Prizren: Difference between revisions

| Line 84: | Line 84: | ||

== Prizren now == |

== Prizren now == |

||

Although almost all Serbs are expelled from town, Prizren municipality |

Although almost all Serbs are expelled from the town itself, the Prizren municipality retains communities of [[Bosniaks]], [[Turkish people|Turks]], and [[Roma people|Roma]] in addition to the majority Kosovo Albanian population live in Prizren. Likewise, a significant number of Kosovo Serbs reside in small villages, enclaves, or protected housing complexes.[http://www.osce.org/documents/html/pdftohtml/1200_en.pdf.html] Furthermore, Prizren's Turkish community is socially prominent and influential, and the [[Turkish language]] is widely spoken even by non-ethnic Turks. |

||

== Economy == |

== Economy == |

||

Revision as of 16:02, 17 February 2008

Prizren Призрен | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | |

| Province | (under UN Administration) |

| Government | |

| Elevation | 400 m (1,300 ft) |

| Population (2006)[1] | |

| • Total | 171,464 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| Area code | +381 29 |

| Website | KK Prizren |

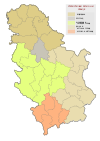

Prizren (Serbian: Призрен, Prizren; Albanian Prizren, Prizreni) is a historical city located in Kosovo, a Serbian province under United Nations administration since the 1999 Kosovo War. It's located at 42°14′N 20°44′E / 42.23°N 20.74°E [1]. The city has a population of around 170,000, mostly Albanians[1]. It is the administrative capital of the Prizren municipality, which has an estimated population of about 221,000 inhabitants[2], both in town and in 76 villages which are a part of the municipality. Prizren is located on the slopes of the Šar mountain in the southern part of Kosovo, close to the border with Albania and partly the Republic of Macedonia.

History

The area of the Prizrenska Bistrica valley has been settled by Illyrians since ancient times.

The city already existed in Roman times, and in the 2nd century A.D. it is mentioned with the name of Theranda in Ptolemy's Geography. [citation needed] In the 5th century A.D. it is mentioned with the name of Petrizên by Procopius of Caesarea in De aedificiis (Book IV, Chapter 4). Sometimes it is mentioned even in relation to the Justiniana Prima. [citation needed]

It is thought that its name comes from old Serbian Призрѣнь, from при-зрѣти, indicating fortress which could be seen from afar[2] (compare with Czech Přízřenice).

According to Eric Hamp, the name of Prizren comes from pri, meaning "fortress, town", and Zeranda, a modification of the name Theranda, which gives Prizeranda. From that there is myrriad of different forms of the name Priserendi, Pyrserendi, Priserend, Prizeren, Pirzerin, Prizren etc. [citation needed]

In 1019, after the fall of the First Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Samuil, the Byzantines created a Theme of Bulgaria, raising a Bulgarian Episcopate in Prizren.

A Slavic rebellion arose in 1072 under George Voiteh. Constantine Bodin of the House of Vojislavljević who was also son of Duklja's Serbian Slavic King Mihailo Vojislav was dispatched by his father and Duke Petrilo with 300 best Serb soldiers to merge with Voiteh's forces in Prizren. There, Bodin was crowned Petar III, Czar of Bulgarians of the House of Comitopuli. The rebellion was crushed in months in 1073 and Eastern Roman rule restored.

In a war with the Crusaders against the Byzantine Empire, Serbian Duke Stefan Nemanja conquered Prizren in 1189, but after the defeat of 1191, had to give the city back to the Byzantines. The City was taken by the Bulgarian Czardom in 1204, although, it was finally seized by Grand Prince Stefan II Nemanjić in 1208 during his quarrels with the Bulgarian Czardom.

Serb King Stefan Milutin raised the Temple of Our Holy Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren which became the seat of the Serbian Orthodox Christian Prizren Episcopate. During the reign of Emperor Stefan Dušan throughout the 14th century, Prizren had the Imperial Court and was the political center of the Tsardom. Serb King/Tsar Dušan raised the massive Monastery of Saint Archangel near the City in 1343-1352. In the vicinity of Prizren was Ribnik - a town where the two Serbian Emperors had their Courts. The city of Prizren became known as the Serbian Carigrad because of its trading and industrial importance. It was the centre of production of silk, fine trades and a colony of merchants from Kotor and Dubrovnik. In the 14th century in Prizren was the seat of the Ragusan Consule for the entire Serb monarchy.

The city became a part of the domain of the House of Mrnjavčević under Serb King Vukašin in the 1360s. With the final disintegration of the Serbian Empire, Zeta's ruler Đurađ I of the House of Balšić dynasty took the City with the surroundings in 1372. The House of Branković under Vuk Branković then became the City's owners, under vassalage to the House of Lazarević that managed to reunite the former Serb Lands. Lazarevićs' founder, hero Prince Lazar Hrebeljanović was educated in Prizren. The dynasty would switch allegiances to the Ottoman Empire before returning under the Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarević.

The Ottoman Empire soon took the city in 1545. Later it became a part of the Ottoman province of Rumelia. It was a prosperous trade city, benefiting from its position on the north-south and east-west trade routes across the Empire. Prizren became one of the larger cities of the Ottomans' Kosovo Province (vilayet). Prizren's Orthodox Christian population was replaced by the Muslim, with migrations of Albanians from the southwest and the neighbouring rural areas.

In 1838 an Austrian physician, Dr. Joseph Muller while he was on his voyages across southern-western part of Kosovo, listed the population of the Prizren District (Prizreni Bezirke) within the Ottoman Kosovo Province: [citation needed]

Prizren was the cultural and intellectual centre of Ottoman Kosovo. It was dominated by its Albanian Muslim population, who comprised over 70% of its population in 1857. The city became the biggest Albanian cultural centre and the coordination political and cultural Capital of the Kosovar Albanians. In 1871, a long Serbian seminary was opened in Prizren, discussing the possible joining of the 'Old Serbia's territories with the Principality of Serbia. During the late 19th century the city became a focal point for Albanian nationalism and saw the creation in 1878 of the League of Prizren, a movement formed to seek the national unification and liberation of Albanians within the Ottoman Empire.

At the end of the 19th century, Spiridon Gopchevich, an Austrian traveller - comprised a statistics and published them in Vienna. They established that Prizren had 60,000 citizens of whome 11,000 were Christian Serbs and 36,000 Muslim Serbs. The remaining population were Turks, Albanians, Tsintsars and Gypsies. [citation needed]

During the First Balkan War the City was seized by the Serbian army and incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbia. Although the troops met little resistance, the takeover was bloody. The British traveler Edith Durham attempted to visit it shortly afterwards but was barred by the authorities, as were most other foreigners, for the Montenegrin forces temporarily closed the city before full control was restored. The number of killed Albanians reached 400 or 4000.[citation needed] A few visitors did make it through—including Leon Trotsky, then working as a journalist—and reports eventually emerged of widespread killings of Albanians. One of the most vivid accounts was provided by the Catholic Archbishop of Skopje, who wrote an impassioned dispatch to the Pope on the dire conditions in Prizren immediately after its capture by Serbia:

- The city seems like the Kingdom of Death. They knock on the doors of the Albanian houses, take away the men, and shoot them immediately. In a few days the number of men killed reached 400. As for plunder, looting and rape, all that goes without saying; henceforth, everything is permitted against the Albanians, not merely permitted but willed and commanded. (quoted in the Irish Times, 5 May 1999 [3])

With the invasion of the Kingdom of Serbia by Austro-Hungarian forces in 1915 during the First World War, the City was occupied by the Central Powers. The Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of the City in October of 1918, restoring Montenegro's suzerainity. By the end of 1918, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was formed - with Prizren a part of its historical territorial entity of Serbia. The Kingdom was renamed in 1929 to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Prizren became a part of its Banate of Vardar. The Axis Italian and Albanian forces conquered the City in 1941 during World War II; it was joined to the Italian puppet state of Albania. The Communist of Yugoslavia liberated it by 1944. It was formulated as a part of Kosovo and Metohija, under Democratic Serbia as a part of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia. The Constitution defined the Autonomous Region of Kos-met within the People's Republic of Serbia, a constituent state of the Federative People's Republic of Yugoslavia. In 9-10 July 1945 the Regional Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija held in Prizren adopted the decision of abolishing the region's autonomy and direct integration into Serbia; although Tito vetoed this decision[citation needed].

The Province was renamed to Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo in 1974, remaining part of the Socialist Republic of Serbia, but having attributions similar to a Socialist Republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The former status was restored in 1989, and officially in 1990.

For many years after the restoration of Serbian rule, Prizren and the region of Decane to the west remained centres of Albanian nationalism. In 1956 the Yugoslav secret police put on trial in Prizren nine Kosovo Albanians accused of having been infiltrated into the country by the (hostile) Communist Albanian regime of Enver Hoxha. The "Prizren trial" became something of a cause célèbre after it emerged that a number of leading Yugoslav Communists had allegedly had contacts with the accused. The nine accused were all convicted and sentenced to long prison sentences, but were released and declared innocent in 1968 with Kosovo's assembly declaring that the trial had been "staged and mendacious."

Prizren in the Kosovo War

The town of Prizren did not suffer much during the Kosovo War but its surrounding municipality was badly affected 1998-1999. Before the war, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe estimated that the municipality's population was about 78% Kosovo Albanian, 5% Serb and 17% from other national communities. During the war most of the Albanian population were either forced or intimidated into leaving the town.

At the end of the war in June 1999, most of the Albanian population returned to Prizren. Non-Albanian minorities fled or were forcibly expelled, with the OSCE estimating that 97% of Serbs and 60% of Romas had left Prizen by October. The community is now predominantly ethnically Albanian, but other minorities live there as well, be that in the city itself, or in villages around. Such locations include Screcka, Mamusa, the region of Gora, etc. [4]

The war and its aftermath caused only a moderate amount of damage to the city, with NATO bombing confined to a number of military and security force sites in and around Prizren. Serbian forces destroyed one Albanian cultural monument in Prizren, the League of Kosovo building. Further damage occurred on March 17, 2004, during the Unrest in Kosovo, to Serb cultural monuments such as old Orthodox Serb churches: Our Lady of Ljeviška from 1307, the Church of the Holy Salvation, church of St. George (the city's largest church), the St. George Runjevac, a chapel of St. Nicholas, the Monastery of The Holy Archangels, as well as Prizren's Seminary and all the residences of the local priests were all damaged by Albanian rioters during the unrest.

Prizren now

Although almost all Serbs are expelled from the town itself, the Prizren municipality retains communities of Bosniaks, Turks, and Roma in addition to the majority Kosovo Albanian population live in Prizren. Likewise, a significant number of Kosovo Serbs reside in small villages, enclaves, or protected housing complexes.[5] Furthermore, Prizren's Turkish community is socially prominent and influential, and the Turkish language is widely spoken even by non-ethnic Turks.

Economy

For a long time Kosovo economy was based on retail industry fueled by remittance income coming from a large immigrant communities in Western Europe. Private enterprise, mostly small business is slowly emerging food processing. Private businesses, like elsewhere in Kosovo, predominantly face difficulties because of lack of structural capacity to grow. Education is poor, financial institutions basic, regulatory institutions lack experience. Central and local legislatures do not have an understanding of their role in creating legal environment good for economic growth and instead compete in patriotic rhetoric. Securing capital investment from foreign entities cannot emerge in such an environment. Due to financial hardships, several companies and factories have closed and others are reducing personnel. This general economic downturn contributes directly to the growing rate of unemployment and poverty, making the financial/economic viability in the region more tenuous.[6]

Many restaurants, private retail stores, and service-related businesses operate out of small shops. Larger grocery and department stores have recently opened. In town, there are eight sizeable markets, including three produce markets, one car market, one cattle market, and three personal/hygienic and house wares markets. There is an abundance of kiosks selling small goods. Prizren appears to be teeming with economic prosperity, but appearances are deceiving as the international presence is reduced and repatriation of refugees and IDPs is expected to further strain the local economy. Market saturation, high unemployment, and a reduction of financial remittances from abroad are ominous economic indicators.[7]

There are three agricultural co-operatives in three villages. Most livestock breeding and agricultural production is private, informal, and small-scale. There are two operational banks with branches in Prizren, the Micro Enterprise Bank (MEB) and the Payment and Banking Authority of Kosovo (BPK). [8]

Demographics

| Demographics | |||||||||||||

| Year | Albanians | % | Bosniak | % | Serb | % | Turk | % | Roma | % | Others | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 cens. | 132,591 | 75.6 | 19,423 | 11.1 | 10,950 | 6.2 | 7,227 | 4.1 | 3,96 3 | 2.3 | 1,259 | 0.7 | 175,413 |

| 1998 | n/a | n/a | 38,500 | n/a | 8,839 | n/a | 12,250 | n/a | 4,500 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Jan. 2000 | 181,531 | 76.9 | 37,500 | 15.9 | 258 | 0.1 | 12,250 | 5.2 | 4,500 | 1.9 | n/a | n/a | 236,000 |

| March 2001 | 181,748 | 81.9 | 22,000 | 9.9 | 252 | 0.1 | 12,250 | 5.5 | 5,424 | 2.4 | n/a | n/a | 221,674 |

| May 2002 | 182,000 | 79.6 | 29,369 | 12.8 | 197 | 0.09 | 11,965 | 5.2 | 4,400 | 1.9 | 550 | 0.25 | 228,481 |

| Dec. 2002 | 180,176 | 81.6 | 21,266 | 9.6 | 194 | 0.09 | 14,050 | 6.4 | 5,148 | 2.3 | n/a | n/a | 221,374 |

| Source: For 1991: Census data, Federal Office of Statistics in Serbia (figures to be considered as unreliable). 1998 and 2000 minority figures from UNHCR in Prizren, January 2000. 2000 Kosovo Albanian figure is an unofficial OSCE estimate January-March 2000. 2001 figures come from German KFOR, UNHCR and IOM last update March 2, 2001. May 2002 statistics are joint UN, UNHCR, KFOR, and OSCE approximations. December 2002 figures are based on survey by the Local Community Office. All figures are estimates. Ref: OSCE .pdf | |||||||||||||

See also

References

- ^ a b The World Gazetteer

- ^ DETELIć, Mirjana: Градови у хришћанској и муслиманској епици, Belgrade, 2004, ISBN 86-7179-039-8.

External links

- Municipality of Prizren (in Albanian)

- Prizren municipality (in English)

- Universiteti i Prizrenit

- KFOR NATO forces in Kosovo

- Independent website about Prizren and the Kosovo.