Devanagari

| Devanagari देवनागरी | |

|---|---|

Devanagari script (vowels top, consonants bottom) in Chandas font. | |

| Script type | |

Time period | Early signs: 1st century CE,[1] modern form: 10th century CE[2][3] |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Region | India and Nepal |

| Languages | Several languages of India and Nepal, including, Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, Pali, Konkani, Bodo, Maithili, Sindhi and Sanskrit. Formerly used to write Punjabi and Gujarati. |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Gujarati Moḍī |

Sister systems | Gurmukhi, Nandinagari |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Deva (315), Devanagari (Nagari) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Devanagari |

| U+0900–U+097F Devanagari, U+A8E0–U+A8FF Devanagari Extended, U+1CD0–U+1CFF Vedic Extensions | |

| Devanāgarī |

|---|

|

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Devanagari (/ˌdeɪvəˈnɑːɡəriː/ DAY-və-NAH-gər-ee; Hindi: [d̪eːʋˈnaːɡri]; देवनागरी devanāgarī a compound of "deva" [देव] and "nāgarī" [नागरी]), also called Nagari (Nāgarī, नागरी),[4] is an abugida (alphasyllabary) alphabet of India and Nepal. It is written from left to right, has a strong preference for symmetrical rounded shapes within squared outlines, and is recognisable by a horizontal line that runs along the top of full letters.[5] In a cursory look, the Devanagari script appears different from other Indic scripts such as Bangla, Oriya or Gurmukhi, but a closer examination reveals they are very similar except for angles and structural emphasis.[5]

The Nagari script has roots in the ancient Brahmi script family.[6] Some of the earliest epigraphical evidence attesting to the developing Sanskrit Nagari script in ancient India, in a form similar to Devanagari, is from the 1st to 4th century CE inscriptions discovered in Gujarat.[1] The Nagari script was in regular use by the 7th century CE and fully it was developed by about the end of first millennium.[4][7] The use of Sanskrit in Nagari script in medieval India is attested by numerous pillar and cave temple inscriptions, including the 11th-century Udayagiri inscriptions in Madhya Pradesh,[8] a brick with inscriptions found in Uttar Pradesh, dated to be from 1217 CE, which is now held at the British Museum.[9] The script's proto- and related versions have been discovered in ancient relics outside of India, such as in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Indonesia; while in East Asia, Siddha Matrika script considered as the closest precursor to Nagari was in use by Buddhists.[10][11] Nagari has been the primus inter pares of the Indic scripts.[10]

The Devanagari script is used for over 120 languages,[12] including Hindi,[13] Marathi, Nepali, Pali, Konkani, Bodo, Sindhi and Maithili among other languages and dialects, making it one of the most used and adopted writing systems in the world.[14] The Devanagari script is also used for classical Sanskrit texts.[12] The Devanagari script is closely related to the Nandinagari script commonly found in numerous ancient manuscripts of South India,[15][16] and it is distantly related to a number of southeast Asian scripts.[12]

Devanagari script has forty-seven primary characters, of which fourteen are vowels and thirty-three are consonants.[10] The ancient Nagari script for Sanskrit had two additional consonantal characters.[10] The script has no capital or small letters as in Latin, and weighs all characters as equal.[17] Generally the orthography of the script reflects the pronunciation of the language.[12]

Origins

Devanagari is part of the Brahmic family of scripts of Nepal, India, Tibet, and South-East Asia.[18] It is a descendant of the Gupta script, along with Siddham and Sharada.[18] Variants of script called Nāgarī, recognizably close to Devanagari, are first attested from the 1st century CE Rudradaman inscriptions in Sanskrit, while the modern standardized form of Devanagari was in use by about 1000 AD.[7][19] Medieval inscriptions suggest widespread diffusion of the Nagari-related scripts, with biscripts presenting local script along with the adoption of Nagari scripts. For example, the mid 8th century Pattadakal pillar in Karnataka has text in both Siddha Matrika script, and an early Telugu-Kannada script; while, the Kangra Jvalamukhi inscription in Himachal Pradesh is written in both Sharada and Devanagari scripts.[20]

The 7th-century Tibetan king Srong-tsan-gambo ordered that all foreign books be transcribed into the Tibetan language. He sent his ambassador Tonmi Sambota to India to acquire alphabet and writing methods; returning with Sanskrit Nagari script from Kashmir corresponding to 24 Tibetan sounds and innovating new symbols for 6 local sounds.[21] Other closely related scripts such as Siddham Matrka was in use in Indonesia, Vietnam, Japan and other parts of East Asia by between 7th- to 10th-century.[22][23] Sharada remained in parallel use in Kashmir. An early version of Devanagari is visible in the Kutila inscription of Bareilly dated to Vikram Samvat 1049 (i.e. 992 CE), which demonstrates the emergence of the horizontal bar to group letters belonging to a word.[2] One of the oldest surviving Sanskrit text from early post-Maurya period available consists of 1,413 Nagari pages of a commentary by Patanjali, with a composition date of about 150 BCE, the surviving copy transcribed about 14th century CE.[24]

Nāgarī is the Sanskrit feminine of Nāgara "relating or belonging to a town or city, urban". It is a phrasing with lipi ("script") as nāgarī lipi "script relating to a city", or "spoken in city".[25]

The use of the name devanāgarī is relatively recent, and the older term nāgarī is still common.[18] The rapid spread of the term devanāgarī may be related to the almost exclusive use of this script to publish Sanskrit texts in print since the 1870s.[18]

Principle

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2015) |

As a Brahmic abugida, the fundamental principle of Devanagari is that each letter represents a consonant, which carries an inherent schwa vowel. This is usually written in Latin as a, though it is represented as [ə] in the International Phonetic Alphabet.[26] The letter क is read ka, the two letters कन are kana, the three कनय are kanaya, etc. Other vowels, or the absence of vowels, require modification of these consonants or their own letters:

- A final consonant is marked with the diacritic ्, called the virāma in Sanskrit, halant in Hindi, and occasionally a "killer stroke" in English. This cancels the inherent vowel, so that from क्नय knaya is derived क्नय् knay. The halant is often used for consonant clusters when typesetting conjunct ligatures is not feasible.

- Consonant clusters are written with ligatures (saṃyuktākṣara "conjuncts"). For example, the three consonants क्, न्, and य्, (k, n, y), when written consecutively without virāma form कनय, as shown above. Alternatively, they may be joined as clusters to form क्नय knaya, कन्य kanya, or क्न्य knya. This system was originally created for use with the Middle Indo-Aryan languages, which have a very limited number of clusters (the only clusters allowed are geminate consonants and clusters involving homorganic nasal stops). When applied to Sanskrit, however, it added a great deal of complexity to the script, due to the large variety of clusters in this language (up to five consonants, e.g. rtsny). Much of this complexity is required at least on occasion in the modern Indo-Aryan languages, due to the large number of clusters allowed and especially due to borrowings from Sanskrit.

- Vowels other than the inherent a are written with diacritics (termed matras). For example, using क ka, the following forms can be derived: के ke, कु ku, की kī, का kā, etc.

- For vowels as an independent syllable (in writing, unattached to a preceding consonant), either at the beginning of a word or (in Hindi) after another vowel, there are full-letter forms. For example, while the vowel ū is written with the diacritic ू in कू kū, it has its own letter ऊ in ऊक ūka and (in Hindi but not Sanskrit) कऊ kaū.

Such a letter or ligature, with its diacritics, is called an akṣara "syllable". For example, कनय kanaya is written with what are counted as three akshara, whereas क्न्य knya and कु ku are each written with one.

When handwriting, letters are usually written without the distinctive horizontal bar, which is added only once the word is completed.[27]

Letters

The letter order of Devanagari, like nearly all Brahmic scripts, is based on phonetic principles that consider both the manner and place of articulation of the consonants and vowels they represent. This arrangement is usually referred to as the varṇamālā "garland of letters".[28] The format of Devanagari for Sanskrit serves as the prototype for its application, with minor variations or additions, to other languages.[29]

Vowels

The vowels and their arrangement are:[30]

| Independent form | Romanised | As diacritic with प | Independent form | Romanised | As diacritic with प | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

अ | a | प | आ | ā | पा | |

| tālavya (Palatal) |

इ | i | पि | ई | ī | पी | |

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

उ | u | पु | ऊ | ū | पू | |

| mūrdhanya (Retroflex) |

ऋ | ṛ | पृ | ॠ | ṝ | पॄ | |

| dantya (Dental) |

ऌ | ḷ | पॢ | ॡ | ḹ | पॣ | |

| kaṇṭhatālavya (Palatoguttural) |

ए | e | पे | ऐ | ai | पै | |

| kaṇṭhoṣṭhya (Labioguttural) |

ओ | o | पो | औ | au | पौ | |

| IAST | अं | aṃ | पं | अः | aḥ | पः |

- Arranged with the vowels are two consonantal diacritics, the final nasal anusvāra ं ṃ and the final fricative visarga ः ḥ (called अं aṃ and अः aḥ). Masica (1991:146) notes of the anusvāra in Sanskrit that "there is some controversy as to whether it represents a homorganic nasal stop [...], a nasalised vowel, a nasalised semivowel, or all these according to context". The visarga represents post-vocalic voiceless glottal fricative [h], in Sanskrit an allophone of s, or less commonly r, usually in word-final position. Some traditions of recitation append an echo of the vowel after the breath:[31] इः [ihi]. Masica (1991:146) considers the visarga along with letters ङ ṅa and ञ ña for the "largely predictable" velar and palatal nasals to be examples of "phonetic overkill in the system".

- Another diacritic is the candrabindu/anunāsika ँ अँ. Salomon (2003:76–77) describes it as a "more emphatic form" of the anusvāra, "sometimes [...] used to mark a true [vowel] nasalization". In a New Indo-Aryan language such as Hindi the distinction is formal: the candrabindu indicates vowel nasalisation[32] while the anusvār indicates a homorganic nasal preceding another consonant:[33] e.g. हँसी [ɦə̃si] "laughter", गंगा [ɡəŋɡɑ] "the Ganges". When an akshara has a vowel diacritic above the top line, that leaves no room for the candra ("moon") stroke candrabindu, which is dispensed with in favour of the lone dot:[34] हूँ [ɦũ] "am", but हैं [ɦɛ̃] "are". Some writers and typesetters dispense with the "moon" stroke altogether, using only the dot in all situations.[35]

- The avagraha ऽ अऽ (usually transliterated with an apostrophe) is a Sanskrit punctuation mark for the elision of a vowel in sandhi: एकोऽयम् eko'yam ( ← ekas + ayam) "this one". An original long vowel lost to coalescence is sometimes marked with a double avagraha: सदाऽऽत्मा sadā'tmā ( ← sadā + ātmā) "always, the self".[36] In Hindi, Snell (2000:77) states that its "main function is to show that a vowel is sustained in a cry or a shout": आईऽऽऽ! āīīī!. In Madhyadeshi Languages like Bhojpuri, Awadhi, Maithili, etc. which have "quite a number of verbal forms [that] end in that inherent vowel",[37] the avagraha is used to mark the non-elision of word-final inherent a, which otherwise is a modern orthographic convention: बइठऽ baiṭha "sit" versus *बइठ baiṭh

- The syllabic consonants ṝ, ḷ, and ḹ are specific to Sanskrit and not included in the varṇamālā of other languages. The sound represented by ṛ has also been lost in the modern languages, and its pronunciation now ranges from [ɾɪ] (Hindi) to [ɾu] (Marathi).

- ḹ is not an actual phoneme of Sanskrit, but rather a graphic convention included among the vowels in order to maintain the symmetry of short–long pairs of letters.[29]

- There are non-regular formations of रु ru and रू rū.

Consonants

The table below shows the consonant letters (in combination with inherent vowel a) and their arrangement. To the right of the Devanagari letter it shows the scientific transcription (IAST), and the phonetic value (IPA).[38]

| sparśa (Plosive) |

anunāsika (Nasal) |

antastha (Approximant) |

ūṣma/saṃghaṣhrī (Fricative) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | ||||||||||

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

क | ka /k/ |

ख | kha /kʰ/ |

ग | ga /ɡ/ |

घ | gha /ɡʱ/ |

ङ | ṅa /ŋ/ |

ह | ha /ɦ/ | ||||

| tālavya (Palatal) |

च | ca /c, t͡ʃ/ |

छ | cha /cʰ, t͡ʃʰ/ |

ज | ja /ɟ, d͡ʒ/ |

झ | jha /ɟʱ, d͡ʒʱ/ |

ञ | ña /ɲ/ |

य | ya /j/ |

श | śa /ɕ, ʃ/ |

||

| mūrdhanya (Retroflex) |

ट | ṭa /ʈ/ |

ठ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ |

ड | ḍa /ɖ/ |

ढ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ |

ण | ṇa /ɳ/ |

र | ra /r/ |

ष | ṣa /ʂ/ | ||

| dantya (Dental) |

त | ta /t̪/ |

थ | tha /t̪ʰ/ |

द | da /d̪/ |

ध | dha /d̪ʱ/ |

न | na /n/ |

ल | la /l/ |

स | sa /s/ | ||

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

प | pa /p/ |

फ | pha /pʰ/ |

ब | ba /b/ |

भ | bha /bʱ/ |

म | ma /m/ |

व | va /w, ʋ/ |

||||

- Rounding this out where applicable is ळ ḷa /Retroflex lateral flap / (also /ɭ̆/ in IPA), the intervocalic lateral flap allophone of the voiced retroflex stop in Vedic Sanskrit, which is a phoneme in languages such as Marathi, Konkani, and Rajasthani.[39]

- Beyond the Sanskritic set, new shapes have rarely been formulated. Masica (1991:146) offers the following, "In any case, according to some, all possible sounds had already been described and provided for in this system, as Sanskrit was the original and perfect language. Hence it was difficult to provide for or even to conceive other sounds, unknown to the phoneticians of Sanskrit". Where foreign borrowings and internal developments did inevitably accrue and arise in New Indo-Aryan languages, they have been ignored in writing, or dealt through means such as diacritics and ligatures (ignored in recitation).

- The most prolific diacritic has been the subscript dot (nuqtā) ़. Hindi uses it for the Persian, Arabic and English sounds क़ qa /qä/, ख़ xa /xä/, ग़ ġa /ɣä/, ज़ za /zä/, श़ or झ़ zha /ʒä/, and फ़ fa /fä/, and for the allophonic developments ड़ ṛa /ɽä/ and ढ़ ṛha /ɽʱä/. (Although ऴ ḷha /ɭʱä/ could also exist there is no use of it in Hindi.)

- Sindhi's and Saraiki's implosives are accommodated with a line attached below: ॻ [ɠə], ॼ [ʄə], ॾ [ɗə], ॿ [ɓə].

- Aspirated sonorants may be represented as conjuncts/ligatures with ह ha: म्ह mha, न्ह nha, ण्ह ṇha, व्ह vha, ल्ह lha, ळ्ह ḷha, र्ह rha.

- Masica (1991:147) notes Marwari as using ॸ for ḍa [ɗə] (while ड represents [ɽə]).

For a list of the 297 (33×9) possible Sanskrit consonant-(short) vowel phonemes, see Āryabhaṭa numeration.

Schwa syncope in consonants

In many Indo-Aryan languages, the schwa ('ə') implicit in each consonant of the script is "obligatorily deleted" at the end of words and in certain other contexts,[40] unlike in Marathi[citation needed] or Sanskrit. This phenomenon has been termed the "schwa syncope rule" or the "schwa deletion rule" of Hindi.[40][41] One formalisation of this rule has been summarised as ə → ∅ | VC_CV. In other words, when a schwa-succeeded consonant is followed by a vowel-succeeded consonant, the schwa inherent in the first consonant is deleted.[41][42] However, this formalisation is inexact and incomplete (it sometimes deletes a schwa when it should not and, at other times, it fails to delete it when it should) and can cause errors. Schwa deletion is computationally important because it is essential to building text-to-speech software for Hindi.[42][43]

As a result of schwa syncope, the Hindi pronunciation of many words differs from that expected from a literal Sanskrit-style rendering of Devanagari. For instance, राम is rām (not rāma), रचना is racnā (not racanā), वेद is vēd (not vēda) and नमकीन is namkīn (not namakīna).[42][43] The name of the script itself is pronounced devnāgrī (not devanāgarī).[44]

Correct schwa deletion is also critical because, in some cases, the same Devanagari letter sequence is pronounced two different ways in Hindi depending on context, and failure to delete the appropriate schwas can change the sense of the word.[45] For instance, the letter sequence 'रक' is pronounced differently in हरकत (harkat, meaning movement or activity) and सरकना (saraknā, meaning to slide). Similarly, the sequence धड़कने in दिल धड़कने लगा (the heart started beating) and in दिल की धड़कनें (beats of the heart) is identical prior to the nasalisation in the second usage. Yet, it is pronounced dhaṛaknē in the first and dhaṛkanē in the second.[45] While native speakers correctly pronounce the sequences differently in different contexts, non-native speakers and voice-synthesis software can make them "sound very unnatural", making it "extremely difficult for the listener" to grasp the intended meaning.[45]

Allophony of 'v' and 'w' in Hindi

[v] (the voiced labiodental fricative) and [w] (the voiced labio-velar approximant) are both allophones of the single phoneme represented by the letter 'व' in Hindi Devanagari. More specifically, they are conditional allophones, i.e. rules apply on whether 'व' is pronounced as [v] or [w] depending on context. Native Hindi speakers pronounce 'व' as [v] in vrat (व्रत, fast) and [w] in pakvān (पकवान, food dish), perceiving them as a single phoneme and without being aware of the allophone distinctions they are systematically making.[46] However, this specific allophony can become obvious when speakers switch languages. Non-native speakers of Hindi might pronounce 'व' in 'व्रत' as [w], i.e. as wrat instead of the more correct vrat. This results in a minor intelligibility problem because wrat can easily be confused for aurat,[citation needed] which means woman, instead of the intended fast (abstaining from food), in Hindi.[46]

Conjuncts

- You will be able to see the ligatures only if your system has a Unicode font installed that includes the required ligature glyphs (such as one of the TDIL[47] fonts, see "external links" below).

As mentioned, successive consonants lacking a vowel in between them may physically join together as a conjunct or ligature. Conjuncts are used mostly with loan words. Native words typically use the basic consonant and native speakers know to suppress the vowel. For example, the native Hindi word karnā is written करना (ka-ra-nā).[48] The government of these clusters ranges from widely to narrowly applicable rules, with special exceptions within. While standardised for the most part, there are certain variations in clustering, of which the Unicode used on this page is just one scheme. The following are a number of rules:

- 24 out of the 36 consonants contain a vertical right stroke (ख, घ, ण etc.). As first or middle fragments/members of a cluster, they lose that stroke. e.g. त + व = त्व tva, ण + ढ = ण्ढ ṇḍha, स + थ = स्थ stha. In Unicode, these consonants without their vertical stems are called half forms.[49] श ś(a) appears as a different, simple ribbon-shaped fragment preceding व va, न na, च ca, ल la, and र ra, causing these second members to be shifted down and reduced in size. Thus श्व śva, श्न śna, श्च śca श्ल śla, and श्र śra.

- र r(a) as a first member takes the form of a curved upward dash above the final character or its ā-diacritic. e.g. र्व rva, र्वा rvā, र्स्प rspa, र्स्पा rspā. As a final member with ट ठ ड ढ ङ छ it is two lines below the character, pointed downwards and apart. Thus ट्र ठ्र ड्र ढ्र ङ्र छ्र. Elsewhere as a final member it is a diagonal stroke extending leftwards and down. e.g. क्र ग्र भ्र. त ta is shifted up to make त्र tra.

- As first members, remaining characters lacking vertical strokes such as द d(a) and ह h(a) may have their second member, reduced in size and lacking its horizontal stroke, placed underneath. क k(a), छ ch(a), and फ ph(a) shorten their right hooks and join them directly to the following member.

- The conjuncts for kṣ and jñ are not clearly derived from the letters making up their components. The conjunct for kṣ is क्ष (क् + ष) and for jñ it is ज्ञ (ज् + ञ).

The table below shows all the 1296 viable symbols for the biconsonantal clusters formed by collating the 36 fundamental symbols of Sanskrit as listed in Masica (1991:161–162). Scroll your cursor over the conjuncts to reveal their romanizations (in ISO 15919[50]) and IPA transcriptions. Note that not all these conjuncts appear in genuine words.

Biconsonantal conjuncts

| ka (IPA:kə) | kha (IPA:kʰə) | ga (IPA:ɡə) | gha (IPA:ɡʱə) | ṅa (IPA:ŋə) | ca (IPA:cɕə) | cha (IPA:cɕʰə) | ja (IPA:ɟʝə) | jha (IPA:ɟʝʱə) | ña (IPA:ɲə) | ṭa (IPA:ʈə) | ṭha (IPA:ʈʰə) | ḍa (IPA:ɖə) | ḍha (IPA:ɖʱə) | ṇa (IPA:ɳə) | ta (IPA:t̪ə) | tha (IPA:t̪ʰə) | da (IPA:d̪ə) | dha (IPA:d̪ʱə) | na (IPA:n̪ə) | pa (IPA:pə) | pha (IPA:pʰə) | ba (IPA:bə) | bha (IPA:bʱə) | ma (IPA:mə) | ya (IPA:jə) | ra (IPA:rə) | la (IPA:lə) | va (IPA:və) | śa (IPA:ʃə) | ṣa (IPA:ʂə) | sa (IPA:sə) | ha (IPA:hə) | ḷa (IPA:ɭə) | kṣa (IPA:kʂə) | jña (IPA:ɟʝɲə) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k (IPA:k) | kka (IPA:kkə) | kkha (IPA:kkʰə) | kga (IPA:kɡə) | kgha (IPA:kɡʱə) | kṅa (IPA:kŋə) | kca (IPA:kcɕə) | kcha (IPA:kcɕʰə) | kja (IPA:kɟʝə) | kjha (IPA:kɟʝʱə) | kña (IPA:kɲə) | kṭa (IPA:kʈə) | kṭha (IPA:kʈʰə) | kḍa (IPA:kɖə) | kḍha (IPA:kɖʱə) | kṇa (IPA:kɳə) | kta (IPA:kt̪ə) | ktha (IPA:kt̪ʰə) | kda (IPA:kd̪ə) | kdha (IPA:kd̪ʱə) | kna (IPA:kn̪ə) | kpa (IPA:kpə) | kpha (IPA:kpʰə) | kba (IPA:kbə) | kbha (IPA:kbʱə) | kma (IPA:kmə) | kya (IPA:kjə) | kra (IPA:krə) | kla (IPA:klə) | kva (IPA:kvə) | kśa (IPA:kʃə) | kṣa (IPA:kʂə) | ksa (IPA:ksə) | kha (IPA:khə) | kḷa (IPA:kɭə) | kkṣa (IPA:kkʂə) | kjña (IPA:kɟʝɲə) |

| kh (IPA:kʰ) | khka (IPA:kʰkə) | khkha (IPA:kʰkʰə) | khga (IPA:kʰɡə) | khgha (IPA:kʰɡʱə) | khṅa (IPA:kʰŋə) | khca (IPA:kʰcɕə) | khcha (IPA:kʰcɕʰə) | khja (IPA:kʰɟʝə) | khjha (IPA:kʰɟʝʱə) | khña (IPA:kʰɲə) | khṭa (IPA:kʰʈə) | khṭha (IPA:kʰʈʰə) | khḍa (IPA:kʰɖə) | khḍha (IPA:kʰɖʱə) | khṇa (IPA:kʰɳə) | khta (IPA:kʰt̪ə) | khtha (IPA:kʰt̪ʰə) | khda (IPA:kʰd̪ə) | khdha (IPA:kʰd̪ʱə) | khna (IPA:kʰn̪ə) | khpa (IPA:kʰpə) | khpha (IPA:kʰpʰə) | khba (IPA:kʰbə) | khbha (IPA:kʰbʱə) | khma (IPA:kʰmə) | khya (IPA:kʰjə) | khra (IPA:kʰrə) | khla (IPA:kʰlə) | khva (IPA:kʰvə) | khśa (IPA:kʰʃə) | khṣa (IPA:kʰʂə) | khsa (IPA:kʰsə) | khha (IPA:kʰhə) | khḷa (IPA:kʰɭə) | khkṣa (IPA:kʰkʂə) | khjña (IPA:kʰɟʝɲə) |

| g (IPA:ɡ) | gka (IPA:ɡkə) | gkha (IPA:ɡkʰə) | gga (IPA:ɡɡə) | ggha (IPA:ɡɡʱə) | gṅa (IPA:ɡŋə) | gca (IPA:ɡcɕə) | gcha (IPA:ɡcɕʰə) | gja (IPA:ɡɟʝə) | gjha (IPA:ɡɟʝʱə) | gña (IPA:ɡɲə) | gṭa (IPA:ɡʈə) | gṭha (IPA:ɡʈʰə) | gḍa (IPA:ɡɖə) | gḍha (IPA:ɡɖʱə) | gṇa (IPA:ɡɳə) | gta (IPA:ɡt̪ə) | gtha (IPA:ɡt̪ʰə) | gda (IPA:ɡd̪ə) | gdha (IPA:ɡd̪ʱə) | gna (IPA:ɡn̪ə) | gpa (IPA:ɡpə) | gpha (IPA:ɡpʰə) | gba (IPA:ɡbə) | gbha (IPA:ɡbʱə) | gma (IPA:ɡmə) | gya (IPA:ɡjə) | gra (IPA:ɡrə) | gla (IPA:ɡlə) | gva (IPA:ɡvə) | gśa (IPA:ɡʃə) | gṣa (IPA:ɡʂə) | gsa (IPA:ɡsə) | gha (IPA:ɡhə) | gḷa (IPA:ɡɭə) | gkṣa (IPA:ɡkʂə) | gjña (IPA:ɡɟʝɲə) |

| gh (IPA:ɡʱ) | ghka (IPA:ɡʱkə) | ghkha (IPA:ɡʱkʰə) | ghga (IPA:ɡʱɡə) | ghgha (IPA:ɡʱɡʱə) | ghṅa (IPA:ɡʱŋə) | ghca (IPA:ɡʱcɕə) | ghcha (IPA:ɡʱcɕʰə) | ghja (IPA:ɡʱɟʝə) | ghjha (IPA:ɡʱɟʝʱə) | ghña (IPA:ɡʱɲə) | ghṭa (IPA:ɡʱʈə) | ghṭha (IPA:ɡʱʈʰə) | ghḍa (IPA:ɡʱɖə) | ghḍha (IPA:ɡʱɖʱə) | ghṇa (IPA:ɡʱɳə) | ghta (IPA:ɡʱt̪ə) | ghtha (IPA:ɡʱt̪ʰə) | ghda (IPA:ɡʱd̪ə) | ghdha (IPA:ɡʱd̪ʱə) | ghna (IPA:ɡʱn̪ə) | ghpa (IPA:ɡʱpə) | ghpha (IPA:ɡʱpʰə) | ghba (IPA:ɡʱbə) | ghbha (IPA:ɡʱbʱə) | ghma (IPA:ɡʱmə) | ghya (IPA:ɡʱjə) | ghra (IPA:ɡʱrə) | ghla (IPA:ɡʱlə) | ghva (IPA:ɡʱvə) | ghśa (IPA:ɡʱʃə) | ghṣa (IPA:ɡʱʂə) | ghsa (IPA:ɡʱsə) | ghha (IPA:ɡʱhə) | ghḷa (IPA:ɡʱɭə) | ghkṣa (IPA:ɡʱkʂə) | ghjña (IPA:ɡʱɟʝɲə) |

| ṅ (IPA:ŋ) | ṅka (IPA:ŋkə) | ṅkha (IPA:ŋkʰə) | ṅga (IPA:ŋɡə) | ṅgha (IPA:ŋɡʱə) | ṅṅa (IPA:ŋŋə) | ṅca (IPA:ŋcɕə) | ṅcha (IPA:ŋcɕʰə) | ṅja (IPA:ŋɟʝə) | ṅjha (IPA:ŋɟʝʱə) | ṅña (IPA:ŋɲə) | ṅṭa (IPA:ŋʈə) | ṅṭha (IPA:ŋʈʰə) | ṅḍa (IPA:ŋɖə) | ṅḍha (IPA:ŋɖʱə) | ṅṇa (IPA:ŋɳə) | ṅta (IPA:ŋt̪ə) | ṅtha (IPA:ŋt̪ʰə) | ṅda (IPA:ŋd̪ə) | ṅdha (IPA:ŋd̪ʱə) | ṅna (IPA:ŋn̪ə) | ṅpa (IPA:ŋpə) | ṅpha (IPA:ŋpʰə) | ṅba (IPA:ŋbə) | ṅbha (IPA:ŋbʱə) | ṅma (IPA:ŋmə) | ṅya (IPA:ŋjə) | ṅra (IPA:ŋrə) | ṅla (IPA:ŋlə) | ṅva (IPA:ŋvə) | ṅśa (IPA:ŋʃə) | ṅṣa (IPA:ŋʂə) | ṅsa (IPA:ŋsə) | ṅha (IPA:ŋhə) | ṅḷa (IPA:ŋɭə) | ṅkṣa (IPA:ŋkʂə) | ṅjña (IPA:ŋɟʝɲə) |

| c (IPA:cɕ) | cka (IPA:cɕkə) | ckha (IPA:cɕkʰə) | cga (IPA:cɕɡə) | cgha (IPA:cɕɡʱə) | cṅa (IPA:cɕŋə) | cca (IPA:cɕcɕə) | ccha (IPA:cɕcɕʰə) | cja (IPA:cɕɟʝə) | cjha (IPA:cɕɟʝʱə) | cña (IPA:cɕɲə) | cṭa (IPA:cɕʈə) | cṭha (IPA:cɕʈʰə) | cḍa (IPA:cɕɖə) | cḍha (IPA:cɕɖʱə) | cṇa (IPA:cɕɳə) | cta (IPA:cɕt̪ə) | ctha (IPA:cɕt̪ʰə) | cda (IPA:cɕd̪ə) | cdha (IPA:cɕd̪ʱə) | cna (IPA:cɕn̪ə) | cpa (IPA:cɕpə) | cpha (IPA:cɕpʰə) | cba (IPA:cɕbə) | cbha (IPA:cɕbʱə) | cma (IPA:cɕmə) | cya (IPA:cɕjə) | cra (IPA:cɕrə) | cla (IPA:cɕlə) | cva (IPA:cɕvə) | cśa (IPA:cɕʃə) | cṣa (IPA:cɕʂə) | csa (IPA:cɕsə) | cha (IPA:cɕhə) | cḷa (IPA:cɕɭə) | ckṣa (IPA:cɕkʂə) | cjña (IPA:cɕɟʝɲə) |

| ch (IPA:cɕʰ) | chka (IPA:cɕʰkə) | chkha (IPA:cɕʰkʰə) | chga (IPA:cɕʰɡə) | chgha (IPA:cɕʰɡʱə) | chṅa (IPA:cɕʰŋə) | chca (IPA:cɕʰcɕə) | chcha (IPA:cɕʰcɕʰə) | chja (IPA:cɕʰɟʝə) | chjha (IPA:cɕʰɟʝʱə) | chña (IPA:cɕʰɲə) | chṭa (IPA:cɕʰʈə) | chṭha (IPA:cɕʰʈʰə) | chḍa (IPA:cɕʰɖə) | chḍha (IPA:cɕʰɖʱə) | chṇa (IPA:cɕʰɳə) | chta (IPA:cɕʰt̪ə) | chtha (IPA:cɕʰt̪ʰə) | chda (IPA:cɕʰd̪ə) | chdha (IPA:cɕʰd̪ʱə) | chna (IPA:cɕʰn̪ə) | chpa (IPA:cɕʰpə) | chpha (IPA:cɕʰpʰə) | chba (IPA:cɕʰbə) | chbha (IPA:cɕʰbʱə) | chma (IPA:cɕʰmə) | chya (IPA:cɕʰjə) | chra (IPA:cɕʰrə) | chla (IPA:cɕʰlə) | chva (IPA:cɕʰvə) | chśa (IPA:cɕʰʃə) | chṣa (IPA:cɕʰʂə) | chsa (IPA:cɕʰsə) | chha (IPA:cɕʰhə) | chḷa (IPA:cɕʰɭə) | chkṣa (IPA:cɕʰkʂə) | chjña (IPA:cɕʰɟʝɲə) |

| j (IPA:ɟʝ) | jka (IPA:ɟʝkə) | jkha (IPA:ɟʝkʰə) | jga (IPA:ɟʝɡə) | jgha (IPA:ɟʝɡʱə) | jṅa (IPA:ɟʝŋə) | jca (IPA:ɟʝcɕə) | jcha (IPA:ɟʝcɕʰə) | jja (IPA:ɟʝɟʝə) | jjha (IPA:ɟʝɟʝʱə) | jña (IPA:ɟʝɲə) | jṭa (IPA:ɟʝʈə) | jṭha (IPA:ɟʝʈʰə) | jḍa (IPA:ɟʝɖə) | jḍha (IPA:ɟʝɖʱə) | jṇa (IPA:ɟʝɳə) | jta (IPA:ɟʝt̪ə) | jtha (IPA:ɟʝt̪ʰə) | jda (IPA:ɟʝd̪ə) | jdha (IPA:ɟʝd̪ʱə) | jna (IPA:ɟʝn̪ə) | jpa (IPA:ɟʝpə) | jpha (IPA:ɟʝpʰə) | jba (IPA:ɟʝbə) | jbha (IPA:ɟʝbʱə) | jma (IPA:ɟʝmə) | jya (IPA:ɟʝjə) | jra (IPA:ɟʝrə) | jla (IPA:ɟʝlə) | jva (IPA:ɟʝvə) | jśa (IPA:ɟʝʃə) | jṣa (IPA:ɟʝʂə) | jsa (IPA:ɟʝsə) | jha (IPA:ɟʝhə) | jḷa (IPA:ɟʝɭə) | jkṣa (IPA:ɟʝkʂə) | jjña (IPA:ɟʝɟʝɲə) |

| jh (IPA:ɟʝʱ) | jhka (IPA:ɟʝʱkə) | jhkha (IPA:ɟʝʱkʰə) | jhga (IPA:ɟʝʱɡə) | jhgha (IPA:ɟʝʱɡʱə) | jhṅa (IPA:ɟʝʱŋə) | jhca (IPA:ɟʝʱcɕə) | jhcha (IPA:ɟʝʱcɕʰə) | jhja (IPA:ɟʝʱɟʝə) | jhjha (IPA:ɟʝʱɟʝʱə) | jhña (IPA:ɟʝʱɲə) | jhṭa (IPA:ɟʝʱʈə) | jhṭha (IPA:ɟʝʱʈʰə) | jhḍa (IPA:ɟʝʱɖə) | jhḍha (IPA:ɟʝʱɖʱə) | jhṇa (IPA:ɟʝʱɳə) | jhta (IPA:ɟʝʱt̪ə) | jhtha (IPA:ɟʝʱt̪ʰə) | jhda (IPA:ɟʝʱd̪ə) | jhdha (IPA:ɟʝʱd̪ʱə) | jhna (IPA:ɟʝʱn̪ə) | jhpa (IPA:ɟʝʱpə) | jhpha (IPA:ɟʝʱpʰə) | jhba (IPA:ɟʝʱbə) | jhbha (IPA:ɟʝʱbʱə) | jhma (IPA:ɟʝʱmə) | jhya (IPA:ɟʝʱjə) | jhra (IPA:ɟʝʱrə) | jhla (IPA:ɟʝʱlə) | jhva (IPA:ɟʝʱvə) | jhśa (IPA:ɟʝʱʃə) | jhṣa (IPA:ɟʝʱʂə) | jhsa (IPA:ɟʝʱsə) | jhha (IPA:ɟʝʱhə) | jhḷa (IPA:ɟʝʱɭə) | jhkṣa (IPA:ɟʝʱkʂə) | jhjña (IPA:ɟʝʱɟʝɲə) |

| ñ (IPA:ɲ) | ñka (IPA:ɲkə) | ñkha (IPA:ɲkʰə) | ñga (IPA:ɲɡə) | ñgha (IPA:ɲɡʱə) | ñṅa (IPA:ɲŋə) | ñca (IPA:ɲcɕə) | ñcha (IPA:ɲcɕʰə) | ñja (IPA:ɲɟʝə) | ñjha (IPA:ɲɟʝʱə) | ñña (IPA:ɲɲə) | ñṭa (IPA:ɲʈə) | ñṭha (IPA:ɲʈʰə) | ñḍa (IPA:ɲɖə) | ñḍha (IPA:ɲɖʱə) | ñṇa (IPA:ɲɳə) | ñta (IPA:ɲt̪ə) | ñtha (IPA:ɲt̪ʰə) | ñda (IPA:ɲd̪ə) | ñdha (IPA:ɲd̪ʱə) | ñna (IPA:ɲn̪ə) | ñpa (IPA:ɲpə) | ñpha (IPA:ɲpʰə) | ñba (IPA:ɲbə) | ñbha (IPA:ɲbʱə) | ñma (IPA:ɲmə) | ñya (IPA:ɲjə) | ñra (IPA:ɲrə) | ñla (IPA:ɲlə) | ñva (IPA:ɲvə) | ñśa (IPA:ɲʃə) | ñṣa (IPA:ɲʂə) | ñsa (IPA:ɲsə) | ñha (IPA:ɲhə) | ñḷa (IPA:ɲɭə) | ñkṣa (IPA:ɲkʂə) | ñjña (IPA:ɲɟʝɲə) |

| ṭ (IPA:ʈ) | ṭka (IPA:ʈkə) | ṭkha (IPA:ʈkʰə) | ṭga (IPA:ʈɡə) | ṭgha (IPA:ʈɡʱə) | ṭṅa (IPA:ʈŋə) | ṭca (IPA:ʈcɕə) | ṭcha (IPA:ʈcɕʰə) | ṭja (IPA:ʈɟʝə) | ṭjha (IPA:ʈɟʝʱə) | ṭña (IPA:ʈɲə) | ṭṭa (IPA:ʈʈə) | ṭṭha (IPA:ʈʈʰə) | ṭḍa (IPA:ʈɖə) | ṭḍha (IPA:ʈɖʱə) | ṭṇa (IPA:ʈɳə) | ṭta (IPA:ʈt̪ə) | ṭtha (IPA:ʈt̪ʰə) | ṭda (IPA:ʈd̪ə) | ṭdha (IPA:ʈd̪ʱə) | ṭna (IPA:ʈn̪ə) | ṭpa (IPA:ʈpə) | ṭpha (IPA:ʈpʰə) | ṭba (IPA:ʈbə) | ṭbha (IPA:ʈbʱə) | ṭma (IPA:ʈmə) | ṭya (IPA:ʈjə) | ṭra (IPA:ʈrə) | ṭla (IPA:ʈlə) | ṭva (IPA:ʈvə) | ṭśa (IPA:ʈʃə) | ṭṣa (IPA:ʈʂə) | ṭsa (IPA:ʈsə) | ṭha (IPA:ʈhə) | ṭḷa (IPA:ʈɭə) | ṭkṣa (IPA:ʈkʂə) | ṭjña (IPA:ʈɟʝɲə) |

| ṭh (IPA:ʈʰ) | ṭhka (IPA:ʈʰkə) | ṭhkha (IPA:ʈʰkʰə) | ṭhga (IPA:ʈʰɡə) | ṭhgha (IPA:ʈʰɡʱə) | ṭhṅa (IPA:ʈʰŋə) | ṭhca (IPA:ʈʰcɕə) | ṭhcha (IPA:ʈʰcɕʰə) | ṭhja (IPA:ʈʰɟʝə) | ṭhjha (IPA:ʈʰɟʝʱə) | ṭhña (IPA:ʈʰɲə) | ṭhṭa (IPA:ʈʰʈə) | ṭhṭha (IPA:ʈʰʈʰə) | ṭhḍa (IPA:ʈʰɖə) | ṭhḍha (IPA:ʈʰɖʱə) | ṭhṇa (IPA:ʈʰɳə) | ṭhta (IPA:ʈʰt̪ə) | ṭhtha (IPA:ʈʰt̪ʰə) | ṭhda (IPA:ʈʰd̪ə) | ṭhdha (IPA:ʈʰd̪ʱə) | ṭhna (IPA:ʈʰn̪ə) | ṭhpa (IPA:ʈʰpə) | ṭhpha (IPA:ʈʰpʰə) | ṭhba (IPA:ʈʰbə) | ṭhbha (IPA:ʈʰbʱə) | ṭhma (IPA:ʈʰmə) | ṭhya (IPA:ʈʰjə) | ṭhra (IPA:ʈʰrə) | ṭhla (IPA:ʈʰlə) | ṭhva (IPA:ʈʰvə) | ṭhśa (IPA:ʈʰʃə) | ṭhṣa (IPA:ʈʰʂə) | ṭhsa (IPA:ʈʰsə) | ṭhha (IPA:ʈʰhə) | ṭhḷa (IPA:ʈʰɭə) | ṭhkṣa (IPA:ʈʰkʂə) | ṭhjña (IPA:ʈʰɟʝɲə) |

| ḍ (IPA:ɖ) | ḍka (IPA:ɖkə) | ḍkha (IPA:ɖkʰə) | ḍga (IPA:ɖɡə) | ḍgha (IPA:ɖɡʱə) | ḍṅa (IPA:ɖŋə) | ḍca (IPA:ɖcɕə) | ḍcha (IPA:ɖcɕʰə) | ḍja (IPA:ɖɟʝə) | ḍjha (IPA:ɖɟʝʱə) | ḍña (IPA:ɖɲə) | ḍṭa (IPA:ɖʈə) | ḍṭha (IPA:ɖʈʰə) | ḍḍa (IPA:ɖɖə) | ḍḍha (IPA:ɖɖʱə) | ḍṇa (IPA:ɖɳə) | ḍta (IPA:ɖt̪ə) | ḍtha (IPA:ɖt̪ʰə) | ḍda (IPA:ɖd̪ə) | ḍdha (IPA:ɖd̪ʱə) | ḍna (IPA:ɖn̪ə) | ḍpa (IPA:ɖpə) | ḍpha (IPA:ɖpʰə) | ḍba (IPA:ɖbə) | ḍbha (IPA:ɖbʱə) | ḍma (IPA:ɖmə) | ḍya (IPA:ɖjə) | ḍra (IPA:ɖrə) | ḍla (IPA:ɖlə) | ḍva (IPA:ɖvə) | ḍśa (IPA:ɖʃə) | ḍṣa (IPA:ɖʂə) | ḍsa (IPA:ɖsə) | ḍha (IPA:ɖhə) | ḍḷa (IPA:ɖɭə) | ḍkṣa (IPA:ɖkʂə) | ḍjña (IPA:ɖɟʝɲə) |

| ḍh (IPA:ɖʱ) | ḍhka (IPA:ɖʱkə) | ḍhkha (IPA:ɖʱkʰə) | ḍhga (IPA:ɖʱɡə) | ḍhgha (IPA:ɖʱɡʱə) | ḍhṅa (IPA:ɖʱŋə) | ḍhca (IPA:ɖʱcɕə) | ḍhcha (IPA:ɖʱcɕʰə) | ḍhja (IPA:ɖʱɟʝə) | ḍhjha (IPA:ɖʱɟʝʱə) | ḍhña (IPA:ɖʱɲə) | ḍhṭa (IPA:ɖʱʈə) | ḍhṭha (IPA:ɖʱʈʰə) | ḍhḍa (IPA:ɖʱɖə) | ḍhḍha (IPA:ɖʱɖʱə) | ḍhṇa (IPA:ɖʱɳə) | ḍhta (IPA:ɖʱt̪ə) | ḍhtha (IPA:ɖʱt̪ʰə) | ḍhda (IPA:ɖʱd̪ə) | ḍhdha (IPA:ɖʱd̪ʱə) | ḍhna (IPA:ɖʱn̪ə) | ḍhpa (IPA:ɖʱpə) | ḍhpha (IPA:ɖʱpʰə) | ḍhba (IPA:ɖʱbə) | ḍhbha (IPA:ɖʱbʱə) | ḍhma (IPA:ɖʱmə) | ḍhya (IPA:ɖʱjə) | ḍhra (IPA:ɖʱrə) | ḍhla (IPA:ɖʱlə) | ḍhva (IPA:ɖʱvə) | ḍhśa (IPA:ɖʱʃə) | ḍhṣa (IPA:ɖʱʂə) | ḍhsa (IPA:ɖʱsə) | ḍhha (IPA:ɖʱhə) | ḍhḷa (IPA:ɖʱɭə) | ḍhkṣa (IPA:ɖʱkʂə) | ḍhjña (IPA:ɖʱɟʝɲə) |

| ṇ (IPA:ɳ) | ṇka (IPA:ɳkə) | ṇkha (IPA:ɳkʰə) | ṇga (IPA:ɳɡə) | ṇgha (IPA:ɳɡʱə) | ṇṅa (IPA:ɳŋə) | ṇca (IPA:ɳcɕə) | ṇcha (IPA:ɳcɕʰə) | ṇja (IPA:ɳɟʝə) | ṇjha (IPA:ɳɟʝʱə) | ṇña (IPA:ɳɲə) | ṇṭa (IPA:ɳʈə) | ṇṭha (IPA:ɳʈʰə) | ṇḍa (IPA:ɳɖə) | ṇḍha (IPA:ɳɖʱə) | ṇṇa (IPA:ɳɳə) | ṇta (IPA:ɳt̪ə) | ṇtha (IPA:ɳt̪ʰə) | ṇda (IPA:ɳd̪ə) | ṇdha (IPA:ɳd̪ʱə) | ṇna (IPA:ɳn̪ə) | ṇpa (IPA:ɳpə) | ṇpha (IPA:ɳpʰə) | ṇba (IPA:ɳbə) | ṇbha (IPA:ɳbʱə) | ṇma (IPA:ɳmə) | ṇya (IPA:ɳjə) | ṇra (IPA:ɳrə) | ṇla (IPA:ɳlə) | ṇva (IPA:ɳvə) | ṇśa (IPA:ɳʃə) | ṇṣa (IPA:ɳʂə) | ṇsa (IPA:ɳsə) | ṇha (IPA:ɳhə) | ṇḷa (IPA:ɳɭə) | ṇkṣa (IPA:ɳkʂə) | ṇjña (IPA:ɳɟʝɲə) |

| t (IPA:t̪) | tka (IPA:t̪kə) | tkha (IPA:t̪kʰə) | tga (IPA:t̪ɡə) | tgha (IPA:t̪ɡʱə) | tṅa (IPA:t̪ŋə) | tca (IPA:t̪cɕə) | tcha (IPA:t̪cɕʰə) | tja (IPA:t̪ɟʝə) | tjha (IPA:t̪ɟʝʱə) | tña (IPA:t̪ɲə) | tṭa (IPA:t̪ʈə) | tṭha (IPA:t̪ʈʰə) | tḍa (IPA:t̪ɖə) | tḍha (IPA:t̪ɖʱə) | tṇa (IPA:t̪ɳə) | tta (IPA:t̪t̪ə) | ttha (IPA:t̪t̪ʰə) | tda (IPA:t̪d̪ə) | tdha (IPA:t̪d̪ʱə) | tna (IPA:t̪n̪ə) | tpa (IPA:t̪pə) | tpha (IPA:t̪pʰə) | tba (IPA:t̪bə) | tbha (IPA:t̪bʱə) | tma (IPA:t̪mə) | tya (IPA:t̪jə) | tra (IPA:t̪rə) | tla (IPA:t̪lə) | tva (IPA:t̪və) | tśa (IPA:t̪ʃə) | tṣa (IPA:t̪ʂə) | tsa (IPA:t̪sə) | tha (IPA:t̪hə) | tḷa (IPA:t̪ɭə) | tkṣa (IPA:t̪kʂə) | tjña (IPA:t̪ɟʝɲə) |

| th (IPA:t̪ʰ) | thka (IPA:t̪ʰkə) | thkha (IPA:t̪ʰkʰə) | thga (IPA:t̪ʰɡə) | thgha (IPA:t̪ʰɡʱə) | thṅa (IPA:t̪ʰŋə) | thca (IPA:t̪ʰcɕə) | thcha (IPA:t̪ʰcɕʰə) | thja (IPA:t̪ʰɟʝə) | thjha (IPA:t̪ʰɟʝʱə) | thña (IPA:t̪ʰɲə) | thṭa (IPA:t̪ʰʈə) | thṭha (IPA:t̪ʰʈʰə) | thḍa (IPA:t̪ʰɖə) | thḍha (IPA:t̪ʰɖʱə) | thṇa (IPA:t̪ʰɳə) | thta (IPA:t̪ʰt̪ə) | ththa (IPA:t̪ʰt̪ʰə) | thda (IPA:t̪ʰd̪ə) | thdha (IPA:t̪ʰd̪ʱə) | thna (IPA:t̪ʰn̪ə) | thpa (IPA:t̪ʰpə) | thpha (IPA:t̪ʰpʰə) | thba (IPA:t̪ʰbə) | thbha (IPA:t̪ʰbʱə) | thma (IPA:t̪ʰmə) | thya (IPA:t̪ʰjə) | thra (IPA:t̪ʰrə) | thla (IPA:t̪ʰlə) | thva (IPA:t̪ʰvə) | thśa (IPA:t̪ʰʃə) | thṣa (IPA:t̪ʰʂə) | thsa (IPA:t̪ʰsə) | thha (IPA:t̪ʰhə) | thḷa (IPA:t̪ʰɭə) | thkṣa (IPA:t̪ʰkʂə) | thjña (IPA:t̪ʰɟʝɲə) |

| d (IPA:d̪) | dka (IPA:d̪kə) | dkha (IPA:d̪kʰə) | dga (IPA:d̪ɡə) | dgha (IPA:d̪ɡʱə) | dṅa (IPA:d̪ŋə) | dca (IPA:d̪cɕə) | dcha (IPA:d̪cɕʰə) | dja (IPA:d̪ɟʝə) | djha (IPA:d̪ɟʝʱə) | dña (IPA:d̪ɲə) | dṭa (IPA:d̪ʈə) | dṭha (IPA:d̪ʈʰə) | dḍa (IPA:d̪ɖə) | dḍha (IPA:d̪ɖʱə) | dṇa (IPA:d̪ɳə) | dta (IPA:d̪t̪ə) | dtha (IPA:d̪t̪ʰə) | dda (IPA:d̪d̪ə) | ddha (IPA:d̪d̪ʱə) | dna (IPA:d̪n̪ə) | dpa (IPA:d̪pə) | dpha (IPA:d̪pʰə) | dba (IPA:d̪bə) | dbha (IPA:d̪bʱə) | dma (IPA:d̪mə) | dya (IPA:d̪jə) | dra (IPA:d̪rə) | dla (IPA:d̪lə) | dva (IPA:d̪və) | dśa (IPA:d̪ʃə) | dṣa (IPA:d̪ʂə) | dsa (IPA:d̪sə) | dha (IPA:d̪hə) | dḷa (IPA:d̪ɭə) | dkṣa (IPA:d̪kʂə) | djña (IPA:d̪ɟʝɲə) |

| dh (IPA:d̪ʱ) | dhka (IPA:d̪ʱkə) | dhkha (IPA:d̪ʱkʰə) | dhga (IPA:d̪ʱɡə) | dhgha (IPA:d̪ʱɡʱə) | dhṅa (IPA:d̪ʱŋə) | dhca (IPA:d̪ʱcɕə) | dhcha (IPA:d̪ʱcɕʰə) | dhja (IPA:d̪ʱɟʝə) | dhjha (IPA:d̪ʱɟʝʱə) | dhña (IPA:d̪ʱɲə) | dhṭa (IPA:d̪ʱʈə) | dhṭha (IPA:d̪ʱʈʰə) | dhḍa (IPA:d̪ʱɖə) | dhḍha (IPA:d̪ʱɖʱə) | dhṇa (IPA:d̪ʱɳə) | dhta (IPA:d̪ʱt̪ə) | dhtha (IPA:d̪ʱt̪ʰə) | dhda (IPA:d̪ʱd̪ə) | dhdha (IPA:d̪ʱd̪ʱə) | dhna (IPA:d̪ʱn̪ə) | dhpa (IPA:d̪ʱpə) | dhpha (IPA:d̪ʱpʰə) | dhba (IPA:d̪ʱbə) | dhbha (IPA:d̪ʱbʱə) | dhma (IPA:d̪ʱmə) | dhya (IPA:d̪ʱjə) | dhra (IPA:d̪ʱrə) | dhla (IPA:d̪ʱlə) | dhva (IPA:d̪ʱvə) | dhśa (IPA:d̪ʱʃə) | dhṣa (IPA:d̪ʱʂə) | dhsa (IPA:d̪ʱsə) | dhha (IPA:d̪ʱhə) | dhḷa (IPA:d̪ʱɭə) | dhkṣa (IPA:d̪ʱkʂə) | dhjña (IPA:d̪ʱɟʝɲə) |

| n (IPA:n̪) | nka (IPA:n̪kə) | nkha (IPA:n̪kʰə) | nga (IPA:n̪ɡə) | ngha (IPA:n̪ɡʱə) | nṅa (IPA:n̪ŋə) | nca (IPA:n̪cɕə) | ncha (IPA:n̪cɕʰə) | nja (IPA:n̪ɟʝə) | njha (IPA:n̪ɟʝʱə) | nña (IPA:n̪ɲə) | nṭa (IPA:n̪ʈə) | nṭha (IPA:n̪ʈʰə) | nḍa (IPA:n̪ɖə) | nḍha (IPA:n̪ɖʱə) | nṇa (IPA:n̪ɳə) | nta (IPA:n̪t̪ə) | ntha (IPA:n̪t̪ʰə) | nda (IPA:n̪d̪ə) | ndha (IPA:n̪d̪ʱə) | nna (IPA:n̪n̪ə) | npa (IPA:n̪pə) | npha (IPA:n̪pʰə) | nba (IPA:n̪bə) | nbha (IPA:n̪bʱə) | nma (IPA:n̪mə) | nya (IPA:n̪jə) | nra (IPA:n̪rə) | nla (IPA:n̪lə) | nva (IPA:n̪və) | nśa (IPA:n̪ʃə) | nṣa (IPA:n̪ʂə) | nsa (IPA:n̪sə) | nha (IPA:n̪hə) | nḷa (IPA:n̪ɭə) | nkṣa (IPA:n̪kʂə) | njña (IPA:n̪ɟʝɲə) |

| p (IPA:p) | pka (IPA:pkə) | pkha (IPA:pkʰə) | pga (IPA:pɡə) | pgha (IPA:pɡʱə) | pṅa (IPA:pŋə) | pca (IPA:pcɕə) | pcha (IPA:pcɕʰə) | pja (IPA:pɟʝə) | pjha (IPA:pɟʝʱə) | pña (IPA:pɲə) | pṭa (IPA:pʈə) | pṭha (IPA:pʈʰə) | pḍa (IPA:pɖə) | pḍha (IPA:pɖʱə) | pṇa (IPA:pɳə) | pta (IPA:pt̪ə) | ptha (IPA:pt̪ʰə) | pda (IPA:pd̪ə) | pdha (IPA:pd̪ʱə) | pna (IPA:pn̪ə) | ppa (IPA:ppə) | ppha (IPA:ppʰə) | pba (IPA:pbə) | pbha (IPA:pbʱə) | pma (IPA:pmə) | pya (IPA:pjə) | pra (IPA:prə) | pla (IPA:plə) | pva (IPA:pvə) | pśa (IPA:pʃə) | pṣa (IPA:pʂə) | psa (IPA:psə) | pha (IPA:phə) | pḷa (IPA:pɭə) | pkṣa (IPA:pkʂə) | pjña (IPA:pɟʝɲə) |

| ph (IPA:pʰ) | phka (IPA:pʰkə) | phkha (IPA:pʰkʰə) | phga (IPA:pʰɡə) | phgha (IPA:pʰɡʱə) | phṅa (IPA:pʰŋə) | phca (IPA:pʰcɕə) | phcha (IPA:pʰcɕʰə) | phja (IPA:pʰɟʝə) | phjha (IPA:pʰɟʝʱə) | phña (IPA:pʰɲə) | phṭa (IPA:pʰʈə) | phṭha (IPA:pʰʈʰə) | phḍa (IPA:pʰɖə) | phḍha (IPA:pʰɖʱə) | phṇa (IPA:pʰɳə) | phta (IPA:pʰt̪ə) | phtha (IPA:pʰt̪ʰə) | phda (IPA:pʰd̪ə) | phdha (IPA:pʰd̪ʱə) | phna (IPA:pʰn̪ə) | phpa (IPA:pʰpə) | phpha (IPA:pʰpʰə) | phba (IPA:pʰbə) | phbha (IPA:pʰbʱə) | phma (IPA:pʰmə) | phya (IPA:pʰjə) | phra (IPA:pʰrə) | phla (IPA:pʰlə) | phva (IPA:pʰvə) | phśa (IPA:pʰʃə) | phṣa (IPA:pʰʂə) | phsa (IPA:pʰsə) | phha (IPA:pʰhə) | phḷa (IPA:pʰɭə) | phkṣa (IPA:pʰkʂə) | phjña (IPA:pʰɟʝɲə) |

| b (IPA:b) | bka (IPA:bkə) | bkha (IPA:bkʰə) | bga (IPA:bɡə) | bgha (IPA:bɡʱə) | bṅa (IPA:bŋə) | bca (IPA:bcɕə) | bcha (IPA:bcɕʰə) | bja (IPA:bɟʝə) | bjha (IPA:bɟʝʱə) | bña (IPA:bɲə) | bṭa (IPA:bʈə) | bṭha (IPA:bʈʰə) | bḍa (IPA:bɖə) | bḍha (IPA:bɖʱə) | bṇa (IPA:bɳə) | bta (IPA:bt̪ə) | btha (IPA:bt̪ʰə) | bda (IPA:bd̪ə) | bdha (IPA:bd̪ʱə) | bna (IPA:bn̪ə) | bpa (IPA:bpə) | bpha (IPA:bpʰə) | bba (IPA:bbə) | bbha (IPA:bbʱə) | bma (IPA:bmə) | bya (IPA:bjə) | bra (IPA:brə) | bla (IPA:blə) | bva (IPA:bvə) | bśa (IPA:bʃə) | bṣa (IPA:bʂə) | bsa (IPA:bsə) | bha (IPA:bhə) | bḷa (IPA:bɭə) | bkṣa (IPA:bkʂə) | bjña (IPA:bɟʝɲə) |

| bh (IPA:bʱ) | bhka (IPA:bʱkə) | bhkha (IPA:bʱkʰə) | bhga (IPA:bʱɡə) | bhgha (IPA:bʱɡʱə) | bhṅa (IPA:bʱŋə) | bhca (IPA:bʱcɕə) | bhcha (IPA:bʱcɕʰə) | bhja (IPA:bʱɟʝə) | bhjha (IPA:bʱɟʝʱə) | bhña (IPA:bʱɲə) | bhṭa (IPA:bʱʈə) | bhṭha (IPA:bʱʈʰə) | bhḍa (IPA:bʱɖə) | bhḍha (IPA:bʱɖʱə) | bhṇa (IPA:bʱɳə) | bhta (IPA:bʱt̪ə) | bhtha (IPA:bʱt̪ʰə) | bhda (IPA:bʱd̪ə) | bhdha (IPA:bʱd̪ʱə) | bhna (IPA:bʱn̪ə) | bhpa (IPA:bʱpə) | bhpha (IPA:bʱpʰə) | bhba (IPA:bʱbə) | bhbha (IPA:bʱbʱə) | bhma (IPA:bʱmə) | bhya (IPA:bʱjə) | bhra (IPA:bʱrə) | bhla (IPA:bʱlə) | bhva (IPA:bʱvə) | bhśa (IPA:bʱʃə) | bhṣa (IPA:bʱʂə) | bhsa (IPA:bʱsə) | bhha (IPA:bʱhə) | bhḷa (IPA:bʱɭə) | bhkṣa (IPA:bʱkʂə) | bhjña (IPA:bʱɟʝɲə) |

| m (IPA:m) | mka (IPA:mkə) | mkha (IPA:mkʰə) | mga (IPA:mɡə) | mgha (IPA:mɡʱə) | mṅa (IPA:mŋə) | mca (IPA:mcɕə) | mcha (IPA:mcɕʰə) | mja (IPA:mɟʝə) | mjha (IPA:mɟʝʱə) | mña (IPA:mɲə) | mṭa (IPA:mʈə) | mṭha (IPA:mʈʰə) | mḍa (IPA:mɖə) | mḍha (IPA:mɖʱə) | mṇa (IPA:mɳə) | mta (IPA:mt̪ə) | mtha (IPA:mt̪ʰə) | mda (IPA:md̪ə) | mdha (IPA:md̪ʱə) | mna (IPA:mn̪ə) | mpa (IPA:mpə) | mpha (IPA:mpʰə) | mba (IPA:mbə) | mbha (IPA:mbʱə) | mma (IPA:mmə) | mya (IPA:mjə) | mra (IPA:mrə) | mla (IPA:mlə) | mva (IPA:mvə) | mśa (IPA:mʃə) | mṣa (IPA:mʂə) | msa (IPA:msə) | mha (IPA:mhə) | mḷa (IPA:mɭə) | mkṣa (IPA:mkʂə) | mjña (IPA:mɟʝɲə) |

| y (IPA:j) | yka (IPA:jkə) | ykha (IPA:jkʰə) | yga (IPA:jɡə) | ygha (IPA:jɡʱə) | yṅa (IPA:jŋə) | yca (IPA:jcɕə) | ycha (IPA:jcɕʰə) | yja (IPA:jɟʝə) | yjha (IPA:jɟʝʱə) | yña (IPA:jɲə) | yṭa (IPA:jʈə) | yṭha (IPA:jʈʰə) | yḍa (IPA:jɖə) | yḍha (IPA:jɖʱə) | yṇa (IPA:jɳə) | yta (IPA:jt̪ə) | ytha (IPA:jt̪ʰə) | yda (IPA:jd̪ə) | ydha (IPA:jd̪ʱə) | yna (IPA:jn̪ə) | ypa (IPA:jpə) | ypha (IPA:jpʰə) | yba (IPA:jbə) | ybha (IPA:jbʱə) | yma (IPA:jmə) | yya (IPA:jjə) | yra (IPA:jrə) | yla (IPA:jlə) | yva (IPA:jvə) | yśa (IPA:jʃə) | yṣa (IPA:jʂə) | ysa (IPA:jsə) | yha (IPA:jhə) | yḷa (IPA:jɭə) | ykṣa (IPA:jkʂə) | yjña (IPA:jɟʝɲə) |

| r (IPA:r) | rka (IPA:rkə) | rkha (IPA:rkʰə) | rga (IPA:rɡə) | rgha (IPA:rɡʱə) | rṅa (IPA:rŋə) | rca (IPA:rcɕə) | rcha (IPA:rcɕʰə) | rja (IPA:rɟʝə) | rjha (IPA:rɟʝʱə) | rña (IPA:rɲə) | rṭa (IPA:rʈə) | rṭha (IPA:rʈʰə) | rḍa (IPA:rɖə) | rḍha (IPA:rɖʱə) | rṇa (IPA:rɳə) | rta (IPA:rt̪ə) | rtha (IPA:rt̪ʰə) | rda (IPA:rd̪ə) | rdha (IPA:rd̪ʱə) | rna (IPA:rn̪ə) | rpa (IPA:rpə) | rpha (IPA:rpʰə) | rba (IPA:rbə) | rbha (IPA:rbʱə) | rma (IPA:rmə) | rya (IPA:rjə) | rra (IPA:rrə) | rla (IPA:rlə) | rva (IPA:rvə) | rśa (IPA:rʃə) | rṣa (IPA:rʂə) | rsa (IPA:rsə) | rha (IPA:rhə) | rḷa (IPA:rɭə) | rkṣa (IPA:rkʂə) | rjña (IPA:rɟʝɲə) |

| l (IPA:l) | lka (IPA:lkə) | lkha (IPA:lkʰə) | lga (IPA:lɡə) | lgha (IPA:lɡʱə) | lṅa (IPA:lŋə) | lca (IPA:lcɕə) | lcha (IPA:lcɕʰə) | lja (IPA:lɟʝə) | ljha (IPA:lɟʝʱə) | lña (IPA:lɲə) | lṭa (IPA:lʈə) | lṭha (IPA:lʈʰə) | lḍa (IPA:lɖə) | lḍha (IPA:lɖʱə) | lṇa (IPA:lɳə) | lta (IPA:lt̪ə) | ltha (IPA:lt̪ʰə) | lda (IPA:ld̪ə) | ldha (IPA:ld̪ʱə) | lna (IPA:ln̪ə) | lpa (IPA:lpə) | lpha (IPA:lpʰə) | lba (IPA:lbə) | lbha (IPA:lbʱə) | lma (IPA:lmə) | lya (IPA:ljə) | lra (IPA:lrə) | lla (IPA:llə) | lva (IPA:lvə) | lśa (IPA:lʃə) | lṣa (IPA:lʂə) | lsa (IPA:lsə) | lha (IPA:lhə) | lḷa (IPA:lɭə) | lkṣa (IPA:lkʂə) | ljña (IPA:lɟʝɲə) |

| v (IPA:v) | vka (IPA:vkə) | vkha (IPA:vkʰə) | vga (IPA:vɡə) | vgha (IPA:vɡʱə) | vṅa (IPA:vŋə) | vca (IPA:vcɕə) | vcha (IPA:vcɕʰə) | vja (IPA:vɟʝə) | vjha (IPA:vɟʝʱə) | vña (IPA:vɲə) | vṭa (IPA:vʈə) | vṭha (IPA:vʈʰə) | vḍa (IPA:vɖə) | vḍha (IPA:vɖʱə) | vṇa (IPA:vɳə) | vta (IPA:vt̪ə) | vtha (IPA:vt̪ʰə) | vda (IPA:vd̪ə) | vdha (IPA:vd̪ʱə) | vna (IPA:vn̪ə) | vpa (IPA:vpə) | vpha (IPA:vpʰə) | vba (IPA:vbə) | vbha (IPA:vbʱə) | vma (IPA:vmə) | vya (IPA:vjə) | vra (IPA:vrə) | vla (IPA:vlə) | vva (IPA:vvə) | vśa (IPA:vʃə) | vṣa (IPA:vʂə) | vsa (IPA:vsə) | vha (IPA:vhə) | vḷa (IPA:vɭə) | vkṣa (IPA:vkʂə) | vjña (IPA:vɟʝɲə) |

| ś (IPA:ʃ) | śka (IPA:ʃkə) | śkha (IPA:ʃkʰə) | śga (IPA:ʃɡə) | śgha (IPA:ʃɡʱə) | śṅa (IPA:ʃŋə) | śca (IPA:ʃcɕə) | ścha (IPA:ʃcɕʰə) | śja (IPA:ʃɟʝə) | śjha (IPA:ʃɟʝʱə) | śña (IPA:ʃɲə) | śṭa (IPA:ʃʈə) | śṭha (IPA:ʃʈʰə) | śḍa (IPA:ʃɖə) | śḍha (IPA:ʃɖʱə) | śṇa (IPA:ʃɳə) | śta (IPA:ʃt̪ə) | śtha (IPA:ʃt̪ʰə) | śda (IPA:ʃd̪ə) | śdha (IPA:ʃd̪ʱə) | śna (IPA:ʃn̪ə) | śpa (IPA:ʃpə) | śpha (IPA:ʃpʰə) | śba (IPA:ʃbə) | śbha (IPA:ʃbʱə) | śma (IPA:ʃmə) | śya (IPA:ʃjə) | śra (IPA:ʃrə) | śla (IPA:ʃlə) | śva (IPA:ʃvə) | śśa (IPA:ʃʃə) | śṣa (IPA:ʃʃə) | śsa (IPA:ʃsə) | śha (IPA:ʃhə) | śḷa (IPA:ʃɭə) | śkṣa (IPA:ʃkʃə) | śjña (IPA:ʃɟʝɲə) |

| ṣ (IPA:ʂ) | ṣka (IPA:ʃkə) | ṣkha (IPA:ʃkʰə) | ṣga (IPA:ʃɡə) | ṣgha (IPA:ʃɡʱə) | ṣṅa (IPA:ʃŋə) | ṣca (IPA:ʃcɕə) | ṣcha (IPA:ʃcɕʰə) | ṣja (IPA:ʃɟʝə) | ṣjha (IPA:ʃɟʝʱə) | ṣña (IPA:ʃɲə) | ṣṭa (IPA:ʃʈə) | ṣṭha (IPA:ʃʈʰə) | ṣḍa (IPA:ʃɖə) | ṣḍha (IPA:ʃɖʱə) | ṣṇa (IPA:ʃɳə) | ṣta (IPA:ʃt̪ə) | ṣtha (IPA:ʃt̪ʰə) | ṣda (IPA:ʃd̪ə) | ṣdha (IPA:ʃd̪ʱə) | ṣna (IPA:ʃn̪ə) | ṣpa (IPA:ʃpə) | ṣpha (IPA:ʃpʰə) | ṣba (IPA:ʃbə) | ṣbha (IPA:ʃbʱə) | ṣma (IPA:ʃmə) | ṣya (IPA:ʃjə) | ṣra (IPA:ʃrə) | ṣla (IPA:ʃlə) | ṣva (IPA:ʃvə) | ṣśa (IPA:ʃʃə) | \1ṣa (IPA:ʃʃə) | ṣsa (IPA:ʃsə) | ṣha (IPA:ʃhə) | ṣḷa (IPA:ʃɭə) | ṣkṣa (IPA:ʃkʃə) | ṣjña (IPA:ʃɟʝɲə) |

| s (IPA:s) | ska (IPA:skə) | skha (IPA:skʰə) | sga (IPA:sɡə) | sgha (IPA:sɡʱə) | sṅa (IPA:sŋə) | sca (IPA:scɕə) | scha (IPA:scɕʰə) | sja (IPA:sɟʝə) | sjha (IPA:sɟʝʱə) | sña (IPA:sɲə) | sṭa (IPA:sʈə) | sṭha (IPA:sʈʰə) | sḍa (IPA:sɖə) | sḍha (IPA:sɖʱə) | sṇa (IPA:sɳə) | sta (IPA:st̪ə) | stha (IPA:st̪ʰə) | sda (IPA:sd̪ə) | sdha (IPA:sd̪ʱə) | sna (IPA:sn̪ə) | spa (IPA:spə) | spha (IPA:spʰə) | sba (IPA:sbə) | sbha (IPA:sbʱə) | sma (IPA:smə) | sya (IPA:sjə) | sra (IPA:srə) | sla (IPA:slə) | sva (IPA:svə) | sśa (IPA:sʃə) | sṣa (IPA:sʂə) | ssa (IPA:ssə) | sha (IPA:shə) | sḷa (IPA:sɭə) | skṣa (IPA:skʂə) | sjña (IPA:sɟʝɲə) |

| h (IPA:h) | hka (IPA:hkə) | hkha (IPA:hkʰə) | hga (IPA:hɡə) | hgha (IPA:hɡʱə) | hṅa (IPA:hŋə) | hca (IPA:hcɕə) | hcha (IPA:hcɕʰə) | hja (IPA:hɟʝə) | hjha (IPA:hɟʝʱə) | hña (IPA:hɲə) | hṭa (IPA:hʈə) | hṭha (IPA:hʈʰə) | hḍa (IPA:hɖə) | hḍha (IPA:hɖʱə) | hṇa (IPA:hɳə) | hta (IPA:ht̪ə) | htha (IPA:ht̪ʰə) | hda (IPA:hd̪ə) | hdha (IPA:hd̪ʱə) | hna (IPA:hn̪ə) | hpa (IPA:hpə) | hpha (IPA:hpʰə) | hba (IPA:hbə) | hbha (IPA:hbʱə) | hma (IPA:hmə) | hya (IPA:hjə) | hra (IPA:hrə) | hla (IPA:hlə) | hva (IPA:hvə) | hśa (IPA:hʃə) | hṣa (IPA:hʂə) | hsa (IPA:hsə) | hha (IPA:hhə) | hḷa (IPA:hɭə) | hkṣa (IPA:hkʂə) | hjña (IPA:hɟʝɲə) |

| ḷ (IPA:ɭ) | ḷka (IPA:ɭkə) | ḷkha (IPA:ɭkʰə) | ḷga (IPA:ɭɡə) | ḷgha (IPA:ɭɡʱə) | ḷṅa (IPA:ɭŋə) | ḷca (IPA:ɭcɕə) | ḷcha (IPA:ɭcɕʰə) | ḷja (IPA:ɭɟʝə) | ḷjha (IPA:ɭɟʝʱə) | ḷña (IPA:ɭɲə) | ḷṭa (IPA:ɭʈə) | ḷṭha (IPA:ɭʈʰə) | ḷḍa (IPA:ɭɖə) | ḷḍha (IPA:ɭɖʱə) | ḷṇa (IPA:ɭɳə) | ḷta (IPA:ɭt̪ə) | ḷtha (IPA:ɭt̪ʰə) | ḷda (IPA:ɭd̪ə) | ḷdha (IPA:ɭd̪ʱə) | ḷna (IPA:ɭn̪ə) | ḷpa (IPA:ɭpə) | ḷpha (IPA:ɭpʰə) | ḷba (IPA:ɭbə) | ḷbha (IPA:ɭbʱə) | ḷma (IPA:ɭmə) | ḷya (IPA:ɭjə) | ḷra (IPA:ɭrə) | ḷla (IPA:ɭlə) | ḷva (IPA:ɭvə) | ḷśa (IPA:ɭʃə) | ḷṣa (IPA:ɭʂə) | ḷsa (IPA:ɭsə) | ḷha (IPA:ɭhə) | ḷḷa (IPA:ɭɭə) | ḷkṣa (IPA:ɭkʂə) | ḷjña (IPA:ɭɟʝɲə) |

Accent marks

The pitch accent of Vedic Sanskrit is written with various symbols depending on shakha. In the Rigveda, anudātta is written with a bar below the line (◌॒), svarita with a stroke above the line (◌॑) while udātta is unmarked.

Punctuation

The end of a sentence or half-verse may be marked with a dot known as a pūrṇa virām or a vertical line danda: ।. The end of a full verse may be marked with two vertical lines: ॥. A comma, or alpa virām, is used to denote a natural pause in speech.[51][52] Other punctuation marks such as colon, semi-colon, exclamation mark, dash and question mark currently in use in Devanagari script match those in European languages.[53]

Old forms

The following letter variants are also in use, particularly in older texts.[54]

| Standard form | Variant form |

|---|---|

Numerals

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Fonts

A variety of fonts are in use for Devanagari. These include, but are not limited to, Akshar,[55] Annapurna,[56] Arial,[57] CDAC-Gist Surekh,[58] CDAC-Gist Yogesh,[59] Chanda,[60] Gargi,[61] Gurumaa,[62] Jaipur,[63] Jana,[64] Kalimati,[65] Kanjirowa,[66] Mangal,[67] Raghu,[68] Sanskrit Ashram,[69] Santipur OT,[60] Thyaka,[70] and Uttara.[60]

The form of Devanagari fonts vary with function. According to Harvard College for Sanskrit studies, "Uttara [companion to Chanda] is the best in terms of ligatures but, because it is designed for Vedic as well, requires so much vertical space that it is not well suited for the "user interface font" (though an excellent choice for the "original field" font). Santipur OT is a beautiful font reflecting a very early [medieval era] typesetting style for Devanagari. Sanskrit 2003[71] is a good all-around font and has more ligatures than most fonts, though students will probably find the spacing of the CDAC-Gist Surekh[58] font makes for quicker comprehension and reading."[60]

Transliteration

There are several methods of Romanisation or transliteration from Devanagari to the Roman script.[72]

Hunterian system

The Hunterian system is the "national system of romanisation in India" and the one officially adopted by the Government of India.[73][74][75]

ISO 15919

A standard transliteration convention was codified in the ISO 15919 standard of 2001. It uses diacritics to map the much larger set of Brahmic graphemes to the Latin script. The Devanagari-specific portion is nearly identical to the academic standard for Sanskrit, IAST.[76]

IAST

The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) is the academic standard for the romanisation of Sanskrit. IAST is the de facto standard used in printed publications, like books, magazines, and electronic texts with Unicode fonts. It is based on a standard established by the Congress of Orientalists at Athens in 1912. The ISO 15919 standard of 2001 codified the transliteration convention to include an expanded standard for sister scripts of Devanagari.[76]

The National Library at Kolkata romanisation, intended for the romanisation of all Indic scripts, is an extension of IAST.

Harvard-Kyoto

Compared to IAST, Harvard-Kyoto looks much simpler. It does not contain all the diacritic marks that IAST contains. It was designed to simplify the task of putting large amount of Sanskrit textual material into machine readable form, and the inventors stated that it reduces the effort needed in transliteration of Sanskrit texts on the keyboard.[77] This makes typing in Harvard-Kyoto much easier than IAST. Harvard-Kyoto uses capital letters that can be difficult to read in the middle of words.

ITRANS

ITRANS is a lossless transliteration scheme of Devanagari into ASCII that is widely used on Usenet. It is an extension of the Harvard-Kyoto scheme. In ITRANS, the word devanāgarī is written "devanaagarii" or "devanAgarI". ITRANS is associated with an application of the same name that enables typesetting in Indic scripts. The user inputs in Roman letters and the ITRANS pre-processor translates the Roman letters into Devanagari (or other Indic languages). The latest version of ITRANS is version 5.30 released in July, 2001. It is similar to Velthius system and was created by Avinash Chopde to help print various Indic scripts with personal computers.[77]

Velthuis

Main article: Velthuis

The disadvantage of the above ASCII schemes is case-sensitivity, implying that transliterated names may not be capitalized. This difficulty is avoided with the system developed in 1996 by Frans Velthuis for TeX, loosely based on IAST, in which case is irrelevant.

ALA-LC Romanisation

ALA-LC[78] romanisation is a transliteration scheme approved by the Library of Congress and the American Library Association, and widely used in North American libraries. Transliteration tables are based on languages, so there is a table for Hindi,[79] one for Sanskrit and Prakrit,[80] etc.

WX

WX is a Roman transliteration scheme for Indian languages, widely used among the natural language processing community in India. It originated at IIT Kanpur for computational processing of Indian languages. The salient features of this transliteration scheme are as follows.

- Every consonant and every vowel has a single mapping into Roman. Hence it is a prefix code, advantageous from computation point of view.

- Lower-case letters are used for unaspirated consonants and short vowels, while capital letters are used for aspirated consonants and long vowels. While the retroflex stops are mapped to 't, T, d, D, N', the dentals are mapped to 'w, W, x, X, n'. Hence the name 'WX', a reminder of this idiosyncratic mapping.

Encodings

ISCII

ISCII is an 8-bit encoding. The lower 128 codepoints are plain ASCII, the upper 128 codepoints are ISCII-specific.

It has been designed for representing not only Devanagari but also various other Indic scripts as well as a Latin-based script with diacritic marks used for transliteration of the Indic scripts.

ISCII has largely been superseded by Unicode, which has, however, attempted to preserve the ISCII layout for its Indic language blocks.

Unicode

The Unicode Standard defines three blocks for Devanagari: Devanagari (U+0900–U+097F), Devanagari Extended (U+A8E0–U+A8FF), and Vedic Extensions (U+1CD0–U+1CFF).

| Devanagari[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+090x | ऀ | ँ | ं | ः | ऄ | अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ऋ | ऌ | ऍ | ऎ | ए |

| U+091x | ऐ | ऑ | ऒ | ओ | औ | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट |

| U+092x | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | ऩ | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य |

| U+093x | र | ऱ | ल | ळ | ऴ | व | श | ष | स | ह | ऺ | ऻ | ़ | ऽ | ा | ि |

| U+094x | ी | ु | ू | ृ | ॄ | ॅ | ॆ | े | ै | ॉ | ॊ | ो | ौ | ् | ॎ | ॏ |

| U+095x | ॐ | ॑ | ॒ | ॓ | ॔ | ॕ | ॖ | ॗ | क़ | ख़ | ग़ | ज़ | ड़ | ढ़ | फ़ | य़ |

| U+096x | ॠ | ॡ | ॢ | ॣ | । | ॥ | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| U+097x | ॰ | ॱ | ॲ | ॳ | ॴ | ॵ | ॶ | ॷ | ॸ | ॹ | ॺ | ॻ | ॼ | ॽ | ॾ | ॿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Devanagari Extended[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A8Ex | ꣠ | ꣡ | ꣢ | ꣣ | ꣤ | ꣥ | ꣦ | ꣧ | ꣨ | ꣩ | ꣪ | ꣫ | ꣬ | ꣭ | ꣮ | ꣯ |

| U+A8Fx | ꣰ | ꣱ | ꣲ | ꣳ | ꣴ | ꣵ | ꣶ | ꣷ | ꣸ | ꣹ | ꣺ | ꣻ | ꣼ | ꣽ | ꣾ | ꣿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Vedic Extensions[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1CDx | ᳐ | ᳑ | ᳒ | ᳓ | ᳔ | ᳕ | ᳖ | ᳗ | ᳘ | ᳙ | ᳚ | ᳛ | ᳜ | ᳝ | ᳞ | ᳟ |

| U+1CEx | ᳠ | ᳡ | ᳢ | ᳣ | ᳤ | ᳥ | ᳦ | ᳧ | ᳨ | ᳩ | ᳪ | ᳫ | ᳬ | ᳭ | ᳮ | ᳯ |

| U+1CFx | ᳰ | ᳱ | ᳲ | ᳳ | ᳴ | ᳵ | ᳶ | ᳷ | ᳸ | ᳹ | ᳺ | |||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Devanagari keyboard layouts

- For a list of Devanagari input tools and fonts, please see Help:Multilingual support (Indic).

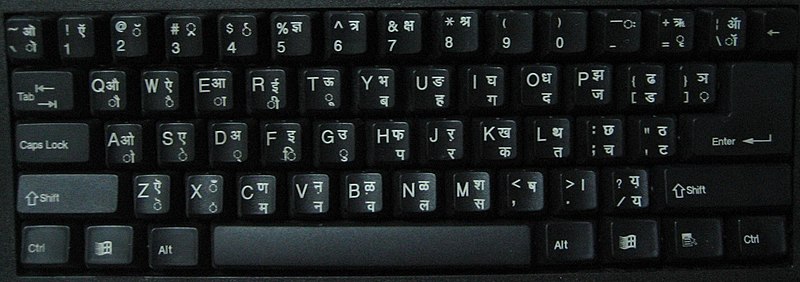

InScript is the standard keyboard layout for Devanagari. It is inbuilt in all modern major operating systems. Microsoft Windows supports the InScript layout (using the Mangal font), which can be used to input unicode Devanagari characters. InScript is also available in some touchscreen mobile phones.

InScript layout

A Devanagari INSCRIPT bilingual keyboard.

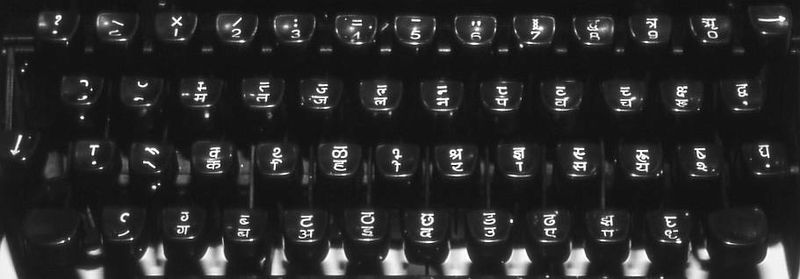

Typewriter

This layout was used on manual typewriters when computers were not available or were uncommon. For backward compatibility some typing tools like Indic IME still provide this layout.

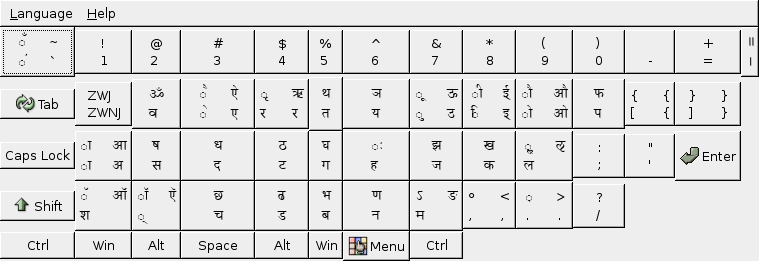

Phonetic

Such tools work on phonetic transliteration. The user writes in Roman and the IME automatically converts it into Devanagari. Some popular phonetic typing tools are BarahaIME and Google IME.

The Mac OS X operating system includes two different keyboard layouts for Devanagari: one is much like INSCRIPT/KDE Linux, the other is a phonetic layout called "Devanagari QWERTY".

Any one of Unicode fonts input system is fine for Indic language Wikipedia and other wikiprojects, including Hindi, Bhojpuri, Marathi, Nepali Wikipedia. Some people use inscript. Majority uses either Google phonetic transliteration or input facility Universal Language Selector provided on Wikipedia.On Indic language wikiprojects Phonetic facility provided initially was java-based later supported by Narayam extension for phonetic input facility. Currently Indic language Wiki projects are supported by Universal Language Selector (ULS), that offers both phonetic keyboard (Aksharantaran,Marathi:अक्षरांतरण, Hindi:लिप्यंतरण, बोलनागरी ) and InScript keyboard (Marathi:मराठी लिपी).

The Ubuntu Linux operating system supports several keyboard layouts for Devanagari, including Harvard-Kyoto, WX notation, Bolanagari and phonetic.

See also

- Clip font

- Devanagari transliteration

- Devanagari Braille

- ISCII

- Nagari Pracharini Sabha

- Nepali

- Schwa deletion in Indo-Aryan languages

References

- Footnotes

- ^ a b Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency at Google Books, Rudradaman’s inscription from 1st through 4th century CE found in Gujarat, India, Stanford University Archives, pages 30-45, particularly Devanagari inscription on Jayadaman's coins pages 33-34

- ^ a b Isaac Taylor (1883), History of the Alphabet: Aryan Alphabets, Part 2, Kegan Paul, Trench & Co, p. 333, ISBN 978-0-7661-5847-4,

... In the Kutila this develops into a short horizontal bar, which, in the Devanagari, becomes a continuous horizontal line ... three cardinal inscriptions of this epoch, namely, the Kutila or Bareli inscription of 992, the Chalukya or Kistna inscription of 945, and a Kawi inscription of 919 ... the Kutila inscription is of great importance in Indian epigraphy, not only from its precise date, but from its offering a definite early form of the standard Indian alphabet, the Devanagari ...

- ^ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian epigraphy: a guide to the study of inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan languages. South Asia research. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0-19-509984-3.

- ^ a b Kathleen Kuiper (2010), The Culture of India, New York: The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 978-1615301492, page 83

- ^ a b George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, pages 72-74

- ^ George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, pages 68-69

- ^ a b Richard Salomon (2014), Indian Epigraphy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195356663, pages 40-42

- ^ Michael Willis (2001), Inscriptions from Udayagiri: locating domains of devotion, patronage and power in the eleventh century, South Asian Studies, 17(1), pages 41-53

- ^ Brick with Sanskrit inscription in Nagari script, 1217 CE, found in Uttar Pradesh, India (British Museum)

- ^ a b c d George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, pages 75-77

- ^ Wayan Ardika (2009), Form, Macht, Differenz: Motive und Felder ethnologischen Forschens (Editors: Elfriede Hermann et al.), Universitätsverlag Göttingen, ISBN 978-3940344809, pages 251-252; Quote: "Nagari script and Sanskrit language in the inscription at Blangjong suggests that Indian culture was already influencing Bali (Indonesia) by the 10th century AD."

- ^ a b c d Devanagari (Nagari), Script Features and Description, SIL International (2013), United States

- ^ Hindi, Omniglot Encyclopedia of Writing Systems and Languages

- ^ David Templin. "Devanagari script". omniglot.com. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ George Cardona and Danesh Jain (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415772945, page 75

- ^ Reinhold Grünendahl (2001), South Indian Scripts in Sanskrit Manuscripts and Prints, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447045049, pages xxii, 201-210

- ^ Akira Nakanishi, Writing systems of the World, ISBN 978-0804816540, page 48

- ^ a b c d Steven Roger Fischer (2004), A history of writing, Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-86189-167-9,

... an early branch of this, as of the fourth century CE, was the Gupta script, Brahmi's first main daughter ... the Gupta alphabet became the ancestor of most Indic scripts (usually through later Devanagari) ... Nagari, of India's north-west, first appeared around 633 CE ... in the eleventh century, Nagari had become Devanagari, or 'heavenly Nagari', since it was now the main vehicle, out of several, for Sanskrit literature ...

- ^ Krishna Chandra Sagar (1993), Foreign Influence on Ancient India, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-8172110284, page 137

- ^ Richard Salomon (2014), Indian Epigraphy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195356663, page 71

- ^ William Woodville Rockhill, Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, p. 671, at Google Books, United States National Museum, page 671

- ^ David Quinter (2015), From Outcasts to Emperors: Shingon Ritsu and the Mañjuśrī Cult in Medieval Japan, Brill, ISBN 978-9004293397, pages 63-65 with discussion on Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra

- ^ Richard Salomon (2014), Indian Epigraphy, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195356663, pages 157-160

- ^ Michael Witzel (2006), in Between the Empires : Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE (Editor: Patrick Olivelle), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195305326, pages 477-480 with footnote 60;

Original manuscript, dates in Saka Samvat, and uncertainties associated with it: Mahabhasya of Patanjali, F Kielhorn - ^ Monier Williams Online Dictionary, nagara, Cologne Sanskrit Digital Lexicon, Germany

- ^ Salomon (2003:70)

- ^ "Archives.conlang.info". Archives.conlang.info. 2004-12-07. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ Salomon (2003:71)

- ^ a b Salomon (2003:75)

- ^ Wikner (1996:13, 14)

- ^ Wikner (1996:6)

- ^ Snell (2000:44–45)

- ^ Snell (2000:64)

- ^ Snell (2000:45)

- ^ Snell (2000:46)

- ^ Salomon (2003:77)

- ^ Verma (2003:501)

- ^ Wikner (1996:73)

- ^ Masica (1991:97)

- ^ a b Larry M. Hyman, Victoria Fromkin, Charles N. Li (1988), Language, speech, and mind, Part 2, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-00311-3,

... The implicit /a/ is not read when the symbol appears in word-final position or in certain other contexts where it is obligatorily deleted via the so-called schwa-deletion rule which plays a crucial role in Hindi word phonology ...

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Tej K. Bhatia (1987), A history of the Hindi grammatical tradition: Hindi-Hindustani grammar, grammarians, history and problems, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-07924-6,

... Hindi literature fails as a reliable indicator of the actual pronunciation because it is written in the Devanagari script ... the schwa syncope rule which operates in Hindi ...

- ^ a b c Monojit Choudhury, Anupam Basu and Sudeshna Sarkar (July 2004), "A Diachronic Approach for Schwa Deletion in Indo Aryan Languages" (PDF), Proceedings of the Workshop of the ACL Special Interest Group on Computational Phonology (SIGPHON), Association for Computations Linguistics,

... schwa deletion is an important issue for grapheme-to-phoneme conversion of IAL, which in turn is required for a good Text-to-Speech synthesiser ...

- ^ a b Naim R. Tyson, Ila Nagar (2009), "Prosodic rules for schwa-deletion in Hindi text-to-speech synthesis" (PDF), International Journal of Speech Technology,

... Without the appropriate deletion of schwas, any speech output would sound unnatural. Since the orthographical representation of Devanagari gives little indication of deletion sites, modern TTS systems for Hindi implemented schwa deletion rules based on the segmental context where schwa appears ...

- ^ Nazir Ali Jairazbhoy, The rāgs of North Indian music: their structure and evolution, Popular Prakashan, 1995, ISBN 978-81-7154-395-3,

... The Devnagri (Devanagari) script is syllabic and all consonants carry the inherent vowel a unless otherwise indicated. The principal difference between modern Hindi and the classical Sanskrit forms is the omission in Hindi ...

- ^ a b c Monojit Choudhury and Anupam Basu (July 2004), "A Rule Based Schwa Deletion Algorithm for Hindi" (PDF), Proceedings of the International Conference On Knowledge-Based Computer Systems,

... Without any schwa deletion, not only the two words will sound very unnatural, but it will also be extremely difficult for the listener to distinguish between the two, the only difference being nasalisation of the e at the end of the former. However, a native speaker would pronounce the former as dha.D-kan-eM and the later as dha.Dak-ne, which are clearly distinguishable ...

- ^ a b Janet Pierrehumbert, Rami Nair, Volume Editor: Bernard Laks, Implications of Hindi Prosodic Structure (Current Trends in Phonology: Models and Methods), European Studies Research Institute, University of Salford Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1-901471-02-1,

... showed extremely regular patterns. As is not uncommon in a study of subphonemic detail, the objective data patterned much more cleanly than intuitive judgments ... [w] occurs when /व/ is in onglide position ... [v] occurs otherwise ...

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "TDIL (Technology Development for Indian Languages) Font Download". TDIL. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ^ Saloman, Richard (2007) “Typological Observations on the Indic Scripts” in The Indic Scripts: Paleographic and Linguistic Perspecticves D.K. Printworld Ltd., New Delhi. ISBN 812460406-1. p. 33.

- ^ "The Unicode Standard, chapter 9, South Asian Scripts I" (PDF). The Unicode Standard, v. 6.0. Unicode, Inc. Retrieved Feb 12, 2012.

- ^ The romanization shown is identical to IAST, except that ळ (which is not used in Sanskrit) has the ISO romanization ḷ, which in IAST is the dental vowel l.

- ^ Unicode Consortium, The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Volume 1, ISBN 978-0201616330, Addison-Wesley, pages 221-223

- ^ Transliteration from Hindi Script to Meetei Mayek Watham and Vimal (2013), IJETR, page 550

- ^ Michael Shapiro (2014), The Devanagari Writing System in A Primer of Modern Standard Hindi, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805088, page 26

- ^ Bahri 2004, p. (xiii)

- ^ Akshar Unicode South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Annapurna SIL Unicode, SIL International (2013)

- ^ Arial Unicode South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ a b CDAC-GIST Surekh Unicode South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ CDAC-GIST Yogesh South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ a b c d Sanskrit Devanagari Fonts Harvard University (2010); see Chanda and Uttara ttf 2010 archive (Accessed: July 8, 2015)

- ^ Gargi South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Gurumaa Unicode - a sans font KDE (2012)

- ^ Jaipur South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Jana South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Kalimati South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Kanjirowa South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Mangal South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Raghu South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Sanskrit Ashram South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Thyaka South Asia Language Resource, University of Chicago (2009)

- ^ Devanagari font Unicode Standard 8.0 (2015)

- ^ Daya Nand Sharma, Transliteration into Roman and Devanagari of the languages of the Indian group, Survey of India, 1972,

... With the passage of time there has emerged a practically uniform system of transliteration of Devanagari and allied alphabets. Nevertheless, no single system of Romanisation has yet developed ...

- ^ United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Technical reference manual for the standardisation of geographical names, United Nations Publications, 2007, ISBN 978-92-1-161500-5,

... ISO 15919 ... There is no evidence of the use of the system either in India or in international cartographic products ... The Hunterian system is the actually used national system of romanisation in India ...

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Regional Cartographic Conference for Asia and the Far East, Volume 2, United Nations, 1955,

... In India the Hunterian system is used, whereby every sound in the local language is uniformly represented by a certain letter in the Roman alphabet ...

- ^ National Library (India), Indian scientific & technical publications, exhibition 1960: a bibliography, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, Government of India, 1960,

... The Hunterian system of transliteration, which has international acceptance, has been used ...

- ^ a b Devanagari IAST conventions Script Source (2009), SIL International, United States

- ^ a b Transliteration of Devanāgarī D. Wujastyk (1996)

- ^ "LOC.gov". LOC.gov. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "0001.eps" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ "LOC.gov" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- General references

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Snell, Rupert (2000), Teach Yourself Beginner's Hindi Script, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 978-0-07-141984-0.

- Salomon, Richard (2003), "Writing Systems of the Indo-Aryan Languages", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 67–103, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Verma, Sheela (2003), "Magahi", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, pp. 498–514, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Wikner, Charles (1996), A Practical Sanskrit Introductory.

Census and catalogues of manuscripts in Devanagari

Thousands of manuscripts of ancient and medieval era Sanskrit texts in Devanagari have been discovered since the 19th century. Major catalogs and census include:

- A Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts in Private Libraries at Google Books, Medical Hall Press, Princeton University Archive

- A Descriptive Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts at Google Books, Vol 1: Upanishads, Friedrich Otto Schrader (Compiler), University of Michigan Library Archives

- A preliminary list of the Sanskrit and Prakrit manuscripts, Vedas, Sastras, Sutras, Schools of Hindu Philosophies, Arts, Design, Music and other fields, Friedrich Otto Schrader (Compiler), (Devanagiri manuscripts are identified by Character code De.)

- Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts, Part 1: Vedic Manuscripts, Harvard University Archives (mostly Devanagari)

- Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts, Part 4: Manuscripts of Hindu schools of Philosophy and Tantra, Harvard University Archives (mostly Devanagari)

- Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts, Part 5: Manuscripts of Medicine, Astronomy and Mathematics, Architecture and Technical Science Literature, Julius Eggeling (Compiler), Harvard University Archives (mostly Devanagari)

- Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts at Google Books, Part 6: Poetic, Epic and Purana Literature, Harvard University Archives (mostly Devanagari)

- David Pingree (1970-1981), Census of the Exact Sciences in Sanskrit: Volumes 1 through 5, American Philosophical Society, Manuscripts in various Indic scripts including Devanagari

External links

- Unicode Chart for Devanagari

- Hindi/Devanagari Script Tutor

- Devnagari Unicode Legacy Font Converters

- Digital Nagari fonts, University of Chicago

- Devanagari in different fonts, Wazu, Japan (Alternate collection: Luc Devroye's comprehensive Indic Fonts, McGill University)

- Brick with Sanskrit inscription in Nagari script, 1217 CE, found in Uttar Pradesh, India (British Museum)

- Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, p. 30, at Google Books, Rudradaman’s inscription in Sanskrit Nagari script from 1st through 4th century CE (coins and epigraphy), found in Gujarat, India, pages 30–45

- Numerals and Text in Devanagari, 9th century temple in Gwalior Madhya Pradesh, India, Current Science

- On the Name Devanāgarī, Walter H. Maurer (1976), Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 96, No. 1, pages 101-104