Republic of Crimea

Republic of Crimea

| |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Нивы и горы твои волшебны, Родина Nivy i gory tvoi volshebny, Rodina (Russian) "Your fields and mountains are magical, Motherland"[citation needed] | |

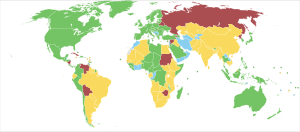

Location of the Republic of Crimea (red) in Russia (light yellow) | |

Location of the Republic of Crimea (light yellow) in the Crimean Peninsula | |

| Coordinates: 45°18′N 34°24′E / 45.3°N 34.4°E | |

| Federal district | Southern[1] |

| Economic region | North Caucasus |

| Capture of the Crimean parliament by Russian forces | 27 February 2014 |

| Annexation by Russia | 18 March 2014[2] |

| Administrative centre | Simferopol |

| Government | |

| • Body | State Council |

| • Head | Sergey Aksyonov[3] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26,081 km2 (10,070 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[5] | |

| • Total | 1,934,630 |

| • Density | 74/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK[8]) |

| License plates | 82[9][10] |

| Website | crimea |

The Republic of Crimea[b] is a republic of Russia, comprising most of the Crimean Peninsula, but excluding Sevastopol.[11] Its territory corresponds to the pre-2023[12] territory of Autonomous Republic of Crimea, a subdivision of Ukraine. Russia occupied and annexed the peninsula in 2014, although the annexation remains internationally unrecognized.[13]

The capital and largest city located within its borders is Simferopol, which is the second-largest city on the Crimean Peninsula. As of the 2021 Russian census, the Republic of Crimea had a population of 1,934,630.[5]

History

2014 annexation

In February 2014, following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution that ousted the Ukrainian President, Viktor Yanukovych, the Russian leadership decided to "start working on returning Crimea to Russia"[14] (i.e. envisaged the annexation of the peninsula), and after a takeover of Crimea by Russian armed forces without insignias and pro-Russian separatists, the territory within weeks came under Russian effective control.

To facilitate the annexation politically,[15] on 6 March the Crimean parliament and the Sevastopol City Council announced a referendum on the issue of joining Russia. This referendum, the holding of which was a violation of the Ukrainian Constitution,[16] was to be held on 16 March. The upcoming vote allowed citizens to vote on whether Crimea should apply to join Russia as a federal subject of the Russian Federation, or restore the 1992 Crimean constitution and Crimea's status as a part of Ukraine. The available choices did not include keeping the status quo of Crimea and Sevastopol as they were at the time the referendum was held.[17]

On 11 March 2014, the Crimean parliament and the Sevastopol City Council jointly issued a letter of intent to unilaterally declare independence from Ukraine in the event of a "Yes" vote in the upcoming referendum, citing the "Kosovo precedent" in the lead part.[18] The envisaged process was so designed to allow Russia to claim that "it did not annex Crimea from Ukraine, rather the Republic of Crimea exercised its sovereign powers in seeking a merge with Russia".[19]

On 16 March 2014, according to the organizers of Crimean status referendum, a large majority (reported as 96.77% of the 81.36% of the population of Crimea who voted) voted in favour of independence of Crimea from Ukraine and joining Russia as a federal subject.[20][21][22][23] The referendum was not recognized by most of the international community and the reported results were disputed by numerous independent observers.[24][25][26][27][28] The BBC reported that most of the Crimean Tatars that they interviewed were boycotting the vote.[20] Reports from the UN criticised the circumstances surrounding the referendum, especially the presence of paramilitaries, self-defence groups and unidentifiable soldiers.[29] The European Union, Canada, Japan and the United States condemned the vote as illegal.[20][30]

After the referendum, Crimean lawmakers formally voted both to secede from Ukraine and applied for their admission into Russia. The Sevastopol City Council, however, requested the port's separate admission as a federal city.[31] On the same day Russia formally approved the draft treaty on absorption of the self-proclaimed Republic of Crimea,[32][33] and on 18 March 2014 the political process of annexation was formally concluded,[15] with the self-proclaimed independent Republic of Crimea signing a treaty of accession to the Russian Federation.[34] The accession was granted but separately for each the former regions that composed it: one accession for the Autonomous Republic of Crimea as the Republic of Crimea—the same name as the short-lived self-proclaimed independent republic—and another accession for Sevastopol as a federal city. A post-annexation transition period, during which Russian authorities were to resolve the issues of integration of the new subjects "in the economic, financial, credit and legal system of the Russian Federation", was set to last until 1 January 2015.[35]

The change of status of Crimea was only recognised internationally by a few states with most regarding the action as illegal. Ukraine refused to accept the annexation, however the Ukrainian military began to withdraw from Crimea on 19 March,[36] and by 26 March, Russia had acquired complete military control of Crimea, so the annexation was essentially complete.[37]

Post-annexation integration

The post-annexation integration process started within days. On 24 March, the Russian ruble went into official circulation with parallel circulation of the Ukrainian hryvnia permitted until 1 January 2016, however, taxes and fees were to be paid in rubles only, and the wages of employees at budget-receiving organisations were to be paid out in rubles as well.[38] On 29 March, the clocks in Crimea were moved forward to Moscow time.[39] Also on 31 March, the Russian Foreign Ministry declared that foreign citizens visiting Crimea needed to apply for a visa to the Russian Federation at one of Russian diplomatic missions or its consulates.[citation needed]

On 3 April 2014, Moscow sent a diplomatic note to Ukraine on terminating the actions of agreements concerning the deployment of the Russian Federation's Black Sea Fleet on the territory of Ukraine. As part of the agreements, Russia used to pay the Ukrainian government $530 million annually for the base, and wrote off nearly $100 million of Kyiv's debt for the right to use Ukrainian waters. Ukraine also received a discount of $100 on each 1,000 cubic meters of natural gas imported from Russia, which was provided for by cutting export duties on the gas, money that would have gone into the Russian state budget. The Kremlin explained that because the base was no longer located in Ukraine, the discount was no longer legally justifiable.[40] Crimea and the city of Sevastopol became part of Russia's Southern Military District.[41]

On 11 April 2014, the parliament of Crimea approved a new constitution, with 88 out of 100 lawmakers voting in favor of its adoption.[42] The new constitution confirms the Republic of Crimea as a democratic state within the Russian Federation and declares both territories united and inseparable. The Crimean parliament would become smaller and have 75 members instead of the current 100.[43] According to the Kommersant newspaper, the authorities, including the State Council chair Vladimir Konstantinov, unofficially promised that certain quotas would be reserved for Crimean Tatars in various government bodies.[citation needed] On the same day, a new revision of the Russian Constitution was officially published, with the Republic of Crimea and the federal city of Sevastopol included in the list of federal subjects of the Russian Federation.[44]

On 12 April 2014, the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea, adopted at the session of the State Council on 11 April, entered into legal force. The constitution was published by the Krymskiye Izvestiya newspaper, becoming law on the publication date, the State Council of Crimea said. The Constitution consists of 10 chapters and 95 articles; its main regulations are analogous to the articles of the Constitution of the Russian Federation. The text proclaims the Republic of Crimea is a democratic, legal state within the Russian Federation and an equal subject of the Russian Federation. The source of power in the Crimean Republic is its people, which constitutes to the multinational nation of the Russian Federation. It is noted that the supreme direct manifestation of the power of the people is referendum and free elections; seizure of power and appropriation of power authorization are unacceptable.[citation needed]

On 1 June 2014, Crimea officially switched over to the Russian ruble as its only form of legal tender.[45]

On 7 May 2015, Crimea switched its phone codes (Ukrainian number system) to the Russian number system.[46]

In July 2015, Russian Prime Minister, Dmitry Medvedev, declared that Crimea had been fully integrated into Russia,[47] similar statements were also expressed at the Russian Security Council.[48]

In July 2016, Crimea ceased to be a separate federal district of the Russian Federation and was included into the Southern federal district instead.[49][50]

Russia has since the annexation supported large migration into Crimea, and the Office of the Federal State Statistics Service in Crimea and Sevastopol records as of 2021 since 2014 205,559 Russians have moved to Crimea. Ukrainian Ministry and Crimean Human Rights Group say the real number could unofficially be many times higher.[51][52][53]

Infrastructure

On 31 March 2014, the Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev announced a series of programmes aimed at swiftly incorporating the territory into Russia's economy and infrastructure. The creation of a new Ministry of Crimean Affairs was announced too.[54] After 2014 the Russian government invested heavily in the peninsula's infrastructure—repairing roads, modernizing hospitals and building the Crimean Bridge that links the peninsula to the Russian mainland.

In 2017 the Russian government also began modernising the Simferopol International Airport,[55] which opened its new terminal in April 2018.[56]

Russia provides electricity to Crimea via a cable beneath the Kerch Strait. In June 2018 there was a full electrical outage for all of Crimea, but the power grid company Rosseti reported to have fixed the outage in approximately one hour.[57]

On 28 December 2018, Russia completed a high-tech security fence marking the border between Crimea and Ukraine.[58]

Ukrainian reaction

Once Ukraine lost control of the territory in 2014, it shut off the water supply of the North Crimean Canal which supplies 85% of the peninsula's freshwater needs from the Dnieper river, the nation's main waterway.[59] Development of new sources of water was undertaken, with huge difficulties, to replace closed Ukrainian sources.[60] In 2022, Russia conquered portions of Kherson Oblast, which allowed it to unblock the North Crimean canal by force, resuming water supply into Crimea.[61]

On 15 April 2014, the Ukrainian Parliament declared Crimea and the city of Sevastopol "occupied territories".[62]

In 2021, Ukraine launched the Crimea Platform a diplomatic initiative aimed at protecting the rights of Crimean inhabitants and ultimately reversing the illegal annexation of Crimea.[63]

Government and politics

The State Council of Crimea is a legislative body with a 75-seat parliament.[64] The polling held on 14 September 2014 resulted in United Russia securing 70 of the 75 members elected.[65]

Justice is administered by courts, as part of the judiciary of Russia. Under Russian law, all decisions delivered by the Crimean branches of the judiciary of Ukraine up to its annexation remain valid.[66] This includes sentences (for "encroaching on Ukraine's territorial integrity and inviolability") for pre-2014 calls for an incorporation of Crimea into Russia.[66]

The executive power is represented by the Council of Ministers, headed either by the Prime Minister of Crimea or by the Head of the Republic of Crimea. The authority and operation of the State Council and the Council of Ministers of Crimea are determined by the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea and other Crimean laws, as well as by regular decisions carried out by the Council.[67]

Crimeans who refused to take Russian citizenship are barred from holding government positions or municipal jobs.[68]

By July 2015, 20,000 Crimeans had renounced their Ukrainian citizenship.[69] From the time of Russia's annexation until October 2016, more than 8,800 Crimean residents received Ukrainian passports.[70]

On 18 September 2016, the whole of Crimea participated in the Russian legislative election.

Military

- Marine Corps of the Russia "little green men"

- Baherove (air base)

- Theodosius-13

- Southern Naval Base

Administrative divisions

The Republic of Crimea continues to use the administrative divisions previously used by the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and is thus subdivided into 25 regions: 14 districts (raions) and 11 city municipalities (gorodskoj sovet or gorsovet), officially known as territories governed by city councils.[71][failed verification]

Raions

|

City municipalities |

|

Geography

Political geography

Crimea's only land boundary is with mainland Ukraine, which continues to claim sovereignty over the peninsula, with a number of road and rail connections. These crossings have been under the control of Russian troops since at least mid-March 2014.

Crimea has no land connection to Russia. In 2014–2019, Russia built the Crimean Bridge, a multibillion-dollar road–rail fixed link across the Kerch Strait.[72] The link has been open for road traffic since 2018, and for rail traffic since 2019 (passenger) and 2020 (freight).[73][better source needed] During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine it became an important logistical link for Russian forces. In October 2022 it was badly damaged by an explosion.

Demographics

Life expectancy

According to the Russian occupation authorities, the best result in life expectancy the Republic of Crimea had in 2019, it reached 72.71 years. But during two years the COVID-19 pandemic the region had one of the largest summary fall in life expectancy in Russia, and in 2021 it became 69.70 years (65.31 for males and 73.96 for females)[74][75][better source needed]

-

Life expectancy with calculated differences

-

Life expectancy in the Republic of Crimea in comparison with Crimea on average and neighboring regions of the country

-

Life expectancy in the Republic of Crimea in comparison with Crimea on average (in detail)

Languages

According to the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea:[76][better source needed]

Article 10

- 1. Official languages of the Republic of Crimea are Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar.

According to the 2014 census by occupation authorities, 84% of Crimean inhabitants named Russian as their native language; 7.9% named Crimean Tatar; 3.7% Tatar and 3.3% Ukrainian. The previous census was held more than decade ago in 2001, when Crimea was still controlled by Ukraine.[77]

According to the Republic of Crimea Ministry of Education, Science, and Youth,[78] most primary and secondary school pupils have decided to study in Russian in 2015.

- In Russian – 96.74%

- In Crimean Tatar – 2.76%. 5083 pupils (+188 to 2014 year) study in Crimean Tatar language in 53 schools in 17 districts. 37 1st grade classes of primary school have been opened.

- In Ukrainian – 0.5%. 949 pupils study in Ukrainian language in 22 schools in 13 districts. 2 1st grade classes of primary school have been opened.

Its Education Minister Natalia Goncharova announced mid-August 2014 that (since no parents of first-graders wrote an application for learning Ukrainian) Crimea had decided not to form Ukrainian language classes in its primary schools.[79] Goncharova said that since more than a quarter of parents at the Ukrainian gymnasium in Simferopol had written an application to teach children in Ukrainian; this school might have Ukrainian language classes.[79] Goncharova also added that the parents of first-graders had written application for learning the Russian language, and (in areas inhabited by Crimean Tatars) for learning Crimean Tatar.[79] Goncharova stated on 10 October 2014 that at that time Crimea had 20 schools where all subjects were conducted in Ukrainian.[80]

A report (realised in the summer of 2015) of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) stated that the Republic of Crimea had the aim to "end the teaching of Ukrainian" by "pressure on school administrations, teachers, parents, and children".[81]

Religion

Religion in Crimea (2013)[82]

In 2013, before the Russian occupation, the majority of the Crimean population adhered to the Orthodox Church, with the Crimean Tatars forming a Sunni Muslim minority, besides smaller Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Greek Catholic, Armenian Apostolic and Jewish minorities. In 2013, Orthodox Christians made up 58% of the Crimean population, followed by Muslims (15%, mainly Tatars) and believers without religion (10%).[82]

Since 2014, the United Nations has reported a regime of human-rights violations imposed by the Russian occupation authorities, including targeting religious minority groups and individuals.[83][84]

Economy

Peninsula economy is based on tourism, agriculture (wines, fruits, wheat, rice and further crops), fishing, pearls, mining and natural resources (mainly iron, titanium, aluminium, manganese, calcite, sandstone, quartz and silicates, amethyst, other), metallurgical and steel industry, shipbuilding and repair, oil gas and petrochemical, chemical industry, electronics and devices machinery, instruments making, glass, electronics and electric parts devices, materials and building.

Overview

After annexation of the peninsula, Russia doubled payments to about 560,000 pensioners and 200,000 public workers (in Crimea).[85] Those raises were cut back in April 2015.[86]

In June 2015 The Economist estimated that the average salary in Crimea was about two-thirds of the average salary in Russia.[86] According to Russian statistics by March 2015 the inflation in Crimea was 80%.[87] According to the Crimean authorities local food prices have grown 2.5 times since Russia's annexation.[88] Since then the peninsula now has to import most of its food from Russia.

After the annexation, Russian Crimean authorities started nationalization of what they called strategically important enterprises, which included not only transportation and energy production enterprises, but also, for example, a wine factory in Massandra. The enterprises which belonged to Russian citizens were nationalized against financial reimbursement, which was, however, much lower than the actual value; those which belonged to Ukrainian citizens, for example, PrivatBank owned by Ihor Kolomoyskyi or Ukrtelecom owned by Rinat Akhmetov, were expropriated without any reimbursement. The future of the nationalized enterprises is decided by the government.[89] Reasons given for this were (among others) "the company helped to finance military operations against Donetsk People's Republic and Luhansk People's Republic" and "the resort complex illegally blocked public access to nearby park lands".[90] The government can nationalise assets considered to have "particular social, cultural, or historical value".[90] In the case of the Zalyv Shipbuilding yard, Crimean "self-defense" forces stormed the company's headquarters to demand nationalization.[90] Head of the Republic Sergey Aksyonov claimed that in at least one case "Employees established control of the enterprise on their own, we just helped them a little".[90] The nationalization of Ihor Kolomoyskyi's assets was, according to Aksyonov, "totally justified due to the fact that he is one of the initiators and financiers of the special anti-terrorist operation in the Eastern Ukraine where Russian citizens are being killed".[91][92]

By late October 2014 90% of the heads of Crimean government-owned corporation were fired as part of a supposed anti-corruption campaign, although no charges have been filed against anyone. Human rights activists in the region have described the seizures as lacking a legal basis and dismissed the "anti-corruption" rationale.[93] In June 2015 the Federal Security Service (FSB) started several anti-corruption criminal cases against high ranking Crimean officials.[94] According to Aksyonov the FSB had opened these criminal cases because it was "interested in destabilizing the situation in Crimea".[94]

On 6 May 2014 the National Bank of Ukraine ordered Ukrainian banks to cease operations in Crimea; the following weeks the Central Bank of Russia closed all Ukrainian banks in the peninsula because "they had failed to meet their obligations to creditors".[95] Eight months after the 21 March 2014 formal annexation of Crimea by Russia it became impossible for clients of Ukrainian banks to access their deposits and most of them did not pay interest (on loans).[96][clarification needed] A "Fund for the Protection of Depositors in Crimea", as part of Russia's Deposit Insurance Agency, was set up by Russia to compensate Crimeans.[96] By 6 November 2014 it paid out more than $500 million to 196,400 depositors; the fund has a limit of about $15,000 per bank account.[96] In July 2015, 25 banks were operating in Crimea while prior to the Russian annexation there were 180 banks.[97]

While many international businesses left the region, in 2015 only a few Russian companies are reported to have invested in Crimea, fearing sanctions.[85]

Under the international sanctions Crimea's once bustling IT-sector shrunk to a few IT companies.[88]

Russia invests significantly in Crimea, according to "The Federal Target Program for the Development of the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol" they plan to invest one trillion Russian rubles (15.3 billion dollars) before 2022[98][99] The Russian government claims that those investments are necessary because Ukrainian mismanagement of the Crimean territory caused losses of 2.5 trillion Russian rubles (38.3 billion dollars) to the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol[100] Meanwhile, Ukraine estimates their losses due to Russian annexation of the peninsula to 100 billion dollars.[101]

Banks

Gross regional product:[105]

- Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles, motorcycles, personal and household goods – 13%

- Transport and Telecom – 10%

- Real estate, renting and business activities – 10%

- Health care and social services – 10%

- Public administration, defense, compulsory social security – 8%

- Agriculture, hunting and forestry – 10%

- Other – 39%

Tourism

In 2014 about two million tourists holidayed in Crimea, including 300,000 Ukrainians.[106] In 2013 3.5 million Ukrainian and 1.5 million Russian tourists visited Crimea.[106] Tourism is the mainstay of the Crimean economy.[106] In August 2014 Head of the Republic Aksyonov was confident that in 2015 Crimea would welcome "at least five million visitors – I have no doubts about that".[106] Early August 2015 the press service of his government stated that in 2015 2.02 million tourists had visited Crimea (16.5% more than in 2014).[107] They stated in January 2016 (that in 2015) more than 4 million tourists had vacationed in the peninsula.[108] Over 6.4 million tourists visited Crimea in 2018, according to occupation authorities.[109][better source needed] Some tourists went home after an airbase attack in August 2022.[110] Crimean Bridge explosion also influenced the tourists.[111]

Museums and art galleries

- Aivazovsky National Art Gallery

- Alexander Grin house museum

- Feodosia Money Museum

- Lapidarium, Kerch

- Livadia Palace

- Massandra Palace

- Simferopol Art Museum

- Museum of Vera Mukhina

- Vorontsov Palace (Alupka)

- White Dacha

Industrial Park

Telecommunication

The internet connection goes via Krasnodar Krai.[114]

In Crimea Peninsula worked four mobile operators already offers voice and mobile data for 2G, 3G and 4G users.[115][unreliable source]

Transport

Aviation

Simferopol is an air transport hub of the Republic of Crimea.

Rail

Trolleybus Line

Crimean trolleybus line length of 86 kilometres (53 mi) long of service «Krymtrolleybus».

Routes: Airport Simferopol — Simferopol — Alushta — Yalta

Roads

- European route E105 – Syvash – Dzhankoy – North Crimean Canal – Simferopol – Alushta – Yalta

- Tavrida Highway A291: Kerch — Feodosia — Belogorsk — Simferopol — Bakhchisarai — Sevastopol.

- European route E97: Dzhankoy – Feodosiya – Kerch.

- Novorossiysk — Kerch highway A290: Crimean Bridge — Kerch

- Highway H19 (Ukraine) – Yalta – Sevastopol

- Highway M18 (Ukraine) – Yalta – Simferopol – Dzhankoy

- Highway H05 (Ukraine) – Simferopol – Simferopol International Airport – Krasnoperekopsk.

Water

- Kerch Strait ferry line (until 2020), Kerch–Yenikale Canal

Education

Although Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages have official status, reports say that Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar education is being squeezed.[7]

Sport

Football clubs

Human rights

United Nations monitors (who had been in Crimea from 2 April to 6 May 2014) said they were concerned about treatment of journalists, sexual, religious and ethnic minorities and AIDS patients.[116] The monitors had found that journalists and activists who had opposed the 2014 Crimean referendum had been harassed and abducted.[117] They also reported that Crimeans who had not applied for Russian citizenship faced harassment and intimidation.[116] Russia said that it did not support the deployment of human rights monitors in Crimea.[117] The (new) Crimean authorities vowed to investigate the reports of human rights violations.[117]

According to Human Rights Watch "Russia has violated multiple obligations it has as an occupying power under international humanitarian law – in particular in relation to the protection of civilians' rights."[118][56]

In its November 2014 report on Crimea, Human Rights Watch stated that "The de facto authorities in Crimea have limited free expression, restricted peaceful assembly, and intimidated and harassed those who have opposed Russia's actions in Crimea".[119] According to the report, 15 persons went missing since March 2014; according to Ukrainian authorities 21 people disappeared.[68] Head of the Republic Sergey Aksyonov pledged to find the missing persons as well as the culprits behind the kidnappings.[68] Aksyonov regularly meets with a group of parents, whose children have gone missing, and human rights activists.[68] These parents and human rights activists have complained that rotation of the team of investigators into these missing persons has harmed these investigations.[68]

Crimean Tatars

The Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People has come under the scrutiny of the Russian Federal Security Service, which reportedly took control of the building where the Mejlis meets and searched it on 16 September 2014. Crimean Tatar media said FSB officers also searched the office of the Avdet newspaper, which is based inside the Mejlis building. Several members of the Mejlis were also reportedly subjected to FSB searches at their homes. Several Crimean Tatar opposition figures were banned from entering Crimea for five years.[120] Since Russia annexed Crimea several Crimean Tatars have disappeared or have been found dead after being reported missing.[121][122][123] Crimean authorities state these deaths and disappearances are connected to "smoking an unspecified substance" and volunteers for the Syrian civil war; human rights activists claim the disappearances are part of a repression campaign against Crimean Tatars.[56][121][122]

In February 2016 human rights defender Emir-Usein Kuku from Crimea was arrested and accused of belonging to the Islamist organization Hizb ut-Tahrir, although he denies any involvement in this organization. Amnesty International has called for his immediate liberation.[124][125]

In May 2018, Server Mustafayev, the founder and coordinator of the human rights movement Crimean Solidarity, was imprisoned by Russian authorities and charged with "membership of a terrorist organisation". Amnesty International and Front Line Defenders demand his immediate release.[126][127]

International status

The status of the republic is disputed, as Russia and some other states recognised the annexation, whilst most other nations do not. Ukraine still considers both the Autonomous Republic and Sevastopol as subdivisions of Ukraine under Ukrainian territory and subject to Ukrainian law.

The United States, European Union, and Australia all claim to not issue visas to residents of Crimea with Russian passports.[86][128] However, Russian media has claimed that several member states of the Schengen Area have issued visas to Crimeans with Russian passports.[129][130]

On 21 March 2014, Armenia recognised the Crimean referendum, which led to Ukraine recalling its ambassador to that country.[131] The unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh Republic also recognised the referendum earlier that week on 17 March.[132] On 22 March 2014, President Hamid Karzai of Afghanistan told a U.S. delegation that he recognised and supported the Crimean referendum and "respects the free will of the people of Crimea and Sevastopol to decide their own future".[133] On 23 March 2014, Alexander Lukashenko, the President of Belarus stated that Crimea was de facto part of Russia, but the country did not officially recognise the Russian claim until November 2021.[134] On 27 March 2014, Nicaragua unconditionally recognised the incorporation of Crimea into Russia.[135]

In favour Against Abstentions Absent

On 27 March 2014, the UN General Assembly voted on a non-binding resolution claiming that the referendum was invalid and reaffirming Ukraine's territorial integrity, by a vote of 100 to 11, with 58 abstentions and 24 absent.[136][137] Australia, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Italy, Indonesia, Japan, Mexico, United Kingdom, United States and 89 other countries voted for; Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, North Korea, Nicaragua, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela and Zimbabwe, as well as Russia, voted against.[citation needed] Among the abstaining countries were China, India, Pakistan, South Africa and Brazil. Israel was among the countries listed as absent.[citation needed] Reuters reported unnamed UN diplomats saying the Russian delegation threatened with punitive action against certain Eastern European and Central Asian countries if they supported the resolution.[138] Subsequent United Nations General Assembly resolutions also reaffirmed non-recognition of the annexation and condemned "the temporary occupation of part of the territory of Ukraine—the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol".[139][140][141]

See also

- Annexation of the Crimean Khanate by the Russian Empire

- Autonomous Republic of Crimea

- Crimea in the Soviet Union

- Russian occupation of Crimea

- Russian annexation of Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia oblasts

Notes

- ^ Sovereignty disputed by Ukraine as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea

- ^ /kraɪˈmiːə, krɪ-/; Russian: Республика Крым, translit. Respublika Krym [rʲɪsˈpublʲɪkə krɨm]; Ukrainian: Республіка Крим, translit. Respublika Krym [resˈpublʲikɐ krɪm]; Crimean Tatar: Къырым Джумхуриети, Qırım Cumhuriyeti

References

- ^ "Crimea becomes part of vast Southern federal district of Russia". Ukraine Today. 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ "Putin reveals secrets of Russia's Crimea takeover plot". BBC. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

Crimea was formally absorbed into Russia on 18 March, to international condemnation, after unidentified gunmen took over the peninsula.

- ^ "Crimea Deputies Back Acting Leader Sergei Aksyonov to Head Republic – News". The Moscow Times. 9 October 2014.

- ^ "Autonomous Republic of Crimea". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ a b Russian Federal State Statistics Service. Всероссийская перепись населения 2020 года. Том 1 [2020 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1] (XLS) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- ^ Article 10, Section 1 of the Constitution of the Republic of Crimea (2014)

- ^ a b "Activist: Ukrainian, Crimean-Tatar Language Learning Being Squeezed In Crimea". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 January 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia turns back clocks to permanent Winter Time". AFP. 26 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ "Order of Interior Ministry of Russia №316". Interior Ministry of Russia. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Для крымских автомобилистов приготовили новые номера. Segodnya (in Russian). 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ^ Heaney, Dominic, ed. (2023). The Territories of the Russian Federation 2023 (24th ed.). Routledge. p. 43. doi:10.4324/b23329. ISBN 9781003384038. S2CID 267600423.

In March 2014 Russia annexed two territories internationally recognized as constituting parts of Ukraine—the Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol City—bringing the de facto membership of the Federation to 85 territories.

- ^ "Про внесення змін до деяких законодавчих актів України щодо вирішення окремих питань адміністративно-територіального устрою Автономної Республіки Крим". Офіційний вебпортал парламенту України (in Ukrainian). 23 August 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ Heaney, Dominic, ed. (2023). The Territories of the Russian Federation 2023 (24th ed.). Routledge. p. 130. doi:10.4324/b23329. ISBN 9781003384038. S2CID 267600423.

The territories of the Crimean peninsula, comprising Sevastopol City and the Republic of Crimea, remained internationally recognized as constituting part of Ukraine, following their annexation by Russia in March 2014.

- ^ "Vladimir Putin describes secret meeting when Russia decided to seize Crimea". The Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 9 March 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b Kofman, Michael (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF). Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. ISBN 9780833096173. OCLC 990544142.

The March 16 referendum would become the political instrument to annex the peninsula, a process that concluded on March 18

- ^ Marxen, Christian (2014). "The Crimea Crisis – An International Law Perspective" (PDF). Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (Heidelberg Journal of International Law). 74.

Organizing and holding the referendum on Crimea's accession to Russia was illegal under the Ukrainian constitution. Article 2 of the constitution establishes that "Ukraine shall be a unitary state" and that the "territory of Ukraine within its present border is indivisible and inviolable". This is confirmed in regard to Crimea by Chapter X of the constitution, which provides for the autonomous status of Crimea. Article 134 sets forth that Crimea is an "inseparable constituent part of Ukraine". The autonomous status provides Crimea with a certain set of authorities and allows, inter alia, to hold referendums. These rights are, however, limited to local matters. The constitution makes clear that alterations to the territory of Ukraine require an all-Ukrainian referendum.

- ^ "При воссоединении с Россией крымчане дискомфорта не почувствуют! – Krym Info". Krym Info. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ "Парламент Крыма принял Декларацию о независимости АРК и г. Севастополя". Государственный Совет Республики Крым. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Borgen, Christopher J. (2015). "Law, Rhetoric, Strategy: Russia and Self-Determination Before and After Crimea". International Law Studies. 91 (1) (International Law Studies ed.). ISSN 2375-2831.

The recognition of Crimea by Russia was the legal fig leaf which allowed Russia to say that it did not annex Crimea from Ukraine, rather the Republic of Crimea exercised its sovereign powers in seeking a merge with Russia

- ^ a b c "Crimea referendum: Voters 'back Russia union'". BBC News. 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Crimeans vote over 90 percent to quit Ukraine for Russia". Reuters. 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Crimea 'votes to rejoin Russia' after controversial poll". ITV. 16 March 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Crimea applies to be part of Russian Federation after vote to leave Ukraine". The Guardian. 17 March 2014.

- ^ "OSCE says Crimea referendum illegal". Refworld. 11 March 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Pifer, Steven (18 March 2019). "Five years after Crimea's illegal annexation, the issue is no closer to resolution". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Rayman, Noah (27 March 2014). "UN General Assembly: Crimea Referendum Was Illegal". Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: 'Illegal' Crimean referendum condemned". BBC News. 6 March 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ Bellinger III, John B. "Why the Crimean Referendum Is Illegitimate". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "UN report on Euronews – 15 April 2014". Euronews. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Japan does not recognise Crimea vote – govt spokesman". Reuters. 17 March 2014.

- ^ Herszenhorn, David M.; Cowell, Alan (17 March 2014). "Lawmakers in Crimea Move Swiftly to Split From Ukraine". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ "Putin Approves Draft Treaty On Crimea". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Путин одобрил проект договора о принятии в РФ Республики Крым". ТАСС. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ "Kremlin: Crimea and Sevastopol are now part of Russia, not Ukraine". CNN. 18 March 2014.

- ^ Договор между Российской Федерацией и Республикой Крым о принятии в Российскую Федерацию Республики Крым и образовании в составе Российской Федерации новых субъектов [Treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Crimea on the acceptance of the Republic of Crimea into Russian Federation and education of new subjects of the Russian Federation] (in Russian). Kremlin.ru. 18 March 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2016. (and a PDF copy of signed document)

- ^ Carol Morello and Kathy Lally (19 March 2014). "Ukraine says it is preparing to leave Crimea". The Washington Post.

- ^ Kofman, Michael (2017). Lessons from Russia's Operations in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine (PDF). Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. ISBN 9780833096173. OCLC 990544142.

By March 26, the annexation was essentially complete, and Russia began returning seized military hardware to Ukraine.

- ^ "TASS: Russia – Russian ruble goes into official circulation in Crimea as of Monday". TASS.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Crimea celebrates switch to Moscow time". BBC News. 29 March 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Sputnik (3 April 2014). "Moscow Sent Diplomatic Note to Ukraine on Terminating Black Sea Fleet Agreements". ria.ru.

- ^ "Крым и Севастополь вошли в состав Южного военного округа России". ТАСС. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Sputnik (11 April 2014). "Crimean Parliament Approves New Constitution". ria.ru.

- ^ Sudakov, Dmitry (11 April 2014). "Crimea approves new Constitution". PravdaReport.

- ^ Sputnik (11 April 2014). "Russia Amends Constitution to Include Crimea, Sevastopol". ria.ru.

- ^ Verbyany, Volodymyr (1 June 2014). "Crimea Adopts Ruble as Ukraine Continues Battling Rebels". Bloomberg.

- ^ Crimea switches to Russian telephone codes, Interfax-Ukraine (7 May 2015)

- ^ Jess McHugh (15 July 2015). "Putin Eliminates Ministry of Crimea, Region Fully Integrated into Russia, Russian Leaders Say". International Business Times. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ "Russian Security Council: Crimea is fully integrated in Russian legal, administrative systems". Kyiv Post. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "Crimea becomes part of vast Southern federal district of Russia". Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ "Крым, который лопнул. Как Путин снова обманул полуостров". 29 July 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- ^ Hurska, Alla (29 March 2021). "Demographic Transformation of Crimea: Forced Migration as Part of Russia's 'Hybrid' Strategy". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 18 (50). Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Andreyuk, Eugenia; Gliesche, Philipp (4 December 2017). "Crimea: Deportations and forced transfer of the civil population". Foreign Policy Center. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Dooley, Brian (25 March 2022). "Crimea Offers Disturbing Blueprint for Russian Takeover of Ukraine". Human Rights First. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ Lukas I. Alpert, Alexander Kolyandr. "Medvedev visits Crimea, vows development aid". Market Watch.

- ^ "The High Price of Putin's Takeover of Crimea". Bloomberg L.P. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Rights in Retreat: Abuses in Crimea". Human Rights Watch. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ "Russia restores Crimea power supply after blackout". Reuters. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Ukraine conflict: Russia completes Crimea security fence". BBC. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Crimeans have tap water only six hours a day as all Russian attempts to hydrate occupied peninsula failEuromaidan Press". News and views from Ukraine. 17 December 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "New maps appear to show Crimea is drying up". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 13 July 2018.

- ^ In southern Ukraine, Russian forces guard strategic dam

- ^ Sputnik (15 April 2014). "Ukraine's Parliament Declares Crimea, Sevastopol 'Occupied Territory'". ria.ru.

- ^ "'Crimea is Ukraine': Zelenskyy opens inaugural Crimea summit". euronews. 23 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ "The Supreme Council of ARC has been renamed as the State Council of the Republic of Crimea". Verkhovna Rada of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. 17 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ "Election Victories Strengthen Putin's Grip Around Russia and Crimea". The New York Times. 14 September 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ a b Pro-Russian Activist Falls On Hard Times In Annexed Crimea, Radio Free Europe (16 January 2016)

- ^ "Autonomous Republic of Crimea – Information card". Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Ukraine human rights 'deteriorating rapidly', Al Jazeera (3 December 2014)

Disappearing Crimea's anti-Russia activists , Al Jazeera - ^ Thomas de Waal. "The New Siege of Crimea". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Nearly 9 thousand Crimean residents received Ukrainian passports after annexation, Ukrayinska Pravda (16 October 2016)

- ^ "Infobox card – Avtonomna Respublika Krym". Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ "Putin orders military exercise as protesters clash in Crimea". reuters. 18 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- ^ "На Крымском мосту установили новый рекорд автотрафика" [A new road traffic record was set on the Crimean bridge] (in Russian). TASS. 16 August 2020.

- ^ a b "Демографический ежегодник России" [The Demographic Yearbook of Russia] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service of Russia (Rosstat). Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни при рождении" [Life expectancy at birth]. Unified Interdepartmental Information and Statistical System of Russia (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Глава 1. ОСНОВЫ КОНСТИТУЦИОННОГО СТРОЯ | Конституция Республики Крым 2014". Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "Census of the population is transferred to 2016". Dzerkalo Tzhnia (in Ukrainian). 20 September 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ^ "На крымско-татарском и украинском языках в Крыму обучаются чуть более 3% детей – Министерство образования, науки и молодежи Республики Крым – Правительство Республики Крым". rk.gov.ru. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ a b c (in Ukrainian) Crimea has no longer Ukrainian classes, Ukrayinska Pravda (14 August 2014)

- ^ (in Russian) In Crimea, Ukrainian schools left – "Minister of Education", UNIAN (10 October 2014)

- ^ Two Years After Annexation, Crimeans Wait On Russia's Unfulfilled Promises, Radio Free Europe (18 March 2016)

- ^ a b "Public Opinion Survey Residents of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea" (PDF)., The sample consisted of 1,200 permanent Crimea residents older than the age of 18 and eligible to vote and is representative of the general population by age, gender, education and religion.

- ^ "Situation of human rights in the temporarily occupied Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, Ukraine (Report of the Secretary-General)" (PDF). United Nations. 25 July 2022. § F, ¶ 34–36. Retrieved 19 June 2023.

- ^ "Situation of human rights in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, Ukraine (Report of the Secretary-General)" (PDF). United Nations. 2 August 2021. § G, ¶ 28–31.

- ^ a b "In Crimea, cash is king". gulfnews.com. 4 March 2015.

- ^ a b c "Bad_Memory". The Economist. 11 June 2015.

- ^ Dreams in Isolation: Crimea 2 Years After Annexation, The Moscow Times (18 March 2016)

- ^ a b Alexey Eremenko. "Crimea One Year After Russia Referendum Is Isolated From World". NBC News.

- ^ Sambros, Andrey (27 February 2015). "Изображая Чавеса: чем закончился год национализаций в Крыму". carnegie.ru. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Russia Delivers a New Shock to Crimean Business: Forced Nationalization, Bloomberg News (18 November 2014 )

- ^ "Kolomoyskyi's assets to be nationalized in Crimea (Sergey Aksyonov)". ceeinsight.net. 5 September 2014. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^ Ukrainian tycoon’s estate in Crimea sold for $18 mln Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Russian News Agency TASS (3 February 2016)

- ^ Crimea’s rapid Russification means pride for some but perplexity for others, Guardian Weekly (11 November 2014)

- ^ a b "The Moscow Times – News, Business, Culture & Events". Themoscowtimes.com. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- ^ Six More Ukrainian Banks Expelled from Crimea, Moscow Times (13 May 2014)

- ^ a b c Months After Russian Annexation, Crimeans Ask: 'Where Is Our Money?', Moscow Times (20 November 2014)

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Grey financial zone: why with annexed the Crimea are Russian banks Archived 21 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Welle (2 August 2015)

- ^ "ФЦП развития Крыма и Севастополя увеличили почти до триллиона". Российская газета (in Russian). 18 July 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ "Crimea – Federal Target Program | Investment portal of the Republic of Crimea". invest-in-crimea.ru. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ правды», Галина КОВАЛЕНКО | Сайт «Комсомольской (28 June 2019). "Украина за 23 года нанесла Крыму ущерб на 2,5 триллиона рублей". Crimea.kp.ru - (in Russian). Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ "Ukrainian Ministry of Justice: Ukraine lost $100 billion due to the annexation of the Crimea". Uawire. 23 February 2017.

- ^ "Company Overview of JSC GENBANK". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "Genbank | Банки.ру". www.banki.ru. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Bank CHBDR | Банки.ру". www.banki.ru. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ^ "Republic of Crimea Industries". www.investinregions.ru. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Tourism takes a nosedive in Crimea, BBC News (7 August 2014)

Russia's takeover of Crimea is killing tourism industry, Kyiv Post (14 August 2014) - ^ (in Russian) In Crimea, we saw an increase in tourist traffic as compared to the year 2014, Radio Free Europe (2 August 2015)

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Crimea – Aksenov predicts "huge flow of tourists" and operators – appreciation, Ukrayinska Pravda (19 January 2016)

- ^ "Over 6.4 mln tourists visit Crimea in 2018". TASS. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ ‘We Need to Get Out of Here’: Fear Grips Annexed Crimea After Airbase Attack

- ^ "Impact of Kerch bridge blast will be felt all the way to the Kremlin". The Guardian. 8 October 2022. Archived from the original on 18 July 2023.

- ^ "The construction of the industrial park "Feodosia" starts in June 2018 | Investment portal of the Republic of Crimea". invest-in-crimea.ru. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "RUB 800 Million to be Invested into Creation of the Logistics Hub in Crimea". eng.kr82.ru. Retrieved 30 April 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Crimeans are now using the Russian internet". 2 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "The first Russian mobile network launched in Crimea :: Ministry of Digital Development, Communications and Mass Media of the Russian Federation". Digital.gov.ru. 4 August 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b "U.N. monitors warn on human rights in east Ukraine, Crimea". Reuters. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014.

- ^ a b c Cumming-Bruce, Nick (15 April 2014). "U.N. Cites Abuses in Crimea Before Russia Annexation Vote". The New York Times.

- ^ "Crimean Tatars: Human Rights Watch Publishes Report Detailing Serious Human Rights Abuses". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ Russia Abusing Rights in Annexed Crimea, Human Rights Watch Says, Bloomberg News (17 November 2014)

Human Rights Watch releases damning report on Crimea, Kyiv Post (18 November 2014) - ^ "Russian FSB surrounds Crimean Tatar parliament-UPDATED". World Bulletin. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Missing Crimean Tatar Reportedly Found Dead". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 14 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Crimea: Enforced Disappearances". Human Rights Watch. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Кримського татарина, який зник після анексії, знайдено мертвим [The Crimean Tartar, who disappeared after the annexation, was found dead]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 28 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Jailed Crimean Tatar Human Rights Activist on Hunger Strike in Russian World Cup city". Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Crimean Tatar: Never Silent in the Face of Injustice". Amnesty International. February 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ "Russian Federation/Ukraine: Further Information: Rights Defender Facing Trumped-Up Charges: Server Mustafayev". Amnesty International. 29 November 2019.

- ^ "Arrest of Server Mustafayev". Front Line Defenders. 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Crimean residents may not be able to visit Western countries using Russian passports". uatoday.tv.

- ^ "TASS: Russia – Crimean citizens get Schengen visas in Moscow despite EU ban". TASS. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Греция выдаст крымчанам шенгенские визы". Горящие туры в Египет, туры в Турцию, Грецию. Скидки. Поиск туров – Турскидки.ру. Archived from the original on 12 May 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine Recalls Ambassador to Armenia over Crimea Recognition". Asbarez Armenian News. 21 March 2014.

- ^ "Karabakh Foreign Ministry Issues Statement on Crimea". Asbarez Armenian News. 17 March 2014.

- ^ Graham-Harrison, Emma (24 March 2014). "Afghan president Hamid Karzai backs Russia's annexation of Crimea". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Belarus leader, in U-turn, says annexed Crimea is legally Russian". Reuters. 30 November 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Nicaragua recognizes Crimea as part of Russia". Get the Latest Ukraine News Today - KyivPost. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "United Nations News Centre". UN News Service Section. 27 March 2014.

- ^ "U.N. General Assembly declares Crimea secession vote invalid". Reuters. 27 March 2014.

- ^ Charbonneau, Louis (28 March 2014). "Russia Threatened Countries Ahead of UN Vote on Ukraine, Diplomats Say". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "A/RES/71/205 – E – A/RES/71/205". undocs.org.

- ^ "General Assembly Adopts 50 Third Committee Resolutions, as Diverging Views on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity Animate Voting – Meetings Coverage and Press Releases". United Nations.

- ^ "UN officially recognized Russia as an occupying power in Crimea". Euromaidan Press. 20 December 2016.

External links

- Republic of Crimea

- Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

- Crimean Federal District

- Disputed territories in Europe

- Politics of Crimea

- Republics of Russia

- Russian occupation of Ukraine

- Countries and territories where Russian is an official language

- Separatism in Ukraine

- Southern Federal District

- States and territories established in 2014

- Russian irredentism

- Russian nationalism in Ukraine

- 2014 establishments in Russia

- Former unrecognized countries

- Crimea in the Russo-Ukrainian War

![Life expectancy in the Republic of Crimea [74][75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Life_expectancy_in_Russian_subject_-Republic_of_Crimea.png/279px-Life_expectancy_in_Russian_subject_-Republic_of_Crimea.png)