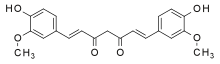

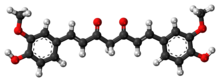

Curcumin

Enol form

| |

Keto form

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɜːrkjʊmɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name

(1E,6E)-1,7-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,6-diene-3,5-dione | |

| Other names

(1E,6E)-1,7-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione

Diferuloylmethane Curcumin I C.I. 75300 Natural Yellow 3 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.619 |

| E number | E100 (colours) |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H20O6 | |

| Molar mass | 368.385 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Bright yellow-orange powder |

| Melting point | 183 °C (361 °F; 456 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Curcumin is a bright yellow chemical produced by some plants. It is the principal curcuminoid of turmeric (Curcuma longa), a member of the ginger family, Zingiberaceae. It is sold as an herbal supplement, cosmetics ingredient, food flavoring, and food coloring.[1]

Chemically, curcumin is a diarylheptanoid, belonging to the group of curcuminoids, which are natural phenols responsible for turmeric's yellow color. It is a tautomeric compound existing in enolic form in organic solvents, and as a keto form in water.[2]

Curcumin has no confirmed medical use in spite of efforts to find one via both laboratory and clinical research. It is difficult to study because it is both unstable and not bioavailable. It is unlikely to produce useful leads for drug development.[3]

Uses

The most common applications are as an ingredient in dietary supplement, in cosmetics, and as flavoring for foods, such as turmeric-flavored beverages in the Indian Subcontinent and Southeast Asia.[1] As a food additive for gold-orange coloring in turmeric and prepared foods, its E number is E100.[4]

Annual sales of curcumin have increased since 2012.[1] The largest market is in North America, where sales exceeded US$20 million in 2014.[1]

Chemistry

Curcumin incorporates several functional groups whose structure was first identified in 1910.[5] The aromatic ring systems, which are phenols, are connected by two α,β-unsaturated carbonyl groups. The diketones form stable enols and are readily deprotonated to form enolates; the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group is a good Michael acceptor and undergoes nucleophilic addition.

Curcumin is used as a complexometric indicator for boron.[6] It reacts with boric acid to form a red-colored compound, rosocyanine.

Biosynthesis

The biosynthetic route of curcumin is uncertain. In 1973, Roughly and Whiting proposed two mechanisms for curcumin biosynthesis. The first mechanism involves a chain extension reaction by cinnamic acid and 5 malonyl-CoA molecules that eventually arylized into a curcuminoid. The second mechanism involves two cinnamate units coupled together by malonyl-CoA. Both use cinnamic acid as their starting point, which is derived from the amino acid phenylalanine.[7]

Plant biosyntheses starting with cinnamic acid is rare compared to the more common p-coumaric acid.[7] Only a few identified compounds, such as anigorufone and pinosylvin, build from cinnamic acid.[8][9]

Biosynthetic pathway of curcumin in Curcuma longa.[7]

|

Pharmacology

Curcumin, which shows positive results in most drug discovery assays, is regarded as a false lead that medicinal chemists include among "pan-assay interference compounds" attracting undue experimental attention while failing to advance as viable therapeutic or drug leads.[3][10][11]

Factors that limit the bioactivity of curcumin or its analogs include chemical instability, water insolubility, absence of potent and selective target activity, low bioavailability, limited tissue distribution, extensive metabolism.[3] Very little curcumin escapes the GI tract and most is excreted in feces unchanged.[12] If curcumin were to enter plasma in reasonable amounts there would be a high risk of toxicity since it is promiscuous, and interacts with several proteins known to increase the risk of adverse effects, including hERG, cytochrome P450s, and glutathione S-transferase.[3]

Safety

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (May 2018) |

Two preliminary clinical studies in cancer patients consuming high doses of curcumin (up to 8 grams per day for 3–4 months) showed no toxicity, though some subjects reported mild nausea or diarrhea.[13]

Research

In vitro, curcumin exhibits numerous interference properties which may lead to misinterpretation of results.[3][10][14] Although curcumin has been assessed in numerous laboratory and clinical studies, it has no medical uses established by well-designed clinical research.[15] According to a 2017 review of over 120 studies, curcumin has not been successful in any clinical trial, leading the authors to conclude that "curcumin is an unstable, reactive, non-bioavailable compound and, therefore, a highly improbable lead".[3]

The US government has supported $150 million in research into curcumin through the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, and no support has been found for curcumin as a medical treatment.[3][16]

Research fraud

Bharat Aggarwal was a cancer researcher at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who as of April 2018 had 19 papers retracted for research fraud.[17][18] Aggarwal's research had focused on potential anti-cancer properties of herbs and spices, particularly curcumin, and according to a March 2016 article in the Houston Chronicle, "attracted national media interest and laid the groundwork for ongoing clinical trials".[19][20][21] Aggarwal co-founded a company in 2004 called Curry Pharmaceuticals, based in Research Triangle Park, N.C., which was seeking to develop drugs based on synthetic analogs of curcumin.[20][22] SignPath Pharma, a company seeking to develop liposomal formulations of curcumin, licensed three patents invented by Aggarwal related to that approach from MD Anderson in 2013.[23]

Intravenous injection in alternative medicine

Despite concerns about safety or efficacy and the absence of reliable clinical research,[3][10] some alternative medicine practitioners give turmeric intravenously, supposedly as a treatment for numerous diseases.[24][25] In 2017, there were two serious cases of adverse events reported – one severe allergic reaction and one death – that were caused by injection of a curcumin emulsion product administered by a naturopath.[26][27]

History

It was first isolated in 1815 when Vogel and Pierre Joseph Pelletier reported the isolation of a "yellow coloring-matter" from the rhizomes of turmeric and named it curcumin.[28] Although curcumin has been used historically in Ayurvedic medicine,[29] its potential for medicinal properties remains unproven as a therapy when used orally.[3][10][30]

References

- ^ a b c d Majeed, Shaheen (28 December 2015). "The State of the Curcumin Market". Natural Products Insider.

- ^ Manolova, Yana; Deneva, Vera; Antonov, Liudmil; Drakalska, Elena; Momekova, Denitsa; Lambov, Nikolay (2014). "The effect of the water on the curcumin tautomerism: A quantitative approach". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 132: 815–820. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2014.05.096.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Nelson, K. M.; et al. (2017). "The Essential Medicinal Chemistry of Curcumin: Miniperspective". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 60 (5): 1620–1637. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00975. PMC 5346970. PMID 28074653.

See also: Nelson, KM; et al. (11 May 2017). "Curcumin May (Not) Defy Science". ACS medicinal chemistry letters. 8 (5): 467–470. doi:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00139. PMC 5430405. PMID 28523093. - ^ European Commission. "Food Additives". Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ Miłobȩdzka, J.; van Kostanecki, S.; Lampe, V. (1910). "Zur Kenntnis des Curcumins". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 43 (2): 2163–2170. doi:10.1002/cber.191004302168.

- ^ "EPA Method 212.3: Boron (Colorimetric, Curcumin)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c Kita, Tomoko; Imai, Shinsuke; Sawada, Hiroshi; Kumagai, Hidehiko; Seto, Haruo (2008). "The Biosynthetic Pathway of Curcuminoid in Turmeric (Curcuma longa) as Revealed by 13C-Labeled Precursors". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 72 (7): 1789–1798. doi:10.1271/bbb.80075.

- ^ Schmitt, Bettina; Hölscher, Dirk; Schneider, Bernd (2000). "Variability of phenylpropanoid precursors in the biosynthesis of phenylphenalenones in Anigozanthos preissii". Phytochemistry. 53 (3): 331–337. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00544-0. PMID 10703053.

- ^ Gehlert, R.; Schoeppner, A.; Kindl, H. (1990). "Stilbene Synthase from Seedlings of Pinus sylvestris: Purification and Induction in Response to Fungal Infection" (pdf). Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 3 (6): 444–449. doi:10.1094/MPMI-3-444.

- ^ a b c d Baker, Monya (9 January 2017). "Deceptive curcumin offers cautionary tale for chemists". Nature. 541 (7636): 144–145. doi:10.1038/541144a. PMID 28079090.

- ^ Bisson, Jonathan; McAlpine, James B.; Friesen, J. Brent; Chen, Shao-Nong; Graham, James; Pauli, Guido F. (2016-03-10). "Can Invalid Bioactives Undermine Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery?". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 59 (5): 1671–1690. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01009. ISSN 0022-2623. PMC 4791574. PMID 26505758.

- ^ Metzler, M; Pfeiffer, E; Schulz, SI; Dempe, JS (2013). "Curcumin uptake and metabolism". BioFactors (Oxford, England). 39 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1002/biof.1042. PMID 22996406.

- ^ Hsu, CH; Cheng, AL (2007). "Clinical studies with curcumin". Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 595: 471–80. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-46401-5_21. PMID 17569225.

- ^ Lowe, Derek (12 January 2017). "Curcumin Will Waste Your Time". In the Pipeline.

- ^ "Curcumin". Micronutrient Information Center; Phytochemicals. Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ Lemonick, Sam (January 19, 2017). "Everybody Needs To Stop With This Turmeric Molecule". Forbes. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Ackerman, T. (29 February 2012). "M.D. Anderson professor under fraud probe". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "Caught Our Notice: Researcher who once threatened to sue Retraction Watch now up to 19 retractions". Retraction Watch. 10 April 2018.

- ^ Ackerman, Todd (March 2, 2016). "M.D. Anderson scientist, accused of manipulating data, retires". Houston Chronicle.

- ^ a b Stix, Gary (February 2007). "Spice Healer". Scientific American. 296: 66–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0207-66. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ Ackerman, Todd (July 11, 2005). "In cancer fight, a spice brings hope to the table". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 24, 2015.

- ^ Singh, Seema (September 7, 2007). "From Exotic Spice to Modern Drug?". Cell. 130 (5): 765–768. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.024. PMID 17803897. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ Baum, Stephanie (March 26, 2013). "Biotech startup raises $1M for lung cancer treatment using component of tumeric". Med City News.

- ^ Gorski, David (23 March 2017). "An as yet unidentified "holistic" practitioner negligently kills a young woman with IV turmeric (yes, intravenous)". Respectful Insolence. Followup story:"Death by intravenous "turmeric": Why licensed naturopaths are no safer than any other naturopath". 11 April 2017.

- ^ Hermes, Britt Marie (27 March 2017). "Naturopathic Doctors Look Bad After California Woman Dies From Turmeric Injection". Forbes. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- ^ "FDA investigates two serious adverse events associated with ImprimisRx's compounded curcumin emulsion product for injection". Food and Drug Administration. 4 August 2017.

- ^ Hermes, Britt Marie (April 10, 2017). "Confirmed: Licensed Naturopathic Doctor Gave Lethal 'Turmeric' Injection". Forbes. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ Vogel, H.; Pelletier, J. (1815). "Curcumin –biological and medicinal properties". Journal de Pharmacie. I: 289.

- ^ Wilken, Reason; Veena, Mysore S.; Wang, Marilene B.; Srivatsan, Eri S. (2011). "Curcumin: A review of anti-cancer properties and therapeutic activity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma". Molecular Cancer. 10: 12. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-10-12. ISSN 1476-4598. PMC 3055228. PMID 21299897.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Turmeric". US National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.