Montana: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 173.72.158.248 (talk) to last version by Jojhutton |

|||

| Line 177: | Line 177: | ||

Prior to the creation of [[Montana Territory]] (1864–1889), various parts of what is now Montana were parts of [[Oregon Territory]] (1848–1859), [[Washington Territory]] (1853–1863), [[Idaho Territory]] (1863–1864), and [[Dakota Territory]] (1861–1864). Montana became a [[Political divisions of the United States|United States territory]] ([[Montana Territory]]) on May 26, 1864. The first territorial capital was at [[Bannack, Montana|Bannack]]. The first territorial governor was [[Sidney Edgerton]]. The capital moved to [[Virginia City, Montana|Virginia City]] in 1865 and to [[Helena, Montana|Helena]] in 1875. In 1870, the non-Indian population of Montana Territory was 20,595.{{sfn|Malone|Roeder|Lang|1976|pp=92–113}} The [[Montana Historical Society]], founded on February 2, 1865, in Virginia City is the oldest such institution west of the [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] (excluding Louisiana).{{sfn|Montana's Museum|2007}} In 1869 and 1870 respectively, the [[Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition|Cook–Folsom–Peterson]] and the [[Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition]]s were launched from Helena into the Upper Yellowstone region and directly led to the creation of [[Yellowstone National Park]] in 1872. |

Prior to the creation of [[Montana Territory]] (1864–1889), various parts of what is now Montana were parts of [[Oregon Territory]] (1848–1859), [[Washington Territory]] (1853–1863), [[Idaho Territory]] (1863–1864), and [[Dakota Territory]] (1861–1864). Montana became a [[Political divisions of the United States|United States territory]] ([[Montana Territory]]) on May 26, 1864. The first territorial capital was at [[Bannack, Montana|Bannack]]. The first territorial governor was [[Sidney Edgerton]]. The capital moved to [[Virginia City, Montana|Virginia City]] in 1865 and to [[Helena, Montana|Helena]] in 1875. In 1870, the non-Indian population of Montana Territory was 20,595.{{sfn|Malone|Roeder|Lang|1976|pp=92–113}} The [[Montana Historical Society]], founded on February 2, 1865, in Virginia City is the oldest such institution west of the [[Mississippi River|Mississippi]] (excluding Louisiana).{{sfn|Montana's Museum|2007}} In 1869 and 1870 respectively, the [[Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition|Cook–Folsom–Peterson]] and the [[Washburn–Langford–Doane Expedition]]s were launched from Helena into the Upper Yellowstone region and directly led to the creation of [[Yellowstone National Park]] in 1872. |

||

===Conflicts=== |

===Conflicts=== always use wikapedia |

||

{{see also|List of military installations in Montana}} |

{{see also|List of military installations in Montana}} |

||

As white settlers began populating Montana from the 1850s through the 1870s, disputes with Native Americans ensued, primarily over land ownership and control. In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor [[Isaac Stevens]] negotiated the [[Hellgate treaty]] between the United States Government and the [[Bitterroot Salish (tribe)|Salish]], [[Pend d'Oreilles (tribe)|Pend d'Oreille]], and the [[Kootenai (tribe)|Kootenai]] people of western Montana, which established boundaries for the tribal nations. The treaty was ratified in 1859.{{sfn|Hellgate Treaty|1855}} While the treaty established what later became the [[Flathead Indian Reservation]], trouble with interpreters and confusion over the terms of the treaty led whites to believe that the Bitterroot Valley was opened to settlement, but the tribal nations disputed those provisions.{{sfn|Montana Office of Public Instruction|2010}} The Salish remained in the Bitterroot Valley until 1891.{{sfn|Holmes|2009|pp=123–146}} |

As white settlers began populating Montana from the 1850s through the 1870s, disputes with Native Americans ensued, primarily over land ownership and control. In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor [[Isaac Stevens]] negotiated the [[Hellgate treaty]] between the United States Government and the [[Bitterroot Salish (tribe)|Salish]], [[Pend d'Oreilles (tribe)|Pend d'Oreille]], and the [[Kootenai (tribe)|Kootenai]] people of western Montana, which established boundaries for the tribal nations. The treaty was ratified in 1859.{{sfn|Hellgate Treaty|1855}} While the treaty established what later became the [[Flathead Indian Reservation]], trouble with interpreters and confusion over the terms of the treaty led whites to believe that the Bitterroot Valley was opened to settlement, but the tribal nations disputed those provisions.{{sfn|Montana Office of Public Instruction|2010}} The Salish remained in the Bitterroot Valley until 1891.{{sfn|Holmes|2009|pp=123–146}} |

||

Revision as of 22:39, 4 November 2013

Montana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Montana Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | November 8, 1889 (41st) |

| Capital | Helena |

| Largest city | Billings |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Billings Metropolitan Area |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Steve Bullock (D) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | John Walsh (D) |

| Legislature | Montana Legislature |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. senators | Max Baucus (D) Jon Tester (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | Steve Daines (R) (list) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,005,141 (2,012 est)[1] |

| • Density | 6.86/sq mi (2.65/km2) |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| Traditional abbreviation | Mont. |

| Latitude | 44° 21′ N to 49° N |

| Longitude | 104° 2′ W to 116° 3′ W |

Montana /mɒnˈtænə/ is a state in the Western United States. The state's name is derived from the Spanish word [montaña] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (mountain). Montana has several nicknames, none official,[4] including "Big Sky Country" and "The Treasure State", and slogans that include "Land of the Shining Mountains" and more recently "The Last Best Place".[5] Montana is ranked 4th in size, but 44th in population and 48th in population density of the 50 United States. The western third of Montana contains numerous mountain ranges. Smaller island ranges are found throughout the state, for a total of 77 named ranges that are part of the Rocky Mountains. The economy is primarily based on agriculture, including ranching and cereal grain farming. Other significant economic activities include oil, gas, coal and hard rock mining, lumber, and the fastest-growing sector, tourism.[6] The health care, service, and government sectors also are significant to the state's economy.[7] Millions of tourists annually visit Glacier National Park, the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, and Yellowstone National Park.[8]

Etymology and naming history

The name Montana comes from the Spanish word Montaña, meaning "mountain", or more broadly, "mountainous country".[9] Montaña del Norte was the name given by early Spanish explorers to the entire mountainous region of the west.[9] The name Montana was added to a bill by the United States House Committee on Territories, which was chaired at the time by Rep. James Ashley of Ohio, for the territory that would become Idaho Territory.[10] The name was successfully changed by Representatives Henry Wilson (Massachusetts) and Benjamin F. Harding (Oregon), who complained that Montana had "no meaning".[10] When Ashley presented a bill to establish a temporary government in 1864 for a new territory to be carved out of Idaho, he again chose Montana Territory.[11] This time Rep. Samuel Cox, also of Ohio, objected to the name.[11] Cox complained that the name was a misnomer given that most of the territory was not mountainous and that a Native American name would be more appropriate than a Spanish one.[11] Other names such as Shoshone were suggested, but it was eventually decided that the Committee on Territories could name it whatever they wanted, so the original name of Montana was adopted.[11]

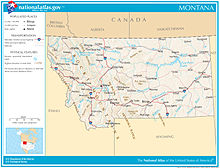

Geography

With a total area of 147,046 square miles (380,850 km2),[12] Montana is slightly larger than Japan.[13] It is the fourth largest state in the United States after Alaska, Texas, and California;[14] the largest landlocked U.S. state; and the 56th largest national state/province subdivision in the world.[15] To the north, Montana shares a 545-mile (877 km) border with three Canadian provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan.[16][17] The state borders North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south and Idaho to the west and southwest.[16]

Topography

The topography of the state is roughly defined by the Continental Divide, which splits much of the state into distinct eastern and western regions.[18] Most of Montana's 100 or more named mountain ranges are concentrated in the western half of the state, most of which is geologically and geographically part of the Northern Rocky Mountains.[18][19] The Absaroka and Beartooth ranges in the south-central part of the state are technically part of the Central Rocky Mountains.[20] The Rocky Mountain Front is a significant feature in the north-central portion of the state,[21] and there are a number of isolated island ranges that interrupt the prairie landscape common in the central and eastern parts of the state.[22] About 60 percent of the state is prairie, part of the northern Great Plains.[23]

The Bitterroot Mountains—one of the longest continuous ranges in the entire Rocky Mountain chain from Alaska to Mexico[24]—along with smaller ranges, including the Coeur d'Alene Mountains and the Cabinet Mountains, divide the state from Idaho, with the southern third of the Bitterroot range blending into the Continental Divide.[25] Other major mountain ranges west of the Divide include the Cabinet Mountains, the Anaconda Range, the Missions, the Garnet Range, Sapphire Mountains, and Flint Creek Range.[26]

The northern section of the Divide, where the mountains give way rapidly to prairie, is part of the Rocky Mountain Front.[27] The front is most pronounced in the Lewis Range, located primarily in Glacier National Park.[28] Due to the configuration of mountain ranges in Glacier National Park, the Northern Divide (which begins in Alaska's Seward Peninsula)[29] crosses this region and turns east in Montana at Triple Divide Peak.[30] It causes the Waterton River, Belly, and Saint Mary rivers to flow north into Alberta, Canada.[31] There they join the Saskatchewan River, which ultimately empties into Hudson Bay.[32]

East of the divide, several roughly parallel ranges cover the southern part of the state, including the Gravelly Range, the Madison Range, Gallatin Range, Absaroka Mountains and the Beartooth Mountains.[33] The Beartooth Plateau is the largest continuous land mass over 10,000 feet (3,000 m) high in the continental United States.[34] It contains the highest point in the state, Granite Peak, 12,799 feet (3,901 m) high.[34] North of these ranges are the Big Belt Mountains, Bridger Mountains, Tobacco Roots, and several island ranges, including the Crazy Mountains and Little Belt Mountains.[35]

Between many mountain ranges are rich river valleys. The Big Hole Valley,[36] Bitterroot Valley,[37] Gallatin Valley,[38] Flathead Valley,[39][40] and Paradise Valley[41] have extensive agricultural resources and multiple opportunities for tourism and recreation.

East and north of this transition zone are the expansive and sparsely populated Northern Plains, with tableland prairies, smaller island mountain ranges, and badlands.[42] The isolated island ranges east of the Divide include the Bear Paw Mountains,[43] Bull Mountains,[44] Castle Mountains,[45] Crazy Mountains,[46] Highwood Mountains,[47] Judith Mountains,[47] Little Belt Mountains,[45] Little Rocky Mountains,[47] the Pryor Mountains,[46] Snowy Mountains,[44] Sweet Grass Hills,[44] and—in the southeastern corner of the state near Ekalaka—the Long Pines.[19] Many of these isolated eastern ranges were created about 120 to 65 million years ago when magma welling up from the interior cracked and bowed the earth's surface here.[48]

The area east of the divide in the north-central portion of the state is known for the Missouri Breaks and other significant rock formations.[49] Three buttes south of Great Falls are major landmarks: Cascade, Crown, Square, Shaw and Buttes.[50] Known as laccoliths, they formed when igneous rock protruded through cracks in the sedimentary rock.[50] The underlying surface consists of sandstone and shale.[51] Surface soils in the area are highly diverse, and greatly affected by the local geology, whether glaciated plain, intermountain basin, mountain foothills, or tableland.[52] Foothill regions are often covered in weathered stone or broken slate, or consiste of uncovered bare rock (usually igneous, quartzite, sandstone, or shale).[53] The soil of intermountain basins usually consists of clay, gravel, sand, silt, and volcanic ash, much of it laid down by lakes which covered the region during the Oligocene 33 to 23 million years ago.[54] Tablelands are often topped with argillite gravel and weathered quartzite, occasionally underlain by shale.[55] The glaciated plains are generally covered in clay, gravel, sand, and silt left by the proglacial Lake Great Falls or by moraines or gravel-covered former lake basins left by the Wisconsin glaciation 85,000 to 11,000 years ago.[56] Farther east, areas such as Makoshika State Park near Glendive and Medicine Rocks State Park near Ekalaka contain some of the most scenic badlands regions in the state.[57]

The Hell Creek Formation in Northeast Montana is a major source of dinosaur fossils.[58] Paleontologist Jack Horner of the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman brought this formation to the world's attention with several major finds.[59]

Rivers, lakes and reservoirs

Montana contains thousands of named rivers and creeks,[60] 450 miles (720 km) of which are known for "blue-ribbon" trout fishing.[61][62] Montana's water resources provide for recreation, hydropower, crop and forage irrigation, mining, and water for human consumption. Montana is one of few geographic areas in the world whose rivers form parts of three major watersheds (i.e. where two continental divides intersect). Its rivers feed the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and Hudson Bay. The watersheds divide at Triple Divide Peak in Glacier National Park.[63]

Pacific Ocean drainage basin

West of the divide, the Clark Fork of the Columbia (not to be confused with the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River) rises near Butte[64] and flows northwest to Missoula, where it is joined by the Blackfoot River and Bitterroot River.[65] Further downstream it is joined by the Flathead River before entering Idaho near Lake Pend Oreille.[31][66] The Pend Oreille River forms the outflow of Lake Pend Oreille. The Pend Oreille River joined the Columbia River, which flows to the Pacific Ocean—making the 579-mile (932 km) long Clark Fork/Pend Oreille (considered a single river system) the longest river in the Rocky Mountains.[67] The Clark Fork discharges the greatest volume of water of any river exiting the state.[68] The Kootenai River in northwest Montana is another major tributary of the Columbia.[69]

Gulf of Mexico drainage basin

East of the divide, the Missouri River—formed by the confluence of the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin rivers near Three Forks[70]—flows due north through the west-central part of the state to Great Falls,[71] then flows generally east through fairly flat agricultural land and the Missouri Breaks to Fort Peck reservoir.[72] The stretch of river between Fort Benton and the Fred Robinson Bridge at the western boundary of Fort Peck Reservoir was designated a National Wild and Scenic River in 1976.[72] The Missouri enters North Dakota near Fort Union,[73] having drained more than half the land area of Montana (82,000 square miles (210,000 km2)).[71] Nearly one-third of the Missouri River in Montana lies behind 10 dams: Toston, Canyon Ferry, Hauser, Holter, Black Eagle, Rainbow, Cochrane, Ryan, Morony, and Fort Peck.[74]

The Yellowstone River rises on the continental divide near Younts Peak in Wyoming's Teton Wilderness.[75] It flows north through Yellowstone National Park, enters Montana near Gardiner, and passes through the Paradise Valley to Livingston.[76] It then flows northeasterly[76] across the state through Billings, Miles City, Glendive, and Sidney.[77] The Yellowstone joins the Missouri in North Dakota just east of Fort Union.[78] It is the longest undammed, free-flowing river in the contiguous United States,[79][80] and drains about a quarter of Montana (36,000 square miles (93,000 km2)).[71]

Other major Montana tributaries of the Missouri include the Smith,[81] Milk,[82] Marias,[83] Judith,[84] and Musselshell Rivers.[85] Montana also claims the disputed title of possessing the world's shortest river, the Roe River, just outside Great Falls.[86] Through the Missouri, these rivers ultimately join the Mississippi River and flow into the Gulf of Mexico.[87]

Major tributaries of the Yellowstone include the Boulder,[88] Stillwater,[89] Clarks Fork,[90] Bighorn,[91] Tongue,[92] and Powder Rivers.[93]

Hudson Bay drainage basin

The Northern Divide turns east in Montana at Triple Divide Peak. It causes the Waterton River, Belly, and Saint Mary rivers to flow north into Alberta. There they join the Saskatchewan River, which ultimately empties into Hudson Bay.[32]

Lakes and reservoirs

There are at least 3,223 named lakes and reservoirs in Montana, including Flathead Lake, the largest natural freshwater lake in the western United States. Other major lakes include Whitefish Lake in the Flathead Valley and Lake McDonald and St. Mary Lake in Glacier National Park. The largest reservoir in the state is Fort Peck Reservoir on the Missouri river, which is contained by the second largest earthen dam and largest hydraulically filled dam in the world.[94] Other major reservoirs include Hungry Horse on the Flathead River, Lake Koocanusa on the Kootenai River, Lake Elwell on the Marias River, Clark Canyon on the Beaverhead River, Yellowtail on the Bighorn River, Canyon Ferry, Hauser, Holter, Rainbow, and Black Eagle on the Missouri River.

Flora and fauna

Vegetation of the state includes lodgepole pine, ponderosa pine; douglas fir, larch, spruce; aspen, birch, red cedar, hemlock, ash, alder; rocky mountain maple and cottonwood trees. Forests cover approximately 25 percent of the state. Flowers native to Montana include asters, bitterroots, daisies, lupins, poppies, primroses, columbine, lilies, orchids, and dryads. Several species of sagebrush and cactus and many species of grasses are common. Many species of mushrooms and lichens[95] are also found in the state.

Montana is home to a diverse array of fauna that includes 14 amphibian,[96] 90 fish,[97] 117 mammal,[98] 20 reptile[99] and 427 bird[100] species. Additionally, there are over 10,000 invertebrate species, including 180 mollusks and 30 crustaceans. Montana has the largest grizzly bear population in the lower 48 states.[101] Montana hosts five federally endangered species–Black-footed ferret, Whooping Crane, Least Tern, Pallid sturgeon and White sturgeon and seven threatened species including the Grizzly bear, Canadian lynx and Bull trout.[102] The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks manages fishing and hunting seasons for at least 17 species of game fish including seven species of trout, Walleye and Smallmouth bass[103] and at least 29 species of game birds and animals including Ring-neck pheasant, Grey partridge, Elk, Pronghorn antelope, Mule deer, Gray wolf and Bighorn sheep.[104]

Protected lands

Montana contains Glacier National Park, "The Crown of the Continent"; and portions of Yellowstone National Park, including three of the park's five entrances. Other federally recognized sites include the Little Bighorn National Monument, Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area, Big Hole National Battlefield, and the National Bison Range. Approximately 31,300,000 acres (127,000 km2), or 35 percent of Montana's land is administered by federal or state agencies. The U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service administers 16,800,000 acres (68,000 km2) of forest land in ten National Forests. There are approximately 3,300,000 acres (13,000 km2) of wilderness in 12 separate wilderness areas that are part of the National Wilderness Preservation System established by the Wilderness Act of 1964. The U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management controls 8,100,000 acres (33,000 km2) of federal land. The U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service administers 110,000 acres (450 km2) of 1.1 million acres of National Wildlife Refuges and waterfowl production areas in Montana. The U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation administers approximately 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) of land and water surface in the state. The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks operates approximately 275,265 acres (1,113.96 km2) of state parks and access points on the state's rivers and lakes. The Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation manages 5,200,000 acres (21,000 km2) of School Trust Land ceded by the federal government under the Land Ordinance of 1785 to the state in 1889 when Montana was granted statehood. These lands are managed by the state for the benefit of public schools and institutions in the state.[105]

Areas managed by the National Park Service include:[106]

- Big Hole National Battlefield near Wisdom

- Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area near Fort Smith

- Glacier National Park

- Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site at Deer Lodge

- Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail

- Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument near Crow Agency

- Nez Perce National Historical Park

- Yellowstone National Park

Climate

Montana is a large state with considerable variation in geography, and the climate is, therefore, equally varied. The state spans from 'below' the 45th parallel (the line equidistant between the equator and North Pole) to the 49th parallel, and elevations range from under 2,000 feet (610 m) to nearly 13,000 feet (4,000 m) above sea level. The western half is mountainous, interrupted by numerous large valleys. Eastern Montana comprises plains and badlands, broken by hills and isolated mountain ranges, and has a semi-arid, continental climate (Köppen climate classification 'BSk'). The Continental Divide has a considerable effect on the climate, as it restricts the flow of warmer air from the Pacific from moving east, and cooler, drier continental air from moving west. The area west of the divide experiences a modified northern Pacific coast climate, with milder winters, cooler summers, less wind and a longer growing season.[107] Low clouds and fog often form in the valleys west of the divide in winter, but this is rarely seen in the east.[108]

Average daytime temperatures vary from 28 °F (−2 °C) in January to 84.5 °F (29.2 °C) in July.[109] The variation in geography leads to great variation in temperature. The highest observed summer temperature was 117 °F (47 °C) at Glendive on July 20, 1893, and Medicine Lake on July 5, 1937. Throughout the state, summer nights are generally cool and pleasant. Extremely hot weather is less common above 4,000 ft (1,200 m).[107] Snowfall has been recorded in all months of the year in the more mountainous areas of central and western Montana, though it is rare in July and August.[107]

The coldest temperature on record for Montana is also the coldest temperature for the entire contiguous U.S. On January 20, 1954, −70 °F (−57 °C) was recorded at a gold mining camp near Rogers Pass. Temperatures vary greatly on such cold nights, and Helena, 40 miles (64 km) to the southeast had a low of only −36 °F (−38 °C) on the same date.[107] Winter cold spells are usually the result of cold continental air coming south from Canada. The front is often well defined, causing a large temperature drop in a 24-hour period. Conversely, air flow from the southwest results in "Chinooks". These steady 25–50 mph (or more) winds can suddenly warm parts of Montana, especially areas just to the east of the mountains, where temperatures sometimes rise up to 50 °F (10 °C) – 60 °F (15 °C) for periods of ten days or longer.[107][110]

Loma is the location of the most extreme recorded temperature change in a 24-hour period in the United States. On January 15, 1972, a chinook wind blew in and the temperature rose from −54 °F (−48 °C) to 49 °F (9 °C)*.[111]

Average annual precipitation is 15 inches (380 mm), but great variations are seen. The mountain ranges block the moist Pacific air, holding moisture in the western valleys, and creating rain shadows to the east. Heron, in the west, receives the most precipitation, 34.70 inches (881 mm). On the eastern (leeward) side of a mountain range, the valleys are much drier; Lonepine averages 11.45 inches (291 mm), and Deer Lodge 11.00 inches (279 mm) of precipitation. The mountains themselves can receive over 100 inches (2,500 mm), for example the Grinnell Glacier in Glacier National Park gets 105 inches (2,700 mm).[108] An area southwest of Belfry averaged only 6.59 inches (167 mm) over a sixteen-year period. Most of the larger cities get 30 to 50 inches (760 to 1,270 mm) of snow each year. Mountain ranges themselves can accumulate 300 inches (7,600 mm) of snow during a winter. Heavy snowstorms may occur any time from September through May, though most snow falls from November to March.[107]

The climate has become warmer in Montana and continues to do so.[112] The glaciers in Glacier National Park have receded and are predicted to melt away completely in a few decades.[113] Many Montana cities set heat records during July 2007, the hottest month ever recorded in Montana.[112][114] Winters are warmer, too, and have fewer cold spells. Previously these cold spells had killed off bark beetles which are now attacking the forests of western Montana.[115][116] The combination of warmer weather, attack by beetles, and mismanagement during past years has led to a substantial increase in the severity of forest fires in Montana.[112][116] According to a study done for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Science, portions of Montana will experience a 200 percent increase in area burned by wildfires, and an 80 percent increase in related air pollution.[117][118]

Antipodes

Montana is one of only two continental US states (along with Colorado) which is antipodal to land. The Kerguelen Islands are antipodal to the Montana–Saskatchewan–Alberta border. No towns are precisely antipodal to Kerguelen, though Chester and Rudyard are close.[119]

History

Various indigenous peoples lived in the territory of the present-day state of Montana for thousands of years. Historic tribes encountered by Europeans and settlers from the United States included the Crow in the south-central area; the Cheyenne in the southeast; the Blackfeet, Assiniboine and Gros Ventres in the central and north-central area; and the Kootenai and Salish in the west. The smaller Pend d'Oreille and Kalispel tribes lived near Flathead Lake and the western mountains, respectively.

The land in Montana east of the continental divide was part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Subsequent to the Lewis and Clark Expedition American, British and French fur traders operated in both east and western portions of Montana. Until the Oregon Treaty (1846), land west of the continental divide was disputed between the British and U.S. and was known as the Oregon Country. The first permanent settlement in what today is Montana was St. Mary's (1841) near present day Stevensville.[120] In 1847, Fort Benton was established as the uppermost fur-trading post on the Missouri River.[121] In the 1850s, settlers began moving into the Beaverhead and Big Hole valleys from the Oregon Trail and into the Clark's Fork valley.[122]

The first gold discovered in Montana was at Gold Creek near present day Garrison in 1852. A series of major mining discoveries in the western third of the state starting in 1862 found gold, silver, copper lead, coal (and later oil) that attracted tens of thousands of miners to the area. The richest of all gold placer diggings was discovered at Alder Gulch, where the town of Virginia City was established. Other rich placer deposits were found at Last Chance Gulch, where the city of Helena now stands, Confederate Gulch, Silver Bow, Emigrant Gulch, and Cooke City. Gold output from 1862 through 1876 reached $144 million; silver then became even more important. The largest mining operations were in the city of Butte, which had important silver deposits and gigantic copper deposits.

Montana territory

Prior to the creation of Montana Territory (1864–1889), various parts of what is now Montana were parts of Oregon Territory (1848–1859), Washington Territory (1853–1863), Idaho Territory (1863–1864), and Dakota Territory (1861–1864). Montana became a United States territory (Montana Territory) on May 26, 1864. The first territorial capital was at Bannack. The first territorial governor was Sidney Edgerton. The capital moved to Virginia City in 1865 and to Helena in 1875. In 1870, the non-Indian population of Montana Territory was 20,595.[123] The Montana Historical Society, founded on February 2, 1865, in Virginia City is the oldest such institution west of the Mississippi (excluding Louisiana).[124] In 1869 and 1870 respectively, the Cook–Folsom–Peterson and the Washburn–Langford–Doane Expeditions were launched from Helena into the Upper Yellowstone region and directly led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872.

===Conflicts=== always use wikapedia

As white settlers began populating Montana from the 1850s through the 1870s, disputes with Native Americans ensued, primarily over land ownership and control. In 1855, Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens negotiated the Hellgate treaty between the United States Government and the Salish, Pend d'Oreille, and the Kootenai people of western Montana, which established boundaries for the tribal nations. The treaty was ratified in 1859.[125] While the treaty established what later became the Flathead Indian Reservation, trouble with interpreters and confusion over the terms of the treaty led whites to believe that the Bitterroot Valley was opened to settlement, but the tribal nations disputed those provisions.[126] The Salish remained in the Bitterroot Valley until 1891.[127]

The first U.S. Army post established in Montana was Camp Cooke on the Missouri River in 1866 to protect steamboat traffic going to Fort Benton, Montana. More than a dozen additional military outposts were established in the state. Pressure over land ownership and control increased due to discoveries of gold in various parts of Montana and surrounding states. Major battles occurred in Montana during Red Cloud's War, the Great Sioux War of 1876, the Nez Perce War and in conflicts with Piegan Blackfeet. The most notable of these were the Marias Massacre (1870), Battle of the Little Bighorn (1876), Battle of the Big Hole (1877) and Battle of Bear Paw (1877). The last recorded conflict in Montana between the U.S. Army and Native Americans occurred in 1887 during the Battle of Crow Agency in the Big Horn country. Indian survivors who had signed treaties were generally required to move onto reservations.[128]

Simultaneously with these conflicts, bison, a keystone species and the primary protein source that Native people had survived on for centuries were being destroyed. Some estimates say there were over 13 million bison in Montana in 1870.[129] In 1875, General Philip Sheridan pleaded to a joint session of Congress to authorize the slaughtering of herds in order to deprive the Indians of their source of food.[130] By 1884, commercial hunting had brought bison to the verge of extinction; only about 325 bison remained in the entire United States.[131]

Cattle ranching

Cattle ranching has been central to Montana's history and economy since Johnny Grant began wintering cattle in the Deer Lodge Valley in the 1850s and traded cattle fattened in fertile Montana valleys with emigrants on the Oregon Trail.[132] Nelson Story brought the first Texas Longhorn Cattle into the territory in 1866.[133][134] Granville Stuart, Samuel Hauser and Andrew J. Davis started a major open range cattle operation in Fergus County in 1879.[135][136] The Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge is maintained today as a link to the ranching style of the late 19th century. Operated by the National Park Service, it is a 1,900-acre (7.7 km2) working ranch.[137]

Railroads

Tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPR) reached Montana from the west in 1881 and from the east in 1882. However, the railroad played a major role in sparking tensions with Native American tribes in the 1870s. Jay Cooke, the NPR president launched major surveys into the Yellowstone valley in 1871, 1872 and 1873 which were challenged forcefully by the Sioux under chief Sitting Bull. These clashes, in part, contributed to the Panic of 1873 which delayed construction of the railroad into Montana.[138] Surveys in 1874, 1875 and 1876 helped spark the Great Sioux War of 1876. The transcontinental NPR was completed on September 8, 1883, at Gold Creek.

Tracks of the Great Northern Railroad (GNR) reached eastern Montana in 1887 and when they reached the northern Rocky Mountains in 1890, the GNR became a significant promoter of tourism to Glacier National Park region. The transcontinental GNR was completed on January 6, 1893, at Scenic, Washington.[139]

In 1881, the Utah and Northern Railway a branch line of the Union Pacific completed a narrow gauge line from northern Utah to Butte.[140] A number of smaller spur lines operated in Montana from 1881 into the 20th century including the Oregon Short Line, Montana Railroad and Milwaukee Road.

Statehood

Under Territorial Governor Thomas Meagher, Montanans held a constitutional convention in 1866 in a failed bid for statehood. A second constitutional convention was held in Helena in 1884 that produced a constitution ratified 3:1 by Montana citizens in November 1884. For political reasons, Congress did not approve Montana statehood until 1889. Congress approved Montana statehood in February 1889 and President Grover Cleveland signed an omnibus bill granting statehood to Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Washington once the appropriate state constitutions were crafted. In July 1889, Montanans convened their third constitutional convention and produced a constitution acceptable by the people and the federal government. On November 8, 1889 President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed Montana the forty-first state in the union. The first state governor was Joseph K. Toole.[141] In the 1880s, Helena (the current state capital) had more millionaires per capita than any other United States city.[142]

Homesteading

The Homestead Act of 1862 provided free land to settlers who could claim and "prove-up" 160 acres (0.65 km2) of federal land in the midwest and western United States. Montana did not see a large influx of immigrants from this act because 160 acres was usually insufficient to support a family in the arid territory.[143] The first homestead claim under the act in Montana was made by David Carpenter near Helena in 1868. The first claim by a woman was made near Warm Springs Creek by Miss Gwenllian Evans, the daughter of Deer Lodge Montana Pioneer, Morgan Evans.[144] By 1880, there were farms in the more verdant valleys of central and western Montana, but few on the eastern plains.[143]

The Desert Land Act of 1877 was passed to allow settlement of arid lands in the west and allotted 640 acres (2.6 km2) to settlers for a fee of $.25 per acre and a promise to irrigate the land. After three years, a fee of one dollar per acre would be paid and the land would be owned by the settler. This act brought mostly cattle and sheep ranchers into Montana, many of which grazed their herds on the Montana prairie for three years, did little to irrigate the land and then abandoned it without paying the final fees.[144] Some farmers came with the arrival of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific Railroads throughout the 1880s and 1890s, though in relatively small numbers.[145]

In the early 1900s, James J. Hill of the Great Northern and began promoting settlement in the Montana prairie to fill his trains with settlers and goods. Other railroads followed suit.[146] In 1902, the Reclamation Act was passed, allowing irrigation projects to be built in Montana's eastern river valleys. In 1909, Congress passed the Enlarged Homestead Act that expanded the amount of free land from 160 acres (0.6 km2) to 320 acres (1.3 km2) per family and in 1912 reduced the time to "prove up" on a claim to three years.[147] In 1916, the Stock-Raising Homestead Act allowed homesteads of 640 acres in areas unsuitable for irrigation. [148] This combination of advertising and changes in the Homestead Act drew tens of thousands of homesteaders, lured by free land, with World War I bringing particularly high wheat prices. In addition, Montana was going through a temporary period of higher-than-average precipitation.[149] Homesteaders arriving in this period were known as "Honyockers", or "scissorbills."[145] Though the word "honyocker", possibly derived from the ethnic slur "hunyak,"[150] was applied in a derisive manner at homesteaders as being "greenhorns", "new at his business" or "unprepared",[151] The reality was that a majority of these new settlers had previous farming experience, though there were also many who did not.[152]

However, farmers faced a number of problems. Massive debt was one.[153] Also, most settlers were from wetter regions, unprepared for the dry climate, lack of trees, and scarce water resources.[154] In addition, small homesteads of fewer than 320 acres (130 ha) were unsuited to the environment. Weather and agricultural conditions are much harsher and drier west of the 100th meridian.[155] Then, the droughts of 1917–1921 proved devastating. Many people left, and half the banks in the state went bankrupt as a result of providing mortgages that could not be repaid.[156] As a result, farm sizes increased while the number of farms decreased[155]

By 1910, homesteaders filed claims on over five million acres, and by 1923, over 93 million acres were farmed.[157] In 1910, the Great Falls land office alone saw over 1,000 homestead filings per month,[158] and the peak of 1917– 1918 saw 14,000 new homesteads each year.[153] But significant drop followed drought in 1919.[155]

Honyocker, scissorbill, nester... He was the Joad of a [half] century ago, swarming into a hostile land: duped when he started, robbed when he arrived; hopeful, courageous, ambitious: he sought independence or adventure, comfort and security... The honyocker was farmer, spinster, deep-sea diver; fiddler, physician, bartender, cook. He lived in Minnesota or Wisconsin, Massachusetts or Maine. There the news sought him out—Jim Hill's news of free land in the Treasure State...

— Joseph Kinsey Howard, Montana, High, Wide, and Handsome[144]

Montana and World War I

As World War I broke out, Jeannette Rankin, the first woman in America to be a member of Congress, was a pacifist and voted against the United States' declaration of war. However, her actions were widely criticized in Montana, public support for the war was strong, and wartime sentiment reached levels of hyper-patriotism among many Montanans.[159] In 1917–18, due to a miscalculation of Montana's population, approximately 40,000 Montanans, ten percent of the state's population,[159] either volunteered or were drafted into the armed forces. This represented a manpower contribution to the war that was 25 percent higher than any other state on a per capita basis. Approximately 1500 Montanans died as a result of the war and 2437 were wounded, also higher than any other state on a per capita basis.[160] Montana's Remount station in Miles City provided 10,000 cavalry horses for the war, more than any other Army post in the US. The war created a boom for Montana mining, lumber and farming interests as demand for war materials and food increased.[159]

In June 1917, the U.S. Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917 which was later extended by the Sedition Act of 1918, enacted in May 1918.[161] In February 1918, the Montana legislature had passed the Montana Sedition Act, which was a model for the federal version.[162] In combination, these laws criminalized criticism of the U.S. government, military, or symbols through speech or other means. The Montana Act led to the arrest of over 200 individuals and the conviction of 78, mostly of German or Austrian descent. Over 40 spent time in prison. In May 2006, then-Governor Brian Schweitzer posthumously issued full pardons for all those convicted of violating the Montana Sedition Act.[163]

The Montanans who opposed U.S. entry into the war included certain immigrant groups of German and Irish heritage as well as pacifist Anabaptist people such as the Hutterites and Mennonites, many of whom were also of Germanic heritage. In turn, pro-War groups formed, such as the Montana Council of Defense, created by Governor Samuel V. Stewart as well as local "loyalty committees."[159]

War sentiment was complicated by labor issues. The Anaconda Copper Company, which was at its historic peak of copper production,[164] was an extremely powerful force in Montana, but also faced noticeable opposition from socialist newspapers and increasing radicalization of unions.[165] In Butte, a multi-ethnic community with significant European immigrant population, labor unions, particularly the newly formed Metal Mine Workers’ Union, opposed the war on grounds that it mostly profited large lumber and mining interests.[159] In the wake of ramped-up mine production and the Speculator Mine disaster in June 1917,[159] Industrial Workers of the World organizer Frank Little arrived in Butte to organize miners. He gave some speeches with inflammatory anti-war rhetoric. On August 1, 1917, he was dragged from his boarding house by masked vigilantes, and hanged from a railroad trestle, considered a lynching.[166] Little's murder and the strikes that followed resulted in the National Guard being sent to Butte to restore order.[159] Overall, anti-German and anti-labor sentiment increased and created a movement that led to the passage of the Montana Sedition Act the following February.[167] In addition, the Council of Defense was made a state agency with the power to prosecute and punish individuals deemed in violation of the Act. The Council also passed rules limiting public gatherings and prohibiting the speaking of German in public.[159]

In the wake of the legislative action in 1918, emotions rose. U.S. Attorney Burton K. Wheeler and several District Court Judges who hesitated to prosecute or convict people brought up on charges were strongly criticized. Wheeler was brought before the Council of Defense, though he avoided formal proceedings, and a District Court judge from Forsyth was impeached. There were burnings of German-language books and several near-hangings. The prohibition on speaking German remained in effect into the early 1920s. Complicating the wartime struggles, the 1918 Influenza epidemic claimed the lives of over 5,000 Montanans.[159] The period has been dubbed "Montana's Agony" by some historians due to the suppression of civil liberties that occurred.[165]

Depression era

An economic depression began in Montana after WWI and lasted through the Great Depression until the beginning of World War II. This caused great hardship for farmers, ranchers, and miners. The wheat farms in eastern Montana make the state a major producer; the wheat has a relatively high protein content and thus commands premium prices.[168][169]

Montana and World War II

When the U.S. entered World War II on December 7, 1941, many Montanans already had enlisted in the military to escape the poor national economy of the previous decade. Another 40,000-plus Montanans entered the armed forces in the first year following the declaration of war, and over 57,000 joined up before the war ended. These numbers constituted about 10 percent of the state’s total population, and Montana again contributed one of the highest numbers of soldiers per capita of any state. Many Native Americans were among those who served, including soldiers from the Crow Nation who became Code Talkers. At least 1500 Montanans died in the war.[170] Montana also was the training ground for the First Special Service Force or "Devil's Brigade," a joint U.S-Canadian commando-style force that trained at Fort William Henry Harrison for experience in mountainous and winter conditions prior to deployment.[170][171] Air bases were built in Great Falls, Lewistown, Cut Bank and Glasgow, some of which were used as staging areas to prepare planes to be sent to allied forces in the Soviet Union. During the war, about 30 Japanese balloon bombs were documented to have landed in Montana, though no casualties nor major forest fires were attributed to them.[170]

In 1940, Jeanette Rankin had once again been elected to Congress, and in 1941, as she did in 1917, she voted against the United States' declaration of war. This time she was the only vote against the war, and in the wake of public outcry over her vote, she required police protection for a time. Other pacifists tended to be those from "peace churches" who generally opposed war. Many individuals from throughout the U.S. who claimed conscientious objector status were sent to Montana during the war as smokejumpers and for other forest fire-fighting duties.[170]

Other military

The planned battleship USS Montana was named in honor of the state. However, the battleship was never completed, making Montana the only one of the 48 states during World War II not to have a battleship named after it. Additionally, Alaska and Hawaii have both had nuclear submarines named after them. As such Montana is the only state in the union without a modern naval ship named in its honor. However, in August 2007 Senator Jon Tester made a request to the Navy that a submarine be christened USS Montana.[172]

Cold war Montana

In the post-World War II Cold War era, Montana became host to U.S. Air Force Military Air Transport Service (1947) for airlift training in C-54 Skymasters and eventually Strategic Air Command (1953) strategic air and missile forces based at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Great Falls. The base also hosted the 29th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, Air Defense Command from 1953 to 1968. In December 1959, Malmstrom AFB was selected as the home of the new Minuteman I ballistic missile. The first operational missiles were in-place and ready in early 1962. In late 1962 missiles assigned to the 341st Strategic Missile Wing would play a major role in the Cuban Missile Crisis. When the Soviets removed their missiles from Cuba, President John F. Kennedy said the Soviets backed down because they knew he had an "Ace in the Hole," referring directly to the Minuteman missiles in Montana. Montana eventually became home to the largest ICBM field in the U.S. covering 23,500 square miles (61,000 km2).[173]

Native American population

Approximately 66,000 people of Native American heritage live in Montana. Stemming from multiple treaties and federal legislation, including the Indian Appropriations Act (1851), the Dawes Act (1887), and the Indian Reorganization Act (1934), seven Indian reservations, encompassing eleven tribal nations, were created in Montana. A twelfth nation, the Little Shell Chippewa is a "landless" people headquartered in Great Falls, recognized by the state of Montana but not by the U.S. Government. The Blackfeet nation is headquartered on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation (1851) in Browning, Crow on the Crow Indian Reservation (1851) in Crow Agency, Confederated Salish and Kootenai and Pend d'Oreille on the Flathead Indian Reservation (1855) in Ronan, Northern Cheyenne on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation (1884) at Lame Deer, Assiniboine and Gros Ventre on the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation (1888) in Fort Belknap Agency, Assiniboine and Sioux on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation (1888) at Poplar, and Chippewa-Cree on the Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation (1916) near Box Elder. Approximately 63% of all Native people live off the reservations, concentrated in the larger Montana cities with the largest concentration of urban Indians in Great Falls. The state also has a small Métis population, and 1990 census data indicated that people from as many as 275 different tribes lived in Montana.[174]

Montana's Constitution specifically reads that "the state recognizes the distinct and unique cultural heritage of the American Indians and is committed in its educational goals to the preservation of their cultural integrity."[175] It is the only state in the U.S. with such a constitutional mandate. As a result, the Indian Education for All Act" mandates schools teach American Indian history, culture, and heritage to from preschool through college.[176] For kindergarten through 12th grade students, an "Indian Education for All" curriculum from the Montana Office of Public Instruction is available free to all schools.[177] Montana is also the only state that has a fully accredited tribal college for each Indian reservation. The University of Montana "was the first to establish dual admission agreements with all of the tribal colleges and as such it was the first institution in the nation to actively facilitate student transfer from the tribal colleges."[176]

Economy

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that Montana's total state product in 2010 was $50.7 billion. Per capita personal income in 2010 was $32,149, 46th in the nation.[178]

Montana is a relative hub of beer microbrewing, ranking third in the nation in number of craft breweries per capita in 2011.[179] There are significant industries for lumber and mineral extraction; the state's resources include gold, coal, silver, talc, and vermiculite. Ecotaxes on resource extraction are numerous. A 1974 state severance tax on coal (which varied from 20 to 30 percent) was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in Commonwealth Edison Co. v. Montana, 453 U.S. 609 (1981).[180]

Tourism is also important to the economy with millions of visitors a year to Glacier National Park, Flathead Lake, the Missouri River headwaters, the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn and three of the five entrances to Yellowstone National Park.[181]

Montana's personal income tax contains 7 brackets, with rates ranging from 1 percent to 6.9 percent. Montana has no sales tax. In Montana, household goods are exempt from property taxes. However, property taxes are assessed on livestock, farm machinery, heavy equipment, automobiles, trucks, and business equipment. The amount of property tax owed is not determined solely by the property's value. The property's value is multiplied by a tax rate, set by the Montana Legislature, to determine its taxable value. The taxable value is then multiplied by the mill levy established by various taxing jurisdictions—city and county government, school districts and others.[182]

As of February 2013, the state's unemployment rate is 5.6 percent.[183]

Culture

Many well-known artists, photographers and authors have documented the land, culture and people of Montana in the last 100 years. Painter and sculptor Charles Marion Russell, known as "the cowboy artist" created more than 2,000 paintings of cowboys, Indians, and landscapes set in the Western United States and in Alberta, Canada.[184] The C. M. Russell Museum Complex located in Great Falls, Montana houses more than 2,000 Russell artworks, personal objects, and artifacts.

Evelyn Cameron, a naturalist and photographer from Terry documented early 20th century life on the Montana prairie, taking startlingly clear pictures of everything around her: cowboys, sheepherders, weddings, river crossings, freight wagons, people working, badlands, eagles, coyotes and wolves.[185]

Many notable Montana authors have documented or been inspired by life in Montana in both fiction and non-fiction works. Pulitzer Prize winner Wallace Earle Stegner from Great Falls was often called "The Dean of Western Writers".[186] James Willard Schultz ("Apikuni") from Browning is most noted for his prolific stories about Blackfeet life and his contributions to the naming of prominent features in Glacier National Park.[187]

Major cultural events

Montana hosts numerous arts and cultural festivals and events every year. Major events include:

- Bozeman was once known as the "Sweet Pea capital of the nation" referencing the prolific edible pea crop. To promote the area and celebrate its prosperity, local business owners began a "Sweet Pea Carnival" that included a parade and queen contest. The annual event lasted from 1906 to 1916. Promoters used the inedible but fragrant and colorful sweet pea flower as an emblem of the celebration. In 1977 the "Sweet Pea" concept was revived as an arts festival rather than a harvest celebration, growing into a three-day event that is one of the largest festivals in Montana.[188]

- Montana Shakespeare in the Parks has been performing free, live theatrical productions of Shakespeare and other classics throughout Montana since 1973.[189] The Montana Shakespeare Company is based in Helena.[190]

- Since 1909, the Crow Fair and Rodeo, near Hardin, has been an annual event every August in Crow Agency and is currently the largest Northern Native American gathering, attracting nearly 45,000 spectators and participants.[191] Since 1952, North American Indian Days has been held every July in Browning.[192]

Education

Colleges and universities

|

The Montana University System consists of:

Tribal colleges in Montana include:

There are three private, non-profit colleges in Montana: |

Sports

Professional sports

There are no major league sports franchises in Montana due to the state's relatively small and dispersed population, but a number of minor league teams play in the state. Baseball is the minor-league sport with the longest heritage in the state, and Montana is currently home to four Minor League baseball teams, all members of the Pioneer Baseball League:

Collegiate and High School sports

All of Montana's four-year colleges and universities field a variety of intercollegiate sports teams. The two largest schools, the University of Montana and Montana State University, are members of the Big Sky Conference and have enjoyed a strong athletic rivalry since the early twentieth century. Six of the Montana's smaller four-year schools are members of the Frontier Conference.[193] One is a member of the Great Northwest Athletic Conference.[194] A variety of sports are offered at Montana high schools.[195] Montana allows the smallest—"Class C"—high schools to utilize six-man football teams,[196] dramatized in the independent 2002 film, The Slaughter Rule.[197]

Amateur sports

There are six junior hockey teams in Montana, five of which are affiliated with the American West Hockey League (the Glacier Nationals are in Northern Pacific Hockey League):

- Billings Bulls

- Bozeman Icedogs

- Glacier Nationals

- Great Falls Americans

- Helena Bighorns

- Missoula Maulers

Numerous other sports are played at the club and amateur level. In 2011, Big Sky Little League won the Northwest Region, advancing to the Little League World Series in South Williamsport, PA for the first time in state history.

Major sporting milestones

- In 1889, Spokane became the first and only Montana horse to win the Kentucky Derby. For this accomplishment, the horse was admitted to the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame in 2008.[198][199]

- In 1904 a basketball team of young Native American women from Fort Shaw, after playing undefeated during their previous season, went to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition held in St. Louis in 1904, defeated all challenging teams and were declared to be world champions.[200]

- In 1923, the controversial Jack Dempsey vs. Tommy Gibbons fight for the heavyweight boxing championship, won by Dempsey, took place in Shelby.[201]

- Montana has produced two U.S. Champions and Olympic competitors in Men's Figure Skating, both from Great Falls: John Misha Petkevich, lived and trained in Montana prior to entering college, competed in the 1968 and 1972 Winter Olympics.[202][203] Scott Davis, also from Great Falls, competed at the 1994 Winter Olympics[204]

- Governor Judy Martz had been a member of the women's speed skating team at the 1964 Winter Olympics prior to entering politics[205]

Recreation

Montana provides year round recreation opportunities for residents and visitors. Hiking, fishing, hunting, watercraft recreation, camping, golf, cycling, horseback riding, and skiing are popular activities.[206]

Fishing and hunting

Montana has been a destination for its world-class trout fisheries since the 1930s.[207] Fly fishing for several species of native and introduced trout in rivers and lakes is popular for both residents and tourists throughout the state. Montana is the home of the Federation of Fly Fishers and hosts many of the organizations annual conclaves. The state has robust recreational Lake Trout and Kokanee Salmon fisheries in the west, Walleye can be found in many parts of the state, while Northern Pike, smallmouth and largemouth bass fisheries as well as catfish and paddlefish can found in the waters of eastern Montana.[208] Robert Redford's 1992 film of Norman Mclean's A River Runs Through It was filmed in Montana and brought national attention to fly fishing and the state.[209]

Montana is home to the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and has a historic big game hunting tradition. There are fall bow and general hunting seasons for elk, moose, pronghorn antelope, whitetail deer and mule deer. A random draw grants a limited number of permits for mountain goats and bighorn sheep. There is a spring hunting season for black bear and in most years, limited hunting of bison that leave Yellowstone National Park is allowed. Current law allows both hunting and trapping of a specific number of wolves and mountain lions. Trapping of assorted fur bearing animals is allowed in certain seasons and many opportunities exist for migratory waterfowl and upland bird hunting.[210][211]

Winter recreation

Both downhill skiing and cross-country skiing are popular in Montana, which has 15 developed downhill ski areas open to the public,[212] including;

- Bear Paw Ski Bowl near Havre, Montana

- Big Sky Resort, at Big Sky

- Blacktail Mountain near Lakeside

- Bridger Bowl Ski Area near Bozeman

- Discovery Basin between Philipsburg and Anaconda

- Great Divide near Helena, Montana

- Lookout Pass off Interstate 90 at the Montana-Idaho border

- Lost Trail near Darby, Montana

- Maverick Mountain near Dillon, Montana

- Moonlight Basin near Big Sky

- Red Lodge Mountain Resort near Red Lodge

- Showdown Ski Area near White Sulphur Springs, Montana

- Snowbowl Ski Area near Missoula

- Turner Mountain Ski Resort near Libby

- Whitefish Mountain Resort near Whitefish

Big Sky, Moonlight Basin, Red Lodge, and Whitefish Mountain are destination resorts, while the remaining areas do not have overnight lodging at the ski area, though several host restaurants and other amenities.[212] These day-use resorts partner with local lodging businesses to offer ski and lodging packages.[213][214]

Montana also has millions of acres open to cross-country skiing on nine of its national forests plus in Glacier National Park. In addition to cross-country trails at most of the downhill ski areas, there are also 13 private cross-country skiing resorts.[215] Yellowstone National Park also allows cross-country skiing.[216]

Snowmobiling is popular in Montana which boasts over 4000 miles of trails and frozen lakes available in winter.[217] There are 24 areas where snowmobile trails are maintained, most also offering ungroomed trails.[218] West Yellowstone offers a large selection of trails and is the primary starting point for snowmobile trips into Yellowstone National Park,[219] where "oversnow" vehicle use is strictly limited, usually to guided tours, and regulations are in considerable flux.[220]

Snow coach tours are offered at Big Sky, Whitefish, West Yellowstone and into Yellowstone National Park.[221] Equestrian skijoring has a niche in Montana, which hosts the World Skijoring Championships in Whitefish as part of the annual Whitefish Winter Carnival.[222]

Health

Montana does not have a Trauma I hospital, but does have Trauma II hospitals in Billings, Missoula, and Great Falls.[223] In 2013 AARP The Magazine named the Billings Clinic one of the safest hospitals in the United States.[224]

Media

As of 2010, Missoula is the 166th largest media market in the United States as ranked by Nielsen Media Research, while Billings is 170th, Great Falls is 190th, the Butte-Bozeman area 191st, and Helena is 206th.[225] There are 25 television stations in Montana, representing each major U.S. network.[226] As of August 2013, there are 527 FCC-licensed FM radio stations broadcast in Virginia, with 114 such AM stations.[227][228]

During the age of the Copper Kings, each Montana copper company had its own newspaper. This changed in 1959 when Lee Enterprises bought several Montana newspapers.[229][230] Montana's largest circulating daily city newspapers are the Billings Gazette (circulation 39,405), Great Falls Tribune (26,733), and Missoulian (25,439).[231]

Transportation

Railroads have been an important method of transportation in Montana since the 1880s. Historically, the state was traversed by the main lines of three east-west transcontinental routes: the Milwaukee Road, the Great Northern, and the Northern Pacific. Today, the BNSF Railway is the state's largest railroad, its main transcontinental route incorporating the former Great Northern main line across the state. Montana RailLink, a privately held Class II railroad, operates former Northern Pacific trackage in western Montana.

In addition, Amtrak's Empire Builder train runs through the north of the state, stopping in Libby, Whitefish, West Glacier, Essex, East Glacier Park, Browning, Cut Bank, Shelby, Havre, Malta, Glasgow, and Wolf Point.

Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport is the busiest airport in the state of Montana, surpassing Billings Logan International Airport in the spring of 2013.[232][233] Montana's other major Airports include Billings Logan International Airport, Missoula International Airport, Great Falls International Airport, Glacier Park International Airport, Helena Regional Airport, Bert Mooney Airport and Yellowstone Airport. Eight smaller communities have airports designated for commercial service under the Essential Air Service program.[234]

Historically, U.S. Route 10 was the primary east-west highway route across Montana, connecting the major cities in the southern half of the state. Still the state's most important east-west travel corridor, the route is today served by Interstate 90 and Interstate 94 which roughly follow the same route as the Northern Pacific. U.S. Routes 2 and 12 and Montana Highway 200 also traverse the entire state from east to west.

Montana's only north-south Interstate Highway is Interstate 15. Other major north-south highways include U.S. Routes 87, 89, 93 and 191. Interstate 25 terminates into I-90 just south of the Montana border in Wyoming.

Montana and South Dakota are the only states to share a land border which is not traversed by a paved road; Highway 212 passes through the northeast corner of Wyoming between Montana and South Dakota.[235][236]

Law and government

The current Governor is Steve Bullock, a Democrat elected in 2012 and sworn in on January 7, 2013. His predecessor in office was two-term governor, Brian Schweitzer. Montana's two U.S. senators are Max Baucus and Jon Tester, both Democrats. The state's congressional representative is currently Republican Steve Daines, elected in 2012 and sworn in on January 3, 2013.

In 1914 Montana granted women the vote and in 1916 became the first state to elect a woman, Progressive Republican Jeannette Rankin, to Congress.[237][238]

Montana is an Alcoholic beverage control state.[239]

Politics

Politics in the state has been competitive, with the Democrats usually holding an edge, thanks to the support among unionized miners and railroad workers. Large-scale battles revolved around the giant Anaconda Copper company, based in Butte and controlled by Rockefeller interests, until it closed in the 1970s. Until 1959, the company owned five of the state's six largest newspapers.[240]

Historically, Montana is a swing state of cross-ticket voters who tend to fill elected offices with individuals from both parties. Through the mid-20th century, the state had a tradition of "sending the liberals to Washington and the conservatives to Helena." Between 1988 and 2006, the pattern flipped, with voters more likely to elect conservatives to federal offices. There have also been long-term shifts of party control. From 1968 through 1988, the state was dominated by the Democratic Party, with Democratic governors for a 20-year period, and a Democratic majority of both the national congressional delegation and during many sessions of the state legislature. This pattern shifted, beginning with the 1988 election, when Montana elected a Republican governor for the first time since 1964 and sent a Republican to the U.S. Senate for the first time since 1948. This shift continued with the reapportionment of the state's legislative districts that took effect in 1994, when the Republican Party took control of both chambers of the state legislature, consolidating a Republican party dominance that lasted until the 2004 reapportionment produced more swing districts and a brief period of Democratic legislative majorities in the mid-2000s.[241]

In presidential elections, Montana was long classified as a swing state, though the state has voted for the republican candidate in all but two elections from 1952 to the present.[242] The state last supported a Democrat for president in 1992, when Bill Clinton won a plurality victory. Overall, since 1889 the state has voted for Democratic governors 60 percent of the time and Democratic presidents 40 percent of the time, with these numbers being 40/60 for Republican candidates. In the 2008 presidential election, Montana was considered a swing state and was ultimately won by Republican John McCain, albeit by a narrow margin of two percent.[243]

However, at the state level, the pattern of split ticket voting and divided government holds. Democrats currently hold both U.S. Senate seats, as well as four of the five statewide offices (Governor, Superintendent of Public Instruction, Secretary of State and State Auditor). The Legislative branch had split party control between the house and senate most years between 2004 and 2010, when the mid-term elections returned both branches to Republican control. The state Senate is, as of 2013, controlled by the Republicans 29 to 21, and the State House of Representatives at 61 to 39.[241]

Montana currently has only one representative in the U.S. House, having lost its second district in the 1990 census reapportionment, which makes it the poorest-represented U.S. state in the House (see List of U.S. states by population). Montana's population grew at about the national average during the 2000s, and it failed to regain its second seat in 2010. Like other states, Montana has two senators.[244]

Current trends

A November 2011 Public Policy Polling survey found that 37 percent of Montana voters supported the legalization of same-sex marriage, while 51 percent opposed it and 12 percent were not sure. A separate question on the same survey found that 62 percent of respondents supported legal recognition for same-sex couples, with 32 percent supporting same-sex marriage, 30 percent supporting civil unions, 35 percent opposing all legal recognition and 3 percent not sure.[245]

Cities and towns

Montana has 56 counties with the United States Census Bureau stating Montana's contains 364 "places", broken down into 129 incorporated places and 235 census-designated places. Incorporated places consist of 52 cities, 75 towns, and two consolidated city-counties.[246] Montana has one city, Billings, with a population over 100,000; and two cities with populations over 50,000, Missoula and Great Falls. These three communities are considered the centers of Montana's three Metropolitan Statistical Areas. The state also has five Micropolitan Statistical Areas centered on Bozeman, Butte, Helena, Kalispell and Havre.[247] These communities, excluding Havre, are colloquially known as the "big 7" Montana cities, as they are consistently the seven largest communities in Montana, with a significant population difference when these communities are compared to those that are 8th and lower on the list.[248] According to 2010 U.S. Census the population of Montana's seven most populous cities, in rank order, are Billings, Missoula, Great Falls, Bozeman, Butte, Helena and Kalispell.[248] Based on 2000 census numbers, they collectively contain 34 percent of Montana's population.[249] and the counties containing these communities hold more than 60 percent of the state's population.[250] The geographic center of population of Montana, however, is located in sparsely populated Meagher County, in the town of White Sulphur Springs.[251]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 20,595 | — | |

| 1880 | 39,159 | 90.1% | |

| 1890 | 142,924 | 265.0% | |

| 1900 | 243,329 | 70.3% | |

| 1910 | 376,053 | 54.5% | |

| 1920 | 548,889 | 46.0% | |

| 1930 | 537,606 | −2.1% | |

| 1940 | 559,456 | 4.1% | |

| 1950 | 591,024 | 5.6% | |

| 1960 | 674,767 | 14.2% | |

| 1970 | 694,409 | 2.9% | |

| 1980 | 786,690 | 13.3% | |

| 1990 | 799,065 | 1.6% | |

| 2000 | 902,195 | 12.9% | |

| 2010 | 989,415 | 9.7% | |

| 2012 (est.) | 1,005,141 | 1.6% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[252] | |||

The 2010 census put Montana's population at 989,415 which is an increase of 87,220 people, or 9.7 percent, since the year 2000.[248] Growth is mainly concentrated in Montana's seven largest counties, with the heaviest percentile growth in Gallatin County, which saw a 32 percent increase in its population since 2000.[253] The city seeing the largest percentile growth was Kalispell with 40.1 percent, and the city with the largest actual growth was Billings with an increase in population of 14,323 since 2000.[254] Much of the growth in both cities is explained by annexation and boundary changes, however.[254]

On January 3, 2012, the Census and Economic Information Center (CEIC) at the Montana Department of Commerce estimated Montana had hit the one million mark sometime between November and December 2011.[255] The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Montana was 1,005,141 on July 1, 2012, a 1.6 percent increase since the 2010 United States Census.[1]

According to the 2010 Census, 89.4 percent of the population was White (87.8 percent Non-Hispanic White), 6.3 percent American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.9 percent Hispanics and Latinos of any race, 0.6 percent Asian, 0.4 percent Black or African American, 0.1 percent Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 0.6 percent from Some Other Race, and 2.5 percent from two or more races.[256] The largest European ancestry groups in Montana as of 2010 are: German (27.0 percent), Irish (14.8 percent), English (12.6 percent), and Norwegian (10.9 percent).[257]

According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 94.8 percent of the population aged 5 and older speak English at home.[258] Spanish is the language most commonly spoken at home other than English. There were about 13,040 Spanish-language speakers in the state (1.4 percent of the population) in 2011.[259] There were also 15,438 (1.7 percent of the state population) speakers of Indo-European languages other than English or Spanish, 10,154 (1.1 percent) speakers of a Native American language, and 4,052 (0.4 percent) speakers of an Asian or Pacific Islander language.[259] Other languages spoken in Montana (as of 2013) include Assiniboine (about 150 speakers in the Montana and Canada), Blackfoot (about 100 speakers), Cheyenne (about 1,700 speakers), Plains Cree (about 100 speakers), Crow (about 3,000 speakers), Dakota (about 18,800 speakers in Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota), German Hutterite (about 5,600 speakers), Gros Ventre (about 10 speakers), Kalispel-Pend d’Oreille (about 64 speakers), Kutenai (about 6 speakers), and Lakota (about 6,000 speakers in Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota).[260] The United States Department of Education estimated in 2009 that 5,274 students in Montana spoke a language at home other than English. These included a Native American language (64 percent), German (4 percent), Spanish (3 percent), Russian (1 percent), and Chinese (less than 0.5 percent).[261]

Intra-state demographics

Montana has a larger Native American population numerically and percentage-wise than most U.S. states. Although the state ranked 45th in population (according to the 2010 U.S. Census), it ranked 19th in total native people population.[262] Native people constituted 6.5 percent of the state's total population, the sixth highest percentage of all 50 states.[262] Montana has three counties in which Native Americans are a majority: Big Horn, Glacier, and Roosevelt.[263] Other counties with large Native Ameican populations include Blaine, Cascade, Hill, Missoula, and Yellowstone counties.[264] The state's Native American population grew by 27.9 percent between 1908 and 1990 (at a time when Montana's entire population rose just 1.6 percent),[264] and by 18.5 percent between 2000 and 2010.[265] As of 2009, almost two-thirds of Native Americans in the state live in urban areas.[264] Of Montana's 20 largest cities, Polson (15.7 percent), Havre (13.0 percent), Great Falls (5.0 percent), Billings (4.4 percent), and Anaconda (3.1 percent) had the greatest percentage of Native American residents in 2010.[266] Billings (4,619), Great Falls (2,942), Missoula (1,838), Havre (1,210), and Polson (706) have the most Native Americans living there.[266] The state's seven reservations include more than twelve distinct Native American ethnolinguistic groups.[256]

While the largest European-American population in Montana overall is German, pockets of significant Scandinavian ancestry are prevalent in some of the farming-dominated northern and eastern prairie regions, parallel to nearby regions of North Dakota and Minnesota. Farmers of Irish, Scots, and English roots also settled in Montana. The historically mining-oriented communities of western Montana such as Butte have a wider range of European-American ethnicity; Finns, Eastern Europeans and especially Irish settlers left an indelible mark on the area, as well as people originally from British mining regions such as Cornwall, Devon and Wales. The nearby city of Helena, also founded as a mining camp, had a similar mix in addition to a small Chinatown.[256] Many of Montana's historic logging communities originally attracted people of Scottish, Scandinavian, Slavic, English and Scots-Irish descent.[citation needed]

The Hutterites, an Anabaptist sect originally from Switzerland, settled here, and today Montana is second only to South Dakota in U.S. Hutterite population with several colonies spread across the state. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the state also saw an influx of Amish, who relocated to Montana from the increasingly urbanized areas of Ohio and Pennsylvania.[267]

Montana's Hispanic population is concentrated around the Billings area in south-central Montana, where many of Montana's Mexican-Americans have been in the state for generations. Great Falls has the highest percentage of African-Americans in its population, although Billings has more African American residents than Great Falls.[266]

The Chinese in Montana, while a low percentage today, have historically been an important presence. About 2000–3000 Chinese miners were in the mining areas of Montana by 1870, and 2500 in 1890. However, public opinion grew increasingly negative toward them in the 1890s and nearly half of the state's Asian population left the state by 1900.[268] Today, there is a significant Hmong population centered in the vicinity of Missoula.[269] Montanans who claim Filipino ancestry amount to almost 3,000, making them currently the largest Asian American group in the state.[256]

| By race | White | Black | AIAN* | Asian | NHPI* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 (total population) | 92.79% | 0.50% | 7.36% | 0.79% | 0.12% |

| 2000 (Hispanic only) | 1.74% | 0.05% | 0.28% | 0.04% | 0.01% |

| 2005 (total population) | 92.52% | 0.62% | 7.47% | 0.82% | 0.11% |

| 2005 (Hispanic only) | 2.22% | 0.07% | 0.23% | 0.03% | 0.01% |

| Growth 2000–05 (total population) | 3.42% | 28.09% | 5.19% | 7.11% | -4.46% |

| Growth 2000–05 (non-Hispanic only) | 2.87% | 25.58% | 5.91% | 8.07% | -0.82% |

| Growth 2000–05 (Hispanic only) | 31.85% | 52.36% | -13.46% | -13.52% | -39.22% |

| * AIAN is American Indian or Alaskan Native; NHPI is Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | |||||

Religion

The religious affiliations of the people of Montana include:

- Christian: 82 percent

- Protestant: 55 percent

- Lutheran: 15 percent

- Methodist: 8 percent

- Baptist: 5 percent

- Presbyterian: 4 percent

- United Church of Christ: 2 percent

- Other Protestant or general Protestant: 21 percent

- Roman Catholic: 24 percent

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon): 5 percent

- Protestant: 55 percent

- Other religions: <1 percent

- Non-religious: 18 percent[citation needed]

As of the year 2000[update], the RCMS reported that the three largest denominational groups in Montana are Catholic, Evangelical Protestant, and Mainline Protestant.[270]