology cannot possibly be justified for any reason, and that those German generals who claimed that the Einsatzgruppen were a necessary anti-partisan response were lying.[130]

Army co-operation with the SS in anti-partisan and anti-Jewish operations was close and intensive.[131] In mid-1941, the SS Cavalry Brigade commanded by Hermann Fegelein, during the course of "anti-partisan" operations in the Pripyat Marshes, killed 699 Red Army soldiers, 1,100 partisans and 14,178 Jews.[131] Before the operation, Fegelein had been ordered to shoot all adult Jews while driving the women and children into the marshes. After the operation, General Max von Schenckendorff, who commanded the rear areas of Army Group Center, ordered on 10 August 1941 that all Wehrmacht security divisions when on anti-partisan duty should emulate Fegelein's example, and organized between 24–26 September 1941 in Mogilev a joint SS-Wehrmacht seminar on how best to kill Jews.[131] The seminar ended with the 7th Company of Police Battalion 322 shooting 32 Jews at a village called Knjashizy before the assembled officers, as an example of how to "screen" the population for partisans.[132]

As the war diary of the Battalion 322 read:

The action, first scheduled as a training exercise, was carried out under real-life conditions (ernstfallmässig) in the village itself. Strangers, especially partisans could not be found. The screening of the population, however resulted in 13 Jews, 27 Jewish women and 11 Jewish children, of which 13 Jews and 19 Jewish women were shot in co-operation with the Security Service[132]

Based on what they had learned during the Mogilev seminar, one Wehrmacht officer told his men, "Where the partisan is, there is the Jew and where the Jew is, there is the partisan".[132]

In Order No. 24 24 November 1941, the commander of the 707th division declared:

Jews and Gypsies:...As already has been ordered, the Jews have to vanish from the flat country and the Gypsies have to be annihilated too. The carrying out of larger Jewish actions is not the task of the divisional units. They are carried out by civilian or police authorities, if necessary ordered by the commandant of White Ruthenia, if he has special units at his disposal, or for security reasons and in the case of collective punishments. When smaller or larger groups of Jews are met in the flat country, they can be liquidated by divisional units or be massed in the ghettos near bigger villages designated for that purpose, where they can be handed over to the civilian authority or the SD.[133]

The German historian Jürgen Förster, a leading expert on the subject of Wehrmacht war crimes argued that they (the Wehrmacht) played a key role in the Holocaust. He said it is wrong to describe the Shoah as solely the work of the SS with the Wehrmacht as a passive and disapproving bystander.[134]

Raul Hilberg writes that the German Einsatzgruppen commanders were ordinary citizens: the great majority were professionals, most were intellectuals, and they brought to bear all their skills and training in becoming efficient killers.[135]

The large-scale killings of Jews in the occupied Soviet territories was assigned to SS formations called Einsatzgruppen ("task groups"), under the overall command of Heydrich. These had been used to a limited extent in Poland in 1939, but were organized in the Soviet territories on a much larger scale. Einsatzgruppe A was assigned to the Baltic area, Einsatzgruppe B to Belarus, Einsatzgruppe C to north and central Ukraine, and Einsatzgruppe D to Moldova, south Ukraine, Crimea, and, during 1942, the north Caucasus.[136]

According to Otto Ohlendorf at his trial, "the Einsatzgruppen had the mission to protect the rear of the troops by killing the Jews, Gypsies, Communist functionaries, active Communists, and all persons who would endanger the security." In practice, their victims were nearly all defenseless Jewish civilians (not a single Einsatzgruppe member was killed in action during these operations). By December 1941, the four Einsatzgruppen listed above had killed, respectively, 125,000, 45,000, 75,000, and 55,000 people—a total of 300,000 people—mainly by shooting or with hand grenades at mass killing sites outside the major towns.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum provides the account of one survivor of the Einsatzgruppen in Piryatin, Ukraine, when the Germans killed 1,600 Jews on 6 April 1942, the second day of Passover:

I saw them do the killing. At 5:00 pm they gave the command, "Fill in the pits." Screams and groans were coming from the pits. Suddenly I saw my neighbor Ruderman rise from under the soil ... His eyes were bloody and he was screaming: "Finish me off!" ... A murdered woman lay at my feet. A boy of five years crawled out from under her body and began to scream desperately. "Mommy!" That was all I saw, since I fell unconscious.[137]

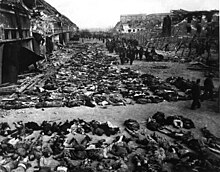

The most notorious massacre of Jews in the Soviet Union was at a ravine called Babi Yar outside Kiev, where 33,771 Jews were killed in a single operation on 29–30 September 1941.[138] The decision to kill all the Jews in Kiev was made by the military governor (Major-General Friedrich Eberhardt), the Police Commander for Army Group South (SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Jeckeln), and the Einsatzgruppe C Commander Otto Rasch. A mixture of SS, SD and Security Police, assisted by Ukrainian police, carried out the killings. Although they did not participate in the killings, men of the 6th Army played a key role in rounding up the Jews of Kiev and transporting them to be shot at Babi Yar.[139]

On Monday, the Jews of Kiev as ordered gathered by the cemetery, expecting to be loaded onto trains. The crowd was large enough that most of the men, women, and children could not have known what was happening until it was too late; by the time they heard the machine gun fire, there was no chance to escape. All were driven down a corridor of soldiers, in groups of ten, and then shot. A truck driver described the scene, as:

one after the other, they had to remove their luggage, then their coats, shoes, and outer garments and also underwear ... Once undressed, they were led into the ravine which was about 150 meters long and 30 meters wide and a good 15 meters deep ... When they reached the bottom of the ravine they were seized by members of the Schutzpolizei and made to lie down on top of Jews who had already been shot ... The corpses were literally in layers. A police marksman came along and shot each Jew in the neck with a submachine gun ... I saw these marksmen stand on layers of corpses and shoot one after the other ... The marksman would walk across the bodies of the executed Jews to the next Jew, who had meanwhile lain down, and shoot him.[140]

In August 1941 Himmler travelled to Minsk, where he personally witnessed 100 Jews being shot in a ditch outside the town, an event described by Karl Wolff in his diary: "Himmler's face was green. He took out his handkerchief and wiped his cheek where a piece of brain had squirted up onto it. Then he vomited." After recovering his composure, Himmler lectured the SS men on the need to follow the "highest moral law of the Party" in carrying out their tasks.[142]

New methods of mass murder

Starting in December 1939, the Nazis introduced new methods of mass murder by using gas.[143] First, experimental gas vans equipped with gas cylinders and a sealed trunk compartment, were used to kill mental care clients of sanatoria in Pomerania, East Prussia, and occupied Poland, as part of an operation termed Action T4.[143] In the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, larger vans holding up to 100 people were used from November 1941, using the engine's exhaust rather than a cylinder.[143] These vans were introduced to the Chełmno extermination camp in December 1941, and another 15 of them were used by the Einsatzgruppen in the occupied Soviet Union.[143] These gas vans were developed and run under supervision of the SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Main Security Office), and were used to kill about 500,000 people, primarily Jews, but also Romani and others.[143] The vans were carefully monitored and after a month of observation a report stated that "ninety seven thousand have been processed using three vans, without any defects showing up in the machines".[144]

A need for new mass murder techniques was also expressed by Hans Frank, governor of the General Government, who noted that this many people could not be simply shot. "We shall have to take steps, however, designed in some way to eliminate them." It was this problem which led the SS to experiment with large-scale killings using poison gas. Christian Wirth seems to have been the inventor of the gas chamber.

Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution (1942–1945)

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Wannsee Conference was convened by Reinhard Heydrich on 20 January 1942 in the Berlin suburb of Wannsee and brought together some 15 Nazi leaders which included a number of state secretaries, senior officials, party leaders, SS officers and other leaders of government departments who were responsible for policies which were linked to Jewish issues. The initial purpose of the meeting was to discuss plans for a comprehensive solution to the "Jewish question in Europe." Heydrich intended to "outline the mass murders in the various occupied territories . . . as part of a solution to the European Jewish question ordered by Hitler . . . to ensure that they, and especially the ministerial bureaucracy, would share both knowledge and responsibility for this policy"[148]

A copy of the minutes which were drawn up by Eichmann has survived, but on Heydrich's instructions, they were written up in "euphemistic language." Thus the exact words used at the meeting are not known.[149] However, Heydrich addressed the meeting indicating the policy of emigration was superseded by a policy of evacuating Jews to the east. This was seen to be only a temporary solution leading up to a final solution which would involve some 11 million Jews living not only in territories controlled then by the Germans, but to major countries in the rest of the world including the UK, and the US.[150] There was little doubt what the solution was: "Heydrich also made it clear what was understood by the phrase 'Final Solution': the Jews were to be annihilated by a combination of forced labour and mass murder."[151]

The officials were told there were 2.3 million Jews in the General Government, 850,000 in Hungary, 1.1 million in the other occupied countries, and up to five million in the USSR, although two million of these were in areas still under Soviet control – a total of about 6.5 million. These would all be transported by train to extermination camps (Vernichtungslager) in Poland, where almost all of them would be gassed at once. In some camps, such as Auschwitz, those fit for work would be kept alive for a while, but eventually all would be killed. Göring's representative, Dr. Erich Neumann, gained a limited exemption for some classes of industrial workers.[152]

Reaction

German public

In his 1983 book, Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich, Ian Kershaw examined the Alltagsgeschichte (history of everyday life) in Bavaria during the Nazi period.[153] Describing the attitudes of most Bavarians, Kershaw argued that the most common viewpoint was indifference towards what was happening to the Jews.[154] Kershaw argued that most Bavarians were vaguely aware of the Shoah, but were vastly more concerned about the war than about the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question".[154] Kershaw made the analogy that "the road to Auschwitz was built by hate, but paved with indifference".[155]

Kershaw's assessment that most Bavarians, and by implication most Germans, were indifferent to the Shoah faced criticism from the Israeli historian Otto Dov Kulka, an expert on public opinion in Nazi Germany, and the Canadian historian Michael Kater. Kater maintained that Kershaw downplayed the extent of popular antisemitism, and that though admitting that most of the "spontaneous" antisemitic actions of Nazi Germany were staged, argued that because these actions involved substantial numbers of Germans, it is wrong to see the extreme antisemitism of the Nazis as coming solely from above.[156] Kulka argued that most Germans were more antisemitic than Kershaw portrayed them in Popular Opinion and Political Dissent, and that rather than "indifference", "passive complicity" would be a better term to describe the reaction of the German people.[157]

In a study focusing only on the views about Jews or Germans opposed to the Nazi regime, the German historian Christof Dipper in his 1983 essay "Der Deutsche Widerstand und die Juden" (translated into English as "The German Resistance and the Jews" in Yad Vashem Studies, Volume 16, 1984) argued that the majority of the anti-Nazi national-conservatives were antisemitic.[156] Dipper wrote that for the majority of the national-conservatives "the bureaucratic, pseudo-legal deprivation of the Jews practiced until 1938 was still considered acceptable".[156] Though Dipper noted no one in the German resistance supported the Holocaust, he also commented that the national-conservatives did not intend to restore civil rights to the Jews after the planned overthrow of Hitler.[156] Dipper went on to argue that, based on such views held by opponents of the regime, "a large part of the German people ... believed that a "Jewish Question" existed and had to be solved ...".[156]

A study conducted in 2012 established that in Berlin alone there were 3,000 camps of various functions, another 1,300 were in Hamburg and its co-researcher concluded that it is unlikely that the German population could avoid knowing about the persecution considering such prevalence.[7] Robert Gellately has argued that the German civilian population were, by and large, aware of what was happening. According to Gellately, the government openly announced the conspiracy through the media and civilians were aware of its every aspect except for the use of gas chambers.[158] In contrast, some historical evidence indicates that the vast majority of Holocaust victims, prior to their deportation to concentration camps, were either unaware of the fate that awaited them or were in denial; they honestly believed that they were to be resettled.[159]

International

Motivation

In his 1965 essay "Command and Compliance", which originated in his work as an expert witness for the prosecution at the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials, the German historian Hans Buchheim wrote there was no coercion to murder Jews and others, and all who committed such actions did so out of free will.[160] Buchheim wrote that chances to avoid executing criminal orders "...were both more numerous and more real than those concerned are generally prepared to admit...",[160] and that he found no evidence that SS men who refused to carry out criminal orders were sent to concentration camps or executed.[161] Moreover, SS rules prohibited acts of gratuitous sadism, as Himmler wished for his men to remain "decent", and that acts of sadism were taken on the individual initiative of those who were either especially cruel or who wished to prove themselves ardent National Socialists.[160] Finally, he argued that those of a non-criminal bent who committed crimes did so because they wished to conform to the values of the group they had joined and were afraid of being branded "weak" by their colleagues if they refused.[162]

In his 1992 monograph Ordinary Men, the Holocaust historian Christopher Browning examined the deeds of German Reserve Police Battalion 101 of the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police), used to commit massacres and round-ups of Jews as well as mass deportations to the Nazi death camps. The members of the battalion were middle-aged men of working-class background from Hamburg, who were too old for regular military duty. They were given no special training for genocide and at first, the commander gave his men the choice of opting out of direct participation in murder if they found it too unpleasant (even by being part of a passive cordon round the area of the killing). The majority chose not to exercise that option; fewer than 12 men, out of a battalion of 500 did so. Influenced by postwar Milgram experiment on obedience, Browning argued that the men of the battalion killed out of peer pressure, not blood-lust.[163]

The Russian historian Sergei Kudryashov studied the guards trained at the Trawniki SS camp division ("Trawniki men"), who provided the bulk of personnel for the Operation Reinhard death camps and performed massacres for Battalion 101. Most of them were former Red Army soldiers who volunteered to join the SS in order to get out of the POW camps.[164] Christopher R. Browning wrote that Hiwis "were screened on the basis of their anti-Communist (and hence almost invariably anti-Semitic) sentiments."[165] The majority of the "volunteers" were from Ukraine, Latvia and Lithuania (Hilfswillige, or Hiwis).[165] Kudryashov claimed that he found little sign of antisemitism or any attraction to National Socialism among the Trawniki men (not confirmed by Browning),[165] many of whom prior to their capture had been Communists according to Kudryashov.[166] Despite the generally apathetic views of the Trawniki guards, the vast majority faithfully carried out the SS's expectations of how to mistreat Jews; the mistreatment of Jews by the Trawniki guards was "systematic and without any particular cause".[166] Many, though not all of the Trawniki men executed Jews, and almost all of them while working as guards in the Operation Reinhard camps personally killed dozens of Jews.[167] Following Christopher Browning, Kudryashov argued that the Trawniki men were examples of ordinary people becoming willing killers.[168]

The "Trawniki men" (German: Trawnikimänner) were deployed in all major killing sites of the "Final Solution" – it was their primary purpose of training. They took an active role in the executions of Jews at Belzec, Sobibór, Treblinka II, Warsaw (three times), Częstochowa, Lublin, Lvov, Radom, Kraków, Białystok (twice), Majdanek as well as Auschwitz, not to mention Trawniki itself.[165][169]

Extermination camps

| Camp name | Killed | Coordinates | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auschwitz II | 1,000,000 | 50°2′9″N 19°10′42″E / 50.03583°N 19.17833°E | [171][172][173] |

| Belzec | 600,000 | 50°22′18″N 23°27′27″E / 50.37167°N 23.45750°E | [174][175] |

| Chełmno | 320,000 | 52°9′27″N 18°43′43″E / 52.15750°N 18.72861°E | [176][177] |

| Jasenovac | 58–97,000 | 45°16′54″N 16°56′6″E / 45.28167°N 16.93500°E | [178][179] |

| Majdanek | 360,000 | 51°13′13″N 22°36′0″E / 51.22028°N 22.60000°E | [180][181] |

| Maly Trostinets | 65,000 | 53°51′4″N 27°42′17″E / 53.85111°N 27.70472°E | [182][183] |

| Sobibór | 250,000 | 51°26′50″N 23°35′37″E / 51.44722°N 23.59361°E | [184][185] |

| Treblinka | 870,000 | 52°37′35″N 22°2′49″E / 52.62639°N 22.04694°E | [186][187] |

During 1942, in addition to Auschwitz, five other camps were designated as extermination camps (Vernichtungslager) for the carrying out of the Reinhard plan.[188][189] Two of these, Chełmno[190] and Majdanek, were already functioning as, respectively, a labor camp and a POW camp: these now had extermination facilities added to them. Three new camps were built for the sole purpose of killing large numbers of Jews as quickly as possible, at Belzec, Sobibór and Treblinka. A seventh camp, at Maly Trostinets in Belarus, was also used for this purpose. Jasenovac was an extermination camp where mostly ethnic Serbs were killed.

Extermination camps are frequently confused with concentration camps such as Dachau and Belsen, which were mostly located in Germany and intended as places of incarceration and forced labor for a variety of enemies of the Nazi regime (such as Communists and homosexuals). They should also be distinguished from slave labor camps, which were set up in all German-occupied countries to exploit the labor of prisoners of various kinds, including prisoners of war. In all Nazi camps there were very high death rates as a result of starvation, disease and exhaustion, but only the extermination camps were designed specifically for mass killing.

There was a place called the ramp where the trains with the Jews were coming in. They were coming in day and night, and sometimes one per day and sometimes five per day . . . Constantly, people from the heart of Europe were disappearing, and they were arriving to the same place with the same ignorance of the fate of the previous transport. And the people in this mass . . . I knew that within a couple of hours . . . ninety percent would be gassed.

The extermination camps were run by SS officers, but most of the guards were Ukrainian or Baltic auxiliaries.[citation needed]

Gas chambers

At the extermination camps with gas chambers all the prisoners arrived by train. Sometimes entire trainloads were sent straight to the gas chambers, but usually the camp doctor on duty subjected individuals to selections, where a small percentage were deemed fit to work in the slave labor camps; the majority were taken directly from the platforms to a reception area where all their clothes and other possessions were seized by the Nazis to help fund the war. They were then herded naked into the gas chambers. Usually they were told these were showers or delousing chambers, and there were signs outside saying "baths" and "sauna." They were sometimes given a small piece of soap and a towel so as to avoid panic, and were told to remember where they had put their belongings for the same reason. When they asked for water because they were thirsty after the long journey in the cattle trains, they were told to hurry up, because coffee was waiting for them in the camp, and it was getting cold.[191]

According to Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, bunker 1 held 800 people, and bunker 2 held 1,200.[192] Once the chamber was full, the doors were screwed shut and solid pellets of Zyklon-B were dropped into the chambers through vents in the side walls, releasing toxic HCN, or hydrogen cyanide. Those inside died within 20 minutes; the speed of death depended on how close the inmate was standing to a gas vent, according to Höß, who estimated that about one-third of the victims died immediately.[193] Johann Kremer, an SS doctor who oversaw the gassings, testified that: "Shouting and screaming of the victims could be heard through the opening and it was clear that they fought for their lives."[194] When they were removed, if the chamber had been very congested, as they often were, the victims were found half-squatting, their skin colored pink with red and green spots, some foaming at the mouth or bleeding from the ears.[193]

The gas was then pumped out, the bodies were removed (which would take up to four hours), gold fillings in their teeth were extracted with pliers by dentist prisoners, and women's hair was cut.[195] The floor of the gas chamber was cleaned, and the walls whitewashed.[194] The work was done by the Sonderkommando, which were work units of Jewish prisoners. In crematoria 1 and 2, the Sonderkommando lived in an attic above the crematoria; in crematoria 3 and 4, they lived inside the gas chambers.[196] When the Sonderkommando had finished with the bodies, the SS conducted spot checks to make sure all the gold had been removed from the victims' mouths. If a check revealed that gold had been missed, the Sonderkommando prisoner responsible was thrown into the furnace alive as punishment.[197]

At first, the bodies were buried in deep pits and covered with lime, but between September and November 1942, on the orders of Himmler, they were dug up and burned. In early 1943, new gas chambers and crematoria were built to accommodate the numbers.[198]