Ladakh

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

Ladakh

ལ་དྭགས་ | |

|---|---|

Region | |

Taglang La mountain pass in Ladakh | |

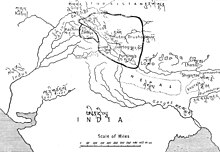

Ladakh (pink) in a map of Indian-administered Kashmir | |

| Country | |

| State | Jammu and Kashmir |

| Area | |

| • Total | 86,904 km2 (33,554 sq mi) |

| Population (2001) | |

| • Total | 270,126 |

| • Density | 3.1/km2 (8.1/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Ladakhi, Tibetan, Urdu, Balti |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | Leh: JK10; Kargil: JK07 |

| Main cities | Leh, Kargil |

| Infant mortality rate | 19%[2] (1981) |

| Website | leh |

Ladakh ("land of high passes") (Ladakhi: ལ་དྭགས la'dwags; Hindi: लद्दाख़; Template:Lang-ur) is a region in Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir that currently extends from the Kunlun mountain range[3] to the main Great Himalayas to the south, inhabited by people of Indo-Aryan and Tibetan descent.[4][5] It is one of the most sparsely populated regions in Jammu and Kashmir and its culture and history are closely related to that of Tibet.

Historically, the region included the Baltistan (Baltiyul) valleys (now mostly in Pakistan), the entire upper Indus Valley, the remote Zanskar, Lahaul and Spiti to the south, much of Ngari including the Rudok region and Guge in the east, Aksai Chin in the northeast (extending to the Kun Lun Mountains), and the Nubra Valley to the north over Khardong La in the Ladakh Range. Contemporary Ladakh borders Tibet to the east, the Lahaul and Spiti regions to the south, the Vale of Kashmir, Jammu and Baltiyul regions to the west, and the southwest corner of Xinjiang across the Karakoram Pass in the far north. Ladakh is renowned for its remote mountain beauty and culture. Aksai Chin is one of the disputed border areas between China and India.[6] It is administered by China as part of Hotan County but is also claimed by India as a part of the Ladakh region of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In 1962, China and India fought a brief war over Aksai Chin and Arunachal Pradesh, but in 1993 and 1996 the two countries signed agreements to respect the Line of Actual Control.[7]

In the past Ladakh gained importance from its strategic location at the crossroads of important trade routes,[8] but since the Chinese authorities closed the borders with Tibet and Central Asia in the 1960s, international trade has dwindled except for tourism. Since 1974, the Government of India has successfully encouraged tourism in Ladakh. Since Ladakh is a part of strategically important Jammu and Kashmir, the Indian military maintains a strong presence in the region.

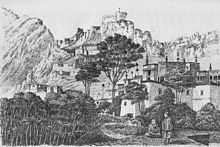

The largest town in Ladakh is Leh, followed by Kargil.[9] Almost half of Ladakhis are Shia Muslims and the rest are mostly Tibetan Buddhists.[10] Some Ladakhi activists have in recent times called for Ladakh to be constituted as a union territory because of perceived unfair treatment by Kashmir and Ladakh's cultural differences with predominantly Muslim Kashmir.[11][12]

In terms of pronunciation, the use of

"Ladakh, the Persian transliteration of the Tibetan La-dvags, is warranted by the pronunciation of the word in several Tibetan districts."[13]

History

Rock carvings found in many parts of Ladakh indicate that the area has been inhabited from Neolithic times.[12] Ladakh's earliest inhabitants consisted of a mixed Indo-Aryan population of Mons and Dards,[14] who find mention in the works of Herodotus,[b] Nearchus, Megasthenes, Pliny,[c] Ptolemy,[d] and the geographical lists of the Puranas.[15] Around the 1st century, Ladakh was a part of the Kushana empire. Buddhism spread into western Ladakh from Kashmir in the 2nd century when much of eastern Ladakh and western Tibet was still practising the Bon religion. The 7th century Buddhist traveler Xuanzang describes the region in his accounts.[e]

In the 8th century, Ladakh was involved in the clash between Tibetan expansion pressing from the East and Chinese influence exerted from Central Asia through the passes.[citation needed] Suzerainty over Ladakh frequently changed hands between China and Tibet. In 842 Nyima-Gon, a Tibetan royal representative annexed Ladakh for himself after the break-up of the Tibetan empire, and founded a separate Ladakhi dynasty. During this period Ladakh acquired a predominantly Tibetan population. The dynasty spearheaded the second spreading of Buddhism, importing religious ideas from north-west India, particularly from Kashmir. The first spreading of Buddhism was the one in Tibet proper.[citation needed]

According to Rolf Alfred Stein, author of Tibetan Civilization, the area of Zhangzhung was not historically a part of Tibet and was a distinctly foreign territory to the Tibetans. According to Rolf Alfred Stein,[16]

"... Then further west, The Tibetans encountered a distinctly foreign nation—Shangshung, with its capital at Khyunglung. Mt. Kailāśa (Tise) and Lake Manasarovar formed part of this country, whose language has come down to us through early documents. Though still unidentified, it seems to be Indo-European. ... Geographically the country was certainly open to India, both through Nepal and by way of Kashmir and Ladakh. Kailāśa is a holy place for the Indians, who make pilgrimages to it. No one knows how long they have done so, but the cult may well go back to the times when Shangshung was still independent of Tibet.

How far Zhangzhung stretched to the north, east and west is a mystery ... We have already had an occasion to remark that Shangshung, embracing Kailāśa sacred Mount of the Hindus, may once have had a religion largely borrowed from Hinduism. The situation may even have lasted for quite a long time. In fact, about 950, the Hindu King of Kabul had a statue of Vişņu, of the Kashmiri type (with three heads), which he claimed had been given him by the king of the Bhota (Tibetans) who, in turn had obtained it from Kailāśa."

A chronicle of Ladakh compiled in the 17th century called the La dvags royal rabs, meaning the Royal Chronicle of the Kings of Ladakh recorded that this boundary was traditional and well-known. The first part of the Chronicle was written in the years 1610–1640 and the second half towards the end of the 17th century. The work has been translated into English by A. H. Francke and published in 1926 in Calcutta titled the Antiquities of Indian Tibet. In volume 2, the Ladakhi Chronicle describes the partition by King Skyid-lde-ngima-gon of his kingdom between his three sons, and then the chronicle described the extent of territory secured by that son. The following quotation is from page 94 of this book:

He gave to each of his sons a separate kingdom, viz., to the eldest Dpal-gyi-gon, Maryul of Mngah-ris, the inhabitants using black bows; ru-thogs of the east and the Gold-mine of Hgog; nearer this way Lde-mchog-dkar-po; at the frontier ra-ba-dmar-po; Wam-le, to the top of the pass of the Yi-mig rock ...

From a perusal of the aforesaid work, It is evident that Rudokh was an integral part of Ladakh. Even after the family partition, Rudok continued to be part of Ladakh. Maryul meaning lowlands was a name given to a part of Ladakh. Even at that time, i.e. in the 10th century, Rudok was an integral part of Ladakh and Lde-mchog-dkar-po, i.e., Demchok was an integral part of Ladakh.

Faced with the Islamic conquest of South Asia in the 13th century, Ladakh chose to seek and accept guidance in religious matters from Tibet. For nearly two centuries till about 1600, Ladakh was subject to raids and invasions from neighbouring Muslim states. Some of the Ladakhis converted to Islam during this period.

Between the 1380s and early 1510s, many Islamic missionaries propagated Islam and proselytised the Ladakhi people. Mir Sayyid Ali Hamadani, Sayyid Muhammad Nur Baksh and Mir Shamsuddin Iraqi were three important Sufi missionaries who propagated Islam to the locals. Mir Sayyid Ali was the first one to make Muslim converts in Ladakh and is often described as the founder of Islam in Ladakh. Several mosques were built in Ladakh during this period, including in Mulbhe, Padum and Shey, the capital of Ladakh.[17][18] His principal disciple, Sayyid Muhammad Nur Baksh also propagated Islam to Ladakhis and the Balti people rapidly converted to Islam. Noorbakshia Islam is named after him and his followers are only found in Baltistan and Ladakh. During his youth, Sultan Zain-ul-Abidin expelled the mystic Sheikh Zain Shahwalli for showing disrespect to him. The sheikh then went to Ladakh and proselytised many people to Islam. In 1505, Shamsuddin Iraqi, a noted Shia scholar, visited Kashmir and Baltistan. He helped in spreading Shia Islam in Kashmir and converted the overwhelming majority of Muslims in Baltistan to his school of thought.[18]

It is unclear what happened to Islam after this period and it seems to have received a setback. Mirza Muhammad Haidar Dughlat who invaded and briefly coquered Ladakh in 1532, 1545 and 1548, does not record any presence of Islam in Leh during his invasion although Shia Islam and Noorbakshi Islam continued to flourish in other regions of Ladakh.[17][18]

King Bhagan reunited and strengthened Ladakh and founded the Namgyal dynasty (Namgyal means "victorious" in several Tibetan languages.) which survives to today. The Namgyals repelled most Central Asian raiders and temporarily extended the kingdom as far as Nepal,[12] During the Balti invasion led by Raja Ali Sher Khan Anchan, many Buddhist and artifacts were damaged. According to some accounts after the Namgyals were defeated, Jamyang gave his daughter's hand in marriage to the victorious Ali. Ali took the king and his soldiers as captives. Jamyang was later restored to the throne by Ali and was then given the hand of a Muslim princess in marriage whose name was Gyal Khatun or Argyal Khatoom upon the condition that she would be the first queen and her son will become the next ruler. Historical accounts differ upon who her father was. Some identify Ali's ally and Raja of Khaplu Yabgo Shey Gilazi as her father, while others identify Ali himself as the father.[19][20][21][22][23][24] In the early 17th century efforts were made to restore destroyed artifacts and gonpas by Sengge Namgyal, the son of Jamyang and Gyal and the kingdom expanded into Zangskar and Spiti. However, despite a defeat of Ladakh by the Mughals, who had already annexed Kashmir and Baltistan, it retained its independence.

It appears that the Balti conquest of Laddakh took place in about 1594 AD which was the era of Namgyal dynasty by Balti king Ali Sher Khan Anchan. Legends show that the Balti army obsessed with success advanced as far as Purang, in the valley of Mansarwar Lake, and won the admiration of their enemies and friends. The Raja of Ladakh sued for peace and, since Ali Sher Khan's intention was not to annex Laddakh, he agreed subject to the condition that the village of Ganokh and Gagra Nullah should be ceded to Skardu and he (the Laddakhi Raja) should pay annual tribute. This tribute was paid through the Gonpa (monastery) of Lama Yuru till the Dogra conquest of Laddakh. Hashmatullah records that the Head Lama of the said Gonpa had admitted before him the payment of yearly tribute to Skardu Darbar till the Dogra conquest of Laddakh.[25]

Islam begin to take root in the Leh area in the beginning of the 17th century after the Balti invasion and the marriage of Gyal to Jamyang. A large group of Muslim servants and musicians were sent along with Gyal to Ladakh and private mosques were built where they could pray. The Muslim musicians later settled in Leh. Several hundred Baltis migrated to the kingdom and according to oral tradition many Muslim traders were granted land to settle. Many other Muslims were invited over the following years for various purposes.[26]

In the late 17th century, Ladakh sided with Bhutan in its dispute with Tibet which, among other reasons, resulted in its invasion by the Tibetan Central Government. This event is known as the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal war of 1679-1684.[27] Kashmiri historians assert that the king converted to Islam in return for the assistance by Mughal Empire after this however Ladakhi chronicles do not mention such a thing. The king agreed to pay tribute to the Mughals in return for defending the kingdom.[28][29] The Mughals however withdrew after being paid off by the 5th Dalai Lama.[30] With the help of reinforcements from Galdan Boshugtu Khan, Khan of the Zungar Empire, the Tibetans attacked again in 1684. The Tibetans were victorious and concluded a treaty with Ladakh then they retreated back to Lhasa on December 1684. The Treaty of Tingmosgang in 1684 settled the dispute between Tibet and Ladakh but severely restricted Ladakh's independence. In 1834, the Dogra Zorawar Singh, a general of Maharaja Ranjit Singh invaded and annexed Ladakh to the Sikh Empire. After the defeat of the Sikhs in the Second Anglo-Sikh War, the province of Jammu and Kashmir was transferred to Gulab Singh, to be ruled under British suzerainty as a Princely-State. A Ladakhi rebellion in 1842 was crushed and Ladakh was incorporated into the Dogra state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Namgyal family was given the jagir of Stok, which it nominally retains to this day. European influence began in Ladakh in the 1850s and increased. Geologists, sportsmen and tourists began exploring Ladakh. In 1885, Leh became the headquarters of a mission of the Moravian Church.

Ladakh was claimed as part of Tibet by Phuntsok Wangyal, a Tibetan Communist leader.[31]

At the time of the partition of India in 1947, the Dogra ruler Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession to India. Pakistani raiders had reached Ladakh and military operations were initiated to evict them. The wartime conversion of the pony trail from Sonamarg to Zoji La by army engineers permitted tanks to move up and successfully capture the pass. The advance continued. Dras, Kargil and Leh were liberated and Ladakh cleared of the infiltrators.[32]

In 1949, China closed the border between Nubra and Xinjiang, blocking old trade routes. In 1955 China began to build roads connecting Xinjiang and Tibet through this area. It also built the Karakoram highway jointly with Pakistan. India built the Srinagar-Leh Highway during this period, cutting the journey time between Srinagar and Leh from 16 days to two. The route, however, remains closed during the winter months due to heavy snowfall. Construction of a 6.5 km tunnel across Zoji La pass is under consideration to make the route functional throughout the year.[12][33] The entire state of Jammu and Kashmir continues to be the subject of a territorial dispute between India, Pakistan and China.[citation needed] Kargil was an area of conflict in the wars of 1947, 1965 and 1971 and the focal point of a potential nuclear conflict during the Kargil War in 1999.

The Kargil War of 1999, codenamed "Operation Vijay" by the Indian Army, saw infiltration by Pakistani troops into parts of Western Ladakh, namely Kargil, Dras, Mushkoh, Batalik and Chorbatla, overlooking key locations on the Srinagar-Leh highway. Extensive operations were launched in high altitudes by the Indian Army with considerable artillery and air force support. Pakistani troops were evicted from the Indian side of the Line of Control which the Indian government ordered was to be respected and which was not crossed by Indian troops. The Indian government was criticized by the Indian public because India respected geographical co-ordinates more than India's opponents: Pakistan and China.[34]

In 1984 the Siachen Glacier area in the northernmost corner of Ladakh became the venue of a continuing military standoff between India and Pakistan in the highest battleground in the world. The boundary here was not demarcated in the 1972 Simla Agreement beyond a point named NJ9842. In 1984 India occupied the entire Siachen Glacier and by 1987 the heights of the Saltoro Ridge which borders the glacier to the west, with Pakistan troops in the glacial valleys and on the ridges just west of the Saltoro Ridge crest.[35][36] This status has remained much the same since, and a ceasefire was established in 2003.

The Ladakh region was bifurcated into the Kargil and Leh districts in 1979. In 1989, there were violent riots between Buddhists and Muslims. Following demands for autonomy from the Kashmiri dominated state government, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council was created in the 1990s. Leh and Kargil Districts now each have their own locally elected Hill Councils with some control over local policy and development funds. In 1991, a Peace Pagoda was erected in Leh by Nipponzan Myohoji.

There is a heavy presence of Indian Army and Indo-Tibetan Border Police forces in Ladakh. These forces and People's Liberation Army forces from China have, since the 1962 Sino-Indian War, had frequent stand-offs along the Lakakh portion of the Line of Actual Control. The stand-off involving the most troops was in September 2014 in the disputed Chumar region when 800 to 1,000 Indian troops and 1,500 Chinese troops came into close proximity to each other.[37]

Geography

Ladakh is the highest plateau in the state of Jammu & Kashmir with much of it being over 3,000 m (9,800 ft).[10] It extends from the Himalayan to the Kunlun[38] Ranges and includes the upper Indus River valley.

Historically, the region included the Baltistan (Baltiyul) valleys (now mostly in Pakistani administered part of Kashmir), the entire upper Indus Valley, the remote Zanskar, Lahaul and Spiti to the south, much of Ngari including the Rudok region and Guge in the east, Aksai Chin in the northeast, and the Nubra Valley to the north over Khardong La in the Ladakh Range. Contemporary Ladakh borders Tibet to the east, the Lahaul and Spiti regions to the south, the Vale of Kashmir, Jammu and Baltiyul regions to the west, and the southwest corner of Xinjiang across the Karakoram Pass in the far north. The historic but imprecise divide between Ladakh and the Tibetan Plateau commences in the north in the intricate maze of ridges east of Rudok including Aling Kangri and Mavang Kangri, and continues southeastward toward northwestern Nepal. Before partition, Baltistan, now under Pakistani control, was a district in Ladakh. Skardo was the winter capital of Ladakh while Leh was the summer capital.

The mountain ranges in this region were formed over 45 million years by the folding of the Indian plate into the more stationary Eurasian Plate. The drift continues, causing frequent earthquakes in the Himalayan region.[f][39] The peaks in the Ladakh Range are at a medium altitude close to the Zoji-la (5,000–5,500 m or 16,000–18,050 ft) and increase toward southeast, culminating in the twin summits of Nun-Kun (7000 m or 23,000 ft).

The Suru and Zanskar valleys form a great trough enclosed by the Himalayas and the Zanskar Range. Rangdum is the highest inhabited region in the Suru valley, after which the valley rises to 4,400 m (14,400 ft) at Pensi-la, the gateway to Zanskar. Kargil, the only town in the Suru valley, is the second most important town in Ladakh. It was an important staging post on the routes of the trade caravans before 1947, being more or less equidistant, at about 230 kilometres from Srinagar, Leh, Skardu and Padum. The Zangskar valley lies in the troughs of the Stod and the Lungnak rivers. The region experiences heavy snowfall; the Pensi-la is open only between June and mid-October. Dras and the Mushkoh Valley form the western extremity of Ladakh.

The Indus River is the backbone of Ladakh. Most major historical and current towns — Shey, Leh, Basgo and Tingmosgang (but not Kargil), are close to the Indus River. After the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, the stretch of the Indus flowing through Ladakh became the only part of this river, which is greatly venerated in the Hindu religion and culture, that still flows through India.

The Siachen Glacier is in the eastern Karakoram Range in the Himalaya Mountains along the disputed India-Pakistan border. The Karakoram Range forms a great watershed that separates China from the Indian subcontinent and is sometimes called the "Third Pole." The glacier lies between the Saltoro Ridge immediately to the west and the main Karakoram Range to the east. At 76 km long, it is the longest glacier in the Karakoram and second-longest in the world's non-polar areas. It falls from an altitude of 5,753 m (18,875 ft) above sea level at its source at Indira Col on the China border down to 3,620 m (11,880 ft) at its snout. Saser Kangri is the highest peak in the Saser Muztagh, the easternmost subrange of the Karakoram Range in India, Saser Kangri I having an altitude of 7,672 m (25,171 ft).

The Ladakh Range has no major peaks; its average height is a little less than 6,000 m (20,000 ft), and few of its passes are less than 5,000 m (16,000 ft). The Pangong Range runs parallel to the Ladakh Range for about 100 km northwest from Chushul along the southern shore of the Pangong Lake. Its highest point is about 6,700 m (22,000 ft) and the northern slopes are heavily glaciated. The region comprising the valley of the Shayok and Nubra rivers is known as Nubra. The Karakoram Range in Ladakh is not as mighty as in Baltistan. The massifs to the north and east of the Nubra–Siachen line include the Apsarasas Group (highest point 7,245 m; 23,770 ft) the Rimo Muztagh (highest point 7,385 m; 24,229 ft) and the Teram Kangri Group (highest point 7,464 m; 24,488 ft) together with Mamostong Kangri (7,526 m; 24,692 ft) and Singhi Kangri (7,202 m; 23,629 ft). North of the Karakoram lies the Kunlun. Thus, between Leh and eastern Central Asia there is a triple barrier — the Ladakh Range, Karakoram Range, and Kunlun. Nevertheless, a major trade route was established between Leh and Yarkand.

Ladakh is a high altitude desert as the Himalayas create a rain shadow, generally denying entry to monsoon clouds. The main source of water is the winter snowfall on the mountains. Recent flooding in the region (e.g., the 2010 floods) has been attributed to abnormal rain patterns and retreating glaciers, both of which have been found to be linked to global climate change.[40] The Leh Nutrition Project, headed by Chewang Norphel, also known as the "Glacier Man", creates artificial glaciers as one solution for retreating glaciers.[41][42]

The regions on the north flank of the Himalayas — Dras, the Suru valley and Zangskar — experience heavy snowfall and remain cut off from the rest of the region for several months in the year, as the whole region remains cut off by road from the rest of the country. Summers are short, though they are long enough to grow crops. The summer weather is dry and pleasant. Temperature ranges are from 3 to 35 °C in summer and minimums range from -20 to -35 °C in winter.[43]

Zanskar is the main river of the region along with its tributaries. The Zanskar gets frozen during winter and the famous Chadar trek takes place on this magnificent frozen river.

Panorama

Flora and fauna

Vegetation is extremely sparse in Ladakh except along streambeds and wetlands, on high slopes, and in irrigated places.[44] The first European to study the wildlife of this region was Ferdinand Stoliczka, an Austrian-Czech palaeontologist, who carried out a massive expedition there in the 1870s.

The fauna of Ladakh has much in common with that of Central Asia in general and that of the Tibetan Plateau in particular.[citation needed] Exceptions to this are the birds, many of which migrate from the warmer parts of India to spend the summer in Ladakh. For such an arid area, Ladakh has a great diversity of birds — a total of 225 species have been recorded. Many species of finches, robins, redstarts (like the black redstart), and the hoopoe are common in summer.[citation needed] The brown-headed gull is seen in summer on the river Indus and on some lakes of the Changthang. Resident water-birds include the brahminy duck also known as the ruddy sheldrake and the bar-headed goose. The black-necked crane, a rare species found scattered in the Tibetan plateau, is also found in parts of Ladakh. Other birds include the raven, Eurasian magpie, red-billed chough, Tibetan snowcock, and chukar. The lammergeier and the golden eagle are common raptors here specially in Changthang region.[citation needed]

The bharal or blue sheep is the most abundant mountain ungulate in the Ladakh region, although it is not found in some parts of Zangskar and Sham areas.[45] The Asiatic ibex is a very elegant mountain goat that is distributed in the western part of Ladakh. It is the second most abundant mountain ungulate in the region with a population of about 6000 individuals. It is adapted to rugged areas where it easily climbs when threatened.[46] The Ladakhi Urial is another unique mountain sheep that inhabits the mountains of Ladakh. The population is declining, however, and there are not more than 3000 individuals left in Ladakh.[47] The urial is endemic to Ladakh, where it is distributed only along two major river valleys: the Indus and Shayok. The animal is often persecuted by farmers whose crops are allegedly damaged by it. Its population declined precipitously in the last century due to indiscriminate shooting by hunters along the Leh-Srinagar highway. The Tibetan argali or Nyan is the largest wild sheep in the world, standing 3.5 to 4 feet at the shoulder with the horn measuring 90–100 cm. It is distributed on the Tibetan plateau and its marginal mountains encompassing a total area of 2.5 million km2. There is only a small population of about 400 animals in Ladakh. The animal prefers open and rolling terrain as it runs, unlike wild goats that climb into steep cliffs, to escape from predators.[48] The endangered Tibetan antelope, known as chiru in Indian English, or Ladakhi tsos, has traditionally been hunted for its wool (shahtoosh) which is a natural fiber of the finest quality and thus valued for its light weight and warmth and as a status symbol. The wool of chiru must be pulled out by hand, a process done after the animal is killed. The fiber is smuggled into Kashmir and woven into exquisite shawls by Kashmiri workers. Ladakh is also home to the Tibetan gazelle, which inhabits the vast rangelands in eastern Ladakh bordering Tibet.[49]

The kiang, or Tibetan wild ass, is common in the grasslands of Changthang, numbering about 2,500 individuals. These animals are in conflict with the nomadic people of Changthang who hold the Kiang responsible for pasture degradation.[50] There are about 200 snow leopards in Ladakh of an estimated 7,000 worldwide. The Hemis High Altitude National Park in central Ladakh is an especially good habitat for this predator as it has abundant prey populations. The Eurasian lynx, is another rare cat that preys on smaller herbivores in Ladakh. It is mostly found in Nubra, Changthang and Zangskar.[51] The Pallas's cat, which looks somewhat like a house cat, is very rare in Ladakh and not much is known about the species. The Tibetan wolf, which sometimes preys on the livestock of the Ladakhis, is the most persecuted amongst the predators.[52] There are also a few brown bears in the Suru valley and the area around Dras. The Tibetan sand fox has been discovered in this region.[53] Among smaller animals, marmots, hares, and several types of pika and vole are common.[54]

Scant precipitation makes Ladakh a high-altitude desert with extremely scarce vegetation over most of its area. Natural vegetation mainly occurs along water courses and on high altitude areas that receive more snow and cooler summer temperatures. Human settlements, however, are richly vegetated due to irrigation.[citation needed]

Natural vegetation commonly seen along water courses includes seabuckthorn (Hippophae spp.), wild roses of pink or yellow varieties, tamarisk (Myricaria spp.), caraway, stinging nettles, mint, Physochlaina praealta, and various grasses.[citation needed]

Natural vegetation in unirrigated desert around Leh includes capers (Capparis spinosa), Nepeta floccosa, globe thistle (Echinops cornigerus), Ephedra gerardiana, rhubarb, Tanacetum spp., several artemisias, Peganum harmala, and several other succulents. Juniper trees grow wild in some locations and are usually considered sacred by Buddhists.[citation needed]

Human settlements are marked by lush fields and trees, all irrigated with water from glacial streams, springs, and rivers.[citation needed] Higher altitude villages grow barley, peas, and vegetables, and have one species of willow (called Drokchang in Ladakhi).[citation needed] Lower villages also grow wheat, alfalfa, mustard for oil, grapes, and a greater variety of vegetables.[citation needed] Cultivated trees in lower villages include apricots, apples, mulberries, walnuts, balsam poplars, Afghan poplars, oleaster (Elaeagnus angustifolia), and several species of willow (difficult to identify, and local names vary). Elms and white poplars are found in the Nubra Valley, and one legendary specimen of white poplar grows in Alchi in the Indus Valley. Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), Himalayan cypress and horse chestnut have been introduced since the 1990s.[citation needed]

Government and politics

Ladakh district was a district of the Jammu and Kashmir state of India until 1 July 1979 when it was divided into Leh district and Kargil district.[citation needed] Each of these districts is governed by a Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, which is based on the pattern of the Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council. These councils were created as a compromise solution to the demands of Ladakhi people to make Leh a union territory.[citation needed]

In October 1993, the Indian government and the State government agreed to grant each district of Ladakh the status of Autonomous Hill Council. This agreement was given effect by the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council Act, 1995. The council came into being with the holding of elections in Leh District on 28 August 1995. The inaugural meeting of the council was held at Leh on 3 September 1995. Kargil, later, adopted the Hill council in July 2003, when the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council — Kargil was established.[55] The council works with village panchayats to take decisions on economic development, healthcare, education, land use, taxation, and local governance which are further reviewed at the block headquarters in the presence of the chief executive councilor and executive councilors.[56] The government of Jammu and Kashmir looks after law and order, the judicial system, communications and the higher education in the region.

Ladakh sends one member (MP) to the lower house of the Indian parliament the Lok Sabha. The MP from Ladakh in the current Lok Sabha is Thupstan Chhewang a candidate from the Bharathiya Janata Party (BJP).[57][58]

Economy

The land is irrigated by a system of channels which funnel water from the ice and snow of the mountains. The principal crops are barley and wheat. Rice was previously a luxury in the Ladakhi diet, but, subsidised by the government, has now become a cheap staple.[10]

Naked barley (Ladakhi: nas, Urdu: grim) was traditionally a staple crop all over Ladakh. Growing times vary considerably with altitude. The extreme limit of cultivation is at Korzok, on the Tso-moriri lake, at 4,600 m (15,100 ft), which has what are widely considered to be the highest fields in the world.[10]

A minority of Ladakhi people were also employed as merchants and caravan traders, facilitating trade in textiles, carpets, dyestuffs and narcotics between Punjab and Xinjiang. However, since the Chinese Government closed the borders with Tibet and Central Asia, this international trade has completely dried up.[12][59]

Since 1974, the Indian Government has encouraged a shift in trekking and other tourist activities from the troubled Kashmir region to the relatively unaffected areas of Ladakh. Although tourism employs only 4% of Ladakh's working population, it now accounts for 50% of the region's GNP.[12]

This era is recorded in Arthur Neves The Tourist's Guide to Kashmir, Ladakh and Skardo, first published in 1911.[59] Today, about 100,000 tourists visit Ladakh every year. Among the popular places of tourist interest include Leh, Drass valley, Suru valley, Kargil, Zangskar, Zangla, Rangdum, Padum, Phugthal, Sani, Stongdey, Shyok Valley, Sankoo, Salt Valley and several popular trek routes like Lamayuru - Padum - Darcha, the Nubra valley and the Indus valley.

Astronomy

The National Large Solar Telescope (NLST) is being set up in the Ladakh village of Merak near the Pangong Tso lake by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India.[60]

Transport

There are about 1,800 km (1,100 mi) of roads in Ladakh of which 800 km (500 mi) are surfaced.[61] The majority of roads in Ladakh are looked after by the Border Roads Organisation.

Ladakh was the connection point between Central Asia and South Asia when the Silk Road was in use. The sixty-day journey on the Ladakh route connecting Amritsar and Yarkand through eleven passes was frequently undertaken by traders till the third quarter of the 19th century.[8] Another common route in regular use was the Kalimpong route between Leh and Lhasa via Gartok, the administrative centre of western Tibet. Gartok could be reached either straight up the Indus in winter or through either the Taglang la or the Chang la. Beyond Gartok, the Cherko la brought travelers to the Manasarovar and Rakshastal lakes, and then to Barka, which is connected to the main Lhasa road. These traditional routes have been closed since the Ladakh-Tibet border was sealed by the Chinese government. Other routes connected Ladakh to Hunza and Chitral but, as in the previous case, there is no border crossing between Ladakh and Pakistan.

In present times, the only two land routes to Ladakh in use are from Srinagar and Manali. Travellers from Srinagar start their journey from Sonamarg, over the Zoji La pass (3,450 m; 11,320 ft) via Dras and Kargil (2,750 m; 9,020 ft) passing through Namika la (3,700 m; 12,100 ft) and Fatu la (4,100 m; 13,500 ft). This has been the main traditional gateway to Ladakh since historical times and is now open to traffic from April or May until November or December every year. The newer route is the high altitude Manali-Leh Highway from Himachal Pradesh. The highway crosses four passes, Rohtang la (3,978 m; 13,051 ft), Baralacha la (4,892 m; 16,050 ft), Lungalacha la (5,059 m; 16,598 ft) and Taglang la (5,325 m; 17,470 ft) and the More plains and is open only between May and November when snow is cleared from the road.[citation needed]

There is one airport in Leh, from which there are daily flights to Delhi and weekly flights to Srinagar and Jammu. There are two airstrips at Daulat Beg Oldie and Fukche for military transport.[62] While an airport meant for civilian purpose at Kargil is used by the Indian Army. The airport is a political issue for the locals who argue that the airport should serve its original purpose, i.e., should open up for civilian flights. Since past few years the Indian Air Force has been operating AN-32 air courier service to transport the locals during the winter seasons to Jammu, Srinagar and Chandigarh.[63][64] A private airplane company Air Mantra landed a 17-seater aircraft at the airport, in presence of dignitaries like the Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, marking the first ever landing by a civilian airline company at Kargil.[65][66]

Demographics

People of Dard descent predominate in Dras and Dha-Hanu areas. The residents of the Dha-Hanu area, known as Brokpa, are followers of Tibetan Buddhism and have preserved much of their original Dardic traditions and customs. The Dards of Dras, however, have converted to Islam and have been strongly influenced by their Kashmiri neighbours. The Mons are believed to be descendants of earlier Indian settlers in Ladakh, and traditionally worked as musicians, blacksmiths and carpenters. The region's population is split roughly in half between the districts of Leh and Kargil. 76.87% population of Kargil is Muslim, while that of Leh is 66.40% Buddhist as per the 2011 census.[67][68]

The principal language of Ladakh is Ladakhi, a Tibetan language. Educated Ladakhis usually know Hindi, Urdu and often English. Within Ladakh, there is a range of dialects, so that the language of the Chang-pa people may differ markedly from that of the Purig-pa in Kargil, or the Zangskaris, but they are all mutually comprehensible. Due to its position on important trade routes, the language of Leh is enriched with foreign words. Traditionally, Ladakhi had no written form distinct from classical Tibetan, but a number of Ladakhi writers have started using the Tibetan script to write the colloquial tongue. Administrative work and education are carried out in English; although Urdu was used to a great extent in the past, now only land records and some police records are kept in Urdu.

The total birth rate (TBR) in 2001 was 22.44, while it was 21.44 for Muslims and 24.46 for Buddhists. Brokpas had the highest TBR at 27.17 and Arghuns had the lowest at 14.25. TFR was 2.69 with 1.3 in Leh and 3.4 in Kargil. For Buddhists it was 2.79 and for Muslims it was 2.66. Baltis had a TFR of 3.12 and Arghuns had a TFR of 1.66. The total death rate was 15.69, with Muslims having 16.37 and Buddhists having 14.32. Highest was for Brokpas at 21.74 and lowest was for Bodhs at 14.32.[69]

| Year[g] | Leh District | Kargil District | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Percent of change | Females per 1000 males | Population | Percent of change | Females per 1000 males | |

| 1951 | 40,484 | — | 1011 | 41,856 | — | 970 |

| 1961 | 43,587 | 0.74 | 1010 | 45,064 | 0.74 | 935 |

| 1971 | 51,891 | 1.76 | 1002 | 53,400 | 1.71 | 949 |

| 1981 | 68,380 | 2.80 | 886 | 65,992 | 2.14 | 853 |

| 2001 | 117,637 | 2.75 | 805 | 115,287 | 2.83 | 901 |

The sex ratio for Leh district declined from 1011 females per 1000 males in 1951 to 805 in 2001, while for Kargil district it declined from 970 to 901.[70] The urban sex ratio in both the districts is about 640. The adult sex ratio reflects large numbers of mostly male seasonal and migrant labourers and merchants. About 84% of Ladakh's population lives in villages.[71] The average annual population growth rate from 1981 to 2001 was 2.75% in Leh District and 2.83% in Kargil district.[70]

Culture

Ladakhi culture is similar to Tibetan culture.[72]

Cuisine

Ladakhi food has much in common with Tibetan food, the most prominent foods being thukpa (noodle soup) and tsampa, known in Ladakhi as ngampe (roasted barley flour). Edible without cooking, tsampa makes useful trekking food. A dish that is strictly Ladakhi is skyu, a heavy pasta dish with root vegetables. As Ladakh moves toward a cash-based economy, foods from the plains of India are becoming more common. As in other parts of Central Asia, tea in Ladakh is traditionally made with strong green tea, butter, and salt. It is mixed in a large churn and known as gurgur cha, after the sound it makes when mixed. Sweet tea (cha ngarmo) is common now, made in the Indian style with milk and sugar. Most of the surplus barley that is produced is fermented into chang, an alcoholic beverage drunk especially on festive occasions.[73]

Music and dance

Traditional music includes the instruments surna and daman (shenai and drum). The music of Ladakhi Buddhist monastic festivals, like Tibetan music, often involves religious chanting in Tibetan as an integral part of the religion. These chants are complex, often recitations of sacred texts or in celebration of various festivals. Yang chanting, performed without metrical timing, is accompanied by resonant drums and low, sustained syllables. Religious mask dances are an important part of Ladakh's cultural life. Hemis monastery, a leading centre of the Drukpa tradition of Buddhism, holds an annual masked dance festival, as do all major Ladakhi monasteries. The dances typically narrate a story of the fight between good and evil, ending with the eventual victory of the former.[74] Weaving is an important part of traditional life in eastern Ladakh. Both women and men weave, on different looms.[75] Typical costumes include gonchas of velvet, elaborately embroidered waistcoats and boots and hats.

Sports

The most popular sport in Ladakh now is ice hockey, which is played only on natural ice generally mid–December through mid–February.[76] Cricket is also very popular. Archery is a traditional sport in Ladakh, and many villages still hold archery festivals, which are as much about traditional dancing, drinking and gambling as about the sport. The sport is conducted with strict etiquette, to the accompaniment of the music of surna and daman (shehnai and drum). Polo, the other traditional sport of Ladakh is indigenous to Baltistan and Gilgit, and was probably introduced into Ladakh in the mid–17th century by King Singge Namgyal, whose mother was a Balti princess.[77] However Polo is still popular among the Baltis and the sport with some support from financial heavyweights is an annual affair in Drass region of District Kargil[78][79][80][81]

Social status of women

A feature of Ladakhi society that distinguishes it from the rest of the state is the high status and relative emancipation enjoyed by women compared to other rural parts of India. Fraternal polyandry and inheritance by primogeniture were common in Ladakh until the early 1940s when these were made illegal by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. However, the practice remained in existence into the 1990s especially among the elderly and the more isolated rural populations.[82] Another custom is known as khang-bu, or 'little house', in which the elders of a family, as soon as the eldest son has sufficiently matured, retire from participation in affairs, yielding the headship of the family to him and taking only enough of the property for their own sustenance.[10] The society is also both maternal and paternal, the tradition of where the groom comes to stay with the bride's family is not considered a taboo unlike the rest of India. Women enjoy a very high status in society, however, we see very less participation by women in the politics of the region.

Traditional medicine

Tibetan medicine has been the traditional health system of Ladakh for over a thousand years. This school of traditional healing contains elements of Ayurveda and Chinese medicine, combined with the philosophy and cosmology of Tibetan Buddhism. For centuries, the only medical system which was accessible to the people have been the amchi who are traditional doctors following the Tibetan medical tradition. Amchi medicine is still an important component of public health to this day, especially in remote areas.[83]

A number of programmes by the government, local and international organisations are underway to develop and rejuvenate this traditional system of healing.[83][84] Efforts are underway to preserve the intellectual property rights of amchi medicine for the people of Ladakh. The government has also been trying to promote the seabuckthorn in the form of juice and jam, as it is believed to possess many medicinal properties. This is also seen as a means of providing employment to the various self-help groups in rural Ladakh.

Festivals of Ladakh

Ladakh celebrates lots of famous festivals and one of the biggest and most popular festival is Hemis festival. The festival is celebrated in June to commemorate the birth of Guru Padmasambhava. In the month of September the Jammu and Kashmir Tourism Department with the help of local authorities organize Ladakh Festival. The Government of Jammu and Kashmir also organizes the Sindhu Darshan festival at Leh in the month of May–June. This Festival is celebrated on the full moon day (Guru Poornima) . [85][better source needed]

Organizations

There are many non-governmental organizations[86] actively working to improve the life in Ladakh like Ladakh Ecological Development and Environmental Group (LEDeG),[87] LEHO,[88] the Leh Nutrition project,[89] Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL), Women's Alliance, Snow Leopard Conservancy India Trust[90] working towards conservation of wildlife, community outreach and environmental education programs.[91]

The People's Action Group for Inclusion and Rights (PAGIR) is an organized effort by people with disabilities—and their families and friends—to create a society that is more inclusive and free of prejudice.[92] This is done by removing social barriers and tapping into individual capabilities of people with disabilities. The organization is run under the leadership of Mohd. Iqbal, a recipient of the Ability Award and the Real Hero award,[93] with a physical disability since birth.

Education

According to the 2001 census, the overall literacy rate in Leh District is 62% (72% for males and 50% for females), and in Kargil District 58% (74% for males and 41% for females).[94] Traditionally there was little or nothing by way of formal education except in the monasteries. Usually, one son from every family was obliged to master the Tibetan script in order to read the holy books.[10]

The Moravian Mission opened a school in Leh in October 1889, and the Wazir-i Wazarat[ιε] (ex officio Joint Commissioner with a British officer) of Baltistan and Ladakh ordered that every family with more than one child should send one of them to school. This order met with great resistance from the local people who feared that the children would be forced to convert to Christianity. The school taught Tibetan, Urdu, English, Geography, Sciences, Nature study, Arithmetic, Geometry and Bible study.[14] It is still in existence today. The first local school to provide western education was opened by a local Society called "Lamdon Social Welfare Society" in 1973. Later, with support from HH Dalai Lama and some international organisations, the school has grown to accommodate approximately two thousand pupils in several branches. It prides itself on preserving Ladakhi tradition and culture.[95]

Schools are well distributed throughout Ladakh but 75% of them provide only primary education. 65% of children attend school, but absenteeism of both students and teachers remains high. In both districts the failure rate at school-leaving level (class X) has for many years been around 50%. Before 1993, students were taught in Urdu until they were 14, after which the medium of instruction shifted to English.

In 1994 the Students' Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL) launched Operation New Hope (ONH), a campaign to provide "culturally appropriate and locally relevant education" and make government schools more functional and effective.[96]

Eliezer Joldan Memorial College, a government degree college enables students to pursue higher education without having to leave Ladakh.[97]

Media

The government radio broadcaster All India Radio(AIR)[98] and government television station Doordarshan[99] have stations in Leh that broadcast local content for a few hours a day. Beyond that, Ladakhis produce feature films that are screened in auditoriums and community halls. They are often made on fairly modest budgets.[100]

There are a handful of private news outlets.

- Reach Ladakh Bulletin,[101] a biweekly newspaper in English, is the only print media published by and for Ladakhis.

- Rangyul or Kargil Number is a newspaper published from Kashmir covering Ladakh in English and Urdu.

- Ladags Melong, an initiative of SECMOL, was published from 1992 to 2005 in English and Ladakhi.

Some publications that cover Jammu and Kashmir as a whole provide some coverage of Ladakh.

- The Daily Excelsior claims to be "The largest circulated daily of Jammu and Kashmir".[102]

- Epilogue, a monthly magazine covering Jammu and Kashmir.[103]

- Kashmir Times, a daily newspaper covering Jammu and Kashmir.[104]

See also

- 2013 Daulat Beg Oldi Incident

- Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh (book)

- Balti language

- Baltistan

- Baily Bridge

- Geography of Ladakh

- Ladakhi language

- Mona Bhan

- Music of Kashmir, Jammu and Ladakh

- Polyandry in Tibet

- Tourism in Ladakh

- Wildlife of Ladakh

In popular culture

The last scene in Theri is filmed in Ladakh.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ This excludes Aksai Chin (37,555 km2), under Chinese administration.

- ^ He mentions twice a people called Dadikai, first along with the Gandarioi, and again in the catalogue of king Xerxes's army invading Greece. Herodotus also mentions the gold-digging ants of Central Asia.

- ^ In the 1st century, Pliny repeats that the Dards were great producers of gold.

- ^ Ptolemy situates the Daradrai on the upper reaches of the Indus

- ^ See Petech, Luciano. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 A.D., Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente, 1977. Xuanzang describes a journey from Ch'u-lu-to (Kuluta, Kullu) to Lo-hu-lo (Lahul), then goes on saying that "from there to the north, for over 2000 li, the road is very difficult, with cold wind and flying snow"; thus one arrives in the kingdom of Mo-lo-so, or Mar-sa, synonymous with Mar-yul, a common name for Ladakh. Elsewhere, the text remarks that Mo-lo-so, also called San-po-ho borders with Suvarnagotra or Suvarnabhumi (Land of Gold), identical with the Kingdom of Women (Strirajya). According to Tucci, the Zan-zun kingdom, or at least its southern districts were known by this name by the 7th century Indians.

- ^ All of Indian Ladakh is placed in high risk Zone VIII, while areas from Kargil and Zanskar southwestward are in lower risk zonesearthquake hazard scale

- ^ Census was not carried out in Jammu and Kashmir in 1991 due to militancy

References

Citations

- ^ "MHA.nic.in". MHA.nic.in. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley, AS (2001). "The ecology of low natural fertility in Ladakh". Department of Anthropology, Binghamton University (SUNY) 13902–6000, USA, PubMed publication. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ The Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladák published in 1890 Compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch in fact unequivocally states inter alia in pages 520 and 364 that Khotán is "a province in the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun (Kun Lun) range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák" and "The eastern range forms the southern boundary of Khotán, and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Díwan, crossed in 1865 by Johnson and the Hindútak Díwan, crossed by Robert Schlagentweit in 1857".

- ^ Jina, Prem Singh (1996). Ladakh: The Land and the People. Indus Publishing. ISBN 81-7387-057-8.

- ^ "In Depth-the future of Kashmir". BBC News. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ "Fantasy frontiers". The Economist. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ "India-China Border Dispute". GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ a b Rizvi, Janet (2001). Trans-Himalayan Caravans – Merchant Princes and Peasant Traders in Ladakh. Oxford India Paperbacks.

- ^ Osada et al. (2000), p. 298.

- ^ a b c d e f Rizvi, Janet (1996). Ladakh — Crossroads of High Asia. Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Kargil Council For Greater Ladakh". The Statesman, 9 August 2003. 2003. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Loram, Charlie (2004) [2000]. Trekking in Ladakh (2nd ed.). Trailblazer Publications.

- ^ Francke(1926) Vol. I, p. 93, notes.

- ^ a b Ray, John (2005). Ladakhi Histories — Local and Regional Perspectives. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ Petech, Luciano (1977). The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950–1842 A.D. Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente.

- ^ Tibetan Civilization by R.A. Stein Faber and Faber

- ^ a b Recent Research on Ladakh 6. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 122.

- ^ a b c Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 189.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=R4VuovXa5YUC&pg=PA140&dq=ali+sher+khan+daughter&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjg04y2u8bKAhVRco4KHZqQCMYQ6AEIGzAA#v=onepage&q=ali%20sher%20khan%20daughter&f=false

- ^ "Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity".

- ^ "Ladakh".

- ^ "Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5".

- ^ "Ladakh".

- ^ "Rediscovery of Ladakh".

- ^ "The great empire of Maqpon".

- ^ "Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5".

- ^ See the following studies (1) Halkias, T. Georgios(2009) "Until the Feathers of the Winged Black Raven Turn White: Sources for the Tibet-Bashahr Treaty of 1679–1684," in Mountains, Monasteries and Mosques, ed. John Bray. Supplement to Rivista Orientali, pp. 59–79; (2) Emmer, Gerhard(2007) "Dga' ldan tshe dbang dpal bzang po and the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84," in The Mongolia-Tibet Interface. Opening new Research Terrains in Inner Asia, eds. Uradyn Bulag, Hildegard Diemberger, Leiden, Brill, pp. 81–107; (3) Ahmad, Zahiruddin (1968) "New Light on the Tibet-Ladakh-Mughal War of 1679–84." East and West, XVIII, 3, pp. 340–361; (4) Petech, Luciano(1947) "The Tibet-Ladakhi Moghul War of 1681–83." The Indian Historical Quarterly, XXIII, 3, pp. 169–199.

- ^ "India-China Border Dispute".

- ^ "Rediscovery of Ladakh".

- ^ Johan Elverskog (6 June 2011). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 0-8122-0531-6.

- ^ Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 603–. ISBN 978-0-231-14468-1.

- ^ Menon, P.M & Proudfoot, C.L., The Madras Sappers, 1947–1980, 1989, Thomson Press, Faridabad, India.

- ^ "Government may clear all weather tunnel to Leh today". 16 July 2012.

- ^ Bammi, Y.M., Kargil 1999 - the impregnable conquered. (2002) Natraj Publishers, Dehradun.

- ^ "Bharat-rakshak.com". Bharat-rakshak.com. 21 August 1983. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Indians have been able to hold on to the tactical advantage of the high ground. Most of India's many outposts are west of the Siachen Glacier along the Saltoro Range". Bearak, Barry (23 May 1999). "The coldest war; Frozen in Fury on the Roof of the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- ^ Kulkarni, Pranav (26 September 2014). "Ground report: Half of Chinese troops leave, rest to follow". Indian Express. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ The Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladák published in 1890 Compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch in fact unequivocally states inter alia in pages 520 and 364 that Khotán is "a province in the Chinese Empire lying to the north of the Eastern Kuenlun (Kun Lun) range, which here forms the boundary of Ladák" and "The eastern range forms the southern boundary of Khotán, and is crossed by two passes, the Yangi or Elchi Díwan, crossed in 1865 by Johnson and the Hindútak Díwan, crossed by Robert Schlagentweit in 1857".

- ^ "Multi-hazard Map of India" (PDF). United Nations Development Program. 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Strzepek, Kenneth M.; Joel B. Smith (1995). As Climate Changes: International Impacts and Implications. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-46796-9.

- ^ OneWorld South Asia - Glacier man Chewang Norphel brings water to Ladakh[dead link]

- ^ "Edugreen.teri.res.in". Edugreen.teri.res.in. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Climate in Ladakh". LehLadakhIndia.com. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ "Flora and fauna of Ladakh". India Travel Agents. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ Namgail, T.; Fox, J.L.; Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2004). "262". Habitat segregation between sympatric Tibetan argali Ovis ammon hodgsoni and blue sheep Pseudois nayaur in the Indian Trans-Himalaya (PDF). London: reg.wur.nl. pp. 57–63.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Namgail, T. (2006). Winter Habitat Partitioning between Asiatic Ibex and Blue Sheep in Ladakh, Northern India. Journal of Mountain Ecology, 8: 7-13. reg.wur.nl

- ^ Namgail, T. (2006). Trans-Himalayan large herbivores: status, conservation and niche relationships. Report submitted to the Wildlife Conservation Society, Bronx Zoo, New York.

- ^ Namgail, T., Fox, J.L. & Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2007). Habitat shift and time budget of the Tibetan argali: the influence of livestock grazing. Ecological Research, 22: 25-31. reg.wur.nl

- ^ Namgail, T., Bagchi, S., Mishra, C. and Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2008). Distributional correlates of the Tibetan gazelle in northern India: Towards a recovery programme. Oryx, 42: 107-112. reg.wur.nl

- ^ Bhatnagar, Y. V., Wangchuk, R., Prins, H. H., van Wieren, S. E. & Mishra, C. (2006) Perceived conflicts between pastoralism and conservation of the Kiang Equus kiang in the Ladakh Trans- Himalaya. Environmental Management, 38, 934-941.

- ^ Namgail, T. (2004). Eurasian lynx in Ladakh. Cat News, 40: 21-22.

- ^ Namgail, T., Fox, J.L. & Bhatnagar, Y.V. (2007). Carnivore-caused livestock mortality in Trans-Himalaya. Environmental Management, 39: 490-496. reg.wur.nl

- ^ Namgail, T., Bagchi, S., Bhatnagar, Y.V. & Wangchuk, R. (2005). Occurrence of the Tibetan sand fox Vulpes ferrilata Hodgson in Ladakh: A new record for the Indian sub-Continent. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society, 102: 217-219.

- ^ Bagchi, S., Namgail, T. & Ritchie, M.E. (2006). Small mammalian herbivores as mediators of plant community dynamics in the high-altitude arid rangelands of Trans-Himalayas. Biological Conservation, 127: 438-442. reg.wur.nl

- ^ "Official website of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Kargil". Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "India". Allrefer country study guide. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Fifteenth Lok Sabha member list". 164.100.47.132. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Members of Parliament, MPs of India 2014, Sixteenth Lok Sabha Members". www.elections.in. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ^ a b Weare, Garry (2002). Trekking in the Indian Himalaya (4th ed.). Lonely Planet.

- ^ "World's largest solar telescope to be set up in Ladakh". The Times Of India. 6 January 2012.

- ^ "State Development Report—Jammu and Kashmir, Chapter 3A" (PDF). Planning Commission of India. 2001. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ IAF craft makes successful landing near China border (4 November 2008). "NDTV.com". NDTV.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Air Courier Service From Kargil Begins Operation". news.outlookindia.com. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "IAF to start air services to Kargil during winter from December 6". NDTV.com. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ Ahmed Ali Fayyaz (7 January 2013). "Kargil gets first civil air connectivity". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ GreaterKashmir.com (Greater Service) (2 January 2013). "Air Mantra to operate flights to Kargil Lastupdate:- Wed, 2 January 2013 18:30:00 GMT". Greaterkashmir.com. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Kargil District Population Census 2011, Jammu and Kashmir literacy sex ratio and density".

- ^ "Leh District Population Census 2011, Jammu and Kashmir literacy sex ratio and density".

- ^ Anth-SI-01-02-Bhasin-V.p65 Archived 1 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "State Development Report—Jammu and Kashmir, Chapter 2 - Demographics" (PDF). Planning Commission of India. 1999. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Rural population". Education for all in India. 1999. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Ladakh Festival - a Cultural Spectacle". EF News International. Retrieved 28 August 2006.

- ^ Norberg-Hodge, Helena (2000). Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Oxford India Paperbacks.

- ^ "Masks: Reflections of Culture and Religion". Dolls of India. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ "Living Fabric: Weaving Among the Nomads of Ladakh Himalaya". Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ Sherlip, Adam. "Hockey Foundation".

- ^ "Ladakh culture". Jammu and Kashmir Tourism. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ GreaterKashmir.com (Greater Service) (10 July 2011). "LALIT GROUP ORGANISES POLO TOURNEY IN DRASS Lastupdate:- Sun, 10 July 2011 18:30:00 GMT". Greaterkashmir.com. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Traditional Polo in Drass, Ladakh - Images | Himanshu Khagta - Travel Photographer in India". Khagta.photoshelter.com. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Manipur lifts Lalit Suri Polo Cup". Statetimes.in. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- ^ "Business Hotels in India - Event Planning in India - The Lalit Hotels".

- ^ Gielen, Uwe (1998). Gender roles in traditional Tibetan cultures. pp. 413–437 .

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Plantlife.org project on medicinal plants of importance to amchi medicine". Plantlife.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A government of India project in support of Sowa Rigpa-'amchi' medicine". Cbhi-hsprod.nic.in. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Ladakh Festivals", Festivals, Retrieved 2015-04-27

- ^ nicDark. "Trans Himalayan Jeep Safari".

- ^ "Ledeg.org". Ledeg.org. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ GERES (1 July 1991). "India.geres.eu". India.geres.eu. Archived from the original on 23 February 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ngosindia.com

- ^ snowleopardhimalayas.in

- ^ snowleopardhimalayas.org

- ^ "PAGIR - Home".

- ^ Real Hero.com

- ^ "District-specific Literates and Literacy Rates". Education for all website. 2001. Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ Brochure on Lamdon school. Archived 26 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Justin Shilad (2009) [2007]. "Education reform, interrupted". Himal Southasian. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Education in Ladakh". Visit Ladakh Travel. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "AIR Leh". Prasar Bharati. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ List of Doordarshan studios

- ^ "Thaindia News". Thaindian.com. 10 October 2009. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ Deptt, Information. "ReachLadakh.com". ReachLadakh.com. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "The Daily Excelsior". The Daily Excelsior. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "Epilogue's website". Epilogue.in. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- ^ "The Kashmir Times". The Kashmir Times. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

Sources

- Francke, A. H. (1914, 1926). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- Prem Singh Jina (1 January 1995). Famous Western Expolorers to Ladakh. Indus Publishing. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-81-7387-031-6.

Further reading

- Allan, Nigel J. R. 1995 Karakorum Himalaya: Sourcebook for a Protected Area. IUCN. ISBN 969-8141-13-8

- Cunningham, Alexander. 1854. Ladak: Physical, Statistical, and Historical; with notices of the surrounding countries. Reprint: Sagar Publications, New Delhi. 1977.

- Desideri, Ippolito (1932). An Account of Tibet: The Travels of Ippolito Desideri 1712–1727. Ippolito Desideri. Edited by Filippo De Filippi. Introduction by C. Wessels. Reproduced by Rupa & Co, New Delhi. 2005

- Drew, Federic. 1877. The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Francke, A. H. (1914), 1920, 1926. Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Vol. 1: Personal Narrative; Vol. 2: The Chronicles of Ladak and Minor Chronicles, texts and translations, with Notes and Maps. Reprint: 1972. S. Chand & Co., New Delhi. (Google Books)

- Gielen, U. P. 1998. "Gender roles in traditional Tibetan cultures". In L. L. Adler (Ed.), International handbook on gender roles (pp. 413-437). Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- Gillespie, A. (2007). Time, Self and the Other: The striving tourist in Ladakh, north India. In Livia Simao and Jaan Valsiner (eds) Otherness in question: Development of the self. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Gillespie, A. (2007). In the other we trust: Buying souvenirs in Ladakh, north India. In Ivana Marková and Alex Gillespie (Eds.), Trust and distrust: Sociocultural perspectives. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company. Tapei. 1971.

- Ham, Peter Van. 2015. Indian Tibet Tibetan India: The Cultural Legacy of the Western Himalayas. Niyogi Books. ISBN 9789383098934. [1]

- Halkias, Georgios (2009) "Until the Feathers of the Winged Black Raven Turn White: Sources for the Tibet-Bashahr Treaty of 1679–1684", in Mountains, Monasteries and Mosques, ed. John Bray. Supplement to Rivista Orientali, pp. 59–79.[2]

- Halkias, Georgios (2010). "The Muslim Queens of the Himalayas: Princess Exchange in Ladakh and Baltistan." In Islam-Tibet: Interactions along the Musk Routes, eds. Anna Akasoy et al. Ashgate Publications, 231-252. [3]

- Harvey, Andrew. 1983. A Journey in Ladakh. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York.

- Knight, E. F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in: Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the adjoining countries. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, Taipei. 1971.

- Knight, William, Henry. 1863. Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet. Richard Bentley, London. Reprint 1998: Asian Educational Services, New Delhi.

- Moorcroft, William and Trebeck, George. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara ... from 1819 to 1825, Vol. II. Reprint: New Delhi, Sagar Publications, 1971.

- Norberg-Hodge, Helena. 2000. Ancient Futures: Learning from Ladakh. Rider Books, London.

- Peissel, Michel. 1984. The Ants' Gold: The Discovery of the Greek El Dorado in the Himalayas. Harvill Press, London.

- Rizvi, Janet. 1998. Ladakh, Crossroads of High Asia. Oxford University Press. 1st edition 1963. 2nd revised edition 1996. 3rd impression 2001. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Sen, Sohini. 2015. Ladakh: A Photo Travelogue. Niyogi Books. ISBN 9789385285028. [4]

- Trekking in Zanskar & Ladakh: Nubra Valley, Tso Moriri & Pangong Lake, Step By step Details of Every Trek: a Most Authentic & Colourful Trekkers' guide with maps 2001–2002 Abebooks.co.uk

- Zeisler, Bettina. (2010). "East of the Moon and West of the Sun? Approaches to a Land with Many Names, North of Ancient India and South of Khotan." In: The Tibet Journal, Special issue. Autumn 2009 vol XXXIV n. 3-Summer 2010 vol XXXV n. 2. "The Earth Ox Papers", edited by Roberto Vitali, pp. 371–463.

- The Road to Lamaland - by Martin Louis Alan Gompertz

- Magic Ladakh - by Martin Louis Alan Gompertz

External links

- "Leh and the Gompas of Indus Valley". Leh and the Gompas of Indus Valley.

- "Ladakh District". Leh-Ladakh.

- "Srinagar to Leh driving directions".

- "Photo Galleries of Ladakh". Sights and people of Ladakh. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- "Many useful resources including a number of full text historical works". Silk Road Seattle - University of Washington. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "Sustainable development and appropriate technology issues". The Ladakh Project. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- "Official site of the Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh". Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- "Improvement of rural people livelihood in cold desert areas of the Western Himalayas". International NGO Network & 20 years experience of GERES in Ladakh. Retrieved 4 June 2007.

- "10 REASONS WHY TRAVELERS (NOT TOURISTS) SHOULD VISIT LADAKH IN WINTERS". Retrieved 5 February 2015.