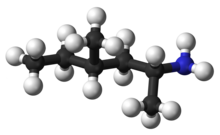

Methylhexanamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | 4-methyl-2-hexanamine; 4-methyl-2-hexylamine; 2-amino-4-methylhexane; 1,3-dimethylamylamine; 1,3-dimethylpentylamine 2-Hexanamine, 4-methyl- (9CI) |

| Routes of administration | Oral, Inhaled |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.997 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C7H17N |

| Molar mass | 115.22 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| (verify) | |

Methylhexanamine (Forthan, Forthane, Floradrene, Geranamine) also spelled methylhexanenamine and known as dimethylamylamine (DMAA), is a dietary supplement[1][2][3] and simple aliphatic amine used as a nasal decongestant, as well as treatment for hypertrophied or hyperplasic oral tissues.[4] It is a vasoconstrictor, and can be administered by inhalation to the nasal mucosa to exert its effect. Methylhexaneamine is also a constituent of flower oil, sold as an integral component of nutritional supplements.[5]

History

In April 1971, Eli Lilly and Company trademarked methylhexanamine under Forthane for potential use as a nasal decongestant. Forthane was also used as a nasal decongestant and as treatment for hypertrophied or hyperplasic oral tissues[4] The trademark for Forthane has since expired, and so methylhexanamine should not be confused with isoflurane, a general inhalation anaesthetic,[6] which has the proprietary name in Australia of Forthane.

Patrick Arnold reintroduced methylhexanamine into the market in 2006 as a dietary supplement,[7][8] after the final ban of ephedrine as a dietary supplement in the United States in 2005. Arnold introduced it under the trademarked name Geranamine, a name held by his company, Proviant Technologies.

Chemistry

Methylhexaneamine may be synthesized by reacting 4-methylhexan-2-one with hydroxylammonium chloride to give the oxime, followed by reduction via sodium in ethanol.

Research

On 6 December 2011, the Cardiorespiratory-Metabolic Laboratory at the University of Memphis published a series of research reports that found commercial products containing methylhexanamine increased fat loss and energy among healthy men and women participants. The research found that energy output was increased by 9% for men and 24% in women when taking products commercially available and containing methylhexanamine.[9]

Uses

Although intended by Eli Lilly to be used as a nasal decongestant, methylhexaneamine has been marketed by certain companies as a dietary supplement in combination with caffeine and other ingredients, under trade names such as Geranamine and Floradrene, to be used as an OTC thermogenic or general purpose stimulant. Methylhexaneamine itself has not been studied intensively and its pharmacological profile has not been evaluated since Eli Lilly filed its patent in 1944, stating that the stimulant effects on the CNS are less than that of the related compounds amphetamine and ephedrine.[10] Despite not being a catecholamine, methylhexanamine exhibits structural similarity to other monoamines such as phenethylamine and amphetamine, which may account for its similar mode of action to these compounds. The only structural difference between methylhexanamine and amphetamine is that methylhexanamine lacks the phenyl or benzene ring which is present in all phenethylamine derivatives, including all amphetamines, containing only 4 of the 6 carbons of the phenyl ring. The difference between geranamine and propylhexedrine is that is lacks two carbons that create a cyclohexyl ring in propylhexedrine and a methyl group on the amine group. Despite these differences, it has a similar mode of action, being a stimulant and having norepinephrinergic effects.

In New Zealand, methylhexanamine (under the name 1,3-dimethylamylamine or DMAA) is an emerging active ingredient of party pills.[11] Side-effects including headache, nausea, and stroke have been reported in recreational users of these products.[12] In November 2009, the New Zealand government indicated that methylhexanamine would be scheduled as a restricted substance.[13] The New Zealand government has not banned methylhexanamine, however, its Ministry of Health has banned bulk powder purchases, but its sale in the form of capsules and tablets is permitted.

Classification as dietary supplement

In the U.S., Methylhexaneamine is classified as a dietary supplement[14] under the Dietary Health Supplement Education Act of 1994.[1][2][3] It is a component of the oil from Pelargonium graveolens, which is approved for use in food. Methylhexaneamine has been demonstrated to comprise 0.66 - 1% of geranium oil,[15] a similar compound to plant ratio as many other commonly available herbs. Even pure synthetic methylhexaneamine is compliant under FDA law, and the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) in particular, as it allows for the synthesis of compounds which were originally found in commonly-known food sources. This law allows for compounds such as Vitamin C, originally stemming from citrus fruits, to be synthesized almost exclusively and still be compliant. (32)

Safety profile

Methylhexanamine's safety profile is similar to caffeine. The LD50 for methylhexaneamine is 39 mg/kg for intravenous and 185 mg/kg for intraperitoneal administration (mouse),[16][17] equivalent to 206 mg intravenously and 978 milligrams intraperitoneally injected for a 143 lb (65 kg) adult human by commonly used equivalency factors. It is important to note that these equivalency factors are never a perfect extrapolation of animal data and they should be taken as a suggestion of possible effects rather than an empirically demonstrated fact. There are many physiological and pharmacological differences between mice and humans that may elicit different effects and potency of a drug between the two animals (this is true of all organisms). A typical dose for supplementation with the pure extract is 25–50 mg, or about 0.5 mg/kg of body weight. Caffeine's LD50 in mice is 62 mg/kg, and for an adult human female is 57 mg/kg, or 3.705 grams intravenously injected.[18][19] Oral toxicity is much lower for caffeine (400-1,000 mg/kg),[20][21] and the oral toxicity of methylhexanamine would similarly be expected to be much lower than intravenous toxicity. Its oral LD50 is currently unknown.

Controversy

In 2009, the World Anti-Doping Agency added methylhexanamine to the 2010 prohibited list.[22]

Methylhexanamine was implicated as a stimulant used by five Jamaican athletes in 2009. JADCO, the Jamaican anti-doping panel, was initially unable to determine whether it was prohibited by the rules,[23] but subsequently decided to impose sanctions on some of the affected athletes on the grounds that the drug was similar in structure to the banned substance tuaminoheptane.[24]

During the 2010 Commonwealth Games, Nigerian athlete Damola Osayemi was stripped of her gold medal in the 100m after methylhexanamine was detected during drug testing.[25] Subsequently, another Nigerian athlete, Samuel Okon, who finished sixth in the 110m hurdles, also tested positive for the drug.[26]

In October 2010, two Portuguese cyclists—Rui Costa and his brother Mario—tested positive for the substance. The samples were taken during the Portuguese National Championships at the end of June.[27]

In October 2010, nine Australian athletes have been found by Australian Sports Anti-doping Authority to have tested positive for the substance. These players may include NRL and AFL players.[28]

In November 2010 two South African rugby union players, Chiliboy Ralepelle and Bjorn Basson, were found to have tested positive for the substance on their annual tour of the Northern Hemisphere, and were immediately sent home from the tour by the South African Rugby Union, although it is possible that the players may have ingested the substance inadvertently in the form of medication for flu symptoms.[29]

In 2010 Belgian National Amateur Masters Champion Rudy Taelman was suspended for one year for a positive test for methylhexanamine. He successfully defended himself from accusations of willful doping by proving that a supplement called "Crack" had caused the non-negative test. It should be noted that he was an active anti-doping advocate, and ironically the one to call for the doping controls to which he was submitted.[30]

In January 2011, the Greek basketball team Iraklis indefinitely suspended Matt Bouldin after he tested positive for methylhexanamine.[31]

American pro tennis player Robert Kendrick was disqualified from the 2011 French Open, and banned from tennis for 12 months by the International Tennis Federation (ITF) after testing positive for Methylhexaneamine at the event. The ban is currently being appealed by Kendrick, as he claims he took a pill to cope with jetlag without knowing it contained the substance, and the ITF wrote in their summary that it did not believe that Kendrick took the substance as a performance enhancer. However, it is the long stated practice of the Tennis Anti-Doping Program that the players are responsible for ensuring that no prohibited substances enter their body, unless they hold a valid exemption for therapeutic use, which Kendrick did not.[citation needed]

In August 2011, American sprinter Mike Rodgers tested positive for methylhexanamine, claiming he drank vodka with an energy drink at a club two days before a meeting in Lignano, Italy, which supposedly caused the positive test.[32]

In October 2011, Canadian wakeboarder Aaron Rathy was stripped of his silver medal at the Pan American Games in Guadalajara, Mexico, for testing positive for methylhexaneamine. In a statement, he blamed the use of the supplement OxyElite Pro, which he did not know contained the banned substance, for testing positive.[33]

Also in October 2011, Saint Louis Cardinals Minor League outfielder Reggie Williams was suspended for 50 games for testing positive for methylhexaneamine. [34]

In December 2011, Triathlete Dmitriy Smurov was suspended for 2 years for testing positive for methylhexaneamine. [35]

See also

References

- ^ a b SEC. 201. [21 U.S.C. 321]

- ^ a b Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994

- ^ a b Chapter I - Dietary Supplement Health And Education Act of 1994

- ^ a b PROCESS FOR THE TREATMENT OF HYPERTROPHIED GUMS

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|country-code=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|issue-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|patent-number=ignored (help) - ^ US Trademark Serial Number: 78542697

- ^ Data Sheet

- ^ Shipley, Amy (May 8, 2006). "Chemist's New Product Contains Hidden Substance". The Washington Post.

- ^ Baseball Prospectus | Under The Knife: 997

- ^ McCarthy, Cameron G. (6 December 2011). "A Finished Dietary Supplement Stimulates Lipolysis and Metabolic Rate in Young Men and Women". Nutrition and Metabolic Insights.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ AMINOALKANES

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|country-code=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-first=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|inventor-last=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|issue-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|patent-number=ignored (help) - ^ "New pill ingredient worries ministry". Television New Zealand. October 4, 2008. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ "New party pills leave four seriously ill". The Dominion Post. January 11, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Steward, Ian (November 9, 2009). "Party pill inventor backs restriction". The Press. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Dietary Supplements

- ^ Ping, Z.; Jun, Q.; Qing, L. (1996), "A Study on the Chemical Constituents of Geranium Oil", Journal of Guizhou Institute of Technology, 25 (1): 82–85

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ JAPMA8 Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association, Scientific Edition. (Washington, DC) V.29-49, 1940-60. For publisher information, see JPMSAE. Volume(issue)/page/year: 42,107,1953

- ^ 85KYAH "Merck Index; an Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals", 11th ed., Rahway, NJ 07065, Merck & Co., Inc. 1989 Volume(issue)/page/year: 11,957,1989

- ^ Jokela, Sirkka; Vartiainen, A. (1959). "Caffeine Poisoning". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 15 (4): 331–334. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1959.tb00302.x.

- ^ Bonati, M.; et al. (1985). "Caffeine distribution in acute toxic response among inbred mice". Toxicology Letters. 29 (1): 25. PMID 4082203.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Bulletin of the International Association of Forensic Toxicologists.Vol. -, Pg. 6, 1973.

- ^ Shum, S.; Seale, C.; Hathaway, D.; Chucovich, V.; Beard, D. (1997). "Acute caffeine ingestion fatalities: management issues". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 39 (4): 228–230. PMID 9251173.

- ^ WADA 2010 Prohibited List (pdf), World Anti-Doping Agency, Monday, 19 September 2009

- ^ "Jamaicans cleared over drug tests". BBC Sport. BBC. August 10, 2009.

- ^ "IAAF wait for Jamaica drug ruling". BBC Sport. BBC. August 11, 2009.

- ^ "Commonwealth Games: Damola Osayemi loses gold medal". BBC Sport. BBC. October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Second Nigerian tests positive at Commonwealth Games". BBC Sport. BBC. October 12, 2010.

- ^ "Rui Costa and his brother test positive". CyclingNews. CyclingNews. October 18, 2010.

- ^ "nine Australian athletes test positive". News. NDTV. October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Springboks test positive". News. BBC. November 15, 2010.

- ^ "Belgian amateur champion receives one-year ban". News. CyclingNews. December 9, 2010.

- ^ Iraklis suspends Bouldin for positive doping test, January 26, 2011

- ^ "American sprinter Michael Rodgers tests positive for banned stimulant". Guardian. 16 August 2011.

- ^ "Canadian medallist tests positive at Pan Ams". 28 October 2011.

- ^ "Minor Leaguer suspended 50 games". MLB.com. 2011-11-1. Retrieved 2011-11-1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ "MHEA-Doping, Dmitriy Smurov 2 year banned". DNF-is-no-option.com. 2011-11-6. Retrieved 2011-11-6.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help)