Algeria: Difference between revisions

→Culture: Cititation needed |

→Arrival of Islam: Unsourced |

||

| Line 128: | Line 128: | ||

=== Arrival of Islam === |

=== Arrival of Islam === |

||

[[File:Grande mosquée d'Alger.jpg|thumb|left|upright|[[Great Mosque of Algiers]]]] |

[[File:Grande mosquée d'Alger.jpg|thumb|left|upright|[[Great Mosque of Algiers]]]] |

||

When Muslim [[Arabs]] arrived in Algeria in the mid-7th century, a large number of locals converted to the new faith. After the fall of the [[Umayyad]] Arab Dynasty in 751, numerous local Berber dynasties emerged. Amongst those dynasties were the [[Aghlabids]], [[Almohads]], [[Abdalwadid]], [[Zirids]], [[Rustamids]], [[Hammadids]], [[Almoravids]] and the [[Fatimids]].{{citation needed|date=December 2011}} converted the Berber [[Kutama]] of the [[Lesser Kabylia]] to its cause, the [[Shia Islam|Shia]] [[Fatimid]]s overthrew the [[Rustamid]]s, and conquered Egypt, leaving Algeria and Tunisia to their [[Zirid dynasty|Zirid vassals]]. When the latter rebelled, the Shia Fatimids sent in the [[Banu Hilal]] and [[Banu Sulaym]] Arabian tribes who unexpectedly defeated the [[Zirid]]s.{{citation needed|date=December 2011}} |

|||

The Berber people controlled much of the [[Maghreb]] region throughout the Middle Ages. The Berbers were made up of several tribes. The two main branches were the Botr and Barnès tribes, who were themselves divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, [[Sanhadja]], Houaras, [[Zenata]], [[Masmuda|Masmouda]], Kutama, Awarba, and [[Berghwata]]). All these tribes were independent and made territorial decisions.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=H3RBAAAAIAAJ&pg=PR2|title=Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane| trans_title =History of the Berbers and the Muslim dynasties of northern Africa | language= French |page=XV |accessdate=28 February 2009|author1=Khaldūn, Ibn|year=1852}}</ref> |

The Berber people controlled much of the [[Maghreb]] region throughout the Middle Ages. The Berbers were made up of several tribes. The two main branches were the Botr and Barnès tribes, who were themselves divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, [[Sanhadja]], Houaras, [[Zenata]], [[Masmuda|Masmouda]], Kutama, Awarba, and [[Berghwata]]). All these tribes were independent and made territorial decisions.<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/?id=H3RBAAAAIAAJ&pg=PR2|title=Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane| trans_title =History of the Berbers and the Muslim dynasties of northern Africa | language= French |page=XV |accessdate=28 February 2009|author1=Khaldūn, Ibn|year=1852}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 12:32, 18 July 2012

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية al-Jumhūriyyah al-Jazāʾiriyyah ad-Dīmuqrāṭiyyah ash-Shaʿbiyyah | |

|---|---|

Emblem

| |

| Motto: بالشّعب وللشّعب (Arabic) "S weɣref i weɣref" (Berber) "By the people and for the people"[1][2] | |

| Anthem: "Kassaman" "We Pledge" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Algiers |

| Official languages | Arabic[3] |

| National languages | Berber |

| Ethnic groups | Arab-Berber 99% European less than 1% |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian |

| Government | Semi-presidential republic |

| Abdelaziz Bouteflika | |

| Ahmed Ouyahia | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Council of the Nation | |

| People's National Assembly | |

| Independence from France | |

• Recognized | 3 July 1962 |

• Declared | 5 July 1962 |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,381,741 km2 (919,595 sq mi) (10th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2012 estimate | 37,100,000[4] |

• 1998 census | 29,100,867 |

• Density | 14.6/km2 (37.8/sq mi) (204th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $263.661 billion[5] (47th) |

• Per capita | $7,333[5] (100th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate |

• Total | $190.709 billion[5] (49th) |

• Per capita | $5,304[5] (93rd) |

| Gini (1995) | 35.3[6] Error: Invalid Gini value |

| HDI (2011) | Error: Invalid HDI value (96th) |

| Currency | Algerian dinar (DZD) |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+01) |

| Driving side | right[8] |

| Calling code | 213 |

| ISO 3166 code | DZ |

| Internet TLD | .dz, الجزائر. |

Modern Standard Arabic is the official language.[9] Berber is spoken by one fourth of the population and has been recognized as a "national language" by the constitutional amendment since 8 May 2002.[10] Algerian Arabic (or Darja) is the language used by the majority of the population. Although French has no official status, Algeria is the second Francophone country in the world in terms of speakers[11] and French is still widely used in the government, the culture, the media (newspapers) and the education system (since primary school), due to Algeria's colonial history and can be regarded as the de facto co-official language of Algeria. The Kabyle language, the most-spoken Berber language in the country, is taught and is partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylia. | |

Algeria /ælˈdʒɪəriə/ (Arabic: الجزائر, al-Jazā'ir; Berber languages: ⴷⵣⴰⵢⴻⵔ Dzayer), officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria (الجمهورية الجزائرية الديمقراطية الشعبية, al-Jumhūriyyah al-Jazāʾiriyyah ad-Dīmuqrāṭiyyah ash-Shaʿbiyyah),[note 1] also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria,[12] is a country in the Maghreb region of Africa, with Algiers as its capital and most populous city.

With a total area of 2,381,741 square kilometres (919,595 sq mi), Algeria is the tenth-largest country in the world and the largest in Africa.[13] The country is bordered in the northeast by Tunisia, in the east by Libya, in the west by Morocco, in the southwest by Western Sahara, Mauritania, and Mali, in the southeast by Niger, and in the north by the Mediterranean Sea. As of 2012, Algeria has an estimated population of 37.1 million.[4] Algeria is a member of the African Union, the Arab League, OPEC and the United Nations, and is a founding member of the Arab Maghreb Union.

Etymology

The country's name is derived from the city of Algiers. The most common etymology links the city name to al-Jazā'ir (الجزائر, "The Islands"), a truncated form of the city's older name Jazā'ir Banī Mazghanna (جزائر بني مزغنة, "Islands of the Mazghanna Tribe"),[14][15] employed by medieval geographers such as al-Idrisi. Others [who?] trace it to Ldzayer, the Maghrebi Arabic and Berber for "Algeria" possibly related to the Zirid Dynasty King Ziri ibn-Manad and founder of the city of Algiers.[16]

History

Algeria has been populated since 10,000 BC, as depicted in the Tassili National Park. The indigenous peoples of northern Africa are a distinct native population, called the Berbers[17] by Greeks and Romans, and then by Arabs.

Prehistoric period

The cave painting found around the Tassili n'Ajjer in northern Tamanrasset, and in other places, depicts scenes from every day life in the prehistoric Algeria, between 8000 and 4000 BC. They were executed by hunters during the Capsian period of the Neolithic age who lived in a savanna region, known then as the Green Sahara. Those paintings show giant buffalos, elephants, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus, animals that no longer exist in the now-desert area. The pictures provide the most complete record of a prehistoric Algerian history.

Earlier inhabitants of Algeria also left a significant amount of remains. At Ain Hanech[19] region (Saïda Province), early remnants (200,000 BC) of hominid occupation in North Africa were found. Neanderthal tool makers produced hand axes in the Levalloisian and Mousterian styles (43,000 BC) similar to those in the Levant.

According to some sources, Algeria was the site of the highest state of development of Middle Paleolithic Flake tool techniques. Tools of this era, starting about 30,000 BC, are called Aterian (after the archeological site of Bir el Ater, south of Annaba) and are marked by a high standard of workmanship, great variety, and specialization.

The earliest blade industries in North Africa are called Iberomaurusian (located mainly in Oran region). This industry appears to have spread throughout the coastal regions of the Maghreb between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. Neolithic civilization (animal domestication and agriculture) developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghrib between 6000 and 2000 BC. This life richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer paintings, predominated Algeria until the classical period.

The amalgam of peoples of North Africa coalesced eventually into a distinct native population that came to be called Berbers. Distinguished by cultural and linguistic attributes, the Berbers were typically depicted as "barbaric" enemies, troublesome nomads, or ignorant peasants by Roman, Greek, Byzantine, and Arab Muslim invaders. They were, however, to play a major role in the area's history.

Classical period

From their principal center of power at Carthage, the Carthaginians expanded and established small settlements along the North African coast; by 600 BC, a Phoenician presence existed at Tipasa, east of Cherchell, Hippo Regius (modern Annaba) and Rusicade (modern Skikda). These settlements served as market towns as well as anchorages.

As Carthaginian power grew, its impact on the indigenous population increased dramatically. Berber civilization was already at a stage in which agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and political organization supported several states. Trade links between Carthage and the Berbers in the interior grew, but territorial expansion also resulted in the enslavement or military recruitment of some Berbers and in the extraction of tribute from others.

By the early fourth century BC, Berbers formed the single largest element of the Carthaginian army. In the Revolt of the Mercenaries, Berber soldiers rebelled from 241 to 238 BC after being unpaid following the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War. They succeeded in obtaining control of much of Carthage's North African territory, and they minted coins bearing the name Libyan, used in Greek to describe natives of North Africa. The Carthaginian state declined because of successive defeats by the Romans in the Punic Wars.

In 146 BC the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew. By the second century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. Two of them were established in Numidia, behind the coastal areas controlled by Carthage. West of Numidia lay Mauretania, which extended across the Moulouya River in modern day Morocco to the Atlantic Ocean. The high point of Berber civilization, unequaled until the coming of the Almohads and Almoravids more than a millennium later, was reached during the reign of Massinissa in the second century BC.

After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, the Berber kingdoms were divided and reunited several times. Massinissa's line survived until 24 AD, when the remaining Berber territory was annexed to the Roman Empire for 2 centuries.

Arrival of Islam

The Berber people controlled much of the Maghreb region throughout the Middle Ages. The Berbers were made up of several tribes. The two main branches were the Botr and Barnès tribes, who were themselves divided into tribes, and again into sub-tribes. Each region of the Maghreb contained several tribes (for example, Sanhadja, Houaras, Zenata, Masmouda, Kutama, Awarba, and Berghwata). All these tribes were independent and made territorial decisions.[20]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages in Maghreb, Sudan, Andalusia, Italy, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Egypt, and other nearby lands. Ibn Khaldun provides a table summarizing the Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad, Merinid, Abdalwadid, Wattasid, Meknassa and Hafsid dynasties.[21]

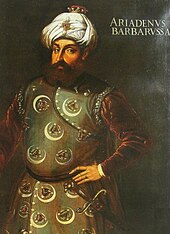

Barbary corsairs

The Spanish expansionist policy in North Africa began with the rule of the Catholic monarchs Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon and their regent Cisneros. Once the Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula was completed, several towns and outposts on the Algerian coast were conquered and occupied by the Spanish Empire: Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Peñón of Algiers (1510) and Bugia (1510). The Muslim leaders of Algiers called for help from the Barbary corsairs Hayreddin Barbarossa and Oruç Reis, who previously helped Andalusian Muslims and Jews escape from Spanish oppression in 1492. In 1516, Oruç Reis conquered Algiers with the support of 1,300 Turkish soldiers on board 16 galliots and became its ruler, with Algiers joining the Ottoman Empire.

The Spaniards left Algiers in 1529, Bugia in 1554, Mers El Kébir and Oran in 1708. The Spanish returned in 1732 when the armada of the Duke of Montemar was victorious in the Battle of Aïn-el-Turk; Spain recaptured Oran and Mers El Kébir. Both cities were held until 1792, when they were sold by King Charles IV of Spain to the Bey of Algiers.

Algeria was made part of the Ottoman Empire by Hayreddin Barbarossa and his brother Aruj in 1517. After the death of Oruç Reis in 1518, his brother succeeded him. The Sultan Selim I sent him 6,000 soldiers and 2,000 janissaries with which he conquered most of the Algerian territory taken by the Spanish, from Annaba to Mostaganem. Further Spanish attacks led by Hugo of Moncada in 1519 were also pushed back. In 1541, Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, attacked Algiers with a convoy of 65 warships, 451 large ships and 23,000 men, 2000 of whom were mounted. The attack resulted in failure however, and the Algerian leader Hassan Agha became a national hero as Algiers grew into a center of military power in the Mediterranean.[citation needed]

The Ottomans established Algeria's modern boundaries in the north and made its coast a base for the Ottoman corsairs; their privateering peaked in Algiers in the 17th century. Piracy on American vessels in the Mediterranean resulted in the First (1801–1805) and Second Barbary Wars (1815) with the United States. The pirates forced the people on the ships they captured into slavery; when the pirates attacked coastal villages in southern and Western Europe the inhabitants were forced into the Arab slave trade.[22]

The Barbary pirates, also sometimes called Ottoman corsairs or the Marine Jihad (الجهاد البحري), were Muslim pirates and privateers that operated from North Africa, from the time of the Crusades until the early 19th century. Based in North African ports such as Tunis in Tunisia, Tripoli in Libya and Algiers in Algeria, they preyed on Christian and other non-Islamic shipping in the western Mediterranean Sea.[23]

Their stronghold was along the stretch of northern Africa known as the Barbary Coast (a medieval term for the Maghreb after its Berber inhabitants), but their predation was said to extend throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard, and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland and the United States. They often made raids, called Razzias, on European coastal towns to capture Christian slaves to sell at slave markets in places such as Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Algeria and Morocco.[24][25] According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th century, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves. These slaves were captured mainly from seaside villages in Italy, Spain and Portugal, and from farther places like France, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Russia, Scandinavia and even Iceland, India, Southeast Asia and North America.[citation needed]

In 1544, Hayreddin captured the island of Ischia, taking 4,000 prisoners, and enslaved some 9,000 inhabitants of Lipari, almost the entire population.[26] In 1551, Turgut Reis enslaved the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo, between 5,000 and 6,000, sending them to Libya. In 1554, pirates sacked Vieste in southern Italy and took an estimated 7,000 slaves.[27]

In 1558, Barbary corsairs captured the town of Ciutadella (Minorca), destroyed it, slaughtered the inhabitants and took 3,000 survivors to Istanbul as slaves.[28] In 1563, Turgut Reis landed on the shores of the province of Granada, Spain, and captured coastal settlements in the area, such as Almuñécar, along with 4,000 prisoners. Barbary pirates often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response many coastal watchtowers and fortified churches were erected. The threat was so severe that the island of Formentera became uninhabited.[29]

Between 1609 to 1616, England lost 466 merchant ships to Barbary pirates.[30] In the 19th century, Barbary pirates would capture ships and enslave the crew. Later American ships were attacked. During this period, the pirates forged affiliations with Caribbean powers, paying a "license tax" in exchange for safe harbor of their vessels.[31] One American slave reported that the Algerians had enslaved 130 American seamen in the Mediterranean and Atlantic from 1785 to 1793.[32]

Plague had repeatedly struck the cities of North Africa. Algiers lost from 30,000 to 50,000 inhabitants to the plague in 1620–21, and again in 1654–57, 1665, 1691, and 1740–42.[23]

Relations with the US

US ships paid the tribute demanded by the rulers of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli and Morocco, preventing attacks on their shipping by Mediterranean corsairs, no longer covered by Great Britain after independence. In 1794 US Congress voted for funds appropriation for warship construction, to counter Mediterranean threats. Despite this the US signed a treaty of $10M (20% of the US annual revenue in 1800) with Algerian Dey to ensure 12 years of attack free shipping in the Mediterranean sea.

After the Napoleonic wars Algeria found itself at war with Spain, Netherlands, England, Prussia, Denmark, Russia and Naples. In March of this year the US government authorized war against the Barbary States, giving place to what is known as Barbary wars. The next year after those wars Algeria was weaker, Europeans with an Anglo-Dutch fleet commanded by the British Lord Exmouth attacked Algiers. After a nine hours bombardment, they obtained a treaty from the Dey that reaffirmed the conditions imposed by Decatur (US navy) concerning the demands of tributes. In addition the Dey agreed to end the practice of enslaving Christians.[33]

French rule

On the pretext of a slight to their consul, the French invaded and captured Algiers in 1830.[34][35] The conquest of Algeria by the French was long and resulted in considerable bloodshed. A combination of violence and disease epidemics caused the indigenous Algerian population to decline by nearly one-third from 1830 to 1872.[36]

Between 1825 and 1847, 50,000 French people emigrated to Algeria.[37] These settlers benefited from the French government's confiscation of communal land and the application of modern agricultural techniques that increased the amount of arable land.[38] Algeria's social fabric suffered during the occupation: literacy plummeted,[39]

After Algeria's 1962 independence, the Europeans were called Pieds-Noirs ("black feet"). Some apocryphal sources suggest the title comes from the black boots settlers wore, but the term seems not to have been widely used until the time of the Algerian War of Independence and it is more likely it started as an insult towards settlers returning from Africa.[40]

Post-independence

In 1954, the National Liberation Front (Front de Libération Nationale or FLN) launched the Algerian War of Independence which was a guerrilla campaign. By the end of the war, French President Charles de Gaulle held a plebiscite, offering Algerians three options. In a famous speech (4 June 1958 in Algiers), de Gaulle proclaimed in front of a vast crowd of Pieds-Noirs "Je vous ai compris" ("I have understood you"). Most Pieds-Noirs then believed that de Gaulle meant that Algeria would remain French. The poll resulted in a landslide vote for complete independence from France. Over one million people, ten percent of the population, fled the country for France in just a few months in mid-1962. These included most of the 1,025,000 Pieds-Noirs, as well as 81,000 Harkis (pro-French Algerians serving in the French Army). In the days preceding the bloody conflict, a group of Algerian Rebels opened fire on a marketplace in Oran, killing numerous civilians, mostly women. It is estimated that somewhere between 50,000 and 150,000 Harkis and their dependents were killed by the FLN or by lynch mobs in Algeria.[41]

Algeria's first president was the FLN leader Ahmed Ben Bella. He was overthrown by his former ally and defense minister, Houari Boumédienne in 1965. Under Ben Bella, the government had already become increasingly socialist and authoritarian, and this trend continued throughout Boumédienne's government. However, Boumédienne relied much more heavily on the army, and reduced the sole legal party to a merely symbolic role. Agriculture was collectivised, and a massive industrialization drive launched. Oil extraction facilities were nationalized. This was especially beneficial to the leadership after the 1973 oil crisis. However, the Algerian economy became increasingly dependent on oil which led to hardship when the price collapsed during the 1980s oil glut.[42]

Boumediene Era

Boumediene putsch over Ben Bella on 19 March 1965 was described, by the Algerian authorities, as a "historical rectification" of the Algerian Revolution. Boumediene dissolved the National Assembly, suspended the 1963 Constitution, disbanded the militia, and abolished the political bureau, a Ben Bella legacy considered his instrument of rule.

After 1965 Algeria was governed by the 26 members of the Revolutionary Council, led by Boumediene. Boumediene was an ardent patriot, deeply influenced by Islamic values. The 'agricultural revolution', the main policy initiative of the Boumediene era, commenced in 1971, but did not have the desired impact. It consisted mainly in the seizure of proprieties and the redistribution of said properties to cooperative farms. During the Boumediene era, a third Algerian Constitution was inaugurated in 1976.

Boumediene was criticised among FLN radical members for betraying "rigorous socialism". Some of the military attempted a coup d'état in 1967. Boumediene also survived an assassination attempt in 1968, after which opponents were exiled or imprisoned, and Boumediene's power consolidated.

Arabization policy

Of all current Arab countries subject to European colonization, Algeria absorbed the heaviest colonial impact. The French controlled almost all the education and cultural life of the colonial system, for over 132 years. Consequently, it emerged as the bi-linguistic state of Algeria after 1962.[43]

French policy was oriented towards "civilizing" the country, even with a literacy rate of 50 percent in 1830 (more than in France itself [44]), a lot of Algerian Arabic books of the early 19th century are currently present in the National Library of Algeria. The French language replaced the Arabic and Berber languages in almost everything and Arabic declined drastically. Dialectic Arabic, used for every day communications, (Algerian Arabic) survived, but was also influenced by the French language.

During this period a small but influential French-speaking indigenous elite was formed, made up of Berbers mostly from Kabyles. In their policy of "divide to reign," Kabyles were favored by this colonial system.[45] In fact 80 percent of Indigenous Schools were destined for Kabyles. As a result, Kabyles moved into large levels of state administration across Algeria after 1962, who, among all Algerians, were the most attached to the French culture.

The Nationalists who ruled Algeria after independence committed themselves to the hard task of regenerating indigenous language and cultural background, in order to recover the precolonial past and to use it in order to restore (if not to create) a national identity based on Islam, Arabic Language, and Algerianism.

This movement was transformed into a state policy called "arabization." Many problems occurred in the application of this new policy. Arabic teachers were lacking, and Algerians were not used to the Literary Arabic. More problems came out during the 1980s Berber Spring, in which Kabyles asked for a solution to the Berber question. They believed Arabization was a menace to the Berber Culture and heritage, and that the French Language offered more opportunities.

The Arabization Movement

Under Boumediene, arabization took the form of a national language requirement on street signs and shop signs. Algeria remains caught between strident demands to eliminate any legacy from its colonial past and the more pragmatic concerns of the costs of rapid arabization. Calls have been made to eliminate coeducational schooling and affect the arabization of medical and technological schools.

The Arabization of Algerian society would expedite the inevitable break with France. Tahir Wattar, a prominent pro-arabization Berber, called French use and teaching the "Vestige of Colonialism". In December 1990, a law was passed that would implement complete arabization of secondary school and higher education by 1997. In early July 1993, the most recent legislation proposing a national timetable for imposing Arabic as the only legal language in government and politics was again delayed; this was a result of official concerns about the existence of the necessary preconditions for sensible arabization. The law was to require that Arabic be the language of official communication, and would impose substantial fines for law violations.

Because many of the Algerian elite had been taught French under colonialism, and because a significant sector of the population spoke Tamazight, arabization has not always been popular.[46]

Political events (1991–2002)

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

More than 160,000 people were killed between 17 January 1992 and June 2002 in various terrorist attacks which were claimed by the Armed Islamic Group and Islamic Salvation Army. However, elections resumed in 1995, and after 1998, the war waned. On 27 April 1999, after a series of short-term leaders representing the military, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the current president, was chosen by the army.[47]

Post war

By 2002, the main guerrilla groups had either been destroyed or surrendered, taking advantage of an amnesty program, though fighting and terrorism continues in some areas (See Islamic insurgency in Algeria (2002–present)).[citation needed]

The issue of Amazigh languages and identity increased in significance as of 1998, when the United Nations declared that the Berbers are the indigenous people of North Africa, and giving them rights to their language, culture and historical facts. In Algeria after the extensive protests of 2001 and the near-total boycott of local elections in Kabylie Protests in Arris and T'kout Aures in 2004, where over 200 were jailed. The government responded with concessions including naming of Tamazight (Berber) as a national language and teaching it in schools.

Popular protests since 2010

Following a wave of protests in the wake of popular uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, Algeria officially lifted its 19-year-old state of emergency on 24 February 2011. The country's Council of Ministers approved the repeal two days prior.[48]

Geography

Algeria is the largest country in Africa, the Arab world, and the Mediterranean Basin. Its southern part includes a significant portion of the Sahara. To the north, the Tell Atlas form with the Saharan Atlas, further south, two parallel sets of reliefs in approaching eastbound, and between which are inserted vast plains and highlands. Both Atlas tend to merge in eastern Algeria. The vast mountain ranges of Aures and Nememcha, occupy the entire north eastern Algeria and are delineated by the Tunisian border. The highest point is Mount Tahat (3,003 m).

Algeria lies mostly between latitudes 19° and 37°N (a small area is north of 37°), and longitudes 9°W and 12°E. Most of the coastal area is hilly, sometimes even mountainous, and there are a few natural harbours. The area from the coast to the Tell Atlas is fertile. South of the Tell Atlas is a steppe landscape, which ends with the Saharan Atlas; further south, there is the Sahara desert.[citation needed]

The Ahaggar Mountains (Arabic: جبال هقار), also known as the Hoggar, are a highland region in central Sahara, southern Algeria. They are located about 1,500 km (932 mi) south of the capital, Algiers and just west of Tamanghasset. Algiers, Oran, Constantine, Tizi Ouzou and Annaba are Algeria's main cities.[citation needed]

Algeria is the biggest country in Africa, followed by Democratic Republic of Congo. More than ninety percent of its surface is covered by the Sahara desert.[citation needed]

Climate and hydrology

In this region, midday desert temperatures can be hot year round. After sunset, however, the clear, dry air permits rapid loss of heat, and the nights are cool to chilly. Enormous daily ranges in temperature are recorded.

The highest official temperature was 50.6 °C (123.1 °F) at In Salah.[49]

Rainfall is fairly abundant along the coastal part of the Tell Atlas, ranging from 400 to 670 mm (15.7 to 26.4 in) annually, the amount of precipitation increasing from west to east. Precipitation is heaviest in the northern part of eastern Algeria, where it reaches as much as 1,000 mm (39.4 in) in some years.

Politics

Algeria is an authoritarian regime, according to the Democracy Index 2010.[50] The Freedom of the Press 2009 report gives it rating "Not Free".[51]

The head of state is the president of Algeria, who is elected for a five-year term. The president was formerly limited to two five-year terms but a constitutional amendment passed by the Parliament on 11 November 2008 removed this limitation.[52] Algeria has universal suffrage at 18 years of age.[53] The President is the head of the army, the Council of Ministers the High Security Council. He appoints the Prime Minister who is also the head of government.[54]

The Algerian parliament is bicameral, consisting of a lower chamber, the National People's Assembly (APN), with 380 members; and an upper chamber, the Council Of Nation, with 144 members. The APN is elected every five years.[55]

Under the 1976 constitution (as modified 1979, and amended in 1988, 1989, and 1996), Algeria is a multi-party state. The Ministry of the Interior must approve all parties. To date, Algeria has had more than 40 legal political parties. According to the constitution, no political association may be formed if it is "based on differences in religion, language, race, gender, profession or region". In addition, political campaigns must be exempt from the aforementioned subjects.[56]

Foreign relations and military

The military of Algeria consists of the People's National Army (ANP), the Algerian National Navy (MRA), and the Algerian Air Force (QJJ), plus the Territorial Air Defense Force.[53] It is the direct successor of the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN), the armed wing of the nationalist National Liberation Front, which fought French colonial occupation during the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62). The commander-in-chief of the military is the president, who is also Minister of National Defense.[citation needed]

Total military personnel include 147,000 active, 150,000 reserve, and 187,000 paramilitary staff (2008 estimate).[57] Service in the military is compulsory for men aged 19–30, for a total of 18 months (six training and 12 in civil projects).[53] The total military expenditure in 2006 was estimated variously at 2.7% of GDP (3,096 million),[57] or 3.3% of GDP.[53]

The Algerian Air Force signed a deal with Russia in 2007, to purchase 49 MiG-29SMT and 6 MiG-29UBT at an estimated $1.9 billion. They also agreed to return old aircraft purchased from the former USSR. Russia is also building two 636-type diesel submarines for Algeria.[58]

In October 2009, Algeria cancelled a weapons deal with France over the possibility of inclusion of Israeli parts in them.[59]

Tensions between Algeria and Morocco in relation to the Western Sahara have been an obstacle to tightening the Arab Maghreb Union, which was nominally established in 1989 but which has carried little practical weight.[60]

Provinces and districts

The administrative divisions have changed several times since independence. When introducing new provinces, the numbers of old provinces are kept, hence the non-alphabetical order. With their official numbers, currently (since 1983) they are:[53]

| # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population | map | # | Wilaya | Area (km2) | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adrar | 402,197 | 439,700 |  |

30 | Ouargla | 211,980 | 552,539 |

| 2 | Chlef | 4,975 | 1,013,718 | 31 | Oran | 2,114 | 1,584,607 | |

| 3 | Laghouat | 25,057 | 477,328 | 32 | El Bayadh | 78,870 | 262,187 | |

| 4 | Oum El Bouaghi | 6,768 | 644,364 | 33 | Illizi | 285,000 | 54,490 | |

| 5 | Batna | 12,192 | 1,128,030 | 34 | Bordj Bou Arréridj | 4,115 | 634,396 | |

| 6 | Béjaïa | 3,268 | 915,835 | 35 | Boumerdes | 1,591 | 795,019 | |

| 7 | Biskra | 20,986 | 730,262 | 36 | El Taref | 3,339 | 411,783 | |

| 8 | Béchar | 161,400 | 274,866 | 37 | Tindouf | 58,193 | 159,000 | |

| 9 | Blida | 1,696 | 1,009,892 | 38 | Tissemsilt | 3,152 | 296,366 | |

| 10 | Bouïra | 4,439 | 694,750 | 39 | El Oued | 54,573 | 673,934 | |

| 11 | Tamanrasset | 556,200 | 198,691 | 40 | Khenchela | 9,811 | 384,268 | |

| 12 | Tébessa | 14,227 | 657,227 | 41 | Souk Ahras | 4,541 | 440,299 | |

| 13 | Tlemcen | 9,061 | 945,525 | 42 | Tipaza | 2,166 | 617,661 | |

| 14 | Tiaret | 20,673 | 842,060 | 43 | Mila | 9,375 | 768,419 | |

| 15 | Tizi Ouzou | 3,568 | 1,119,646 | 44 | Ain Defla | 4,897 | 771,890 | |

| 16 | Algiers | 273 | 2,947,461 | 45 | Naâma | 29,950 | 209,470 | |

| 17 | Djelfa | 66,415 | 1,223,223 | 46 | Ain Timouchent | 2,376 | 384,565 | |

| 18 | Jijel | 2,577 | 634,412 | 47 | Ghardaia | 86,105 | 375,988 | |

| 19 | Sétif | 6,504 | 1,496,150 | 48 | Relizane | 4,870 | 733,060 | |

| 20 | Saïda | 6,764 | 328,685 | 49 | El M'Ghair | 8,835 | 162,267 | |

| 21 | Skikda | 4,026 | 904,195 | 50 | El Menia | 62,215 | 57,276 | |

| 22 | Sidi Bel Abbès | 9,150 | 603,369 | 51 | Ouled Djellal | 11,410 | 174,219 | |

| 23 | Annaba | 1,439 | 640,050 | 52 | Bordj Baji Mokhtar | 120,026 | 16,437 | |

| 24 | Guelma | 4,101 | 482,261 | 53 | Béni Abbès | 101,350 | 50,163 | |

| 25 | Constantine | 2,187 | 943,112 | 54 | Timimoun | 65,203 | 122,019 | |

| 26 | Médéa | 8,866 | 830,943 | 55 | Touggourt | 17,428 | 247,221 | |

| 27 | Mostaganem | 2,269 | 746,947 | 56 | Djanet | 86,185 | 17,618 | |

| 28 | M'Sila | 18,718 | 991,846 | 57 | In Salah | 131,220 | 50,392 | |

| 29 | Mascara | 5,941 | 780,959 | 58 | In Guezzam | 88,126 | 11,202 |

Economy

The fossil fuels energy sector is the backbone of Algeria's economy, accounting for roughly 60 percent of budget revenues, 30 percent of GDP, and over 95 percent of export earnings. The country ranks 14th[when?] in petroleum reserves, containing 11.8 billion barrels (1.88×109 m3) of proven oil reserves with estimates suggesting that the actual amount is even more. The U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that in 2005, Algeria had 160 trillion cubic feet (4.5×1012 m3) of proven natural-gas reserves,[61] the tenth largest in the world.[62] Average annual non-hydrocarbon GDP growth averaged 6 percent between 2003 and 2007, with total GDP growing at an average of 4.5 percent during the same period due to less-buoyant oil production during 2006 and 2007. External debt has been virtually eliminated, and the government has accumulated large savings in the oil-stabilization fund (FRR). Inflation, the lowest in the region, has remained stable at four percent on average between 2003 and 2007.[63]

Algeria's financial and economic indicators improved during the mid-1990s, in part because of policy reforms supported by the International Monetary Fund and debt rescheduling from the Paris Club.[citation needed] Algeria's finances in 2000 and 2001 benefited from an increase in oil prices and the government's tight fiscal policy, leading to a large increase in the trade surplus, record highs in foreign exchange reserves, and reduction in foreign debt.[citation needed]

The government's continued efforts to diversify the economy by attracting foreign and domestic investment outside the energy sector have had little success in reducing high unemployment and improving living standards, however. In 2001, the government signed an Association Treaty with the European Union that will eventually lower tariffs and increase trade. In March 2006, Russia agreed to erase $4.74 billion of Algeria's Soviet-era debt[64] during a visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin to the country, the first by a Russian leader in half a century. In return, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika agreed to buy $7.5 billion worth of combat planes, air-defense systems and other arms from Russia, according to the head of Russia's state arms exporter Rosoboronexport.[65][66]

In 2011 Algeria announced a budgetary surplus of $26.93 billion, 62.46 percent increase in comparison to 2010 surplus. In general, the country exported $73.39 billion worth of commodities while it imported $46.45 billion.[67]

Agriculture

Algeria has always been noted for the fertility of its soil. 14 percent of its labor force are employed in the agricultural sector.[53]

More than 30,000 km2 (7,000,000 acres) are devoted to the cultivation of cereal grains. The Tell Atlas is the grain-growing land. During the time of French rule its productivity was increased substantially by the sinking of artesian wells in districts which only required water to make them fertile. Of the crops raised, wheat, barley and oats are the principal cereals. A great variety of vegetables and fruits, especially citrus products, are exported. Algeria also exports figs, dates, esparto grass, and cork.

Demographics

As of a January 2010 estimate, Algeria's population was 34.9 million, who are mainly Arab-Berber ethnically.[53][68] At the outset of the 20th century, its population was approximately four million.[69] About 90 percent of Algerians live in the northern, coastal area; the inhabitants of the Sahara desert are mainly concentrated in oases, although some 1.5 million remain nomadic or partly nomadic. More than 25 percent of Algerians are under the age of 15.[53]

The Berbers are the indigenous ethnic group of Algeria and are believed to be the ancestral stock on which elements from the Phoenicians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Turks as well as other ethnic groups have contributed to the ethnic makeup of Algeria.[70] Furthermore, the country has a diverse population ranging from light-skinned, gray-eyed Chaoui and blue-eyed Kabyles in the Atlas Mountains to very dark-skinned populations in the Sahara (e.g., the Tuaregs). Descendants of Andalusian refugees are also present in the population of Algiers and other cities.[71]

Linguistically, approximately 73 percent of Algerians speak Algerian Arabic, while approximately 27 percent speak one of the Berber languages [citation needed] mainly found in the Kabyle and Chaoui regions. French is widely understood, and Standard Arabic (Foshaa) is taught to and understood by most Algerian-Arabic-speaking youth.

Europeans account for less than 1% of the population, inhabiting almost exclusively the largest metropolitan areas. However, during the colonial period there was a large (15.2 percent in 1962) European population, consisting primarily of French people, in addition to Spaniards in the west of the country, Italians and Maltese in the east, and other Europeans such as Greeks in smaller numbers. Known as Pieds-Noirs, European colonists were concentrated on the coast and formed a majority of the population of Oran (60 percent) and important proportions in other large cities including Algiers and Annaba. Almost all of this population left during or immediately after the country's independence from France.[72] Housing and medicine shortages continue to be pressing problems in Algeria. Failing infrastructure and the continued influx of people from rural to urban areas has overtaxed both systems. According to the United Nations Development Programme, the country has one of the world's-highest per-housing-unit occupancy rates for housing, and government officials have publicly stated that the country has an immediate shortfall of 1.5 million housing units.[citation needed] Women make up 70 percent of the country's lawyers and 60 percent of its judges, and also dominate the field of medicine. Increasingly, women are contributing more to household income than men. Sixty percent of university students are women, according to university researchers.[73]

It is estimated that 95,700 refugees and asylum-seekers have sought refuge in Algeria. This includes roughly 90,000 from Morocco and 4,100 from Palestine.[74] An estimated 46,000[75] Sahrawis from Western Sahara live in refugee camps in the Algerian part of the Sahara desert.[76][77] As of 2009[update], 35,000 Chinese migrant workers lived in Algeria.[78]

Ethnic groups

Almost all Algerians are Berbers in origins, not Arabs[53][68][79][80][81][82] the Semitic ethnic presence in the country is mainly due to the Phoenicians and Hilallians migratory movements (3rd century BC and 11th century, respectively). The majority of Arabized Berber claim an Arab heritage due to Arab nationalism. The Berbers are divided into many groups with varying languages. The largest of these are the Kabyles, who live in the Kabylia Mountains east of Algiers, the Chaoui of North-East Algeria, and the Tuaregs in the southern desert and the Shenwa people of North Algeria.[83] Another historical migratory movements that made the actual Algerians was the Vandalic invasion of the 5th century,[84] and the Mediterranean trade of the 16th–19th century.

There is also a minority of about 600,000 to 2 million Algerian Turks who arrived in the region during the Ottoman rule in North Africa;[85] today's Turkish descendants are often called "Kouloughlis" which means the descendants of Turkish men and of native Algerian women.[86][87]

Languages

The official language of Algeria is Modern Standard Arabic, as specified in its constitution since 1963. In addition to this, Berber has been recognized as a "national language" by constitutional amendment since 8 May 2002. Between them, these two languages are the native languages of over 99 percent of Algerians, with colloquial Algerian Arabic spoken by about 72 percent and Berber by 27 percent .[88] French, though it has no official status, is widely used in government, culture, media (newspapers) and education (taught from primary school), due to Algeria's colonial history and can be regarded as being the de facto co-official language of Algeria. The Kabyle language, the most-spoken Berber language in the country, is taught and partially co-official (with a few restrictions) in parts of Kabylia. Algerian cities have commonly been given Berber and ancient Roman names.[citation needed]

Religion

Islam is the predominant religion with 99 percent of the population.[53] Almost all Algerian Muslims follow Sunni Islam, with the exception of some 200,000 Ibadis in the M'zab Valley in the region of Ghardaia.[89]

There are also some 250,000 Christians in the country[dubious – discuss], including about 10,000 Roman Catholics and 150,000 to 200,000 evangelical Protestants (mainly Pentecostal), according to the Protestant Church of Algeria's leader Mustapha Krim[citation needed]. Algeria had an important Jewish community until the 1960s. Nearly all of this community emigrated following the country's independence, although a very small number of Algerian Jews continue to live in Algiers.[90]

Women in Algeria

Cities

Below is a list of the most important Algerian cities: Template:Largest cities of Algeria

Health

In 2002, Algeria had inadequate numbers of physicians (1.13 per 1,000 people), nurses (2.23 per 1,000 people), and dentists (0.31 per 1,000 people). Access to "improved water sources" was limited to 92 percent of the population in urban areas and 80 percent of the population in rural areas. Some 99 percent of Algerians living in urban areas, but only 82 percent of those living in rural areas, had access to "improved sanitation". According to the World Bank, Algeria is making progress toward its goal of "reducing by half the number of people without sustainable access to improved drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015". Given Algeria's young population, policy favors preventive health care and clinics over hospitals. In keeping with this policy, the government maintains an immunization program. However, poor sanitation and unclean water still cause tuberculosis, hepatitis, measles, typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery. The poor generally receive health care free of charge.[91]

Education

Education is officially compulsory for children between the ages of six and 15. Approximately 5% of the adult population of the country is illiterate.[92]

Culture

Modern Algerian literature, split between Arabic, Kabyle and French, has been strongly influenced by the country's recent history. Famous novelists of the 20th century include Mohammed Dib, Albert Camus, Kateb Yacine and Ahlam Mosteghanemi while Assia Djebar is widely translated. Among the important novelists of the 1980s were Rachid Mimouni, later vice-president of Amnesty International, and Tahar Djaout, murdered by an Islamist group in 1993 for his secularist views.[93] In painting, Mohammed Khadda[94]

Cinema

The birth of Algerian cinema goes back to independence in 1962, which was the main subject of different movie productions of that time. Next were films such as The Winds of the Aures (1965) of Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Patrol To The East (1972) of Amar Laskri, Prohibited Area of Ahmed Lallem, (1972), The Opium and the stick of Ahmed Rachedi, or The Battle of Algiers (1966) which is an Algerian-Italian film selected three times at the Oscars. The most famous work of Algerian cinema is probably that of Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Chronicle of the Years of Fire, which won the palme d'Or at the Cannes film festival in the year 1975. Algeria remains to this day, the only nation in Africa and the Arab world to have achieved such a distinction. Algeria had also won an Oscar for the movie Z, a political thriller directed by Costa Gavras.

Subsequently other topics would be explored in films such as Omar Guetlato of Merzak Allouache; this production, which has been a significant success, is a chronicle of the difficulties that can meet the urban youth.

In comedy, several players are emerging in the image of the very popular Rouiched which is illustrated in several films such as Hassan Terro or Hassan Taxi, or actor Hadj Abderrahmane better known under the pseudonym of the Inspector Tahar in 1973 comedy The Holiday of The Inspector Tahar directed by Musa Haddad. The most accomplished comedy is Carnaval fi dechra directed by Mohamed Oukassi, and starting Athman Ariouet.

From the mid 1980s, Algerian cinema began to go through a long period of lethargy where major productions became rare. This situation is greatly due to the gradual disengagement of the state, which makes it very difficult to subsidize film achievements. However, some productions have recorded success: Carnival fi Dachra produced by Mohamed Oukassi and Athmane Aliouet in 1994, or as "Salut Cousin !" (1996) produced by Merzak Allouache. Currently Algerian cinema is in a phase of restructuring; the French-wing is taking the lead over the Algerian one, and many film production are written in French rather than Algerian arabic. This is mainly due to the immigration wave of the 1990s.

-

Chronicle of the Years of Fire the 1974 palme d'Or winner of best film

-

The Battle of Algiers had an international success

Art

Algeria has always been a source of inspiration for different painters who tried to immortalize the prodigious diversity of the sites it offers and the profusion of the facets that passes its population, which offers for Orientalists between the 19th century and the 20th century, a striking inspiration for a very rich artistic creation like Eugène Delacroix with his famous painting women of Algiers in their apartment or Etienne Dinet or other painters of world fame like Pablo Picasso with his painting women of Algiers, or painters issued from the Algiers school.

Meanwhile Algerian painters, like Mohamed Racim or Baya, attempted to revive the prestigious Algerian past prior to French colonization, at the same time that they have contributed to the preservation of the authentic values of Algeria. In this line, Mohamed Temam, Abdelkhader Houamel have also returned through this art, scenes from the history of the country, the habits and customs of the past and the country life. Other new artistic currents including the one of M'hamed Issiakhem, Mohammed Khadda and Bachir Yelles, appeared on the scene of Algerian painting, abandoning figurative classical painting to find new pictorial ways, in order to adapt Algerian paintings to the new realities of the country through its struggle and its aspirations.

Literature

The historic roots of Algerian literature goes back to the Numidian era, when Apuleius wrote The Golden Ass, the only Latin novel to survive in its entirety. This period had also known Augustine of Hippo, Nonius Marcellus and Martianus Capella among many others. The Middle Ages have known many arabic writers who revolutionized the Arab world literature with authors like Ahmad al-Buni and Ibn Manzur and Ibn Khaldoun who wrote the Muqaddimah while staying in Algeria, and many others.

Today Algeria contains, in its literary landscape, big names having not only marked the Algerian literature, but also the universal literary heritage in Arabic and French.

As a first step, Algerian literature was marked by works whose main concern was the assertion of the Algerian national entity, there is the publication of novels as the Algerian trilogy of Mohammed Dib, or even Nedjma of Kateb Yacine novel which is often regarded as a monumental and major work. Other known writers will contribute to the emergence of Algerian literature whom include Mouloud Feraoun, Malek Bennabi, Malek Haddad, Moufdi Zakaria, Ibn Badis, Mohamed Laïd Al-Khalifa, Mouloud Mammeri, Frantz Fanon, and Assia Djebar.

In the aftermath of the independence, several new authors emerged on the Algerian literary scene, they will attempt through their works to expose a number of social problems, among them there are Rachid Boudjedra, Rachid Mimouni, Leila Sebbar, Tahar Djaout and Tahir Wattar.

Currently, a part of Algerian writers tends to be defined in a literature of shocking expression, due to the terrorism that occurred during the 1990s, the other party is defined in a different style of literature who staged an individualistic conception of the human adventure. Among the most noted recent works, there is the writer, the swallows of Kabul and the attack of Yasmina Khadra, the oath of barbarians of Boualem Sansal, memory of the flesh of Ahlam Mosteghanemi and the last novel by Assia Djebar nowhere in my father's House.

Music

Algerian music is a perfect reflection of the cultural diversity that characterizes the country, music directories are distinguished by a profusion of several styles.

Chaâbi music is a typically Algerian musical genre that was derived from the Andalusian music during the 1920s. The style is characterized by specific rhythms and of Qacidate (Popular poems) in Arabic dialect that are long poems from the Algerian heritage. The undisputed master of this music is El Hadj M'Hamed El Anka. The Constantinois Malouf style is saved by musician from whom Mohamed Tahar Fergani is one of the best performers.

Andalusian so-called Algerian classical music is a musical style that was reported in Algeria by Andalusian refugees who fled the inquisition of the Christian Kings from the 11th century, it will develop considerably in the cities of the North of the Algeria. This music is characterized by a large technical research and focuses mainly on twelve long Noubate "series", its main instruments are the mandolin, violin, lute, guitar, zither, flute and piano. Among the most noted interpreters, there are Bahdja Rahal, Cheikh El Hadj Mohamed El Ghafour, Nasserdine Chaouli, Cheikh Larbi Bensari, Nouri El Koufi as troops music such as El Mouahidia, El Mossilia, El Fakhardjia, Es Sendoussia and El-Andalusians.

Folk music is primarily distinguished by several styles. Bedouin music is characterized by the poetic songs that interpret the pastoralists in the area of the Highlands. It is based on of long kacida (poems) single rhyme and the monotonous sound of the flute. In general this music focuses on themes in love, religious and epic. Among the great performers, there is Khelifi Ahmed and Abdelhamid Ababsa Rahab Tahar. Kabyle music is based on a rich repertoire that is poetry and old tales passed through generations. Some songs address the theme of exile, love and politics, among others. Great performers are: Cheikh El Hasnaoui, Slimane Azem, Aït Menguellet, Idir, Kamel Messaoudi, Lounès Matoub or even Takfarinas. Shawiya music is a folklore diverse areas of the aurès mountains. Traditional music is well represented by many Aurassian singers. The first singers who have had international success are Aissa Jermouni (he sung at the Olympia in 1937) 307 and Ali Khencheli. Rahaba music style is unique to the Aures. Souad Massi is a becoming famous Algerian singer of traditional songs.

Aures region. In addition, several styles of music exist as the known arabo-andalous, one of the singers Chaoui style is Salim Hallali. Several singers of the aurès mountains were inspired by this style as Youcef Boukhantech. Tergui music is sung in Tuareg languages generally, Tinariwen had a world wide success. Finally, the staïfi music is born in Sétif and remains a unique style of its kind.

Modern music is available in several facets: raï music is a style typical of Western Algeria with his two fiefs are Oran and Sidi Bel Abbès. Its modern development was initiated in the 1970s when it adds a modern instrumentation to the image of the electric guitar, synthesizer and drums. This style was also influenced by Western music such as rock, reggae and the funk. But what would give a particular boom, it was the arrival on the music scene such as Hadj Brahim talented performers, said Khaled, Cheb Mami, Cheb Hasni, Faudel, Rachid Taha, Raina Rai, Reda Taliani, Cheb Anouar, Cheb Bilal, Cheb Abdou or even Cheba Djenet and Cheba Zahouania a. Music rap, relatively recent style in Algeria, is experiencing significant growth with the emergence of groups such as MBS, Double Barrel, Intik Hamma Boys. Your themes of this music generally revolve around social evils and love. In addition, several singers prefer Arab classical style as the Warda Al-Jazairia features.

Sports

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2011) |

Cuisine

Algerian cuisine is rich and diverse. The country was considered as the "granary of Rome". It offers a component of dishes and varied dishes, depending on the region and according to the seasons. This cuisine uses cereals as the main products, since always it is produced with abundance in the country. There is not a dish where cereals are not present.

Algerian cuisine varies from one region to another, according to seasonal vegetables. It can be prepared using meat, fish, vegetables. Among the dishes known, couscous, the chorba, the Rechta, the Chakhchoukha, the Berkoukes, the Shakshouka, the Mthewem, the Chtitha, the Mderbel, the Dolma, the Brik or Bourek, the Garantita, Lham'hlou, etc. Merguez sausage is very used in Algeria, but it differs, depending on the region and on the added spices.

The cakes are marketed and can the found in cities either in Algeria or in Europe or North America. However, traditional cakes made at home have a vast directory of revenue, according to the habits and customs of each family. Among these cakes, there are Tamina, Chrik, Garn logzelles, Griouech, Kalb el-louz, Makroud, Mbardja, Mchewek, Samsa, Tcharak, Baghrir, Khfaf, Zlabia, Aarayech, Ghroubiya, Mghergchette. The Algerian pastry also contains Tunisian or French cakes and it is marketed. The bread may be cooked such as Kessra or Khmira or Harchaya, chopsticks and so-called washers Khoubz dar or Matloue.

Landscapes and monuments

-

Roman ruins of Timgad (northeast)

-

El-Kantara in Biskra (south)

-

Mt. Tahat in the Ahaggar Mountains (far south) – highest point in the country (3003m)

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

There are several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Algeria[96] including Al Qal'a of Beni Hammad, the first capital of the Hammadid empire; Tipasa, a Phoenician and later Roman town; and Djémila and Timgad, both Roman ruins; M'Zab Valley, a limestone valley containing a large urbanized oasis; also the Casbah of Algiers is an important citadel. The only natural World Heritage Sites is the Tassili n'Ajjer, a mountain range.

Tourism

The development of the tourism sector in Algeria had previously been hampered by a lack of facilities, but since 2004 a broad tourism development strategy has been implemented resulting in many hotels of a high modern standard being built.

Affiliations

Algeria is a member of the following organizations:[53]

| Organization | Dates |

| since 10 August 1962 | |

| since 16 August 1962 | |

| since 1969 | |

| African Union | since 2002 |

See also

Notes

Template:Contains Tifinagh text

- ^ In Algeria, Tamazight has been constitutionally recognized as a national language. The Algerian government recognizes that the varieties of Berber languages in Algeria are national and regional languages which must be presereved. Algeria's official name in Berber is as follows:

- Berber languages, Tifinagh script: ⵜⴰⴳⴷⵓⴷⴰ ⵜⴰⵎⴳⴷⴰⵢⵜ ⵜⴰⵖⴻⵔⴼⴻⵏⵜ ⵜⴰⵣⴰⵢⵔⵉⵜ

References

- ^ (28 November 1996). Constitution of Algeria, Art. 11 (in Arabic).Office of President of Algeria. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ (28 November 1996). Constitution of Algeria Art. 11. Office of President of Algeria. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ (28 November 1996). Constitution of Algeria Art. 3. Office of President of Algeria. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ a b

Staff (undated). "Population et Démographie" (in French). Algerian Office of National Statistics. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d "Algeria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ^ Staff (undated). "Distribution of Family Income – Gini Index". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Human Development Report 2011. Human Development Index Trends" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Could the UK drive on the right? map at the BBC

- ^ Staff (10 April 2010). "Présentation de l'Algérie" (["Presentation of Algeria"]) (in French). French Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "L'Algérie crée une académie de la langue amazigh" (in French).

- ^ "La mondialisation, une chance pour la francophonie" (in French).

- ^ Radicati di Brozolo, Luca G. (1990). "Benemar v. Embassy of the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria". American Journal of International Law. 84 (2): 573–577. doi:10.2307/2203476.

- ^ CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ^ al-Idrisi, Muhammad (12th century). Nuzhat al-Mushtaq.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Abderahman, Abderrahman (1377). History of Ibn Khaldun – Volume 6.

- ^ Etymologie du toponyme "Aldjazair". Scribd.com. Retrieved on 14 May 2012.

- ^ Brett, Michael; Fentress, Elizabeth (1997). "Berbers in Antiquity". The Berbers. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20767-2. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Tassili n’Ajjer: birthplace of ancient Egypt?. Philipcoppens.com. Retrieved on 14 May 2012.

- ^ Paleoanthropological Research at Ain Hanech, Algeria. Stoneageinstitute.org. Retrieved on 14 May 2012.

- ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). p. XV. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Khaldūn, Ibn (1852). Histoire des Berbères et des dynasties musulmanes de l'Afrique Septentrionale Par Ibn Khaldūn, William MacGuckin Slane (in French). pp. X. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Barbary Pirates—Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911". Penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b Robert Davis (2003). "Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500–1800". Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0333719662

- ^ "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast".

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (Spring 2007). "Jefferson Versus the Muslim Pirates". City Journal. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ^ "The Mysteries and Majesties of the Aeolian Islands". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Monte Sant'Angelo. centrovacanzeoriente.it

- ^ "History of Menorca".

- ^ "When Europeans were slaves: Research suggests white slavery was much more common than previously believed". Ohio State Research COmmunications. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ Rees Davies, "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast". BBC. 1 July 2003.

- ^ Mackie, Erin Skye, Welcome the Outlaw: Pirates, Maroons, and Caribbean Countercultures Cultural Critique – 59, Winter 2005, pp. 24–62

- ^ "Barbary Pirates – Encyclopædia Britannica".

- ^ Eliakim Littell (1836). The Museum of foreign literature, science and art. E. Littell. pp. 231–. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "Background Note: Algeria".

- ^ Alistair Horne, (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York Review Books Classics). 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ [clarification needed] Gallica.bnf.fr. La démographie figurée de l'Algérie (in French). op. cit.. pp. 260–261.

- ^ Randell, Keith. France – Republic, Monarchy, and Empire.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (2006). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962 (New York Review Books Classics). 1755 Broadway, New York, NY 10019: NYRB Classics. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Country Data". Country-data.com. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Smith, Andrea L. (2006). Colonial Memory and Postcolonial Europe. Indiana University Press.

- ^ "French 'Reparation' for Algerians". BBC News. 6 December 2007.

- ^ Prochaska, David. "That Was Then, This Is Now: The Battle of Algiers and After". p. 141. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ New, The. (2008-11-19) nytimes.com, algeria's liberation terrorism and arabization, 2008. Topics.blogs.nytimes.com. Retrieved on 14 May 2012.

- ^ John Douglas Ruedy (1 August 2005). Modern Algeria: The Origins And Development of a Nation. Indiana University Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-253-21782-0. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Alec G. Hargreaves; Mark McKinney (1997). Post-Colonial Cultures in France. Psychology Press. pp. 104–. ISBN 978-0-415-14487-2. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ Algeria. Mideastnews.com. Retrieved on 14 May 2012.

- ^ Arabic German Consulting www.Arab.de. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ "Algeria Officially Lifts State of Emergency". CNN. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ MHerrera.org and Burt, Christopher C. (2007). Extreme Weather – A Guide and Record Book. W.W. Norton Press. Template:WebCite

- ^ "Democracy Index 2010" (PDF). eiu.com.

- ^ "Freedom of the Press 2009" (PDF). Freedom House. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Algeria Deputies Scrap Term Limit". BBC News. 12 November 2008. Archived from the original on 14 November 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l

"Africa: Algeria". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Articles: 85, 87, 77, 78 and 79 of the Algerian constitution Algerian government. "Constitution". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ Article 102 of the Algerian constitution

- ^ Article 42 of the Algerian constitution – Algerian Government. "Algerian constitution الحـقــوق والحــرّيـات". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ^ a b Hackett, James (ed.) (5 February 2008). The Military Balance 2008. International Institute for Strategic Studies. Europa. ISBN 978-1-85743-461-3. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Venezuela's Chavez To Finalise Russian Submarines Deal". Breitbart.com. Agence France-Presse. 14 June (unknown year). Retrieved 31 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)[dead link] - ^ "Algeria Cancels Weapons Deal over Israeli Parts". Info Prod Research. Archived from the original on 1 January 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Bin Ali calls for reactivating Arab Maghreb Union, Tunisia-Maghreb, Politics". ArabicNews.com. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Table (undated). "Country Comparison:: Natural Gas – Proved Reserves". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Algeria Country Analysis Brief". Energy Information Administration. 2005-03. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Staff (undated). "Algeria: Financial Sector Profile". Making Finance Work for Africa. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Brtsis, Brief on Russian Defence, Trade, Security and Energy". Brtsis.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ "Russia Agrees Algeria Arms Deal, Writes Off Debt". Reuters. 11 March 2006.

- ^ Marsaud, Olivia (10 March 2006). "La Russie efface la dette algérienne" (in French). Radio France Internationale. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Algeria Non-Oil Exports Surge 41%. Nuqudy (25 January 2012)

- ^ a b Arredi, Barbara; Poloni, Estella S.; Paracchini, Silvia; Zerjal, Tatiana; Dahmani, M. Fathallah; Makrelouf, Mohamed; Vincenzo, L. Pascali; Novelletto, Andrea; Tyler-Smith, Chris (7 June 2004). "A Predominantly Neolithic Origin for Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in North Africa". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75 (2): 338–45. doi:10.1086/423147. PMC 1216069. PMID 15202071.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Algeria – Population". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ UNESCO (2009). "Diversité et interculturalité en Algérie" (PDF). UNESCO. p. 9.

- ^ Ruedy, John Douglas (2005). Modern Algeria – The Origins and Development of a Nation. Indiana University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-253-21782-0.

- ^ De Azevedo, Raimond Cagiano (1994). Migration and Development Co-Operation. Council of Europe. p. 25. ISBN 978-92-871-2611-5.

- ^ Slackman, Michael (26 May 2007). "A Quiet Revolution in Algeria: Gains by Women". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "World Refugee Survey 2008". U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. p. 34. Archived from Refugees.org the original on 26 January 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Home: Only 46,000 People Benefit from Humanitarian Aid in Tindouf Camps, Says Former Polisario Leader". Map.ma. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Buckley, Cara (4 June 2008). "Western Sahara's Conflict Traps Refugees in Limbo". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Staff (5 September 2007). "Western Sahara: Lack of Donor Funds Threatens Humanitarian Projects". IRIN. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Staff (4 August 2009). "Chinese Migrants in Algiers Clash". BBC News. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Stokes, Jamie (2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East: L to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 21.

- ^ Willem Adriaan Veenhoven, Winifred Crum Ewing, Stichting Plurale Samenlevingen (1975). Case studies on human rights and fundamental freedoms: a world survey, Volume 1. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 263.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oxford Business Group (2008). The Report: Algeria 2008. Oxford Business Group. p. 10.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Oxford Business Group (2011). The Report: Algeria 2011. Oxford Business Group. p. 9.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Marion Mill Preminger (1961). The sands of Tamanrasset: the story of Charles de Foucauld. Hawthorn Books.

- ^ Collins, Roger (2000). "XIV". Vandal Africa, 429–533. Cambridge University Press. p. 124.

- ^ Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, p. 4

- ^ Ruedy, John Douglas (2005), Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation, Indiana University Press, p. 22, ISBN 0-253-21782-2

- ^ Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 29, ISBN 1-85065-177-9

- ^ Leclerc, Jacques (5 April 2009). "Algérie: Situation géographique et démolinguistique". L'aménagement linguistique dans le monde (in French). Université Laval. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ [unreliable source?] "Ibadis and Kharijis". (via Angelfire). Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Staff (14 September 2007). "Algeria". 2007 International Religious Freedom Report. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor (via the US State Department). Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress Country Studies – Algeria.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2009 – Proportion of international migrant stocks residing in countries with very high levels of human development (%)". Hdrstats.undp.org. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tahar Djaout French Publishers' Agency and France Edition, Inc. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Mohammed Khadda official site. Retrieved 4 April 2006.

- ^ Official biography

- ^ UNESCO. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Retrieved 25 September 2011.

Bibliography

- Ageron, Charles-Robert (1991). Modern Algeria – A History from 1830 to the Present. Translated from French and edited by Michael Brett. London: Hurst. ISBN 978-0-86543-266-6.

- Aghrout, Ahmed; Bougherira, Redha M. (2004). Algeria in Transition – Reforms and Development Prospects. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34848-5.

- Bennoune, Mahfoud (1988). The Making of Contemporary Algeria – Colonial Upheavals and Post-Independence Development, 1830–1987. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30150-3.

- Fanon, Frantz (1966; 2005 paperback). The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press. ASIN B0007FW4AW, ISBN 978-0-8021-4132-3.

- Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-61964-1, ISBN 978-1-59017-218-6 (2006 reprint)

| class="col-break " |

- Laouisset, Djamel (2009). A Retrospective Study of the Algerian Iron and Steel Industry. New York City: Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61761-190-2.

- Roberts, Hugh (2003). The Battlefield – Algeria, 1988–2002. Studies in a Broken Polity. London: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-85984-684-1.

- Ruedy, John (1992). Modern Algeria – The Origins and Development of a Nation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34998-9.

- Stora, Benjamin (2001). Algeria, 1830–2000 – A Short History. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3715-1.

- Sidaoui, Riadh (2009). "Islamic Politics and the Military – Algeria 1962–2008". Religion and Politics – Islam and Muslim Civilisation. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-7418-5.

|}

External links

- People's Democratic Republic of Algeria official government website

- "Algeria". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Algeria web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Algeria at Curlie

Wikimedia Atlas of Algeria

Wikimedia Atlas of Algeria- Template:Wikitravel

- Key Development Forecasts for Algeria from International Futures

- Use dmy dates from July 2012

- Algeria

- Arabic-speaking countries and territories

- African countries

- Countries of the Mediterranean Sea

- French-speaking countries

- G15 nations

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the Arab League

- Member states of OPEC

- Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- Member states of the Union for the Mediterranean

- Member states of the United Nations

- North African countries

- West African countries

- Republics

- Requests for audio pronunciation (Arabic)

- Requests for audio pronunciation (Berber)

- States and territories established in 1962

- Southern Mediterranean countries