John McCain

John McCain | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Arizona | |

| Assumed office January 3 1987 Serving with Jon Kyl | |

| Preceded by | Barry Goldwater |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona's 1st district | |

| In office January 3 1983 – January 3 1987 | |

| Preceded by | John Jacob Rhodes Jr. |

| Succeeded by | John Jacob Rhodes III |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 29, 1936 Coco Solo Naval Air Station, Panama Canal Zone |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Carol Shepp (m. 1965, div. 1980) Cindy Hensley McCain (m. 1980) |

| Children | Douglas (b. ~1960), Andrew (b. ~1962), Sidney (b. 1966), Meghan (b. 1984), John Sidney IV "Jack" (b. 1986), James (b. 1988), Bridget (b. 1991) |

| Alma mater | United States Naval Academy |

| Profession | Naval aviator, Politician |

| Signature |  |

| Website | U.S. Senator John McCain |

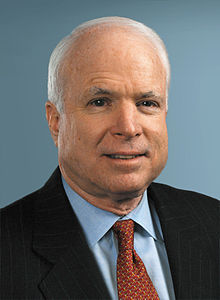

Template:FixHTMLTemplate:JohnMcCainSegmentsUnderInfoBox Template:FixHTML John Sidney McCain III (born August 29, 1936) is the senior United States Senator from Arizona and presumptive Republican Party nominee for President of the United States in the upcoming 2008 election.

McCain graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1958 and became a naval aviator, flying attack aircraft from carriers. During the Vietnam War, he nearly lost his life in the 1967 USS Forrestal fire. Later that year while on a bombing mission over North Vietnam, he was shot down, badly injured, and captured as a prisoner of war by the North Vietnamese. He spent five and a half years as a prisoner of war, experiencing episodes of torture.

McCain retired from the Navy in 1981 and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Arizona in 1982. After serving two terms, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1986, winning re-election in 1992, 1998, and 2004. While generally adhering to conservative principles, McCain established a reputation as a political maverick for disagreeing with his party on several key issues. Surviving the Keating Five scandal of the 1980s, he made campaign finance reform one of his signature concerns, eventually co-sponsoring the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act in 2002.

McCain lost the Republican nomination in the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush. He ran again for Republican presidential nomination in 2008 and gained enough delegates to become the presumptive nominee in March 2008.

Early life and military career

Formative years and education

McCain was born at Coco Solo Naval Air Station[1] in Panama to naval officer John S. McCain, Jr. (1911–1981) and Roberta (Wright) McCain (b. 1912). At that time, the Panama Canal was under American control, and the McCain family was stationed in the Panama Canal Zone.

McCain has Scots-Irish[2] and English[3] ancestry. His father and paternal grandfather both became four-star United States Navy admirals.[4] His family (including his older sister Sandy and younger brother Joe)[1] followed his father to various naval postings in the United States and the Pacific. Altogether, he attended about 20 schools.[5]

As a child, John McCain was a quiet, dependable, and courteous member of his family.[1] He also had a quick temper and an aggressive drive to compete and prevail.[6][7]

In 1951, the family settled in Northern Virginia, and McCain attended Episcopal High School, a private preparatory boarding school in Alexandria.[8] In high school, he excelled at wrestling[9] and graduated in 1954.[7]

Following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, McCain entered the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. There, he was a friend and leader for many of his classmates, and stood up for people who were being bullied. He also became a lightweight boxer.[4][10] McCain had conflicts with higher-ups, and he was disinclined to obey every rule, which contributed to a low class rank (894/899) that he did not aim to improve.[11][12][13][14] McCain did well in academic subjects that interested him, such as literature and history, but only studied enough to pass math.[4] McCain graduated in 1958.[12]

Military service and marriages

John McCain's pre-combat duty began when he was commissioned an ensign, and started two and a half years of training as a naval aviator at Pensacola.[15] There he also earned a reputation as a party man.[5] Graduating from flight school in 1960,[16] he became a naval pilot of attack aircraft. McCain was then stationed in A-1 Skyraider squadrons[17] on the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid and USS Enterprise,[18] in the Caribbean Sea and in the Mediterranean Sea.[19] He survived two airplane crashes and a collision with power lines.[19]

On July 3 1965 McCain married Carol Shepp, a model originally from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[11] McCain adopted her two young children Douglas and Andrew.[20][18] He and Carol then had a daughter named Sidney.[21][22]

McCain requested a combat assignment,[23] and in December 1966 was assigned to the aircraft carrier USS Forrestal flying A-4 Skyhawks.[24][25] McCain's combat duty began when he was 30 years old. In summer 1967, Forrestal was assigned to a bombing campaign during the Vietnam War.[11][26] McCain and his fellow pilots were frustrated by micromanagement from Washington,[27] and he would later write that "In all candor, we thought our civilian commanders were complete idiots who didn’t have the least notion of what it took to win the war."[26]

By then a lieutenant commander, McCain was almost killed on July 29, 1967 when he was at the epicenter of the Forrestal fire. McCain escaped from his burning jet and was trying to help another pilot escape when a bomb exploded;[28] McCain was struck in the legs and chest by fragments.[29] The ensuing fire killed 134 sailors and took 24 hours to control.[30][31] With the Forrestal out of commission, McCain volunteered for assignment with the USS Oriskany.[32]

John McCain's capture and imprisonment began on October 26, 1967. He was flying his twenty-third bombing mission over North Vietnam, when his A-4E Skyhawk was shot down by a missile over Hanoi.[33][34] McCain fractured both arms and a leg, and then nearly drowned, when he parachuted into Trúc Bạch Lake in Hanoi.[33] After he regained consciousness, a crowd attacked him, crushed his shoulder with a rifle butt, and bayoneted him;[33] he was then transported to Hanoi's main Hoa Lo Prison, nicknamed the "Hanoi Hilton".[34]

Although McCain was badly wounded, his captors refused to treat his injuries, instead beating and interrogating him to get information.[36] Only when the North Vietnamese discovered that his father was a top admiral did they give him medical care[36] and announce his capture. His status as a prisoner of war (POW) made the front pages of The New York Times[37] and The Washington Post.[38]

McCain spent six weeks in the Hoa Loa hospital while receiving marginal care.[33] Now having lost 50 pounds (23 kg), in a chest cast, and with his hair turned white,[33] McCain was sent to a different camp on the outskirts of Hanoi[39] in December 1967, into a cell with two other Americans who did not expect him to live a week.[40] In March 1968, McCain was put into solitary confinement, where he would remain for two years.[41]

In mid-1968, McCain's father was named commander of all U.S. forces in the Vietnam theater, and McCain was offered early release.[42] The North Vietnamese wanted to appear merciful for propaganda purposes,[43] and also wanted to show other POWs that elites like McCain were willing to be treated preferentially.[42] McCain turned down the offer of repatriation; he would only accept the offer if every man taken in before him was released as well.[33]

In August of 1968, a program of severe torture began on McCain.[44] McCain was subjected to repeated beatings and rope bindings, at the same time as he was suffering from dysentery.[44] After four days, McCain made an anti-American propaganda "confession".[33] He has always felt that his statement was dishonorable,[45] but as he would later write, "I had learned what we all learned over there: Every man has his breaking point. I had reached mine."[46] His injuries left him permanently incapable of raising his arms above his head.[47] He subsequently received two to three beatings per week because of his continued refusal to sign additional statements.[48] Other American POWs were similarly tortured and maltreated in order to extract "confessions" and propaganda statements, with many enduring even worse treatment than McCain.[49]

McCain refused to meet with various anti-war groups seeking peace in Hanoi, wanting to give neither them nor the North Vietnamese a propaganda victory.[50] From late 1969 on, treatment of McCain and many of the other POWs became more tolerable,[51] while McCain continued to be an active resister against the camp authorities.[52] McCain and other prisoners cheered the B-52-led U.S. "Christmas Bombing" campaign of December 1972 as a forceful measure to push North Vietnam to terms.[46][53]

Altogether, McCain was held as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for five and a half years. He was finally released from captivity on March 14, 1973.[54] McCain's return to the United States reunited him with his wife and family. His wife Carol had suffered her own crippling ordeal during his captivity, due to an automobile accident in December 1969.[55] As a returned POW, McCain became a celebrity of sorts.[55]

McCain underwent treatment for his injuries, including months of grueling physical therapy,[56] and attended the National War College in Fort McNair in Washington, D.C. during 1973–1974.[55][16] Having been rehabilitated, by late 1974, McCain had his flight status reinstated,[55] and in 1976 he became commanding officer of a training squadron stationed in Florida.[55][57] He turned around an undistinguished unit and won the squadron its first Meritorious Unit Commendation.[56] During this period, the McCains' marriage began to falter;[58] he would later accept blame.[58]

McCain served as the Navy's liaison to the U.S. Senate, beginning in 1977.[59] He would later say it represented "[my] real entry into the world of politics and the beginning of my second career as a public servant".[55] McCain played a key behind-the-scenes role in gaining congressional financing for a new supercarrier against the wishes of the Carter administration.[60][56]

In 1979,[56] McCain met and began a relationship with Cindy Lou Hensley, a teacher from Phoenix, Arizona, the only child of the founder of Hensley & Co.[58] His wife Carol accepted a divorce in February of 1980,[56] effective in April of 1980.[20] The settlement included two houses, and financial support for her ongoing medical treatments for injuries resulting from the 1969 car accident; they would remain on good terms.[58] McCain and Hensley were married on May 17, 1980.[11] John and Cindy McCain entered into a prenuptial agreement that keeps most of her family's assets under her name;[61] they would always keep their finances apart and file separate income tax returns.[61]

McCain decided to leave the Navy. He was unlikely to ever make full admiral, as he had poor annual physicals and had been given no major sea command.[62] In early 1981, he was told he would be made rear admiral; he declined the prospect, as he already made plans to run for Congress and said he could "do more good there."[63]

McCain retired from the Navy on April 1, 1981,[64] as a captain,[65] and headed west to Arizona. His seventeen military awards and decorations include the Silver Star, Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, Distinguished Flying Cross, and Navy Commendation Medal, and are for actions before, during, and after his time as a POW.[65]

House and Senate career, 1982–2000

U.S. Congressman and a growing family

McCain set his sights on becoming a Congressman because he was interested in current events, was ready for a new challenge, and had developed political ambitions during his time as Senate liaison.[66][58][67] Living in Phoenix, he went to work for Hensley & Co., his new father-in-law Jim Hensley's large Anheuser-Busch beer distributorship, as Vice President of Public Relations.[58] There he gained political support among the local business community,[59] meeting powerful figures such as banker Charles Keating, Jr., real estate developer Fife Symington III,[68] and newspaper publisher Darrow "Duke" Tully.[59] In 1982, McCain ran as a Republican for an open seat in Arizona's 1st congressional district.[69] As a newcomer to the state, McCain was hit with repeated charges of being a carpetbagger.[58] McCain responded to a voter making the charge with what a Phoenix Gazette columnist would later label as "the most devastating response to a potentially troublesome political issue I've ever heard":[58]

Listen, pal. I spent 22 years in the Navy. My father was in the Navy. My grandfather was in the Navy. We in the military service tend to move a lot. We have to live in all parts of the country, all parts of the world. I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and living and spending my entire life in a nice place like the First District of Arizona, but I was doing other things. As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.[58][70]

With the assistance of local political endorsements, his Washington connections, as well as money that his wife lent to his campaign,[59] McCain won a highly contested primary election.[58] He then easily won the general election in the heavily Republican district.[58]

In 1983, McCain was elected to lead the incoming group of Republican representatives.[58] Also that year, he opposed creation of a federal Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, but admitted in 2008: "I was wrong and eventually realized that, in time to give full support [in 1990] for a state holiday in Arizona."[71][72]

McCain's politics at this point were mainly in line with President Ronald Reagan, and he was active on Indian Affairs bills.[73] He won re-election to the House easily in 1984.[58]

In 1984 McCain and his wife Cindy had their first child together, daughter Meghan. She was followed two years later by son John Sidney IV (known as "Jack"), and in 1988 by son James.[74] Although McCain chooses not to make it a "talking point," James ("Jimmy") served in Iraq until February 2008.[75][76] In 1991, Cindy McCain brought an abandoned three-month old girl needing medical treatment to the U.S. from a Bangladeshi orphanage run by Mother Teresa;[77] the McCains decided to adopt her, and named her Bridget.[78]

First two terms in U.S. Senate

McCain's Senate career began in January 1987, after longtime American conservative icon and Arizona fixture Barry Goldwater retired as United States Senator from Arizona.[79] McCain defeated his Democratic opponent, former state legislator Richard Kimball, by 20 percentage points in the 1986 election.[79][59]

Upon entering the Senate, McCain became a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, with whom he had formerly done his Navy liaison work; he also joined the Commerce Committee and the Indian Affairs Committee.[79] He continued to support the Native American agenda.[80] McCain was a strong supporter of the Gramm-Rudman legislation that enforced automatic spending cuts in the case of budget deficits.[81]

McCain soon gained national visibility. He delivered a well-received speech at the 1988 Republican National Convention,[82] he was mentioned by the press as a short list vice-presidential running mate for Republican nominee George H. W. Bush,[82][79] and he was named chairman of Veterans for Bush.[83]

McCain became enmeshed in a scandal during the 1980s when he was one of five United States Senators comprising the so-called "Keating Five".[84] Between 1982 and 1987, McCain had received $112,000 in legal[85] political contributions from Charles Keating Jr. and his associates at Lincoln Savings and Loan Association, along with trips on Keating's jets[84] that McCain failed to repay until two years later.[86] In 1987, McCain was one of the five senators whom Keating contacted in order to prevent the government’s seizure of Lincoln, which was by then insolvent and being investigated for making questionable efforts to regain solvency. McCain met twice with federal regulators to discuss the government's investigation of Lincoln.[84]

On his Keating Five experience, McCain said: "The appearance of it was wrong. It's a wrong appearance when a group of senators appear in a meeting with a group of regulators, because it conveys the impression of undue and improper influence. And it was the wrong thing to do."[87] Federal regulators ultimately filed a civil suit against Keating. The five senators came under investigation for attempting to influence the regulators. In the end, none of the senators were charged with any crime. McCain was rebuked by the Senate Ethics Committee for exercising "poor judgment",[87] but their 1991 report said that McCain's "actions were not improper nor attended with gross negligence and did not reach the level of requiring institutional action against him."[85] In his 1992 re-election bid, the Keating Five affair was not a major issue,[88][89] and he won handily, gaining 56 percent of the vote to defeat Democratic community and civil rights activist Claire Sargent and independent former Governor Evan Mecham.

During the 1990s, McCain developed a reputation for independence.[90] He took pride in taking on battles against establishment forces, was willing to challenge party leadership, and became hard to categorize politically.[90]

As a member of the 1991–1993 Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, chaired by Democrat and fellow Vietnam War veteran John Kerry, McCain investigated the fate of U.S. service personnel listed as missing in action during the Vietnam War.[91] The committee's unanimous report stated there was "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia."[92] Helped by McCain's efforts, in 1995 the U.S. normalized diplomatic relations with Vietnam.[93] McCain was vilified by some POW/MIA activists who believed large numbers of Americans were still held against their will in Southeast Asia; they objected to McCain not sharing their belief and his pushing for Vietnam normalization.[94][95][93]

McCain made attacking the corrupting influence of large-scale contributions — from corporations, labor unions, other organizations, and wealthy individuals — on American politics his signature issue.[96] Starting in 1994, he worked with Democratic Wisconsin Senator Russ Feingold on campaign finance reform;[96] their McCain-Feingold bill would attempt to put limits on "soft money".[96] McCain and Feingold's efforts were opposed by some of the moneyed interests targeted, by incumbents in both parties, by those who felt spending limits impinged on free political speech, and by those who wanted to lessen the power of what they saw as media bias.[96] Despite sympathetic coverage in the media, initial versions of the McCain-Feingold Act were filibustered and never came to a vote.[97] The term "maverick Republican" became a label frequently applied to McCain;[96][98] he has also used the term himself.[99]

McCain also attacked pork barrel spending within Congress.[96] He was instrumental in pushing through approval of the Line Item Veto Act of 1996,[96] which gave the president power to veto individual spending items. It was one of McCain's biggest Senate victories,[96] although in 1998 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the act unconstitutional.[100]

In the 1996 presidential election, McCain was again on the short list of possible vice-presidential picks for Republican nominee Bob Dole.[101][88] The following year, Time magazine named McCain as one of the "25 Most Influential People in America".[102]

In 1997, McCain became chairman of the powerful Senate Commerce Committee; he was criticized for accepting funds from corporations and businesses under the committee's purview,[96] but in response said the restricted contributions he received were not part of the big-money nature of the campaign finance problem.[96] McCain took on the tobacco industry in 1998, proposing legislation that would increase cigarette taxes to fund anti-smoking campaigns and reduce the number of teenage smokers, increase research money on health studies, and help states pay for smoking-related health care costs.[103][96] Supported by the Clinton administration but opposed by the industry and most Republicans, the bill failed to gain cloture.[103]

McCain won re-election to a third senate term in November 1998, prevailing in a landslide over his Democratic opponent, environmental lawyer Ed Ranger.[96] In 1999, McCain shared the Profile in Courage Award with Feingold for their work in trying to enact their campaign finance reform,[104] although the bill was still failing repeated attempts to gain cloture.[97]

In August 1999, his memoir Faith of My Fathers, co-authored with Mark Salter, was published.[105] The most successful of his writings, it received positive reviews,[106] became a bestseller,[107] and was later made into a movie. The book traces McCain's family background and childhood, also covering his time at Annapolis, and his service as a naval aviator before and during the Vietnam War, concluding with his release from captivity in 1973. As one reviewer put it, the book describes "the kind of challenges that most of us can barely imagine. It's a fascinating history of a remarkable military family."[108]

2000 presidential campaign

McCain announced his candidacy for president on September 27, 1999 in Nashua, New Hampshire,[109] saying he was staging "a fight to take our government back from the power brokers and special interests, and return it to the people and the noble cause of freedom it was created to serve".[105] The leader for the Republican nomination was Texas Governor George W. Bush, who had the political and financial support of most of the party establishment.[110]

McCain focused on the New Hampshire primary, where his message held appeal to independents.[111] He traveled on a campaign bus called the Straight Talk Express.[105] He held many town hall meetings, answering every question voters had, in a successful example of "retail politics". He used free media to compensate for his lack of funds;[105] one reporter later recounted that, "McCain talked all day long with reporters on his Straight Talk Express bus; he talked so much that sometimes he said things that he shouldn't have, and that's why the media loved him."[112] On February 1, 2000, he won the primary with 49 percent of the vote to Bush's 30 percent. A McCain victory in the crucial South Carolina primary might give his campaign unstoppable momentum;[113] a degree of panic crept into the Bush campaign and the Republican establishment.[105][113]

The Arizona Republic would write that the McCain-Bush primary contest in South Carolina "has entered national political lore as a low-water mark in presidential campaigns", while The New York Times called it "a painful symbol of the brutality of American politics".[105][114][115] A variety of interest groups that McCain had challenged in the past ran negative ads.[105] Bush borrowed McCain's earlier language of reform,[116] and declined to disassociate himself from a veterans activist who accused McCain (in Bush's presence) of having "abandoned the veterans" on POW/MIA and Agent Orange issues.[105][117]

Incensed,[117] McCain ran ads accusing Bush of lying and comparing the governor to Bill Clinton,[105] which Bush said was "about as low a blow as you can give in a Republican primary".[105] An unidentified party began a semi-underground smear campaign against McCain, delivered by push polls, faxes, e-mails, and flyers.[105] It claimed most infamously that McCain had fathered a black child out of wedlock (the McCains' dark-skinned daughter Bridget was adopted from Bangladesh), and also that his wife Cindy was a drug addict, that he was a homosexual, and that he was a "Manchurian Candidate" traitor or mentally unstable from his North Vietnam POW days.[105][114] The Bush campaign strongly denied any involvement with the attacks.[114]

McCain lost South Carolina on February 19, with 42 percent of the vote to Bush's 53 percent,[119] in part because Bush mobilized the state's evangelical voters[105] and outspent McCain.[120] The win allowed Bush to regain lost momentum.[119] McCain would say of the rumor spreaders, "I believe that there is a special place in hell for people like those."[78] According to one report, the South Carolina experience left McCain in a "very dark place".[114]

McCain's campaign never completely recovered from his defeat there, although he did rebound partially by winning in Arizona and Michigan on February 22.[121] He made a speech in Virginia Beach that criticized Christian leaders, including Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, as divisive conservatives,[114] declaring "... we embrace the fine members of the religious conservative community. But that does not mean that we will pander to their self-appointed leaders."[122] McCain lost the Virginia primary on February 29[123] and nine of the thirteen primaries on Super Tuesday to Bush.[124] With little hope of catching Bush's delegate lead, McCain withdrew from the race on March 9, 2000.[125] He endorsed Bush two months later,[126] and made occasional appearances with Bush during the general election campaign.[105]

Senate career after 2000

Remainder of third Senate term

McCain began 2001 by breaking with the new George W. Bush administration on a number of matters,[127] including HMO reform, climate change, and gun legislation;[127] McCain-Feingold was opposed by Bush as well.[127][97] In May 2001, McCain was one of only two Senate Republicans to vote against the Bush tax cuts.[127][128] Later, when Republican Senator Jim Jeffords became an Independent, throwing control of the Senate to the Democrats, McCain defended Jeffords against "self-appointed enforcers of party loyalty".[127] Indeed, there was speculation at the time,[129] and in years since,[130] about McCain himself possibly leaving the Republican Party. McCain has always adamantly denied that he ever considered doing so.[127][130]

After the September 11, 2001 attacks, McCain supported Bush and the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan.[127][131] He and then-Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman wrote the legislation that created the 9/11 Commission,[132] while he and Democratic Senator Fritz Hollings co-sponsored the Aviation and Transportation Security Act that federalized airport security.[133]

In March 2002, McCain-Feingold passed in both Houses of Congress and was signed into law by President Bush.[97][127] Seven years in the making, it was McCain's greatest legislative achievement.[127][134]

Meanwhile, in discussions over proposed U.S. action against Iraq, McCain was a strong supporter of the Bush administration's position.[127] He stated that Iraq was "a clear and present danger to the United States of America",[127] and voted accordingly for the Iraq War Resolution in October 2002.[127] He predicted that U.S. forces would be treated as liberators by a large number of the Iraqi people.[135] In May 2003, McCain voted against the second round of Bush tax cuts, saying it was unwise at a time of war.[128] By November 2003, after a trip to Iraq, McCain was publicly questioning Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, saying that more U.S. troops were needed;[136] the following year, McCain announced that he had lost confidence in Rumsfeld.[137]

In October 2003, McCain and Lieberman co-sponsored the Climate Stewardship Act that would have introduced a cap and trade system of greenhouse gases at the 2000 emissions level; the bill was defeated with 55 votes to 43 in the Senate.[138] They reintroduced modified versions of the Act two additional times, most recently in January 2007 with the co-sponsorship of Barack Obama, among others.[139]

In the 2004 U.S. presidential election, McCain was once again frequently mentioned for the vice-presidential slot, only this time as part of the Democratic ticket under nominee John Kerry.[140][141][142] McCain said that Kerry had never formally offered him the position and that he would not have accepted it if he had.[143][142][141] At the 2004 Republican National Convention, McCain supported Bush for re-election, praising Bush's management of the War on Terror since the September 11 attacks.[144] At the same time, the Senator defended Kerry's Vietnam war record.[145] By August 2004, McCain had the best favorable-to-unfavorable rating (55 percent to 19 percent) of any national politician.[144]

McCain was up for re-election as Senator in 2004; he defeated little-known Democratic schoolteacher Stuart Starky with his biggest margin of victory, garnering 77 percent of the vote.[146]

Fourth Senate term

McCain continued to support appointments of judges who "would strictly interpret the Constitution", adding Supreme Court confirmation votes in favor of John Roberts and Samuel Alito to those he had previously cast for Robert Bork and Clarence Thomas.[147] In May 2005, McCain led the so-called "Gang of 14" in the Senate, which established a compromise that preserved the ability of senators to filibuster judicial nominees, but only in "extraordinary circumstances".[148] The compromise took the steam out of the filibuster movement, but some Republicans remained disappointed that the compromise did not eliminate filibusters of judicial nominees in all circumstances.[149]

Breaking from his 2001 and 2003 votes, McCain supported the Bush tax cut extension in May 2006, saying not to do so would amount to a tax increase.[128] Working with Democratic Senator Ted Kennedy, McCain was a strong proponent of comprehensive immigration reform, which would involve legalization, guest worker programs, and border enforcement components. The Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act was never voted on in 2005, while the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2006 passed the Senate in May 2006 but failed in the House.[137] In June 2007, President Bush, McCain and others made the strongest push yet for such a bill, the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, but it aroused furious grassroots opposition among talk radio listeners and others as an "amnesty" program,[150] and twice failed to gain cloture in the Senate.[151]

Owing to his time as a POW, McCain has been recognized for his sensitivity to the detention and interrogation of detainees in the War on Terror. On October 3, 2005, McCain introduced the McCain Detainee Amendment to the Defense Appropriations bill for 2005, and the Senate voted 90–9 to support the amendment.[152] It prohibits inhumane treatment of prisoners, including prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, by confining military interrogations to the techniques in the U.S. Army Field Manual on Interrogation. Although Bush had threatened to veto the bill if McCain's amendment was included,[153] the President announced on December 15, 2005 that he accepted McCain's terms and would "make it clear to the world that this government does not torture and that we adhere to the international convention of torture, whether it be here at home or abroad".[154]

Meanwhile, McCain continued questioning the progress of the war in Iraq. In September 2005, he remarked upon Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Richard Myers' optimistic outlook on the war's progress: "Things have not gone as well as we had planned or expected, nor as we were told by you, General Myers."[155] In August 2006, he criticized the administration for continually understating the effectiveness of the insurgency: "We [have] not told the American people how tough and difficult this could be."[137] From the beginning, McCain strongly supported the Iraq troop surge of 2007.[156] The strategy's opponents labeled it "McCain's plan"[157] and University of Virginia political science professor Larry Sabato said, "McCain owns Iraq just as much as Bush does now."[137] The surge and the war were unpopular during most of the year, even within the Republican Party,[158] as McCain's presidential campaign was underway; faced with the consequences, McCain frequently responded, "I would much rather lose a campaign than a war."[159] In March 2008, McCain credited the surge strategy with reducing violence in Iraq, as he made his eighth trip to that country since the war began.[160]

2008 presidential campaign

John McCain formally announced he was seeking the presidency of the United States on April 252007 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[161] He stated that: "I’m not running for President to be somebody, but to do something; to do the hard but necessary things not the easy and needless things."[162] He also said that the United States should never fight a war without fully committing the necessary resources, unlike what initially occurred in Iraq.[162]

McCain's oft-cited strengths[163] as a presidential candidate for 2008 included national name recognition, sponsorship of major lobbying and campaign finance reform initiatives, leadership in exposing the Abramoff scandal,[164][165] his well-known military service and experience as a POW, his experience from the 2000 presidential campaign, and an expectation that he would capture Bush's top fundraisers.[163] During the 2006 election cycle, McCain attended 346 events[47] and helped raise more than $10.5 million on behalf of Republican candidates. McCain also became more willing to ask business and industry for campaign contributions, while maintaining that such contributions would not affect any official decisions he would make.[166]

McCain had fundraising problems in the first half of 2007, due in part to his support for the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007, which was unpopular among the Republican base electorate.[167][168] Large-scale campaign staff downsizing took place in early July, but McCain said he was not considering dropping out of the race.[168] Later that month, his campaign manager and campaign chief strategist both departed.[169] McCain slumped badly in national polls, often running third or fourth with 15 percent or less support.

McCain subsequently resumed his familiar position as a political underdog, riding the Straight Talk Express and taking advantage of free media such as debates and sponsored events.[170] By December 2007, the Republican race was unsettled, with none of the top-tier candidates dominating the race and all of them possessing major vulnerabilities with different elements of the Republican base electorate.[171] McCain was showing a resurgence, in particular with renewed strength in New Hampshire – the scene of his 2000 triumph – and was bolstered further by the endorsements of The Boston Globe, the Manchester Union-Leader, and almost two dozen other state newspapers,[172] as well as from Independent Democrat Senator Joe Lieberman.[173] McCain decided not to campaign significantly in the January 3 Iowa caucuses, which saw a win by former Governor of Arkansas Mike Huckabee.

All of this paid off when McCain won the New Hampshire primary on January 8, 2008, defeating former Governor of Massachusetts Mitt Romney in a close contest, to once again become one of the front-runners in the race.[174] On January 19, McCain placed first in the South Carolina primary, narrowly defeating Mike Huckabee.[175] Pundits credited the third-place finisher, Tennessee's former U.S. Senator Fred Thompson, with drawing votes from Huckabee in South Carolina, thereby giving a narrow win to McCain.[176] A week later, McCain won the Florida primary,[177] beating Romney again in a close contest; former Mayor of New York City Rudy Giuliani then dropped out and endorsed McCain.[178]

On February 5, Super Tuesday, McCain won both the majority of states and delegates in the Republican primaries, giving him a commanding lead toward the Republican nomination; Romney departed from the race on February 7.[179] McCain clinched a majority of the delegates and became the presumptive nominee by winning the Ohio primary and Texas primary on March 4, with the nomination to be made official in September at the 2008 Republican National Convention in Saint Paul, Minnesota.[180]

If he wins the presidency, John McCain’s birth (in Panama) would be the first presidential birth outside the current 50 states. A bipartisan legal review as well as a unanimous Senate resolution indicate that he is nevertheless a natural-born citizen of the United States, a constitutional requirement to become president.[181][182] Also, if inaugurated in 2009 at age 72 years and 144 days, he would be the oldest U.S. president upon ascension to the presidency,[183] and the second-oldest president to be inaugurated (Ronald Reagan was 73 years and 350 days old at his second inauguration).[184]

McCain has addressed concerns about his age and past health concerns, stating in 2005 that his health was "excellent".[185] He has been treated for a type of skin cancer called melanoma, and an operation in 2000 for that condition left a noticeable mark on the left side of his face.[186] McCain’s prognosis appears favorable, according to independent experts, especially because he has already survived without a recurrence for more than seven years.[186] In May 2008, McCain's campaign released his medical records for review to the Associated Press, and he was described as appearing cancer-free, having a strong heart and in general good health.[187]

After clinching enough delegates for the nomination, McCain's focus shifted toward the general election while Barack Obama and Hillary Rodham Clinton fought a prolonged battle for the Democratic nomination.[188] McCain staged a "biographical tour", introduced various policy proposals, and sought to improve his fundraising.[189][190] Cindy McCain, who accounts for most of the couple's wealth with an estimated net worth of $100 million,[61] made part of her tax returns public in May 2008.[191] The McCain campaign faced criticism about lobbyists in its midst,[192] and issued new rules in May 2008 calling for campaign staff to either cut lobbying ties or leave, so as to avoid any potential conflict of interest; five top aides left.[193][192] When Barack Obama became the Democrats' presumptive nominee on June 3, McCain proposed joint town hall meetings, and Obama expressed interest.[194]

Political positions

Various interest groups have given Senator McCain scores or grades as to how well his votes align with the positions of the group.[195] The American Conservative Union awarded McCain a lifetime rating of 82 percent through 2007,[196] while McCain has an average lifetime 13 percent "Liberal Quotient" from Americans for Democratic Action through 2007[197] (see chart for progressions over time).

The Almanac of American Politics rates congressional votes as liberal or conservative on the political spectrum, in three policy areas: economic, social, and foreign. For 2005-2006, McCain's average ratings were as follows: the economic rating was 59 percent conservative and 41 percent liberal, the social rating was 54 percent conservative and 38 percent liberal, and the foreign rating was 56 percent conservative and 43 percent liberal.[199]

Arizona Republic columnist and RealClearPolitics contributor Robert Robb, using a formulation devised by William F. Buckley, Jr., describes McCain as "conservative" but not "a conservative", meaning that while McCain usually tends towards conservative positions, he is not "anchored by the philosophical tenets of modern American conservatism".[200]

The two political issues that voters have been most concerned about in 2008 are the economy and Iraq.[201] On the economy, McCain would make the Bush tax cuts permanent instead of letting them expire, he would eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax so as to assist the middle-class, he would double the personal exemption for dependents, reduce the corporate tax rate, and offer a new research and development tax credit.[202][203] At the same time, he pledges to eliminate pork-barrel spending, freeze nondefense discretionary spending for a year or more, and reduce Medicare growth.[203] McCain is also opposed to extravagant salaries and severance deals of corporate CEOs.[203] On Iraq, McCain's goal is that by 2013 most of the servicemen and women will have returned, the Iraq War will have been won, and Iraq will be a functioning democracy, "although still suffering from the lingering effects of decades of tyranny and centuries of sectarian tension." McCain expects that by 2013, there will still be violence, but at a much-reduced level, and without American troops in a direct combat role.[204][205]

From the late 1990s until 2008, McCain was a board member of Project Vote Smart (PVS) which was set up by Richard Kimball, his 1986 Senate opponent.[206] PVS provides non-partisan information about the political positions of McCain[207] and other candidates for political office. Additionally, McCain uses his Senate web site,[208] and his 2008 campaign web site,[209] to describe his political positions.

Cultural and political image

John McCain's personal character has been a dominant feature of his public image.[210] This image includes the military service of both himself and his family,[211] his maverick political persona,[212] his temper,[213] his admitted problem of occasional ill-considered remarks,[214] and his devotion to his large blended family.[215]

McCain’s political appeal has been more nonpartisan and less ideological compared to many other national politicians.[216][217] His stature and reputation stem partly from his service in the Vietnam War.[218] He also carries physical vestiges of his war wounds, as well as his melanoma surgery;[219] when campaigning he quips, "I am older than dirt and have more scars than Frankenstein."[220]

While considering himself to be a straight-talking public servant, McCain acknowledges being impatient.[221] Other traits include a penchant for lucky charms,[222] a fondness for hiking,[223] and a sense of humor that has sometimes backfired spectacularly, as when he made a joke in 1998 about the Clintons that was not fit to print in newspapers.[224] McCain has not shied away from addressing his shortcomings, and apologizing for them.[225][226] He is known for sometimes being prickly[227] and hot-tempered[228] with Senate colleagues, but his relations with his own Senate staff have been more cordial, and have inspired loyalty towards him.[229][230]

Regarding his temper, or what might be viewed as passionate conviction,[213] McCain acknowledges it[231] while also saying that the stories have been exaggerated.[232][233] Having a temper is not unusual for U.S. leaders,[234] and McCain has employed both profanity[235] and shouting[233] on occasion. Such incidents have become less frequent over the years,[236][233] and Senator Joseph Lieberman has made this observation: "It is not the kind of anger that is a loss of control. He is a very controlled person."[233] Senator Thad Cochran, who has known McCain for decades and has battled him over earmarks,[233][237][238] has expressed much greater concern about a McCain presidency: "He is erratic. He is hotheaded. He loses his temper and he worries me."[233] Ultimately Cochran decided to support McCain for president, after it was clear he would win the nomination.[239]

All of John McCain's family members are on good terms with him,[215] and he has defended them against some of the negative consequences of his high-profile political lifestyle.[240][241] McCain's father battled alcoholism, and his wife battled addiction to painkillers; their efforts at self-improvement have become part of McCain’s family tradition as well.[242] His family's military tradition extends to the latest generation: son John Sidney IV ("Jack") is enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy,[215] son James has served with the Marines in Iraq,[243] and son Doug flew jets in the Navy.[215]

Writings by McCain

- Hard Call: Great Decisions and the Extraordinary People Who Made Them by John McCain, Mark Salter (Hachette, August 2007) ISBN 978-0-446-58040-3

- Character Is Destiny: Inspiring Stories Every Young Person Should Know and Every Adult Should Remember by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, October 2005) ISBN 1-4000-6412-0

- Why Courage Matters: The Way to a Braver Life by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, April 2004) ISBN 1-4000-6030-3

- Odysseus in America by Jonathan Shay, Max Cleland, John S. McCain (Scribner, November 2002) ISBN 0-7432-1156-1

- Worth the Fighting For by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, September 2002) ISBN 0-375-50542-3

- Unfinished Business: Afghanistan, the Middle East and Beyond — Defusing the Dangers That Threaten America's Security by Harlan Ullman, John S. McCain (Citadel Press, June 2002) ISBN 0-8065-2431-6

- Faith of My Fathers by John McCain, Mark Salter (Random House, August 1999) ISBN 0-375-50191-6 (later made into the 2005 television film Faith of My Fathers)

- "An Enduring Peace Built on Freedom: Securing America's Future" by John McCain Foreign Affairs, November/December 2007

- "How the POW's Fought Back", by John S. McCain III, Lieut. Commander, U.S. Navy, U.S. News and World Report, May 14, 1973 (reprinted for web under different title in 2008). Reprinted in Reporting Vietnam, Part Two: American Journalism 1969–1975 (The Library of America, 1998) ISBN 1883011590

- Foreword by John McCain to Popular Mechanics' Debunking 9/11 Myths, May 2006

- Speeches of John McCain, 1988-2000.

References

- ^ a b c Timberg, American Odyssey, 17–34.

- ^ "The Spirit of Endurance", Irish America (August–September 2006). Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Roberts, Gary. "On the Ancestry, Royal Descent, and English and American Notable Kin of Senator John Sidney McCain IV", New England Historic Genealogical Society (2008-04-01). Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ a b Woodward, Calvin. "McCain's WMD Is A Mouth That Won't Quit", Associated Press via USA Today (2007-11-04). Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 19.

- ^ a b Arundel, John. "Episcopal fetes a favorite son", Alexandria Times, (2007-12-06). Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 22.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 28.

- ^ Bailey, Holly. "John McCain: 'I Learned How to Take Hard Blows'", Newsweek (2007-05-14). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ a b c d "John McCain", Iowa Caucuses '08, Des Moines Register. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ^ a b Timberg, Nightingale's Song, 31–35.

- ^ Timberg, Nightingale's Song, 41–42.

- ^ McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 130–131, 141–142.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 32.

- ^ a b "McCain: Experience to Lead", johnmccain.com (2007-11-02). Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 156.

- ^ a b Feinberg, Barbara. John McCain: Serving His Country, 18 (Millbrook Press 2000). ISBN 0761319743.

- ^ a b Timberg, American Odyssey, 66–68.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, 92.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 33.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer. "Bridging 4 Decades, a Large, Close-Knit Brood", New York Times (2007-12-27). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 167–168.

- ^ McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 172–173.

- ^ "VA-46 Photograph Album", The Skyhawk Association. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- ^ a b McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 185–186.

- ^ Karaagac, John. John McCain: An Essay in Military and Political History, 81-82 (Lexington Books 2000). ISBN 0739101714.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard. "Start of Tragedy: Pilot Hears a Blast As He Checks Plane", New York Times (1967-07-31). Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 72–74.

- ^ McCain, Faith of My Fathers, 177–179.

- ^ US Navy. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships - Forrestal. (States either Aircraft No. 405 piloted by LCDR Fred D. White or No. 416 piloted by LCDR John McCain was struck by the Zuni.)

- ^ Timberg, An American Odyssey, 75.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nowicki, Dan & Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: Prisoner of War", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ a b Hubbell, P.O.W., 363.

- ^ "Image 1 of 8, Republican Presidential Candidate Senator John McCain", Chicago Tribune (2000-02-23). Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b Hubbell, P.O.W., 364.

- ^ Apple Jr., R. W. "Adm. McCain's son, Forrestal Survivor, Is Missing in Raid", New York Times (1967-10-28). Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Admiral's Son Captured in Hanoi Raid", Associated Press via Washington Post (1967-10-28). Retrieved 2008-02-09 (fee required for full text).

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 83.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 54.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 89.

- ^ a b Hubbell, P.O.W., 450–451.

- ^ Rochester and Kiley, Honor Bound, 363.

- ^ a b Hubbell, P.O.W., 452–454.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 95, 118.

- ^ a b McCain, John. "How the POW's Fought Back", U.S. News & World Report (1973-05-14), reposted in 2008 under title "John McCain, Prisoner of War: A First-Person Account". Retrieved 2008-01-29. Reprinted in Reporting Vietnam, Part Two: American Journalism 1969–1975, The Library of America, 434-463 (1998). ISBN 1883011590.

- ^ a b Purdum, Todd. "Prisoner of Conscience", Vanity Fair, February 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 60.

- ^ Hubbell, P.O.W., 288–306.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 64.

- ^ Rochester and Kiley, Honor Bound, 489–491.

- ^ Rochester and Kiley, Honor Bound, 510, 537.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 106–107.

- ^ Sterba, James. "P.O.W. Commander Among 108 Freed", New York Times (1973-03-15). Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: Back in the USA", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ a b c d e Kristof, Nicholas. "P.O.W. to Power Broker, A Chapter Most Telling", New York Times (2000-02-27). Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons, Volume 1, Naval Historical Center (via Archive.org). Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: Arizona, the early years", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ a b c d e Frantz, Douglas, "The 2000 Campaign: The Arizona Ties; A Beer Baron and a Powerful Publisher Put McCain on a Political Path", New York Times, A14 (2000-02-21). Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 132–134.

- ^ a b c "McCain Releases His Tax Returns", Associated Press for CBS News (2008-04-18). Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 135.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David. "Senate’s Power and Allure Drew McCain From Military ", New York Times (2008-05-29). Retrieved 2008-05-29.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 93.

- ^ a b Kuhnhenn, Jim. "Navy releases McCain's military record", Associated Press via Boston Globe (2008-05-07). Retrieved 2008-05-25.

- ^ Gilbertson, Dawn. "McCain, his wealth tied to wife's family beer business", Arizona Republic (2007-01-23). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 139.

- ^ Symington would become Governor of Arizona in 1991.

- ^ Thornton, Mary. "Arizona 1st District John McCain", Washington Post, (1982-12-16). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Timberg, American Odyssey, 143–144.

- ^ "McCain, Clinton Head to Memphis for MLK Anniversary", Washington Wire (blog), Wall Street Journal, (2008-04-03). Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ “McCain Remarks on Dr. King and Civil Rights”, Washington Post, (2008-04-04): "We can be slow as well to give greatness its due, a mistake I made myself long ago when I voted against a federal holiday in memory of Dr. King. I was wrong and eventually realized that, in time to give full support for a state holiday in Arizona." Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 98–99, 104.

- ^ "John McCain". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kantor, Jodi. "Vocal on War, McCain Is Silent on Son’s Service", New York Times (2008-04-06). Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Tiron, Roxana. "For McCain, son’s duty in Iraq is not a talking point", The Hill (2008-04-02). Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 147.

- ^ a b Strong, Morgan. "Senator John McCain talks about the challenges of fatherhood", Dadmag.com (2000-06-04). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ a b c d Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: The Senate calls", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Barone, Michael; Ujifusa, Grant; Cohen, Richard. The Almanac of American Politics, 2000 (National Journal 1999), 112. ISBN 0-8129-3194-7.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 112.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, 115–119.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 120.

- ^ a b c Abramson, Jill; Mitchell, Alison. "Senate Inquiry In Keating Case Tested McCain", New York Times (1999-11-21). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b "Excerpts of Statement By Senate Ethics Panel", New York Times (1991-02-28). Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Rasky, Susan. "To Senator McCain, the Savings and Loan Affair Is Now a Personal Demon", New York Times (1989-12-22). Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ a b Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: The Keating Five", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieval date 2007-11-23.

- ^ a b Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: Overcoming scandal, moving on", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 150–151.

- ^ a b Dan Balz, “McCain Weighs Options Amid Setbacks”, Washington Post (1998-07-05) Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 152–154.

- ^ Report of the Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs, U.S. Senate (1993-01-13). Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ a b Walsh, James. "Good Morning, Vietnam", Time Magazine, (1995-07-24). Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 170–171.

- ^ Farrell, John. "At the center of power, seeking the summit", Boston Globe (2003-06-21). Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. "John McCain Report: McCain becomes the 'maverick'", Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ a b c d Maisel, Louis and Buckley, Kara. Parties and Elections in America: The Electoral Process, 163-166 (Rowman & Littlefield 2004). ISBN 0742526704.

- ^ Barone, Michael; Cohen, Richard. The Almanac of American Politics, 2006 (National Journal 2005), 93–98. ISBN 0892341122.

- ^ McCain, Worth the Fighting, 327

- ^ Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1998).

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 176–180.

- ^ “Biography of John McCain”, Institute of Government and Public Affairs, Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, 184–187.

- ^ "U.S. Senators John McCain and Russell Feingold Share 10th John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award", John F. Kennedy Library Foundation (1999-05-24). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: The 'maverick' runs”, Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 194–195.

- ^ “Faith of My Fathers (1999)”, Books and Authors. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ^ Knickerbocker, Brad. "From a Vietnam Prison to the United States Senate", Christian Science Monitor (1999-09-16). Retrieved 2008-05-27.

- ^ “McCain formally kicks off campaign”, CNN (1999-09-27). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Bruni, Frank. “Quayle, Outspent by Bush, Will Quit Race, Aide Says”, New York Times (2000-09-27). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 188–189.

- ^ Harpaz, Beth. The Girls in the Van: Covering Hillary, 86 (St. Martin's Press 2001). ISBN 0312302711.

- ^ a b Corn, David. “The McCain Insurgency”, The Nation (2000-02-10). Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b c d e Steinhauer, Jennifer. “Confronting Ghosts of 2000 in South Carolina”, New York Times (2007-10-19). Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ ”Dirty Politics 2008”, NOW, PBS (2008-01-04). Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Mitchell, Alison. “Bush and McCain Exchange Sharp Words Over Fund-Raising”, New York Times (2000-02-10). Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ^ a b Alexander, Man of the People, 250–251.

- ^ Data for table is from “Favorability: People in the News: John McCain”, The Gallup Organization, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b Knowlton, Brian. “McCain Licks Wounds After South Carolina Rejects His Candidacy”, International Herald Tribune (2000-02-21). Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Mitchell, Alison. “McCain Catches Mud, Then Parades It”, New York Times (2000-02-16). Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ McCaleb, Ian Christopher. “McCain recovers from South Carolina disappointment, wins in Arizona, Michigan”, CNN (2000-02-22). Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ “Excerpt From McCain's Speech on Religious Conservatives”, New York Times (2000-02-29). Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Rothernberg, Stuart. “Stuart Rothernberg: Bush Roars Back; McCain's Hopes Dim”, CNN (2000-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ McCaleb, Ian Christopher. “Gore, Bush post impressive Super Tuesday victories”, CNN (2000-03-08). Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ McCaleb, Ian Christopher. “Bradley, McCain bow out of party races”, CNN (2000-03-09). Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ Marks, Peter. “A Ringing Endorsement for Bush”, New York Times (2000-05-14). Retrieved 2008-03-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: The 'maverick' and President Bush”, Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ a b c Holan, Angie. “McCain switched on tax cuts”, Politifact, St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Edsall, Thomas and Milbank, Dana. “McCain Is Considering Leaving GOP: Arizona Senator Might Launch a Third-Party Challenge to Bush in 2004”, Washington Post (2001-06-02). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b Cusack, Bob. “Democrats say McCain nearly abandoned GOP”, The Hill (2007-03-28). Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ McCain, John. “No Substitute for Victory: War is hell. Let's get on with it”, Wall Street Journal (2001-10-26). Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ “Senate bill would implement 9/11 panel proposals”, CNN (2004-09-08). Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ “Senate Approves Aviation Security, Anti-Terrorism Bills”, Online NewsHour, PBS (2001-10-12). Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ Alexander, Man of the People, 168.

- ^ "Sen. McCain's Interview With Chris Matthews", Hardball, MSNBC (2003-03-12). Via McCain's Senate web site and archive.org. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ^ "Newsmaker: Sen. McCain", PBS, NewsHour (2003-11-06). Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ^ a b c d Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: The 'maverick' goes establishment”, Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ “Summary of the Lieberman-McCain Climate Stewardship Act”, Pew Center on Global Climate Change. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ “Lieberman, McCain Reintroduce Climate Stewardship and Innovation Act”, Lieberman Senate web site, (2007-01-12). Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ^ “McCain: I'd 'entertain' Democratic VP slot”, Associated Press for USA Today (2004-03-10). Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ a b Halbfinger, David. “McCain Is Said To Tell Kerry He Won't Join”, New York Times (2004-06-12). Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ a b Balz, Dan and VandeHei, Jim. “McCain's Resistance Doesn't Stop Talk of Kerry Dream Ticket”, Washington Post (2004-06-12). Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ ”Kerry wants to boost child-care credit”, Associated Press via MSNBC (2004-06-16). Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ a b Loughlin, Sean. “McCain praises Bush as 'tested'”, CNN (2004-08-30). Retrieved 2007-11-14.

- ^ Coile , Zachary. “Vets group attacks Kerry; McCain defends Democrat”, San Francisco Chronicle (2004-08-06). Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ “Election 2004: U.S. Senate - Arizona - Exit Poll”, CNN. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Curry, Tom. “McCain takes grim message to South Carolina”, MSNBC (2007-04-26). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ "Senators compromise on filibusters; Bipartisan group agrees to vote to end debate on 3 nominees", CNN (2005-05-24). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Hulse, Carl. "Distrust of McCain Lingers Over '05 Deal on Judges", New York Times (2008-02-25). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer. "After Bill's Fall, G.O.P. May Pay in Latino Votes", New York Times (2007-07-01). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ "Why the Senate Immigration Bill Failed", Rasmussen Reports (2007-06-08). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ ”Roll Call Votes 109th Congress - 1st Session on the Amendment (McCain Amdt. No. 1977)”, United States Senate (2005-10-05). Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ “Senate ignores veto threat in limiting detainee treatment”, CNN (2005-10-06). Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ “McCain, Bush agree on torture ban”, CNN, (2005-12-15). Retrieved 2006-08-16.

- ^ Ricks, Thomas. Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq 412 (Penguin Press 2006). ISBN 1-59420-103-X.

- ^ Baldor, Lolita. “McCain Defends Bush's Iraq Strategy”, Associated Press via CBS News (2007-01-12). Retrieved 2007-01-13.

- ^ Giroux, Greg. “'Move On' Takes Aim at McCain’s Iraq Stance”, New York Times (2007-01-17). Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ Carney, James. “The Resurrection of John McCain”, Time (2008-01-23). Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Crawford, Jamie. “Iraq won't change McCain”, CNN (2007-07-28). Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ “McCain arrives in Baghdad”, CNN (2008-03-16). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "McCain launches White House bid", BBC News (2007-04-25). Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ^ a b "Remarks as Prepared for Delivery: Senator McCain's Announcement Speech", usatoday.com (2007-04-25). Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ a b Balz, Dan. “For Possible '08 Run, McCain Is Courting Bush Loyalists”, Washington Post (2006-02-12). Retrieved 2006-08-15.

- ^ Schmidt, Susan; Grimaldi, James. "Panel Says Abramoff Laundered Tribal Funds; McCain Cites Possible Fraud by Lobbyist", Washington Post (2005-06-23). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Anderson, John. Follow the Money (Simon and Schuster 2007), 254. ISBN 074328643X.

- ^ Birnbaum, Jeffrey and Solomon, John. “McCain's Unlikely Ties to K Street”, Washington Post (2007-12-31). Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ “McCain lags in fundraising, cuts staff”, CNN (2007-07-02). Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ a b “Lagging in Fundraising, McCain Reorganizes Staff”, NPR (2007-07-02). Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- ^ Sidoti, Liz. “McCain Campaign Suffers Key Shakeups”, Associated Press (2007-07-10). Retrieved 2007-07-15.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan. “McCain's comeback plan”, The Politico (2007-07-19). Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- ^ Witosky, Tom. “McCain sees resurgence in his run for president”, Des Moines Register (2007-12-17). Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ Sinderbrand, Rebecca. “McCain, Clinton win Concord Monitor endorsements”, CNN (2007-12-29). Retrieved 2007-12-29.

- ^ “Coverage of Lieberman endorsement of John McCain”, ABC Nightline (2007-12-18).

- ^ “CNN: McCain wins New Hampshire GOP primary”, CNN (2008-01-08). Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ Jones, Tim. “McCain Wins South Carolina GOP Primary”, Chicago Tribune (2008-01-19). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ “Thompson Quits US Presidential Race”, Reuters (2008-01-22). Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ “McCain wins Florida, Giuliani expected to drop out”, CNN (2008-01-29). Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ Holland, Steve. "Giuliani, Edwards quit White House Race", Reuters (2008-01-30). Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ^ Sidoti, Liz. "Romney Suspends Presidential Campaign", Associated Press via Breitbart.com (2008-02-07). Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ “McCain wins key primaries, CNN projects; McCain clinches nod”, CNN (2008-03-04). Retrieved 2008-03-04.

- ^ Sidoti, Liz. "Senate agrees McCain is eligible for presidency", Associated Press (2008-03-27). Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ^ "Lawyers Conclude McCain Is "Natural Born", Associated Press (2008-03-28). Retrieved 2008-05-23.

- ^ Bash, Dana. "With McCain, 72 is the new... 69?", CNN (2006-09-04). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ "Presidential Inaugural Facts", Miami Herald (1985-01-20). Excerpt via Google News. Retrieved 2008-03-30.

- ^ McCain, John. Interview transcript. Meet the Press via MSNBC (2005-06-19). Retrieved 2006-11-14.

- ^ a b Altman, Lawrence. "On the Campaign Trail, Few Mentions of McCain’s Bout With Melanoma", New York Times (2008-03-09). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ "Medical records show McCain is in good health" International Herald Tribune (2008-05-23). Retrieved on 2008-05-23.

- ^ Page, Susan. "McCain runs strong as Democrats battle on" USA Today (2008-04-28). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ "McCain tells his story to voters" CNN (2008-03-31). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Luo, Michael and Palmer, Griff. "McCain Faces Test in Wooing Elite Donors", New York Times (2008-03-31). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Kuhnhenn, Jim. "Cindy McCain had $6 million income in 2006", Associated Press (2008-05-23). Retrieved 2008-05-24.

- ^ a b Shear, Michael. "A Fifth Top Aide To McCain Resigns", Washington Post (2008-05-19). Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Kammer, Jerry. "Lobbyists on John McCain's Team Facing Some New Rules", The Arizona Republic (2008-05-26). Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Bradley, Tahman. "Obama Open to Town Hall Debates With McCain", ABC News (2008-06-04). Retrieved 2008-06-04.

- ^ Mayer, William. "Kerry's Record Rings a Bell", Washington Post, (2004-03-28). Retrieved 2008-05-12: "The question of how to measure a senator's or representative's ideology is one that political scientists regularly need to answer. For more than 30 years, the standard method for gauging ideology has been to use the annual ratings of lawmakers' votes by various interest groups, notably the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA) and the American Conservative Union (ACU)."

- ^ "2007 U.S. Senate votes", American Conservative Union. Retrieved 2008-05-10. Lifetime rating is given.

- ^ “Voting Records”, Americans for Democratic Action. Retrieved 2008-05-10. Average includes all years beginning with 1983 in House, collected from various parts of ADA website and calculated on spreadsheet.

- ^ Chart is built from current year and archive ratings found within “Ratings of Congress”, American Conservative Union, retrieved 2008-05-10, and “Voting Records”, Americans for Democratic Action, retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Barone, Michael and Cohen, Richard. Almanac of American Politics (2008), 95 (National Journal 2008). ISBN 0-89234-116-0. This biennially-published almanac has been called, "The most important reference text on American politics....the most comprehensive and accurate guide to the labyrinth of U.S. politics ever assembled." Mead, Walter. "The United States", Foreign Affairs (January/February 2006). Retrieved 2008-05-15. In 2005, the economic ratings were 52 percent conservative and 47 percent liberal, the social ratings were 64 percent conservative and 23 percent liberal, and the foreign ratings were 54 percent conservative and 45 percent liberal. In 2006, the economic ratings were 64 percent conservative and 35 percent liberal, the social ratings were 46 percent conservative and 53 percent liberal, and the foreign ratings were 58 percent conservative and 40 percent liberal.

- ^ Robb, Robert. “Is John McCain a Conservative?”, RealClearPolitics (2008-02-01). Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ "Washington Post-ABC News Poll", washingtonpost.com (2008-04-14). Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ "McCain on the Economy at Carnegie Mellon University", New York Times (2008-04-15). This is the full text of his April 15 speech. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ a b c Grier, Peter. "McCain fleshes out his economic plan", Christian Science Monitor (2008-04-28). Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ Walshe, Shushannah. "McCain Sets Goals for His Presidency", Fox News (2008-05-15). Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ "McCain on His Hopes for His First Term", New York Times (2008-05-15). This is the full text of his May 15 speech. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

- ^ Kimball, Richard. "Program History", Project Vote Smart. Retrieved 2008-05-20. Also see Nintzel, Jim. "Test Study: Why are politicians like John McCain suddenly so afraid of Project Vote Smart?", Tucson Weekly (2008-04-17). Retrieved 2008-05-21. Also see Stein, Jonathan. “Senator Straight Talk Won't Go on the Record with Project Vote Smart”, Mother Jones (2008-04-07). Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Senator John Sidney McCain III (AZ)", Project Vote Smart. Retrieved 2008-05-20. Non-partisan information about McCain's issue positions is also provided online by On the Issues. See "John McCain on the Issues", OnTheIssues. Retrieved 2008-05-18.

- ^ "Issues", McCain's official Senate web site. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ "Issues", johnmccain.com. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Brooks, David. “The Character Factor”, New York Times (2007-11-13). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ Mitchell, Josh. "Military Veterans step up for John McCain", Baltimore Sun (2008-02-05). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: McCain becomes the 'maverick'”, Arizona Republic, (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ a b Keller, Julia. "Me? A bad temper? Why, I oughta ...", Chicago Tribune (2008-05-01): "we ... want people in public life to be passionate and engaged. We want them to be fiery and feisty. We like them to care enough to blow their stacks every once in a while. Otherwise, we question the sincerity of their convictions." Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: The Senate calls”, Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ a b c d Steinhauer, Jennifer. “Bridging 4 Decades, a Large, Close-Knit Brood”, New York Times, (2007-12-27). Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ^ Jacobson, Gary. “Partisan Differences in Job Approval Ratings of George W. Bush and U.S. Senators in the States: An Exploration", Paper presented at annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 2006.

- ^ Robb, Robert. “Is John McCain a Conservative?”, RealClearPolitics (2008-02-01). Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ^ Hunt, Albert. “John McCain and Russell Feingold” in Profiles in Courage for Our Time, 256 (Kennedy, Caroline ed., Hyperion 2003): "The hero is indispensable to the McCain persona." ISBN 0786886781.

- ^ Purdum, Todd. “Prisoner of Conscience”, Vanity Fair, February 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Simon, Roger. “McCain's Health and Age Present Campaign Challenge”, The Politico (2007-01-27). Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ McCain, Worth the Fighting, xvii.

- ^ Milbank, Dana. “A Candidate's Lucky Charms”, Washington Post (2000-02-19). Retrieved 2006-04-08.

- ^ Campanille, Carl. "'Like to Hike' McC Loves Uphill Climb, Stays Fit in Ariz. Outdoors", New York Post (2008-03-10). Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ^ Corn, David. "A joke too bad to print?", Salon.com (1998-06-25). Retrieved 2006-08-16.

- ^ Nowicki, Dan and Muller, Bill. “John McCain Report: The Senate calls”, Arizona Republic (2007-03-01). Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen. “The Joke's On Him”, New York Times (1998-06-21). Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- ^ Drew, Citizen McCain, 23.

- ^ “Best and Worst of Congress”, Washingtonian, September 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- ^ Drew, Citizen McCain, 21–22.

- ^ Zengerle, Jason. “Papa John”, New Republic (2008-04-23). Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ^ "A Conversation About What's Worth the Fight", Newsweek (2008-03-29): "I have—although certainly not in recent years—lost my temper and said intemperate things... I feel passionately about issues, and the day that passion goes away is the day I will go down to the old soldiers' home and find my rocking chair." Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ "On The HUSTINGS - April 21, 2008", New York Sun (2008-04-21): “I am very happy to be a passionate man... many times I deal passionately when I find things that are not in the best interests of the American people. And so, look, 20, 25 years ago, 15 years ago, that's fine, and those stories here are either totally untrue or grossly exaggerated." Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ a b c d e f Kranish, Michael. “Famed McCain temper is tamed”, Boston Globe (2008-01-27). Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ Renshon, Stanley. "The Comparative Psychoanalytic Study of Political Leaders: John McCain and the Limits of Trait Psychology" in Profiling Political Leaders: Cross-cultural Studies of Personality and Behavior, 245 (Feldman and Valenty eds., Greenwood Publishing 2001): "McCain was not the only candidate or leader to have a temper." ISBN 0275970361.

- ^ Coleman, Michael. "Domenici Knows McCain Temper", Albuquerque Journal, Online Edition (2008-04-27). Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Kane, Paul. "GOP Senators Reassess Views About McCain", Washington Post (2008-02-04): "the past few years have seen fewer McCain outbursts, prompting some senators and aides to suggest privately that he is working to control his temper." Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Novak, Robert. “A Pork Baron Strikes Back”, Washington Post (2008-02-07). Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ Michael Leahy. “McCain: A Question of Temperament”, Washington Post (2008-04-20). ("Cornyn is now a McCain supporter, as is Republican Sen. Thad Cochran of Mississippi, himself a past target of McCain's sharp tongue, especially over what McCain regarded as Cochran's hunger for pork-barrel projects in his state. Cochran landed in newspapers early during the campaign after declaring that the thought of McCain in the Oval Office 'sends a cold chill down my spine.'") Retrieved 2008-04-28. McCain aide Mark Salter challenged the accuracy of some other elements of Leahy's article; see “McCain's Temper, Ctd.”, National Review Online (2008-04-20). Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ Raju, Manu. “McCain reaches out to GOP senators with weekly meetings”, The Hill (2008-04-30). Retrieved 2008-05-04

- ^ Timberg, An American Odyssey, 144–145.

- ^ Bumiller, Elisabeth. “Two McCain Moments, Rarely Mentioned”, New York Times (2008-03-24). Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ Welch, Matt. “Do we need another T.R.?”, Los Angeles Times (2006-11-26). Retrieved 2007-12-19.

- ^ Tilghman, Andrew. “McCain win might stop sons from deploying”, Navy Times (2008-03-10). Retrieved 2008-03-28.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Paul. Man of the People: The Life of John McCain (John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey 2002). ISBN 0-471-22829-X. Available online in limited preview at Google Books.

- Brock, David and Waldman, Paul. Free Ride: John McCain and the Media (Anchor Books 2008). ISBN 0307279405.

- Drew, Elizabeth. “Citizen McCain” (Simon & Schuster 2002). ISBN 978-0743230025.

- Feinberg, Barbara. John McCain: Serving His Country (Millbrook Press 2000). ISBN 0761319743.

- Hubbell, John G. P.O.W.: A Definitive History of the American Prisoner-Of-War Experience in Vietnam, 1964–1973 (Reader's Digest Press, New York 1976). ISBN 0883490919.

- Karaagac, John. John McCain: An Essay in Military and Political History (Lexington Books 2000). ISBN 0739101714.

- McCain, John and Salter, Mark, Faith of My Fathers (Random House, New York 1999). ISBN 0-375-50191-6.

- McCain, John and Salter, Mark. Worth the Fighting For (Random House, New York 2002). ISBN 0-375-50542-3.

- Rochester, Stuart I. and Kiley, Frederick. Honor Bound: American Prisoners of War in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973 (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland 1999). ISBN 1557506949.

- Schecter, Cliff. The Real McCain: Why Conservatives Don't Trust Him and Why Independents Shouldn't (PoliPoint Press 2008). ISBN 0-979-48229-1.

- Timberg, Robert. John McCain: An American Odyssey (Touchstone Books, New York 1999). ISBN 0-684-86794-X. Online access to Chapter 1 is available.

- Timberg, Robert. The Nightingale's Song (Simon & Schuster, New York 1996). ISBN 0-684-80301-1. Online access to a portion of Chapter 1 is available.

- Welch, Matt. “McCain: The Myth of a Maverick” (Palgrave Macmillan 2007). ISBN 978-0230603967.

External links

- Senate

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Presidential campaign

- Presidential Campaign Website

- John McCain Forum Supporters Forum

- McCainpedia - a wiki containing Democratic opposition research

- Documentaries, topic pages and databases

- New York Times – John McCain news stories and commentary

- Template:Dmoz

- John McCain's Navy Records some of his records released by the United States Navy

- Interview About POW Experience at Library of Congress

{{subst:#if:McCain, John|}} [[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1936}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:LIVING}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1936 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:LIVING}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- LIVING deaths

- John McCain

- Arizona Republicans

- Current members of the United States Senate

- United States Senators from Arizona

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Arizona

- Shot-down aviators

- Vietnam War prisoners of war

- United States Navy officers

- United States naval aviators

- American military personnel of the Vietnam War

- United States Naval Academy graduates

- Recipients of the Silver Star medal

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of US Distinguished Flying Cross

- Recipients of the Bronze Star medal

- Recipients of the Purple Heart medal

- Recipients of the Prisoner of War Medal

- United States presidential candidates, 2000

- United States presidential candidates, 2008

- Politicians with physical disabilities

- American adoptive parents

- American autobiographers

- American biographers

- American memoirists

- American military writers

- American motivational writers

- American political writers

- Arizona writers