Manchu people

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 10,682,263 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 10,410,585 (2010 census)[1] | |

| 12,000 (2004 estimate)[2] | |

| 1,000 (1997 estimate)[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Mandarin Chinese Manchu | |

| Religion | |

| Manchu shamanism, Buddhism, Chinese folk religion, Roman Catholicism and Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Han Chinese, other Tungusic peoples Especially Sibes, Nanais, Ulchi and Jaegaseung | |

The Manchus (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ, Möllendorff: manju; Chinese: 滿族; pinyin: Mǎnzú; Wade–Giles: Man3-tsu2)[a] are a Tungusic East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized ethnic minority in China and the people from whom Manchuria derives its name.[9][10] The Later Jin (1616–1636) and Qing (1636–1912) dynasties of China were established and ruled by the Manchus, who are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in northern China. Manchus form the largest branch of the Tungusic peoples and are distributed throughout China, forming the fourth largest ethnic group in the country.[1] They are found in 31 Chinese provincial regions. Among them, Liaoning has the largest population and Hebei, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Inner Mongolia and Beijing have over 100,000 Manchu residents. About half of the population live in Liaoning and one-fifth in Hebei. There are a number of Manchu autonomous counties in China, such as Xinbin, Xiuyan, Qinglong, Fengning, Yitong, Qingyuan, Weichang, Kuancheng, Benxi, Kuandian, Huanren, Fengcheng, Beizhen[b] and over 300 Manchu towns and townships.[11] Manchus are the largest minority group in China without an autonomous region.

Name

[edit]"Manchu" (Manchu: ᠮᠠᠨᠵᡠ, Möllendorff: manju) was adopted as the official name of the people by Emperor Hong Taiji in 1635, replacing the earlier name "Jurchen". It appears that manju was an old term for the Jianzhou Jurchens, although the etymology is not well understood.[12]: 63

The Jiu Manzhou Dang, archives of early 17th century documents, contains the earliest use of Manchu.[13] However, the actual etymology of the ethnic name "Manju" is debatable.[14]: 49 According to the Qing dynasty's official historical record, the Researches on Manchu Origins, the ethnic name came from Mañjuśrī.[15] The Qianlong Emperor also supported the point of view and even wrote several poems on the subject.[16]: 6

Meng Sen, a scholar of the Qing dynasty, agreed. On the other hand, he thought the name Manchu might stem from Li Manzhu (李滿住), the chieftain of the Jianzhou Jurchens.[16]: 4–5

Another scholar, Chang Shan, thinks Manju is a compound word. Man was from the word mangga (ᠮᠠᠩᡤᠠ) which means "strong," and ju (ᠵᡠ) means "arrow." So Manju actually means "intrepid arrow".[17]

There are other hypotheses, such as Fu Sinian's "etymology of Jianzhou"; Zhang Binglin's "etymology of Manshi"; Ichimura Sanjiro [jp]'s "etymology of Wuji and Mohe"; Sun Wenliang's "etymology of Manzhe"; "etymology of mangu(n) river" and so on.[18][19][20]

An extensive etymological study from 2022 lends additional support to the view that manju is cognate with words referring to the lower Amur river in other Tungusic languages and can be reconstructed to Proto-Tungusic *mamgo 'lower Amur, large river'.[21]

History

[edit]Origins and early history

[edit]

The Manchus are descended from the Jurchen people who earlier established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) in China.[22][23]: 5 [24] The name Mohe might refer to an ancestral population of the Manchus. The Mohe practiced pig farming extensively and were mainly sedentary,[25] and also used both pig and dog skins for coats. They were predominantly farmers and grew soybeans, wheat, millet and rice, in addition to hunting.[25]

In the 10th century AD, the term Jurchen first appeared in documents of the late Tang dynasty in reference to the state of Balhae in present-day northeastern China. The Jurchens were sedentary,[26] settled farmers with advanced agriculture. They farmed grain and millet as their cereal crops, grew flax, and raised oxen, pigs, sheep and horses.[27] Their farming way of life was very different from the pastoral nomadism of the Mongols and the Khitans on the steppes.[28][29] Most Jurchens raised pigs and stock animals and were farmers.[30]

In 1019, Jurchen pirates raided Japan for slaves. Fujiwara Notada, the Japanese governor was killed.[31] In total, 1,280 Japanese were taken prisoner, 374 Japanese were killed and 380 Japanese-owned livestock were killed for food.[32][33] Only 259 or 270 were returned by Koreans from the 8 ships.[34][35][36][37] The woman Uchikura no Ishime's report was copied down[clarification needed].[38] Traumatic memories of the Jurchen raids on Japan in the 1019 Toi invasion, the Mongol invasions of Japan in addition to Japan viewing the Jurchens as "Tatar" "barbarians" after copying China's barbarian-civilized distinction, may have played a role in Japan's antagonistic views against Manchus and hostility towards them in later centuries such as when Tokugawa Ieyasu viewed the unification of Manchu tribes as a threat to Japan. The Japanese mistakenly thought that Hokkaido (Ezochi) had a land bridge to Tartary (Orankai) where Manchus lived and thought the Manchus could invade Japan. The Tokugawa Shogunate bakufu sent a message to Korea via Tsushima offering help to Korea against the 1627 Manchu invasion of Korea. Korea declined the help.[39]

Following the fall of Balhae, the Jurchens became vassals of the Khitan-led Liao dynasty. The Jurchens in the Yalu River region were tributaries of Goryeo since the reign of Wang Geon, who called upon them during the wars of the Later Three Kingdoms period, but the Jurchens switched allegiance between Liao and Goryeo multiple times, taking advantage of the tension between the two nations; posing a potential threat to Goryeo's border security, the Jurchens offered tribute to the Goryeo court, expecting lavish gifts in return.[40] Before the Jurchens overthrew the Khitan, married Jurchen women and Jurchen girls were raped by Liao Khitan envoys as a custom which caused resentment.[41] The Jurchens and their Manchu descendants had Khitan linguistic and grammatical elements in their personal names like suffixes.[42] Many Khitan names had a "ju" suffix.[43] In the year 1114, Wanyan Aguda united the Jurchen tribes and established the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[44]: 19–46 His brother and successor, Wanyan Wuqimai defeated the Liao dynasty. After the fall of the Liao dynasty, the Jurchens went to war with the Northern Song dynasty, and captured most of northern China in the Jin–Song wars.[44]: 47–67 During the Jin dynasty, the first Jurchen script came into use in the 1120s. It was mainly derived from the Khitan script.[44]: 19–46

In 1206, the Mongols, vassals to the Jurchens, rose in Mongolia. Their leader, Genghis Khan, led Mongol troops against the Jurchens, who were finally defeated by Ögedei Khan in 1234.[7]: 18 The Jurchen Jin emperor Wanyan Yongji's daughter, Jurchen Princess Qiguo was married to Mongol leader Genghis Khan in exchange for relieving the Mongol siege upon Zhongdu (Beijing) in the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty.[45] The Yuan grouped people into different groups based on how recently their state surrendered to the Yuan. Subjects of southern Song were grouped as southerners (nan ren) and also called manzi. Subjects of the Jin dynasty, Western Xia and kingdom of Dali in Yunnan in southern China were classified as northerners, also using the term Han. However the use of the word Han as the name of a class category used by the Yuan dynasty was a different concept from Han ethnicity. The grouping of Jurchens in northern China grouped with northern Han into the northerner class did not mean they were regarded the same as ethnic Han people, who themselves were in two different classes in the Yuan, Han ren and Nan Ren as said by Stephen G. Haw. Also the Yuan directive to treat Jurchens the same as Mongols referred to Jurchens and Khitans in the northwest (not the Jurchen homeland in the northeast), presumably in the lands of Qara Khitai, where many Khitan live but it is a mystery as to how Jurchens were living there.[46] Many Jurchens adopted Mongolian customs, names, and the Mongolian language. As time went on, fewer and fewer Jurchens could recognize their own script. The Jurchen Yehe Nara clan is of paternal Mongol origin.

Many Jurchen families descended from the original Jin Jurchen migrants in Han areas like those using the surnames Wang and Nian 粘 have openly reclaimed their ethnicity and registered as Manchus. Wanyan (完顏) clan members who had changed their surnames to Wang (王) after the Mongol conquest of the Jin dynasty applied successfully to the PRC government for their ethnic group to be marked as Manchu despite never having been part of the Eight Banner system at all during the Qing dynasty. The surname Nianhan (粘罕), shortened to Nian (粘) is a Jurchen origin surname, also originating from one of the members of the royal Wanyan clan. It is an extremely rare surname in China, and 1,100 members of the Nian clan live in Nan'an, Quanzhou, they live in Licheng district of Quanzhou, 900 in Jinjiang, Quanzhou, 40 in Shishi city of Quanzhou, and 500 in Quanzhou city itself in Fujian, and just over 100 people in Xiamen, Jin'an district of Fuzhou, Zhangpu and Sanming, as well as 1000 in Laiyang, Shandong, and 1,000 in Kongqiao and Wujiazhuang in Xingtai, Hebei. Some of the Nian from Quanzhou immigrated to Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia. In Taiwan they are concentrated in Lukang township and Changhua city of Changhua county as well as in Dingnien village, Xianne village Fuxing township of Changhua county. There are less than 30,000 members of the Nian clan worldwide, with 9,916 of them in Taiwan, and 3,040 of those in Fuxing township of Changhua county and its most common in Dingnian village.

During the transition between the Ming and Qing Zhang Sunzhen, a civilian official in Nanjing himself remarked that he had a portrait of his ancestors wearing Manchu clothes because his family were Tartars so it was appropriate that he was going to shave his head into the Manchu hairstyle when the queue order was given.[47][48]

The Mongol-led Yuan dynasty was replaced by the Ming dynasty in 1368. In 1387, Ming forces defeated the Mongol commander Naghachu's resisting forces who settled in the Haixi area[12]: 11 and began to summon the Jurchen tribes to pay tribute.[16]: 21 At the time, some Jurchen clans were vassals to the Joseon dynasty of Korea such as Odoli and Huligai.[16]: 97, 120 Their elites served in the Korean royal bodyguard.[12]: 15

The Joseon Koreans tried to deal with the military threat posed by the Jurchen by using both forceful means and incentives, and by launching military attacks. At the same time they tried to appease them with titles and degrees, traded with them, and sought to acculturate them by having Jurchens integrate into Korean culture.[49][50] Their relationship was eventually stopped by the Ming dynasty government who wanted the Jurchens to protect the border. In 1403, Ahacu, chieftain of Huligai, paid tribute to the Yongle Emperor of the Ming dynasty. Soon after that, Möngke Temür[c], chieftain of the Odoli clan of the Jianzhou Jurchens, defected from paying tribute to Korea, becoming a tributary state to China instead. Yi Seong-gye, the Taejo of Joseon, asked the Ming Empire to send Möngke Temür back but was refused.[16]: 120 The Yongle Emperor was determined to wrest the Jurchens out of Korean influence and have China dominate them instead.[51]: 29 [52] Korea tried to persuade Möngke Temür to reject the Ming overtures, but was unsuccessful, and Möngke Temür submitted to the Ming Empire.[53][51]: 30 Since then, more and more Jurchen tribes presented tribute to the Ming Empire in succession.[16]: 21 The Ming divided them into 384 guards,[12]: 15 and the Jurchen became vassals to the Ming Empire.[54] During the Ming dynasty, the name for the Jurchen land was Nurgan. The Jurchens became part of the Ming dynasty's Nurgan Regional Military Commission under the Yongle Emperor, with Ming forces erecting the Yongning Temple Stele in 1413, at the headquarters of Nurgan. The stele was inscribed in Chinese, Jurchen, Mongolian, and Tibetan.

In 1449, Mongol taishi Esen attacked the Ming Empire and captured the Zhengtong Emperor in Tumu. Some Jurchen guards in Jianzhou and Haixi cooperated with Esen's action,[11]: 185 but more were attacked in the Mongol invasion. Many Jurchen chieftains lost their hereditary certificates granted by the Ming government.[16]: 19 They had to present tribute as secretariats (中書舍人) with less reward from the Ming court than in the time when they were heads of guards – an unpopular development.[16]: 130 Subsequently, more and more Jurchens recognised the Ming Empire's declining power due to Esen's invasion. The Zhengtong Emperor's capture directly caused Jurchen guards to go out of control.[16]: 19, 21 Tribal leaders, such as Cungšan[d] and Wang Gao, brazenly plundered Ming territory. At about this time, the Jurchen script was officially abandoned.[55]: 120 More Jurchens adopted Mongolian as their writing language and fewer used Chinese.[56] The final recorded Jurchen writing dates to 1526.[57]

The Manchus are sometimes mistakenly identified as nomadic people.[58][59][60]: 24 note 1 The Manchu way of life (economy) was agricultural, farming crops and raising animals on farms.[61] Manchus practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the areas north of Shenyang.[62] The Haixi Jurchens were "semi-agricultural, the Jianzhou Jurchens and Maolian (毛憐) Jurchens were sedentary, while hunting and fishing was the way of life of the "Wild Jurchens".[63] Han Chinese society resembled that of the sedentary Jianzhou and Maolian, who were farmers.[64] Hunting, archery on horseback, horsemanship, livestock raising, and sedentary agriculture were all part of the Jianzhou Jurchens' culture.[65] Although Manchus practiced equestrianism and archery on horseback, their immediate progenitors practiced sedentary agriculture.[66]: 43 The Manchus also partook in hunting but were sedentary.[67] Their primary mode of production was farming while they lived in villages, forts, and walled towns. Their Jurchen Jin predecessors also practiced farming.[68]

Only the Mongols and the northern "wild" Jurchen were semi-nomadic, unlike the mainstream Jiahnzhou Jurchens descended from the Jin dynasty who were farmers that foraged, hunted, herded and harvested crops in the Liao and Yalu river basins. They gathered ginseng root, pine nuts, hunted for came pels in the uplands and forests, raised horses in their stables, and farmed millet and wheat in their fallow fields. They engaged in dances, wrestling and drinking strong liquor as noted during midwinter by the Korean Sin Chung-il when it was very cold. These Jurchens who lived in the north-east's harsh cold climate sometimes half sunk their houses in the ground which they constructed of brick or timber and surrounded their fortified villages with stone foundations on which they built wattle and mud walls to defend against attack. Village clusters were ruled by beile, hereditary leaders. They fought each other's and dispensed weapons, wives, slaves and lands to their followers in them. This was how the Jurchens who founded the Qing lived and how their ancestors lived before the Jin. Alongside Mongols and Jurchen clans there were migrants from Liaodong provinces of Ming China and Korea living among these Jurchens in a cosmopolitan manner. Nurhaci who was hosting Sin Chung-il was uniting all of them into his own army, having them adopt the Jurchen hairstyle of a long queue and a shaved fore=crown and wearing leather tunics. His armies had black, blue, red, white and yellow flags. These became the Eight Banners, initially capped to 4 then growing to 8 with three different types of ethnic banners as Han, Mongol and Jurchen were recruited into Nurhaci's forces. Jurchens like Nurhaci spoke both their native Tungusic language and Chinese, adopting the Mongol script for their own language unlike the Jin Jurchen's Khitan derived script. They adopted Confucian values and practiced their shamanist traditions.[69]

The Qing stationed the "New Manchu" Warka foragers in Ningguta and attempted to turn them into normal agricultural farmers but then the Warka just reverted to hunter gathering and requested money to buy cattle for beef broth. The Qing wanted the Warka to become soldier-farmers and imposed this on them but the Warka simply left their garrison at Ningguta and went back to the Sungari river to their homes to herd, fish and hunt. The Qing accused them of desertion.[70]

建州毛憐則渤海大氏遺孽,樂住種,善緝紡,飲食服用,皆如華人,自長白山迤南,可拊而治也。 "The (people of) Chien-chou and Mao-lin [YLSL always reads Mao-lien] are the descendants of the family Ta of Po-hai. They love to be sedentary and sew, and they are skilled in spinning and weaving. As for food, clothing and utensils, they are the same as (those used by) the Chinese. Those living south of the Ch'ang-pai mountain are apt to be soothed and governed."

魏焕《皇明九邊考》卷二《遼東鎮邊夷考》[71] Translation from Sino-Jürčed relations during the Yung-Lo period, 1403–1424 by Henry Serruys[72]

Although their Mohe ancestors did not respect dogs, the Jurchens began to respect dogs around the time of the Ming dynasty, and passed this tradition on to the Manchus. It was prohibited in Jurchen culture to use dog skin, and forbidden for Jurchens to harm, kill, or eat dogs. For political reasons, the Jurchen leader Nurhaci chose variously to emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with other peoples like the Mongols.[73]: 127 Nurhaci said to the Mongols that "the languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jušen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture. It was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism," since Nurhaci said to the Mongols: "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat, and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."[12]: 31

Manchu rule over China

[edit]

A century after the chaos started in the Jurchen lands, Nurhaci, a chieftain of the Jianzhou Left Guard who officially considered himself a local representative of imperial power of the Ming dynasty,[74] made efforts to unify the Jurchen tribes and established a military system called the "Eight Banners", which organized Jurchen soldiers into groups of "Bannermen", and ordered his scholar Erdeni and minister Gagai to create a new Jurchen script (later known as Manchu script) using the traditional Mongolian alphabet as a reference.[75]: 71, 88, 116, 137

When the Jurchens were reorganized by Nurhaci into the Eight Banners, many Manchu clans were artificially created as a group of unrelated people founded a new Manchu clan (mukun) using a geographic origin name such as a toponym for their hala (clan name).[76] The irregularities over Jurchen and Manchu clan origin led to the Qing trying to document and systematize the creation of histories for Manchu clans, including manufacturing an entire legend around the origin of the Aisin-Gioro clan by taking mythology from the northeast.[77]

In 1603, Nurhaci gained recognition as the Sure Kundulen Khan (Manchu: ᠰᡠᡵᡝ

ᡴᡠᠨᡩᡠᠯᡝᠨ

ᡥᠠᠨ, Möllendorff: sure kundulen han, Abkai: sure kundulen han, "wise and respected khan") from his Khalkha Mongol allies;[5]: 56 then, in 1616, he publicly enthroned himself and issued a proclamation naming himself Genggiyen Khan (Manchu: ᡤᡝᠩᡤᡳᠶᡝᠨ

ᡥᠠᠨ, Möllendorff: genggiyen han, Abkai: genggiyen han, "bright khan") of the Later Jin dynasty (Manchu: ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ, Möllendorff: aisin gurun, Abkai: aisin gurun, 後金).[e] Nurhaci then renounced the Ming overlordship with the Seven Grievances and launched his attack on the Ming dynasty[5]: 56 and moved the capital to Mukden after his conquest of Liaodong.[75]: 282 In 1635, his son and successor Hong Taiji changed the name of the Jurchen ethnic group (Manchu: ᠵᡠᡧᡝᠨ, Möllendorff: jušen, Abkai: juxen) to the Manchu.[78]: 330–331 A year later, Hong Taiji proclaimed himself the emperor of the Qing dynasty (Manchu: ᡩᠠᡳᠴᡳᠩ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ, Möllendorff: daicing gurun, Abkai: daiqing gurun[f]).[80]: 15 Factors for the change of name of these people from Jurchen to Manchu include the fact that the term "Jurchen" had negative connotations since the Jurchens had been in a servile position to the Ming dynasty for several hundred years, and it also referred to people of the "dependent class".[5]: 70 [81] The change of the name from Jurchen to Manchu was made to hide the fact that the ancestors of the Manchus, the Jianzhou Jurchens, had been ruled by the Chinese.[82][83][84][24]: 280 The Qing dynasty carefully hid the two original editions of the books of "Qing Taizu Wu Huangdi Shilu" and the "Manzhou Shilu Tu" (Taizu Shilu Tu) in the Qing palace, forbidden from public view because they showed that the Manchu Aisin-Gioro family had been ruled by the Ming dynasty.[85][86] In the Ming period, the Koreans of Joseon referred to the Jurchen inhabited lands north of the Korean peninsula, above the rivers Yalu and Tumen to be part of Ming China, as the "superior country" (sangguk) which they called Ming China.[87] The Qing deliberately excluded references and information that showed the Jurchens (Manchus) as subservient to the Ming dynasty, from the History of Ming to hide their former subservient relationship to the Ming. The Ming Veritable Records were not used to source content on Jurchens during Ming rule in the History of Ming because of this.[88]

In 1644, the Ming capital, Beijing, was sacked by a peasant revolt led by Li Zicheng, a former minor Ming official who became the leader of the peasant revolt, who then proclaimed the establishment of the Shun dynasty. The last Ming ruler, the Chongzhen Emperor, died by suicide by hanging himself when the city fell. When Li Zicheng moved against the Ming general Wu Sangui, the latter made an alliance with the Manchus and opened the Shanhai Pass to the Manchu army. After the Manchus defeated Li Zicheng, they moved the capital of their new Qing Empire to Beijing (Manchu: ᠪᡝᡤᡳᠩ, Möllendorff: beging, Abkai: beging[89]) in the same year.[80]: 19–20

The Qing government differentiated between Han Bannermen and ordinary Han civilians. Han Bannermen were Han Chinese who defected to the Qing Empire up to 1644 and joined the Eight Banners, giving them social and legal privileges in addition to being acculturated to Manchu culture. So many Han defected to the Qing Empire and swelled up the ranks of the Eight Banners that ethnic Manchus became a minority within the Banners, making up only 16% in 1648, with Han Bannermen dominating at 75% and Mongol Bannermen making up the rest.[90][91][92] It was this multi-ethnic, majority Han force in which Manchus were a minority, which conquered China for the Qing Empire.[93]

A mass marriage of Han Chinese officers and officials to Manchu women was organized to balance the massive number of Han women who entered the Manchu court as courtesans, concubines, and wives. These couples were arranged by Prince Yoto and Hong Taiji in 1632 to promote harmony between the two ethnic groups.[94]: 148 Also to promote ethnic harmony, a 1648 decree from the Shunzhi Emperor allowed Han Chinese civilian men to marry Manchu women from the Banners with the permission of the Board of Revenue if they were registered daughters of officials or commoners or the permission of their banner company captain if they were unregistered commoners. It was only later in the dynasty that these policies allowing intermarriage were done away with.[95][94]: 140

As a result of their conquest of Ming China, almost all the Manchus followed the prince regent Dorgon and the Shunzhi Emperor to Beijing and settled there.[96]: 134 [97]: 1 (Preface) A few of them were sent to other places such as Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet to serve as garrison troops.[97]: 1 (Preface) There were only 1524 Bannermen left in Manchuria at the time of the initial Manchu conquest.[96]: 18 After a series of border conflicts with the Russians, the Qing emperors started to realize the strategic importance of Manchuria and gradually sent Manchus back where they originally came from.[96]: 134 But throughout the Qing dynasty, Beijing was the focal point of the ruling Manchus in the political, economic and cultural spheres. The Yongzheng Emperor noted: "Garrisons are the places of stationed works, Beijing is their homeland."[98]: 1326

While the Manchu ruling elite at the Qing imperial court in Beijing and posts of authority throughout China increasingly adopted Han culture, the Qing imperial government viewed the Manchu communities (as well as those of various tribal people) in Manchuria as a place where traditional Manchu virtues could be preserved, and as a vital reservoir of military manpower fully dedicated to the regime.[99]: 182–184 The Qing emperors tried to protect the traditional way of life of the Manchus (as well as various other tribal peoples) in central and northern Manchuria by a variety of means. In particular, they restricted the migration of Han settlers to the region. This had to be balanced with practical needs, such as maintaining the defense of northern China against the Russians and the Mongols, supplying government farms with a skilled work force, and conducting trade in the region's products, which resulted in a continuous trickle of Han convicts, workers, and merchants to the northeast.[99]: 20–23, 78–90, 112–115

Han Chinese transfrontiersmen and other non-Jurchen origin people who joined the Later Jin very early were put into the Manchu Banners and were known as "Baisin" in Manchu, and not put into the Han Banners to which later Han Chinese were placed in.[100][101]: 82 An example was the Tokoro Manchu clan in the Manchu banners which claimed to be descended from a Han Chinese with the surname of Tao who had moved north from Zhejiang to Liaodong and joined the Jurchens before the Qing in the Ming Wanli emperor's era.[100][101]: 48 [102][103] The Han Chinese Banner Tong 佟 clan of Fushun in Liaoning falsely claimed to be related to the Jurchen Manchu Tunggiya 佟佳 clan of Jilin, using this false claim to get themselves transferred to a Manchu banner in the reign of the Kangxi emperor.[104]

Select groups of Han Chinese bannermen were mass transferred into Manchu Banners by the Qing, changing their ethnicity from Han Chinese to Manchu. Han Chinese bannermen of Tai Nikan (台尼堪, watchpost Chinese) and Fusi Nikan (撫順尼堪, Fushun Chinese)[5]: 84 backgrounds into the Manchu banners in 1740 by order of the Qing Qianlong emperor.[101]: 128 It was between 1618 and 1629 when the Han Chinese from Liaodong who later became the Fushun Nikan and Tai Nikan defected to the Jurchens (Manchus).[101]: 103–105 These Han Chinese origin Manchu clans continue to use their original Han surnames and are marked as of Han origin on Qing lists of Manchu clans.[105][106][107][108] The Fushun Nikan became Manchufied and the originally Han banner families of Wang Shixuan, Cai Yurong, Zu Dashou, Li Yongfang, Shi Tingzhu and Shang Kexi intermarried extensively with Manchu families.[109]

A Manchu Bannerman in Guangzhou called Hequan illegally adopted a Han Chinese named Zhao Tinglu, the son of former Han bannerman Zhao Quan, and gave him a new name, Quanheng in order that he be able to benefit from his adopted son receiving a salary as a Banner soldier.[110]

Commoner Manchu bannermen who were not nobility were called irgen which meant common, in contrast to the Manchu nobility of the "Eight Great Houses" who held noble titles.[77][111]

Manchu bannermen of the capital garrison in Beijing were said to be the worst militarily, unable to draw bows, unable to ride horses and fight properly and losing their Manchu culture.[112]

Manchu bannermen from the Xi'an banner garrison were praised for maintaining Manchu culture by Kangxi in 1703.[113] Xi'an garrison Manchus were said to retain Manchu culture far better than all other Manchus at martial skills in the provincial garrisons and they were able to draw their bows properly and perform cavalry archery unlike Beijing Manchus. The Qianlong emperor received a memorial staying Xi'an Manchu bannermen still had martial skills although not up to those in the past in a 1737 memorial from Cimbu.[114] By the 1780s, the military skills of Xi'an Manchu bannermen dropped enormously and they had been regarded as the most militarily skilled provincial Manchu banner garrison.[115] Manchu women from the Xi'an garrison often left the walled Manchu garrison and went to hot springs outside the city and gained bad reputations for their sexual lives. A Manchu from Beijing, Sumurji, was shocked and disgusted by this after being appointed Lieutenant general of the Manchu garrison of Xi'an and informed the Yongzheng emperor what they were doing.[116][117] Han civilians and Manchu bannermen in Xi'an had bad relations, with the bannermen trying to steal at the markets. Manchu Lieutenant general Cimbru reported this to Yongzheng emperor in 1729 after he was assigned there. Governor Yue Rui of Shandong was then ordered by the Yongzheng to report any bannerman misbehaving and warned him not to cover it up in 1730 after Manchu bannermen were put in a quarter in Qingzhou.[118] Manchu bannermen from the garrisons in Xi'an and Jingzhou fought in Xinjiang in the 1770s and Manchus from Xi'an garrison fought in other campaigns against the Dzungars and Uyghurs throughout the 1690s and 18th century. In the 1720s Jingzhou, Hangzhou and Nanjing Manchu banner garrisons fought in Tibet.[119]

For the over 200 years they lived next to each other, Han civilians and Manchu bannermen in Xi'an did not intermarry with each other at all.[120] In a book published in 1911 American sociologist Edward Alsworth Ross wrote of his visit to Xi'an just before the Xinhai revolution:"In Sianfu the Tartar quarter is a dismal picture of crumbling walls, decay, indolence and squalor. On the big drill grounds you see the runways along which the horseman gallops and shoots arrows at a target while the Tartar military mandarins look on. These lazy bannermen were tried in the new army but proved flabby and good-for-nothing; they would break down on an ordinary twenty-mile march. Battening on their hereditary pensions they have given themselves up to sloth and vice, and their poor chest development, small weak muscles, and diminishing families foreshadow the early dying out of the stock. Where is there a better illustration of the truth that parasitism leads to degeneration!"[121] Ross spoke highly of the Han and Hui population of Xi'an, Shaanxi and Gansu in general, saying: "After a fortnight of mule litter we sight ancient yellow Sianfu, "the Western capital," with its third of a million souls. Within the fortified triple gate the facial mold abruptly changes and the refined intellectual type appears. Here and there faces of a Hellenic purity of feature are seen and beautiful children are not uncommon. These Chinese cities make one realize how the cream of the population gathers in the urban centers. Everywhere town opportunities have been a magnet for the élite of the open country."[122]

The Qing dynasty altered its law on intermarriage between Han civilians and Manchu bannermen several times in the dynasty. At the beginning of the Qing dynasty, the Qing allowed Han civilians to marry Manchu women. Then the Qing banned civilians from marrying women from the Eight banners later. In 1865, the Qing allowed Han civilian men to marry Manchu bannerwomen in all garrisons except the capital garrison of Beijing. There was no formal law on marriage between people in the different banners like the Manchu and Han banners but it was informally regulated by social status and custom. In northeastern China such as Heilongjiang and Liaoning it was more common for Manchu women to marry Han men since they were not subjected to the same laws and institutional oversight as Manchus and Han in Beijing and elsewhere.[123]

The policy of artificially isolating the Manchus of the northeast from the rest of China could not last forever. In the 1850s, large numbers of Manchu bannermen were sent to central China to fight the Taiping rebels. (For example, just the Heilongjiang province – which at the time included only the northern part of today's Heilongjiang – contributed 67,730 bannermen to the campaign, of whom only 10–20% survived).[99]: 117 Those few who returned were demoralized and often disposed to opium addiction.[99]: 124–125 In 1860, in the aftermath of the loss of Outer Manchuria, and with the imperial and provincial governments in deep financial trouble, parts of Manchuria became officially open to Chinese settlement;[99]: 103, sq within a few decades, the Manchus became a minority in most of Manchuria's districts.

Modern times

[edit]

The majority of the hundreds of thousands of people living in inner Beijing during the Qing were Manchus and Mongol bannermen from the Eight Banners after they were moved there in 1644, since Han Chinese were expelled and not allowed to re-enter the inner part of the city.[124][125][126] Only after the "Hundred Days Reform", during the reign of emperor Guangxu, were Han were allowed to re-enter inner Beijing.[126]

Many Manchu Bannermen in Beijing supported the Boxers in the Boxer Rebellion and shared their anti-foreign sentiment.[77] The Manchu Bannermen were devastated by the fighting during the First Sino-Japanese War and the Boxer Rebellion, sustaining massive casualties during the wars and subsequently being driven into extreme suffering and hardship.[127]: 80 Much of the fighting in the Boxer Rebellion against the foreigners in defense of Beijing and Manchuria was done by Manchu Banner armies, which were destroyed while resisting the invasion. The German Minister Clemens von Ketteler was assassinated by a Manchu.[128]: 72 Thousands of Manchus fled south from Aigun during the fighting in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, their cattle and horses then stolen by Russian Cossacks who razed their villages and homes.[129]: 4 The clan system of the Manchus in Aigun was obliterated by the despoliation of the area at the hands of the Russian invaders.[130]

By the 19th century, most Manchus in the city garrison spoke only Mandarin Chinese, not Manchu, which still distinguished them from their Han neighbors in southern China, who spoke non-Mandarin dialects. That they spoke Beijing dialect made recognizing Manchus folks relatively easy.[127]: 204 [128]: 204 It was northern Standard Chinese which the Manchu Bannermen spoke instead of the local dialect the Han people around the garrison spoke, so that Manchus in the garrisons at Jingzhou and Guangzhou both spoke Beijing Mandarin even though Cantonese was spoken at Guangzhou, and the Beijing dialect of Mandarin distinguished the Manchu bannermen at the Xi'an garrison from the local Han people who spoke the Xi'an dialect of Mandarin.[127]: 42 [128]: 42 Many Bannermen got jobs as teachers, writing textbooks for learning Mandarin and instructing people in Mandarin.[131]: 69 In Guangdong, the Manchu Mandarin teacher Sun Yizun advised that the Yinyun Chanwei and Kangxi Zidian, dictionaries issued by the Qing government, were the correct guides to Mandarin pronunciation, rather than the pronunciation of the Beijing and Nanjing dialects.[131]: 51

In the late 19th century and early 1900s, intermarriage between Manchus and Han bannermen in the northeast increased as Manchu families were more willing to marry their daughters to sons from well off Han families to trade their ethnic status for higher financial status.[132] Most intermarriage consisted of Han Bannermen marrying Manchus in areas like Aihun.[127]: 263 Han Chinese Bannermen wedded Manchus and there was no law against this.[133]

As the end of the Qing dynasty approached, Manchus were portrayed as outside colonizers by Chinese nationalists such as Sun Yat-sen, even though the Republican revolution he brought about was supported by many reform-minded Manchu officials and military officers.[128]: 265 This portrayal dissipated somewhat after the 1911 revolution as the new Republic of China now sought to include Manchus within its national identity.[128]: 275 In order to blend in, some Manchus switched to speaking the local dialect instead of Standard Chinese.[127]: 270 [128]: 270

By the early years of the Republic of China, very few areas of China still had traditional Manchu populations. Among the few regions where such comparatively traditional communities could be found, and where the Manchu language was still widely spoken, were the Aigun (Manchu: ᠠᡳᡥᡡᠨ, Möllendorff: aihūn, Abkai: aihvn) District and the Qiqihar (Manchu: ᠴᡳᠴᡳᡤᠠᡵ, Möllendorff: cicigar, Abkai: qiqigar) District of Heilongjiang Province.[129]: i, 3–4

Until 1924, the Chinese government continued to pay stipends to Manchu bannermen, but many cut their links with their banners and took on Han-style names to avoid persecution.[128]: 270 The official total of Manchus fell by more than half during this period, as they refused to admit their ethnicity when asked by government officials or other outsiders.[128]: 270, 283 On the other hand, in warlord Zhang Zuolin's reign in Manchuria, much better treatment was reported.[134]: 157 [11]: 153 There was no particular persecution of Manchus.[134]: 157 Even the mausoleums of Qing emperors were still allowed to be managed by Manchu guardsmen, as in the past.[134]: 157 Many Manchus joined the Fengtian clique, such as Xi Qia, a member of the Qing dynasty's imperial clan.

As a follow-up to the Mukden Incident, Manchukuo, a puppet state in Manchuria, was created by the Empire of Japan which was nominally ruled by the deposed Last Emperor, Puyi, in 1932. Although the nation's name implied a primarily Manchu affiliation, it was actually a completely new country for all the ethnicities in Manchuria,[135][134]: 160 which had a majority Han population and was opposed by many Manchus as well as people of other ethnicities who fought against Japan in the Second Sino-Japanese War.[11]: 185 The Japanese Ueda Kyōsuke labeled all 30 million people in Manchuria "Manchus", including Han Chinese, even though most of them were not ethnic Manchu, and the Japanese-written "Great Manchukuo" built upon Ueda's argument to claim that all 30 million "Manchus" in Manchukuo had the right to independence to justify splitting Manchukuo from China.[136]: 2000 In 1942, the Japanese-written "Ten Year History of the Construction of Manchukuo" attempted to emphasize the right of ethnic Japanese to the land of Manchukuo while attempting to delegitimize the Manchus' claim to Manchukuo as their native land, noting that most Manchus moved out during the Qing dynasty and only returned later.[136]: 255

In 1952, after the failure of both Manchukuo and the Nationalist Government (KMT), the newborn People's Republic of China officially recognized the Manchu as one of the ethnic minorities as Mao Zedong had criticized the Han chauvinism that dominated the KMT.[128]: 277 In the 1953 census, 2.5 million people identified themselves as Manchu.[128]: 276 The Communist government also attempted to improve the treatment of Manchu people; some Manchu people who had hidden their ancestry during the period of KMT rule became willing to reveal their ancestry, such as the writer Lao She, who began to include Manchu characters in his fictional works in the 1950s.[128]: 280 Between 1982 and 1990, the official count of Manchu people more than doubled from 4,299,159 to 9,821,180, making them China's fastest-growing ethnic minority,[128]: 282 but this growth was only on paper, as this was due to people formerly registered as Han applying for official recognition as Manchu.[128]: 283 Since the 1980s, thirteen Manchu autonomous counties have been created in Liaoning, Jilin, Hebei, and Heilongjiang.[137]

The Eight Banners system is one of the most important ethnic identity of today's Manchu people.[5]: 43 So nowadays, Manchus are more like an ethnic coalition which not only contains the descendants of Manchu bannermen, also has a large number of Manchu-assimilated Chinese and Mongol bannermen.[138][139][140][134]: 5 (Preface) However, Solon and Sibe Bannermen who were considered as part of Eight Banner system under the Qing dynasty were registered as independent ethnic groups by the PRC government as Daur, Evenk, Nanai, Oroqen, and Sibe.[128]: 295

Since the 1980s, the reform after Cultural Revolution, there has been a renaissance of Manchu culture and language among the government, scholars and social activities with remarkable achievements.[11]: 209, 215, 218–228 It was also reported that the resurgence of interest also spread among Han Chinese.[141] In modern China, Manchu culture and language preservation is promoted by the Chinese Communist Party, and Manchus once again form one of the most socioeconomically advanced minorities within China.[142] Manchus generally face little to no discrimination in their daily lives, there is however, a remaining anti-Manchu sentiment amongst Han nationalist conspiracy theorists. It is particularly common with participants of the Hanfu movement who subscribe to conspiracy theories about Manchu people, such as the Chinese Communist Party being occupied by Manchu elites hence the better treatment Manchus receive under the People's Republic of China in contrast to their persecution under the KMT's Republic of China rule.[143]

Manchus were subjected to the same one child policy and rules as Han people. Manchus, Koreans, Russians, Hui and Mongols in Inner Mongolia were subjected to restrictions of two children.[144]

Population

[edit]Mainland China

[edit]Most Manchu people now live in Mainland China with a population of 10,410,585,[1] which is 9.28% of ethnic minorities and 0.77% of China's total population.[1] Among the provincial regions, there are two provinces, Liaoning and Hebei, which have over 1,000,000 Manchu residents.[1] However, as mentioned earlier, the modern population of Manchus has been artificially inflated because Han Chinese of the Eight Banner System, including booi bondservants, are allowed to register as Manchu in modern China. Liaoning has 5,336,895 Manchu residents which is 51.26% of Manchu population and 12.20% provincial population; Hebei has 2,118,711 which is 20.35% of Manchu people and 70.80% of provincial ethnic minorities.[1] Manchus are the largest ethnic minority in Liaoning, Hebei, Heilongjiang and Beijing; 2nd largest in Jilin, Inner Mongolia, Tianjin, Ningxia, Shaanxi and Shanxi and 3rd largest in Henan, Shandong and Anhui.[1]

Distribution

[edit]| Rank | Region | Total Population |

Manchu | Percentage in Manchu Population |

Percentage in the Population of Ethnic Minorities (%) |

Regional Percentage of Population |

Regional Rank of Ethnic Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,335,110,869 | 10,410,585 | 100 | 9.28 | 0.77 | ||

| Total (in all 31 provincial regions) |

1,332,810,869 | 10,387,958 | 99.83 | 9.28 | 0.78 | ||

| G1 | Northeast | 109,513,129 | 6,951,280 | 66.77 | 68.13 | 6.35 | |

| G2 | North | 164,823,663 | 3,002,873 | 28.84 | 32.38 | 1.82 | |

| G3 | East | 392,862,229 | 122,861 | 1.18 | 3.11 | 0.03 | |

| G4 | South Central | 375,984,133 | 120,424 | 1.16 | 0.39 | 0.03 | |

| G5 | Northwest | 96,646,530 | 82,135 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.08 | |

| G6 | Southwest | 192,981,185 | 57,785 | 0.56 | 0.15 | 0.03 | |

| 1 | Liaoning | 43,746,323 | 5,336,895 | 51.26 | 80.34 | 12.20 | 2nd |

| 2 | Hebei | 71,854,210 | 2,118,711 | 20.35 | 70.80 | 2.95 | 2nd |

| 3 | Jilin | 27,452,815 | 866,365 | 8.32 | 39.64 | 3.16 | 3rd |

| 4 | Heilongjiang | 38,313,991 | 748,020 | 7.19 | 54.41 | 1.95 | 2nd |

| 5 | Inner Mongolia | 24,706,291 | 452,765 | 4.35 | 8.96 | 2.14 | 3rd |

| 6 | Beijing | 19,612,368 | 336,032 | 3.23 | 41.94 | 1.71 | 2nd |

| 7 | Tianjin | 12,938,693 | 83,624 | 0.80 | 25.23 | 0.65 | 3rd |

| 8 | Henan | 94,029,939 | 55,493 | 0.53 | 4.95 | 0.06 | 4th |

| 9 | Shandong | 95,792,719 | 46,521 | 0.45 | 6.41 | 0.05 | 4th |

| 10 | Guangdong | 104,320,459 | 29,557 | 0.28 | 1.43 | 0.03 | 9th |

| 11 | Shanghai | 23,019,196 | 25,165 | 0.24 | 9.11 | 0.11 | 5th |

| 12 | Ningxia | 6,301,350 | 24,902 | 0.24 | 1.12 | 0.40 | 3rd |

| 13 | Guizhou | 34,748,556 | 23,086 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.07 | 18th |

| 14 | Xinjiang | 21,815,815 | 18,707 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 10th |

| 15 | Jiangsu | 78,660,941 | 18,074 | 0.17 | 4.70 | 0.02 | 7th |

| 16 | Shaanxi | 37,327,379 | 16,291 | 0.16 | 8.59 | 0.04 | 3rd |

| 17 | Sichuan | 80,417,528 | 15,920 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.02 | 10th |

| 18 | Gansu | 25,575,263 | 14,206 | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 7th |

| 19 | Yunnan | 45,966,766 | 13,490 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 24th |

| 20 | Hubei | 57,237,727 | 12,899 | 0.12 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 6th |

| 21 | Shanxi | 25,712,101 | 11,741 | 0.11 | 12.54 | 0.05 | 3rd |

| 22 | Zhejiang | 54,426,891 | 11,271 | 0.11 | 0.93 | 0.02 | 13th |

| 23 | Guangxi | 46,023,761 | 11,159 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 12th |

| 24 | Anhui | 59,500,468 | 8,516 | 0.08 | 2.15 | 0.01 | 4th |

| 25 | Fujian | 36,894,217 | 8,372 | 0.08 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 10th |

| 26 | Qinghai | 5,626,723 | 8,029 | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 7th |

| 27 | Hunan | 65,700,762 | 7,566 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 9th |

| 28 | Jiangxi | 44,567,797 | 4,942 | 0.05 | 2.95 | 0.01 | 6th |

| 29 | Chongqing | 28,846,170 | 4,571 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 7th |

| 30 | Hainan | 8,671,485 | 3,750 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 8th |

| 31 | Tibet | 3,002,165 | 718 | <0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 11th |

| Active Servicemen | 2,300,000 | 22,627 | 0.24 | 23.46 | 1.05 | 2nd |

Manchu autonomous regions

[edit]| Manchu Ethnic Town/Township |

Province Autonomous area Municipality |

City Prefecture |

County |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paifang Hui and Manchu Ethnic Township | Anhui | Hefei | Feidong |

| Labagoumen Manchu Ethnic Township | Beijing | N/A | Huairou |

| Changshaoying Manchu Ethnic Township | Beijing | N/A | Huairou |

| Huangni Yi, Miao and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Dafang |

| Jinpo Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Qianxi |

| Anluo Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Jinsha |

| Xinhua Miao, Yi and Manchu Ethnic Township | Guizhou | Bijie | Jinsha |

| Tangquan Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Xixiaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Dongling Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Tangshan | Zunhua |

| Lingyunce Manchu and Hui Ethnic Township | Hebei | Baoding | Yi |

| Loucun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Baoding | Laishui |

| Daweihe Hui and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Langfang | Wen'an |

| Pingfang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Anchungou Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Wudaoyingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Zhengchang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Mayingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Fujiadianzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xiaoying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Datun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Xigou Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Luanping |

| Gangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Chengde |

| Liangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Chengde |

| Bagualing Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Xinglong |

| Nantianmen Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Xinglong |

| Yinjiaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Miaozigou Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Badaying Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Taipingzhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Jiutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Xi'achao Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Baihugou Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Longhua |

| Liuxi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Qijiadai Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Pingfang Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Maolangou Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Xuzhangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Nanwushijia Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Guozhangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Hebei | Chengde | Pingquan |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Nangang |

| Xingfu Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lequn Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Tongxin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Xiqin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Gongzheng Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lianxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Xinxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Qingling Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Nongfeng Manchu and Xibe Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Yuejin Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Shuangcheng |

| Lalin Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Niujia Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Yingchengzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Shuangqiaozi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Wuchang |

| Liaodian Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Harbin | Acheng |

| Shuishiying Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Ang'angxi |

| Youyi Daur, Kirgiz and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Fuyu |

| Taha Manchu and Daur Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Qiqihar | Fuyu |

| Jiangnan Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Mudanjiang | Ning'an |

| Chengdong Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Mudanjiang | Ning'an |

| Sijiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Heihe | Aihui |

| Yanjiang Daur and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Heihe | Sunwu |

| Suisheng Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Yong'an Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Hongqi Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Beilin |

| Huiqi Manchu Ethnic Town | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Xiangbai Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Lingshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Suihua | Wangkui |

| Fuxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Hegang | Suibin |

| Chengfu Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Heilongjiang | Shuangyashan | Youyi |

| Longshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Siping | Gongzhuling |

| Ershijiazi Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Siping | Gongzhuling |

| Sanjiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Yanbian | Hunchun |

| Yangpao Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Yanbian | Hunchun |

| Wulajie Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Jilin City | Longtan |

| Dakouqin Manchu Ethnic Town | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Liangjiazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Jinjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Tuchengzi Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Jilin City | Yongji |

| Jindou Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Tonghua County |

| Daquanyuan Korean and Manchu Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Tonghua County |

| Xiaoyang Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Tonghua | Meihekou |

| Sanhe Manchu and Korean Ethnic Township | Jilin | Liaoyuan | Dongfeng County |

| Mantang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Dongling |

| Liushutun Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Shajintai Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Dongsheng Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Liangguantun Mongol and Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Shenyang | Kangping |

| Shihe Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Dalian | Jinzhou |

| Qidingshan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Jinzhou |

| Taling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Gaoling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Guiyunhua Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Sanjiashan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Zhuanghe |

| Yangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Santai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Laohutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dalian | Wafangdian |

| Dagushan Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Anshan | Qianshan |

| Songsantaizi Korean and Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Anshan | Qianshan |

| Lagu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Fushun | Fushun County |

| Tangtu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Fushun | Fushun County |

| Sishanling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Benxi | Nanfen |

| Xiamatang Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Benxi | Nanfen |

| Huolianzhai Hui and Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Benxi | Xihu |

| Helong Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Dandong | Donggang |

| Longwangmiao Manchu and Xibe Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Dandong | Donggang |

| Juliangtun Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Jiudaoling Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Dizangsi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Hongqiangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Liulonggou Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Shaohuyingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Dadingpu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Toutai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Toudaohe Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Chefang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Wuliangdian Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Yi |

| Baichanmen Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Heishan |

| Zhen'an Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Heishan |

| Wendilou Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Linghai |

| Youwei Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Jinzhou | Linghai |

| East Liujiazi Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Fuxin | Zhangwu |

| West Liujiazi Manchu and Mongol Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Fuxin | Zhangwu |

| Jidongyu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Shuiquan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Tianshui Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Liaoyang | Liaoyang County |

| Quantou Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Tieling | Changtu County |

| Babaotun Manchu, Xibe and Korean Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Huangqizhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Shangfeidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Xiafeidi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Linfeng Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Kaiyuan |

| Baiqizhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Tieling County |

| Hengdaohezi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Tieling County |

| Chengping Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Dexing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Helong Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Jinxing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Mingde Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Songshu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Yingcheng Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Tieling | Xifeng |

| Xipingpo Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Dawangmiao Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Fanjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gaodianzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gejia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Huangdi Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Huangjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Kuanbang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Mingshui Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Shahe Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Wanghu Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Xiaozhuangzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Yejia Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Gaotai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Suizhong |

| Baita Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Caozhuang Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Dazhai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Dongxinzhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Gaojialing Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Guojia Manchu Ethnic Town | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Haibin Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Hongyazi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jianjin Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jianchang Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Jiumen Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Liutaizi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Nandashan Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Shahousuo Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Wanghai Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Weiping Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Wenjia Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yang'an Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yaowangmiao Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Yuantaizi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Xingcheng |

| Erdaowanzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Jianchang |

| Xintaimen Manchu Ethnic Township | Liaoning | Huludao | Lianshan |

| Manzutun Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Hinggan | Horqin Right Front Banner |

| Guanjiayingzi Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Chifeng | Songshan |

| Shijia Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Chifeng | Harqin Banner |

| Caonian Manchu Ethnic Township | Inner Mongolia | Ulanqab | Liangcheng |

| Sungezhuang Manchu Ethnic Township | Tianjin | N/A | Ji |

-

Manchu autonomous area in Liaoning.[g]

-

Manchu autonomous area in Jilin.

-

Manchu autonomous area in Hebei.

Other areas

[edit]Manchu people can be found living outside mainland China. There are approximately 12,000 Manchus now in Taiwan. Most of them moved to Taiwan with the ROC government in 1949. One notable example was Puru, a famous painter, calligrapher and also the founder of the Manchu Association of Republic of China.

Culture

[edit]Influence on other Tungusic peoples

[edit]The Manchus implemented measures to "Manchufy" the other Tungusic peoples living around the Amur River basin.[66]: 38 The southern Tungusic Manchus influenced the northern Tungusic peoples linguistically, culturally, and religiously.[66]: 242

Language and alphabet

[edit]Language

[edit]

The Manchu language is a Tungusic language and has many dialects. Standard Manchu originates from the accent of Jianzhou Jurchens[145]: 246 and was officially standardized during the Qianlong Emperor's reign.[23]: 40 During the Qing dynasty, Manchus at the imperial court were required to speak Standard Manchu or face the emperor's reprimand.[145]: 247 This applied equally to the palace presbyter for shamanic rites when performing sacrifice.[145]: 247

After the 19th century, most Manchus had perfected Standard Chinese and the number of Manchu speakers was dwindling.[23]: 33 Although the Qing emperors emphasized the importance of the Manchu language again and again, the tide could not be turned. After the Qing dynasty collapsed, the Manchu language lost its status as a national language and its official use in education ended. Manchus today generally speak Standard Chinese. The remaining skilled native Manchu speakers number less than 100,[h][150] most of whom are to be found in Sanjiazi (Manchu: ᡳᠯᠠᠨ

ᠪᠣᡠ, Möllendorff: ilan boo, Abkai: ilan bou), Heilongjiang Province.[151] Since the 1980s, there has been a resurgence of the Manchu language among the government, scholars and social activists.[11]: 218 In recent years, with the help of the governments in Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang, many schools started to have Manchu classes.[152][153][154] There are also Manchu volunteers in many places of China who freely teach Manchu in the desire to rescue the language.[155][156][157][158] Thousands of non-Manchus have learned the language through these platforms.[147][159][160]

Today, in an effort to save Manchu culture from extinction, the older generation of Manchus are spending their time to teach young people; as an effort to encourage learners, these classes are often free. They teach through the Internet and even mail Manchu textbooks for free, all for the purpose of protecting the national cultural traditions.[161]

Alphabet

[edit]The Jurchens, ancestors of the Manchus, had created Jurchen script in the Jin dynasty. After the Jin dynasty collapsed, the Jurchen script was gradually lost. In the Ming dynasty, 60–70% of Jurchens used Mongolian script to write letters and 30–40% of Jurchens used Chinese characters.[56] This persisted until Nurhaci revolted against the Ming Empire. Nurhaci considered it a major impediment that his people lacked a script of their own, so he commanded his scholars, Gagai and Eldeni, to create Manchu characters by reference to Mongolian scripts.[162]: 4 They dutifully complied with the Khan's order and created Manchu script, which is called "script without dots and circles" (Manchu: ᡨᠣᠩᡴᡳ

ᡶᡠᡴᠠ

ᠠᡴᡡ

ᡥᡝᡵᡤᡝᠨ, Möllendorff: tongki fuka akū hergen, Abkai: tongki fuka akv hergen; 无圈点满文) or "old Manchu script" (老满文).[97]: 3 (Preface) Due to its hurried creation, the script has its defects. Some vowels and consonants were difficult to distinguish.[98]: 5324–5327 [23]: 11–17 Shortly afterwards, their successor Dahai used dots and circles to distinguish vowels, aspirated and non-aspirated consonants and thus completed the script. His achievement is called "script with dots and circles" or "new Manchu script".[163]

Traditional lifestyle

[edit]The Manchu are often mistakenly labelled a nomadic people,[58] but they were sedentary agricultural people who lived in fixed villages, farmed crops and practiced hunting and mounted archery.[60]: 24 note 1

The southern Tungusic Manchu farming sedentary lifestyle was very different from the nomadic hunter gatherer forager lifestyle of their more northern Tungusic relatives like the Warka, which caused the Qing state to attempt to sedentarize them and adopt the farming lifestyle of the Manchus.[70][164]

Names and naming practices

[edit]Family names

[edit]

The history of Manchu family names is quite long. Fundamentally, it succeeds the Jurchen family name of the Jin dynasty.[134]: 109 However, after the Mongols extinguished the Jin dynasty, the Manchus started to adopt Mongol culture, including their custom of using only their given name until the end of the Qing dynasty,[134]: 107 a practice confounding non-Manchus, leading them to conclude, erroneously, that they simply do not have family names.[145]: 969

A Manchu family name usually has two portions: the first is "Mukūn" (ᠮᡠᡴᡡᠨ, Abkai: Mukvn) which literally means "branch name"; the second, "Hala" (ᡥᠠᠯᠠ), represents the name of a person's clan.[145]: 973 According to the Book of the Eight Manchu Banners' Surname-Clans (八旗滿洲氏族通譜), there are 1,114 Manchu family names. Gūwalgiya, Niohuru, Hešeri, Šumulu, Tatara, Gioro, Nara are considered as "famous clans" (著姓) among Manchus.[165]

There were stories of Han migrating to the Jurchens and assimilating into Manchu Jurchen society and Nikan Wailan may have been an example of this.[166] The Manchu Cuigiya (崔佳氏) clan claimed that a Han Chinese founded their clan.[167] The Tohoro (托活络) clan (Duanfang's clan) claimed Han Chinese origin.[103][168][169][101]: 48 [170]

Given names

[edit]Manchus given names are distinctive. Generally, there are several forms, such as bearing suffixes "-ngga", "-ngge" or "-nggo", meaning "having the quality of";[145]: 979 bearing Mongol style suffixes "-tai" or "-tu", meaning "having";[5]: 243 [145]: 978 bearing the suffix, "-ju", "-boo";[5]: 243 numerals[5]: 243 [145]: 978 [i]} or animal names.[145]: 979 [5]: 243 [j]}

Some ethnic names can also be a given name of the Manchus. One of the common first name for the Manchus is Nikan, which is also a Manchu exonym for the Han Chinese.[5]: 242 For example, Nikan Wailan was a Jurchen leader who was an enemy of Nurhaci.[101]: 172 [60]: 49 [171] Nikan was also the name of one of the Aisin-Gioro princes and grandsons of Nurhaci who supported Prince Dorgon.[66]: 99 [60]: 902 [172] Nurhaci's first son was Cuyen, one of whose sons was Nikan.[173]

Current status

[edit]Nowadays, Manchus primarily use Chinese family and given names, but some still use a Manchu family name and Chinese given name,[k] a Chinese family name and Manchu given name[l] or both Manchu family and given names.[m]

Burial customs

[edit]The Jurchens and their Manchu descendants originally practiced cremation as part of their culture. They adopted the practice of burial from the Han Chinese, but many Manchus continued to cremate their dead.[5]: 264 Princes were cremated on pyres.[174]

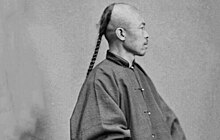

Traditional hairstyle

[edit]

The traditional hairstyle for Manchu men is shaving the front of their heads while growing the hair on the back of their heads into a single braid called a queue (辮子; biànzi), which was known as soncoho in Manchu. During the Qing dynasty, the queue was legally mandated for male Ming Chinese subjects in the Qing Empire. The Ming were to shave their foreheads and begin growing the queue within ten days of the order, if they refused to comply they were executed for treason. Throughout the rest of the Qing dynasty, the queue was seen as a submission of loyalty, as it showed who had submitted to the dynasty and who had not. As the Qing dynasty came to an end, the hairstyle shifted from a symbol of loyalty to a symbol of feudalism and this led many men to cut off their cues as a statement of rebellion. These acts gave China a step toward modernization and moved it away from imperial rule as China began to adopt more of Western culture, including fashion and appearance.

Manchu women wore their hair in a distinctive hairstyle called liangbatou (兩把頭).

Traditional garments

[edit]

A common misconception among Han Chinese was that Manchu clothing was entirely separate from Hanfu.[66] In fact, Manchu clothes were simply modified Ming Hanfu but the Manchus promoted the misconception that their clothing was of different origin.[66] Manchus originally did not have their own cloth or textiles and the Manchus had to obtain Ming dragon robes and cloth when they paid tribute to the Ming dynasty or traded with the Ming. The Manchus modified the Ming robes to be narrow at the sleeves by adding a new fur cuff and by cutting slits in the skirt to make it more slender for falconry, horse riding and archery.[175]: 157 The robe's jacket waist had a new strip of scrap cloth put on the waist while the waist was made snug by pleating the top of the skirt on the robe.[175]: 159 The Manchus added sable fur skirts, cuffs and collars to Ming dragon robes and trimming sable fur all over them before wearing them.[176] Han Chinese court costume was modified by Manchus through adding a ceremonial big collar (da-ling) or shawl collar (pijian-ling).[177] It was mistakenly thought that the hunting ancestors of the Manchus skin clothes became Qing dynasty clothing, due to the contrast between Ming dynasty clothes unshaped cloth's straight length contrasting to the odd-shaped pieces of Qing dynasty long pao and chao fu. Scholars from the west wrongly thought they were purely Manchu. Chao fu robes from Ming dynasty tombs like the Wanli emperor's tomb were excavated and it was found that Qing chao fu was similar and derived from it. They had embroidered or woven dragons on them but are different from long pao dragon robes which are a separate clothing. Flaired skirt with right side fastenings and fitted bodices dragon robes have been found[178]: 103 in Beijing, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Shandong tombs of Ming officials and Ming imperial family members. Integral upper sleeves of Ming chao fu had two pieces of cloth attached on Qing chao fu just like earlier Ming chao fu that had sleeve extensions with another piece of cloth attached to the bodice's integral upper sleeve. Another type of separate Qing clothing, the long pao resembles Yuan dynasty clothing like robes found in the Shandong tomb of Li Youan during the Yuan dynasty. The Qing dynasty chao fu appear in official formal portraits while Ming dynasty chao fu that they derive from do not, perhaps indicating the Ming officials and imperial family wore chao fu under their formal robes since they appear in Ming tombs but not portraits. Qing long pao were similar unofficial clothing during the Qing dynasty.[178]: 104 The Yuan robes had hems flared and around the arms and torso they were tight. Qing unofficial clothes, long pao, derived from Yuan dynasty clothing while Qing official clothing, chao fu, derived from unofficial Ming dynasty clothing, dragon robes. The Ming consciously modeled their clothing after that of earlier Han Chinese dynasties like the Song dynasty, Tang dynasty and Han dynasty. In Japan's Nara city, the Todaiji temple's Shosoin repository has 30 short coats (hanpi) from Tang dynasty China. Ming dragon robes derive from these Tang dynasty hanpi in construction. The hanpi skirt and bodice are made of different cloth with different patterns on them and this is where the Qing chao fu originated.[178]: 105 Cross-over closures are present in both the hanpi and Ming garments. The eighth century Shosoin hanpi's variety show it was in vogue at the time and most likely derived from much more ancient clothing. Han dynasty and Jin dynasty (266–420) era tombs in Yingban, to the Tianshan mountains south in Xinjiang have clothes resembling the Qing long pao and Tang dynasty hanpi. The evidence from excavated tombs indicates that China had a long tradition of garments that led to the Qing chao fu and it was not invented or introduced by Manchus in the Qing dynasty or Mongols in the Yuan dynasty. The Ming robes that the Qing chao fu derived from were just not used in portraits and official paintings but were deemed as high status to be buried in tombs. In some cases the Qing went further than the Ming dynasty in imitating ancient China to display legitimacy with resurrecting ancient Chinese rituals to claim the Mandate of Heaven after studying Chinese classics. Qing sacrificial ritual vessels deliberately resemble ancient Chinese ones even more than Ming vessels.[178]: 106 Tungusic people on the Amur river like Udeghe, Ulchi and Nanai adopted Chinese influences in their religion and clothing with Chinese dragons on ceremonial robes, scroll and spiral bird and monster mask designs, Chinese New Year, using silk and cotton, iron cooking pots, and heated house from China during the Ming dynasty.[179]

The Spencer Museum of Art has six long pao robes that belonged to Han Chinese nobility of the Qing dynasty (Chinese nobility).[178]: 115 Ranked officials and Han Chinese nobles had two slits in the skirts while Manchu nobles and the Imperial family had four slits in skirts. All first, second and third rank officials as well as Han Chinese and Manchu nobles were entitled to wear nine dragons by the Qing Illustrated Precedents. Qing sumptuary laws only allowed four clawed dragons for officials, Han Chinese nobles and Manchu nobles while the Qing Imperial family, emperor and princes up to the second degree and their female family members were entitled to wear five clawed dragons. However officials violated these laws all the time and wore five clawed dragons and the Spencer Museum's six long pao worn by Han Chinese nobles have five clawed dragons on them.[178]: 117

The early phase of Manchu clothing succeeded from Jurchen tradition. White was the dominating color.[180]To facilitate convenience during archery, the robe is the most common article of clothing for the Manchu people.[181]: 17 Over the robe, a surcoat is usually worn, derived from the military uniform of Eight Banners army.[181]: 30 During the Kangxi period, the surcoat gained popularity among commoners.[181]: 31 The modern Chinese suits, the Cheongsam and Tangzhuang, are derived from the Manchu robe and surcoat[181]: 17 which are commonly considered as "Chinese elements".[182]

Wearing hats is also a part of traditional Manchu culture.[181]: 27 Hats are worn by all ages throughout all seasons, which contrasts the Han Chinese culture of "Starting to wear hats at 20-year-old" (二十始冠).[181]: 27 Manchu hats are either formal or casual, formal hats being made in two different styles, straw for spring and summer, and fur for fall and winter.[181]: 28 Casual hats are more commonly known as "Mandarin hats" in English.[181]

Manchus have many distinctive traditional accessories. Women traditionally wear three earrings on each ear,[183] a tradition that is maintained by many older Manchu women.[184] Males also traditionally wear piercings, but they tend to only have one earring in their youth and do not continue to wear it as adults.[134]: 20 The Manchu people also have traditional jewelry which evokes their past as hunters. The fergetun (ᡶᡝᡵᡤᡝᡨᡠᠨ), a thumb ring traditionally made out of reindeer bone, was worn to protect the thumbs of archers. After the establishment of the Qing dynasty in 1644, the fergetun gradually became a form of jewelry, with the most valuable ones made in jade and ivory.[185] High-heeled shoes were worn by Manchu women.[183]

Traditional activities

[edit]Riding and archery

[edit]

Riding and archery (Manchu: ᠨᡳᠶᠠᠮᠨᡳᠶᠠᠨ, Möllendorff: niyamniyan, Abkai: niyamniyan) are significant to the Manchus. They were well-trained horsemen from their teenage[186] years. Huangtaiji said, "Riding and archery are the most important martial arts of our country".[162]: 46 [78]: 446 Every generation of the Qing dynasty treasured riding and archery the most.[187]: 108 Every spring and fall, from ordinary Manchus to aristocrats, all had to take riding and archery tests. Their test results could even affect their rank in the nobility.[187]: 93 The Manchus of the early Qing dynasty had excellent shooting skills and their arrows were reputed to be capable of penetrating two persons.[187]: 94

From the middle period of the Qing dynasty, archery became more a form of entertainment in the form of games such as hunting swans, shooting fabric or silk target. The most difficult is shooting a candle hanging in the air at night.[187]: 95 Gambling was banned in the Qing dynasty but there was no limitation on Manchus engaging in archery contests. It was common to see Manchus putting signs in front of their houses to invite challenges.[187]: 95 After the Qianlong period, Manchus gradually neglected the practices of riding and archery, even though their rulers tried their best to encourage Manchus to continue their riding and archery traditions,[187]: 94 but the traditions are still kept among some Manchus even nowadays.[188]

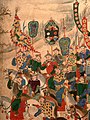

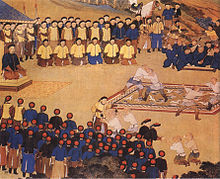

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

-

Manchu Hunting party

Manchu wrestling

[edit]