Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

→Quantum physics paradox: new section |

|||

| Line 614: | Line 614: | ||

:What I think they are saying is that while the '''average''' distance of these planets from the Sun may not change by much - the orbits may become more oval...less circular. If that's enough to make the orbit of one planet cross the orbit of another - then KAPOWW!!! - a very big mess! However, the timescale for these events is in the billions of years - more than you, I or humanity in general need worry about. Many of the events described are not due to happen for 5 billion years - and that's about as long as the Sun will last. So it's really kinda unimportant in the grand scheme of things. [[User:SteveBaker|SteveBaker]] ([[User talk:SteveBaker|talk]]) 02:54, 10 June 2009 (UTC) |

:What I think they are saying is that while the '''average''' distance of these planets from the Sun may not change by much - the orbits may become more oval...less circular. If that's enough to make the orbit of one planet cross the orbit of another - then KAPOWW!!! - a very big mess! However, the timescale for these events is in the billions of years - more than you, I or humanity in general need worry about. Many of the events described are not due to happen for 5 billion years - and that's about as long as the Sun will last. So it's really kinda unimportant in the grand scheme of things. [[User:SteveBaker|SteveBaker]] ([[User talk:SteveBaker|talk]]) 02:54, 10 June 2009 (UTC) |

||

== Quantum physics paradox == |

|||

Where's the mistake in this formula? |

|||

:<math> i \hbar = i \hbar \frac {dp}{dp} = i \hbar \frac {d}{dp} p = xp = x (-i \hbar \frac {d}{dx}) = -i \hbar (x \frac {d}{dx}) = -i \hbar (\frac {d}{dx} x - 1) = -i \hbar (1-1) = 0 </math> |

|||

[[Special:Contributions/70.26.154.226|70.26.154.226]] ([[User talk:70.26.154.226|talk]]) 04:48, 10 June 2009 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 04:48, 10 June 2009

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

June 4

NDE recovery, fiction vs real life

I've seen it a hundred times on the tube: someone is found completely inert, often in water, and there's a moment of suspense – is the character pining for the fiords? – while CPR is attempted; then the rescuee noisily resumes breathing, and immediately is fully awake (though disoriented).

Does that really happen? —Tamfang (talk) 00:20, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- While it's possible for a victim to regain consciousness, any good CPR will break ribs. Going from unresponsive to verbal (making sounds without any meaning) is probably the best you can hope for. Certainly most CPR will not result in a save, and you can ask anyone in the field. M@$+[[@]] Ju ~ ♠ 00:33, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- In that situation, would the heart necessarily have stopped? If all that is required is mouth-to-mouth then I think full conciousness can return pretty quickly. CPR is normally just to keep the person alive until someone with a defibrillator gets there (and even then, your chances aren't anywhere near as good as TV hospital dramas would have you believe). --Tango (talk) 01:39, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- While it's possible for a victim to regain consciousness, any good CPR will break ribs. Going from unresponsive to verbal (making sounds without any meaning) is probably the best you can hope for. Certainly most CPR will not result in a save, and you can ask anyone in the field. M@$+[[@]] Ju ~ ♠ 00:33, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Isn't it the case that in Real Life, the vast majority of 'flatlines' still result in death, despite the best efforts of everyone? EDIT: Also, that a defibrillator is useless in this situation, despite what TV tells us? --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 02:45, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Properly done CPR need not break ribs. Edison (talk) 02:58, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I have no idea if this is actually true but I remember reading one of those 'true medical confessions!' books ages ago in which an anonymous MD stated that it was not unknown for doctors to deliberately break the patients ribs by performing rough CPR on a patient that they already knew was toast - if the relatives were watching. The thinking being that they'd see that and be assured that absolutely everything that could've be done had been done in an attempt to save the patient... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 03:06, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- That is correct; the ever-popular 'flatline' (beeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeep) in televised medical dramas is not a shockable rhythm. (See asystole). Cardiac arrests can be divided into two broad groups: those which still include some mechanical action by the heart (ventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation), and those which don't (asystole, pulseless electrical activity). The former are susceptible to defibrillation and have a much higher survival rate. The latter aren't shockable, and have a very poor prognosis.

- Our article on cardiac arrest notes an overall survival rate of about 15% for in-hospital arrests. (Out of hospital rates are lower.) Patients with shockable rhythms fare about ten times better than those with asystole. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 13:48, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- There are many studies of near drowning events, unfortunately i don't have access to any that would answer your question. 100% of victims will survive in the short term (otherwise it's a drowning and not a near drowning). Approximately 80% will survive beyond 24 hours, perhaps with some degree of neurological deficit. Many children with cyanosis or hypoxia following recovery resume breathing after clearing the airway and one or two rescue breaths, and are conscious and alert immediately thereafter.

- If the victim is in arrest the prognosis is much poorer, hypoxia has been prolonged and the brain is now ischemic. CPR alone will probably not result in a return of spontaneous circulation, let alone regaining consciousness, defibrillation and/or drugs are required. One thing to note tho is that even professional healthcare providers have a poor success rate at finding a carotid pulse during a suspected arrest event. The following scenario most likely could happen: an apneic victim is removed from the water, rescuers begin CPR but fail to note the presence of a pulse. The victim resumes breathing and shortly regains consciousness. Chest compressions were performed but were not required.—eric 15:37, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

To clarify, my question is not about the odds of survival after (near)drowning or heart attack or whatever, but about the TV cliché of sudden recovery of full consciousness. —Tamfang (talk) 19:02, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Penile's Erectiom Angel

plz answeer, how can i measure my Penile's Erection angle ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Greatfencer (talk • contribs) 01:11, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I suppose a mirror might help. —Tamfang (talk) 02:33, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Of course, the angle of the dangle is inversely proportional to the heat of the beat... --Jayron32.talk.contribs 02:50, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- (EC)Use your goniometer. If you do not have one handy, the angle of the dangle has been said to be inversely proportionate to the heat of the meat, so a Meat thermometer might allow an accurate indirect measurement. Other anatomical surrogate measurements are mentioned in the work cited. Edison (talk) 02:54, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The word "goniometer" does not mean "a thing to measure gonads," just as "episcotister" is not a device to test episcopals. Edison (talk) 04:54, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- (EC)How's about making an appointment for a visit to your local hospital's Penile tumescence lab? For some reason, the hospital seen on House M.D. would appear to have more than one. --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 03:00, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Employ the service of a fluffer who charges by the degree and read the invoice. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 09:53, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- <applause> —Tamfang (talk) 19:14, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Drop a barometer from the top to determine the height, and use trigonometry. I am assuming that you know, or can measure, the length. -- Coneslayer (talk) 13:08, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- <applause> —Tamfang (talk) 19:14, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Take the barometer to a fluffer and say "I'll give you this really nice barometer if you'll measure the angle". SteveBaker (talk) 23:45, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I think that when dealing with an erection angel I wouldn't worry about her measurements. APL (talk) 03:49, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Does an erection angel work for a sex goddess? --Jayron32.talk.contribs 04:21, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

<sigh> Okay. What you need is a protractor. That's a half-circle (usually plastic) with marks or scratches indicating the various angles. Stand upright (yeah, erect) and place the center of the flat edge of the protractor against the side of your erect penis, so that the protractor is straight up and down. It will probably be easier to take a measurement from your belly downwards rather than from your balls upwards. HTH. Matt Deres (talk) 23:58, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Hmmm - perhaps an inclinometer - it measures your inclination. SteveBaker (talk) 03:19, 6 June 2009 (UTC)

I'm not sure why anyone would care about the angle . . . as long as the wee fella is stiff the angle really does not matter . . .

- It's one half of a Parabola, anyway, thus a conic section. Edison (talk) 05:26, 10 June 2009 (UTC)

global warming and human water retention

06:34, 4 June 2009 (UTC)Paul fitts (talk)What year did the true science of global warming start? what was the Earth's population at that time? What is the percentage of the human body that is made of water? If you had a 3ft cube of ice, and you melted it...how much water would that be in gallons??

the main reason for my questions.....it doesn't really apprear that sea levels are rising, so if ice caps and glaciers are "melting", and the water levels aren't really rising.....wouldn't it stand to reason that, that the "melted" water has to go somewhere, why not human water retention to make up 3+ billion more we've created over ther last 30 years???

Paul Fitts

- The Tuvaluans beg to differ. According to this Reuters article, their whole country could disappear under the waves in 30-50 years. Another factor (which I was reminded of by An Inconvenient Truth) is that if the glaciers are in the water, their melting won't raise the water level. It's when the land-based ice melts that we have to worry. Clarityfiend (talk) 07:29, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- We have, of course, and article at Current sea level rise. Sea level is rising several mm per year. I'm too lazy to work in feet and gallons (which gallons, anyways?), but one cubic meter of ice has 1000 l and will melt into very roughly 900 l of water. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 07:36, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Google can convert between units, put in something like "3 cubic feet in gallons". After that go outside and watch some grass carefully for a few hours. Did you see it grow? Dmcq (talk) 08:00, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- To put this in context - sea levels are rising a few millimeters each year - but each millimeter of rise represents 360,000,000,000 cubic meters of water. There are about 7 billion people - even if each of us was retaining a cubic meter of water (not even close!) we'd represent only about 0.02 millimeters of ocean depth. No - the reason the rate seems low is that 360,000,000,000 cubic meters means that it takes an awful lot of water to raise all of the oceans in the world by one millimeter. But while a few millimeters may not sound much - over 100 years, that's enough to drown quite a few coastal cities. Sadly, the evidence is that the rate of increase is going up year on year - so we could easily have a dozen or more meters of ocean level rise during the lifetimes of our children - of the younger Ref.Desk denizens. SteveBaker (talk) 15:00, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Why are washers so called?

It was one of those idle, late night conversations in the tour van on the way home from a gig ... which led precisely nowhere. My theory is that the bigger examples are called penny washers because they are the size of pre-decimal pennies, but what about smaller varieties, and where does 'washer' come from? Any ideas please? Turbotechie (talk) 07:58, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- According to [1] (80% down the page) the origin of the term "washer" for that piece of metal is unknown, though it has had that meaning for at least 400 years and perhaps as many as 650 years. Dragons flight (talk) 08:23, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Outside a hardware store hung the alarming sign "Nut screws washer and bolts". Cuddlyable3 (talk) 09:42, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Not forgetting there was a launderette next door Mikenorton (talk) 10:01, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Outside a hardware store hung the alarming sign "Nut screws washer and bolts". Cuddlyable3 (talk) 09:42, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- You are right that penny washers are named for the old pennies, and often they are a similar size, but the term can actually be applied to any size washer. It is a washer with a disproportionately small centre-hole. SpinningSpark 16:34, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Just for my own education, do you have a source I can read up on SSpark? I would frame it the other way, since washers are designed for the inserted item, so rather than "disproportionately small centre-hole", I would say "disproportionately large outside-diameter". In my very limited engineering experience in a very specialized field, we termed these "standard" and "frictional" washers, where "frictional" were the big ones, designed to offer a larger weight-bearing surface, as opposed to the I/D / O/D sizes needed to transfer load from a bolt head to a typical clearance hole. Franamax (talk) 23:42, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Do facial products work?

Is there any scientific evidence that any face creams, anti wrinkle creams, eye treatments etc are any better than just splashing water on your face or is it really just hype? Kirk Uk —Preceding unsigned comment added by 87.82.79.175 (talk) 09:26, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- All 3 are better than water at generating profit for someone. Medical eye treatments have to be certified as safe. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 09:46, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Many of the anti-wrinkle creams are proven to give a temporary lift and do so by using proven science, similarly darkness-removal creams can be proven to remove the appearance of darkness by masking/covering it. You may notice that in adverts of these types the claims are always quite vague (to paraphrase Charlie Brooker)...terms such as "98% of respondents agree", "help reduce appearance of", "helps fight" are all very 'vague' and undetailed - throw in a few random science-sounding (merged with natural-sounding) words and you've got something that says nothing when reviewed by a legal team but can suggest 'proof' to the average consumer. 194.221.133.226 (talk) 10:22, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- In the UK, they have to say "improves the appearance of wrinkles" rather than "removes wrinkles" on the ads now. There was one company a couple of years back that got absolutely castigated for making completely false claims about the abilities of their product (Google for 'Boxwellox'). Not quite as bad as the toothpaste that claimed to be able to split water molecules, producing free oxygen for a deeper clean - but still... --Kurt Shaped Box (talk) 10:47, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Sunscreen definitely helps us against wrinkles. It can be scientifically tested that protecting your face against UV rays will make you look younger than you are. For example, faces of truck drivers that have been laterally exposed to sun light have been analyzed, and the half exposed to sun light looked older than the other half.--Mr.K. (talk) 10:57, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- It helps preventively against wrinkles, by the way. --Mr.K. (talk) 12:01, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The big hype of these things in the UK ended quite a few years ago when the manufacturers were faced with either having to downsize their claims - or be treated as medical/pharmacuticals. The fair trade people argued that if they ACTUALLY reduced wrinkles, then these creams must be penetrating the skin and acting on the tissues beneath - which would require them to be classified as drugs. If all they do is fill in the wrinkles - or change their color/reflectivity to make them temporarily less noticable - then that's OK, it's just a cosmetic effect. I don't understand why that's not also the case in the USA. Certainly the claims they make are ridiculously impossible - and if they were possible, these cosmetics would certainly have to be seriously tested because they could have any number of dangerous side-effects. To the extent that they block sunlight, they might work...but their effects are essentially just changes in appearance. SteveBaker (talk) 14:52, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well, they also work as well as any other Moisturizer; that is by providing a barrier against evaporation, they cause the underlying skin to retain more moisture. Higher moisture content equals plumper epithelial cells, and plumper cells equals less wrinkles. Of course, a $5.00 bottle of any decent mositurizing lotion will do that; dropping $40.00 on a small 4 ounce tub of the same stuff mixed with a little make-up to cover over dark patches seems excessive to me... But then again, I'm not an aging woman trying to recapture my lost youth, what do I know. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 17:34, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Hey, wait, here's [2] a SCIENTIFIC assessment of a particular facial product sold by that 'well known high street chemist'. Whether you are impressed by the fact that 43% of the meagre sample thought their skin had improved is up to you. 23% of the placebo sample thought their skin had improved. Richard Avery (talk) 17:38, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- A study involving 50 people; I assume half received the placebo and half the cream? That means of 25 receiving the placebo, 6 liked it, and of 25 receiving the cream, 12 liked it? I wouldn't call such small sample size "statistically significant". The error bars on a sample size of 25 would probably be bigger than the difference between the samples. Heck, I could flip a coin 25 times and get the same results. Additionally, as the sample did not compare the expensive treatment to a cheap one, only to a placebo, it only addresses the possibility that the expensive cream is better than nothing but not neccessarily better than cheaper alternatives. What you have here is a clear example of How to Lie with Statistics. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 17:45, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Ah! "Buy our amazing anti-wrinkle cream - it has a one in five chance of being better than smearing lard on your face." SteveBaker (talk) 19:51, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- But lard has the advantage of making you smell like pie crust and biscuits. Who wouldn't want to smell fresh-baked pie crust all day? --Jayron32.talk.contribs 20:44, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Ah! "Buy our amazing anti-wrinkle cream - it has a one in five chance of being better than smearing lard on your face." SteveBaker (talk) 19:51, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- If I did it right, that's a 99.9999999635% significance level. If I did it wrong, it's even higher. This should be a two-tailed T-test (try saying that ten times fast), right? There may be problems with that study, but sample size isn't one of them. — DanielLC 16:48, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- According to the Mayo Clinic, "Research suggests that some wrinkle creams contain ingredients that may improve wrinkles. But many of these ingredients haven't undergone scientific research to prove this benefit. If you're looking for a face-lift in a bottle, you probably won't find it in over-the-counter (nonprescription) wrinkle creams. But they may slightly improve the appearance of your skin, depending on how long you use the product and the amount and type of the active ingredient in the wrinkle cream."[3] A Quest For Knowledge (talk) 17:58, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- A study involving 50 people; I assume half received the placebo and half the cream? That means of 25 receiving the placebo, 6 liked it, and of 25 receiving the cream, 12 liked it? I wouldn't call such small sample size "statistically significant". The error bars on a sample size of 25 would probably be bigger than the difference between the samples. Heck, I could flip a coin 25 times and get the same results. Additionally, as the sample did not compare the expensive treatment to a cheap one, only to a placebo, it only addresses the possibility that the expensive cream is better than nothing but not neccessarily better than cheaper alternatives. What you have here is a clear example of How to Lie with Statistics. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 17:45, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- (EC)::There is Absorption (skin). If any of the products achieve that the questions become: Do you want the substance that gets absorbed in your system? and Does your body do anything with the absorbed substance in the layers of skin that is beneficial or does the absorbed substance just accumulate or get transported away? There are some things like Botox which is a neurotoxin and Silicone or animal derived Collagen that can be injected into the skin. Since they work "internally" they get treated as medical/pharmacutical. Nevertheless they have come under criticism because the two questions above didn't come up with consistent answers when asked by different reviewers. The cosmetics industry is trying to stay away form the cost of having to get their products subjected to licensing for pharmaceuticals (see Cosmeceutical). So they have to come up with things that do not "affect the structure or function of the human body". The reputable ones also try to make sure that their products do not contain known toxins or substances that cause harm in the short term (long term use sometimes reveals things that didn't show up in testing.) Probably more driven by their desire to avoid costly product liability suits than anything else. Adding Surfactants like soap to water makes it a more efficient detergent. It also removes the protective layer of lipids covering the skin and knocks ph of the acid mantle out of whack. To counterbalance that you can apply oils to your skin after washing. Since using pure oils would give you an unpleasant and impractical film of oil on your skin what we use are emulsions. (Also see Cold cream). Since those are prone to Rancidification and microbial growth you'll not only find emulsifiers and stabilizers but also preservatives in those. (Sometimes cleverly marketed as new Vitamin ingredient) In a further step the cosmetics industry then created Moisturizers. Splashing water on your face would not have the same effect, rather the opposite actually. It would rinse away some more oils exposing cells to evaporation and upset the hydrostatic balance causing further drying. It works through constricting fine blood vessels in the skin. AFAIK interest in reducing wrinkles has only gained momentum throughout the past 70 years or so. That along with our increasing knowledge of biochemical processes in the human body has led to many theories being put forward and being rebuked in that respect. The focus used to be the moisture contents of the stratum corneum. Now things like electrolyte balance, Free radicals, cell aging and nerve stimulation, among others, are under study. Some of those studies are either financed by the cosmetics industry through grants, or done in their labs. Study results from company owned labs are rarely published. (If one of their labs found the holy grail in anti-wrinkle treatment I bet they'd gladly spin off a subsidiary and go through the pharmaceutical trials.;-) Facial products work in the regard that they don't leave greasy marks on your clothes or things you touch, don't spoil fast, smell pleasant and supply lipids to your skin. A cooling effect while the continuous phase of the emulsion evaporates is also well established. Product differentiation has companies add various ingredients that at best can provide better product performance and at least not cause any harm. You'd have to research each labeled ingredient separately to get an idea. It is very likely though that lots of substances aren't listed or any research studies are under lock and key at the company. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 00:04, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

To DanielLC, your analysis of the Boots anti-wrinkle cream data is not correct. The data uses discrete variables, not continuous variables. There are two categories of subjects: those with placebo, and those with the new cream. There are two categories of outcome: improvement, or no improvement. We need a chi-square test. The article indicates a total of 60 people in the trial. Let's assume that 30 people were in each group.

| Cream type | Improvement | No Improvement | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| New cream | 13 | 17 | 30 |

| Placebo | 7 | 23 | 30 |

| Total | 20 | 40 | 60 |

| Cream type | Improvement | No Improvement | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| New cream | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| Placebo | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| Total | 20 | 40 | 60 |

Running a chi-square test (without Yates correction) gives a probability of 0.10

This is not statistically significant (by usual criteria). Axl ¤ [Talk] 20:36, 7 June 2009 (UTC)

- Although this uses a discrete distribution, it can be approximated as normal distribution. I suggest we move this to the math desk and ask them what test to use. — DanielLC 22:17, 10 June 2009 (UTC)

- Feel free to ask at the maths desk, although I am not particularly interested in their opinion. Perhaps you would consider showing your working to demonstrate your conclusion? Thanks. Axl ¤ [Talk] 16:19, 11 June 2009 (UTC)

What happens to toxic sewage sludge?

About 40 - 60% (depending on whether you are in the EU or USA) of treated sewage sludge (biosolids) is reused as agricultural fertilizer. From what I can see on the article on biosolids, the main reason some biosolids cannot be used as fertilizer is that they have a heavy metal and toxic substance content that is too high. Is this true? If so, what happens to this waste? Is it incinerated, landfilled etc? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 157.203.42.175 (talk) 13:23, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- According to this parliamentary note [4], in the UK 62% is applied to agricultural land, 19% is incinerated, 11% is being used in land reclamation with the remainder going to landfill or composting. It also discusses the use of sludge to generate energy from biogas through anaerobic digestion. The report does not mention toxicity as a problem, apart from the issue of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Mikenorton (talk) 14:11, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Sludge has some information. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 04:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

Frozen peas float when cooked

When you put frozen peas in a saucepan of cold water they sink to the bottom. When the water is heated up the peas float to the surface. But as ice is lighter than water, and frozen peas must contain some ice, I would expect the opposite to happen, i.e. they would start off floating then sink when heated. What is going on here? Lonegroover (talk) 14:45, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Peas contain lots of stuff besides just water, so maybe enough to overcome the buoyancy from decrease in density of the water being frozen. Do the peas remain the same size, or do they expand when they thaw/heat? Does this happen only if the water gets hot, or can you reproduce it with room-temp water (to exclude nucleated steam giving the lift)? DMacks (talk) 14:53, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Don't forget that water is densest at about 4C. My guess (and it really is just speculation) would be the following:

- Water, in a saucepan at about 10 degrees C, combined with peas at about -18C. Peas initially float in cold water before sinking so clearly the water is denser for a short period. Presumably due to the low temperature of the peas? I would assume that the peas rapidly warm due to their high surface area to volume ratio. As such, the water within the peas would be denser than the water in the pan. Peas have other constituent components, but I would suggest the density of the water in the peas outweighs and (lower) density from the solid matter of the pea. The overall density of the pea should approach the point where they are denser than the surrounding water - this shouldn't be too difficult, the water will be getting colder from the peas but also warmer from the heat input.

- I would imagine that the peas remain denser (colder) than the surrounding water for a while - since the source of heat would warm the water first, then the peas When the water boils, the peas could reach a temperature equilibrium with the water (since the water cannot get hotter, regardless of heat input, without turning to steam), or at least become warm enough such that the weighted average of the density of the pea (i.e. the solid matter and water contained within the pea) could overcome the density of the hot/boiling water. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 157.203.42.175 (talk) 15:07, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The obvious answer is thermal expansion of the peas. Assume the peas have a density near water, but slightly more dense. This is because they are mostly water, but with some solid materials. As the peas heat, their radius expands by some small amount - but their volume increases according to (radius3), so their density will decrease inversely to that. Although water does change its density slightly, it's generally a good assumption that it is an incompressible fluid. Its density should not change significantly between room temperature and near-boiling. (Our article gives about a 5% change, but I don't know if I trust the source data). But, the water inside the peas will also expand - and so the only relevant volume change is the thermal expansion of the solid materials in the pea. Nimur (talk) 14:44, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

What happens if I drink five-year-old soda?

Not fridged, the 12-pack wasn't even opened. Just curious. I think I'll throw it out anyway. 67.243.7.41 (talk) 15:34, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- OR having tried it once. It won't be toxic, but it may be unpalatable as the bubbles will be gone and it may be a bit sludgy on the bottom of the can. 65.121.141.34 (talk) 16:23, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- This is not medical advice BUT: you might gain super powers. It's a possibility. Consider your future life as Soda Man, and whether or not you are willing to take on that responsibility. --98.217.14.211 (talk) 16:55, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Throwing it away it probably wise. I doubt there will be anything harmful about it, but it probably won't taste very nice (depending on how it was stored). It is possible the seal has been broken somehow which might have allowed something harmful to get in, so probably not worth the risk. --Tango (talk) 18:38, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Sugar soda may retain its flavor longer than artificially sweetened soda. I once had some old pop sweetened with Nutrasweet and all sweetness was gone. It tasted like unsweetened Coke with pineapple juice added. Heat speeds the breakdown of Nutrasweet. There is always a possibility that over time there could be greater leaching of metal or plastic from the can into the drink. If it is sealed, how would any carbon dioxide escape to make it flat? Edison (talk) 18:42, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Major OR here, but I had some cans of orange soda that actually started leaking through the bottom of the cans after eight or nine years. They were unopened and keep in a closet. The soda actually caused corrosion and leaked out. cheers, 10draftsdeep (talk) 19:38, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- If its in a can, the soda may have eroded away enough of the can to impart a metallic taste. Don't know if its toxic though. Livewireo (talk) 21:22, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Most modern cans have a coating of plastic on the inside I do believe. If the (presumably) citric acid in the orange soda and/or the carbonic acid in any soda has gotten through to the metal of the outside of the can, it's likely also dissolved the plastic coating on the way. This would presumably include any phthalate and/or bisphenol components of the coating plastic. Luckily, most plastic compositions are considered trade secrets, and there is intense dispute over the bio-effects of various plastic additives (softeners, etc.) which may or may not be in the plastic anyway (trade secret!) - so we can just dismiss the whole thing as "no definite evidence". Franamax (talk) 23:33, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- If its in a can, the soda may have eroded away enough of the can to impart a metallic taste. Don't know if its toxic though. Livewireo (talk) 21:22, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Major OR here, but I had some cans of orange soda that actually started leaking through the bottom of the cans after eight or nine years. They were unopened and keep in a closet. The soda actually caused corrosion and leaked out. cheers, 10draftsdeep (talk) 19:38, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Sugar soda may retain its flavor longer than artificially sweetened soda. I once had some old pop sweetened with Nutrasweet and all sweetness was gone. It tasted like unsweetened Coke with pineapple juice added. Heat speeds the breakdown of Nutrasweet. There is always a possibility that over time there could be greater leaching of metal or plastic from the can into the drink. If it is sealed, how would any carbon dioxide escape to make it flat? Edison (talk) 18:42, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Check this out: Benzene in soft drinks, then check the label of your soda can. It won't kill you (immediately) but it's not healthy either. Also "a soft drink such as a cola has a pH of 2.7-3.0 compared to battery acid which is 1.0". That and the other ingredients, plus the can should make for an interesting environment for many chemical reactions and interesting compounds to form over time. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 00:26, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Of course, you do realize that a pH of 3.0 is 1% as acidic as a pH of 1.0. Thus, soda has about 1% of the acid concentration of battery acid. Of course, the liquid in your stomach is pH of around 2 or so, which means that the soda is only 10% as acidic as your own gastric juices, or if you prefer, your gastric juices are 10 times as acidic as soda. Welcome to the wonderful world of logarithms. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 04:17, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- That's one of the reason I put that quote from an ooold paper in quotation marks. Your stomach is however a pretty good example of an environment that has interesting chemical reactions happening. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 06:00, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Of course, you do realize that a pH of 3.0 is 1% as acidic as a pH of 1.0. Thus, soda has about 1% of the acid concentration of battery acid. Of course, the liquid in your stomach is pH of around 2 or so, which means that the soda is only 10% as acidic as your own gastric juices, or if you prefer, your gastric juices are 10 times as acidic as soda. Welcome to the wonderful world of logarithms. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 04:17, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Check this out: Benzene in soft drinks, then check the label of your soda can. It won't kill you (immediately) but it's not healthy either. Also "a soft drink such as a cola has a pH of 2.7-3.0 compared to battery acid which is 1.0". That and the other ingredients, plus the can should make for an interesting environment for many chemical reactions and interesting compounds to form over time. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 00:26, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Note that you generally don't want to drink any non-diet soda with a broken seal that's older than a few days - once it gets exposed to the environment I would expect the bacteria to come in and party on the sugar. A diet soda on the other hand might be fine for a longer period of time. I'm not sure. Dcoetzee 06:39, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Nope Aspartame is less stable that sugar and gets broken down after a while. The interesting thing is what reaction products you're going to get. 71.236.26.74 (talk) 07:28, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

Capturing a warm bath's heat

It's winter in the southern hemisphere and a nice way to heat up is by taking a warm bath. I couldn't help thinking though of all the energy that gets lost when the warm water flows out the drain after a bath. Given that:

- a kilocalorie is the amount of energy it takes to heat a liter of water by 1 degree Celsius

- lets assume my bathtub holds 150 liters of water

- it's about 17 degrees in my apartment, the water after I'm done bathing is 40 degrees Celsius, a 23 degree difference

I asked Google: "(150 * 23) * kilocalories in kilowatt hours" and got "(150 * 23) * kilocalories = 4.00966667 kilowatt hours"

That's 4 kilowatt hours of energy down the drain! That's like a 1000 watt heater staying on for 4 hours. so this makes me ask, does it make sense to keep the water in the bathtub until it has cooled down so that my place will heat up a bit? One concern is evaporation that might cause the humidity to rise and thus the energy is kept as latent heat rather than actual. In that case, is there something simple one can do to prevent evaporation?

196.210.200.167 (talk) 16:14, 4 June 2009 (UTC) Eon

- Any added humidity will make you feel warmer, which is just as good, isn't it? --Sean 18:25, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I'm not sure. The formulas are given in Fahrenheit, but I suspect at 17 degrees a higher humidity might even make you feel colder. Seems counter intuitive though that just leaving the water in the bathtub can make such a huge difference. 196.210.200.167 (talk) 19:39, 4 June 2009 (UTC) Eon

- A lid on the bath would prevent evaporation. --Tango (talk) 18:36, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I don't see why leaving the water in the bath until it's cooled right down wouldn't work. The humidity might be a problem for your bathroom - but you'll certainly have a slightly lower heating bill if you do this. It's not a bad idea actually. SteveBaker (talk) 19:44, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- According to my electric bill, 4kWh is worth almost 35c, though I would imagine that it would not apply the heat evenly throughout your dwelling (unless you have incredible outer wall insulation)65.121.141.34 (talk) 19:53, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Don't have the time to google for it, but there is a product that recovers heat from water and air leaving the house through bathroom vents and plumbing. Can't recall what it was called. (I think "this old house" had one in one of their shows)71.236.26.74 (talk) 00:31, 5 June 2009 (UTC)o.k. found a couple of pages [5] [6], Matt's comment here [7], [8] Ugh, should have known and we do have a page Waste Heat Recovery Unit - 71.236.26.74 (talk) 03:59, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- According to my electric bill, 4kWh is worth almost 35c, though I would imagine that it would not apply the heat evenly throughout your dwelling (unless you have incredible outer wall insulation)65.121.141.34 (talk) 19:53, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- My contingency plan for what to do in the event of a prolonged power failure in winter includes leaving the hot (and a bit of cold) water trickling into bathtubs and sinks, to keep the pipes and drains from freezing and to heat the house from the water heater. This assumes the overflow can remove the water with the drain plugged. A diverter to direct the hot water to the far end of the tub might be useful. One would get tired of a batch mode of filling the tub and then draining it after an hour, repeated 24x per day. Fireplace and kitchen range (hob) or oven could also be used to advantage, but with suitable care for carbon monoxide. Edison (talk) 04:49, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

gravitational equations

Is/are the equation/equations for gravity at the center of a Black Hole the same as the equation/equations for gravity in unoccupied (empty) space? ---- Taxa (talk) 17:20, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- At the very centre of a black hole, the singularity, the laws of physics break down (ie. we don't really know what happens), so there are no equations. In an appropriate coordinate system (eg. Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates) you can use the same equations to describe everywhere except the singularity, though. --Tango (talk) 18:47, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The singularity at the very center of a black hole does things to the equations that physics depends on that are essentially the same as dividing by zero on your pocket calculator. There is no meaningful answer. But a billionth of a trillionth of a gnat's eyebrow from the center, the laws of physics should be pretty well-behaved. The equations are exactly the same - but because these are rather extreme circumstances, you have to use the full relativistic forms of these equations, not the 'low speed/low gravity' approximations that we all learned in high school. SteveBaker (talk) 19:41, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- What is the length of a gnat's eyebrow in Planck lengths? Does anyone know? --Tango (talk) 02:08, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well, the photo at right claims to be 100x magnification. But (...pet hate...) I'm viewing this simultaneously on a 14" monitor and an 81" plasma screen...so it's a bit hard to measure exactly! SteveBaker (talk) 04:04, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- It's a featured picture as well, I'm surprised nobody caught that... --Tango (talk) 12:29, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well, the photo at right claims to be 100x magnification. But (...pet hate...) I'm viewing this simultaneously on a 14" monitor and an 81" plasma screen...so it's a bit hard to measure exactly! SteveBaker (talk) 04:04, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- What is the length of a gnat's eyebrow in Planck lengths? Does anyone know? --Tango (talk) 02:08, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

DO GRAVITATIONAL ENERGY OF EARTH REDUCE BY TIME?

Earth keeps the moon in it's gravity spending it's energy .From where do earth gain this energy? If earth do not gain energy,then is it's gravitational energy reducing by time?Surabhi12 (talk) 18:06, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The earth does not spend energy in order to keep its moon. Dauto (talk) 18:19, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well, not in classical physics. But in relativistic physics, the circling moon will cause gravitational waves, which will carry away some of the potential energy of the Earth-Moon system. The effect is very small, and, at the moment, entirely overshadowed by the tidal transfer of rotational momentum from the Earth to the Moon. See Gravitational wave#Power_radiated_by_Orbiting_Bodies. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 18:26, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

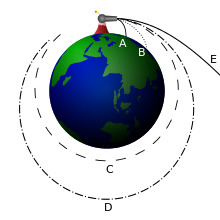

- The moon is falling towards the Earth, but luckily it keeps missing, just like cannonball "C" shown in the picture. It doesn't take any energy for this to happen. See orbit. --Sean 18:31, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- And the Earth is falling towards the moon, but luckily the moon keeps moving out of the way ;) Gandalf61 (talk) 12:30, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Somebody owes me a dollar. (I've decided that I'm charging the universe a dollar every time someone confuses a 'force' (gravity in this case) with 'energy' - I plan to earn enough money from this confusion to replenish my poor 401K). The force and energy are very different things. When you stick a fridge magnet onto your fridge, the magnet exerts a force on the metal. But so long as the magnet doesn't move - it doesn't take any energy whatever for it to just hang there...magnets don't "run down". It's the same with the moon. The gravity pull between earth and moon is just a force. So long as the two bodies don't get closer or further apart - there is no energy transaction involved. Forces don't "run down" - they just are. If you hang something from the ceiling with a rope - the rope exerts a force...the rope doesn't "run down". Now, if something were to pull the moon further from the earth - that 'something' would have to expend some energy to do it...if the moon (for some reason) were to fall closer to the earth - then it would actually gain energy (kinetic energy initially - then one hell of a lot of heat energy when it kersplatted into the middle of the pacific ocean!). SteveBaker (talk) 19:35, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Would another explanation be that the Earth is neither exerting a force nor expending energy, it is simply warping space-time such that the shortest path for the Moon to travel through the geodesic happens to be a circle? Just asking... Franamax (talk) 20:07, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Now now, don't confuse a good discussion with a simple, elegent and correct answer. No one needs that now! --Jayron32.talk.contribs 20:34, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Yes, but relativity gives people headaches! That, and the concepts Steve is talking about apply to all forces, even ones that can't be easily dismissed as mere geometry. --Tango (talk)

- I'll give you a dollar. Remind me if see you - bring change! --Tango (talk) 02:07, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Oooh! Thank-you! Actually - with the number of people making this error - I'm pretty sure I can still turn a profit at one Zimbabwean dollar per confused OP. :-) SteveBaker (talk) 03:58, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Single Zimbabwean dollars are now so rare that, pervesely, they are probably now valuable to collectors. SpinningSpark 13:48, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- and another piece of trivia (I can't leave this one alone) is according to this the $US is now worth more than a mole of the original $ZW. That must be a first for a currency. SpinningSpark 14:17, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Oooh! Thank-you! Actually - with the number of people making this error - I'm pretty sure I can still turn a profit at one Zimbabwean dollar per confused OP. :-) SteveBaker (talk) 03:58, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Would another explanation be that the Earth is neither exerting a force nor expending energy, it is simply warping space-time such that the shortest path for the Moon to travel through the geodesic happens to be a circle? Just asking... Franamax (talk) 20:07, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

problem of race

Imagine:

A car travels 10km in an hour A bus travels 20km in an hour both have a race Car is ahead of bus at point A. By the time bus moves to the point A,car must have move little ahead say to point b. By the time bus moves to the point b,car must have move little ahead again say to point c. By the time bus moves to the point c,car must have move little ahead say to point d. This continues ......... Thus car has to become the winner. IS THIS POSSIBLE? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Surabhi12 (talk • contribs) 18:30, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- See Zeno's paradoxes. Short answer - it takes an infinite number of steps for the bus to overtake the car but because each of those steps takes sufficiently less time than the one before the total amount of time required to overtake is finite. See convergent series for the maths behind that. --Tango (talk) 18:35, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Another way to look at this is that suppose the car starts off with a lead of (say) 10km. We know that using 'sensible' math, that the bus will travel at a distance D in time T=D/20 hours and the car at time T=(D-10)/10 hours. When the bus overtakes the car, they are at the same distance at the same time - so we can solve the simultaneous equations and calculate T as 1 hour. The bus catches the car after 1 hour - then zooms right past it. No problem, no controversy, no paradox.

- But the crazy Zeno's paradox way says: The time it takes the bus to reach A is 1/2 hour. By that time, the car has travelled 5km to point B. 15 minutes later, the bus reaches B and the car has gone on another 2.5km to C. 7.5 minutes later, the bus reaches C...so Zeno tells us where the bus and the car are after 30+15+7.5+3.75+1.875+... minutes. Mathematically, that infinite series adds up to 59.999... minutes. And the distance that the car and bus have travelled in that time is 19.999...km from the start. Well, that's all very interesting and exciting - but by refusing to every allow the 'victim' of the paradox to just go ahead and ask where the vehicles are after a longer amount of time, he arbitarily forces us to look only at times before the two vehicles actually meet. If you limit your calculations to only times before the vehicles meet - you're obviously never going to find the time when they do actually meet. It's not a paradox - it's a dumb way of stopping the person from answering a ridiculously simple question!

- But why doe Xeno insist on calculating all of these intermediate positions and stubbornly refuse to calculate where they are after exactly one hour? Because he's some stupid philosopher trying to make a name for himself by inventing a "paradox". This is why philosophers are a waste of quarks. We have a perfectly simple, completely understood problem with a VERY simple, non-paradoxical conclusion...but NO...the dumb-as-a-bag-of-hammers philosopher has to insist on never calculating the answer but instead answering an infinite series of questions that we don't need to know the answer to.

- It's really no different to me saying "What is 2+2?" - but instead of just going ahead and counting it out on your fingers, I arbitarily insist that you first calculate a totally unrelated sum: 1+0.5+0.25+0.125+... which (if you try to do it the hard way) will take you an infinite amount of time - and thereby cunningly prevent you from calculating 2+2. Why the heck would you ever want to do it like that? It's obviously a stupid and unnecessary way to answer my question. So - please treat anything any philosopher says much as you would a comedian. Amusing, possibly mildly entertaining - but in no way relating to reality. SteveBaker (talk) 19:22, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well that and your number series will only equal 2 when you are done. 65.121.141.34 (talk) 19:49, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I disagree - I think it is instructive to consider the "paradox" and realize that it is solved by convergence. The obvious logical solution allows the student to intuitively grasp the otherwise abstract idea that adding an infinite number of elements can still lead to a finite solution. This does have practical consequences in the study of advanced science and physics - it's an effective way to consider the parity between discrete and continuous number representations, or quantized vs. continuous physical models. Nimur (talk) 23:19, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Perhaps the solution is to tell the philosopher you think he's wrong and ask him to write out the whole series just to be sure... Franamax (talk) 20:10, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- It is a little unfair to say philosophers are a waste of quarks in reference to ancient Greek philosophers. I agree modern ones are a waste of quarks, but in ancient times "philosophy" was a far broader subject since other things didn't exist yet. It included mathematics and what would now fall under science (but I'm not willing to call what they did science, since it didn't follow the scientific method). It easy for us now to laugh at them not understanding these simple concepts, but they are only simple to us because someone else has explained them to us. The ancient Greeks (and philosophers for quite a while after them) had some very odd ideas about infinity (as do most people today who don't have formal training in mathematics). The reason Zeno's problem seemed paradoxical to them was because they didn't think it was possible to do an infinite number of things (the idea that they got easier and easier so the total amount of resources required remained finite wasn't known to them). You may find Supertask interesting. --Tango (talk) 02:03, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- I am reminded of a quote attributed to Johannes Keppler, though it may be apocryphal. I will paraphrase. Basically, Keppler was lecturing on the organization of the solar system, and one of his students asked something like: "Weren't people 100 years ago rather stupid, I mean, they thought the earth was the center of the Universe, and that everything revolved around us. Doesn't that that make those people rather unintelligent." To which Keppler replied something like "If they were right, and the sun DID revolve around the Earth, would the sky look any different?" which makes the point that its easy given the sum of all human knowledge of today to riducule the past thinkers as somehow stupider than us; but we have the benefit of the incremental progress we have made towards understanding the universe, a process they themselves were a part of. One could just as easily have commented that Newton was an idiot for not taking into account relativistice effects of near-light-speed travel, or that proponents of phlogiston theory were stupid when they thought heat was a substance. 100 years from now people will think we are stupid because some "scientific fact" we are certain is right turns out to be inaccurate in some way. Xeno's ideas look stupid because he didn't have the 2000 years of mathematical thought already spelled out when he devised his paradoxes. However, the basic concept that infinity is a special idea that DOES need its own set of rules to deal with was a unheardof idea at Xeno's time. The fact that anyone was thinking about the infinite several hundreds of years B.C. is pretty prescient if you ask me. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 02:52, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- I'd just like to point out that 59.999...=60. You could have just said the infinite series just adds up to an hour. Also, this paradox was formulated before infinite series (it isn't just what you get when you add all the values together), so you could only get something below 60, but arbitrarily close to it. — DanielLC 16:16, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- That's true - but it doesn't get Zeno off the hook. If we ask when does the hare/Achilles/bus pass the tortoise/car? Or better still we can be REALLY clear and ask: "When is Achilles ten feet ahead of the tortoise?" Then Zeno is arguing that they just meet at T=59.999...=60 - but he's not letting you find out whether the hare ever PASSES the tortoise. So this rather wonderful mathematical result doesn't help us out much! SteveBaker (talk) 02:59, 6 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well that and your number series will only equal 2 when you are done. 65.121.141.34 (talk) 19:49, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Of course, Zeno wasn't actually trying to find out whether or when Achilles passed the Tortoise; everyday observation made it obvious that moving things routinely passed other things. Rather, as Nimur alluded to, he was examining philosophical postulates made by others and using this paradox (alongside several others) to demonstrate their invalidity (much as Ernst Schrödinger didn't really believe a cat could be simultaneously alive and dead, his gedankenexperiment was meant to demonstrate that the concept of quantum superposition was absurd).

- In Zeno's time, some philosophers had postulated that space was (S), others that it was not (s), infinitely divisible; ditto for time (T, t), giving 4 possible combinations (ST, St, sT, st). Zeno constructed a paradox for each of the four scenarios, apparently showing that each was demonstrably untrue (although the st case apparently is true). Perhaps if he'd had Leibnitz's and Newton's benefit of a more manipulable number system, he'd have managed to come up with calculus a couple of millennia earlier. 87.81.230.195 (talk) 16:38, 6 June 2009 (UTC)

Labour and multiple births

Given that Twins, and higher number births, are individuals, do mothers ever experience a sort of delayed labor, in which the second child is born at a vastly different time or even date then their sibling? For example, Paul and John are twins, Paul is born first, and John is born 2 days later, after the mother reentered labor.--HoneymaneHeghlu meH QaQ jajvam 19:31, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- When someone finds a good source on the range, with some statistics, please add the data to the Multiple birth and Twin articles, which should discuss this, but currently lack any data (or even a mention). Tempshill (talk) 19:53, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- If anyone wants to ask at the WP:Library for the fulltexts, here are two sources: "Management of Delayed-Interval Delivery in Multiple Gestations", S. Cristinelli et al., Fetal Diagnosis & Therapy, Jul/Aug 2005, Vol. 20, Issue 4, pp.285-290. (AN 18247478) [9] and "Delayed delivery of multiple gestations: Maternal and neonatal outcomes", M. Kalchbrenner et al., American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 179(5), pp1145-1149, Nov. 1998. [10]. According to the abstracts: in 6 cases studied, the delivery interval is 2:93 (median 7) days; the literature (148 cases from 1979-2001) supports 2:153 (median 31) days; and for 7 cases studied, a difference of 32.6 days. I'm rather startled at some of these numbers for delay in delivery, obviously some of the first-borns were very premature. However the absolute numbers indicate that this amount of delay is very rare. As for minor delays (<2 days), I didn't find much. I've fired off a query to my sister. Franamax (talk) 20:39, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Oohh, jackpot! "Twin-to-twin delivery time interval:...", W. Stein et al., Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica, 2008; 87: 346�353. [11] 4,110 "normal" deliveries, mean interval = 13.5 min (SD 17.1); 75.8% within 15 min, 16.4% within 16-30 min, 4.3% within 31-45 min, 1.7% within 46-60 min, 1.8% > 60 min. Now those are statistics! :) If anyone wants to try writing this up, I have some of the fulltexts and we can put up one of those "Refdesk significantly improved an article" thingies! Franamax (talk) 21:05, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Those statistics with a median of several days are meaningless - the sample has clearly been chosen to be made up of cases with a large delay (since that is what they were studying). The rest of their results may well be interesting, but the length of the delays isn't since they were specially chosen. (The medians are probably only given in order to describe the sample chosen, not to imply anything about delayed births.) --Tango (talk) 01:54, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Franamax, this is outstanding! I added a new "Delivery interval" section to Twin, let me know what you think. The section needs the discussion of the extremely long intervals and could use discussion (beyond the stats) of the very unusual situation where labor begins and then ends, and then a month later begins again. Thanks! Tempshill (talk) 05:47, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Looks good, I'll work a little more on those anomalous cases where labour ceases and the delay runs to several days. I also had found this in Google Books (Multiple Pregnancy, Blickstein, Keith & Keith), which gets right into the details. Another successful RefDesk collaboration! :) Franamax (talk) 07:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Thanks guys!--HoneymaneHeghlu meH QaQ jajvam 00:58, 6 June 2009 (UTC)

- Looks good, I'll work a little more on those anomalous cases where labour ceases and the delay runs to several days. I also had found this in Google Books (Multiple Pregnancy, Blickstein, Keith & Keith), which gets right into the details. Another successful RefDesk collaboration! :) Franamax (talk) 07:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- This time gap had puzzled me in the article on the Chukwu octuplets -- one of the babies was born days before the others. I don't get it. Once the amniotic sac has been breached, the rest of the fetuses are left high and dry. (So to speak.) I'm guessing, but the sequence might be: woman goes into premature labour, rushed to hospital, one baby is already in the birth canal, it comes out and is handed over to neonatologist, contraction-inhibiting drugs are immediately administered to the woman, bed rest in hospital, lots of monitoring, try to give the other bun(s) as much more time in the oven as possible. Something along those lines? BrainyBabe (talk) 20:27, 7 June 2009 (UTC)

helium balloon

If one were to take a balloon that was made of a material that could stretch an infinite amount while maintaining its structure, and filled it with enough helium for it to rise quickly, would it make it into space (assuming temperature also does not effect the structure of the helium compartment)? It is going far slower then the speed needed for orbit, but helium does escape from our atmosphere.65.121.141.34 (talk) 19:58, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- If we're going to invent materials which cannot possibly exist, why not just cast a magic spell on the balloon and teleport it to space? But seriously, the ballon would rise to a point where its density matched that of the atmosphere. For your theoretical infinitely strecthy balloon, since the volume could be infinitely large, the density could be infinitely small, which means the balloon would keep drifting up. I just have a hard time picturing a helium balloon being infinitely stretchy. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 20:41, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- As I understand the way you've stated the material, the answer is maybe space, and maybe escape. It's important to remember that escape velocity is relevant only to a specific impulse of thrust. Anything that continues thrusting as it rises need not reach escape velocity as defined at the surface in order to reach escape velocity. Anyway, the balloon matches the pressure of the atmosphere and will continue to rise (and expand) until it reaches an altitude where its density is the also same as the surrounding atmosphere. This may well be higher than 100 km, which is the usual qualification for reaching "space". This further may be high enough for the solar wind to thrust it away from Earth, thus maybe escaping. In the absence of solar wind, though (and possibly in spite of it), the balloon reaches stable equilibrium -- were it to rise, it would be more dense than the surrounding atmosphere and thus sink. Were it to sink, it would be less dense and thus rise. Since it's still in the atmosphere and its movements dictated by the atmosphere, I wouldn't characterize this as an orbit and I wouldn't expect the balloon to be in free fall. — Lomn 20:50, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I was going to mention how the balloon material would have a density greater than that of helium, thus we could calculate the weight of the balloon at Earth surface and add in the weight of helium it encloses and make a definite calculation of the equilibrium point where the overall density of the balloon-helium system was equal to that of the atmosphere. But of course, since it's infinitely stretchy, we can fill the balloon with all the helium on Earth before we release it, so yes, the average density approaches that of helium alone. Without some constraints, this really can't be calculated... Franamax (talk) 22:23, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- And below a critical density, the atmosphere will behave sufficiently like a vacuum or a sparse plasma. Once the balloon is in the ionosphere or thermosphere, buoyancy will be an insignificant force, and thermal interactions will become insignificant (although, a balloon of near-infinite volume might have sufficient number of thermal collisions to break down our cold plasma assumptions...) Nimur (talk) 23:24, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- You didn't give us enough information to answer your question. Tell us what's the mass of the ballon, what's the mass of the helium inside and what is the tension on the baloon's rubber, and than we may be able to give you a reasonable answer. Dauto (talk) 00:59, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- The atmosphere has no end, so I guess the simplest answer is that it will continue to rise and expand until interactions with the rest of the solar system become more significant than interactions with the Earth (which basically means it has escaped the Earth). At some point, either bouyancy would cease to be significant or you would reach a point where the atmosphere gives way to the Interplanetary medium, which I believe is mostly (ionised) hydrogen, so is less dense than helium at equal pressure (to the extent that pressure is well defined in such circumstances). However, your assumptions are clearly impossible, so the only entirely accurate answer is "anything could happen". (See Vacuous truth.) --Tango (talk) 01:46, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, the atmosphere has an ill-defined end; it gets infinitessimally thinner as you keep going out from the earth. This does NOT mean that it has no end; to assume it never ends is to make the same error that is made in Xeno's paradoxes. (See discussion elsewhere at the ref desk on this). Eventually, the matter density of the atmosphere fades to match the average matter density of the rest of the so-called "empty space" of the rest of the solar system. At that point, we can say that the atmosphere has ended, since it has become indistinguishable from space. That line can be clearly drawn around the earth, so there is no point in saying it "never" ends. The atmosphere is a physical example of a convergent infinite series, and the operative part here is "convergent". The limit where the diminishing atmosphere converges with the rest of space we can say the atmosphere ends. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 03:06, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- By "has no end" I meant it never becomes a true vacuum, which is what would be required for this idealised balloon to stop rising and float on top of the atmosphere. I talked about the atmosphere giving way to the interplanetary medium, so I think it is quite clear that I understand what is going on... --Tango (talk) 03:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Well, lets call it a misunderstanding over the use of imprecise language. It would be easy to assume that, when you say it "has no end" that the it continues on forever. It doesn't really, its just that you have to define what you mean by "end". --Jayron32.talk.contribs 03:32, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- By "has no end" I meant it never becomes a true vacuum, which is what would be required for this idealised balloon to stop rising and float on top of the atmosphere. I talked about the atmosphere giving way to the interplanetary medium, so I think it is quite clear that I understand what is going on... --Tango (talk) 03:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Actually, the atmosphere has an ill-defined end; it gets infinitessimally thinner as you keep going out from the earth. This does NOT mean that it has no end; to assume it never ends is to make the same error that is made in Xeno's paradoxes. (See discussion elsewhere at the ref desk on this). Eventually, the matter density of the atmosphere fades to match the average matter density of the rest of the so-called "empty space" of the rest of the solar system. At that point, we can say that the atmosphere has ended, since it has become indistinguishable from space. That line can be clearly drawn around the earth, so there is no point in saying it "never" ends. The atmosphere is a physical example of a convergent infinite series, and the operative part here is "convergent". The limit where the diminishing atmosphere converges with the rest of space we can say the atmosphere ends. --Jayron32.talk.contribs 03:06, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

Falling for infinitly long.

Since I was learning about terminal velocity I was wondering that would it be physically possible for an object to have a terminal velocity greater than c. If it were a point object such that A was very small, falling through an low density fluid with a low drag coefficient, and a great enough mass. If this were possible (albeit physically it would take a long time to attain it; imagine it falling through an infintly long tube), would that mean that as v--> c, the mass would go to zero. Such that its K(e) would never exceed E=mc2. Or would the mass remain the same given that E2=(mc2)2+(pc)2. Using the second equation E could increase without bound? I would imagine a vacuum would have a drag coefficient of zero, this would make terminal velocity infinite, although a perfect vaccum is impossible. —Preceding unsigned comment added by 24.171.145.63 (talk) 21:16, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- The short answer is "no". I think we have an article, relativistic addition of velocities or some such? If not, it should redirect somewhere.

- Things are a bit more complicated if you consider the large-scale geometry of the universe -- see observable universe. One way of expressing the edge of the observable universe is that it's where galaxies are moving away from us faster than c. --Trovatore (talk) 21:20, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Off topic, but the volume beyond which the recession speed exceeds c is called the Hubble volume and is smaller than the visible universe. The recession speed at the edge of the visible universe is around 3.3c. -- BenRG (talk) 17:12, 6 June 2009 (UTC)

- Why would the mass go to zero? Rest mass is always the same, irrespective of velocity. Relativistic mass increases as velocity increases. The total energy of a moving object is the sum of the rest energy, mc2 (where m is the rest mass), and the kinetic energy (for small velocities that's mv2/2, for velocities near the speed of light you need to use relativity). The rest energy is constant, the kinetic energy increases with velocity (and increases without bound, even though the velocity is bounded above by the speed of light). --Tango (talk) 01:38, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

A structural designation

When listing or describing archictectural structures what does HEW (insert number here) mean e.g. HEW 365, which is for the Gasworks Railway Tunnel around Kings Cross in London? Simply south (talk) 22:20, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- I think it is the Panel for Historical Engineering Works designation; and think said panel is part of or connected with the Institution of Civil Engineers. See, for instance, the introduction to London and the Thames Valley, by Denis Smith, Institution of Civil Engineers (Great Britain), and then note that the book lists HEW numbers against each structure described. --Tagishsimon (talk) 22:33, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- See also ICE overview of PHEW and a PHEW database with a crappy user interface --Tagishsimon (talk) 22:36, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- Thank you for that. Simply south (talk) 23:17, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- See also ICE overview of PHEW and a PHEW database with a crappy user interface --Tagishsimon (talk) 22:36, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

Understand weak interaction and beta decay

I tried long to understand how a force could result in β decay.

As for my knowledge I usually think of a force as a vectors (or a vector field if we speak of fields): electric force between 2 charges as 2 vectors with the same direction, the same for gravitational force, and I think I could do the same for strong force. But when I read of weak force and its role in β decay, first I see only feynman diagrams, which I understand, but I cannot fit them with my idea of vectors. Second I see only one particle interacts with this force, when for all of the other forces there are at least 2 particles, or a field and a particle.

I conclude saying that I think I understand the basic mechanism of β- decay. So, said in really raw words: a neutron emits (on its own or there is a reason?) a W- boson, which "extracts" one unit of negative electric charge from the neutron, and the neutron is transformed in a proton. Then the W- boson decays in an electron and an electron antineutrino.

Could someone help me and clean my doubts?

ColOfAbRiX (talk) 23:56, 4 June 2009 (UTC)

- You said you see only one particle interacting in the beta decay, but when you gave us an example of beta decay you mentioned a neutron, a proton, a W-, an electron and an anti-neutrino. I count five different particles. Even if we exclude the W which plays the role of the "force" here, you still have four interacting particles. Forget about vectors, they won't help you here. You should think of "forces" as interactions between different fields ()The vertices of the Feynman diagrams. Dauto (talk) 01:19, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

June 5

Distribution of stellar classes

According to the table in Harvard spectral classification, stars of spectral class M comprise over ~76% of all main sequence stars while Sun-like stars in spectral class G comprise ~7.6% of all main sequence stars. This suggests to me that class M stars outnumber class G stars by a ratio of 10:1. My own OR suggests that is roughly true within 20 light years of the Sun, but is that ratio maintained throughout the Milky Way galaxy? Presumably similar ratios can be calculated for other spectral classes as well - I am particularly interested if some parts of the Galaxy are lacking in stars a particular spectral class. Astronaut (talk) 00:10, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- I think the ratio is maintained on a large scale (presumably universally, although I'm not sure how much evidence there is to support that). I'm not sure about the distribution of different spectral classes throughout the galaxy, but there are certainly differences in the metallicity of stars in different areas (that article explains it fully). --Tango (talk) 01:32, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- I saw the metallicity article, but I'm not convinced there is a strong link between metallicity and spectral class, and anyway I'm really only interested in stars in the Milky Way disc. The kind of thing I'm trying to find out is if, for example, we observed that the population density of O and B class stars in the spiral arms was typically double that in the regions between the spiral arms, could we assume the same was true of the population density of G, K and M class stars, even though we cannot observe them directly? In other words, can I use the distribution of bright stars that can be observed at great distances, to reliably infer the existance of a much larger population of dim stars at these great distances? Astronaut (talk) 04:39, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- I don't think you can do that because the O class stars are short lived (less than 10 million years) and won't have enough time to move very far from the star nursery where they are born, while smaller stars can live much longer and will have a more uniforme spacial distribution. Dauto (talk) 06:43, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- One factor in variation of star population is related to the size of the galactic body they are in. Globular clusters are known to lose stars through a process analogous to (and actually called by some) "evaporation". The lighter stars in the cluster are the most "volatile" since they will gain the highest velocities in energy exchange interactions with other stars. Globular clusters thus tend to have a relative poverty of K and M-type stars since these will be the first to achieve escape velocities. SpinningSpark 13:08, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

- Two important keywords for this type of question are the initial mass function (IMF) and the star formation history, and it's the latter that chiefly determines the current distribution of stellar types in a given stellar population. Starting from the IMF, an assumption about the star formation history and using stellar evolution models, one can try to model the stellar populations in various environments of the Milky Way, but also in other galaxies. Obviously, while in the Milky Way one can make a tally of individual stars, in other galaxies one only has a limited amount of information, like the colours of galaxies or integrated spectra. What a population of stars in a given area looks like at a given point in time thus depends on both the IMF and the star formation history. From modelling this sort of information one can then try to reconstruct these two factors. I'm far from being an expert in this, but my impression is that the IMF is fairly universal. There are indeed different versions that have been tried and which vary in particular at the low mass end, i.e. at late spectral types, but that controversy seems to be due more to our ignorance rather than variation in different environments. The star formation history is much more variable. Early-type stars, O and B, say, are very short-lived and can only exist in environments where stars are currently being formed. If you switch off star formation (e.g. by removing cold gas) these stars will disappear very quickly and you'll be left with a population that is dominated by late-type stars, main-sequence stars dominating by number, and red giants dominating the light output. The neighbourhood of the sun is in the disk of the Milky Way which is still forming stars, hence we might expect some early-type stars (typically forming OB associations). The bulge forms much less stars and is therefore dominated by later-type stars. The extreme cases would be "red and dead" elliptical galaxies. --Wrongfilter (talk) 16:24, 5 June 2009 (UTC)

Q about lovebirds

Is it true that it's impossible to keep one lovebird as a pet? Is it also true that if you have two lovebirds and one of them dies, then the other one will become depressed, stop eating and die soon after? Thanks. --84.67.12.110 (talk) 00:13, 5 June 2009 (UTC)