Berlin U-Bahn

| U-Bahn Berlin | |

|---|---|

| |

U1 crossing Oberbaum Bridge | |

| Overview | |

| Owner | Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) |

| Locale | Berlin |

| Transit type | Rapid transit |

| Number of lines | 10 (numbered U1–U9 and U55)[1] |

| Number of stations | 173[1] |

| Daily ridership | 1,515,342 (average daily, 2017)[2] |

| Annual ridership | 553.1 million (2017)[2] |

| Website | BVG.de – Homepage |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 1902 |

| Operator(s) | Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) |

| Train length | ~100 metres (330 ft) |

| Headway | 4–5 minutes (daytime) |

| Technical | |

| System length | 151.7 km (94.3 mi)[1] |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) |

| Electrification | 750 V DC Third rail |

| Average speed | 30.7 km/h (19.1 mph)[1] |

| Top speed | 72 km/h (45 mph) |

The Berlin U-Bahn ([uː.baːn]; short for Untergrundbahn, "underground railway") is a rapid transit railway in Berlin, the capital city of Germany, and a major part of the city's public transport system. Together with the S-Bahn, a network of suburban train lines, and a tram network that operates mostly in the eastern parts of the city, it serves as the main means of transport in the capital.

Opened in 1902, the U-Bahn serves 173 stations[1] spread across ten lines, with a total track length of 151.7 kilometres (94.3 mi),[1] about 80% of which is underground.[3] Trains run every two to five minutes during peak hours, every five minutes for the rest of the day and every ten minutes in the evening. Over the course of a year, U-Bahn trains travel 132 million km (82.0 million mi),[1] and carry over 400 million passengers.[1] In 2017, 553.1 million passengers rode the U-Bahn.[2] The entire system is maintained and operated by the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe, commonly known as the BVG.

Designed to alleviate traffic flowing into and out of central Berlin, the U-Bahn was rapidly expanded until the city was divided into East and West Berlin at the end of World War II. Although the system remained open to residents of both sides at first, the construction of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent restrictions imposed by the Government of East Germany limited travel across the border. The East Berlin U-Bahn lines from West Berlin were severed, except for two West Berlin lines that ran through East Berlin (U6 and U8). These were allowed to pass through East Berlin without stopping at any of the stations, which were closed. Friedrichstraße was the exception because it was used as a transfer point between U6 and the West Berlin S-Bahn system, and a border crossing into East Berlin. The system was reopened completely following the fall of the Berlin Wall, and German reunification.

The Berlin U-Bahn is the most extensive underground network in Germany.[1] In 2006, travel on the U-Bahn was equivalent to 122.2 million km (76 million mi) of car journeys.[4]

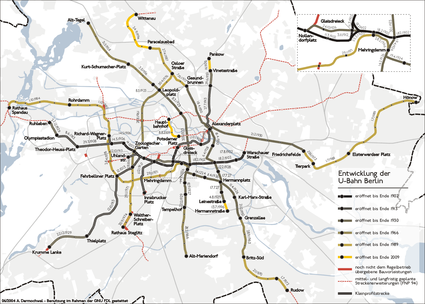

History

The Berlin U-Bahn was built in three major phases:

- Up to 1913: the construction of the Kleinprofil (small profile) network in Berlin, Charlottenburg, Schöneberg, and Wilmersdorf;

- Up to 1930: the introduction of the Großprofil (large profile) network that established the first North-South lines;

- From 1953 on: further development after World War II.

At the end of the 19th century, city planners in Berlin were looking for solutions to the increasing traffic problems facing the city. As potential solutions, industrialist and inventor Ernst Werner von Siemens suggested the construction of elevated railways, while AEG proposed an underground system. Berlin city administrators feared that an underground would damage the sewers, favouring an elevated railway following the path of the former city walls; however, the neighbouring city of Charlottenburg did not share Berlin's fears, and disliked the idea of an elevated railway running along Tauentzienstraße. Years of negotiations followed until, on 10 September 1896, work began on a mostly elevated railway to run between Stralauer Tor and Zoologischer Garten, with a short spur to Potsdamer Platz. Known as the "Stammstrecke", the route was inaugurated on 15 February 1902, and was immediately popular. Before the year ended, the railway had been extended: by 17 August, east to Warschauer Brücke (Warschauer Straße); and, by 14 December, west to Knie (Ernst-Reuter-Platz).

In a bid to secure its own improvement, Schöneberg also wanted a connection to Berlin. The elevated railway company did not believe such a line would be profitable, so the city built the first locally financed underground in Germany. It was opened on 1 December 1910. Just a few months earlier, work began on a fourth line to link Wilmersdorf in the south-west to the growing Berlin U-Bahn.

The early network ran mostly east to west, connecting the richer areas in and around Berlin, as these routes had been deemed the most profitable. In order to open up the network to more of the workers of Berlin, the city wanted north-south lines to be established. In 1920, the surrounding areas were annexed to form Groß-Berlin ("Greater Berlin"), removing the need for many negotiations, and giving the city much greater bargaining power over the private Hochbahngesellschaft ("elevated railway company"). The city also mandated that new lines would use wider carriages—running on the same, standard-gauge track—to provide greater passenger capacity; these became known as the Großprofil ("large profile") network.

Construction of the Nord-Süd-Bahn ("North-South railway") connecting Wedding in the north to Tempelhof and Neukölln in the south had started in December 1912, but halted for the First World War. Work resumed in 1919, although the money shortage caused by hyperinflation slowed progress considerably. On 30 January 1923, the first section opened between Hallesches Tor and Stettiner Bahnhof (Naturkundemuseum), with a continuation to Seestraße following two months later. Desperately underfunded, the new line had to use trains from the old Kleinprofil network; the carriages exits had to be widened to fill the gap to the platforms with wooden boards that passengers jokingly referred to as Blumenbretter ("boards for flower pots"). The line branched at Belle-Alliance-Straße, now (Mehringdamm); the continuation south to Tempelhof opened on 22 December 1929, the branch to Grenzallee on 21 December 1930.

In 1912, plans were approved for AEG to build its own north-south underground line, named the GN-Bahn after its termini, Gesundbrunnen and Neukölln, via Alexanderplatz. Financial difficulties stopped the construction in 1919; the liquidation of AEG-Schnellbahn-AG, and Berlin's commitment to the Nord-Süd-Bahn, prevented any further development until 1926. The first section opened on 17 July 1927 between Boddinstraße and Schönleinstraße, with the intermediate Hermannplatz becoming the first station at which passengers could transfer between two different Großprofil lines. The completed route was opened on 18 April 1930. Before control of the U-Bahn network was handed over completely to the BVG in 1929, the Hochbahngesellschaft started construction on a final line that, in contrast to its previous lines, was built as part of the Großprofil network. The major development was stopped in 1930.

The seizure of power by the National Socialists brought many changes that affected Germany, including the U-Bahn. Most notably, the national flag was hung in every station, and two of the stations were renamed. Extensive plans—mostly the work of architect Albert Speer—were drawn up that included the construction of a circular line crossing the established U-Bahn lines, and new lines or extensions to many outlying districts. Despite such grand plans, no U-Bahn development occurred. In the Nazi period the only addition to Berlin's underground railways was North–South Tunnel of S-Bahn, opened 1936-1939.

During the Second World War, U-Bahn travel soared as car use fell, and many of the underground stations were used as air-raid shelters; however, Allied bombs damaged or destroyed large parts of the U-Bahn system. Although the damage was usually repaired fairly quickly, the reconstructions became more difficult as the war went on. Eventually, on 25 April 1945, the whole system ground to a halt when the power station supplying the network failed. Upon unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany following the Battle for Berlin there were 437 damaged points and 496 damaged vehicles.

The war had damaged or destroyed much of the network; however, 69.5 km (43.2 mi) of track and 93 stations were in use by the end of 1945, and the reconstruction was completed in 1950. Nevertheless, the consequent division of Berlin into East and West sectors brought further changes to the U-Bahn. Although the network spanned all sectors, and residents had freedom of movement, West Berliners increasingly avoided the Soviet sector and, from 1953, loudspeakers on the trains gave warnings when approaching the border, where passage of East Germans into the Western sectors also became subject to restrictions imposed by their government. There was a general strike on 17 June 1953 which closed the sections of the Berlin U-Bahn that traveled through East Berlin. Just after the strike, on the following day, train service on the line A was resumed and the service C was resumed to provide connections to Nordbahnhof and Friedrichstraße.

Between 1953 and 1955, the 200-Kilometre-Plan was drawn up, detailing the future development of the U-Bahn, which would grow to 200 km (124.3 mi). Extending the C line to run from Tegel to Alt-Mariendorf was considered the highest priority: the northern extension to Tegel was opened on 31 May 1958. In order to circumvent East Berlin, and provide rapid-transport connections to the densely populated areas in Steglitz, Wedding, and Reinickendorf, a third north–south line was needed. The first section of line G was built between Leopoldplatz and Spichernstraße, with the intention of extending it at both ends. It had been planned to open the G line on 2 September 1961, but an earlier opening on 28 August was forced by the announcement of the construction of the Berlin Wall.

The next crisis was followed by the Berlin Wall construction on 13 August 1961, which had split the Berlin into east and west. The U2 was split into two sections, and for the north-south lines, trains were not allowed to stop for passengers and become Geisterbahnhöfe ("ghost stations"), patrolled by armed East-German border guards. Only at Friedrichstraße, a designated border crossing point, were passengers allowed to disembark. A further consequence over the years is that most of the Berlin S-Bahn passengers boycotted the Deutsche Reichsbahn, and transferred to the U-Bahn with numerous expansion.

From 9 November 1989, following months of unrest, the travel restrictions placed upon East Germans were lifted. Tens of thousands of East Berliners heard the statement live on television and flooded the border checkpoints, demanding entry into West Berlin. Jannowitzbrücke, a former ghost station, was reopened two days later as an additional crossing point. It was the first station to be reopened after the opening of the Berlin Wall. Other stations, Rosenthaler Platz and Bernauer Straße on the U8 soon followed suit; and by 1 July 1990, all border controls were removed. In the decade following reunification, only three short extensions were made to U-Bahn lines.

In the 1990s some stations in the eastern portion of the city still sported bullet-riddled tiles at their entrances, a result of World War II battle damage during the Battle of Berlin. These were removed by 21 December 2004.

U-Bahn network

Routes

The U-Bahn has ten lines:

| Line | Route | Opened | Length | Stations | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Uhlandstraße – Warschauer Straße | 1902–1926 | 8.814 km (5.477 mi) | 13 | RAL 6018 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Pankow – Ruhleben | 1902–2000 | 20.716 km (12.872 mi) | 29 | RAL 2002 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Krumme Lanke – Warschauer Straße | 1902–1929 | 18.9 km (11.744 mi) | 24 | RAL 6016 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Nollendorfplatz – Innsbrucker Platz | 1910 | 2.864 km (1.780 mi) | 5 | RAL 1023 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Alexanderplatz – Hönow | 1930–1989 | 18.356 km (11.406 mi) | 20 | RAL 8007 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Hauptbahnhof – Brandenburger Tor | 2009 | 1.470 km (0.913 mi)[5] | 3 | RAL 8007 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Alt-Tegel – Alt-Mariendorf | 1923–1966 | 19.888 km (12.358 mi) | 29 | RAL 4005 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Rathaus Spandau – Rudow | 1924–1984 | 31.760 km (19.735 mi) | 40 | RAL 5012 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Wittenau – Hermannstraße | 1927–1996 | 18.042 km (11.211 mi) | 24 | RAL 5010 |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Rathaus Steglitz – Osloer Straße | 1961–1976 | 12.523 km (7.781 mi) | 18 | RAL 2003 |

Stations

Among Berlin's 170 U-Bahn stations[1] there are many with especially striking architecture or unusual design characteristics:

Hermannplatz station resembles something of a U-Bahn cathedral. The platform area is 7 metres high, 132 metres long and 22 metres wide. It was built in connection with the construction of the first North-South Line (Nord-Süd-Bahn), now the U8. The architecturally important department store Karstadt adjacent to the station, was being constructed at the same time. Karstadt contributed a large sum of money towards the decoration of the station and was in return rewarded with direct access from the station to the store. Hermannplatz was also the first U-Bahn station in Berlin to be equipped with escalators. Today, Hermannplatz is a busy interchange between the U7 and U8.

Alexanderplatz station is another of the more notable U-Bahn stations in Berlin, and is an important interchange between three lines (U2, U5 and U8). The first part of the station was opened in 1913 along with an extension of today's U2 line. In the 1920s Alexanderplatz was completely redesigned, both above and below ground. The U-Bahn station was expanded to provide access to the new D (today's U8) and E (today's U5) lines, then under construction. The result was a station with a restrained blue-grey tiled colour-scheme and Berlin's first underground shopping facilities, designed by Alfred Grenander. Over the last few years Alexanderplatz station has, in stages, been restored; the work was due to be finished in 2007.

Wittenbergplatz station is also unusually designed. It opened in 1902 as a simple station with two side platforms, designed to plans created by Paul Wittig. The station was completely redesigned by Alfred Grenander in 1912, with five platform faces, accommodating two new lines, one to Dahlem on today's (U3), and the other to Kurfürstendamm, today's Uhlandstraße (Berlin U-Bahn) on the (U1). A provision for a sixth platform was included but has never been completed. The redesign also featured a new entrance building, which blended into the grand architectural styles of Wittenbergplatz and the nearby KaDeWe department store. The interior of the entrance building was again rebuilt after considerable war damage during World War II, this time in a contemporary 1950s style. This lasted until the early 1980s when the interior was retro-renovated back into its original style. Wittenbergplatz station was presented with a London style "Roundel type" station sign in 1952, the 50th Anniversary of the Berlin U-Bahn. Today's station is an interchange station between the U1, U2 and U3 lines.

The name of the Gleisdreieck (rail triangle) station is reminiscent of a construction which can only be imagined today. The wye was built in the opening year 1902. Plans for a redesign were made soon after, because the wye was already obsolete. An accident on September 26, 1908 which claimed 18 to 21 lives was the final straw. The redesign and expansion of the Turmbahnhof, during which the station was still used, took until 1912. After World War II the station was put back into service on October 21 (lower platform), and November 18 (upper platform), 1945. However, service was interrupted again by the construction of the Berlin Wall. From 1972 onwards no trains ran on the lower platform, because servicing the U2 was no longer profitable due to the parallel traffic on the U1. The lower platform was reactivated in 1983, when the test line of the M-Bahn was built from the Gleisdreieck to the Kemperplatz station. It was broken down again after the fall of the Berlin Wall, since it obstructed parts of the reopened U2. Since 1993 the U1 and U2 trains both service the station again.

Tickets

Berlin public transit passes are available from many places, automated and non-automated, from BVG, Bahn, and authorized third-parties. The Ring-Bahn Line and the other S-Bahn lines are included, as are all U-Bahn lines, buses, trams, ferries, and most trains within the city limits: tickets are valid for all transportation considered part of the Berlin-Regional public transit system.

Ride-passes (tickets) are available in fare classes: Adult and Reduced. Children between the ages of six and 14 and large dogs qualify for the reduced fare. Children below the age of six and small dogs travel free. There are senior discounts in the form of an annual ticket. Residents who have applied for and received a German Disability Identification card confirming 80% or more disability (ID's available from the Versorgungsamt, German Disability Office), can ride without a pass, including an additional person (as a helper). The disability identification card must be in the owner's possession when traveling.

With unemployment in the east averaging 15%, another common fare class in Berlin is the S(ocial)-Class. These identification cards are cleared through the normal government offices, then fulfilled at a BVG ride-pass non-automated location. Provided either by the Job Center (Arbeitsamt) for out-of-work residents or by the Sozialamt for people who cannot work or are disabled, the S-Class ride-passes normally restrict travel to the AB zones and must be renewed (a new pass purchased at a non-automated location) on the 1st of each month.

Additional passes are available for those which want to bring a bicycle on the public transit system. A bicycle-pass is included in the Student-class ride-pass, which is provided through the universities.

For small dogs which can be carried there is no additional fare requirement. For each "large dog", a reduced fare ride-pass must be purchased. Tourist ride-passes, all-day, group passes, and season passes include a dog fare.

BVG ride-passes are issued for specific periods of time, and most require validation with a stamping machine before they are first used. The validation shows the date and time of the first use, and where the ticket was validated (in code), and therefore when the ticket expires. For example, once validated, an all-day pass allows unlimited use from the time of purchase to 3:00 am the following day. Unlike most other metro systems, tickets in Berlin are not checked before entering tram, U-Bahn or S-Bahn stations. They are however checked by the bus drivers upon entering. On the tram, S-Bahn and U-Bahn, a proof-of-payment system is used: there are random spot checks inside by plainclothes fare inspectors who have the right to demand to see each passenger's ticket. Passengers found without a ticket or an expired/invalid ticket are fined €60 per incident. The passenger may be required to pay on the spot, and is required on the spot to give a valid address to which the relevant fine notice can be mailed (it does not have to be in Germany). On the third incident, the BVG calls the offender to court, as there is now a history of 'riding without paying'.

- Fare zones

- Berlin is a part of the Verkehrsverbund Berlin-Brandenburg (Berlin-Brandenburg Transit Authority, VBB), which means ticketing and fare systems are unified with that of the surrounding state of Brandenburg. Berlin is divided into three fare zones, known as A, B, and C. Zone A is the area in the centre of Berlin and is demarcated by the S-Bahn urban rail ring line. Zone B covers the rest of the area within the city borders, and Zone C includes the immediate surroundings of Berlin. Zone C is divided into eight parts, each belonging to an administrative district. The Potsdam-Mittelmark area is included in the city district of Potsdam.

- Tickets can be bought for specific fare zones, or multiple zones. Most passengers who live in Berlin buy AB fare zone tickets, while commuters coming in from the suburbs need ABC fare zone tickets. If a ticket not valid for travel in a tariff zone is checked by a ticket inspector, the passenger is subject to a fine.

- Short-term tickets

- Single-journey tickets (Einzeltickets) are issued for use within specific fare zones, namely AB, BC, and ABC. They are only valid for two hours after validation, and cannot be extended. The BVG also offers single-day tickets (Tageskarte), which are valid for the entire day when first validated until 3 a.m. the next morning.

- Long-term tickets

- Long-term paper tickets are issued with validity periods of seven days (7-Tage-Karte), one month (Monatskarten), or one year (Jahreskarte). The BVG is in the process of introducing the plastic MetroCard as a yearly ticket that also has additional features. The Metrocard also permits passengers to make reservations for hire cars at specific times, for example on weekends. It is expected that plastic Metrocards without such features will also be made available as they are more durable and ecofriendly than the paper tickets.

- Tourist passes

- The BVG offers tickets directed specifically for non-resident tourists of Berlin called the WelcomeCard and CityTourCard [1]. WelcomeCards are valid for either 48 or 72 hours, and can be used by one adult and up to three children between the ages of six and 14. WelcomeCards are valid in fare zones ABC, and have the additional benefit of a reduction on entry fees to many museums and tourist attractions. See the Current Prices and Descriptions link for more information.

Underground facilities

A full GSM (GSM-900 and GSM-1800) mobile phone network for Germany's four carriers is in place throughout the U-Bahn system of stations and tunnels. This system was in place by 1995 for the E-Plus network, and was one of the first metro systems to allow mobile telephone use; by the late 1990s the other networks could be used as well. Since 2015, UMTS and LTE is also available for E-Plus and O2 (LTE since 2016) customers.[6]

Many of the carriages on the U-Bahn feature small flat screen displays that feature news headlines from BZ, weekly weather forecasts, and ads for local businesses.

Most major interchange stations have large shopping concourses with banks, supermarkets, and fast food outlets.

Unused stations and tunnels

There are several stations, platforms and tunnels that were built in preparation for future U-Bahn extensions, and others that have been abandoned following planning changes. For example, platforms have already been provided for the planned "U3" at Potsdamer Platz on the planned line to Weißensee. It is unlikely that this line, which had the working title "U3" will ever be built, so the platforms have been partially converted into a location for events and exhibitions. The line number "U3" has been used to re-number the branch to Krumme Lanke, which had been part of "U1".

Line D, today's U8, was intended to run directly under Dresdner Straße via Oranienplatz to Kottbusser Tor. This segment of tunnel was abandoned in favour of a slightly less direct route in order to provide the former Wertheim department store at Moritzplatz with a direct connection. This involved the construction of a 90-degree curve of the line between Moritzplatz and Kottbusser Tor stations. The construction of the tunnel under Dresdner Straße had only been partially completed before abandonment, leaving it with only one track. This tunnel is separated into three parts, as it was blocked by a concrete wall where it crossed the border between East and West Berlin. Another concrete wall separates this tunnel, which now houses a transformer for an electricity supplier, from the never-completed Oranienplatz Station which is located partially under the square of the same name.

Stralauer Tor was a station on the eastern bank of the Spree between Warschauer Straße and Schlesisches Tor stations. It was completely destroyed in World War II. It had been opened in 1902 and was renamed Osthafen in 1924. Today, only struts on the viaduct remain to indicate its location. In the post-Second World War period it was not thought necessary to rebuild the station, due its close proximity to the Warschauer Straße station. Also its location was directly on the border between the Soviet and American sectors. Although a Berlin map dated 1946 shows the station renamed as Bersarinstraße after the Soviet General responsible for restoring civil administration of the city, this name was used later at another location.

Nürnberger Platz station was closed on July 1, 1959. It was replaced by two new stations on either side, Augsburger Straße and an interchange station to the U9 at Spichernstraße. Today, nothing remains of the station as a third track siding was constructed in its place.

Another tunnel, which once connected the U4 to its original depot and workshop at Otzenstraße (Schöneberg), is still in existence. The connection from Innsbrucker Platz station to the depot was severed when a deep level motorway underpass was constructed in the early 1970s; however, the continuation of the tunnel at Eisackstraße is still in existence for a distance of 270 metres and now ends at the former junction to the workshop of the Schöneberg line.

Platforms at five stations, Rathaus Steglitz, Schloßstraße, Walther-Schreiber-Platz, Innsbrucker Platz, and Kleistpark, were provided for the planned but never constructed U10. The U10 platform at Kleistpark has been converted into office space for the BVG. At Schloßstraße, U9 and U10 were planned to share two directional platforms at different levels; the would-be U10 tracks have been abandoned, leaving both platforms used by U9 trains only. The other U10 platforms remain unused and are not generally open to the public.

During the construction of Adenauerplatz (U7) station, which was built in conjunction with an underpass, platforms were also provided for a planned U1 extension from Uhlandstraße to Theodor-Heuss-Platz. A short tunnel section was also constructed in front of the Internationales Congress Centrum (ICC), beneath the Messedamm/Neue Kantstraße junction. This tunnel was built concurrently with a pedestrian subway and was also intended for the planned extension of the U1. The tunnel section, approximately 60 metres long, ends at the location of the planned Messe station adjacent to Berlins central bus station (ZOB). The tunnel is used as a storage area for theater props.

At Jungfernheide station, double U-Bahn platforms similar to those at Schloßstraße were built for the planned extension of the U5. The unused platform sides are fenced off. The finished (U5) tunnel section which leads off towards Tegel airport is now used for firefighting exercises.

Future development

Berlin's chronic financial problems make any expansion not mandated by the Hauptstadtvertrag—the document that regulates the necessary changes to the city as the capital of Germany—unlikely. Furthermore, there is still great rivalry for construction money between the U-Bahn and the S-Bahn. After the construction boom that followed the reunification of the city, enthusiasm for further growth has cooled off; many people feel that Berlin's needs are adequately met by the present U- and S-Bahn. As of 2007, the only proposals receiving serious consideration aim to facilitate travel around the existing system, such as moving Warschauer Straße's U-Bahn station closer to its S-Bahn station.

There are several long-term plans for the U-Bahn that have no estimated time of completion, most of which involve closing short gaps between stations, enabling them to connect to other lines. This would depend on demand, and new developments in the vicinity. New construction of U-Bahn lines is frequently the subject of political discussion with the Berlin CDU, FDP and AfD usually advocating in favor of U-Bahn expansion while the Social Democratic Party, the Greens and the leftist party usually advocate for tram construction instead.

In summary, the plans for the Berlin U-Bahn are as follows:

| Line | Stretch | Projects |

|---|---|---|

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Theodor-Heuss-Platz – Karow-Ost | The segment between Uhlandstraße and Wittenbergplatz might be built further along the Kurfürstendamm to connect to the U7 at Adenauerplatz; more ambitious plans call for this segment to be separated and expanded into its own line, running from Theodor-Heuss-Platz on the U2, through Potsdamer Platz and Alexanderplatz, before connecting with the S-Bahn at Greifswalder Straße, terminating for short Weißensee before splitting into Karow-Ost and Falkenberg. This new line was tentatively designated the U3 until December 2004. This route has been scrapped because of a lack of funds, and the route might even take too long, with unnecessary costs. This line will be operated by driverless trains if the U1 is built. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Rosenthaler Weg – Stadtrandstraße | Following the extension of the U2 to Pankow in 2000, there are plans to continue on to Ossietzkyplatz and Rosenthaler Weg. In the west, an extension is planned from Ruhleben to the U7 terminus, Rathaus Spandau with five more stations to Stadtrandstraße. Only the extension to Rosenthaler Weg is approved in the financial scenario 2030 of the Berlin Senate and has a real chance to be realized. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Krumme Lanke – Ostkreuz | In the south, there are plans to extend the U3 towards the Berlin Mexikoplatz station. Even though this would only take 700 meter of new tracks, the tight budgetary situation of the Berlin Senate hinders the realisation. There's a discussion, whether the U1 should be extended towards the Berlin Ostkreuz station, the most important and frequented S-bahn station in all of Berlin. The line may also be extended to Frankfurter Tor. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Nollendorfplatz – Innsbrucker Platz | There are no plans to extend the line. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Hönow – Berlin Hauptbahnhof | On 8 August 2009, the U55 opened, running from Berlin Hauptbahnhof to Brandenburger Tor – formerly known as Unter den Linden. It is a provisional line; part of a long-planned extension of the U5 from Alexanderplatz to the new central station. Its construction is expected to be completed by 2020.[7]

The U5 extension—known as the Kanzlerlinie (chancellor's line), as it will run through the government quarter—is planned to go through Rotes Rathaus, along Unter den Linden and the Pariser Platz, terminating at Berlin Hauptbahnhof. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Alt-Tegel – Alt-Mariendorf | There are no plans to extend the line. After the closure of Tegel Airport, the U6 will definitely have a branch from Kurt-Schumacher-Platz and continue to the west, to Tegel Airport. However, this will be the actual replacement for metro service to the Tegel Airport, which is a short extension. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Rudow – Staaken | It is planned to extend the U7 in the north-west to Staaken. Due to budgetary situation of the Berlin Senate, the extension is not expected before the year 2050.

There has been a discussion whether the U7 should be extended to the Berlin-Brandenburg Airport, but these plans had already been shelved as the expected patronage was not deemed high enough to justify such an expansion. However, in light of the ballot initiative to keep Tegel Airport open, governing mayor Michael Müller has announced to look into this extension again. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Hermannstraße – Märkisches Viertel | In the north, an extension to the large housing estate named Märkisches Viertel is discussed. As there is only the need of 1,2 kilometer it would be a cheap extension of the existing end point Wittenau. Even though there is no concrete planning at the moment. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Rathaus Steglitz – Osloer Straße | There are no plans to extend the line. |

| Template:BLNMT-icon | Falkenberg – Drakestraße | U10 was in former 200-km plans since 1955. However, the route goes from Falkenberg, to Weißensee, transverse parallel to the future U3 to Potsdamer Platz, followed by turning 150 degrees towards Innsbrucker Platz and Rathaus Stegliz, in order to go Drakestraße (Lichterfelde). Planning for the U10 was officially removed from the Berlin transport master plan in 2003 (Measures 2015), and it is no longer considered part of the public transport network master plan through at least 2030. Nevertheless, the line remains part of Berlin's Land-use policy, which means that new constructions have to accommodate the eventuality of such a line. |

Rolling stock

The Berlin U-Bahn uses 750-volt DC electric trains that run on standard gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) ) tracks. The first trains were based on trams; they have a width of 2.30 m (7.5 ft), and take their power from an upward facing third rail. To accommodate greater passenger numbers without lengthening the trains—which would require costly extended platforms—trains that ran on lines built after World War I were required to be wider. The original trains and lines, which continued to operate, were designated Kleinprofil (small profile), and the newer, wider trains and lines were designated Großprofil (large profile). Großprofil trains are 2.65 m (8.7 ft) wide, and take their power from a downward facing third rail. This is similar to New York City's A Division and B Division systems, where the B Division trains are wider than A Division trains.

Although the two profiles are generally incompatible, Kleinprofil trains have been modified to run on Großprofil lines during three periods of economic difficulty. Between 1923 and 1927 on the Nord-Süd-Bahn, and between 1961 and 1978 on the E line, adapted Kleinprofil trains were used to compensate for the lack of new Großprofil trains: they were widened with wooden boards to reach the platforms; and had their power pickups adapted to accept power from the negatively charged downward-facing third rail, instead of positively charged upward-facing third rail. As of 2017, Class IK Kleinprofil trains are in operation on the Großprofil line U5, after refurbishing the existing F79 rolling stock was deemed unfeasible. They were widened with metal boards by 17.5 cm (6.9 in) on each side and elevated by 7.5 cm (3.0 in) to close the gap to the platforms; their power pickups were designed reversible to work on both profiles. As of October 2019, IK rolling stock is still used on the U5; it is intended to move the trains to Kleinprofil lines once new Großprofil rolling stock has been delivered.

As of 2007, Kleinprofil trains run on the U1, U2, U3, U4 and U5 lines; and Großprofil trains operate on the U5, U55, U6, U7, U8, and U9 routes.

Kleinprofil (small profile)

Kleinprofil trains are 2.30 m (7 ft 6+1⁄2 in) wide, and 3.10 m (10 ft 2 in) high. When the U-Bahn opened in 1902, forty-two multiple units, and twenty-one railroad cars, with a top speed of 50 km/h (31.1 mph), had been built at the Warschauer Brücke workshop. In contrast to the earlier test vehicles, seating was placed along the walls, facing inward, which was considered more comfortable. Until 1927, U-Bahn trains had smoking compartments and third-class carriages. The trains were first updated in 1928; A-II carriages were distinguished by only having three windows, and two sliding doors.

After the division of the city, West Berlin upgraded its U-Bahn trains more rapidly than did East Berlin. The A3 type, introduced in 1960, was modelled on the Großprofil D type, and received regular modifications every few years. Meanwhile, A-I and A-II trains operated exclusively in East Berlin until 1975, when G-I trains, which had a top speed of 70 km/h (43.5 mph), started to travel the Thälmannplatz–Pankow route. These were superseded in 1988 by the G-I/1 type, which used couplings that were incompatible with the older G-I carriages.

Following reunification, the A3 type was again upgraded as the A3L92, the first Kleinprofil type to use AC induction motors. In 2000, prototypes for a Kleinprofil variant of the H series were built; the HK differs from its Großprofil counterpart by not being fully interconnected—carriages are only interconnected within each of the two half-trains.

As of 2005, only trains of the HK, G-I/1 and A3(U/L) types are in active service.

From 2017, new IK-type trains will enter service to replace the remaining examples of type A3L71. Like HK-type trains they will be interconnected and as a result of their regenerative braking will recuperate up to 20% of the energy they require.[8]

| Kleinprofil train types | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901–1945 | West Berlin 1945–1990 | East Berlin 1945–1990 | 1990— | |||||||

| 1901–1904 | A-I | 1960–1961 | A3-60 | 1974 | G | 1993–1995 | A3L92 | |||

| 1906–1913 | 1964 | A3-64 | 1978–1983 | G-I | 2005–2006 | HK | ||||

| 1924–1926 | 1966 | A3-66 | 1983 | G-II | 2014 | IK15 | ||||

| 1928–1929 | A-II | 1966 | A3L66 | 1986–1989 | G-I/1 | 2018–2019 | IK18 | |||

| 1967–1968 | A3L67 | |||||||||

| 1972–1973 | A3L71 | |||||||||

| 1982–1983 | A3L82 | |||||||||

Großprofil (large profile)

Großprofil trains are 2.65 m (8 ft 8+3⁄8 in) wide, and 3.40 m (11 ft 1+7⁄8 in) high. The first sixteen multiple units and eight ordinary carriages entered active service on the Nord-Süd-Bahn in 1924, after a year of using modified Kleinprofil trains. Designated B-I, the cars were 13.15 m (43 ft 1+3⁄4 in) long and each had three sliding doors; the large elliptical windows at the front of the train earned them the nickname, Tunneleulen (tunnel owls). Upgraded B-II trains were introduced in 1927, and continued to be used until 1969. The first 18-metre-long (59 ft 5⁄8 in) C-I trains were trialled in 1926, and two upgrades were produced before the end of the decade. The first U-Bahn trains to use aluminium in their construction, the C-IV types, were introduced in 1930. Many C-type trains were seized by Soviet forces in 1945, to be used in the Moscow Metro.

The first D-type trains, manufactured in 1957, were built from steel, making them very heavy and less efficient; however, the DL type that followed from 1965 used metals that were less dense, allowing a 26% reduction in weight. In East Berlin, D-type trains bought from the BVG were designated D-I. Difficulties there in trying to develop an E series of trains led, in 1962, to the conversion of S-Bahn type 168 trains for use on the E line. These E-III trains were desperately needed at the time to allow modified Kleinprofil trains to return to the increasingly busy A line but, following reunification, high running costs led to their retirement in 1994.

In West Berlin, the successor to the D-type was the F-type, which debuted in 1973. They varied from other models in having seats that were perpendicular to the sides of the train; from 1980, they also became the first U-Bahn trains to use three-phase electricity. In 1995, the original seating arrangement returned as the H series took up service. H-type trains are characterised by the interconnection of carriages throughout the length of the train; and they can only be removed from the tracks at main service depots.

As of 2005, only F, H, and a variation of the IK-type trains are in active service.

| Großprofil train types | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901–1945 | West Berlin 1945–1990 | East Berlin 1945–1990 | 1990— | |||||||

| 1923–1927 | A-IK | 1955–1965 | D | 1956–1957 | E-I | 1990–1991 | F90 | |||

| 1945–1968 | 1965–1966 | DL65 | 1962–1990 | E-III | 1992–1993 | F92 | ||||

| 1924–1928 | B-I | 1968–1970 | DL68 | 1994–1995 | H95 | |||||

| 1926–1927 | C-I | 1970–1973 | DL70 | 1997–1999 | H97 | |||||

| 1927–1929 | B-II | 1973–1975 | F74 | 2000–2002 | H01 | |||||

| 1929 | C-II | 1976–1978 | F76 | 2017 | IK17 | |||||

| 1930 | C-III | 1979–1981 | F79 | 2020 | IK20 | |||||

| 1930–1931 | C-IV | 1984–1985 | F84 | |||||||

| 1987–1988 | F87 | |||||||||

Depots

Depots of the Berlin U-Bahn fall into one of two classes: main workshops (German: Hauptwerkstätten, abbreviated as Hw); and service workshops (German: Betriebswerkstätten, abbreviated Bw). The main workshops are the only places where trains can be lifted from the tracks; they are used for the full inspections required every few years, and for any major work on trains. The service workshops only handle minor repairs and maintenance, such as replacing windows, or removing graffiti.

As of 2005, the only dedicated Kleinprofil depot is at Grunewald (Hw Gru/Bw Gru), which opened on 21 January 1913. The first Großprofil depot opened at Seestraße (Hw See/Bw See) in 1923, to service the Nord-Süd-Bahn. It has 17 tracks—2 for the main workshop, and 15 for the service workshop—but its inner-city location prevents any further expansion. Due to BVG budget cuts, the Seestraße depot also services Kleinprofil trains. Two further Großprofil service workshops are located at Friedrichsfelde (Bw Fri), and Britz-Süd (Bw Britz).

In the past, there were other workshops. The first opened in 1901 at Warschauer Brücke, and was the construction site for most of the early U-Bahn trains. The division of the U-Bahn network on 13 August 1961 forced its closure, although it was reopened in 1995 as a storage depot. A small depot operated at Krumme Lanke between 22 December 1929 and 1 May 1968; and, while the network was split, East Berlin's U-Bahn used the S-Bahn depot at Schöneweide, along with a small service workshop at Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, which was closed following reunification.

Accidents

The Berlin U-Bahn ranks among the safest modes of transport: its history features few accidents.[citation needed]

The most severe accident occurred at the original Gleisdreieck (rail triangle), where the main and branch lines were connected by switches that allowed the tracks to cross. On 26 September 1908, a train driver missed a stop signal. As a result, two trains collided at the junction, and one fell off the viaduct. The accident killed eighteen people, and severely injured another twenty-one. Gleisdreieck's triangular layout had already been deemed unsuitable for future developments; this incident—and a later, less-serious one—triggered its reconstruction as a multi-level station, starting in 1912.[citation needed]

On 30 June 1965, a train with brake failure stopped on the G line—today's U9—between Zoologischer Garten and Hansaplatz. Unaware of the faulty train, a mechanic working at the Zoologischer Garten signal tower noticed that the signal for the affected section had been set to "Stop" for a long time. Thinking it was a fault of his, after several attempts he manually overrode the signal, in defiance of regulations that strictly prohibited such actions. The following train, which had been waiting at Zoologischer Garten, then left the station on the same track. With emergency brakes unable to prevent the accident, the two trains collided. One passenger was killed in the crash, and 97 were injured. The mechanic was fined 600,000 DM.[citation needed]

Fires can be particularly dangerous and damaging within an underground system. In October 1972, two trains and a 200 m length of tunnel were completely destroyed when the trains caught fire; the reconstructed tunnel is clearly differentiated from the old one. Another train burned out in the connecting tunnel between Klosterstraße and Alexanderplatz in 1987. On 8 July 2000, the last car of a GI/I train suffered a short circuit, burning out at the rear of the Deutsche Oper station. The single exit of the station was unreachable, forcing the passengers to run through the tunnel to reach the next emergency exit. The fire also damaged the station, which remained closed until that September.[citation needed] The Portuguese Ambassador, João Diogo Nunes Barata, presented the BVG with azulejos (tiled paintings), specially designed for the station, by the artist José de Guimarães.[9] Installation of Portugal's gift to the city was completed on 30 October 2002.

As a consequence of the Deutsche Oper incident, BVG decided to post an employee at every station with only one exit until a second exit could be built. Over the following few years, many of those stations—including Britz-Süd, Schillingstraße, Viktoria-Luise-Platz, Uhlandstraße, and Theodor-Heuss-Platz—were retrofitted with additional exits. By June 2008, the only remaining stations with no second exit, Konstanzer Straße and Rudow, had been fitted with second exits.[10] Despite these changes, several passenger organisations—such as Pro Bahn, and IGEB—demand that stations with exits in the middle of the platform are also fitted with additional emergency exits. Many stations are built this way; meeting those demands would place a heavy financial burden on both the BVG and the city.[citation needed]

The U6 saw a particularly costly, though casualty-free, incident on 25 March 2003. Scheduled repair work on the line limited the normal service to between Alt-Mariendorf and Kurt-Schumacher-Platz; one train then shuttled back and forth between Kurt-Schumacher-Platz and Holzhauser Straße, sharing a platform at Kurt-Schumacher-Platz with the normal-service trains departing for their return journey to Alt-Mariendorf. Needing to pass several stop signals on the shuttle service, the driver had been given special instructions how to proceed. Unfortunately, he ignored the signal at the entry to Kurt-Schumacher-Platz, and ploughed into the side of a train heading back to Alt-Mariendorf. The impact wrecked both trains, and caused considerable damage to the tracks. Normal service did not resume for two days, and the removal of the two wrecked trains—which, surprisingly, could still roll along the tracks—also took nearly 48 hours.[citation needed]

Films, music and merchandising

The Berlin U-Bahn has appeared in numerous films and music videos. Offering access to stations, tunnels, and trains, the BVG cooperates with film-makers, although a permit is required.[11]

Whether set in Berlin or elsewhere, the U-Bahn has had at least a minor role in a large number of movies and television programmes, including Emil and the Detectives (2001), Otto – Der Film (1985), Peng! Du bist tot! (1987) featuring Ingolf Lück, Run Lola Run (1998), and several Tatort episodes. The previously unused Reichstag station was used to shoot scenes of the movies Resident Evil and Equilibrium. The U Bahn station Messe was used as coverage in the films Hanna and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 2.[citation needed]

Möbius 17, by Frank Esher Lämmer and Jo Preussler from Berlin, tells the story of an U-Bahn train that, caught in a Möbius strip, travels through alternate universes after a new line is built.

Alexanderplatz station plays an essential role in Berlin Alexanderplatz—a film of thirteen hour-long chapters and one epilogue—produced in 1980 by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, based on the book by Döblin. The film's scenes feature a recreation of the station as it was in 1928—rather darker and dirtier than in the 21st century. In the surrealistic two-hour epilogue, Fassbinder transforms parts of the station into a slaughterhouse where people are killed and dissected.

Since 2001, the Berlin U-Bahn has hosted the annual short-film festival Going Underground. Short films (up to 90 seconds long) are shown on the monitors found in many of the U-Bahn trains.[12] Passengers on board vote for the festival winner.

Sandy Mölling, former singer of the pop band No Angels, shot the video for her single "Unnatural Blonde" in the U-Bahn station Deutsche Oper. Kate Ryan, Overground, Böhse Onkelz, Xavier Naidoo, Die Fantastischen Vier, and the DJ duo Blank & Jones have all used the U-Bahn and its stations for their videos as well.

"Linie 1", a musical performed by Berlin's Grips-Theater, is set completely in stations and trains of the Berlin U-Bahn; a movie version has also been produced.

In 2002, the BVG cooperated with design students in a project to create underwear with an U-Bahn theme, which, in English, they named "Underwear". They used the names of real stations that, in the context of underwear, appeared to be mild sexual double entendres: men's underpants bore labels with Rohrdamm (pipe dam), Onkel Toms Hütte (Uncle Tom's Cabin), and Krumme Lanke (crooked lake); the women's had Gleisdreieck (triangle track), and Jungfernheide (virgin heath). After the first series sold out quickly, several others were commissioned, such as Nothammer (emergency hammer), and Pendelverkehr (shuttle service; though Verkehr also means "intercourse" and Pendel also means "pendulum"). They were withdrawn from sale in 2004.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Berlin underground – The largest underground system in Germany". BVG.de. Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG). Retrieved 2013-09-22.

- ^ a b c "Zahlenspiegel 2017 1. Auflage" [Statistics 2017 1st edition] (PDF) (in German). Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG). December 31, 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ Schomacker, Marcus (2007-03-14). "Berlins U-Bahn-Strecken und Bahnhöfe" (in German). berliner-untergrundbahn.de. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ "Geschäftsbericht 2006 der BVG" [Business Report 2006 for BVG] (pdf) (in German). Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG). May 24, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

- ^ "Pressemitteilung vom 30.08.2005" (in German). BVG. 2005-08-30. Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ^ O2 enables LTE service in Berlin U-Bahn (german)

- ^ Fülling, Thomas (2015-11-07). "Riss im neuen U-Bahn-Tunnel – Unter den Linden wird gesperrt". Berliner Morgenpost (in German). Retrieved 2015-12-05.

- ^ Kurpjuweit, Klaus (January 15, 2014). "Die neue U-Bahn-Zug ist zu dick". tagesspiegel.de (in German). Der Tagesspiegel. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ Brockschmidt, Rolf (2002-10-16). "Leuchtende Grüße aus Lissabon" (in German). Der Tagesspiegel. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ http://www.bvg.de/index.php/en/Bvg/Detail/folder/782/id/200597/name/Second+exit+for+metro+station+Konstanzer+Stra%DFe

- ^ "Filming with the BVG". Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG). Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ^ "Alles über GU (All about Going Underground)" (in German). Going Underground. Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

Bibliography

- Brian Hardy: The Berlin U-Bahn, Capital Transport, 1996, ISBN 1-85414-184-8

- Ulf Buschmann: U-Bahnhöfe Berlin. Berlin Underground Stations. Berlin Story Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86368-027-5

- Jan Gympel: U-Bahn Berlin – Reiseführer. GVE-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89218-072-5

- AG Berliner U-Bahn: Zur Eröffnung der elektrischen Hoch-und Untergrundbahn in Berlin. GVE-Verlag, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-89218-077-6

- Jürgen Meyer-Kronthaler und Klaus Kurpjuweit: Berliner U-Bahn – In Fahrt seit Hundert Jahren. be.bra Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-930863-99-5

- Petra Domke und Markus Hoeft: Tunnel Gräben Viadukte – 100 Jahre Baugeschichte der Berliner U-Bahn. kulturbild Verlag, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-933300-00-2

- Ulrich Lemke und Uwe Poppel: Berliner U-Bahn. alba Verlag, Düsseldorf, ISBN 3-87094-346-7

- Robert Schwandl: Berlin U-Bahn Album. Alle 192 Untergrund- und Hochbahnhöfe in Farbe. Robert Schwandl Verlag, Berlin Juli 2002, ISBN 3-936573-01-8

- Jürgen Meyer-Kronthaler: Berlins U-Bahnhöfe – Die ersten hundert Jahre. be.bra Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-930863-16-2