2008 Mumbai attacks

| 2008 Mumbai Terrorist Attacks | |

|---|---|

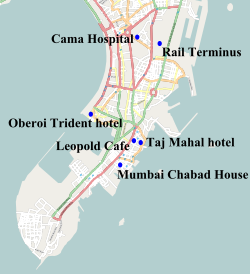

Map of the 2008 Mumbai attacks | |

| Location | Mumbai |

| Date | 26 November 2008 – 29 November 2008 (IST, UTC +5:30) |

Attack type | Bombings, shootings, hostage crisis[1] |

| Deaths | Approximately 164[2] |

| Injured | More than 308[2] |

| Perpetrators | Indian Mujahideen |

The 2008 Mumbai attacks (often referred to as November 26 or 26/11) were more than 10 coordinated shooting and bombing attacks across Mumbai, India's largest city, by Islamists[7][8] from Pakistan.[9] The attacks, which drew widespread global condemnation, began on 26 November 2008 and lasted until 29 November, killing 164 people and wounding at least 308.[2][10]

Eight of the attacks occurred in South Mumbai: at Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, the Oberoi Trident,[11] the Taj Mahal Palace & Tower,[11] Leopold Cafe, Cama Hospital (a women and children's hospital),[11] Nariman House,[12] the Metro Cinema,[13] and a lane behind the Times of India building and St. Xavier's College.[11] There was also an explosion at Mazagaon, in Mumbai's port area, and in a taxi at Vile Parle.[14] By the early morning of 28 November, all sites except for the Taj hotel had been secured by Mumbai Police and security forces. An action by India's National Security Guards (NSG) on 29 November (the action is officially named Operation Black Tornado) resulted in the death of the last remaining attackers at the Taj hotel, ending all fighting in the attacks.[15]

Ajmal Kasab,[16] the only attacker who was captured alive, disclosed that the attackers were members of Lashkar-e-Taiba, the Pakistan-based militant organisation, considered a terrorist organisation by India, Pakistan, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the United Nations,[17] among others.[18] The Indian government said that the attackers came from Pakistan, and their controllers were in Pakistan.[19] On 7 January 2009,[20] Pakistan's Information Minister Sherry Rehman officially accepted Ajmal Kasab's nationality as Pakistani.[21] On 12 February 2009, Pakistan's Interior Minister Rehman Malik asserted that parts of the attack had been planned in Pakistan.[22] A trial court on 6 May 2010 sentenced Ajmal Kasab to death on five counts.

Background

There have been many bombings in Mumbai since the 13 coordinated bomb explosions killed 257 people and injured 700 on 12 March 1993.[23] The 1993 attacks are believed to be in retaliation for the Babri Mosque demolition.[24]

On 6 December 2002, a blast in a BEST bus near Ghatkopar station killed two people and injured 28.[25] The bombing occurred on the tenth anniversary of the demolition of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya.[26] A bicycle bomb exploded near the Vile Parle station in Mumbai, killing one person and injuring 25 on 27 January 2003, a day before the visit of the Prime Minister of India Atal Bihari Vajpayee to the city.[27] On 13 March 2003, a day after the tenth anniversary of the 1993 Bombay bombings, a bomb exploded in a train compartment near the Mulund station, killing 10 people and injuring 70.[28] On 28 July 2003, a blast in a BEST bus in Ghatkopar killed 4 people and injured 32.[29] On 25 August 2003, two bombs exploded in South Mumbai, one near the Gateway of India and the other at Zaveri Bazaar in Kalbadevi. At least 44 people were killed and 150 injured.[30] On 11 July 2006, seven bombs exploded within 11 minutes on the Suburban Railway in Mumbai.[31] 209 people were killed, including 22 foreigners[32] and over 700 injured.[33] According to the Mumbai Police, the bombings were carried out by Lashkar-e-Taiba and Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI).[34][35]

Attacks

The first events were detailed around 20:00 Indian Standard Time (IST) on 26 November, when 10 men in inflatable speedboats came ashore at two locations in Colaba. They reportedly told local Marathi-speaking fishermen who asked them who they were to "mind their own business" before they split up and headed two different ways. The fishermen's subsequent report to police received little response.[36]

Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus

The Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST) was attacked by two gunmen, one of whom, Ajmal Kasab, was later caught alive by the police and identified by eyewitnesses. The attacks began around 21:30 when the two men entered the passenger hall and opened fire,[37] using AK-47 rifles.[38] The attackers killed 58 people and injured 104 others,[38] their assault ending at about 22:45.[37] Security forces and emergency services arrived shortly afterwards. The two gunmen fled the scene and fired at pedestrians and police officers in the streets, killing eight police officers. The attackers passed a police station. Many of the outgunned police officers were afraid to confront the attackers, and instead switched off the lights and secured the gates. The attackers then headed towards Cama Hospital with an intention to kill patients,[citation needed] but the hospital staff locked all of the patient wards. A team of the Mumbai Anti-Terrorist Squad led by police chief Hemant Karkare searched the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus and then left in pursuit of Kasab and Khan. Kasab and Khan opened fire on the vehicle in a lane next to the hospital and the police returned fire. Karkare, Salaskar, Kamte and one of their officers were killed, though the only survivor, Constable Arun Jadhav, was wounded.[39] Kasab and Khan seized the police vehicle but later abandoned it and seized a passenger car instead. They then ran into a police roadblock, which had been set up after Jadhav radioed for help.[40] A gun battle then ensued in which Khan was killed and Kasab was wounded. After a physical struggle, Kasab was arrested.[41] A police officer, Tukaram Ombale was also killed.

Leopold Cafe

The Leopold Cafe, a popular restaurant and bar on Colaba Causeway in South Mumbai, was one of the first sites to be attacked.[42] Two attackers opened fire on the cafe on the evening of 26 November, killing at least 10 people (including some foreigners), and injuring many more.[43] The attackers fired into the street as they fled the scene.[citation needed]

Bomb blasts in taxis

There were two explosions in taxis caused by timer bombs. The first one occurred at 22:40 at Vile Parle, killing the driver and a passenger. The second explosion took place at Wadi Bunder between 22:20 and 22:25. Three people including the driver of the taxi were killed, and about 15 other people were injured.[14][44]

Taj Mahal Hotel and Oberoi Trident

Two hotels, the Taj Mahal Palace & Tower and the Oberoi Trident, were amongst the four locations targeted. Six explosions were reported at the Taj hotel and one at the Oberoi Trident.[45][46] At the Taj Mahal, firefighters rescued 200 hostages from windows using ladders during the first night.

CNN initially reported on the morning of 27 November 2008 that the hostage situation at the Taj had been resolved and quoted the police chief of Maharashtra stating that all hostages were freed;[47] however, it was learned later that day that there were still two attackers holding hostages, including foreigners, in the Taj Mahal hotel.[48]

During the attacks, both hotels were surrounded by Rapid Action Force personnel and Marine Commandos (MARCOS) and National Security Guards (NSG) commandos.[49][50] When reports emerged that attackers were receiving television broadcasts, feeds to the hotels were blocked.[51] Security forces stormed both hotels, and all nine attackers were killed by the morning of 29 November.[52][53] Major Sandeep Unnikrishnan of the NSG was killed during the rescue of Commando Sunil Yadav, who was hit in the leg by a bullet during the rescue operations at Taj.[54][55] 32 hostages were also killed at the Oberoi Trident.[citation needed]

A number of European Parliament Committee on International Trade delegates were staying in the Taj Mahal hotel when it was attacked,[56] but none of them were injured.[57] British Conservative Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Sajjad Karim (who was in the lobby when attackers initially opened fire there) and German Social Democrat MEP Erika Mann were hiding in different parts of the building.[58] Also reported present was Spanish MEP Ignasi Guardans, who was barricaded in a hotel room.[59] Another British Conservative MEP, Syed Kamall, reported that he along with several other MEPs left the hotel and went to a nearby restaurant shortly before the attack.[58] Kamall also reported that Polish MEP Jan Masiel was thought to have been sleeping in his hotel room when the attacks started, but eventually left the hotel safely.[60] Kamall and Guardans reported that a Hungarian MEP's assistant was shot.[58][61] Also caught up in the shooting were the President of Madrid, Esperanza Aguirre, while checking in at the Oberoi Trident,[61] and Indian MP N. N. Krishnadas of Kerala and Sir Gulam Noon while having dinner at a restaurant in the Taj hotel.[62][63]

Nariman House

Nariman House, a Chabad Lubavitch Jewish center in Colaba known as the Mumbai Chabad House, was taken over by two attackers and several residents were held hostage.[64] Police evacuated adjacent buildings and exchanged fire with the attackers, wounding one. Local residents were told to stay inside. The attackers threw a grenade into a nearby lane, causing no casualties. NSG commandos arrived from Delhi, and a Naval helicopter took an aerial survey. During the first day, 9 hostages were rescued from the first floor. The following day, the house was stormed by NSG commandos fast-roping from helicopters onto the roof, covered by snipers positioned in nearby buildings. After a long battle, one NSG commando and both perpetrators were killed.[65] Rabbi Gavriel Holtzberg and his wife Rivka Holtzberg, who was six months pregnant, were murdered with four other hostages inside the house by the attackers.[66]

According to radio transmissions picked up by Indian intelligence, the attackers "would be told by their handlers in Pakistan that the lives of Jews were worth 50 times those of non-Jews." Injuries reported on some of the bodies indicate they may have been tortured.[67]

End of the attacks

By the morning of 27 November, the army had secured the Jewish outreach center at Nariman House as well as the Oberoi Trident hotel. They also incorrectly believed that the Taj Mahal Palace and Towers had been cleared of attackers, and soldiers were leading hostages and holed-up guests to safety, and removing bodies of those killed in the attacks.[68][69][70] However, later news reports indicated that there were still two or three attackers in the Taj, with explosions heard and gunfire exchanged.[70] Fires were also reported at the ground floor of the Taj with plumes of smoke arising from the first floor.[70] The final operation at the Taj Mahal Palace hotel was completed by the NSG commandos at 08:00 on 29 November, killing three attackers and resulting in the conclusion of the attacks.[71] The security forces rescued 250 people from the Oberoi, 300 from the Taj and 60 people (members of 12 different families) from Nariman House.[72] In addition, police seized a boat filled with arms and explosives anchored at Mazgaon dock off Mumbai harbour.[73]

Attribution

The Mumbai attacks were planned and directed by Lashkar-e-Taiba militants inside Pakistan, and carried out by ten young armed men trained and sent to Mumbai and directed from inside Pakistan via mobile phones and VoIP.[18][74][75]

In July 2009 Pakistani authorities confirmed that LeT plotted and financed the attacks from LeT camps in Karachi and Thatta.[76] In November 2009, Pakistani authorities charged seven men they had arrested earlier, of planning and executing the assault.[77]

Mumbai police originally identified 37 suspects –-including two army officers-– for their alleged involvement in the plot. All but two of the suspects, many of whom are identified only through aliases, are Pakistani.[78] Two more suspects arrested in the United States in October 2009 for other attacks were also found to have been involved in planning the Mumbai attacks.[79][80] One of these men, Pakistani American David Headley, was found to have made several trips to India before the attacks and gathered video and GPS information on behalf of the plotters.

Cooperation with Pakistan

Pakistan initially denied that Pakistanis were responsible for the attacks, blaming plotters in Bangladesh and Indian criminals,[81] a claim refuted by India,[82] and saying they needed information from India on other bombings first.[83]

Pakistani authorities finally agreed that Ajmal Kasab was a Pakistani on 7 January 2009,[20][84][85] and registered a case against three other Pakistani nationals.[86]

The Indian government supplied evidence to Pakistan and other governments, in the form of interrogations, weapons, and call records of conversations during the attacks.[3][87] In addition, Indian government officials said that the attacks were so sophisticated that they must have had official backing from Pakistani "agencies", an accusation denied by Pakistan.[75][84]

Under U.S. and UN pressure, Pakistan arrested a few members of Jamaat ud-Dawa and briefly put its founder under house arrest, but he was found to be free a few days later.[88] A year after the attacks, Mumbai police continued to complain that Pakistani authorities are not cooperating by providing information for their investigation.[89] Meanwhile, journalists in Pakistan said security agencies were preventing them from interviewing people from Kasab's village.[90][91] Home Minister P. Chidambaram said the Pakistani authorities had not shared any information about American suspects Headley and Rana, but that the FBI had been more forthcoming.[92]

An Indian report, summarising intelligence gained from India's interrogation of David Headley,[93] was released in October 2010. It alleged that Pakistan's intelligence agency (ISI) had provided support for the attacks by providing funding for reconnaissance missions in Mumbai.[94] The report included Headley's claim that Lashkar-e-Taiba's chief military commander, Zaki-ur-Rahman Lakhvi, had close ties to the ISI Director General.[who?][93] He alleged that "every big action of LeT is done in close coordination with [the] ISI."[94] David Headley also revealed that Major Iqbal has given him $25,000 to setup a front company to do reconaissance for the Mumbai attacks[95].

Investigation

According to investigations, the attackers traveled by sea from Karachi, Pakistan, across the Arabian Sea, hijacked the Indian fishing trawler 'Kuber', killing the crew of four, and then forced the captain to sail to Mumbai. After killing the captain, the attackers entered Mumbai on a rubber dinghy. The captain of 'Kuber', Amar Singh Solanki, had earlier been imprisoned for six months in a Pakistani jail for illegally fishing in Pakistani waters.[96] The attackers stayed and were trained by the Lashkar-e-Taiba in a safehouse at Azizabad near Karachi before boarding a small boat for Mumbai.[97]

David Headley was a member of Lashkar-e-Taiba, and between 2002 and 2009 Headley traveled extensively as part of his work for LeT. Headley received training in small arms and countersurveillance from LeT, built a network of connections for the group, and was chief scout in scoping out targets for Mumbai attack[98][99] having allegedly been given $25,000 in cash in 2006 by an ISI officer known as Major Iqbal, The officer also helped him arrange a communications system for the attack, and oversaw a model of the Taj Mahal Hotel so that gunmen could know their way inside the target, according to Headley's testimony to Indian authorities. Headley also helped ISI recruit Indian agents to monitor Indian troop levels and movements, according to a U.S. official. At the same time, Headley was also an informant for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, and Headley's wives warned American officials of Headley's involvement with LeT and his plotting of terrorist operations, warning specifically that the Taj Mahal Hotel may be their target.[98]

U.S. officials believed that the Inter-Services Intelligence (I.S.I.) officers provided support to Lashkar-e-Taiba militants who carried out the attacks.[100]

Method

The attackers had planned the attack several months ahead of time and knew some areas well enough for the attackers to vanish, and reappear after security forces had left. Several sources have quoted Kasab telling the police that the group received help from Mumbai residents.[101][102] The attackers used at least three SIM cards purchased on the Indian side of the border with Bangladesh, pointing to some local collusion.[103] There were also reports of one SIM card purchased in New Jersey, USA.[104] Police had also mentioned that Faheem Ansari, an Indian Lashkar operative who had been arrested in February 2008, had scouted the Mumbai targets for the November attacks.[105] Later, the police arrested two Indian suspects, Mikhtar Ahmad, who is from Srinagar in Kashmir, and Tausif Rehman, a resident of Kolkata. They supplied the SIM cards, one in Calcutta, and the other in New Delhi.[106]

Type 86 Grenades made by China's state-owned Norinco were used in the attacks.[107]

Blood tests on the attackers indicate that they had taken cocaine and LSD during the attacks, to sustain their energy and stay awake for 50 hours. Police say that they found syringes on the scenes of the attacks. There were also indications that they had been taking steroids.[108] The gunman who survived said that the attackers had used Google Earth to familiarise themselves with the locations of buildings used in the attacks.[109]

There were ten gunmen, nine of whom were subsequently shot dead and one captured by security forces.[110][111] Witnesses reported that they looked to be in their early twenties, wore black t-shirts and jeans, and that they smiled and looked happy as they shot their victims.[112]

It was initially reported that some of the attackers were British citizens,[113][114] but the Indian government later stated that there was no evidence to confirm this.[115] Similarly, early reports of twelve gunmen[116] were also later shown to be incorrect.[3]

On 9 December, the ten attackers were identified by Mumbai police, along with their home towns in Pakistan: Ajmal Amir from Faridkot, Abu Ismail Dera Ismail Khan from Dera Ismail Khan, Hafiz Arshad and Babr Imran from Multan, Javed from Okara, Shoaib from Narowal, Nazih and Nasr from Faisalabad, Abdul Rahman from Arifwalla, and Fahad Ullah from Dipalpur Taluka. Dera Ismail Khan is in the North-West Frontier Province; the rest of the towns are in Pakistani Punjab.[117]

On 6 April 2010, the Home minister of Maharashtra State, which includes Mumbai, informed the assembly that the bodies of the nine killed Pakistani gunmen from the 2008 attack on Mumbai were buried in a secret location in January 2010. The bodies had been in the mortuary of a Mumbai hospital after Muslim clerics in the city refused to let them be buried on their grounds.[118]

Arrests

Ajmal Kasab was the only attacker captured alive by police and is currently under arrest.[119] Much of the information about the attackers' preparation, travel, and movements comes from his confessions to the Mumbai police.[120]

On 12 February 2009 Pakistan's Interior Minister Rehman Malik said that Pakistani national Javed Iqbal, who acquired VoIP phones in Spain for the Mumbai attackers, and Hamad Ameen Sadiq, who had facilitated money transfer for the attack, had been arrested.[86] Two other men known as Khan and Riaz, but whose full names were not given, were also arrested.[121] Two Pakistanis were arrested in Brescia, Italy, on 21 November 2009, after being accused of providing logistical support to the attacks.[122]

In October 2009, two Chicago men were arrested and charged by the FBI for involvement in terrorism abroad, David Coleman Headley and Tahawwur Hussain Rana. Headley, a Pakistani-American, was charged in November 2009 with scouting locations for the 2008 Mumbai attacks.[123][124] Headley is reported to have posed as an American Jew and is believed to have links with designated terrorist outfits based in Bangladesh.[125] On 18 March 2010, Headley pled guilty to a dozen charges against him thereby avoiding going to trial.

In December 2009, the FBI charged Abdur Rehman Hashim Syed, a retired major in the Pakistani army, for planning the terror attacks in association with Headley.[126]

On 15 January 2010, in a successful snatch operation R&AW agents nabbed Sheikh Abdul Khwaja, one of the handlers of the 26/11 attacks, chief of HuJI India operations and a most wanted terror suspect in India, from Colombo, Sri Lanka, and brought him over to Hyderabad, India for formal arrest.[127]

Downgraded security

Six days before the attack, barricades were removed along with metal detectors and frisking was stopped.[128]

Casualties and compensation

At least 166 victims (civilians and security personnel) and nine attackers were killed in the attacks. Among the dead were 28 foreign nationals from 10 countries.[2][47][129][130][131] One attacker was captured.[132] The bodies of many of the dead hostages showed signs of torture or disfigurement.[133] A number of those killed were notable figures in business, media, and security services.[134][135][136]

The government of Maharashtra announced about ₹500,000 (US$6,000) as compensation to the kin of each of those killed in the terror attacks and about ₹50,000 (US$600) to the seriously injured.[137] In August 2009, Indian Hotels Company and the Oberoi Group received about $28 million as part-payment of the insurance claims, on account of the attacks on Taj Mahal and Trident, from General Insurance Corporation of India.[138]

Aftermath

The attacks are commonly referred to in India as "26/11", after the date in 2008 that they began. A commission of inquiry appointed by the Maharashtra state government produced a report that was tabled before the assembly over one year after the events. The report said the "war-like" attack was beyond the capacity of any police force, but it also found fault with the city Police Commissioner's lack of leadership during the crisis.[139]

The Maharashtra state government has planned to buy 36 speed boats to patrol the coastal areas and several helicopters for the same purpose. It will also create an anti-terror force called "Force One" and upgrade all the weapons that Mumbai police currently have.[140] Prime Minister Dr. Manmohan Singh on an all-party conference declared that legal framework will be strengthened in the battle against terrorism and a federal anti-terrorist intelligence and investigation agency, like the FBI, will be set up soon to coordinate action against terrorism.[141] The government strengthened anti-terror laws with UAPA 2008, and the federal National Investigating Agency was formed.

The attacks have damaged India's already-strained relationship with Pakistan. External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee declared that India may indulge in military strikes against terror camps in Pakistan to protect its territorial integrity. There were also after-effects on the United States's relationships with both countries,[142] the US-led NATO war in Afghanistan,[143] and on the Global War on Terror.[144] According to Interpol secretary general Ronald Noble, Indian intelligence agencies did not share any information with them.[145] However, FBI chief Robert Mueller praised the "unprecedented cooperation" between American and Indian intelligence agencies over Mumbai terror attack probe.[146]

Movement of troops

Pakistan moved troops towards the border with India border voicing concerns about the Indian government's possible plans to launch attacks on Pakistani soil if it did not cooperate. After days of talks, the Pakistan government, however, decided to start moving troops away from the border.[147]

Reactions

Indians criticised their political leaders after the attacks, saying that their ineptness was partly responsible. The Times of India commented on its front page that "Our politicians fiddle as innocents die."[148] Political reactions in Mumbai and India included a range of resignations and political changes, including the resignations of Minister for Home Affairs, Shivraj Patil,[149] Chief Minister of Maharashtra, Vilasrao Deshmukh,[150] and Deputy Chief Minister of Maharastra R. R. Patil.[151] Prominent Muslim personalities such as Bollywood actor Aamir Khan appealed to the community members in the country to observe Eid al-Adha as a day of mourning on 9 December 2008.[152] The business establishment also reacted, with changes to transport, and requests for an increase in self-defense capabilities.[153] The attacks also triggered a chain of citizens' movements across India such as the India Today Group's "War Against Terror" campaign. There were vigils held across all of India with candles and placards commemorating the victims of the attacks.[154] The NSG commandos based in Delhi also met criticism for taking 10 hours to reach the 3 sites under attack.[155][156]

International reaction for the attacks was widespread, with many countries and international organizations condemning the attacks and expressing their condolences to the civilian victims. Many important personalities around the world also condemned the attacks.[157] Outgoing US President George W. Bush said "We pledge the full support of the United States as India investigates these attacks, brings the guilty to justice and sustains its democratic way of life."[158] Likewise, a spokesman for then President-elect Barack Obama said that Obama "strongly condemns today’s terrorist attacks in Mumbai, and his thoughts and prayers are with the victims, their families, and the people of India."[159]

Media coverage highlighted the use of new media and Internet social networking tools, including Twitter and Flickr, in spreading information about the attacks. In addition, many Indian bloggers and Wikipedia offered live textual coverage of the attacks.[160] A map of the attacks was set up by a web journalist using Google Maps.[161][162] The New York Times, in July 2009, described the event as "what may be the most well-documented terrorist attack anywhere."[163]

In November 2010, families of American victims of the attacks filed a lawsuit in Brooklyn, New York, naming Lt. Gen. Ahmed Shuja Pashathe, chief of the I.S.I., as being complicit in the Mumbai attacks.[100]

Kasab's trial

Kasab's trial was delayed due to legal issues, as many Indian lawyers were unwilling to represent him. A Mumbai Bar Association passed a resolution proclaiming that none of its members would represent Kasab. However, the Chief Justice of India stated that Kasab needed a lawyer for a fair trial. A lawyer for Kasab was eventually found, but was replaced due to a conflict of interest. On 25 February 2009, Indian investigators filed an 11,000-page chargesheet, formally charging Kasab with murder, conspiracy, and waging war against India among other charges.

Kasab's trial began on 6 May 2009. He initially pleaded not guilty, but later admitted his guilt on 20 July 2009. He initially apologized for the attacks and claimed that he deserved the death penalty for his crimes, but later retracted these claims, saying that he had been tortured by police to force his confession, and that he had been arrested while roaming the beach. The court had accepted his plea, but due to the lack of completeness within his admittance, the judge had deemed that many of the 86 charges were not addressed and therefore the trial continued.

Kasab was convicted of all 86 charges on 3 May 2010. He was found guilty of murder for directly killing seven people, conspiracy to commit murder for the deaths of the 166 people killed in the three-day terror siege, waging war against India, causing terror, and of conspiracy to murder two high-ranking police officers. On 6 May 2010, he was sentenced to death by hanging.[164] [165] [166] [167] However, he appealed his sentence.[citation needed]

Trials in Pakistan

Indian and Pakistani police have exchanged DNA evidence, photographs and items found with the attackers to piece together a detailed portrait of the Mumbai plot. Police in Pakistan have arrested seven people, including Hammad Amin Sadiq, a homeopathic pharmacist, who arranged bank accounts and secured supplies. Sadiq and six others begin their formal trial on 3 October 2009 in Pakistan, though Indian authorities say the prosecution stops well short of top Lashkar leaders.[168] In November 2009, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said that Pakistan has not done enough to bring the perpetrators of the attacks to justice.[169]

On the eve of the first anniversary of 26/11, a Pakistani anti-terror court formally charged seven accused, including LeT operations commander Zaki ur Rehman Lakhvi.

Locations

All the incidents except the explosion at Vile Parle took place in downtown South Mumbai.

- Oberoi Trident at Nariman Point; 18°55′38″N 72°49′14″E / 18.927118°N 72.820618°E

- Taj Mahal Palace & Tower near the Gateway of India; 18°55′18″N 72°50′00″E / 18.921739°N 72.83331°E

- Leopold Cafe, a popular tourist restaurant in Colaba; 18°55′20″N 72°49′54″E / 18.922272°N 72.831566°E

- Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus (CST) railway station; 18°56′26″N 72°50′11″E / 18.940631°N 72.836426°E (express train terminus), 18°56′26″N 72°50′07″E / 18.94061°N 72.835343°E (suburban terminus)

- Badruddin Tayabji Lane behind the Times of India building.18°56′32″N 72°50′01″E / 18.942117°N 72.833734°E

- Near St. Xavier's College 18°56′38″N 72°49′55″E / 18.943919°N 72.831942°E.

- Cama and Albless Hospital; 18°56′34″N 72°49′59″E / 18.94266°N 72.832993°E

- Nariman House (Chabad House) Jewish outreach center; 18°54′59″N 72°49′40″E / 18.916517°N 72.827682°E

- Metro Cinema 18°56′35″N 72°49′46″E / 18.943178°N 72.829474°E

- Mazagaon docks in Mumbai's port area;

- Vile Parle near the airport

Memorials

On the first anniversary of the event, the state paid homage to the victims of the attack. [[Force One]—-a new security force created by the Maharashtra government—-staged a parade from Nariman Point to Chowpatty. Other memorials and candlelight vigils were also organised at the various locations where the attacks occurred.[170]

On the second anniversary of the event, homage was again paid to the victims.[171] Security forces were also displayed from Nariman Point.

See also

References

- ^ Magnier, Mark; Sharma, Subhash (27 November 2008). "India terrorist attacks leave at least 101 dead in Mumbai". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d "HM announces measures to enhance security" (Press release). Press Information Bureau (Government of India). 11 December 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- ^ a b c Somini Sengupta (6 January 2009). "Dossier From India Gives New Details of Mumbai Attacks". The New York Times accessdate=14 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Maseeh Rahman (27 November 2008). "Mumbai terror attacks: Who could be behind them?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Press Trust of India (27 November 2008). "Army preparing for final assault, says Major General Hooda". The Times of India. Retrieved 10 December 2008.

- ^ "India Blames Pakistan as Mumbai Siege Ends". DW. 29 November 2008.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas (17 February 2009). "No Way, No How, Not Here". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ Indian Muslims hailed for not burying 26/11 attackers, Sify News, 19 February 2009

- ^ Schifrin, Nick (25 November 2009). "Mumbai Terror Attacks: 7 Pakistanis Charged – Action Comes a Year After India's Worst Terrorist Attacks; 166 Die". ABC News. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ Black, Ian (28 November 2008). "Attacks draw worldwide condemnation". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Wave of Terror Attacks Strikes India's Mumbai, Killing at Least 182". Fox News. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Kahn, Jeremy (2 December 2008). "Jews of Mumbai, a Tiny and Eclectic Group, Suddenly Reconsider Their Serene Existence". New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Magnier, Mark (3 December 2008). "Mumbai police officers describe nightmare of attack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ a b "Tracing the terror route". Indian Express. India. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Police declare Mumbai siege over". BBC. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ "Terrorist's name lost in transliteration". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- ^ "Lashkar-e-Taiba (Army of the Pure) (aka Lashkar e-Tayyiba, Lashkar e-Toiba; Lashkar-i-Taiba) – Council on Foreign Relations". Cfr.org. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric. "U.S. and India See Link to Militants in Pakistan". New York Times date=3 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Somini Sengupta and Eric Schmitt (3 December 2008). "Ex-U.S. Official Cites Pakistani Training for India Attackers". The New York Times accessdate=14 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ a b "Pakistan Continues to Resist India Pressure on Mumbai". TIME. 8 January 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Surviving gunman's identity established as Pakistani". Dawn. 7 January 2009. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Masood, Salman. "Pakistan Says Mumbai Attack Partly Planned on Its Soil". The New York Times date=12 February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ "1993: Bombay hit by devastating bombs". BBC. 12 March 1993. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ Monica Chadha (12 September 2006). "Victims await Mumbai 1993 blasts justice". BBC. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- ^ "Blast outside Ghatkopar station in Mumbai, 2 killed". rediff.com India Limited. 6 December 2002. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "1992: Mob rips apart mosque in Ayodhya". BBC. 6 December 1992. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "1 killed, 25 hurt in Vile Parle blast". The Times of India. India. 28 January 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Fear after Bombay train blast". BBC. 14 March 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ Vijay Singh, Syed Firdaus Ashra (29 July 2003). "Blast in Ghatkopar in Mumbai, 4 killed and 32 injured". rediff.com India Limited. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "2003: Bombay rocked by twin car bombs". BBC. 25 August 2003. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "For the record: The 11/7 chargesheet". rediff.com India Limited. 11 July 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "India: A major terror target". The Times of India. India. 30 October 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "'Rs 50, 000 not enough for injured'". Indian Express Newspapers (Mumbai) Ltd. 21 July 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "India police: Pakistan spy agency behind Mumbai bombings". CNN. 1 October 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai Police blames ISI, LeT for 7/11 blasts". The Times of India. India. 30 September 2006. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Moreau, Ron (27 November 2008). "The Pakistan Connection". Newsweek. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "3 witnesses identify Kasab, court takes on record CCTV footage". The Economic Times. India. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Photographer recalls Mumbai attacks". The News International. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Info from cop in Karkare's jeep led to Kasab's arrest". Mid Day. 3 December 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai gunman guilty of 'act of war'". The_National_(Abu_Dhabi). 4 May 2010.

- ^ "Jukexboxes on the Moon: Stardom is martyrdom: India arrives in the American imagination". Triple Canopy.

- ^ Blakely, Rhys; Page, Jeremy (1 December 2008). "Defiant Leopold café shows that Mumbai is not afraid". The Times. London. Retrieved 19 March 2009.

- ^ "Leopold Cafe reopens amidst desolation". Deccan Herald. India. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Mumbai attack: Timeline of how the terror unfolded". Daily Mirror. UK. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- ^ "Taj Hotel Burns, 2 Terrorists Killed". CNN IBN. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Taj Hotel Attacked". TTKN News. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Scores killed in Mumbai rampage". CNN. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ Andrew Stevens, Mallika Kapur, Phil O'Sullivan, Phillip Turner, Ravi Hiranand, Yasmin Wong and Harmeet Shah Singh (27 November 2008). "Fighting reported at Mumbai Jewish center". CNN. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pasricha, Anjana (27 November 2008). "Commandos Launch Operations to Clear Luxury Hotels Seized by Gunmen in Mumbai". VOA News. Voice of America.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)[dead link] - ^ "We want all Mujahideen released: Terrorist inside Oberoi". The Times of India. India. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ Patrick Frater (30 November 2008). "Indian journalists in media firestorm". Variety. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai operation appears nearly over". CNN. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ "Oberoi standoff ends". CNN. 28 November 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ^ "Terrorists had no plan to blow up Taj: NSG DG". Rediff. Retrieved 26 November 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "NSG commando recounts gunfight with terrorists". CNN IBN. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Charter, David (27 November 2008). "Tory MEP flees for his life as gunman starts spraying the hotel bar with bullets". London: The Times. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ^ "EU trade delegation in Mumbai safe, delegate says". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ a b c Charter, David (27 November 2008). "Tory MEP flees for his life as gunman starts spraying the hotel bar with bullets". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "EU parliament staff member wounded in India shootout". EU business. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Relacja Polaka z piekła" (in Polish). Reuters, TVN24. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ a b "EU parliament staff member wounded in India shootout". The Times of India. India. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Press Trust of India (27 November 2008). "200 people held hostage at Taj Hotel". NDTV. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Thomson, Alice (27 November 2008). "Sir Gulam Noon, British 'Curry King': how I escaped bombed hotel". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vaakov Lappin (29 November 2008). "Consulate: Unspecified number of Israelis missing in Mumbai". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 27 November 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "NSG ends reign of terror at Nariman". Times of India. India. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2009.

- ^ Daniel Trotta (28 November 2008). "Rabbi killed in Mumbai had gone to serve Jews". Reuters. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Mumbai terror attacks: And then they came for the Jews – Times Online[dead link]

- ^ Keith Bradsher and Somini Sengupta. "Commandos storm Jewish center in Mumbai". International Herald Tribune date=28 November 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ "Mumbai takes back control from terrorists". TTKN Oxford. 28 November 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ a b c "Gunbattle enters third day, intense firing at Taj hotel". 28 November 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ "Taj operation over, three terrorists killed". Hindustan Times. India. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "Battle for Mumbai ends, death toll rises to 195". The Times of India. India. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Timeline: one night of slaughter and mayhem". Evening Standard. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ Terror Ties Run Deep in Pakistan, Mumbai Case Shows, New York Times, Jane Perlez and Salman Masood, 26 July 2009

- ^ a b Schmitt, Eric. "Ex-U.S. Official Cites Pakistani Training for India Attackers". The New York Times date=3 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hussain, Zahid. "Islamabad Tells of Plot by Lashkar". Wall Street Journal date = 28 July 2009. Islamabad. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Schifrin, Nick (25 November 2009). "Mumbai terror attacks: 7 Pakistanis charged". ABC News. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ Rhys Blakely (26 February 2009). "Pakistani Army colonel 'was involved' in Mumbai terror attacks". London: TimesOnline. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ^ "Who are David Headley, Tahawwur Rana?". CNN IBN. 17 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ Mohan, Vishwa (7 November 2009). "Headley link traced to Pak, 2 LeT men arrested". Times of India. India. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- ^ "Investigators see Bangladesh link in Mumbai terror attacks". Dawn. 9 February 2009. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 10 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chidambaram asserts 26/11 originated from Pak soil". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 February 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Shakeel Ahmad (16 February 2009). "Samjhota, Mumbai attacks linked, says Qureshi". Dawn. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ^ a b "Gunman in Mumbai Siege a Pakistani, Official Says". The New York Times author=Richard A. Oppel and Salman Masood. 7 January 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Mubashir Zaidi (7 January 2009). "Surviving gunman's identity established as Pakistani". Dawn. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Part of 26/11 plan made on our land, admits Pakistan". NDTV. 12 February 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ Anirban Bhaumik (4 January 2009). "PC heads for US with 26/11 proof". Deccan Herald. India. Retrieved 21 February 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Rupert, James (28 January 2009). "Pakistan's Partial Crackdown Lets Imams Preach Jihad". Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ^ Praveen Swami (23 November 2009). "Missing evidence mars Mumbai massacre probe". Chennai, India: The Hindu.

- ^ Reporters Without Borders (13 November 2009). "Two journalists held after helping media probe Mumbai attacker's background". Reporters Without Borders.

- ^ Nirupama Subramanian (24 November 2009). "Kasab's village remains a no-go area for journalists". The Hindu.

- ^ PTI (1 December 2009). "No information on Headley, Rana from Pakistan, says Home Minister Chidambaram". Times of India.

- ^ a b "Indian gov't: Pakistan spies tied to Mumbai siege". news.yahoo.com. Associated Press. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Report: Pakistan Spies Tied to Mumbai Siege". Fox News. Associated Press. 19 October 2010. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ http://www.propublica.org/article/mumbai-case-offers-rare-picture-of-ties-between-pakistans-intelligence-serv

- ^ "Slain navigator of Porbandar trawler was imprisoned in Pak". The Times of India. India. 30 September 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Terror boat was almost nabbed off Mumbai". The Times of India. India. 10 December 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- ^ a b New York Times, 2010 Oct. 16, "U.S. Had Warnings on Plotter of Mumbai Attack," http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/17/world/asia/17headley.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&ref=global-home

- ^ Pro Publica, 2010 Oct. 15, "FBI Was Warned Years in Advance of Mumbai Attacker’s Terror Ties," http://www.propublica.org/article/mumbai-plot-fbi-was-warned-years-in-advance

- ^ a b New York Times, 2010 Dec. 17, "Top U.S. Spy Leaves Pakistan After His Name Is Revealed," http://www.nytimes.com/2010/12/18/world/asia/18pstan.html?hp

- ^ Ali, S Ahmed (30 November 2008). "Mumbai locals helped us, terrorist tells cops". The Times of India. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Sheela Bhatt (27 November 2008). "Exclusive: LeT terrorist Ismail arrested in Mumbai". Rediff.com. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Ishaan Tharoor (4 December 2008). "Pakistani Involvement in the Mumbai Attacks". TIME. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Rhys Blakely (4 December 2008). "Mumbai gunman says he was paid $1,900 for attack – as new CCTV emerges". The Times. London. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Indian 'scouted attack' in Mumbai". Herald Sun. 6 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Two men accused of providing SIM cards to Mumbai attackers". CBC News. 6 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "India's China Problem –". Forbes.com. 13 August 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ Damien McElroy (3 December 2008). "Mumbai attacks Terrorists took cocaine to stay awake during assault". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Rahul Bedi (9 December 2008). "Mumbai attacks: Indian suit against Google Earth over image use by terrorists". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Somini Sengupta and Keith Bradsher. "India Faces Reckoning as Terror Toll Eclipses 170". The New York Times date=29 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Rakesh Prakash (29 November 2008). "Please give me saline". The Times of India. India. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Ramesh, Randeep (28 November 2008). "They were in no hurry. Cool and composed, they killed and killed". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Balakrishnan, Angela (28 November 2008). "Claims emerge of British terrorists in Mumbai". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- ^ Tom Morgan (28 November 2008). "Arrested Mumbai gunmen 'of British descent'". The Independent. London. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ Jon Swaine (28 November 2008). "Mumbai attack: Government 'has no evidence of British involvement'". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ McElroy, Damien (6 December 2008). "Mumbai attacks: police admit there were more than ten attackers". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- ^ "Mumbai Attackers Called Part of Larger Band of Recruits". The New York Times author=Jeremy Kahn and Robert F. Worth. 9 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ Bodies of nine Mumbai gunmen buried secretly in JanReuters, Tue 6 Apr 2010 10:26 pm IST

- ^ Swami, Praveen (2008-12-92). "A journey into the Lashkar". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Planned 9/11 at Taj, reveals caught terrorist". Zee News. 29 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Kamran Haider (12 February 2009). "Pakistan says it arrests Mumbai attack plotters". Yahoo News. Retrieved 21 February 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Italy arrests two for Mumbai attacks". The Hindu. India. 21 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Mumbai police probe David Headley's links to 26/11 attacks". Daily News and Analysis. India. 8 November 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "India Plans to Try Chicago Man For Mumbai Attacks". Reuters. 8 December 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Josy Joseph (9 November 2009). "David Headley posed as Jew in Mumbai". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ ET Bureau (9 December 2009). "FBI nails Pak Major for Mumbai attacks". India Times. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- ^ 26/11 attacks handler arrested Hindustan Times, Abhishek Sharan & Ashok Das, Delhi/Hyderabad, 18 January 2010

- ^ "Insider whiff in Taj attack". Dnaindia.com. 3 December 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Indian forces storm Jewish centre". BBC News. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "One Japanese killed, another wounded in Mumbai shootings". Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 26 November 2008.

- ^ P.S. Suryanarayana (27 November 2008). "Caught in the crossfire, 9 foreign nationals killed". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ Stevens, Andrew (29 November 2008). "Indian official: Terrorists wanted to kill 5,000". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Krishnakumar P and Vicky Nanjappa (30 November 2008). "Rediff: Doctors shocked at hostages's torture". Rediff.com. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Naughton, Philippe (27 November 2008). "British yachting tycoon Andreas Liveras killed in Bombay terror attacks". The Times. London. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Three top cops die on duty". The Times of India. India. 27 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Indian victims include financier, journalist, actor's sister, police". CNN. 30 November 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Key developments in Mumbai terror attacks". The Hindu. India. 27 November 2008.

- ^ "Taj, Oberoi get Rs 140 cr as terror insurance claims so far". The Hindu Business Line. 15 August 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ “There was absence of overt leadership on the part of Hasan Gafoor, the CP, and lack of visible Command and Control at the CP’s office,” said the report prepared by former Governor and Union Home Secretary R.D. Pradhan. PTI (21 December 2009). "Pradhan Committee finds serious lapses on Gafoor's part". Nagpur: The Hindu.

- ^ Sapna Agarwal (27 December 2008). "No consensus on security plan even a month after Mumbai attacks". Business Standard. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "PM for federal agency, better legal framework". NDTV. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Mumbai attacks probed as India-Pakistan relations strained". CNN. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Jeremy Page, Tom Coghlan, and Zahid Hussain (1 December 2008). "Mumbai attacks 'were a ploy to wreck Obama plan to isolate al-Qaeda'". The Times. London. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "'Don't look at Mumbai attacks through prism of Kashmir'". Rediff News. Rediff.com. 16 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Interpol 'not given Mumbai data'". BBC. 23 December 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "FBI chief hails India cooperation after Mumbai attacks". The Economic Times. India. 3 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/India/Pak-might-soon-move-troops-from-border-with-India/articleshow/4660681.cms.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "India directs anger at politicians after Mumbai attacks". 1 December 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Officials quit over India attacks". BBC. 30 November 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Aditi Pai (4 December 2008). "Vilasrao Deshmukh quits as Maharashtra CM". India Today. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Maharashtra Deputy CM RR Patil resigns". CNN-IBN. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Muslims Condemn Mumbai Attacks, Call for Black Eid". Outlook. 4 December 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Erika Kinetz (17 December 2008). "Mumbai attack dents business travel". Yahoo!. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ "Be the change". India Today Bureau. India Today. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Sharma, Aman (29 November 2008). "Red tape delays NSG by 6 hours". India Today. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Why did NSG take 10 hours to arrive?". The Economic Times. India. 30 November 2008. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- ^ Rivers, Tom (27 November 2008). "Mumbai Attacks Draw Worldwide Condemnation". Voice Of America. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) [dead link] - ^ "Shock in US over Mumbai assault, Bush pledges help". Google. 2008=11–27. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Bush, Obama condemn Mumbai terror attacks". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Claudine Beaumont (27 November 2008). "Mumbai attacks: Twitter and Flickr used to break news". London: The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

- ^ Robert Mackey. "Tracking the Mumbai Attacks". The New York Times date=26 November 2008. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help) - ^ "Google Maps". Google. 26 November 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (20 July 2009). "Suspect Stirs Mumbai Court by Confessing". The New York Times accessdate=21 July 2009.

{{cite news}}: Missing pipe in:|work=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Mumbai gunman sentenced to death". BBC News. 6 May 2010.

- ^ Chamberlain, Gethin (3 May 2010). "Mumbai gunman convicted of murder over terror attacks". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ "26/11: Kasab guilty; Ansari, Sabauddin Shaikh acquitted". The Times of India. 3 May 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Deshpande, Swati (3 May 2010). "26/11 Kasab held guilty 2 Indians walk free". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Officials Fear New Mumbai-Style Attack, Lydia Polgreen and Souad Mekhennet, New York Times, 30 September 2009

- ^ Fareed Zakaria, transcript of CNN interview with Manmohan Singh (23-Nov-2009). "Pakistan has not done enough on attacks". Wall Street Journal.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Mumbai bustles but also remembers 26/11 victims". CNN IBN. Retrieved 26 November 2009.

- ^ Harmeet Shah Singh. "India remembers Mumbai dead - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

External links

- Channel 4 documentary by Dan Reed – 'Terror in Mumbai'

- Video showing the way in which Indian authorities fought back against the attackers. - CNN-IBN (some Hindi, but mostly English).

- Dossier of evidence collected by investigating agencies of India

- List of Blogs & Bloggers who were live blogging during the attacks

- If Each Of Us Had A Gun We Could Help Combat Terrorism - Journalist Richard Munday talks about the horrific terrorist attacks in Mumbai, India

Template:Navbox 2008 Mumbai attacks