Persian language: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

{{main|Persian dialects and varieties}} |

{{main|Persian dialects and varieties}} |

||

Communication is generally mutually intelligible between Iranians, Tajiks, and Persian-speaking Afghans; however, by popular definition: |

Communication is generally mutually intelligible between Iranians, Tajiks, and Persian-speaking Afghans; however, by popular definition: |

||

*[[Dari (Afghanistan)|Dari]] is the local name for the eastern dialect of Persian, one of the two official languages of [[Afghanistan]], including [[Hazaragi]] — spoken by the [[Hazara]] people of central Afghanistan. In 'Dari' The wording and pronunciation is somewhat different than the modern Persian language. In Iran |

*[[Dari (Afghanistan)|Dari]] is the local name for the eastern dialect of Persian, one of the two official languages of [[Afghanistan]], including [[Hazaragi]] — spoken by the [[Hazara]] people of central Afghanistan. In 'Dari' The wording and pronunciation is somewhat different than the modern Persian language. In Iran you will find ‘Dari’ writings used only in the old notes or literature textbooks. Both languages are almost understandable for someone speaking the other one. |

||

*[[Tajik language|Tajik]] could also be considered an eastern dialect of Persian, but, unlike Iranian and Afghan Persian, it is written in the [[Cyrillic script]]. |

*[[Tajik language|Tajik]] could also be considered an eastern dialect of Persian, but, unlike Iranian and Afghan Persian, it is written in the [[Cyrillic script]]. |

||

Revision as of 09:52, 17 September 2006

| Persian | |

|---|---|

| فارسی (transliteration: Fārsi) پارسی (transliteration: Pārsi) | |

| Native to | Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and neighboring countries. |

| Region | Middle East, Central Asia |

Native speakers | 71 million native 110 million total |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Iran, Tajikistan, Afghanistan |

| Regulated by | Academy of Persian Language and Literature Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | fa |

| ISO 639-2 | per (B) fas (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | Variously:fas – Persianprs – Eastern Farsipes – Western Farsitgk – Tajikaiq – Aimaqbhh – Bukharicdeh – Dehwaridrw – Darwazihaz – Hazaragijpr – Dzhidiphv – Pahlavani |

Persian is an Indo-European language spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Bahrain, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, Southern Russia, neighboring countries, and elsewhere. It is derived from the language of the ancient Persian people. It is part of the Iranian branch of the Indo-Iranian language family. It is known as

- فارسی (transliteration: Fārsi) or پارسی (transliteration: Pārsi), local name in Iran, Afghanistan and Tajikistan,

- Tajik, local name in Central Asia.

- Dari, name given to classical Persian poetry and court language, as well as to Persian dialects spoken in Tajikistan and Afghanistan.

Prior to British colonization, Persian was also widely used as a second language in the Indian subcontinent; it took prominence as the language of culture and education in several Muslim courts in the subcontinent throughout the Middle Ages and became the "official language" under the Mughal emperors. Only in 1832 did the British force the subcontinent to begin conducting business in English instead of the traditional Persian.[1] Evidence of its former rank in the region can still be seen by the extent of its influence on Hindi, Bengali, and Urdu, as well as the popularity that Persian literature still enjoys in the region. Persian and its dialects have official-language status in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan. According to CIA World Factbook, there are 71 million native speakers of Persian in Iran [1], Afghanistan [2], Tajikistan [3] and Uzbekistan [4] and there are about the same number other peoples who can speak Persian throughout the world. It belongs to the Indo-European language family, and is of the Subject Object Verb type. UNESCO was asked to select Persian as one of its languages in 2006.[5]

History

Persian is a member of the Indo-European family of languages, within that family to the satem-languages family, and within that family it belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch. Scholars believe the Iranian sub-branch consists of the following chronological linguistic path: Old Iranian (Avestan and Old Persian) → Middle Iranian (Pahlavi Middle Persian and several other languages) → Modern Iranian (Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and several other languages), c. 900 to present.

Old Persian, the main language of the Achaemenid inscriptions, should not be confused with the non-Indo-European Elamite language (see Behistun inscription). Over this period, the morphology of the language was simplified from the complex conjugation and declension system of Old Persian to the almost completely regularized morphology and rigid syntax of Modern Persian, in a manner often described as paralleling the development of English. Additionally, many words were introduced from neighboring languages, including Aramaic and Greek in earlier times, and later Arabic and to a lesser extent Turkish. In more recent times, some Western European words have entered the language (notably from French and English).

The language itself has greatly developed during the centuries. Due to technological developments, new words and idioms are created and enter into Persian like any other language. In Tehran the Academy of Persian Language and Literature is a center that evaluates the new words in order to initiate and advise their Persian equivalents. In Afghanistan, the Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan does the same for the Persian language in Afghanistan.

In addition to its status in Afghanistan, Iran, and - recently - Tajikistan, the Persian language has been popularly long regarded as the sole or official tongue and islamically suitable for Pakistan according to the Pakistan Language Movement as a uniting binding force behind Muslim federalism with its western neighbours on a historical, geographically and a cultural basis; thereby naturally adopting it as the National Language of Pakistan.

Nomenclature

Persian, the more widely used name of the language in English, is an Anglicized form derived from Latin *Persianus < Latin Persia < Greek Persis, a Hellenized form of Old Persian Parsa. Farsi is the Arabicized form of Parsi, due to a lack of the /p/ phoneme in Standard Arabic. Native Persian speakers typically call it “Fārsi” in modern usage. In English, however, the language has historically been known as "Persian". After the 1979 Iranian Revolution many Iranians migrating to the West continued to use 'Farsi' to identify their language in English and the word became commonplace in English-speaking countries.

The Academy of Persian Language and Literature has argued in an official pronouncement [6] that the name "Persian" is more appropriate, as it has the longer tradition in the western languages and better expresses the role of the language as a mark of cultural and national continuity. On the other hand, "Farsi" is also encountered frequently in the linguistic literature as a name for the language, used both by Iranian and by foreign authors.[2] The international language encoding standard ISO 639-1 uses the code "fa", as its coding system is based on the local names. The more detailed draft ISO 639-3 uses the name "Persian" (code "fas") for the larger unit ("macrolanguage") spoken across Iran and Afghanistan, but "Eastern Farsi" and "Western Farsi" for two of its subdivisions (roughly coinciding with the varieties in Afghanistan and those in Iran, respectively) [7]. Ethnologue, in turn, includes "Farsi, Eastern" and "Farsi, Western" as two separate entries and lists "Persian" and "Parsi" as alternative names for each, besides "Irani" for the western and "Dari" for the eastern form ( [8], [9]). A similar terminology, but with even more subdivisions, is also adopted by the "Linguist List", where "Persian" appears as a subgrouping under "Southwest Western Iranian" ([10]). Currently, all International broadcasting radios with services in the Persian language (e.g. VOA, BBC, DW, RFE/RL, etc.) use "Persian Service", in lieu of "Farsi Service." This is also the case for the American Association of Teachers of Persian, The Centre for Promotion of Persian Language and Literature, and many of the leading scholars of Persian language. [11] [12]

Dialects and close languages

Communication is generally mutually intelligible between Iranians, Tajiks, and Persian-speaking Afghans; however, by popular definition:

- Dari is the local name for the eastern dialect of Persian, one of the two official languages of Afghanistan, including Hazaragi — spoken by the Hazara people of central Afghanistan. In 'Dari' The wording and pronunciation is somewhat different than the modern Persian language. In Iran you will find ‘Dari’ writings used only in the old notes or literature textbooks. Both languages are almost understandable for someone speaking the other one.

- Tajik could also be considered an eastern dialect of Persian, but, unlike Iranian and Afghan Persian, it is written in the Cyrillic script.

Ethnologue offers another classification for dialects of Persian language. According to this source, dialects of this language include the following:[13]

- Western Persian (in Iran)

- Eastern Persian (in Afghanistan)

- Tajik (in Tajikistan)

- Hazaragi (in Afghanistan)

- Aimaq (in Afghanistan)

- Bukharic (in Israel, Uzbekistan)

- Dehwari (in Pakistan)

- Darwazi (in Afghanistan)

- Dzhidi (in Israel)

- Pahlavani (in Afghanistan)

The following are some of the closely related languages of various Iranian peoples within modern Iran proper:

- Mazandarani, spoken in northern Iran mainly in the province of Mazandaran.

- Gileki (or Gilaki), spoken in the province of Guilan.

- Talysh (or Talishi), spoken in northern Iran and southern parts of the Republic of Azerbaijan.

- Luri (or Lori), spoken mainly in the southwestern Iranian province of Lorestan and Khuzestan.

- Tat (also Tati or Eshtehardi), spoken in parts of the Iranian provinces of East Azarbaijan, Zanjan and Qazvin.

- Dari or Gabri, spoken originally in Yazd and Kerman by the Zoroastrians of Iran. Also called Yazdi by some.

Orthography

The vast majority of modern Persian text is written in a form of the Arabic alphabet. In recent years the Latin alphabet has been used by some for technological or internationalization reasons. Tajik, which is considered by many linguists to be a Persian dialect influenced by Russian, is written with the Cyrillic alphabet in Tajikistan.

Persian alphabet

Modern Persian is normally written using a modified variant of the Arabic alphabet with different pronunciation of the letters.

Script adoption

After the conversion of Persia to Islam (see Islamic conquest of Iran), it took approximately 150 years before Persians adopted the Arabic alphabet as a replacement for the older alphabet. Previously, two different alphabets were used for the Persian language (Middle Persian, or Pahlavi, at that time): one was also called Pahlavi and was a modified version of the Aramaic alphabet, and the other was a native Iranian alphabet called Dîndapirak>Din Dabire (literally: religion script).

Additions

The Persian alphabet adds four letters to the Arabic alphabet, due to the fact that four sounds that exist in Persian do not exist in Arabic, as they come from separate language families. Some people call this modified alphabet the Perso-Arabic alphabet. The additional four letters are:

| sound | shape | Unicode name |

| [p] | پ | Peh |

| [tʃ] (ch) | چ | Tcheh |

| [ʒ] (zh) | ژ | Zheh |

| [g] | گ | Gaf |

Variations

Many Persian words with an Arabic root are spelled differently from the original Arabic word. Alef with hamza below ( إ ) always changes to alef ( ا ); teh marbuta ( ة ) usually, but not always, changes to teh ( ت ) or heh ( ه ); and words using various hamzas get spelled with yet another kind of hamza (so that مسؤول becomes مسئول).

The letters different in shape are:

| sound | original Arabic letter | modified Persian letter | name |

| [k] | ك | ک | Kaf |

| [j] (y) and [iː], or rarely [ɑː] | ي or ى | ی | Yeh |

The diacritical marks used in the Arabic script, a.k.a. harakat, are also used in Persian, although some of them have different pronunciations. For example, an Arabic Damma is pronounced /u/, while in Persian it is pronounced /o/.

The Persian variant also adds the notion of a pseudo-space to the Arabic script, called a Zero-width non-joiner (ZWNJ) by the Unicode Standard. It acts like a space in disconnecting two otherwise-joining adjacent letters, but does not have a visual width.

Word boundaries

In written text, words are usually separated by a space. Compounds and detachable morphemes (i.e., morphemes following a word ending in final form character), however, are written without a space separating them. In other words, the two parts of a compound appear next to each other but the first element in the compound will usually end in a final form character, hence it would be possible to recognize the two parts of the compound. This format is not very consistent, however, and sometimes words can appear without a space between them. If the first word ends in a character that has a final form, then we can easily distinguish the word boundary. But if the first word ends in one of the characters that have only one form, the end of the word is not clear. Although this latter case is usually avoided in written text, it is not rare. Furthermore, a space is sometimes inserted between a word and the morpheme. In such cases, the morpheme needs to be reattached (or the space eliminated) before proceeding to the morphological analysis of the text.

Extensions to other languages

The features of the Persian variant have been taken for other languages, such as Pashto or Urdu, and have sometimes been further extended with new letters or punctuation.

Latin alphabet

The Universal Persian (UniPers / Pârsiye Jahâni) Alphabet is a Latin-based alphabet created over 50 years ago in Iran and popularized by Mohamed Keyvan, who used it in a number of Persian textbooks for foreigners and travellers. It sidesteps the difficulties of the traditional Arabic-based alphabet, with its multiple letter shapes and ambiguous spellings, and fits particularly well in contemporary electronically written media.

The "International Persian Alphabet" (IPA2)[14], commonly called Pársik, is another Latin-based alphabet developed in recent years mainly by A. Moslehi, a comparative linguist, as a project defined and maintained under the authority of Persian Linguistics Association. It is claimed to be the most accurate and regular one among Latin-based Persian alphabets in which many linguistic aspects of Modern Persian have been observed; however, its rules are not as simple as those of UniPers.

Fingilish, or Penglish, is the name given to texts written in Persian using the Basic Latin alphabet. It is most commonly used in chat, emails and SMS applications.

Cyrillic alphabet

Tajik language written in the Cyrillic alphabet was introduced in the Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic in the late 1930s, replacing the Latin alphabet that had been used since the Bolshevik revolution. After 1939, materials published in Persian in the Perso-Arabic script were banned from the country. [3]

Phonology

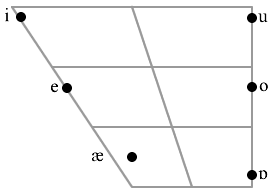

The Persian language has six vowels and twenty-three consonants, including two affricates /ʧ/ (ch) and /ʤ/ (j). Historically, Persian distinguished length: the long vowels /iː/, /uː/, /ɒː/ contrasting with the short vowels /e/, /o/, /æ/ respectively. Modern spoken Persian, however, generally does not make this distinction anymore.

labial |

apico-dentals |

post-alveolars |

velars |

glottals |

|

| voiceless stops | p |

t | ʧ |

k | ʔ |

| voiced stops | b |

d | ʤ |

g | |

| voiceless fricatives | f |

s | ʃ |

x | h |

| voiced fricatives | v |

z |

ʒ |

ɣ | |

| nasals | m |

n | |||

| liquids | l, r |

||||

| glides | j |

Note that /ʧ/ and /ʤ/ are affricates, not stops.

Grammar

Suffixes predominate Persian morphology, though there are a small number of prefixes. Verbs can express tense and aspect, and they agree with the subject in person and number. There is no grammatical gender for nouns, nor are pronouns marked for natural gender.

Normal declarative sentences are structured as “(S) (PP) (O) V”. This means sentences can be comprised of optional subjects, prepositional phrases, and objects, followed by a required verb. If the object is specific, then the object is followed by the word rɑ: and precedes prepositional phrases: “(S) (O + “rɑ:”) (PP) V” [4]

Vocabulary

There are many loanwords in the Persian language, mostly coming from Arabic, English, French, and the Turkic languages.

Persian has likewise influenced the vocabularies of other languages, especially Indo-Iranian languages and Turkic languages. Many Persian words have also found their way into the English language. See List of English words of Persian origin.

See also

- Academy of Persian Language and Literature

- Dzhidi language

- History of Urdu

- List of common phrases in various languages

- List of English words of Persian origin

- List of Persian poets and authors

- Persian grammar

- Persian literature

- Middle Persian literature

- Persian mythology

- Persian phonology

References

- ^ Clawson, Patrick. Eternal Iran, 2005, ISBN 1-4039-6276-6, Palgrave Macmillan, p.6

- ^ For example: A. Gharib, M. Bahar, B. Fooroozanfar, J. Homaii, and R. Yasami. Farsi Grammar. Jahane Danesh, 2nd edition, 2001.

- ^ Perry, J. R. (2005). A Tajik Persian Reference Grammar. Boston: Brill. p. 34. ISBN 90-04-14323-8.

- ^ Mahootian, Shahrzad (1997). Persian. London: Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 0-415-02311-4.