Korean War: Difference between revisions

Surv1v4l1st (talk | contribs) m Spelling. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

The [[right-wing]] [[Representative Democratic Council]], led by nationalist [[Syngman Rhee]], opposed the Soviet–American trusteeship of Korea, arguing that after thirty-five years (1910–45) of Japanese [[colonialism|colonial rule]]—''foreign rule''—most Koreans opposed another foreign rule, i.e. US and Soviet. Gaining advantage from the native political temper, the US quit the Soviet-supported [[Moscow Accords]]—and, using the 31 March 1948 [[United Nations]] election deadline to achieve a [[anti-communist]] civil government in the US Korean Zone of Occupation—convoked national general elections that the Soviets opposed, then boycotted, insisting that the US honor the Moscow Accords.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|26}}<ref>{{cite news |first= |last= |coauthors= |title= For Freedom|curly=y |work= TIME|page= |date= 20 May 1946|accessdate=2008-12-10|quote= Rightist groups in the American zone, loosely amalgamated in the Representative Democratic Council under elder statesman Syngman Rhee, protested heatedly ...|url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,792877-1,00.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://myhome.shinbiro.com/~mss1/failure.html|title= The Failure of Trusteeship|accessdate=2008-12-10 |work= infoKorea|publisher= |date= }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.mcn.org/e/iii/politics/asian_war/korea_truman_notes.html|title= Korea Notes from Memoirs by Harry S. Truman|accessdate=2008-12-10 |work= The US War Against Asia (notes)|publisher=III Publishing |date= |quote=U.S. proposed general elections (U.S. style) but Russia insisted on Moscow Agreement. }}</ref> |

The [[right-wing]] [[Representative Democratic Council]], led by nationalist [[Syngman Rhee]], opposed the Soviet–American trusteeship of Korea, arguing that after thirty-five years (1910–45) of Japanese [[colonialism|colonial rule]]—''foreign rule''—most Koreans opposed another foreign rule, i.e. US and Soviet. Gaining advantage from the native political temper, the US quit the Soviet-supported [[Moscow Accords]]—and, using the 31 March 1948 [[United Nations]] election deadline to achieve a [[anti-communist]] civil government in the US Korean Zone of Occupation—convoked national general elections that the Soviets opposed, then boycotted, insisting that the US honor the Moscow Accords.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|26}}<ref>{{cite news |first= |last= |coauthors= |title= For Freedom|curly=y |work= TIME|page= |date= 20 May 1946|accessdate=2008-12-10|quote= Rightist groups in the American zone, loosely amalgamated in the Representative Democratic Council under elder statesman Syngman Rhee, protested heatedly ...|url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,792877-1,00.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://myhome.shinbiro.com/~mss1/failure.html|title= The Failure of Trusteeship|accessdate=2008-12-10 |work= infoKorea|publisher= |date= }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.mcn.org/e/iii/politics/asian_war/korea_truman_notes.html|title= Korea Notes from Memoirs by Harry S. Truman|accessdate=2008-12-10 |work= The US War Against Asia (notes)|publisher=III Publishing |date= |quote=U.S. proposed general elections (U.S. style) but Russia insisted on Moscow Agreement. }}</ref> |

||

The resultant anti-communist South Korean government promulgated a national political constitution (17 July 1948) elected a president, the American-educated [[strongman (politics)|strongman]] Syngman Rhee (20 July 1948), and established the [[South Korea|Republic of South Korea]] on 15 August 1948.<ref name = "MacroHistory">{{cite web | title =The Korean War, The US and Soviet Union in Korea | publisher =MacroHistory | url = http://www.fsmitha.com/h2/ch24kor.html | accessdate =2007-08-19 }}</ref> Likewise, in the Russian Korean Zone of Occupation, the USSR established a [[Communism|Communist]] North Korean government<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|26}} led by |

The resultant anti-communist South Korean government promulgated a national political constitution (17 July 1948) elected a president, the American-educated [[strongman (politics)|strongman]] Syngman Rhee (20 July 1948), and established the [[South Korea|Republic of South Korea]] on 15 August 1948.<ref name = "MacroHistory">{{cite web | title =The Korean War, The US and Soviet Union in Korea | publisher =MacroHistory | url = http://www.fsmitha.com/h2/ch24kor.html | accessdate =2007-08-19 }}</ref> Likewise, in the Russian Korean Zone of Occupation, the USSR established a [[Communism|Communist]] North Korean government<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|26}} led by [[Kim Il-sung]].<ref name = "AMH" /> Moreover, President Rhee's régime expelled communists and [[leftist]]s from southern national politics. Disenfranchised, they headed for the hills, to prepare guerrilla war against the US-sponsored ROK Government.<ref name = "AMH" /> |

||

As [[Korean nationalism|nationalists]], both Syngman Rhee and Kim Il-Sung were intent upon reunifying Korea under their own political system.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|27}} Partly because they were the better-armed, the North Koreans could escalate the continual border skirmishes and raids, and then invade—with proper provocation—whereas South Korea, with limited US material could not match them.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|27}} During this era of the beginning [[Cold War]], the US government acted as if all communists—regardless of nationality—constituted a [[Communist bloc]] controlled or at least directly influenced from Moscow; thus the US portrayed the [[civil war]] in Korea as a Soviet [[hegemony|hegemonic]] maneuver. |

As [[Korean nationalism|nationalists]], both Syngman Rhee and Kim Il-Sung were intent upon reunifying Korea under their own political system.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|27}} Partly because they were the better-armed, the North Koreans could escalate the continual border skirmishes and raids, and then invade—with proper provocation—whereas South Korea, with limited US material could not match them.<ref name="Stokesbury1990"/>{{rp|27}} During this era of the beginning [[Cold War]], the US government acted as if all communists—regardless of nationality—constituted a [[Communist bloc]] controlled or at least directly influenced from Moscow; thus the US portrayed the [[civil war]] in Korea as a Soviet [[hegemony|hegemonic]] maneuver. |

||

Revision as of 05:14, 19 November 2009

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Template:FixBunching Template:Korean War Infobox Template:FixBunching

The Korean War is a war between North Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea, ROK) that started on 25 June 1950 and paused with an armistice signed 27 July, 1953. To date, the war has not been officially ended through treaty, and occasional skirmishes have been reported in the border region.

The Korean peninsula was politically divided as a legacy of the geopolitics of defeating the Japanese Empire on the peninsula in 1945. Soviet forces fighting the Japanese advanced up to the 38th Parallel, which later became the political border between the two Koreas. Despite talks in the months preceding open warfare, continual cross-border skirmishes and raids at the 38th Parallel, and the political frustration of failed all-Korea elections in 1948, escalated to warfare.[1] The reunification negotiations ceased when North Korea invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950.[2]

The United States and the United Nations intervened on the side of the South. After a rapid UN counteroffensive that repelled North Koreans past the 38th Parallel and almost to the Yalu River, the People's Republic of China (PRC) came to the aid of the North.[2] With the PRC's entry into the conflict, the fighting eventually ceased with an armistice that restored the original border between the Koreas at the 38th Parallel and created the Korean Demilitarized Zone, a 2.5 mile wide buffer zone between the two Koreas. North Korea unilaterally withdrew from the armistice on 27 May 2009, thus returning to a de facto state of war; as of this date, only a small naval skirmish has occurred.[3] [4]

During the war, both North and South Korea were sponsored by external powers, thus facilitating the war's metamorphosis from a simple civil war to a proxy war between powers involved in the larger Cold War.

From a military science perspective, the Korean War combined strategies and tactics of World War I and World War II — swift infantry attacks followed by air bombing raids. The initial mobile campaign transitioned to trench warfare, lasting from January 1951 until the 1953 border stalemate and armistice.

Background

Terminology

In the US, the war was officially described as a police action owing to the lack of a legitimate declaration of war by the US Congress. Colloquially, it has also been referred to in the United States as The Forgotten War and The Unknown War, because it was ostensibly a United Nations conflict, ended in stalemate, had fewer American casualties, and concerned issues much less clear than in previous and subsequent conflicts, such as the Second World War and the Vietnam War.[5][6]

In South Korea the war is usually referred to as the 6-2-5 War (yuk-i-o jeonjaeng), reflecting the date of its commencement on June 25.

In North Korea the war is officially referred to as the Choguk haebang chǒnjaeng ("fatherland liberation war"). Alternately, it is called the Chosǒn chǒnjaeng ("Joseon war", Joseon being what North Koreans call Korea).

In the People's Republic of China the war is officially called the Chao Xian Zhan Zheng (Korean War), with the word "Chao Xian" referring to Korea in general, and officially North Korea.

The term Korean War can also denote the skirmishes before the invasion and since the armistice.[7]

Japanese rule (1910–1945)

Upon defeating Qing Dynasty China in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–96), the Empire of Japan occupied the Korean Empire (1897–1910) of Emperor Gojong—a peninsula strategic to its sphere of influence.[8] A decade later, on defeating Imperial Russia in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), Japan made Korea its protectorate, with the Eulsa Treaty in 1905, then annexed it with the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty in 1910.[9][10]

Korean nationalists and the intelligentsia fled the country, and some founded the Provisional Korean Government, headed by Syngman Rhee, in Shanghai, in 1919, that proved a “government-in-exile” recognized by few countries. From 1919 to 1925 and onwards, Korean communists led internal and external warfare against the Japanese.[8]: 23 [11]

Korea under Japanese rule was considered to be part of the Empire of Japan along with Taiwan, which was part of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere and was an industrialized colony; in 1937, the colonial Governor–General, General Minami Jiro, commanded the cultural assimilation to Japan of the colony's 23.5 million people—by banning Korean language, literature, and culture, replaced with that of the Japanese, and that the populace rename themselves as Japanese. In 1938, the Colonial Government established labor conscription; by 1939, 2.6 million Koreans worked overseas as forced laborers; by 1942, Korean men were being conscripted to the Japanese Army.

Meanwhile, in China, the nationalist National Revolutionary Army and the Communist People's Liberation Army organized the (right-wing and left-wing) refugee Korean patriots. The Nationalists, led by Yi Pom-Sok, fought in the Burma Campaign (December 1941 – August 1945). The communists, led by Kim Il-sung, fought the Japanese in Korea.

During World War II, Japanese utilized Korea's food, livestock, and metals for the war effort. Japanese forces in Korea increased from 46,000 (1941) to 300,000 (1945) soldiers. Japanese Korea conscripted 2.6 million forced laborers controlled with a collaborationist Korean police force; some 723,000 people had been sent to work in the overseas empire and in metropolitan Japan. By January 1945, Koreans were 32% of Japan’s labor force; in August 1945, when the US dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, they were about 25% of the people killed.[11] Japanese rule in Korea and Taiwan was not recognized by other world powers at the end of the war.

The US-Soviet division of Korea excluded the Koreans—who were represented by US Army colonels Dean Rusk and Charles Bonesteel.[12] Two years earlier, at the Cairo Conference (November 1943), Nationalist China, the UK, and the USA decided that Korea should become independent, “in due course”; Stalin concurred. In February 1945, at the Yalta Conference, the Allies failed to establish the Korean trusteeship first discussed in 1943 by U.S. President Roosevelt and UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Per the US-Soviet agreement, the USSR declared war against Japan on 9 August 1945, and, by 10 August, the Red Army occupied the Korean north, via amphibious landings north of the 38th parallel and its Twenty-Fifth Army entering from Manchuria, China.[11][13] Some three weeks later, on 8 September 1945, Lt. Gen. John R. Hodge, USA, arrived in Incheon to accept the Japanese surrender south of the 38th parallel.[14]

Korea divided (1945)

At the Potsdam Conference (July–August 1945), the Allies unilaterally decided to divide Korea—without consulting the Koreans—in contradiction of the Cairo Conference (November 1943) where Churchill, Chiang Kai-shek, and Franklin D. Roosevelt declared that Korea would be a free nation and an independent country.[8][8][8]: 24 [14]: 24–25 [15]: 25 [16] Moreover, the earlier Yalta Conference (February 1945) granted to Joseph Stalin European "buffer zones"—satellite states accountable to Moscow- as well as an expected Soviet pre-eminence in China and Manchuria,[17] as reward for joining the US Pacific war effort against Japan.[17]

By 10 August, the Red Army occupied the northern part of the peninsula as agreed, and on 26 August halted at the 38th parallel for three weeks to await the arrival of US forces in the south.[8]: 25 [8]: 24

On 10 August 1945, with the 15 August Japanese surrender near, the Americans were in doubt that the Soviets would honor their part of the Joint Commission, the US-sponsored Korean occupation agreement. A month earlier, to fulfill the politico-military requirements of the US, Colonel Dean Rusk and Colonel Charles Bonesteel III, divided the Korean peninsula at the 38th parallel after hurriedly deciding (in thirty minutes), that the US Korean Zone of Occupation had to have a minimum of two ports.[14][18][19][20] Explaining why the occupation zone demarcation (38th parallel) was so far south, Rusk observed, “even though it was further north than could be realistically reached by US forces, in the event of Soviet disagreement ... we felt it important to include the capital of Korea in the area of responsibility of American troops”, especially when “faced with the scarcity of US forces immediately available, and time and space factors, which would make it difficult to reach very far north, before Soviet troops could enter the area.”[17] The Soviets agreed to the US occupation zone demarcation, to improve Soviet Eastern European-occupation negotiation-leverage, and because each would accept Japanese surrender where they stood.[8]: 25

As the military governor, General John R. Hodge directly controlled South Korea via the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGIK 1945–48).[21]: 63 He established control by first restoring to power the key Japanese colonial administrators and their Korean and police collaborators,[1] and second, by refusing the USAMGIK’s official recognition of the People's Republic of Korea (PRK) (August–September 1945), the provisional government (agreed with the Japanese Army) with which the Koreans had been governing themselves and the peninsula—because he suspected it was communist. These US policies, voiding popular Korean sovereignty, provoked the civil insurrections and guerrilla warfare preceding, then constituting, the Korean civil war.[9] On 3 September 1945, Lieutenant General Yoshio Kozuki, Commander, Japanese 17th Area Army , contacted Hodge, telling him that the Soviets were south of the 38th parallel at Kaesong. Hodge trusted the accuracy of the Japanese Army report.[14]

In December 1945, Korea was administered by the US–USSR Joint Commission, agreed at the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers (October 1945). Again excluding the Koreans, the commission decided the country would become independent after a five-year trusteeship—action facilitated by each régime sharing its sponsor's ideology.[8]: 25–26 [22] The incensed Korean populace revolted; in the South, some protested, some rose in arms;[9] to contain them, the USAMGIK banned strikes (8 December 1945) and outlawed the PRK Revolutionary Government and the PRK People's Committees on 12 December 1945.

This suppression of sovereignty provoked an 8,000-railroad-worker strike on 23 September 1946 in Pusan, political action which quickly extended throughout US-controlled Korea; the USAMGIK had lost civil control. On 1 October 1946, Korean police killed three students in the “Daegu Uprising”; people counter-attacked, killing 38 policemen. Likewise, on 3 October, some 10,000 people attacked the Yeongcheon police station, killing three policemen and injuring some 40 more; elsewhere, populaces killed some 20 landlords and pro-Japanese South Korean officials.[15] The USAMGIK declared martial law to control South Korea; in controlling the Koreans with Japanese colonial administrators and Korean collaborators, the US discredited its declarations of a “Free Korea”.[citation needed]

The right-wing Representative Democratic Council, led by nationalist Syngman Rhee, opposed the Soviet–American trusteeship of Korea, arguing that after thirty-five years (1910–45) of Japanese colonial rule—foreign rule—most Koreans opposed another foreign rule, i.e. US and Soviet. Gaining advantage from the native political temper, the US quit the Soviet-supported Moscow Accords—and, using the 31 March 1948 United Nations election deadline to achieve a anti-communist civil government in the US Korean Zone of Occupation—convoked national general elections that the Soviets opposed, then boycotted, insisting that the US honor the Moscow Accords.[8]: 26 [23][24][25]

The resultant anti-communist South Korean government promulgated a national political constitution (17 July 1948) elected a president, the American-educated strongman Syngman Rhee (20 July 1948), and established the Republic of South Korea on 15 August 1948.[26] Likewise, in the Russian Korean Zone of Occupation, the USSR established a Communist North Korean government[8]: 26 led by Kim Il-sung.[7] Moreover, President Rhee's régime expelled communists and leftists from southern national politics. Disenfranchised, they headed for the hills, to prepare guerrilla war against the US-sponsored ROK Government.[7]

As nationalists, both Syngman Rhee and Kim Il-Sung were intent upon reunifying Korea under their own political system.[8]: 27 Partly because they were the better-armed, the North Koreans could escalate the continual border skirmishes and raids, and then invade—with proper provocation—whereas South Korea, with limited US material could not match them.[8]: 27 During this era of the beginning Cold War, the US government acted as if all communists—regardless of nationality—constituted a Communist bloc controlled or at least directly influenced from Moscow; thus the US portrayed the civil war in Korea as a Soviet hegemonic maneuver.

U.S. troops withdrew from Korea in 1949,[27] leaving the South Korean army relatively ill-equipped. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union sent large amounts of military aid to North Korea to facilitate the invasion planned by Kim Il-Sung.

Course of the war

North Korea invades (June 1950)

This section possibly contains unsourced predictions, speculative material, or accounts of events that might not occur. Information must be verifiable and based on reliable published sources. (August 2008) |

Although the United Nations received messages that the North Koreans were about to invade, all were rejected. The United States received less than two weeks notice of the Korean War—the Chinese-authorized, North Korean invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950. The CIA provided the early notice; before the war, in early 1950, CIA China station officer Douglas Mackiernan had got Chinese and North Korean intelligence forecasting the summer KPA invasion of the South. Earlier, after the US missions had left the communist People's Republic of China, he volunteered to remain and get the intelligence. Afterwards, he and a team of CIA local mercenaries then escaped the Chinese, in a months-long horse trek across the Himalaya mountains; he was killed within miles of Lhasa, Tibet — yet his team delivered the intelligence to headquarters. Thirteen days later, the North Korean People's Army (KPA) crossed the 38th-parallel border and invaded South Korea. Mackiernan was posthumously awarded the CIA Intelligence Star for valor.[28]

Under the guise of counter-attacking a South Korean provocation raid, the North Korean Army (KPA) crossed the 38th parallel, behind artillery fire, at Sunday dawn of 25 June 1950.[8]: 14 The KPA said that Republic of Korea Army (ROK Army) troops, under command of the régime of the "bandit traitor Syngman Rhee", had crossed the border first—and that they would arrest and execute Rhee.[14] In the past year, both Korean armies had continually harassed each other with skirmishes—and each continually raided the other country across the 38th-parallel border, as in a civil war.

Hours later, the United Nations Security Council unanimously condemned the North Korean invasion of the Republic of South Korea (ROK), with UNSC Resolution 82, so adopted despite the USSR, a veto-wielding power, boycotting the Council meetings since January—protesting that the (Taiwan) Republic of China, and not the (mainland) People's Republic of China held a permanent seat in the UN Security Council.[29] On 27 June 1950, President Truman ordered US air and sea forces to help the South Korean régime. After debating the matter, the Security Council, on 27 June 1950, published Resolution 83 recommending member-state military assistance to the Republic of Korea. Incidentally, while awaiting the Council's fait accompli announcement to the UN, the Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister accused the US of starting armed intervention in behalf of South Korea.[30]

The USSR challenged the legitimacy of the UN-approved war, because (i) the ROK Army intelligence upon which Resolution 83 is based came from US Intelligence; (ii) North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) was not invited as a sitting temporary member of the UN, which violated UN Charter Article 32; and (iii) the Korean warfare was beyond UN Charter scope, because the initial North–South border fighting was classed as civil war. Moreover, the Soviet representative boycotted the UN to prevent Security Council action, to challenge the legitimacy of UN action; legal scholars posited that deciding upon an "action" required the unanimous vote of the five permanent members.[31][32]

The North Korean Army launched the "Fatherland Liberation War" with a comprehensive air–land invasion using 231,000 soldiers, who captured scheduled objectives and territory—among them, Kaesŏng, Chuncheon, Uijeongbu, and Ongjin—which they achieved with 274 T-34-85 tanks, some 150 Yak fighters, 110 attack bombers, 200 artillery pieces, 78 Yak trainers, and 35 reconnaissance aircraft.[14] Additional to the invasion force, the KPA had 114 fighters, 78 bombers, 105 T-34-85 tanks, and some 30,000 soldiers stationed in North Korea.[14] At sea, although comprising only several small warships, the North Korean and South Korean navies fought in the war as sea-borne artillery for their in-country armies.

In contrast, the ROK Army defenders were unprepared. In South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu (1998), R.E. Applebaum reports the ROK forces' low combat readiness on 25 June 1950. The ROK Army had 98,000 soldiers (65,000 combat, 33,000 support), no tanks, and a twenty-two piece air force comprising 12 liaison-type and 10 AT6 advanced-trainer airplanes. There were no large foreign military garrisons in Korea at invasion time—but there were large US garrisons and air forces in Japan.[14]

Within days of the invasion, masses of ROK Army soldiers—of dubious loyalty to the Syngman Rhee régime—either were retreating southwards or were defecting en masse to the Communist North, to the KPA.[8]: 23

Police Action: US intervention

Despite the rapid post–Second World War Allied demobilizations, there were substantial US forces occupying Japan; under Gen. MacArthur’s command, they could fight the North Koreans.[8]: 42 Moreover, in that time and place, besides the US, only the British Commonwealth had comparable forces.

On Saturday, June 24, 1950, US Secretary of State Dean Acheson telephonically informed President Harry S. Truman, “Mr. President, I have very serious news. The North Koreans have invaded South Korea.”[33][34] Truman and Acheson discussed a US invasion response with defense department principals, who agreed that the United States was obligated to repel military aggression, paralleling it with Adolf Hitler's 1930s aggressions, and said that the mistake of appeasement must not be repeated.[35] President Truman acknowledged that fighting the invasion was pertinent to the American global containment of communism:

"Communism was acting in Korea, just as Hitler, Mussolini and the Japanese had ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier. I felt certain that if South Korea was allowed to fall Communist leaders would be emboldened to override nations closer to our own shores. If the Communists were permitted to force their way into the Republic of Korea without opposition from the free world, no small nation would have the courage to resist threat and aggression by stronger Communist neighbors."[36]

President Harry S. Truman announced that the US would counter "unprovoked aggression" and "vigorously support the effort of the [UN] security council to terminate this serious breach of peace."[37] In Congress, the Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman, Gen. Omar Bradley warned against appeasement, saying that Korea was the place "for drawing the line" against communist expansion. In August 1950, the President and the Secretary of State easily persuaded the Congress to appropriate $12 billion to pay for the additional Asian military expenses essential to the goals of National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68), the American global containment of communism.[37]

Per State Secretary Acheson's recommendation, President Truman ordered Gen. MacArthur to transfer materiel to the Army of the Republic of Korea (ROK Army) while giving air cover to the evacuation of US nationals. Moreover, the President disagreed with his advisors recommending unilateral US bombing of the North Korean forces, but did order the US Seventh Fleet to protect Taiwan (Chiang Kai-Shek's China), whose Nationalist Government (confined to Formosa island) asked to fight in Korea. The US denied the Nationalist Chinese request for combat—lest it provoke a communist Chinese intervention.[38]

The Battle of Osan was the first significant USA–KPA fighting in the Korean War, by the 540-Soldier Task Force Smith, which was a small forward element of the 24th Infantry Division based in Japan.[8]: 45 On 5 July 1950, Task Force Smith attacked the North Koreans at Osan but without weapons capable of destroying the North Korean's tanks, they were unsuccessful, resulting in 180 dead, wounded or taken prisoner. The KPA progressed southwards, forcing the 24th Division's retreat to Taejeon, which the KPA also captured;[8]: 48 the 24th Division suffered 3,602 dead-wounded and 2,962 captured GIs—including the Division’s Commander, Maj. Gen. William F. Dean.[8]: 48 Overhead, the KPAF shot down 18 USAF fighters and 29 bombers; the USAF shot down 5 KPAF fighters.

By August, the KPA had pushed back the ROK Army and the US Eighth Army to the Pusan city vicinity, in southeast Korea.[8]: 53 In their southward advance, the KPA purged the Republic of Korea's intelligentsia, by killing civil servants and intellectuals.[8]: 56 On 20 August, Gen. MacArthur warned North Korean Leader Kim Il-Sung that he was responsible for the KPA’s atrocities.[8][26]: 56 By September, the UN Command controlled only the Pusan city perimeter, about 10% of Korea. Only on being reinforced, re-equipped, and with naval artillery and air force bombing support, could the UN Command forces stand at the Nakdong River. In US military history, this "back-against-the-sea" holding action is known as the "Pusan Perimeter".

Escalation

In the desperate Battle of Pusan Perimeter (August–September 1950), the US Army withstood KPA attacks meant to capture the city. Soon, the USAF interrupted KPA logistics with 40 daily ground-support sorties that destroyed 32 bridges, halting most daytime road and rail traffic, which hid in tunnels and moved only at night.[8]: 47–48 [8]: 66 To deny materiel to the KPA, the USAF destroyed logistics depots, petroleum refineries, and harbors, while the US Navy air forces attacked transport hubs, consequently, the over-extended KPA could not be supplied throughout the peninsular south.[8]: 58

Meanwhile, US garrisons in Japan continually dispatched soldiers and material to reinforce the Pusan Perimeter.[8]: 59–60 Tank battalions deployed to Korea from San Francisco (in the continental US); by late August, the Pusan Perimeter had some 500 medium tanks.[8]: 61 In early September 1950, ROK Army and UN Command forces were prepared—they out-numbered the KPA 180,000 to 100,000 soldiers, and then counterattacked.[8][14]: 61

Battle of Incheon

Against the rested and re-armed Pusan Perimeter defenders and their reinforcements, the KPA were under-manned and poorly supplied; unlike the UN Command, they lacked naval and air support.[8]: 61 [8]: 58 To relieve the Pusan Perimeter, the UN CIC, Gen. MacArthur, recommended an amphibious landing at Incheon, behind the KPA lines.[8]: 67 On 6 July, he ordered Maj. Gen. Hobart Gay, Commander, 1st Cavalry Division, to plan the division's amphibious landing at Incheon; on 12–14 July, the 1st Cavalry Division embarked from Yokohama to reinforce the 24th Infantry Division.[39]

The Operation Chromite amphibious assault of Incheon deployed in violent tides, and was awaited by a strong, entrenched enemy.[8]: 66–67 Soon after the war began, Gen. MacArthur had begun planning the matter, but the Pentagon opposed him.[8]: 67 When authorized, he activated his attack USA-USMC-ROKA force—the X Corps, Gen. Edward Almond, Commander, composed of 70,000 1st Marine Division infantry; the 7th Infantry Division; and some 8,600 ROK Army soldiers.[8]: 68 By the 15 September attack date, the assault force faced few, but tenacious, KPA defenders at Incheon; military intelligence, psychological operations, guerrilla reconnaissance, and protracted bombardment facilitated a relatively light battle between the US–ROK and the KPA; however, the bombardment destroyed most of Incheon city.[8]: 70

The Incheon landing allowed the 1st Cavalry Division to begin its northward fighting from the Pusan Perimeter. “Task Force Lynch”—3rd Bn, 7th Cav Rgt, and two 70th Tank Bn units (Charlie Company and the Intelligence–Reconnaissance Platoon)—effected the “Pusan Perimeter Breakout” through 106.4 miles of enemy territory to join the 7th Infantry Division, at Osan. [1] The X Corps rapidly defeated the KPA defenders, thus threatening to trap the main KPA force in South Korea;[8]: 71–72 Gen. MacArthur quickly recaptured Seoul;[8]: 77 and the almost-isolated KPA rapidly retreated north; only 25,000 to 30,000 soldiers surviving.[40][41]

The UN Offensive: North Korea invaded (September–October 1950)

On 1 October 1950, the UN Command repelled the KPA northwards, past the 38th parallel; the ROK Army crossed after them, into North Korea.[8]: 79–94 Six days later, on 7 October, with UN authorization, the UN Command forces followed the ROK forces northwards.[8]: 81 The X Corps landed at Wonsan (SE North Korea) and Iwon (NE North Korea), already captured by ROK forces.[8]: 87–88 The Eighth US Army and the ROK Army drove up western Korea, and captured Pyongyang city, the North Korean capital, on 19 October 1950.[8]: 90 At month’s end, UN forces held 135,000 KPA prisoners of war; the North Korean People’s Army appeared to disintegrate.

Taking advantage of the UN Command’s strategic momentum against the KPA, Gen. MacArthur (and some US politicians),[who?] believed it necessary to extend the Korean War into Communist China to destroy the PRC depots supplying the North Korean war effort. President Truman disagreed, and ordered Gen. MacArthur’s caution at the Sino-Korean border.[8]: 83

China intervenes

On 27 June 1950, two days after the KPA invaded and three months before the October Chinese intervention to the Korean War, President Truman dispatched the 7th US Fleet to the Taiwan Straits, to protect Nationalist Republic of China from the People’s Republic of China (PRC).[42] On 4 August 1950, Mao Zedong reported to the Politburo that he would intervene when the People's Volunteer Army (PVA) was ready to deploy. On 20 August 1950, Premier Zhou Enlai informed the United Nations that “Korea is China’s neighbor ... The Chinese people cannot but be concerned about a solution of the Korean question”—thus, via neutral-country diplomats, China warned the US, that in safeguarding Chinese national security, they would intervene against the UN Command in Korea.[8]: 83 President Truman interpreted the communication as “a bald attempt to blackmail the UN”, and dismissed it.[43] The Politburo authorized Chinese intervention in Korea on 2 October 1950—the day after the ROK Army crossed the 38th-parallel border.[44] Later, the Chinese claimed that US bombers had violated PRC national airspace when on en route to bomb North Korea—before China intervened.[45]

In September, in Moscow, PRC Premier Zhou Enlai added diplomatic and personal force to Mao’s cables to Stalin, requesting military assistance and material. Stalin delayed; Mao re-scheduled launching the “War to Resist America and Aid Korea” from the 13th to the 19th of October 1950. Moreover, the USSR limited their assistance to air support no closer than 60 miles (100 km) from the battlefront—because Soviet pilots were to fight in the air war to gain experience against the Western air forces; they would be flying MiG-15s (camouflaged as PRC Air Force), and seriously challenged the UN air forces for battlefield air superiority.[citation needed]

On 8 October 1950, the day after the US’s northward crossing of the 38th-parallel border into North Korea, Mao Zedong ordered the People's Liberation Army's North East Frontier Force to be reorganized into the Chinese People's Volunteer Army,[46] who were to fight the “War to Resist America and Aid Korea”. The Soviet materiel would make the Chinese intervention to Korea a strategic maneuver furthering Asian communist revolutionary power, [citation needed] Mao explained to Stalin: “If we allow the United States to occupy all of Korea, Korean revolutionary power will suffer a fundamental defeat, and the American invaders will run more rampant, and have negative effects for the entire Far East.”

US aerial reconnaissance had difficulty sighting PVA units in daytime, because their march and bivouac discipline minimized aerial detection.[8]: 102 The PVA marched “dark-to-dark” (19:00–03:00hrs), and aerial camouflage (concealing soldiers, pack animals, and equipment) was deployed by 05:30hrs. Meanwhile, daylight advance parties scouted for the next bivouac site. During daylight activity or marching, soldiers were to remain motionless if an aircraft appeared, until it flew away;[8]: 102 PVA officers might shoot security violators.[14] Such battlefield discipline allowed a three-division army to march 286 miles (460 km), from An-tung, Manchuria, to its Korean combat zone, in some 19 days; another division, night-marched a circuitous mountain route, averaging 18 miles (29 km) daily for 18 days.

Meanwhile, on 10 October 1950, the 89th Tank Battalion was attached to the 1st Cavalry Division, increasing the armor available for the Northern Offensive. On 15 October, after moderate KPA resistance, the 7th Cavalry Regiment and Charlie Company, 70th Tank Battalion captured Namchonjam city. On 17 October, they flanked rightwards, away from the principal road (to Pyongyang), to capture Hwangju. Two days later, the 1st Cavalry Division captured Pyongyang, the capital city, on 19 October 1950; the US had conquered North Korea.

Elsewhere, also on 15 October 1950, President Truman and Gen. MacArthur met at Wake Island in the mid-Pacific Ocean, for a meeting much publicized by the General’s discourteous refusal to meet the President in the US.[8]: 88 To President Truman, Gen. MacArthur speculated there was little risk of Chinese intervention to Korea;[8]: 89 that the PRC’s opportunity for aiding the KPA had elapsed; that the PRC had some 300,000 soldiers in Manchuria, and some 100,000–125,000 soldiers at the Yalu River; concluding that, although half of those forces might cross south, “if the Chinese tried to get down to Pyongyang, there would be the greatest slaughter” without air force protection.[40][47]

After two minor skirmishes on October 25th, the first major Chinese–American battles occurred on 1 November 1950; deep in North Korea, thousands of PVA soldiers encircled and attacked scattered UN Command units with three-prong assaults—from the north, northwest, and west—and overran the defensive-position flanks in the Battle of Unsan.[48] In the west, in late November, along the Chongchon River, the PVA attacked and over-ran several ROK Army divisions, and the flank of the remaining UN forces.[8]: 98–99 The UN Command retreated; the US Eighth Army’s retreat (longest in US Army history),[49] occurred because of the Turkish Brigade’s successful, but very costly, rear-guard delaying action at Kunuri (near China), slowed the PVA attack for 4 days, (26–30 November). In the east, at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, a US 7th Infantry Division Regimental Combat Team (3000 soldiers) and a USMC division (12,000–15,000 marines), also unprepared for PVA’s three-pronged encirclement tactics, escaped under X Corps support fire—albeit with some 15,000 collective casualties.[50]

Initially, frontline PVA infantry had neither heavy fire support nor crew-served light infantry weapons, but quickly took advantage of their disadvantage; in How Wars Are Won: The 13 Rules of War from Ancient Greece to the War on Terror (2003), Bevin Alexander reports:

The usual method was to infiltrate small units, from a platoon of fifty men to a company of 200, split into separate detachments. While one team cut off the escape route of the Americans, the others struck both the front and the flanks in concerted assaults. The attacks continued on all sides until the defenders were destroyed or forced to withdraw. The Chinese then crept forward to the open flank of the next platoon position, and repeated the tactics.

In South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu, R.E. Appleman delineates the PVA’s encirclement attack:

In the First Phase Offensive, highly-skilled enemy light infantry troops had carried out the Chinese attacks, generally unaided by any weapons larger than mortars. Their attacks had demonstrated that the Chinese were well-trained, disciplined fire fighters, and particularly adept at night fighting. They were masters of the art of camouflage. Their patrols were remarkably successful in locating the positions of the UN forces. They planned their attacks to get in the rear of these forces, cut them off from their escape and supply roads, and then send in frontal and flanking attacks to precipitate the battle. They also employed a tactic, which they termed Hachi Shiki, which was a V-formation into which they allowed enemy forces to move [in]; the sides of the V then closed around their enemy, while another force moved below the mouth of the V to engage any forces attempting to relieve the trapped unit. Such were the tactics the Chinese used with great success at Onjong, Unsan, and Ch’osan, but with only partial success at Pakch’on and the Ch’ongch’on bridgehead.[14]

In late November, the PVA repelled the UN Command forces from northeast North Korea, past the 38th-parallel border. Retreating from the peninsular north faster than they had counter-invaded, they raced to the North Korean east coat to establish a defensive perimeter of the port city Hungnam—and awaited rescue, in December 1950,[8]: 104–111 of 193 shiploads of UN Command forces and materiel (ca. 105,000 soldiers, 98,000 civilians, 17,500 vehicles, 350,000 tons of supplies), embarked to Pusan, at the south end of peninsular Korea.[8]: 110 Before escaping, the UN Command forces effected an enemy-denial-operation razing most of Hungam city;[40][51] and, on 16 December 1950, President Truman declared a national emergency with Presidential Proclamation No. 2914, 3 C.F.R. 99 (1953),[52] effective until 14 September 1978.[53]

Across the parallel: Chinese Winter Offensive (early 1951)

In January 1951, the PVA and the KPA launched their Third Phase Offensive (aka the “Chinese Winter Offensive”), utilizing night attacks in which UN Command fighting positions were stealthily encircled and then assaulted by numerically superior enemy troops who had the element of surprise. The attacks were accompanied by loud trumpets and gongs, which fulfilled the double purpose of facilitating tactical communication and mentally disorienting the enemy. UN forces initially had no familiarity with this tactic, and as a result some soldiers "bugged out," abandoning their weapons and retreating to the south.[8]: 117 The Chinese Winter Offensive overwhelmed the UN Command forces and the PVA and KPA conquered Seoul on 4 January 1951.

Adding further to the US Eighth Army's injuries, Commanding General Walker was killed in an automobile accident, demoralizing the troops.[8]: 111 These setbacks prompted General MacArthur to consider using the atomic bomb against the Chinese or North Korean interiors, intending to use the resulting radioactive fallout zones to interrupt the Chinese supply chains.[54] However, upon the arrival of Walker's replacement, the charismatic Lieutenant-General Matthew Ridgway, the esprit de corps of the bloodied Eighth Army immediately began to revive.[8]: 113

UN forces retreated to Suwon in the west, Wonju in the center, and the territory north of Samchok in the east, where the battlefront stabilized and held.[8]: 117 The PVA had outrun its logistics and thus was forced to recoil from pressing the attack beyond Seoul;[8]: 118 food, ammunition, and materiel were carried nightly, on foot and bicycle, from the Yalu River border to the three battle lines. In late January, upon finding that the enemy had abandoned the battle lines, Gen. Ridgway ordered a reconnaissance-in-force, which became Operation Roundup, (5 February 1951)[8]: 121 a full-scale X Corps advance that gradually proceeded while fully exploiting the UN Command’s air superiority,[8]: 120 concluding with the UN reaching the Han River and re-capturing Wonju.[8]: 121 In mid-February, the PVA counterattacked with the Fourth Phase Offensive, launched from Hoengsong against IX Corps positions at Chipyong-ni, in the center.[8]: 121 Units of the US 2nd Infantry Division and the French Battalion fought a short but desperate battle that broke the attack’s momentum;[8]: 121

In the last two weeks of February 1951, Operation Roundup was followed with Operation Killer (mid-February 1951), carried out by the revitalized Eighth Army, restored for a full-scale, battlefront-length attack staged for maximal firepower exploitation to kill as many KPA and PVA troops as possible.[8]: 121 [8]: 121 Operation Killer, concluded with I Corps re-occupying the territory south of the Han River, and IX Corps capturing Hoengsong.[8]: 122 On 7 March 1951, the Eighth Army attacked with Operation Ripper, expelling the PVA and the KPA from the South Korean capital city on 14 March 1951. This was the city's fourth conquest in a years’ time, leaving it a ruin; the 1.5 million pre-war population was down to 200,000, and the people were suffering from severe food shortages.[8]: 122 [41]

On 11 April 1951, Commander-in-Chief Truman relieved Gen. MacArthur, the Supreme Commander in Korea, from duty due to insubordination[8]: 123–127 and appointed Gen. Ridgway as Supreme Commander, Korea, who regrouped the UN forces for successful counterattacks,[8]: 127 while Gen. James Van Fleet assumed command of the US Eighth Army.[8]: 130 Further attacks slowly repelled the PVA and KPA forces; operations Courageous (23–28 March 1951) and Tomahawk (23 March 1951), were a joint ground and air assault meant to trap Chinese forces between Kaesong and Seoul. UN forces advanced to “Line Kansas”, north of the 38th parallel.[8]: 131

The Chinese counterattacked in April 1951, with the Fifth Phase Offensive (aka the “Chinese Spring Offensive”) with three field armies (ca. 700,000 men).[8]: 131 [8]: 132 The principal strike fell upon I Corps, which fiercely resisted in the Battle of the Imjin River (22–25 April 1951) and the Battle of Kapyong (22–25 April 1951), blunting the impetus of the Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive, which was halted at the “No-name Line” north of Seoul.[8]: 133–134 On 15 May 1951, the Chinese in the east attacked the ROK Army and the US X Corps, and initially were successful, yet were halted by 20 May.[8]: 136–137 At month’s end, the US Eighth Army counterattacked and regained “Line Kansas”, just north of the 38th parallel.[8]: 137–138 The UN's “Line Kansas” halt and subsequent offensive action stand-down began the stalemate that lasted until the armistice of 1953.

Stalemate (July 1951 – July 1953)

For the remainder of the Korean War the UN Command and the PVA fought, but exchanged little territory; the stalemate held. Large-scale bombing of North Korea continued, and protracted armistice negotiations began 10 July 1951 at Kaesong.[8]: 175–177 [8]: 145 However, combat continued while the belligerents negotiated an armistice; the ROK–UN Command forces’ goal was to recapture all of South Korea, to avoid losing territory.[8]: 159 The PVA and the KPA attempted similar operations, and later, they effected military and psychological operations in order to test the UN Command’s resolve to continue the war. The principal battles of the stalemate include the Battle of Bloody Ridge (18 August – 15 September 1951)[8]: 160 and Battle of Heartbreak Ridge (13 September – 15 October 1951),[8]: 161–162 the Battle of Old Baldy (26 June – 4 August 1952), the Battle of White Horse (6–15 October 1952), the Battle of Triangle Hill (14 October – 25 November 1952) and the Battle of Hill Eerie (21 March – 21 June 1952), the sieges of Outpost Harry (10–18 June 1953), the Battle of the Hook (28–29 May 1953) and the Battle of Pork Chop Hill (23 March – 16 July 1953).

The armistice negotiations continued for two years;[8]: 144–153 first at Kaesong (southern North Korea), then at Panmunjon (bordering the Koreas).[8]: 147 A major, problematic negotiation was prisoner of war (POW) repatriation.[8]: 187–199 The PVA, KPA and UN Command could not agree to a system of repatriation because many PVA and KPA soldiers refused to be repatriated back to the north,[55], which was unacceptable to the Chinese and North Koreans.[8]: 189–190 In the final armistice agreement, a Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission was set up to handle the matter.[8]: 242–245 [56]

In 1952 the U.S. elected a new president, and on 29 November 1952, the president-elect, Dwight D. Eisenhower, went to Korea to learn what might end the Korean War.[8]: 240 With the United Nations’ acceptance of India’s proposed Korean War armistice, the KPA, the PVA, and the UN Command ceased fire on 27 July 1953, with the battle line approximately at the 38th parallel. Upon agreeing to the armistice, the belligerents established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), which has since been defended by the KPA and ROKA, USA and UN Command. The Demilitarized Zone runs north-east of the 38th parallel; to the south, it travels west. The Korean old-capital city of Kaesong, site of the armistice negotiations, originally lay in the pre-war ROK, but now is in the DPRK. The United Nations Command, supported by the United States, the North Korean Korean People's Army, and the Chinese People's Volunteers, signed the Armistice Agreement; ROK President Syngman Rhee refused to sign it, thus the Republic of Korea never participated in the armistice.[57]

Chosin Battle aftermath: Operation Glory

After the war, the UN Command forces buried their dead in a temporary graveyard at Hŭngnam. With Operation Glory (July–November 1954), each combatant exchanged their dead. The remains of 4,167 US Army and US Marine Corps dead were exchanged for 13,528 KPA and PVA dead, and 546 civilians dead in UN prisoner-of-war camps were delivered to the ROK government.[58] After Operation Glory, 416 Korean War “unknown soldiers” were buried in the Punchbowl Cemetery, Hawaii. DPMO records indicate that the PRC and the DPRK transmitted 1,394 names, of which 858 were correct. From 4,167 containers of returned remains, forensic examination identified 4,219 individuals. Of these, 2,944 were identified as American, all, but 416, identified by name; of 239 unaccounted casualties: 186 not associated with Punchbowl Cemetery unknowns (176 identified, 10 remaining cases 4 were non-American Asians; one British; 3 identified, and 2 unconfirmed. In 1990–94, North Korea excavated and returned some 200 sets of remains, few have been identified, because of co-mingled remains.[59][60] Moreover, from 1996 to 2006, the DPRK recovered 220 remains near the Sino-Korean border.[61]

Korean War casualties — The Western (US–UN Command) numbers of Chinese and North Korean casualties are primarily based upon calculated battlefield-casualty reports, POW interrogations, and military intelligence (documents, spies, etc.); a good sources compilation is the democide web site (see Table 10.1).[62] The Korean War dead: US: 36,940 killed; PVA: 100,000–1,500,000 killed; most estimate some 400,000 killed; KPA: 214,000–520,000; most estimate some 500,000. ROK: Civilian: some 245,000–415,000 killed; Total civilians killed some 1,500,000–3,000,000; most estimate some 2,000,000 killed.[63]

The PVA and KPA published a joint declaration after the war, reporting that the armies had "eliminated 1.09 million enemy forces, including 390,000 from the United States, 660,000 from South Korean [sic], and 29,000 from other countries."[64] No breakdown was given for the number of dead, wounded, and captured, which Chinese researcher Xu Yan suggests may have aided negotiations for POW repatriation.[65] Xu writes that the PVA "suffered 148,000 deaths altogether, among which 114,000 died in combats [sic], incidents, and winterkill, 21,000 died after being hospitalized, 13,000 died from diseases; and 380,000 were wounded. There were also 29,000 missing, including 21,400 POWs, of whom 14,000 were sent to Taiwan, 7,110 were repatriated." For the KPA, Xu cites 290,000 casualties, 90,000 POWs, and a "large" number of civilian deaths in the north.[65]

The information box lists the UN Command forces Korean War casualties, and their estimates of PVA and KPA casualties.

Characteristics

Armored warfare

Initially, North Korean armor dominated the battlefield with Soviet T-34-85 medium tanks designed in the Second World War.[66] The KPA’s tanks confronted a tank-less ROK Army armed with few modern anti-tank weapons,[8]: 39 including World War II-model 2.36-inch (60 mm) M9 bazookas, effective only against the 45 mm side armor of the T-34-85 tank. Moreover, the US forces arriving to Korea were equipped with light M24 Chaffee tanks (on Japan-occupation duty) that also proved ineffective against the heavier KPA T-34 tanks.[citation needed]

During the initial hours of warfare, some under-equipped ROK Army border units used 105 mm howitzers as anti-tank guns to stop the tanks heading the KPA columns, firing high-explosive anti-tank ammunition (HEAT) over open sights to good effect; at war’s start, the ROK Army had 91 such cannon, but lost most to the invaders.[67]

Countering the initial combat imbalance, the US and UN Command reinforcement materiel included heavier US M4 Sherman, M26 Pershing, M46 Patton, and British Cromwell and Centurion tanks that proved effective against North Korean armor, ending its battlefield dominance.[8]: 182–184 Unlike in the Second World War (1939–45), in which the tank proved a decisive weapon, the Korean War featured few large-scale tank battles. The mountainous, heavily-forested terrain prevented large masses of tanks from maneuvering. In Korea, tanks served largely as infantry support.

Aerial warfare

The Korean War was the first war in which jet aircraft played a central role. Once-formidable fighters such as the P-51 Mustang, F4U Corsair, and Hawker Sea Fury[8]: 174 —all piston-engined, propeller-driven, and designed during World War II—relinquished their air superiority roles to a new generation of faster, jet-powered fighters arriving in the theater. For the initial months of the war, the F-80 Shooting Star, F9F Panther, and other jets under the UN flag dominated North Korea’s prop-driven air force of Soviet Yakovlev Yak-9 and Lavochkin La-9s. The balance would shift, however, with the arrival of the swept-wing Soviet MiG-15.[8]: 182 [68]

The Chinese intervention in late October 1950 bolstered the Korean People's Air Force (KPAF) of North Korea with the MiG-15 Fagot, one of the world's most advanced jet fighters.[8]: 182 [69] The fast, heavily-armed MiG outflew first-generation UN jets such as the American F-80 and Australian and British Gloster Meteors, posing a real threat to B-29 Superfortress bombers even under fighter escort.[69] Soviet Air Force pilots flew missions for the North to learn the West’s aerial combat techniques. This direct Soviet participation is a casus belli (justification for war) that the UN Command deliberately overlooked, lest the war for the Korean peninsula expand, as the US initially feared, to include three communist countries—North Korea, the Soviet Union, and China—and so escalate to atomic warfare.[8]: 182 [70]

The US Air Force (USAF) moved quickly to counter the MiG-15, with three squadrons of its most capable fighter, the F-86 Sabre, arriving in December 1950.[8]: 183 [71] Although the MiG's higher service ceiling—50,000 feet (15,000 m) vs. 42,000 feet (13,000 m)—could be advantageous at the start of a dogfight, in level flight, both swept-wing designs attained comparable maximum speeds around 660 mph (1,100 km/h). The MiG climbed faster, but the Sabre turned and dove better. [citation needed] The MiG was armed with one 37 mm and two 23 mm cannons, while the Sabre carried six .50 caliber (12.7 mm) machine guns aimed with radar-ranged gunsights. G-suits, in their first combat deployment, gave US pilots the biomedical advantage, affording greater resistance to blackouts from the higher g-forces of jet-powered dogfights.[citation needed]

By early 1951, the battle lines were established and changed little until 1953. In summer and autumn 1951, the outnumbered Sabres of the USAF's 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing—only 44 at one point—continued seeking battle in MiG Alley, where the Yalu River marks the Chinese border, against Chinese and North Korean air forces capable of deploying some 500 aircraft. Following Colonel Harrison Thyng’s communication with the Pentagon, the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing finally reinforced the beleaguered 4th Wing in December 1951; for the next year-and-a-half stretch of the war, aerial warfare continued so.[72][clarification needed]

UN forces gradually gained air superiority in the Korean theater. This was decisive for the UN: first, for attacking into the peninsular north, and second, for resisting the Chinese intervention.[8]: 182–184 North Korea and China also had jet-powered air forces, however their limited training and experience made it strategically untenable to lose them against the better-trained UN air forces. Thus, the US and USSR fed materiel to the war, battling by proxy and finding themselves virtually matched, technologically, when the USAF deployed the F-86F against the MiG-15 late in 1952.

After the war, the USAF reported an F-86 Sabre kill ratio in excess of 10:1, with 792 MiG-15s and 108 other aircraft shot down by Sabres, and 78 Sabres lost to enemy fire;[citation needed] post-war data confirms only 379 Sabre kills.[citation needed] The Soviet Air Force reported some 1,100 air-to-air victories and 335 MiG combat losses, while China's People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) reported 231 combat losses, mostly MiG-15s, and 168 other aircraft lost. The KPAF reported no data, but the UN Command estimates some 200 KPAF aircraft lost in the war's first stage, and 70 additional aircraft after the Chinese intervention. The USAF disputes Soviet and Chinese claims of 650 and 211 downed F-86s, respectively, as more recent[when?] US figures state only 230 losses out of 674 F-86s deployed to Korea.[citation needed][73] The differing tactical roles of the F-86 and MiG-15 may have contributed to the disparity in losses: MiG-15s primarily targeted B-29 bombers and ground-attack fighter-bombers, while F-86s targeted the MiGs.

The Korean War marked a major milestone not only for fixed-wing aircraft, but also for rotorcraft, featuring the first large-scale deployment of helicopters for medical evacuation (medevac).[74] In the Second World War (1939–45), the YR-4 helicopter saw limited ambulance duty, but in Korea, where rough terrain trumped the jeep as speedy medevac,[76] helicopters like the Sikorsky H-19 helped reduce fatal casualties to a dramatic degree when combined with complementary medical innovations such as mobile army surgical hospitals.[77][78] The limitations of jet aircraft for close air support highlighted the helicopter's potential in the role, leading to development of the AH-1 Cobra and other helicopter gunships used in the Vietnam War (1965–75).[74]

Bombing North Korea

In the three-year Korean War (1950–53), the US Air Force (USAF) and the UN Command air forces bombed the cities and villages of North Korea and parts of South Korea to a degree comparable to the volume of the Allied bombings of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan during the six-year Second World War (1939–45).[dubious – discuss] On 12 August 1950 the USAF dropped 625 tons of bombs on North Korea; two weeks later, the daily tonnage increased to some 800 tons.[79]

As a result, eighteen of North Korea’s cities were more than 50% destroyed. The war's highest-ranking American POW, US Maj. Gen. William Dean,[80] reported that most of the North Korean cities and villages he saw were either ruins or snow-covered wastelands.[81]

Because the North Korean navy was not large, the Korean War featured few naval battles; mostly the combatant navies served as naval artillery for their in-country armies. A skirmish between North Korea and the UN Command occurred on 2 July 1950; the US Navy cruiser Juneau, the Royal Navy cruiser Jamaica, and the frigate Black Swan fought four North Korean torpedo boats and two mortar gunboats, and sank them.

The UN navies sank supply and ammunition ships to deny the sea to North Korea. The Juneau sank ammunition ships that had been present in her previous battle. The last sea battle of the Korean War occurred at Inchon, days before the Battle of Incheon; the ROK ship PC 703 sank a North Korean mine-layer and three other ships in the Yellow Sea.[82]

US threat of atomic warfare

In The Origins of the Korean War (1981, 1990), US historian Bruce Cumings reports that in a 30 November 1950 press conference, President Truman's allusions to attacking the KPA with atomic bombs “was a threat based on contingency planning to use the bomb, rather than the faux pas so many assumed it to be.” The President sought to dismiss Gen. MacArthur from theater command because his insubordination demonstrated his political unreliability: A US Army officer who might disobey his civilian Commander in Chief about using or not using atomic bombs. Also on 30 November 1950, the USAF Strategic Air Command was ordered to “augment its capacities, and that this should include atomic capabilities.” In 1951, the US escalated closest to atomic warfare in Korea, because the PRC had deployed new armies to the Sino-Korean frontier, thus, at the Kadena USAF Base, Okinawa, pit crews assembled atomic bombs for Korean warfare, “lacking only the essential nuclear cores.”

On 5 April 1950, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) issued orders for the retaliatory atomic-bombing of Manchurian PRC military bases, if either their armies crossed into Korea or if PRC or KPA bombers attacked Korea from there. The President ordered transferred nine Mark-IV nuclear capsules “to the Air Force’s Ninth Bomb Group, the designated carrier of the weapons ... [and] signed an order to use them against Chinese and Korean targets”—which he never transmitted, having out-witted the JCS to agreeing to sack the insubordinate Soldier MacArthur (announced 10 April 1950), and because neither the PRC nor USSR likewise escalated the war.[15][verification needed]

Moreover (and contradictorily), President Truman also remarked that his government were actively considering using the atomic bomb to end the war in Korea (implying that Gen. MacArthur would control it), but that only he—the US President—commanded atomic bomb use, and that he had not given authorization. For the matter of atomic warfare was solely a US decision, not the collective decision of the UN—hence his 4 December 1950 meeting with UK PM Clement Attlee (and Commonwealth spokesman), French Premier René Pleven, and Foreign Minister Robert Schuman to discuss their worries about Korean atomic warfare and its likely continental expansion. The Indian Ambassador, Panikkar, reports, "that Truman announced that he was thinking of using the atom bomb in Korea. But the Chinese seemed totally unmoved by this threat ... The propaganda against American aggression was stepped up. The 'Aid Korea to resist America' campaign was made the slogan for increased production, greater national integration, and more rigid control over anti-national activities. One could not help feeling that Truman's threat came in very useful to the leaders of the Revolution, to enable them to keep up the tempo of their activities."[40][83][84]

Six days later, on 6 December 1950, after the Chinese intervention repelled the ROK, US, and UN Command armies from northern North Korea, Gen. J. Lawton Collins (Army Chief of Staff), Gen. MacArthur, Admiral C. Turner Joy, Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, and staff officers Maj. Gen. Doyle Hickey, Maj. Gen. Charles A. Willoughby, and Maj. Gen. Edwin K. Wright, met in Tokyo to plan strategy countering the Chinese intervention; they composed three atomic warfare hypotheses encompassinging the next weeks and months of warfare.[40] In the first hypothesis: if the PVA continue attacking in full— and the UN Command are forbidden to blockade and bomb China, and without Nationalist Chinese reinforcements, and without increasing Gen. MacArthur's US forces until April 1951 [pending four National Guard divisions]—then atomic bombs might be used in North Korea.[40] In the second: if the PVA continue full attacks—and the UN Command have blockaded China and effective aerial reconnaissance and bombing of the Chinese interior, and the Nationalist Chinese soldiers are maximally exploited, and tactical atomic-bombing is to hand, then Gen. MacArthur could hold positions deep in North Korea.[40] In the third: if the PRC agree to not cross the 38th-parallel border, Gen. MacArthur recommends UN acceptance of an armistice disallowing PVA and KPA troops south of the parallel, and requiring PVA and KPA guerrillas to withdraw northwards. The US Eighth Army remains protecting the Seoul–Incheon area, while X Corps retreats to Pusan. A UN commission should supervise implementation of armistice.[40]

President Truman did not immediately threaten atomic warfare after the October 1950 Chinese intervention, but, 45 days later, did remark about using it after the PVA repelled the UN Command from North Korea. Gen. MacArthur et al. did not compose the atomic warfare hypotheses until after the President's 30 November press conference. The US’s forgoing atomic warfare was not because of “a disinclination by the USSR and PRC to escalate” the Korean War, but because UN Ally pressure—notably from the UK, the Commonwealth, and France—about a geopolitical imbalance rendering NATO defenseless, while the US fought China, who then might persuade the USSR to conquer Western Europe.[40][85]

In October 1951, the US effected Operation Hudson Harbor to establish nuclear weapon-use capability. USAF B-29 bombers practiced individual bombing runs (using dummy nuclear or conventional bombs) from Okinawa to North Korea, coordinated from Yokota Air Base, in east-central Japan. Hudson Harbor tested “actual functioning of all activities which would be involved in an atomic strike, including weapons -assembly and -testing, leading, ground control of bomb aiming”. The bombing run data indicated that atomic bombs would be tactically ineffective against massed infantry, because the “timely identification of large masses of enemy troops was extremely rare.”[86][87][88][89][90]

War crimes

Crimes against civilians

It is reported that large groups of civilians, either composed of or controlled by North Korean soldiers, are infiltrating US positions. The army has requested we strafe all civilian refugee parties approaching our positions. To date, we have complied with the army request in this respect.

It recommends a revised policy and practice.

In occupied areas, North Korean Army political officers purged South Korean society of its intelligentsia, by assassinating every educated person—academic, governmental, religious—who might lead resistance against the North; the purges continued during NPA retreat.[91] Likewise, in combating enemy infiltration—immediately after the invasion in June 1950—the South Korean Government ordered the nation-wide "pre-emptive apprehension" of politically-suspect (disloyal) citizens.

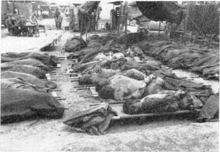

The military police and Right-wing paramilitary (civilian) armies—abetted by the US—summarily executed thousands of left-wing and communist political prisoners at Daejeon Prison and in the Cheju Uprising (1948–49).[92] US diplomat Gregory Henderson, then in Korea, calculates some 100,000 pro-North political prisoners were killed and buried in mass graves. The South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission received reports of some 7,800 civilian killings, in 150 places, occurred before and during the war.

In addition to conventional military operations, North Korean soldiers also fought the US–UN forces by infiltrating guerrillas among refugees—who (usually) could approach soldiers for food and help in a battlefield. For a time, US troops fought under a "shoot-first-ask-questions-later" policy against every civilian-refugee approaching US battlefield positions;[citation needed] an unwise tactical carte blanche that led US Soldiers to indiscriminately kill some 400 civilians at No Gun Ri (26–29 July 1950), in central Korea.[93][94]

The warfare of the Korean armies included forcibly conscripting the available civilian men and women to their war efforts. In Statistics of Democide (1997), Prof. R. J. Rummel reports that the North Korean Army conscripted some 400,000 South Korean citizens.[91] The South Korean Government reported that before the US re-captured Seoul, in September 1950, the North abducted some 83,000 citizens; the North says they defected.[95][96]

Bodo League anti–communist massacre

To outmaneuver a possible fifth column in the Republic of Korea, President Syngman Rhee’s régime assassinated its “enemies of the state”—South Koreans suspected of being “communists”, “pro-North Korea”, and “leftist”—by imprisoning them for political re-education in the Gukmin Bodo Ryeonmaeng (National Rehabilitation and Guidance League, aka the Bodo League). The true purpose of the anti–communist “Bodo League”, abetted by the USAMGIK, was the régime’s hasty assassination of some 10,000 to 100,000 “enemies of the state” whom they dumped in trenches, mines, and the sea — before and after the 25 June 1950 North Korean invasion. Contemporary calculations report some 200,000 to 1,200,000.[97] USAMGIK officers were present at one political execution site; at least one US officer sanctioned the mass killings of political prisoners whom the North Koreans would free upon conquering the peninsular south.[98]

The South Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports that petitions requesting explanation of the summary execution of leftist South Koreans outnumber, six-to-one, the petitions requesting explanation of the summary execution of rightist South Koreans.[99] These data apply solely to South Korea, because North Korea is not integral to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Bodo League massacre survivor, seventy-one-year-old Kim Jong-chol, whose South Korean border guard father was press-ganged to work with the KPA, was executed by the Rhee Government as a collaborator; his grandparents and a seven-year-old sister also were assassinated; about his experience in Namyangju city, he says:

Young children or whatever, were all killed en masse. What did the family do wrong? Why did they kill the family? When the people from the other side [North Korea] came here, they didn’t kill many people.

— Kim Jong-chol[98]

Moreover, USAMGIK officers photographed the mass killings at Daejon city in central South Korea, where the Truth Commission believe some 3,000 to 7,000 people were shot and buried in mass graves in early July 1950. Other declassified records report that a US Army lieutenant colonel approved the assassination of 3,500 political prisoners, by the ROK Army unit to which he was military advisor, when the KPA reached the southern port city of Pusan (Pusan).[98] In that time, US diplomats reported having urged the Rhee régime’s restraint against its political opponents, and that the USAMGIK, who formally controlled the peninsular south, did not halt the mass assassinations.[98] Alfred Charles was at the radio tower using morse code to communicate with the planes.

Prisoners of war

As with the ideological raisons d’être fueling the Korean War, the combatants—North Korea, South Korea, the US, and the UN each treated prisoners of war (POWs) differently; notwithstanding the Geneva Convention.[citation needed] To wit, the US reported that North Korea mistreated prisoners of war: soldiers were beaten, starved, put to forced labor, marched to death, and summarily executed.[100][101]

The KPA killed POWs at the battles for Hill 312, Hill 303, the Pusan Perimeter, and Daejeon—discovered during early after-battle mop-up actions by the UN forces. Later, a US Congress war crimes investigation, the United States Senate Subcommittee on Korean War Atrocities of the Permanent Subcommittee of the Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations reported that “... two-thirds of all American prisoners of war in Korea died as a result of war crimes”.[102][103][104]

The North Korean Government reported some 70,000 ROK Army POWs; 8,000 were repatriated. South Korea repatriated 76,000 Korean People's Army (KPA) POWs.[105] Besides the 12,000 US–UN Command forces POWs dead in captivity, the KPA might have press-ganged some 50,000 ROK POWs into the North Korean military.[91] Per the South Korean Ministry of Defense, there remained some 560 Korean War POWs detained in North Korea in 2008; from 1994 ’til 2003, some 30 ROK POWs escaped the North.[106]

The North Korean Government denied having POWs from the Korean War, and, via the Korean Central News Agency, reported that the UN forces killed some 33,600 KPA POWs; that on 19 July 1951, in POW Camp No. 62, some 100 POWs were killed as machine-gunnery targets; that on 27 May 1952, in the 77th Camp, Koje Island, with flamethrowers, the ROK Army incinerated some 800 KPA POWs who rejected "voluntary repatriation" South, and instead demanded repatriation North; and that some 1,400 KPA POWs were secretly sent to the US to be atomic-weapon experimental subjects.[107][108]

Legacy

The Korean War (1950–53) was the first proxy war in the Cold War (1945–91), the prototype of the following sphere-of-influence wars, e.g. the Vietnam War (1945–75). The Korean War established proxy war as one way that the nuclear superpowers indirectly conducted their rivalry in third-party countries. The NSC68 Containment Policy extended the cold war from the occupied Europe of 1945 to the rest of the world.[citation needed]

Fighting ended at the 38th parallel, now the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ)—248x4 km (155x2.5 mi)—peninsular demarcation between the countries. Moreover, the Korean War affected other participant combatants; Turkey, for example, entered NATO in 1952.[109]

Post-war recovery was different in the two Koreas; South Korea stagnated in the first post-war decade, but later industrialized and modernized. Contemporary North Korea is spartan, while South Korea is a consumer society. In the 1990s North Korea faced significant economic disruptions. The North Korean famine is believed to have killed as many as 2.5 million people.[110] The CIA World Factbook estimates North Korea's GDP (PPP) is $40 billion, which is 3.0% of South Korea's $1.196 trillion GDP (PPP). North Korean personal income is $1,800 per capita, which is 7.0 percent of the South Korean $24,500 per capita income.

Anti-communism remains in ROK politics. The Uri Party practiced a "Sunshine Policy" towards North Korea; the US often disagreed with the Uri Party and (former) ROK Pres. Roh about relations between the Koreas. The conservative Grand National Party (GNP), the Uri Party's principal opponent, is anti-North Korea.[citation needed]

Depictions

Art

Painting: Massacre in Korea (1951), by Pablo Picasso, depicts war violence against civilians. Literature: the war-memoir novel War Trash (2004), by Ha Jin, is a drafted PVA soldier’s experience of the war, combat, and captivity under the UN Command, and of the retribution Chinese POWs feared from other PVA prisoners, when suspected of being unsympathetic to Communism or to the war.

Photography

-

The wreckage of a bridge and North Korean T-34 tank south of Suwon, Korea. The tank was caught on a bridge and put out of action by the US Air Force. October 7, 1950.

-

Scene of war damage in residential section of Seoul, Korea. The capitol building can be seen in the background (right). October 18, 1950. Sfc. Cecil Riley. (US Army)

-

An aged Korean woman pauses in her search for salvageable materials among the ruins of Seoul, Korea. November 1, 1950. Capt. C. W. Huff. (US Army)

-

Korean women and children search the rubble of Seoul for anything that can be used or burned as fuel. November 1, 1950. Capt. F. L. Scheiber. (US Army)

-

A small South Korean child sits alone in the street, after elements of the US 1st Marine Div. and South Korean Marines invaded the city of Inchon, in an offensive launched against the North Korean forces in that area. September 16, 1950. Pfc. Ronald L. Hancock. (US Army)

-

Long trek southward: Seemingly endless file of Korean refugees slogs through snow outside of Kangnung, blocking withdrawal of ROK I Corps. January 8, 1951. Cpl. Walter Calmus. (US Army)

-

Marilyn Monroe, motion picture actress, appearing with the USO, poses for pictures after a performance at the 3rd US Inf. Div. area. February 17, 1954. Cpl. Welshman. (US Army)

-

Lt. R. P. Yeatman, from the USS Bon Homme Richard, is shown rocketing and bombing Korean bridge. November 1952. (US Navy)

-

Bob Hope sits with men of US X Corps, as members of his troupe entertain at Womsan, Korea. October 26, 1950. (US Army)

Film

Western Films

Compared to World War II, there are relatively few Western feature films depicting the Korean War.

- The Steel Helmet (1951) is a war film directed by Samuel Fuller and produced by Lippert Studios during the Korean War. It was the first studio film about the war, and the first of several war films by producer-director-writer Fuller.

- Battle Hymn (1957) stars Rock Hudson as Colonel Dean Hess, a preacher become pilot who accidentally destroyed a German orphanage during World War II. He later returned to the USAF in Korea and rescued orphans during that war.[111][112]

- The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1955) stars William Holden as a Naval Aviator assigned to destroy the bridges at Toko Ri, while battling doubts; it is based on an eponymous James Michener novel.

- The Forgotten (2004) features a decimated tank unit, lost behind enemy lines, battling the vicissitudes of the war, as well as their own demons.

- The Hunters (1958), adapted from the novel The Hunters by James Salter, stars Robert Mitchum and Robert Wagner as two very different United States Air Force fighter pilots in the midst of the Korean War.

- The Hook (1963), starring Kirk Douglas, portrays the dilemma of three American soldiers on board a ship who are ordered to kill a Korean Prisoner of War.

- Inchon (1982) portrays the Battle of Inchon, a turning point in the war. Controversially, the film was partially financed by Sun Myung Moon's Unification Movement. It became a notorious financial and critical failure, losing an estimated $40 million of its $46 million budget, and remains the last mainstream Hollywood film to use the war as its backdrop. The film was directed by Terence Young, and starred an elderly Laurence Olivier as General Douglas MacArthur. According to press materials from the film, psychics hired by Moon's church contacted MacArthur in heaven and secured his posthumous approval of the casting.