New Orleans

New Orleans, Louisiana | |

|---|---|

| City of New Orleans | |

| From top clockwise: View of the Central Business District and Mercedes-Benz Superdome, an RTA Streetcar passing through Mid-City, a view of Royal Street in the French Quarter, a typical New Orleans mansion off St. Charles Avenue, and the St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square From top clockwise: View of the Central Business District and Mercedes-Benz Superdome, an RTA Streetcar passing through Mid-City, a view of Royal Street in the French Quarter, a typical New Orleans mansion off St. Charles Avenue, and the St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square | |

| Nickname(s): The Crescent City; The Big Easy; The City That Care Forgot; Nawlins; NOLA | |

Location of New Orleans in Orleans Parish, Louisiana. | |

| Coordinates: 29°57′N 90°4′W / 29.950°N 90.067°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Louisiana |

| Parish | Orleans |

| Founded | 1718 |

| Named for | Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mitch Landrieu (D) |

| Area | |

| 349.85 sq mi (906.10 km2) | |

| • Land | 169.42 sq mi (438.80 km2) |

| • Water | 180.43 sq mi (467.30 km2) |

| • Metro | 3,755.2 sq mi (9,726.6 km2) |

| Elevation | −6.5 to 20 ft (−2 to 6 m) |

| Population | |

| 343,829 | |

• Estimate (2016)[3] | 391,495 |

| • Density | 2,310.78/sq mi (892.20/km2) |

| • Metro | 1,262,888 (US: 46th) |

| Demonym | New Orleanian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Area code | 504 |

| FIPS code | 22-55000 |

| Website | nola.gov |

New Orleans (/njuː ˈɔːrlɪnz, -ˈɔːrli.ənz, -ɔːrˈliːnz/,[4][5] or /ˈnɔːrlɪnz/; Template:Lang-fr [la nuvɛlɔʁleɑ̃] ) is a major United States port and the largest city and metropolitan area in the state of Louisiana.

The population of the city was 343,829 as of the 2010 U.S. Census.[6][7]

The New Orleans metropolitan area (New Orleans–Metairie–Kenner Metropolitan Statistical Area) had a population of 1,167,764 in 2010 and was the 46th largest in the United States.[8] The New Orleans–Metairie–Bogalusa Combined Statistical Area, a larger trading area, had a 2010 population of 1,452,502.[9]

It is well known for its distinct French and Spanish Creole architecture, as well as its cross-cultural and multilingual heritage.[10]

New Orleans is also famous for its cuisine, music (particularly as the birthplace of jazz),[11][12] and its annual celebrations and festivals, most notably Mardi Gras, dating to French colonial times.

The city is often referred to as the "most unique"[13] in the United States.[14][15][16][17][18]

New Orleans is located in southeastern Louisiana, and developed on both sides of the Mississippi River. The heart of the city and French Quarter is on the north side of the river as it curves through this area. The city and Orleans Parish (Template:Lang-fr) are coterminous.[19] The city and parish are bounded by the parishes of St. Tammany to the north, St. Bernard to the east, Plaquemines to the south, and Jefferson to the south and west.[19][20][21] Lake Pontchartrain, part of which is included in the city limits, lies to the north and Lake Borgne lies to the east.[21]

Before Hurricane Katrina, Orleans Parish was the most populous parish in Louisiana. As of 2015,[22] it ranks third in population, trailing neighboring Jefferson Parish, and East Baton Rouge Parish.[22]

History

Names

The city is named after the Duke of Orleans, who reigned as Regent for Louis XV from 1715 to 1723, as it was established by French colonists and strongly influenced by their European culture. It also has a number of illustrative nicknames:

- Crescent City alludes to the course of the Lower Mississippi River around and through the city.[23]

- The Big Easy was possibly[clarification needed] a reference by musicians in the early 20th century to the relative ease of finding work there.[citation needed][dubious – discuss] It also may have originated in the Prohibition era, when the city was considered one big speak-easy due to the inability of the federal government to control alcohol sales in open violation of the 18th Amendment.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

- The City that Care Forgot has been used since at least 1938,[24] and refers to the outwardly easy-going, carefree nature of many of the residents.

Beginnings through the 19th century

Kingdom of France 1718–1763

Kingdom of Spain 1763–1802

French First Republic 1802–1803

United States of America 1803–1861

Republic of Louisiana 1861

Confederate States of America 1861–1862

United States of America 1862–present

La Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans) was founded May 7, 1718, by the French Mississippi Company, under the direction of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, on land inhabited by the Chitimacha. It was named for Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, who was Regent of the Kingdom of France at the time. His title came from the French city of Orléans.

The French colony was ceded to the Spanish Empire in the Treaty of Paris (1763). During the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans was an important port for smuggling aid to the rebels, transporting military equipment and supplies up the Mississippi River. Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez successfully launched a southern campaign against the British from the city in 1779.[25] New Orleans (Template:Lang-es) remained under Spanish control until 1803, when it reverted briefly to French oversight. Nearly all of the surviving 18th-century architecture of the Vieux Carré (French Quarter) dates from the Spanish period, the most notable exception being the Old Ursuline Convent.[26]

Napoleon sold Louisiana (New France) to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Thereafter, the city grew rapidly with influxes of Americans, French, Creoles, and Africans. Later immigrants were Irish, Germans, and Italians. Major commodity crops of sugar and cotton were cultivated with slave labor on large plantations outside the city.

The Haitian Revolution ended in 1804 and established the second republic in the Western Hemisphere and the first republic led by black people. It had occurred over several years in what was then the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Thousands of refugees from the violent revolution, both whites and free people of color (affranchis or gens de couleur libres), arrived in New Orleans, often bringing slaves of African descent with them. While Governor Claiborne and other officials wanted to keep out additional free black men, the French Creoles wanted to increase the French-speaking population. As more refugees were allowed into the Territory of Orleans, Haitian émigrés who had first gone to Cuba also arrived.[27] Many of the white Francophones had been deported by officials in Cuba in retaliation for Bonapartist schemes in Spain.[28]

Nearly 90 percent of these immigrants settled in New Orleans. The 1809 migration brought 2,731 whites; 3,102 free persons of African descent; and 3,226 enslaved persons of African descent, doubling the city's population. The city became 63 percent black in population, a greater proportion than Charleston, South Carolina's 53 percent.[27]

During the final campaign of the War of 1812, the British sent a force of 11,000 soldiers, marines, and sailors, in an attempt to capture New Orleans. Despite great challenges, General Andrew Jackson, with support from the U.S. Navy on the river, successfully cobbled together a motley military force of: militia from Louisiana and Mississippi, including free men of color, U.S. Army regulars, a large contingent of Tennessee state militia, Kentucky riflemen, Choctaw fighters, and local privateers (the latter led by the pirate Jean Lafitte), to decisively defeat the British troops, led by Sir Edward Pakenham, in the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815. The armies had not learned of the Treaty of Ghent which had been signed on December 24, 1814. (However, the treaty did not call for cessation of hostilities until after both governments had ratified the treaty, and the US government did not ratify it until February 16, 1815.)[29] The fighting in Louisiana had begun in December 1814 and did not end until late January, after the Americans held off the British Navy during a ten-day siege of Fort St. Philip. (The Royal Navy went on to capture Fort Bowyer near Mobile, before the commanders received news of the peace treaty.)

As a principal port, New Orleans played a major role during the antebellum era in the Atlantic slave trade. Its port also handled huge quantities of commodities for export from the interior and imported goods from other countries, which were warehoused and transferred in New Orleans to smaller vessels and distributed the length and breadth of the vast Mississippi River watershed. The river in front of the city was filled with steamboats, flatboats, and sailing ships. Despite its role in the slave trade, New Orleans at the same time had the largest and most prosperous community of free persons of color in the nation, who were often educated and middle-class property owners.[11][30]

Dwarfing in population the other cities in the antebellum South, New Orleans had the largest slave market in the domestic slave trade, which expanded after the United States' ending of the international trade in 1808. Two-thirds of the more than one million slaves brought to the Deep South arrived via the forced migration of the domestic slave trade. The money generated by the sale of slaves in the Upper South has been estimated at 15 percent of the value of the staple crop economy. The slaves represented half a billion dollars in property. An ancillary economy grew up around the trade in slaves—for transportation, housing and clothing, fees, etc., estimated at 13.5 percent of the price per person. All of this amounted to tens of billions of dollars (2005 dollars, adjusted for inflation) during the antebellum period, with New Orleans as a prime beneficiary.[31]

According to the historian Paul Lachance,

the addition of white immigrants [from Saint-Domingue] to the white creole population enabled French-speakers to remain a majority of the white population until almost 1830. If a substantial proportion of free persons of color and slaves had not also spoken French, however, the Gallic community would have become a minority of the total population as early as 1820.[32]

After the Louisiana Purchase, numerous Anglo-Americans migrated to the city. The population of the city doubled in the 1830s and by 1840, New Orleans had become the wealthiest and the third-most populous city in the nation.[33] Large numbers of German and Irish immigrants began arriving in the 1840s, working as laborers in the busy port. In this period, the state legislature passed more restrictions on manumissions of slaves, and virtually ended it in 1852.[34]

In the 1850s, white Francophones remained an intact and vibrant community; they maintained instruction in French in two of the city's four school districts (all were white).[35] In 1860, the city had 13,000 free people of color (gens de couleur libres), the class of free, mostly mixed-race people that developed during French and Spanish rule. The census recorded 81 percent as mulatto, a term used to cover all degrees of mixed race.[34] Mostly part of the Francophone group, they constituted the artisan, educated and professional class of African Americans. Most blacks were still enslaved, working at the port, in domestic service, in crafts, and mostly on the many large, surrounding sugar cane plantations.

After growing by 45 percent in the 1850s, by 1860, the city had nearly 170,000 people[36] The city was a destination for immigrants. It had grown in wealth, with a "per capita income [that] was second in the nation and the highest in the South."[36] The city had a role as the "primary commercial gateway for the nation's booming mid-section."[36] The port was the third largest in the nation in terms of tonnage of imported goods, after Boston and New York, handling 659,000 tons in 1859.[36]

As the French Creole elite feared, during the Civil War their world changed. In 1862, following the occupation by the Navy after the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, Northern forces under Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, a respected state lawyer of the Massachusetts militia, occupied the city. Later New Orleans residents nicknamed him as "Beast" Butler, because of a military order he issued. After his troops had been assaulted and harassed in the streets by Southern women, his order warned that future such occurrences would result in his men treating such "ladies" as those "plying their avocation in the streets", implying that they would treat the women like prostitutes. Accounts of this spread like wildfire across the South and the North. He also came to be called "Spoons" Butler because of the alleged looting that his troops did while occupying New Orleans.[citation needed]

Butler abolished French language instruction in city schools; statewide measures in 1864 and, after the war, 1868 further strengthened English-only policy imposed by federal representatives. With the predominance of English speakers in the city and state, that language had already become dominant in business and government.[35] By the end of the 19th century, French usage in the city had faded significantly; it was also under pressure from new immigrants: English speakers such as the Irish, and other Europeans, such as the Italians and Germans.[37] However, as late as 1902 "one-fourth of the population of the city spoke French in ordinary daily intercourse, while another two-fourths was able to understand the language perfectly,"[38] and as late as 1945, one still encountered elderly Creole women who spoke no English.[39] The last major French language newspaper in New Orleans, L'Abeille de la Nouvelle-Orléans (New Orleans Bee), ceased publication on December 27, 1923, after ninety-six years.[40] According to some sources, Le Courrier de la Nouvelle Orleans continued until 1955.[41]

As the city was captured and occupied early in the war, it was spared the destruction through warfare suffered by many other cities of the American South. The Union Army eventually extended its control north along the Mississippi River and along the coastal areas of the State. As a result, most of the southern portion of Louisiana was originally exempted from the liberating provisions of the 1863 "Emancipation Proclamation" issued by President Abraham Lincoln. Large numbers of rural ex-slaves and some free people of color from the city volunteered for the first regiments of Black troops in the War. Led by Brig. Gen. Daniel Ullman (1810–1892), of the 78th Regiment of New York State Volunteers Militia, they were known as the "Corps d'Afrique." While that name had been used by a militia before the war, that group was composed of free people of color. The new group was made up mostly of former slaves. They were supplemented in the last two years of the War by newly organized United States Colored Troops, who played an increasingly important part in the war.[42]

Violence throughout the South, especially the Memphis Riots of 1866 followed by the New Orleans Riot in July of that year, resulted in Congress passing the Reconstruction Act and the Fourteenth Amendment, to extend the protections of full citizenship to freedmen and free people of color. Louisiana and Texas were put under the authority of the "Fifth Military District" of the United States during Reconstruction. Louisiana was eventually readmitted to the Union in 1868; its Constitution of 1868 granted universal manhood suffrage and established universal public education. Both blacks and whites were elected to local and state offices. In 1872, lieutenant governor P.B.S. Pinchback, who was of mixed race, succeeded Henry Clay Warmouth for a brief period as Republican governor of Louisiana, becoming the first governor of African descent of an American state. (The next African American to serve as governor of an American state was Douglas Wilder, elected in Virginia in 1989.) New Orleans even operated a racially-integrated public school system during this period.

Wartime damage to levees and cities along the Mississippi River adversely affected southern crops and trade for the port city for some time. The federal government contributed to restoring infrastructure, but it took time. The nationwide financial recession and Panic of 1873 also adversely affected businesses and slowed economic recovery.

From 1868, elections in Louisiana were marked by violence, as white insurgents tried to suppress black voting and disrupt Republican gatherings. Violence continued around elections. The disputed 1872 gubernatorial election resulted in conflicts that ran for years. The "White League", an insurgent paramilitary group that supported the Democratic Party, was organized in 1874 and operated in the open, violently suppressing the black vote and running off Republican officeholders. In 1874, in the Battle of Liberty Place, 5,000 members of the White League fought with city police to take over the state offices for the Democratic candidate for governor, holding them for three days. By 1876, such tactics resulted in the white Democrats, the so-called Redeemers, regaining political control of the state legislature. The federal government gave up and withdrew its troops in 1877, ending Reconstruction.

White Democrats passed Jim Crow laws, establishing racial segregation in public facilities. In 1889, the legislature passed a constitutional amendment incorporating a "grandfather clause" that effectively disfranchised freedmen as well as the propertied people of color free before the war. Unable to vote, African Americans could not serve on juries or in local office, and were closed out of formal politics for several generations in the state. It was ruled by a white Democratic Party. Public schools were racially segregated and remained so until 1960.

New Orleans' large community of well-educated, often French-speaking free persons of color (gens de couleur libres), who had been free prior to the Civil War, sought to fight back against Jim Crow. They organized the Comité des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) to work for civil rights. As part of their legal campaign, they recruited one of their own, Homer Plessy, to test whether Louisiana's newly enacted Separate Car Act was constitutional. Plessy boarded a commuter train departing New Orleans for Covington, Louisiana, sat in the car reserved for whites only, and was arrested. The case resulting from this incident, Plessy v. Ferguson, was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896. The court ruled that "separate but equal" accommodations were constitutional, effectively upholding Jim Crow measures. In practice, African-American public schools and facilities were underfunded in Louisiana and across the South. The Supreme Court ruling contributed to this period as the nadir of race relations in the United States. The rate of lynchings of black men was high across the South, as other states also disfranchised blacks and sought to impose Jim Crow to establish white supremacy. Anti-Italian sentiment in 1891 contributed to the lynchings of 11 Italians, some of whom had been acquitted of the murder of the police chief. Some were shot and killed in the jail where they were being held. It was the largest mass lynching in U.S. history.[43][44] In July 1900 the city was swept by white mobs rioting after Robert Charles, a young African American, had killed a policeman and temporarily escaped. They killed him and an estimated 20 other blacks; seven whites died in the conflict, which lasted a few days until a state militia suppressed it.

Throughout New Orleans' history, until the early 20th century when medical and scientific advances ameliorated the situation, the city suffered repeated epidemics of yellow fever and other tropical and infectious diseases.

20th century

New Orleans' zenith as an economic and population center, in relation to other American cities, occurred in the decades prior to 1860. At this time New Orleans was the nation's fifth-largest city and was significantly larger than all other American South population centers.[45] New Orleans continued to increase in population from the mid-19th century onward, but rapid economic growth shifted to other areas of the country, meaning that New Orleans' relative importance steadily declined. First to emerge in importance were the new industrial and railroad hubs of the Midwest, then the rapidly growing metropolises of the Pacific Coast in the decades before and after the turn of the 20th century. Construction of railways and highways decreased river traffic, diverting goods to other transportation corridors and markets.[45] Thousands of the most ambitious blacks and people of color left New Orleans and the state in the Great Migration around World War II and after, many for West Coast destinations. In the post-war period, other Sun Belt cities in the South and West surpassed New Orleans in population.

From the late 1800s, most U.S. censuses recorded New Orleans' slipping rank among American cities. Reminded every ten years of its declining relative importance, New Orleans would periodically mount attempts to regain its economic vigor and pre-eminence, with varying degrees of success.

By the mid-20th century, New Orleanians recognized that their city was being surpassed as the leading urban area in the South. By 1950, Houston, Dallas, and Atlanta exceeded New Orleans in size, and in 1960 Miami eclipsed New Orleans, even as the latter's population reached what would be its historic peak that year.[45] As with other older American cities in the postwar period, highway construction and suburban development drew residents from the center city to newer housing outside. The 1970 census recorded the first absolute decline in the city's population since it joined the United States. The New Orleans metropolitan area continued expanding in population, however, just not as rapidly as other major cities in the Sun Belt. While the port remained one of the largest in the nation, automation and containerization resulted in significant job losses. The city's relative fall in stature meant that its former role as banker to the South was inexorably supplanted by competing companies in larger peer cities. New Orleans' economy had always been based more on trade and financial services than on manufacturing, but the city's relatively small manufacturing sector also shrank in the post–World War II period. Despite some economic development successes under the administrations of DeLesseps "Chep" Morrison (1946–1961) and Victor "Vic" Schiro (1961–1970), metropolitan New Orleans' growth rate consistently lagged behind more vigorous cities.

Civil Rights Movement

During the later years of Morrison's administration, and for the entirety of Schiro's, the city was a center of the Civil Rights Movement. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference was founded in the city, and lunch counter sit-ins were held in Canal Street department stores. A prominent and violent series of confrontations occurred in 1960 when the city attempted school desegregation, following the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). When six-year-old Ruby Bridges integrated William Frantz Elementary School in the city's Ninth Ward, she was the first child of color to attend a previously all-white school in the South.

The Civil Rights Movement's success in gaining federal passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 provided enforcement of constitutional rights, including renewed voting for blacks. Together, these resulted in the most far-reaching changes in New Orleans' 20th century history.[46] Though legal and civil equality were re-established by the end of the 1960s, a large gap in income levels and educational attainment persisted between the city's White and African-American communities.[47] As the middle class and wealthier members of both races left the center city, its population's income level dropped, and it became proportionately more African American. From 1980, the African-American majority has elected primarily officials from its own community. They have struggled to narrow the gap by creating conditions conducive to the economic uplift of the African-American community.

New Orleans became increasingly dependent on tourism as an economic mainstay during the administrations of Sidney Barthelemy (1986–1994) and Marc Morial (1994–2002). Relatively low levels of educational attainment, high rates of household poverty, and rising crime threatened the prosperity of the city in the later decades of the century.[47] The negative effects of these socioeconomic conditions contrasted with the changes to the economy of the United States, which were based on a post-industrial, knowledge-based paradigm in which mental skills and education were far more important to advancement than manual skills.

Drainage and flood control

In the 20th century, New Orleans' government and business leaders believed they needed to drain and develop outlying areas to provide for the city's expansion. The most ambitious development during this period was a drainage plan devised by engineer and inventor A. Baldwin Wood, designed to break the surrounding swamp's stranglehold on the city's geographic expansion. Until then, urban development in New Orleans was largely limited to higher ground along the natural river levees and bayous.

Wood's pump system allowed the city to drain huge tracts of swamp and marshland and expand into low-lying areas. Over the 20th century, rapid subsidence, both natural and human-induced, resulted in these newly populated areas declining to several feet below sea level.[48][49]

New Orleans was vulnerable to flooding even before the city's footprint departed from the natural high ground near the Mississippi River. In the late 20th century, however, scientists and New Orleans residents gradually became aware of the city's increased vulnerability. In 1965, flooding from Hurricane Betsy killed dozens of residents, although the majority of the city remained dry. The rain-induced flood of May 8, 1995, demonstrated the weakness of the pumping system. After that event, measures were undertaken to dramatically upgrade pumping capacity. By the 1980s and 1990s, scientists observed that extensive, rapid, and ongoing erosion of the marshlands and swamp surrounding New Orleans, especially that related to the Mississippi River – Gulf Outlet Canal, had the unintended result of leaving the city more vulnerable to hurricane-induced catastrophic storm surges than earlier in its history.

21st century

Hurricane Katrina

New Orleans was catastrophically affected by what the University of California Berkeley's Dr. Raymond B. Seed called "the worst engineering disaster in the world since Chernobyl", when the Federal levee system failed during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.[50] By the time the hurricane approached the city at the end of August 2005, most residents had evacuated. As the hurricane passed through the Gulf Coast region, the city's federal flood protection system failed, resulting in the worst civil engineering disaster in American history.[51] Floodwalls and levees constructed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers failed below design specifications and 80% of the city flooded. Tens of thousands of residents who had remained in the city were rescued or otherwise made their way to shelters of last resort at the Louisiana Superdome or the New Orleans Morial Convention Center. More than 1,500 people were recorded as having died in Louisiana, most in New Orleans, and others are still unaccounted for.[52][53] Before Hurricane Katrina, the city called for the first mandatory evacuation in its history, to be followed by another mandatory evacuation three years later with Hurricane Gustav.

Hurricane Rita

The city was declared off-limits to residents while efforts to clean up after Hurricane Katrina began. The approach of Hurricane Rita in September 2005 caused repopulation efforts to be postponed,[54] and the Lower Ninth Ward was reflooded by Rita's storm surge.[53]

Post-disaster recovery

Because of the scale of damage, many people settled permanently outside the city in other areas where they had evacuated, as in Houston. Federal, state, and local efforts have been directed at recovery and rebuilding in severely damaged neighborhoods. The Census Bureau in July 2006 estimated the population of New Orleans to be 223,000; a subsequent study estimated that 32,000 additional residents had moved to the city as of March 2007, bringing the estimated population to 255,000, approximately 56% of the pre-Katrina population level. Another estimate, based on data on utility usage from July 2007, estimated the population to be approximately 274,000 or 60% of the pre-Katrina population. These estimates are somewhat smaller than a third estimate, based on mail delivery records, from the Greater New Orleans Community Data Center in June 2007, which indicated that the city had regained approximately two-thirds of its pre-Katrina population.[55] In 2008, the Census Bureau revised its population estimate for the city upward, to 336,644.[56] Most recently, 2010 estimates show that neighborhoods that did not flood are near 100% of their pre-Katrina populations, and in some cases, exceed 100% of their pre-Katrina populations.[57]

Several major tourist events and other forms of revenue for the city have returned. Large conventions are being held again, such as those held by the American Library Association and American College of Cardiology.[58][59] College football events such as the Bayou Classic, New Orleans Bowl, and Sugar Bowl returned for the 2006–2007 season. The New Orleans Saints returned that season as well, following speculation of a move. The New Orleans Hornets (now named the Pelicans) returned to the city fully for the 2007–2008 season, having partially spent the 2006–2007 season in Oklahoma City. New Orleans successfully hosted the 2008 NBA All-Star Game and the 2008 BCS National Championship Game. The city hosted the first and second rounds of the 2007 NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament. New Orleans and Tulane University hosted the Final Four Championship in 2012. Additionally, the city hosted the Super Bowl XLVII on February 3, 2013 at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome.

Major annual events such as Mardi Gras and the Jazz & Heritage Festival were never displaced or canceled. Also, an entirely new annual festival, "The Running of the Bulls New Orleans", was created in 2007.[60]

On February 7, 2017, a large EF3 wedge tornado hit parts of the eastern side of the city, causing severe damages to homes and other buildings, as well as destroying a mobile home park. At least 25 people were left injured by the event.[61]

Geography

New Orleans is located at 29°57′53″N 90°4′14″W / 29.96472°N 90.07056°W (29.964722, −90.070556)[62] on the banks of the Mississippi River, approximately 105 miles (169 km) upriver from the Gulf of Mexico. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 350 square miles (910 km2), of which 169 square miles (440 km2) is land and 181 square miles (470 km2) (52%) is water.[63] Orleans Parish is the smallest parish by land area in Louisiana.

The city is located in the Mississippi River Delta on the east and west banks of the Mississippi River and south of Lake Pontchartrain. The area along the river is characterized by ridges and hollows.

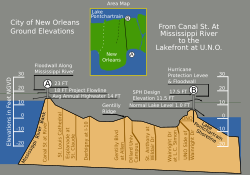

Elevation

New Orleans was originally settled on the natural levees or high ground, along the Mississippi River. After the Flood Control Act of 1965, the US Army Corps of Engineers built floodwalls and man-made levees around a much larger geographic footprint that included previous marshland and swamp. Over time, pumping of nearby marshland allowed for development into lower elevation areas. Today, a large portion of New Orleans is at or below local mean sea level and evidence suggests that portions of the city may be dropping in elevation due to subsidence.

A 2007 study by Tulane and Xavier University suggested that "51%... of the contiguous urbanized portions of Orleans, Jefferson, and St. Bernard parishes lie at or above sea level," with the more densely populated areas generally on higher ground. The average elevation of the city is currently between 1 foot (0.30 m) and

2 feet (0.61 m) below sea level, with some portions of the city as high as 20 feet (6 m) at the base of the river levee in Uptown and others as low as 7 feet (2 m) below sea level in the farthest reaches of Eastern New Orleans.[64][65] A study published by the ASCE Journal of Hydrologic Engineering in 2016, however, stated:

...most of New Orleans proper - about 65% - is at or below mean sea level, as defined by the average elevation of Lake Pontchartrain[66]

The magnitude of subsidence potentially caused by the draining of natural marsh in the New Orleans area and southeast Louisiana is a topic of debate. A study published in Geology in 2006 by an associate professor at Tulane University claims:

While erosion and wetland loss are huge problems along Louisiana's coast, the basement 30 to 50 feet (15 m) beneath much of the Mississippi Delta has been highly stable for the past 8,000 years with negligible subsidence rates.[67]

The study noted, however, that the results did not necessarily apply to the Mississipi River Delta, nor the New Orleans Metropolitan area proper. On the other hand, a report by the American Society of Civil Engineers claims that "New Orleans is subsiding (sinking)":[68]

Large portions of Orleans, St. Bernard, and Jefferson parishes are currently below sea level—and continue to sink. New Orleans is built on thousands of feet of soft sand, silt, and clay. Subsidence, or settling of the ground surface, occurs naturally due to the consolidation and oxidation of organic soils (called "marsh" in New Orleans) and local groundwater pumping. In the past, flooding and deposition of sediments from the Mississippi River counterbalanced the natural subsidence, leaving southeast Louisiana at or above sea level. However, due to major flood control structures being built upstream on the Mississippi River and levees being built around New Orleans, fresh layers of sediment are not replenishing the ground lost by subsidence.[68]

In May 2016, NASA published a study[69] which suggested that most areas of New Orleans were, in fact, experiencing subsidence at a "highly variable rate" which was "generally consistent with, but somewhat higher than, previous studies."

Cityscape

The Central Business District of New Orleans is located immediately north and west of the Mississippi River, and was historically called the "American Quarter" or "American Sector." It was developed after the heart of French and Spanish settlement. It includes Lafayette Square. Most streets in this area fan out from a central point in the city. Major streets of the area include Canal Street, Poydras Street, Tulane Avenue and Loyola Avenue. Canal Street functions as the street which divides the traditional "downtown" area from the "uptown" area.

Every street crossing Canal Street between the Mississippi River and Rampart Street, which is the northern edge of the French Quarter, has a different name for the "uptown" and "downtown" portions. For example, St. Charles Avenue, known for its street car line, is called Royal Street below Canal Street, though where it traverses the Central Business District between Canal and Lee Circle, it is properly called St. Charles Street.[70] Elsewhere in the city, Canal Street serves as the dividing point between the "South" and "North" portions of various streets. In the local parlance downtown means "downriver from Canal Street", while uptown means "upriver from Canal Street". Downtown neighborhoods include the French Quarter, Tremé, the 7th Ward, Faubourg Marigny, Bywater (the Upper Ninth Ward), and the Lower Ninth Ward. Uptown neighborhoods include the Warehouse District, the Lower Garden District, the Garden District, the Irish Channel, the University District, Carrollton, Gert Town, Fontainebleau, and Broadmoor. However, the Warehouse and the Central Business District, despite being above Canal Street, are frequently called "Downtown" as a specific region, as in the Downtown Development District.

Other major districts within the city include Bayou St. John, Mid-City, Gentilly, Lakeview, Lakefront, New Orleans East, and Algiers.

Historic and residential architecture

New Orleans is world-famous for its abundance of unique architectural styles which reflect the city's historical roots and multicultural heritage. Though New Orleans possesses numerous structures of national architectural significance, it is equally, if not more, revered for its enormous, largely intact (even post-Katrina) historic built environment. Twenty National Register Historic Districts have been established, and fourteen local historic districts aid in the preservation of this tout ensemble. Thirteen of the local historic districts are administered by the New Orleans Historic District Landmarks Commission (HDLC), while one—the French Quarter—is administered by the Vieux Carre Commission (VCC). Additionally, both the National Park Service, via the National Register of Historic Places, and the HDLC have landmarked individual buildings, many of which lie outside the boundaries of existing historic districts.[71]

Many styles of housing exist in the city, including the shotgun house and the bungalow style. Creole townhouses, notable for their large courtyards and intricate iron balconies, line the streets of the French Quarter. Throughout the city, there are many other historic housing styles: Creole cottages, American townhouses, double-gallery houses, and Raised Center-Hall Cottages. St. Charles Avenue is famed for its large antebellum homes. Its mansions are in various styles, such as Greek Revival, American Colonial and the Victorian styles of Queen Anne and Italianate architecture. New Orleans is also noted for its large, European-style Catholic cemeteries, which can be found throughout the city.

Tallest buildings

For much of its history, New Orleans' skyline consisted of only low- and mid- rise structures. The soft soils of New Orleans are susceptible to subsidence, and there was doubt about the feasibility of constructing large high rises in such an environment. Developments in engineering throughout the twentieth century eventually made it possible to build sturdy foundations to support high rise structures in the city, and in the 1960s, the World Trade Center New Orleans and Plaza Tower were built, demonstrating the viability of tall skyscrapers in New Orleans. One Shell Square took its place as the city's tallest building in 1972. The oil boom of the 1970s and early 1980s redefined New Orleans' skyline with the development of the Poydras Street corridor. Today, most of New Orleans' tallest buildings are clustered along Canal Street and Poydras Street in the Central Business District.

| Name | Stories | Height |

|---|---|---|

| One Shell Square | 51 | 697 ft (212 m) |

| Place St. Charles | 53 | 645 ft (197 m) |

| Plaza Tower | 45 | 531 ft (162 m) |

| Energy Centre | 39 | 530 ft (160 m) |

| First Bank and Trust Tower | 36 | 481 ft (147 m) |

Climate

| Climate data for New Orleans Int'l (1981–2010 normals,[a] extremes 1946–present)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

101 (38) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

94 (34) |

87 (31) |

84 (29) |

102 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 77.2 (25.1) |

78.9 (26.1) |

82.3 (27.9) |

86.7 (30.4) |

91.5 (33.1) |

94.5 (34.7) |

96.0 (35.6) |

96.4 (35.8) |

93.5 (34.2) |

89.0 (31.7) |

83.7 (28.7) |

79.7 (26.5) |

97.3 (36.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 62.1 (16.7) |

65.4 (18.6) |

71.8 (22.1) |

78.2 (25.7) |

85.2 (29.6) |

89.5 (31.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

91.2 (32.9) |

87.5 (30.8) |

80.0 (26.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

64.4 (18.0) |

78.2 (25.7) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 53.4 (11.9) |

56.7 (13.7) |

62.7 (17.1) |

69.1 (20.6) |

76.7 (24.8) |

81.5 (27.5) |

83.3 (28.5) |

83.3 (28.5) |

79.8 (26.6) |

71.3 (21.8) |

62.7 (17.1) |

55.7 (13.2) |

69.7 (20.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 44.7 (7.1) |

48.0 (8.9) |

53.5 (11.9) |

60.0 (15.6) |

68.1 (20.1) |

73.5 (23.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

75.3 (24.1) |

72.0 (22.2) |

62.6 (17.0) |

53.5 (11.9) |

46.9 (8.3) |

61.2 (16.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 27.6 (−2.4) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

36.8 (2.7) |

44.6 (7.0) |

56.0 (13.3) |

65.7 (18.7) |

69.9 (21.1) |

70.0 (21.1) |

60.6 (15.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

37.6 (3.1) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 14 (−10) |

16 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

50 (10) |

60 (16) |

60 (16) |

42 (6) |

35 (2) |

24 (−4) |

11 (−12) |

11 (−12) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.15 (131) |

5.30 (135) |

4.55 (116) |

4.61 (117) |

4.63 (118) |

8.06 (205) |

5.93 (151) |

5.98 (152) |

4.97 (126) |

3.54 (90) |

4.49 (114) |

5.24 (133) |

62.45 (1,586) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.3 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 6.9 | 7.7 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 13.1 | 9.4 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 9.2 | 114.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.6 | 73.0 | 72.9 | 73.4 | 74.4 | 76.4 | 79.2 | 79.4 | 77.8 | 74.9 | 77.2 | 76.9 | 75.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 153.0 | 161.5 | 219.4 | 251.9 | 278.9 | 274.3 | 257.1 | 251.9 | 228.7 | 242.6 | 171.8 | 157.8 | 2,648.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 47 | 52 | 59 | 65 | 66 | 65 | 60 | 62 | 62 | 68 | 54 | 50 | 60 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[c][73][74][75] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Audubon Park, New Orleans (extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

93 (34) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

102 (39) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

97 (36) |

92 (33) |

85 (29) |

104 (40) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 13 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

26 (−3) |

32 (0) |

46 (8) |

54 (12) |

61 (16) |

60 (16) |

49 (9) |

35 (2) |

26 (−3) |

12 (−11) |

6 (−14) |

| Source: NOAA[73] | |||||||||||||

The climate of New Orleans is humid subtropical (Köppen climate classification Cfa), with short, generally mild winters and hot, humid summers; most suburbs and parts of Wards 9 and 15 fall in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 9a, while the city's other 15 wards are rated 9b in whole.[76] The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 53.4 °F (11.9 °C) in January to 83.3 °F (28.5 °C) in July and August. Officially, as measured at New Orleans International Airport, temperature records range from 11 to 102 °F (−12 to 39 °C) on December 23, 1989 and August 22, 1980, respectively; Audubon Park has recorded temperatures ranging from 6 °F (−14 °C) on February 13, 1899 up to 104 °F (40 °C) on June 24, 2009.[73] Dewpoints in the summer months (June–August) are relatively high, ranging from 71.1 to 73.4 °F (21.7 to 23.0 °C).[75]

The average precipitation is 62.5 inches (1,590 mm) annually; the summer months are the wettest, while October is the driest month.[73] Precipitation in winter usually accompanies the passing of a cold front. On average, there are 77 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 8.1 days per winter where the high does not exceed 50 °F (10 °C), and 8.0 nights with freezing lows annually. It is rare for the temperature to reach 20 or 100 °F (−7 or 38 °C), with the last occurrence of each being February 5, 1996 and June 26, 2016, respectively.[73]

New Orleans experiences snowfall only on rare occasions. A small amount of snow fell during the 2004 Christmas Eve Snowstorm and again on Christmas (December 25) when a combination of rain, sleet, and snow fell on the city, leaving some bridges icy. The New Year's Eve 1963 snowstorm affected New Orleans and brought 4.5 inches (11 cm). Snow fell again on December 22, 1989, when most of the city received 1–2 inches (2.5–5.1 cm).

The last significant snowfall in New Orleans was on the morning of December 11, 2008.

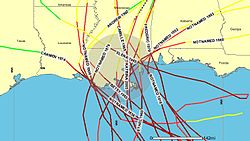

Threat from tropical cyclones

Hurricanes pose a severe threat to the area, and the city is particularly at risk because of its low elevation; because it is surrounded by water from the north, east, and south; and because of Louisiana's sinking coast.[77] According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency, New Orleans is the nation's most vulnerable city to hurricanes.[78] Indeed, portions of Greater New Orleans have been flooded by: the Grand Isle Hurricane of 1909,[79] the New Orleans Hurricane of 1915,[79] 1947 Fort Lauderdale Hurricane,[79] Hurricane Flossy[80] in 1956, Hurricane Betsy in 1965, Hurricane Georges in 1998, Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, and Hurricane Gustav in 2008, with the flooding in Betsy being significant and in a few neighborhoods severe, and that in Katrina being disastrous in the majority of the city.[81][82][83]

In 2005, storm surge from Hurricane Katrina caused catastrophic failure of the federally designed and built levees, flooding 80% of the city.[84][85] A report by the American Society of Civil Engineers says that "had the levees and floodwalls not failed and had the pump stations operated, nearly two-thirds of the deaths would not have occurred".[68]

New Orleans has always had to consider the risk of hurricanes, but the risks are dramatically greater today due to coastal erosion from human interference.[86] Since the beginning of the 20th century, it has been estimated that Louisiana has lost 2,000 square miles (5,000 km2) of coast (including many of its barrier islands), which once protected New Orleans against storm surge. Following Hurricane Katrina, the Army Corps of Engineers has instituted massive levee repair and hurricane protection measures to protect the city.

In 2006, Louisiana voters overwhelmingly adopted an amendment to the state's constitution to dedicate all revenues from off-shore drilling to restore Louisiana's eroding coast line.[87] Congress has allocated $7 billion to bolster New Orleans' flood protection.[88]

According to a study by the National Academy of Engineering and the National Research Council, levees and floodwalls surrounding New Orleans—no matter how large or sturdy—cannot provide absolute protection against overtopping or failure in extreme events. Levees and floodwalls should be viewed as a way to reduce risks from hurricanes and storm surges, not as measures that completely eliminate risk. For structures in hazardous areas and residents who do not relocate, the committee recommended major floodproofing measures—such as elevating the first floor of buildings to at least the 100-year flood level.[89]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1769 | 3,190 | — |

| 1785 | 4,980 | +56.1% |

| 1788 | 5,331 | +7.0% |

| 1797 | 8,056 | +51.1% |

| 1810 | 17,242 | +114.0% |

| 1820 | 27,176 | +57.6% |

| 1830 | 46,082 | +69.6% |

| 1840 | 102,193 | +121.8% |

| 1850 | 116,375 | +13.9% |

| 1860 | 168,675 | +44.9% |

| 1870 | 191,418 | +13.5% |

| 1880 | 216,090 | +12.9% |

| 1890 | 242,039 | +12.0% |

| 1900 | 287,104 | +18.6% |

| 1910 | 339,075 | +18.1% |

| 1920 | 387,219 | +14.2% |

| 1930 | 458,762 | +18.5% |

| 1940 | 494,537 | +7.8% |

| 1950 | 570,445 | +15.3% |

| 1960 | 627,525 | +10.0% |

| 1970 | 593,471 | −5.4% |

| 1980 | 557,515 | −6.1% |

| 1990 | 496,938 | −10.9% |

| 2000 | 484,674 | −2.5% |

| 2010 | 343,829 | −29.1% |

| 2016 | 391,495 | +13.9% |

| Population given for the City of New Orleans, not for Orleans Parish, before New Orleans absorbed suburbs and rural areas of Orleans Parish in 1874. Population for Orleans Parish was 41,351 in 1820; 49,826 in 1830; 102,193 in 1840; 119,460 in 1850; 174,491 in 1860; and 191,418 in 1870. Historical Population Figures[56][90][91] Source: | ||

| Racial composition | 2010[97] | 1990[98] | 1970[98] | 1940[98] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 33.0% | 34.9% | 54.5% | 69.7% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 30.5% | 33.1% | 50.6%[99] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 60.2% | 61.9% | 45.0% | 30.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 5.2% | 3.5% | 4.4%[99] | n/a |

| Asian | 2.9% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

According to the 2010 Census, 343,829 people and 189,896 households were in New Orleans. The racial and ethnic makeup of the city was 60.2% African American, 33.0% White, 2.9% Asian (1.7% Vietnamese, 0.3% Indian, 0.3% Chinese, 0.1% Filipino, 0.1% Korean), 0.0% Pacific Islander, and 1.7% were people of two or more races. People of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 5.3% of the population; 1.3% of New Orleans is Mexican, 1.3% Honduran, 0.4% Cuban, 0.3% Puerto Rican, and 0.3% Nicaraguan.[100]

The last population estimate before Hurricane Katrina was 454,865, as of July 1, 2005.[101] A population analysis released in August 2007 estimated the population to be 273,000, 60% of the pre-Katrina population and an increase of about 50,000 since July 2006.[102] A September 2007 report by The Greater New Orleans Community Data Center, which tracks population based on U.S. Postal Service figures, found that in August 2007, just over 137,000 households received mail. That compares with about 198,000 households in July 2005, representing about 70% of pre-Katrina population.[103] More recently, the Census Bureau revised upward its 2008 population estimate for the city, to 336,644 inhabitants.[56] In 2010, estimates showed that neighborhoods that did not flood were near 100% of their pre-Katrina populations, and in some cases, exceeded 100% of their pre-Katrina populations.[57]

A 2006 study by researchers at Tulane University and the University of California, Berkeley determined that there are as many as 10,000 to 14,000 undocumented immigrants, many from Mexico, currently residing in New Orleans.[104] Janet Murguía, president and chief executive officer of the National Council of La Raza, stated that there could be up to 120,000 Hispanic workers in New Orleans. In June 2007, one study stated that the Hispanic population had risen from 15,000, pre-Katrina, to over 50,000.[105]

The Times-Picayune reported in January 2009 that the metropolitan area had a recent influx of 5,300 households in the later half of 2008, bringing the population to around 469,605 households, or 88.1% of its pre-Katrina levels. While the area's population has been on an upward trajectory since the storm, much of that growth was attributed to residents returning after Katrina. Many observers predicted that growth would taper off, but the data center's analysis suggests that New Orleans and the surrounding parishes are benefiting from an economic migration resulting from the global financial crisis of 2008–2009.[106][107]

As of 2010[update], 90.31% of New Orleans residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as a primary language, while 4.84% spoke Spanish, 1.87% Vietnamese, and 1.05% spoke French. In total, 9.69% of New Orleans's population age 5 and older spoke a mother language other than English.[108]

Religion

New Orleans' colonial history of French and Spanish settlement has resulted in a strong Roman Catholic tradition. Catholic missions administered to slaves and free people of color, establishing schools for them. In addition, many late 19th and early 20th century European immigrants, such as the Irish, some Germans, and Italians, were Catholic. In New Orleans and the surrounding Louisiana Gulf Coast area, the predominant religion is Catholicism. Within the Archdiocese of New Orleans (which includes not only the city but the surrounding Parishes as well), 35.9% percent of the population is Roman Catholic.[109] The influence of Catholicism is reflected in the city's French and Spanish cultural traditions, including its many parochial schools, street names, architecture, and festivals, including Mardi Gras.

New Orleans notably has a distinctive variety of Louisiana Voodoo, due in part to syncretism with African and Afro-Caribbean Roman Catholic beliefs. The fame of the voodoo practitioner Marie Laveau contributed to this, as did New Orleans' distinctly Caribbean cultural influences.[110][111][112] Although the tourism industry has strongly associated Voodoo with the city, only a small number of people are serious adherents to the religion.

Jewish settlers, primarily Sephardim, settled in New Orleans from the early nineteenth century. Some migrated from the communities established in the colonial years in Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. The merchant Abraham Cohen Labatt helped found the first Jewish congregation in New Orleans and Louisiana in the 1830s, which became known as the Portuguese Jewish Nefutzot Yehudah congregation (he and some other members were Sephardic Jews, whose ancestors had lived in Portugal and Spain). Ashkenazi Jews from eastern Europe came as immigrants in the late 19th and 20th centuries. By the 21st century, there were 10,000 Jews in New Orleans. This number dropped to 7,000 after the disruption of Hurricane Katrina.

In the wake of Katrina, all New Orleans synagogues lost members, but most re-opened in their original locations. The exception was Congregation Beth Israel, the oldest and most prominent Orthodox synagogue in the New Orleans region. Beth Israel's building in Lakeview was destroyed by flooding. After seven years of holding services in temporary quarters, the congregation consecrated a synagogue in August 2012 on land purchased from its new neighbor, the Reform Congregation Gates of Prayer in Metairie.[113]

Ethnic groups

As of 2011[update] there had been increases in the Hispanic population in the New Orleans area, including in Kenner, central Metairie, and Terrytown in Jefferson Parish and eastern New Orleans and Mid-City in New Orleans proper.[114]

Prior to Hurricane Katrina there were few persons of Brazilian origin in the city, but after Katrina and by 2008 a population emerged. Portuguese speakers were the second most numerous group to take English as a second language classes in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, after Spanish speakers. Many Brazilians worked in skilled trades such as tile and flooring; fewer worked as day laborers than did Latinos. Many had moved to New Orleans from Brazilian communities in the Northeastern United States, Florida, and Georgia. Brazilians settled throughout the New Orleans metropolitan area. Most of the Brazilians were undocumented immigrants. In January 2008 Bruce Nolan of the Houston Chronicle stated that estimates of the New Orleans Brazilian population had a mid-range of 3,000, but no entity had determined exactly how many Brazilians resided in the city. By 2008 Brazilians had opened many small churches, shops, and restaurants catering to their community.[115]

Changes in population

The city of New Orleans faced a decreasing population before and after Hurricane Katrina. Beginning in 1960, the population of the city decreased[116][117] due to several factors. Jobs and population followed the cycles of oil and tourism, the city's population declined as suburbanization increased (in common with many US cities),[118] and jobs migrated to surrounding parishes.[119] This economic and population decline resulted in high levels of poverty among city residents; in 1960 it was the fifth-highest of all US cities,[120] and was almost twice the national average in 2005, at 24.5%.[118] New Orleans experienced an increase in residential segregation from 1900 to 1980, leaving the poor, who were disproportionately African American[119] in older, low-lying locations within the city's core. These areas were especially susceptible to flood and storm damage.[121]

Hurricane Katrina, which displaced 800,000 people in total, contributed significantly to the continued decline of New Orleans' population. As of 2010[update], the population of New Orleans was at 76% of what it was in 2005.[122] African Americans, renters, the elderly, and people with low income were disproportionately affected by Hurricane Katrina, compared to affluent and white residents.[123][124] In the aftermath of Katrina, city government commissioned groups such as Bring New Orleans Back Commission, the New Orleans Neighborhood Rebuilding Plan, the Unified New Orleans Plan, and the Office of Recovery Management to contribute to plans addressing depopulation. Their ideas included shrinking the city's footprint from before the storm, incorporating community voices into development plans, and creating green spaces,[123] some of which incited controversy.[125][126]

From 2010 to 2014 the city grew by 12%, adding an average of more than 10,000 new residents each year following the 2010 Census.[90]

Economy

New Orleans has one of the largest and busiest ports in the world, and metropolitan New Orleans is a center of maritime industry. The New Orleans region also accounts for a significant portion of the nation's oil refining and petrochemical production, and serves as a white-collar corporate base for onshore and offshore petroleum and natural gas production.

New Orleans is a center for higher learning, with over 50,000 students enrolled in the region's eleven two- and four-year degree granting institutions. A top-50 research university, Tulane University, is located in New Orleans' Uptown neighborhood. Metropolitan New Orleans is a major regional hub for the health care industry and boasts a small, globally competitive manufacturing sector. The center city possesses a rapidly growing, entrepreneurial creative industries sector, and is renowned for its cultural tourism. Greater New Orleans, Inc. (GNO, Inc.)[127] acts as the first point-of-contact for regional economic development, coordinating between Louisiana's Department of Economic Development and the various parochial business development agencies.

Port

New Orleans was developed as a strategically located trading entrepôt, and it remains, above all, a crucial transportation hub and distribution center for waterborne commerce. The Port of New Orleans is the 5th-largest port in the United States based on volume of cargo handled, and second-largest in the state after the Port of South Louisiana. It is the 12th-largest in the U.S. based on value of cargo. The Port of South Louisiana, also based in the New Orleans area, is the world's busiest in terms of bulk tonnage. When combined with the Port of New Orleans, it forms the 4th-largest port system in volume handled. Many shipbuilding, shipping, logistics, freight forwarding and commodity brokerage firms either are based in metropolitan New Orleans or maintain a large local presence. Examples include Intermarine, Bisso Towboat, Northrop Grumman Ship Systems, Trinity Yachts, Expeditors International, Bollinger Shipyards, IMTT, International Coffee Corp, Boasso America, Transoceanic Shipping, Transportation Consultants Inc., Dupuy Storage & Forwarding and Silocaf. The largest coffee-roasting plant in the world, operated by Folgers, is located in New Orleans East.

Like Houston, New Orleans is located in proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and the many oil rigs that lie just offshore. Louisiana ranks fifth among states in oil production and eighth in reserves in the United States. It has two of the four Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) storage facilities: West Hackberry in Cameron Parish and Bayou Choctaw in Iberville Parish. Other infrastructure includes 17 petroleum refineries, with a combined crude oil distillation capacity of nearly 2.8 million barrels per day (450,000 m3/d), the second highest in the nation after Texas. Louisiana's numerous ports include the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP), which is capable of receiving ultra large oil tankers. Given the quantity of oil importing, Louisiana is home to many major pipelines supplying the nation: Crude Oil (Exxon, Chevron, BP, Texaco, Shell, Scurloch-Permian, Mid-Valley, Calumet, Conoco, Koch Industries, Unocal, U.S. Dept. of Energy, Locap); Product (TEPPCO Partners, Colonial, Plantation, Explorer, Texaco, Collins); and Liquefied Petroleum Gas (Dixie, TEPPCO, Black Lake, Koch, Chevron, Dynegy, Kinder Morgan Energy Partners, Dow Chemical Company, Bridgeline, FMP, Tejas, Texaco, UTP).[128] Several major energy companies have regional headquarters in the city or its suburbs, including Royal Dutch Shell, Eni and Chevron. Numerous other energy producers and oilfield services companies are also headquartered in the city or region, and the sector supports a large professional services base of specialized engineering and design firms, as well as a term office for the federal government's Minerals Management Service.

Business

The city is the home to a single Fortune 500 company: Entergy, a power generation utility and nuclear powerplant operations specialist. In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the city lost its other Fortune 500 company, Freeport-McMoRan, when it merged its copper and gold exploration unit with an Arizona company and relocated that division to Phoenix, Arizona. Its McMoRan Exploration affiliate remains headquartered in New Orleans. Other companies either headquartered or with significant operations in New Orleans include: Pan American Life Insurance, Pool Corp, Rolls-Royce, Newpark Resources, AT&T, TurboSquid, iSeatz, IBM, Navtech, Superior Energy Services, Textron Marine & Land Systems, McDermott International, Pellerin Milnor, Lockheed Martin, Imperial Trading, Laitram, Harrah's Entertainment, Stewart Enterprises, Edison Chouest Offshore, Zatarain's, Waldemar S. Nelson & Co., Whitney National Bank, Capital One, Tidewater Marine, Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits, Parsons Brinckerhoff, MWH Global, CH2M HILL, Energy Partners Ltd, The Receivables Exchange, GE Capital, and Smoothie King.

Tourist and convention business

Tourism is another staple of the city's economy. Perhaps more visible than any other sector, New Orleans' tourist and convention industry is a $5.5 billion juggernaut that accounts for 40 percent of New Orleans' tax revenues. In 2004, the hospitality industry employed 85,000 people, making it New Orleans' top economic sector as measured by employment totals.[129] The city also hosts the World Cultural Economic Forum (WCEF). The forum, held annually at the New Orleans Morial Convention Center, is directed toward promoting cultural and economic development opportunities through the strategic convening of cultural ambassadors and leaders from around the world. The first WCEF took place in October 2008.[130]

Other

Federal agencies and the Armed forces have significant facilities in the area. The U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals operates at the US Courthouse downtown. NASA's Michoud Assembly Facility is located in New Orleans East and is operated by Lockheed Martin. It is a large manufacturing facility that produced the external fuel tanks for the space shuttles. The Michoud facility lies within the enormous New Orleans Regional Business Park, also home to the National Finance Center, operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Crescent Crown distribution center. Other large governmental installations include the U.S. Navy's Space and Naval Warfare (SPAWAR) Systems Command, located within the University of New Orleans Research and Technology Park in Gentilly, Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base New Orleans; and the headquarters for the Marine Force Reserves in Federal City in Algiers.

Top employers

According to the City's 2008 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[131] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ochsner Health System | 10,000 |

| 2 | Tulane University | 3,700 |

| 3 | Acme Truck Line | 2,100 |

| 4 | Al Copeland Investments | 2,071 |

| 5 | Vinson Guard Services | 1,700 |

| 6 | Touro Infirmary | 1,514 |

| 7 | American Nursing Services | 1,500 |

| 7 | Boh Bros. Construction | 1,500 |

| 9 | Laitram | 1,166 |

| 10 | United States Services Group | 1,004 |

Culture and contemporary life

Tourism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

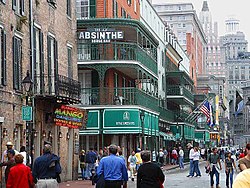

New Orleans has many visitor attractions, from the world-renowned French Quarter; to St. Charles Avenue, (home of Tulane and Loyola Universities, the historic Pontchartrain Hotel, and many 19th-century mansions); to Magazine Street, with its boutique stores and antique shops.

According to current travel guides, New Orleans is one of the top ten most-visited cities in the United States; 10.1 million visitors came to New Orleans in 2004.[129][132] Prior to Hurricane Katrina (2005), there were 265 hotels with 38,338 rooms in the Greater New Orleans Area. In May 2007, there were over 140 hotels and motels in operation with over 31,000 rooms.[133]

A 2009 Travel + Leisure poll of "America's Favorite Cities" ranked New Orleans first in ten categories, the most first-place rankings of the 30 cities included. According to the poll, New Orleans is the best U.S. city as a spring break destination and for "wild weekends", stylish boutique hotels, cocktail hours, singles/bar scenes, live music/concerts and bands, antique and vintage shops, cafés/coffee bars, neighborhood restaurants, and people watching. The city also ranked second for the following: friendliness (behind Charleston, South Carolina), gay-friendliness (behind San Francisco), bed and breakfast hotels/inns, and ethnic food. However, the city was voted last in terms of active [?] residents, and it placed near the bottom in cleanliness, safety, and as a family destination.[134][135]

The French Quarter (known locally as "the Quarter" or Vieux Carré), which was the colonial-era city and is bounded by the Mississippi River, Rampart Street, Canal Street, and Esplanade Avenue, contains many popular hotels, bars, and nightclubs. Notable tourist attractions in the Quarter include Bourbon Street, Jackson Square, St. Louis Cathedral, the French Market (including Café du Monde, famous for café au lait and beignets), and Preservation Hall. Also in the French Quarter is the old New Orleans Mint, a former branch of the United States Mint which now operates as a museum, and The Historic New Orleans Collection, a museum and research center housing art and artifacts relating to the history of New Orleans and the Gulf South.

Close to the Quarter is the Tremé community, which contains the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park and the New Orleans African American Museum — a site which is listed on the Louisiana African American Heritage Trail.

To tour the port, one can ride the Natchez, an authentic steamboat with a calliope, which cruises the Mississippi the length of the city twice daily. Unlike most other places in the United States, New Orleans has become widely known for its element of elegant decay. The city's historic cemeteries and their distinct above-ground tombs are attractions in themselves, the oldest and most famous of which, Saint Louis Cemetery, greatly resembles Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

The National WWII Museum, opened in the Warehouse District in 2000 as the "National D-Day Museum," has undergone a major expansion. Nearby, Confederate Memorial Hall, the oldest continually-operating museum in Louisiana (although under renovation since Katrina), contains the second-largest collection of Confederate Civil War memorabilia in the world. Art museums in the city include the Contemporary Arts Center, the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) in City Park, and the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.

New Orleans also boasts a decidedly natural side. It is home to the Audubon Nature Institute (which consists of Audubon Park, the Audubon Zoo, the Aquarium of the Americas, and the Audubon Insectarium), and home to gardens which include Longue Vue House and Gardens and the New Orleans Botanical Garden. City Park, one of the country's most expansive and visited urban parks, has one of the largest stands (if not the largest stand) of oak trees in the world.

There are also various points of interest in the surrounding areas. Many wetlands are found in close proximity to the city, including Honey Island Swamp and Barataria Preserve. Chalmette Battlefield and National Cemetery, located just south of the city, is the site of the 1815 Battle of New Orleans.

In 2009, New Orleans ranked No. 7 on Newsmax magazine's list of the "Top 25 Most Uniquely American Cities and Towns", a piece written by current CBS News travel editor Peter Greenberg. In determining his ranking, Greenberg cited the city's rebuilding effort post-Katrina as well as its mission to become eco-friendly.[136]

Entertainment and performing arts

The New Orleans area is home to numerous celebrations, the most popular of which is Carnival, often referred to as Mardi Gras. Carnival officially begins on the Feast of the Epiphany, also known as the "Twelfth Night". Mardi Gras (French for "Fat Tuesday"), the final and grandest day of festivities, is the last Tuesday before the Catholic liturgical season of Lent, which commences on Ash Wednesday.

The largest of the city's many music festivals is the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Commonly referred to simply as "Jazz Fest", it is one of the largest music festivals in the nation, featuring crowds of people from all over the world, coming to experience music, food, arts, and crafts. Despite the name, it features not only jazz but a large variety of music, including both native Louisiana music and international artists. Along with Jazz Fest, New Orleans' Voodoo Experience ("Voodoo Fest") and the Essence Music Festival are both large music festivals featuring local and international artists.

Other major festivals held in the city include Southern Decadence, the French Quarter Festival, and the Tennessee Williams/ New Orleans Literary Festival.

In 2002, Louisiana began offering tax incentives for film and television production. This led to a substantial increase in the number of films shot in the New Orleans area and brought the nickname "Hollywood South." Films which have been filmed or produced in and around New Orleans include: Ray, Runaway Jury, The Pelican Brief, Glory Road, All the King's Men, Déjà Vu, Last Holiday, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, 12 Years a Slave, and numerous others. In 2006, work began on the Louisiana Film & Television studio complex, based in the Tremé neighborhood.[137] Louisiana began to offer similar tax incentives for music and theater productions in 2007, leading many to begin referring to New Orleans as "Broadway South."[138]

The first theatre in New Orleans was the French-language Theatre de la Rue Saint Pierre, which opened in 1792. The first opera in New Orleans was given there in 1796. In the nineteenth century the city was the home of two of America's most important venues for the performance of French opera, the Théâtre d'Orléans and later the French Opera House. Today, opera is performed by the New Orleans Opera.

New Orleans has always been a significant center for music, showcasing its intertwined European, Latin American, and African cultures. The city's unique musical heritage was born in its colonial and early American days from a unique blending of European musical instruments with African rhythms. As the only North American city to have allowed slaves to gather in public and play their native music (largely in Congo Square, now located within Louis Armstrong Park), New Orleans gave birth to an indigenous music: jazz. Soon, brass bands formed, gaining popular attraction which continues today. The Louis Armstrong Park area, near the French Quarter in Tremé, contains the New Orleans Jazz National Historical Park. The city's music was later significantly influenced by Acadiana, home of Cajun and Zydeco music, and by Delta blues.

New Orleans' unique musical culture is further evident in its traditional funerals. A spin on military brass band funerals, New Orleans traditional funerals feature sad music (mostly dirges and hymns) on the way to the cemetery and happier music (hot jazz) on the way back. Such musical funerals are still held when a local musician, a member of a social club, krewe, or benevolent society, or a noted dignitary has passed. Until the 1990s, most locals preferred to call these "funerals with music", but visitors to the city have long dubbed them "jazz funerals."

Much later in its musical development, New Orleans was home to a distinctive brand of rhythm and blues that contributed greatly to the growth of rock and roll. An example of the New Orleans' sound in the 1960s is the #1 US hit "Chapel of Love" by the Dixie Cups, a song which knocked the Beatles out of the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100. New Orleans became a hotbed for funk music in the 1960s and 1970s, and by the late 1980s, it had developed its own localized variant of hip hop, called bounce music. While never commercially successful outside of the Deep South, it remained immensely popular in the poorer neighborhoods of the city throughout the 1990s.

A cousin of bounce, New Orleans hip hop has seen commercial success locally and internationally, producing Lil Wayne, Master P, Birdman, Juvenile, Cash Money Records, and No Limit Records. Additionally, the wave of popularity of cowpunk, a fast form of southern rock, originated with the help of several local bands, such as The Radiators, Better Than Ezra, Cowboy Mouth, and Dash Rip Rock. Throughout the 1990s, many sludge metal bands started in the area. New Orleans' heavy metal bands like Eyehategod,[139] Soilent Green,[140] Crowbar,[141] and Down[142] have incorporated styles such as hardcore punk, doom metal, and southern rock to create an original and heady brew of swampy and aggravated metal that has largely avoided standardization.[139][140][141][142]

New Orleans is the southern terminus of the famed Highway 61.

Food

New Orleans is world-famous for its food. The indigenous cuisine is distinctive and influential. New Orleans food developed from centuries of amalgamation of the local Creole, haute Creole, and New Orleans French cuisines. Local ingredients, French, Spanish, Italian, African, Native American, Cajun, Chinese, and a hint of Cuban traditions combine to produce a truly unique and easily recognizable Louisiana flavor.

New Orleans is known for specialties like beignets (locally pronounced like "ben-yays"), square-shaped fried pastries that could be called "French doughnuts" (served with café au lait made with a blend of coffee and chicory rather than only coffee); and Po-boy[143] and Italian Muffuletta sandwiches; Gulf oysters on the half-shell, fried oysters, boiled crawfish, and other seafood; étouffée, jambalaya, gumbo, and other Creole dishes; and the Monday favorite of red beans and rice. (Louis Armstrong often signed his letters, "Red beans and ricely yours".) Another New Orleans specialty is the praline locally /ˈprɑːliːn/, a candy made with brown sugar, granulated sugar, cream, butter, and pecans. The city also has notable street food[144] including the Asian inspired beef Yaka mein.

Dialect

New Orleans has developed a distinctive local dialect of American English over the years that is neither Cajun nor the stereotypical Southern accent, so often misportrayed by film and television actors. It does, like earlier Southern Englishes, feature frequent deletion of the pre-consonantal "r". This dialect is quite similar to New York City area accents such as "Brooklynese", to people unfamiliar with either.[145] There are many theories regarding how it came to be, but it likely resulted from New Orleans' geographic isolation by water and the fact that the city was a major immigration port throughout the 19th century. As a result, many of the ethnic groups who reside in Brooklyn also reside in New Orleans, such as the Irish, Italians (especially Sicilians), and Germans, among others, as well as a very sizable Jewish community.[146]

One of the strongest varieties of the New Orleans accent is sometimes identified as the Yat dialect, from the greeting "Where y'at?" This distinctive accent is dying out generation by generation in the city itself, but remains very strong in the surrounding parishes.

Less visibly, various ethnic groups throughout the area have retained their distinctive language traditions to this day. Although rare, languages still spoken are the Kreyol Lwiziyen by the Creoles; an archaic Louisiana-Canarian Spanish dialect spoken by the Isleño people and older members of the population; and Cajun.

Sports

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded | Titles | Record Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Orleans Saints | American football | NFL | Mercedes-Benz Superdome (73,208) | 1967 | 1 | 73,043 |

| New Orleans Pelicans | Basketball | NBA | Smoothie King Center (16,867; 18,500 in NBA Playoff games) | 2002 | 0 | 18,444 |

| New Orleans Baby Cakes | Baseball | PCL | Shrine on Airline (10,000) | 1993 | 14 | 11,012 |

New Orleans' professional sports teams include the 2009 Super Bowl XLIV champion New Orleans Saints (NFL), the New Orleans Pelicans (NBA), and the New Orleans Baby Cakes (PCL).[147] It is also home to the Big Easy Rollergirls, an all-female flat track roller derby team, and the New Orleans Blaze, a women's football team.[148][149] A local group of investors began conducting a study in 2007 to see if the city could support a Major League Soccer team.[150] New Orleans is also home to two NCAA Division I athletic programs, the Tulane Green Wave of the American Athletic Conference and the UNO Privateers of the Southland Conference.